Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Optimization of Extraction, Compositional Analysis and Biological Activities of Fructus Ligustri Lucidi Essential Oil

1 Department of Pharmacy, The Affiliated Hospital of Yangzhou University, Yangzhou University, Yangzhou, 225009, China

2 Institute of Translational Medicine, School of Medicine, Yangzhou University, Yangzhou, 225001, China

3 The Key Laboratory of the Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions for Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine in Senile Diseases Control (Yangzhou University), Yangzhou, 225001, China

* Corresponding Authors: Qi Liu. Email: ; Huijing Lin. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Biological Activities of Essential Oils)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(2), 441-454. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.061720

Received 01 December 2024; Accepted 27 January 2025; Issue published 06 March 2025

Abstract

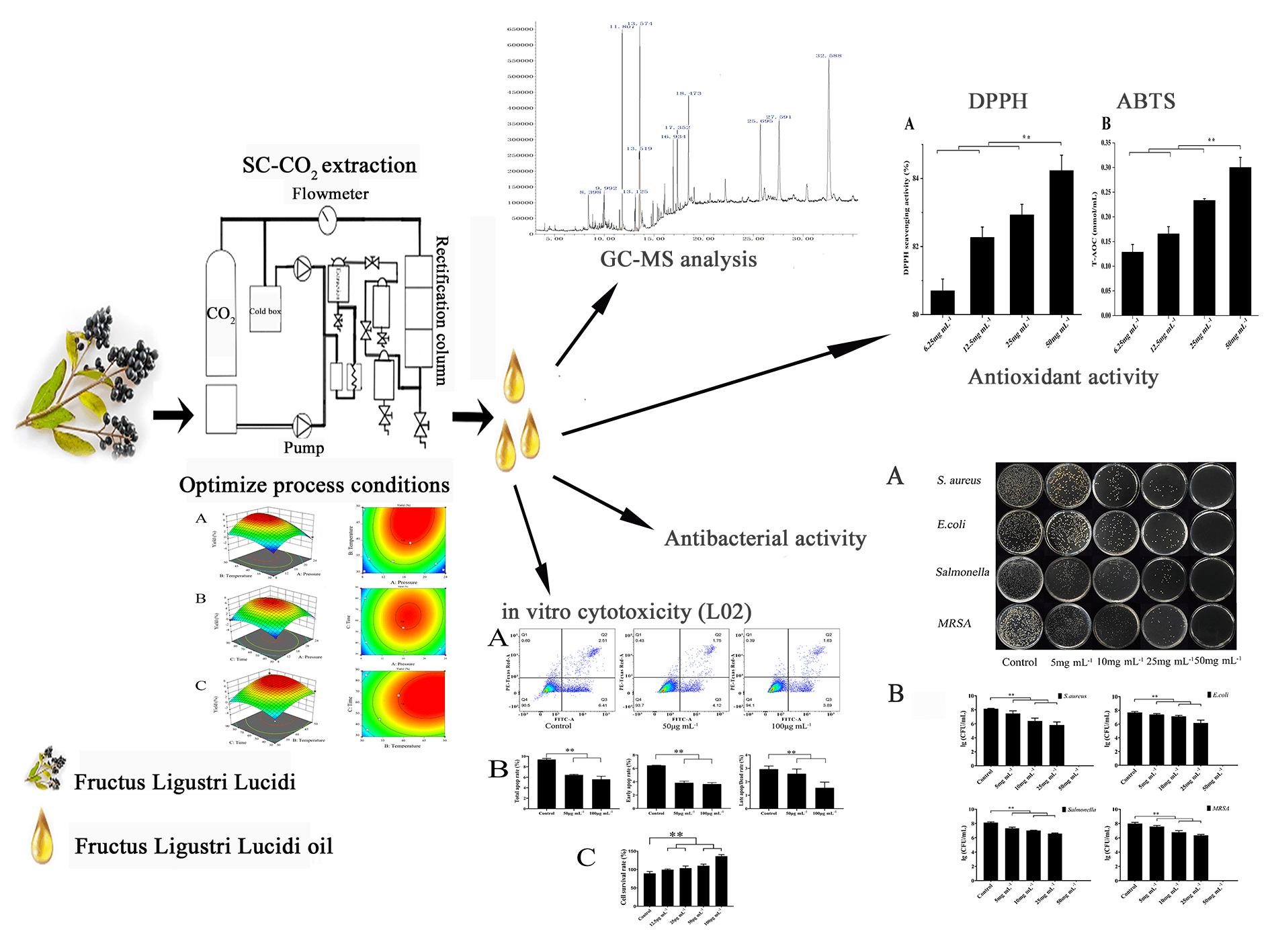

Fructus Ligustri Lucidi (FLL) refers to the dried mature fruit of Ligustrum lucidum Ait., a species from the Oleaceae family, widely distributed across East Asia and India. This study aimed to optimize the extraction process for Fructus Ligustri Lucidi essential oil (FLLO) to develop an efficient and practical extraction method. Additionally, the chemical composition of FLLO was analyzed, and its antioxidant, antimicrobial, and cytotoxic activities were evaluated. FLLO was extracted using supercritical CO2 extraction, and response surface methodology was applied to optimize the extraction parameters: pressure of 16 MPa, temperature of 40°C, and extraction time of 40 min. The main components of the essential oil were identified through GC-MS analysis. Antioxidant activity was assessed using DPPH and ABTS assays, demonstrating that FLLO exhibited strong antioxidant properties, with a DPPH radical scavenging rate exceeding 80%. In antimicrobial tests, FLLO exhibited significant inhibitory effects on both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria at concentrations greater than 25 mg/mL. Additionally, cytotoxicity assays revealed that FLLO enhanced the proliferation of LO2 cells. In conclusion, FLLO, extracted using supercritical CO2, demonstrates excellent antioxidant and antimicrobial properties, as well as favorable cell safety, supporting its potential for further development and application of Ligustrum lucidum.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Microbial contamination of food is a significant cause of human diseases [1]. Various antimicrobial agents have been incorporated into food products to inhibit microbial growth, including antibiotics, biological products, antibacterial plastics [2], fibers [3], ceramics [4,5], and metal particles [6,7]. Although antibiotics exhibit strong antibacterial activity and a broad antimicrobial spectrum, their extensive use has led to the emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria [8,9]. Biological products, primarily antimicrobial peptides, are costly to produce and pose concerns regarding safety and potential drug resistance [10–14]. Furthermore, the use of certain antimicrobial materials presents challenges; for instance, heavy metal ions released as antimicrobial agents can adversely affect health if improperly managed [15,16]. Consequently, natural antimicrobial substances have garnered increasing attention from researchers.

Antibacterial essential oils (EOs) are derived from natural plants and are considered preferable to antibiotics because they do not promote the development of bacterial resistance. Plant EOs have a broad range of applications and are known for their high biological safety [17], as well as the absence of residual heavy metal ions [18–21]. As a result, plant EOs have garnered significant attention from researchers in recent years. Literature reports highlight the effectiveness of EOs, such as peppermint [22], Erigeron mucronatus [23], and sugarcane molasses [24], which exhibit strong antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus), Escherichia coli (E. coli), Streptococcus pyogenes (S. pyogenes), Klebsiella pneumoniae (K. pneumoniae), and other bacteria [25,26].

The extraction of plant essential oils (EOs) can be categorized into several methods: microwave-assisted extraction [27,28], steam distillation [29,30], water extraction, and alcohol extraction. While these methods are straightforward and convenient, they have certain limitations. For instance, steam distillation can only extract volatile components, while alcohol extraction may leave solvent residues. Supercritical fluid extraction (SFE) uses supercritical fluids, near their critical points, as solvents to extract the desired components from liquid or solid sources. SFE is considered a green, pollution-free, and efficient extraction method [31,32], and is particularly effective for extracting plant EOs [33,34]. Typically performed at room temperature, SFE preserves the chemical integrity of the extract. Moreover, it offers a wide extraction range with no residual solvents [35]. By adjusting different SFE conditions, high oil yields can be achieved [36,37]. EOs produced by SFE generally exhibit high biological activity [38,39].

Fructus Ligustri Lucid (FLL) is the fruit of the Oleaceae plant Ligustrum Lucidum, which is known for its various effects, including increasing bone mineral density [40,41], exhibiting anti-inflammatory properties [42], and protecting the liver [43,44]. However, relatively few studies have focused on the antimicrobial activities of FLL oil (FLLO). The extraction of essential oils (EOs) from FLL is typically carried out through steam distillation, water extraction, and alcohol extraction [45,46]. Supercritical CO2 extraction was employed to obtain FLLO, and response surface methodology (RSM) was applied for process optimization to identify the optimal extraction conditions and analyze the product components. The antibacterial activity of FLLO was then tested. Finally, the biological safety of FLLO was evaluated by assessing its effects on liver cells (LO2). These findings provide a theoretical foundation for the development and application of FLLO in the food and pharmaceutical industries.

The Fructus Ligustri Lucid (FLL) used in this experiment were sourced from Tai’an, Shandong Province, China. The DPPH kit was supplied by Fuzhou Phygene Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Fuzhou, China). The ABTS kit was obtained from Elabscience Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China). And the Cell Activity Assay Kit was purchased from Beyotime Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China); LO2 cells were provided by Shanghai Biowing Applied Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

2.2 Supercritical Extraction Operations

The SFE apparatus (HA21-50-01) was used to extract FLLO. The procedure followed these steps: The Fructus Ligustri Lucid were crushed, sieved through a 30-mesh screen, and mixed with an equal volume of absolute ethanol; The mixture was then sealed and kept overnight. Next, 100 g of this mixture was transferred into the SFE kettle, the temperature was adjusted to the pre-set value, the carbon dioxide pump was activated, and the gas was introduced into the kettle. The pressure valve was adjusted to reach the pre-set value, and the extraction time was initiated. When the pre-set extraction time was reached, the product was collected.

To optimize the yield of FLL, it is essential to determine the best extraction conditions for FLLO through the application of response surface methodology. Based on the results of preliminary experiments, the relationship between the independent variables—pressure (X1; 8–24 MPa), temperature (X2; 30–50°C), and time (X3; 30–90 min)—was evaluated, with the highest extraction efficiency of FLLO (Y) as the dependent variable.

For GC-MS analysis, Fructus Ligustri Lucidi essential oil was first completely dissolved in absolute ethanol, and the solution was then passed through a 0.22 μm microporous membrane before being analyzed using an Agilent 8890–7000E triple quadrupole gas chromatograph.

The analytical conditions were as follows: a column of Agilent HP-5MS, a quartz capillary column (30 mm × 250 mm × 0.25 μm); helium (He) was used as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 1.2 mL/min. The injector temperature was set to 250°C, and 1 μL of the sample was injected in split mode with a split ratio of 20:1. The temperature program started at 50°C for 2 min, then increased at a rate of 20°C/min to 220°C, held for 3 min, followed by a further increase at 30°C/min to 280°C, where it was maintained for 20 min. The total run time was 35.5 min.

For mass spectrometry, the conditions included electron impact (EI) ionization with an electron energy of 70 eV. The transmission line temperature was 250°C, and the ion source temperature was 230°C. The activation voltage was set to 15 V, and the mass scan range was from 50 m/z to 500 m/z. The solvent delay time was 3 min.

DPPH accepts electrons from antioxidants, forming a stabilized purple free radical, which is then scavenged, resulting in a decrease in absorbance at 517 nm. Therefore, the free radical scavenging activity can be quantified by measuring the change in absorbance. A 3 mg sample of DPPH was dissolved in 100 mL of anhydrous ethanol. FLLO was then dissolved in anhydrous ethanol to obtain final concentrations of 6.25, 12.5, 25, and 50 mg/mL. Next, 100 μL of the essential oil solution was mixed with 900 μL of a DPPH-ethanol solution, and the reaction was allowed to proceed for 30 min at room temperature, shielded from light. The absorbance was then measured at 517 nm. For the control, 100 μL of pure ethanol was added to 900 μL of the DPPH-ethanol solution. The free radical scavenging activity was determined using the equation below Eq. (1):

2.5.2 Total Antioxidant Capacity (ABTS Method)

The ABTS method is a widely used technique to assess the antioxidant capacity of a substance in vitro. ABTS reacts with K2S2O8 to form the stable free radical ABTS+, which exhibits a maximum absorption at 734 nm and a blue-green color. When the free radicals are scavenged and reduced, the color of the solution lightens, resulting in a decrease in absorbance at 734 nm. This change can be used to determine the sample’s ability to scavenge ABTS+.

To prepare the ABTS working solution, ABTS solution and oxidant solution were mixed in a 1:1 ratio. FLLO was dissolved in anhydrous ethanol to prepare final concentrations of 6.25, 12.5, 25, and 50 mg/mL. Then, 200 μL of the ABTS working solution and 10 μL of FLLO were added to each well, gently mixed, and the reaction was incubated at room temperature for 2–6 min. The absorbance at 734 nm (A734) was subsequently measured and control absorbance was determined by adding distilled water to the blank wells. The total antioxidant capacity was calculated using the standard curve.

In this study, S. aureus, MRSA, E. coli, and Salmonella were used as test bacteria. Single colonies were inoculated into LB medium and incubated in a shaking incubator for 15 h to obtain an activated bacterial solution. Next, 50 μL of the activated bacterial solution was added to 4950 μL of LB liquid medium and cultured at 37°C and 180 rpm for 3 h until the optical density (OD600) reached 0.7, thereby preparing the bacterial inoculation solution. Subsequently, 900 μL of 1% Tween-80 aqueous solution was added to 100 μL of the bacterial inoculation solution to serve as the control group. The experimental group consisted of final FLLO concentrations of 5, 10, 25, and 50 mg/mL. After exposing the bacterial solution to different FLLO concentrations at 37°C for 24 h, 10 μL of the solution was plated onto a Petri dish. Finally, the colony-forming units (CFU/mL) of the bacteria were counted after 12 h [47].

Liver LO2 cells were initially cultured in a six-well plate (1 × 106 cells per well) for 24 h; FLLO was mixed with 1% Tween-80 aqueous solution, passed through a 0.22 μm microporous membrane, and added to six-well plate to make the final concentration of the system at 50 μg/mL, 100 mg/mL. After a 24 h incubation, the cells were treated with 1 mL of trypsin, followed by the addition of 1 mL of PBS buffer. The cells were then collected, transferred into a 5 mL centrifuge tube, and centrifuged at 800 rpm for 4 min. The supernatant was discarded, and the cell pellet was resuspended in 100 μL of resuspension solution. Next, 5 μL of Annexin V-FITC and 10 μL of PI staining solution were added, and the mixture was incubated at room temperature for 15 min, protected from light. Following incubation, the cells were resuspended with an additional 400 μL of resuspension solution. The samples were filtered through a copper mesh and analyzed using flow cytometry (BD FACSCalibur, Franklin Lake, NJ, USA), the instrument was purchased from Jiangsu New Haitian International Trading Co., Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, China. Data analysis was performed with FlowJo V10 software.

Cell cultures were performed in 96-well plates (5 × 104 cells per well). FLLO was added to the experimental group at concentrations of 12.5, 25, 50, and 100 μg/mL, while the control group was maintained without FLLO. After 24 h of incubation, cell viability was evaluated using the CCK-8 assay. In this method, 10 μL of CCK-8 reagent was added to each well., and the culture was continued for 2 h. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm [48], and cell viability was calculated using the following equation Eq. (2):

The final results of the experiment were expressed as the mean of three replicates. The data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and were analyzed for statistical significance using SPSS version 26 software. Statistical significance was assessed using one-way ANOVA to compare results between different groups.

3.1 Optimization Results for FLLO Extraction and Its Chemical Profile

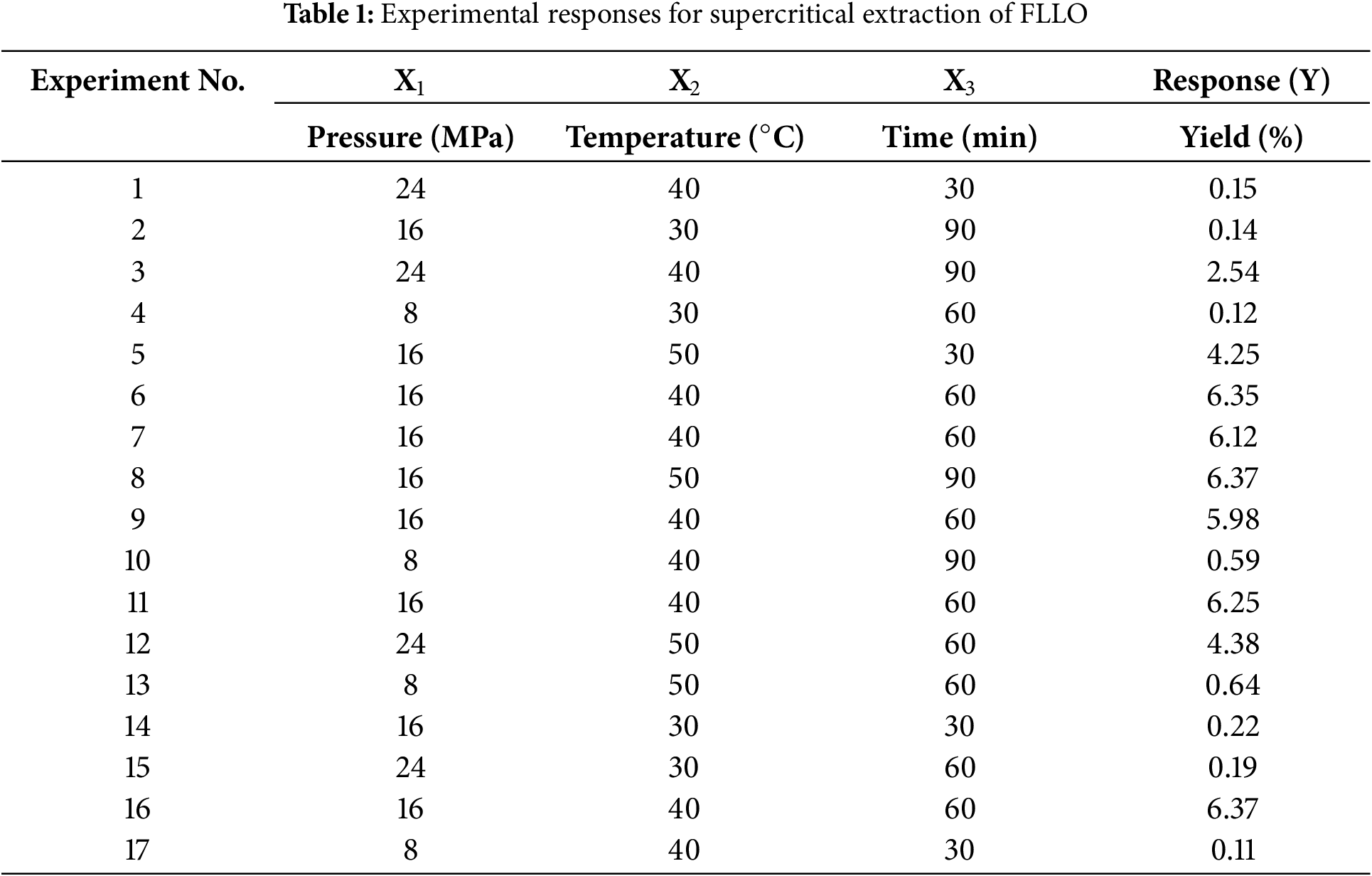

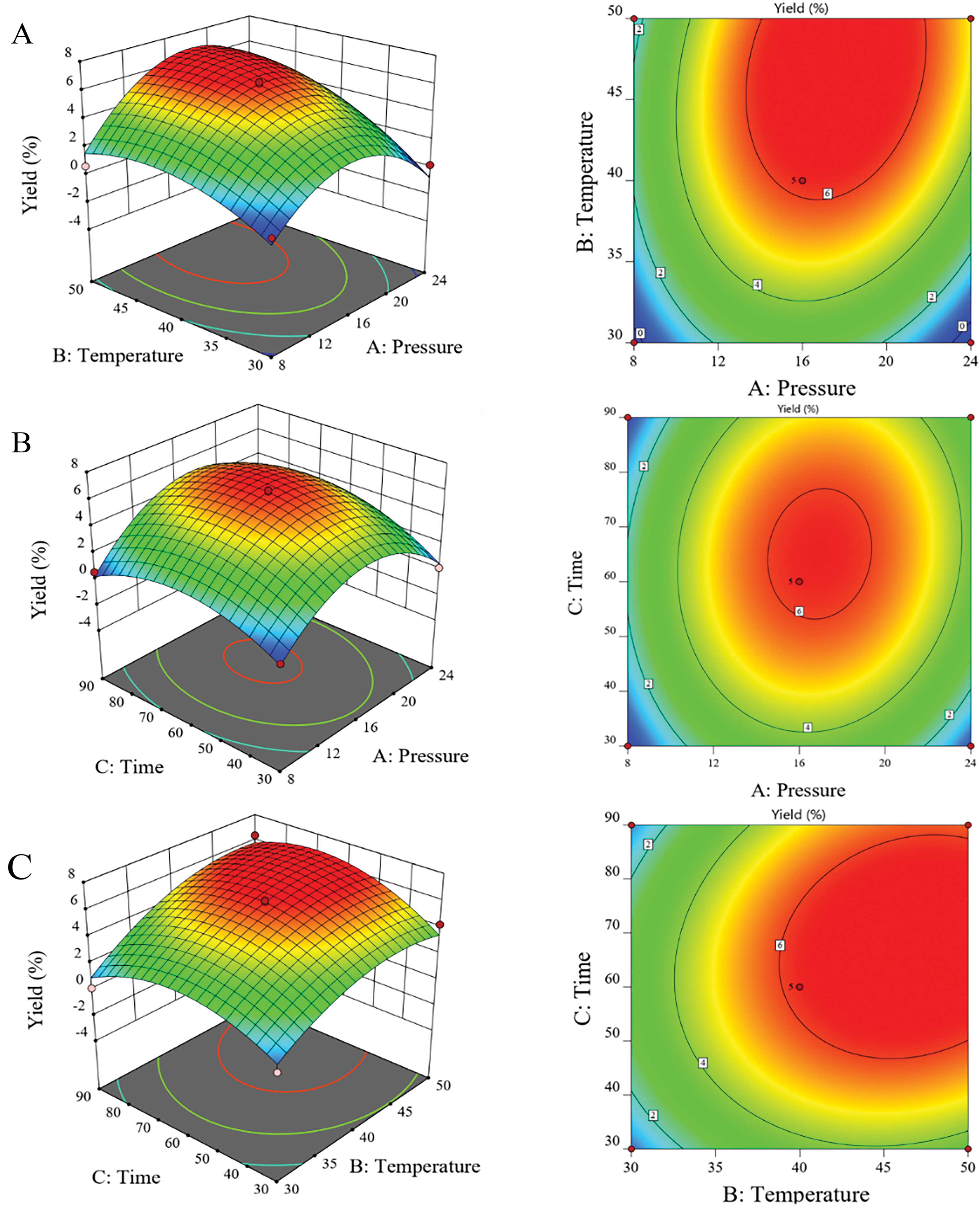

To achieve higher extraction efficiency, the Box-Behnken Design (BBD) was used for process optimization. After 17 experimental runs designed by BBD, the FLLO yield was determined, as shown in (Table 1). The corresponding surface and contour plots are also shown in (Fig. 1). Under the conditions of constant extraction time and temperature, the extraction yield of FLLO had a maximum value with the increase of pressure (Fig. 1A). When the extraction pressure and extraction time were held constant, the FLLO yield increased with higher extraction temperatures. However, once the temperature rose to 40°C, the yield increased more slowly. Under constant extraction pressure and temperature, the yield of FLLO increased as the extraction time was extended, but remained relatively unchanged when the extraction time exceeded 60 min.

Figure 1: 3D response surface plots and 2D contour plots: The effects of extraction pressure and temperature (A), extraction pressure and time (B), and extraction temperature and time (C) on the yield of FLLO are shown

Final quadratic regression equation in terms of actual factors was obtained as below; also, ANOVA for quadratic model has been shown in Table 2.

The optimal conditions for supercritical extraction of FLLO were determined as: The extraction was conducted at a pressure of 16 MPa, a temperature of 50°C, and an extraction time of 90 min, resulting in a yield of 6.37%. However, considering cost and safety factors, the optimal process was adjusted to: extraction pressure 16 MPa, extraction temperature 40°C, and extraction time 60 min, the extraction yield was predicted to be 6.21%. The process was then verified experimentally, and the average extraction yield of FLLO, measured across three trials, was 6.14%. Therefore, the RSM optimization for supercritical extraction of FLLO was found to be stable and feasible.

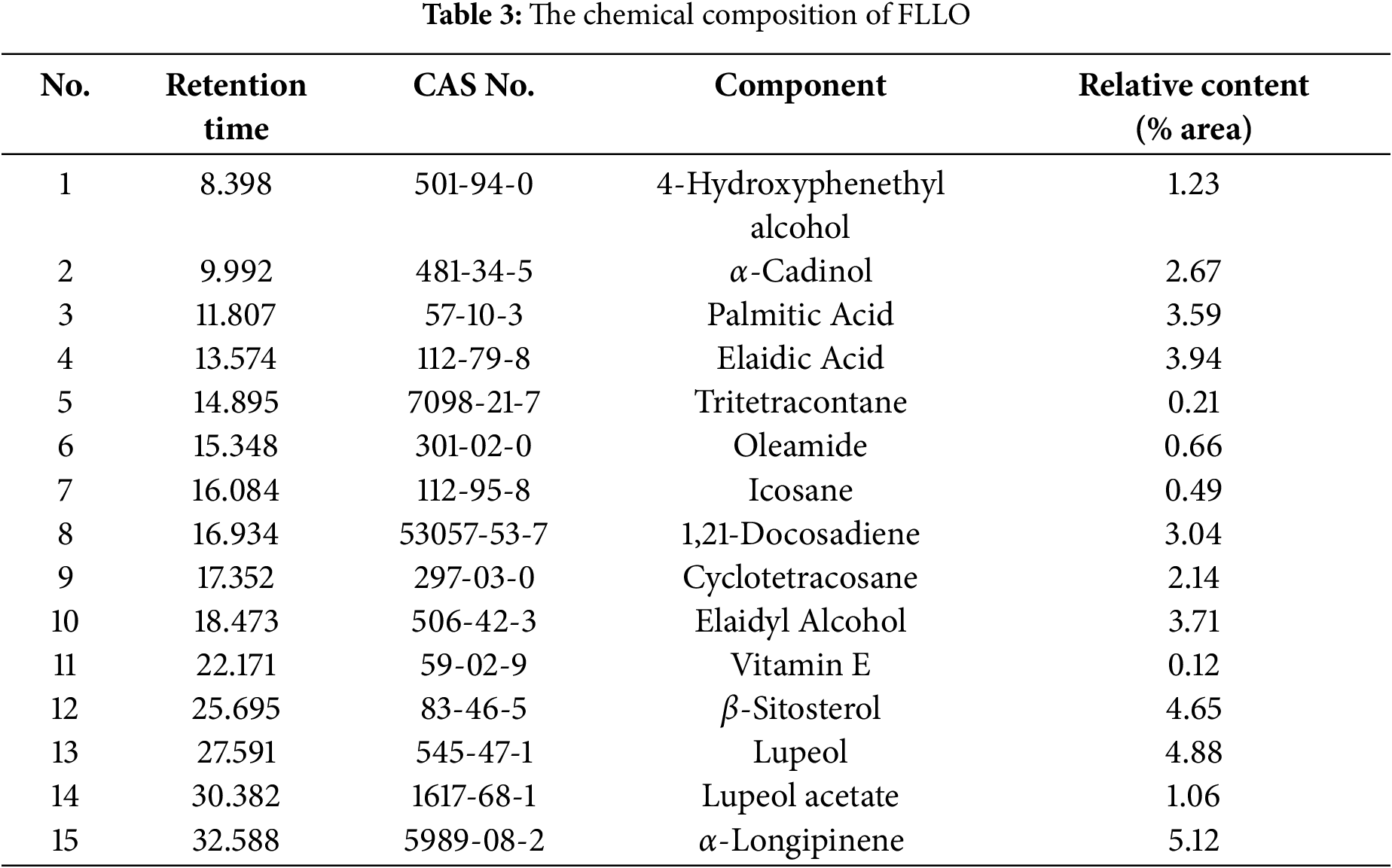

The analytical results of GC-MS are shown in (Table 3). The analysis identified 15 compounds in the essential oil of Fructus Ligustri Lucidi. Among these, terpenoids such as α-Cadinol (2.67%), β-Sitosterol (4.65%), and Lupeol (4.88%) exhibited notable biological activities and were present in higher concentrations. Additionally, fatty acids like Palmitic Acid and Elaidic Acid, along with some alcohols, olefins, and alkanes, were detected, though in relatively lower amounts.

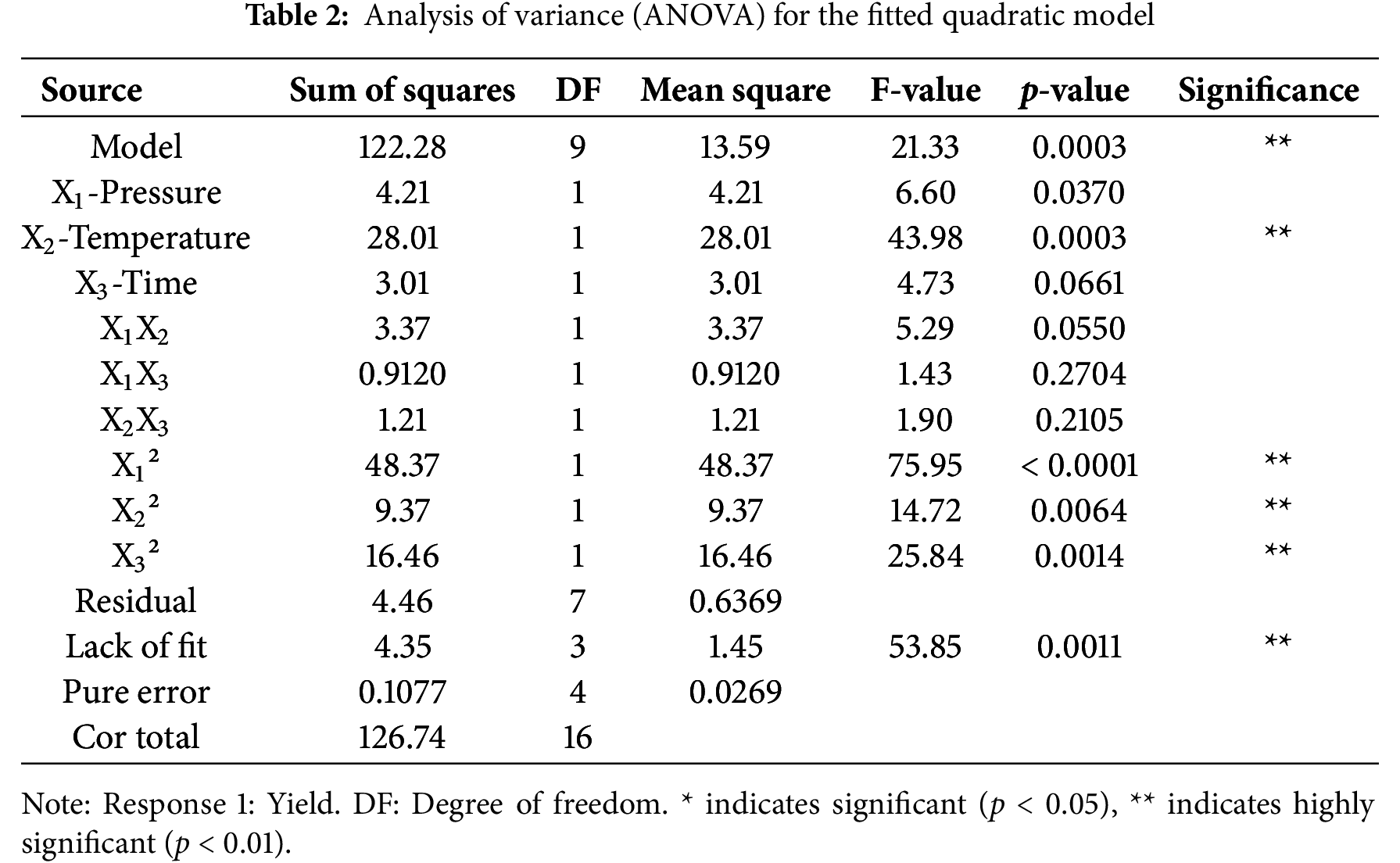

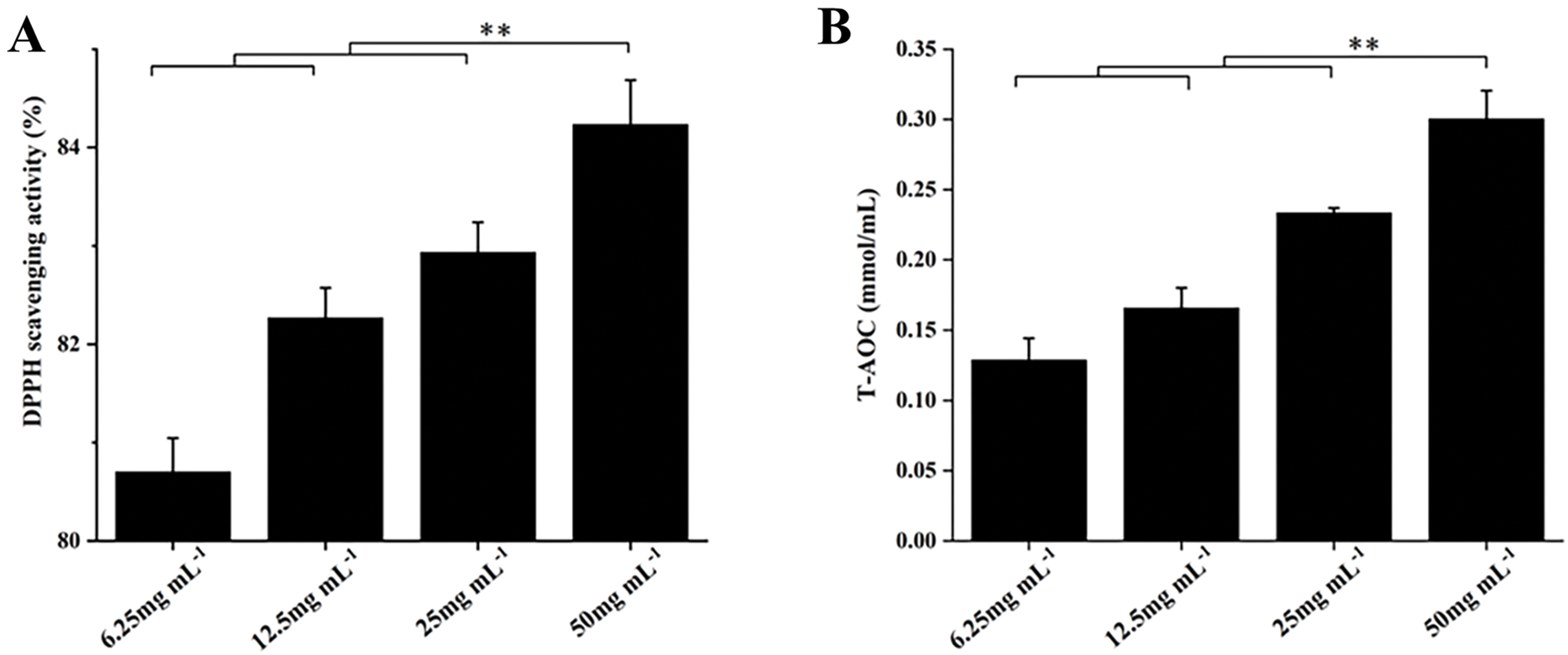

Plant essential oils, as natural products, generally exhibit strong antioxidant activity. Their antioxidant capacity is affected by factors such as the type, composition, and concentration of the essential oil, making them widely applicable in fields such as medicine and food. Fig. 2 below illustrates the antioxidant activity of FLLO measured using two methods. Both methods showed the same trend, the antioxidant capacity increased with higher concentrations of essential oil concentration, and the DPPH radical scavenging activity exceeded 80%. This suggests that FLLO has excellent antioxidant activity, likely attributed to the high concentrations of β-Sitosterol and Lupeol, as indicated by the GC-MS data in Table 3. These findings are consistent with the work of Parvez et al. [49].

Figure 2: DPPH scavenging activity of FLLO (A); Total antioxidant capacity of FLLO (B). ** indicates highly significant (p < 0.01)

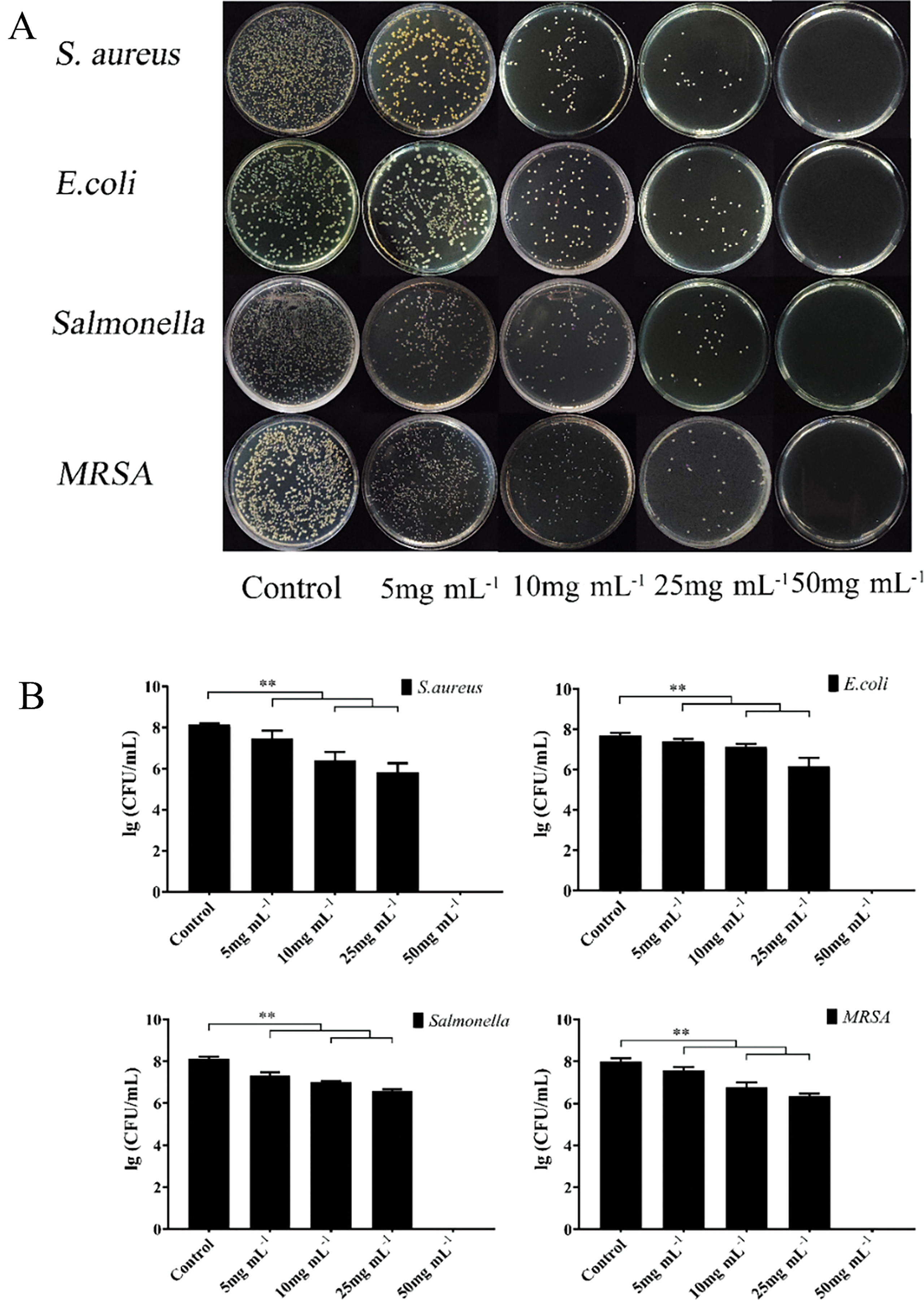

In the next step, the antibacterial activity of the optimum FLLO was evaluated against four different bacteria: S. aureus, MRSA, E. coli, and Salmonella. The results revealed that FLLO exhibited significant antibacterial activity against these target bacteria (Fig. 3), with no major differences in activity among the four bacteria. At final FLLO concentrations of 5 and 10 mg/mL, bacterial numbers were slightly reduced compared to the control group. However, at a concentration of 25 mg/mL, a significant reduction in bacterial numbers was observed (p < 0.05). Finally, at a concentration of 50 mg/mL, no bacterial growth was detected (Fig. 3). These findings suggest that FLLO has a strong antibacterial effect against the tested bacteria, likely due to the high concentration of α-Cadinol in FLLO. A study by Su et al. also reported strong antibacterial activity of α-Cadinol derived from the fruit essential oil of Eucalyptus citriodora [50].

Figure 3: Bacterial growth after treatment with various concentrations of FLLO (A); The inhibitory effect of FLLO against different bacteria (B). ** indicates highly significant (p < 0.01)

3.4 In Vitro Cytotoxicity of FLLO

Based on the results of the study, it was found that FLLO exhibits good antimicrobial and antioxidant activities, indicating its great potential for future applications in both pharmaceutical and food fields. To ensure the biosafety of FLLO, hepatocytes (LO2) were chosen to investigate the effects of different concentrations of FLLO on cell viability and apoptosis.

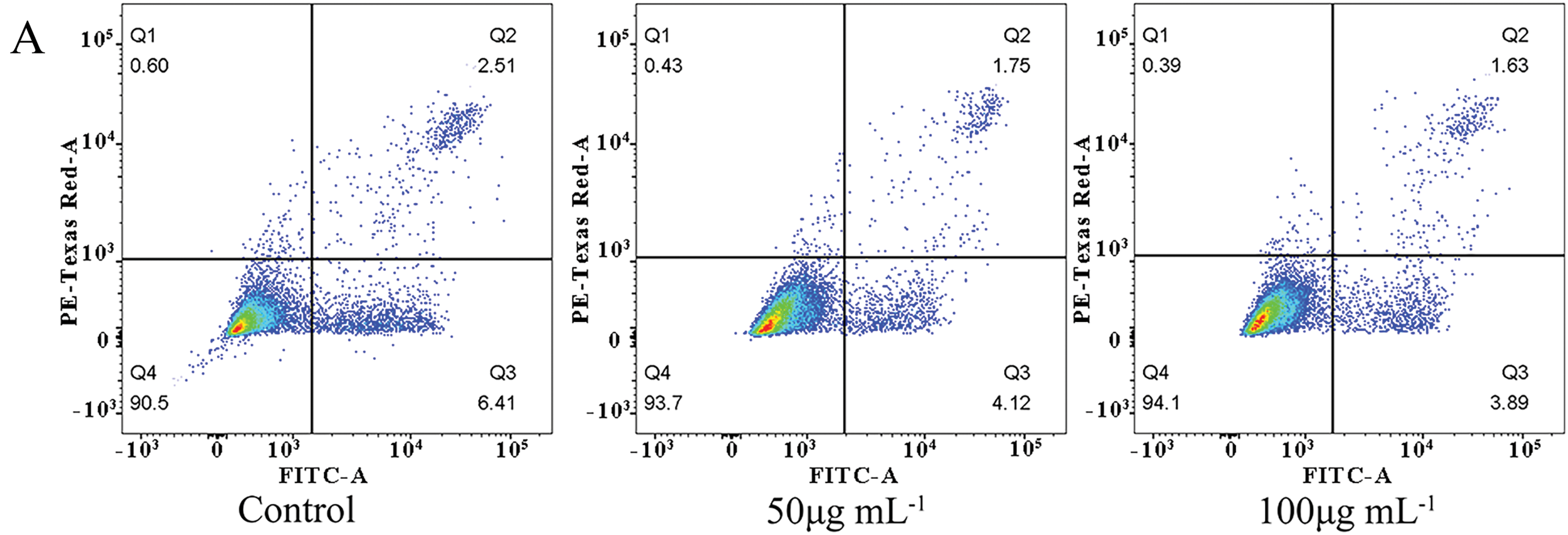

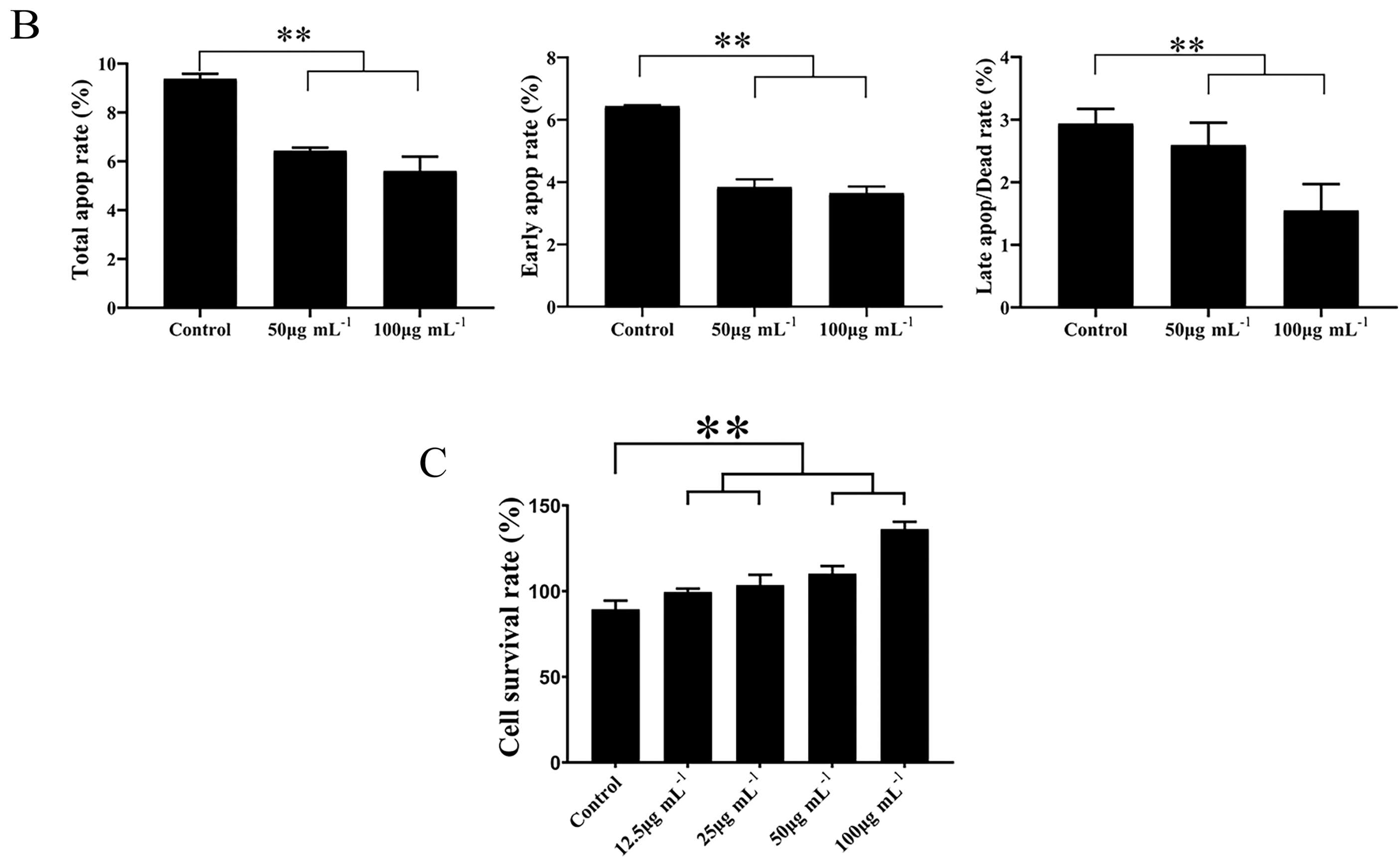

Annexin V-FITC/PI staining was employed to evaluate the effect of FLLO on apoptosis in LO2 cells [51]. The results demonstrated that FLLO effectively inhibited both early and late apoptosis in LO2 cells. At a concentration of 50 μg/mL, the early and late apoptosis rates were 4.12% and 1.75%, respectively. When the FLLO concentration was increased to 100 μg/mL, the early and late apoptosis rates were 3.89% and 1.63%, respectively. In contrast, the early and late apoptosis rates in the control group were 6.41% and 2.51%, respectively. These findings suggest that FLLO effectively protects hepatocyte growth and demonstrates good biosafety while maintaining its potent antibacterial activity.

As a potential antimicrobial additive, the safety of FLLO is crucial. Cytotoxicity serves as an important indicator for evaluating the biological safety of antimicrobial compounds. As shown in (Fig. 4), after 24 h of FLLO treatment, the cell survival rate at a concentration of 12.5 μg/mL was ≥80%, and at concentrations of 25 μg/mL or higher, the cell survival rate increased to ≥100%. The results demonstrate exhibits good safety in LO2 cells. This may be related to the presence of ursolic acid in FLLO, which was shown by Zhou et al. to have the potential to promote the proliferation and differentiation of LO2 cells [4,52].

Figure 4: The effect of FLLO on LO2 cell apoptosis in different concentrations (A); and different phase (B); Cell viability of LO2 cells after treatment with FLLO for 24 h (C). ** indicates highly significant (p < 0.01)

These findings demonstrate that FLLO is a naturally derived compound with excellent antioxidant and antibacterial properties, coupled with a high safety profile in LO2 cells. As such, FLLO holds significant potential as an additive in food, pharmaceutical, and cosmetic applications. Moreover, the extraction process was optimized using supercritical carbon dioxide extraction to enhance efficiency. However, to fully realize the benefits and broader applicability of FLLO, further research is needed. This should include in vivo studies and evaluations against a broader range of bacterial and fungal strains, facilitating the development of more effective and safer antimicrobial agents. Additionally, future studies should focus on comprehensive chemical analyses of FLLO to identify its active components with antioxidant and antimicrobial properties and elucidate their mechanisms of action.

Acknowledgement: Thank you for the professional testing services provided by the Yangzhou University Test Center.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Longgang Wang: Methodology; Formal analysis; Data curation; Writing—original draft preparation. Xiangxun Zhuansun: Methodology; Formal analysis; Data curation; Writing—original draft preparation. Yao Li: Methodology; Software; Qili Yao: Methodology; Qi Liu: Conceptualization; Investigation; Writing—review and editing; Supervision; Project administration. Huijing Lin: Project administration; Supervision. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to disclose concerning the present study.

References

1. Abebe GM. The role of bacterial biofilm in antibiotic resistance and food contamination. Int J Microbiol. 2020;2020:1–10. doi:10.1155/2020/1705814. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Chang SH, Chen YJ, Tseng HJ, Hsiao HI, Chai HJ, Shang KC, et al. Antibacterial activity of chitosan-polylactate fabricated plastic film and its application on the preservation of fish fillet. Polymers. 2021;13(5):696. doi:10.3390/polym13050696. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Pagnotta G, Graziani G, Baldini N, Maso A, Focarete ML, Berni M, et al. Nanodecoration of electrospun polymeric fibers with nanostructured silver coatings by ionized jet deposition for antibacterial tissues. Mat Sci Eng C. 2020;113. doi:10.1016/j.msec.2020.110998. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Verma AS, Singh A, Kumar D, Dubey AK. Electro-mechanical and polarization-induced antibacterial response of 45S5 bioglass-sodium potassium niobate piezoelectric ceramic composites. Acs Biomater Sci Eng. 2020;6(5):3055–69. doi:10.1021/acsbiomaterials.0c00091. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Zhu TL, Zhu M, Zhu YF. Fabrication of forsterite scaffolds with photothermal-induced antibacterial activity by 3D printing and polymer-derived ceramics strategy. Ceram Int. 2020;46(9):13607–14. doi:10.1016/j.ceramint.2020.02.146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Bieganski P, Szczupak L, Arruebo M, Kowalski K. Brief survey on organometalated antibacterial drugs and metal-based materials with antibacterial activity. RSC Chem Biol. 2021;2(2):368–86. doi:10.1039/D0CB00218F. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Qi Y, Ren SS, Che Y, Ye JW, Ning GL. Research progress of metal-organic frameworks based antibacterial materials. Acta Chim Sinica. 2020;78(7):613–24. doi:10.6023/A20040126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Mitcheltree MJ, Myers AG. Bacterial drug resistance overcome by synthetic restructuring of antibiotics. Nature. 2021. doi:10.1038/d41586-021-02916-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Kasew D, Eshetie S, Diress A, Tegegne Z, Moges F. Multiple drug resistance bacterial isolates and associated factors among urinary stone patients at the University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Urol. 2021;21(1):27. doi:10.1186/s12894-021-00794-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Liu JY, Li HX, Li HZ, Fang SF, Shi JG, Chen YZ, et al. Rational design of dipicolylamine-containing carbazole amphiphiles combined with Zn2+ as potent broad-spectrum antibacterial agents with a membrane-disruptive mechanism. J Med Chem. 2021;64(14):10429–444. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c00858. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Alhaji NB, Isola TO. Antimicrobial usage by pastoralists in food animals in North-central Nigeria: The associated socio-cultural drivers for antimicrobials misuse and public health implications. One Health. 2018;6:41–7. doi:10.1016/j.onehlt.2018.11.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Gao X, Li HX, Niu XH, Zhang DY, Wang Y, Fan HY, et al. Carbon quantum dots modified Ag2S/CS nanocomposite as effective antibacterial agents. J Inorg Biochem. 2021;220. doi:10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2021.111456. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Wu VM, Tang S, Uskokovic V. Calcium phosphate nanoparticles as intrinsic inorganic antimicrobials: The antibacterial effect. Acs Appl Mater Inter. 2018;10(40):34013–28. doi:10.1021/acsami.8b12784. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Fan YF, Chen HF, Mu N, Wang WG, Zhu KK, Ruan Z, et al. Nosiheptide analogues as potential antibacterial agents via dehydroalanine region modifications: Semi-synthesis, antimicrobial activity and molecular docking study. Bioorgan Med Chem. 2021;31. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2020.115970. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Wronska N, Katir N, Milowska K, Hammi N, Nowak M, Kedzierska M, et al. Antimicrobial effect of chitosan films on food spoilage bacteria. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(11):5839. doi:10.3390/ijms22115839. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Díez-Pascual AM. Antimicrobial polymer-based materials for food packaging applications. Polymers. 2020;12(4):731. doi:10.3390/polym12040731. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. de Medeiros VM, do Nascimento YM, Souto AL, Madeiro SAL, Costa VCD, Silva SMPM, et al. Chemical composition and modulation of bacterial drug resistance of the essential oil from leaves of Croton grewioides. Microb Pathog. 2017;111:468–71. doi:10.1016/j.micpath.2017.09.034. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Luo M, Tang L, Dong Y, Huang H, Deng Z, Sun Y. Antibacterial natural products lobophorin L and M from the marine-derived Streptomyces sp. 4506. Nat Prod Res. 2021;35(24):5581–7. doi:10.1080/14786419.2020.1797730. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Rajesh P, Saravanan G, Muthusami MS, Hariprasath L. “Natural products chemistry and drug design-2020”—a thematic issue (part-3). Cardiovasc Hematol Agents Med Chem. 2021;19(2):100. doi:10.2174/187152571902210805111421. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. An P, Zhang LJ, Peng W, Chen YY, Liu QP, Luan X, et al. Natural products are an important source for proteasome regulating agents. Phytomedicine. 2021;93:153799. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2021.153799. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Arshad N, Hameed A, Hashim J, Iqbal T, Munir I, Ali SA, et al. Natural products embedded crown ethers as potent insulin secretory agents. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2021;34(5):2003–8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

22. Ciotea D, Shamtsyan M, Popa ME. Antibacterial activity of peppermint, basil and rosemary essential oils obtained by steam distillation. Agrolife Sci J. 2021;10(1):75–82. doi:10.17930/AGL. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Awen BZ, Unnithan CR, Ravi S, Lakshmanan AJ. GC-MS analysis, antibacterial activity and genotoxic property of essential oil. Nat Prod Commun. 2010;5(4):621–4. doi:10.1177/1934578X1000500426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Zhang K, Ding ZD, Mo MM, Duan WJ, Bi YG, Kong FS. Essential oils from sugarcane molasses: chemical composition, optimization of microwave-assisted hydrodistillation by response surface methodology and evaluation of its antioxidant and antibacterial activities. Ind Crops Prod. 2020;156:112875. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2020.112875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Ahmadi S, Fazilati M, Nazem H, Mousavi SM. Green synthesis of magnetic nanoparticles using satureja hortensis essential oil toward superior antibacterial/fungal and anticancer performance. BioMed Res Int. 2021;2021. doi:10.1155/2021/8822645. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Insawang S, Pripdeevech P, Tanapichatsakul C, Khruengsai S, Monggoot S, Nakham T, et al. Essential oil compositions and antibacterial and antioxidant activities of five Lavandula stoechas cultivars grown in Thailand. Chem Biodivers. 2019;16(10). doi:10.1002/cbdv.201900371. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Spinozzi E, Pavela R, Bonacucina G, Perinelli DR, Cespi M, Petrelli R, et al. Spilanthol-rich essential oil obtained by microwave-assisted extraction from Acmella oleracea (L.) RK Jansen and its nanoemulsion: insecticidal, cytotoxic and anti-inflammatory activities. Ind Crops Prod. 2021;172:114027. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2021.114027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Sharma M, Hussain S, Shalima T, Aav R, Bhat R. Valorization of seabuckthorn pomace to obtain bioactive carotenoids: An innovative approach of using green extraction techniques (ultrasonic and microwave-assisted extractions) synergized with green solvents (edible oils). Ind Crops Prod. 2022;175:114257. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2021.114257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. El Kharraf S, El-Guendouz S, Farah A, Bennani B, Mateus MC, El Hadrami E, et al. Hydrodistillation and simultaneous hydrodistillation-steam distillation of Rosmarinus officinalis and Origanum compactum: antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antibacterial effect of the essential oils. Ind Crops Prod. 2021;168:113591. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2021.113591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Xiao Y, Liu ZZ, Gu HY, Yang FJ, Zhang L, Yang L. Improved method to obtain essential oil, asarinin and sesamin from Asarum heterotropoides var. mandshuricum using microwave-assisted steam distillation followed by solvent extraction and antifungal activity of essential oil against Fusarium spp. Ind Crops Prod. 2021;162:113295. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2021.113295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Men Y, Fu SP, Xu C, Zhu YM, Sun YX. Supercritical fluid CO2 extraction and microcapsule preparation of Lycium barbarum residue oil rich in zeaxanthin dipalmitate. Foods. 2021;10(7):1468. doi:10.3390/foods10071468. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Shen J, Shen W, Cai X, Wang JX, Zheng MX. High performance liquid chromatographic method for determination of active components in lithospermum oil and its application to process optimization of lithospermum oil prepared by supercritical fluid extraction. Chin J Chromatogr. 2021;39(7):708–14. doi:10.3724/sp.j.1123.2020.12009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Mihalcea L, Turturica M, Cucolea EI, Danila GM, Dumitrascu L, Coman G, et al. CO supercritical fluid extraction of oleoresins from sea buckthorn pomace: evidence of advanced bioactive profile and selected functionality. Antioxidants. 2021;10(11):1681. doi:10.3390/antiox10111681. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Atiqah MSN, Gopakumar DA, Owolabi FAT, Pottathara YB, Rizal S, Aprilia NAS, et al. Extraction of cellulose nanofibers via eco-friendly supercritical carbon dioxide treatment followed by mild acid hydrolysis and the fabrication of cellulose nanopapers. Polymers. 2019;11(11):1813. doi:10.3390/polym11111813. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Cerón-Martínez LJ, Hurtado-Benavides AM, Ayala-Aponte A, Serna-Cock L, Tirado DF. A pilot-scale supercritical carbon dioxide extraction to valorize colombian mango seed kernel. Molecules. 2021;26(8):2279. doi:10.3390/molecules26082279. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Vidovic S, Tomsik A, Vladic J, Jokic S, Aladic K, Pastor K, et al. Supercritical carbon dioxide extraction of Allium ursinum: Impact of temperature and pressure on the extracts chemical profile. Chem Biodivers. 2021;18(4):e2100058. doi:10.1002/cbdv.202100058. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Hassim N, Markom M, Rosli MI, Harun S. Scale-up approach for supercritical fluid extraction with ethanol-water modified carbon dioxide on Phyllanthus niruri for safe enriched herbal extracts. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):15818. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-95222-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Dimic I, Pezo L, Rakic D, Teslic N, Zekovic Z, Pavlic B. Supercritical fluid extraction kinetics of cherry seed oil: kinetics modeling and ANN optimization. Foods. 2021;10(7):1513. doi:10.3390/foods10071513. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Lee JH, Lee YY, Lee J, Jang YJ, Jang HW. Chemical composition, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory activity of essential oil from omija (Schisandra chinensis (Turcz.) Baill.) produced by supercritical fluid extraction using CO2. Foods. 2021;10(7):1619. doi:10.3390/foods10071619. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Wu Y, Hu YS, Zhao ZG, Xu LN, Chen Y, Liu TT, et al. Protective effects of water extract of Fructus Ligustri Lucidi against oxidative stress-related osteoporosis in vivo and in vitro. Vet Sci. 2021;8(9):198. doi:10.3390/vetsci8090198. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Liu HX, Guo YB, Zhu RY, Wang LL, Chen BB, Tian YM, et al. Fructus Ligustri Lucidi preserves bone quality through induction of canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in ovariectomized rats. Phytother Res. 2021;35(1):424–41. doi:10.1002/ptr.6817. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Kim YJ, Park SY, Koh YJ, Lee JH. Anti-neuroinflammatory effects and mechanism of action of Fructus ligustri lucidi extract in BV2 microglia. Plants. 2021;10(4):688. doi:10.3390/plants10040688. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Lu Q, Xing HZ, Yang NY. Mass spectrometry-based label-free quantitative proteomic analysis of CCl4-induced acute liver injury in mice intervened by total glycosides from Ligustri Lucidi Fructus. Curr Proteomics. 2021;18(3):338–48. doi:10.2174/1570164617999200728192812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Yang NY, Zhang YW, Guo JM. Preventive effect of total glycosides from against nonalcoholic fatty liver in mice. Z Naturforsch C. 2015;70(9–10):237–41. doi:10.1515/znc-2015-4161. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Li G, Zhang XA, Zhang JF, Chan CY, Yew DTW, He ML, et al. Ethanol extract of promotes osteogenesis of mesenchymal stem cells. Phytother Res. 2010;24(4):571–6. doi:10.1002/ptr.2987. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Sha NN, Zhao YJ, Zhao DF, Mok DKW, Shi Q, Wang YJ, et al. Effect of the water fraction isolated from Fructus Ligustri Lucidi extract on bone metabolism antagonizing a calcium-sensing receptor in experimental type 1 diabetic rats. Food Funct. 2017;8(12):4703–12. doi:10.1039/C7FO01259D. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Shen XY, Ma RN, Huang YX, Chen L, Xu ZB, Li DD, et al. Nano-decocted ferrous polysulfide coordinates ferroptosis-like death in bacteria for anti-infection therapy. Nano Today. 2020;35:100981. doi:10.1016/j.nantod.2020.100981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Bunchongprasert K, Shao J. Effect of fatty acid ester structure on cytotoxicity of self-emulsified nanoemulsion and transport of nanoemulsion droplets. Colloid Surface B. 2020;194:111220. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfb.2020.111220. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Parvez MK, Alam P, Arbab AH, Al-Dosari MS, Alhowiriny TA, Alqasoumi SI. Analysis of antioxidative and antiviral biomarkers β-amyrin, β-sitosterol, lupeol, ursolic acid in Guiera senegalensis leaves extract by validated HPTLC methods. Saudi Pharm J. 2018;26(5):685–93. doi:10.1016/j.jsps.2018.02.022. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Su YC, Hsu KP, Composition Ho CL. Composition, in vitro antibacterial and anti-mildew fungal activities of essential oils from twig and fruit parts of eucalyptus citriodora. Nat Prod Commun. 2017;12(10):1647–50. doi:10.1177/1934578X1701201031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Zhao HY, Chen SX, Hu KZ, Zhang ZF, Yan XR, Gao HJ, et al. 5-HTP decreases goat mammary epithelial cells apoptosis through MAPK/ERK/Bcl-3 pathway. Gene. 2021;769:145240. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2020.145240. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Zhou ML, Yi YP, Liu L, Lin Y, Li J, Ruan JH, et al. Polymeric micelles loading with ursolic acid enhancing anti-tumor effect on hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cancer. 2019;10(23):5820–31. doi:10.7150/jca.30865. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools