Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Iron Modified Opuntia ficus-indica Cladode Powder as a Novel Adsorbent for Dyes Molecules

1 Laboratory of Materials and Environment for Sustainable Development, LR18ES10, University of Tunis El Manar, 9, Avenue Dr. Zoheir Safi, Tunis, 1006, Tunisia

2 Faculty of Science, University of Sfax, LMSE BP 802-3018, Sfax, 3000, Tunisia

* Corresponding Author: Mehrzia Krimi. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Biobased Materials for Advanced Applications )

Journal of Renewable Materials 2025, 13(8), 1623-1644. https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2025.02025-0023

Received 08 February 2025; Accepted 07 April 2025; Issue published 22 August 2025

Abstract

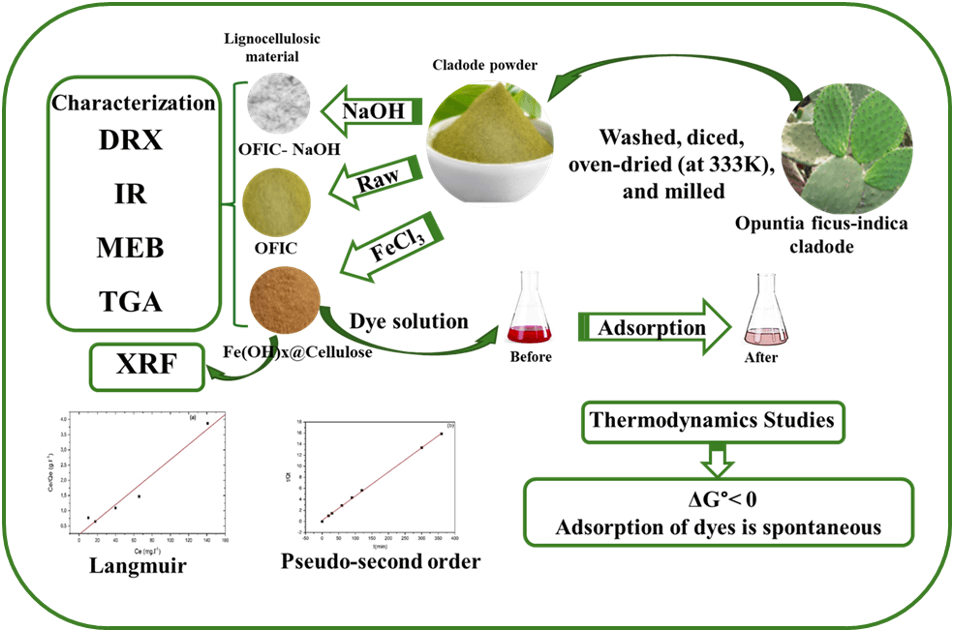

In this study, Opuntia ficus-indica cladode powder (OFIC), locally sourced from Rabta in Tunis, was utilized as a novel, eco-friendly adsorbent in both raw and iron(III) chloride-modified forms. The presence of iron in the modified material was confirmed by X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF). The neat and modified biomass were characterized by X-ray diffraction (XRD), Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR), thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and their usefulness as adsorbent for cationic Neutral Red (NR) and anionic Congo Red (CR) dyes were explored under batch conditions. Equilibrium studies revealed that the iron-modified Fe(OH)x@Cellulose adsorbent exhibited superior adsorption capabilities for both dyes compared to the raw material. Moreover, CR dye was more effectively adsorbed by Fe(OH)x@Cellulose than NR. The adsorption isotherms for both dyes were fitted. The results demonstrated that the adsorption of both NR and CR dyes onto the biosorbent Fe(OH)x@Cellulose was closely followed by the Langmuir model, with R2 values of 0.980 and 0.973 for NR and CR, respectively, and the pseudo-second-order kinetic model better depicted the adsorption kinetic. Thermodynamic analysis revealed a negative enthalpy value (−67.15 kJ/mol) for NR adsorption, suggesting an exothermic process, while a positive enthalpy value (3.99 kJ/mol) was observed for CR adsorption, indicating an endothermic process.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

In recent years, adsorption has been established as one of the most widely used methods for the removal of dyes from water and wastewater. Its high efficiency, ease of use, and the abundance of various adsorbents make it a sustainable and cost-effective environmental solution [1]. Numerous studies have explored the use of various adsorbents, for dye removal, including activated carbon [2], activated carbon composites such as Peat-AC [3], Moringa oleifera leaves, Borassus flabellifer, Mangifera indica [4], pithecellobium dulce carbon [5], palm fruit bunch, date stones, and maize cobs [6], for dye removal. Opuntia ficus-indica cladodes, fruit pulp and peel mucilage and electrolytes have shown significant potential for the treatment of various types of wastewaters. These materials have exhibited remarkably high maximum sorption capacities and removal percentages for both dyes and metallic species. Biosorption capacities for dyes ranged from 125.4 to 1000 mg/g, whereas those for metallic species varied from 0.31 to 2251.56 mg/g. Although several factors, including local availability and treatment requirements, are crucial for comparing adsorbents [7], the cost aspect is often overlooked [8]. Biomass adsorbents rich in cellulose have demonstrated significant potential for removing micropollutants, including dyes, from aqueous solutions [9–12]. Several studies have demonstrated the potential of lignocellulosic-based materials as effective adsorbents for dyes. The adsorption efficiency can be further enhanced by chemical modification of the biomass waste. This includes oxidation [13], esterification [14], grafting of cationic sites [15], or hybridization with metal oxides [16,17]. In this regard, Opuntia ficus indica cladodes, primarily composed of water, carbohydrates (starch, cellulose, hemicellulose, pectin, and chlorophyll), proteins, lignin, and lipids (carotene), are widely available biomass growing naturally or farmed in arid regions such as north and south Africa, south America among others [18,19]. Over the last decades, research has been initiated to develop new environmentally friendly and cost-effective adsorbents from Opuntia ficus indica cladodes [20–22]. Findings indicate a moderate removal capacity, reaching up to 10 mg/g, which may be attributed to the low specific surface area. This limitation is due to the presence of natural minerals, primarily Ca(C2O4)·H2O (whewellite), covering the adsorbent surface [23,24]. To improve the adsorption capacity, new by-products are being developed by Djobbi et al. (2021) by modifying the surface of natural Opuntia ficus indica. Acid treatment significantly enhanced the adsorption capacity of Opuntia ficus indica for manganese cations in aqueous solutions, increasing the maximum capacity to 42.02 mg/g, substantially higher than the 20.8 mg/g capacity of untreated cactus [25]. Louati et al. (2018) investigated the potential of prickly pear cactus cladodes powder (PPCP) derived from Opuntia ficus indica as an eco-friendly and cost-effective biosorbent to remove Acid Orange 51 (AO51) and Reactive Red 75 (RR75) dyes, widely used in the textile industry [26]. A comparative study of Opuntia ficus indica sourced from Lomé and Marrakech was conducted by Degbe et al. Their experiments, using methylene blue solutions, revealed rapid initial elimination within the first 20 min for both adsorbents [27]. Further experiments were conducted to study the effects of pH, adsorbent mass, and adsorbate concentration on the adsorption process. The study found that at a pH of 12.5, the Marrakech cactus exhibited a maximum elimination of 72.38%, whereas the Lomé cactus reached 71.22% [7,27]. It’s important to note that composites of these materials with iron could be explored for their photocatalytic capabilities, which would extend their application beyond simple adsorption. Therefore, experiments in the dark are necessary to assess the adsorption behavior independently [28].

The primary objective of this research is to develop novel Fe(OH)x@Cellulose hybrid adsorbents utilizing the low-cost biomass, Opuntia ficus indica. Inspired by the successful application of Fe(OH)3@Cellulose fibers derived from cotton, which exhibited high adsorption capacity (689.65 mg/g) for CR dye [29], this study aims to create a similar system by modifying the surface of Opuntia ficus indica. This approach seeks to combine simplicity, high efficiency, low cost, and environmental friendliness, with the goal of developing a new product with significant potential for industrial applications. The adsorption performance of the modified biomass will be evaluated for NR and CR dye removal, and the structural properties of the synthesized materials will be characterized using XRD, FTIR, XRF and SEM.

Opuntia ficus-indica cladode powder (OFIC) was prepared and activated for use as an adsorbent. Cladodes were harvested in June from a plantation located in the La Rabta region of Tunis northern Tunisia. The chemicals used in the activation process were sodium hydroxide and iron(III) chloride hexahydrate (Scharlab S. L., Sentmenat, Spain).

2.1 Methods Preparation of Opuntia ficus-indica Cladodes Powder (OFIC)

Opuntia ficus-indica cladode powder was prepared following the method described by Djobbi et al. [25]. After removing the spines, the cladodes were carefully washed with ordinary tap water and rinsed with distilled water before being cut into small, 4 cm cubes. The cubes were dried in an oven at 333 K for 48 h and subsequently ground into a fine powder (40–80 μm) using a laboratory mill (Fig. 1). To remove hemicellulose, lignin, and excess minerals like whewellite and CaCO3 from the cladode surface, the powder was treated with a 15% aqueous sodium hydroxide solution. The suspension was subjected to a 4-h stirring period to facilitate thorough mixing, subsequently filtered, and then rinsed with distilled water until the washings exhibited a neutral pH. The chemically treated powder was dried overnight in an electric oven at 333 K, then ground and stored in clean, dry glass vials for future use (Fig. 1). The untreated material was designated as OFIC, while the sodium hydroxide-treated material was labeled OFIC-NaOH.

Figure 1: Process flowchart illustrating the sequential steps involved in sample material creation

To prepare Fe(OH)x@Cellulose, 0.25 g samples of OFIC were stirred in 500 mL of aqueous FeCl3 solutions (1 g·L−1) at a 1:2 mass ratio for 2 h at room temperature. The resulting solutions were filtered and washed with water until the pH reached neutrality. Analysis of the wash water revealed that 87.7% of the iron (0.151 g) was removed, indicating a retention of 12.3% (0.021 g) on the cellulose. The chemically treated powders, Fe(OH)x@Cellulose and OFIC-NaOH, were dried in an oven at 333 K for 4 h, and their final weights were recorded (Fig. 1).

2.2 Characterization of Raw and Treated OFIC

The crystalline structure of the raw and treated materials was investigated using X-ray diffraction (XRD) on a Bruker D8 diffractometer with Cu Kα1/Kα2 radiation (λ1 = 0.1540 nm, λ2 = 0.1544 nm). Data were collected from 5° to 60° using a Malvern Panalytical X’pert3 Powder diffractometer (Almelo, The Netherlands), equipped with a flat rotating sample holder and a 1D-PIXcell detector. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) analysis was performed using a Bruker Tensor 27 spectrophotometer (Billerica, MA, USA). KBr pellets were prepared for FTIR measurements, which were carried out within the 400–4000 cm−1 spectral range. This technique allowed for the investigation of vibrational properties and chemical bond information present in the materials. Subsequent analysis of the iron content in the metallic material was carried out by X-ray fluorescence spectrometry “Thermo Scientific Niton FXL model 959 (Waltham, MA, USA)”. The microstructure and morphology of samples were analyzed using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) at 3–5 kV acceleration voltage. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was conducted using a TGA 400 thermogravimetric analyser from Perkin Elmer (PerkinElmer, Shelton, SC, USA) under an airflow in the temperature range of 50°C–800°C at a heating rate of 10°C/min. The ash content was determined from the residue at 800°C, and the moisture content was calculated from the weight loss at 150°C.

2.3 Thermodynamics of Adsorption Processes

The following equation was used to determine the equilibrium adsorption capacity

where C0 (mg/L) is the initial dye concentration, Ce (mg/L) is the equilibrium dye concentration, V (L) is the solution volume and m (g) is the adsorbent mass.

To optimize dye removal processes, a fundamental understanding of dye-adsorbent interactions is crucial. Adsorption isotherms provide valuable insights into this relationship. The models applied to describe the dye adsorption onto the biosorbent (Fe(OH)x@Cellulose) involve the Langmuir, Freundlich, and Temkin equations [3,31]. Langmuir’s model describes adsorption as a process in which the molecules form a single layer on the surface of the adsorbent. It requires that the adsorbent has a fixed number of adsorption sites, each possessing identical binding energies for the molecules, while neglecting any interaction among the adsorbed species. The Langmuir isotherm can be illustrated by a linear equation:

where

using the Langmuir constant (K) and the initial concentration (C0), we can determine the adsorption behavior. If the calculated RL value is greater than 1, the adsorption is unfavorable and linear. If it’s between 0 and 1, it’s favorable. And if it’s zero, the adsorption is irreversible.

In contrast to Langmuir’s assumption of a constant adsorption enthalpy, Freundlich proposes a logarithmic relationship between enthalpy and surface coverage expressed as follows:

n and

Unlike Langmuir and Freundlich, the Temkin model accounts for changes in adsorption energy due to surface heterogeneity or intermolecular interactions. This relationship is expressed linearly as follows:

The Temkin model includes the parameters, B (J/mol), representing the heat of adsorption, and K (L/g), representing the equilibrium constant at the highest binding energy.

2.4 Adsorption Kinetics Models

To elucidate the adsorption mechanisms of NR and CR by Fe(OH)x@Cellulose, the pseudo-first-order, pseudo-second-order, and Elovich kinetic models were employed [33].

The pseudo-first-order Lagergren model is a mathematical equation that describes the rate of adsorption in liquid-solid systems, based on the amount of adsorbate taken up:

The pseudo-first order kinetic model uses

The pseudo-second-order adsorption kinetics can be modelled using Blanchard’s equation, which is given by:

Blanchard’s model includes

The Elovich model is widely used for describing activated chemical adsorption, particularly in systems with heterogeneous adsorption sites. The Elovich model is represented by the equation below:

The Elovich equation includes the parameters

The standard thermodynamic parameters, enthalpy (ΔH°), entropy (ΔS°), and Gibbs free energy (ΔG°), for the adsorption of dyes onto Fe(OH)x@Cellulose can be calculated using the given equations:

The relationship between ΔG°, ΔH°, and ΔS° is given by:

R is the gas constant with a value of 8.314 J/mol·K and T is the absolute temperature (K). Substituting Eq. (10) into Eq. (12) gives:

understanding the thermodynamic properties of an adsorption process is crucial for determining its feasibility and elucidating the binding mechanisms between dyes and adsorbents. Physisorption, a process driven by weak Van der Waals interactions, is characterized by a low heat of adsorption (20–40 kJ/mol), rapid kinetics, and reversibility [34].

The X-ray diffractograms of the raw material (OFIC) and the two modified materials (OFIC-NaOH and Fe(OH)x@Cellulose) are depicted in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: XRD patterns of: (a) OFIC, (b) OFIC-NaOH and (c) Fe(OH)x@Cellulose

The X-ray powder diffractogram (Fig. 2) of the fibers obtained through alkali treatment (Fig. 2b) shows three resolved peaks at approximately 2θ = 14.8°, 21.2°, and 29.3°. These peaks correspond to the

As depicted in Fig. 3, the treated biomass displayed comparable spectral features to the native biomass, suggesting that no chemical alterations occurred during the treatment process. FTIR spectra of OFIC, OFIC-NaOH, and Fe(OH)x@Cellulose all displayed broad bands in the 3000–3500 cm−1 region. These bands are characteristic of O-H stretching vibrations and are indicate hydrogen bonding interactions within the molecular structures of all three samples [25,28,36,37]. The “fingerprint” region (1800–400 cm−1) (Fig. 3) showed distinct bands at 1438, 1158, 1107, and 890 cm−1, characteristic of native cellulose

Figure 3: FT-IR spectra of: (a) Fe(OH)x@Cellulose, (b) OFIC-NaOH and (c) OFIC

3.3 X-Ray Fluorescence Analysis

X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy of the Fe(OH)x@Cellulose treated biomass material revealed a 18.2% iron content, indicating significant iron incorporation. This directly impacts the material’s adsorption capabilities. The substantial integration rate increases the material’s active surface area, providing more binding sites for dye molecules. Furthermore, the presence of iron modifies the cellulose’s physicochemical properties, enhancing interaction with adsorbable pollutants [43,44].

The morphology of the neat and modified fibers was studied using scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Fig. 4 illustrates SEM micrographs of OFIC, alkaline-treated OFIC, and Fe(OH)x@Cellulose. The raw OFIC surface presents a smooth, compact appearance with minimal visible channels [45]. The OFIC-NaOH and Fe(OH)x@Cellulose samples (Fig. 4c,e) displayed smoother morphological structures with a greater degree of softness compared to OFIC. The fibrous components observed in both the raw material and the treated biomasses were of similar dimensions, ranging from 2 to 11 μm. The modified biomass adsorbents exhibited distinct surface features, characterized by rough surfaces and numerous extended pores, indicating the creation of larger exposure zones and channels for pollutant uptake [46,47].

Figure 4: SEM images of (a, b) OFIC, (c, d) OFIC-NaOH and (e, f) Fe(OH)x@Cellulose

The raw biomass displayed whewellite crystals, ranging in size from 0.3 to 1 μm, distributed across its entire surface (Fig. 4b). Calcium oxalate crystals were not discernible on the surface of either OFIC-NaOH (Fig. 4d) or Fe(OH)x@Cellulose (Fig. 4f) [24]. The microcrystals observed on the surface of Fe(OH)x@Cellulose (Fig. 4f) are likely attributed to the formation of magnetite [48,49].

4 Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

TGA of the various samples (Fig. 5) was conducted to assess their thermal stability and changes in char content following different chemical treatments. The thermogravimetric analysis revealed multiple weight loss, depending on the treatment performed Table 1. For the neat OFIC, an initial weight loss at 100°C of about 12% is observed, corresponding to the evaporation of adsorbed water. This was followed by a second loss of about 5% at 150°C, attributed to the removal of water from oxalate monohydrate. Subsequently, a three-step degradation was identified, associated with the thermal degradation of lignocellulosic material in the biomass. The weight loss at 700°C presumably results from the decarbonation of oxalate contained in the OFIC, giving rise to a char content of about 20%, corresponding to mineral material contained in the biomass [50].

Figure 5: TG curves of: (a) OFIC, (b) OFIC-NaOH and (c) Fe(OH)x@Cellulose

OFIC-NaOH exhibited, after the first loss of adsorbed water at 100°C, a steep loss of about 50% occurred at 220°C, followed a second event at 420°C and a third event assigned to the thermal degradation of the lignocellulosic material. The weight loss at 700°C was much lower than that of neat OFIC, which is presumably due to the removal of a high fraction of oxalate and mineral material. This explains the decrease in char content to around 10% in OFIC-NaOH. In The iron-treated sample (Fe(OH)x@Cellulose), after the initial weight loss due to water evaporation, a sharp weight loss of more than 85% was observed at about 230°C. This indicates that the thermal degradation of all the lignocellulosic material occurring in one step. The FeCl3 treatment significantly reduced the mineral content of the biomass, leading to the lowest ash content (around 5%) observed among the samples [48,49,51–53].

5 Adsorption Properties of OFIC and Fe(OH)@Cellulose Modified Biomass

Reaching equilibrium in adsorption systems is essential, and contact time is a crucial parameter that plays a key role in defining the rate at which this equilibrium is established.

To determine the optimal contact time, the evolution of dye removal rates was studied. The curves presented in Fig. 6 demonstrate that both dyes exhibited enhanced adsorption by the treated cladode powder compared to the untreated material. Investigating the adsorption rate variation over time revealed that NR adsorption onto Fe(OH)x@Cellulose increased gradually (Fig. 6a), reaching a maximum of over 70% after two hours. The adsorption kinetic is quite rapid, reaching more than 65% within the first 20 min. Subsequently, the rate slowed significantly, suggesting saturation of the adsorbent’s surface sites. Continued, although slower, adsorption likely occurred through diffusion of the dye into the adsorbent’s pores. The treated material Fe(OH)x@Cellulose demonstrates exceptional CR dye removal efficiency (Fig. 6b). Rapid initial adsorption is observed with a 93.7% removal rate within 5 min, highlighting its swift initial action. Moreover, sustained high performance is evident, as it maintains a 94.15% removal rate after one hour, signifying consistent and effective dye removal. The high polarity of CR probably explains the different optimal contact times due to increased interactions with polar materials [47].

Figure 6: Effect of contact time on the sorption efficiency of dyes ((a): NR; (b): CR) by the OFIC and the Fe(OH)x@Cellulose at room temperature (20 ± 5°C) madsorbent = 150 mg; C0 = 100 mg·L−1 and pH ≈ 6.5

Experimental adsorption data for NR and CR dyes onto Fe(OH)x@Cellulose were analyzed using the Langmuir, Freundlich, and Temkin isotherm models. The results indicated that the adsorption of both NR and CR is best described by the Langmuir model, suggesting homogeneous adsorption sites and monolayer coverage. This conclusion was supported by high R2 values of 0.980 for NR and 0.973 for CR. These findings provide valuable insights into the adsorption mechanisms and can inform the design of more efficient adsorption processes. Thermodynamic parameters obtained from the isotherm models are tabulated in Table 2.

The high regression coefficients confirm that the Langmuir model accurately represents the experimental isotherms (Figs. 7 and 8), suggesting monolayer adsorption within the interlayer pores. The Langmuir constant and monolayer capacity values effectively characterize the adsorption behavior of the dyes.

Figure 7: (a) Langmuir isotherme, (b) Freundlich isotherm and (c) Temkin isotherm, for NR adsorption on Fe(OH)x@Cellulose

Figure 8: (a) Langmuir isotherme, (b) Freundlich isotherm and (c) Temkin isotherm, for CR adsorption on Fe(OH)x@Cellulose

The adsorption of NR and CR onto Fe(OH)x@Cellulose highlights distinct mechanisms. NR, with its amine (-NH2) and azo (-N=N-) groups, exhibits an adsorption mechanism based on strong hydrogen bonding with the hydroxyl (-OH) groups of cellulose. However, the formation of rigid complexes limits its adsorption capacity (Qm= 40.55 mg/g). CR, with its sulfonate groups (-

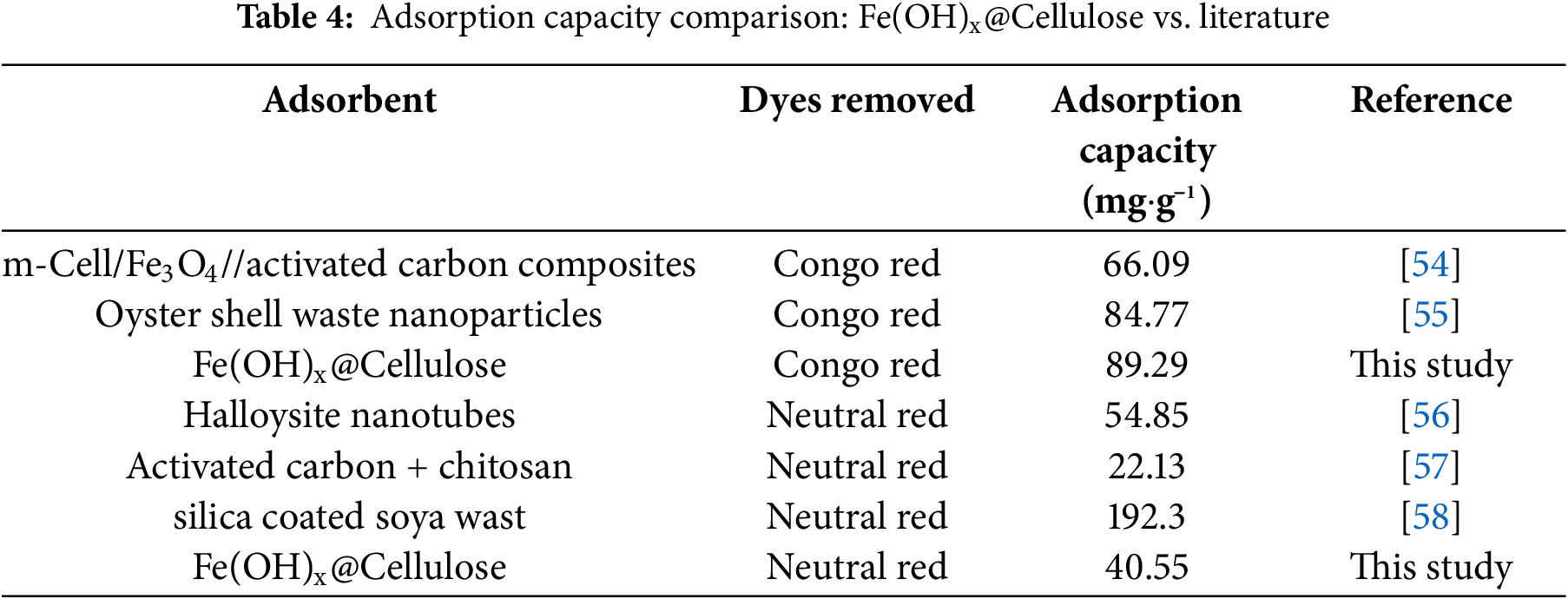

The separation factor RL was calculated for various dye concentrations and is presented in Table 3. As RL values for both CR and NR adsorption lie between 0 and 1, the adsorption process is favorable, indicating that Fe(OH)x@Cellulose is an effective bio-sorbent for removing these dyes from aqueous solution [25,54]. A comparison of the dye adsorption capacities of OFIC and OFIC-Cell with those found in similar research is summarized in Table 4.

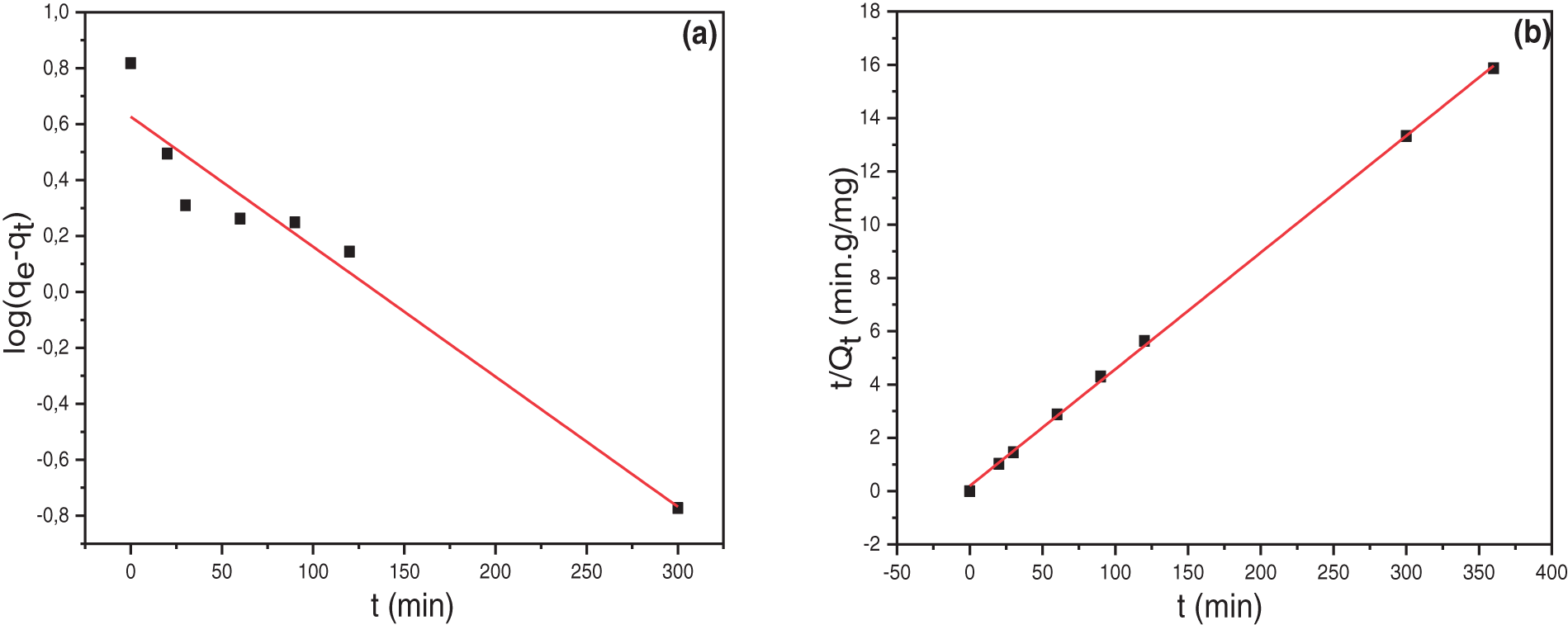

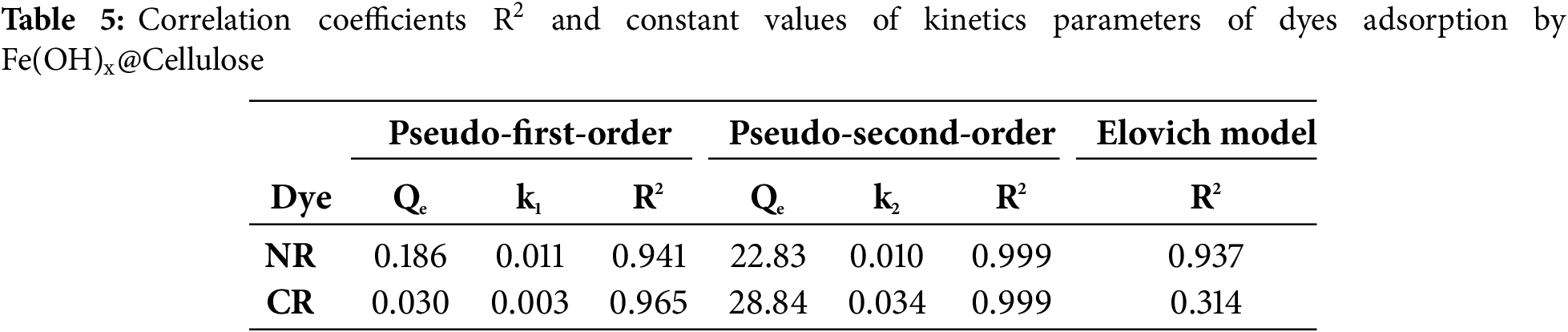

The kinetic study of NR and CR dye adsorption onto biomass was investigated. Pseudo-first-order, pseudo-second-order, and Elovich models were applied (Figs. 9 and 10). The obtained results indicated that the adsorption kinetics followed a pseudo-second-order model. The correlation coefficients for this model were high, reaching 0.999 and 0.989 for NR and CR adsorption onto Fe(OH)x@Cellulose, respectively.

Figure 9: (a) Pseudo-first-order, (b) Pseudo-second-order and (c) Elovich models, for NR on Fe(OH)x@Cellulose adsorbent

Figure 10: (a) Pseudo-first-order, (b) Pseudo-second-order and (c) Elovich models for CR on Fe(OH)x@Cellulose adsorbent

The calculated parameters for the different models are listed in Table 5. The Elovich model plot revealed a relatively high correlation coefficient for NR adsorption but a lower one for CR adsorption. This finding aligns with the ΔH values, suggesting physisorption for CR dye [6,59].

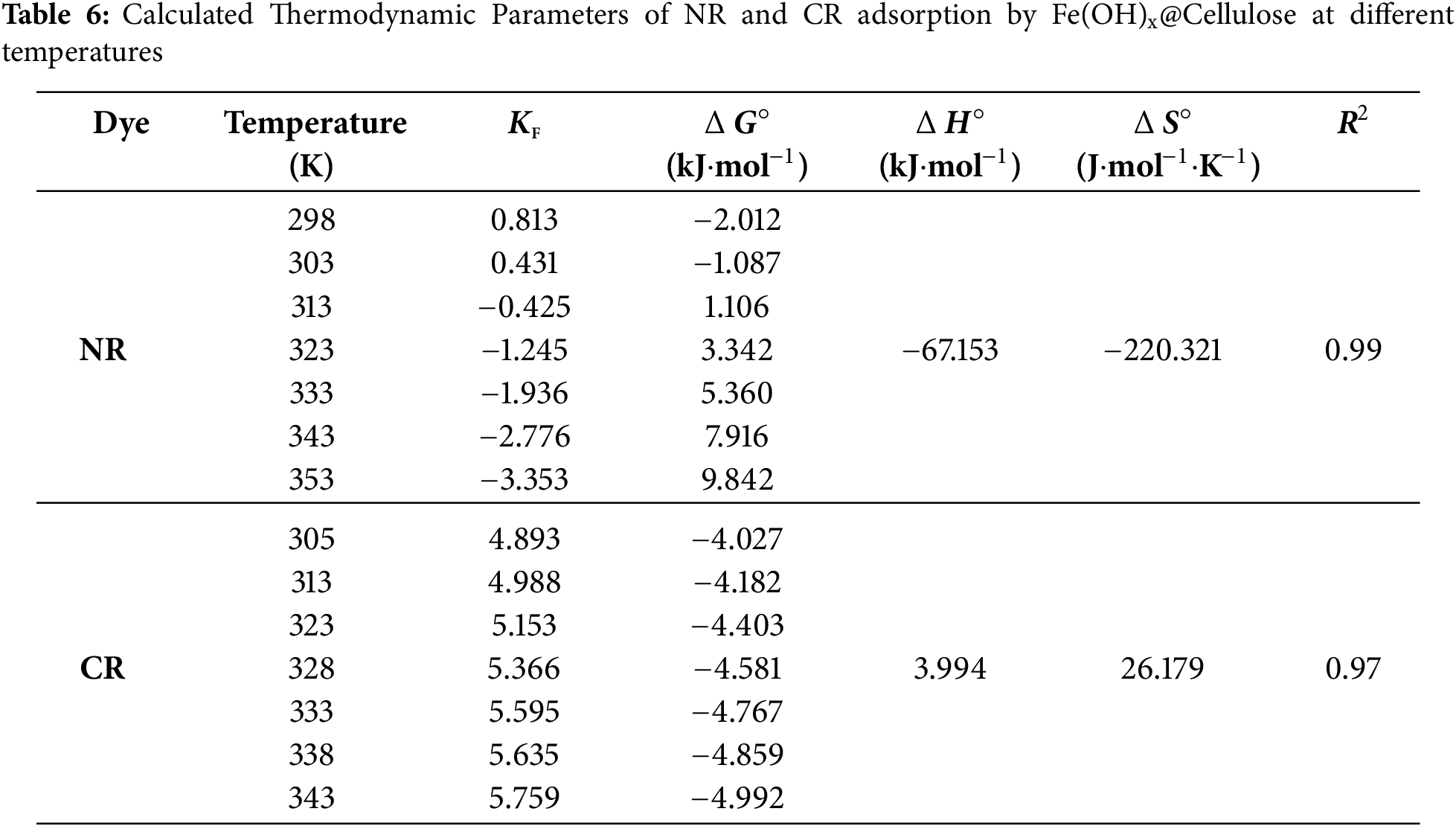

Temperature is a critical factor affecting the adsorption process, as it directly influences the rate of molecule adsorption. The adsorption of NR and CR dyes by treated Fe(OH)x@Cellulose biomass was studied over wide temperature range from 25°C to 80°C (298 to 353 K). While NR removal rates exceeded 74% at 298 K, CR dye removal rates increased from 41% to 54% as the temperature increased from 305 to 348 K. These contrasting trends suggest distinct adsorption mechanisms for the two dyes (Fig. 11). Notably, NR removal efficiency decreased with rising temperatures, indicating an exothermic adsorption process. Conversely, the increase in CR removal rate with temperature points to an endothermic adsorption mechanism [32,60].

Figure 11: Effect of temperature on removal rate of dyes ((a): NR; (b): CR) by the Fe(OH)x@Cellulose

The impact of temperature on dye adsorption by Fe(OH)x@Cellulose was investigated through thermodynamic analysis. The thermodynamic parameters ΔH°, ΔS° and ΔG° were calculated and grouped in Table 6. For CR, the ΔG° values were negative across the entire temperature range, indicating a spontaneous adsorption process. In contrast, for NR, the ΔG° was negative up 303 K, and became positive above this temperature, suggesting that adsorption becomes less favorable as temperature increases. A linear relationship between ln KF and 1/T (Fig. 12) allowed for the determination of ΔH° and ΔS°. The calculated adsorption enthalpies for NR and CR were −67.153 and 3994 kJ·mol−1, respectively. These results suggest that the adsorption of NR is exothermic, whereas that of CR is endothermic. The adsorption behavior of NR and CR on Fe(OH)x@Cellulose higlights the complex interplay of intermolecular forces and thermodynamic parameters. NR’s strong affinity to Fe(OH)x@Cellulose, as evidenced by its negative adsorption enthalpy, is attributed to favorable hydrogen bonding between their respective functional groups, specifically the hydroxyl groups (-OH) of cellulose and the amine (-NH2) and azo (-N=N-) groups of NR. However, the adsorption process is somewhat hindered by a decrease in system disorder, as indicated by the negative entropy value (−220.32 J·mol−1·K−1). Conversely, CR’s adsorption, although endothermic due to factors like electrostatic repulsion between the sulfonate groups (-

Figure 12: The Van’t Hoff plots for the adsorption of: (a) NR and (b) CR onto Fe(OH)x@Cellulose

Raw and treated biomass of the Opuntia ficus indica cladodes were characterized using FTIR, SEM, and XRD spectroscopy. The Fe(OH)x@Cellulose produced after treating OFIC proved to be an effective biosorbent for the dyes studied in this work, making it a promising candidate for wastewater treatment. Thermal decomposition, as indicated by TGA analysis, confirmed the material’s thermal stability.

Our findings indicate that the adsorption of both dyes onto the Fe(OH)x@Cellulose surface is best described by the Langmuir adsorption isotherm, suggesting monolayer coverage. This implies that the adsorption process is primarily driven by the formation of a single layer of dye molecules on the available active sites of the Fe(OH)x@Cellulose. Furthermore, the adsorption process is well-described by the pseudo-second-order kinetic model. Thermodynamic analysis reveals that the adsorption of both dyes is spontaneous under standard conditions, as demonstrated by the negative Gibbs free energy values. However, the thermodynamic parameters offer valuable insights into the nature of the adsorption mechanisms for each dye. For NR adsorption, the negative enthalpy and entropy values suggest an exothermic process driven by a decrease in system disorder at the adsorbent surface. This implies that the NR adsorption is favored at lower temperatures and involves a reduction in the degree of freedom within the system. Conversely, for CR adsorption, the positive entropy value suggests an increase in randomness during the adsorption process, which is characteristic of an endothermic process. This indicates that the adsorption of CR is favored at higher temperatures and involves an increase in the degree of freedom of the system.

Detailed characterization and mechanistic insights provided by this study, coupled with the demonstrated effectiveness of Fe(OH)x@Cellulose as a biosorbent for NR and CR dyes, establish a strong foundation for future research and development. This work highlights the potential for practical application in industrial wastewater treatment, prompting further exploration into optimization and implementation. Specifically, future investigations should focus on scaling up the synthesis process to ensure consistent material properties, fine-tuning synthesis parameters to enhance adsorption capacity and stability, evaluating the reusability and regeneration potential of the adsorbent, assessing performance in complex, real-world industrial wastewater matrices, developing strategies for integrating the biosorbent into existing or novel treatment systems; and examining the long-term stability and environmental impacts of spent adsorbents. Crucially, further studies should also investigate the performance of the material under varying pH conditions. This is essential for understanding its behavior in diverse industrial effluents and for optimizing its application in real-world scenarios. Exploring the pH-dependent adsorption behavior will provide valuable insights into the material’s selectivity and efficiency for different dye contaminants, leading to the development of customized depollution techniques. By pursuing these research avenues, we can translate the promising findings of this study into tangible advancements in sustainable wastewater treatment.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to Dr. Hanen Salhi for his valuable contributions and dedicated work throughout this project. They also extend their sincere thanks to their colleague, Prof. Nejib Mekni, a faculty member of ISTMT at El Manar University, for his expert review of the English language in the manuscript and their sincere gratitude to Rammeeza BiBi Roheeman for her invaluable contribution in reviewing the article’s English. The Ministry of Higher Education and Scientic Research of Tunisia is gratefully acknowledged.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The synthesis, structural characterisation by powder XRD, FTIR, MEB and adsorption measurements by UV spectroscopy: Mehrzia Krimi, Alma Jandoubi, Nabil Nasri and Rached Ben Hassen. Draft manuscript preparation: Mehrzia Krimi and Rached Ben Hassen. Thermogravimetric study and drafting of this section: Sami Bouf. Writing–review and editing: Mehrzia Krimi and Rached Ben Hassen. Supervision: Rached Ben Hassen and Sami Boufi. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Mehrzia Krimi, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| OFIC | Opuntia ficus indica cladodes |

| Fe(OH)x@Cellulose | FeCl3-treated Opuntia ficus indica cladodes |

| OFIC-NaOH | NaOH-treated Opuntia ficus indica cladodes |

| NR | Neutral Redk |

| CR | Congo Red |

References

1. Negash A, Tibebe D, Mulugeta M, Kassa Y. A study of basic and reactive dyes removal from synthetic and industrial wastewater by electrocoagulation process. S Afr J Chem Eng. 2023;46(7):122–31. doi:10.1016/j.sajce.2023.07.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Anuse DD, Patil SA, Chorumale AA, Kolekar AG, Bote PP, Walekar LS, et al. Activated carbon from pencil peel waste for effective removal of cationic crystal violet dye from aqueous solutions. Results Chem. 2025;13(4):101949. doi:10.1016/j.rechem.2024.101949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Rosli MA, Daud Z, A Latiff AA, A Rahman SE, Oyekanmi AA, Zainorabidin A, et al. The effectiveness of peat-ac composite adsorbent in removing color and fe from landfill leachate. Int J Integr Eng. 2017;9(3):35–8. [Google Scholar]

4. Saranya A, Sasikala S, Muthuraman G. Removal of manganese from ground/drinking water at south madras using natural adsorbents. Int J Recent Sci Res. 2017;8(6):17867–76. [Google Scholar]

5. Emmanuel KA, Veerabhadra Rao A. Adsorption of Mn(II) from aqueous solutions using Pithacelobium dulce carbon. Rasayan J Chem. 2008;1(4):840–52. [Google Scholar]

6. Mushahary N, Sarkar A, Das B, Rokhum SL, Basumatary S. A facile and green synthesis of corn cob-based graphene oxide and its modification with corn cob-K2CO3 for efficient removal of methylene blue dye: adsorption mechanism, isotherm, and kinetic studies. J Indian Chem Soc. 2024;101(11):101409. doi:10.1016/j.jics.2024.101409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Nharingo T, Moyo M. Application of Opuntia ficus-indica in bioremediation of wastewaters. J Environ Manag. 2016;166:55–72. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2015.10.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Bailey SE, Olin TJ, Bricka RM, Adrian DD. A review of potentially low-cost sorbents for heavy metals. Water Res. 1999;33(11):2469–79. doi:10.1016/S0043-1354(98)00475-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Khalfaoui A, Laggoun Z, Derbal K, Benalia A, Ghomrani AF, Pizzi A. Experimental study of selective batch bio-adsorption for the removal of dyes in industrial textile effluents. J Renew Mater. 2025;13(1):127–46. doi:10.32604/jrm.2024.056970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Zhang W, Duo H, Li S, An Y, Chen Z, Liu Z, et al. An overview of the recent advances in functionalization biomass adsorbents for toxic metals removal. Colloids Interface Sci Commun. 2020;38(3):100308. doi:10.1016/j.colcom.2020.100308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Ahmad MA, Eusoff MA, Oladoye PO, Adegoke KA, Bello OS. Optimization and batch studies on adsorption of Methylene blue dye using pomegranate fruit peel-based adsorbent. Chem Data Collect. 2021;32(18):100676. doi:10.1016/j.cdc.2021.100676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Saheed IO, Zairuddin NI, Nizar SA, Hanafiah MAKM, Latip AFA, Suah FBM. Adsorption potential of CuO-embedded chitosan bead for the removal of acid blue 25 dye. Ain Shams Eng J. 2024;15(12):103125. doi:10.1016/j.asej.2024.103125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Suteua D, Coserib S, Zahariaa C, Biliutab G, Nebunua I. Modified cellulose fibers as adsorbent for dye removal from aqueous environment. Desalin Water Treat. 2017;90:341–9. doi:10.5004/dwt.2017.21491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Wang S, Liu M, Bi W, Jin C, Chen DDY. Facile green treatment of mixed cellulose ester membranes by deep eutectic solvent to enhance dye removal and determination. Int J Biol Macromol. 2025;291:139100. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.139100. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Goel NK, Kumar V, Misra N, Varshney L. Cellulose based cationic adsorbent fabricated via radiation grafting process for treatment of dyes waste water. Carbohydr Polym. 2015;132(3):444–51. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.06.054. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Negrea A, Gabor A, Davidescu CM, Ciopec M, Negrea P, Duteanu N, et al. Rare earth elements removel from water using natural polymers. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):1–11. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-18623-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Oyewo OA, Elemike EE, Onwudiwe DC, Onyango MS. Metal oxide-cellulose nanocomposites for the removal of toxic metals and dyes from wastewater. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;164:2477–96. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Ayadi MA, Abdelmaksoud W, Ennouri M, Attia H. Cladodes from Opuntia ficus indica as a source of dietary fiber: effect on dough characteristics and cake making. Ind Crop Prod. 2009;30(1):40–7. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2009.01.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Lassoued Ben Miled G, Djobbi B, Ben Hassen R. Influence of operating factors on turbidity removal of water surface by natural coagulant indigenous to Tunisia using experimental design. J Water Chem Techno. 2018;40(5):285–90. doi:10.3103/S1063455X18050065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Volpe M, Adair JL, Gao L, Fiori L, Goldfarb JL. Sustainable treatment of naturally occurring heavy metals in sicilian water via hydrothermal carbonization, secondary biofuel extraction, and activation of Opuntia ficus indica. Chem Eng J. 2025;505(2):159030. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2024.159030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Choy SY, Prasad KMN, Wu TY, Raghunandan ME, Ramanan RN. Utilization of plant-based natural coagulants as future alternatives towards sustainable water clarification. J Environ Sci. 2014;26(11):2178–89. doi:10.1016/j.jes.2014.09.024. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Ifguis O, Ziat Y, Belkhanchi H, Ammou F, Moutcine A, Laghlimi C. Adsorption mechanism of methylene blue from polluted water by Opuntia ficus indica of Beni Mellal and Sidi Bou Othmane areas: a comparative study. Chem Phys Impact. 2023;6(1):100235. doi:10.1016/j.chphi.2023.100235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Benhamou A, Boussetta A, Grimi N, Idrissi ME, Nadifiyine M, Barba FJ, et al. Characteristics of cellulose fibers from Opuntia ficus indica cladodes and its use as reinforcement for PET based composites. J Nat Fibers. 2022;19(13):6148–64. doi:10.1080/15440478.2021.1904484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Contreras-Padilla M, Pérez-Torrero E, Hernández-Urbiola MI, Hernández-Quevedo G, del Real A, Rivera-Muñoz EM, et al. Evaluation of oxalates and calcium in nopal pads (Ountia ficus-indica var. redonda) at different maturity stages. J Food Compos Anal. 2011;24(1):38–43. doi:10.1016/j.jfca.2010.03.028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Djobbi B, Lassoued Ben Miled G, Raddadi H, Ben Hassen R. Efficient removal of Aqueous Manganese (II) cations by activated Opuntia ficus indica powder: adsorption performance and mechanism. Acta Chem Slov. 2021;68(3):548–61. doi:10.17344/acsi.2020.6248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Louati I, Fersi M, Hadrich B, Ghariani B, Nasri M, Mechichi T. Prickly pear cactus cladodes powder of Opuntia ficus indica as a cost effective biosorbent for dyes removal from aqueous solutions. Biotech. 2018;8(3):478. doi:10.1007/s13205-018-1499-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Degbe AK, Koriko M, Tchegueni S, Aziable E, Tchakala I, Hafidi M, et al. Biosorption of methylene blue solution: comparative study of the cactus (Opuntia ficus indica) of Lomé (CL) and Marrakech (CM). J Mater Environ Sci. 2016;7(12):4786–94. [Google Scholar]

28. Pandit VRU, Jadhav GKP, Jawale VMS, Dubepatil R, Guraoa R, Late DJ. Synthesis and characterization of micro-/nano-aFe2O3 for photocatalytic dye degradation. RSC Adv. 2024;14(40):29099–105. doi:10.1039/d4ra04575k. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Zhao J, Lu Z, He X, Zhang X, Li Q, Xia T, et al. One-step fabrication of Fe(OH)3@Cellulose hollow nanofibers with superior capability for water purification. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2017;9(30):25339–49. doi:10.1021/acsami.7b07038. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Yagub MT, Sen TK, Afroze S, Ang HM. Dye and its removal from aqueous solution by adsorption. Adv Colloid Interface Sci. 2014;209(1):172–84. doi:10.1016/j.cis.2014.04.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Ohale PE, Onu CE, Ohale NJ, Oba SN. Adsorptive kinetics, isotherm and thermodynamic analysis of fishpond effluent coagulation using chitin derived coagulant from waste Brachyura shell. Chem Eng J Adv. 2020;4:100036. doi:10.1016/j.ceja.2020.100036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Islam MR, Mostafa MG. Adsorption kinetics, isotherms and thermodynamic studies of methyl blue in textile dye effluent on natural clay adsorbent. Sustain Water Resour Manag. 2022;8(2):52. doi:10.1007/s40899-022-00640-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Xin Q, Fu J, Chen Z, Liu S, Yan Y, Zhang J, et al. Polypyrrole nanofibers as a high-efficient adsorbent for the removal of methyl orange from aqueous solution. J Environ Chem Eng. 2015;3(3):1637–47. doi:10.1016/j.jece.2015.06.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Liu W, Du H, Liu H, Xie H, Xu T, Zhao X, et al. Highly efficient and sustainable preparation of carboxylic and thermostable cellulose nanocrystals via FeCl3-catalyzed innocuous citric acid hydrolysis. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2020;8(44):16691–700. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.0c06561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Judith RBD, Pámanes-Carrasco GA, Delgado E, Rodríguez-Rosales MDJ, Medrano-Roldán H, Reyes-Jáquez D. Extraction optimization and molecular dynamic simulation of cellulose nanocrystals obtained from bean forage. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol. 2022;43(2):102443. doi:10.1016/j.bcab.2022.102443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Yang X, Xie H, Du H, Zhang X, Zou Z, Zou Y, et al. Facile extraction of thermally stable and dispersible cellulose nanocrystals with high yield via a green and recyclable FeCl3-catalyzed deep eutectic solvent system. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2019;7(7):7200–8. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.9b00209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Chen Y, Yu HY, Li Y. Highly efficient and superfast cellulose dissolution by green chloride salts and its dissolution mechanism. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2020;8(50):18446–54. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.0c05788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Cheng M, Qin Z, Chen Y, Hu S, Ren Z, Zhu M. Efficient extraction of cellulose nanocrystals through hydrochloric acid hydrolysis catalyzed by inorganic chlorides underhydrothermal conditions. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2017;5(6):4656–64. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.6b03194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Tinh NT, Phuong NT, Nghiem DG, Dan DK, Khang PT, Dat NM, et al. Green synthesis of sulfonated graphene oxide-like catalyst from corncob for conversion of hemicellulose into furfural. Biomass Conv Bioref. 2024;14(10):11011–22. doi:10.1007/s13399-022-03136-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Kacuráková M, Capek P, Sasinkova V, Wellner N, Ebringerova A. FT-IR study of plant cell wall model compounds: pectic polysaccharides and hemicelluloses. Carbohydr Polym. 2000;43(2):195–203. doi:10.1016/S0144-8617(00)00151-X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Latham KG, Matsakas L, Figueira J, Rova U, Christakopoulos P, Jansson S. Examination of how variations in lignin properties from Kraft and Organosolv extraction influence the physicochemical characteristics of hydrothermal carbon. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis. 2021;155(9):105095. doi:10.1016/j.jaap.2021.105095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Medina OJ, Patarroyo W, Moreno LM. Current trends in cacti drying processes and their effects on cellulose and mucilage from two Colombian cactus species. Heliyon. 2022;8(12):e12618. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e12618. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Ivanova I, Spiridonov I, Lasheva V. Spectroscopic techique for studying the caracteristics of paper, pigments and inks in the aging process. J Chem Technol Metall. 2022;57(1):101–13. [Google Scholar]

44. Perring L, Andrey D, Basic-Dvorzak M, Hammer D. Rapid quantification of iron, copper and zinc in food premixes using energy dispersive X-ray fluorescence. J Food Compos Anal. 2005;18(7):655–63. doi:10.1016/j.jfca.2004.06.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Mannai F, Ammar M, Yanez JG, Elaloui E, Moussaoui Y. Cellulose fiber from Tunisian barbary fig “Opuntia ficus-indica” for papermaking. Cellulose. 2016;23(3):2061–72. doi:10.1007/s10570-016-0899-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Tejada-Tovar C, Bonilla-Mancilla H, Villabona-Ortíz A, Ortega-Toro R, Licares-Eguavil J. Effect of the adsorbent dose and initial contaminant concentration on the removal of Pb(II) in a solution using Opuntia ficus indica shell. Rev Mex Ing Quím. 2020;20(2):555–68. doi:10.24275/rmiq/IA2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Khomri ME, Messaoudi NE, Dbik A, Bentahar S, Lacherai A. Efficient adsorbent derived from Argania spinosa for the adsorption of cationic dye: kinetics, mechanism, isotherm and thermodynamic study. Surf Interfaces. 2020;20:100601. doi:10.1016/J.SURFIN.2020.100601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Mousa HM, Hussein KH, Sayed MM, Abd El-Rahman MK, Woo HM. Development and characterization of cellulose/iron acetate nanofibers for bone tissue engineering applications. Polymers. 2021;13(8):1339. doi:10.3390/POLYM13081339. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Dacrorya S, Moussa M, Turky G, Kamel S. In situ synthesis of Fe3O4@ cyanoethyl cellulose composite as antimicrobial and semiconducting film. Carbohydr Polym. 2020;236(2):116032. doi:10.1016/J.CARBPOL.2020.116032. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. De Assis ACL, Alves LP, Malheiro JPT, Barros ARA, Pinheiro-Santos EE, De Azevedo EP, et al. Opuntia ficus-indica L. Miller (Palma Forrageira) as an alternative source of cellulose for production of pharmaceutical dosage forms and biomaterials: extraction and characterization. Polymers. 2019;11(7):1124. doi:10.3390/POLYM11071124. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Horseman T, Tajvidi M, Diop CIK, Gardner DJ. Preparation and property assessment of neat lignocellulose nanofibrils (LCNF) and their composite films. Cellulose. 2017;24(6):2455–68. doi:10.1007/S10570-017-1266-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Pasangulapati V, Ramachandriya KD, Kumar A, Wilkins MR, Jones CL, Huhnke RL. Effects of cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin on thermochemical conversion characteristics of the selected biomass. Bioresour Technol. 2012;114(13):663–9. doi:10.1016/J.BIORTECH.2012.03.036. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Emiola-Sadiq T, Zhang L, Dalai AK. Thermal and kinetic studies on biomass degradation via thermogravimetric analysis: a combination of model-fitting and model-free approach. ACS Omega. 2021;6(34):22233–47. doi:10.1021/acsomega.1c02937. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Zhu HY, Fu YQ, Jiang R, Jiang JH, Xiao L, Zeng GM, et al. Adsorption removal of Congo red onto magnetic cellulose/Fe3O4/activated carbon composite: equilibrium, kinetic and thermodynamic studies. Chem Eng J. 2011;173(2):494–502. doi:10.1016/J.CEJ.2011.08.020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Adeleke AO, Omar RC, Katibi KK, Dele-Afolabi TT, Ahmad A, Quazim JO, et al. Process optimization of superior biosorption capacity of biogenic oyster shells nanoparticles for Congo red and Bromothymol blue dyes removal from aqueous solution: response surface methodology, equilibrium isotherm, kinetic, and reusability studies. Alex Eng J. 2024;92(6):11–23. doi:10.1016/j.aej.2024.02.042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Luo P, Zhao Y, Zhang B, Liu J, Yang Y, Liu J. Study on the adsorption of Neutral Red from aqueous solution onto halloysite nanotubes. Water Res. 2010;44(5):1489–97. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2009.10.042. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. De Freitas FP, Carvalho AMML, Carneiro ADCO, De Magalhães MA, Xisto MF, Canal WD. Adsorption of neutral red dye by chitosan and activated carbon composite films. Heliyon. 2021;7(7):e07629. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07629. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Batool A, Valiyaveettil S. Chemical transformation of soya waste into stable adsorbent for enhanced removal of methylene blue and neutral red from water. J Environ Chem Eng. 2021;9(1):104902. doi:10.1016/j.jece.2020.104902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Mohana SV, Raoa NC, Karthikeyanb J. Adsorptive removal of direct azo dye from aqueous phase onto coal based sorbents: a kinetic and mechanistic study. J Hazard Mater. 2002;90(2):189–204. doi:10.1016/S0304-3894(01)00348-X. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Wang J, Tan Y, Yang H, Zhan L, Sun G, Luo L. On the adsorption characteristics and mechanism of methylene blue by ball mill modifed biochar. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):21174. doi:10.1038/S41598-023-48373-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Belaid KD, Kacha S. Étude cinétique et thermodynamique de l’adsorption d’un colorant basique sur la sciure de bois. Rev Sci Eau. 2011;24(2):131–44. (In French). doi:10.7202/1006107AR. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Vij RK, Janani VA, Subramanian D, Mistry CR, Devaraj G, Pandian S. Equilibrium, kinetic and thermodynamic studies for the removal of Reactive Red dye 120 using Hydrilla verticillata biomass: a batch and column study. Environ Technol Inno. 2021;24:102009. doi:10.1016/j.eti.2021.102009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools