Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Chloroplast Genome Sequence Characterization and Phylogenetic Analysis of Pyrola Atropurpurea Franch

Department of Biological Technology, Nanchang Normal University, Nanchang, 330032, China

* Corresponding Author: Wentao Sheng. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Plant Genetic Diversity and Evolution)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(2), 331-345. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.061424

Received 24 November 2024; Accepted 14 January 2025; Issue published 06 March 2025

Abstract

Pyrola atropurpurea Franch is an important annual herbaceous plant. Few genomic analyses have been conducted on this plant, and chloroplast genome research will enrich its genomics basis. This study is based on high-throughput sequencing technology and Bioinformatics methods to obtain the sequence, structure, and other characteristics of the P. atropurpurea chloroplast genome. The result showed that the chloroplast genome of P. atropurpurea has a double-stranded circular structure with a total length of 172,535 bp and a typical four-segment structure. The genome has annotated a total of 132 functional genes, including 43 tRNAs, 8 rRNAs, 76 protein-coding genes, and 5 pseudo-genes. In total, 358 SSR loci were checked out, mainly composed of mononucleotide and trinucleotide repeat. There are three types of scattered repetitive sequences, totaling 4223, including 2452 forward repeats, 1763 palindrome repeats, and eight reverse repeats. The optimal codon usage frequency is relatively high with AT usage preference in this genome. Chloroplast genome comparative analysis in the family Ericaceae shows that the overall sequence is more complex, and there are more variations in the gene interval region. The collinearity analysis indicated that there is a complex rearrangement of species between different genera in Ericaceae. The selection pressure analysis showed that the protein-encoding genes rpl33 and rps16 were positively selected among the seven medicinal plants in Ericaceae. The maximum likelihood tree shows that the genetic relationship among P. atropurpurea, Pyrola rotundifolia, and Chimaphila japonica is relatively close. Therefore, an important data basis was provided for species identification, genetic diversity, and phylogenetic studies of P. atropurpurea and even this genus of plants.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileChloroplasts are organelles involved in photosynthesis and provide the necessary energy for plant life activities [1]. Chloroplasts have a relatively independent genetic system, consisting of a circular and structurally stable genome, known as the chloroplast genome [2,3]. In comparative analysis with the nuclear genome, the chloroplast DNA molecules are relatively small and generally between 115 and 165 kb in length [4]. Due to its high degree of conservatism and moderate evolutionary rate, chloroplast genomes have been widely utilized in plant discrimination, phylogenetic analysis, and genetic evolution research [5–7]. Chloroplast-based genetic engineering is playing an increasingly important role in germplasm resource protection and variety breeding. Currently, chloroplast genomes of commonly used ethnic Chinese medicinal materials such as Platycodon grandiflorus [8], Rubia cordifolia [9], and Cynanchum wallichii [10] have been reported one after another.

There are about 30 species of the genus Pyrola plants in the world, mainly distributed in the northern temperate and northern cold regions of the Earth [11]. This genus of plants has a wide variety in China, with a total of 27 species and 3 varieties, mainly distributed in the southwest and northeast regions. Among them, there are 17 species, and the three variants are unique plants of the genus Pyrola in China, including the common P. decorata, P. calliantha, and P. atropurpura. The plants of the genus Pyrola are widely used in Chinese folk herbal medicine and also play a very important role in Miao ethnic medicine and Tibetan medicine [12]. P. atropurpura is often used to treat muscle and bone pain, moisten the lungs, relieve cough, and nourish the liver and kidneys, and its research at home and abroad mainly focuses on the study of its chemical components [13,14]. Up to now, there are few reports on the chloroplast genome of plants in the genus Pyrola, and only 10 single nucleotide sequences of Pyrola were acquired from GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/?term=Pyrola%20atropurpurea) (accessed on 13 January 2025), the only chloroplast genome with Pyrola rotundifolia (KU833271.1) was registered in NCBI. In this study, we successfully assembled the P. atropurpura chloroplast genome, the genome structural characteristics, codon bias, repeat sequences, and phylogenetic information were deeply explored, in order to provide chloroplast genome information for the genetic background, molecular evolution, and phylogeny of P. atropurpura, and to promote the protection of P. atropurpura germplasm resources and genetic engineering research.

The P. atropurpura leaves were collected from the campus of Guizhou University (26°25′39.62″N, 106°40′5.81″E). Healthy and tender leaves were selected, washed 3–5 times with distilled water, dried, and stored in a −80°C refrigerator for later use.

2.2 Extraction, Sequencing, and Assembly of Chloroplast Genomic DNA

The leaves were rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen and ground into powder, then their genomic DNA was extracted using the modified CTAB method [15]. Preparation of 350 bp DNA fragments was done using a Covaris ultrasonic crusher, followed by end repair and tail addition. The construction of the sequencing library was completed and its sequencing was performed on the Illumina HiSeq X Ten platform using a Paired-End (PE) PE150 sequencing strategy. We obtained 6.75 G of raw data with high throughput sequencing, removed joints and low-quality data regions, and accumulated 27,130,560 clean reads. Using NOVOPlasty was to splice chloroplast genomes with default parameters [16].

2.3 Annotation of Chloroplast Genome

The annotation of the P. atropurpura chloroplast genome was performed using the Plastid Genome Annotator (https://github.com/quxiaojian/PGA) (accessed on 13 January 2025) [17], and manually adjusted; tRNA annotation was made using tRNAscan-SE (https://trna.ucsc.edu/tRNAscan-SE/) (accessed on 13 January 2025) and ARAGORN tools (https://packages.debian.org/bullseye/aragorn) (accessed on 13 January 2025); and a circle diagram was generated using Organellar Genome DRAW [18].

2.4 Codon Usage and Repeated Sequence Analysis

The CodonW1.4.2 software [19] was used to statistically analyze the codon preferences of the P. atropurpura chloroplast genome. Using the Reputer software [20], scattered repeat sequences were detected, with a minimum 30 bp repeat length, a minimum permutation value of 50, and a maximum base mismatch of 3. MISA software [21] was made to analyze simple repetitive sequences in the P. atropurpura chloroplast genome, the minimum repeat value for single nucleotides was set to 10, for dinucleotides to five, for trinucleotides to four, and tetra-, penta-, and hexanucleotides to three.

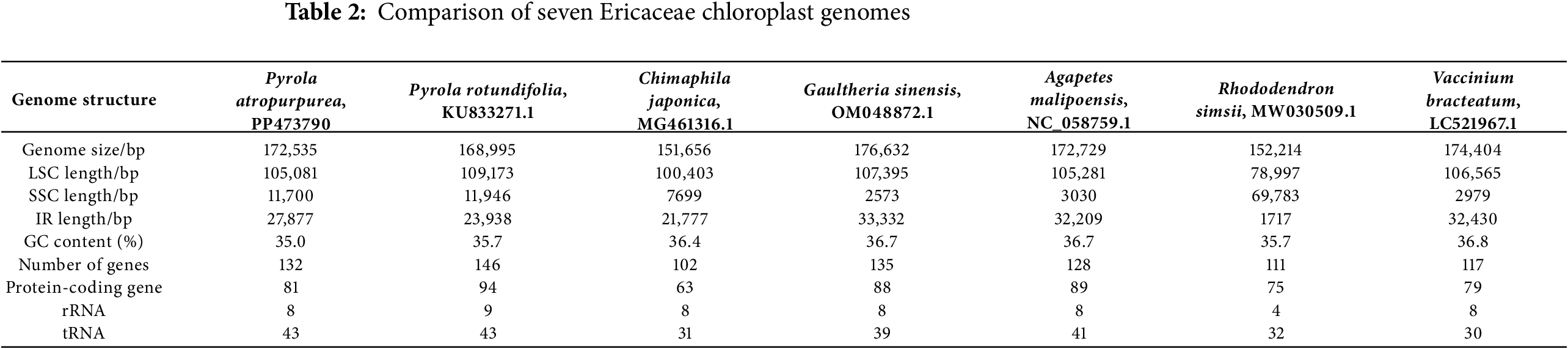

2.5 Chloroplast Genome Comparison of the Family Ericaceae

The chloroplast sequences of seven representative Chinese medicinal plants from the family Ericaceae, including Pyrola atropurpurea (PP473790), Pyrola rotundifolia (KU833271.1), Chimaphila japonica (MG461316.1), Gaultheria sinensis (OM048872.1), Agapetes malipoensis (NC_058759.1), Rhododendron simsii (MW030509.1), and Vaccinium bracteatum (LC521967.1) were downloaded from GenBank. The contraction and expansion of LSC, SSC, and IR region boundaries were visualized in the Ericaceae chloroplast genomes using IRscope software [22]. The chloroplast genome rearrangement and collinearity in Ericaceae species were detected using the Mauve multiplex genome alignment method in Geneous10.2.2 software [23]. The Ka/Ks values were calculated with Ka/Ks Calculator v2.0 (https://sourceforge.net/projects/kakscalculator2/) (accessed on 13 January 2025). The Pi value of chloroplast protein-coding genes (PCGs) was analyzed using DnaSP software [24].

The phylogenetic relationship was conducted on all 41 chloroplast genomes in the Ericaceae family, using Magnolia officinalis (NC_020316.1) as an outgroup. PCGs alignment was performed using the MAFFT website (https://mafft.cbrc.jp/alignment/server/index.html) (accessed on 13 January 2025) [25], all missing sites were filtered out using TBtools software [26], the optimal model was calculated using ModelTest NG software [27], and this model was determined on the Akaike information criteria. A phylogenetic tree was built using RAXML-n [28] based on the maximum likelihood (ML) method, and the tree-building model was GTR+I+G4.

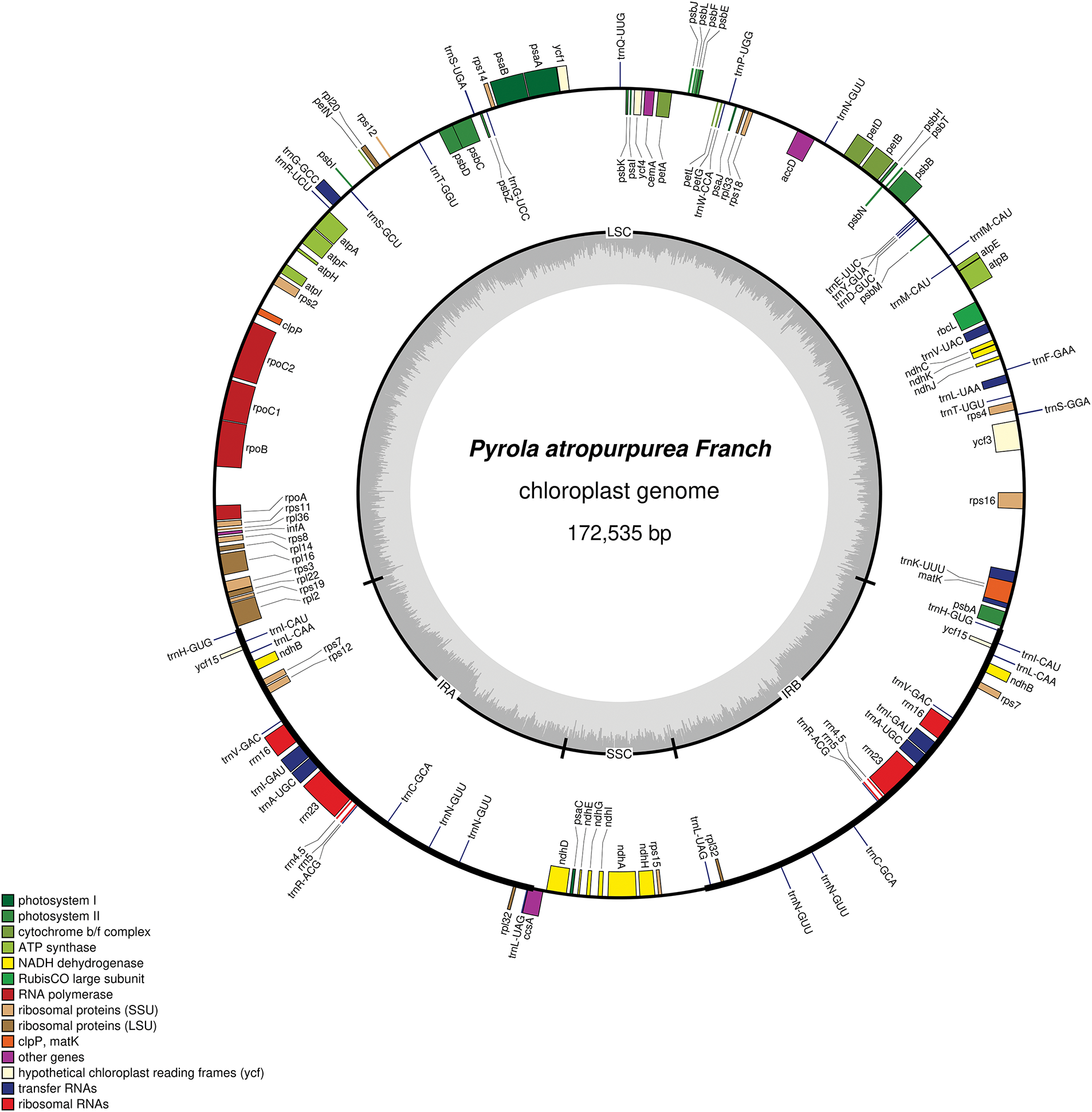

3.1 Chloroplast Genome Structure

The total length of the P. atropurpura chloroplast genome (GenBank accession number: PP473790) is 172,535 bp, with a GC value of 34.95%. The genome has a typical tetrad structure, that is, the entire circular genome can be partitioned into a large single copy (LSC), a small single copy (SSC), and two inverted repeats (IR) regions (Fig. 1). The LSC, SSC, and IR region lengths are 105,081, 11,700, and 27,877 bp, with GC values of 34.72%, 27.99%, and 38.74%, respectively. In total, 132 genes were annotated comprising 43 tRNA, 8 rRNA, 76 PCGs, and 5 pseudogenes (Table S1). In tRNA, trnA-UGC, trnC-GCA, trnH-GUG, trnI-CAU, trnI-GAU, trnL-CAA, trnL-UAG, trnN-GUU, trnR-ACG, and trnV-GAC each have two copies. And trnA-UGC, trnG-GCC, trnI-GAU, trnK-UUU, trnL-UAA and trnV-UAC each own one intron. There are four types of rRNA, each with two copies, situated in the IR region. In the encoded protein genes, there are two copies each of ribosomal protein subunit rpl32, and rps7, and unknown functional protein ycf15, atpF, clpP, rpoC1, ndhB, petB, petD, rpl16, rpl2, rps12, and rps16 all own one intron, while ycf3 has two introns (Table S2). In the deeply explored chloroplast genome, all ndh genes (ndhK, ndhD, ndhG, ndhA, and ndhH) except ndhB, are pseudogenes.

Figure 1: The P. atropurpura chloroplast genome map in the genus Pyrola

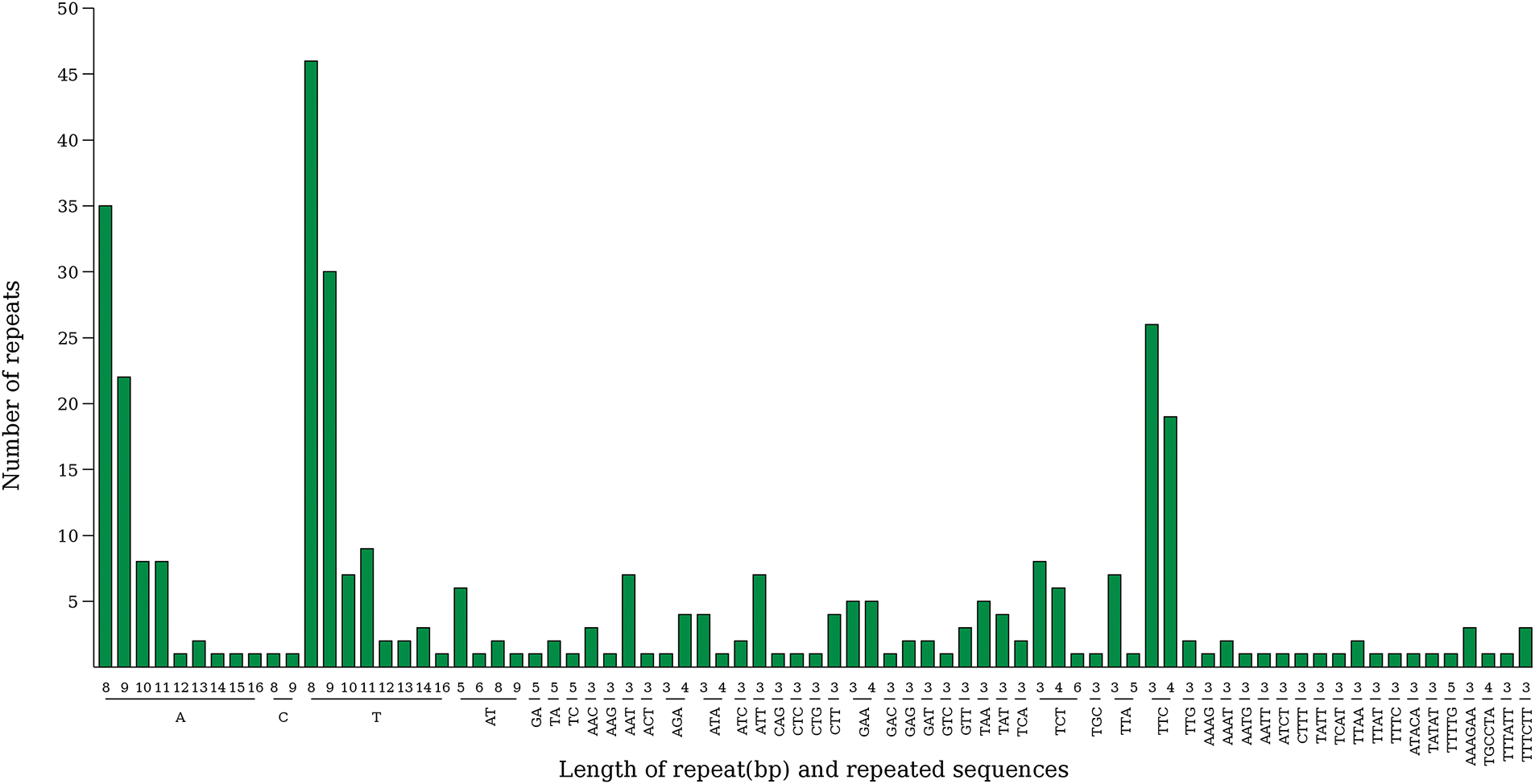

In total, 4223 scattered repeat sequences were predicted in the P. atropurpura chloroplast genome (Fig. S1). Among them, there were 2452 forward repeats (58.06%), 1763 palindromic repeats (41.75%), and eight reverse repeat (0.19%), and no complementary repeats were found. And 358 SSRs were checked in the P. atropurpura chloroplast genome (Fig. 2), including 181 single nucleotide repeats, 14 dinucleotide repeats, 139 trinucleotide repeats, 13 tetranucleotide repeats, 3 pentanucleotide repeats, and 8 hexanucleotide repeats. Most SSRs are positioned in the LSC region (244), with only a few were distributed in the SSC (78) and IR region (36) (Fig. S2). In addition, the majority of SSRs are located in 260 intergenic regions (72.62%), followed by 14 in gene coding regions (3.91%) and 84 in intron regions (23.46%), indicating that SSRs are mainly distributed in intergenic regions (Fig. S3). These SSRs are mainly single base repeats composed of A or T, indicating that the SSRs of this genome have a strong preference for A and T.

Figure 2: Distribution of SSR type in the chloroplast genome of P. atropurpura

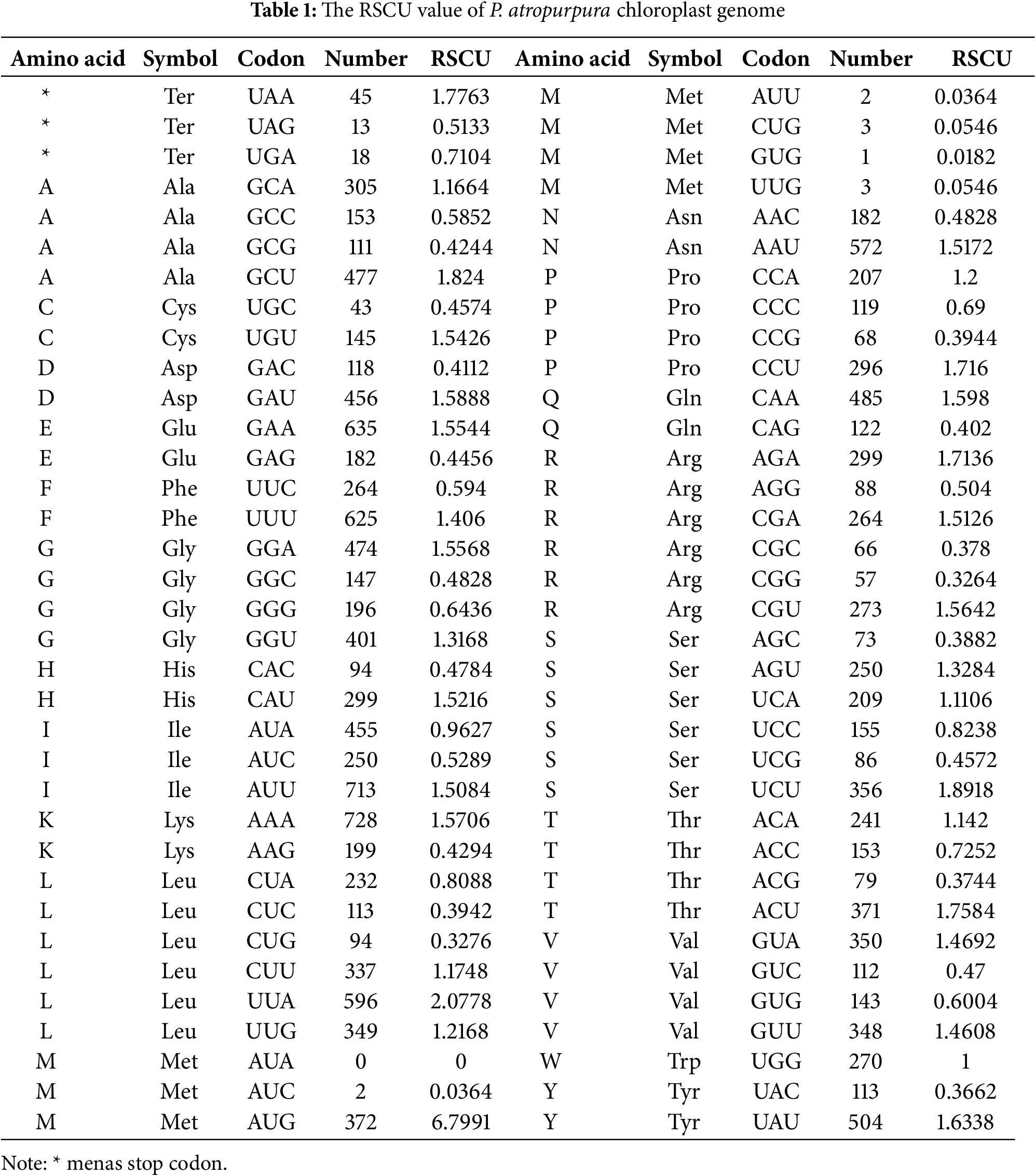

3.3 Codon Preference and Nucleotide Polymorphism

The relative usage of synonymous codons (RSCU) analysis is based on P. atropurpura chloroplast genome, 71 coding DNA sequences (CDS) larger than 200 bp were obtained. The research results indicate that the chloroplast genome contains a total of 16,561 codons. Among them, there are 1721 codons encoding leucine (Leu), accounting for the highest proportion of 10.39%. The codon encoding cysteine (Cys) is 188, accounting for the smallest proportion at 1.14% (Table 1). At the same time, 31 codons with RSCU greater than 1 were detected, with all codons ending in A/U except UUG and AUG. The RSCU value of codon AUG encoding methionine was the highest, at 6.7991 (Table 1 and Fig. S4).

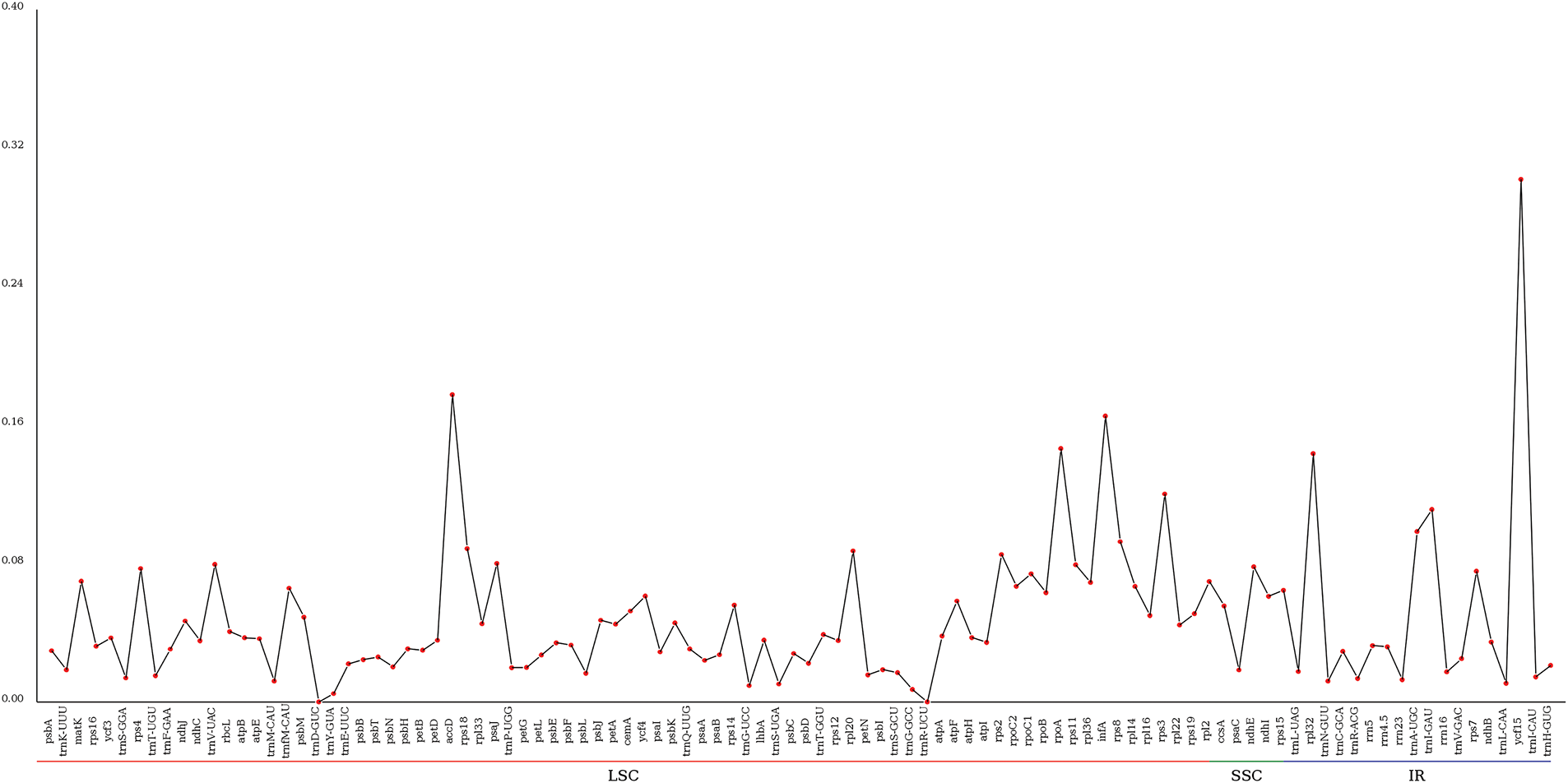

The nucleotide polymorphism (Pi) value of chloroplast protein-coding gene sequences of seven Pyrola species was analyzed using DnaSP software (Fig. 3). The complete length of the aligned sequences was 57,658 bp, and a total of 5213 polymorphic sites were discriminated. The Pi value ranged from 0 to 0.3019, with an average of 0.0479. Among the seven highly variable hotspots that were identified (Pi value > 0.11), two genes (trnT-UGU, and trnF-GAA) are situated in the LSC region, and five genes (ccsA, psaC, ndhE, ndhI, and rps15) are seated in the SSC region. No nucleotide polymorphism sites were detected in the IR region, demonstrating that the nucleotide polymorphism in the LSC and SSC regions is significantly higher than in the IR region.

Figure 3: Divergent hot-spot nucleotide sites in Ericaceae species’ chloroplast genomes

3.4 Structure Variation of Chloroplast Genome

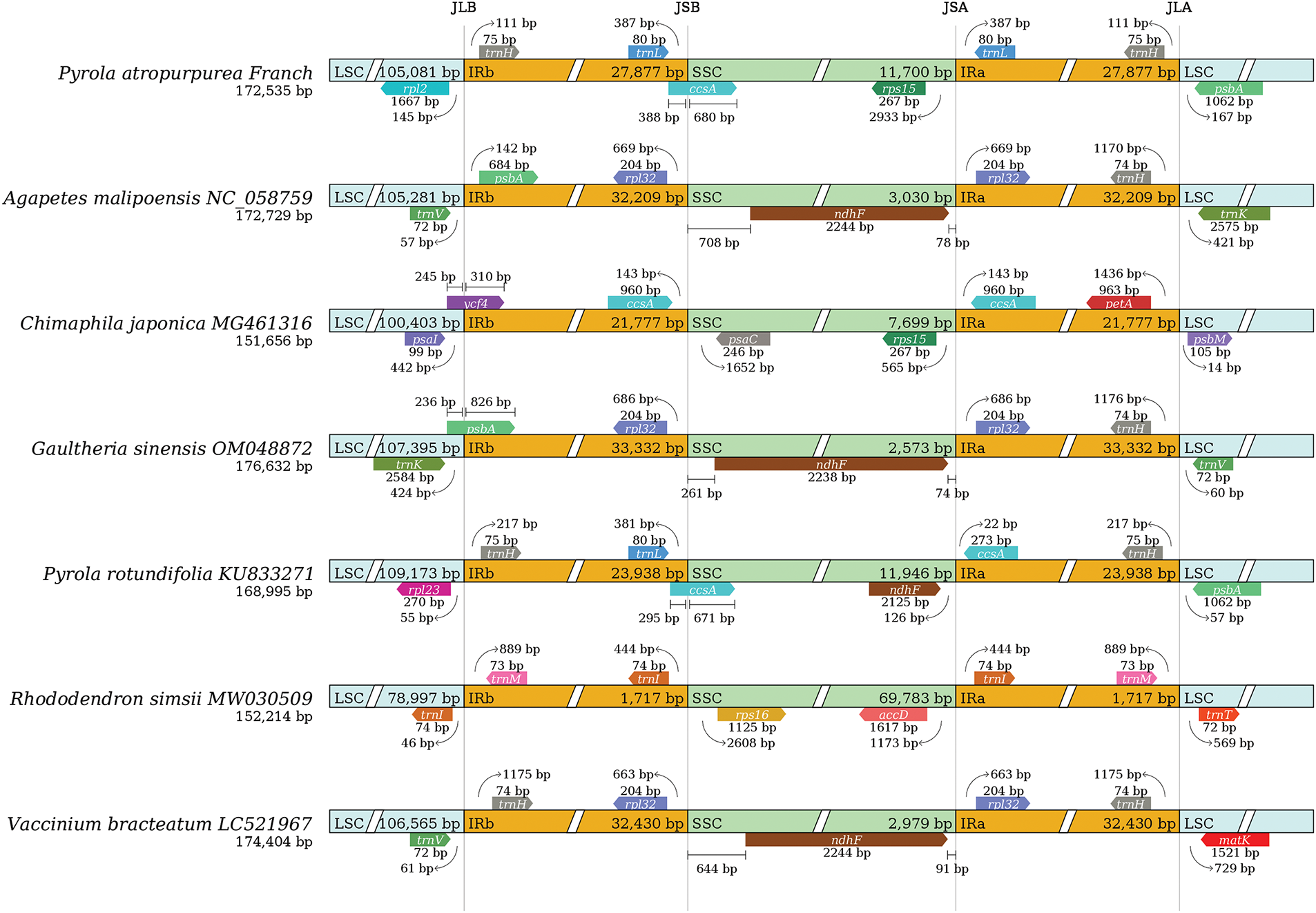

To compare the chloroplast genome differences between P. atropurpura and the representative group of Ericaceae species, we calculated the basic information of chloroplast genomes (Table 2). The P. atropurpura chloroplast genomes and its six closely related species had significant differences, with a total length range of 151,656 bp (Chimaphila japonica) to 176,632 bp (Gaultheria sinensis), all of which are typical tetrad structures. The length compositions of LSC, SSC, and IR in the above-mentioned genome are 78,997 to 109,173 bp, 2979 to 11,946 bp, and 1717 to 33,332 bp, respectively. The total number of genes is 102 to 146, PCGs are 63 to 94, tRNA genes are 4 to 8, and rRNA numbers are 30 to 43. In the variation of GC content, the GC values ranged from 35.0% to 36.8%. Boundary analysis showed obvious differences in the transition regions of the four boundary zones (Fig. 4), which further demonstrated the significant differences in Ericaceae chloroplast genome sequences.

Figure 4: Boundary comparison of Ericaceae chloroplast genome

3.5 Genome Diversity of Chloroplast Genome

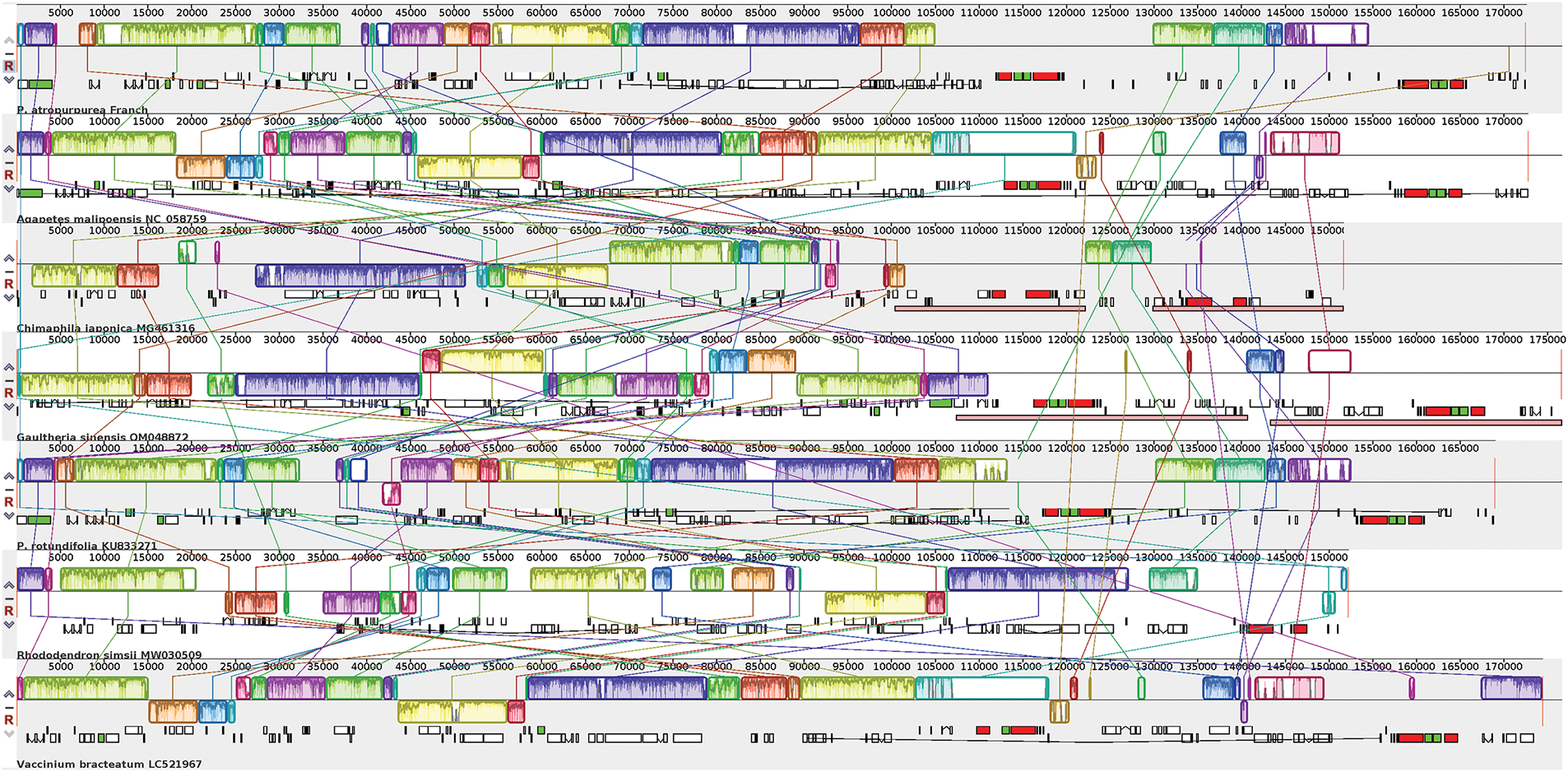

The seven Ericaceae chloroplast genomes were compared with the Mauve software (https://github.com/MauveSoftware/novu) (accessed on 13 January 2025). It was found that the chloroplast genome sequences had high variation, with higher variation in non-coding regions than in coding regions, and higher variation in LSC and SSC regions than in IR regions. Compared to other Ericaceae species, the sequence variation of Chimaphila japonica and Rhododendron simsii is relatively high. The gene number and order of the chloroplast genome in Ericaceae are variable, and an obvious gene rearrangement phenomenon was observed (Fig. 5).

Figure 5: Alignment of chloroplast genomes structure in Ericaceae

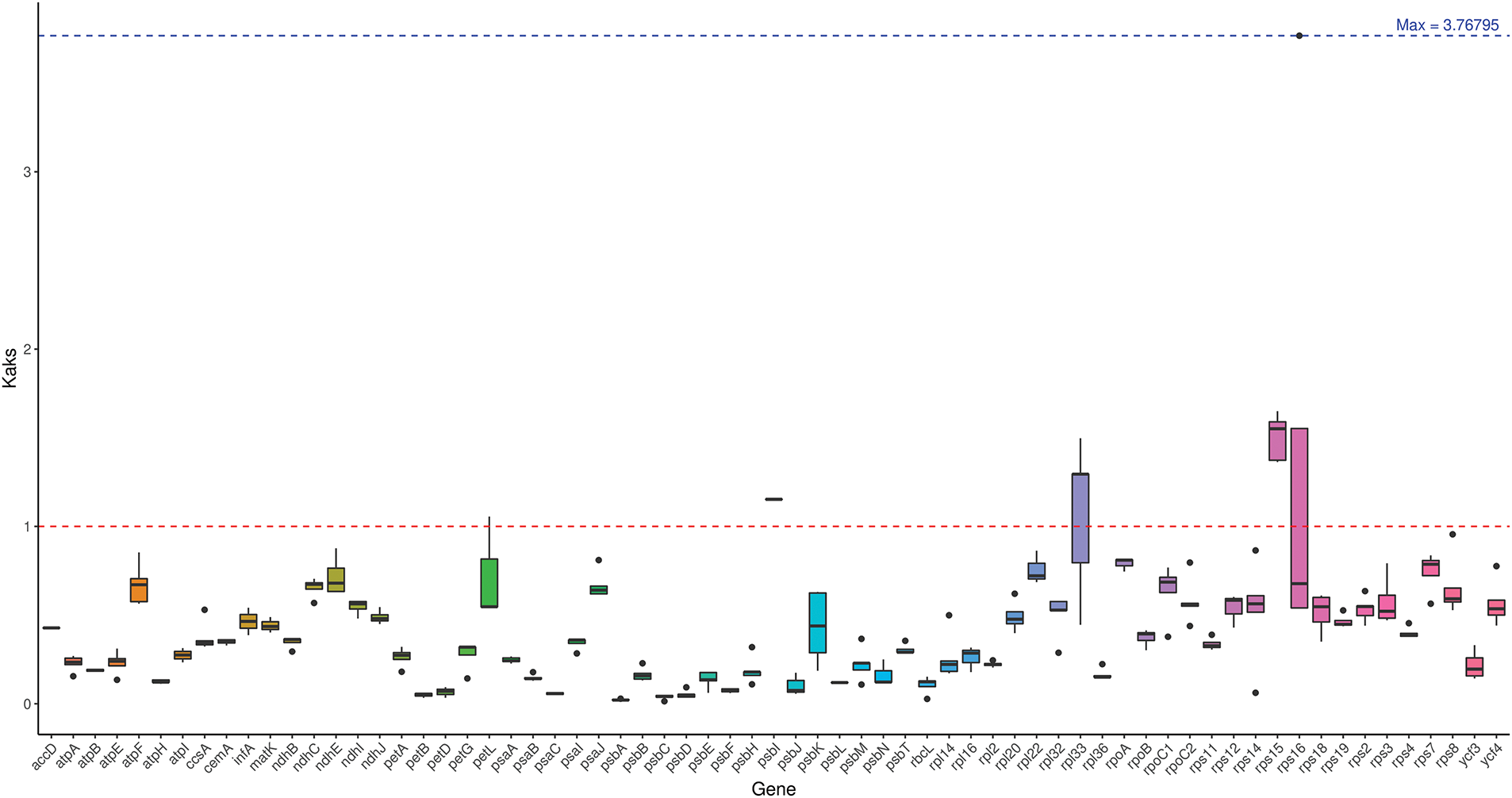

To investigate the evolutionary characteristics of the Ericaceae family in the chloroplast genome, Ka/Ks calculations were performed on 68 common PCGs of the P. atropurpura chloroplast genome and its six closely related species (Fig. 6). The genes without numerical values in Fig. 6 indicate that the Ka/Ks value is zero. Most genes related to the photosystem system, such as petA, psbA, atpA, atpB, atpE, atpI, rbcL, psbE, psbB, psbC, psbD, psbF, ndhB, ndhJ, etc., have Ka/Ks values less than 1, showing that these key genes have been purified and selected. The above genes play a very important role in the functioning of the chloroplast genome and are therefore relatively conserved in evolution. Moreover, the Ka/Ks values of rpl33 and rps16 genes were higher among the five species, demonstrating that these genes were positively selected.

Figure 6: Ka/Ks values of common PCGs in P. atropurpura

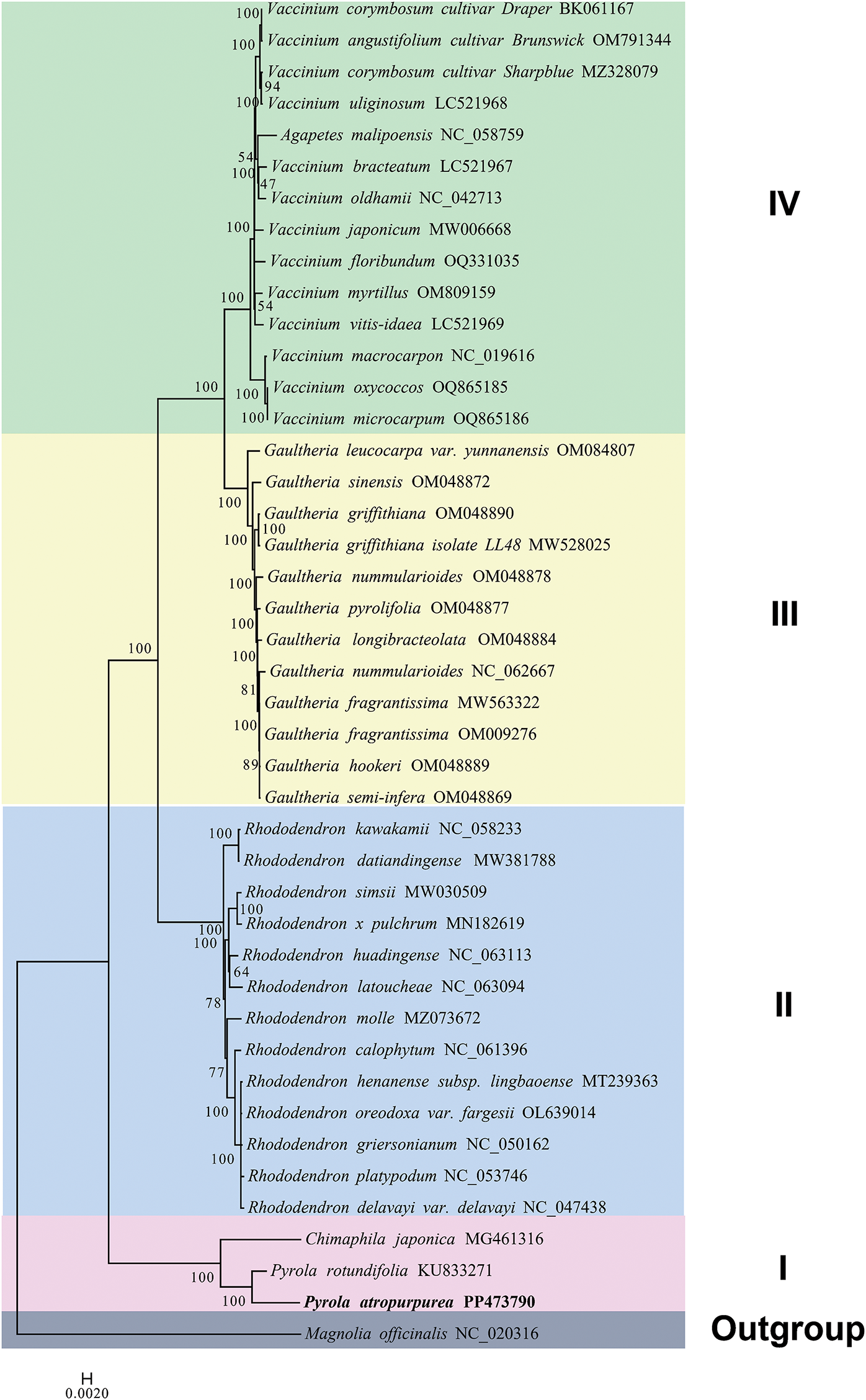

Based on the PCGs of chloroplast genome, a phylogenetic tree of 41 Ericaceae species was built using the ML method of the IQ-TREE software (Fig. 7). Magnolia officinalis (NC_020316.1) was set as the out-group. And the Ericaceae species were mainly classified into four cluster groups, namely Cluster Groups I, II, III, and IV. The three species of the genera Pyrola and Chimaphila are distributed in Cluster I. Cluster Group II is composed of thirteen species in the genus Rhododendron. The thirteen species of the genus Gaultheria are located in Cluster III. And Cluster Group IV is mainly made up of the species in the genus Vaccinium. The phylogenetic result indicated that P. atropura, Pyrola rotundifolia and Chimaphila japonica are clustered together with a 100% support rate, and they have the closest genetic relationship.

Figure 7: The phylogenetic tree of 41Ericaceae species based on chloroplast genome PCGs

Chloroplasts are important plant organelles, widely involved in processes such as photosynthesis and energy conversion. It belongs to matrilineal inheritance, with a genome much smaller and more conserved than the nuclear genome, and is therefore widely used in the study of plant phylogenetics [29]. It is also widely used as a chloroplast DNA barcode for species identification and classification research [30]. P. atropura chloroplast genome was successfully sequenced, assembled, and annotated, obtaining a genome of 172,535 bp, which is similar in size and number of genes to the reported chloroplast genomes of Pyrola [31], this shows that the chloroplast genome has a highly conserved characteristic in this genus.

SSR markers have advantages such as co-dominant inheritance, polymorphism, good repeatability, and easy operation, and are widely used in molecular genetic breeding, population genetic diversity analysis, evolutionary processes, and identification of closely related species [32]. And 358 SSR loci were distributed in the P. atropura chloroplast genome, with the highest number of single nucleotide repeat sequences (181), accounting for the highest proportion (50.56%). SSR loci tend to use A/T bases, which are similar to the sequence characteristics of other plants in the Ericaceae family. This result further confirms the view that polyA and polyT repeats are common in chloroplast SSRs, and they rarely contain C or G tandem repeats [33]. Complex repeats refer to highly repetitive DNA fragments in the genome, which play a crucial role in evolution and the formation of complex genome structures [34]. The scattered repeat sequences in the P. atropura chloroplast genome include three types: forward repeat, reverse repeat, and palindromic repeat. A total of 4223 complex repeats were discriminated, resulting in the high heterogeneity of this chloroplast genome. Rich dispersed repetitive sequences have also been found in other species of Ericaceae, such as the genus Rhododendron [35]. And the heterogeneity is also reflected in the collinearity analysis of the P. atropura chloroplast genome structure.

Codon preference is an important genome evolution feature in organisms, and RSCU value is an important parameter for evaluating the degree of codon preference [36]. There are a total of 64 codons in the P. atropura chloroplast genome, with 31 preferred codons and a preference for using A and U bases. This result is similar to the codon usage preference of nine plant chloroplast genomes in the genera Glycine [37] and also verifies the theory that the closer the species are, the more similar the codon usage patterns [38].

The IR boundaries expansion and contraction in chloroplast genomes are common phenomena in plant evolution [39]. The IR region length in most photosynthetic plant chloroplast genomes varies from 5 to 76 kb and may undergo multiple reductions and expansions during plant evolution. Therefore, the expansion, reduction, or IR region loss is the main cause of length differences in the chloroplast genome and structural variation, and it is also an important feature for distinguishing specific taxa [40]. Studies have shown that there is a typical feature in the plastid genomes of the Ericaceae family, specifically the large expansion of the IR region (approximately 10 kb). The IR region length of P. atropura is 27,877 bp, which is similar to that of Pyrola rotundifolia and Agapetes malipoensis. During long-term evolution, the IR regions of Ericaceae family plants have decreased or increased, indicating that the IR region may be necessary for their growth and development, and also plays an important role in maintaining the chloroplast genome stability. Moreover, there are many heterotrophic groups in this family of species [41].

The colinear alignment in this study showed that the P. atropura chloroplast genome was highly different from its closely related species. This result is also consistent with the IR boundary and genomic feature statistics, further verifying the significant differences between species in this family. There were varying degrees of variation in the gene regions of trnT-UGU, trnF-GAA, ccsA, psaC, ndhE, ndhI, and rps15. It is expected that molecular markers for interspecific identification and phylogenetic analysis of Pyrola plants can be developed from these regions. Ericaceae is a globally distributed family, particularly common in tropical mountainous areas, comprising approximately 125 genera and over 3500 species [42]. This group has complex systematic relationships, including autotrophic and heterotrophic plants. The Ericaceae family is divided into 9 subfamilies, including Enkianthoideae, Pyroloidae, Monotropoideae, Arbutoideae, Cassiopoideae, Ericoideae, Harrimanelloideae, Eparidoideae, and Vaccinoideae. Among them, the Monotropoideae subfamily is heterotrophic, parasitic on fungi, without chlorophyll, while the others are autotrophic groups [43]. One view holds that the subfamily Arbutoideae and Monotropoideae are sister groups, the branch was formed by them and the subfamily Pyroloidae are sister groups, this large branch and other groups of Ericaceae are sister groups, and Enkianthoideae is located at the most basic position [44,45]. Another view is that Enkianthoideae is the most basic group, followed by the subfamily Monotropoideae and Arbutoideae, and the subfamily Pyroloidae is the sister group of other groups [46]. Based on the above research, the phylogenetic relationships within the subfamilies have not been thoroughly resolved. This study found that the 41 species already published by NCBI can be divided into four groups by using PCGs of chloroplast genomes, namely, the genus Pyrola and Chimaphila as group one, the genus Rhododendron as group two, the genus Gaultheria as group three, and the genus Vaccinium as group four. The above data provides information for further species differentiation in this family.

In summary, the P. atropura chloroplast genome length is 172,535 bp and exhibits a typical tetrad structure. The GC content of the entire genome is 34.95%. And 132 genes were annotated, comprising 76 protein-coding, 43 tRNA, and 8 rRNA genes. It is preferred to use codons ending in A/U. A total of 358 SSR loci were detected, with single nucleotide repeat sequences being the predominant SSR loci; and 4223 scattered repeat sequences were discriminated. The size of the IR, SSR, and LSR region was different from that of plants between P. atropurpura and the other five Ericaceae species, and the SSC and IR region variation degree is higher than that in the LSC region. The relationship between P. atropura, Pyrola rotundifolia, and Chimaphila japonica is the closest.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the Education Reform Program of Jiangxi Provincial Department of Education (JXJG-22-23-3, JXJG-23-23-5), the “Biology and Medicine” Discipline Construction Project of Nanchang Normal University (100/20149), Jiangxi Province Key Laboratory of Oil Crops Biology (YLKFKT202203), the Education Reform Program of Nanchang Normal University (NSJG-21-25) and Nanchang Key Laboratory of Comprehensive Research and Development of Brasenia schreberi (32060078).

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available in the NCBI public database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/PP473790.1/) (accessed on 13 January 2025), and the corresponding accession number was PP473790.1.

Ethics Approval: The plant materials in this research do not comprise any endangered wild species that are at risk of extinction. All methods and materials adhered strictly to the relevant legislative frameworks.

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.061424.

References

1. Lee C, Leonie HL, Tina BS, Enrique LJ, Julian MH. Chloroplast development in green plant tissues: the interplay between light, hormone, and transcriptional regulation. New Phytol. 2022;233(5):2000–16. doi:10.1111/nph.17839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Dobrogojski J, Adamiec M, Luciński R. The chloroplast genome: a review. Acta Physiol Plant. 2020;42:98. doi:10.1007/s11738-020-03089-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Wang J, Kan SL, Liao XZ, Zhou JW, Tembrock LR, Daniell H, et al. Plant organellar genomes: much done, much more to do. Trends Plant Sci. 2024;29(7):754–69. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2023.12.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Wu ZQ, Liao XZ, Zhang XN, Tembrock LR, Broz A. Genomic architectural variation of plant mitochondria-A review of multichromosomal structuring. J Syst Evol. 2022;60(1):160–8. doi:10.1111/jse.12655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Chong X, Li Y, Yan M, Wang Y, Li M, Zhou Y, et al. Comparative chloroplast genome analysis of 10 Ilex species and the development of species-specific identification markers. Ind Crops Prod. 2022;187:115408. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2022.115408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Xiao SZ, Xu P, Deng YT, Dai XB, Zhao LK, Heider B, et al. Comparative analysis of chloroplast genomes of cultivars and wild species of sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam). BMC Genomics. 2021;22:262. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

7. Wang R, Yang Y, Tian H, Yi H, Xu L, Lv Y, et al. A scalable and robust chloroplast genotyping solution: development and application of SNP and InDel markers in the maize chloroplast genome. Genes. 2024;15(3):293. doi:10.3390/genes15030293. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Zhang Y, Du CH, Zhan HX, Shang CL, Li RF. Yuan SJ. Comparative and phylogeny analysis of Platycodon grandiflorus complete chloroplast genomes. Chin Tradit Herb Drugs. 2023;54(15):4981–991. [Google Scholar]

9. Chen XY, Hu BX, Shi JZ. Complete chloroplast genome and phylogenetic analysisof Rubia cordifolia. Acta Botanica Boreali-Occidentalia Sinica. 2023;43(11):1–10. [Google Scholar]

10. Geng YM, Zhou XQ, Zhang TC, Zheng LP. Characterization and phylogenetic analysis of chloroplast genome of Cynanchum wallichii and Cynanchum otophyllum. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica. 2024;59(3):764–74. [Google Scholar]

11. Dong HJ, Liu ZW, Peng H. Geographical distribution and floristic significance of Pyrola in China. Plant Sci J. 2024;42(1):43–7. doi:10.11913/PSJ.2095-0837.23018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Cao Y, Chen QB, Li TY, Chen BR. Exploitation and utilization of Pyrola L. resources. J Hebei Agricul Sci. 2008;12(3):113–114 119. [Google Scholar]

13. Zhao ZF, Wu N, Tian X, Fu YL, Zhang Q, He XR. Chemical constituents, biological activities and quality control of plants from genus Pyrola. China J Chin Mater Med. 2017;42(4):618–27. [Google Scholar]

14. Yang XL, She JL, Liu JP, Yang T, An GG, Chen QR, et al. A comprehensive review of the genus Pyrola Herbs in traditional uses, phytochemistry and pharmacological activities. Curr Top Med Chem. 2020;20(1):57–77. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

15. Chen LY, Song MS, Zha HG, Li ZM. A modified protocol for plant genome DNA extraction. Plant Divers Resour. 2014;36(3):375–80. doi:10.7677/ynzwyj201413156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Dierckxsens N, Mardulyn P, Smits G. NOVOPlasty: de novo assembly of organelle genomes from whole genome data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(4):e18. doi:10.1093/nar/gkw955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Qu XJ, Moore MJ, Li DZ, Yi TS. PGA: a software package for rapid, accurate, and flexible batch annotation of plastomes. Plant Methods. 2019;15(1):50. doi:10.1186/s13007-019-0435-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Lohse M, Drechsel O, Kahlau S, Bock R. Organellar Genome DRAW—a suite of tools for generating physical maps of plastid and mitochondrial genomes and visualizing expression data sets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(W1):W575–81. doi:10.1093/nar/gkt289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Shields DC, Sharp PM. Synonymous codon usage in Bacillus subtilis reflects both translational selection and mutational biases. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15(19):8023–40. doi:10.1093/nar/15.19.8023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Kurtz S, Choudhuri JV, Ohlebusch E, Schleiermacher E, Stoye J, Giegerich R. REPuter: the manifold applications of repeat analysis on a genomic scale. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29(22):4633–42. doi:10.1093/nar/29.22.4633. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Thiel T, Michalek W, Varshney RK, Graner A. Exploiting EST databases for the development and characterization of gene-derived SSR-markers in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). Theor Appl Genet. 2003;106:411–22. doi:10.1007/s00122-002-1031-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Amiryousefi A, HyvÖnen J, Poczai P. IRscope: an online program to visualize the junction sites of chloroplast genomes. Bioinformatics. 2018;34(17):3030–1. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/bty220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Kearse M, Moir R, Wilson A, Stones-Havas S, Cheung M, Sturrock S, et al. Geneious Basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(12):1647–9. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/bts199. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Rozas J, Ferrer-Mata A, Sanchez-Delbarrio JC, Guirao-Rico S, Librado P, Ramos-Onsins SE, et al. DnaSP 6: DNA sequence polymorphism analysis of large data sets. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2017;34(12):3299–302. doi:10.1093/molbev/msx248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Katoh K, Rozewicki J, Yamada KD. MAFFT on-line service: multiple sequence alignment, interactive sequence choice and visualization. Brief Bioinform. 2019;20(4):1160–6. doi:10.1093/bib/bbx108. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Chen CJ, Chen H, Zhang Y, Thomas HR, Frank MH, He YH, et al. TBtools: an integrative toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. Mol Plant. 2020;13(8):1194–202. doi:10.1016/j.molp.2020.06.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Darriba D, Posada D, Kozlov AM, Stamatakis A, Morel B, Flouri T. ModelTest-NG: a new and scalable tool for the selection of DNA and protein evolutionary models. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2020;37(1):291–4. doi:10.1093/molbev/msz189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Kozlov AM, Darriba D, Flouri T, Morel B, Stamatakis A. RAxMLNG: a fast, scalable and user-friendly tool for maximum likelihood phylogenetic inference. Bioinformatics. 2019;35(21):4453–5. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btz305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Kress W, Wurdack K, Zimmer E, Weigt L, Janzen D. Use of DNA barcodes to identify flowering plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(23):8369–74. doi:10.1073/pnas.0503123102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Jansen RK, Cai Z, Raubeson LA, Daniell H, Depamphilis CW, Leebens-Mack J, et al. Analysis of 81 genes from 64 plastid genomes resolves relationships in angiosperms and identifies genome-scale evolutionary patterns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(49):19369–74. doi:10.1073/pnas.0709121104. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Logacheva MD, Schelkunov MI, Shtratnikova VY, Matveeva MV, Penin AA. Comparative analysis of plastid genomes of non-photosynthetic Ericaceae and their photosynthetic relatives. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):30042. doi:10.1038/srep30042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Kaur S, Panesar PS, Bera MB, Kaur V. Simple sequence repeat markers in genetic divergence and marker-assisted selection of rice cultivars: a review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2015;55(1):41–9. doi:10.1080/10408398.2011.646363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Liu B, Wu HF, Cao YZ, Yang XM, Sui SZ. Establishment of novel simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers from Chimonanthus praecox transcriptome data and their application in the Identification of Varieties. Plants. 2024;13:2131. doi:10.3390/plants13152131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Cui Y, Ye W, Li JS, Li JJ, Vilain E, Sallam T, et al. A genome-wide spectrum of tandem repeat expansions in 338,963 humans. Cell. 2024;187(22):6411–2. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2024.09.045. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Mo ZQ, Fu CN, Zhu MS, Milne RI, Yang JB, Cai J, et al. Resolution, conflict and rate shifts: insights from a densely sampled plastome phylogeny for Rhododendron (Ericaceae). Ann Bot. 2022;130(5):687–701. doi:10.1093/aob/mcac114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Chakraborty S, Yengkhom S, Uddin A. Analysis of Codon usage bias of chloroplast genes in Oryza species: codon usage of chloroplast genes in Oryza species. Planta. 2020;252(4):67. doi:10.1007/s00425-020-03470-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Xiao M, Hu X, Li Y, Liu Q, Shen S, Jiang T, et al. Comparative analysis of codon usage patterns in the chloroplast genomes of nine forage legumes. Physiol Mol Biol Plants. 2024;30(2):153–66. doi:10.1007/s12298-024-01421-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Parvathy ST, Udayasuriyan V, Bhadana V. Codon usage bias. Mol Biol Rep. 2022;49(1):539–65. doi:10.1007/s11033-021-06749-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Tang L, Tam NFY, Lam W, Lee TCH, Xu SJL, Lee CL, et al. Interpreting the complexities of the plastid genome in dinoflagellates: a mini-review of recent advances. Plant Mol Biol. 2024;114(6):87. doi:10.1007/s11103-024-01511-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Li DM, Pan YG, Liu HL, Yu B, Huang D, Zhu GF. Thirteen complete chloroplast genomes of the costaceae family: insights into genome structure, selective pressure and phylogenetic relationships. BMC Genomics. 2024;25:68. doi:10.1186/s12864-024-09996-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Gao WJ, Li HL, Song WW, Wang XQ. Plastid genome structural characteristics and phylogenetic relationships of Ericaceae. J West China Forest Sci. 2023;52(5):20–8. [Google Scholar]

42. WFO. World Flora Online; [cited 2024 Oct 24]. Available from: https://www.Worldfloraonline.org. [Google Scholar]

43. Kron KA, Judd WS, Stevens PF, Crayn DM, Anderberg AA, Gadek PA, et al. Phylogenetic classification of Ericaceae: molecular and morphological evidence. Bot Rev. 2002;68(3):335–423. doi:10.1663/0006-8101(2002)068[0335:PCOEMA]2.0.CO;2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Braukmann T, Stefanovic S. Plastid genome evolution in mycoheterotrophic Ericaceae. Plant Mol Biol. 2012;79(1–2):5–20. doi:10.1007/s11103-012-9884-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Freudenstein JV, Broe MB, Feldenkris ER. Phylogenetic relationships at the base of Ericaceae: implications for vegetative and mycorrhizal evolution. Taxon. 2016;65(4):794–804. doi:10.12705/654.7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Rose JP, Kleist TJ, Lofstrand SD, Löfstrand SD, Drew BT, Schönenberger J, et al. Phylogeny, historical biogeography, and diversification of angiosperm order Ericales suggest ancient Neotropical and East Asian connections. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2018;122:59–79. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2018.01.014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools