Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Characteristics of Wood Sponge from Sengon (Falcataria moluccana) Wood Manufacturing through a Multistage Delignification Process

1 Forest Products Department, Faculty of Forestry and Environment, IPB University, Bogor, 16680, Indonesia

2 Research Center for Biomass and Bioproducts, National Research and Innovation Agency, Cibinong, 16911, Indonesia

* Corresponding Authors: Imam Wahyudi. Email: ; Sarah Augustina. Email:

Journal of Renewable Materials 2025, 13(8), 1661-1681. https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2025.02024-0081

Received 29 December 2024; Accepted 28 April 2025; Issue published 22 August 2025

Abstract

Adsorbents with three-dimensional porous structures have gained widespread attention due to their unique characteristics, including a large surface area, high porosity, and excellent absorption capacity. One of the products is the wood sponge. The key to successfully producing wood sponges lies in an optimal multistage delignification process, which is particularly influenced by wood species, solvent, time, and temperature. The aim of this research was to analyze the characteristics of wood sponge derived from sengon wood (Falcataria moluccana Miq.) after multistage delignification. The process involved delignification using NaOH and Na2SO3 solutions at 100°C for 8, 9 and 10 h, followed by further delignification in H2O2 solution at 100°C for 1, 2, 3, and 4 h. The samples were then frozen at 20°C for 24 h and freeze-dried at 53°C for 48 h. The results showed that wood sponges treated at 100°C exhibited lower density, larger pore diameters, brighter color, and superior absorption capacity compared to untreated wood and sponges treated at room temperature for 24 h. FTIR analysis confirmed a decrease in wavelength between 1032–1035 cm−1, indicating the degradation of hemicellulose and lignin. XRD analysis revealed that crystallinity increased as amorphous content decreased with prolonged delignification. The wood sponges demonstrated good porosity, with an absorption capacity ranging from 0.65 to 2.24 g/g. The optimal treatment suggested in this research was multistage delignification using NaOH and Na2SO3 solution for 10 h, followed by a 1 h treatment with H2O2 solution.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Over the past few years, adsorbents with three-dimensional porous structures have gained widespread attention due to their ability to interact with specific substances and their unique geometrical surface structures. Conventional adsorbents can be made from various materials, including polymer particles [1], graphene [2], zeolites [3], aluminium oxide [4], metal-organic frameworks/MOFs [5], and silica gel [6]. These materials possess several advantages, including a large surface area, high porosity with a unique pore structure, tunable surface property, and high absorption capacity [1,7]. Such adsorbents are widely used in many applications, including wastewater purification [2], gas separation/storage, carbon capture and storage/CCS [8], and catalyst support [9]. According to Ketabchi et al. and Brickett et al. [10,11], adsorption technology plays a crucial role in the environmental sector by contributing to pollution control and resource utilization through advanced material technologies. However, many conventional adsorbents require high process energy and ideal conditions to maintain their lifespan and performance [12], and often suffer from low scalability and high synthesis costs [13]. In contrast, carbon-based adsorbents offer lower costs, enhanced stability, and ease of regeneration; however, they may have limitations in adsorption capacity and selectivity compared to more advanced materials [14]. Apart from these adsorbents, lignocellulosic biomass has emerged as a promising source for bio-based adsorbent materials, which offers unique characteristics such as a naturally porous structure, renewability, biodegradability, and cost-effectiveness [15].

Wood is categorized as lignocellulosic biomass and holds great potential as a raw material for porous adsorbent due to its naturally porous structure, viscoelastic properties, anisotropic and orthotropic nature. Its matrix is formed by interconnections between cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, along with organic and inorganic extractives contained within the structure [16]. These characteristics align with the findings of Chen et al. [1], who stated that a good adsorbent material should be a solid material with a well-defined porous structure, a large contact area, and contain abundance of functional groups that determine its adsorption selectivity and capacity. Additionally, wood is a low-cost, environmentally friendly biopolymer composite with renewable and biodegradable properties, making it suitable for various products. One product that can be made is wood sponge, a green and sustainable porous adsorbent material. Wood sponge is an intermediate product that can be used in a wide range of applications, including absorbent [17], bioscaffold [18], energy storage devices and sensors [19], aerogels [20], insulation materials [21,22], catalyst supports, and hydrogels [23]. According to Keplinger et al. [18], the top-down approach, which utilizes wood as the base material, is a promising alternative for producing environmentally friendly and sustainable functional materials.

Wood sponges can be made through a delignification process using specific chemical solutions and controlled conditions. This process selectively removes most lignin and hemicellulose from the cell wall while preserving the cellulose skeleton, maintaining the physical integrity and morphology of the wood structure. The characteristics of wood sponges are significantly affected by the manufacturing process. Based on Zhang et al. [24], wood sponges were successfully produced from balsa wood (Ochroma spp.) through a multistage delignification using NaOH and Na2SO3 for 5 h, followed by H2O2 for 1 h, which resulted in a porous material with good thermal insulation, ultralight weight (1/3 from the initial weight of balsa wood), and high porosity. Zhu et al. [25] reported that a multistage delignification process using NaOH and Na2SO3, followed by H2O2 for 12 h on balsa wood (Ochroma spp.), resulted in a transparent material with improved mechanical properties. In addition, Li et al. [26] reported that multi-step delignification using NaOH and Na2SO3 for 7 h, followed by 2% (v/v) H2O2 on balsa wood (Ochroma spp.), produced a wood skeleton suitable for use in solar evaporators. Their findings indicated that the wood skeleton exhibited high salt-rejection capability (88.7%), high water absorption capacity, and low thermal conductivity (0.109 W/m/K). Wang [27] stated that wood sponges can achieve high porosity (96.47%) and good resilience, along with excellent absorption capacity for oils and organic solvents (2441–17,300 mg/g). Furthermore, Zhang et al. [28] highlighted that wood sponges possess an exceptionally high oil absorption capacity (79–195 times their weight in oil). Despite these promising characteristics, particularly for adsorbent applications, wood sponge fabrication has been largely limited to balsa wood (Ochroma spp.) due to its ideal inherent properties, including low density and high porosity [27].

Observing the characteristics of wood sponges made from different low-density wood species presents both an intriguing and complex challenge. To address this, sengon wood (Falcataria moluccana Miq.) is being introduced as the raw material for wood sponge fabrication due to its several advantages, such as its classification as a fast-growing species with a short harvest cycle, ease of cultivation, high productivity, and multifunctionality [29]. Sengon wood (F. moluccana Miq.), fast-growing species native to Southeast Asia, is known for its lightweight, low-density, and relatively high strength-to-weight ratio, making it suitable for various industrial applications [30]. Therefore, the main focus of this research is to analyze the characteristics of wood sponges derived from sengon wood (F. moluccana Miq.) through a multistage delignification process. This includes identifying the optimal synthesis conditions using sodium hydroxide (NaOH), sodium sulfite (Na2SO3), and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2); and examining the changes in wood properties between untreated and wood sponges, particularly the changes in its physical properties (density, weight loss, color measurement), morphological features (porosity, pores structure, absorption capacity), and chemical properties (analyzed using FTIR and XRD). The first delignification stage, using a mixture of NaOH and Na2SO3 is designed to break down lignin and hemicellulose within the wood structure. The second delignification stage, using H2O2, further oxidizes and removes residual and remaining lignin after the latter treatment.

A log of sengon wood (F. moluccana Miq.) sourced from Cikabayan Experimental Garden, IPB University, Bogor, Indonesia, was cut using a circular saw into smaller samples with dimensions of 20 mm × 20 mm × 10 mm (length × width × height), and oven-dried at 103°C ± 2°C for 24 h before use. All chemicals used in this study were commercially available and purchased from distributor. Sodium hydroxide (NaOH, purity ≥ 98%), sodium sulfite (Na2SO3, purity ≥ 98%), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2, purity ≥ 30%), isopropyl alcohol (IPA, C3H7OH) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Jakarta, Indonesia) distributors, and AHM Oil MPX2 engine oil purchased from a local market in Bogor, Indonesia.

2.2.1 Wood Sponge Manufacturing

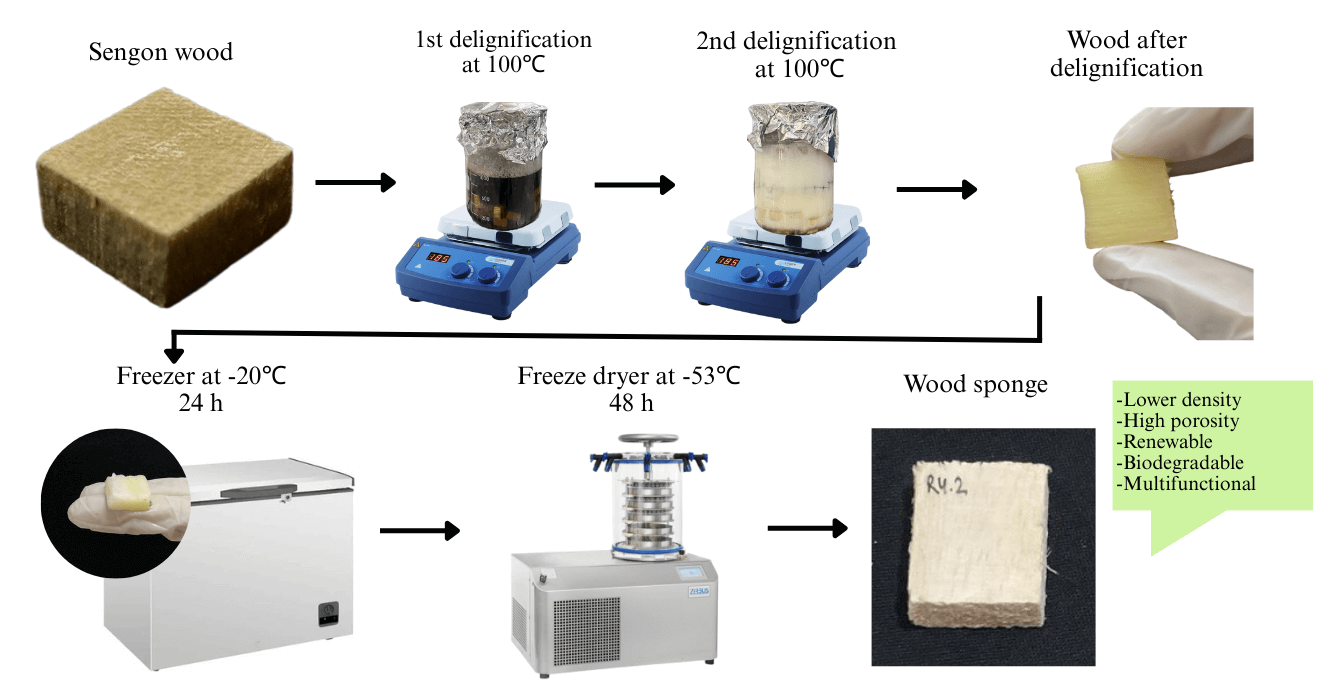

Wood sponges can be manufactured through a multistage delignification process using several chemicals to entirely or partially remove lignin compounds from the wood structure [26]. The multistage delignification process can be carried out through the following steps (Fig. 1): (1) A 2% (w/v) NaOH and Na2SO3 in a 1:1 ratio was prepared and mixed together until the solution reached a pH of 13; (2) The samples were hot immersed within this solution at 100°C for 8, 9, and 10 h (first delignification); (3) Washed three times using distilled water to eliminate any residual chemical from the first delignification stage; (4) The samples were hot immersed again within 5% (w/v) H2O2 solution at 100°C for 1, 2, 3, and 4 h (second delignification); (5) Re-washed using distilled water three times to remove any remaining chemical residue and any impurities; (6) Frozen at a temperature of −20°C for 24 h; (7) Freeze-dried at a temperature of −53°C for two days to obtain a wood sponge with a porous structure.

Figure 1: Flow chart for the manufacturing process of wood sponge derived from sengon wood

Several characteristics of wood sponges under different conditions, as outlined in Table 1, were assessed. These included physical properties (density, weight loss, and color measurement), morphological features (porosity, pore structure, and absorption capacity), and chemical properties (analyzed using FTIR and XRD). A total of 210 samples were used for all the treatments applied (15 replications × 14 treatments).

2.2.2 Physical Properties of Wood Sponge

The physical properties, including density and weight loss values, were analyzed according to the British Standard 373-1957 [31]. The density and weight loss (WL) of both untreated and wood sponge samples were calculated using the formula presented as Eqs. (1) and (2):

where, DA is the weight of sample in air-dried condition (g), OD is the dimensions of sample in oven-dried condition (g), and VA is the volume of sample in air-dried condition (cm3).

2.2.3 Color Measurement of Wood Sponge

Color measurement was carried out by using a colorimeter analysis [32]. The change in brightness level (ΔL) and overall color change (ΔE) of untreated and wood sponge samples were calculated using the formula presented as Eqs. (3) and (4):

where, ΔL is the difference in L values before and after treatment, Δa is the difference in the a value before and after treatment, Δb is the difference in the b value before and after treatment, and ΔE is the overall color changes before and after treatment.

Meanwhile, the classification of the degree of color change is presented in the Table 2, as described by Valverde and Moya [33].

2.2.4 Morphology Characteristics

The morphological characteristics analyzed in this research encompassed both macroscopic and microscopic features. The macroscopic features, such as color and texture characteristic, were assessed based on the guidelines outlined in SNI 8491:2018 [34]. Meanwhile, the microscopic features, including pore distribution, diameter, and porosity, were observed in the cross-sectional plane by slicing with a cutter and capturing images using a microscope camera with 50× magnification. The microscopic images were then analyzed and measured using the ImageJ 1.47V software to determine the latter parameters. The porosity of the wood sponge was calculated using the formula [35], presented as Eq. (5):

where,

2.2.5 Characterization of Wood Sponge

Further characterization of untreated wood and wood sponge was examined using a field emission scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM, JEOL JSM-6510LV, Tokyo, Japan). The samples were subjected to vacuum-drying at 40°C for 24 h. Subsequently, their cross-sections were sputter-coated with gold (Au) using a JEOL JEC-3000FC Auto fine coater (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) at 30 mA for 120 s. Finally, the samples were examined under a SEM (JEOL JSM-6510LV, Tokyo, Japan) operating at an acceleration voltage of 15 kV. Multiple micrographs at various magnifications were acquired for each sample group.

The functional groups of untreated wood and wood sponge were determined using Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) with a Universal Attenuated Total Reflectance (UATR) accessory equipped with a diamond plate (PerkinElmer Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). For this analysis, 2 mg of powder sample (30–40 mesh) was subjected to scanning from 400 to 4000 cm−1 with a resolution of 4 cm−1 at room temperature. Meanwhile, crystallinity was assessed with an X-ray diffractometer/XRD (D/max 2200, Rigaku, Tokyo, Japan) over a range of 10° to 80° at a scanning speed of 4°/min.

The untreated wood and sponge samples were immersed in isopropyl alcohol and engine oil at room temperature for 24 h [35] until fully saturated within each solution. The solvent absorption capacity (M) within both solutions were determined by weighing the sample before and after absorption. The M value was calculated using the formula presented as Eq. (6):

where,

The data for the characteristics of wood sponge under various conditions were presented as the average and standard deviation. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to assess the effect of the treatment applied, specifically on their physical properties and morphological characteristics of wood sponges. If significant differences were observed among factors or their interactions, Duncan’s multiple range test was conducted using IBM SPSS 23.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

3.1 Density and Porosity of Wood Sponge

Wood density refers to the amount of material comprising the cell walls of wood cells and other components that contribute to the wood’s strength characteristics [36]. Fig. 2 presents the density values of untreated and wood sponges derived from sengon wood under different treatments. It can be seen that the density tended to decrease as the prolongation of the delignification period. This phenomenon was consistent with the ANOVA results, which showed a significant effect of delignification process on density values. It can be seen that the density started to decrease by 21.88%, 11.11%, and 11.54% after applying the delignification process for 8, 9, and 10 h using NaOH, respectively. Novia et al. [37] observed that prolonged delignification process leads to a more significant degradation of lignin and hemicellulose. During delignification, density tended to decrease due to the breakdown of lignin and hemicellulose. This occurs because NaOH solution effectively disrupts the ether bonds linking lignin to cellulose, promoting lignin degradation [38,39]. These values were significantly decreased with the increase of multistage delignification period using H2O2 for 1–4 h. After applying multistage delignification for total synthesis of 14 h (N10H4), the density tended to decrease by 14%, from 0.37 to 0.23 g/cm3, compared to untreated wood (Fig. 2). These findings align with the study conducted by Song et al. [40], who observed a similar density reduction of balsa wood after multistage delignification with the same solution, decreasing from 0.14 to 0.05 g/cm3. Similarly, Garemark et al. [23] reported a decrease in the density of delignified balsa wood from 0.11 to 0.08 g/cm3.

Figure 2: Density values of wood sponge derived from sengon wood under different treatment conditions (Note: Letters above the graph denote significant differences according to Duncan’s 5% significance level test)

Moreover, applying different delignification temperatures significantly affected the final density values of wood sponges. The utilization of delignification temperature at 100°C during multistage delignification resulted in a substantially lower density than those delignified at room temperature for 24 h. The delignified samples at room temperature maintained their density with values nearly identical to those of untreated wood. This finding proven that higher temperatures could significantly accelerate the delignification process compared to room temperature conditions. The application of higher temperatures facilitate the removal of lignin and hemicellulose from the wood structure. According to Lismeri et al. [41], higher temperatures provide additional energy for the reaction, promoting the breakdown of bonds within lignin and hemicellulose chains. This process resulted in the formation of pure cellulose fibers/layers and the creation of the ‘new void’ within the wood structure. The different phenomenon reported by Garemark et al. [23] who observed a slight increase in density values after delignification process compared to untreated wood, likely due to wood shrinkage.

Apart from the reducing density phenomenon, the multistage delignification process could also significantly improve the porosity of wood sponges. As presented in Table 3, the porosity values after multistage delignification process ranged from 78.17% ± 0.02% and 84.43% ± 0.03%, increased by 12.16% compared to untreated wood. The untreated sample had the lowest porosity (75.28% ± 0.03%), likely due to the presence of lignin and hemicellulose within the wood cell wall structure. Lignin could act as a reinforcement agent within the wood’s cell walls, resulting in fewer and more dense pores. The increase in porosity indicates that removing lignin and hemicellulose could effectively open up more spaces within the wood structure. In addition, lignin removal causes parenchyma cells to shrink and deteriorate, expanding the specific surface area and further increasing porosity [41,42]. Li et al. [43] reported that the delignification process removes nearly all lignin, forming numerous nano-sized pores and releasing cellulose fibers. According to Song et al. [40], eliminating lignin and hemicellulose from the wood structure significantly transforms its porous structure, changing it from irregular formations to stacked or even a curved layer.

As stated above, the density tended to decrease with the increase of the multistage delignification period, leading to a higher porosity values in wood sponges derived from sengon wood. This phenomenon was proven by a significant negative correlation between density and porosity (y = −0.0149x + 1.486; R2 = 0.99), as shown in Fig. 3. Higher porosity reflects the presence of more void spaces in the wood structure, which significantly decreases its density. The delignification process removes lignin and hemicellulose, key structural components of wood, thereby expanding the spaces between cellulose fibers. Kumar et al. [42] noted that increased porosity through delignification strongly impacts the wood’s mechanical and physical properties, including density values. Furthermore, the removal of lignin enhances porosity of delignified wood, providing more space for polymer infiltration [44]. Since lignin acts as a reinforcing component within cell walls, its removal allows for the formation of larger and more numerous pores, further enhancing porosity. These findings were essential for enhancing the absorption capacity and surface area of the wood sponge.

Figure 3: Relationship between density and porosity of wood sponge derived from sengon wood under different treatment conditions

3.2 Weight Loss of Wood Sponge

Weight loss refers to the reduction in wood mass caused by the delignification process over a specific period. Fig. 4 presents the weight loss values of untreated and wood sponges derived from sengon wood under different treatments. It can be seen that the weight loss tended to increase as the delignification period lasted longer. This phenomenon was consistent with the ANOVA results, which showed a significant effect of the delignification process on weight loss values. As shown in Fig. 4, weight loss increased by 61.31% ± 4.36%, 16.15% ± 1.75%, 10.65% ± 1.47% after applying the delignification process for 8, 9, and 10 h using NaOH, respectively. Similarly, Fajriutami et al. [45] found that extending NaOH treatment duration and concentration significantly enhances weight loss values. However, excessively long processing times can lead to cellulose degradation, as NaOH can break down some cellulose bonds [46]. NaOH as the primary chemical in the delignification process plays a crucial role by effectively breaks down lignin structures. Additionally, Na2SO3 serves as a complementary active component with a greater nucleophilicity than hydroxyl ions, further enhancing lignin removal efficiency [47,48].

Figure 4: Weight loss of wood sponge derived from sengon wood under different treatment conditions (Note: Letters above the graph denote significant differences according to Duncan’s 5% significance level test)

Weight loss values significantly increased as the multistage delignification process using H2O2 was extended from 1 to 4 h. After a cumulative 14-h multistage delignification process (N10H4), weight loss increased up to 30% from 15.49% ± 1.09% to 30.00% ± 8.34% compared to untreated wood (Fig. 4). These results align with those reported by Song et al. [40], who observed 79.3% weight loss after subjecting delignification process with NaOH, Na2SO3, and H2O2 solvents. Applying H2O2 in the second stage of delignification process acts as a bleaching agent, which is directly degrade residual lignin by breaking short chains, making it more soluble during washing [41]. According to Hidayat et al. [48], extending the bleaching process increases the reactivity of H2O2 in degrading lignin and hemicellulose. According to Irfanto and Padil [49], prolonging the bleaching duration improves reaction efficiency, with a 60-min bleaching time effectively increasing the cellulose-α content. Furthermore, optimizing the bleaching duration effectively disrupts chemical bonds in lignin and hemicellulose chains, leading to a more significant release of cellulose [38,41]. A study by Zhang et al. [50] found that utilizing H2O2 in the delignification process, combined with the evaporation method, proved to be more effective at removing lignin from wood. This reduction in lignin content occurs due to the reaction of H2O2 with lignin bonds, breaking them into shorter fragments and rendering lignin more soluble during water washing [51]. Additionally, H2O2 can break Cα-Cβ bonds in lignin molecules and open lignin rings [52]. A similar phenomenon was also reported by Garemark et al. [23] who observed 18% weight loss after delignification process and increased to 52% after further treatment with ionic liquid. This increase is likely due to the ionic liquid’s effectiveness in removing lignin and other components from the wood.

Moreover, applying different delignification temperatures significantly affected the weight loss values. Wood sponges delignified at room temperature exhibited a lower weight loss (13.96% ± 8.34%) than those delignified samples at 100°C. This could be due to higher temperature applied accelerating the delignification process. This finding is consistent with the results reported by Kininge and Gogate [53], who reported an increase in delignification efficiency from 55.44% to 66.64% when the temperature rose from 50°C to 70°C. Similarly, Ismail et al. [54] found that using a eutectic solvent system at high temperatures significantly improved lignin removal while keeping the cellulose fibers in good condition, as long as the temperature was controlled correctly.

Furthermore, the untreated samples that underwent only freeze-dried exhibited minimal weight loss, as shown in Fig. 4. In contrast, the samples subjected to a combination of delignification and freeze-drying processes exhibited a significantly higher weight loss value. This is attributed to the removal of moisture content from the material’s structure through lyophilization [55]. During freeze-drying, the water within the wood structure transitions directly from solid to vapor phase via sublimation, without passing through the liquid phase [56]. This process generates a porous structure or cavities within the wood sponge, reducing the total weight of the wood sponge.

A more significant weight loss leads to a decrease in wood sponge’s density due to the removal of chemical components during the delignification process, primarily lignin, hemicellulose, and some cellulose. This phenomenon was proven by a significant negative correlation between density and weight loss (y = −0.005x + 0.38; R2 = 0.91), as can be seen in Fig. 5. This negative correlation suggests that as weight loss increases during the delignification process, the material’s density decreases. The delignification process degrades the chemical components of the wood, particularly lignin and hemicellulose, leading to significant weight loss [42]. This reduction is directly associated with a decrease in the structural density of the wood, ultimately lowering the overall density of the wood sponge.

Figure 5: Relationship between density and weight loss of wood sponge derived from sengon wood in different treatment conditions

The step-by-step delignification process effectively removed lignin component from a wood sponge derived from sengon wood, thus significantly enhancing its brightness (ΔL) and overall color (ΔE) compared to untreated wood. As shown in Fig. 6a, the brightness (ΔL) of the wood sponge ranged from 70.85% to 84.26% after the multistage delignification process. These values were increased by 16.10% compared with untreated wood. The untreated sample exhibited the lowest ΔL values (65.64%), likely due to the presence of lignin within the wood structure [37].

Figure 6: Color change of wood sponge derived from sengon wood under different treatment conditions, (a) brightness level, (b) total color changes (Note: Letters above the graph denote significant differences according to Duncan’s 5% significance level test)

In addition, the color changes values (ΔE) of the wood sponge ranged from 12.51 to 16.22 after the multistage delignification process, indicating a complete color change (ΔE > 12), as shown in Fig. 6b. This phenomenon was consistent with the ANOVA results, which showed a significant effect of the delignification process on total color changes of wood sponge. The second delignification stage using H2O2 had a major impact on the wood sponge’s color by removing residual lignin, oxidizing chromophores compounds, and introducing a bleaching effect. The application of H2O2 in the subsequent delignification process was classified as a bleaching process aimed at eliminating pigmentation components from the wood structure. Zuidar et al. [57] found that applying H2O2 in the delignification process effectively brighten the wood color. Delignification is a technique that can change the wood’s color from brown to white due to the removal of almost all lignin chromophores. This phenomenon was also reported by Chen et al. [19], Song et al. [58], and Song et al. [59]. In general, the color of organic compounds is produced by the absorption of light by chromophore groups, which consists of C-C and C-O bonds [60]. Therefore, it is crucial to eliminate or disperse lignin residues, which intensely absorb photons from the chromophore clusters to achieve a white-colored sample.

As shown in Fig. 7, the wood sponge derived from sengon wood sample became progressively brighter as the delignification process time increased. The delignification process is influenced by the type of chemicals used, duration and temperature applied. According to Kusuma et al. [61], higher temperatures accelerate lignin degradation, enhancing color changes, and resulting in a brighter color of samples. This phenomenon agreed with Popescu et al. [62], stating that higher temperatures affect the chromophore components in wood, leading to noticeable color changes. Additionally, Yildiz et al. [63] demonstrated that increasing the temperature during thermal treatment can further brighten the wood; however, excessively high temperatures applied over extended periods can cause wood darkening due to the formation of carbonyl groups from thermal degradation products.

Figure 7: The difference between sample before and after multistage delignification, (a) untreated, (b) N8H1, (c) N24H24

As a result of the delignification process, wood retains its structurally porous, anisotropic, and hierarchical characteristics, similar to natural wood, while also developing nanopores within the cell walls. Delignification reduces lignin content, increasing wood porosity by forming voids in areas previously filled by lignin. As can be seen in Table 4, the pore diameter of the wood sponge ranged from 0.161 to 0.229 mm after multistage delignification. Those values were higher than untreated wood (0.143 mm). This phenomenon was also supported by cross-sectional images of the wood sponge, which showed a clear-hollow structure with less deposited content in the pore areas than that of untreated wood (Fig. 8). Although the pore diameter values appeared to increase with prolonged delignification process, ANOVA analysis indicated that these differences were not statistically significant.

Figure 8: Cross-sectional images of wood sponge derived from sengon wood under different treatment conditions at 50× magnification: (a) UT (untreated), (b) N8H1, (c) N9H1, (d) N10H1, (e) N8H3, (f) N9H3, (g) N10H3

This increase in pore diameter values occurred due to the depletion of chemical constituents during the delignification process. Nanofibrils networks within the lumen developed as the thinning of the cell walls due to the removal of lignin [23]. According to Li et al. [44], removing nearly all lignin during delignification effectively releases cellulose fibrils and generates numerous newly formed nanoscale pores in the wood structure. The removal of lignin and hemicellulose caused the central lamella to disappear, exposing nanoscale pores on the cell wall. Freeze-drying the delignified wood is essential for maintaining the stability of the naturally aligned cellulosic structure and preserving its inherent porosity and pore size, which are critical for developing various functional materials [42].

Based on the SEM micrographs, the cell wall of wood sponge became thinner and numerous ‘new pores’ or microvoids formed within the lumen cells after multistage delignification process, as indicated by the arrows in Fig. 9. According to Cai et al. [7], the initial honeycomb structure undergoes further transformation after delignification process, evolving into a spring-like structure due to the stacking of several wave-shaped layers.

Figure 9: SEM micrographs for wood sponge derived from sengon wood in cross sections direction at 350× magnification. (a) untreated, (b) N8H1, (c) N10H3

The elemental content of both untreated and wood sponge after the multistage delignification process was analyzed using energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS). The EDS spectrum showed carbon (C) and oxygen (O) as the primary elements. The C content in untreated wood was 52.51%, while in delignified wood sponges (N8H1 and N10H3 treatments), it increased to 54.2% and 56.06%, respectively. In contrast, the O content in untreated wood was 40.7%, increasing to 43.8% for the N8H1 treatment but decreasing to 38.12% for the N10H3 treatment. These results indicated that the C percentage in the delignified wood sponge increased while the O percentage decreased. This is due to the degradation of lignin and hemicellulose during the alkaline treatment process [6]. The observed increase in the C content suggests that delignification removes lignin and hemicellulose and modifies the wood’s composition by elevating its carbon content [51]. The rise in the O content with the N8H1 treatment may be attributed to the reduction of lignin, which leads to the incorporating of additional oxygen functional groups into the wood structure. Conversely, the reduction in the O content observed in the N10H3 treatment could be linked to more complex chemical structural changes. In this case, the extended delignification process significantly alters the wood structure, thus decreasing bound oxygen content [44].

FTIR analysis was used to examine the degradation of chemical components during the multistage delignification process of wood sponges derived from sengon wood. As shown in Fig. 10, delignification process caused an alteration in the absorption spectra, causing shifting in the wavelengths ranging from 1032 to 3352 cm−1. After delignification, the spectra of the wood sponge exhibited a reduction in absorption spectra compared to untreated wood, primarily due to the changes in the molecular bonds of methyl groups (C-H) and C-O groups. A stretching absorption band at 1035 cm−1 can be attributed to the vibration of the C-O bond in cellulose, showed a slight decrease in intensity with no substantial alteration. These results suggest that delignification has a minimal effect on the cellulose portion, focusing primarily on removing lignin and hemicellulose components [64].

Figure 10: FTIR of wood sponge derived from sengon wood under different treatment conditions

Following delignification with NaOH, the absence of absorption peak in the spectrum at wavelengths 1731–1744 cm−1, associated with carboxyl stretching and C=O groups of esters in hemicellulose, was observed in Fig. 10. This phenomenon could be due to the degradation of lignin and hemicellulose in the wood structure [22,27,50]. The decrease in lignin content confirms the effectiveness of the delignification process, as NaOH efficiently disrupts the lignin structure. The addition of Na2SO3 as an active component further enhances delignification efficiency [37,48]. During the bleaching process, the presence of lignin and hemicellulose is indicated by a reduction at 3355 cm−1, corresponding to -OH stretching [25,62]. Additionally, the freeze-drying process can influence the structure and composition of wood, as changes in wavelength reflect modifications in the methyl cluster caused by mechanical or thermal effects during freezing and drying. The delignification process requires an optimal duration to effectively remove chemical components. FTIR analysis showed a reduction in transmittance for the 10-h immersion with a combination of NaOH and Na2SO3, followed by a 3-h treatment with H2O2 (N10H3). However, prolonged delignification period may damage chemical components, indicating that the optimal condition for producing wood sponge was a 10-h immersion with NaOH and Na2SO3, followed by a 1-h treatment with H2O2 (N10H1).

The relative crystallinities of the samples were calculated using an X-ray diffractometer (Fig. 11). X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis showed a reduction in the percentage of amorphous content within the samples. This reduction indicates that delignification process effectively removes a significant portion of lignin, which previously hindered the crystallinity of the cellulose structure. According to Cai et al. [7], after the degradation of hemicellulose and lignin, the cellulose framework remains intact, forming a wood sponge with high porosity and very low density—approximately 60% lower than untreated wood. The observed increase in crystallinity is attributed to lignin removal, allowing for a more ordered and dense cellulose structure. The increase in crystallinity indicates a more organized and structured wood material, which aligns with the primary goal of delignification: to enhance wood quality by improving its mechanical and chemical properties [22,38].

Figure 11: XRD of wood sponge derived from sengon wood in different treatment conditions

Although the crystallinity and amorphous content were relatively fluctuated, a clear trend showed that the crystallinity increased while amorphous content decreased with extended delignification time. This trend suggests that prolonged delignification facilitates the more extensive removal of lignin and hemicellulose, thereby increasing the proportion of crystalline cellulose. The reduction in amorphous content is directly linked with the increase in crystallinity, indicating the gradual formation of a more organized cellulose structure over time [48]. Sun et al. [22] reported that an extended delignification process can significantly enhance crystallinity while reducing amorphous values within the cellulose structure.

Variations in XRD peak intensities further indicate that the multistage delignification process could alter the characteristics of wood sponges derived from sengon wood by increasing its porosity. This observation aligns with the findings by Cai et al. [7], who reported that the degradation of hemicellulose and lignin leaves behind a cellulose framework that forms a highly porous with low-density wood sponge. Similarly, Zhang et al. [24] confirmed that delignification enhances wood porosity and reduces its density, resulting in a lighter material more suitable for various applications.

The absorption capacity of wood sponge samples was tested by immersing them in isopropyl alcohol and engine oil. As shown in Table 5, the absorption capacity of wood sponge derived from sengon wood ranged from 0.65 to 2.24 g/g, and was notably lower compared to other reported absorbents such as wood aerogel (20 g/g), delignified epoxy (15 g/g), poly-g-polystyrene (4–21 g/g), and chitin sponges (20 g/g) [65–68], still demonstrates the potential of wood sponge as an absorbent material. The lower absorption capacity compared to other advanced materials can be attributed to the complex synthetic procedures and expensive raw materials, which restricted their potential for industrial applications. On the other hand, the wood sponge offers significant advantages because it uses inexpensive and abundant raw materials. It provides a much more accessible solution for industrial applications, with simple preparation methods and excellent recyclability [27].

The untreated wood exhibited the lowest absorption capacity compared to the wood sponge subjected to a multistage delignification process. This lower absorption capacity can be attributed to the high lignin content in the untreated wood structure, which has hydrophobic properties that inhibit the absorption of liquid and oil [44]. In contrast, the wood sponge demonstrated a significantly higher absorption capacity due to the removal of lignin and hemicellulose during the delignification process, which increased its porosity (Table 5). These findings align with the results of Wang and Okubayashi [17], who reported that the removal of lignin and hemicellulose from wood reduces its density and enhances its porosity, enabling more excellent liquid absorption. The wood sponge’s layered structure, high porosity, and excellent lipophilic properties further contribute to its superior liquid absorption capacity [27]. The porosity of the modified wood sponge is a crucial factor, as it contributes to the high absorption capacity by providing more space for the liquid to be absorbed. The removal of lignin and hemicellulose also reduced the density of the material, making the wood sponge more porous and improving its ability to absorb liquids.

Based on Wang [27] reported that after the silylation treatment, the wood sponge derived from balsa wood exhibited a very high absorption capacity for oil and organic solvents, ranging from 2.4 to 17.3 g/g, indicating excellent absorption properties. On the other hand, Cai et al. [7] found that the oil absorption capacity of the wood sponge from poplar wood reached 25 g/g. The current study shows that each sample had a higher absorption capacity for isopropyl alcohol compared to engine oil. This difference can be attributed to the chemical characteristics of the liquids. Isopropyl alcohol is polar, which allows it to be more easily absorbed by the wood sponge, which contains cellulose. In contrast, engine oil is non-polar and has higher viscosity, making it more difficult for the wood pores to absorb. Based on Xiong et al. [66], the hydrolysis method tends to destroy the cellulose crystal structure, leading to poor mechanical properties of wood. Therefore, the treatment methods must be carefully optimized to balance the enhancement of absorption capacity with the retention of mechanical integrity.

The wood sponge was successfully synthesized using a multistage delignification process. With extended delignification periods, the wood sponge exhibits lower density, more significant weight loss, increased porosity, and a noticeably brighter appearance. Wood sponge delignified at room temperature did not experience considerable degradation of hemicellulose and lignin, unlike delignified samples with a combination of elevated temperature and freeze-drying. The reduction in density and weight loss is attributed to the degradation of chemical components such as lignin and hemicellulose during the multistage delignification process. FTIR analysis reveals changes in absorption or spectral shifts within the wavelength ranges of 1032–3352 cm−1, indicating the degradation of lignin and hemicellulose.

Morphology changes in wood sponges derived from sengon wood after multistage delignification included larger pores, a smoother texture, a softer structure, and a whitish-yellow color than that of untreated wood. XRD results showed that crystallinity tended to increase while amorphous content decrease with prolonged delignification time. The wood sponge exhibited high porosity, with an absorption capacity ranging from 0.65 to 2.24 g/g. Based on the results obtained, the optimal condition for fabricating of wood sponge derived from sengon wood involved a multistage delignification process using NaOH and Na2SO3 for 10 h, followed by a 1-h treatment with H2O2 solution (N10H3). This specific combination and duration enhanced lignin removal efficiency and improved the overall quality of the sponge.

Future research should focus on evaluating the long-term stability and recyclability of wood sponge, particularly their durability and absorption retention. Additionally, analyzing pore size distribution and comparing performance with commercial sponges could provide valuable insights. Further optimization of processing conditions and isolating delignification effects could enhance material properties and sustainability.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank IPB University, especially Department of Forest Products Technology for their invaluable guidance and support. Special appreciation goes to BRIN for its financial and facilities support. Our families and friends deserve thanks for their unwavering encouragement.

Funding Statement: This study was funded by New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization of Japan (NEDO)—NET ZERO EMISSION TA 2023 BATCH-2—with the Grant Number 28/III.5/HK/2023. Research Program by Research Organization of Nanotechnology and Materials, National Research and Innovation Agency (Grant Number B-1484/III.10/TK.01.00/2/2024). Research Program by Research Assistant, National Research and Innovation Agency (Grant Number B-6932/II.5/S1.06.01/9/2023).

Author Contributions: Aisyah Zakiya Darajat: Conceptualization; Investigation; Methodology; Visualization; Writing—original draft. Imam Wahyudi: Writing—review & editing. Narto: Investigation. Adik Bahanawan: Investigation. Sarah Augustina: Resources; Investigation; Methodology; Visualization; Writing—review & editing. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Chen D, Wang L, Ma Y, Yang W. Super-adsorbent material based on functional polymer particles with a multilevel porous structure. NPG Asia Mat. 2016;8(8):1–9. doi:10.1038/am.2016.117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Priya VN, Rajkumar M, Mobika J, Sibi SPL. Adsorption of As (V) ions from aqueous solution by carboxymethyl cellulose incorporated layered double hydroxide/reduced graphene oxide nanocomposites: isotherm and kinetic studies. Environ Technol Innov. 2022;26(3):1–15. doi:10.1016/j.eti.2022.102268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Pérez-Botella E, Valencia S, Rey F. Zeolites in adsorption processes: state of the art and future prospects. Chem Rev. 2022;122(24):17647–95. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.2c00140. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Salahudeen N, Ahmed AS, Al-Muhtaseb AH, Dauda M, Waziri SM, Jibril BY, et al. Synthesis, characterization and adsorption study of nano-sized activated alumina synthesized from kaolin using novel method. Power Technol. 2015;280:266–72. doi:10.1016/j.powtec.2015.04.024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Zhou HC, Li JR, Sculley J. Metal-organic frameworks for separations. ACS Pub. 2012;112(2):869–932. doi:10.1021/cr200190s. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Chung TW, Chung CC. Increase in the amount of adsorption on modified silica gel by using neutron flux irradiation. Chem Eng Sci. 1988;53(16):2967–72. doi:10.1016/S0009-2509(98)00101-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Cai Y, Wu Y, Yang F, Gan J, Wang Y, Zhang J. Wood sponge reinforced with polyvinyl alcohol for sustainable oil-water separation. ACS Omega. 2021;6(19):12866–76. doi:10.1021/ACSomega.1c01280. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Tiwari SC, Bhardwaj A, Nigam KDP, Pant KK, Upadhyayula S. A strategy of development and selection of absorbent for efficient CO2 capture: an overview of properties and performance. Process Saf Environ Prot. 2022;163(1–3):244–73. doi:10.1016/j.psep.2022.05.025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Han L, Liu Q, Zhang Y, Lin K, Xu G, Wang Q, et al. A novel hybrid iron-calcium catalyst/absorbent for enhanced hydrogen production via catalytic tar reforming with in-situ CO2 capture. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2020;45(18):10709–23. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2020.01.243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Ketabchi MR, Babamohammadi S, Davies WG, Gorbounov M, Soltani SM. Latest advances and challenges in carbon capture using bio-based sorbents: a state-of-the-art review. Carbon Capt Sci Technol. 2023;6(1):1–20. doi:10.1016/j.ccst.2022.100087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Brickett L, Munson R, Litynski J. Large pilot-scale testing of advanced carbon capture technologies. Fuel. 2020;268:117–69. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2020.117169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Chao W, Sun X, Li Y, Cao G, Wang R, Wang C, et al. Enhanced directional seawater desalination using a structure guided wood aerogel. ACS Appl Mate Interfaces. 2020;12(19):22387–97. doi:10.1021/acsami.0c05902. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Roy S, Philip FA, Olivera EF, Singh G, Joseph S, Yaday RM, et al. Functional wood for carbon dioxide capture. Cell Rep Physic Sci. 2023;4(2):101269. doi:10.1016/j.xcrp.2023.101269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Lucaci AR, Bulgariu D, Ahmad I, Lisa G, Mocanu AM, Bulgariu L. Potential use of biochar from various waste biomass as biosorbent in Co(II) removal processes. Water. 2019;11(8):15–65. doi:10.3390/w11081565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Mujtaba M, Fraceto LF, Fazeli M, Mukherjee S, Savassa SM, Medeiros GS, et al. Lignocellulosic biomass from agricultural waste to the circular economy: a review with focus on biofuels, biocomposites and bioplastics. J Clean Prod. 2023;402(18):1–23. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.136815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Schniewind AP, Barrett JD. Wood as a linear orthotropic viscoelastic material. Wood Sci Technol. 1972;6(1):43–57. doi:10.1007/BF00351807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Wang C, Okubayashi S. Polyethyleneimine-crosslinked cellulose aerogel forcombustion CO2 capture. Carbo Polymers. 2019;225:115248. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.115248. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Keplinger T, Wang X, Burgert I. Nanofibrillated cellulose composites and wood derived scaffolds for functional materials. J Mat Chem. 2019;7(7):2981–92. doi:10.1039/C8TA10711D. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Chen Z, Zhou H, Hu Y, Lai H, Liu L, Zhong L, et al. Wood-derived lightweight and elastic carbon aerogel for pressure sensing and energy storage. Adv Func Mat. 2020;30(17):1910292–303. [Google Scholar]

20. Chen C, Ding R, Yang S, Wang J, Chen W, Zong L, et al. Development of thermal insulation packaging film based on poly(vinyl alcohol) incorporated with silica aerogel for food packaging application. Food Sci Technol. 2020;129(11):1–9. doi:10.1016/j.lwt.2020.109568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Mekonnen BT, Ding W, Liu H, Guo S, Pang X, Ding Z, et al. Preparation of aerogel and its application progress in coatings: a mini overview. J Leat Sci Eng. 2021;3(1):25. doi:10.1186/s42825-021-00067-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Sun H, Bi H, Lin X, Cai L, Xu M. Lightweight, anisotropic, compressible, and thermally-insulating wood aerogels with aligned cellulose fibers. Polymers. 2020;12(1):165. doi:10.3390/polym12010165. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Garemark J, Perea-Buceta JE, del Cerro DR, Hall S, Berke B, Kilpeläinen I, et al. Nanostructurally controllable strong wood aerogel toward efficient thermal insulation. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2022;14(21):24697–707. doi:10.1021/acsami.2c04584. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Zhang Q, Li L, Jiang B, Zhang H, He N, Yang S, et al. Flexible and mildew-resistant wood-derived aerogel for stable and efficient solar desalination. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2020;12(25):28179–87. doi:10.1021/acsami.0c05806. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Zhu M, Song J, Li T, Gong A, Wang Y, Dai J, et al. Highly anisotropic highly transparent wood composites. Adv Mater. 2016;28(26):5181–7. doi:10.1002/adma.201600427. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Li L, He N, Yang S, Zhang Q, Zhang H, Wang B, et al. Strong trough hydrogel solar evaporator with wood skeleton construction enabling ultra-durable brine desalination. EcoMat. 2023;5(1):e12282. doi:10.1002/eom2.12282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Wang S. Chemical modication of nanostructured wood for functional biocomposites [doctoral dissertation]. Stockholm, Sweden: KTH Royal Institute of Technology; 2021. [Google Scholar]

28. Zhang C, Cai T, Zhang SG, Mu P, Liu Y, Cui J. Wood sponge for oil-water separation. Polymers. 2024;16(16):2362. doi:10.3390/polym16162362. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Anggraeni I. Control of gall rust disease (Uromycladium tepperianum (Sacc.) Mc. Alpin) on sengon tree (Falcataria moluccana (Miq.) Barneby & J.W. Grimes) in Panjalu Kabupaten Ciamis, Jawa Barat. J Pen Hut Tanam. 2010;7(5):273–8. doi:10.20886/jpht.2010.7.5.273-278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Fadia SL, Rahayu IS, Nawawi DS, Ismail R, Prihartini E. The physical and magnetic properties of sengon (Falcataria moluccana Miq.) impregnated with synthesized magnetite nanoparticles. J Sylva Lestari. 2023;11(3):1–19. doi:10.23960/jsl.v11i3.761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. BS 373:1957. Methods of testing small clear specimens of timber. London, UK: British Standard House; 1957. [Google Scholar]

32. Hui YH. Encyclopedia of food science and tecnology. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1992. 2972 p. [Google Scholar]

33. Valverde JC, Moya R. Correlation and modeling between color variation and quality of the surface between accelerated and natural tropical weathering in Acacia mangium, Cedrela odorata and Tectona grandis wood with two coating. Color Res Appl. 2014;39(5):519–29. doi:10.1002/col.21826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. SNI 8491-2018. Identifikasi jenis kayu secara makroskopis. Jakarta, Indonesia: Badan Standarisasi Nasional; 2018. (In Indonesian). [Google Scholar]

35. Wang Z, Lin S, Li X, Zou H, Zhuo B, Ti P, et al. Optimization and absorption performance of wood sponge. J Mater Sci. 2021;56(14):8479–96. doi:10.1007/s10853-020-05547-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Bowyer JL, Shmulsky R, Haygreen JG. Forest product and wood science. An introduction. 4th ed. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2003. 554 p. [Google Scholar]

37. Novia, Pareek VK, Agustina TE. Bioethanol production from sodium hydroxide-dilute sulfuric acid pretreatment of rice husk via simultaneous saccharification and fermentation. MATEC Web Conf. 2017;101(3):1–5. doi:10.1051/matecconf/201710102013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Kang KE, Jeong GT, Park DH. Pretreatment of rapeseed straw by sodium hydroxide. Biop Biosys Eng. 2012;35(5):705–13. doi:10.1007/s00449-011-0650-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Wang M, Zhou D, Wang Y, Wei S, Yang W, Kuang M, et al. Bioethanol production from cotton stalk: a comparative study of various pretreatments. Fuel. 2016;184(1):527–32. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2016.07.061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Song J, Chen C, Wang C, Kuang Y, Zhu S, Li Y, et al. Superflexible wood. ACS Appl Mater Inter. 2017;9(28):23520–7. doi:10.1021/acsami.7b06529. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Lismeri L, Darni Y, Sanjaya MD, Immadudin MI. Effect of temperature and time on alkali pretreatment of cellulose isolation from banana stem waste. J Chem Pro Eng. 2019;4(1):18–22. doi:10.33536/jcpe.v4i1.319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Kumar A, Jyske T, Petric M. Delignified wood from understanding the hierarchically aligned cellulosic structures to creating novel functional materials: a review. Adv Sus Syst. 2021;5(5):200–51. doi:10.1002/adsu.202000251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Li T, Song J, Zhao X, Yang Z, Pastel G, Xu S, et al. Anisotropic, lightweight, strong, and super thermally insulating nanowood with naturally aligned nanocellulose. Sci Adv. 2018;4(3):3724–34. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aar3724. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Li Y, Fu Q, Yu S, Yan M, Berglund L. Optically transparent wood from a nanoporous cellulosic template: combining functional and structural performance. ACS Pub. 2016;17(4):1358–64. doi:10.1021/acs.biomac.6b00145. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Fajriutami T, Fatriasari W, Hermiati E. Effects of alkaline pretreatment of sugarcane bagasse on pulp characterization and reducing sugar production. J Riset Ind. 2016;10(3):147–61. [Google Scholar]

46. Han Y, Wang L. Sodium alginate/carboxymethyl cellulose films containing pyrogallic acid: physical and antibacterial properties. J Sci Food Agr. 2017;97(4):1295–301. doi:10.1002/jsfa.7863. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Harti S. Modifikasi warna kayu sengon (Falcataria moluccana) dengan delignifikasi dan infiltrasi polivinil pirolidon untuk meningkatkan estetika kayu [master’s thesis]. Bogor, Indonesia: IPB University; 2019. (In Indonesian). [Google Scholar]

48. Hidayat W, Febrianto F, Purusatama BD, Kim NH. Effects of heat treatment on the color change and dimensional stability of Gmelina arborea and Melia azedarach woods. E3S Web Conf. 2018;68:03010. doi:10.1051/e3sconf/20186803010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Irfanto H, Padil AY. Proses bleaching pelepah sawit hasil hidrolisis sebagai bahan baku nitroselulosa dengan variasi suhu dan waktu reaksi [master’s thesis]. Riau: Universitas Riau; 2014. (In Indonesian). [Google Scholar]

50. Zhang J, Ying Y, Yi X, Han W, Yin L, Zheng Y, et al. H2O2 solution steaming combined method to cellulose skeleton for transparent wood infiltrated with cellulose acetate. Polymers. 2023;15(1733):1–9. doi:10.3390/polym15071733. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Fengel D, Wegener G. Wood chemistry, ultrastructure, reactions. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1984. 613 p. [Google Scholar]

52. Jayanudin, Hartono R, Jamil NH. Pengaruh konsentrasi dan waktu pemutihan serat daun nanas menggunakan hidrogen peroksida. Sem Rek Kim Proses. 2010;20(1):1–6. (In Indonesian). [Google Scholar]

53. Kininge MM, Gogate PR. Intensification of alkaline delignification of sugarcane bagasse using ultrasound assisted approach. Ultra Sonoc. 2022;82(2):1–11. doi:10.1016/j.ultsonch.2021.105870. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Ismail MY, Sirvio JA, Veli-Pekka R, Patanen M, Karvonen V, Liimatainen H. Delignifcation of wood fbers using a eutectic carvacrol-methanesulfonic acid mixture analyses of the structure and fractional distribution of lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose. Cell. 2024;31(8):4881–94. doi:10.1007/s10570-024-05892-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Nowak D, Jakubczyk E. The freeze-drying of foods the characteristic of the process course and the effect of its parameters on the physical properties of food materials. Foods. 2020;9(10):1488. doi:10.3390/foods9101488. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Merivaara A, Zini J, Koivunotko E, Valkonen S, Korhonen O, Fernandes FM, et al. Preservation of biomaterials and cells by freeze-drying: change of paradigm. J Con Release. 2021;336:480–98. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2021.06.042. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Zuidar AS, Hidayati S, Pulungan RJA. Study of delignification on formacell process from palm oil empty fruit bunches using H2O2 in acetic acid media. J Tek Ind Hasil Pert. 2014;19(2):194–204. doi:10.23960/jtihp.v19i2.194%20-%20204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Song J, Chen C, Zhu S, Zhu M, Dai J, Ray U, et al. Processing bulk natural wood into a high performance structural material. Nature. 2018;554(7691):224–8. doi:10.1038/nature25476. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Song J, Chen C, Yang Z, Kuang Y, Li T, Li Y, et al. Highly compressible, anisotropic aerogel with aligned cellulose nanofibers. ACS Nano. 2018;12(1):140–7. doi:10.1021/acsnano.7b04246. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Szymczyk M. Chromophore. In: Shamey R, editor. Encyclopedia of color science and technology. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2023. p. 154–9. [Google Scholar]

61. Kusuma HD, Kurnia I, Haryono, Saputra A. Pengaruh suhu terhadap ekstraksi lignin dari batang pohon kelapa sawit menggunakan metode organosolv. Ion Tech. 2024;5(1):25–31. (In Indonesian). doi:10.62702/ion.v5i1.103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Popescu CM, Popescu MC, Vasile C. Structural analysis of photodegraded lime wood by means of FTIR and 2D IR correlation spectroscopy. Int J Biol Macromol. 2011;48(4):667–75. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2011.02.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Yildiz S, Tomak ED, Yildiz C, Ustaomer D. Effect of artificial weathering on the properties of heat treated wood. polymer degradation and stability. Polymer Deg Stab. 2013;98(8):1419–27. doi:10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2013.05.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Wang K, Liu X, Tan Y, Zhang W, Zhang S, Li J. Two-dimensional membrane and three dimensional bulk aerogel materials via top-down wood nanotechnology for multibehavioral and reusable oil/water separation. Chem Eng J. 2019;371:769–80. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2019.04.108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Fu Q, Ansari F, Zhou Q, Berglund LA. Wood nanotechnology for strong, mesoporous, and hydrophobic biocomposites for selective separation of oil/water mixtures. ACS Nano. 2018;12(3):2222–30. doi:10.1021/acsnano.8b00005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Xiong Y, Xu L, Nie K, Jin C, Sun Q, Xu X. Green construction of an oil-water separator at room temperature and its promotion to an adsorption membrane. Langmuir. 2019;35(34):11071–9. doi:10.1021/acs.langmuir.9b01480. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Liang Y, Liu D, Chen H. Poly(methyl methacrylate-copentaerythritol tetraacrylate-co-butyl methacrylate)-g-polystyrene: synthesis and high oil-absorption property. J Polym Sci. 2013;51(9):1963–8. doi:10.1002/pola.26576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Duan B, Gao H, He M, Zhang L. Hydrophobic modification on surface of chitin sponges for highly effective separation of oil. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2014;6(22):19933–42. doi:10.1021/am505414y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools