Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

First-Line Aumolertinib in EGFR-Mutant Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Multicenter Real-World Retrospective Study with a Four-Year Follow-Up

1 Department of Oncology, Affiliated Hospital of Guilin Medical University, Guilin, 541001, China

2 Department of Radiotherapy, Affiliated Hospital of Guilin Medical University, Guilin, 541001, China

3 Department of Oncology, Guilin People’s Hospital, Guilin, 541300, China

4 Department of Oncology and Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine, The People’s Hospital of Hezhou, Hezhou, 542899, China

5 Department of Oncology, Liuzhou Workers’ Hospital, Liuzhou, 545001, China

6 Department of Oncology, Nanxishan Hospital of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, Guilin, 541002, China

7 Department of Oncology, Liuzhou People’s Hospital, Liuzhou, 545001, China

8 Department of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, The First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University, Nanning, 530021, China

* Corresponding Author: Feng Xue. Email:

# These two authors contributed equally to this work

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Multi-Omics Approaches for Precision Medicine)

Oncology Research 2025, 33(9), 2451-2462. https://doi.org/10.32604/or.2025.064119

Received 05 February 2025; Accepted 29 April 2025; Issue published 28 August 2025

Abstract

Background: The use of third-generation different tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) is considered the most effective option for treating advanced non-small cell lung cancer (aNSCLC) with epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations. However, there is limited information on the efficacy and safety of aumolertinib in patients remains these cases. Methods: The clinical records of patients receiving aumolertinib as first-line therapy across four hospitals in the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region from April 2020 to December 2021 were retrospectively analyzed, using progression-free survival (PFS) as the primary endpoint and overall survival (OS) representing the secondary endpoint. Adverse events (AEs) were assessed using the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE v5.0). Results: Approximately 47 patients with EGFR-Mutant aNSCLC were recruited, including 1 squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) patient, 1 EGFR G719C mutated patient, 1 EGFR S768 patient mutated, and 1 EGFR KDD mutated patient. The average follow-up duration was 48.1 months concluding in August 2024. The median PFS (mPFS) was 22.2 months (95% CI 17.6 to 26.7), while the median OS (mOS) was 39.7 months (95% CI 32.6 to 46.9). Patients with deletion of exon19 in EGFR (19del) showeda mPFS of 28.4 months, markedlylonger than those with the L858R point mutation (L858R), who had a mPFS of 15.2 months (p = 0.036). Overall, 22 patients (46.8%) had central nervous system (CNS) metastases at the basal level. The mPFS for this cohort was 19.7 months. Rashes (17.0%), skin decrustation (4.2%), pruritus (4.2%), dental ulcers (4.2%), increased creatine kinase (2.1%), and musculoskeletal pains (2.1%) were the most prevalent AEs in this study. Grade 3 and higher AEs were observed at a rate of 4.2%. Conclusion: This study concluded that aumolertinib has considerable safety and efficacy for EGFR-mutant NSCLC in a first-line defense.Keywords

Lung cancer is a highly aggressive and prevalent disease globally, with approximately 2.2 million new cases and 1.8 million deaths reported in 2020 [1]. In 2022, Chinese government statistics indicated approximately 1,060,600 new cases of LC [2]. Its elevated incidence rate signifies a major threat to public health and a substantial societal burden. Traditional treatment for LC is of paramount significance. However, NSCLC is the predominant pathophysiological subtype of LC, and its survival rates have markedly improved due to targeted therapy and immunochemotherapy [3,4]. Mutations in the EGFR are the predominant category of mutations in NSCLC, and various tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) have been prescribed for individuals with EGFR-sensitive mutations [5]. Besides, 1st or 2nd-generation TKIs show more effectiveness relative to platinum-based chemotherapy. However, acquired resistance (AR) to these generations of TKIs is unavoidable. EGFR T790M is the predominant resistance mechanism in secondary EGFR mutations [6]. The third-generation TKI, osimertinib, has been found both effective and safe in treating NSCLC patients with T790M and EGFR-sensitive mutations [7–9]. Osimertinib has received approval from theUS FDA for treating cases of EGFR T790M-positive aNSCLC showing disease progression with first- and second-generation TKIs, as well as treatment-naïve cases with EGFR sensitizing mutations. This approval marks the onset of a new era in third-generation targeted therapies.

Aumolertinib is classified as a 3rd generation TKI and functions as an oral, irreversible therapeutic agent that explicitly targets both EGFR-sensitizing and T790M mutations [10]. In the study of AENEAS involving advanced EGFR mutated-positive NSCLC Chinese patients, their mPFS was reported as 19.3 months for aumolertinib relative to 9.9 months for gefitinib. Moreover, AEs of grade > 3 severity (regardless of cause) occurred in 36.4% of patients treated with aumolertinib and 35.8% of those receiving gefitinib [11]. However, OS data were not disclosed in this study. Among the existing 3rd generation TKIs, only osimertinib has revealed OS data, with a mOS of 38.6 months [9]. Commutations frequently lead to unfavorable prognoses. Tumor protein 53 (TP53) is the most frequent variant among numerous co-mutations [12,13]. Further, phase III clinical research trials cannot accurately depict real-world scenarios due to the stringency of their inclusion and exclusion criteria.

This study reports a multicenter clinical trial evaluating the effectiveness of aumolertinib as a first-line therapy in treatment-naïve cases diagnosed with EGFR-mutant aNSCLC.

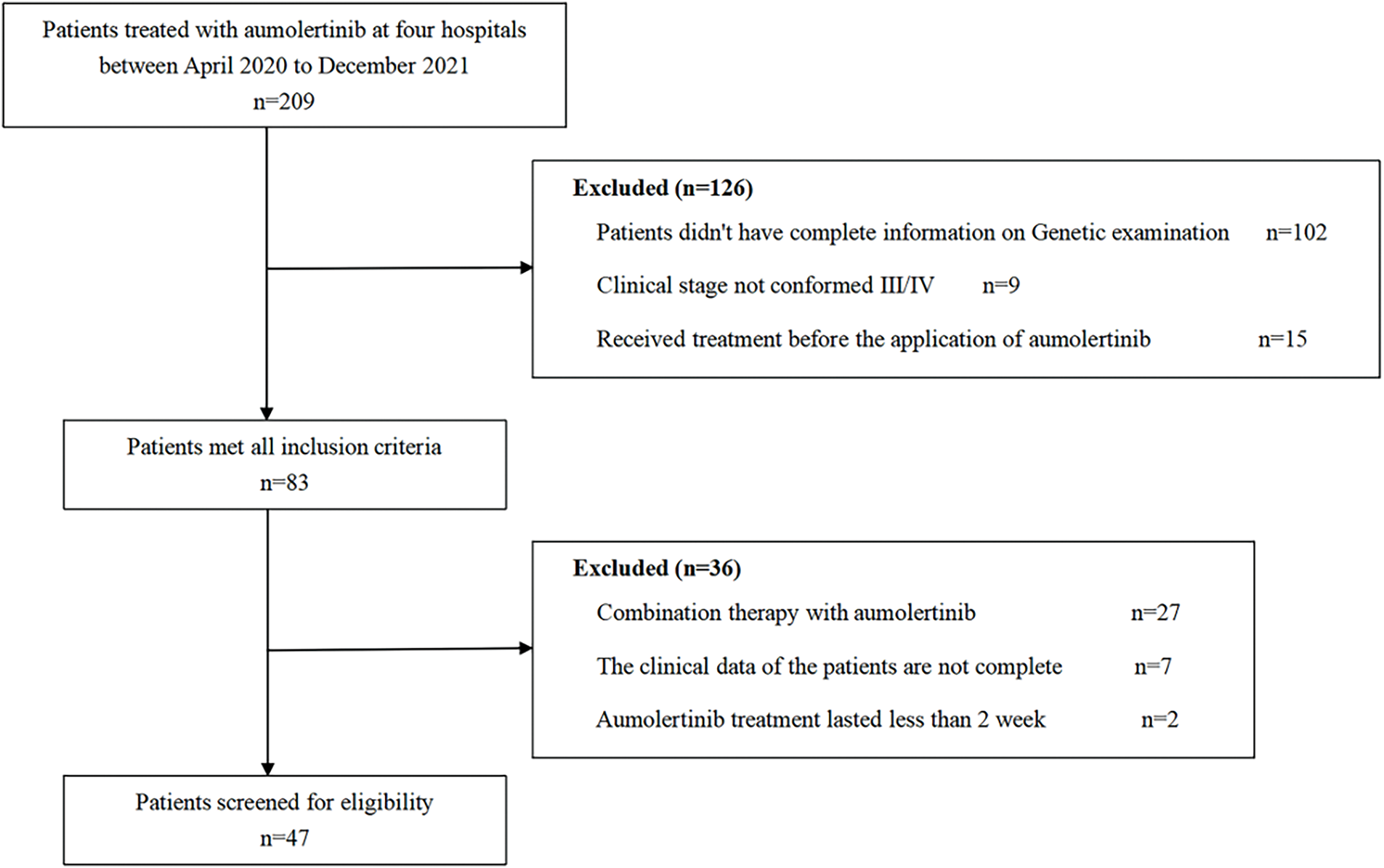

Patients with aNSCLC who were administered aumolertinib at 4 hospitals in the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region of China between April 2020 and December 2021 were recruited for this retrospective analysis. Inclusion criteria: (1) Pathologically confirmed NSCLC; (2) Confirmation of EGFR mutations via polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or next-generation sequencing (NGS); (3) Clinical stage IIIB or IV; (4) Age ≥ 18 years; (5) No prior treatment before initiation of aumolertinib; (6) Presence of measurable lesions as described in the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST v1.1) [14]. The exclusion criteria were: (1) combined aumolertinib therapeutics; (2) incomplete medical history; (3) aumolertinib treatment lasting < 2 weeks. All screening procedures are illustrated in Fig. 1. From the medical records of each patient, data on several clinicopathological factors, such as sex, age, histopathological subtype, clinical grading, diagnosis date, distant metastasic site, and information about key genes (type of EGFR mutation, associated mutations in NGS), were obtained. This retrospective study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Guilin Medical University (Guilin, China; approval no. 2022IITLL-05-G1), which fully complies with the Declaration of Helsinki. Each patient or their closest relatives submitted an informed consent. The study report follows the STROBE guidelines to enhance the standardization of the paper.

Figure 1: Flowchart depicting patient participation in the study

All eligible patients received 110 mg oral aumolertinib once per day as 1st-line treatment until progression of the disease as per the RECIST v1.1 [14], death, or unacceptable toxicity. All AEs were examined via the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE 5.0).

2.3 Assessment of Efficacy and Toxicity

The primary and secondary outcomes were PFS and OS, respectively. The examiner assessed all endpoints or outcomes in line with RECIST. Furthermore, PFS represented the interval between initiation of aumolertinib treatment to disease progression or death, while OS was measured from treatment start to death. The subsequent phase included obtaining survival information through telephone interviews or visits to an ambulatory clinic and hospitalization data up to 30 August 2024.

Data was statistically examined via SPSS® software v27.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). All survival curves were generated via the Kaplan-Meier method. The log-rank test was used to compare differences in PFS between the groups. The PFS differences between groups were compared using the log-rank test. Cox proportional hazards regression models were employed to assess the influence of various variables on PFS. A double tail with a p < 0.05 defined the level of significance.

3.1 Basic Information about Patients

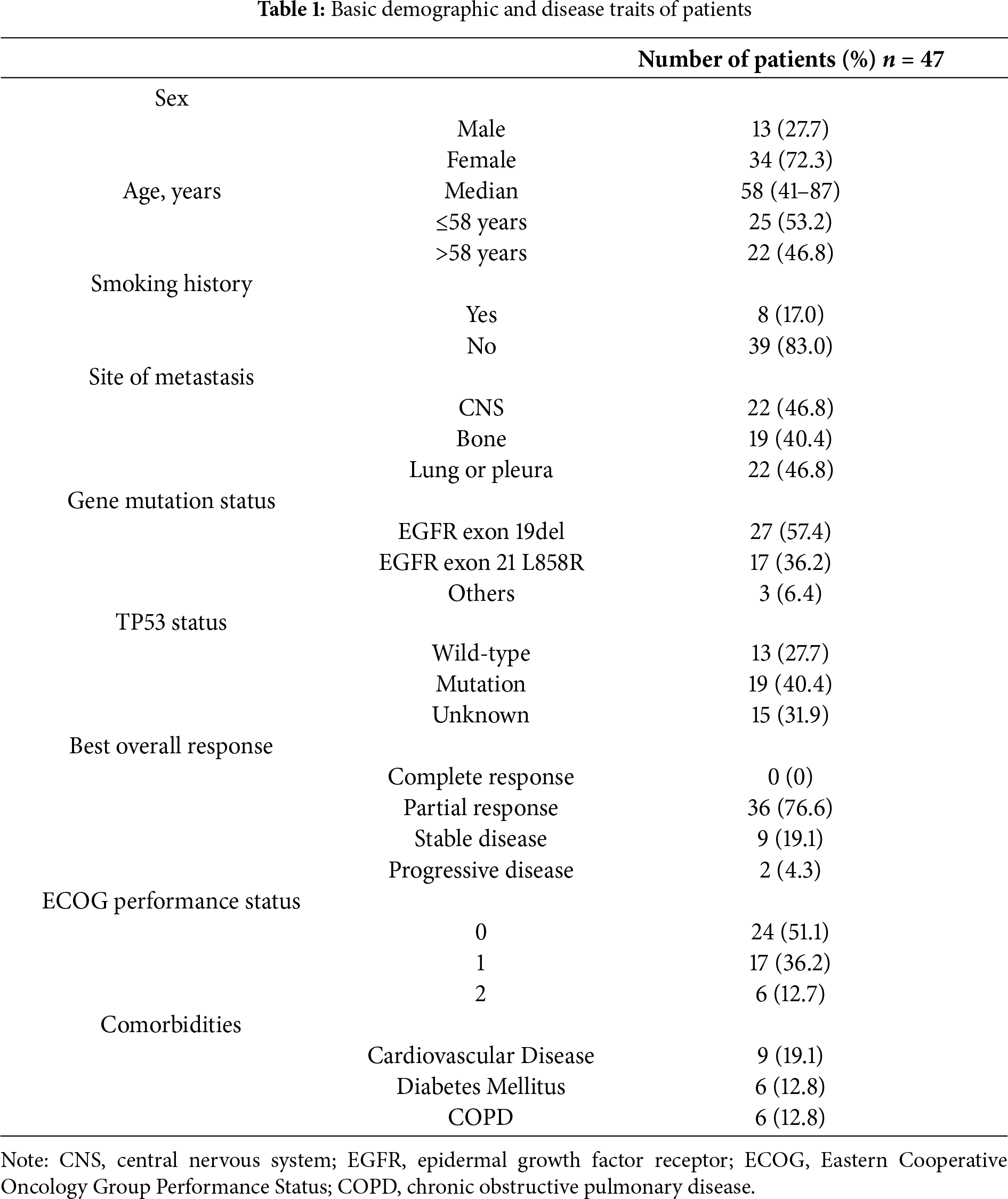

Forty-seven cases treated at 4 hospitals in China between April 2020 and December 2021 were recruited. The respondent population comprised 27.7% males and 72.3% females, aged 58 years on average (range 41 to 87 years). Pathologically, there was one case of lung SCC and 46 cases of adenocarcinoma. All diagnoses with stage IV.

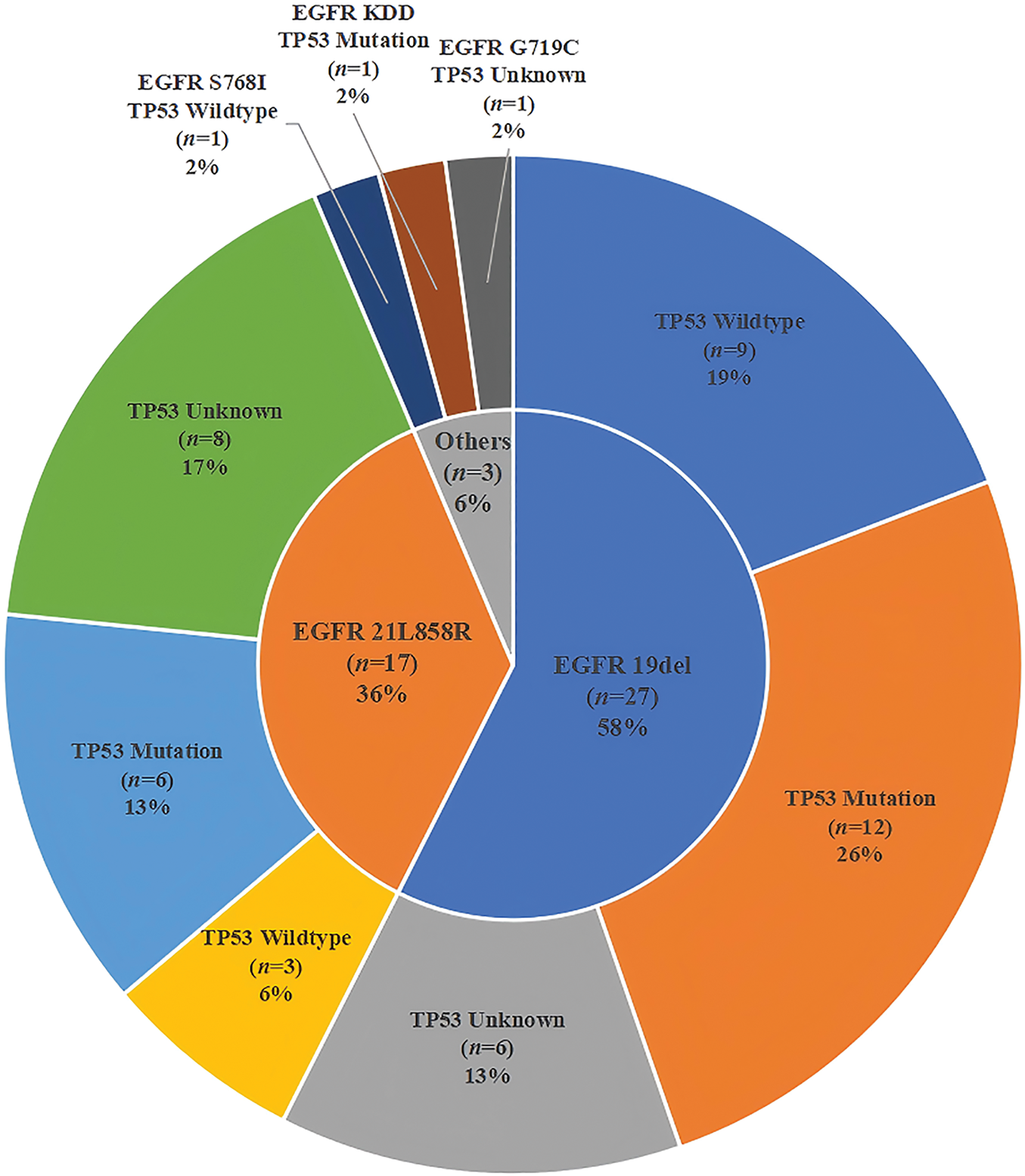

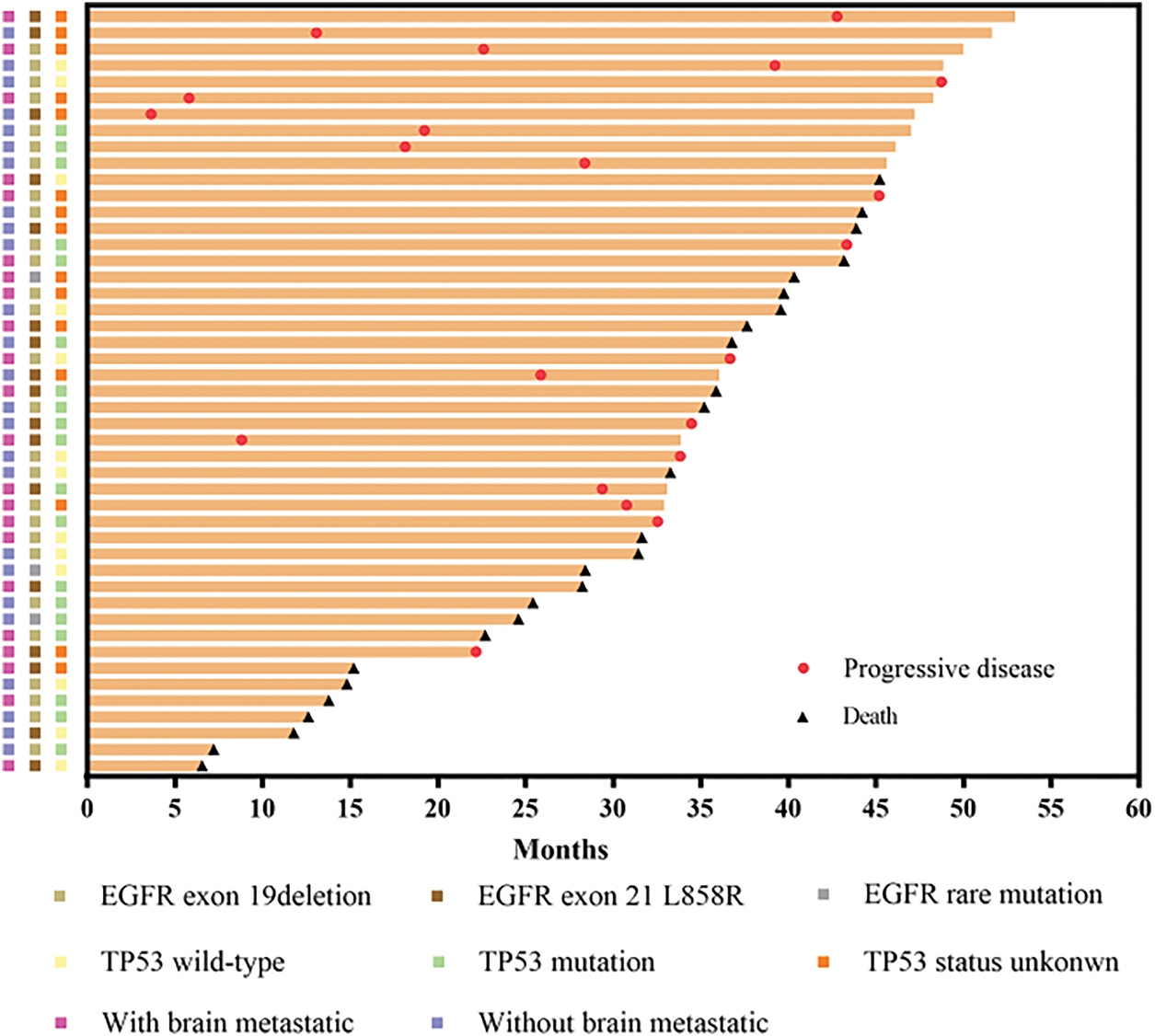

Both NGS and PCR analyses of these patients revealed that 57.4% (27/47) of them carried the 19del, 36.2% (17/47) had the L858R, and 6.4% (3/47) contained other types of EGFR variations. Meanwhile, the proportion of TP53-positive patients (32/47, 68.1%) was higher than the TP53-negative patients (15/47, 31.9%). The proportions of TP53 mutation, wild-type (WT) or unknown mutations in patients with 19del, L858R, or the other EGFR mutations, including G719C, KDD, and S768I, were different (Fig. 2). Fig. 3 illustrates the clinical treatment strategies for patients categorized by their respective gene mutations. Among all patients, 46.8% (22/47) had brain metastasis, 40.4% (19/47) had bone metastasis, and 46.8% (22/47) had lung or pleural metastasis (Table 1).

Figure 2: Pie chart illustrates the distribution of EGFR mutated and TP53 mutated status in patients

Figure 3: Swimmer plot showing length of cancer control in cases with different EGFR mutations and TP53 status, as well as with and without CNS metastasis

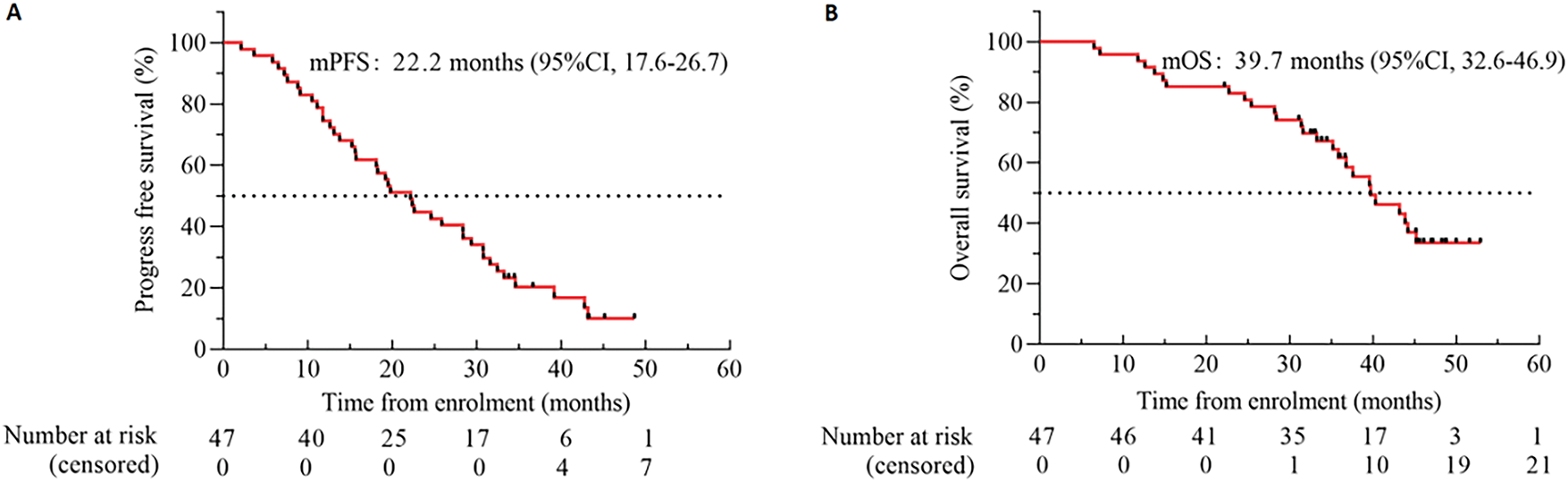

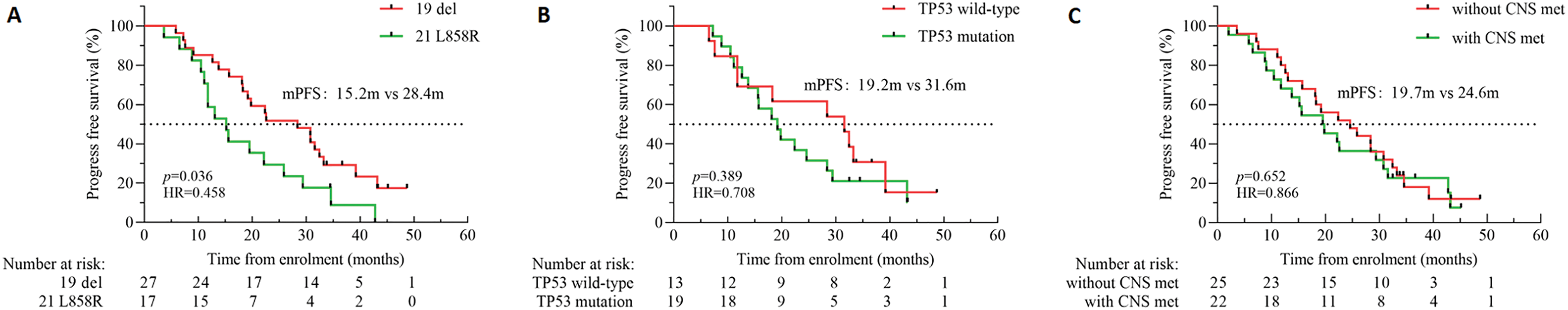

The investigator assessed the mPFS at 22.2 months (95% CI 17.6 to 26.7) (Fig. 4A) and the mOS at 39.7 months (95% CI 32.6 to 46.9) (Fig. 4B). The standard follow-up duration was 48.1 months by the end of August 2024, and 44.7% (21/47) of the patients were recovered. The mPFS of cases with the 19del mutation was 28.4 months (95% CI 14.1 to 42.6), markedly longer than the 15.2 months (95% CI 10.0 to 20.4) seen in those with L858R (p < 0.05) (Fig. 5A). The mPFS of TP53 WT patients was 31.6 months (95% CI 15.0 to 48.3), and that of TP53 mutated cases was 19.2 months (95% CI 13.4 to 25.1). Both groups failed to show a substantial variation in mPFS (p = 0.389) (Fig. 5B). The mPFS was 19.7 months (95% CI 11.5 to 27.5) for all cases with CNS metastases. In contrast to patients who did not have CNS metastases, the mPFS was 24.6 months (95% CI 13.8 to 35.4, HR: 0.866; p = 0.652) (Fig. 5C).

Figure 4: Kaplan-Meier estimates of PFS (A) and OS (B). Black tick marks illustrate censored data. Abbreviation: CI denotes confidence interval

Figure 5: Kaplan-Meier survival curves representing the following parameters: PFS; (A) PFS in patients with the EGFR exon 19del or the L858R mutation; (B) PFS in patients with the TP53 WT or TP53 mutation; (C) PFS in patients with or without CNS metastases

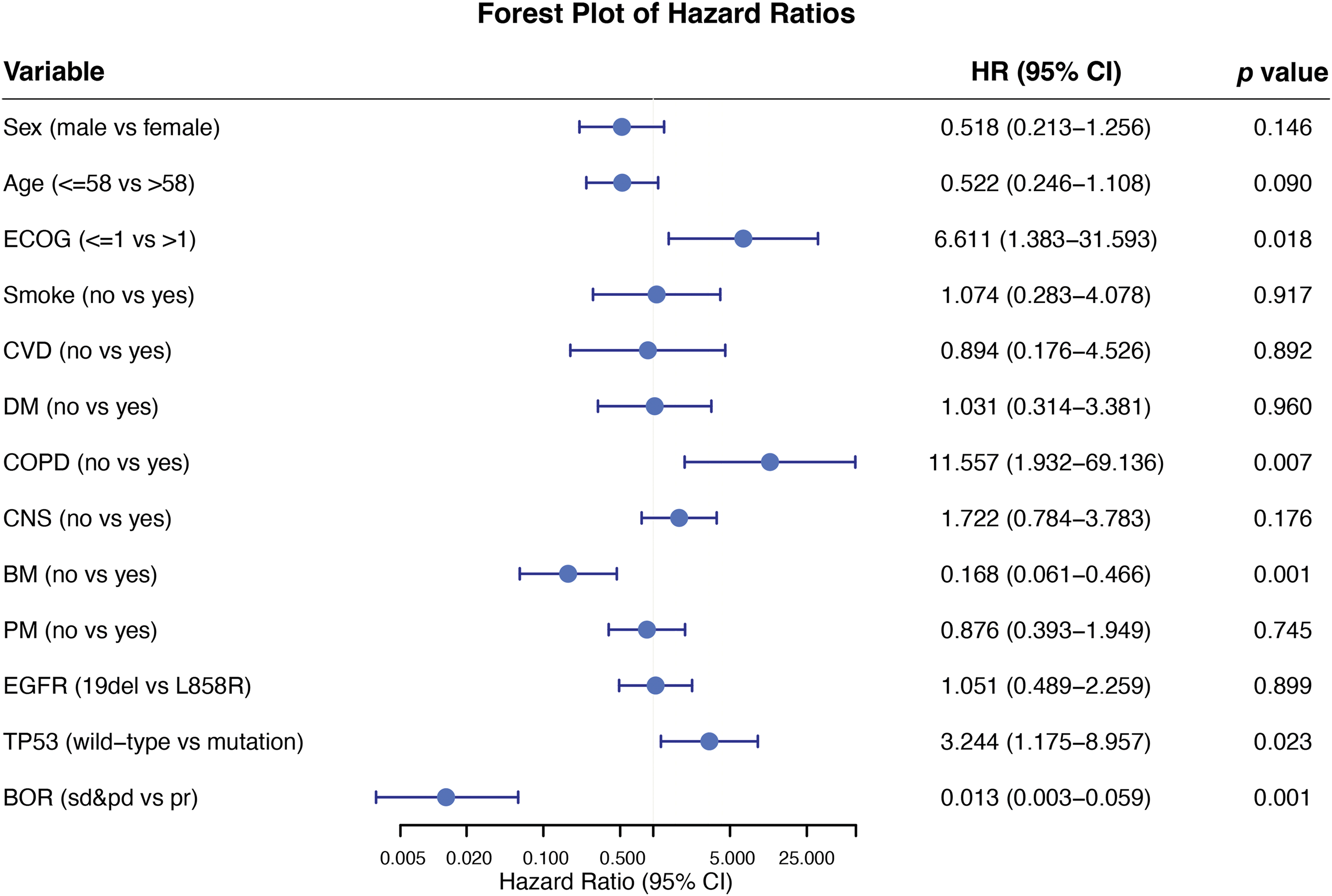

In this empirical study, the researcher assessed the best object response (BOR) of aumolertinib using patient historical records. The BOR indicated that 36 patients revealed a partial response, 9 demonstrated stable conditions, and 2 experienced progressive disease. The objective response rate (ORR) was 76.6% (36/47), while the disease control rate (DCR) was 95.7% (45/47). The ORR of patients with underlying brain metastases was 72.7% (16/22), while the DCR was 95.5% (21/22). At the study cutoff, 40 patients either suffered from disease progression or died due to their disease. Specifically, disease progression or mortality was observed in 77.8% (20/27) of patients with the 19del mutation and 94.1% (16/17) of those with the L858R mutation. The PFS analysis by additional subgroups including sex, age, smoking history, and baseline ECOG performance status, is presented in Fig. 6.

Figure 6: Subgroup analysis forest plot for progression-free survival

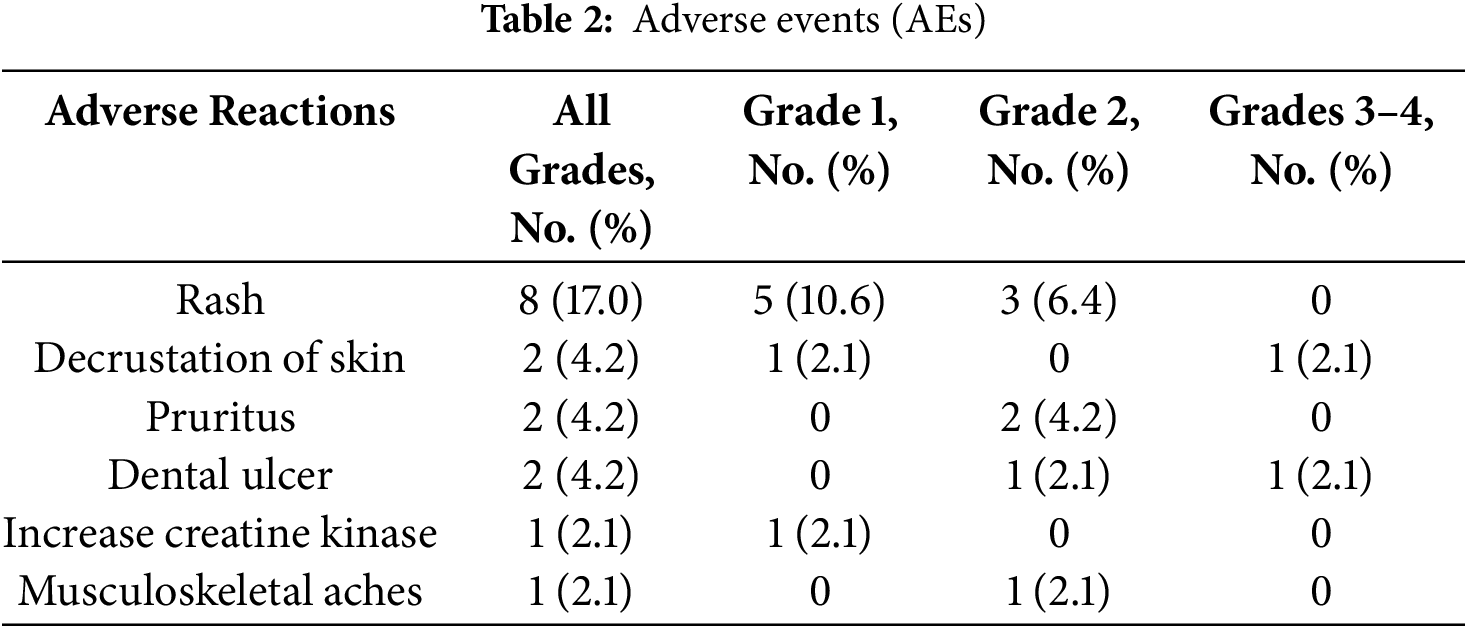

At the data cutoff point, 66.0% (31/47) of cases (median follow-up, 48.1 months) were free from any treatment-related AEs. The retrospective analysis identified several AEs, which included rash (17.0%), skin decrustation (4.2%), pruritus (4.2%), dental ulcer (4.2%), increased creatine kinase (2.1%), and musculoskeletal aches (2.1%) as detailed in Table 2. Among the treatment-emergent AEs, decrustation of the skin (2.1%) and dental lesions (2.1%) were classified as Grades 3–4. A total of 33.3% (9/27) patients with 19del had AEs, and 35.3% (6/17) patients with L858R mutation had AEs. The prevalence of AEs was comparable between the two gene mutation types. The discontinuation and reduction of dosage due to drug toxicity were not observed. All adverse reactions were effectively alleviated through targeted symptomatic management, and no long-term toxicities related to the heart, lungs, etc. were observed in the real-world retrospective study.

CTCAE v5.0: Grade 1: Mild; either no symptoms or mild symptoms, with observation rather than intervention indicated. Grade 2: Moderate to severe effects, potentially requiring minimal, local or non-invasive treatment; potentially interfering with age-appropriate instrumental activities of daily living. Grade 3: Severe or medically significant effects that while not immediately life-threatening may need hospitalization or prolongation of existing hospitalization potentially disabling or leading to substantial impairment of self-care and daily living activities. Grade 4: Life-threatening requiring urgent intervention indicated.

This study marks a pioneering multicenter clinical investigation in China, with a follow-up period exceeding four years for patients with EGFR-mutant NSCLC treated with aumolertinib. The findings indicate a favorable profile regarding efficacy and safety within the 1st-line treatment defense.

In the current study, a mPFS duration of 22.2 months was observed, which was higher than that of other published pivotal clinical trials [11,15,16]. Moreover, this study followed the trial’s secondary endpoints by demonstrating a 39.7-month mOS. This method temporarily solved the data gaps in the survival period [11]. The mPFS of this study was higher than that of commonly used third-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors of the same class, which were 18.9 and 20.8 months, respectively, for osimertinib and furmonertinib [15,16]. In contrast to the AENEAS study, this study included a limited group of patients with rare mutations with improved survival times. Compared with the three Phase III clinical studies [11,15,16], this retrospective study reported a higher proportion of brain metastases (46.8%) at first diagnosis, indicating a poor prognosis. However, the current findings suggest that the mPFS for patients with brain metastasis was 19.7 months, exceeding the results observed in the AENEAS study. Despite the absence of statistically substantial variations in mPFS between both groups (p = 0.724), the subgroups characterized by brain metastasis displayed a trend towards shorter mPFS than those without brain metastasis (19.7 vs. 24.6 m). Pharmacokinetic studies in mice revealed that aumolertinib can pass the blood-brain barrier. Similarly, the present findings were aligned with previous studies on CNS metastases in EGFR-mutated advanced NSCLC [17]. The Grades 3–4 treatment-associated AEs were decrustation of the skin (2.1%) and dental ulcers (2.1%). No AE-related dose modifications were observed.

In previous studies [18–20], patients with L858R had a worse prognosis than those with exon 19del. This study examined the variations in mPFS across various mutation subtypes. The current results depicted that L858R mutated patients demonstrated a substantially reduced mPFS compared to those with the 19del mutation (15.2 vs. 28.4 m), with a statistically significant disparity observed between both subgroups (p = 0.048). Both subgroups revealed statistical variances consistent with previous studies [18,19]. Currently, several combination regimens comprising TKIs have shown improved outcomes for the L858R subtype in phase III clinical studies [21,22], and TKI remains the standard 1st-line treatment option due to safety concerns. However, therapeutic options following disease progression after first-line treatment remain relatively limited. Amivantamab, a bispecific antibody targeting both EGFR and MET, has demonstrated promising efficacy in cases with disease progression following osimertinib treatment [23]. Simultaneously, Amivantamab has been found effective in patients harboring EGFR exon 20 insertion mutations [24].

Osimertinib with chemotherapy as 1st-line treatment has shown initial efficacy in patients with L858R or CNS metastasis [25]. Strategies for combination therapy are still being explored. The presence of concomitant mutations is a definitive factor affecting the effectiveness of TKI in aNSCLC characterized by EGFR mutations [26]. TP53 alterations have found to be associated with more rapid drug resistance, irrespective of the underlying mechanisms, resulting in decreased PFS and OS in patients with EGFR-mutant NSCLC [27]. Mutant TP53 has greater stability than WT TP53, leading to its functional loss. This accumulation within cells promotes cancer cell growth, penetration, metastasis, and resistance to therapeutic agents [28]. TP53 was one of the most prevalent concomitant mutations in the NGS data of this research, although the NGS panels of patients were not fully consistent in this real-world retrospective study (32/47, 68.1%). The mPFS trend of patients with the TP53 mutation was shorter than that of TP53 WT patients (19.2 vs. 31.6 m), but no considerable disparity was observed between both groups (p = 0.175). Subgroup analysis revealed that a higher Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status (ECOG) score, the presence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and TP53 mutation status were markedly linked with reduced PFS. Conversely, achieving the best objective response was strongly linked to prolonged PFS.

In this study, a patient with stage IV SCC was found to have a 19del and multiple co-mutations, including TP53 via NGS. The patient’s ECOG performance status was 4 at diagnosis. The patient’s symptoms resolved rapidly after administering aumolertinib, and computed tomography (CT) confirmed a partial remission, with a PFS of 19.8 months. Despite rare EGFR mutations, like EGFR KDD and EGFR S768I, two patients had favorable PFS of 24.6 and 28.4 m, respectively. The patient with the EGFR KDD mutation also harbored the TP53 concomitant mutations. Many studies have demonstrated that the therapeutic efficacy of 1st and 2nd generation TKIs is restricted in patients with lung SCC and lung adenocarcinoma that contains EGFR KDD mutations [29–31]. Until now, there has been relatively limited data concerning treating such patients with 3rd generation TKIs and further research is warranted.

The most common AEs in the current cohort were rash (17.0%), skin decrustation (4.2%), pruritus (4.2%), dental ulcer (4.2%), increased creatine kinase (2.1%), and musculoskeletal aches (2.1%). The prevalence of grade 3 or higher AEs was relatively low (4.2%), and no treatment-associated interstitial lung disease was depicted. In the AENEAS study, which followed multiple system-related AEs, 2 patients (0.9%) had treatment-related interstitial lung disorder [11]. The most common AEs of osimertinib are leukopenia, anemia, thrombocytopenia, diarrhea, neutropenia, and weight loss [15]. The most common adverse reactions of furmonertinib include elevated alanine aminotransferase, diarrhea, elevated aspartate aminotransferase, rash, etc. [16]. However, no new AEs related to the hematological system or diarrhea were observed in this study and no long-term toxicity was observed in relation to the heart, lungs, etc. It was also predicted that the study failed to show significant differences consistent with previous studies due to the small (limited) sample size.

This study has several limitations. The retrospective nature of the study and small (limited) sample size may have influenced the interpretation of the efficacy and safety results. The current toxicity evaluation was partly based on telephone follow-ups, potentially affecting the accuracy of recording adverse reactions relative to the prospective clinical trials.

This study retrospectively analyzed the long-term efficacy and safety of first-line aumolertinib for treating advanced NSCLC with EGFR mutations in the real world setting. Our research revealed that patients with the L858R mutation demonstrated poorer prognosis compared to those with the exon 19 deletion. Despite the small sample size, we still observed a trend toward poor prognosis in patients with brain metastases and TP53 mutations. First-line treatment with aumolertinib for EGFR-mutated NSCLC demonstrated safety and efficacy, which were consistent with other EGFR TKIs. Additionally, it had a relatively low incidence of adverse events in the real world.

Acknowledgement: We thank all the participants who volunteered their time to take part in this study.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 82260498 and 82160471), Quzhou City Qujiang District Life Oasis Public Welfare Service Center; Health Development Promotion Project—Cancer Research Project (grant no. BJHA-CRP-033), Guangxi Medical and Health Key Discipline Construction Project, 2021 Guilin City Science Research and Technology Development Plan Project (grant no. 20210227-7-9) and Beijing Xisike Clinical Oncology Research Foundation (grant no. Y-QL202101-0214).

Author Contributions: Study conception and design: Jingzhang Li, Quanfang Chen, Feng Xue; data collection: Lin Zhu, Zhuchun Jiang, Jing Zhang, Xinrong Hu; analysis and interpretation of results: Yunyan Mo, Dongning Huang; draft manuscript preparation: Xi Qin, Yulan Liu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The original data underpinning the conclusion of this article will be provided by the corresponding author as needed.

Ethics Approval: This retrospective study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Guilin Medical University (Guilin, China; approval no. 2022IITLL-05-G1). Informed consent has been obtained from all patients enrolled in this study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Leiter A, Veluswamy RR, Wisnivesky JP. The global burden of lung cancer: current status and future trends. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2023;20(9):624–39. doi:10.1038/s41571-023-00798-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Zheng RS, Chen R, Han BF, Wang SM, Li L, Sun KX, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality in China, 2022. J Natl Cancer Cent. 2024;4(1):47–53. doi:10.1016/j.jncc.2024.01.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Reck M, Rodriguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, Hui R, Csoszi T, Fulop A, et al. Five-year outcomes with pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer with PD-L1 tumor proportion score ≥50. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(21):2339–49. doi:10.1200/jco.21.00174. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Cho BC, Chewaskulyong B, Lee KH, Dechaphunkul A, Sriuranpong V, Imamura F, et al. Osimertinib versus standard of care EGFR TKI as first-line treatment in patients with EGFRm advanced NSCLC: flaura Asian subset. J Thorac Oncol. 2019;14(1):99–106. doi:10.1016/j.jtho.2018.09.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Yang Z, Yang N, Ou Q, Xiang Y, Jiang T, Wu X, et al. Investigating novel resistance mechanisms to third-generation EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor osimertinib in non-small cell lung cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24(13):3097–107. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-17-2310. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Kobayashi S, Boggon TJ, Dayaram T, Janne PA, Kocher O, Meyerson M, et al. EGFR mutation and resistance of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(8):786–92. doi:10.1056/nejmoa044238. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Goss G, Tsai CM, Shepherd FA, Bazhenova L, Lee JS, Chang GC, et al. Osimertinib for pretreated EGFR Thr790Met-positive advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (AURA2a multicentre, open-label, single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(12):1643–52. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(16)30508-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Mok TS, Wu Y, Ahn M, Garassino MC, Kim HR, Ramalingam SS, et al. Osimertinib or platinum-pemetrexed in EGFR T790M-positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(7):629–40. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1612674. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Ramalingam SS, Vansteenkiste J, Planchard D, Cho BC, Gray JE, Ohe Y, et al. Overall survival with osimertinib in untreated, EGFR-mutated advanced NSCLC. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(1):41–50. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1913662. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Shirley M, Keam SJ. Aumolertinib: a review in non-small cell lung cancer. Drugs. 2022;82(5):577–84. doi:10.1007/s40265-022-01695-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Lu S, Dong X, Jian H, Chen J, Chen G, Sun Y, et al. AENEAS: a randomized phase III trial of aumolertinib versus gefitinib as first-line therapy for locally advanced or metastaticnon-small-cell lung cancer with EGFR exon 19 deletion or L858R mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(27):3162–71. doi:10.1200/jco.21.02641. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Li XM, Li WF, Lin JT, Yan HH, Tu HY, Chen HJ, et al. Predictive and prognostic potential of TP53 in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer treated with EGFR-TKI: analysis of a phase III randomized clinical trial (CTONG 0901). Clin Lung Cancer. 2021;22(2):100–9. doi:10.1016/j.cllc.2020.11.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Qin Z, Zhang H, Yan P, Yu L, Hong C, Calvetti L, et al. Aumolertinib in NSCLC with leptomeningeal involvement, harbouring concurrent EGFR exon 19 deletion and TP53 comutation: a case report. J Thorac Dis. 2023;15(7):4016–26. doi:10.21037/jtd-23-841. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(2):228–47. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Soria JC, Ohe Y, Vansteenkiste J, Reungwetwattana T, Chewaskulyong B, Lee KH, et al. Osimertinib in untreated EGFR-mutated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(2):113–25. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1713137. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Shi Y, Chen G, Wang X, Liu Y, Wu L, Hao Y, et al. Furmonertinib (AST2818) versus gefitinib as first-line therapy for Chinese patients with locally advanced or metastatic EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (FURLONGa multicentre, double-blind, randomised phase 3 study. Lancet Resp Med. 2022;10(11):1019–28. doi:10.1016/s2213-2600(22)00168-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Niu W, Ge X, Huang F, Pang J, et al. Experimental study of almonertinib crossing the blood-brain barrier in EGFR-mutant NSCLC brain metastasis and spinal cord metastasis models. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:750031. doi:10.3389/fphar.2021.750031. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Lorenzi M, Ferro A, Cecere F, Scattolin D, Del CA, Follador A, et al. First-line osimertinib in patients with EGFR-mutant advanced non-small cell lung cancer: outcome and safety in the real world: flower study. Oncologist. 2022;27(2):87–115. doi:10.1002/onco.13951. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Zhou J, Ben S. Comparison of therapeutic effects of EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitors on 19Del and L858R mutations in advanced lung adenocarcinoma and effect on cellular immune function. Thorac Cancer. 2018;9(2):228–33. doi:10.1111/1759-7714.12568. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Cheng Y, Mok TS, Zhou X, Lu S, Zhou Q, Zhou J, et al. Safety and efficacy of first-line dacomitinib in Asian patients with EGFR mutation-positive non-small cell lung cancer: results from a randomized, open-label, phase 3 trial (ARCHER 1050). Lung Cancer. 2021;154(25):176–85. doi:10.1016/j.lungcan.2021.02.025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Yamamoto N, Seto T, Nishio M, Goto K, Yamamoto N, Okamoto I, et al. Erlotinib plus bevacizumab vs erlotinib monotherapy as first-line treatment for advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-squamous non-small-cell lung cancer: survival follow-up results of the randomized JO25567 study. Lung Cancer. 2021;151:20–4. doi:10.1016/j.lungcan.2020.11.020. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Kenmotsu H, Wakuda K, Mori K, Kato T, Sugawara S, Kirita K, et al. Randomized phase 2 study of osimertinib plus bevacizumab vs. osimertinib for untreated patients with nonsquamous NSCLC harboring EGFR mutations: WJOG9717L study. J Thorac Oncol. 2022;17(9):1098–108. doi:10.1016/j.jtho.2022.05.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Passaro A, Wang J, Wang Y, Lee SH, Melosky B, Shih JY, et al. Amivantamab plus chemotherapy with and without lazertinib in EGFR-mutant advanced NSCLC after disease progression on osimertinib: primary results from the phase III MARIPOSA-2 study. Ann Oncol. 2024;35(1):77–90. doi:10.1016/j.annonc.2023.11.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Wang K, Du R, Myall NJ, Lewis WE, Uy N, Hong L, et al. Real-world efficacy and safety of amivantamab for EGFR-mutant NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol. 2024;19(3):500–6. doi:10.1016/j.jtho.2023.11.020. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Planchard D, Janne PA, Cheng Y, Yang JC, Yanagitani N, Kim SW, et al. Osimertinib with or without chemotherapy in EGFR-mutated advanced NSCLC. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(21):1935–48. doi:10.1056/nejmoa2306434. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Wang Z, Cheng Y, An T, Gao H, Wang K, Zhou Q, et al. Detection of EGFR mutations in plasma circulating tumour DNA as a selection criterion for first-line gefitinib treatment in patients with advanced lung adenocarcinoma (BENEFITa phase 2, single-arm, multicentre clinical trial. Lancet Resp Med. 2018;6(9):681–90. doi:10.1016/s2213-2600(18)30264-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Vokes NI, Chambers E, Nguyen T, Coolidge A, Lydon CA, Le X, et al. Concurrent TP53 mutations facilitate resistance evolution in EGFR-mutant lung adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Oncol. 2022;17(6):779–92. doi:10.1016/j.jtho.2022.02.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Wang H, Guo M, Wei H, Chen Y. Targeting p53 pathways: mechanisms, structures, and advances in therapy. Signal Transduct Tar. 2023;8(1):92. doi:10.1038/s41392-023-01347-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Zhao L, Wang Z, Du H, Chen S, Wang P. Lung adenocarcinoma patient harboring EGFR-KDD achieve durable response to Afatinib: a case report and literature review. Front Oncol. 2021;11:605853. doi:10.3389/fonc.2021.605853. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Soria JC, Felip E, Cobo M, Lu S, Syrigos K, Lee KH, et al. Afatinib vs. erlotinib as second-line treatment of patients with advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the lung (LUX-Lung 8an open-label randomised controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(8):897–907. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(15)00006-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Jin R, Peng L, Shou J, Wang J, Jin Y, Liang F, et al. EGFR-mutated squamous cell lung cancer and its association with outcomes. Front Oncol. 2021;11:680804. doi:10.3389/fonc.2021.680804. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools