Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Eco-Friendly Particleboards Produced with Banana Tree (Musa paradisiaca) Pseudostem Fibers Bonded with Cassava Starch and Urea-Formaldehyde Adhesives

1 Wood Industry and Utilisation Division, Council for Scientific and Industrial Research-CSIR, Forestry Research Institute of Ghana-FORIG, Kumasi, P.O. Box UP63, Ghana

2 Department of Agronomic and Forestry Sciences-DCAF, Federal University of Semiarid Region-UFERSA, Av. Francisco Mota, 572, Costa e Silva, Mossoró, 59625-900, Brazil

3 Jundiaí Agricultural School-EAJ, Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte-UFRN, RN 160, km 03, s/n, Distrito de Jundiaí, Macaíba, 59280-000, Brazil

* Corresponding Author: Fernando Rusch. Email:

Journal of Renewable Materials 2025, 13(7), 1475-1489. https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2025.02025-0047

Received 06 March 2025; Accepted 12 May 2025; Issue published 22 July 2025

Abstract

The increase in wood and wood-based products in the construction and furniture sectors has grown exponentially, generating severe environmental and socioeconomic impacts. Particleboard panels have been the main cost-benefit option on the market due to their lightness and lower cost compared to solid wood. However, the synthetic adhesives used in producing traditional particleboard panels cause serious harm to human health. Developing particleboard panels with fibrous waste and natural adhesives could be a sustainable alternative for these sectors. The work aimed to create particleboards with fibrous wastes from the pseudostem of the banana tree (Musa paradisiaca) and different proportions of the natural adhesive cassava starch-CS in replacement of synthetic adhesive urea-formaldehyde-UF. Five experimental groups were manufactured with banana trees and different percentages of UF and CS adhesives, namely (100 UF–0% CS), (50% UF–50% CS), (30% UF–70% CS), (10% UF–90% CS) and (0% UF–100% CS). The particleboards had their physical-mechanical properties determined. The apparent density values did not show significant variation between the assessed treatments. Regarding the water absorption and thickness swelling, the best performances were observed for the panels made without the addition of CS (100% UF). For the mechanical properties of static bending strength and Janka hardness, it was identified that adding up to 50% CS did not interfere with the quality of the panels. These analyses show that the particleboard panels produced with wastes of the banana tree bonded with natural CS adhesive may be an economically viable and environmentally correct alternative, positively strengthening the development of sustainable strategies.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

The consumption of natural raw materials in civil construction has been growing exponentially, thus strongly impacting the environmental and socioeconomic spheres of sustainable development goals [1]. In this context, wood and other fibers are considered the most essential natural resources for sustainable development, mainly because they are renewable materials and great stores of CO2. These characteristics make this material necessary for applications in the construction sector [2]. The increase in products made from wood has been growing continuously worldwide, generating a shortage of wood resources. Materials such as particleboard, plywood, and fiber derivatives are among the highest global demands [3]. Donini et al. [4] explain that the furniture and construction sectors widely use particleboard made from wood. According to Tawasil et al. [5], these materials have properties such as stability for designing on simple production lines, quality in the parts, reliability, good dimensioning, and ease of use. Particleboards are available for manufacturing office and residential furniture, acoustic insulation materials, decks, ceilings, partition panels, internal panels, kitchen shelves, and so on.

Particleboards are materials composed mainly of synthetic adhesives and particles derived from wood and other types of fibers [3]. The growing demand for lightweight materials for furniture manufacture has made the particleboard market essential since constructing these materials using agglomerates has a lower cost than wood panels [6]. However, companies and producers of wood/derivatives have faced significant problems generated by the insufficient quantities of these raw materials in the market. This factor has promoted fierce competition among the timber industries [7]. According to Donini et al. [4], trees have a variable growth rate between species and can take 3 to 40 years to grow and reach the point of being cut and used for engineering applications. Another factor that deserves to be highlighted is the problems caused by synthetic adhesives, mainly urea-formaldehyde ones. Mohd Azman et al. [6] state standard particleboards contain around 10% of synthetic urea-formaldehyde adhesives. Formaldehyde-based compounds were classified as carcinogenic, causing the production and disposal of particleboards to be a severe factor that impacts human health and the environment.

The use of alternative materials in the production of particleboard panels can be an alternative to save wood and to manage large amounts of waste produced [8]. The high production of agricultural waste has become a serious environmental problem. The main factors directly linked to high productivity are lack of management, labor force scarcity, transportation costs, large amounts of mechanized systems, and ineffective disposal of waste to produce forage [9]. Pang et al. [3] claim that improper waste management results in high carbon emissions, which can contribute to climate change. According to Cangussu et al. [10], producing a new environmentally friendly and low-cost product from reusing natural fibers can benefit society considerably. Renewable raw materials from agricultural activities positively valorize all plant parts, such as using seeds for food and long fibers to produce technical composite materials or applications in the textile industry [1]. Technological advances in industries have sought innovations in developing adhesives for producing particleboard panels, thus aiming to reduce formaldehyde emissions [11].

Between 2020 and 2023, the African continent was responsible for 22.4% of the world’s banana production, emphasizing the countries of Nigeria, Angola, Tanzania, Kenya and Ethiopia [12]. It is estimated that banana cultivation generates approximately 220 t of waste per hectare [13]. Composite industries’ use of plant-based fibers can play a critical role in producing materials, directly contributing to the development of natural fiber markets [14]. Rajendran and Nagarajan [15] also report that fibers extracted from the inside of banana and jute stems are low-cost and have properties such as lightness, tensile strength, and high specific modulus. According to Narciso et al. [16], replacing pine wood in multilayer panels with coconut fibers improves the material’s capacity to absorb water and swell. The increase in the amount of coconut fibers also promotes a decrease in the thermal conductivity properties of the panels. In another study carried out by Rajendran and Nagarajan [15], composite materials reinforced with banana fibers, jute, and peanut shells promote improvements in chemical, physical, mechanical, and fire resistance properties.

Using banana fiber waste and natural adhesive from cassava starch to manufacture ecological particleboard panels can be an appealing alternative to replacing traditional wood panels bonded with urea-formaldehyde adhesives. According to Echeverría-Maggi et al. [17], promoting an appropriate destination for agricultural waste from banana fibers is an environmentally friendly alternative. Sivaranjana and Arumugaprabu [18], adding banana fibers to composite materials as reinforcement enhances their tensile, impact, and static bending strengths. It provides higher thermal stability to the developed material. Regarding natural adhesives, Mahieu et al. [1] report that biodegradable adhesives can be derived from various products, such as proteins, polysaccharides, tannins, or vegetable resins. Agarwal et al. [19] show that polymers derived from natural sources are materials with excellent natural availability and are low-cost and biodegradable. African agricultural industries produce around 146 million tonnes of cassava annually, generating around 40 million tonnes of waste annually [20]. According to Wongphan et al. [21], the cassava starch crop is widely cultivated in the tropical regions of Brazil, China, and Thailand. Growing this species is crucial for the economy, and the starch from this plant has great potential for producing biodegradable packaging and bioplastics. Khurshida et al. [22] report that starch is an abundantly available, low-cost, and renewable material. Therefore, it has been widely used in the industry to produce paper, pharmaceutical products, and textiles. Given the environmental and economic benefits of using agro-industrial waste to produce ecological particleboard panels. The present work aims to evaluate the physical-mechanical properties of particulate panels developed by reinforcement with vegetable fibers from the pseudostem of the banana tree (Musa sp.), bound by different percentages of the natural matrix of cassava starch and the synthetic matrix of urea/formaldehyde.

2.1 Obtaining Raw Materials and Panels Manufacture

In the manufacturing process of the ecological particleboard panels, a fibrous reinforcement extracted from the pseudostem of Musa paradisiaca was used. The fibers were taken from unproductive banana trees existing in small plantations. Using a forage crusher consisting of steel hammers rotating at high speed, the banana fibers were transformed into particles with particle sizes ranging from 0.5 to 1.5 mm (Fig. 1). The banana fibers used in the manufacture of the panels had a moisture content of 12%.

Figure 1: Processing of the fibers extracted from the banana trees pseudostem: (A) pseudostem collection; (B) extracted pseudostem; (C) grinding of the pseudostem into particles; (D) ground particles; (E) particles sieving; (F) ready-to-use particles

Two types of adhesives were used to bond the constituents. The natural adhesive was made from CS harvested in small farmers’ plantations. The synthetic UF adhesive was purchased from local stores. All constituents used in the research were obtained in the Humjibre region, Ghana. The experiment was set in an entirely randomized design with five treatments and four replicates. The experimental treatments had different percentages of UF and CS adhesives to bond the particleboards: (100% UF–0% CS), (50% UF–50% CS), (30% UF–70% CS), (10% UF–90% CS) and (0% UF–100% CS).

Before the manufacturing stage of the particleboard panels, the natural adhesive obtained from CS was produced. The manufacturing followed the procedures established by Ramash et al. (2014). The CS was harvested and sent to the cleaning stage, where it was washed in running water and the husks removed. Using a forage grinder, the material was processed until a paste was formed. Then, it was diluted in distilled water at 26°C ± 2°C. The solution was filtered through a sieve with a 1 mm mesh and left to rest for 24 h at a room temperature of 30°C ± 2°C. Subsequently, the solution was decanted to yield the cassava starch. The obtained starch was used to manufacture the natural CS adhesive. The synthetic UF adhesive employed in the experiment had the following properties: 65% solids content, 1.3 g cm−3 specific density, 230 mPa · s viscosity, pH 7.5, and gel time of 65 s.

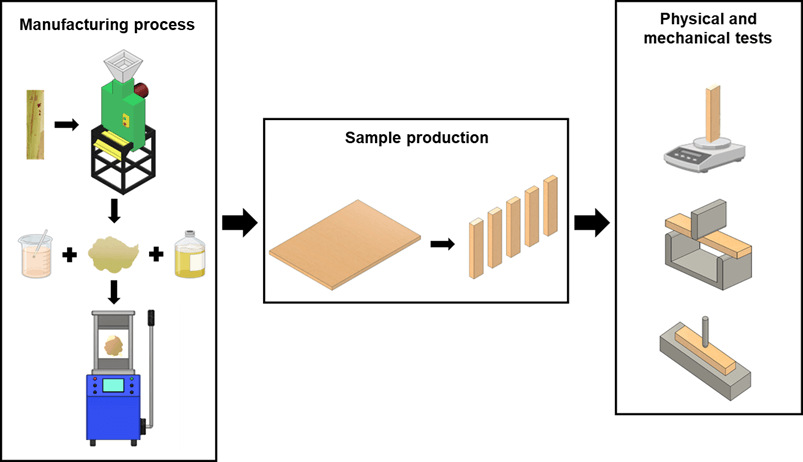

The proportions of the reinforcement of banana tree fibers and the CS and UF were previously set to carry out the manufacturing process of particleboard panels. Subsequently, the constituents were weighed one by one and mixed. The adhesives were placed in a polypropylene container and mixed according to the proportions established for each experimental treatment. A 2% (weight-weight) ammonium chloride-based catalyst was added to the mixture as the curing agent for the UF adhesive. Then, the banana tree pseudostem particles were brought together in the adhesive mixture. The mixture was homogenized, and the final material was introduced into an aluminum mold measuring 300 × 300 × 30 mm (Width × Length × Thickness). The mold was closed and positioned in a thermal hydraulic press. A pressure of 3.5 MPa was applied at 170°C ± 2°C for 8 min. After manufacturing, the panels were de-molded and, after that, conditioned for 6 days at 20°C ± 2°C and relative humidity of 62% ± 2%. After the conditioning stage, the panels were marked and cut to obtain samples for physical and mechanical tests. Four particleboard panels were produced for each experimental treatment. A quantity of 5 samples was taken from each panel to perform physical and mechanical tests. The research included a total of 20 repetitions per treatment. The flowchart in Fig. 2 shows all the manufacturing steps of sustainable particleboards and the proportions used in each treatment.

Figure 2: Schematic representation of the manufacturing process of particleboards of banana tree fibers bonded with different proportions of urea-formaldehyde-UF and cassava starch-CS adhesives

2.2 Determination of the Physical-Mechanical Properties

The apparent density of the particleboards was determined according to the methodology used by Widyorini et al. [23]. Initially, distilled water was added to the rim of a cylindrical container with a volume of 50 L. The panels were inserted individually into the container and then weighed. The density was determined from the mass ratio to the volume of each manufactured panel. The process was carried out in five replicates for each treatment evaluated in the research. Water absorption and thickness swelling tests were carried out to determine the influence of water on the properties of the particleboards and to establish the best environments for their application. The experimental procedures followed the ASTM D1037 [24] standard. Initially, the samples were weighed on an analytical balance. Width, length, and thickness were measured using a digital caliper. The samples were submerged in a polypropylene tray containing distilled water at 25°C ± 2°C. The samples were removed from the water after 2 and 24 h, and weighing and dimensional measurements were performed. The water absorption after 2 and 24 h was obtained from the mass variation of the samples before and after immersion. The thickness swelling was determined from the dimensional variations before and after 2 and 24 h immersions.

A static bending test was performed to find the particleboard’s flexural strengths. All procedures followed the procedures from the ASTM D 1037 [24] standard. The samples with dimensions of 250 mm × 50 mm × 20 mm (length × width × thickness) were individually placed in a universal testing machine (Inspekt 50-1, Hegewald & Peschke, Nossen, Germany) (Fig. 3A). A 50 kN load cell and a speed of 4 mm · min−1 were used to perform the test. The tests were conducted and considered to have ended after the total rupture of the specimens (Fig. 3B). From the force and deformation data provided by the equipment, the results of the modulus of rupture and modulus of elasticity of the particleboards were determined.

Figure 3: Sequence to determine the bending strength and the Janka hardness for the particleboards: (A) measurement of the dimensions (in mm) of the test specimens; (B) three-point bending strength assay; (C) Janka hardness assay

The Janka hardness was determined to evaluate the resistance of the panels to scratches and penetrations. The tests were carried out according to the parameters established by the ASTM D1037 [24] standard. To perform the test, the samples were individually positioned in a universal mechanical testing machine (Instron 4482, Instron, Norwood, MA, USA). Then, a spherical steel indenter with a diameter of 11.28 mm was placed on the surface of the specimen. The test ended when the sphere reached 5.6 mm on the test specimen surface (Fig. 3C). The data generated by the universal machine were used to determine the Janka hardness resistance property of the particleboard panels.

All experimental data obtained were subjected to the Shapiro-Wilk normality test and Levene homogeneity test to verify the existence of statistically significant differences between the properties analyzed and promote higher reliability of the results obtained. The analysis of variance (ANOVA) test was applied and followed by the Tukey test, which is intended to compare the experimental means at a 95% probability.

The apparent density had the highest value (543.0 kg cm−3) for the particleboards from the (0% UF–100% CS) experimental treatment. The experimental treatment (100% UF–0% CS) showed the lowest value (493.0 kg cm−3) for the same property. From the analysis, it is possible to verify that the increase in the percentage of CS adhesive increased the density of the particleboard panels (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: Apparent densities found for the particleboard as a function of the variation of the percentage of urea-formaldehyde-UF and cassava starch-CS adhesives. Means followed by the same letter did not differ statistically by the Tukey test at a 95% probability

A panel’s density depends on factors such as particle configuration, particle distribution in the mold, pressing temperature, adhesive reactivity, and particle compressive strength [25]. Density is a fundamental property for determining the compaction rate of particleboards. It also shows the potential of the raw material for the pressing and compaction process [26]. The high value of the density property can favor the increase of the mechanical properties of the panels [27]. Other positive factors are that the use of CS in the production of materials provides a reduction in the environmental impacts generated by synthetic adhesives, a reduction in petroleum-derived materials, an incentive for the sustainable cultivation of CS, job creation, and an increase in income for rural populations [28].

3.2 Water Absorption and Thickness Swelling

The test to determine water absorption after 2 and 24 h of immersion showed that (0% UF–100% CS) treatment had the highest values, 9.9% and 23.7%. The lowest values were 7.7% and 18.2%, presented by the (100% UF–0% CS). The treatment (50% UF–50% CS) was the one that showed the lowest values among the panels composed of the two types of adhesives, 8.7% and 20.7% (Fig. 5A).

Figure 5: Water absorption (A) and thickness swelling (B) determined for banana tree pseudostem particleboards bonded with urea-formaldehyde-UF and cassava starch-CS adhesives. Means followed by different letters are statistically dissimilar by the Tukey test at a 95% probability

The results show that the higher the CS percentage, the higher the water absorption of the panels. For Wronka and Kowaluk [29], materials with greater porosity and empty spaces inside absorb water more easily. The large amount of hydroxyl and amino groups in the constituents can generate higher water absorption by the panels [30]. The time the panels are exposed to environmental conditions in the presence of water favors an increase in the absorption percentage [31]. The values were lower than 47.2% and 98.0% for cellulose microfiber panels bonded with cornstarch and Mimosa-tannin adhesive after 2 and 24 h [32]. Given the scarcity of raw materials from wood, Lee et al. [33] explain that using agricultural biomass materials can be an interesting alternative to produce low-cost ecological panels.

The thickness swelling test found that the 100% CS treatment presented the highest swelling percentage after 2 and 24 h of immersion in water, 3.5% and 11.5%, respectively. After 2 h of immersion in water, the lowest value was 3.1% for the (50% UF–50% CS) treatment. The lowest value after 24 h was 9.4%, presented by the (100% UF–0% CS) treatment (Fig. 5B). The analysis showed that the increasing percentages of CS adhesive caused an increase in the thickness swelling of the particleboard panels due to the higher hydrophilic character of that material. The type of adhesive and the size of the particles used to manufacture the panels determine the ability to attract water [34]. Hydrophilicity and hygroscopicity negatively affect the mechanical properties of materials reinforced with natural fibers. These composite materials tend to swell when exposed to environments with high humidity, generating stresses in the matrix and the appearance of cracks in the material [35]. Although ecological panels produced with banana tree wastes and CS adhesive have limitations for applications in environments with high humidity, they can be an interesting indoor alternative. After 2 and 24 h of water immersion, the results obtained in the research were lower than 5.2% and 14.7% of the particleboard panels of Eucalyptus badjensis and phenol-formaldehyde resin [36]. Uemura Silva et al. [37] explains that when choosing a polymer, one must consider the curing time, mechanical performance, and sustainability issues. These characteristics favor the use of ecological panels produced with CS adhesive, as demonstrated by the data found in the present work.

Performing a general analysis of the physical properties, the treatment (50% UF–50% CS) showed the best performance among the panels manufactured with the two types of adhesives. The results of water absorption and thickness swelling were better than those presented by commercial Eucalyptus sp. and UF particleboards [38] and commercial High-density fiberboard of Eucalyptus spp. and UF [39]. Fig. 6 presents a comparative analysis of the results.

Figure 6: Comparative analysis of the physical properties of water absorption and thickness swelling between the particleboards (50% urea-formaldehyde-UF and 50% cassava starch-CS adhesives) and traditional commercial panels [38,39]

Regarding bending strength tests, the treatment (100% UF–0% CS) presented the highest value for the modulus of rupture (MOR), 16.5 MPa. The lowest values for the MOR were 12.9 MPa of the (10% UF–90% CS) and (0% UF–100% CS) experimental treatments (Fig. 7A). Among the particleboards composed of the 50% UF and 50% CS was the one that presented the highest values for the rupture and elasticity modules, being 15.0 and 2302.0 MPa (Fig. 7).

Figure 7: Modulus of rupture (A) and elasticity (B) determined for banana tree pseudostem particleboards bonded with urea-formaldehyde-UF and cassava starch-CS adhesives. Means followed by different letters are statistically dissimilar by the Tukey test at a 95% probability

Therefore, when exposed to static bending tests, it was discovered that the panels’ resistance decreased and the proportion of CS adhesive increased. The bending properties depends directly on the microstructure of the constituents and the bond at the interface between the reinforcement and the matrix. The low resistance can also be linked to a decrease in the total surface area for the reinforcement-matrix interaction, causing the transfer of negative mechanical loads to the interface region of the material [40]. The presence of voids causes a decrease in the strength of particleboards [41]. Although the CS adhesive caused a reduction in the bending strength, the values were higher than 11.1 MPa for cocoa wood waste particleboards (Theobroma cacao) bonded with a CS adhesive [42]. On the other hand, the values reached 6.2–9.8 MPa for ground Pinus sylvestris particleboards glued with a UF adhesive [29]. All bending strength values in the present experiment met the 8 MPa minimum limit established for type-8 panels described in the JIS A 5908 standard [43]. Therefore, ecological panels produced with particles from banana tree pseudostems can be an acceptable alternative for mechanical bending applications that do not exceed resistance limits.

Concerning the modulus of elasticity, the highest observed value was 2413.0 MPa, indicated by the treatment (100% UF–0% CS), and the lowest was 2173.0 MPa, presented by the treatment (0% UF–100% CS). The (50% UF–50% CS) and (30% UF–70% CS) had intermediate values, not differing statistically from each other (Fig. 7B). The analyses showed a pattern similar to the results obtained for the modulus of rupture. The increase in the percentage of the CS adhesive also caused a reduction in the modulus of elasticity of the panels. The fibers’ orientation and the adhesive type must be considered in manufacturing the panels, as they can influence the properties. Mensah et al. [42] also found a decrease in the modulus of elasticity after adding 50% CS adhesive to panels particleboard with Theobroma cacao wood waste. Zakaria et al. [44] verified a reduction in the modulus of elasticity after adding 25% CS adhesive to agglomerated panels reinforced with palm oil. However, the results presented in the research were superior to cassava starch panels with percentages of 10%, 60%, 70%, and 80% of banana leaf fibers in studies made by Sivakumar et al. [45]. Another positive point is that all the panels manufactured in the research meet the minimum limits of 10.0 and 1550.0 MPa for the modulus of rupture and elasticity established by ANSI A208.1 [46] and 11.5 and 1600.0 MPa for general-purpose particleboards panels established by EN 312-2 [47].

Performing a general analysis of the mechanical property of flexural strength, it was found that among the panels manufactured with the two types of adhesives, the treatment (50% UF–50% CS) was the one that showed the best results for the modulus of rupture and elasticity. The values were higher than those presented by commercial Eucalyptus sp. particleboards with UF [38] and commercial high-density fiberboard [38]. Fig. 8 presents a comparative analysis of the results.

Figure 8: Comparative analysis of the mechanical property of flexural strength between the panel (50% UF–50% CS) and traditional commercial particleboards [38,39]

The highest resistance value for the Janka hardness test was 8.8 MPa. However, the value did not differ statistically from the 8.7 MPa indicated by the treatment (50% UF–50% CS). The treatment’s lowest value was 4.4 MPa (30% UF–70% CS) (Fig. 9).

Figure 9: Janka hardness determined for banana tree pseudostem particleboards bonded with urea-formaldehyde-UF and cassava starch-CS adhesives. Means followed by different letters are statistically dissimilar by the Tukey test at a 95% probability

From the results obtained, a significant decrease in the Janka hardness was verified after adding 70% CS adhesive. The reduction in the hardness of the panels may have occurred due to a higher amount of waste, reducing the resistance of the material’s surface [48]. For de Oliveira Paula et al. [49], fibrous layers on the surface provide a soft, light surface area with less resistance to piercing loads. Although the panels produced here showed a decrease in the Janka hardness compared to the 100% UF treatment, the material still presented a hardness higher than 7.1 MPa found for particleboard panels produced by Mensah et al. [42] with Theobroma cacao wood waste and UF adhesive and 5.7 MPa of particleboards with the same waste and CS adhesive. The experimental results demonstrated that the panels manufactured with banana tree waste CS adhesive have a noteworthy potential to produce ecological particleboard panels. Uemura Silva et al. [37] highlights that the use of waste in particleboard manufacturing can be an acceptable alternative to improve the life cycle of these materials, reduce the steps related to processing, and contribute to not increasing the environmental burden generated by the waste processing steps.

This study evaluated the physical and mechanical properties of particleboard panels produced with particles from banana trees pseudostem bonded with urea-formaldehyde and cassava starch in different percentages of the mixture. In the evaluation of physical properties, the addition of 100% CS adhesive brought about a significant increase in the apparent density of the panels. It also increased water absorption and thickness swelling of the materials after the 2 and 24 h of immersion. In the mechanical properties assessment, employing 100% CS adhesive caused a decrease in the moduli of rupture and elasticity determined from the bending test. It also promoted a reduction in the Janka hardness property. However, the panels with (50% UF–50% CS) did not show a statistically significant decrease in the Janka hardness. All panels manufactured with the addition of CS adhesive met the minimum strength limits established by ANSI A208.1 [46] and EN 312-2 [47] standards for general-purpose panels. However, the panel (50% UF–50% CS) was the one that presented the best performance among the treatments with CS adhesive in the composition. These characteristics qualify the panels produced in this work for different applications in indoor environments with low humidity. They consist of ecological panels and have the potential for the manufacture of shelves, furniture, and elements for partitions. Other positive points are value-addition to the banana trees pseudostem, a waste generated during the suppression of old plants when the new plantations are deployed. Another advantage of banana tree waste is the reduction in the use of synthetic UF adhesive for particleboard production. These factors contribute to developing ecological, sustainable, and environmentally friendly materials. Research on natural adhesives from CS adhesives still lacks studies to reduce hygroscopic properties and improve mechanical properties.

Acknowledgement: The authors thank the “Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior” (CAPES) for granting graduate scholarships, and the “Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico” (CNPq) for the granting of a postdoctoral scholarship. To the Forestry Research Institute of Ghana, the “Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte” (UFRN) and the “Universidade Federal Rural do Semi-Árido” (UFERSA) for providing human resources, materials, and infrastructure for the study.

Funding Statement: This study was financed by “Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico” (CNPq) and “Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior” (CAPES)-Finance Code 001.

Author Contributions: All authors contributed to the study’s conception and design. Prosper Mensah, Rafael Rodolfo de Melo, Edgley Alves de Oliveira Paula and Fernando Rusch conducted the main experiments and elaborated the manuscript draft; Fernando Rusch and Rafael Rodolfo de Melo raised funds, supervised all the research steps, and interpreted the statistical analyses; Alexandre Santos Pimenta and Juliana de Moura assisted to reviewed the manuscript draft; Alexandre Santos Pimenta and Juliana de Moura revised the original draft. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Raw data were generated at the Forestry Research Institute of Ghana. Derived data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Mahieu A, Vivet A, Poilane C, Leblanc N. Performance of particleboards based on annual plant byproducts bound with bio-adhesives. Int J Adhes Adhes. 2021;107:102847. doi:10.1016/j.ijadhadh.2021.102847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Goldhahn C, Cabane E, Chanana M. Sustainability in wood materials science: an opinion about current material development techniques and the end of lifetime perspectives. Philos Trans A Math Phys Eng Sci. 2021;379(2206):20200339. doi:10.1098/rsta.2020.0339. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Pang B, Zhou T, Cao XF, Zhao BC, Sun Z, Liu X, et al. Performance and environmental implication assessments of green bio-composite from rice straw and bamboo. J Clean Prod. 2022;375(6):134037. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.134037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Donini G, Crociati L, Molari L, Ferrante M, Conidi G, Zambelli P. Mechanical characterization of mixed particleboard panels made of recycled wood and Arundo donax. Ind Crops Prod. 2025;224(4):120244. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2024.120244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Tawasil DNB, Aminudin E, Abdul Shukor Lim NH, Nik Soh NMZ, Leng PC, Ling GHT, et al. Coconut fibre and sawdust as green building materials: a laboratory assessment on physical and mechanical properties of particleboards. Buildings. 2021;11(6):256. doi:10.3390/buildings11060256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Mohd Azman MAH, Ahmad Sobri S, Norizan MN, Ahmad MN, Wan Ismail WOAS, Hambali KA, et al. Life cycle assessment (LCA) of particleboard: investigation of the environmental parameters. Polymers. 2021;13(13):2043. doi:10.3390/polym13132043. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Pędzik M, Auriga R, Kristak L, Antov P, Rogoziński T. Physical and mechanical properties of particleboard produced with addition of walnut (Juglans regia L.) wood residues. Materials. 2022;15(4):1280. doi:10.3390/ma15041280. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Pędzik M, Janiszewska D, Rogoziński T. Alternative lignocellulosic raw materials in particleboard production: a review. Ind Crops Prod. 2021;174(3):114162. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2021.114162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Sangmesh B, Patil N, Jaiswal KK, Gowrishankar TP, Selvakumar KK, Jyothi MS, et al. Development of sustainable alternative materials for the construction of green buildings using agricultural residues: a review. Constr Build Mater. 2023;368(1):130457. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.130457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Cangussu N, Chaves P, da Rocha W, Maia L. Particleboard panels made with sugarcane bagasse waste—an exploratory study. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2023;30(10):25265–73. doi:10.1007/s11356-021-16907-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Baharuddin MNM, Zain NM, Harun WSW, Roslin EN, Ghazali FA, Md Som SN. Development and performance of particleboard from various types of organic waste and adhesives: a review. Int J Adhes Adhes. 2023;124:103378. doi:10.1016/j.ijadhadh.2023.103378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Crops and livestock products [Internet]. [cited 2025 Mar 01]. Available from: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL/visualize. [Google Scholar]

13. Ahmad T, Danish M. Prospects of banana waste utilization in wastewater treatment: a review. J Environ Manag. 2018;206(3):330–48. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2017.10.061. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Hernandez-Estrada A, Müssig J, Hughes M. The impact of fibre processing on the mechanical properties of epoxy matrix composites and wood-based particleboard reinforced with hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) fibre. J Mater Sci. 2022;57(3):1738–54. doi:10.1007/s10853-021-06629-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Rajendran M, Nagarajan CK. Experimental investigation on bio-composite using jute and banana fiber as a potential substitute of solid wood based materials. J Nat Fibres. 2022;19(12):4557–66. doi:10.1080/15440478.2020.1867943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Narciso CRP, Reis AHS, Mendes JF, Nogueira ND, Mendes RF. Potential for the use of coconut husk in the production of medium density particleboard. Waste Biomass Valorization. 2021;12(3):1647–58. doi:10.1007/s12649-020-01099-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Echeverría-Maggi E, Flores-Alés V, Martín-del-Río JJ. Reuse of banana fiber and peanut shells for the design of new prefabricated products for buildings. Rev De La Construcción. 2022;21(2):461–72. doi:10.7764/rdlc.21.2.461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Sivaranjana P, Arumugaprabu V. A brief review on mechanical and thermal properties of banana fiber based hybrid composites. SN Appl Sci. 2021;3(2):176. doi:10.1007/s42452-021-04216-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Agarwal A, Shaida B, Rastogi M, Singh NB. Food packaging materials with special reference to biopolymers-properties and applications. Chem Afr. 2023;6(1):117–44. doi:10.1007/s42250-022-00446-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Hierro-Iglesias C, Chimphango A, Thornley P, Fernández-Castané A. Opportunities for the development of cassava waste biorefineries for the production of polyhydroxyalkanoates in Sub-Saharan Africa. Biomass Bioenergy. 2022;166:106600. doi:10.1016/j.biombioe.2022.106600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Wongphan P, Panrong T, Harnkarnsujarit N. Effect of different modified starches on physical, morphological, thermomechanical, barrier and biodegradation properties of cassava starch and polybutylene adipate terephthalate blend film. Food Packag Shelf Life. 2022;32(2):100844. doi:10.1016/j.fpsl.2022.100844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Khurshida S, Das MJ, Deka SC, Sit N. Effect of dual modification sequence on physicochemical, pasting, rheological and digestibility properties of cassava starch modified by acetic acid and ultrasound. Int J Biol Macromol. 2021;188(6):649–56. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.08.062. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Widyorini R, Nugraha PA, Rahman MZA, Prayitno TA. Bonding ability of a new adhesive composed of citric acid-sucrose for particleboard. BioResources. 2016;11(2):4526–35. doi:10.15376/biores.11.2.4526-4535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. ASTM D1037-12(2020). Standard test methods for evaluating properties of wood-base fiber and particle panel materials. Conshohocken, PA, USA: West. 2020. doi:10.1520/D1037-12R20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Fagbemi OD, Andrew JE, Sithole B. Beneficiation of wood sawdust into cellulose nanocrystals for application as a bio-binder in the manufacture of particleboard. Biomass Convers Biorefin. 2023;13(13):11645–56. doi:10.1007/s13399-021-02015-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Choupani Chaydarreh K, Lin X, Guan L, Hu C. Interaction between particle size and mixing ratio on porosity and properties of tea oil camellia (Camellia oleifera Abel.) shells-based particleboard. J Wood Sci. 2022;68(1):43. doi:10.1186/s10086-022-02052-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Ferrandez-Garcia A, Ferrandez-Garcia MT, Garcia-Ortuño T, Ferrandez-Villena M. Influence of the density in binderless particleboards made from sorghum. Agronomy. 2022;12(6):1387. doi:10.3390/agronomy12061387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Abotbina W, Sapuan SM, Ilyas RA, Sultan MH, Alkbir MM, Sulaiman S, et al. Recent developments in cassava (Manihot esculenta) based biocomposites and their potential industrial applications: a comprehensive review. Materials. 2022;15(19):6992. doi:10.3390/ma15196992. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Wronka A, Kowaluk G. The influence of multiple mechanical recycling of particleboards on their selected mechanical and physical properties. Materials. 2022;15(23):8487. doi:10.3390/ma15238487. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Shi L, Hu C, Zhang W, Chen R, Ye Y, Fan Z, et al. Effects of adhesive residues in wood particles on the properties of particleboard. Ind Crops Prod. 2024;214:118526. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2024.118526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Copak A, Jirouš-Rajković V, Španić N, Miklečić J. The impact of post-manufacture treatments on the surface characteristics important for finishing of OSB and particleboard. Forests. 2021;12(8):975. doi:10.3390/f12080975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Anter N, Guida MY, Chennani A, Boussetta A, Moubarik A, Barakat A, et al. Allylation of cellulose microfibers for hydrosilylation with various hydrosilanes and hydrosiloxanes, and their application in corn-starch-Mimosa tannin (CSMT) adhesive to improve particleboard properties. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;278(Pt 2):134828. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.134828. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Lee SH, Lum WC, Boon JG, Kristak L, Antov P, Pędzik M, et al. Particleboard from agricultural biomass and recycled wood waste: a review. J Mater Res Technol. 2022;20(2):4630–58. doi:10.1016/j.jmrt.2022.08.166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Karlinasari L, Sejati PS, Adzkia U, Arinana A, Hiziroglu S. Some of the physical and mechanical properties of particleboard made from betung bamboo (Dendrocalamus asper). Appl Sci. 2021;11(8):3682. doi:10.3390/app11083682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Tigabe S, Atalie D, Gideon RK. Physical properties characterization of polyvinyl acetate composite reinforced with jute fibers filled with rice husk and sawdust. J Nat Fibres. 2022;19(13):5928–39. doi:10.1080/15440478.2021.1902899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Pereira GF, Iwakiri S, Trianoski R, Rios PD, Raia RZ. Influence of thermal modification on the physical and mechanical properties of Eucalyptus badjensis mixed particleboard/OSB panels. Floresta. 2021;51(2):419. doi:10.5380/rf.v51i2.69403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Uemura Silva V, Nascimento MF, Resende Oliveira P, Panzera TH, Rezende MO, Silva DAL, et al. Circular vs. linear economy of building materials: a case study for particleboards made of recycled wood and biopolymer vs. conventional particleboards. Constr Build Mater. 2021;285:122906. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.122906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Melo RR, Muhl M, Stangerlin DM, Alfenas RF, Rodolfo FJr. Properties of particleboards submitted to heat treatments. Ciência Florest. 2018;28(2):776–83. doi:10.5902/1980509832109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. da Costa LJ, de Oliveira Paula EA, de Melo RR, Scatolino MV, de Albuquerque FB, de Oliveira RRA, et al. Improvement of the properties of hardboard with heat treatment application. Matéria Rio J. 2023;28(1):e20220291. doi:10.1590/1517-7076-rmat-2022-0291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Kibet T, Tuigong DR, Maube O, Mwasiagi JI. Mechanical properties of particleboard made from leather shavings and waste papers. Cogent Eng. 2022;9(1):2076350. doi:10.1080/23311916.2022.2076350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Laksono AD, Susanto TF, Dikman R, Awali J, Sasria N, Wardhani IY. Mechanical properties of particleboards produced from wasted mixed sengon (Paraserianthes falcataria (L.) Nielsen) and bagasse particles. Mater Today Proc. 2022;65(2):2927–33. doi:10.1016/j.matpr.2022.01.199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Mensah P, de Melo RR, Bih FK, Mitchual SJ, Santos Pimenta A, Pedrosa TD, et al. Sustainable panels from cocoa (Theobroma cacao) wood wastes bonded with cassava starch and urea-formaldehyde. J Compos Sci. 2024;8(11):444. doi:10.3390/jcs8110444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. JIS A 5908. Japanese industrial standard-particleboards. Tokyo, Japan: Japan Standards Association (JSA); 2003. [Google Scholar]

44. Zakaria R, Bawon P, Lee SH, Salim S, Lum WC, Al-Edrus SSO, et al. Properties of particleboard from oil palm biomasses bonded with citric acid and tapioca starch. Polymers. 2021;13(20):3494. doi:10.3390/polym13203494. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Sivakumar AA, Canales C, Roco-Videla Á, Chávez M. Development of thermoplastic cassava starch composites with banana leaf fibre. Sustainability. 2022;14(19):12732. doi:10.3390/su141912732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Ansi A208.1-1999 PB. America national standard-particle board. Gaithersburg, MD, USA: National Particleboards Association; 1999. [Google Scholar]

47. EN 312-2:1996. Particleboards-specifications–part 2: requirements for general purpose boards for use in dry conditions. Brussels, Belgium: European Committee for Standardization; 2005. [Google Scholar]

48. Martins RSF, Gonçalves FG, de Alcântara Segundinho PG, Lelis RCC, Paes JB, Lopez YM, et al. Investigation of agro-industrial lignocellulosic wastes in fabrication of particleboard for construction use. J Build Eng. 2021;43:102903. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2021.102903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. de Oliveira Paula EA, de Melo RR, de Albuquerque FB, da Silva FM, Scatolino MV, Santos Pimenta A, et al. Does the layer configuration of loofah (Luffa cylindrica) affect the mechanical properties of polymeric composites? J Compos Sci. 2024;8(6):223. doi:10.3390/jcs8060223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools