Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Effects of Surface Herbs on the Growth of Populus L. Cutting Seedling, Soil Property and Ammonia Volatilization

1 Co-Innovation Center for Sustainable Forestry in Southern China, College of Forestry and Grassland, Nanjing Forestry University, Nanjing, 210037, China

2 Co-Innovation Center for Industry-Academy-Research, Linyi Vocational University of Science and Technology, Linyi, 276000, China

3 National Positioning Observation and Research Station of Forest Ecosystem in Changjiang River Delta, Nanjing Forestry Univeristy, Nanjing, 210037, China

* Corresponding Author: Haijun Sun. Email:

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(3), 695-707. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.061790

Received 03 December 2024; Accepted 25 February 2025; Issue published 31 March 2025

Abstract

To promote the growth of cutting seeding of poplar (Populus L.), nitrogen (N) fertilizer and surface weed managements were required. We here conducted a pot experiment to examine the effects of natural vegetation, barnyardgrass (Echinochloa Beauv.), and sesbania (Sesbania cannabina pers.) on the growth of poplar cutting seedlings, soil properties, and ammonia (NH3) volatilization under three N inputs (0, 0.5, and 1.5 g/pot, i.e., N0, N0.5, and N1, respectively). Results showed that N application promoted the growth of poplar cutting seedlings, including plant height, ground diameter, and biomass, compared with N0 treatment. Moreover, under N0, sesbania significantly increased the plant height by 87.1%, barnyardgrass and sesbania significantly increased the ground diameter (16.2% and 51.5%), and biomass (67.4% and 74.7%) of poplar cutting seedlings, compared with natural vegetation management. Compared to natural vegetation, soil organic matter (SOM) of barnyardgrass and sesbania covered soil significantly increased by 12.4% and 18.7% at N1, respectively. In addition, soil total N (TN) content was significantly increased by 15.8% in barnyardgrass planted at N0. The soil ammonium N (NH4+-N) content decreased with the planting of barnyardgrass and sesbania across all levels of N application. At N0.5, the nitrate N (NO3−-N) content of soil planted with barnyardgrass significantly increased compared to both the natural vegetation and the sesbania groups. Compared to the natural vegetation, the soil available phosphorus (AP) content of the barnyardgrass group significantly increasing by 78.8% at N0.5, soil available potassium (AK) content was significantly reduced by 12.5% in the sesbania group at N0 and increased by 24.1% in the barnyardgrass group at N1. We found that cumulative NH3 emissions were significantly higher in all treatment groups at the N1 level than that at the N0.5 level, while the differences among the three plants treated were not significant. The results suggest that both barnyardgrass and sesbania promote seedling growth in the short term, while also increase certain properties. Therefore, effective herb management during the seedling stage is recommended in nurseries to support seedling growth and retain soil fertility.Keywords

Nitrogen (N) is an essential macronutrient for plants [1], and its effectiveness is closely linked to plant growth, yield, and stress responses [2,3]. However, the application of N beyond plant requirements not only impairs plant growth traits but also leads to N losses. These losses include ammonia (NH3) volatilization, runoff and leaching in the soil, both of which decrease N use efficiency [4,5]. NH3 volatilization is a significant source of N fertilizer losses, leading to substantial economic costs. Additionally, atmospheric NH3 is deposited on farmland and water bodies, contributing to soil acidification and water eutrophication [6,7]. Consequently, reducing NH3 volatilization and improving N utilization have become key research challenges. Currently, there has been an increasing body of in-depth research on the volatilization of NH3 from both agricultural and forest soils. For instance, Zhao et al. [8] proposed a comprehensive approach to consider root distribution, N loss, and the use of moso bamboo, as well as to regulate N losses, such as NH3 volatilization, through environmental factors. Zhang et al. [9] demonstrated that the application of N fertilizer and a cover crop mixture both promoted soil NH3 emissions, whereas the introduction of the legume cover crop Vicia villosa Roth reduced soil NH3 volatilization due to a lower soil MBC/MBN ratio. Nursery, as a critical stage in seedling growth, and soil fertilization and management practices are also crucial; however, less attention has been given to NH3 volatilization losses under N fertilizer application conditions in nurseries.

As China’s afforestation area continues to expand, nurseries are also increasing the duration of seedling cultivation. This is attributed to the use of improper nursery and management practices, which have led to a significant decline in soil fertility. This is particularly evident in poplar nurseries, where the continuous nursery system has led to a low survival rate of seedling cuttings, reduced growth potential, and other observable phenomena [10,11]. Therefore, effective herbaceous management for seedlings can be achieved through the implementation of rational fertilization practices, which enhance fertilizer use efficiency, stimulate plant growth, and mitigate N losses [12,13]. Herbaceous plants are a crucial component of nursery grounds, influencing seedling growth and survival [14]. Furthermore, they are essential for improving soil quality and maintaining the stability of the nursery system [15,16]. The presence of herbaceous plants in poplar woodlands has been shown to enhance nutrient cycling due to their ability to accumulate nutrients at a higher rate and their influence on the chemical composition and biomass turnover rate of apoplastic litter [17], which is significantly greater than that of the upper canopy trees [18]. Studies by Qiao et al. [19] and Lin et al. [20] revealed that understory vegetation enhances the organic matter content of forest soils, thereby benefiting nutrient turnover and supporting the sustained productivity of poplar forests. Li et al. [21] concluded that legumes exhibit a high capacity for carbon and N conservation, which can effectively alleviate carbon and N limitations in orchard soils, mitigate the intense competition for water and nutrients between cover plants and citrus trees, and potentially increase orchard yields while promoting sustainable development. Numerous studies have focused on the interactions between the upper and lower vegetation layers of plantation forests; however, there is a lack of research on whether optimized herbaceous management under varying N supply levels differentially affects soil NH3 volatilization, nutrient characteristics, and seedling growth in nursery sites.

In summary, this study investigated the soil NH3 volatilization characteristics of poplar nursery land and the effects of optimized herb management by planting natural vegetation, barnyardgrass, and sesbania under varying N application levels (0, 0.5, and 1.5 g/pot). The study was conducted with the goal of reducing NH3 volatilization losses and providing a scientific basis for enhancing the quality and efficiency of herbaceous plants under seedlings, particularly in the context of chemical fertilizer reduction.

2.1 Experimental Design and Management

The soil used in this experiment was collected from the forest of the North Mountain at Nanjing Forestry University. Soil samples were air-dried for two weeks and then passed through 2 mm and 0.149 mm sieves. The basic characteristics of the soil were determined as follows: pH = 6.95, soil organic matter (SOM) = 7.67 g/kg, total N (TN) = 0.41 g/kg, ammonium N (NH4+-N) = 1.13 mg/kg, nitrate N (NO3−-N) = 0.35 mg/kg, available phosphate (AP) = 9.31 mg/kg, and available potassium (AK) = 64.5 mg/kg. The soil column used in the experiment had a diameter of 30 cm and a depth of 28.5 cm (20 cm of soil), with a bulk density of 1.30 g/cm3 and a total of 20 kg of soil per pot. The site was located at Nanjing Forestry University, and the poplar species used was Siyang No.1. The experimental N treatments were set as no N fertilizer (N0), low N fertilizer (0.5 g/pot, N0.5), and high N fertilizer (1.5 g/pot, N1). Herbaceous management consisted of natural vegetation, barnyardgrass, and sesbania planting. A two-factor combinatorial soil-pillar design was employed, with a total of nine experimental treatments, each replicated three times. This experimental treatment was conducted under the recommended N application conditions for major poplar production areas. The fertilizer input per pot was adjusted based on accumulated experience in potting, along with field usage rates. During the reproductive period of poplar seedlings, conventional management practices were adopted, and fertilizers were applied as follows: N fertilizers were applied at 0.5 and 1.5 g/pot (equivalent to 1.09 and 3.26 g/pot urea), P fertilizers at 0.2 g/pot (equivalent to 1.11 g/pot P2O5), and K fertilizers at 0.1 g/pot (equivalent to 0.19 g/pot KCl). Fertilization was performed twice a year, with half of the annual fertilizer rate applied each time.

2.2 Indicator Measurement and Methods

2.2.1 Poplar Growth Indicators

Plant height: the distance from the root collar, 5 cm above the ground, to the top of the main stem, measured using a tape measure; Ground diameter: measured using a caliper, the diameter of the root collar, 5 cm above the ground, of each seedling was recorded; Number of leaves: the total number of leaves was counted manually at regular intervals; Chlorophyll content: measured using a SPAD chlorophyll meter, three leaves were randomly selected from each plant and measured in triplicate, with the average value taken as the chlorophyll content for each treatment group; Biomass: the fresh and dry weights of the leaves and stems were measured separately, and the biomass was recorded.

Soil pH: measured with air-dried samples at a soil: water ratio of 1:5 using a pH meter (PHS-3C, Leici, Taizhou, China). TN: 0.5 g of sieved dried soil was accurately weighed, treated with concentrated sulfuric acid, and analyzed using the Kjeldahl method. NH4+-N and NO3−-N: 10.0 g of fresh soil was accurately weighed and subjected to leaching with a 2 mol/L hydrochloric acid solution. The resulting solution was analyzed using indophenol blue colorimetry and spectrophotometry. SOM: 0.5 g of dried soil was treated with 5 mL of 0.1333 mol/L potassium dichromate solution and 5 mL of concentrated sulfuric acid, and the content was determined using the oxidation-volumetric method, with potassium dichromate heated in an oil bath. AP: air-dried soil was extracted using hydrochloric-sulfuric acid leaching and subsequently analyzed by the molybdenum antimony colorimetric method. AK: 5.0 g of air-dried soil was subjected to leaching with ammonium acetate and analyzed using flame photometry.

The cumulative loss of NH3 volatilization and the volatilization rate were determined using the sponge method. A proportional mixture of phosphoric acid and glycerol (50 mL of H3PO4 + 40 mL of C3H6O diluted to 1 L) was prepared, and the sponge was moistened with the mixture to absorb NH3 volatilized from the soil. The sponge was placed at 8:00 AM each day, removed, and replaced with a new sponge at 8:00 AM the following day. The top sponge was replaced every 3–7 days, depending on its moisture level. The removed sponges were transported to the laboratory and placed in 500 mL plastic bottles. The sponges were completely immersed in 300 mL of 1.0 mol/L KCl solution, shaken for 1 h, and the immersion extract was aspirated into a 50 mL plastic bottle and refrigerated. NH3 volatilization was continuously measured for one week following fertilizer application. Ammonium N in the leachate was determined using evaporative N determination or a continuous flow analyzer. The amount of NH3 (mg) absorbed by a single NH3 volatilization collection device is calculated using the following equation:

Note: ω represents the amount of NH3 absorbed by a single NH3 volatilization collector (mg), m represents the ammonia N concentration (mg/L) calculated from the calibration curve, V1 represents the volume of the solution (mL) used to determine absorbance after calibration, V2 represents the volume of potassium chloride (KCl) solution used to extract NH3 from the sponge (mL), and V3 represents the volume of the extract used for determination (mL).

2.2.4 Nitrogen Use Efficiency of Poplar

At the end of the fertilization period, the poplar cuttings were brought to the laboratory for processing. The soil on the root system was cleaned with deionized water, and the cuttings were divided into three parts (including roots, stems, and leaves) to determine their fresh weight. The samples were then subjected to rapid killing in an oven at 105°C for 30 min, followed by drying at 80°C until a constant weight was achieved. The dry weights of the roots, stems, and leaves were measured after being removed from the oven. The dried roots, stems, and leaves were ground and passed through a 0.25 mm sieve, and the N content was determined using the Kjeldahl method. Nitrogen use efficiency calculation formula:

Note: NUE represents N utilization (%), NF represents N uptake of N application treatment (g/pot), N0 represents N uptake of control (g/pot), and N represents N application (g/pot).

The experimental data were organized and analyzed using software of Excel 2010 and SPSS 26.0. Data Differences among different N levels and herb types were analyzed separately using one-way ANOVA, followed by multiple comparisons with Duncan’s method. Before used ANOVA, we tested the homogeneity of variances. The effects of N level, herb type, and their interactions on poplar cutting and soil properties were assessed using two-way ANOVA. GraphPad software along with Excel for graphing.

3.1 Growth Indicators of Poplar Cuttings

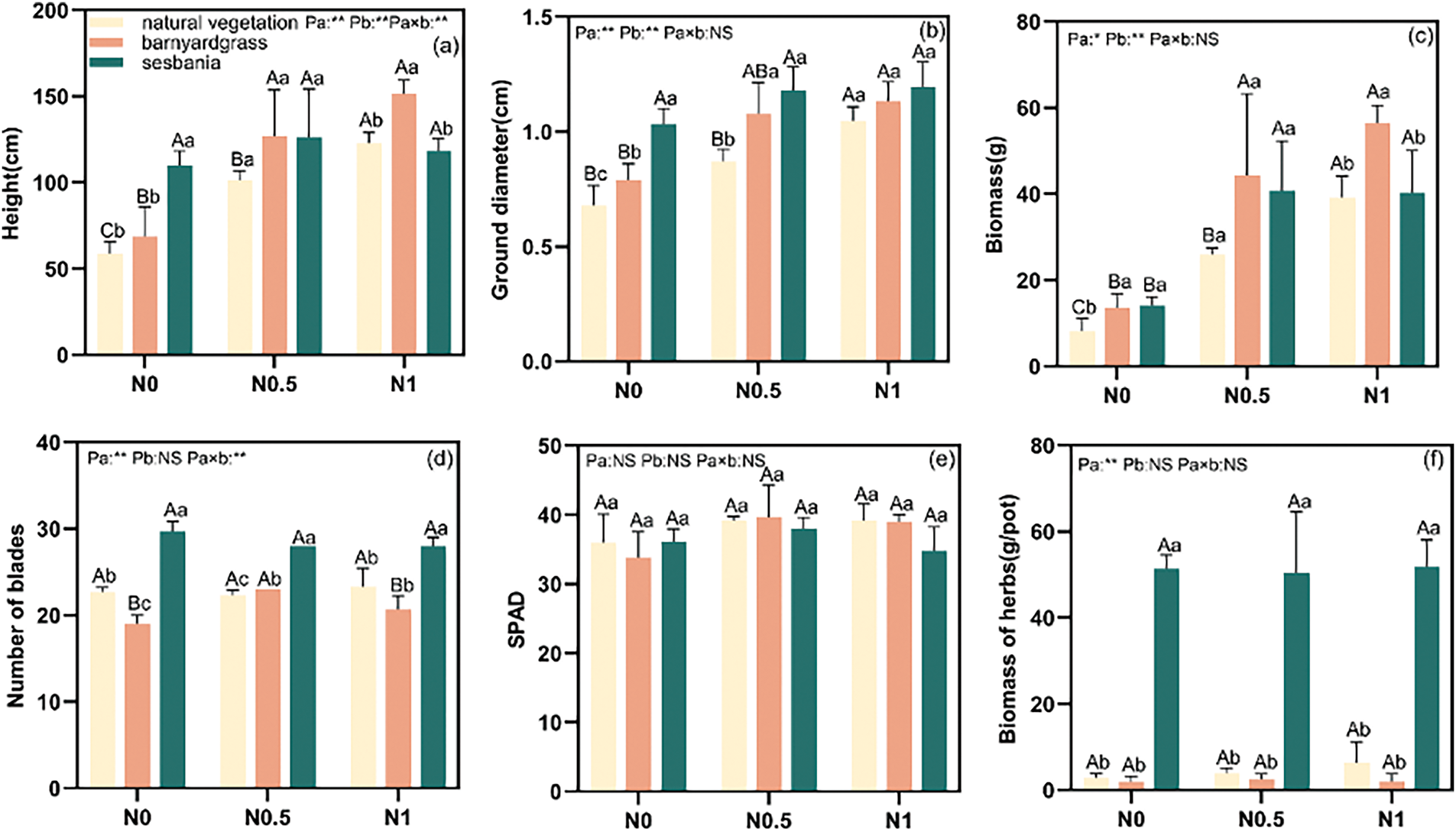

The height of poplar plants exhibited varying trends across the herbaceous management groups under different N supply levels (Fig. 1a), the differences were significant among different herbaceous managements under the same N level, different N levels under the same herbaceous management, and the interaction effects between different herbaceous managements and N levels. At the N0 level, poplar cuttings planted with sesbania experienced a significant 87.1% increase in plant height. At N1 level, plant height in the barnyardgrass group was significantly increased by 28.1% in the sesbania group. However, at N0.5 level, the differences in plant height between barnyardgrass and sesbania treatments was not statistically significant. As shown in Fig. 1b, the ground diameter of poplar trees increased in proportion to their growth. For the ground diameter of poplar cuttings, significant differences were found among different herbaceous managements under the same N level, different N levels under the same herbaceous management. Compared to natural vegetation, poplar cuttings planted with barnyardgrass and sesbania exhibited increases in ground diameter of 16.2% and 51.5% at N0 level, and of 24.1% and 35.2% at N0.5.

Figure 1: Effects of herbaceous optimal management and N supply on plant height (a), ground diameter (b), biomass (c), leaf number (d), leaf chlorophyll content of poplar cuttings (e) and biomass of herbs (f). Note: Uppercase letter indicates significant difference in N application level and lowercase letter indicates significant difference in herbal management (p < 0.05). Pa indicates differences between herbaceous management under the same N level, Pa×b indicates differences between N levels under the same herbaceous management, and Pa×b indicates differences in the interaction effect of different herbs and N levels. (1) NS: p ≥ 0.05, indicating no significant difference; (2) *: p < 0.05, indicating a significant difference at the 0.05 level; (3) **: p < 0.01, indicating significant difference at 0.01 level. The same below

The biomass of poplar under surface herbs ranged from 8.13 to 56.47 g/pot across the three N supply levels (Fig. 1c). The biomass of poplar cuttings planted with barnyardgrass and sesbania was significantly increased by 67.4% and 74.7%, compared to the natural vegetation at N0 level. The interaction between herbaceous managements and N supply levels significantly affected leaf number (Fig. 1d), and the interaction effects between different herbaceous managements and N treatments showed significant differences. At N0, the number of leaves on poplar cuttings planted with sesbania increased significantly by 7 units compared to natural vegetation. At the N0.5 and N1 levels, leaf number in sesbania-planted poplar increased by 4–6 units, respectively. However, optimized herbaceous management had no significant effect on SPAD of poplar cuttings (Fig. 1e). The highest biomass (Fig. 1f) was observed in the sesbania management group, which consistently outperformed both natural vegetation and barnyardgrass across all three N levels, with biomass ranging from 50.5 to 51.8 g/pot. However, no significant differences in herbaceous biomass were observed among the different N treatments.

3.2 N Content and Uptake in Poplar Cuttings

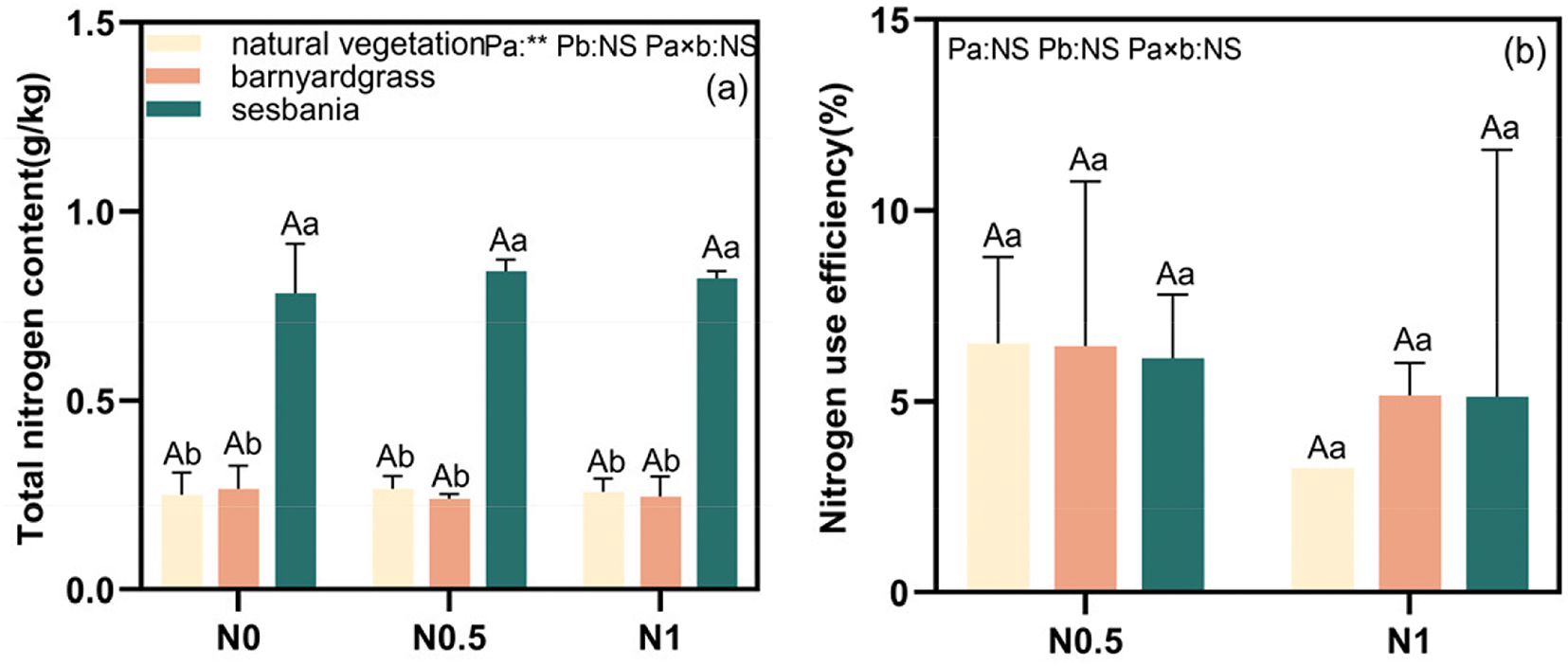

As shown in Fig. 2a,b, at each N level, the sesbania management group exhibited significantly higher total N content compared to both the natural vegetation and barnyardgrass management groups, with increases ranging from 0.518 to 0.603 g/kg. No significant differences were observed between the natural vegetation and barnyardgrass management groups. As N application increased, N utilization by poplar cuttings decreased. Compared to natural vegetation, both the barnyardgrass and sesbania treatments exhibited higher N utilization at N1.

Figure 2: Total N content (a) and N use efficiency (b) of each herb under different N supply levels. Note: Uppercase letter indicates significant difference in N application level and lowercase letter indicates significant difference in herbal management (p < 0.05). (1) NS: p ≥ 0.05, indicating no significant difference; (2) **: p < 0.01, indicating significant difference at 0.01 level

3.3 Soil Fertility Characteristics

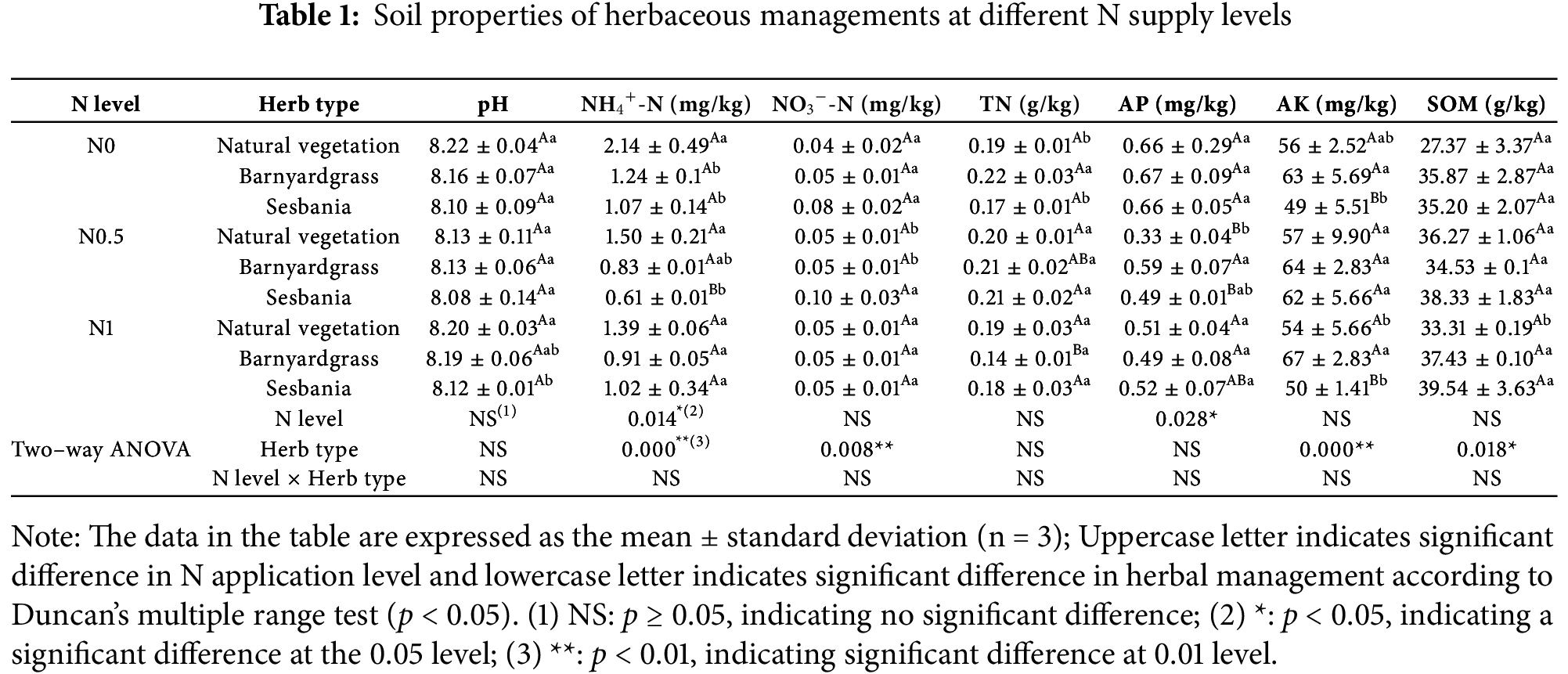

Soil pH was mostly around 8.1 and planting herbs under seedlings had no significant effect on soil pH. In comparison to the natural vegetation, SOM content of poplar cuttings planted with barnyardgrass and sesbania showed a trend of increase, with significant increases of 12.4% and 18.7% at N1, respectively. Soil TN content was significantly increased by 15.8% in barnyardgrass planted compared to that of natural vegetation at the N0 level. Additionally, compared to N0, soil TN content was significantly reduced by 36.4% in the barnyardgrass group at N1. NH4+-N of the soil decreased with the planting of barnyardgrass and sesbania across all levels of N application. In comparison to the natural vegetation, the soil NH4+-N content significantly decreased by 42.1% and 50.0% in the barnyardgrass and sesbania groups at N0, and by 59.3% in the sesbania group at N0.5. At N0.5, NO3−-N content of soil planted with barnyardgrass significantly increased compared to both the natural vegetation and the sesbania group. Compared with the natural vegetation, the soil AP content of poplar cuttings planted with barnyardgrass and sesbania at the three levels of N application exhibited an increasing trend, with the soil AP content of the barnyardgrass group significantly increasing by 78.8% at N0.5. Compared to the natural vegetation, soil AK content was significantly reduced by 12.5% in the sesbania group at N0 and increased by 24.1% in the barnyardgrass group at N1. Furthermore, soil AK content in sesbania planted at N0.5 significantly increased compared to both N0 and N1 (26.5% and 24%). Two-way ANOVA results indicated a significant effect of N level on NH4+-N and AP content, and a significant effect of surface herb on NH4+-N, NO3−-N, AK, and SOM content. Moreover, N level and herb did not exhibit a significant interaction effect on soil properties (Table 1).

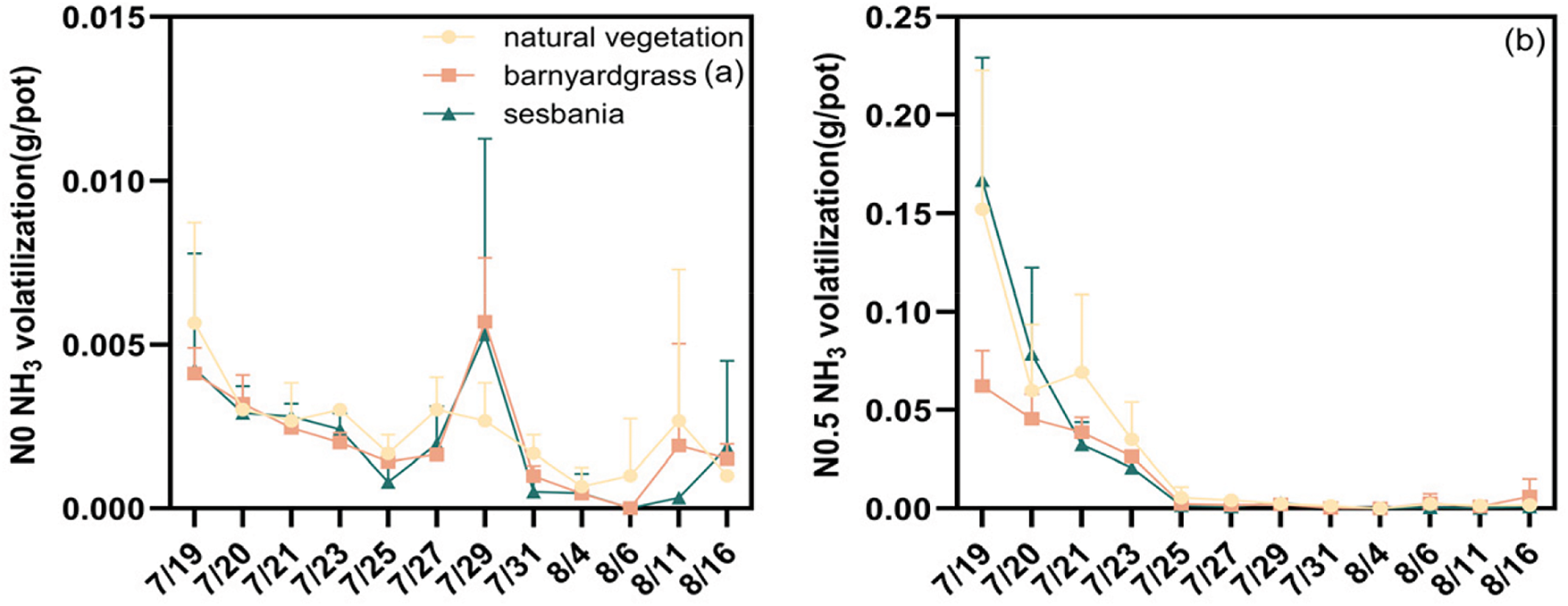

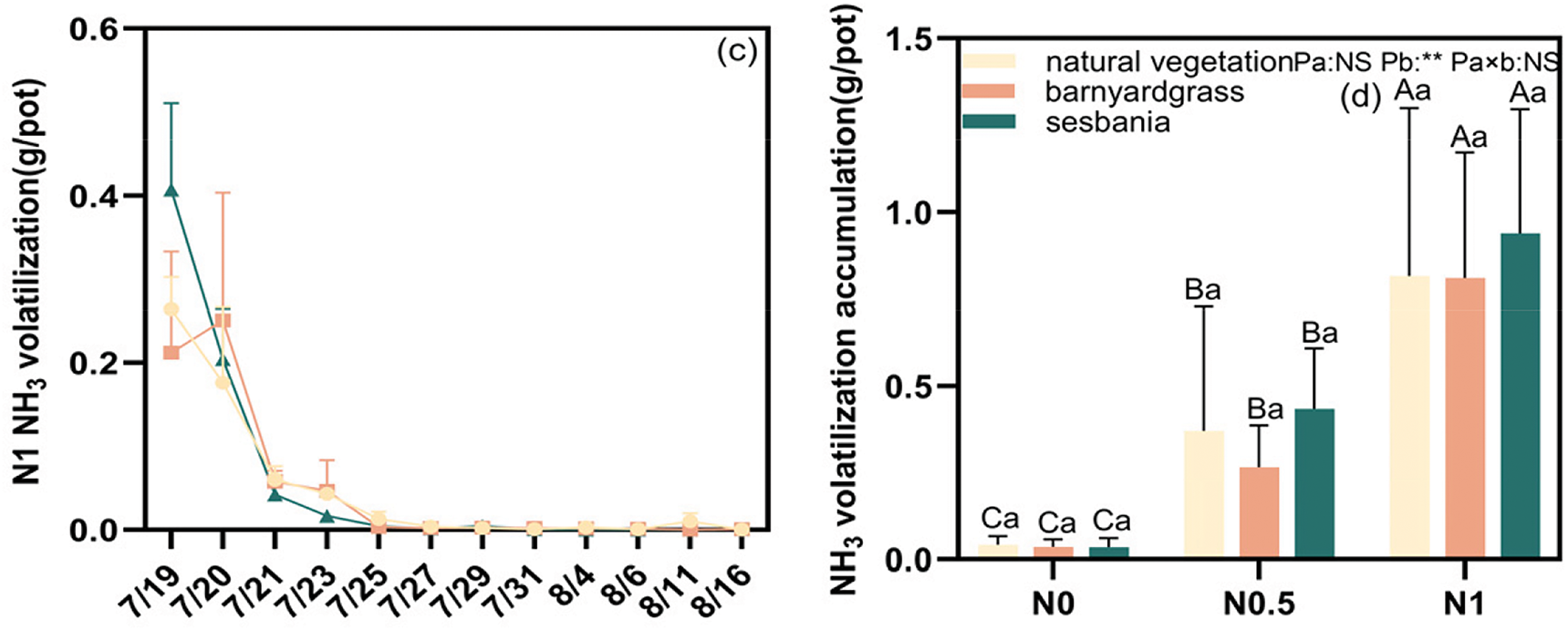

Fig. 3a–c illustrates the effect of herbaceous management and N supply on soil NH3 volatilization rates. Two days after fertilizer application, the NH3 volatilization rate peaked at 0.25 g/pot in the barnyardgrass management group at N1. In contrast, the maximum NH3 volatilization rate in all other treatment groups was observed on the first day after fertilizer application, ranging from 0.06 to 0.41 g/pot. Following the peak, NH3 volatilization rates for each N application and herbaceous management group decreased rapidly, reaching levels similar to the control group by the fifth day after fertilization. The effects of different vegetation cover on soil NH3 volatilization accumulation varied at the three N supply levels (Fig. 3d). No significant differences were observed between the control, barnyardgrass and sesbania groups. When N application was increased from N0.5 to N1, NH3 volatilization increased significantly by 120.3%, 205.4% and 116.2% under natural vegetation, barnyardgrass and sesbania treatments.

Figure 3: Effects of herbal management and N supply on NH3 volatilization accumulation (d) and NH3 volatilization change rate (a–c). Uppercase letter indicates significant difference in N application level and lowercase letter indicates significant difference in herbal management (p < 0.05). (1) NS: p ≥ 0.05, indicating no significant difference; (2) **: p < 0.01, indicating significant difference at 0.01 level. Note: The date of the fertilizer application is 7/18. Observation of NH3 volatilization started at one day after fertilizer application

The results of this study indicate that both barnyardgrass and sesbania treatments promoted the growth of poplar cuttings compared to natural vegetation. The plant height, ground diameter, and biomass of poplar cuttings in both treatment groups mostly increased significantly, consistent with previous studies [22,23]. The nutrient uptake and the effects on the roots of poplar trees were significantly altered following the introduction of herbaceous intercropping [24]. These changes may have contributed to variations in the growth patterns of poplar trees under different herbaceous treatments. Zhu et al. [25] reported that understorey planting of sesbania increased tree height by 18.97% and diameter at breast height by 10.30% compared to the control group, suggesting that planting green manure promotes forest tree growth. The results of the present study were consistent with theirs, with the growth-promoting effect of sesbania on poplar cuttings being more pronounced. This may be attributed to the N-fixing capacity of sesbania, which enhances N supply stability when intercropped with other plants [26]. Additionally, planting N-fixing plants under seedlings can effectively enhance the release of readily available nutrients from the soil at the nursery site, thereby promoting the accelerated growth of poplar cuttings. N uptake by seedlings in nursery sites is influenced by factors such as the amount of N applied and management practices. Controlling N fertilizer application and implementing intercropping can effectively reduce N losses and increase the N available to the crop [27]. The results showed no statistically significant change in TN of poplar content across treatments with increased N application (Fig. 2a). Furthermore, the TN content of poplar in the sesbania group was significantly higher than in the natural vegetation and barnyardgrass groups, suggesting that planting sesbania enhanced the N uptake of poplar cuttings. This aligns with most intercropping experiments involving leguminous plants [28,29]. The biological fixation of N by sesbania has the effect of increasing the N levels present in the soil. Consequently, poplar cuttings absorb more N from the rhizosphere of sesbania [26]. In summary, selecting N0.5 when planting sesbania ensures N uptake and utilization by poplar trees while maintaining a relatively high N use efficiency.

There was no significant change in soil pH when planted natural vegetation, barnyardgrass and sesbania with N supply, and previous studies have shown that the surface vegetation (Sesbania, Brassica juncea) mulching treatments had no significant effect on soil pH [30]. Increased plant species diversity may enhance apoplastic and root exudation, leading to an overall rise in soil N levels due to competitive interactions between species [31,32]. The results of this study indicate that planting barnyardgrass beneath poplar cuttings effectively enhanced the soil TN content at N0 and N0.5 levels. This finding is consistent with Zhao et al. [33], who also reported that agroforestry systems involving intercropping can increase soil carbon and N levels. Soil TN content also increased in the sesbania group at N0.5 level, consistent with Huang et al. [34], who reported that both soil TN and NH4+-N content tended to increase after planting salt-tolerant legumes. This increase was attributed to the symbiotic relationship between legumes and rhizobacteria in the soil, which convert free N into NH4+-N or absorb N directly from the soil for N fixation. Moreover, low N levels may enhance N fixation in sesbania. Some soil properties such as NH4+-N and AP changed significantly with increasing levels of N application, which agrees with Liang et al. [35]. In contrast to previous research, the present study indicates that ground herbs significantly reduce soil NH4+-N content and increase soil NO3−-N content in poplar cuttings. Du et al. [36] demonstrated that most plants prefer nitrate N in soil over ammonium N, resulting in reduced levels. The results of this study may be attributed to the influence of N application on the N uptake characteristics of herbaceous plants. Ansari et al. [37] showed that sesbania, when used as green manure, resulted in the highest total biomass accumulation (>30 Mg/ha) and a notable increase in soil organic carbon (>14 Mg/ha). The findings of the present study align with this observation, as both barnyardgrass and sesbania planted under poplar cuttings showed a marked increase in SOM content. Sesbania is known for its high shoot and root biomass, which leads to a significant increase in total organic carbon content in the soil due to rapid growth [38]. The results of this study showed an increasing trend in AP content in the soil planted with barnyardgrass and sesbania across at N0 and N0.5 application levels. In contrast, Huang et al. [34] found that P and K content in the soil were lower than the control when legumes were planted in the understorey. An increasing trend in soil AK content was observed in poplar cuttings planted with barnyardgrass in this experiment, which may be attributed to the ability of graminaceous plants to significantly reduce K leaching from the soil [39].

Changes in soil NH3 volatilization result from a combination of factors, including climate, soil conditions, and management practices [40], with N application, irrigation, and tillage having a direct influence. The results of this study showed that soil NH3 volatilization was significantly higher in the natural vegetation, barnyardgrass and sesbania groups with increased N application, consistent with the findings of Wen et al. [41], which suggest that high N application is a key driver of increased soil NH3 volatilization. The peak in soil NH3 volatilization occurred one to two days after N application and irrigation, irrespective of the N application rate or herbaceous management. Subsequently, a rapid decrease into a low volatilization phase was observed. This can be attributed to the rapid hydrolysis of urea and the subsequent increase in NH4+-N concentration due to irrigation immediately after N application. This also accelerated its physical diffusion, leading to increased NH3 volatilization loss [42]. The herbaceous plant layer functions as both an NH3 source and sink [43], playing a crucial role in regulating NH3 volatilization in the field. For instance, Lyu et al. [44] found that herbaceous green manure management practices significantly increased NH3 emissions from maize fields, compared to conventional fertilization. Unlike agricultural and forested grassland soils, there has been limited research on NH3 volatilization from poplar nursery soils. The highest levels of NH3 volatilization accumulation were observed in the N1 + sesbania treatment. However, no statistically significant differences were observed between the three herbaceous treatments, indicating that the impact of N application on soil NH3 volatilization accumulation was more pronounced than the influence of the surface herbs. This experiment focused on the chemical properties of the above-ground parts in relation to the soil, and was conducted over a short time period. Further studies are needed on the root system, which is in direct contact with the soil, the physical properties of the soil, and the enzymes and their activities directly related to NH3 volatilization. Such studies would benefit from longer observation periods and larger-scale investigations.

In this study, we investigated the effects of ground herbs on the growth, soil properties, and NH3 volatilization of poplar cuttings under varying N application levels, and reached the following conclusions. Compared to natural vegetation, sesbania led to a significant increase in ground diameter, plant height and leaf number. Regarding plant height and biomass, barnyardgrass had more pronounced promoting effects. Significant differences occur in N levels on soil NH4+-N and AP content. Surface soil NH4+-N, NO3−-N, SOM and AK contents were significantly different in surface herbs. Soil NH3 volatilization accumulation from poplar cuttings increased with higher N application, but no significant differences were observed among the three herbaceous treatments. In conclusion, the implementation of planting barnyardgrass and sesbania facilitated the growth of poplar cuttings compared to natural vegetation, particularly in the sesbania treatment. For soil properties and NH3 volatilization, further investigation into N levels and surface herb types that may interact positively is warranted.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the Science and Technology Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province, China for “Carbon Dioxide Emission Peaking and Carbon Neutrality” (BE2022307).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Sun Haijun; methodology, Chengcheng Yin and Haijun Sun; investigation, Chang Liu, Chengcheng Yin and Jinjin Zhang; data curation, Chang Liu and Jinjin Zhang; writing—original draft preparation, Chang Liu and Chengcheng Yin; writing—review and editing, Jinjin Zhang and Haijun Sun; funding acquisition, Haijun Sun. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declared no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| N | Nitrogen |

| NH3 | Ammonia |

| SOM | Soil Organic Matter |

| TN | Total Nitrogen |

| NH4+-N | Ammonium Nitrogen |

| NO3–-N | Nitrate Nitrogen |

| AP | Available Phosphorus |

| AK | Available Potassium |

References

1. Chen YE, Mao JJ, Sun LQ, Huang B, Ding CB, Gu Y, et al. Exogenous melatonin enhances salt stress tolerance in maize seedlings by improving antioxidant and photosynthetic capacity. Physiol Plant. 2018;164(3):349–63. doi:10.1111/ppl.12737. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Sun JW, Wang SY, Fan DW, Zhu YL. Effects of C, N and P additions on soil respiration in woodland under Cd stress. Nanjing For Univ Nat Sci Ed. 2024;48(1):140–6. doi:10.12302/j.issn.1000-2006.202204011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Arun M, Radhakrishnan R, Ai TN, Naing AH, Lee IJ, Kim CK. Nitrogenous compounds enhance the growth of petunia and reprogram biochemical changes against the adverse effect of salinity. J Hortic Sci Biotechnol. 2016;91(6):562–72. doi:10.1080/14620316.2016.1192961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Tan Y, Xu C, Liu D, Wu W, Lai R, Meng F. Effects of optimized N fertilization on greenhouse gas emission and crop production in the North China Plain. Field Crops Res. 2017;205(5):35–146. doi:10.1016/j.fcr.2017.01.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Guo T, Zhang Q, Ai C, Liang G, He P, Zhou W. Nitrogen enrichment regulates straw decomposition and its associated microbial community in a double-rice cropping system. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):18–47. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-20293-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Nguyen MK, Lin C, Hoang HG, Bui XT, Ngo HH, Tran HT. Investigation of biochar amendments on odor reduction and their characteristics during food waste co-composting. Sci Total Environ. 2023;865(2):161128. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.161128. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Wan X, Wu W, Liao Y. Mitigating ammonia volatilization and increasing nitrogen use efficiency through appropriate nitrogen management under supplemental irrigation and rain-fed condition in winter wheat. Agric Water Manag. 2021;255:107050. doi:10.1016/j.agwat.2021.107050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Zhao J, Su W, Fan S, Cai C, Su H, Zeng X. Ammonia volatilization and nitrogen runoff losses from moso bamboo forests after different fertilization practices. Can J For Res. 2019;49(3):213–20. doi:10.1139/CJFR-2018-0017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Zhang Z, Wang J, Huang W, Chen J, Wu F, Jia Y, et al. Cover crops and N fertilization affect soil ammonia volatilization and N2O emission by regulating the soil labile carbon and nitrogen fractions. Agric Ecosyst Environ. 2022;340(6):108–88. doi:10.1016/j.agee.2022.108188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Xi B, Clothier B, Coleman M, Duan J, Hu W, Li D, et al. Irrigation management in poplar (Populus spp.) plantations: a review. For Ecol Manag. 2021;494(6):119330. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2021.119330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Wang XM. Has the three norths forest shelterbelt program solved the desertification and dust storm problems in arid and semiarid China? J Arid Environ. 2021;74(1):13–22. doi:10.1016/j.jaridenv.2009.08.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Guo W, Han X, Zhang L, Wang Y, Du H, Yan Y, et al. Morphological, photosynthetic physiological and transcriptome analyses of Pteroceltis tatarinowii in response to different nitrogen application levels. Nanjing For Univ Nat Sci Ed. 2023;47(5):87–96. doi:10.12302/j.issn.1000-2006.202108019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Ashiq MW, Bazrgar AB, Fei H, Coleman B, Vessey K, Gordon A, et al. A nutrient-based sustainability assessment of purpose-grown poplar and switchgrass biomass production systems established on marginal lands in Canada. Can J Plant Sci. 2018;98(2):255–66. doi:10.1139/CJPS-2017-0220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Pitt DG, Morneault A, Parker WC, Stinson A, Lanteigne L. The effects of herbaceous and woody competition on planted white pine in a clearcut site. For Ecol Manag. 2009;257(4):1281–91. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2008.11.039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Muller RN. Nutrient relations of the herbaceous layer in deciduous forest ecosystems. The herbaceous layer in forests of eastern North America. New York, NY, USA: Oxford University Press; 2003. p. 15–37. [Google Scholar]

16. Deng J, Fang S, Fang X, Jin Y, Kuang Y, Lin F, et al. Forest understory vegetation study: current status and future trends. For Res. 2023;3(1). doi:10.48130/FR-2023-0006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Xi Y, Zhang L, Xu YH, Cheng W, Chen C. Physiological and biochemical responses of perennial ryegrass mixed planting with legumes under heavy metal pollution. Phyton. 2024;93(7):1749–1765. doi:10.32604/phyton.2024.051793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Liming C, Lei D, Xiu LM. Soil enzyme activities and plant diversity of undergrowth in spruce-fir forest. J Northeast For Univ. 2009;37(3):58–61. doi:10.1016/j.elecom.2008.10.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Qiao Y, Miao S, Silva LCR, Horwath WR. Understory species regulate litter decomposition and accumulation of C and N inforest soils: a long-term dual-isotope experiment. For Ecol Manag. 2014;329(6):318–27. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2014.04.025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Lin GG, Mao R, Zhao L, Zeng DH. Litter decomposition of a pine plantation is affected by species evenness and soil nitrogen availability. Plant Soil. 2013;373(1–2):649–57. doi:10.1007/s11104-013-1832-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Li W, Liu Y, Duan J, Liu G, Nie X, Li Z. Leguminous cover orchard improves soil quality, nutrient preservation capacity, and aggregate stoichiometric balance: a 22-year homogeneous experimental site. Agric Ecosyst Environ. 2024;363:108876. doi:10.1016/j.agee.2023.108876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Morhart C, Sheppard J, Seidl F, Spiecker H. Influence of different tillage systems and weed treatments in the establishment year on the final biomass production of short rotation coppice poplar. Forests. 2013;4(4):849–67. doi:10.3390/f4040849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Mrnka L, Schmidt CS, Švecová EB, Vosátka M, Frantík T. Impact of legume intercropping on soil nitrogen and biomass in hybrid poplars grown as short rotation coppice. Biomass Bioenergy. 2024;182(12):107081. doi:10.1016/j.biombioe.2024.107081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Kabba BS, Knight JD, Van Rees KCJ. Growth of hybrid poplar as affected by dandelion and quackgrass competition. Plant Soil. 2007;298(1–2):203–17. doi:10.1007/s11104-007-9355-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Zhu KX, Wang HL, Qin ZY, Tang J, Deng XJ, Cao JZ, et al. Effect of green manure crop interplanting on soil fertility and plant growth of eucalyptus urophylla × E.grandis plantation. J Zhejiang For Sci Technol. 2021;41(6):37–43. (In Chinese). doi:10.3969/j.issn.1001-3776.2021.06.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Oldroyd GED, Downie JA. Coordinating nodule morphogenesis with rhizobial infection in legumes. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2008;59(1):519–46. doi:10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092839. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Gong X, Wang X, Dang K, Zhang Y, Ji X, Long A, et al. Nitrogen availability of mung bean in plant-soil system and soil microbial community structure affected by intercropping and nitrogen fertilizer. Appl Soil Ecol. 2024;203(1):105692. doi:10.1016/j.apsoil.2024.105692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Lan Y, Zhang H, He Y, Jiang C, Yang M, Ye S. Legume-bacteria-soil interaction networks linked to improved plant productivity and soil fertility in intercropping systems. Ind Crops Prod. 2023;196(3):116504. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2023.116504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Wang Y, Zhang Y, Yang Z, Fei J, Zhou X, Rong X, et al. Intercropping improves maize yield and nitrogen uptake by regulating nitrogen transformation and functional microbial abundance in rhizosphere soil. J Environ Manag. 2024;358:120886. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.120886. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Zhang J, Cui SY. Effects of straw and vegetation cover on soil salinity and fertility properties in beach swidden areas. Soil Fertil Sci China. 2018;(3):128–35. doi:10.11838/sfsc.20180320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Laganière J, Cavard X, Brassard BW, Paré D, Bergeron Y, Chen HY. The influence of boreal tree species mixtures on ecosystem carbon storage and fluxes. For Ecol Manag. 2015;354:119–29. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2015.06.029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Wang M, Yang J, Gao H, Xu W, Dong M, Shen G, et al. Interspecific plant competition increases soil labile organic carbon and nitrogen contents. For Ecol Manag. 2020;462:117991. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2020.117991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Zhao F, Yang B, Zhu X, Ma S, Xie E, Zeng H, et al. An increase in intercropped species richness improves plant water use but weakens the nutrient status of both intercropped plants and soil in rubber-tea agroforestry systems. Agric Water Manag. 2023;284(8):108353. doi:10.1016/j.agwat.2023.108353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Huang K, Kuai J, Jing F, Liu X, Wang J, Lin J, et al. Effects of understory intercropping with salt-tolerant legumes on soil organic carbon pool in coastal saline-alkali land. J Environ Manag. 2024;370(1–2):122677. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.122677. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Liang XJ, An W, Li YK, Wang Y, Qin X, Cui Y, et al. Impact of different rates of nitrogen supplementation on soil physicochemical properties and microbial diversity in Goji Berry. Phyton-Int J Exp Bot. 2024;93(3):467–86. doi:10.32604/phyton.2024.047628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Du CQ, Zhou GQ, Yuan H, Wang LK, Lei J, Xu YZ. Comprehensive evaluation of soil fertility in different stand ages in Chinese firshort rotation plantation. J For Environ. 2021;41(3):255–62. (In Chinese). doi:10.13324/j.cnki.jfcf.2021.03.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Ansari MA, Choudhury BU, Layek J, Das A, Lal R, Mishra VK. Green manuring and crop residue management: effect on soil organic carbon stock, aggregation, and system productivity in the foothills of Eastern Himalaya (India). Soil Tillage Res. 2022;218(1):105318. doi:10.1016/j.still.2022.105318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Pooniya V, Shivay YS, Rana A, Nain L, Prasanna R. Enhancing soil nutrient dynamics and productivity of Basmati rice through residue incorporation and zinc fertilization. Eur J Agron. 2012;41:28–37. doi:10.1016/j.eja.2012.03.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Littke KM, Harrington TB, Slesak RA, Holub SM, Hatten JA, Gallo AC, et al. Impacts of organic matter removal and vegetation control on nutrition and growth of Douglas-fir at three Pacific Northwestern long-term soil productivity sites. For Ecol Manag. 2020;468(2):118176. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2020.118176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Lin Z, Dai Q, Ye S, Wu FG, Jia YS, Chen JD, et al. Effects of nitrogen application levels on ammonia volatilization and nitrogen utilization during rice growing season. Rice Sci. 2012;19(2):125–34. doi:10.1016/S1672-6308(12)60031-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Wen S, Cui N, Gong D, Xing L, Wu Z, Zhang Y, et al. Effect of nitrogen fertilizer management on N2O emission and NH3 volatilization from orchards. Soil Tillage Res. 2024;242:106165. doi:10.1016/j.still.2024.106165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Xie WM, Li SJ, Shi WM, Zhang HL, Fang F, Wang GX, et al. Quantitatively ranking the influencing factors of ammonia volatilization from paddy soils by grey relational entropy. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2020;27(2):2319–27. doi:10.1007/s11356-019-06952-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Luiz SE, González VHA, Bendassolli JA, Ocheuze TPC. Fertilizer nitrogen and corn plants: not all volatilized ammonia is lost. Agron J. 2018;110(3):1111–8. doi:10.2134/agronj2017.07.0372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Lyu H, Li Y, Yu A, Hu F, Chai Q, Wang F, et al. How do green manure management practices affect ammonia emissions from maize fields? Agric Ecosyst Environ. 2024;367:108971. doi:10.1016/j.agee.2024.108971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools