Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Ecological Factors Influencing Morphology and Tropane Alkaloid Content in Anisodus tanguticus (Maxim.) Pascher

1 Anhui Provincial Engineering Laboratory for Efficient Utilization of Featured Resource Plants, College of Life Sciences, Huaibei Normal University, Huaibei, 235000, China

2 Chinese Academy of Sciences Key Laboratory of Tibetan Medicine Research, Northwest Institute of Plateau Biology, Xining, 810008, China

* Corresponding Author: Guoying Zhou. Email:

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(3), 973-986. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.062421

Received 18 December 2024; Accepted 06 February 2025; Issue published 31 March 2025

Abstract

Anisodus tanguticus (Maxim.) Pascher, a medicinal plant in the Solanaceae family, is widely distributed across the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Its medicinal properties, particularly the tropane alkaloids, are influenced by various ecological factors, but the underlying ecological mechanisms remain poorly understood. This study aimed to investigate how key environmental variables influence both the morphological traits and tropane alkaloid contents of A. tanguticus, with the goal of providing data to support the sustainable cultivation and management of this species. We collected samples from 71 sites across its natural habitat, analyzing the effects of factors such as soil nutrients, altitude, and climate variables on plant traits and alkaloid composition. Statistical methods including Pearson correlation analysis, multiple regression, random forest analysis, and structural equation modeling were used to identify key environmental drivers. Our results indicate that available phosphorus significantly affects aboveground traits, while Cu concentration is most influential for root development. Altitude and longitude were found to be the main determinants of biomass accumulation. Regarding alkaloid content, Mg concentration in the soil was closely linked to anisodine levels, while altitude and latitude were the primary factors influencing anisodamine and atropine content, respectively. These findings provide essential insights into the ecological factors that govern the growth and medicinal compound production in A. tanguticus. Our research not only contributes to understanding the plant’s ecological requirements but also offers practical guidelines for selecting optimal cultivation conditions to enhance both yield and alkaloid quality, supporting sustainable use and conservation of this valuable medicinal resource.Keywords

In China, over 13,000 plant species are recognized for their medicinal properties, with more than 1000 found on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau [1]. The unique ecological conditions of the plateau, characterized by high altitude, extreme climate fluctuations, abundant ultraviolet radiation, long sunshine durations, and enhanced photosynthesis, contribute to the high accumulation of bioactive compounds in its flora [2]. These conditions, along with the plateau’s geographical isolation, create an ideal environment for a rich diversity of medicinal plant species. Located primarily at altitudes above 4000 m, the plateau’s low atmospheric pressure and oxygen availability pose significant challenges to plant life, limiting essential physiological processes like photosynthesis and respiration. To adapt, native plant species have developed specialized physiological and morphological traits, such as enhanced photosynthetic efficiency, alterations in metabolic pathways, and increased stomatal density, all of which help optimize oxygen use. Additionally, the harsh climatic conditions—extreme temperature fluctuations and intense solar radiation—further stress plant growth and survival, leading to unique ecological strategies that enable these plants to endure in such a demanding environment.

Generally, morphological variation is a product of both genetic and environmental variation. Each organism has its own unique morphology and structure, which result from the combination of long-term evolution and environmental selection. The morphological traits of plants are the most direct reflection of their response to the environment [3]. The morphological traits of plants with different geographical distributions can reveal the morphological differences and response strategies to environmental changes among different areas within their spatial distribution. Plant secondary metabolites are a large group of organic substances that are synthesised in plants but are not directly used for plant growth or reproduction. The secondary metabolites in plants are widely regarded as an important characteristic of plant responses to external environmental variation and play an important role in plant defence against herbivorous insects, resistance to pathogenic bacteria, and response to environmental stressors [4,5].

A. tanguticus is a plant in the Solanaceae family that is endemic to the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau and is an important Tibetan medicinal material in China. The traditional Tibetan book “Zangyaozhi” reported that A. tanguticus is known as “Tang Chong Nabao” in Tibetan medicine [6]. A. tanguticus is commonly used to treat acute enteritis, ulcer disease, bruises, redness, swelling and poison, malignant sores and pain [6]. The species is mainly distributed in Qinghai, Sichuan, Yunan, Gansu and Tibet, and it grows on mountain slopes, grasslands, river beaches and shrublands [7]. A. tanguticu can survive in different environments and thus must have special structural characteristics and physiological and ecological adaptation mechanisms.

Phytochemical studies of A. tanguticus have shown that the species contains coumarin compounds, hydroxycinnamic acid amides, and tropane alkaloids [8–10]. Tropane alkaloids are natural products with a long-known, important medicinal value. Recognised for their medicinal purposes for two thousand years, tropane alkaloids are widely used as muscarinic acetylcholine antagonists, targeting the parasympathetic nervous system, and they are mainly used for analgesia, anesthesia, antispasmodics, anti-motion sickness, and Parkinson’s disease treatment [11–13]. Previous studies have reported that tropane alkaloids, including anisodine, anisodamine, and atropine, are the main compounds in A. tanguticus [14,15]. A. tanguticus, as a source of tropane alkaloids, has attracted increasing attention from pharmaceutical companies, but how environmental factors affect the content of tropane alkaloids and their morphological characteristics is unknown.

The morphological characteristics and secondary metabolite content of herbs are affected by different ecological factors, such as geographical, climatic, and soil factors [16,17]. Geographical factors (altitude, landform, aspect, longitude, and latitude) can cause changes in other environmental factors, such as sunshine duration, temperature, and precipitation, thereby indirectly affecting growth and development [18,19]. Soil conditions affect the growth and development of medicinal plants and play an important role in the quality of herbal medicines [20]. Climatic factors such as temperature and precipitation are important ecological factors that affect plant growth and the physiological and biochemical processes of plants, such as transpiration and photosynthesis [21,22]. The Qinghai-Tibet Plateau experiences drastic temperature fluctuations, particularly between day and night, with temperature differences often exceeding 20°C. These temperature extremes impose substantial stress on plant growth and metabolism, affecting both their cellular structures and biochemical pathways. Many species have developed deep root systems to access groundwater from deeper soil layers, while others exhibit xerophytic adaptations, such as thick, waxy cuticles and specialized stomata that minimize water loss. However, plants in this region have evolved a wide range of physiological and biochemical adaptations to survive and thrive under these stress conditions. These adaptations, which include altered photosynthetic pathways, enhanced water-use efficiency, and the production of secondary metabolites, allow plants to maintain metabolic stability and reproductive success despite the harsh environment.

The purpose of this study was to explore the influence of different ecological factors on the morphological traits and tropane alkaloid production in A. tanguticus, using statistical analysis methods. The findings provide not only a scientific basis for resource protection but also a theoretical framework for the artificial breeding and cultivation of A. tanguticus germplasm resources. By elucidating the environmental and genetic factors that regulate the production of bioactive compounds, such as alkaloids, this study identifies the key conditions essential for the growth and survival of these species. Such insights can inform conservation strategies designed to protect these plants in their natural habitats, as well as guide the establishment of ex-situ conservation programs, including seed banks and botanical gardens, to preserve the genetic diversity of these valuable species.

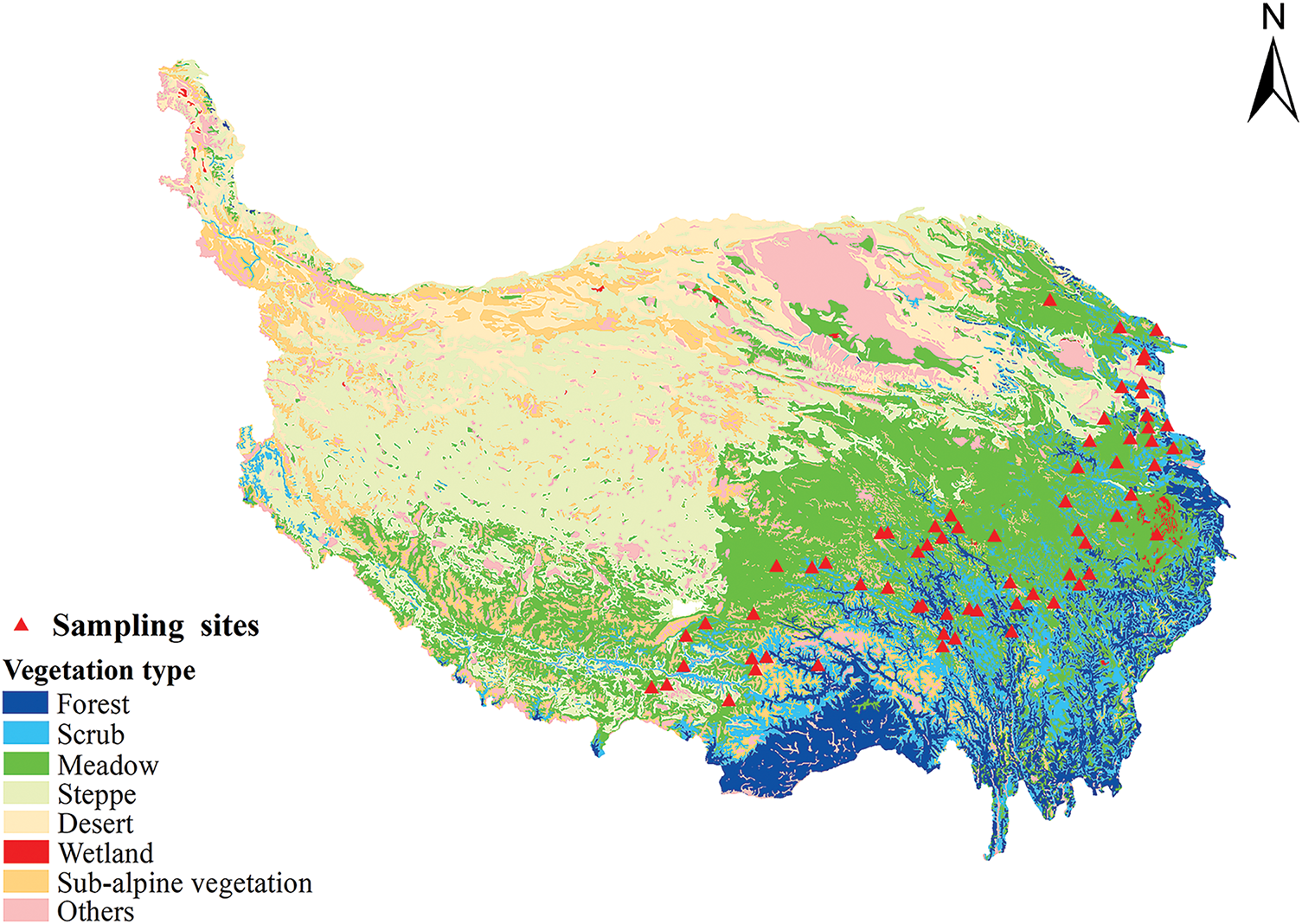

The growth sites of A. tanguticus were first identified from the China Digital Herbarium and the NSII China National Specimen Resource Platform, with duplicate data and closely located regions being removed. Sample collection was then carried out at the selected sites, which largely encompassed areas known for the growth of A. tanguticus. At each site, fresh, disease-free plants were randomly selected for sampling. A total of five plants were sampled per site, with a minimum distance of 10 m maintained between individual samples to ensure spatial independence. In total, samples were collected in Qinghai, Gansu, Sichuan, and Tibet (China) in August, 2023. The 71 sampling sites are shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Geographical distribution of A. tanguticus collected in Qinghai, Gansu, Sichuan, and Tibet (China)

2.2 Morphological Determination

No de-greening process was performed. The plant samples were directly placed in an oven for drying at 60°C until they reached a constant weight. This drying process was employed to preserve the chemical integrity of the active compounds. After drying, the samples were weighed to determine both the underground and aboveground biomass.

Plant height was measured from the base of the plant to the highest point of the stem using a ruler. The measurement was taken in triplicate for each sample to ensure accuracy. The length of each leaf was measured from the petiole to the tip of the leaf blade using a ruler, while the width was measured at the widest point. For consistency, the longest leaf was selected for measurement, and the process was repeated for five leaves from each plant. Root length was measured after carefully washing the soil off the root system. A ruler was used to measure the longest root from the root tip to the main stem.

2.3 Determination of Tropane Alkaloid Content

The content of anisodine, anisodamine and atropine in whole dry root parts were determined by HPLC [9]. The extraction and determination processes were performed according to Chen [9]. Briefly, 0.2 g of sample was extracted with 6 mL methanol (2% formic acid) and 4 mL water (2% formic acid) using a sonicator at 1500 W power for 30 min at room temperature. The suspension was filtered through a 0.22 μm membrane filter before the next analysis step. Anisodine, anisodamine and atropine content analyses were performed on Agilent 1260 equipment (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The HPLC mobile phases were H2O with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (solvent A) and acetonitrile with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (solvent B). The elution gradient was 25 min for 10% B. The flow rate was 1.0 mL/min, the column temperature was 30°C, and the detection wavelength was 215 nm.

2.4 Climatic Factors Collection

Meteorological data were obtained from the global meteorological data website (http://www.worldclim.org/) (accessed on 05 February 2025) using ArcGIS software to extract the climatic data corresponding to the longitude and latitude of each sample. The downloaded data resolution was 30 arcseconds, and data were collected for the climate factors of 71 sites. Nineteen climate factors were downloaded, including average annual temperature (Bio 1), the monthly mean of the temperature difference between day and night (Bio 2), the ratio of the temperature difference between day and night to the annual temperature difference (Bio 3), temperature seasonal variation variance (Bio 4), the hottest month maximum temperature (Bio 5), the coldest month minimum temperature (Bio 6), range of annual temperature changes (Bio 7), the wettest season average temperature (Bio 8), the driest quarterly average temperature (Bio 9), the warmest seasonal average temperature (Bio 10), average temperature of the coldest season (Bio 11), average annual precipitation (Bio 12), the wettest month precipitation (Bio 13), driest monthly precipitation (Bio 14), variance of seasonal variation in precipitation (Bio 15), precipitation in the wettest season (Bio 16), precipitation in the driest season (Bio 17), precipitation in the warmest season (Bio 18), and precipitation in the coldest season (Bio 19).

2.5 Determination of Soil Factors

Soil samples were collected from the root zone of plants at each site to ensure the representativeness of the soil surrounding the plants. The sampling depth was 10 to 20 cm, achieved using a soil auger to minimize contamination from surface layers. Five locations within each site were sampled, and composite samples were prepared by mixing the individual samples.

Specifically, 0.2 g soil samples from different sites were weighed into PTFE crucibles; 5 mL hydrofluoric acid, 2 mL hydrochloric acid and 3 mL perchloric acid were added; and the samples were soaked overnight. After overnight incubation, the samples were placed on a hot plate for wet digestion, and after complete digestion, the acid was rushed. After nearly drying, the sample was then fixed with deionised water for volumetric volume, and the volume was fixed in a 50 mL volumetric flask, filtered, and tested [23]. After the ICP–OES state was stabilised, the analytical lines of the instrument were corrected, and the standard solution, blank solution, and solution to be measured were determined sequentially. Finally, the total P (TP), total K (TK), aluminium (Al), calcium (Ca), cobalt (Co), cuprum (Cu), ferrum (Fe), magnesium (Mg), manganese (Mn), molybdenum (Mo), natrium (Na), vanadium (V), and zinc (Zn) were determined.

The determination of total nitrogen (TN) in soil was conducted following the Chinese standard LY/T 1228-2015. A 0.2 g portion of the soil sample was placed into a digestion tube, to which sulfuric acid and a catalyst (such as selenium or mercury) were added. The sample was then heated for digestion, converting the organic nitrogen in the soil into ammonium ions (NH4+). After digestion, the released ammonia gas was distilled and absorbed by a sodium hydroxide solution. The ammonia concentration was determined by titration with a standard acid solution. Finally, the total nitrogen content in the sample was calculated based on the measured ammonia concentration.

The determination of soil organic matter was conducted according to the Chinese standard DB12/T 961-2020 method. A 0.2 g sample was placed into a glass digestion tube. To the tube, 10.00 mL of 0.4 mol/L potassium dichromate-sulfuric acid solution was added. The tube was then placed in a heating oven, ensuring the internal temperature of the tube was maintained between 170°C and 180°C. After digestion, the tube was removed from the heat source and allowed to cool for 30 min. Three drops of phenanthroline indicator were added to the solution, and titration was carried out using a standard ferrous sulfate solution. The organic matter content was then calculated based on the volume of ferrous sulfate solution consumed during titration.

The determination of available phosphorus in soil was performed using the Chinese standard NY/T 1121.7-2014 method, A 10 g soil sample is placed in a 50 mL centrifuge tube and extracted with 0.5 mol/L sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3) solution for 30 min. The mixture is filtered to separate the liquid from the soil. To the filtrate, ammonium molybdate and ascorbic acid reagent are added, forming a phosphomolybdate complex with available phosphorus. The absorbance at 880 nm is measured using a spectrophotometer, and the phosphorus concentration is determined from a standard calibration curve.

The soil pH determination was conducted following the Chinese standard NY/T 1377-2007 method. A 10 g soil sample was weighed and placed into a beaker, to which 25 mL of distilled water was added. The mixture was sealed and stirred for 5 min using a blender. After stirring, the sample was allowed to stand for 2 h to ensure proper equilibration. The pH value of the soil sample was then measured using a pH meter.

The determination of soil water content was carried out following the Chinese standard NY/T 52-1987 method. A 10 g soil sample was placed in a pre-weighed weighing bottle. The sample was then dried in an oven at 105°C until a constant weight was achieved, typically requiring 24 h. After drying, the sample was removed from the oven, allowed to cool to room temperature, and weighed again to obtain the dry weight. The moisture content was calculated by the difference between the wet and dry weights.

Pearson correlation analysis was performed using SPSS Statistics (version 22, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). To assess relationships between environmental factors. Variables with correlations (r > 0.7) were flagged as potential sources of multicollinearity, which could affect model stability and parameter estimation.

Random forest analysis was conducted using R software (version 4.1.2, Vienna, Austria) and the randomForest package (version 4.6-14) to address multicollinearity. The random forest algorithm was designed to minimize multicollinearity by utilizing random subsets of predictors in multiple decision trees. Additionally, a measure of variable importance was provided by the random forest algorithm, identifying the most influential predictors for the model.

Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was performed using AMOS 21.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) to model the complex relationships between environmental variables and the growth of A. tanguticus. Potential multicollinearity issues were reviewed, and problematic variables were either removed or combined to improve model fit and stability.

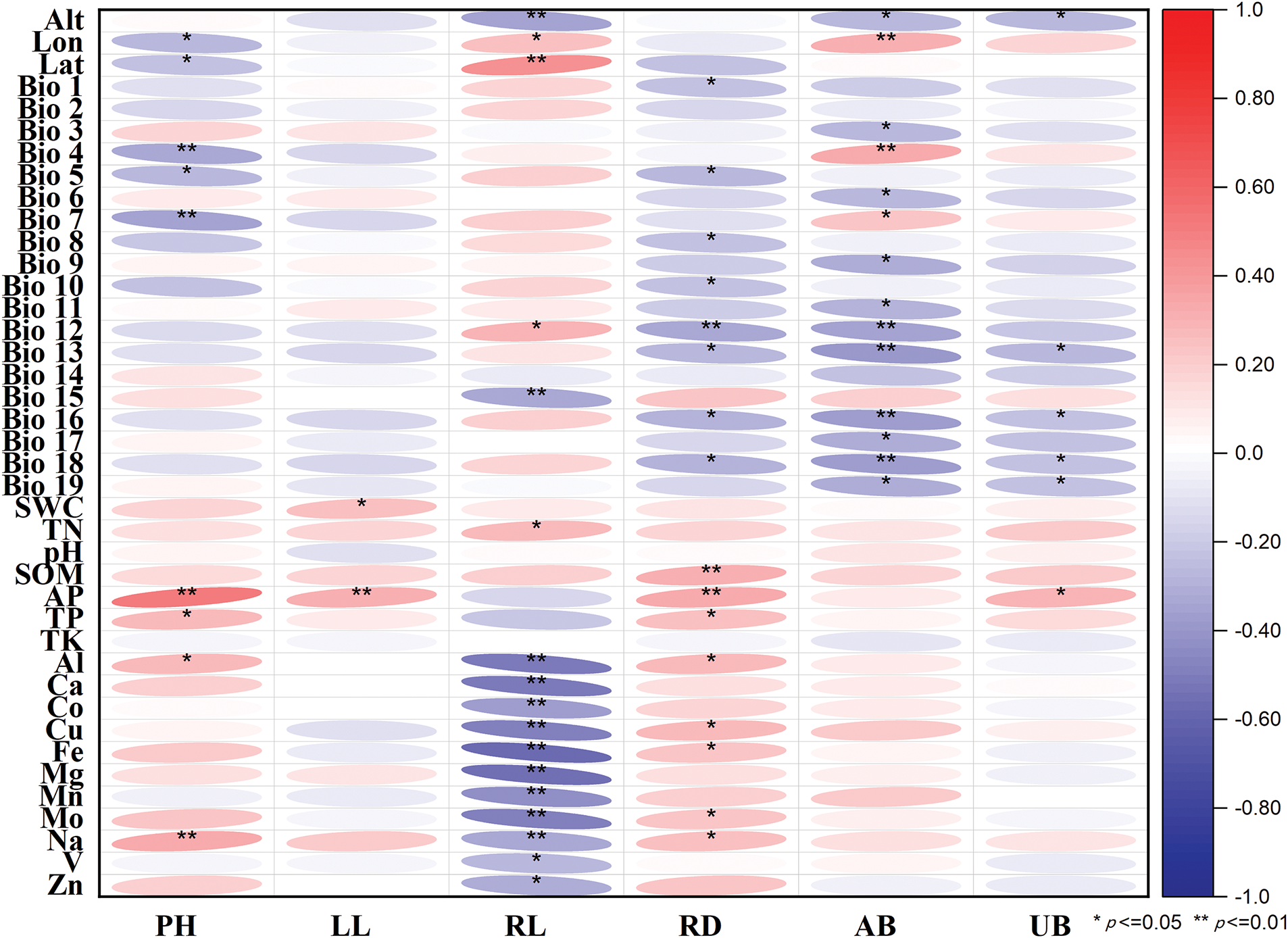

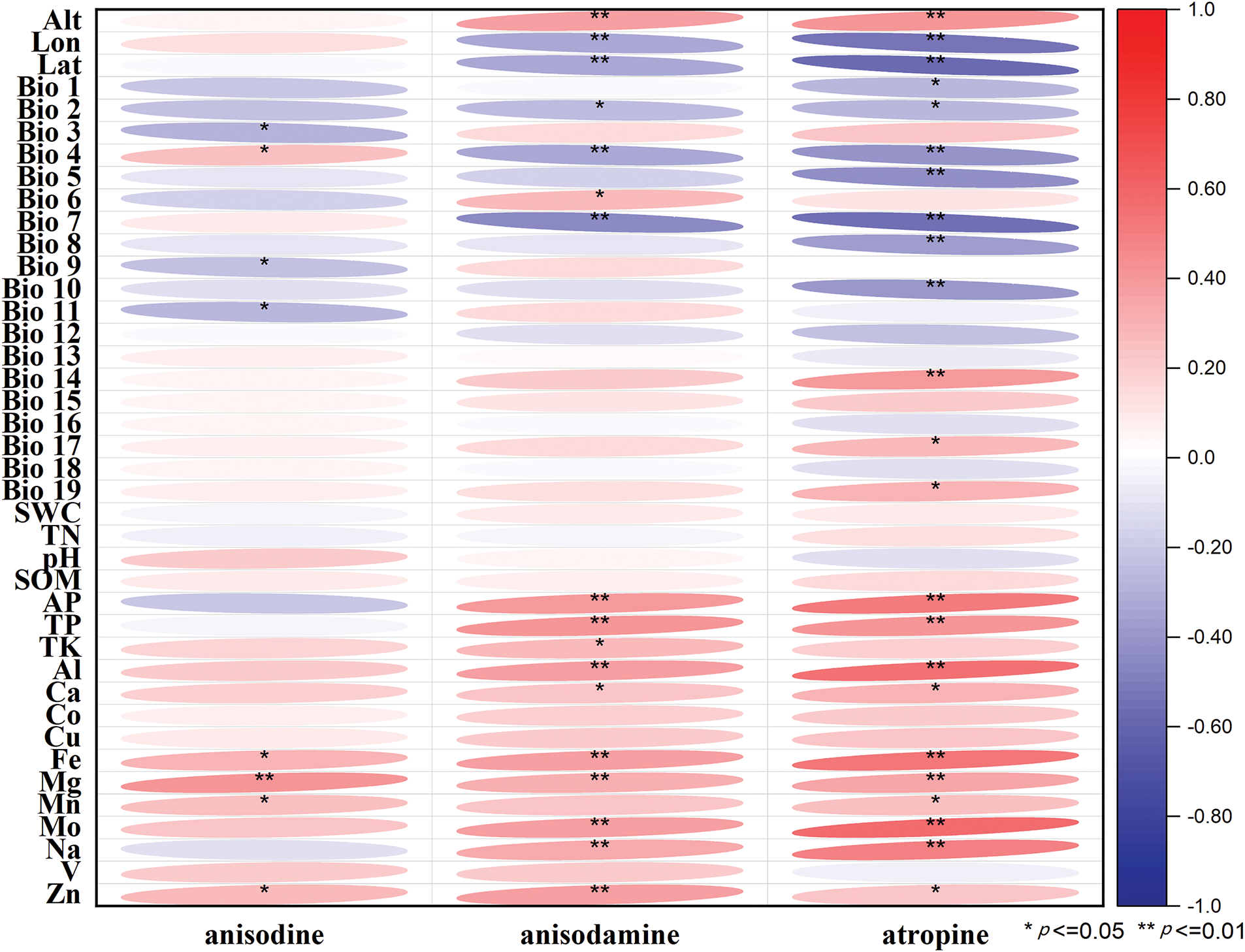

3.1 Correlation Analysis between Morphological Traits, Tropane Alkaloids, and Environmental Factors

As shown in Fig. 2, the overall coefficient between the plant morphological traits and ecological factors was approximately −0.4 to 0.5 (p < 0.05). The content of tropane alkaloids in A. tanguticus was selected for correlation analysis with geographical factors, climatic factors, and soil factors (Fig. 3). The overall coefficient was approximately −0.6 to 0.5 (p < 0.05). Although these correlations are statistically significant, it is essential to acknowledge that other unmeasured factors could influence these results.

Figure 2: Correlation analysis between six morphological traits and forty ecological factors. Red and blue blocks show positive and negative correlations, respectively

Figure 3: Correlation analysis between three tropane alkaloids and forty ecological factors. Red and blue blocks show positive and negative correlations, respectively

3.2 Multiple Stepwise Regression Analysis between Morphological Traits, Tropane Alkaloids, and Environmental Factors

The multiple stepwise regression equations are as follows:

Plant height = 70.94 + 3.34 × available phosphorus;

Leaf length = 11.28 + 0.23 × available phosphorus − 0.014 × Cu;

Root length = 51.097 − 0.001 × Fe + 2.55 × total nitrogen − 0.01 × Ca + 0.01 × K;

Root diameter = 13.15 + 0.027 × soil organic matter − 0.010 × Bio 12;

Aboveground biomass = 611.22 − 4.69 × Bio 13 − 24.25 × Bio 9;

Underground biomass = −1291.39 + 33.54 × available phosphorus + 44.75 × longitude;

Total plant biomass = 2212.02 − 6.15 × Bio 13 − 0.28 × longitude + 25.71 × available phosphorus.

The multiple stepwise regression analysis thus demonstrated a significant relationship between morphological traits and various geographical, soil, and climatic factors. However, it is crucial to consider that other confounding variables, not included in the model, could influence the results.

Similarly, the regression analysis for tropane alkaloid content yielded the following equations:

Anisodine = 0.058 + 0.0006 × Mn − 0.069 × available phosphorus + 0.003 × Zn;

Anisodamine = 2.662 − 0.066 × Bio7 + 0.002 × V

Atropine = 68.052 − 0.43 × latitude − 0.188 × Bio15 − 0.01 × Bio12 + 0.005 × Fe − 0.012 × Cu.

3.3 Random Forest Analysis between Morphological Traits, Tropane Alkaloids, and Environmental Factors

For morphological traits, the factors with the greatest influence on plant height were available phosphorus, Bio 4, Bio 7, Na, Ph, Zn, soil water content, Bio 2, and Cu, with the first four significantly correlated (p < 0.05). Leaf length was most influenced by Bio 4, Na, available phosphorus, Fe, pH, longitude, K, Bio 12, Bio 15, and total nitrogen. Root length was significantly influenced by Cu, Fe, Mg, Bio 7, Bio 9, and Bio 11, with the first four factors strongly correlated (p < 0.05). The factors impacting root diameter were smaller, with P, Bio 7, longitude, Mg, Al, and Cu being the most important. Aboveground biomass was influenced by Zn, Cu, Bio 7, N, and Na, while longitude, altitude, Bio 4, Bio 7, Bio 9, and Bio 13 were significantly correlated (p < 0.05). The most important factors for underground biomass were Bio 4, longitude, AP, Bio 7, Na, phosphorus, Bio 6, altitude, soil water content, Bio 3, and Co, with altitude, available phosphorus, and phosphorus showing significant correlations (p < 0.05).

For tropane alkaloids, the factors most influencing anisodine content were Mg, Bio 3, Zn, Bio 13, Bio 11 (p < 0.05). Anisodamine content was influenced by altitude, V, available phosphorus, Bio 7, Zn, phosphorus, K, Co, Fe, and pH, with the first seven factors significantly correlated (p < 0.05). Atropine content was primarily influenced by latitude, Na, soil water content, Bio 7, Bio 4, Bio 3, and Al (p < 0.01).

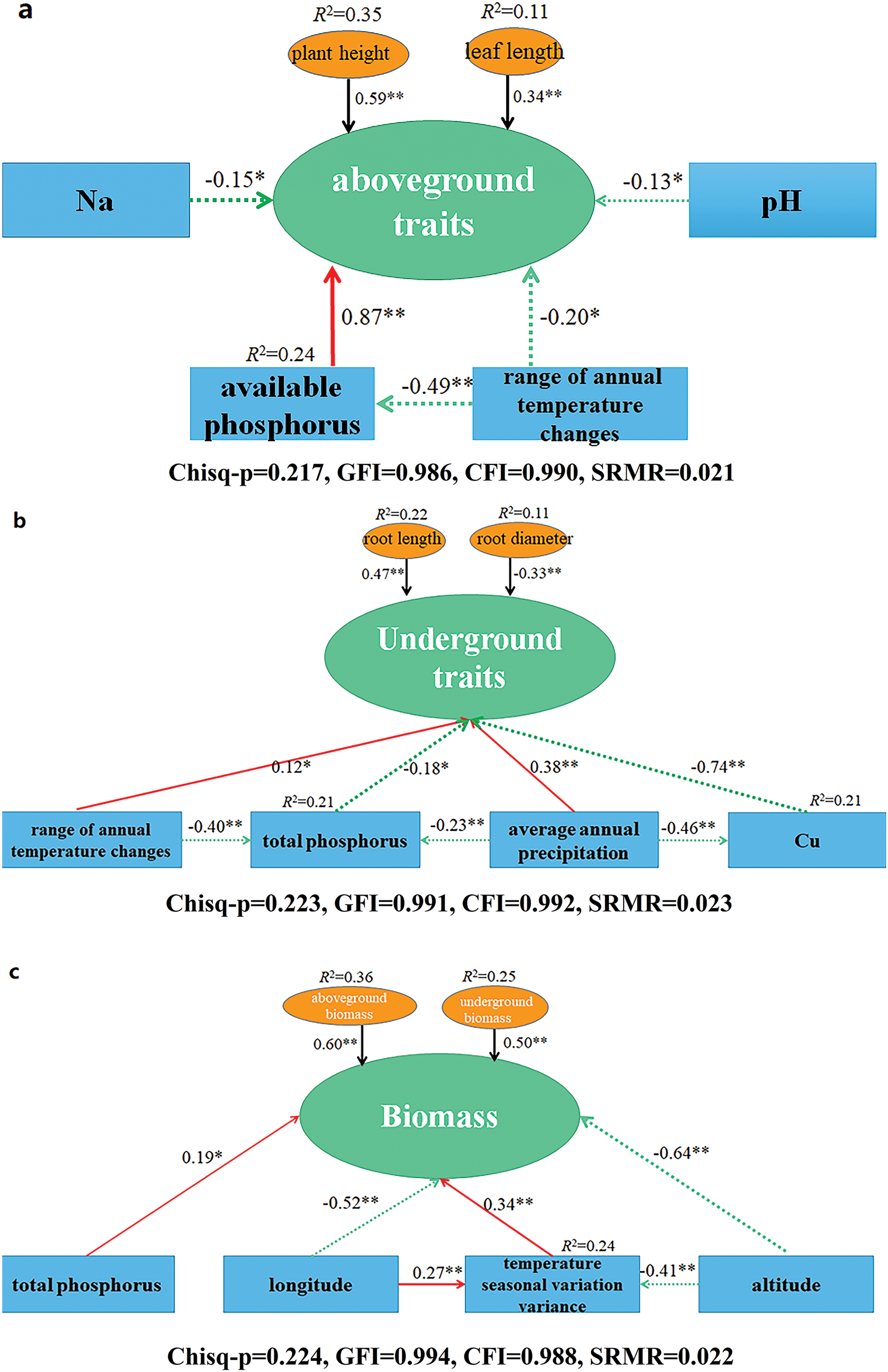

3.4 Structural Equation Modeling Analysis between Morphological Traits, Tropane Alkaloids, and Environmental Factors

For aboveground traits (plant height and leaf length), available phosphorus, Bio7, pH, and Na were selected as independent variables, with available phosphorus having the largest positive influence, while Bio7, Na, and pH had negative effects (RMSEA = 0.069, p > 0.05). For underground traits (root length and root diameter), Bio7, Bio12, total phosphorus, and Cu were used as independent variables. Cu had the most significant negative influence, while Bio12 and Bio7 had positive effects (RMSEA = 0.063, p = 0.27). In terms of biomass (aboveground and underground), altitude had the greatest negative effect, while Bio4 and TP had positive effects (RMSEA = 0.054, p = 0.09) (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: Structural equation modeling analysis between morphological traits and environmental factors. (a) Structural equation modeling analysis between aboveground traits (plant height, leaf length) and four environmental factors (Na, available phosphorus, range of annual temperature changes, pH). (b) Structural equation modeling analysis between underground traits (root length, root diameter) and four environmental factors (Cu, total phosphorus, range of annual temperature changes, average annual precipitation). (c) Structural equation modeling analysis between Biomass (aboveground biomass and underground biomass) and four environmental factors (longitude, total phosphorus, temperature seasonal variation variance, altitude). The direction of the arrow indicates causality, the number on the arrow represents normalized path coefficient, and line thickness is positively correlated with significance; the red line indicates a positive and significant relationship, the green line indicates a significant negative relationship. A single asterisk (*) and double asterisk (**) indicate a significant difference between the variables at p < 0.05 and p < 0.01, respectively

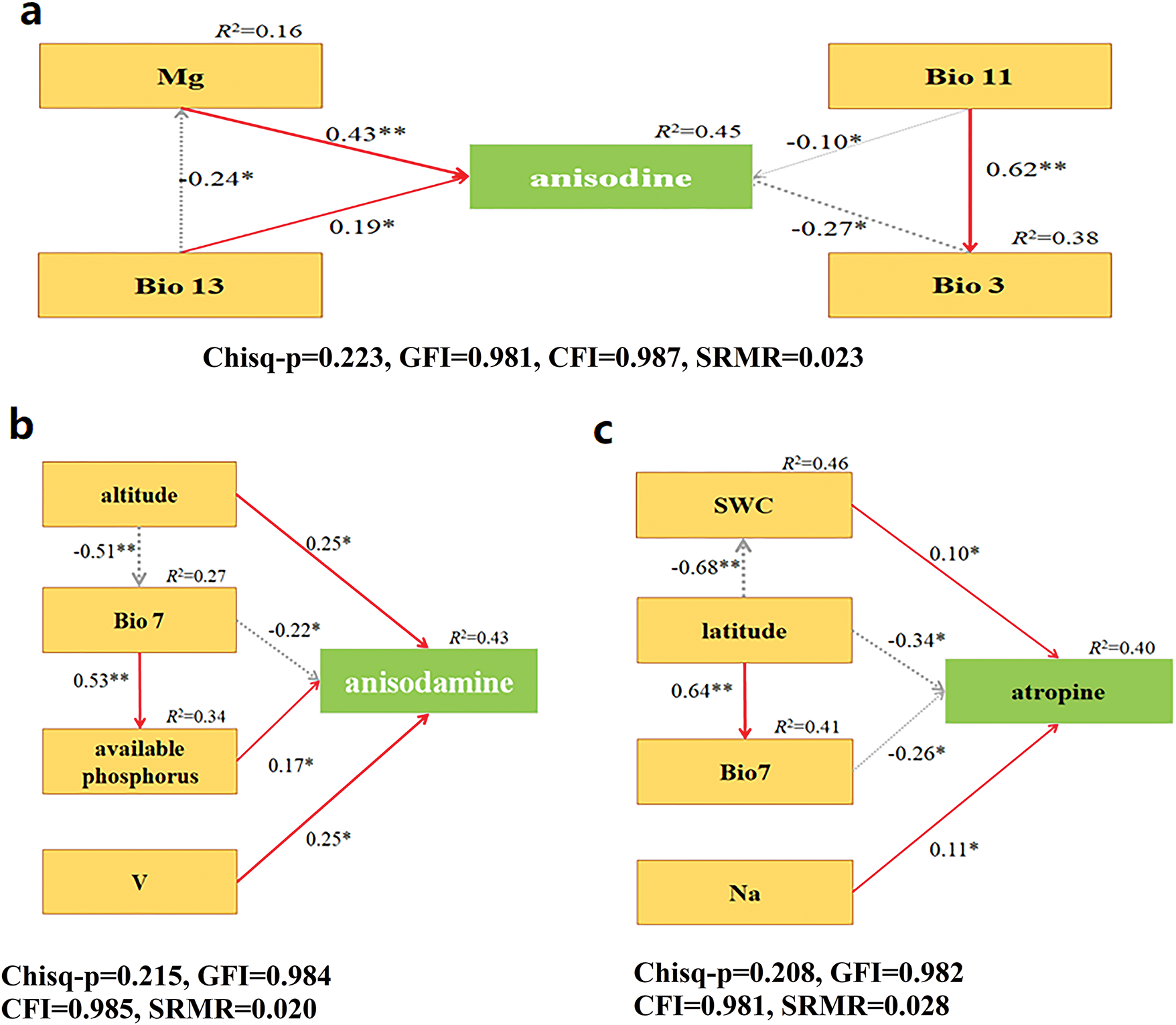

For tropane alkaloids, the structural equation modeling results showed that Mg had the most significant positive effect on anisodine content, while Bio 3 had a negative effect (RMSEA = 0.046, p > 0.05). For anisodamine, altitude and V had positive effects, while Bio 7 had a negative effect (RMSEA = 0.066, p > 0.05). Atropine content was most influenced by latitude, which had a strong negative effect, followed by Bio 7, soil water content, and Na, with Bio7 also showing a negative influence (RMSEA = 0.062, p > 0.05) (Fig. 5).

Figure 5: Structural equation modeling analysis between tropane alkaloids and environmental factors. (a) Structural equation modeling analysis between anisodine and four environmental factors (Mg, Bio 3, Bio 11, Bio 13). (b) structural equation modeling analysis between anisodamine and four environmental factors (altitude, Bio 7, available phosphorus, V). (c) Structural equation modeling analysis between atropine and four environmental factors (SWC, Bio 7, Na, latitude). The direction of the arrow indicates causality, the number on the arrow represents normalized path coefficient, and line thickness is positively correlated with significance; the red line indicates a positive and significant relationship, the green line indicates a significant negative relationship. The ratio of the temperature difference between day and night to the annual temperature difference (Bio 3), range of annual temperature changes (Bio 7), average temperature of the coldest season (Bio 11), the wettest month precipitation (Bio 13). A single asterisk (*) and double asterisk (**) indicate a significant difference between the variables at p < 0.05 and p < 0.01, respectively

The morphological traits of aboveground parts in plants play a critical role in their adaptation to environmental conditions, influencing key processes such as photosynthesis and transpiration efficiency. These traits reflect plants’ strategies for resource acquisition and energy exchange under varying environmental conditions [24]. In this study, A. tanguticus exhibited a resource acquisition strategy whereby increased phosphorus availability positively affected aboveground traits, including plant height and leaf length (Fig. 2). This finding aligns with previous studies suggesting that phosphorus can promote leaf growth, thereby enhancing photosynthetic efficiency [25,26]. In contrast, our results also show that phosphorus had a negative effect on underground traits, which is consistent with the findings of Levang-Brilz, who noted that plants under nutrient stress, particularly phosphorus deficiency, tend to allocate more resources to root development [27].

Cu is a trace element essential for numerous plant physiological processes, including enzymatic activities and photosynthesis [28]. However, excessive Cu can induce oxidative stress and inhibit root growth by disrupting root meristem function and affecting hormonal regulation [29]. Our study revealed that Cu had a significant negative impact on the underground traits of A. tanguticus (Fig. 4), highlighting its sensitivity to high Cu concentrations, which is in agreement with the findings of Gong et al. [29]. Moreover, the role of precipitation in reducing Cu concentration by leaching ions deeper into the soil further emphasizes the dynamic relationship between environmental factors and plant physiology.

Recent studies have extensively investigated the impact of average annual temperature on plant morphology, but fewer have explored the effect of the annual temperature variation range [30]. In our study, the annual temperature variation was found to significantly influence both aboveground and underground traits of A. tanguticus (Fig. 4). Large temperature fluctuations were shown to negatively affect aboveground traits, such as plant height and leaf length, while promoting the development of underground traits, such as root length and diameter. These results support the idea that plants in harsh environments may adapt by increasing root growth to optimize resource acquisition, a mechanism that aligns with the resource access hypothesis [31].

Secondary metabolites are essential in plant defense mechanisms and are influenced by various environmental factors, including temperature, precipitation, and soil nutrients. Environmental stressors often lead to changes in the production of these metabolites, enhancing the plant’s resistance to biotic and abiotic stresses. The interaction between these factors and their effects on secondary metabolite production can be understood through several ecological hypotheses, including the optimal defense hypothesis and the resource access hypothesis [31].

In this study, we observed that A. tanguticus accumulated anisodine, anisodamine, and atropine in response to various ecological factors. Random forest analysis identified key factors influencing anisodine content, including Mg, Bio 3, Bio 13, and Bio 11, with Mg having the strongest positive effect. Structural equation modeling further revealed that Mg, an essential ion for chloroplast proteins, positively influenced anisodine accumulation (Fig. 5). Larger temperature variations were also associated with higher anisodine accumulation, suggesting that environmental stress in areas with greater temperature fluctuations promotes increased secondary metabolite production.

Similarly, altitude, V, available phosphorus, and Bio 7 were identified as significant factors influencing anisodamine accumulation. Higher altitudes and increased phosphorus levels were positively correlated with increased anisodamine content, suggesting that these factors may enhance the plant’s production of this alkaloid [32]. These results align with the resource acquisition hypothesis, where plants at higher altitudes may increase secondary metabolite production as a strategy to adapt to environmental stresses.

Our findings suggest that available phosphorus plays a crucial role in enhancing both the growth and tropane alkaloid content of A. tanguticus. Therefore, for artificial cultivation settings, it is recommended to enrich the soil with phosphorus to optimize both biomass production and alkaloid accumulation. Phosphorus supplementation will not only support robust aboveground biomass but also improve photosynthetic efficiency and overall plant health. Furthermore, altitude emerged as a key factor influencing anisodamine accumulation, with higher altitudes promoting greater alkaloid content. This indicates that selecting cultivation sites at higher elevations could be beneficial for maximizing the medicinal value of A. tanguticus, particularly for the production of alkaloids like anisodamine, which are critical for pharmaceutical use. The data used in this study were collected over a relatively short period. Long-term studies that account for seasonal and interannual variability are needed to better understand how A. tanguticus responds to environmental changes over time, particularly with respect to its growth and medicinal properties.

This study identifies the key ecological factors influencing the morphological traits and tropane alkaloid content of A. tanguticus, revealing significant variation in these traits across different locations. Among the ecological factors examined, available phosphorus was found to have the most significant impact on the aboveground traits, such as plant height and leaf length, while altitude was the key factor influencing the accumulation of tropane alkaloids, particularly anisodamine. Temperature variation also played an important role in shaping plant growth and alkaloid production. These findings highlight the critical role of specific ecological factors in optimizing both the growth and medicinal potential of A. tanguticus.

Our results have important implications for the conservation and cultivation of A. tanguticus, particularly in identifying optimal environmental conditions for cultivation. Understanding how these ecological factors regulate metabolic pathways and alkaloid production can guide the development of more efficient cultivation strategies to maximize the plant’s medicinal value. The innovative aspect of this study lies in the integration of advanced statistical methods, such as structural equation modeling and random forest analysis, to uncover complex relationships between environmental factors and plant traits.

To further advance our understanding of the ecological factors influencing A. tanguticus, future research should focus on long-term field studies to assess the impact of fluctuating environmental conditions over time and investigate the mechanisms through which these factors regulate metabolic pathways. This would provide deeper insights into the ecological adaptability of A. tanguticus and further contribute to its sustainable use and conservation.

Acknowledgement: We thank Xiaoyan Jia, Jingjing Li, and Shoulan Bao (Chinese Academy of Sciences Key Laboratory of Tibetan Medicine Research, Northwest Institute of Plateau Biology, Xining, China) for sampling assistance.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by Qinghai Science and Technology Achievement Transformation Project (2021-SF-149), Natural Science Fund of Education Department of Anhui Province (2024AH051669) and Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program for College Students (S202410373040), Anhui Provincial College Student Innovation and Entrepreneurship Project (20221502032). School-Level Quality Engineering Project of Huaibei Normal University (2024xjsxyj003).

Author Contributions: Guoying Zhou designed the experiments; Chen Chen and Bo Wang established and validated the methods. Fengqin Liu, Jianan Li, Tao Sun and Yuanming Xiao were involved in writing the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets generated analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Zhao RS, Xu SJ, Song PF, Zhou X, Zhang Y, Yuan Y. Distribution patterns of medicinal plant diversity and their conservation priorities in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Biod Sci. 2022;30:21385–485. doi:10.17520/biods.2021385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Yang YX, Hu ZY, Lu FQ, Cai Y, Yu HP, Guo RX, et al. Progress of recent 60 years’ climate change and its environmental impacts on the Qinghai-Xizang Plateau. Plat Mete. 2022;41:1–10. doi:10.7522/j.issn.1000-0534.2021.00117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Hjalmarsson I, Ortiz R. In situ and ex situ assessment of morphological and fruit variation in Scandinavian sweet cherry. Sci Hortic. 2000;85:37–49. doi:10.1016/S0304-4238(99)00123-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Agrawal AA, Weber MG. On the study of plant defense and herbivory using comparative approaches: How important are secondary plant compounds. Ecol Lett. 2015;18:985–91. doi:10.1111/ele.12482. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Laemke JS, Unsicker SB. Phytochemical variation in treetops: causes and consequences for tree insect herbivore interactions. Oecologia. 2018;187:377–88. doi:10.1007/s00442-018-4087-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Yang YC, Zang YZ. Xining: Qinghai People’s Publishing Press; 1991. 142 p. [Google Scholar]

7. Wan DS, Feng JJ, Jiang DC, Mao KS, Duan YW, Miehe G, et al. The quaternary evolutionary history, potential distribution dynamics, and conservation implications for a Qinghai-Tibet Plateau endemic herbaceous perennial, Anisodus tanguticus. Ecol Evol. 2016;6:1977–95. doi:10.1002/ece3.2019. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Zhang XF, Wang H. The variation of the contents of four TAs in Anisodus tanguticus. Acta Bot Boreal. 2002;22:630–4. doi:10.1016/j.arabjc.2024.105730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Chen C, Li JJ, Xiong F, Wang B, Xiao YM, Zhou GY. Multivariate statistical analysis of tropane alkaloids in Anisodus tanguticus (Maxim.) Pascher from different regions to trace geographical origins. Acta Chromatogr. 2022;34:422–9. doi:10.1556/1326.2021.00952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Zhang FY, Qiu F, Zeng JL, Xu Z, Tang Y, Zhao T, et al. Revealing evolution of tropane alkaloid biosynthesis by analyzing two genomes in the Solanaceae family. Nat Commun. 2023;14:1446. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-37133-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Oniszczuk A, Waksmundzka-Hajnos M, Gadzikowska M, Podgórski R, Oniszczuk T. Influence of sample preparation methods on the quantitation of selected TAs from herb of Datura innoxia Mill. by HPTLC.Acta Chromatogr. 2013;25:545–54. doi:10.1556/ACHROM.25.2013.3.10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Qiu F, Yan YJ, Zeng JL, Huang JP, Zeng L, Zhong W, et al. Biochemical and metabolic insights into hyoscyamine dehydrogenase. ACS Catal. 2021;11:2912–24. doi:10.1021/acscatal.0c04667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Zhang XY, Qin Q, Tian L, Zhong GY, Zhang SW. Correlation between ecological factors and quality of Polygonatum cyrtonema hua from different producing areas. Mod Chin Med. 2022;7:1323–30. [Google Scholar]

14. Chen C, Wang B, Li JJ, Xiong F, Zhou G. Multivariate statistical analysis of metabolites in Anisodus tanguticus (Maxim.) Pascher to determine geographical origins and network pharmacology. Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:927336. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

15. Jiang YB, Gou Y, Yuan MH, Ma YY, Zhou J, Wu PE. HPLC fingerprint of Anisodus tanguticus root. J Chin Med Mat. 2015;38:957–61. [Google Scholar]

16. Tian L, Yin S, Ma YG, Kang H, Zhang X, Tan H, et al. Impact factor assessment of the uptake and accumulation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons by plant leaves: Morphological characteristics have the greatest impact. Sci Tot Env. 2019;652:1149–55. [Google Scholar]

17. Xu WQ, Cheng YL, Guo YH, Yao WR, Qian H. Effects of geographical location and environmental factors on metabolite content and immune activity of Echinacea purpurea in China based on metabolomics analysis. Indu Crops Pro. 2022;189:115782. [Google Scholar]

18. Wu F, Shi SL, Kang WJ, Chen XM, Zhang HH, Li ZL. Effects of thrips feeding on secondary metabolites and defense enzymes of alfalfa cultivars. Grass Turf. 2022;6:21–7. [Google Scholar]

19. Zhang Y, Zhu M, Lv HP. Comparative analysis of quality components in baked green tea made from tea plants grown at different altitudes. Food Sci. 2022;43:2257–68. [Google Scholar]

20. Bai Y, Wang YZ, Jing DC. Analysis on the correlation between the quality of Epimedium koreanum medicinal materials and soil factors from different origins. Lishizhen Medi Mater Medi Res. 2022;1:215–8. [Google Scholar]

21. He SL, Ma LF, Zhao KT. Survey analysis of soil physicochemical factors that influence the distribution of cordyceps in the Xiahe region of Gansu province. Open Life Sci. 2017;12:76–81. [Google Scholar]

22. Wen B, Li RY, Zhao X. A quadratic regression model to quantify plantation soil factors that affect tea quality. Agriculture. 2021;11:1225–32. doi:10.3390/agriculture11121225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Chen C, Shao Y, Li YL, Chen T. Elements in Lycium barbarum L. Leaves by inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry after microwave assisted digestion and multivariate analysis. Spectrosc Lett. 2015;48:775–80. doi:10.1080/00387010.2013.856324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Wang CS, Wang SP. A review of research on responses of leaf traits to climate change. Chin J Plant Eco. 2015;39:206–16. doi:10.17521/cjpe.2015.0020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Niinemets U, Portsmuth A, Tobias M. Leaf size modifies support biomass distribution among stems, petioles, and mid-ribs in temperate plants. New Phytol. 2006;171:91–104. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01741.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Sun SC, Jin DM, Shi PL. The leaf size-twig size spectrum of temperate woody species along an altitudinal gradient: an invariant allometric scaling relationship. Ann Bot. 2006;97:97–107. doi:10.1093/aob/mcj004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Levang-Brilz N, Biondini ME. Growth rate, root development and nutrient uptake of 55 plant species from the Great Plains Grasslands. USA Plant Ecol. 2002;165:117–44. doi:10.1023/A:1021469210691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Wang ZC, Chen MX, Yang YX, Fang X, Liu ZJ, Wang LY, et al. Effects of copper stress on plant growth and advances in the mechanisms of plant tolerance research. J Plant Nut Fer. 2021;10:1849–63. [Google Scholar]

29. Gong Q, Kang Q, Wang L, Li ZH. Toxicity mechanism of heavy metal copper to plants: a review. J Sou Agri. 2018;49:469–75. [Google Scholar]

30. Ni W, Huo CF, Wang P. Morphological plasticity of fine root traits in Larix plantations across a latitude gradient. Chin J Eco. 2014;9:2322–9. [Google Scholar]

31. Huang LQ, Guo LP. Secondary metabolites accumulating and geoherbs formation under enviromental stress. Chin J Chin Mater Med. 2001;32:227–80. [Google Scholar]

32. Frischknecht PM, Schuhmacher K, Muller-Scharer H. Phenotypic plasticity of senecio vulgaris from contrasting habitat types: growth and pyrrolizidine alkaloid formation. J Chem Ecol. 2001;27:343–58. doi:10.1023/A:1005684523068. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools