Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

The role of glutathione peroxidase 4 in the progression, drug resistance, and targeted therapy of non-small cell lung cancer

1 School of Clinical Medicine, Shandong Second Medical University, Weifang, 261000, China

2 Department of Thoracic Surgery, Jinan Central Hospital, Shandong University, Jinan, 250000, China

* Corresponding Author: LIANGMING ZHU. Email:

Oncology Research 2025, 33(4), 863-872. https://doi.org/10.32604/or.2024.054201

Received 21 May 2024; Accepted 26 August 2024; Issue published 19 March 2025

Abstract

Lung cancer is one of the main causes of cancer-related deaths globally, with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) being the most prevalent histological subtype of lung cancer. Glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) is a crucial antioxidant enzyme that plays a role in regulating ferroptosis. It is also involved in a wide variety of biological processes, such as tumor cell growth invasion, migration, and resistance to drugs. This study comprehensively examined the role of GPX4 in NSCLC and investigated the clinical feasibility of targeting GPX4 for NSCLC treatment. We discovered that GPX4 influences the progression of NSCLC by modulating multiple signaling pathways, and that blocking GPX4 can trigger ferroptosis and increase the sensitivity to chemotherapy. As a result, GPX4 represents a prospective therapeutic target for NSCLC. Targeting GPX4 inhibits the development of NSCLC cells and decreases their resistance to treatment.Keywords

Based on the latest relevant literature, as of 2022, lung cancer remains the leading cause of cancer-related fatalities, with an increasing incidence annually. Lung cancer is responsible for the highest number of cancer-related fatalities, and its incidence is increasing annually [1–5]. The non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) histological subtype is the most prevalent, accounting for an estimated 85% of all lung malignancies. In contrast, small cell lung cancer (SCLC) accounts for approximately 15% of the total number of lung cancer cases [3,4,6]. The 5-year survival rate for NSCLC is a mere 23%, and the majority of patients are diagnosed at an advanced stage [7]. The advancement of medicine has brought about significant progress in treating NSCLC, including in the fields of surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and targeted therapy [4,8–10]. However, the prognosis for patients with advanced lung cancer remains unsatisfactory. Therefore, elucidating the mechanisms of NSCLC occurrence and development and identifying new prognostic markers are paramount for clinical diagnosis, treatment, and improved patient prognosis.

The antioxidant enzyme glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4), with a molecular mass of around 20–22 kDa, demonstrates a high level of specificity in its ability to catalyze the conversion of lipid hydroperoxides into corresponding alcohols [11]. Structurally, GPX4 is a monomeric selenoprotein that incorporates selenocysteine at its catalytic site [11]. The genomic organization of the GPX4 gene comprises seven exons and six introns, which encode the mitochondrial (mGPX4), cytosolic (cGPX4), and nuclear (nGPX4) isoforms [12]. These isoforms exhibit specific cellular localizations and functions; mGPX4 and cGPX4 are predominantly involved in cellular protection across various cell types, whereas nGPX4 is implicated in the terminal stages of spermatogenesis [12].

The principal biological function of GPX4 is detoxifying lipid hydroperoxides, thereby preserving the integrity of the cell membrane against oxidative insult [13]. This detoxification is facilitated by using reduced glutathione (GSH) as an electron donor, which is converted to lipid alcohols (PL-OH) from the reactive lipid hydroperoxides (PL-OOH), during which GSH oxidizes to glutathione disulfide (GSSG) [14]. The participation of GPX4 in this antioxidant pathway is crucial in inhibiting ferroptosis, as a reduction in GPX4 activity can result in uncontrolled lipid peroxidation and the consequent initiation of ferroptosis.

GPX4 is essential in the cellular antioxidant defense system [13,15–18]. Other antioxidant enzymes with similar functions to GPX4 include superoxide dismutases (SOD), catalases (CAT), glutathione S-transferases (GST), glutathione reductases (GR), thioredoxin peroxidases (TPx). SOD scavenges harmful superoxide radicals, whereas CAT decomposes hydrogen peroxide into water and oxygen, thereby reducing its toxicity [19]. GST metabolizes glutathione, which aids in the antioxidant defense against peroxides [20]. GR helps to maintain lowered GSH levels within the cell, as GSH serves as a cofactor for GPX4 and other antioxidant enzymes [21]. TPx’s antioxidant activity can maintain cellular redox balance [22]. These antioxidant enzymes collaborate to shield the cell against oxidative harm while also preserving regular physiological functions.

The objective of this study is to investigate the role of GPX4 in NSCLC, with a particular focus on its molecular mechanisms in tumor advancement and resistance to drugs. As a key antioxidant enzyme, GPX4 not only regulates the ferroptosis process but also plays a key role in tumor growth, invasion, and migration. Studying the molecular mechanisms of GPX4 has important clinical value for developing new treatment strategies and improving treatment effects.

Emerging evidence indicates that targeting GPX4 to enhance ferroptosis has potential as a viable therapeutic approach, especially in the field of cancer treatment [23,24]. In light of this, this study presents an overview of GPX4’s biological significance in NSCLC, with an emphasis on its key roles in drug resistance and targeted therapy.

The intracellular antioxidant enzyme GPX4 aids in the elimination of lipid peroxidation products and the mitigation of oxidative stress [25,26]. According to research, GPX4 plays a critical role in ferroptosis regulation [26]. Additionally, GPX4 maintains membrane integrity, participates in tumorigenesis, and induces drug resistance [27–30].

GPX4 plays a crucial role in cellular protection. Its antioxidant activity and cell membrane maintenance are key mechanisms for safeguarding cells against oxidative damage [31,32]. In its role as an antioxidant enzyme, GPX4 mainly aids in the elimination of intracellular lipid peroxides, protecting cells from oxidative stress-induced damage and death, thereby maintaining cell membrane stability and integrity [33–35]. In addition, GPX4 is also essential for maintaining the normal physiological function of red blood cells. Since red blood cells are sensitive to oxygen, GPX4 can reduce oxidative stress by breaking down lipid peroxides to prevent damage to the red blood cell membrane during blood circulation [36–38].

GPX4 is crucial in regulating oxidative stress, maintaining cell membrane stability, and inhibiting ferroptosis, making it a significant therapeutic target for anticancer treatment [24,39,40]. Tumor cells often exist in highly oxidative environments, where the antioxidative effects of GPX4 may contribute to their survival [41]. By suppressing ferroptosis, GPX4 counteracts tumor development and protects tumor cells [38]. GPX4 is crucial in regulating oxidative stress, maintaining cell membrane stability, and inhibiting ferroptosis, making it a significant therapeutic target for anticancer treatment [24,39,40]. Tumor cells usually exist in highly oxidative environments, where the antioxidative effects of GPX4 may contribute to their survival [41]. By suppressing ferroptosis, GPX4 protects tumor cells and contributes to tumor development [38,42]. Also, GPX4 expression levels are significantly correlated with anticancer treatment resistance, according to multiple studies [15,43–46].

Molecular Mechanisms of GPX4 in NSCLC

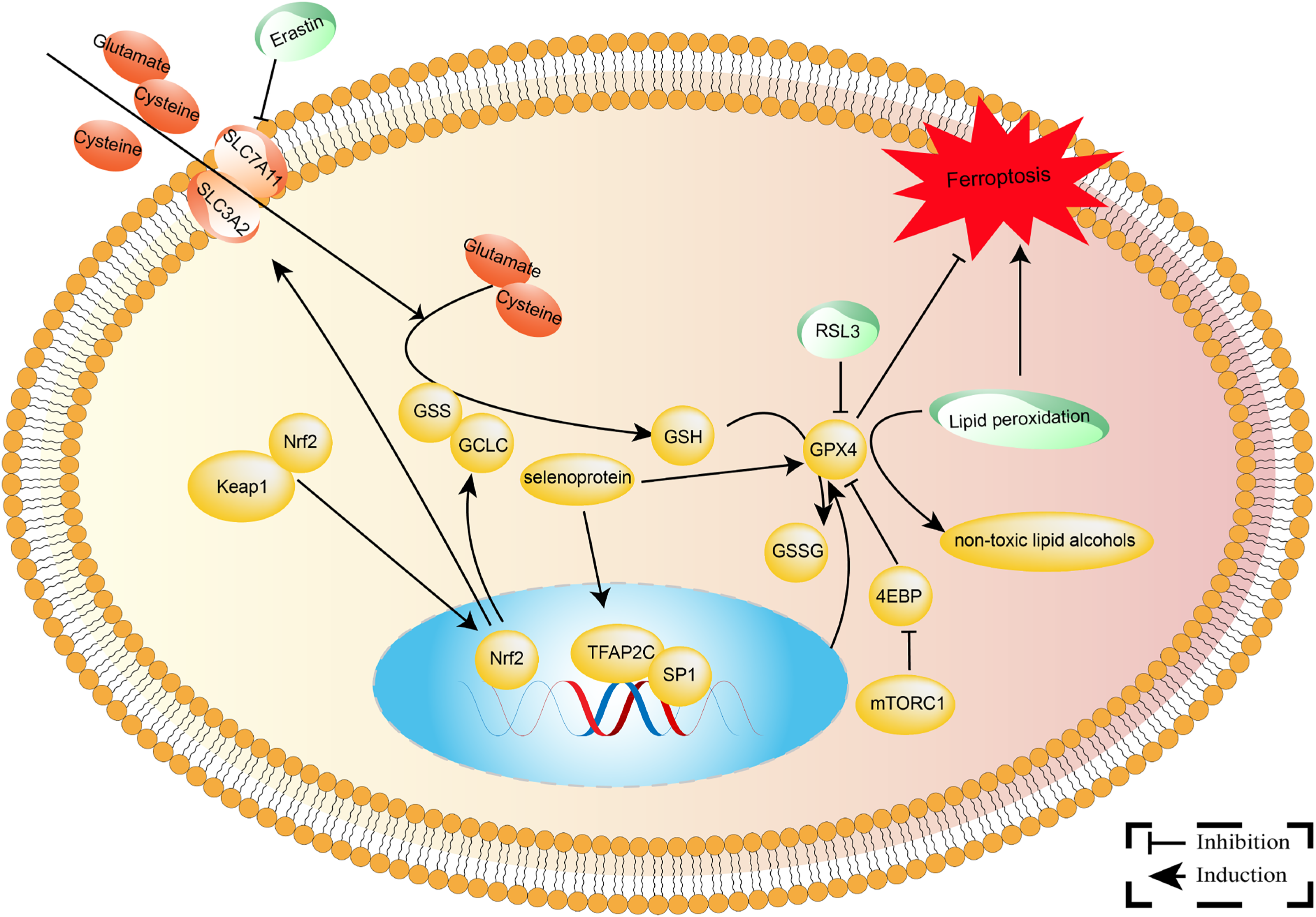

GPX4 eliminates lipid peroxides, safeguarding cell membranes against oxidative damage [47]. It plays pivotal roles in various physiological and pathological processes such as cell death, inflammatory responses, tumorigenesis, and drug resistance [48,49]. The expression of GPX4 is regulated by the AKT/STAT3 and Keap1/Nrf2 signaling pathways [50,51]. The AKT/STAT3 pathway enhances GPX4 stability by upregulating the expression of SLC7A11 [50]. Conversely, the Keap1/Nrf2 pathway downregulates GPX4 expression by inhibiting its transcription [51]. DNA methylation and histone acetylation may regulate GPX4 promoter transcription in cancer tissues. These regulatory mechanisms shed light on the involvement of GPX4 in cellular biology and NSCLC advancement (Fig. 1). Furthermore, activation of antioxidant pathways in NSCLC is regulated both before and after transcription, according to studies [51,52]. For example, activating the Keap1/Nrf2 pathway enhances the transcription of the GPX4 gene [51]. Notably, aberrant activation of antioxidant pathways is critical in the tumor-suppressive microenvironment, allowing tumor cells to elude immune surveillance and resist chemoradiotherapy [32–45].

Figure 1: The molecular mechanisms involved in GPX4 in NSCLC. GPX4 is an essential antioxidant selenoprotein that converts dangerous lipid peroxides into innocuous lipid alcohols, thereby preserving cell membranes from oxidative damage. As an electron donor, Glutathione (GSH) is oxidized to glutathione disulfide (GSSG) and then reduced by glutathione reductase.

GPX4 and Lung Cancer Drug Resistance

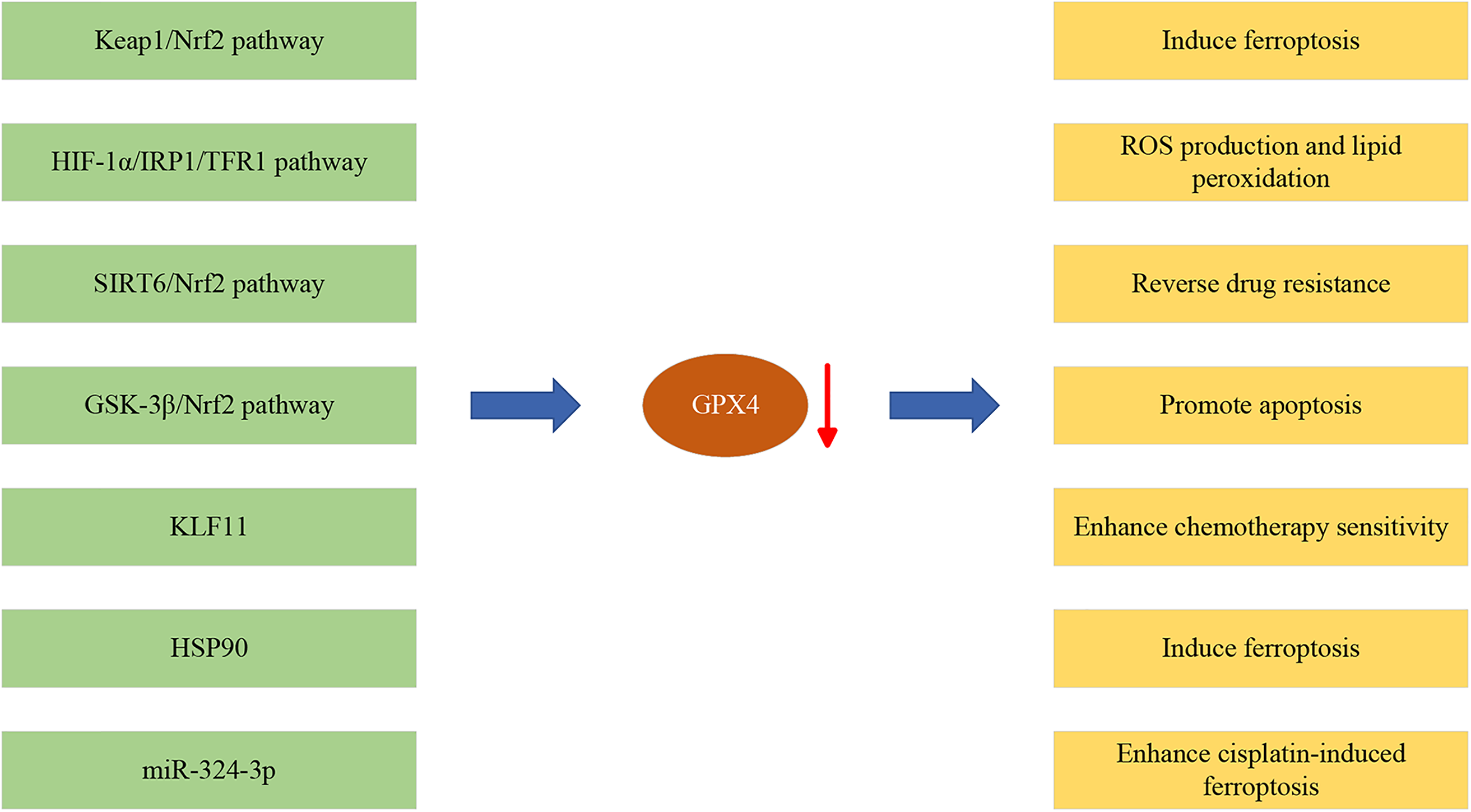

Chemoresistance is one of the primary reasons for disease progression in patients with late-stage lung cancer [53–55]. Effectively inhibiting the resistance of lung cancer cells can significantly prolong patient survival and potentially improve treatment outcomes. Recent research indicates that GPX4 is commonly overexpressed in NSCLC tissues and is closely associated with poor prognosis and chemotherapy sensitivity [30,56,57]. This finding suggests that suppressing GPX4 expression may be a potential strategy to overcome chemotherapy resistance in lung cancer [15,28,58]. A deeper understanding of the molecular mechanisms of lung cancer can help develop therapeutic strategies targeting GPX4 that can become an essential component of personalized treatment, offering novel prospects to enhance treatment efficacy and survival rates for patients with lung cancer (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: The roles of GPX4 in NSCLC development. Red arrow represents downregulation of GPX4 expression.

The expression of GPX4 exhibits a significant positive correlation with resistance to various chemotherapy drugs. Etoposide can induce ferroptosis in NSCLC cells; however, NSCLC cells inhibit ferroptosis by producing lactate through metabolic reprogramming, thus acquiring chemotherapy resistance [59]. Further research has indicated that lactate activates the p38-SGK1 signaling pathway, which thereby inhibits the ubiquitination and degradation of GPX4 by the E3 ubiquitin ligase NEDD4L to enhance GPX4 stability and activity, protecting NSCLC cells from lipid peroxidation damage.

Cisplatin promotes ferroptosis by inducing autophagy [15]. Mechanistically, autophagy can degrade the ferritin heavy chain (FTH1), thereby releasing more Fe2+. The above effects can be reversed by autophagy inhibitors such as 3-methyladenine (3-MA) or deferoxamine (DFO). GPX4 inhibitor RSL3 can enhance the sensitivity of lung cancer cells to cisplatin in vivo and in vitro.

GPX4 has been identified as a downstream target of miR-324-3p [28]. Upregulating miR-324-3p reduces GPX4 expression, making lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) cells more sensitive to cisplatin. Additionally, the expression of GPX4 in LUAD is regulated by the transcription factor KLF11. KLF11 can inhibit GPX4 transcription by directly binding to the GPX4 promoter region, thereby promoting ferroptosis and enhancing chemotherapy sensitivity [60].

GPX4 and targeted therapy resistance

Several studies suggest that targeted therapies for lung cancer, represented by epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors (EGFR-TKIs), can effectively reduce tumor volume and significantly prolong patient survival [61–63]. Following treatment with EGFR-TKIs, the expression of GPX4 is significantly upregulated in LUAD cell lines that have developed resistance [15]. Additional research has demonstrated that EGFR-TKIs and the GPX4 inhibitor RSL3 can decrease the growth of EGFR-TKI-resistant LUAD cells when administered together.

In drug-resistant lung cancer cells, the expression level of Nrf2 is significantly elevated [58,64]. Silencing Nrf2 can reverse epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and decrease migration while increasing the sensitivity of cells to EGFR-TKIs [58]. Mechanistically, Nrf2 upregulates GPX4 and SOD2 expression to suppress reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation and cell death induced by EGFR-TKIs. Lapatinib (Lap) is a dual tyrosine kinase inhibitor that inhibits EGFR and ERBB2 [45]. In Lap-resistant NSCLC cells, the expression of GPX4 is upregulated. Silencing GPX4 can induce ferroptosis and increase NSCLC cells’ susceptibility to Lap. In a nude mouse xenograft model, inhibiting GPX4 inhibits tumor growth and enhances Lap’s anti-tumor activity [45].

Studies reveal that GPX4 plays a significant role in the onset and progression of NSCLC [60,65]. Targeting GPX4 not only inhibits NSCLC cell growth but also effectively overcomes its drug resistance [66]. This finding offers new strategies and directions for NSCLC treatment, highlighting GPX4 as a potential therapeutic target. A deeper understanding of GPX4’s mechanisms in lung cancer can help develop more targeted and efficient treatment modalities in the future, leading to better clinical outcomes and survival rates for patients.

Natural compounds targeting GPX4

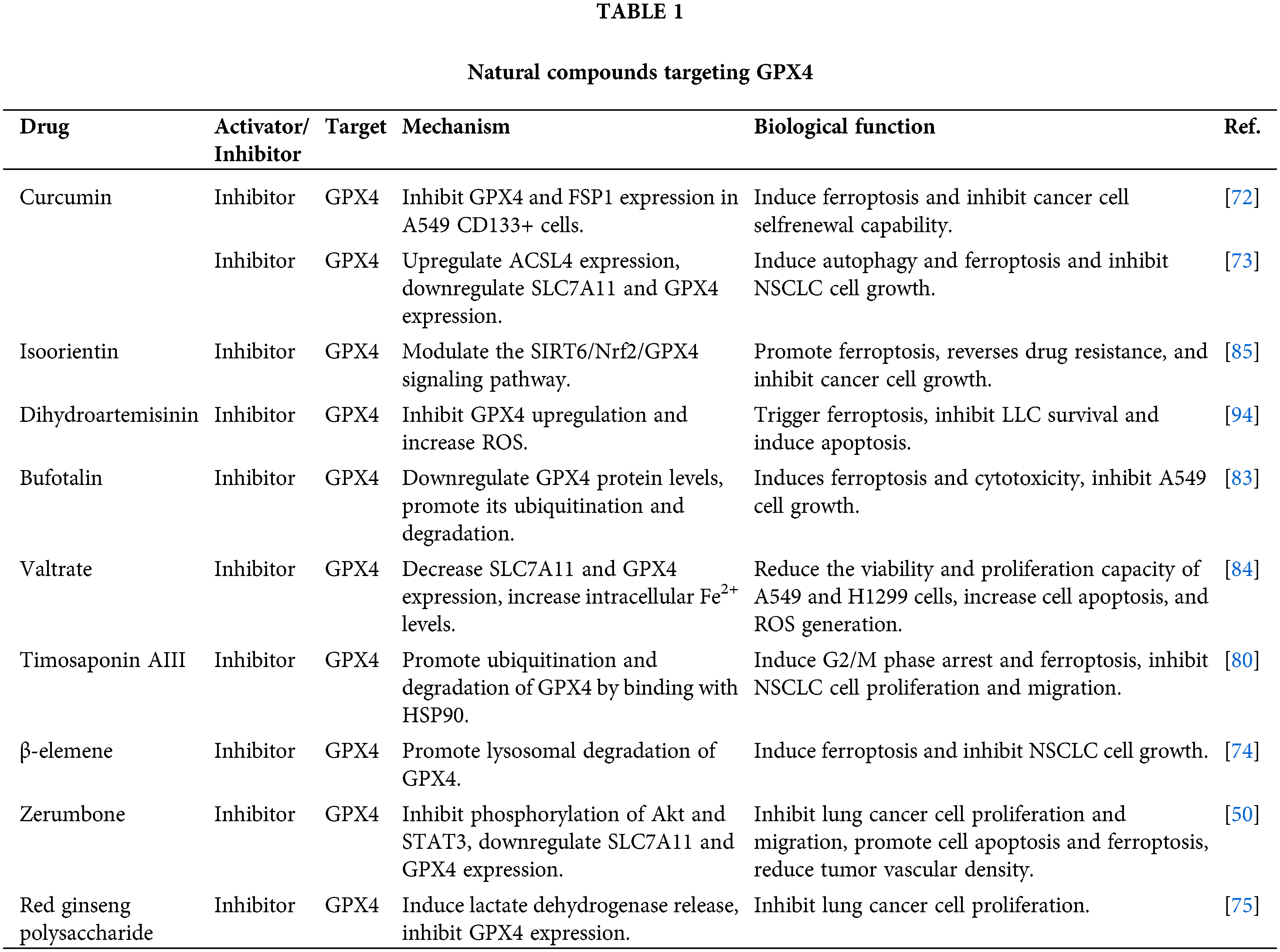

Curcumin is a polyphenolic compound extracted from the turmeric plant that exhibits various biological properties such as anticancer, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant effects [67–71]. Studies have demonstrated that curcumin can reduce the growth and stem cell-like characteristics of lung cancer cells by inducing ferroptosis through the downregulation of GPX4 expression [72,73].

Zerumbone, a natural compound derived from plants in the ginger family, has been discovered to effectively impede the advancement of NSCLC when used in conjunction with gefitinib (an EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor) [50]. Mechanistically, zerumbone and gefitinib can suppress lung cancer growth by inducing ferroptosis through the downregulation of GPX4, thereby enhancing the sensitivity of lung cancer cells to platinum-based chemotherapy drugs [50].

β-elemene (β-ELE), a natural compound obtained from Curcuma wenyujin, demonstrates significant anticancer activity in treating NSCLC [74]. Further research has revealed that β-ELE can significantly increase the expression of TFEB and promote lysosomal degradation of GPX4, leading to ferroptosis. Red ginseng polysaccharide (RGP), a bioactive compound found in the commonly used medicinal plant Panax ginseng C. A. Meyer (Araliaceae), triggers ferroptosis by reducing the expression of GPX4, resulting in anti-tumor activities [75].

Timosaponin AIII (Tim-AIII) is a steroidal saponin extracted from the traditional Chinese medicinal herb Anemarrhena asphodeloides Bunge, known for its significant anticancer activity [76–79]. Tim-AIII has been found to induce ferroptosis, which inhibits the development and lung metastasis of subcutaneous tumour grafts [80].

Bufotalin (BT) is a natural compound isolated from toads that belongs to the bufadienolide class of compounds [81,82]. BT accelerates the degradation of GPX4, elevates intracellular Fe2+ levels, induces ferroptosis and lipid peroxidation, and thereby inhibits the proliferation of NSCLC cells [83].

Researchers found that valtrate (Val) dramatically reduces tumor size and weight in xenograft tumor models by raising cleaved caspase-3 expression and lowering SLC7A11 and GPX4 expression [84]. Feng et al. observed that the combined treatment of isoorientin (IO) and cisplatin markedly reduces the survival rate of drug-resistant lung cancer cells [85]. This effect is accomplished by elevating intracellular Fe2+ levels, lipid peroxides, and ROS while concurrently reducing GSH levels, thus triggering ferroptosis in cells. Mechanistically, IO induces ferroptosis by modulating the SIRT6/Nrf2/GPX4 signaling pathway, thereby reversing drug resistance in lung cancer.

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is a therapeutic modality that utilizes photosensitizers to release ROS under laser irradiation to destroy tumor cells [86,87]. However, PDT may also induce DNA damage and repair responses, upregulating GPX4 expression and degrading ROS, thus inducing resistance in tumor cells to the treatment [88–91]. Dihydroartemisinin (DHA) is a compound extracted from the plant Artemisia annua, possessing anti-malarial and anti-tumor properties [92,93]. Studies indicate that DHA can enhance the release of ROS generated by PDT by inhibiting GPX4 and inducing iron death, thereby improving its cytotoxic effect on lung cancer cells [94].

The Qingrehuoxue formula (QRHXF) significantly inhibits tumor growth, angiogenesis, and EMT while inducing apoptosis and ferroptosis in tumor cells [64]. Mechanistically, QRHXF can regulate the p53 and GSK-3β/Nrf2 signaling pathways, thereby downregulating GPX4 expression and upregulating apoptosis-related markers. Table 1 presents a comprehensive overview of natural compounds that specifically target GPX4.

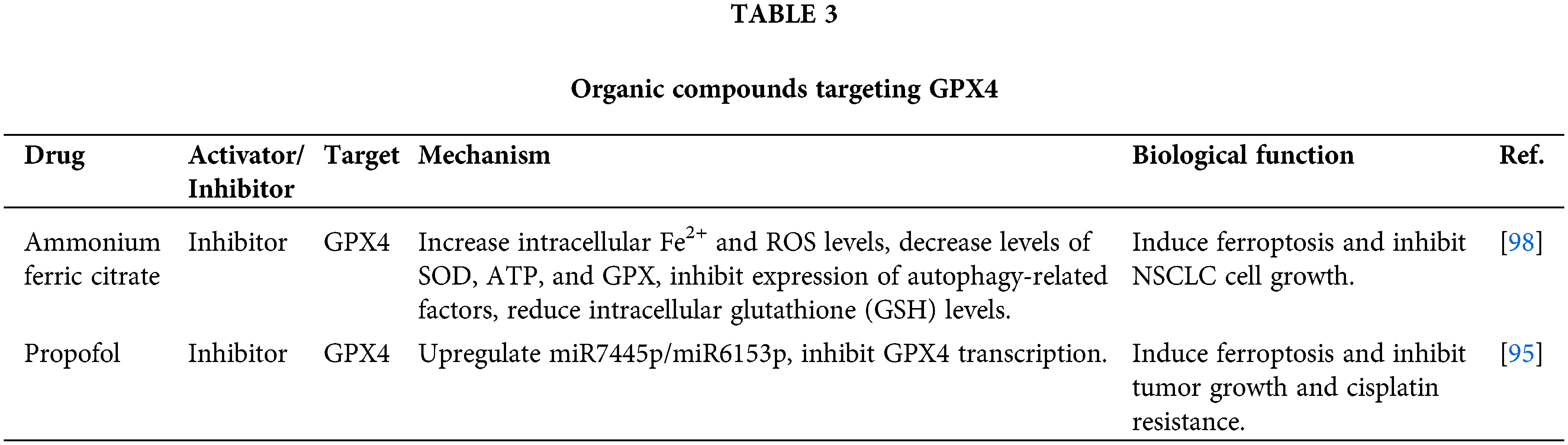

Organic compounds targeting GPX4

Propofol is a widely used intravenous medication for surgical procedures and serves as a neurosystemic anesthetic [95–97]. It exhibits anti-tumor effects in NSCLC by inhibiting cell proliferation and migration while promoting apoptosis. Further investigation revealed that propofol can reduce the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) value of NSCLC cells to cisplatin, thus reversing chemoresistance [95]. Mechanistically, propofol upregulates the expression of miR-744-5p/miR-615-3p, suppressing the transcription of GPX4 and inducing ferroptosis.

Ammonium ferric citrate (AFC) blocks the cell cycle at the G2/M phase and induces apoptosis, inhibiting the proliferation and migration of NSCLC cells [98]. AFC significantly increases intracellular Fe2+ levels and promotes oxidative stress damage, inhibiting autophagy and inducing ferroptosis. Additionally, AFC regulates the GSS/GGT axis, influencing GSH metabolism and ferroptosis. Table 2 presents a comprehensive overview of organic compounds that specifically target GPX4.

Small molecule compounds targeting GPX4

RSL3 is a small molecule inhibitor of GPX4 that exhibits significant anti-tumor effects against NSCLC in vitro and in vivo [99]. RSL3 induces ferroptosis in NSCLC cells by inhibiting GPX4 and regulating the Nrf2/ HO-1 pathway [99]. Further research has revealed that RSL3 disrupts the stability of autophagic flux and lysosomal membranes and increases intracellular levels of Fe2+, lipid peroxides, and ROS while decreasing the GSH levels. Therefore, developing a tumor-specific nanoparticle vector for RSL3, which targets GPX4 in NSCLC, is feasible. These vectors can be engineered with surface modifications incorporating tumor-targeting ligands to facilitate specific binding to NSCLC cells. Concurrently, endowing the nanoparticles with pH-responsive properties to induce drug release within the TME helps minimize off-target effects on healthy cells. Furthermore, optimizing nanoparticle dimensions and morphology is essential to enhance their permeability and accumulation within the tumor mass. Employing these strategies helps augment the therapeutic index of RSL3, potentially leading to a more efficacious treatment regimen for NSCLC.

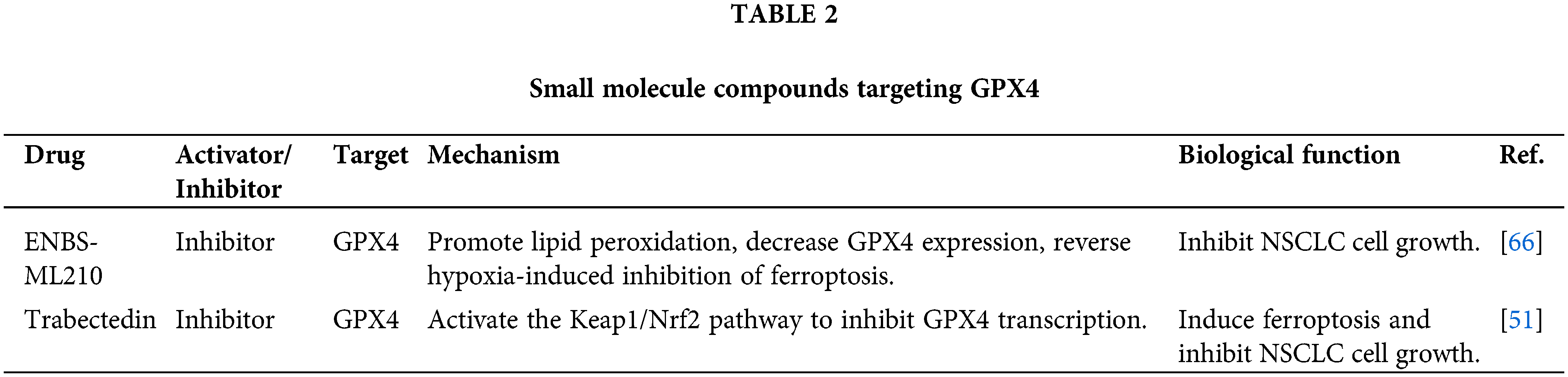

Hu et al. synthesized a compound called ENBS-ML210 by chemically bonding the photosensitizer ENBS with the GPX4 inhibitor ML210 [66]. When exposed to 660 nm irradiation, ENBS-ML210 produces a large amount of O2−, which enhances the process of lipid peroxidation and leads to the degradation of GPX4. In vivo experiments confirmed the efficient accumulation of ENBS-ML210 in tumor tissues, inhibiting tumor growth upon light exposure without observable toxic side effects.

The marine organism Ecteinascidia turbinate is the source of the anticancer drug Trabectedin [51,100,101]. Although Ttrabectedin exhibited no negative effects on normal cells, it was found to greatly inhibit NSCLC development independent of alterations in the tumor suppressor gene p53 [51]. Trabectedin increases Fe2+ levels in NSCLC cells by regulating the HIF1α/IRP1/TFR1 axis, leading to the formation of ROS and lipid peroxidation. Reducing GSH levels in NSCLC cells, Trabectedin downregulates GPX4 expression by activating the Keap1/Nrf2 axis. Table 3 presents a comprehensive overview of small molecule compounds that specifically target GPX4.

However, pharmacological inhibition of GPX4 includes targeted inhibition of enzyme activity and intervention at the transcriptional level [102–104]. To accurately regulate GPX4 expression, the former necessitates the development of small molecule inhibitors that bind to the protein’s active site. In addition, inhibitors of the bromodomain and extra-terminal (BET) protein family can inhibit GPX4 expression by blocking its transcriptional activity [104].

Future Directions and Current Issues of GPX4 in NSCLC

GPX4 protects cells from oxidative stress damage by clearing excess ROS in cells [25]. However, as a core gene in the biological process of ferroptosis, GPX4 overexpression is strongly associated with the advancement of different types of malignancies, such as NSCLC [40,56,58,105–108]. Therefore, future studies can deeply analyze the expression level of GPX4 in different subtypes and stages of NSCLC and explore its specific molecular mechanism. In terms of clinical application, more specific GPX4 inhibitors or activators should be developed and screened, and combined with other anticancer drugs should be considered to optimize the treatment strategy.

The biological significance of GPX4 in NSCLC is clarified in this study, and its overexpression is substantially correlated with a poor prognosis. Inhibiting GPX4 can induce ferroptosis and decrease drug resistance, which provides a novel therapeutic strategy for NSCLC patients. In addition, there were some compounds that showed promise as GPX4 inhibitors, further verification is required to confirm their clinical efficacy.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Liangming Zhu designed the work. Jiaheng Wei wrote the manuscript and prepared the figures and tables. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Leiter, A., Veluswamy, R. R., Wisnivesky, J. P. (2023). The global burden of lung cancer: Current status and future trends. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology, 20(9), 624–639. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41571-023-00798-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Siegel, R. L., Giaquinto, A. N., Jemal, A. (2024). Cancer statistics. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 74(1), 12–49. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.v74.1 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Ma, C., Ma, R. -J., Hu, K., Zheng, Q. -M., Wang, Y. -P. et al. (2022). The molecular mechanism of METTL3 promoting the malignant progression of lung cancer. Cancer Cell International, 22(1), 133. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12935-022-02539-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Ma, C., Hu, K., Ullah, I., Zheng, Q.-K., Zhang, N. et al. (2022). Molecular mechanisms involving the sonic hedgehog pathway in lung cancer therapy: Recent advances. Frontiers in Oncology, 12, 729088. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2022.729088. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Li, C., Lei, S., Ding, L., Xu, Y., Wu, X. et al. (2023). Global burden and trends of lung cancer incidence and mortality. Chinese Medicine Journal (Engl), 136(13), 1583–1590. [Google Scholar]

6. Hu, K., Ma, C., Ma, R., Zheng, Q., Wang, Y. et al. (2022). Roles of Krüppel-like factor 6 splice variant 1 in the development, diagnosis, and possible treatment strategies for non-small cell lung cancer. American Journal of Cancer Research, 12(10), 4468–4482. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

7. Miller, K. D., Nogueira, L., Devasia, T., Mariotto, A. B., Yabroff, K. R. et al. (2022). Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 72(5), 409–436. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.v72.5 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Li, Y., Yan, B., He, S. (2023). Advances and challenges in the treatment of lung cancer. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, 169(21), 115891. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2023.115891. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Yu, Y., Chen, K., Fan, Y. (2023). Extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer: Current management and future directions. International Journal of Cancer, 152(11), 2243–2256. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.v152.11 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Grant, C., Hagopian, G., Nagasaka, M. (2023). Neoadjuvant therapy in non-small cell lung cancer. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology, 190(3), 104080. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2023.104080. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Weaver, K., Skouta, R. (2022). The Selenoprotein Glutathione Peroxidase 4: From Molecular Mechanisms to Novel Therapeutic Opportunities. Biomedicines, 10(4), 891. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines10040891. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Savaskan, N. E., Ufer, C., Kühn, H., Borchert, A. (2007). Molecular biology of glutathione peroxidase 4: From genomic structure to developmental expression and neural function. Biological Chemistry, 388(10), 1007–1017. https://doi.org/10.1515/BC.2007.126. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Lee, J., Roh, J. -L. (2023). Targeting GPX4 in human cancer: Implications of ferroptosis induction for tackling cancer resilience. Cancer Letters, 559, 216119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2023.216119. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Jiang, X., Stockwell, B. R., Conrad, M. (2021). Ferroptosis: Mechanisms, biology and role in disease. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 22(4), 266–282. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41580-020-00324-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Zhang, C., Wang, C., Yang, Z., Bai, Y., Shukuya, T. et al. (2022). Identification of GPX4 as a therapeutic target for lung adenocarcinoma after EGFR-TKI resistance. Translational Lung Cancer Research, 11(5), 786–801. https://doi.org/10.21037/tlcr [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Xie, Y., Kang, R., Klionsky, D. J., Tang, D. (2023). GPX4 in cell death, autophagy, and disease. Autophagy, 19(10), 2621–2638. https://doi.org/10.1080/15548627.2023.2218764. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Xue, Q., Yan, D., Chen, X., Li, X., Kang, R. et al. (2023). Copper-dependent autophagic degradation of GPX4 drives ferroptosis. Autophagy, 19(7), 1982–1996. https://doi.org/10.1080/15548627.2023.2165323. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Liu, Y., Wan, Y., Jiang, Y., Zhang, L., Cheng, W. (2023). GPX4: The hub of lipid oxidation, ferroptosis, disease and treatment. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Reviews on Cancer, 1878(3), 188890. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbcan.2023.188890. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Zhao, H., Zhang, R., Yan, X., Fan, K. (2021). Superoxide dismutase nanozymes: An emerging star for anti-oxidation. Journal of Materials Chemistry B, 9(35), 6939–6957. https://doi.org/10.1039/D1TB00720C. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Dasari, S., Ganjayi, M. S., Yellanurkonda, P., Basha, S., Meriga, B. (2018). Role of glutathione S-transferases in detoxification of a polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon. Chemico-Biological Interactions, 294, 81–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbi.2018.08.023. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Li, F. -J., Long, H. -Z., Zhou, Z. -W., Luo, H. -Y., Xu, S. -G. et al. (2022). System Xc-/GSH/GPX4 axis: An important antioxidant system for the ferroptosis in drug-resistant solid tumor therapy. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 13, 910292. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2022.910292. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Zhang, P., Liu, B., Kang, S. W., Seo, M. S., Rhee, S. G. et al. (1997). Thioredoxin peroxidase is a novel inhibitor of apoptosis with a mechanism distinct from that of Bcl-2. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 272(49), 30615–30618. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.272.49.30615. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Seibt, T. M., Proneth, B., Conrad, M. (2019). Role of GPX4 in ferroptosis and its pharmacological implication. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 133(3), 144–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.09.014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Xu, C., Sun, S., Johnson, T., Qi, R., Zhang, S. et al. (2021). The glutathione peroxidase Gpx4 prevents lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis to sustain Treg cell activation and suppression of antitumor immunity. Cell Reports, 35(11), 109235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109235. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Nishida Xavier, DST., Friedmann Angeli, JP., Ingold, I. (2022). GPX4: Old lessons, new features. Biochemical Society Transactions, 50(3), 1205–1213. https://doi.org/10.1042/BST20220682. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Ma, T., Du, J., Zhang, Y., Wang, Y., Wang, B. et al. (2022). GPX4- independent ferroptosis-a new strategy in disease’s therapy. Cell Death Discovery, 8(1), 434. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41420-022-01212-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Ursini, F., Bosello Travain, V., Cozza, G., Miotto, G., Roveri, A. et al. (2022). A white paper on Phospholipid Hydroperoxide Glutathione Peroxidase (GPx4) forty years later. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 188(2), 117–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2022.06.227. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Deng, S.-H., Wu, D.-M., Li, L., Liu, T., Zhang, T. et al. (2021). miR-324-3p reverses cisplatin resistance by inducing GPX4-mediated ferroptosis in lung adenocarcinoma cell line A549. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 549(10), 54–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2021.02.077. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Pan, X., Lin, Z., Jiang, D., Yu, Y., Yang, D. et al. (2019). Erastin decreases radioresistance of NSCLC cells partially by inducing GPX4-mediated ferroptosis. Oncology Letters, 17(3), 3001–3008. https://doi.org/10.3892/ol.2019.9888. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Chen, H., Peng, F., Xu, J., Wang, G., Zhao, Y. (2023). Increased expression of GPX4 promotes the tumorigenesis of thyroid cancer by inhibiting ferroptosis and predicts poor clinical outcomes. Aging, 15(1), 230–245. https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.204473. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Cui, C., Yang, F., Li, Q. (2022). Post-translational modification of GPX4 is a promising target for treating ferroptosis-related diseases. Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences, 9, 901565. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmolb.2022.901565. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Gong, D., Chen, M., Wang, Y., Shi, J., Hou, Y. (2022). Role of ferroptosis on tumor progression and immunotherapy. Cell Death Discovery, 8(1), 427. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41420-022-01218-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Labrecque, C. L., Fuglestad, B. (2021). Electrostatic drivers of GPx4 interactions with membrane, lipids, and DNA. Biochemistry, 60(37), 2761–2772. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.biochem.1c00492. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Scheerer, P., Borchert, A., Krauss, N., Wessner, H., Gerth, C. et al. (2007). Structural basis for catalytic activity and enzyme polymerization of phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase-4 (GPx4). Biochemistry, 46(31), 9041–9049. https://doi.org/10.1021/bi700840d. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Cozza, G., Rossetto, M., Bosello-Travain, V., Maiorino, M., Roveri, A. et al. (2017). Glutathione peroxidase 4-catalyzed reduction of lipid hydroperoxides in membranes: The polar head of membrane phospholipids binds the enzyme and addresses the fatty acid hydroperoxide group toward the redox center. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 112, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2017.07.010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Müller, T., Dewitz, C., Schmitz, J., Schröder, A. S., Bräsen, J. H. et al. (2017). Necroptosis and ferroptosis are alternative cell death pathways that operate in acute kidney failure. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, 74(19), 3631–3645. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-017-2547-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Ingold, I., Berndt, C., Schmitt, S., Doll, S., Poschmann, G. et al. (2018). Selenium utilization by GPX4 Is required to prevent hydroperoxide-induced ferroptosis. Cell, 172(3), 409–422. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2017.11.048. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Yang, W. S., SriRamaratnam, R., Welsch, M. E., Shimada, K., Skouta, R. et al. (2014). Regulation of ferroptotic cancer cell death by GPX4. Cell, 156(1–2), 317–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Forcina, G. C., Dixon, S. J. (2019). GPX4 at the crossroads of lipid homeostasis and ferroptosis. Proteomics, 19(18), e1800311. https://doi.org/10.1002/pmic.201800311. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Zhao, Y.-Y., Yang, Y.-Q., Sheng, H.-H., Tang, Q., Han, L. et al. (2022). GPX4 Plays a crucial role in Fuzheng Kang’ai decoction- induced non-small cell lung cancer cell ferroptosis. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 13, 851680. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2022.851680. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Doll, S., Freitas, F. P., Shah, R., Aldrovandi, M., da Silva, M. C. et al. (2019). FSP1 is a glutathione-independent ferroptosis suppressor. Nature, 575(7784), 693–698. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1707-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Doll, S., Proneth, B., Tyurina, Y. Y., Panzilius, E., Kobayashi, S. et al. (2017). ACSL4 dictates ferroptosis sensitivity by shaping cellular lipid composition. Nature Chemical Biology, 13(1), 91–98. https://doi.org/10.1038/nchembio.2239. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Lin, X., Zhang, Q., Li, Q., Deng, J., Shen, S. et al. (2023). Upregulation of CoQ shifts ferroptosis dependence from GPX4 to FSP1 in acquired radioresistance. Drug Resistance Updates, 73, 101032. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drup.2023.101032. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Liu, W., Zhou, Y., Duan, W., Song, J., Wei, S. et al. (2021). Glutathione peroxidase 4-dependent glutathione high-consumption drives acquired platinum chemoresistance in lung cancer-derived brain metastasis. Clinical and Translational Medicine, 11(9), e517. https://doi.org/10.1002/ctm2.517. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Ni, J., Chen, K., Zhang, J., Zhang, X. (2021). Inhibition of GPX4 or mTOR overcomes resistance to Lapatinib via promoting ferroptosis in NSCLC cells. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 567, 154–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2021.06.051. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Hangauer, M. J., Viswanathan, V. S., Ryan, M. J., Bole, D., Eaton, J. K. et al. (2017). Drug-tolerant persister cancer cells are vulnerable to GPX4 inhibition. Nature, 551(7679), 247–250. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature24297. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Imai, H., Matsuoka, M., Kumagai, T., Sakamoto, T., Koumura, T. (2017). Lipid peroxidation-dependent cell death regulated by GPx4 and ferroptosis. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology, 403, 143–170. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

48. Luo, M., Yan, J., Hu, X., Li, H., Li, H. et al. (2023). Targeting lipid metabolism for ferroptotic cancer therapy. Apoptosis, 28(1–2), 81–107. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10495-022-01795-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Bebber, C. M., Müller, F., Prieto Clemente, L., Weber, J., von Karstedt, S. (2020). Ferroptosis in cancer cell biology. Cancers, 12(1), 164. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12010164. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Wang, J. -G., Li, D. -L., Fan, R., Yan, M. -J. (2023). Zerumbone combined with gefitinib alleviates lung cancer cell growth through the AKT/STAT3/SLC7A11 axis. Neoplasma, 70(1), 58–70. https://doi.org/10.4149/neo_2022_220418N423. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Cai, S., Ding, Z., Liu, X., Zeng, J. (2023). Trabectedin induces ferroptosis via regulation of HIF-1α/IRP1/TFR1 and Keap1/Nrf2/GPX4 axis in non-small cell lung cancer cells. Chemico-Biological Interactions, 369(1), 110262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbi.2022.110262. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Kolapalli, S. P., Nielsen, T. M., Frankel, L. B. (2023). Post-transcriptional dynamics and RNA homeostasis in autophagy and cancer. Cell Death & Differentiation, 176, 11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41418-023-01201-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Kannampuzha, S., Gopalakrishnan, A. V. (2023). Cancer chemoresistance and its mechanisms: Associated molecular factors and its regulatory role. Medical Oncology, 40(9), 264. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12032-023-02138-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Kryczka, J., Kryczka, J., Czarnecka-Chrebelska, K. H., Brzezia/ska- Lasota, E. (2021). Molecular mechanisms of chemoresistance induced by Cisplatin in NSCLC cancer therapy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(16), 8885. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22168885. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Lv, P., Man, S., Xie, L., Ma, L., Gao, W. (2021). Pathogenesis and therapeutic strategy in platinum resistance lung cancer. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Reviews on Cancer, 1876(1), 188577. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbcan.2021.188577. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Liu, C. -Y., Liu, C. -C., Li, A. F. -Y., Hsu, T. -W., Lin, J. -H. et al. (2022). Glutathione peroxidase 4 expression predicts poor overall survival in patients with resected lung adenocarcinoma. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 20462. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-25019-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Gong, Z., Li, Q., Yang, J., Zhang, P., Sun, W. et al. (2022). Identification of a pyroptosis-related gene signature for predicting the immune status and prognosis in lung adenocarcinoma. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, 10, 852734. https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2022.852734. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Ma, C. -S., Lv, Q. -M., Zhang, K. -R., Tang, Y. -B., Zhang, Y. -F. et al. (2021). NRF2-GPX4/SOD2 axis imparts resistance to EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitors in non-small-cell lung cancer cells. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica, 42(4), 613–623. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41401-020-0443-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Cheng, F., Dou, J., Yang, Y., Sun, S., Chen, R. et al. (2023). Drug- induced lactate confers ferroptosis resistance via p38-SGK1- NEDD4L-dependent upregulation of GPX4 in NSCLC cells. Cell Death Discovery, 9(1), 165. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41420-023-01463-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Zhao, G., Liang, J., Shan, G., Gu, J., Xu, F. et al. (2023). KLF11 regulates lung adenocarcinoma ferroptosis and chemosensitivity by suppressing GPX4. Communications Biology, 6(1), 570. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-023-04959-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Johnson, M., Garassino, M. C., Mok, T., Mitsudomi, T. (2022). Treatment strategies and outcomes for patients with EGFR-mutant non- small cell lung cancer resistant to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors: Focus on novel therapies. Lung Cancer, 170(5), 41–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lungcan.2022.05.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Nie, M., Chen, N., Pang, H., Jiang, T., Jiang, W. et al. (2022). Targeting acetylcholine signaling modulates persistent drug tolerance in EGFR-mutant lung cancer and impedes tumor relapse. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 132(20), e160152. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI160152. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Huang, L. -T., Zhang, S. -L., Han, C. -B., Ma, J. -T. (2022). Impact of EGFR exon 19 deletion subtypes on clinical outcomes in EGFR-TKI- Treated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer, 166(6), 9–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lungcan.2022.01.014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Xu, F., Zhang, J., Ji, L., Cui, W., Cui, J. et al. (2023). Inhibition of non-small cell lung cancer by ferroptosis and apoptosis induction through P53 and GSK-3β/Nrf2 signal pathways using Qingrehuoxue formula. Journal of Cancer, 14(3), 336–349. https://doi.org/10.7150/jca.79465. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Wang, Z., Zhang, X., Tian, X., Yang, Y., Ma, L. et al. (2021). CREB stimulates GPX4 transcription to inhibit ferroptosis in lung adenocarcinoma. Oncology Reports, 45(6), 88. https://doi.org/10.3892/or [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Hu, Q., Zhu, W., Du, J., Ge, H., Zheng, J. et al. (2023). A GPX4- targeted photosensitizer to reverse hypoxia-induced inhibition of ferroptosis for non-small cell lung cancer therapy. Chemical Science, 14(34), 9095–9100. https://doi.org/10.1039/D3SC01597A. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Giordano, A., Tommonaro, G. (2019). Curcumin and cancer. Nutrients, 11(10), 2376. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11102376. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Feng, T., Wei, Y., Lee, R. J., Zhao, L. (2017). Liposomal curcumin and its application in cancer. International Journal of Nanomedicine, 12, 6027–6044. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJN [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Tomeh, M. A., Hadianamrei, R., Zhao, X. (2019). A review of curcumin and its derivatives as anticancer agents. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 20(5), 1033. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20051033. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Wang, W., Li, M., Wang, L., Chen, L., Goh, B. -C. (2023). Curcumin in cancer therapy: Exploring molecular mechanisms and overcoming clinical challenges. Cancer Letters, 570, 216332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2023.216332. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Zhu, J.-Y., Yang, X., Chen, Y., Jiang, Y., Wang, S.-J. et al. (2017). Curcumin suppresses lung cancer stem cells via inhibiting Wnt/β-catenin and sonic hedgehog pathways. Phytotherapy Research, 31(4), 680–688. https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.5791. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Zhou, J., Zhang, L., Yan, J., Hou, A., Sui, W. et al. (2023). Curcumin induces Ferroptosis in A549 CD133+ cells through the GSH- GPX4 and FSP1-CoQ10-NAPH pathways. Discovery Medicine, 35(176), 251–263. https://doi.org/10.24976/Discov.Med.202335176.26. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Tang, X., Ding, H., Liang, M., Chen, X., Yan, Y. et al. (2021). Curcumin induces ferroptosis in non-small-cell lung cancer via activating autophagy. Thoracic Cancer, 12(8), 1219–1230. https://doi.org/10.1111/1759-7714.13904. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Zhao, L.-P., Wang, H.-J., Hu, D., Hu, J.-H., Guan, Z.-R. et al. (2023). β-elemene induced ferroptosis via TFEB-mediated GPX4 degradation in EGFR wide-type non-small cell lung cancer. Journal of Advanced Research, 62(5), 257–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jare.2023.08.018. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Zhai, F. -G., Liang, Q. -C., Wu, Y. -Y., Liu, J. -Q., Liu, J. -W. (2022). Red ginseng polysaccharide exhibits anticancer activity through GPX4 downregulation-induced ferroptosis. Pharmaceutical Biology, 60(1), 909–914. https://doi.org/10.1080/13880209.2022.2066139. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Han, F. -Y., Song, X. -Y., Chen, J. -J., Yao, G. -D., Song, S. -J. (2018). Timosaponin AIII: A novel potential anti-tumor compound from Anemarrhena asphodeloides. Steroids, 140(5), 125–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.steroids.2018.09.014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Liu, Z., Cao, Y., Guo, X., Chen, Z. (2023). The potential role of Timosaponin-AIII in cancer prevention and treatment. Molecules, 28(14), 5500. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28145500. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Song, X. -Y., Han, F. -Y., Chen, J. -J., Wang, W., Zhang, Y. et al. (2019). Timosaponin AIII, a steroidal saponin, exhibits anti-tumor effect on taxol-resistant cells in vitro and in vivo. Steroids, 146, 57–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.steroids.2019.03.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

79. Liu, J., Deng, X., Sun, X., Dong, J., Huang, J. (2020). Inhibition of autophagy enhances timosaponin AIII-induced lung cancer cell apoptosis and anti-tumor effect in vitro and in vivo. Life Sciences, 257(12), 118040. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118040. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Zhou, C., Yu, T., Zhu, R., Lu, J., Ouyang, X. et al. (2023). Timosaponin AIII promotes non-small-cell lung cancer ferroptosis through targeting and facilitating HSP90 mediated GPX4 ubiquitination and degradation. International Journal of Biological Sciences, 19(5), 1471–1489. https://doi.org/10.7150/ijbs.77979. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Dutta, S., Mahalanobish, S., Saha, S., Ghosh, S., Sil, P. C. (2019). Natural products: An upcoming therapeutic approach to cancer. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 128(Suppl. 1), 240–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fct.2019.04.012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

82. Zhang, L., Song, J., Kong, L., Yuan, T., Li, W. et al. (2020). The strategies and techniques of drug discovery from natural products. Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 216(Suppl. 3), 107686. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2020.107686. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

83. Zhang, W., Jiang, B., Liu, Y., Xu, L., Wan, M. (2022). Bufotalin induces ferroptosis in non-small cell lung cancer cells by facilitating the ubiquitination and degradation of GPX4. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 180(11), 75–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2022.01.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

84. Xu, W., Yu, H. (2022). Valtrate antagonizes malignant phenotypes of lung cancer cells by reducing SLC7A11. Human & Experimental Toxicology, 41, 96032712211240. https://doi.org/10.1177/09603271221124096. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

85. Feng, S., Li, Y., Huang, H., Huang, H., Duan, Y. et al. (2023). Isoorientin reverses lung cancer drug resistance by promoting ferroptosis via the SIRT6/Nrf2/GPX4 signaling pathway. European Journal of Pharmacology, 954(3), 175853. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2023.175853. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

86. Li, X., Lee, S., Yoon, J. (2018). Supramolecular photosensitizers rejuvenate photodynamic therapy. Chemical Society Reviews, 47(4), 1174–1188. https://doi.org/10.1039/C7CS00594F. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

87. Huang, H. -C., Mallidi, S., Liu, J., Chiang, C. -T., Mai, Z. et al. (2016). Photodynamic therapy synergizes with irinotecan to overcome compensatory mechanisms and improve treatment outcomes in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Research, 76(5), 1066–1077. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-0391. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

88. Liang, X., Chen, M., Bhattarai, P., Hameed, S., Tang, Y. et al. (2021). Complementing cancer photodynamic therapy with Ferroptosis through iron oxide loaded Porphyrin-grafted lipid nanoparticles. ACS Nano, 15(12), 20164–20180. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.1c08108. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

89. Pan, W. -L., Tan, Y., Meng, W., Huang, N. -H., Zhao, Y. -B. et al. (2022). Microenvironment-driven sequential ferroptosis, photodynamic therapy, and chemotherapy for targeted breast cancer therapy by a cancer-cell-membrane-coated nanoscale metal-organic framework. Biomaterials, 283, 121449. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2022.121449. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

90. Saita, S., Kawasaki, H. (2023). Carbon nanodots with a controlled N structure by a solvothermal method for generation of reactive oxygen species under visible light. Luminescence, 38(2), 127–135. https://doi.org/10.1002/bio.4428. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

91. Zhu, L., You, Y., Zhu, M., Song, Y., Zhang, J. et al. (2022). Ferritin- Hijacking nanoparticles spatiotemporally directing endogenous ferroptosis for synergistic anticancer therapy. Advanced Materials, 34(51), e2207174. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202207174. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

92. Dai, X., Zhang, X., Chen, W., Chen, Y., Zhang, Q. et al. (2021). Dihydroartemisinin: A potential natural anticancer drug. International Journal of Biological Sciences, 17(2), 603–622. https://doi.org/10.7150/ijbs.50364. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

93. Tu, Y. (2016). Artemisinin—A gift from traditional Chinese medicine to the world (Nobel Lecture). Angewandte Chemie International Edition Engl, 55(35), 10210–10226. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.v55.35 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

94. Han, N., Li, L. -G., Peng, X. -C., Ma, Q. -L., Yang, Z. -Y. et al. (2022). Ferroptosis triggered by dihydroartemisinin facilitates chlorin e6 induced photodynamic therapy against lung cancerthrough inhibiting GPX4 and enhancing ROS. European Journal of Pharmacology, 919(4), 174797. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2022.174797. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

95. Han, B., Liu, Y., Zhang, Q., Liang, L. (2023). Propofol decreases cisplatin resistance of non-small cell lung cancer by inducing GPX4- mediated ferroptosis through the miR-744-5p/miR-615-3p axis. Journal of Proteomics, 274, 104777. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jprot.2022.104777. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

96. Sun, Y., Peng, Y. -B., Ye, L. -L., Ma, L. -X., Zou, M. -Y. et al. (2020). Propofol inhibits proliferation and cisplatin resistance in ovarian cancer cells through regulating the microRNA-374a/ forkhead box O1 signaling axis. Molecular Medicine Reports, 21(3), 1471–1480. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

97. Zheng, X., Dong, L., Zhao, S., Li, Q., Liu, D. et al. (2020). Propofol affects non-small-cell lung cancer cell biology by regulating the miR-21/PTEN/AKT pathway in vitro and in vivo. Anesthesia & Analgesia, 131(4), 1270–1280. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000004778. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

98. Wu, W., Geng, Z., Bai, H., Liu, T., Zhang, B. (2021). Ammonium ferric citrate induced ferroptosis in non-small-cell lung carcinoma through the inhibition of GPX4-GSS/GSR-GGT axis activity. International Journal of Medical Sciences, 18(8), 1899–1909. https://doi.org/10.7150/ijms.54860. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

99. Kim, J. -W., Min, D. W., Kim, D., Kim, J., Kim, M. J. et al. (2023). GPX4 overexpressed non-small cell lung cancer cells are sensitive to RSL3-induced ferroptosis. Scientific Reports, 13(1), 8872. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-35978-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

100. Wang, J., Wang, P., Zeng, Z., Lin, C., Lin, Y. et al. (2022). Trabectedin in cancers: Mechanisms and clinical applications. Current Pharmaceutical Design, 28(24), 1949–1965. https://doi.org/10.2174/1381612828666220526125806. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

101. Nakamura, T., Sudo, A. (2022). The role of trabectedin in soft tissue sarcoma. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 13, 777872. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2022.777872. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

102. Li, B., Cheng, K., Wang, T., Peng, X., Xu, P. et al. (2024). Research progress on GPX4 targeted compounds. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, 274, 116548. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmech.2024.116548. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

103. Liu, J., Tang, D., Kang, R. (2024). Targeting GPX4 in ferroptosis and cancer: Chemical strategies and challenges. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences, 45(8), 666–670. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tips.2024.05.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

104. Meng, Y., Sun, H.-Y., He, Y., Zhou, Q., Liu, Y.-H. et al. (2023). BET inhibitors potentiate melanoma ferroptosis and immunotherapy through AKR1C2 inhibition. Military Medical Research, 10(1), 61. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40779-023-00497-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

105. Ding, Y., Chen, X., Liu, C., Ge, W., Wang, Q. et al. (2021). Identification of a small molecule as inducer of ferroptosis and apoptosis through ubiquitination of GPX4 in triple negative breast cancer cells. Journal of Hematology & Oncology, 14(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-020-01016-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

106. Wang, Y., Zheng, L., Shang, W., Yang, Z., Li, T. et al. (2022). Wnt/ beta-catenin signaling confers ferroptosis resistance by targeting GPX4 in gastric cancer. Cell Death & Differentiation, 29(11), 2190–2202. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41418-022-01008-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

107. Shin, D., Kim, E. H., Lee, J., Roh, J.-L. (2018). Nrf2 inhibition reverses resistance to GPX4 inhibitor-induced ferroptosis in head and neck cancer. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 129(5), 454–462. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.10.426. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

108. Chen, P., Lv, X., Zheng, Z. (2023). Gigantol exerts anti-lung cancer activity by inducing ferroptosis via SLC7A11-GPX4 axis. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 690(3), 149274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2023.149274. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools