Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Production of Activated Biochar from Palm Kernel Shell for Methylene Blue Removal

Department of Chemical Engineering and Sustainability, Kulliyyah of Engineering, International Islamic University Malaysia (IIUM), Jalan Gombak, Kuala Lumpur, 53100, Malaysia

* Corresponding Author: Sarina Sulaiman. Email:

Journal of Renewable Materials 2026, 14(1), 6 https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2025.02025-0105

Received 16 June 2025; Accepted 17 October 2025; Issue published 23 January 2026

Abstract

In this study, Palm kernel shell (PKS) is utilized as a raw material to produce activated biochar as adsorbent for dye removal from wastewater, specifically methylene blue (MB) dye, by utilizing a simplified and cost-effective approach. Production of activated biochar was carried out using both a furnace and a domestic microwave oven without an inert atmosphere. Three samples of palm kernel shell (PKS) based activated biochar labeled as samples A, B and C were carbonized inside the furnace at 800°C for 1 h and then activated using the microwave-heating technique with varying heating times (0, 5, 10, and 15 min). The heating was conducted in the absence of an inert gas. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) highlighted a significant Si-O stretching vibration between 1040.5 to 692.7 cm−1, indicating the presence of key components (Silica and Alumina) in all PKS-based activated biochar samples. For wastewater treatment, activated biochar samples were tested against a 20 mg/L Methylene Blue (MB) solution, and the MB percentage removal was calculated for each run using a standard curve. Central Composite Design (CCD) experiments were conducted for optimization, with activated biochar Sample C exhibiting the highest adsorption capacity at 88.14% MB removal under specific conditions. ANOVA analysis confirmed the significance of the quadratic model, with a p-value of 0.0222 and R2 = 0.9438. In conclusion, the results demonstrated the efficiency of PKS-based activated biochar as an adsorbent for MB removal in comparison to other commercial adsorbents.Keywords

Palm kernel shell (PKS) is a residual material derived from the process of extracting oil from the fruit of the oil palm tree, which is a common practice in the palm oil industry [1,2]. It is a hard, fibrous material that is brown and has a high calorific value, which also makes it an attractive fuel source. On average, it is estimated that around 4.7 million tons of palm kernel shells (PKS) are produced annually in Malaysia [1]. These numbers are likely to increase in the future, as the palm oil industry continues to grow and expand in hectares and demand. The large amounts of PKS generated in the industry have led to efforts to find new and innovative ways to use and recycle this waste material. Some of the common uses of PKS include biomass fuel for electricity generation, as a soil amendment for agriculture, and as a raw material to produce organic activated biochar, zeolite, activated carbon, and other value-added products. The high Silica (Si) content of PKS ash makes it extremely fragile, while the material strength is strongly reliant on the high concentration of iron (Fe) and aluminium (Al) [3]. It was also proven that oil palm ash content has enough Si and Al percentage, making them eligible to be a feedstock in producing zeolites as they have the two prerequisite components to make a good adsorbent [4].

The textile industry often uses excessive amounts of synthetic dye such as Methylene Blue (MB), Crystal Violet, Congo Red, Reactive Red and Acid Orange [5–9]. The adsorption process has been widely applied for dye removal, achieving removal efficiencies ranging from 64% to 94%, depending on the type of adsorbent utilized. Madan et al. (2019) reported that a ZnO composite used as an adsorbent achieved a high dye removal efficiency of 90% for Congo Red at concentrations ranging from 25 to 500 mg/L. Similarly, Hamzeh et al. (2012) demonstrated a 90% removal efficiency for Acid Orange 7 and Remazol Black 5 dyes using canola stalks as adsorbents, with a contact time of approximately 20 min and an adsorbent dosage of 15 g/L [10]. The adsorbent particle size ranged from 0.42 to 0.60 mm, providing a relatively large surface area that enhances the adsorption process. PKS-based activated biochar exhibited a notably high adsorption capacity compared to other adsorbents, achieving an impressive 86.4% dye removal efficiency for a 1000 mg/L Crystal Violet (CV) solution, despite using a comparable adsorbent dosage to that reported in other studies [9]. Methylene blue (3,7-bis(dimethylamine) phenothiazine chloride tetra methylthionine chloride) is a synthetic dye that is widely used as a colorant in the paper, wool, silk, and textile industries [11]. Compared to other industries, the textile industry is the largest contributor of dye effluent discharge into the environment [12]. Despite claims to the contrary, wastewater containing methylene blue dye that is only partially or improperly treated can pose serious health risks to humans, animals, and even plants, as methylene blue is cationic in nature and can interact negatively with biological systems [13]. Furthermore, because methylene blue is difficult to degrade, its complete removal from effluents requires specific and often complex treatment methods. Numerous techniques have been explored for dye removal from wastewater; however, the adsorption process remains the most widely favored due to its cost-effectiveness and high efficiency [14]. However, synthetic adsorbents used in the adsorption process are often expensive for large scale applications. Consequently, numerous studies have focused on developing alternative, low cost organic adsorbents, such as activated biochar, to provide a more sustainable and economical solution.

Usually, activated biochar works as an adsorbent to sequester pollutants through mechanisms like physical adsorption, chemical bonding, and ion exchange [15,16]. Its porous nature provides ample surface sites for adsorption, while the presence of functional groups enhances interactions with target compounds [15]. The exploration of activated biochar as an adsorbent offers great potential for developing sustainable solutions to challenges in wastewater treatment, soil remediation, and pollution control. Microwave-assisted synthesis of activated biochar presents an innovative and efficient approach, providing benefits such as rapid heating, reduced energy consumption, and precise control over reaction conditions. This method enables the production of activated biochar with tailored physicochemical properties, including optimized surface area and pore size distribution [17]. It has also been proven to offer a significantly shorter synthesis time compared to conventional activation methods [18,19]. This method is particularly advantageous for optimizing the characteristics of activated biochar, thereby enhancing its adsorption capacity for targeted contaminants. The incorporation of microwave technology in activated biochar synthesis aligns with the increasing emphasis on sustainable, energy efficient, and environmentally friendly approaches in science and engineering.

Although palm kernel shell (PKS), microwave assisted activation, and dye removal have been widely reported, most studies employ either laboratory scale furnaces with controlled atmospheres or specialized microwave reactors, which limit scalability and accessibility. In this study, a simplified and cost-effective approach is demonstrated by utilizing both a furnace and a domestic microwave oven without an inert atmosphere for biochar activation. Biochar was synthesized from PKS and then was activated using microwave heating, followed by analyzing the characteristics of the final product to fit its usage for wastewater treatment. Microwave heating was carried out under normal atmospheric conditions, without the use of an inert gas to control the environment. The success of this study will give a major benefit to industry as we look to promote sustainable practices in the palm oil industry and to develop alternative sources of bioenergy that are less harmful to the environment, which is one of the ultimate goals of this study.

The palm kernel shell (PKS) was obtained from a supplier, Woodlife Sdn Bhd., Kuala Lumpur and was stored at room temperature before the start of the experiment. In the initial phase of the experiment, the palm kernel shell underwent a cleaning procedure, during which it was thoroughly rinsed with distilled water to eliminate any surface contaminants. Subsequently, it underwent a drying process in a laboratory oven at 60°C for 24 h to remove moisture content. Following the drying process, the palm kernel shell was grounded using a household standard Panasonic blender and sieved to attain a fine brown powder form, ranging below 250 μm [20]. Upon completion, the PKS went through a leaching process to remove metallic oxide impurities using 500 mL of 0.1 M Hydrochloric Acid (HCl) from Sigma’s Aldrich for 1 h before being recovered and rinsed with distilled water [20]. Next, the PKS solution was filtered using Buchner funnel and the recovered PKS was rinsed with distilled water to remove the remaining acid content (Mamudu et al., 2021). The recovered PKS was then dried inside an oven at 60°C for 45 min before being carbonized inside the furnace at 800°C for 1 h [20].

2.2.1 Preparation of Adsorbate

Methylene Blue dye powder (C2181) Bendosan was obtained from Progressive Scientific Sdn. Bhd. For MB stock solution, 20 mg of MB was added into 1000 mL of distilled water and mixed on a hotplate stirrer for 60 min at room temperature to form a 20 mg/L MB stock solution. The prepared solution was then used to create a dilution series of 100%, 80%, 60%, 40%, and 20% MB concentration with distilled water to obtain a standard curve that serves as a guide for the MB removal percentage analysis [21].

2.2.2 Activated Biochar Synthesis

The PKS solution was formed by adding 2.2 g of treated PKS into 22 mL of distilled water [20]. Next, NaOH was added as a directing agent for the solution at a ratio of 1:0.3. The solution was then placed in a hotplate stirrer for 60 min at 70°C to achieve a homogenous solution [20]. After 1 h, the samples were cooled at room temperature before placed into a household-standard Samsung domestic microwave oven (800 W, 2.45 GHz) for the heating process at a varying heating time (5, 10 & 15 min) under low power, where Sample A was heated for 5 min, Sample B for 10 min, and Sample C for 15 min. The activation step was conducted using the microwave without inert gas in a closed container, and the activated biochar was recovered at the end of the experiment. The sample was thoroughly washed with distilled water until neutral [22].

2.2.3 Characterization of Activated Biochar

The following characterization methods were employed for the synthesized activated biochar:

Scanning Electron Microscopic (SEM)

The activated biochar samples’ morphological structure was examined through scanning electron microscopy (SEM), SEM JEOL JSM-IT100, Japan instrument. It was then followed by Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDX) analysis using software provided by the same equipment to study the elemental composition of the activated biochar.

Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR)

Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR), Thermo Scientific Nicolet iS50 was utilized to analyze the present functional groups in the synthesized activated biochar. This analysis is done through the service of INHART at IIUM Gombak Campus, Malaysia. The wavenumbers were set at a range of 650 to 4000

2.3 Wastewater Treatment Analysis

For wastewater treatment analysis, the prepared 20 mg/L MB stock solution was used as the primary wastewater sample throughout the experiment.

2.3.1 Preparation of Standard Curve

Using the 20 mg/L MB stock solution, a dilution series was developed by transferring 100 mL of the MB stock solution into a 250 mL conical flask and labeled as 100% concentration, followed by subsequent dilutions of 80%, 60%, 40%, and 20% by diluting the preceding solution with distilled water in specified proportions [21]. Once completed, each solution absorbance was measured using a UV-VIS Spectrophotometer (Shimadzu (Tokyo, Japan)) at a wavelength of 665 nm. The standard curve served as a key to the analysis to convert the measured absorbance values into meaningful concentration values [21].

2.3.2 Batch Adsorption Experiment

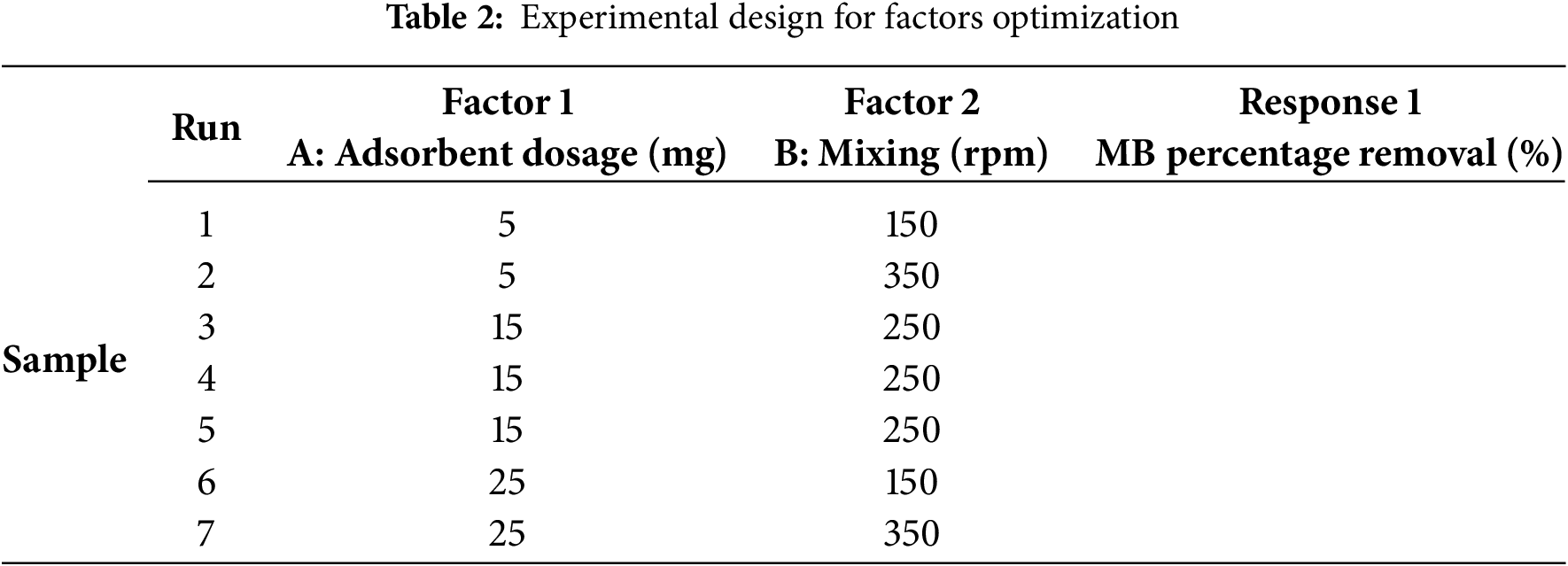

The adsorption was conducted in batch mode, wherein each sample (Samples A, B, C) underwent seven experimental runs provided by the Design Expert. Subsequently, a predetermined quantity of the adsorbent (5, 15, 25 mg) was introduced into each flask, and the mixture was subjected to agitation in an orbital shaker for one hour at a specified rotational speed (150, 250, 350 rpm) [19]. Following the one-hour adsorption period, the solutions were extracted from the orbital flask and promptly transferred to a spectrophotometer for the determination of their final concentrations. This process entailed the transfer of the solution into a cuvette, which was then placed within the spectrophotometer for absorbance measurement. The identified absorbance values were subsequently correlated with a standard curve to ascertain the final percentage concentration [19]. The determination of the removal percentage was then accomplished by using Eq. (1) below:

where;

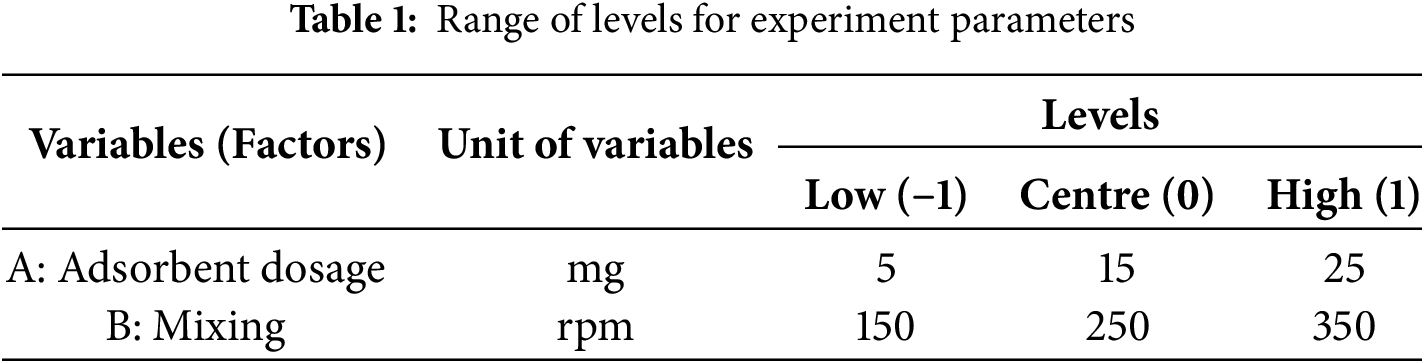

The optimization procedure aimed to maximize the percentage of MB removal, and it used a Response Surface-Central Composite experimental design created by Stat-Ease Inc.’s Design-Expert software version 13. Table 1 defines the specified factor levels and ranges, while Table 2 describes the conditions for the optimization experimental design. For a CCD with two factors and one response, the typical design includes a set of factorial points, axial points, and center point. The center points are replicated to improve the precision of the experimental estimates as per Eq. (2).

where:

3.1 Characterization of Activated Biochar

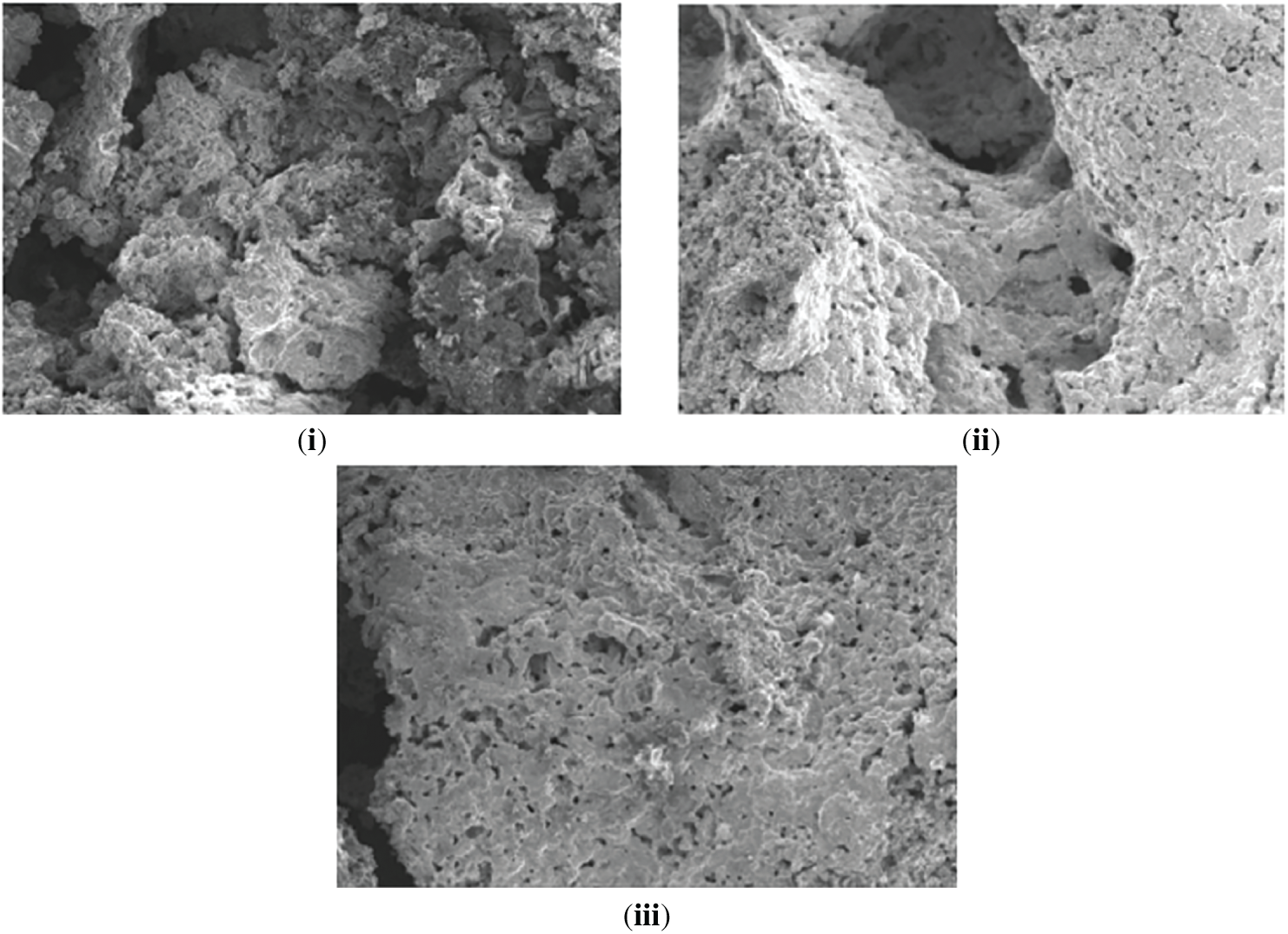

3.1.1 Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

The morphology of synthesized activated biochar samples (A, B, C) was studied using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM). Fig. 1 illustrates similar physical characteristics, such as tiny porous structures with cracks and fissures [23]. Activation and treatment with strong acid led to pronounced increases in micropore surface area, a positive attribute for activated biochar adsorption and ion exchange capabilities [4,24]. Notably, Sample A exhibited a rougher surface compared to Samples B, and C, aligning with research indicating that activated biochar with greater surface roughness and porosity tends to exhibit superior adsorption capabilities [13]. The rough surface texture with irregularities, pores, and crevices provides additional binding sites, enhancing the overall effectiveness of the activated biochar as an adsorbent [13].

Figure 1: SEM images of activated biochar samples under 100× magnification (i) Sample A (ii) Sample B (iii) Sample C

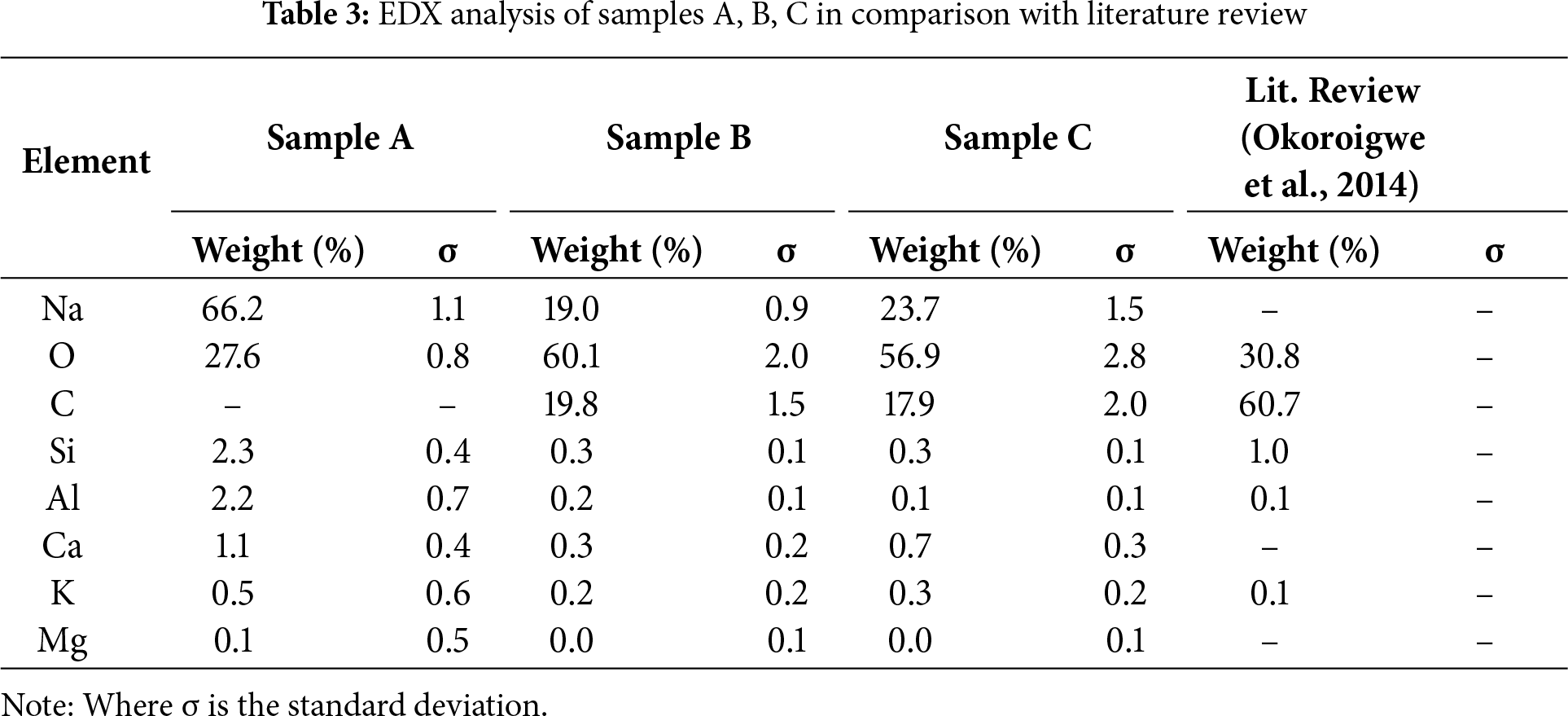

Analysis using SEM with Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDX) shows that all four samples exhibit a similar overall elemental makeup, predominantly composed of sodium (Na), oxygen (O), and carbon (C) as detailed in Table 3. This implies a shared inorganic matrix or substrate across all samples, consistent with the organic origin of palm kernel shells [25]. Notably, Sample A features the highest Na content (66.2%), contrasting with Sample C, which records the lowest (23.7%). The use of NaOH as a directing agent in the synthesis process contributed to the high Na content in the activated biochar samples, differing from literature-reported PKS-based activated biochar elemental compositions [26]. This could be an indication of the presence of Na entities incorporated onto the surface where Sample A showed no detectable carbon. This is likely due to the detection of light elements with EDXS remaining challenging, as the X-ray signals are more easily re-absorbed compared to heavier elements, and the fluorescence yield is inherently low [25,27]. Higher proportions of Si and Al in the PKS-based activated biochar suggest their potential to strengthen the activated biochar matrix when used as an absorbent [25]. Samples B and C show Carbon content of 19.8% and 17.9%, respectively. The unique pyrolysis conditions employed in this research can influence the chemical composition, and higher temperatures or longer residence times may result in more complete carbonization and lower oxygen content [26].

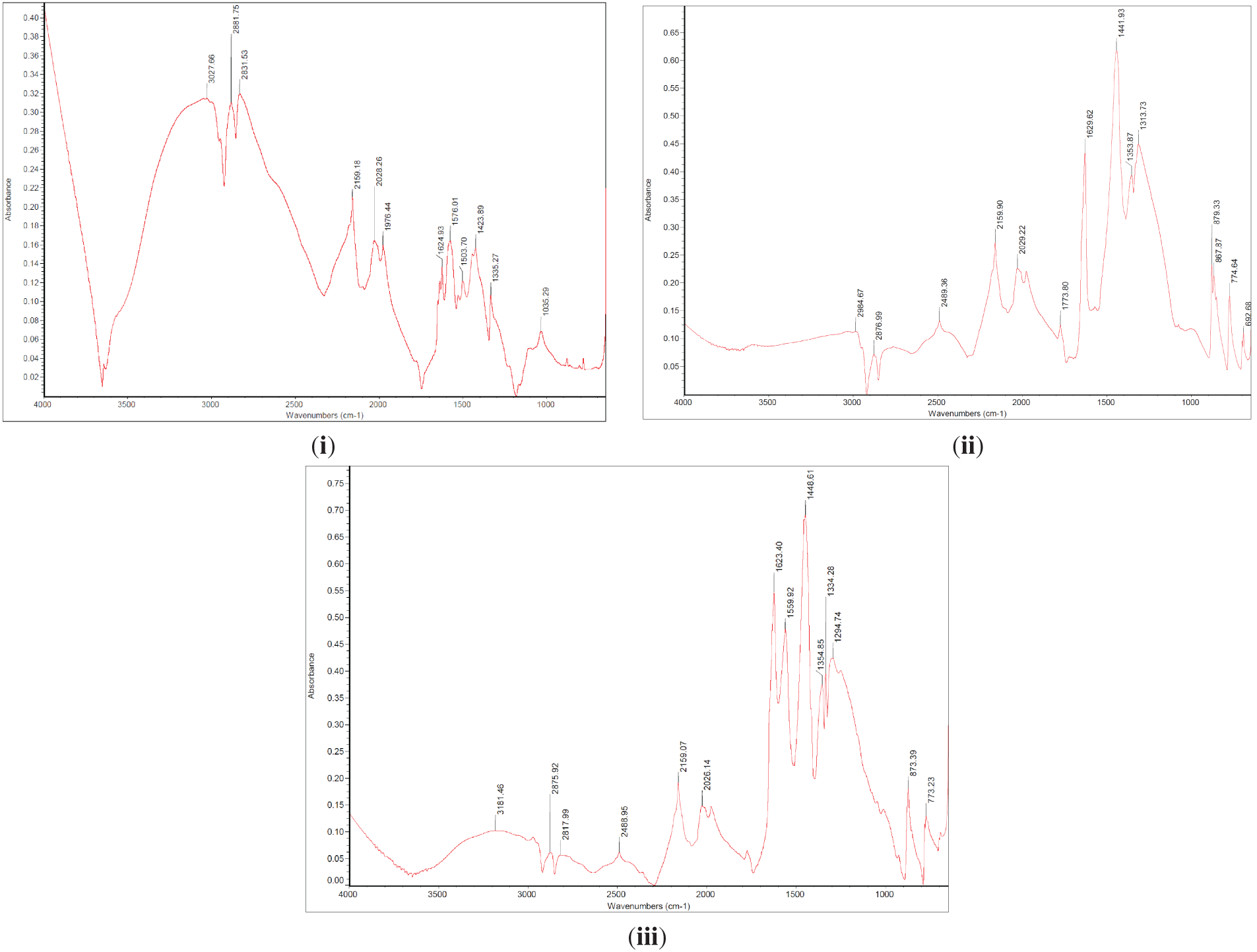

3.1.2 Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) Analysis

This study utilized Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) to analyze the composite, focusing on the Si and Al presence and identifying additional functional groups present in the synthesized activated biochar as shown in Fig. 2. Comparing our findings to the result from the literature review, a broad peak around 3400 cm−1 indicates the presence of O-H groups, suggesting significant hydroxyl functionality, possibly retained from the acid leaching process [21,28]. Notably, Samples A, B and C show a reduction in hydroxyl groups, potentially influenced by prolonged heating time [4]. Peaks at 2876.99 to 2881.75 cm−1 indicate aliphatic C-H stretching vibrations, suggesting the presence of alkanes and alkyl groups in all samples. The peak at 1629.62 to 1313.73 cm−1 aligns with C=C double bonds in aromatic rings, indicative of the presence of lignin or aromatic components in the activated biochar, consistent with PKS composition [21,29]. Furthermore, Si-O stretching vibrations were observed in all four samples within the range of 809 to 1040.5 cm−1, indicating the presence of Silica and Alumina from the PKS incorporated into the activated biochar structure [21]. Furthermore, the use of NaOH activation significantly increases the surface area and adds different functional groups, such as C-H stretching, which are crucial for boosting adsorption capacity. FTIR spectra indicate that hydrochloric acid leaching diminished the strength of mineral-related bands between 770–1000 cm−1 and enhanced the O-H absorption peaks around 3200 cm−1, suggesting effective removal of ash components and exposure or addition of oxygen-containing functional groups on the biochar’s surface especially for samples B and C. Overall, the FTIR spectra aligned well with the literature findings, and microwaves shorten processing time while promoting more uniform activation and improved pore accessibility.

Figure 2: FTIR spectra of the activated PKS biochar (i) Sample A (ii) Sample B (iii) Sample C

Design of Experiment

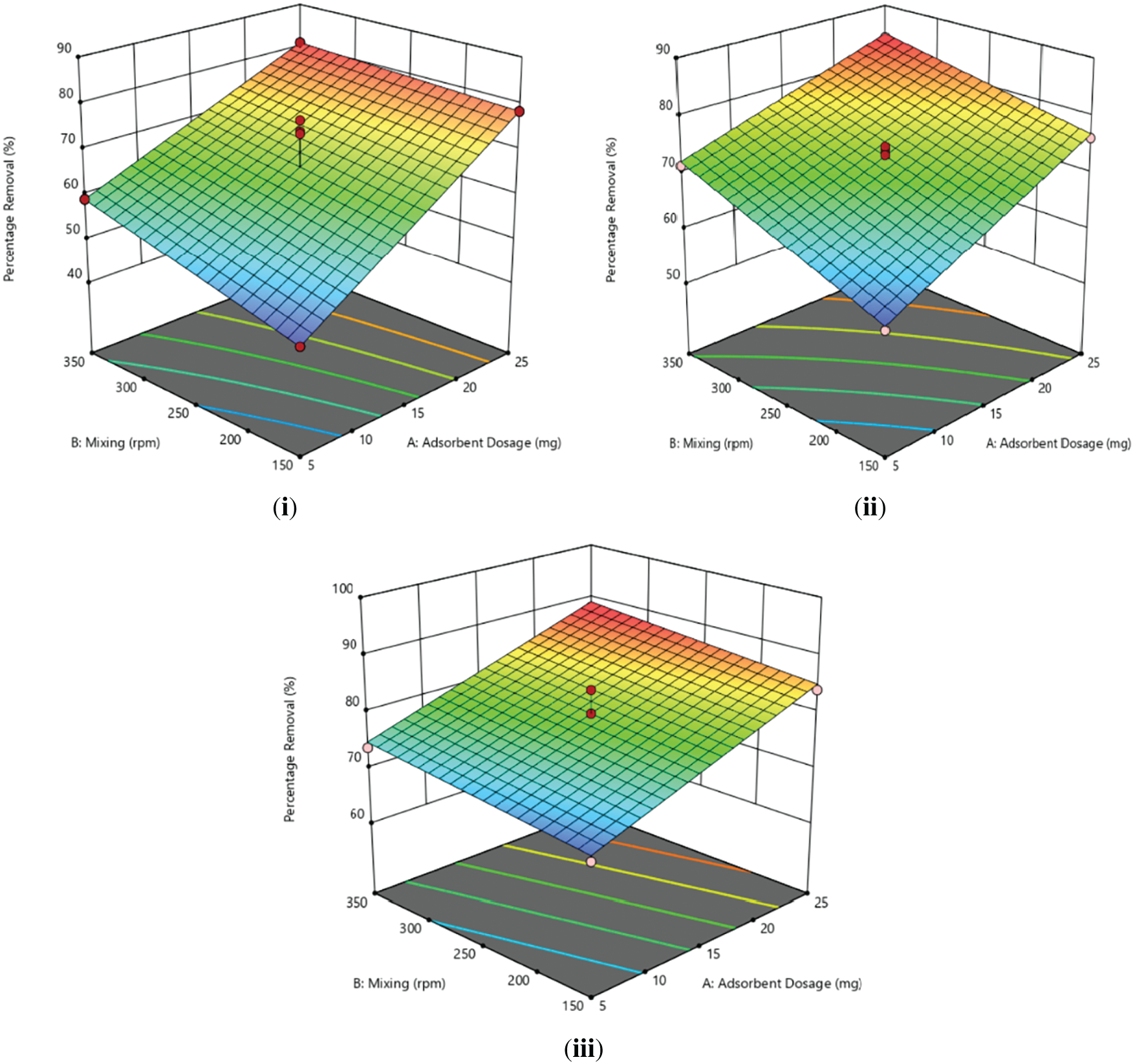

Sample A exhibited the highest MB removal percentage (80.94%) at 25 mg adsorbent dosage and 350 rpm, while the lowest percentage (46.48%) occurred at 5 mg adsorbent dosage and 150 rpm. Fig. 3i shows the significant influence of dosage and mixing speed on MB removal, with higher values contributing to increased removal percentages [30].

Figure 3: 3D surface of percentage removal against adsorbent dosage and mixing speed (i) Sample A (ii) Sample B (iii) Sample C

Fig. 3ii-Sample B exhibits a consistent increase in removal percentage is observed with higher adsorbent dosage and mixing speed, surpassing Sample A overall, with values ranging from 57.91% to 83.97%. The disparity in heating time during synthesis is a probable explanation since Sample B, synthesized for a longer duration, was likely to achieve higher carbonization, enhancing activated biochar adsorption capacity [4,31]. This aligns with the literature review that found extended heating times resulted in increased cadmium adsorption due to higher carbon content and lower ash content, enhancing biochar stability [16].

Sample C demonstrated the highest removal percentage among the four samples, reaching a peak removal of 88.14% at 25 mg dosage and 350 rpm mixing speed, affirming the positive correlation between these two factors. Even at the minimum dosage and mixing speed, Sample C exhibited a superior removal percentage compared to other samples under the same conditions, emphasizing the significant influence of activated biochar heating time on adsorption capacity and chemical content [16]. The 3D surface plots in Fig. 3iii illustrated a notable impact of varying adsorbent dose and mixing speed on dye removal, indicating an increase in removal with the elevation of both parameters.

In comparison to alternative low-cost adsorbents investigated for the removal of methylene blue, the activated biochar synthesized from palm kernel shell (PKS) in the present study demonstrated efficacy, achieving a removal efficiency of 88.4% within a reduced dosage range of 5–25 mg. Although the banana peel biochar pyrolyzed at 500°C for 1 h achieved a superior removal rate of 94%, it needs a longer contact time of 120 min and a higher dosage adsorbent, 0.10 g [5]. Bamboo powder, chemically activated with 3 M KOH and subsequently pyrolyzed at 900°C for 2 h, demonstrated effectiveness by achieving a comparatively higher removal efficiency (99.08%); however, it required a higher adsorbent dosage of 5 g/L [22]. Furthermore, in this study, without chemical activation under microwave treatment, a removal efficiency of 61.61% was achieved using a 25 mg dosage at 350 rpm. These results indicate that PKS activated biochar represents a viable alternative for cost-effective and efficient dye removal from wastewater after chemical activation via microwave heating.

Based on the analysis using Design Expert, the final equation in terms of coded factors is shown in Eq. (3):

where:

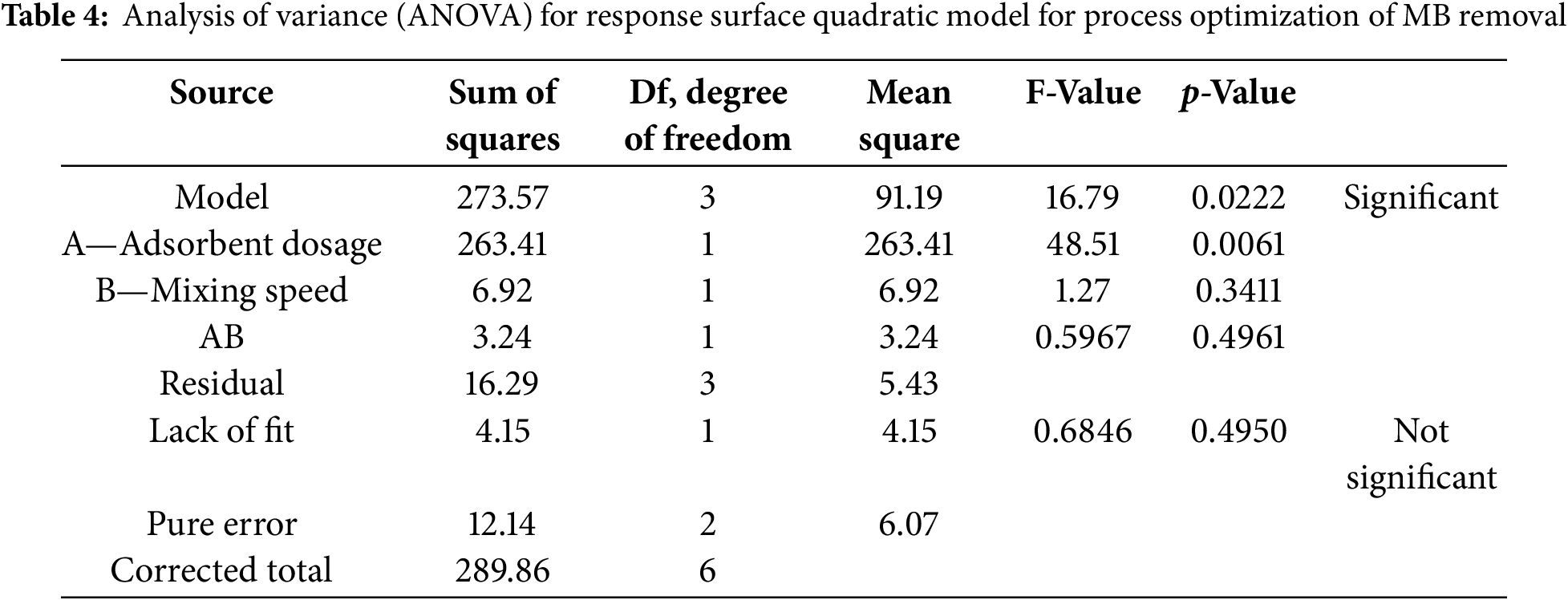

A—Adsorbent dosage (mg)

B—Mixing speed (rpm)

The regression equation for the optimization of process parameters showed that MB removal (%) is a function of the adsorbent dose (A) and mixing speed (B). From the equation, A and B were both positive values, which indicated a positive effect in the increasing percentage of MB removal [30]. On the other hand, AB had negative effects on the percentage of MB removal. Table 4 shows the Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) for the response surface quadratic model. According to the analysis, the model F-value obtained was 16.79, which reflected that the model was significant. Using this model, only 2.22%, a small amount of chance that the model F-value could occur due to noise. In addition, the model was considered significant because values of Prob > F were less than 0.0500.

For this study, A, was found to be significant model terms as the p-value was less than 0.01. In contrast, mixing speed (B) and the interaction between dosage and mixing speed (AB) were not statistically significant.

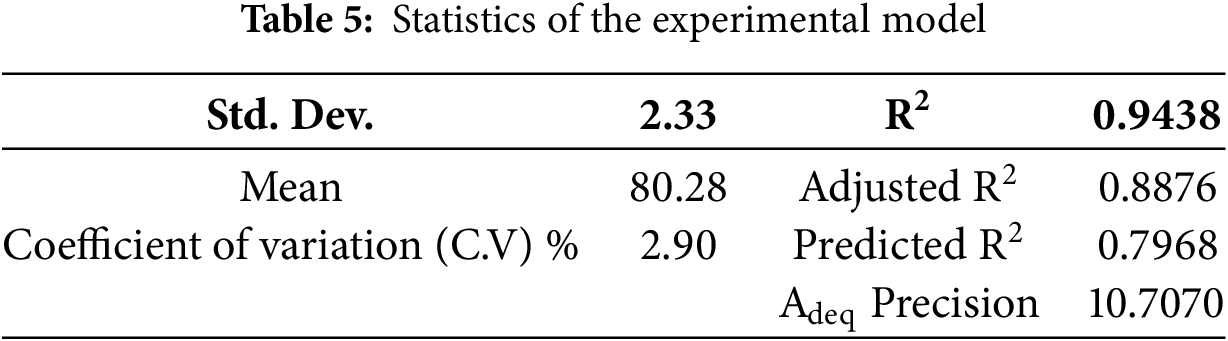

With the lack of fit F-value of 0.68 and based on pure error, it implied that the lack of fit was not significant. Plus, a non-significant lack of fit was good because it indicated that the model was fit. However, there was a 49.50% chance that a lack of fit F-value this large could occur due to noise. Moreover, based on the ANOVA, the R2 for this model was found to be 0.9438 as shown in Table 5. This value reflected that 94.38% of the total variation in the percentage of MB removal attributed to the experimental variables was studied. In the case of signal-to-noise ratio. The value of Adeq Precision was observed to show an adequate signal since the ratio was 10.707. This value was good enough to indicate that this model could be used to navigate the design space of this experiment since a ratio greater than 4 is desirable.

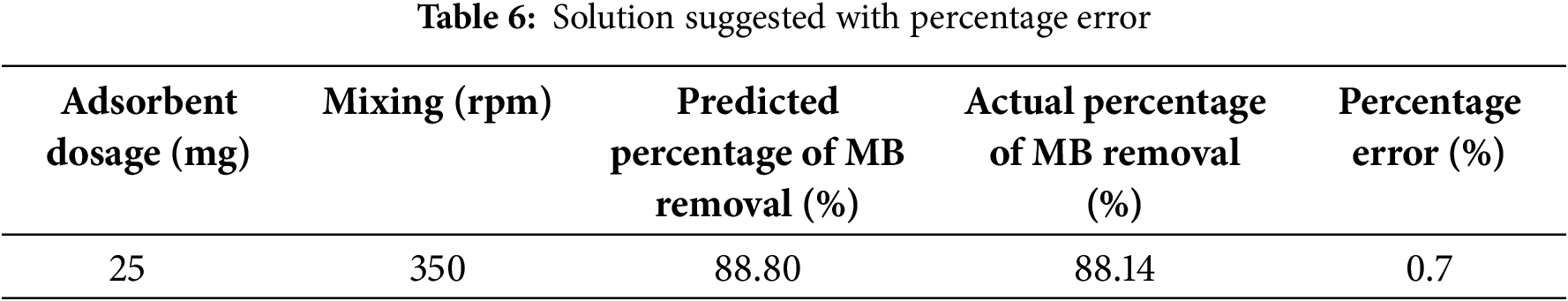

The validation step was crucial to determine the percentage error of the model and determine the consistency of the model based on the percentage of MB removal. In this study, there was only one solution that had been suggested by ANOVA for the validation as shown in Table 6.

Based on the solution suggested, the predicted percentage of MB removal was 88.80% while the percentage of wax removal based on the experimental obtained was 88.14%. Using both values and, the percentage error was calculated and indicating that the model was valid to be used since the percentage error obtained was below 1%.

The present study has demonstrated that activated biochar synthesized from PKS and further activated using microwave heating under normal conditions, in the absence of inert gas, can be an effective alternative for wastewater treatment. The approach represents a low cost proof of concept, offering accessible and scalable routes for biochar production. In this study, acid leaching treatment and microwave activation at 5 to 15 min were successfully conducted. In terms of adsorption capacity, Sample C was proven to have the highest capacity after undergoing leaching process and microwave synthesis for 15 min. From the experimental design and the model, it was shown that the maximum percentage of wax removal (88.14%) was achieved at 25 mg adsorbent dosage and mixing speed of 350 rpm using Sample C. However, the correlation between adsorbent dosage and mixing speed against the rate of adsorption process by an adsorbent is not significant. Analysis using ANOVA revealed significant model with p-values less than 0.05 (Prob > F) and R2 value of 0.9438, indicating a significant quadratic model.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank the International Islamic University for providing the facilities and support.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Sarina Sulaiman; writing, analysis and interpretation of results: Muhammad Faris; writing, data collection and analysis: Muhammad Faris. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Elham P. The production of palm kernel shell charcoal by the continuous kiln method [master’s thesis]. Serdang, Malaysia: Universiti Putra Malaysia; 2001. [Google Scholar]

2. Anisuzzaman SM, Sinring N, Fran Mansa R. Properties tuning of palm kernel shell biochar granular activated carbon using response surface methodology for removal of methylene blue. J Appl Sci Process Eng. 2021;8(2):1002–19. doi:10.33736/jaspe.3961.2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Ariffin MA, Wan Mahmood WMF, Mohamed R, Mohd Nor MT. Performance of oil palm kernel shell gasification using a medium-scale downdraft gasifier. Int J Green Energy. 2016;13(5):513–20. doi:10.1080/15435075.2014.966266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Nuradila D, Ghani W, Alias AB. Palm kernel shell-derived biochar and catalyst for biodiesel production. Malays J Anal Sci. 2017;21(1):197–203. doi:10.17576/mjas-2017-2101-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Gautam S, Khan SH. Removal of methylene blue from waste water using banana peel as absorbent. Int J Sci Env Technol. 2016;5(5):3230–6. [Google Scholar]

6. Banerjee S, Dubey S, Gautam RK, Chattopadhyaya MC, Sharma YC. Adsorption characteristics of alumina nanoparticles for the removal of hazardous dye, Orange G from aqueous solutions. Arab J Chem. 2019;12(8):5339–54. doi:10.1016/j.arabjc.2016.12.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Etim EU. Removal of methyl blue dye from aqueous solution by adsorption unto ground nut waste. Biomed J Sci Tech Res. 2019;15(3):11365–71. doi:10.26717/bjstr.2019.15.002701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Madan S, Shaw R, Tiwari S, Tiwari SK. Adsorption dynamics of Congo red dye removal using ZnO functionalized high silica zeolitic particles. Appl Surf Sci. 2019;487:907–17. doi:10.1016/j.apsusc.2019.04.273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Kyi PP, Quansah JO, Lee CG, Moon JK, Park SJ. The removal of crystal violet from textile wastewater using palm kernel shell-derived biochar. Appl Sci. 2020;10(7):2251. doi:10.3390/app10072251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Hamzeh Y, Ashori A, Azadeh E, Abdulkhani A. Removal of Acid Orange 7 and Remazol Black 5 reactive dyes from aqueous solutions using a novel biosorbent. Mater Sci Eng C. 2012;32(6):1394–400. doi:10.1016/j.msec.2012.04.015. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Khodaie M, Ghasemi N, Moradi B, Rahimi M. Removal of methylene blue from wastewater by adsorption onto ZnCl2 activated corn husk carbon equilibrium studies. J Chem. 2013;2013(1):383985. doi:10.1155/2013/383985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Kandisa RV, Saibaba KN, Shaik KB, Gopinath R. Dye removal by adsorption: a review. J Bioremediat Biodegrad. 2016;7(6):371. doi:10.4172/2155-6199.1000371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Dutta S, Gupta B, Srivastava SK, Gupta AK. Recent advances on the removal of dyes from wastewater using various adsorbents: a critical review. Mater Adv. 2021;2(14):4497–531. doi:10.1039/d1ma00354b. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Yagub MT, Sen TK, Afroze S, Ang HM. Dye and its removal from aqueous solution by adsorption: a review. Adv Colloid Interface Sci. 2014;209:172–84. doi:10.1016/j.cis.2014.04.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Parvulescu AN, Maurer S. Toward sustainability in zeolite manufacturing: an industry perspective. Front Chem. 2022;10:1050363. doi:10.3389/fchem.2022.1050363. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Dune KK, Ademiluyi FT, Nmegbu GCJ, Dagde K, Nwosi-Anele AS. Production, activation and characterisation of PKS-biochar from Elaeis guineensis biomass activated with HCl for optimum produced water treatment. Int J Recent Eng Sci. 2022;9(1):1–7. doi:10.14445/23497157/ijres-v9i1p101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Potnuri R, Surya DV, Rao CS, Yadav A, Sridevi V, Remya N. A review on analysis of biochar produced from microwave-assisted pyrolysis of agricultural waste biomass. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis. 2023;173:106094. doi:10.1016/j.jaap.2023.106094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Uchegbulam I, Momoh EO, Agan SA. Potentials of palm kernel shell derivatives: a critical review on waste recovery for environmental sustainability. Clean Mater. 2022;6:100154. doi:10.1016/j.clema.2022.100154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Zeng X, Hu X, Song H, Xia G, Shen ZY, Yu R, et al. Microwave synthesis of zeolites and their related applications. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2021;323:111262. doi:10.1016/j.micromeso.2021.111262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Mamudu A, Emetere M, Ishola F, Lawal D. The production of zeolite Y catalyst from palm kernel shell for fluid catalytic cracking unit. Int J Chem Eng. 2021;2021(1):8871228. doi:10.1155/2021/8871228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Mulushewa Z, Dinbore WT, Ayele Y. Removal of methylene blue from textile waste water using kaolin and zeolite-x synthesized from Ethiopian kaolin. Environ Anal Health Toxicol. 2021;36(1):e2021007. doi:10.5620/eaht.2021007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Ge Q, Li P, Liu M, Xiao GM, Xiao ZQ, Mao JW, et al. Removal of methylene blue by porous biochar obtained by KOH activation from bamboo biochar. Bioresour Bioprocess. 2023;10(1):51. doi:10.1186/s40643-023-00671-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Dechapanya W, Khamwichit A. Biosorption of aqueous Pb(II) by H3PO4-activated biochar prepared from palm kernel shells (PKS). Heliyon. 2023;9(7):e17250. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e17250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Wang K, Peng N, Zhang D, Zhou H, Gu J, Huang J, et al. Efficient removal of methylene blue using Ca(OH)2 modified biochar derived from rice straw. Environ Technol Innov. 2023;31:103145. doi:10.1016/j.eti.2023.103145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Abdul Raman AA, Buthiyappan A, Chan AA, Khor YY. Oxidant-assisted adsorption using lignocellulosic biomass-based activated carbon. Mater Today Proc. 2023;141:285. doi:10.1016/j.matpr.2022.12.204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Okoroigwe EC, Saffron CM, Kamdem PD. Characterization of palm kernel shell for materials reinforcement and water treatment. J Chem Eng Mater Sci. 2014;5(1):1–6. doi:10.5897/jcems2014.0172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Small JA. The analysis of particles at low accelerating voltages (≤10 kV) with energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy EDS. J Res Natl Inst Stand Technol. 2002;107(6):555–66. doi:10.6028/jres.107.047. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Sarawak UM, Hwong CN, Sim SF, Sarawak UM, Kho LK, Board MPO, et al. Effects of biochar from oil palm biomass on soil properties and growth performance of oil palm seedlings. J Sustain Sci Manage. 2022;17(4):183–200. doi:10.46754/jssm.2022.4.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Prabakaran E, Pillay K. Synthesis of palm kernel shells-biochar adsorbent for removal of methylene blue and then reused for latent fingerprint detection using spent adsorbent. Green Anal Chem. 2025;13:100259. doi:10.1016/j.greeac.2025.100259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Alam MZ, Bari MN, Kawsari S. Statistical optimization of methylene blue dye removal from a synthetic textile wastewater using indigenous adsorbents. Environ Sustain Indic. 2022;14:100176. doi:10.1016/j.indic.2022.100176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Kataya G, Issa M, Badran A, Cornu D, Bechelany M, Jellali S, et al. Dynamic removal of methylene blue and methyl orange from water using biochar derived from kitchen waste. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):29907. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-14133-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools