Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Molecular insights into immune evasion in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas: Toward a promising treatment strategy

1 Department of Pharmacology, School of Dentistry, Kyungpook National University, Daegu, 41940, Republic of Korea

2 Department of Oral Medicine, School of Dentistry, Kyungpook National University, Daegu, 41940, Republic of Korea

3 Brain Science and Engineering Institute, Kyungpook National University, Daegu, 41940, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Authors: JIN-SEOK BYUN. Email: ; DO-YEON KIM. Email:

# Equal contribution

Oncology Research 2025, 33(6), 1271-1282. https://doi.org/10.32604/or.2025.062207

Received 12 December 2024; Accepted 07 April 2025; Issue published 29 May 2025

Abstract

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) is a highly aggressive and devastating disease arising primarily from the mucosal epithelium of the oral cavity, pharynx, and larynx. HNSCC ranks as the sixth most common cancer worldwide, carrying significant morbidity and mortality. HPV-positive HNSCC can be partially prevented with the FDA-approved HPV vaccine and generally exhibits a more favorable prognosis compared to HPV-negative cases. However, effective screening and treatment approaches remain elusive for HPV-negative HNSCC. While precancerous lesions may precede invasive cancer in certain situations, most patients present with advanced disease without prior indication of precancerous conditions. Despite robust immune cell infiltration in HNSCC tumors, the extent and composition of immune infiltration vary widely among patients, and these tumors often evade immune surveillance through diverse mechanisms. Given the heterogeneous nature of HNSCC influenced by anatomical location and etiological factors, precise identification of biomarkers and personalized treatment strategies are imperative. In this study, we aim to explore the possibility of establishing an effective treatment strategy to overcome obstacles to targeted treatment and enable long-term survival through detailed molecular characterization and immune profiling of HNSCC.Keywords

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) is the sixth most common malignancy worldwide and is associated with a poor prognosis [1]. Treatment for HNSCC typically involves a combination of radiation therapy, surgery, and chemotherapy. Despite these aggressive approaches, survival rates remain suboptimal, highlighting the need for innovative treatment strategies. Recently, immune checkpoint inhibitors, particularly anti-PD-1/PD-L1 agents such as nivolumab and pembrolizumab, have shown promise in reactivating the immune system to target and eliminate tumor cells of HNSCC [2,3]. However, anti-PD-1/PD-L1 agents exhibit a low response rate of approximately 20% in HNSCC patients [4]. This limited efficacy is often attributed to complex immunosuppressive mechanisms that enable tumor cells to evade immune surveillance, thereby restricting the effectiveness of immunotherapy [5,6].

Cancer cells create an immunosuppressive microenvironment that impairs both innate and adaptive immune responses, partly through the secretion of immunosuppressive cytokines such as interleukin-10 (IL-10) and transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) [7].

A comprehensive understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying immune evasion is essential to enhance the efficacy of immunotherapy in HNSCC. This study aims to uncover critical pathways that facilitate immune evasion in HNSCC, with the objective of identifying novel therapeutic targets and strategies. Such insights could ultimately pave the way for improving treatment outcomes and patient survival.

Differences between HPV-Positive and HPV-Negative HNSCC

The cancer immune landscape in response to HPV infection

HNSCC can develop as a result of malignant transformation following infection with high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) [1]. Beyond initiating tumorigenesis, HPV infection significantly reconfigures the tumor microenvironment (TME), shaping the cancer immune landscape. Regardless of the location of origin, HPV-positive tumors are characterized by a higher density of immune cells, including B cells, T cells, and natural killer (NK) cells. In contrast, the TME of HPV-negative tumors is predominantly enriched with cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), dendritic cells (DCs), endothelial cells, perivascular cells, and myofibroblasts [8]. This immunologically rich environment in HPV-positive cases correlates with a favorable survival outcome compared to HPV-negative patients [9].

Insight into the immune landscape of HPV-positive and HPV-negative HNSCC patients is important to optimize immunotherapeutic approaches.

In general, the TME contains various immune cells, including regulatory T cells (Tregs), CD8+ T cells, CD4+ T cells, and B cells. Both subtypes are characterized Tregs, but HPV-positive HNSCC are present in lower proportions compared to HPV-negative patients [10]. CD8+ T cells are also observed in both subtypes, their proportion is significantly higher in HPV-positive tumors (27.1% vs. 14.7%) [11]. Macrophage infiltration was found to be higher in HPV-positive HNSCC compared to HPV-negative tumors, with a higher infiltration of M1 subtype macrophages expressing immune activation phenotypes [12]. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) do not differ between the two subtypes, whereas the proportion of functionally intact pDCs is higher in HPV-positive HNSCC [13]. Additionally, natural killer (NK) cells are more abundant in HPV-positive tumors compared to HPV-negative tumors (82% vs. 57%) [14]. In contrast, the predominance of M2 subtype macrophages in HPV-negative tumors promotes tumor progression and correlates with poorer prognosis [15]. In addition, mast cells are extremely abundant in the HPV-negative tumor microenvironment, contributing to immunosuppressive signaling [16]. Tumor-associated neutrophils (TANs) are known to have a higher infiltration rate in HPV-negative HNSCC compared to HPV-positive tumors [17]. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) are significantly distributed in HPV-negative HNSCC, but further studies are necessary to ascertain the proportion of MDSCs in patients with HNSCC based on their HPV status [18].

Potential biomarkers for immune evasion

HPV infection activates the PI3K/MAPK/AKT/mTOR pathway in a variety of ways, contributing to the generally better prognosis for HPV-positive patients compared to HPV-negative patients, largely due to frequent infiltration of Tregs and NK cells [19,20]. While the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway can enhance T cell and NK cell function, excessive activation leads to immune cell exhaustion and suppression, ultimately impairing an effective anti-tumor response [21,22]. Despite these differences, therapeutic strategies for patients with HNSCC remain largely uniform, irrespective of HPV status [23].

In HPV-positive HNSCC, Toll-like receptor (TLR) and T-cell receptor signaling, PD-L1/PD-1 checkpoint activation, and the NF-kappa B (NF-κB) pathway play key roles in modulating the immune environment [24]. In addition, HPV-positive tumors exhibit higher expression of immune checkpoint genes, including cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4 (CTLA4), lymphocyte-activation gene 3 (LAG3), PD1 gene (PDCD1), T-cell immunoglobulin domain and mucin domain-3 (HAVCR2), programmed Cell Death 1 Ligand 2 (PDCD1LG2), and T cell immunoreceptor with immunoglobulin and ITIM domain (TIGIT), which likely contribute to enhanced immune evasion [25].

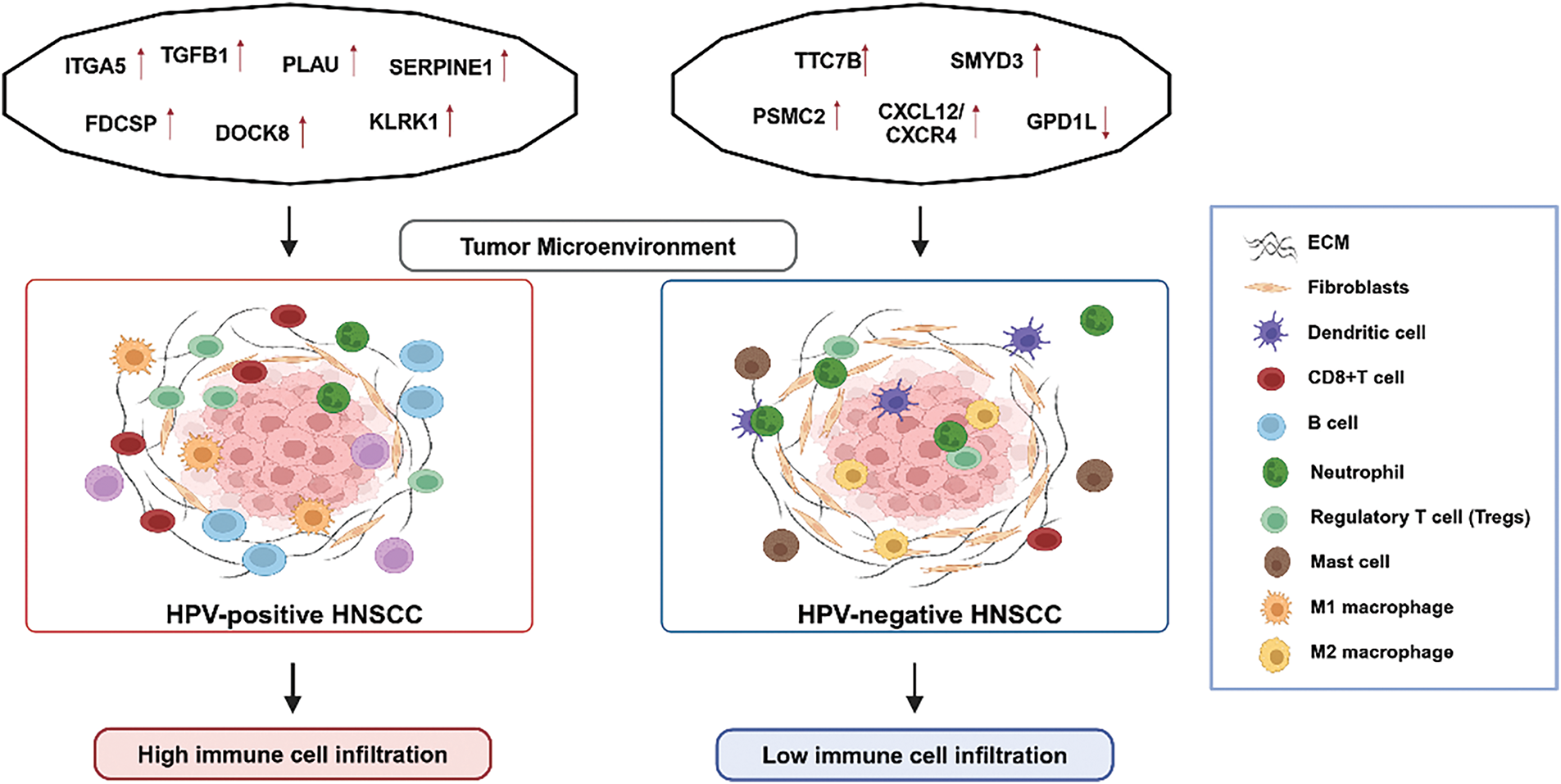

In HPV-positive HNSCC, biomarkers such as Integrin alpha 5 (ITGA5), Transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGFB1), Plasminogen Activator, Urokinase (PLAU), and Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (SERPINE1) are associated with immune cell infiltration and increased radiosensitivity through NF-κB activation [26]. In addition, follicular dendritic cell secretory protein (FDCSP) expression shows positive correlations with B cells, CD4+ memory resting cells, Tregs, and M1 macrophages [27]. Dedicator of Cytokinesis 8 (DOCK8) regulates lymphocyte function by inducing both innate and adaptive immune responses via interleukin-2 (IL-2) and signal transducer and activator of transcription 5 (STAT5) pathways, alleviating immunological tolerance and tumorigenesis [28]. Additionally, Cannabinoid receptor 2 (CNR2), a cannabinoid receptor, disrupts CD8+ T and NK cell activity in the TME [29] and promotes tumor growth through the p38 MAPK pathway, making it a notable marker for HPV-positive HNSCC [30]. Increased expression of killer cell lectin like receptor K1 (KLRK1) in HPV-positive patients promotes the infiltration of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, correlating with improved prognosis. In contrast, tumor-secreted soluble Natural killer group 2D ligands (NKG2DL) and its ligand UL16-binding protein (ULBP) 1-3 induce immune evasion, leading to poorer outcomes [31].

HPV-negative HNSCC is characterized by distinct mechanisms of immune suppression. SET and MYND domain-containing protein 3 (SMYD3) downregulates immune-related genes, including PD-L1 and type I interferons, via the DNA Methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1) pathway, resulting in decreased CD8+ T cell and macrophage infiltration [32,33]. Elevated expression of tetratricopeptide Repeat Domain 7B (TTC7B) is associated with increased macrophage infiltration, disruption of the TME, and poorer patient prognosis, suggesting its role in tumor progression [34]. Furthermore, the proteasome 26S Subunit ATPase 2 (PSMC2) gene is upregulated in HPV-negative HNSCC and promotes migratory proliferation and cell cycle progression through the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway [35–38].

Immune infiltration within tumors is closely linked to lymph node metastasis and prognosis [39,40]. For instance, the CXCL12/CXCR4 axis drives cancer cell migration and lymph node metastasis via the ERK1/2/AP-1 signaling pathway, contributing to increased local recurrence following radiotherapy in HPV-negative cases [41,42]. In addition, the Glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase 1-like (GPD1L) gene exhibits antitumor effects by modulating the hypoxia immune escape mechanism [43]. GPD1L is positively associated with eosinophils and DCs but negatively correlated with Th2 cells, Tregs, and neutrophils, reducing lymph node metastasis and inhibiting tumor spread in HPV-negative HNSCC [44]. These distinct molecular markers underscore the divergent mechanisms driving immune evasion and tumor progression in HPV-positive and HPV-negative HNSCC (Fig. 1). However, further research and validation of these molecular markers are required for their clinical use, and based on this, more precise and personalized treatment strategies can be developed.

Figure 1: A summary of the differences in biomarkers and tumor microenvironment (TME) between HPV-positive and HPV-negative HNSCC. This figure was drawn using BioRender.

Immune Evasion Mechanisms in the Tumor Immune Microenvironment

The TME is a complex and dynamic and multifaceted ecosystem where cancer cells interact with various cellular and molecular components, including CAFs, tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), tissue-associated neutrophils, and MDSCs, creating an immunosuppressive niche that supports tumor growth and immune evasion [45]. Aberrant expression of several genes regulates immune cell infiltration and contributes to cancer progression within the TME. For instance, metabolism-related genes (e.g., SMS, MTHFD2, HPRT1, DNMT1, PYGL, ADA, and P4HA1), Centrosome and spindle pole-associated protein (CSPP1), which is crucial for cytoskeletal organization and cilia formation, and Shc SH2-domain binding protein 1 (SHCBP1), which modulates cancer-related signaling pathways, collectively create an immunosuppressive TME and are linked to poor prognosis [46–49]. Therefore, strategies to modulate the TME by reducing immunosuppression and enhancing immune activation have emerged as promising approaches to improve the efficacy of immunotherapy in HNSCC.

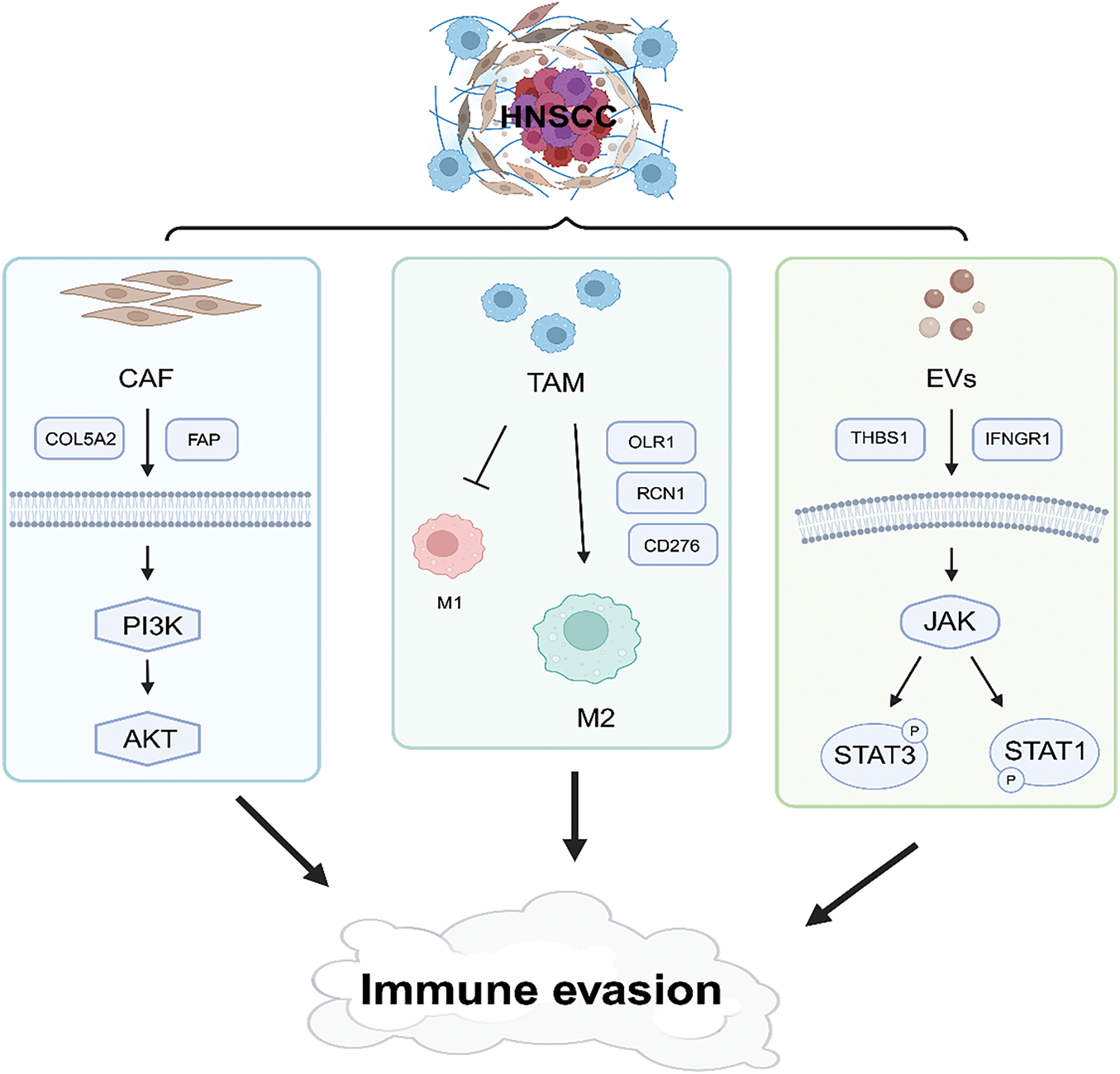

Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs)

CAFs, a major component of the TME, influence intertumoral immune regulation and drug resistance [50]. For example, Collagen type V alpha 2 (COL5A2), secreted by CAFs, activates the PI3K/AKT pathway, leading to resistance against the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitor erlotinib [51]. CAFs from chemoresistant HNSCC patients protect cancer cells by activating PI3K/AKT/p65 signaling, upregulating TGF-α, inducing the EGFR/Src/signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) pathway, and inhibiting apoptosis through the p53/caspase-3 pathway [52]. The PI3K/AKT signaling pathway plays a pivotal role in regulating innate immune cells, such as neutrophils, mast cells, and macrophages, thereby enhancing immune evasion [53,54]. Among the AKT isoforms, AKT3 is particularly critical, as it promotes the immunosuppressive activity of CAFs by inducing M2-like TAMs through the production of cytokines such as IL-6, IL-8, and transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGF-β1) [55]. Additionally, Fibroblast activation protein (FAP), a surface glycoprotein expressed by CAFs, is associated with immune checkpoint molecules (e.g., CTLA4, HAVCR2, and CD276) and contributes to the development and progression of HNSCC via the PI3K-AKT signaling pathway [56,57].

CAFs upregulate the secretion of cytokines, including IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, and TGF-β, from TAMs and promote immune evasion by inducing pro-tumor phenotypic changes in macrophages and neutrophils through the exclusion and depletion of CD8+ T cells [58,59]. Expression of alpha-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), a known marker of CAFs, enables the formation of immunological synapses with Tregs in the tumor stroma, which shows anti-tumorigenic activity [60]. Aortic carboxypeptidase-like protein (ACLP) activates the CAF markers such as actin alpha 2 (ACTA2), FAP, and platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta (PDGFRB) via TGF-β1 signaling, enhancing cancer cell migration and reducing CD8+ T cell infiltration, thereby creating an immunosuppressive TME [61].

Galectins further support tumor progression by promoting cell adhesion, angiogenesis, metabolism, immune escape, and intercellular signaling. Specifically, galectin-1 aids immune evasion by inducing apoptosis in T cells, NK cells, and other immune cells [62–64]. Moreover, high expression of MHC-1 and galectin-9 in CAFs, driven by interferon (IFN) signaling, may limit CD8+ T cell-mediated anti-tumor responses in HNSCC patients [65]. These findings highlight the intricate interplay between CAFs and other TME components in driving immune evasion and tumor progression.

Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs)

In the TME, TAMs are pivotal in suppressing anti-cancer immune responses and facilitating immune evasion [66]. M2-like TAMs, in particular, contribute to maintaining an immunosuppressive microenvironment by inhibiting CD8+ T cells through the expression of T cell immune checkpoint ligands such as PD-L1, and secreting cytokines including CCL-2, IL-6, IL-10, and TGF-β [67]. Consequently, the polarization of TAMs toward the M2 phenotype enhances immune evasion and tumor progression.

Several factors mediate activation of M2-like TAMs. The expression of oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor 1 (OLR1) and cerebral endothelial cell adhesion molecule (CERCAM) facilitates the infiltration of M2-polarized TAMs into the TME. NOD-like receptor pyrin domain-containing protein 3 (NLRP3) also promotes the differentiation of TAMs into the tumor-supportive M2 phenotype, a process linked to cancer progression and poor prognosis [68–70]. Notably, CERCAM, which is also highly expressed in CAFs, is associated with a high rate of M2 macrophage infiltration, with decreased infiltration of CD8+ T cells and activated NK cells [71]. In addition, reticulocalbin (RCN1), a calcium-binding protein located in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) lumen, regulates epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) through the AKT pathway and presumably promotes the formation of M2 TAMs by modulating the expression of markers such as CD206, Arg1, and IL-10 [72].

TAMs are closely linked to chemotherapy resistance in HNSCC. For example, EGFR overexpression upregulates key markers of M2 macrophages, including STAT6, CD163, and MRC1, which negatively affects tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and promotes resistance to cetuximab, an EGFR-specific antibody [73]. Integrin beta 6 (ITGB6), associated with resistance to CD276 antibody therapy, facilitates immune evasion and treatment resistance by recruiting PF4+ TAMs (characterized by expression of platelet factor 4) through the CX3CL1-CX3CR1 axis, resulting in the depletion of cytotoxic CXCR6-positive CD8+ T cells [74]. Furthermore, CD276 is implicated in the migration and differentiation of M2 macrophages via the CCL2-CCR2 axis, further enhancing immune suppression and resistance to therapy [75]. TAM-secreted IL-1β mediates resistance to docetaxel (DTX) in HNSCC by upregulating intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM1), which is influenced by inflammatory cytokines [76].

Extracellular vesicles (EVs), such as exosomes derived from TAMs, function as crucial communication mediators between tumor cells and the TME. EVs not only reflect the molecular content of their parental cells but can also exhibit pro-apoptotic, immunosuppressive, or immunostimulatory properties, depending on their origin [77]. Major proteins found in EVs include CD9, CD63, and ESCRT-related components, which can serve as biomarkers for specific tumor types [78]. Chromatin-modifying protein/charged multivesicular protein (CHMP2A), a subunit of ESCRT-3, facilitates EV production by secreting CXCL10 and CXCL12, which subsequently reduce NK cell migration and inhibit NK cell cytotoxicity [79].

Exosomal thrombospondin 1 (THBS1) influences macrophage polarization toward the M1-like phenotype via p38, AKT, and stress-activated protein kinases (SAPK)/JNK signaling pathways. M1-like TAMs further enhance EMT and cancer stem cells (CSCs) characteristics through activating the Jak/STAT3 pathway [80]. EVs contribute to tumor progression by modulating the TME, increasing inflammatory cytokine levels, and inducing immunosuppression. Specifically, they suppress CD8+ T cell immune responses by downregulating protein tyrosine phosphatase non-receptor type 2 (PTPN2) expression, which accelerates tumor progression [81]. Additionally, cancer cell-derived EVs containing interferon gamma receptor 1 (IFNGR1), enhance PD-L1 expression on lymph node fibroblastic reticular cells (FRCs) through JAK1-STAT1 activation, resulting in CD8+ T cell depletion and potentially promoting lymph node metastasis of HNSCC [82].

Previous studies have demonstrated that tumor-derived EVs remodel the TME under hypoxic conditions, thereby enhancing immune evasion, cancer cell proliferation, and angiogenesis [83,84]. Hypoxia-induced hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha (HIF-1α) accumulation inhibits V-type proton ATPase catalytic subunit A(ATP6V1A) expression, disrupting lysosomal homeostasis and increasing EV release [85]. Hypoxia-driven exosomes exhibit elevated expression of zinc Finger E-Box Binding Homeobox 1 (ZEB1), which induces TAM phenotype switching through STAT3 signaling, thereby amplifying immunosuppressive activity [86]. Moreover, EVs contain abundant microRNAs (miRNAs), including miR-21-5p, which promotes angiogenesis in HNSCC through the HIF-1α pathway [87]. These findings underscore the multifaceted roles of EVs in reshaping the TME, promoting immune evasion, and driving cancer progression and metastasis in HNSCC. Targeting EV-mediated pathways represents a promising avenue for therapeutic intervention in HNSCC (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Schematic illustration of immune evasion in the tumor microenvironment. This figure was drawn using BioRender.

Evasion of Cancer Immune Surveillance

PD-L1 expression can be upregulated by oncogenic transcription factors, such as MYC, AP-1, and STAT, through direct promoter binding or activation of pathways, including MAPK, PTEN/PI3K/AKT, and EGFR. Additionally, DNA double-strand breaks can trigger STAT activation via the ATM/ATR/Chk1 kinase axis, further regulating PD-L1 expression [88–90]. Tumor-associated PD-L1 is primarily induced by tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL)-derived interferon gamma (IFN-γ), which promotes apoptosis and dysfunction of activated T-cells, thereby attenuating the immune response and facilitating tumor growth [91].

High expression of oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor 1 (OLR1) is associated with recruitment of immune cells such as macrophages and cancer-associated fibroblasts. OLR1 activates the PD-1/PD-L1 axis, Toll-like receptor signaling, STAT3 pathway. OLR1 also upregulates the stem cell marker CD44, contributing to immune surveillance evasion and malignant cell proliferation [92]. Similarly, serine hydroxymethyltransferase 2 (SHMT2), highly expressed in HNSCC, inhibits CD8+ T-cell infiltration and promotes immune escape by regulating the MIF/CD44 axis. SHMT2 is associated with poor prognosis and increased PD-L1 expression [93]. Toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9), another key player in immune evasion, upregulates PD-L1 and promotes tumor growth through the PARP1/STAT3 pathway, enhancing tumor cell proliferation, migration, and invasion [94].

In HNSCC, EMT induced by TGF-β signaling mediates immunosuppression and activation of immune checkpoints, such as PD-1, PD-L1, and CTLA-4, particularly in cells with mesenchymal phenotypes. This leads to enhanced tumor growth and metastasis [95]. The PD-1 immune checkpoint interacts with two ligands: PD-L1 and PD-L2. While PD-L1 is primarily induced by IFN-γ, PD-L2 is equally responsive to IFN-β and IFN-γ, regulated by interferon regulatory factor 1 (IRF1) and STAT3 [96]. Notably, glycosylation of PD-L2 by fucosyltransferase 8 (FUT8) stabilizes its expression and enhances EGFR/STAT3 signaling. This glycosylated PD-L2 promotes immune evasion via PD-1 binding, leading to T-cell dysfunction and allowing cancer cells to escape immune surveillance [97]. These mechanisms illustrate the complexity of immune checkpoint pathways in HNSCC, highlighting their critical role in tumor progression and resistance to immune surveillance.

Recent clinical trials targeting these pathways further underscore the ongoing efforts to improve immunotherapy for HNSCC. In a phase II study (NCT03264066) of patients with HNSCC, the combination of cobimetinib (an MEK inhibitor) and atezolizumab (an anti-PD-L1 monoclonal antibody) resulted in a 20% response rate [4]. A randomised phase III study (NCT02369874) in patients with recurrent or metastatic HNSCC reported an objective response rate of 17.9% with durvalumab (anti-PD-L1) and 18.2% with durvalumab plus tremelimumab (anti-CTLA-4) [98]. Another randomised phase III study (NCT02551159) in patients with PD-L1-high HNSCC showed an impressive response rate of 16% for durvalumab alone and 48% for the combination with tremelimumab [99]. Cadonilimab a novel bispecific antibody that targets both PD-1 and CTLA-4, showed an 18.2% response rate in a phase 1b/2 study (NCT03852251), but its efficacy in HNSCC needs further validation [100].

Human leukocyte antigen/major histocompatibility complex (HLA/MHC)

MHC class I downregulation is frequently observed in various tumors and represents a crucial mechanism of immune evasion, as it impairs the recognition and activation of CD8+ cytotoxic T cells [101]. In HNSCC, decreased expression of gamma subunit-4 (GNG4), which is involved in the PI3K/AKT and NF-κB pathways, inhibits the expression of MHC class 1 independently of the IFN-γ signaling, contributing to resistance to PD-1 blockade [102]. In addition, increased expression of HIF1A-AS2, a hypoxia-regulated long non-coding RNA (lncRNA), is associated with elevated HIF-1α levels, leading to enhanced autophagic degradation of MHC class I and reduced CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, ultimately weakening the immune response against tumors [103].

In contrast, HNSCC patients with elevated expression of LINC02195, another lncRNA, exhibit increased expression of MHC class I, which positively correlates with CD8+ and CD4+ T cell infiltration [104]. Targeting Flap endonuclease 1 (FEN1) has been shown to activate the DNA damage response by downregulating STAT1/STAT2, thereby increasing HLA/MHC class I expression and reducing PD-L1 levels. This process overcomes FEN1-mediated immunosuppression, promoting CD8+ T cell-mediated anti-tumor activity through cell cycle arrest and apoptosis of tumor cells [105,106].

Inhibition of fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 (FGFR1) increases the expression of MHC class I and II, improving antigen presentation by increasing human leukocyte antigen (HLA) expression through MAPK pathway inhibition [107]. While most benign tumor cells express HLA, its expression on malignant cells can be induced by interferon and is typically colocalized with T cells within the tumor parenchyma [108]. Conversely, Homeobox B7 (HOXB7) suppresses the IFN-γ/STAT1/class II major histocompatibility complex transactivator (CIITA) axis and downregulates HLA class II expression through the MAPK pathway, thereby facilitating immune evasion [109]. CD3D, a component of the T-cell receptor (TCR)/CD3 complex, has demonstrated a better response to immunotherapy in HNSCC patients. Its upregulation is associated with increased immune cell infiltration, elevated expression of HLA-related genes, and enhanced activation of the JAK/STAT signaling pathway, highlighting its potential as a therapeutic target to bolster immune-mediated tumor clearance [110].

Molecular approaches to immune evasion in tumors

IFN-γ plays a critical role in T cell-mediated antitumor immune responses by modulating tumor-killing activity and thereby influencing tumor immune evasion [111]. IFN-γ-induced SP140 expression in tumors inhibits STAT1 while promoting infiltration of M1 macrophages and CD8+ T cells [112]. Although STAT1 functions as a tumor suppressor, its activation in TAMs upregulates inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and arginase 1, resulting in T cell suppression [113]. Interestingly, deficiency of the N6-methyladenosine (m6A) reader YTH N6-methyladenosine RNA binding protein 2(YTHDF2) reprograms TAMs into an antitumor phenotype by targeting the IFN-γ/STAT1 signaling axis, thereby enhancing CD8+ T cell-mediated immunity [114].

While immunomodulatory strategies typically focus on bolstering tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cell activity, CD4+ T cells also significantly influence the TME by secreting cytokines that enhance CD8+ T cell infiltration [115]. In HPV-positive tumor cells, induction of CXCL13 in CD4+ T cells lead to increased secretion of IFN-γ, which contributes to elevated tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) counts and improved immune cell infiltration, thereby enhancing the prognosis of HNSCC patients [116,117]. Increased CXCL13 levels also facilitate B cell recruitment and drive the formation of tertiary lymphoid structures (TLS) [116,118]. Unlike encapsulated secondary lymphoid organs (SLOs), TLSs allow free movement of immune cells, enabling localized T cell recognition of tumor-associated antigens with the assistance of B cells, thereby intensifying the local immune responses at the site of TLS formation [119].

The membrane-bound glycoprotein semaphorin-4A (SEMA4A), crucial for T cell co-stimulation and a key driver of Th 2 responses, plays an important role in generating immune aggregates through interactions between tumor-infiltrating B cells (TIL-Bs), endothelial cells, and T cells [120]. In HNSCC, IL17A expression, which is implicated in TLS formation, is positively correlated with increased infiltration of T and B cells, suggesting its critical role in immune regulation [121].

Toll-like receptors (TLRs), key pattern recognition receptors in the innate immune response, are expressed on a range of immune cells, including TAMs [122]. TLR10, by competing with other costimulatory TLRs, activates the PI3K/AKT to produce IL-1Ra, a tumor suppressor [123]. Expression of TLR10 is also linked to early B cell development. Activation of the TLR4 pathway generates reactive oxygen species (ROS) and drives NF-κB nuclear translocation in neutrophils [124]. Dual inhibition of interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinases (IRAK-4 and IRAK-1), downstream mediators of TLR signaling, suppresses the expression of anti-apoptotic proteins such as Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL in chemoresistant HNSCC. This inhibition also reduces the secretion of the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-6, mitigating its role in shaping an immunosuppressive TME [125].

Latest immunotherapies and research trends for HNSCC treatment

Recent clinical trials and studies suggest that immune checkpoint inhibitors, including nivolumab (anti-PD-1) and ipilimumab (anti-CTLA-4), demonstrate potential in overcoming immune evasion in HNSCC (NCT02741570) [126]. Furthermore, the combination of the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR) inhibitor apatinib and the anti-PD-1 antibody camrelizumab has demonstrated a pathological response rate of approximately 40%, underlining the potential of immunomodulatory treatments (NCT04393506) [127]. Other novel immunotherapeutic strategies include the combination of cetuximab with a TLR8 agonist, which enhances anti-tumor immune responses by regulating the TIGIT signaling pathway (NCT02124850) [128]. Furthermore, urelumab, a CD137 agonist, has demonstrated the capacity to activate immune-related pathways when combined with nivolumab, suggesting the potential to enhance immune responses in HNSCC (NCT02253992) [129].

The dysregulation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in tumor cells plays a pivotal role in immune evasion and tumor progression, leading to immune cell exhaustion and suppression [21,130]. In response to this, ongoing clinical trials are evaluating the PI3K inhibitor buparlisib (NCT01527877), with studies investigating its combination with cetuximab to enhance treatment efficacy in recurrent and metastatic HNSCC [131]. Additionally, emerging strategies targeting immune checkpoint molecules offer new therapeutic potential. The combination of eftilagimod alpha (a soluble LAG3 protein) and pembrolizumab has demonstrated tumor regression and immune activation, particularly in tumors with poor T-cell infiltration (NCT03625323) [132].

Meanwhile, BL-B01D1, a bispecific antibody-drug conjugate targeting EGFR and HER3, has exhibited an objective response rate of approximately 34% in a phase 1 clinical trial for HNSCC (NCT05194982) [133]. In addition, nintedanib is currently being evaluated in a phase 2 trial for patients with FGFR mutations (NCT03292250) [134]. These advancements underscore the continuous progress in HNSCC treatment and the growing potential of combination immunotherapies.

The intricate interplay between molecular mechanisms, the TME, and immune evasion underscores the challenges in effectively treating HNSCC. HPV status significantly influences the immune landscape and prognosis. The distinct immune evasion strategies employed by HPV-positive and HPV-negative tumors highlight the critical need for personalized therapeutic approaches tailored to the specific characteristics of each tumor type. Recent advances in the understanding of biomarkers, tumor-associated immune cells, and molecular pathways have facilitated the identification of potential targets to counteract immunosuppression and enhance the efficacy of immunotherapy. Leveraging these insights in future research and clinical strategies holds promise for reshaping the treatment paradigm, offering improved outcomes and prolonged survival for patients with HNSCC.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (Nos. 2022R1C1C1006181, RS-2023-00208416).

Author Contributions: Hyeon Ji Kim and Bo Kyung Joo: Conceptualization, investigation, writing—original draft. Jin-Seok Byun and Do-Yeon Kim: Conceptualization, investigation, review, editing, finalizing, and supervision. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Johnson DE, Burtness B, Leemans CR, Lui VWY, Bauman JE, Grandis JR. Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020;6(1):92. doi:10.1038/s41572-020-00224-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Harrington KJ, Burtness B, Greil R, Soulières D, Tahara M, et al. Pembrolizumab with or without chemotherapy in recurrent or metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: updated results of the phase III KEYNOTE-048 study. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(4):790–802. doi:10.1200/JCO.21.02508. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Serafini MS, Cavalieri S, Licitra L, Pistore F, Lenoci D, Canevari S, et al. Association of a gene-expression subtype to outcome and treatment response in patients with recurrent/metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma treated with nivolumab. J Immunother Cancer. 2024;12(1):e007823. doi:10.1136/jitc-2023-007823. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Sherman E, Lee JL, Debruyne PR, Keam B, Shin SJ, Gramza A, et al. Safety and efficacy of cobimetinib plus atezolizumab in patients with solid tumors: a phase II, open-label, multicenter, multicohort study. ESMO Open. 2023;8(2):100877. doi:10.1016/j.esmoop.2023.100877. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Vinay DS, Ryan EP, Pawelec G, Talib WH, Stagg J, Elkord E, et al. Immune evasion in cancer: mechanistic basis and therapeutic strategies. Semin Cancer Biol. 2015;35:S185–98. doi:10.1016/j.semcancer.2015.03.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Dutta S, Ganguly A, Chatterjee K, Spada S, Mukherjee S. Targets of immune escape mechanisms in cancer: basis for development and evolution of cancer immune checkpoint inhibitors. Biology. 2023;12(2):218. doi:10.3390/biology12020218. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Liu C, Wang M, Zhang H, Li C, Zhang T, Liu H, et al. Tumor microenvironment and immunotherapy of oral cancer. Eur J Med Res. 2022;27(1):198. doi:10.1186/s40001-022-00835-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Lee H, Park S, Yun JH, Seo C, Ahn JM, Cha HY, et al. Deciphering head and neck cancer microenvironment: single-cell and spatial transcriptomics reveals human papillomavirus-associated differences. J Med Virol. 2024;96(1):e29386. doi:10.1002/jmv.29386. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Ruffin AT, Li H, Vujanovic L, Zandberg DP, Ferris RL, Bruno TC. Improving head and neck cancer therapies by immunomodulation of the tumour microenvironment. Nat Rev Cancer. 2023;23(3):173–88. doi:10.1038/s41568-022-00531-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Hur JY, Ku BM, Park S, Jung HA, Lee SH, Ahn MJ. Prognostic value of FOXP3+ regulatory T cells for patients with locally advanced oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. PLoS One. 2022;17(10):e0274830. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0274830. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Landin D, Ährlund-Richter A, Mirzaie L, Mints M, Näsman A, Kolev A, et al. Immune related proteins and tumor infiltrating CD8+ lymphocytes in hypopharyngeal cancer in relation to human papillomavirus (HPV) and clinical outcome. Head Neck. 2020;42(11):3206–17. doi:10.1002/hed.26364. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Chen X, Fu E, Lou H, Mao X, Yan B, Tong F, et al. IL-6 induced M1 type macrophage polarization increases radiosensitivity in HPV positive head and neck cancer. Cancer Lett. 2019;456:69–79. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2019.04.032. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Koucký V, Hladíková K, Táborská E, Bouček J, Grega M, Špíšek R, et al. The cytokine milieu compromises functional capacity of tumor-infiltrating plasmacytoid dendritic cells in HPV-negative but not in HPV-positive HNSCC. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2021;70(9):2545–57. doi:10.1007/s00262-021-02874-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Wagner S, Wittekindt C, Reuschenbach M, Hennig B, Thevarajah M, Würdemann N, et al. CD56-positive lymphocyte infiltration in relation to human papillomavirus association and prognostic significance in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2016;138(9):2263–73. doi:10.1002/ijc.29962. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Fu E, Liu T, Yu S, Chen X, Song L, Lou H, et al. M2 macrophages reduce the radiosensitivity of head and neck cancer by releasing HB-EGF. Oncol Rep. 2020;44(2):698–710. doi:10.3892/or.2020.7628. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Wang Z, Wang Q, Tao Y, Chen J, Yuan Z, Wang P. Characterization of immune microenvironment in patients with HPV-positive and negative head and neck cancer. Sci Data. 2023;10(1):694. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

17. Martínez-Barajas MG, Jave-Suárez LF, Ramírez-López IG, García-Chagollán M, Zepeda-Nuño JS, Ramírez-de-Arellano A, et al. HPV-negative and HPV-positive oral cancer cells stimulate the polarization of neutrophils towards different functional phenotypes in vitro. Cancers. 2023;15(24):5814. doi:10.3390/cancers15245814. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Fialová A, Koucký V, Hajdušková M, Hladíková K, Špíšek R. Immunological network in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma-a prognostic tool beyond HPV status. Front Oncol. 2020;10:1701. doi:10.3389/fonc.2020.01701. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Sun Y, Wang Z, Qiu S, Wang R. Therapeutic strategies of different HPV status in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Biol Sci. 2021;17(4):1104–18. doi:10.7150/ijbs.58077. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Zeng PYF, Cecchini MJ, Barrett JW, Shammas-Toma M, De Cecco L, Serafini MS, et al. Immune-based classification of HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancer with implications for biomarker-driven treatment de-intensification. EBioMedicine. 2022;86:104373. doi:10.1016/j.ebiom.2022.104373. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Liao J, Yang Z, Azarbarzin S, Cullen KJ, Dan H. Differential modulation of PI3K/Akt/mTOR activity by EGFR inhibitors: a rationale for co-targeting EGFR and PI3K in cisplatin-resistant HNSCC. Head Neck. 2024;46(5):1126–35. doi:10.1002/hed.27718. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Collins NB, Al Abosy R, Miller BC, Bi K, Zhao Q, Quigley M, et al. PI3K activation allows immune evasion by promoting an inhibitory myeloid tumor microenvironment. J Immunother Cancer. 2022;10(3):e003402. doi:10.1136/jitc-2021-003402. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Ghiani L, Chiocca S. High risk-human papillomavirus in HNSCC: present and future challenges for epigenetic therapies. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(7):3483. doi:10.3390/ijms23073483. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Zhou D, Wang J, Wang J, Liu X. Profiles of immune cell infiltration and immune-related genes in the tumor microenvironment of HNSCC with or without HPV infection. Am J Transl Res. 2021;13(4):2163–80. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

25. Meng L, Lu H, Li Y, Zhao J, He S, Wang Z, et al. Human papillomavirus infection can alter the level of tumour stemness and T cell infiltration in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Front Immunol. 2022;13:1013542. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.1013542. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Schrank TP, Kothari A, Weir WH, Stepp WH, Rehmani H, Liu X, et al. Noncanonical HPV carcinogenesis drives radiosensitization of head and neck tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2023;120(32):e2216532120. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

27. Wu Q, Shao T, Huang G, Zheng Z, Jiang Y, Zeng W, et al. FDCSP is an immune-associated prognostic biomarker in HPV-positive head and neck squamous carcinoma. Biomolecules. 2022;12(10):1458. doi:10.3390/biom12101458. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Zhang Z, Bao Y, Zhou L, Ye Y, Fu W, Sun C. DOCK8 Serves as a prognostic biomarker and is related to immune infiltration in patients with HPV positive head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Control. 2021;28:10732748211011951. doi:10.1177/10732748211011951. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Sarsembayeva A, Kienzl M, Gruden E, Ristic D, Maitz K, Valadez-Cosmes P, et al. Cannabinoid receptor 2 plays a pro-tumorigenic role in non-small cell lung cancer by limiting anti-tumor activity of CD8+ T and NK cells. Front Immunol. 2022;13:997115. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

30. Liu C, Sadat SH, Ebisumoto K, Sakai A, Panuganti BA, Ren S, et al. Cannabinoids promote progression of HPV-positive head and neck squamous cell carcinoma via p38 MAPK activation. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26(11):2693–703. doi:10.1158/1078-0432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Tan H, Yang H, Qian J, Liu S, Yan D, Wei L, et al. Involvement of KLRK1 in immune infiltration of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma correlates with favorable prognosis. Medicine. 2023;102(32):e34761. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000034761. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Nigam N, Bernard B, Sevilla S, Kim S, Dar MS, Tsai D, et al. SMYD3 represses tumor-intrinsic interferon response in HPV-negative squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Cell Rep. 2023;42(7):112823. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2023.112823. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Tsai DE, Lovanov A, Abdelmaksoud A, Akhtar J, Dar MS, Luff M, et al. Smyd3-mediated immuno-modulation in HPV-negative head and neck squamous cell carcinoma mouse models. iScience. 2024;27(9):110854. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2024.110854. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. He R, Zhang X, Wu Y, Weng Z, Li L. TTC7B is a new prognostic biomarker in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma linked to immune infiltration and ferroptosis. Cancer Med. 2023;12(24):22354–69. doi:10.1002/cam4.6715. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Su Y, Zeng Z, Rong D, Yang Y, Wu B, Cao Y. PSMC2, ORC5 and KRTDAP are specific biomarkers for HPV‑negative head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oncol Lett. 2021;21(4):289. doi:10.3892/ol.2021.12550. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Wang Y, Zhang S, Zhao Z, Jin Q, Wang Z, Song Z, et al. PSMC2 promotes glioma progression by regulating immune microenvironment and PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. Immunobiology. 2024;229(3):152802. doi:10.1016/j.imbio.2024.152802. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Wang Z, Xiong H, Zuo Y, Hu S, Zhu C, Min A. PSMC2 knockdown inhibits the progression of oral squamous cell carcinoma by promoting apoptosis via PI3K/Akt pathway. Cell Cycle. 2022;21(5):477–88. doi:10.1080/15384101.2021.2021722. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Liu Y, Chen H, Li X, Zhang F, Kong L, Wang X, et al. PSMC2 regulates cell cycle progression through the p21/Cyclin D1 pathway and predicts a poor prognosis in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Oncol. 2021;11:607021. doi:10.3389/fonc.2021.607021. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Meng F, Hua S, Chen X, Meng N, Lan T. Lymph node metastasis related gene BICC1 promotes tumor progression by promoting EMT and immune infiltration in pancreatic cancer. BMC Med Genomics. 2023;16(1):263. doi:10.1186/s12920-023-01696-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Jin R, Luo Z, Jun L, Tao Q, Wang P, Cai X, et al. USP20 is a predictor of poor prognosis in colorectal cancer and associated with lymph node metastasis, immune infiltration and chemotherapy resistance. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1023292. doi:10.3389/fonc.2023.1023292. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Tan CT, Chu CY, Lu YC, Chang CC, Lin BR, Wu HH, et al. CXCL12/CXCR4 promotes laryngeal and hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma metastasis through MMP-13-dependent invasion via the ERK1/2/AP-1 pathway. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29(8):1519–27. doi:10.1093/carcin/bgn108. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. De-Colle C, Menegakis A, Mönnich D, Welz S, Boeke S, Sipos B, et al. SDF-1/CXCR4 expression is an independent negative prognostic biomarker in patients with head and neck cancer after primary radiochemotherapy. Radiother Oncol. 2018;126(1):125–31. doi:10.1016/j.radonc.2017.10.008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Liu H, Wang S, Cheng A, Han Z, Feng Z, Guo C. GPD1L is negatively associated with HIF1α expression and predicts lymph node metastasis in oral and HPV-Oropharyngeal cancer. Oral Dis. 2021;27(7):1654–66. doi:10.1111/odi.13694. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Fan Z, Wu S, Sang H, Li Q, Cheng S, Zhu H. Identification of GPD1L as a potential prognosis biomarker and associated with immune infiltrates in lung adenocarcinoma. Mediators Inflamm. 2023;2023:9162249. doi:10.1155/2023/9162249. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Tsuchiya H, Shiota G. Immune evasion by cancer stem cells. Regen Ther. 2021;17(8):20–33. doi:10.1016/j.reth.2021.02.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Cao Y, Dai Z, Xie G, Liu G, Guo L, Zhang J. A novel metabolic-related gene signature for predicting clinical prognosis and immune microenvironment in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Exp Cell Res. 2023;428(2):113628. doi:10.1016/j.yexcr.2023.113628. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Gao FY, Li XT, Xu K, Wang RT, Guan XX. c-MYC mediates the crosstalk between breast cancer cells and tumor microenvironment. Cell Commun Signal. 2023;21(1):28. doi:10.1186/s12964-023-01043-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Wang W, Zhang J, Wang Y, Xu Y, Zhang S. Identifies microtubule-binding protein CSPP1 as a novel cancer biomarker associated with ferroptosis and tumor microenvironment. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2022;20:3322–35. doi:10.1016/j.csbj.2022.06.046. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Wang N, Zhu L, Wang L, Shen Z, Huang X. Identification of SHCBP1 as a potential biomarker involving diagnosis, prognosis, and tumor immune microenvironment across multiple cancers. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2022;20(11):3106–19. doi:10.1016/j.csbj.2022.06.039. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Rimal R, Desai P, Daware R, Hosseinnejad A, Prakash J, Lammers T, et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts: origin, function, imaging, and therapeutic targeting. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2022;189:114504. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2022.114504. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Guo Y, Chen M, Yang J, Zhou W, Feng G, Wang Y, et al. CAF-secreted COL5A2 activates the PI3K/AKT pathway to mediate erlotinib resistance in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Dis. 2025;31(2):376–86. doi:10.1111/odi.15130. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Su L, Wu S, Huang C, Zhuo X, Chen J, Jiang X, et al. Chemoresistant fibroblasts dictate neoadjuvant chemotherapeutic response of head and neck cancer via TGFα-EGFR paracrine signaling. npj Precis Oncol. 2023;7(1):102. doi:10.1038/s41698-023-00460-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Weichhart T, Säemann MD. The PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway in innate immune cells: emerging therapeutic applications. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67(Suppl 3):iii70–4. doi:10.1136/ard.2008.098459. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Taghiloo S, Norozi S, Asgarian-Omran H. The Effects of PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway inhibitors on the expression of immune checkpoint ligands in acute myeloid leukemia cell line. Iran J Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2022;21(2):178–88. doi:10.18502/ijaai.v21i2.9225. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Takahashi H, Rokudai S, Kawabata-Iwakawa R, Sakakura K, Oyama T, Nishiyama M, et al. AKT3 is a novel regulator of cancer-associated fibroblasts in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancers. 2021;13(6):1233. doi:10.3390/cancers13061233. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Liao Z, Fan H, Weng J, Zhou J, Zheng Y. FAP serves as a prognostic biomarker in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Anal Cell Pathol. 2024;2024(1):8810804. doi:10.1155/2024/8810804. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Li R, Nan X, Li M, Rahhal O. Fibroblast activation protein (FAP) as a prognostic biomarker in multiple tumors and its therapeutic potential in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oncol Res. 2024;32(8):1323–34. doi:10.32604/or.2024.046965. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Gunaydin G. CAFs interacting with TAMs in tumor microenvironment to enhance tumorigenesis and immune evasion. Front Oncol. 2021;11:668349. doi:10.3389/fonc.2021.668349. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Arpinati L, Scherz-Shouval R. From gatekeepers to providers: regulation of immune functions by cancer-associated fibroblasts. Trends Cancer. 2023;9(5):421–43. doi:10.1016/j.trecan.2023.01.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Varveri A, Papadopoulou M, Papadovasilakis Z, Compeer EB, Legaki AI, Delis A, et al. Immunological synapse formation between T regulatory cells and cancer-associated fibroblasts promotes tumour development. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):4988. doi:10.1038/s41467-024-49282-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Sekiguchi S, Yorozu A, Okazaki F, Niinuma T, Takasawa A, Yamamoto E, et al. ACLP activates cancer-associated fibroblasts and inhibits CD8+ T-cell infiltration in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Cancers. 2023;15(17):4303. doi:10.3390/cancers15174303. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Thijssen VL, Rabinovich GA, Griffioen AW. Vascular galectins: regulators of tumor progression and targets for cancer therapy. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2013;24(6):547–58. doi:10.1016/j.cytogfr.2013.07.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Jiang Z, Zhang W, Sha G, Wang D, Tang D. Galectins are central mediators of immune escape in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancers. 2022;14(22):5475. doi:10.3390/cancers14225475. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Rubinstein N, Alvarez M, Zwirner NW, Toscano MA, Ilarregui JM, Bravo A, et al. Targeted inhibition of galectin-1 gene expression in tumor cells results in heightened T cell-mediated rejection; A potential mechanism of tumor-immune privilege. Cancer Cell. 2004;5(3):241–51. doi:10.1016/S1535-6108(04)00024-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Li C, Guo H, Zhai P, Yan M, Liu C, Wang X, et al. Spatial and single-cell transcriptomics reveal a cancer-associated fibroblast subset in HNSCC that restricts infiltration and antitumor activity of CD8+ T cells. Cancer Res. 2024;84(2):258–75. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-23-1448. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Pathria P, Louis TL, Varner JA. Targeting tumor-associated macrophages in cancer. Trends Immunol. 2019;40(4):310–27. doi:10.1016/j.it.2019.02.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Li M, He L, Zhu J, Zhang P, Liang S. Targeting tumor-associated macrophages for cancer treatment. Cell Biosci. 2022;12(1):85. doi:10.1186/s13578-022-00823-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Zhang P, Zhao Y, Xia X, Mei S, Huang Y, Zhu Y, et al. Expression of OLR1 gene on tumor-associated macrophages of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, and its correlation with clinical outcome. Oncoimmunology. 2023;12(1):2203073. doi:10.1080/2162402X.2023.2203073. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Yang Y, Yan C, Chen XJ. CERCAM is a prognostic biomarker associated with immune infiltration of macrophage M2 polarization in head and neck squamous carcinoma. BMC Oral Health. 2023;23(1):724. doi:10.1186/s12903-023-03421-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Chen L, Wan SC, Mao L, Huang CF, Bu LL, Sun ZJ. NLRP3 in tumor-associated macrophages predicts a poor prognosis and promotes tumor growth in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2023;72(6):1647–60. doi:10.1007/s00262-022-03357-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Fang Z, Han YL, Gao ZJ, Yao F. Cancer-associated fibroblast-derived gene signature discriminates distinct prognoses by integrated single-cell and bulk RNA-seq analyses in breast cancer. Aging. 2024;16(9):8279–305. doi:10.18632/aging.205817. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Liu H, Guo H, Wu Y, Hu Q, Hu G, He H, et al. RCN1 deficiency inhibits oral squamous cell carcinoma progression and THP-1 macrophage M2 polarization. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):21488. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

73. Lee HP, Li CJ, Lee CC. EGFR overexpression and macrophage infiltration correlate with poorer prognosis in HPV-negative oropharyngeal cancer via STAT6 signaling. Head Neck. 2024;46(6):1294–303. doi:10.1002/hed.27734. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Zhang C, Li K, Zhu H, Cheng M, Chen S, Ling R, et al. ITGB6 modulates resistance to anti-CD276 therapy in head and neck cancer by promoting PF4+ macrophage infiltration. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):7077. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

75. Miyamoto T, Murakami R, Hamanishi J, Tanigaki K, Hosoe Y, Mise N, et al. B7-H3 suppresses antitumor immunity via the CCL2-CCR2-M2 macrophage axis and contributes to ovarian cancer progression. Cancer Immunol Res. 2022;10(1):56–69. doi:10.1158/2326-6066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

76. Hsieh CY, Lin CC, Huang YW, Chen JH, Tsou YA, Chang LC, et al. Macrophage secretory IL-1β promotes docetaxel resistance in head and neck squamous carcinoma via SOD2/CAT-ICAM1 signaling. JCI Insight. 2022;7(23):e157285. doi:10.1172/jci.insight.157285. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Mir R, Baba SK, Elfaki I, Algehainy N, Alanazi MA, Altemani FH, et al. Unlocking the secrets of extracellular vesicles: orchestrating tumor microenvironment dynamics in metastasis, drug resistance, and immune evasion. J Cancer. 2024;15(19):6383–415. doi:10.7150/jca.98426. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Asleh K, Dery V, Taylor C, Davey M, Djeungoue-Petga MA, Ouellette RJ. Extracellular vesicle-based liquid biopsy biomarkers and their application in precision immuno-oncology. Biomark Res. 2023;11(1):99. doi:10.1186/s40364-023-00540-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

79. Bernareggi D, Xie Q, Prager BC, Yun J, Cruz LS, Pham TV, et al. CHMP2A regulates tumor sensitivity to natural killer cell-mediated cytotoxicity. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):1899. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-29469-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. You Y, Tian Z, Du Z, Wu K, Xu G, Dai M, et al. M1-like tumor-associated macrophages cascade a mesenchymal/stem-like phenotype of oral squamous cell carcinoma via the IL6/Stat3/THBS1 feedback loop. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2022;41(1):10. doi:10.1186/s13046-021-02222-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Li R, Zhou Y, Zhang M, Xie R, Duan N, Liu H, et al. Oral squamous cell carcinoma-derived EVs promote tumor progression by regulating inflammatory cytokines and the IL-17A-induced signaling pathway. Int Immunopharmacol. 2023;118(2):110094. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2023.110094. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

82. Han N, Zhou D, Ruan M, Yan M, Zhang C. Cancer cell-derived extracellular vesicles drive pre-metastatic niche formation of lymph node via IFNGR1/JAK1/STAT1-activated-PD-L1 expression on FRCs in head and neck cancer. Oral Oncol. 2023;145(3):106524. doi:10.1016/j.oraloncology.2023.106524. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

83. Ren R, Sun H, Ma C, Liu J, Wang H. Colon cancer cells secrete exosomes to promote self-proliferation by shortening mitosis duration and activation of STAT3 in a hypoxic environment. Cell Biosci. 2019;9(1):62. doi:10.1186/s13578-019-0325-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

84. Muñiz-García A, Romero M, Falcόn-Perez JM, Murray P, Zorzano A, Mora S. Hypoxia-induced HIF1α activation regulates small extracellular vesicle release in human embryonic kidney cells. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):1443. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-05161-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

85. Wang X, Wu R, Zhai P, Liu Z, Xia R, Zhang Z, et al. Hypoxia promotes EV secretion by impairing lysosomal homeostasis in HNSCC through negative regulation of ATP6V1A by HIF-1α. J Extracell Vesicles. 2023;12(2):e12310. doi:10.1002/jev2.12310. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

86. Chen XJ, Guo CH, Wang ZC, Yang Y, Pan YH, Liang JY, et al. Hypoxia-induced ZEB1 promotes cervical cancer immune evasion by strengthening the CD47-SIRPα axis. Cell Commun Signal. 2024;22(1):15. doi:10.1186/s12964-023-01450-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

87. Yan Q, Liu J, Liu Y, Wen Z, Jin D, Wang F, et al. Tumor-associated macrophage-derived exosomal miR21-5p promotes tumor angiogenesis by regulating YAP1/HIF-1α axis in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2024;81(1):179. doi:10.1007/s00018-024-05210-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

88. Casey SC, Tong L, Li Y, Do R, Walz S, Fitzgerald KN, et al. MYC regulates the antitumor immune response through CD47 and PD-L1. Science. 2016;352(6282):227–31. doi:10.1126/science.aac9935. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

89. Lastwika KJ, Wilson W3rd, Li QK, Norris J, Xu H, Ghazarian SR, et al. Control of PD-L1 expression by oncogenic activation of the AKT-mTOR pathway in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2016;76(2):227–38. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-3362. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

90. Sato H, Niimi A, Yasuhara T, Permata TBM, Hagiwara Y, Isono M, et al. DNA double-strand break repair pathway regulates PD-L1 expression in cancer cells. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):1751. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-01883-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

91. Chen L, Han X. Anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy of human cancer: past, present, and future. J Clin Invest. 2015;125(9):3384–91. doi:10.1172/JCI80011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

92. Wu L, Liu Y, Deng W, Wu T, Bu L, Chen L. OLR1 is a pan-cancer prognostic and immunotherapeutic predictor associated with EMT and cuproptosis in HNSCC. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(16):12904. doi:10.3390/ijms241612904. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

93. Wang L, He Y, Bai Y, Zhang S, Pang B, Chen A, et al. Construction and validation of a folate metabolism-related gene signature for predicting prognosis in HNSCC. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2024;150(4):198. doi:10.1007/s00432-024-05731-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

94. Ma L, Qin N, Wan W, Song S, Hua S, Jiang C, et al. TLR9 activation induces immunosuppression and tumorigenesis via PARP1/PD-L1 signaling pathway in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2024;326(2):C362–81. doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00061.2023. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

95. Jung AR, Jung CH, Noh JK, Lee YC, Eun YG. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition gene signature is associated with prognosis and tumor microenvironment in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):3652. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-60707-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

96. Garcia-Diaz A, Shin DS, Moreno BH, Saco J, Escuin-Ordinas H, Rodriguez GA, et al. Interferon receptor signaling pathways regulating PD-L1 and PD-L2 expression. Cell Rep. 2017;19(6):1189–201. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2017.04.031. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

97. Xu Y, Gao Z, Hu R, Wang Y, Wang Y, Su Z, et al. PD-L2 glycosylation promotes immune evasion and predicts anti-EGFR efficacy. J Immunother Cancer. 2021;9(10):e002699. doi:10.1136/jitc-2021-002699. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

98. Ferris RL, Haddad R, Even C, Tahara M, Dvorkin M, Ciuleanu TE, et al. Durvalumab with or without tremelimumab in patients with recurrent or metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: EAGLE, a randomized, open-label phase III study. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(7):942–50. doi:10.1016/j.annonc.2020.04.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

99. Johnson ML, Cho BC, Luft A, Alatorre-Alexander J, Geater SL, Laktionov K, et al. Durvalumab with or without tremelimumab in combination with chemotherapy as first-line therapy for metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: the phase III POSEIDON study. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(6):1213–27. doi:10.1200/JCO.22.00975. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

100. Gao X, Xu N, Li Z, Shen L, Ji K, Zheng Z, et al. Safety and antitumour activity of cadonilimab, an anti-PD-1/CTLA-4 bispecific antibody, for patients with advanced solid tumours (COMPASSION-03a multicentre, open-label, phase 1b/2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2023;24(10):1134–46. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(23)00411-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

101. Lerner EC, Woroniecka KI, D’Anniballe VM, Wilkinson DS, Mohan AA, Lorrey SJ, et al. CD8+ T cells maintain killing of MHC-I-negative tumor cells through the NKG2D-NKG2DL axis. Nat Cancer. 2023;4(9):1258–72. doi:10.1038/s43018-023-00600-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

102. Kawase K, Kawashima S, Nagasaki J, Inozume T, Tanji E, Kawazu M, et al. High expression of MHC class I overcomes cancer immunotherapy resistance due to IFNγ signaling pathway defects. Cancer Immunol Res. 2023;11(7):895–908. doi:10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-22-0815. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

103. Liao TT, Chen YH, Li ZY, Hsiao AC, Huang YL, Hao RX, et al. Hypoxia-induced long noncoding RNA HIF1A-AS2 regulates stability of MHC class I protein in head and neck cancer. Cancer Immunol Res. 2024;12(10):1468–84. doi:10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-23-0622. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

104. Li H, Xiong HG, Xiao Y, Yang QC, Yang SC, Tang HC, et al. Long non-coding RNA LINC02195 as a regulator of MHC I molecules and favorable prognostic marker for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Front Oncol. 2020;10:615. doi:10.3389/fonc.2020.00615. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

105. Wang X, Xu S, Fu T, Wu Y, Sun W. Combination of downregulating FEN1 and PD-1 blockade enhances antitumor activity of CD8+ T cells against HNSCC cells in vitro. J Oral Pathol Med. 2023;52(9):834–42. doi:10.1111/jop.13485. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

106. Wang S, Wang X, Sun J, Yang J, Wu D, Wu F, et al. Down-regulation of DNA key protein-FEN1 inhibits OSCC growth by affecting immunosuppressive phenotypes via IFN-γ/JAK/STAT-1. Int J Oral Sci. 2023;15(1):17. doi:10.1038/s41368-023-00221-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

107. Kono M, Komatsuda H, Yamaki H, Kumai T, Hayashi R, Wakisaka R, et al. Immunomodulation via FGFR inhibition augments FGFR1 targeting T-cell based antitumor immunotherapy for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oncoimmunology. 2022;11(1):2021619. doi:10.1080/2162402X.2021.2021619. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

108. Robbins Y, Friedman J, Redman J, Sievers C, Lassoued W, Gulley JL, et al. Tumor cell HLA class I expression and pathologic response following neoadjuvant immunotherapy for newly diagnosed head and neck cancer. Oral Oncol. 2023;138(11):106309. doi:10.1016/j.oraloncology.2023.106309. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

109. Komatsuda H, Wakisaka R, Kono M, Kumai T, Hayashi R, Yamaki H, et al. Mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibition augments the T cell response against HOXB7-expressing tumor through human leukocyte antigen upregulation. Cancer Sci. 2023;114(2):399–409. doi:10.1111/cas.15619. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

110. Wei Z, Shen Y, Zhou C, Cao Y, Deng H, Shen Z. CD3D: a prognostic biomarker associated with immune infiltration and immunotherapeutic response in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Bioengineered. 2022;13(5):13784–800. doi:10.1080/21655979.2022.2084254. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

111. Castro F, Cardoso AP, Gonçalves RM, Serre K, Oliveira MJ. Interferon-gamma at the crossroads of tumor immune surveillance or evasion. Front Immunol. 2018;9:847. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.00847. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

112. Tanagala KKK, Morin-Baxter J, Carvajal R, Cheema M, Dubey S, Nakagawa H, et al. SP140 inhibits STAT1 signaling, induces IFN-γ in tumor-associated macrophages, and is a predictive biomarker of immunotherapy response. J Immunother Cancer. 2022;10(12):e005088. doi:10.1136/jitc-2022-005088. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

113. Kusmartsev S, Gabrilovich DI. STAT1 signaling regulates tumor-associated macrophage-mediated T cell deletion. J Immunol. 2005;174(8):4880–91. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.174.8.4880. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

114. Ma S, Sun B, Duan S, Han J, Barr T, Zhang J, et al. YTHDF2 orchestrates tumor-associated macrophage reprogramming and controls antitumor immunity through CD8+ T cells. Nat Immunol. 2023;24(2):255–66. doi:10.1038/s41590-022-01398-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

115. Oh DY, Fong L. Cytotoxic CD4+ T cells in cancer: expanding the immune effector toolbox. Immunity. 2021;54(12):2701–11. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2021.11.015. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

116. Lin X, Zhao X, Chen Y, Yang R, Dai Z, Li W, et al. CXC ligand 13 orchestrates an immunoactive microenvironment and enhances immunotherapy response in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2024;38:3946320241227312. doi:10.1177/03946320241227312. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

117. Yan S, Zhang X, Lin Q, Du M, Li Y, He S, et al. Deciphering the interplay of HPV infection, MHC-II expression, and CXCL13+ CD4+ T cell activation in oropharyngeal cancer: implications for immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2024;73(10):206. doi:10.1007/s00262-024-03789-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

118. Liu Z, Meng X, Tang X, Zou W, He Y. Intratumoral tertiary lymphoid structures promote patient survival and immunotherapy response in head neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2023;72(6):1505–21. doi:10.1007/s00262-022-03310-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

119. Zhang Q, Wu S. Tertiary lymphoid structures are critical for cancer prognosis and therapeutic response. Front Immunol. 2022;13:1063711. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

120. Ruffin AT, Cillo AR, Tabib T, Liu A, Onkar S, Kunning SR, et al. B cell signatures and tertiary lymphoid structures contribute to outcome in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):3349. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-23355-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

121. Yu M, Qian LiXX, Cheng G, Lin Z, Z. Prognostic biomarker IL17A correlated with immune infiltrates in head and neck cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2022;20(1):243. doi:10.1186/s12957-022-02703-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

122. Huang R, Sun Z, Xian S, Song D, Chang Z, Yan P, et al. The role of toll-like receptors (TLRs) in pan-cancer. Ann Med. 2022;54(1):1918–37. doi:10.1080/07853890.2022.2095664. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

123. Fore F, Budipranama M, Destiawan RA. TLR10 and its role in immunity. In: Toll-like receptors in health and disease. Vol. 276. Cham: Springer; 2021. p. 161–74. doi:10.1007/164_2021_541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

124. Balachandran Y, Caldwell S, Aulakh GK, Singh B. Regulation of TLR10 expression and its role in chemotaxis of human neutrophils. J Innate Immun. 2022;14(6):629–42. doi:10.1159/000524461. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

125. Khan H, Pandey SN, Mishra A, Srivastava R. Suppression of TLR signaling by IRAK-1 and -4 dual inhibitor decreases TPF-resistance-induced pro-oncogenic effects in HNSCC. 3 Biotech. 2023;13(1):14. doi:10.1007/s13205-022-03420-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

126. Haddad RI, Harrington K, Tahara M, Ferris RL, Gillison M, Fayette J, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus EXTREME regimen as first-line treatment for recurrent/metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: tthe final results of CheckMate 651. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(12):2166–80. doi:10.1200/JCO.22.00332. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

127. Ju WT, Xia RH, Zhu DW, Dou SJ, Zhu GP, Dong MJ, et al. A pilot study of neoadjuvant combination of anti-PD-1 camrelizumab and VEGFR2 inhibitor apatinib for locally advanced resectable oral squamous cell carcinoma. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):5378. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-33080-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

128. Shayan G, Kansy BA, Gibson SP, Srivastava RM, Bryan JK, Bauman JE, et al. Phase Ib study of immune biomarker modulation with neoadjuvant cetuximab and TLR8 stimulation in head and neck cancer to overcome suppressive myeloid signals. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24(1):62–72. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-0357. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

129. Khushalani NI, Ott PA, Ferris RL, Cascone T, Schadendorf D, Le DT, et al. Final results of urelumab, an anti-CD137 agonist monoclonal antibody, in combination with cetuximab or nivolumab in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Immunother Cancer. 2024;12(3):e007364. doi:10.1136/jitc-2023-007364. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

130. Chen J, Li K, Chen J, Wang X, Ling R, Cheng M, et al. Aberrant translation regulated by METTL1/WDR4-mediated tRNA N7-methylguanosine modification drives head and neck squamous cell carcinoma progression. Cancer Commun. 2022;42(3):223–44. doi:10.1002/cac2.12273. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

131. Kim HR, Kang HN, Yun MR, Ju KY, Choi JW, Jung DM, et al. Mouse-human co-clinical trials demonstrate superior anti-tumour effects of buparlisib (BKM120) and cetuximab combination in squamous cell carcinoma of head and neck. Br J Cancer. 2020;123(12):1720–9. doi:10.1038/s41416-020-01074-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

132. Krebs MG, Forster M, Majem M, Peguero J, Iams W, Clay T, et al. Eftilagimod alpha (a Soluble LAG-3 Protein) combined with pembrolizumab in second-line metastatic NSCLC refractory to anti-programmed cell death protein 1/programmed death-ligand 1-based therapy: final results from a phase 2 study. JTO Clin Res Rep. 2024;5(11):100725. doi:10.1016/j.jtocrr.2024.100725. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

133. Ma Y, Huang Y, Zhao Y, Zhao S, Xue J, Yang Y, et al. BL-B01D1, a first-in-class EGFR-HER3 bispecific antibody-drug conjugate, in patients with locally advanced or metastatic solid tumours: a first-in-human, open-label, multicentre, phase 1 study. Lancet Oncol. 2024;25(7):901–11. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(24)00159-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

134. Kim KH, Lim SM, Ahn HK, Lee YG, Lee KW, Ahn MJ, et al. A phase II trial of nintedanib in patients with metastatic or recurrent head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: in-depth analysis of nintedanib arm from the KCSG HN 15-16 TRIUMPH trial. Cancer Res Treat. 2024;56(1):37–47. doi:10.4143/crt.2023.433. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools