Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Early GLP-1 Agonist Use and Cancer Risk in Type 2 Diabetes: A Real-World Data Cohort Study

1 Institute of Medicine, Chung Shan Medical University, Taichung, 402, Taiwan

2 Department of Emergency Medicine, School of Medicine, Chung Shan Medical University, Taichung, 402, Taiwan

3 Department of Emergency Medicine, Chung Shan Medical University Hospital, Taichung, 402, Taiwan

4 Department of Internal Medicine, Zuoying Armed Forces General Hospital, Kaohsiung, 813, Taiwan

5 Department of Emergency Medicine, Tri-Service General Hospital, National Defense Medical Center, Taipei, 114, Taiwan

6 Graduate Institute of Aerospace and Undersea Medicine, College of Biomedical Sciences, National Defense Medical University, Taipei, 114, Taiwan

7 Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Chung Shan Medical University Hospital, Taichung, 402, Taiwan

8 School of Medicine, Chung Shan Medical University, Taichung, 402, Taiwan

9 Department of Medical Research, Chung Shan Medical University Hospital, Taichung, 402, Taiwan

* Corresponding Authors: Yu-Hsun Wang. Email: ; Chao-Bin Yeh. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Therapeutic Challenges in Targeting Cell Death)

Oncology Research 2026, 34(1), 12 https://doi.org/10.32604/or.2025.072875

Received 05 September 2025; Accepted 29 October 2025; Issue published 30 December 2025

Abstract

Background: To determine whether initiating a glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist (GLP-1 RA) within 3 months of type 2 diabetes (T2DM) diagnosis alters the subsequent risk of overall and site-specific cancer and whether this association differs by baseline body-mass index (BMI). Methods: This retrospective cohort study used electronic health records from the TriNetX U.S. research network. Adults aged 20 years or older diagnosed with T2DM between 2016 and 2024 were included if they received any hypoglycemic agents within 3 months before and after diagnosis. Following 1:1 propensity score matching, both the GLP-1 RA user and non-user groups included 183,264 patients. The study outcome was defined as a diagnosis of malignant neoplasms. Hazard ratios (HRs) for overall and site-specific cancer risk were estimated using Cox proportional hazards models. Kaplan–Meier analysis and stratified analysis by BMI were performed. Results: Early GLP-1 RA use demonstrated a modest but significant association with reduced overall cancer risk (HR 0.93; 95% CI: 0.90–0.96). Reduced risks were noted for cancers of the digestive (HR 0.81), respiratory (HR 0.66), and female genital (HR 0.87) systems. In stratified analysis, benefits were more pronounced in patients with BMI ≥ 30, particularly for pancreatic and colorectal cancers. Conclusion: Early initiation of GLP-1 receptor agonists in patients with diagnosed T2DM was associated with a modest reduction in overall cancer risk, particularly among individuals with obesity. These findings highlight the dual metabolic and oncologic value of prompt GLP-1 RA therapy.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist (GLP-1 RA) is a class of incretin-based therapies widely used in the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). By mimicking endogenous GLP-1, these agents enhance glucose-dependent insulin secretion, suppress glucagon release, delay gastric emptying, and promote satiety [1,2]. GLP-1 effects are mediated through the GLP-1 receptor (GLP-1R), a G-protein coupled receptor expressed not only in pancreatic β-cells but also in the cardiovascular system, adipose tissue, and central nervous system. Activation of GLP-1R supports glucose homeostasis while also influencing weight regulation, appetite, and cardiovascular function, underscoring its physiological relevance beyond glycemic control [3]. Upon receptor activation, GLP-1 elevates intracellular cAMP, which activates protein kinase A (PKA) and EPAC (Exchange Protein directly Activated by cAMP), thereby facilitating insulin secretion and attenuating glucagon release. In addition, GLP-1 signaling engages the PI3K/AKT pathway, which is essential for β-cell survival and function, and can also activate MAPK/ERK cascades involved in cell growth and proliferation [3,4]. By addressing both hyperglycemia and excess body weight, GLP-1 RA have become a cornerstone in the treatment of patients with T2DM, particularly those with concurrent obesity [2,5]. Beyond glycemic control, GLP-1 RA have demonstrated cardiovascular benefits in numerous large-scale randomized controlled trials. [6] Agents such as liraglutide, semaglutide, and dulaglutide have been associated with reductions in major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) and cardiovascular mortality [7–9]. These findings have expanded the therapeutic role of GLP-1 RA to include cardiovascular risk reduction in patients with T2DM.

Despite these favorable outcomes, concerns remain regarding the long-term safety of GLP-1 RA, particularly their potential oncogenic effects. Preclinical rodent studies have shown that GLP-1 receptor activation can stimulate thyroid C-cell proliferation, raising concerns about the risk of medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC). Supporting this theoretical risk, some epidemiological studies have suggested a possible association between prolonged GLP-1 RA exposure and an increased risk of thyroid malignancies, including MTC [10,11]. In contrast, a recent large multisite cohort study across six countries found no significant association between GLP-1 RA use and thyroid cancer compared with DPP-4 inhibitors (HR 0.81; 95% CI, 0.59–1.12), and no dose–response relationship was observed [12]. In addition to thyroid cancer, observational and pharmacovigilance studies have investigated potential associations between GLP-1 RA use and other malignancies—including pancreatic, colorectal, and breast cancers—with inconsistent results [13–15]. Some studies suggest protective effects, while others raise concerns about increased risk. However, many of these findings are complicated by population heterogeneity, underlying comorbidities, and differences in study design.

Given the growing use of GLP-1 RA in both diabetic and non-diabetic populations (e.g., for obesity management), it is important to critically evaluate their potential association with cancer risk. Importantly, there has been a shift in clinical practice toward initiating these agents earlier in the T2DM disease course. Previously, GLP-1 RA were typically introduced several years after diagnosis; now, they are often prescribed within months of diagnosis. However, the oncologic implications of such early use remain poorly understood. Accordingly, the present study seeks to explore the association between early initiation of GLP-1 RA therapy—defined as within three months of T2DM diagnosis—and the subsequent risk of developing cancer, with particular focus on site-specific malignancies potentially influenced by GLP-1 receptor signaling. We also conducted stratified analyses by body mass index (BMI) to assess whether the relationship between GLP-1 RA use and cancer risk differs according to obesity status.

This retrospective cohort study leverages electronic health records from TriNetX, which includes data from approximately 126 million patients within the United States collaborative network. Data were extracted and analyzed on 18 April 2025, and the database is broadly representative of patients receiving care in participating institutions across the U.S. The anonymized data, collected from a variety of healthcare institutions such as hospitals, primary care providers, and specialty providers, encompasses demographic information, diagnoses (using the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification; ICD-10-CM), medications (standardized by RxNorm for prescriptions and Vaccine Administered Code; CVX for vaccines), procedures (using the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Procedure Coding System; ICD-10-PCS, and Current Procedural Terminology; CPT), and laboratory results (using Logical Observation Identifier Names and Codes; LOINC). This study, which is exempt from informed consent requirements, involves secondary analysis of pre-existing, de-identified data. The de-identification process complies with the standards set forth in Section §164.514(a) of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Privacy Rule and has been validated by a qualified expert as specified in Section §164.514(b) [16]. The study received approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Chung Shan Medical University Hospital (IRB number: CS2-23180), which conforms to the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2 Study Participants and Main Outcome

Fig. 1 illustrates the flowchart detailing the construction of the study cohort. The participants included adults aged 20 years or older who had been diagnosed withT2DM (ICD-10-CM: E11) between 2016 and 2024. Individuals with a prior diagnosis of type 1 diabetes mellitus (ICD-10-CM: E10) were excluded. To ensure the accuracy of the diagnosis, only subjects who had used hypoglycemic agents within three months before and after the T2DM diagnosis were included.

Figure 1: Flowchart illustrating participant selection. T2DM: type 2 diabetes mellitus, GLP-1 RA: glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist, PSM: propensity score matching, BMI: body mass index

The exposure group was defined as individuals who had used GLP-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RA, ATC: A10BJ) within three months of their T2DM diagnosis, while the non-exposure group consisted of those who had never used GLP-1 RA after their T2DM diagnosis. The index date was defined as the date of initial T2DM diagnosis.

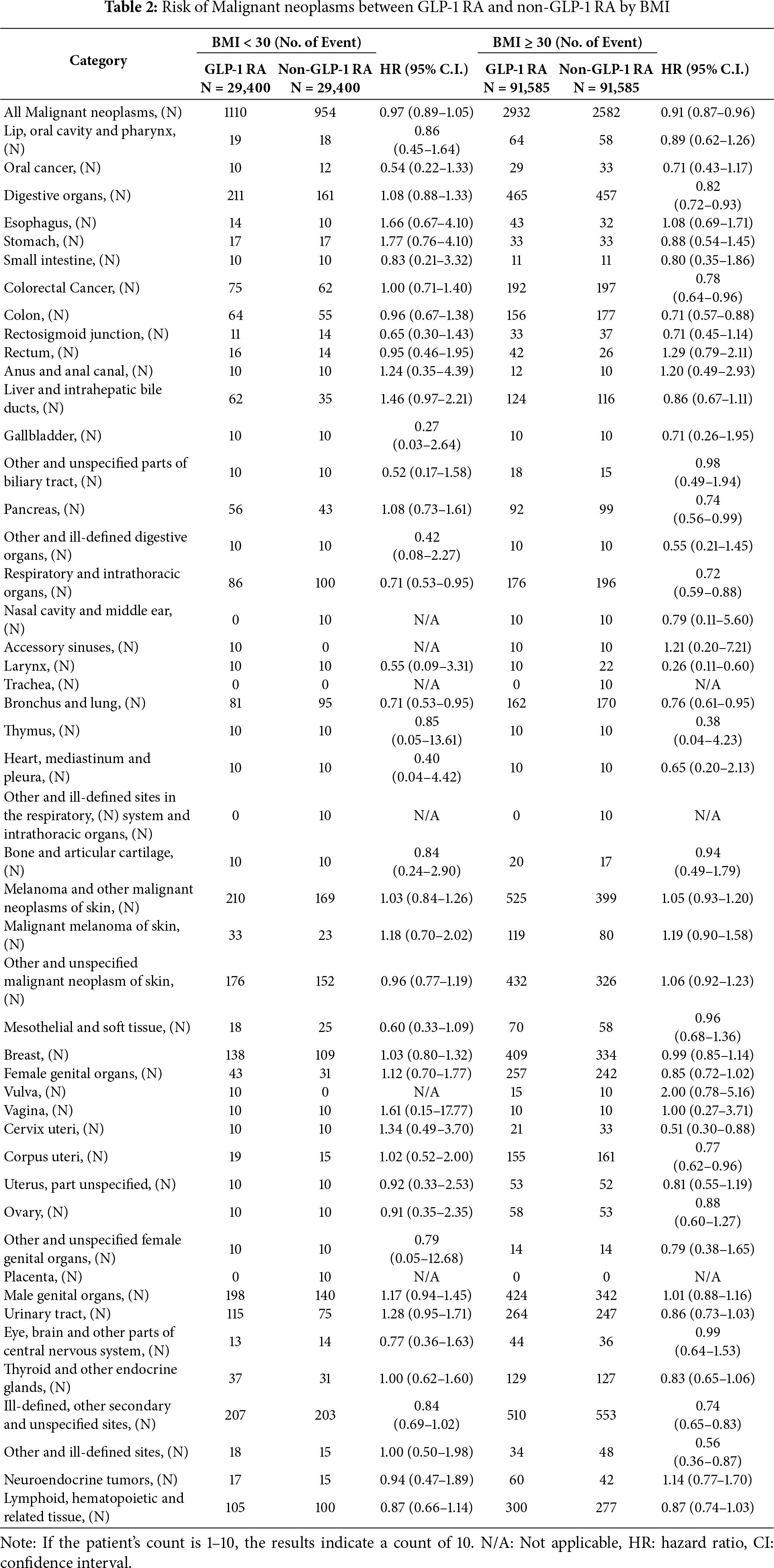

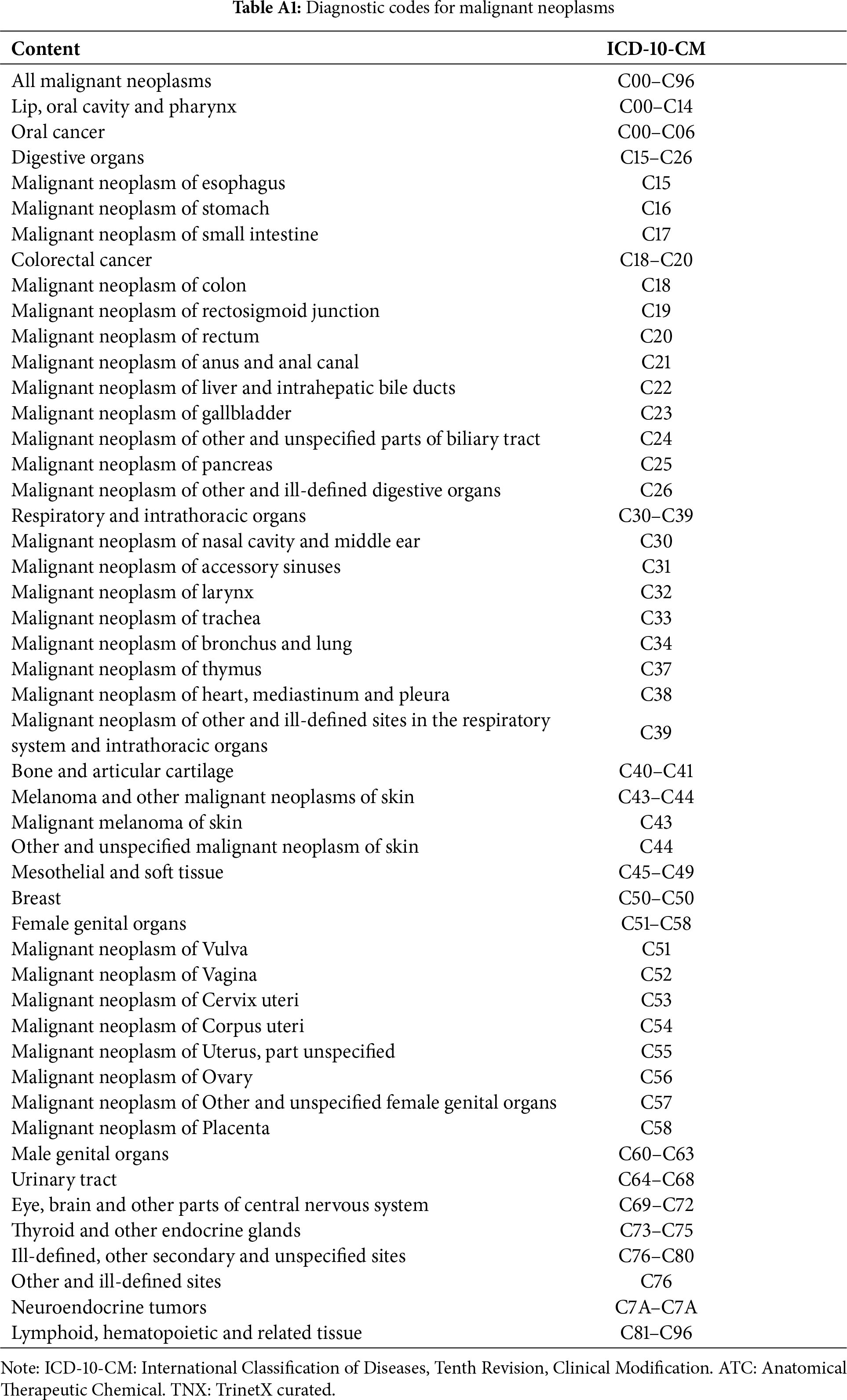

The study outcome was defined as a diagnosis of malignant neoplasms (Detailed codes are provided in Table A1). To ensure the identification of newly diagnosed outcomes, both groups excluded individuals who had been diagnosed with neoplasms (ICD-10-CM: C00–D49) before or within three months after their T2DM diagnosis.

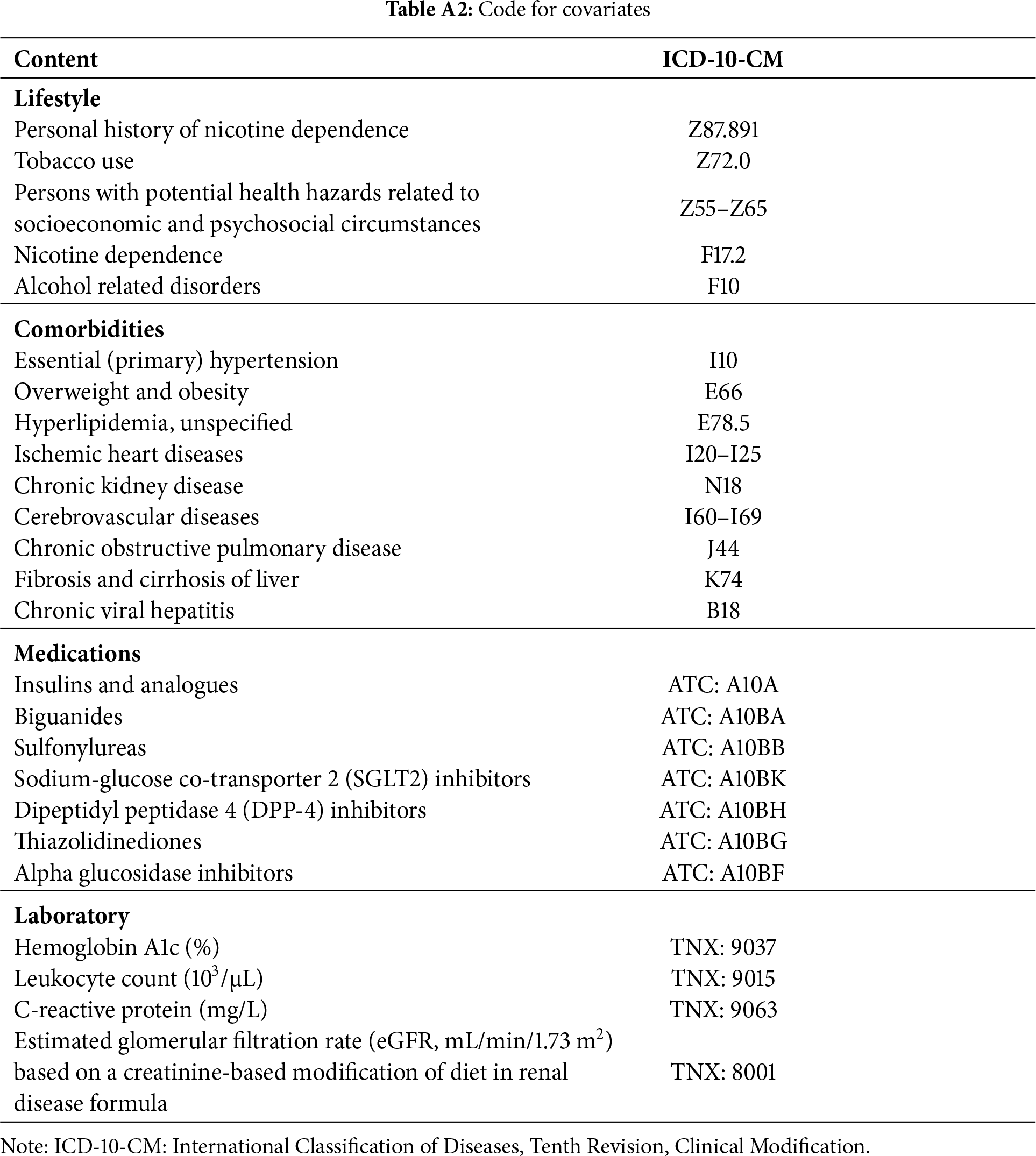

Baseline data were extracted from medical records covering the year preceding the index date up to the day before it. Demographic variables included age, sex, race, lifestyle factors, and body mass index (BMI). Information on healthcare utilization comprised records of outpatient, emergency department, and inpatient visits. Baseline comorbidities assessed included essential (primary) hypertension, overweight and obesity, unspecified hyperlipidemia, ischemic heart disease, chronic kidney disease, cerebrovascular disease, other chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases, liver fibrosis and cirrhosis, and chronic viral hepatitis. Medication use was evaluated for insulins and analogues, biguanides, sulfonylureas, sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors, thiazolidinediones, and alpha-glucosidase inhibitors. Laboratory measurements included hemoglobin A1c (%), leukocyte count (103/μL), C-reactive protein (mg/L), and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2) based on a creatinine-based modification of diet in renal disease (MDRD) formula. All relevant diagnostic and procedural codes are listed in Table A2.

To address baseline differences and control for confounding variables, propensity score matching (PSM) was conducted in a 1:1 ratio using TriNetX’s built-in functionality. The matching process accounted for variables including age, sex, race, lifestyle factors, body mass index (BMI), healthcare utilization, comorbidities, medications, and laboratory values. A greedy nearest-neighbor algorithm with a caliper of 0.1 pooled standard deviations was utilized for the matching. The primary aim was to compare cancer risk. Follow-up began 91 days after the index date and continued until cancer occurred or the last available medical record was reached.

Baseline characteristics of the GLP-1 receptor agonist (GLP-1 RA) and non–GLP-1 RA cohorts were assessed using standardized mean differences (SMD), with an SMD <0.1 indicating adequate covariate balance. Continuous variables are reported as means with standard deviation (SD), whereas categorical variables are presented as frequencies and corresponding percentages. Missing values were acknowledged and handled according to the platform’s default procedures. To assess the risk of malignant neoplasms between the GLP-1 receptor agonist (GLP-1 RA) group and the non-GLP-1 RA group, Kaplan–Meier survival curves and Cox proportional hazards models were applied. Stratified analyses were additionally conducted by body mass index (BMI), examining subgroups with BMI < 30 and BMI ≥ 30 to further explore potential differences in cancer risk between the two cohorts. All statistical analyses were performed on the TriNetX platform, which utilizes R version 4.0.2 as its underlying analytic engine.

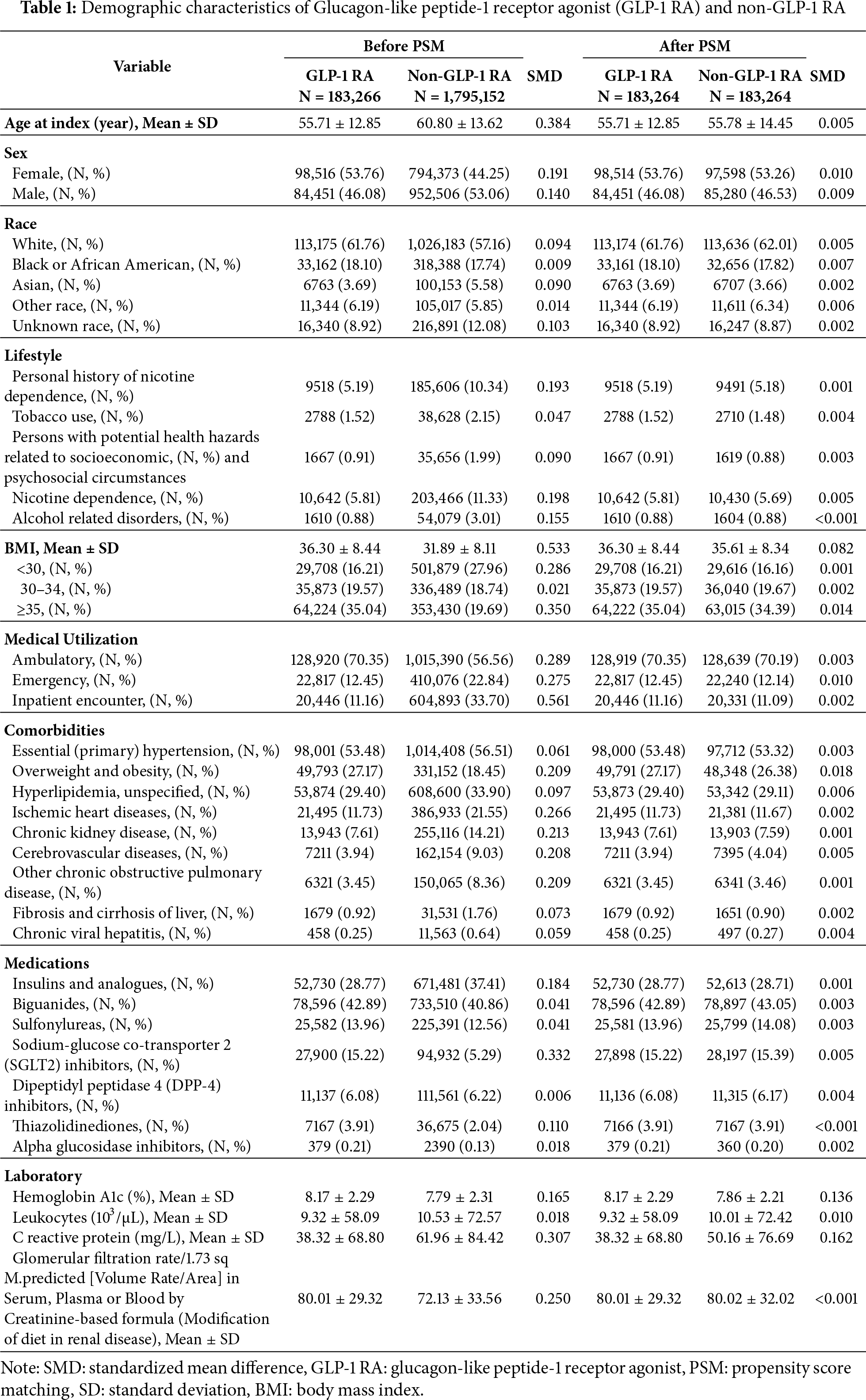

3.1 Study Cohort and Patient Characteristics

A total of 126,108,858 individuals were identified from the US collaborative network, from which 7,113,508 adults (≥20 years) diagnosed with T2DM between 2016 and 2024 were eligible for inclusion. After exclusion of individuals with prior neoplasms and type 1 diabetes, and after ensuring hypoglycemic medication use around diagnosis, the final analytical sample comprised 235,955 GLP-1 RA users and 2,365,766 non-users. Post 1:1 propensity score matching (PSM) on demographics, lifestyle, comorbidities, medication usage, and laboratory parameters, 183,264 subjects were included in both the GLP-1 RA and non-GLP-1 RA groups. Baseline characteristics were well balanced post-PSM, with all standardized mean differences (SMD) <0.1. The mean age was 55.7 years in both groups, with comparable sex, race, BMI categories, and clinical covariates. Prior to matching, the GLP-1 RA group had higher BMI and greater ambulatory healthcare utilization, and a lower prevalence of ischemic heart diseases, chronic kidney disease, cerebrovascular diseases, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; these differences were attenuated post-matching (Table 1).

3.2 Outcome: Risk of All Malignant Neoplasms

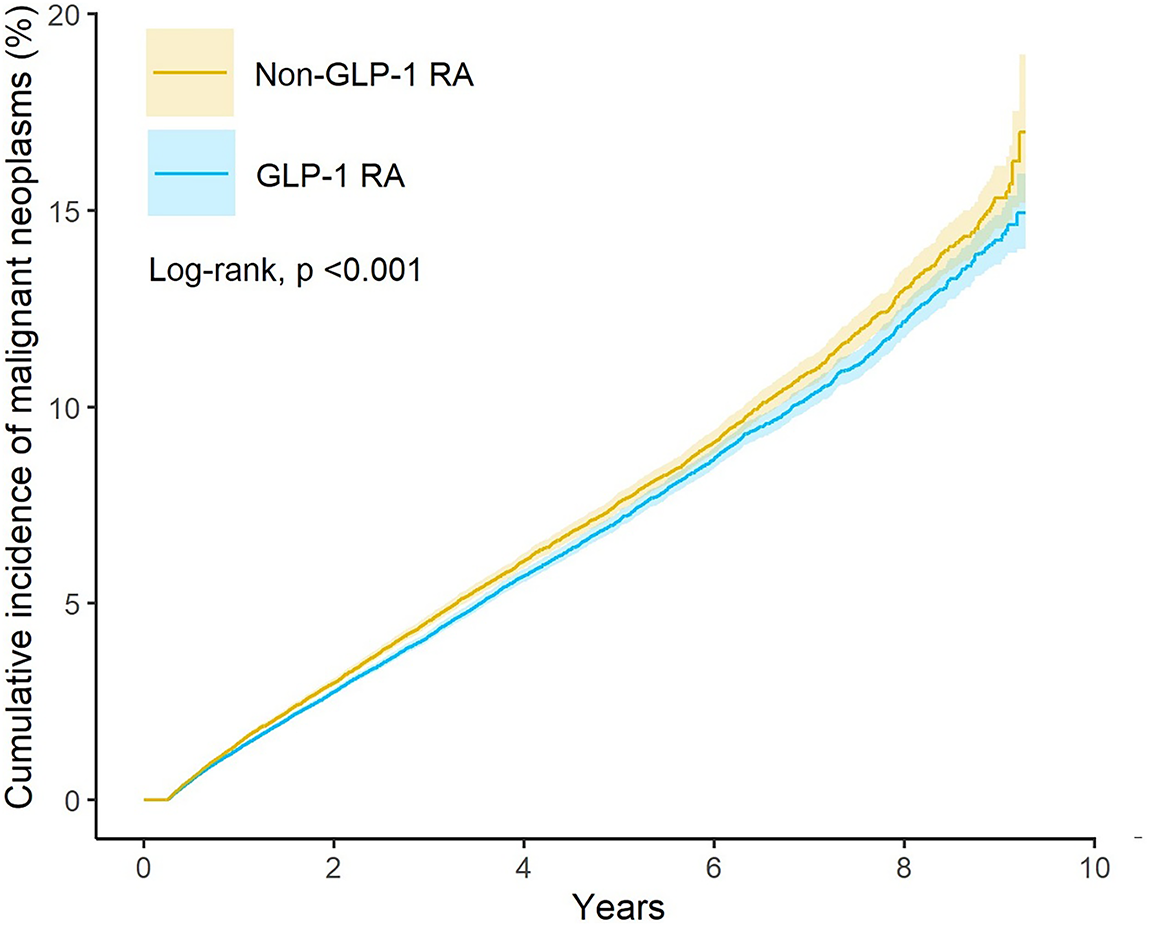

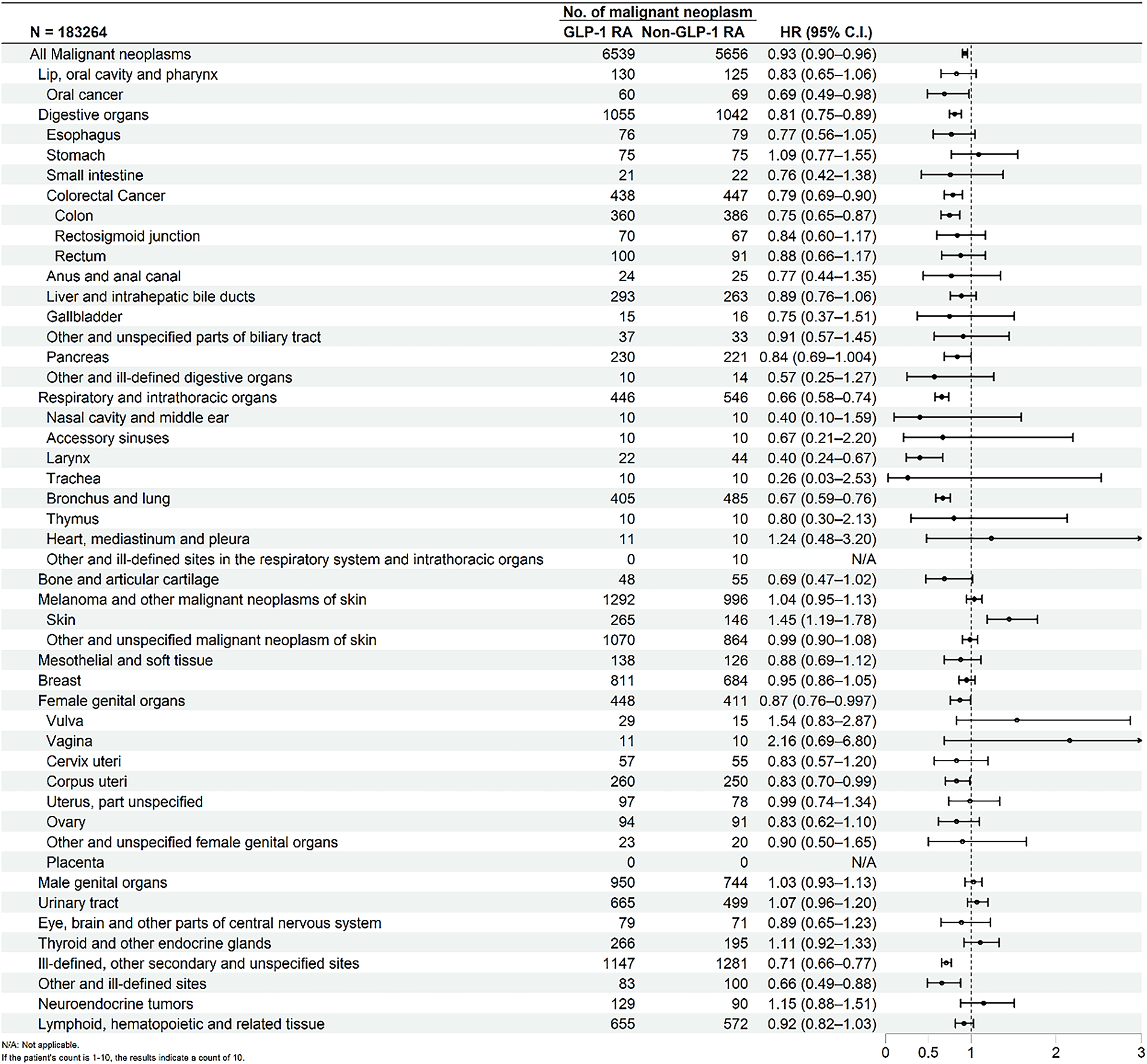

Fig. 2 presented the Kaplan-Meier curves depicting cumulative incidence of all malignant neoplasms over time between GLP-1 RA users and matched non-users. Log-rank testing confirmed that the difference in cumulative incidence of all malignant neoplasms was statistically significant. Fig. 3 presented the risk of malignant neoplasms between GLP-1 RA and non-GLP-1 RA groups, demonstrating a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.93 (95% CI: 0.90–0.96), which indicates a statistically significant reduction in the overall risk of cancer. Site-specific analyses revealed notably lower risks for cancers of the digestive system (HR: 0.81; 95% CI: 0.75–0.89), including colon cancer (HR: 0.75; 95% CI: 0.65–0.87), and for malignancies of the respiratory tract (HR: 0.66; 95% CI: 0.58–0.74), such as laryngeal cancer (HR: 0.40; 95% CI: 0.24–0.67) and bronchus and lung cancer (HR: 0.67; 95% CI: 0.59–0.76). Additional reductions in cancer risk were observed for malignancies of the female genital organs (HR: 0.87; 95% CI: 0.76–0.997) and oral cancer (HR: 0.69; 95% CI: 0.49–0.98). In contrast, GLP-1 RA use was associated with a significantly increased risk of malignant melanoma (HR: 1.45; 95% CI: 1.19–1.78).

Figure 2: Kaplan-Meier curves showing the risk of all malignant neoplasms over time in GLP-1 RA users and matched non-users

Figure 3: Forest plot comparing the risk of malignant neoplasms between GLP-1 RA users and non-users

3.3 Outcome: Stratified Analysis of Malignant Neoplasms

Table 2 presented the stratified analysis of cancer risk according to body mass index (BMI). Among individuals with BMI ≥ 30, GLP-1 RA use was associated with a significantly lower risk of overall malignancy (HR: 0.91; 95% CI: 0.87–0.96). Notable reductions were observed for cancers of the digestive system (HR: 0.82; 95% CI: 0.72–0.93), including pancreatic cancer (HR: 0.74; 95% CI: 0.56–0.99) and colorectal cancer (HR: 0.78; 95% CI: 0.64–0.96), as well as for respiratory tract cancers (HR: 0.72; 95% CI: 0.59–0.88). In contrast, among individuals with BMI < 30, no significant reduction in the overall risk of malignancy was observed (HR: 0.97; 95% CI: 0.89–1.05). However, a protective association remained evident for bronchus and lung cancer (HR: 0.71; 95% CI: 0.53–0.95).

As GLP-1 RA therapy has been adopted progressively earlier in the T2DM disease course, understanding its long-term safety—particularly oncologic outcomes—has become increasingly important. Previous evidence indicates that GLP-1 RA therapy was typically initiated a median of 6.1 years after T2DM diagnosis, reflecting delayed adoption in clinical practice [17]. However, growing evidence suggests that earlier initiation may lead to better glycemic outcomes and more durable long-term control [18,19]. Despite these metabolic benefits, the potential impact of early GLP-1 RA use on cancer risk remains unclear and warrants further investigation. This historical delay in GLP-1 RA initiation—often several years post-diagnosis—introduces potential confounding, as interim exposure to other antidiabetic agents may influence cancer risk. Consequently, isolating the specific effects of GLP-1 RA has been challenging. Our study aimed to specifically evaluate the impact of early initiation—defined as within three months of diagnosis—on subsequent cancer development. This design confers several methodological advantages. First, restricting GLP-1 RA exposure to the early disease stage minimizes exposure misclassification and ensures a consistent temporal sequence between treatment and cancer onset. Second, it helps mitigate reverse causality by reducing the likelihood that preclinical malignancies influenced treatment decisions. Together, these elements strengthen causal inference by upholding the core epidemiologic principle that exposure must precede outcome.

Compared with non-use, GLP-1 RA use was associated with a modest but statistically significant reduction in overall cancer incidence (hazard ratio [HR], 0.93; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.90–0.97). Subgroup analyses by cancer type revealed decreased risk for several malignancies, including cancers of the respiratory tract (HR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.45–0.89), digestive organs (HR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.72–0.89), and colorectum (HR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.66–0.96). The risk of pancreatic cancer was also modestly lower among GLP-1 RA users (HR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.69–1.00), although the upper bound of the confidence interval approached unity. In contrast, GLP-1 RA use was associated with an increased risk of malignant melanoma (HR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.01–1.70), while no statistically significant increase was observed for breast cancer (HR, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.94–1.15) or thyroid cancer (HR, 1.09; 95% CI, 0.88–1.34). The reduced risk of colorectal, digestive tract, and respiratory tract cancers among early GLP-1 RA users aligns with findings from several recent population-based studies [15,20,21]. Earlier observational studies had raised concerns about a potential increase in site-specific cancers—particularly thyroid, pancreatic, and breast malignancies—associated with GLP-1 RA exposure [10,22,23]. However, more recent large-scale cohort studies have not substantiated these associations, instead reporting neutral or null findings [12,24]. Our results support these more contemporary observations, showing no significant association in the risk of thyroid or breast cancer among early GLP-1 RA users.

The elevated risk of malignant melanoma observed in our cohort warrants cautious interpretation. To date, this association has not been consistently reported in the literature, and no well-established biological mechanism has been proposed. A recent population-based cohort study found no significant increase in the risk of melanoma (HR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.53–1.75) or non-melanoma skin cancers (HR, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.80–1.33) among GLP-1 RA users compared to sulfonylurea users [25]. This discrepancy may reflect differences in population characteristics, confounding control, or outcome ascertainment. Further research is needed to validate our findings and determine whether the observed signal reflects a true drug-related effect or residual bias. To further explore the heterogeneity of cancer risk reduction associated with GLP-1 RA use, we performed a stratified analysis based on BMI. Notably, the risk reduction in overall cancer incidence was more pronounced among individuals with BMI ≥ 30 (HR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.87–0.96), compared to those with BMI < 30 (HR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.89–1.05).

While our findings are broadly consistent with a recent nationwide analysis of GLP-1 RA use and cancer risk in individuals with obesity [26], our study provides additional insights by focusing on a clearly defined early exposure period within a diabetes-specific population. In contrast to the prior study, which enrolled obese individuals regardless of glycemic status, our analysis was limited to patients with confirmed T2DM, allowing for a more targeted assessment within the population for whom GLP-1 RA are primarily indicated. Similarly, a study by Wang et al., which focused on overweight and obese drug-naïve patients initiating antidiabetic therapy, found that GLP-1 RA were associated with a 50% lower risk of colorectal cancer compared to insulin, and a 42% lower risk compared to metformin during a median follow-up of 3 years [15]. Site-specific analyses showed a significant reduction in digestive organ cancers (HR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.72–0.93) and pancreatic cancer (HR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.56–0.99) in the higher BMI subgroup, whereas no such benefit was observed in the lower BMI group. These findings suggest that the potential antineoplastic effects of GLP-1 RA may be more pronounced in individuals with obesity, potentially reflecting the compounds’ dual metabolic and weight-reducing properties.

Several biological mechanisms may provide plausible explanations for the associations observed in our study. From a mechanistic perspective, GLP-1 RA activates the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling cascade, a pathway that is indispensable for pancreatic β-cell survival and glucose homeostasis, yet simultaneously represents a canonical oncogenic axis [3]. This dual role highlights the necessity of carefully evaluating the long-term oncologic safety of GLP-1 RA in clinical populations.

Emerging evidence further indicates that GLP-1 RA can modulate the gut microbiota, promoting the expansion of beneficial genera [27,28]. As dysbiosis of the gut microbiome has been implicated in chronic inflammation and tumorigenesis, these observations suggest that microbiota–immune interactions may represent an additional pathway through which GLP-1 RA influences cancer risk.

Furthermore, GLP-1 RA exhibit immunomodulatory properties, including the suppression of nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) activation, reductions in pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and IL-6, and the promotion of IL-10 secretion through T cell and microglial regulation [29,30]. Together, these pleiotropic effects provide a biologically plausible framework linking GLP-1 RA to cancer-related outcomes. Diabetes is increasingly recognized as a chronic inflammatory condition. A recent meta-analysis identified the ICAM-1 rs5498 polymorphism as a risk factor for T2DM, particularly in Asian populations [31], underscoring the role of immune–inflammatory pathways in diabetes pathogenesis.

In addition to these general mechanisms, the more pronounced cancer risk reduction observed in individuals with obesity may be explained by several factors. First, patients with elevated BMI inherently carry a higher baseline risk for various malignancies, including colorectal, pancreatic, and liver cancers [32,33]. Recent evidence demonstrates that obesity impairs CD8+ T cell function within the tumor microenvironment, leading to compromised immune surveillance and inefficient immunoediting, thereby increasing susceptibility to malignancy [34]. Key pathways linking obesity and cancer include PI3K/Akt/mTOR and JAK/STAT3 activation. More recent concepts further implicate the kynurenine–aryl hydrocarbon receptor axis and serine protease–mediated degradation of dependence receptors such as deleted in colorectal cancer and neogenin as additional routes promoting carcinogenesis [35]. Second, beyond glycemic control, GLP-1 RA exert metabolic and anti-inflammatory effects—such as weight reduction, improved insulin sensitivity, and lowered systemic inflammation—that are particularly relevant in the context of obesity [36]. Lastly, obese individuals may exhibit greater physiological responsiveness to GLP-1 RA, achieving more substantial reductions in body weight and metabolic burden, which could synergistically enhance the compounds’ potential antineoplastic effects.

Beyond clinical implications, our findings should be viewed within the broader context of medical innovation and health system resilience. The concept of health system resilience has been increasingly elaborated in recent literature, highlighting how governance, adaptability, and institutional networks enable systems to withstand shocks and sustain essential services under stress [37–39]. In parallel, the rapid adoption of GLP-1 RA illustrates how novel therapies can shape both patient outcomes and healthcare sustainability.

At the individual level, the heterogeneity of cancer risk reduction—particularly the more pronounced effects observed in patients with obesity—underscores the importance of precision medicine. Potential biomarkers such as BMI, systemic inflammatory markers, genetic variations (e.g., ICAM-1 polymorphisms), and gut microbiota composition could inform stratification strategies in future studies. Incorporating these factors into trial design and clinical practice may enable more individualized risk–benefit assessments, ensuring that GLP-1 RA are deployed not only for metabolic control but also as part of tailored strategies to mitigate diabetes-associated cancer risk.

Diverse limitations should be acknowledged in the interpretation of these results. First, although propensity score matching was applied to balance baseline characteristics, some covariates (e.g., HbA1c [SMD 0.136] and CRP [SMD 0.162]) remained slightly imbalanced. In addition, residual confounding from unmeasured variables—such as family history of cancer, lifestyle factors (including diet and physical activity), and environmental exposures—cannot be excluded. Second, the TriNetX platform lacks detailed information on medication adherence, dosage, and duration, limiting the ability to assess dose-response relationships or the effects of long-term GLP-1 RA exposure. Third, cancer outcomes were identified using ICD-10 codes, which may be subject to misclassification or underreporting, particularly for early-stage or subclinical cancers. Fourth, because the data were derived from U.S.-based health care institutions within the TriNetX network, the generalizability of these findings to other populations or health systems may be limited. Finally, as an observational study, causal inference cannot be established. The observed associations between GLP-1 RA use and cancer risk may be influenced by indication bias or other clinical decision-making factors not captured in the database.

In conclusion, early initiation of GLP-1 receptor agonist was associated with a reduced overall cancer risk, particularly for digestive, respiratory, and female-genital malignancies. These agents also provide significant weight-loss benefits, which may contribute to their protective effect. The risk reduction was especially evident in individuals with obesity, highlighting the dual metabolic and oncologic advantages of timely treatment.

Acknowledgement: This study was conducted using data obtained from the TriNetX research network. The authors acknowledge TriNetX, LLC, for providing access to the platform and data resources. The authors used ChatGPT (OpenAI, model o3, accessed May 2025) solely for language polishing of early drafts; all AI-generated text was reviewed, edited, and verified by the authors.

Funding Statement: This project received financial support from the Chung Shan Medical University Hospital, Taiwan (CSH-2022-A-009).

Author Contributions: Study conception and design: Cheng-Hsun Chuang, Chao-Bin Yeh; draft manuscript preparation: Cheng-Hsun Chuang, Ping-Kun Tsai, Shih-Wen Kao, Yu-Hsun Wang, Chao-Bin Yeh; review and editing: Cheng-Hsun Chuang, Ping-Kun Tsai, Shih-Wen Kao, Yu-Hsun Wang, Chao-Bin Yeh; visualization: Yu-Hsun Wang; supervision: Chao-Bin Yeh. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Research data supporting this publication can be accessed through the TriNetX platform, available at https://trinetx.com/. Data sharing is not applicable to this article, as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Ethics Approval: Our protocol for the research project has been approved by the Institutional Review Board of Chung Shan Medical University Hospital (IRB number: CS2-23180), which conforms to the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent: The requirement for informed consent was waived due to the use of de-identified electronic health records.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| BMI | Body mass index |

| GLP-1 RA | Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist |

| HR | Hazard ratio |

| PSM | Propensity score matching |

| SGLT2 | Sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 |

| SMD | Standardized mean differences |

| T2DM | Type 2 diabetes |

Appendix A

References

1. Drucker DJ. Mechanisms of action and therapeutic application of Glucagon-like Peptide-1. Cell Metab. 2018;27(4):740–56. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2018.03.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Moiz A, Filion KB, Tsoukas MA, Yu OH, Peters TM, Eisenberg MJ. Mechanisms of GLP-1 receptor agonist-induced weight loss: a review of central and peripheral pathways in appetite and energy regulation. Am J Med. 2025;138(6):934–40. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2025.01.021. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Zheng Z, Zong Y, Ma Y, Tian Y, Pang Y, Zhang C, et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor: mechanisms and advances in therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9(1):234. doi:10.1038/s41392-024-01931-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Kaihara KA, Dickson LM, Jacobson DA, Tamarina N, Roe MW, Philipson LH, et al. β-cell-specific protein kinase a activation enhances the efficiency of glucose control by increasing acute-phase insulin secretion. Diabetes. 2013;62(5):1527–36. doi:10.2337/db12-1013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Yao H, Zhang A, Li D, Wu Y, Wang CZ, Wan JY, et al. Comparative effectiveness of GLP-1 receptor agonists on glycaemic control, body weight, and lipid profile for type 2 diabetes: systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2024;384:e076410. doi:10.1136/bmj-2023-076410. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Ussher JR, Drucker DJ. Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists: cardiovascular benefits and mechanisms of action. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2023;20(7):463–74. doi:10.1038/s41569-023-00849-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Gerstein HC, Colhoun HM, Dagenais GR, Diaz R, Lakshmanan M, Pais P, et al. Dulaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes: a double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2019;394(10193):121–30. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

8. Hernandez AF, Green JB, Janmohamed S, D’Agostino RB, Granger CB, Jones NP, et al. Albiglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease: a double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;392(10157):1519–29. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

9. Marso SP, Daniels GH, Brown-Frandsen K, Kristensen P, Mann JF, Nauck MA, et al. Liraglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(4):311–22. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1603827. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Bezin J, Gouverneur A, Pénichon M, Mathieu C, Garrel R, Hillaire-Buys D, et al. GLP-1 receptor agonists and the risk of thyroid cancer. Diabetes Care. 2023;46(2):384–90. doi:10.2337/dc22-1148. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Bjerre Knudsen L, Madsen LW, Andersen S, Almholt K, de Boer AS, Drucker DJ, et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists activate rodent thyroid C-cells causing calcitonin release and C-cell proliferation. Endocrinology. 2010;151(4):1473–86. doi:10.1210/en.2009-1272. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Baxter SM, Lund LC, Andersen JH, Brix TH, Hegedüs L, Hsieh MH, et al. Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists and risk of thyroid cancer: an international multisite cohort study. Thyroid. 2025;35(1):69–78. doi:10.1089/thy.2024.0387. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Dankner R, Murad H, Agay N, Olmer L, Freedman LS. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and pancreatic cancer risk in patients with type 2 diabetes. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(1):e2350408. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.50408. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Hicks BM, Yin H, Yu OH, Pollak MN, Platt RW, Azoulay L. Glucagon-like peptide-1 analogues and risk of breast cancer in women with type 2 diabetes: population based cohort study using the UK clinical practice research datalink. BMJ. 2016;355:i5340. doi:10.1136/bmj.i5340. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Wang L, Wang W, Kaelber DC, Xu R, Berger NA. GLP-1 receptor agonists and colorectal cancer risk in drug-naive patients with type 2 diabetes, with and without overweight/obesity. JAMA Oncol. 2024;10(2):256–8. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2023.5573. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Palchuk MB, London JW, Perez-Rey D, Drebert ZJ, Winer-Jones JP, Thompson CN, et al. A global federated real-world data and analytics platform for research. JAMIA Open. 2023;6(2):ooad035. doi:10.1093/jamiaopen/ooad035. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Boye KS, Stein D, Matza LS, Jordan J, Yu R, Norrbacka K, et al. Timing of GLP-1 receptor agonist initiation for treatment of type 2 diabetes in the UK. Drugs R D. 2019;19(2):213–25. doi:10.1007/s40268-019-0273-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Boye KS, Mody R, Lage MJ, Malik RE. The relationship between timing of initiation on a glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist and glycosylated hemoglobin values among patients with type 2 diabetes. Clin Ther. 2020;42(9):1812–7. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2020.06.019. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Rasalam R, Abdo S, Deed G, O’Brien R, Overland J. Early type 2 diabetes treatment intensification with glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists in primary care: an Australian perspective on guidelines and the global evidence. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2023;25(4):901–15. doi:10.1111/dom.14953. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Tabernacki T, Wang L, Kaelber DC, Xu R, Berger NA. Non-insulin antidiabetic agents and lung cancer risk in drug-naive patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a nationwide retrospective cohort study. Cancers. 2024;16(13):2377. doi:10.3390/cancers16132377. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Wang L, Xu R, Kaelber DC, Berger NA. Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists and 13 obesity-associated cancers in patients with type 2 diabetes. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(7):e2421305. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.21305. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Elashoff M, Matveyenko AV, Gier B, Elashoff R, Butler PC. Pancreatitis, pancreatic, and thyroid cancer with glucagon-like peptide-1-based therapies. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(1):150–6. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2011.02.018. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Liu Z, Duan X, Yuan M, Yu J, Hu X, Han X, et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor activation by liraglutide promotes breast cancer through NOX4/ROS/VEGF pathway. Life Sci. 2022;294(679–688):120370. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2022.120370. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Piccoli GF, Mesquita LA, Stein C, Aziz M, Zoldan M, Degobi NAH, et al. Do GLP-1 receptor agonists increase the risk of breast cancer? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106(3):912–21. doi:10.1210/jendso/bvab048.718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Pradhan R, Yu OHY, Platt RW, Azoulay L. Glucagon like peptide-1 receptor agonists and the risk of skin cancer among patients with type 2 diabetes: population-based cohort study. Diabet Med. 2024;41(4):e15248. doi:10.1111/dme.15248. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Levy S, Attia A, Elshazli RM, Abdelmaksoud A, Tatum D, Aiash H, et al. Differential effects of GLP-1 receptor agonists on cancer risk in obesity: a nationwide analysis of 1.1 million patients. Cancers. 2024;17(1):78. doi:10.3390/cancers17010078. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Everard A, Cani PD. Gut microbiota and GLP-1. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2014;15(3):189–96. doi:10.1007/s11154-014-9288-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Gofron KK, Wasilewski A, Małgorzewicz S. Effects of GLP-1 analogues and agonists on the gut microbiota: a systematic review. Nutrients. 2025;17(8):1303. doi:10.3390/nu17081303. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Lee YS, Jun HS. Anti-inflammatory effects of GLP-1-based therapies beyond glucose control. Mediat Inflamm. 2016;2016(1):3094642. doi:10.1155/2016/3094642. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Sun H, Hao Y, Liu H, Gao F. The immunomodulatory effects of GLP-1 receptor agonists in neurogenerative diseases and ischemic stroke treatment. Front Immunol. 2025;16:1525623. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2025.1525623. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Mi W, Xia Y, Bian Y. The influence of ICAM1 rs5498 on diabetes mellitus risk: evidence from a meta-analysis. Inflamm Res. 2019;68(4):275–84. doi:10.1007/s00011-019-01220-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Kyrgiou M, Kalliala I, Markozannes G, Gunter MJ, Paraskevaidis E, Gabra H, et al. Adiposity and cancer at major anatomical sites: umbrella review of the literature. BMJ. 2017;356:j477. doi:10.1136/bmj.j477. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Mahamat-Saleh Y, Aune D, Freisling H, Hardikar S, Jaafar R, Rinaldi S, et al. Association of metabolic obesity phenotypes with risk of overall and site-specific cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Br J Cancer. 2024;131(9):1480–95. doi:10.1038/s41416-024-02857-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Piening A, Ebert E, Gottlieb C, Khojandi N, Kuehm LM, Hoft SG, et al. Obesity-related T cell dysfunction impairs immunosurveillance and increases cancer risk. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):2835. doi:10.1038/s41467-024-47359-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Stone TW, McPherson M, Darlington LG. Obesity and cancer: existing and new hypotheses for a causal connection. eBioMedicine. 2018;30(S1):14–28. doi:10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.02.022. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Lin A, Ding Y, Li Z, Jiang A, Liu Z, Wong HZH, et al. Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists and cancer risk: advancing precision medicine through mechanistic understanding and clinical evidence. Biomark Res. 2025;13(1):50. doi:10.1186/s40364-025-00765-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Asfoor AD, Tabche C, Al-Zadjali M, Mataria A, Saikat S, Rawaf S. Concept analysis of health system resilience. Health Res Policy Syst. 2024;22(1):43. doi:10.1186/s12961-024-01114-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Hu F, Yang H, Qiu L, Wang X, Ren Z, Wei S, et al. Innovation networks in the advanced medical equipment industry: supporting regional digital health systems from a local-national perspective. Front Public Health. 2025;13:1635475. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2025.1635475. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Witter S, Thomas S, Topp SM, Barasa E, Chopra M, Cobos D, et al. Health system resilience: a critical review and reconceptualisation. Lancet Glob Health. 2023;11(9):e1454–8. doi:10.1016/s2214-109x(23)00279-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools