Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Evaluation of Strip-Processed Cotton Stalks as a Raw Material for Structural Panels

1 Department of Sustainable Bioproducts, Mississippi State University, P.O. Box 9820, Starkville, MS 39762, USA

2 USDA Agricultural Research Service, Research Soil Scientist, Starkville, MS 39762, USA

* Corresponding Author: Mostafa Mohammadabadi. Email:

Journal of Renewable Materials 2026, 14(1), 3 https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2025.02025-0146

Received 22 July 2025; Accepted 23 September 2025; Issue published 23 January 2026

Abstract

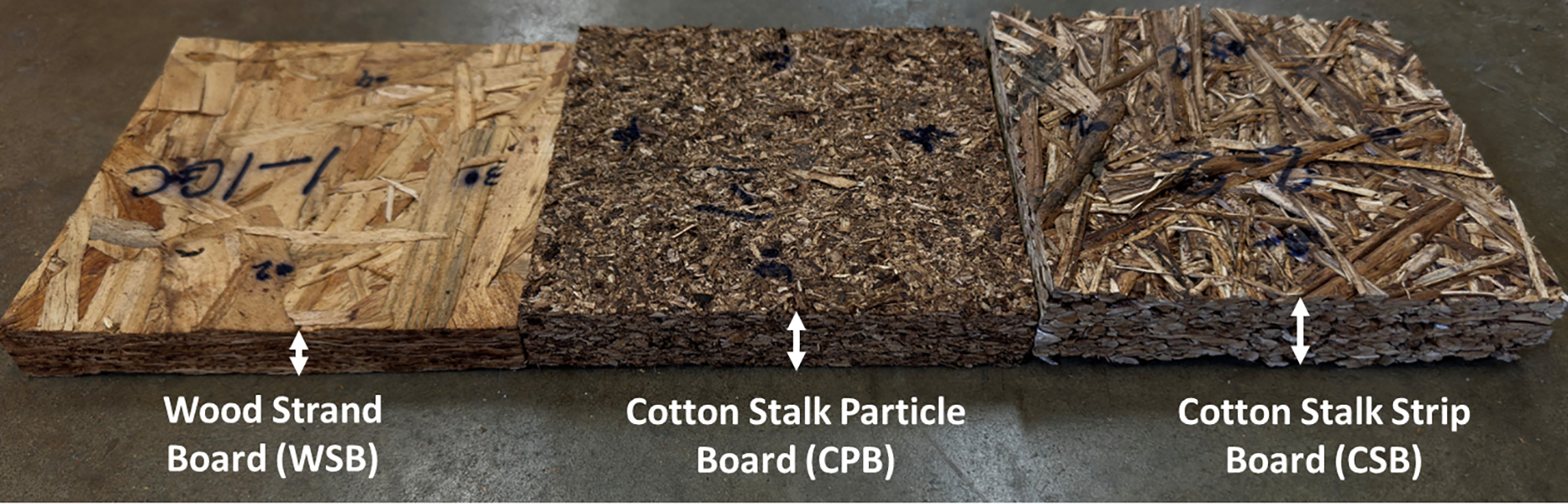

This study explores a novel method for processing cotton stalks—an abundant agricultural byproduct—into long strips that serve as sustainable raw material for engineered bio-based panels. To evaluate the effect of raw material morphology on panel’s performance, two types of cotton stalk-based panels were developed: one using long strips, maintaining fiber continuity, and the other using ground particles, representing conventional processing. A wood strand-based panel made from commercial southern yellow pine strands served as the control. All panels were bonded using phenol-formaldehyde resin and hot-pressed to a target thickness of 12.7 mm and density of 640 kg/m3. Their mechanical and physical properties were evaluated through internal bond, bending, thickness swelling, and water absorption tests. Both cotton stalk-based panels showed improved bonding performance compared to the control. The internal bond of the strip-based panel was nearly four times higher than that of the control, while the particle-based panel exceeded it by a factor of two. The strip-based panel showed approximately 15% lower bending stiffness than the wood strand-based panel, yet it surpassed it in load-carrying capacity by 5%. In contrast, the particleboard showed significantly lower bending performance than the strip-based and control panels, despite particle processing being a more conventional method. Both cotton stalk-based panels exhibited higher water absorption and thickness swelling than the wood strand panel. Overall, cotton stalk-based panels—particularly those using strip processing—show promising mechanical properties, suggesting potential applications in sheathing, furniture, and interior paneling. However, improvements in dimensional stability are needed for broader use.Keywords

The global population is projected to reach 9.6 billion by 2050, leading to increased food demand and the expansion of agricultural activities worldwide [1]. Agriculture remains the world’s largest industry, employing over one billion people and generating more than USD 1.3 trillion in annual economic output [2]. It occupies approximately 38% of the earth’s land surface and serves as a vital foundation for both food and fiber production [3]. While the majority of agricultural land is dedicated to growing food crops, a significant portion supports the cultivation of fiber crops, essential to the global textile and manufacturing sectors. Among these, cotton stands out as the most widely grown natural fiber crop, contributing over 80% of natural fiber production by weight [4]. Its distinctive fiber structure makes it highly valuable across industries, including fashion, textiles, and healthcare [5]. Recent estimates suggest that more than 25 million tons of cotton are produced annually worldwide, with India, China, the United States, Pakistan, and Brazil being the leading producers [6,7]. The global cotton market was valued at USD 41.78 billion in 2024 and is anticipated to reach 53.29 billion by 2033 [8]. In the United States alone, cotton is cultivated on over 10 million acres annually, making it one of the nation’s most significant agricultural exports [9].

Cotton cultivation generates a significant amount of agricultural residue in the form of stalks after harvesting. With a typical straw-to-fiber ratio of approximately 5:1 [10], an estimated 2–3 t of cotton stalk residue are produced per hectare [11]. A large portion of these stalks is either openly burned in the field to clear land or discarded in landfills. Open burning releases toxic gases—such as carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, nitrogen oxides, hydrocarbons, and fine particulate matter—that harm air quality and public health [12]. Consequently, several countries have implemented bans on open field burning to mitigate these risks [13–15]. Alternative disposal methods, such as burying, also present challenges. The fibrous, lignocellulosic nature of cotton stalks makes them resistant to decomposition, and they are known carriers of agricultural pests like Pectinophora gossypiella (pink bollworm), further complicating safe disposal [16]. These environmental, agricultural, and logistical concerns underscore the need for sustainable utilization strategies. One promising solution involves repurposing cotton stalks into long-lived engineered bio-based products. Unlike short-lived uses, such as composting or fuel, where carbon is rapidly released, structural applications like particleboard can retain carbon for extended periods. This contributes to climate change mitigation goals and provides a renewable, underutilized lignocellulosic feedstock for regions with limited forest resources.

Engineered wood-based panels such as particleboard and oriented strand board (OSB) are widely used in construction, furniture, cabinetry, and interior paneling. With the increasing popularity of engineered wood products, recent researchers have adopted innovative strategies to enhance structural performance and promote efficient material utilization. These strategies include densification techniques [17], the development of novel products using corrugated panels [18], and the use of underutilized hardwood species [19]. Concurrently, increasing efforts have focused on converting agricultural residues into value-added products. Researchers have investigated a variety of agro-wastes in the development of particleboards and engineered bio-based products, such as rice straw [20–22], rice husk [23–25], wheat straw [25,26], sugarcane bagasse [27], hemp [28,29], bamboo [30], and grass [31,32]. These alternative materials help reduce reliance on timber while mitigating the environmental impact of residue disposal. Among these options, cotton stalk offers a particularly strong potential for producing sustainable, high-performance panels due to their abundance and woody texture, which provides fibrous structure similar to that of hardwoods [33,34].

Several studies have demonstrated the potential of cotton stalks in particleboard applications. Guler and Ozen reported the viability of particleboards made from debarked cotton stalks as an alternative raw material [33]. Alma et al. fabricated boards using cotton carpels bonded with urea formaldehyde (UF) and melamine urea formaldehyde (MUF) resins, achieving performance comparable to that of general grade particleboards [35]. Kadja et al. used bone resin in cotton stems panels, reporting that the mechanical properties met American National Standards Institute (ANSI) requirements [36]. Other researchers improved board strength by blending cotton stalks with wood fibers at optimal ratios [37]. Nazerian et al. analyzed the effects of press temperature and panel density on boards made from debarked stalks [38]. Further enhancements were achieved by Yasar & İçel through NaOH treatment of cotton particles [39], while Scatolino et al. evaluated hybrid panels combining cotton waste with eucalyptus wood [40]. Nguyen evaluated the effects of particle opening sizes and the amount of cotton boll residue on the mechanical and physical properties of boards fabricated from whole cotton stalks [41].

Unlike particleboard fabrication, Chen et al. [42] developed panels using entire cotton stalks (approximately 450 mm in length) combined with a konjac glucomannan–chitosan adhesive [42]. However, instead of utilizing whole stalks, processing the stalks into thin, elongated strips offers several advantages. First, since panel density is a critical factor influencing the mechanical performance of bio-based products, finer strips enable a more uniform density distribution both along the panel surface and through its thickness compared to thick, unprocessed stalks. Second, thin strips facilitate more effective mechanical interlocking between elements, enhancing stress transfer across the panel and improving load-carrying capacity. Third, the processing procedure splits and opens the stalk, exposing the foamy hurd core—an anatomically weak, highly porous region—to adhesive penetration, thereby improving bonding and contributing to higher internal bond strength. Similar processing concepts have been successfully applied in bamboo and wood scrimber production, where breaking down raw materials into elongated elements has been shown to enhance strength, stiffness, and overall performance [43,44]. The potential benefits of processing cotton stalks into thin, long strips have not been examined.

In this study, a novel strip-processing method was introduced for cotton stalks to produce long, continuous elements aimed at improving stress transfer and maintaining more uniform properties in structural panels. For comparison, particleboards were also fabricated using conventional grinding, which is the most common method for processing cotton stalks. This enabled the evaluation of the effectiveness of this strip-processing method compared to traditional particle processing. In addition, oriented strand board (OSB), a widely used commercial product with a well-established market, was included as a benchmark. Overall, the study aims to develop and evaluate structural panels that can be potentially used in sheathing, furniture, cabinetry, and internal paneling, made from cotton stalks in both strip and particle forms, with performance benchmarks established using a wood strand board as a control.

2.1 Materials and Sample Preparation

The cotton stalks harvested from the cotton farm at Mississippi State University, MS, USA, were selected as the primary raw material for this study. The initial processing involved removing cotton bolls and branches from the stalks, as illustrated in Fig. 1. The stalks were cut into small pieces approximately 150 mm in length, similar to commercial wood strands. These pieces were soaked in water for 24 h to soften the fibers and facilitate their processing into strips.

Figure 1: (a) Collecting cotton stalks from a farm; (b) cotton stalks with bolls and branches; (c) stalks after removing bolls and fine branches

After soaking, the bark was manually removed as shown in Fig. 2b. To enhance both the interlocking effect and bonding performance, it is essential to process the cotton stalks into finer pieces, using a method similar to the scrimming process employed for small-diameter logs [44,45] and bamboo [43,46]. Therefore, a manual noodle maker was used to process the softened stalks into strips, as shown in Fig. 2c. This process not only increases the surface area available for resin application, improving bonding performance, but also facilitates more uniform compaction during hot pressing. The use of these strips rather than stalks enables better mat consolidation and a more uniform density distribution. The Fig. 2d shows the long, slender cotton stalk strips produced using the noodle maker, prepared and ready for panel fabrication.

Figure 2: Processing steps: (a) wet cotton stalks; (b) bark removal; (c) converting stalks into strips using a manual noodle maker; (d) cotton stalk strips prepared for panel fabrication

For particleboard analogs, cotton stalks were processed using a laboratory-scale hammer mill, as shown in Fig. 3a, to produce fine particles. The final processed particles are shown in Fig. 3b. For comparative analysis, commercial Southern yellow pine strands supplied by West Fraser Company in Guntown, MS, USA, were used to fabricate control panels as shown in Fig. 3c. All bio-based materials, including cotton stalk strips, cotton stalk particles, and wood strands, were oven-dried to a moisture content of 3%–5%.

Figure 3: Preparation of cotton stalk particles for particleboard analogs: (a) hammer milling of cotton stalk; (b) cotton stalk particles after processing; (c) wood strands

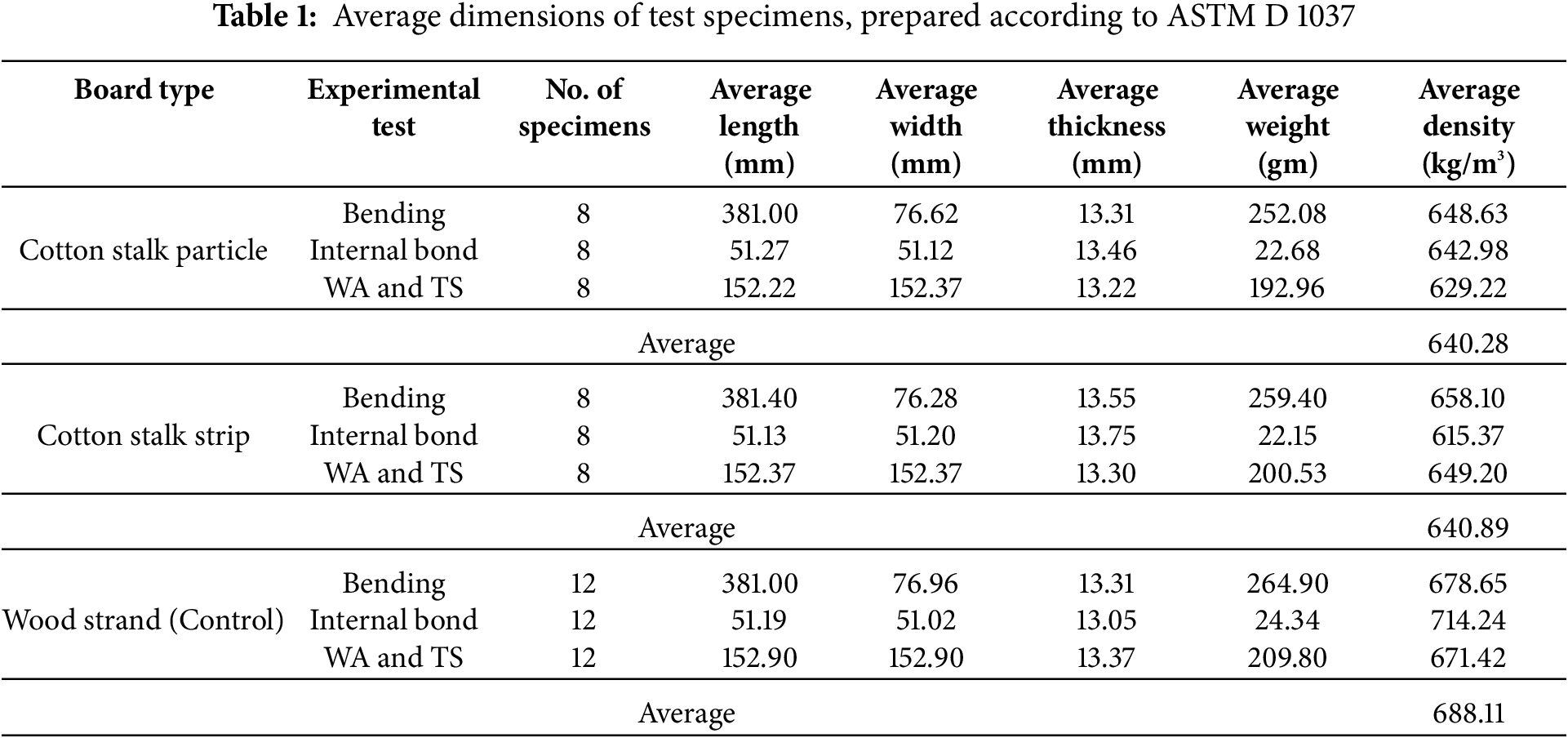

Phenol-formaldehyde (PF) resin was used as a binder and was applied at a target resin content of 5% (based on oven-dry weight). The resin was sprayed evenly onto the bio-based materials inside a rotating drum blender to ensure uniform coating. Separate batches were prepared for the three board types: cotton stalk strip board (CSB), cotton stalk particle board (CPB), and wood strand board (WSB), which served as the control. Resin-coated materials were manually formed into mats, known as preform, using a forming box to ensure uniform thickness. Cotton stalk strips and wood strands were manually aligned in parallel orientation using a mechanical orienter. Each mat was hot-pressed at 160°C for 5 min to achieve a target thickness of 12.7 mm and a target density of 640 kg/m3. After pressing and conditioning, the fabricated panels were trimmed, and test specimens were cut for various evaluations, including internal bond, bending, water absorption, and thickness swelling. The average dimensions of these test specimens are summarized in Table 1.

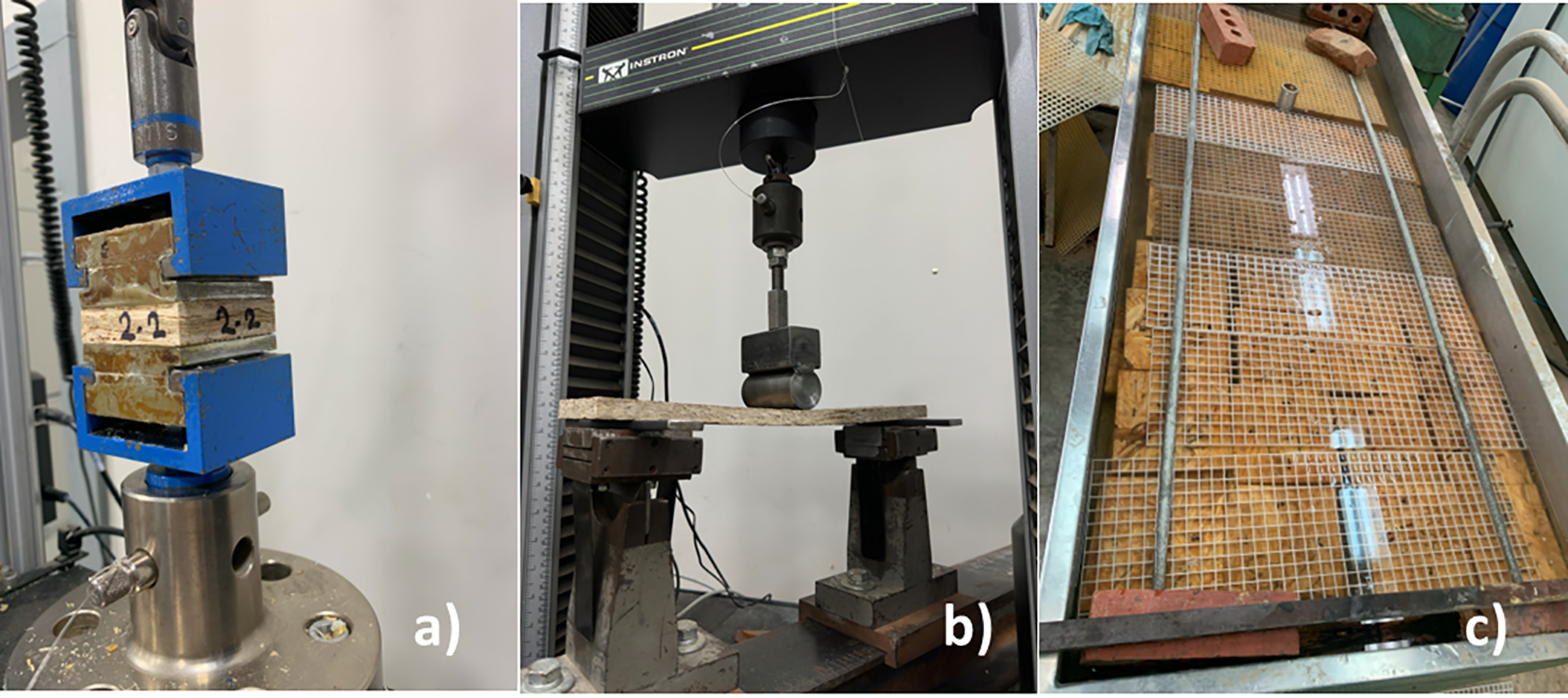

The mechanical and physical properties of the fabricated panels were evaluated through a series of standardized tests following American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM D1037) [47] to assess their structural viability. To evaluate the feasibility of this process, three key performance parameters were investigated at this phase: internal bond strength, bending performance (modulus of rupture and modulus of elasticity), and dimensional stability through water absorption and thickness swelling. It is important to note that the authors plan to conduct additional tests in future studies, including tensile, compression, hardness, and nail withdrawal tests. Internal bond test measures the tensile strength along the thickness of the panel, indicating the effectiveness of adhesive bonding between biobased fibers. Each specimen was centrally glued to two aluminium blocks and loaded in tension, as shown in Fig. 4a, using a universal testing machine at a loading rate of 1 mm/min until failure. The maximum load was recorded and used to calculate the IB strength using Eq. (1).

where, Pmax = Concentrated applied load on the sample.

Figure 4: Experimental testing setup: (a) internal bond test; (b) bending test; (c) water absorption and thickness swelling test

b, and d = length and width of the sample.

Bending performance was evaluated using a three-point bending test, as shown in Fig. 4b. Specimens were simply supported with a clear span of 304.8 mm and loaded at the mid-span using a central point load. The load was applied at a rate of 6 mm/min until failure. The load-deflection behaviour was recorded using a displacement transducer. The slope of the load-deflection curve was used to calculate the bending stiffness using Eq. (2), and the maximum load before failure was used to determine the maximum normal stress, known as the modulus of rupture (MOR), using Eq. (3).

where, E = Modulus of elasticity

I = Second moment of area (moment of inertia) of the specimen’s cross-section

P = Bending load applied at mid-span

∆ = Specimen deflection at mid-span

L = Span length

m = P/∆ is the slope of the load-deflection curve in the elastic region

b = Specimen width

d = Specimen depth.

Water absorption and thickness swelling were measured to evaluate the dimensional stability of the panels. This test followed the 24-h soak procedure outlined in ASTM D1037, as shown in Fig. 4c. Specimens were weighed, and their thickness was measured before being immersed in distilled water at room temperature. After 2 and 24 h, samples were removed, wiped to remove excess water, reweighed, and remeasured. Water absorption was determined as the percentage increase in weight, and thickness swelling as the percentage increase in thickness.

This section presents experimental results for the mechanical properties, specifically internal bond (IB), bending strength, water absorption, and thickness swelling of three panel types: cotton stalk strip board (CSB), fabricated using cotton stalk strips; cotton stalk particle board (CPB), fabricated from cotton stalk particles; and wood strand board (WSB), fabricated from commercial wood strands. The mechanical performance of each panel type was evaluated to assess the viability of cotton stalk-based panels compared to those made from wood strands. All reported values represent the average across replicate specimens, with standard deviations calculated to capture variability.

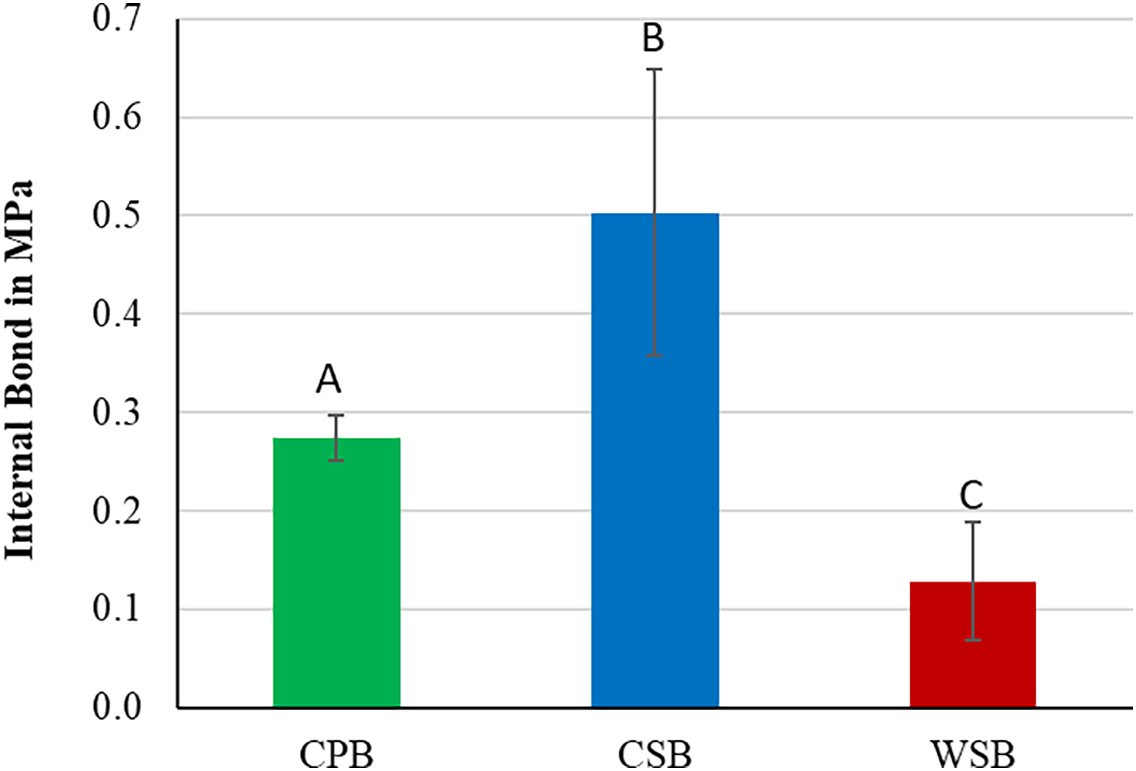

Internal bond strength, which represents the tensile strength perpendicular to the panel surface, reflects the effectiveness of bonding between fibers. Fig. 5 presents the IB values for CSB, CPB, and WSB panels. Among the three, CSB panels exhibited the highest IB strength, followed by CPB panels. The WSB panels showed the lowest IB strength among the three, despite all panels being manufactured using the same resin type (phenol-formaldehyde), resin content (5%), and processing conditions. The relatively low performance of WSB panels may be attributed to limitations in the resin curing process within the panel cores. Unlike industrially manufactured oriented strand board (OSB) panels which typically uses polymeric methylene diphenyl diisocyanate (pMDI) in the core due to its lower curing temperature and faster reactivity [48], the control panel in this study was fabricated entirely with phenol-formaldehyde (PF) adhesive to ensure consistent comparison. PF resin requires higher temperatures and longer press times to cure fully [49], which may have led to precuring and incomplete bonding in the panel core. This likely reduced the IB strength of the WSB compared to both the cotton-based panels and standard commercial OSB products. In contrast, both CSB and CPB demonstrated significantly higher IB values than WSB. This enhanced performance may be due to improved compatibility between cotton fibers and PF resin. While further studies are needed, the results suggest that PF may form more effective bonds with cotton-based materials under the same processing conditions.

Figure 5: Internal bond strength of different panel types

Between the two cotton stalk-based panels, the CSB panel exhibited the highest IB strength, nearly four times greater than that of WSB and twice that of CPB. This difference is attributed to differences in resin distribution. The CSB panels were composed of thicker, chunkier cotton stalk strips, with a smaller surface area per unit volume. Given the same resin content, this resulted in more adhesive being available per unit surface area, leading to stronger internal bonds. In contrast, the CPB panels consisted of finer particles with a higher surface area, leading to a thinner resin distribution and consequently lower bond strength.

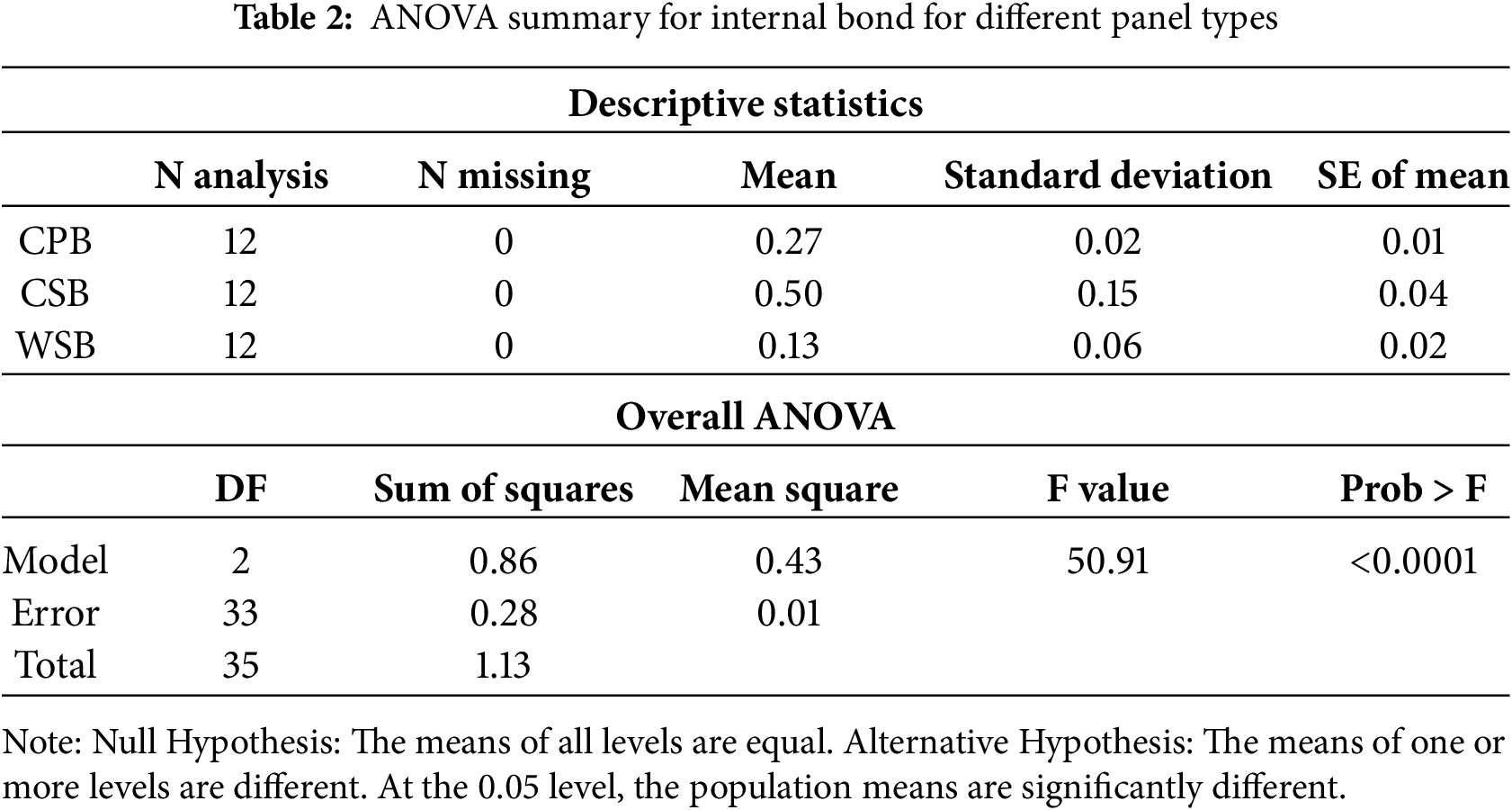

To statistically validate the performance differences, a one-way ANOVA was conducted as shown in Table 2. The results produced a highly significant F-value of 50.91 (p < 0.0001), confirming that the mean IB strength values across the three panel types differed significantly at the 95% confidence level. Moreover, the CSB group showed a larger standard deviation than the other two groups, indicating greater variability, most likely due to inconsistencies in the manual processing of cotton stalks into strips. Overall, the findings indicate that cotton stalk fibers, whether in strip or particle form, exhibit better bonding performance with PF resin than wood fibers at the equivalent resin content.

Compared to similar studies, the CSB in the present work, manufactured from cotton stalk strips, outperformed the oriented cotton stalk boards, fabricated from whole cotton stalks, reported by Chen et al., who achieved an IB value of only 0.35 MPa at a density of 0.6 g/cm3 using a konjac glucomannan–chitosan adhesive with 10% resin content and unprocessed whole cotton stalks [42]. This comparison underscores the importance of processing cotton stalks into strips, which substantially enhances bonding performance. Guler and Ozen reported IB values ranging from 0.29 to 0.40 MPa, depending on resin content, for cotton stalk particle boards, which are lower than our CSB results and comparable to those of CPB panels [33].

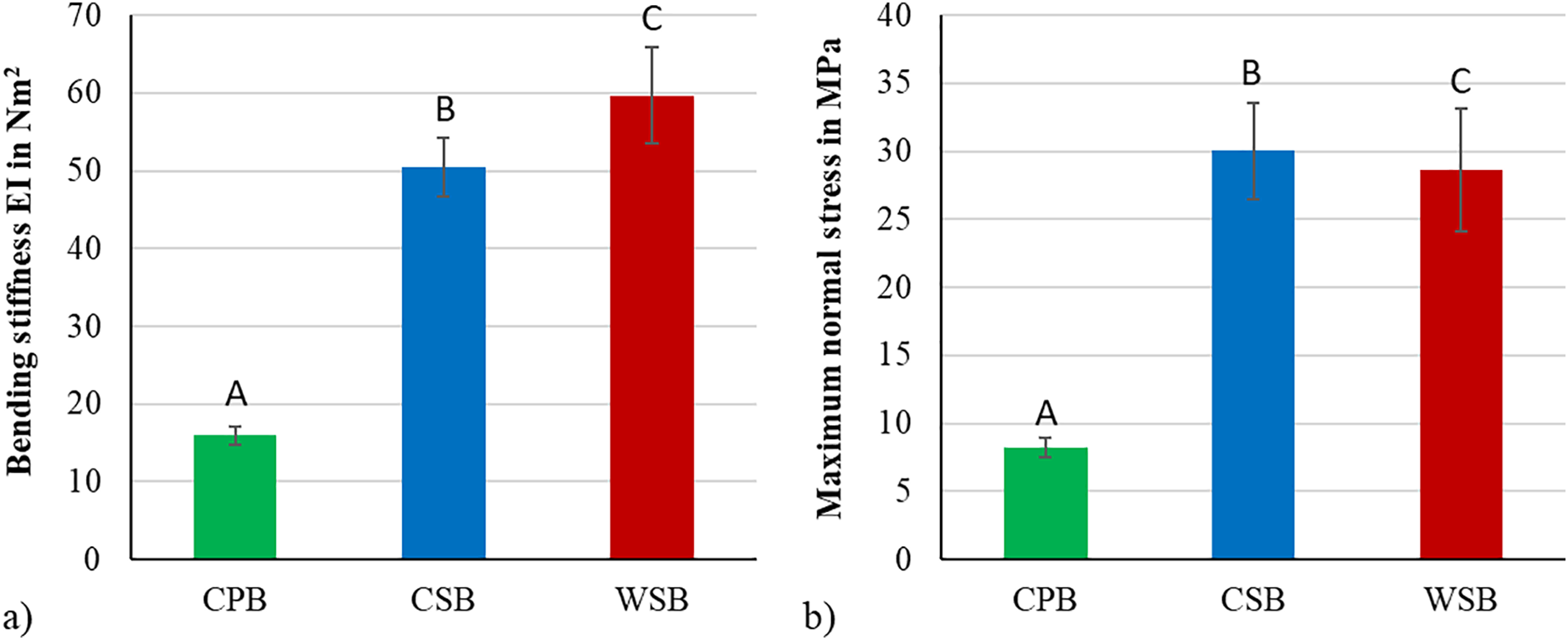

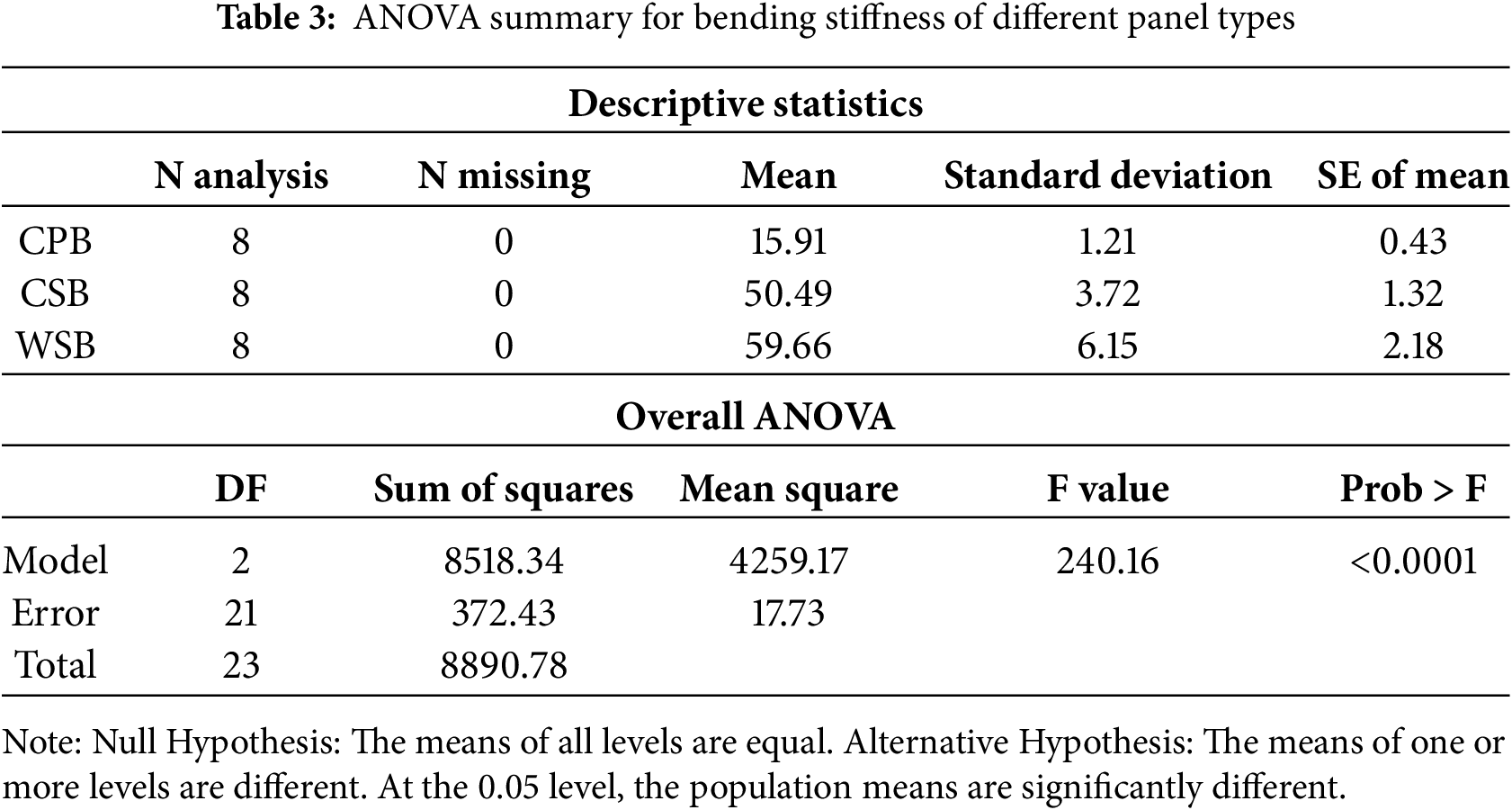

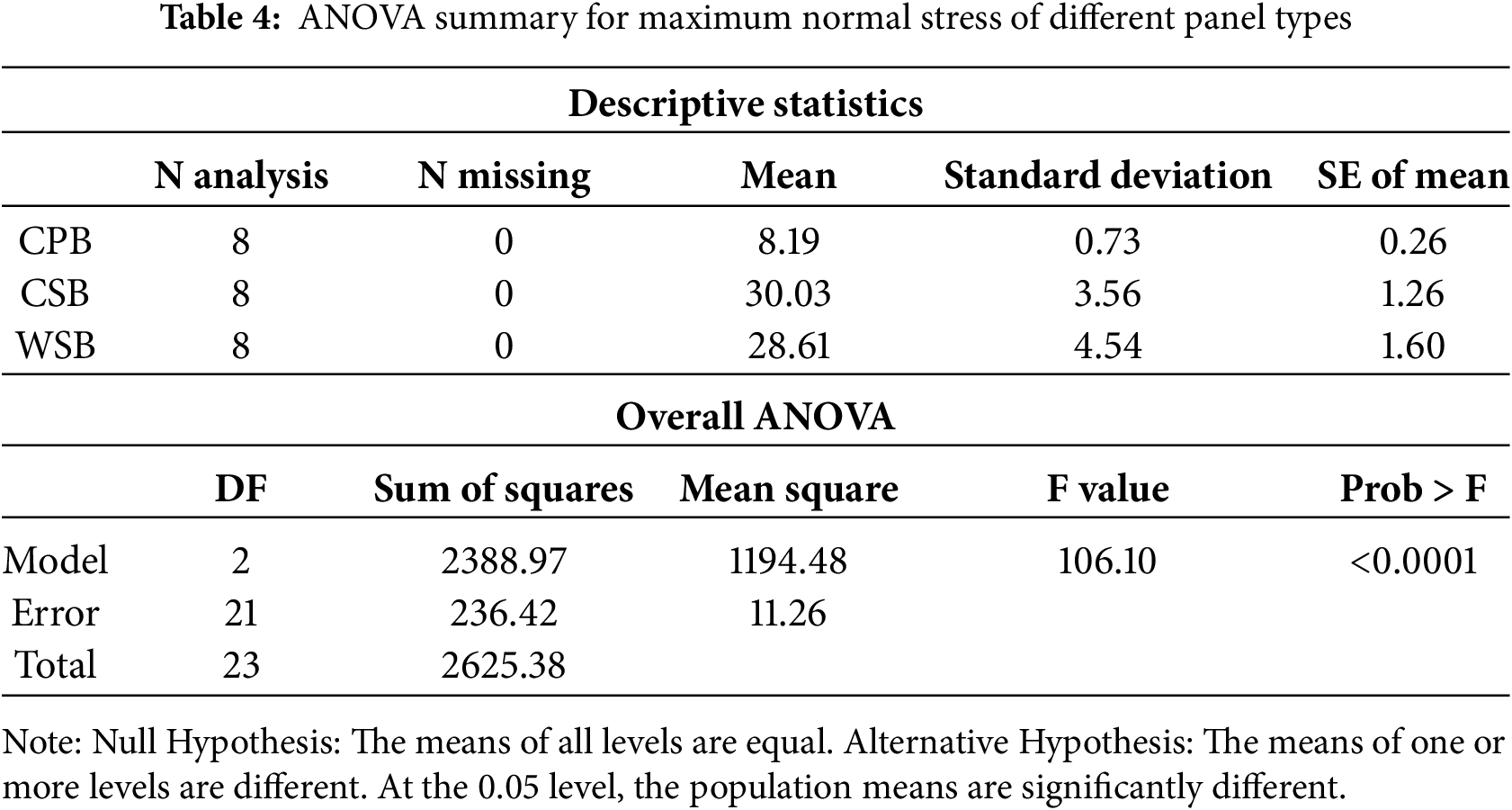

The results of the three-point bending tests, evaluating bending stiffness and maximum normal stress for the three panel types are presented in Fig. 6. Among them, cotton stalk particle board (CPB) exhibited the lowest bending stiffness, followed by cotton stalk strip board (CSB), while wood strand board (WSB) showed the highest bending stiffness (Fig. 6a). The reduced stiffness of the CPB is primarily due to its short fiber length, which limits effective load transfer under flexural stress. In contrast, CSB panels, fabricated using longer, aligned cotton stalk strips, demonstrated a 3.2-fold improvement in bending stiffness relative to CPB. This highlights the importance of fiber length and alignment in enhancing flexural rigidity. Although the cotton stalk strips were comparable in length to the wood strands, CSB still exhibited about 15% lower bending stiffness than WSB. Since the moment of inertia (I) was constant across all panel types owing to their identical dimensions, this difference can be attributed primarily to the modulus of elasticity (E) of the constituent materials. This indicates that cotton stalk strips likely possess a lower modulus of elasticity compared to wood strands, thereby reducing the overall stiffness of CSB panels. To verify this hypothesis, future work should include direct testing of individual elements, such as cotton stalk strips and wood strands, to better quantify their intrinsic elastic properties and clarify their contributions to panel performance. Additionally, a one-way ANOVA analysis of bending stiffness (Table 3), produced a highly significant F-value of 240.16 (p < 0.0001), confirming that the mean bending stiffness values among the three panel types differ statistically at the 95% confidence level.

Figure 6: Bending results of different panel types: (a) bending stiffness (EI); (b) maximum normal stress

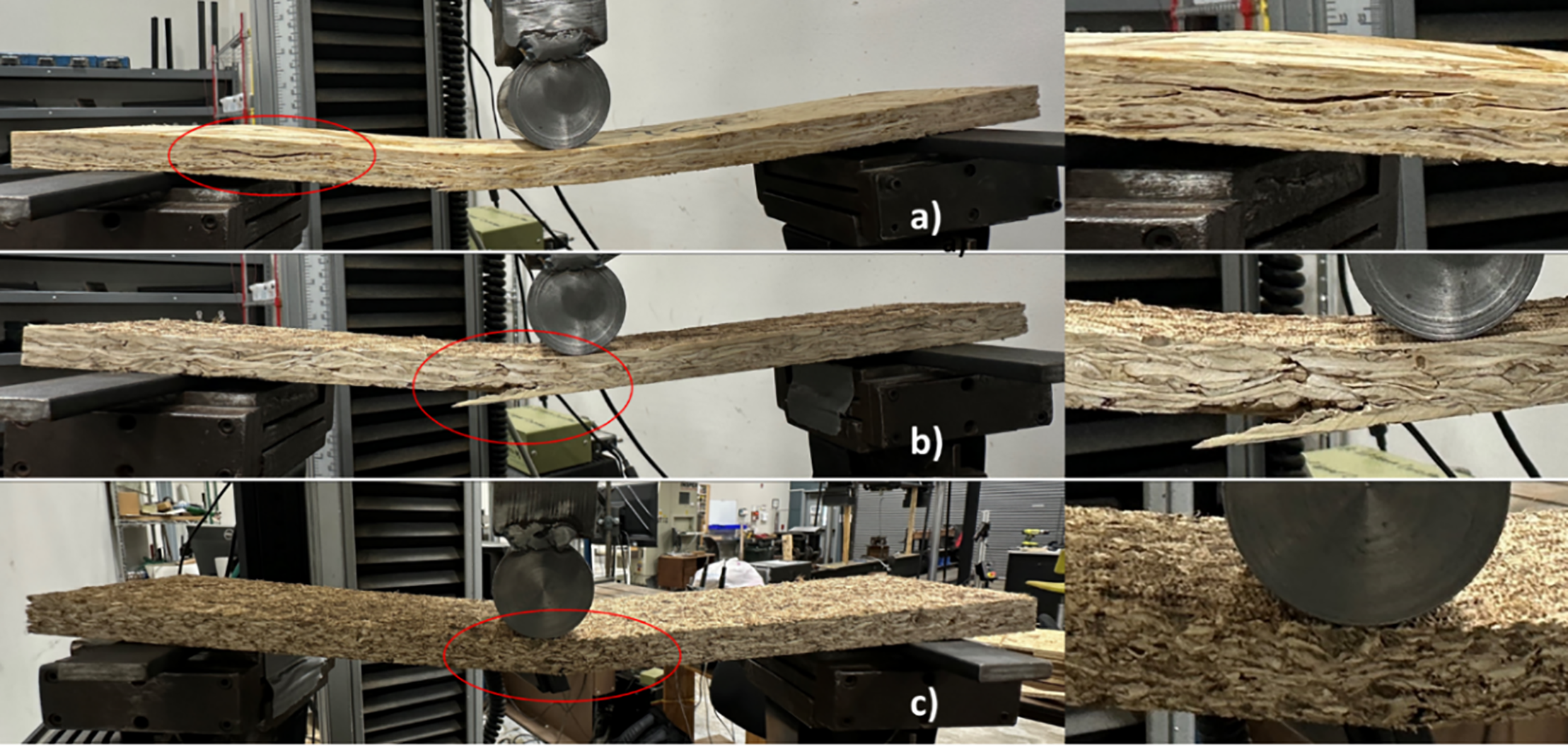

In terms of failure mode, both CPB and CSB panels exhibited typical bending failure, marked by tension-induced rupture at the outer fiber. In contrast, the WSB panel failed in shear (Fig. 7), indicating weak bonding in the core region, consistent with its lower internal bond (IB) strength. Unlike commercial OSB panels that often incorporate pMDI in the inner layers to improve curing and bond quality, the uniform use of PF resin in this study likely led to incomplete curing in the core. Because CPB and CSB experienced bending-type failure, the maximum normal stress at the outermost fiber can be considered as their Modulus of Rupture (MOR). In contrast, for WSB, shear failure means that the measured maximum normal stress does not reflect its true MOR; the actual value is expected to be higher.

Figure 7: Failure mode of three different panels: (a) wood strand board (WSB); (b) cotton stalk strip board (CSB); (c) cotton stalk particle board (CPB)

As shown in Fig. 6b, CSB panels achieved the highest MOR, outperforming WSB by approximately 5%. This enhanced performance is likely due to stronger bonding between the PF resin and cotton stalk strips, particularly within the core, resulting in more effective stress transfer under flexural loading. In comparison, WSB’s weaker core bonding limited its load-carrying capacity. CPB panels made with short cotton fibers, demonstrated the lowest MOR, nearly 3.6 times lower than that of CSB, underscoring the significance of fiber length and continuity in resisting flexural stresses. Given their limited bending capacity, CPB panels are better suited for non-load-bearing applications such as insulation boards, sound-absorbing panels, cabinetry, furniture, or as core materials in sandwich panels for interior building use. As shown in Table 4, the one-way ANOVA performed on maximum normal stress revealed a statistically significant F-value of 106.10, confirming that the mean values among the three panel types differ significantly at the 95% confidence level.

When comparing the bending results with the literature, the results obtained for CPB were found to be slightly lower. Guler and Ozen reported that the maximum normal stress for a particleboard made with cotton stalks and a density of 0.6 g/cm3 ranged from 10 to 12 MPa, depending on the different resin ratios [33]. Similarly, Kadja et al. reported 11 MPa for the same, which were pressed for 25 min [36].

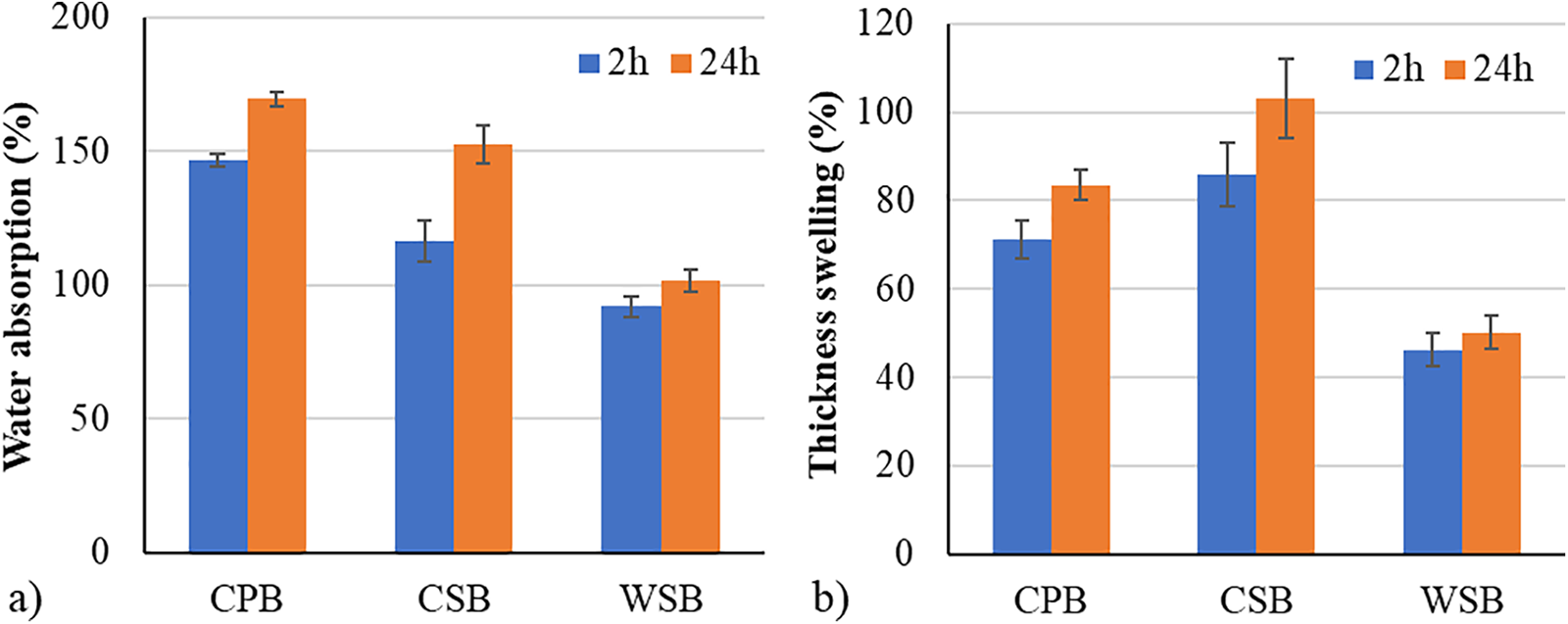

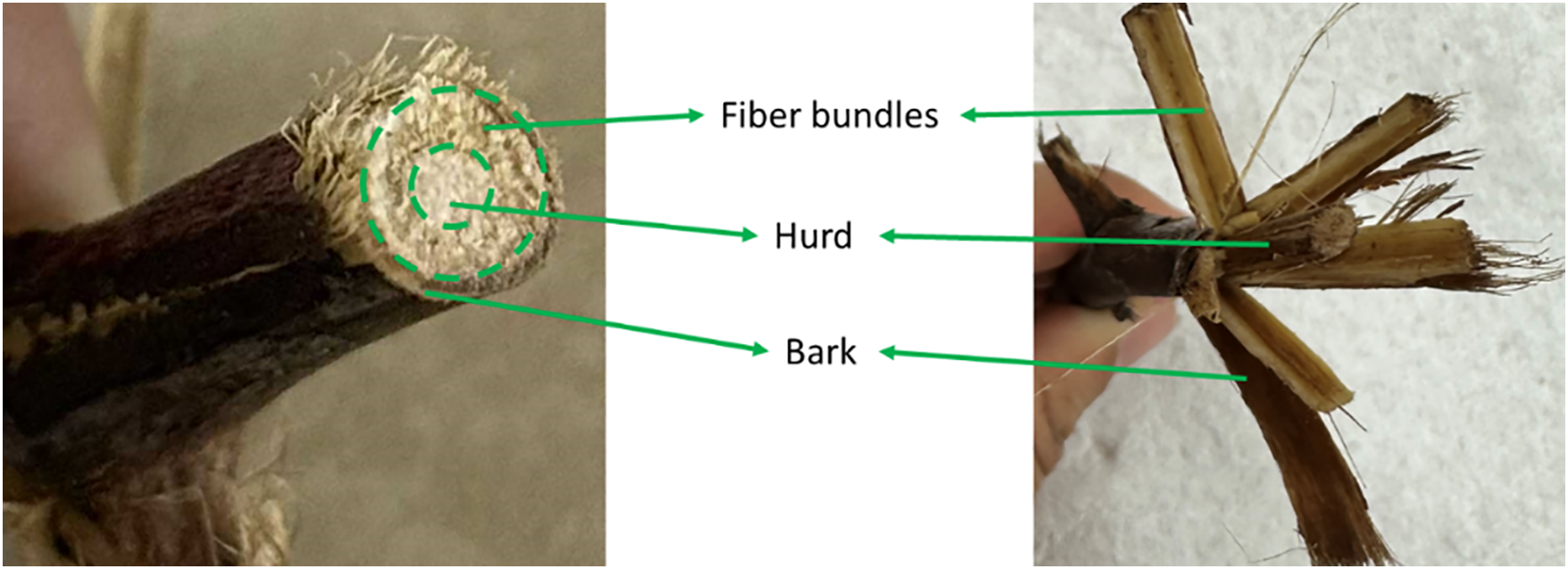

Dimensional stability of these bio-based panels was evaluated by immersing them in water and measuring the water absorption (WA) and thickness swelling (TS). These properties indicate the panel’s resistance to moisture-induced deformation, which is essential for durability in practical applications. WA and TS results for all three panel types after 2 and 24 h of water immersion are presented in Fig. 8. The WSB panels exhibited the lowest water absorption at both intervals, followed by CSB and then CPB (Fig. 8a). The higher water absorption observed in the cotton-based panels is attributable to the anatomical structure of the cotton stalk. As shown in Fig. 9, the hurd, characterized by its foamy and porous texture, is particularly susceptible to moisture uptake, resulting in elevated overall water absorption in both CSB and CPB panels compared to the wood strands used in WSB. Between the two-cotton stalk-based panels, CPB showed 25% and 11% higher water absorption than CSB after 2 and 24 h, respectively. This difference is primarily attributed to the finer particle size and greater surface area of CPB, which facilitate greater moisture intake. Additionally, the lower internal bond strength of CPB compared to CSB may have contributed to weaker adhesive bonding, thereby further enhancing its susceptibility to moisture penetration. For particleboards made with cotton stalk bonded with bone adhesive at comparable density and resin content, Kadja et al. reported even higher WA values of approximately 155% (2 h) and 211% (24 h), indicating that the present CSB and CPB panels performed moderately better [36].

Figure 8: Dimensional stability test on three different panels: (a) water absorption; (b) thickness swelling

Figure 9: Anatomical structure of cotton stalk showing hurd (center), fiber bundles (middle), and bark (outer layer)

Consistent with the water absorption trends, wood strand board (WSB), fabricated with wood strands exhibited the lowest TS values, reflecting superior dimensional stability as shown in Fig. 8b. However, despite having lower water absorption than the cotton stalk particle board (CPB), the cotton stalk strip board (CSB) displayed the highest TS, 20% and 23% greater than CPB after 2 and 24 h of immersion, respectively. While a parallel relationship between water absorption and thickness swelling was expected, this unexpected divergence suggests that additional mechanisms may be involved. The CSB was manufactured using thicker elements (cotton stalk strips) compared to the particles used in CPB, resulting in a higher degree of compression during hot pressing. Specifically, the preform thickness for CSB was approximately 165 mm, nearly double that of CPB at 89 mm, while the WSB preform was about 120 mm. This likely created greater compaction ratio, which were released as “spring-back” upon water immersion. This finding underscores the importance of optimizing strip geometry, such as producing thinner strips, to help mitigate swelling. Fig. 10 provides a visual comparison of panel samples made from these natural fibers, highlighting the variation in thickness swelling after the water absorption test. The thickness swelling for layered cotton particleboard with Ureal Formaldehyde resin studied by Guler and Ozen was lower reporting 26% for 2 h and 35% for 24 h than those recorded for CPB in the present study [33].

Figure 10: Visual representation of thickness swelling comparison for three different panels after water absorption test. The panels, from left to right, are: (1) wood strand board (WSB), (2) cotton stalk particle board (CPB), and (3) cotton stalk strip board (CSB)

These results suggest that both CSB and CPB panels are more suitable for applications in dry or controlled-moisture environments, as they exhibit increased susceptibility to moisture-induced dimensional changes. To enhance the moisture resistance of cotton-based panels, future research could explore surface treatments or additives such as paraffin or wax. Previous studies have shown that wax significantly reduced 24-h water absorption and thickness swelling in hydrophobic cotton-based panels compared to untreated controls, offering a promising approach for improving dimensional stability [50]. Additionally, exploring the use of alternative adhesives such as polymeric methylene diphenyl diisocyanate (pMDI) may further reduce water absorption and thickness swelling, presenting another viable strategy for enhancing performance in humid conditions.

This study evaluated the structural performance and dimensional stability of panels fabricated from cotton stalk strips, processed using a manual noodle maker. For comparison, panels were also made from cotton stalk particles, representing the most common processing method and wood strand-based panels. The results highlighted that panels fabricated with cotton stalk strips demonstrated structural performance comparable to wood strand-based panels and significantly superior to a cotton stalk particle board. The following key points were identified:

1. Both cotton stalk-based panels exhibited greater internal bond (IB) strength than wood strand board (WSB). The cotton stalk strip board (CSB) achieved the highest IB value, nearly four times that of WSB, primarily due to enhance interaction between PF adhesive and the cotton stalk strips. CPB also outperformed WSB, showing approximately double the IB strength.

2. The maximum normal stress of CSB exceeded that of WSB by 5%. CSB also exhibited bending stiffness comparable to WSB, with only a 15% reduction, highlighting strong potential for cotton stalk strips in flexural applications.

3. Both CSB and CPB absorbed more water than WSB, mainly due to the cotton stalk’s porous, pith-like interior. CPB showed the highest water absorption, while CSB had the greatest thickness swelling, suggesting different responses to moisture between the two cotton-based panels.

4. The parallel alignment of long cotton stalk strips significantly enhanced mechanical performance compared to particle-based panels, highlighting the importance of the processing method.

Our findings demonstrate not only the manufacturing feasibility of cotton stalk strip panels but also their high structural performance. Since their production involves both scrimber and hot-pressing techniques, the product has strong potential for scale-up. Hot-pressing is a well-established method for producing a variety of wood-based products, including medium-density fiberboard (MDF), OSB, and plywood. The scrimber technique, on the other hand, is widely applied in the manufacture of high-strength wood and bamboo scrimber products. However, given that cotton stalk seis a seasonal agricultural residue, comprehensive techno-economic assessments are required to evaluate production costs, raw material availability, supply chain logistics, and market competitiveness.

Overall, these findings support the potential use of waste cotton stalks, especially in strip form, as a sustainable raw material for structural biobased panels. While the mechanical properties of CSB panels are promising, further improvements in dimensional stability are needed. Future research should focus on enhancing dimensional stability by using hydrophobic additives, such as wax or paraffin, and alternative adhesives, like polymeric methylene diphenyl diisocyanate (pMDI). Additional studies are also required to assess toughness, impact resistance, and long-term durability under service conditions, including creep resistance, fatigue behavior, and cyclic exposure to moisture and temperature, to ensure reliable performance in structural applications.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank “Hexion” for the adhesive, “West Fraser” for the wood strands, and “Mississippi State University Farm” for the cotton stalks. We also extend our appreciation to Harrison Ragon (Starkville Academy, Starkville, MS 39759, USA), Richard Sanches (Nanih Waiya Attendance Center, Louisville, MS 39339, USA), and Ian Mayberry (Noxubee County High School, Macon, MS 39341, USA), high school students joining the Department of Sustainable Bioproducts under a summer internship program supported by USDA-NIFA. This research is a contribution of the Forest and Wildlife Research Center, Mississippi State University.

Funding Statement: This research was supported by the intramural research program of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, National Institute of Food and Agriculture, Biobased Economy Through Biobased Products, under Award # 2023-68016-40132.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Aadarsha Lamichhane, Arun Kuttoor Vasudevan, Kevin Ragon and Mostafa Mohammadabadi; methodology, Aadarsha Lamichhane, Arun Kuttoor Vasudevan, Ethan Dean, Kevin Ragon and Mostafa Mohammadabadi; software, Aadarsha Lamichhane, Arun Kuttoor Vasudevan and Mostafa Mohammadabadi; validation, Aadarsha Lamichhane, Arun Kuttoor Vasudevan and Mostafa Mohammadabadi; formal analysis, Aadarsha Lamichhane, Arun Kuttoor Vasudevan and Mostafa Mohammadabadi; investigation, Aadarsha Lamichhane, Arun Kuttoor Vasudevan, Ethan Dean, Kevin Ragon and Mostafa Mohammadabadi; resources, Kevin Ragon, Mostafa Mohammadabadi; data curation, Aadarsha Lamichhane, Arun Kuttoor Vasudevan, Kevin Ragon and Mostafa Mohammadabadi; writing—original draft preparation, Aadarsha Lamichhane; writing—review and editing, Ardeshir Adeli, Kevin Ragon and Mostafa Mohammadabadi; visualization, Aadarsha Lamichhane, Arun Kuttoor Vasudevan and Mostafa Mohammadabadi; supervision, Mostafa Mohammadabadi; project administration, Kevin Ragon and Mostafa Mohammadabadi; funding acquisition, Kevin Ragon and Mostafa Mohammadabadi. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Author, [Mostafa Mohammadabadi], upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Gerland P, Raftery AE, Ševčíková H, Li N, Gu D, Spoorenberg T, et al. World population stabilization unlikely this century. Science. 2014;346(6206):234–7. doi:10.1126/science.1257469. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Sen S, Dasgupta A. Sustainability and agriculture—a futuristic coherent environmental ethical techniques. Strad Res. 2022;9(1):93–103. doi:10.37896/sr9.1/010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Foley JA, Ramankutty N, Brauman KA, Cassidy ES, Gerber JS, Johnston M, et al. Solutions for a cultivated planet. Nature. 2011;478(7369):337–42. doi:10.1038/nature10452. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Townsend T. World natural fibre production and employment. In: Handbook of natural fibres. 2nd ed. Kidlington, UK: Woodhead Publishing; 2020. p. 15–36. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-818398-4.00002-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Yu Z, Yang Y. Carbon footprint of global cotton production. Resour Environ Sustain. 2025;20(1):100214. doi:10.1016/j.resenv.2025.100214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Khan MA, Wahid A, Ahmad M, Tahir MT, Ahmed M, Ahmad S, et al. World cotton production and consumption: an overview. In: Ahmad S, Hasanuzzaman M, editors. Cotton production and uses: agronomy, crop protection, and postharvest technologies. Singapore: Springer; 2020. p. 1–7. doi:10.1007/978-981-15-1472-2_1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Malinga LN. The importance and economic status of cotton production. Acad Lett. 2021. doi:10.20935/al2317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Market data forecast, “cotton market”, market data forecast [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Jun 30]. Available from: https://www.marketdataforecast.com/market-reports/cotton-market. [Google Scholar]

9. Steadman J. USDA report pegs 10.1 million total planted cotton acres for 2025, cotton grower [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Jun 30]. Available from: https://www.cottongrower.com/cotton-production/production-outlook-acreage/usda-report-pegs-10-1-million-total-planted-cotton-acres-for-2025/#:~:text=Cotton%20Companion%20Podcast-,USDA%20Report%20Pegs%2010.1%20Million%20Total%20Planted%20Cotton%20Acres%20for,record%20low%20planted%20cotton%20acres. [Google Scholar]

10. Cai C, Wang Z, Ma L, Xu Z, Yu J, Li F. Cotton stalk valorization towards bio-based materials, chemicals, and biofuels: a review. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2024;202:114651. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2024.114651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Pandirwar AP, Khadatkar A, Mehta CR, Majumdar G, Idapuganti R, Mageshwaran V, et al. Technological advancement in harvesting of cotton stalks to establish sustainable raw material supply chain for industrial applications: a review. Bioenergy Res. 2023;16(2):741–60. doi:10.1007/s12155-022-10520-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Indiana Department of Environmental Management (IDEM). Health risks and environmental impacts of open burning [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Jul 1]. Available from: https://www.in.gov/idem/openburning/health-risks-and-environmental-impacts/. [Google Scholar]

13. ‘More toxic than ever’: Lahore and Delhi choked by smog as ‘pollution season’ begins [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Jun 1]. Available from: https://aqli.epic.uchicago.edu/post/more-toxic-than-ever-lahore-and-delhi-choked-by-smog-as-pollution-season-begins. [Google Scholar]

14. Gu J. The effects of straw burning bans on the use of cooking fuels in China. Energies. 2024;17(24):6355. doi:10.3390/en17246335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Hall JV, Zibtsev SV, Giglio L, Skakun S, Myroniuk V, Zhuravel O, et al. Environmental and political implications of underestimated cropland burning in Ukraine. Environ Res Lett. 2021;16(6):064019. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/abfc04. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Rizal S, HPS AK, Oyekanmi AA, Gideon ON, Abdullah CK, Yahya EB, et al. Cotton wastes functionalized biomaterials from micro to nano: a cleaner approach for a sustainable environmental application. Polymers. 2021;13(7):1006. doi:10.3390/polym13071006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Pradhan S, Lamichhane A, Belaidi D, Mohammadabadi M. The effect of different densification levels on the mechanical properties of southern yellow pine. Sustainability. 2024;16(15):6662. doi:10.3390/su16156662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Lamichhane A, Pradhan S, Belaidi D, Mohammadabadi M. Engineered wood cellular beams: influence of corrugated panels layout on structural performance. Structures. 2025;73(1893):108460. doi:10.1016/j.istruc.2025.108460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Belaidi D, Lamichhane A, Pradhan S, Mohammadabadi M, Shmulsky R, Wang X. Effect of adhesives on bonding performance of softwood and hardwood plywood. For Prod J. 2025;75(1):16–25. doi:10.13073/FPJ-D-24-00044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Hussein Z, Ashour T, Khalil M, Bahnasawy A, Ali S, Hollands J, et al. Rice straw and flax fiber particleboards as a product of agricultural waste: an evaluation of technical properties. Appl Sci. 2019;9(18):3878. doi:10.3390/app9183878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Luo P, Yang C, He Y, Wang T. Development and performance evaluation of rice straw particleboard bonded with chitosan. BioResources. 2025;20(2):4541–8. doi:10.15376/biores.20.2.4541-4548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Luo P, He Y, Wang T. Production of particleboards from steam-pretreated rice straw and castor oil-based polyurethane resin. BioResources. 2025;20(1):852–9. doi:10.15376/biores.20.1.852-859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Ghani A, Norazman AN, Alamjuri RH, Gilbert MS, Hua LS, Palle I. Influence of nanoclay concentration on the performance of the characteristics of particleboard made from rice husk bonded with urea-formaldehyde adhesive. Res Sq. 2025. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-6739489/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Hajihassani R, Salehi K, Golbabaei F, Rahamin H, Mehdinia M. Evaluation of engineering characteristic of particleboard made from rice husk and industrial wood particles. Iran J Wood Pap Sci Res. 2025;40(2):112–23. doi:10.22092/ijwpr.2025.368862.1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Lamichhane A, Kuttoor Vasudevan A, Mohammadabadi M, Ragon K, Street J, Seale RD. From crop residue to corrugated core sandwich panels as a building material. Materials. 2025;18(1):31. doi:10.3390/ma18010031. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Ali M, Alabdulkarem A, Nuhait A, Al-Salem K, Iannace G, Almuzaiqer R, et al. Thermal and acoustic characteristics of novel thermal insulating materials made of Eucalyptus globulus leaves and wheat straw fibers. J Build Eng. 2020;32(3):101452. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2020.101452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Hasanuddin I, Faurantia F, Mawardi I. Fabrication and mechanical characterization of binder-less boards from sugarcane bagasse fibers. J Polimesin. 2025;23(2):147–51. doi:10.30811/jpl.v23i2.6078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Kara ME. Mechanical and physical properties of particleboard produced from hemp plant. BioResources. 2025;20(3). doi:10.15376/biores.20.3.5361-5376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Pepin S, Lawrence M, Blanchet P. Preparation and properties of a rigid hemp shiv insulation particle board using citric acid-glycerol mixture as an eco-friendly binder. BioResources. 2024;19(4):9310–33. doi:10.15376/biores.19.4.9310-9333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Tang TK, Nguyen NQ. Investigation of particleboard production from durian husk and bamboo waste. J Compos Sci. 2025;9(6):276. doi:10.3390/jcs9060276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Chukwu HE, Godwin HC. Lignocellulosic characterisation of thatch grass sourced from southeastern states of nigeria for particleboard manufacturing. UNIZIK J Eng Appl Sci. 2024;3(5):1415–25. [Google Scholar]

32. Matusiak D, Katrusiak A. Herbal-plant residues as potential raw materials source for particle board. J Res Appl Agric Eng. 2024;69(1):36–48. [Google Scholar]

33. Guler C, Ozen R. Some properties of particleboards made from cotton stalks (Gossypium hirsitum L.). Holz Als Roh-Und Werkst. 2024;62(1):40–3. doi:10.1007/s00107-003-0439-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Making good cotton stalk pellets [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Jul 7]. Available from: https://www.wood-pellet-mill.com/solution/cotton-stalk-pellets.html. [Google Scholar]

35. Alma MH, Kalaycıoğlu H, Bektaş I, Tutus A. Properties of cotton carpel-based particleboards. Ind Crops Prod. 2005;22(2):141–9. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2004.08.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Kadja K, Banna M, Atcholi KE, Sanda K. Utilization of bone adhesive to produce particleboards from stems of cotton plant at the pressing temperature of 140°C. Am J Appl Sci. 2011;8(4):318–22. doi:10.3844/ajassp.2011.318.322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Khanjanzadeh H, Bahmani AA, Rafighi A, Tabarsa T. Utilization of bio-waste cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) stalks and underutilized paulownia (paulownia fortunie) in wood-based composite particleboard. Afr J Biotechnol. 2012;11(31):8045–50. doi:10.5897/ajb12.288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Nazerian M, Beygi Z, Mohebbi Gargari R, Kool F. Application of response surface methodology for evaluating particleboard properties made from cotton stalk particles. Wood Mater Sci Eng. 2018;13(2):73–80. doi:10.1080/17480272.2017.1307280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Yasar S, İçel B. Alkali modification of cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) stalks and its effect on properties of produced particleboards. BioResources. 2016;11(3):7191–204. doi:10.15376/biores.11.3.7191-7204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Scatolino MV, Protásio TD, Souza VM, Farrapo CL, Guimarães Junior JB, Soratto D, et al. Does the addition of cotton wastes affect the properties of particleboards? Floresta Ambiente. 2019;26(2):e20170300. doi:10.1590/2179-8087.030017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Nguyen TT. Sustainable formaldehyde-free particleboards from cotton-stalk agricultural waste [dissertation]. Brisbane St Lucia, Australia: The University of Queensland; 2021. [Google Scholar]

42. Chen X, Liu H, Xia N, Shang J, Tran V, Guo K. Preparation and properties of oriented cotton stalk board with konjac glucomannan-chitosan-polyvinyl alcohol blend adhesive. BioResources. 2015;10(2):3736–48. [Google Scholar]

43. Huang Y, Ji Y, Yu W. Development of bamboo scrimber: a literature review. J Wood Sci. 2019;65(1):1–10. doi:10.1186/s10086-019-1806-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Gao Q, Lin Q, Huang Y, Hu J, Yu W. High-performance wood scrimber prepared by a roller-pressing impregnation method. Constr Build Mater. 2023;368:130404. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.130404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Sun X, He M, Liang F, Li Z, Wu L, Sun Y. Experimental investigation into the mechanical properties of scrimber composite for structural applications. Constr Build Mater. 2021;276(5):122234. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.122234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Zhang YH, Ma HX, Qi Y, Zhu RX, Li XW, Yu WJ, et al. Study of the long-term degradation behavior of bamboo scrimber under natural weathering. npj Mater Degrad. 2022;6(1):63. doi:10.1038/s41529-022-00273-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. ASTM D1037-12(2020). Standard test methods for evaluating properties of wood-base fiber and particle panel materials. West Conshohocken, PA, USA: Advancing Standards Transforming Markets; 2020. [Google Scholar]

48. Fašalek A, Konnerth J, van Herwijnen HW, Stroobants J, Pramreiter M. Method for evaluating the bond strength development of pMDI adhesive using ABES. Wood Sci Technol. 2025;59(4):70. doi:10.1007/s00226-025-01670-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Zhao B, Leng Y, Xue M, Xue M, Zhang Q, Dong H, et al. Cure-promoting strategies for phenol-resorcinol-formaldehyde resins: high-ortho catalysis, hydrogen bond activation, and their impact on curing kinetics. J Appl Polym Sci. 2025;142(25):e57047. doi:10.1002/app.57047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Xu X, Yao F, Wu Q, Zhou D. The influence of wax-sizing on dimension stability and mechanical properties of bagasse particleboard. Ind Crops Prod. 2009;29(1):80–5. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2008.04.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools