Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Effects of Different Fertilization Treatments on the Growth, Quality, and Microbial Community Structure of Grona styracifolia

1 School of Chinese Materia Medica, Guangdong Pharmaceutical University, Guangzhou, 510006, China

2 Guangdong Provincial Research Center on Good Agricultural Practice & Comprehensive Agricultural Development Engineering Technology of Cantonese Medicinal Materials, Guangzhou, 510006, China

3 Comprehensive Experimental Station of Guangzhou, Chinese Material Medica, China Agriculture Research System (CARS-21-16), Guangzhou, 510006, China

4 Key Laboratory of Production & Development of Cantonese Medicinal Materials, State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Guangzhou, 510006, China

* Corresponding Authors: Quan Yang. Email: ; Xiaomin Tang. Email:

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(3), 843-860. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.063062

Received 03 January 2025; Accepted 25 February 2025; Issue published 31 March 2025

Abstract

Fertilization is essential for high yield and quality in Chinese herbs. Grona styracifolia (Osbeck) H. Ohashi, a distinctive medicinal plant in the Lingnan region, currently encounters cultivation issues stemming from the overuse of chemical fertilizers. Adopting organic and microbial fertilizers presents a sustainable solution for its cultivation management. This study compared a no-fertilization control group with eight treatment groups using various concentrations of compound, organic, compound microbial, and Bacillus amyloliquefaciens fertilizers to evaluate their effects on G. styracifolia and soil microbial communities. The results demonstrated that the different fertilization treatments significantly enhanced plant growth and quality of G. styracifolia, while also increasing the activity of soil enzymes such as urease, invertase, and cellulase, as well as the levels of effective soil nutrients. Comprehensive affiliation function analysis demonstrated that applying Bacillus amyloliquefaciens fertilizer (15 g/kg) exhibited optimal performance in enhancing the growth of G. styracifolia and improving soil fertility parameters. Microbial sequencing of the soil indicated that under the application of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens fertilizer (15 g/kg), the relative abundance of Actinobacteria and Ascomycota increased significantly by 27.42% and 74.91%, respectively (p < 0.05). The application of microbial-based fertilizers significantly enriched the abundance of Mortierellomycota. Furthermore, LEfSe analysis identified distinct microbial biomarkers associated with different fertilizers. Additionally, redundancy analysis identified Invertase and available potassium (AK) as the primary drivers of soil bacterial and fungal community structures, respectively. This study demonstrated that the application of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens fertilizer (15 g/kg) significantly enhanced soil fertility and restructured microbial communities. These improvements led to increased yield and quality of G. styracifolia, providing a scientific foundation for sustainable cultivation.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Grona styracifolia (Osbeck) H. Ohashi & K. Ohashi, a member of the genus Grona (Leguminosae), is a authentic medicinal herb native to the Lingnan region. It contains bioactive compounds such as flavonoids, polysaccharides, and phenolics [1], and is clinically used to treat renal calculi. Schaftoside, the main active ingredient of G. styracifolia, is commonly used in kidney stones [2]. However, the rapid increase in market demand has made wild resources insufficient to meet the market’s needs, leading to cultivated medicinal materials becoming the primary source for commercial use. Fertilization serves as a primary approach in agricultural practices to enhance nutrient absorption and transformation in crops, thereby increasing yields and improving economic returns [3,4]. It also plays a pivotal role in promoting metabolite accumulation and elevating the quality of traditional Chinese medicinal materials [5,6]. Previous studies have demonstrated that nitrogen-phosphorus-potassium (NPK) fertilization enhances both the growth and quality of G. styracifolia [7]. Inorganic fertilizers serve as a crucial source of soil nutrients in commercial cultivation of G. styracifolia, providing short-term benefits such as increased crop yields through improved nutrient availability. However, prolonged over-application of inorganic fertilizers may lead to soil degradation, greenhouse gas emissions, and biodiversity loss, ultimately compromising the health and functioning of agroecosystems [8,9].

Organic fertilizer, rich in organic matter and essential plant nutrients, represents a potential alternative to inorganic fertilizers. It contains humic acid and other active substances that can promote the formation of soil aggregates and enhance both water conservation and fertilizer retention [10]. Lots of studies have consistently found that applying organic fertilizer significantly improves soil fertility, as well as important physical and chemical properties, ultimately leading to enhanced plant growth [11,12]. However, challenges remain regarding their high application rates and inconsistent efficacy. Microbial fertilizer, a eco-friendly functional fertilizer, contains beneficial microorganisms that can release phytohormones and enhance plant nutrient absorption [13]. Upon its application, microbial fertilizer aids in nitrogen fixation, phosphorus dissolution, and potassium release. Microbial fertilizer can not only promote the proliferation of beneficial bacteria [14], but also improve the utilization rate of soil nutrients [15]. In addition, applying microbial fertilizers can help fix nitrogen, dissolve phosphorus, and release potassium. Moreover, the application of microbial fertilizers can enhance the resistance of plants to soil pathogens. For example, after inoculation with Bacillus subtilis 50-1, the mortality rate associated with ginseng root rot decreased [16]. Bacillus amyloliquefaciens, a versatile endophytic plant bacterium, produces secondary metabolites that safeguard crops from pathogens, facilitate nutrient uptake, and enhance soil structure [17]. Therefore, the combined use of organic and biofertilizers offers an environmentally safe and sustainable approach for agricultural practices.

It is well-established that the rhizosphere soil of plants harbors a vast number of microorganisms. Soil microorganisms play a crucial role in various soil biochemical processes, including organic matter decomposition, nutrient transformation, and the breakdown of pollutants. They are essential components of agro-ecosystems and can act as sensitive indicators of changes in soil quality and health [18,19]. Several studies have shown that fertilization can directly impact soil properties, such as soil organic matter, pH, texture, and moisture, which in turn affects changes in soil microbial communities [20–22]. Soil enzymes, which originate from soil microorganisms, plant roots, and the decomposition of plant and animal residues, are diverse and play a vital role in organic matter decomposition and nutrient cycling [23]. Soil microorganisms and soil enzymes can be used as biological indicators for assessing soil health, and they are interconnected through symbiotic relationships. When microbial activity is altered by external factors, soil enzyme activity will also be affected [24]. However, previous studies on fertilization in G. styracifolia have primarily focused on the effects of fertilizers on the plant itself. Research on how different fertilizers influence the yield and quality of G. styracifolia by affecting rhizosphere soil nutrients and microbial community structure remains scarce. To achieve sustainable production of high-yield and high-quality G. styracifolia while protecting soil structure, this study designed a pot experiment using G. styracifolia as the experimental material. The aims of this study were (1) to evaluate the effects of different fertilization types on the growth of G. styracifolia and soil quality; (2) to determine the response of soil microorganisms to different fertilization types; and (3) to reveal the effects of soil properties and microorganisms on the yield and quality of G. styracifolia.

The study site was situated at Guangdong Pharmaceutical University, Panyu District, Guangzhou City, Guangdong Province, China (longitude 108°27′06″ E, latitude 30°45′26″ N). The GSO was obtained from the planting base of Nanling Pharmaceutical in Yunfu City, Guangdong Province, China (latitude 22°45′0.036″ N, longitude 111°45′24.516″ E). Sowing was conducted in April, and when the plants grew to a height of 15 cm, uniformly growing GSO seedlings were transplanted to the campus of Guangdong Pharmaceutical University. Fertilization treatments were applied on the 10th and 20th days after transplantation, with the fertilizer concentrations based on previous studies conducted by the research group and the research by Zhang et al. [25]. During application, shallow trenches were dug 5 cm away from the base of the stems, and the fertilizer was evenly distributed in the trenches before covering with soil. The experiment included a control group without fertilization, with a total of 9 treatments designed. Each treatment was replicated in 5 pots, with one GSO plant per pot. During the fertilization period, regular watering was carried out to maintain soil moisture. The experimental treatments, with abbreviations, are shown in Table 1 below. The soil used in the experiment was a 3:1:1 (v:v:v) garden soil:nutrient soil:vermiculite mixture. The garden soil was obtained from the medical plant nursery of the College of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Guangdong Pharmaceutical University, Guangdong, China. The pH of the mixed soil was 5.14, with available nitrogen at 54.28 mg·kg−1, available potassium at 43.75 mg·kg−1, and available phosphorus at 33.69 mg·kg−1.

The rapid growth period of GSO occurred from August to September, and the bud stage was reached in October. Agronomic traits, such as plant height, basal stem diameter, number of branches, fresh weight, and fresh weight, were measured by ruler, vernier calipers, and spring dynamometer. Each treatment included five plants. The aboveground parts of the plants were harvested, washed, and dried in an oven at 60°C until they reached a constant weight; then, the dry biomass was measured and recorded as the dry weight.

2.2.2 Determination of Flavonoid Content

The content of flavonoids (vicenin-1, schaftoside, isoschaftoside, and isovitexin) in GSO was determined by high-performance liquid chromatography. The stems and leaves of GSO was dried and ground into fine powder (passed through 50 mesh). A subsample of 0.2000 g of the resulting powder was measured. After adding 5 mL of 80% methanol and allowing it to stand for 12 h, the powder was then subjected to ultrasonic extraction for 30 min. An Agela C18 column (4.6 nm × 250 mm, 5.0 μm; 150 A) was used for analysis.

Soil was collected from the rhizosphere (0–20 cm depth) of GSO plants, gently shaken off the roots, sealed in a ziplock bag, placed on ice, and immediately transported to the laboratory. Upon arrival, the soil samples were divided into two portions. One portion promptly stored in a −80°C refrigerator for subsequent sequencing-based soil microbial diversity analysis, while another portion was naturally dried for soil nutrient and soil enzyme testing.

2.2.4 Determination of Soil Physical and Chemical Properties

Soil pH was determined using the potentiometric method, soil alkaline nitrogen (AN) was determined using the alkali-hydrolysis diffusion method, and soil available phosphorus (AP) was determined by the sodium bicarbonate extraction–molybdenum antimony anti-spectrophotometry method. Soil available potassium (AK) content was determined by the sodium tetraphenylborate colorimetric method, the total nitrogen (TN) content in the soil was determined using the Kjeldahl method [26].

2.2.5 Measurement of Soil Enzyme Activities

The phenol-sodium hypochlorite colorimetric method was using to determine Soil urease activity, and soil Invertase activity and soil cellulase activity were both determined by the 3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid colorimetric method [27].

2.2.6 Soil Microbial Community Structure

The rhizosphere soil samples stored at −80°C were sent to Hangzhou Lianchuan Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Hangzhou, China) for amplicon sequencing.

The data were organized using Microsoft Excel 2019 software and plotted with GraphPad Prism 8.0.2. Affiliation function analysis were conducted using SPSS 25.0. In order to determine the optimal fertilization rate, the membership function analysis is used to rank. Additionally, the microbial data was analyzed and visualized using the cloud platform provided by Hangzhou Lianchuan Biotechnology Co., Ltd. RDA analysis was used to explore the relationship between microbial abundance and environment. Partial Least Squares Path Modeling (PLSPM) was performed using the plspm package (version 4.4.2) in R. In the LEfSe analysis, the treatment groups were analyzed based on different types of fertilizers. Except for the LEfSe analysis, all other analyses were conducted separately for each treatment.

3.1 Effect of Different Fertilization Treatments on Agronomic Traits of GSO

The impact on the growth of GSO was as follows (Table 2). The growth and development rate of GSO was significantly improved after fertilization. The degree of growth varied depending on the type and concentration of the fertilization. Compared with CK, there was no significant difference in the basal ground diameter, and number of branches of GSO among each fertilization treatment. The longest plant length of GSO under T7 treatment increased by 65.03% (p < 0.001) compared to the control plant length. The fresh weight and dry weight of GSO were significantly enhanced under fertilizer treatments (T2–T8). The T8 treatment showed the most pronounced effects, increasing fresh weight and dry weight by 560.63% and 309.10%, respectively, compared to the control (CK) (p < 0.001). Other treatments (T2–T7) resulted in incremental increases of 35.42%–459.14% for fresh weight and 11.09%–244.16% for dry weight. Overall, fertilizer concentration was positively correlated with growth promotion effects.

3.2 Effects of Different Fertilization Treatments on Flavonoid Content of GSO

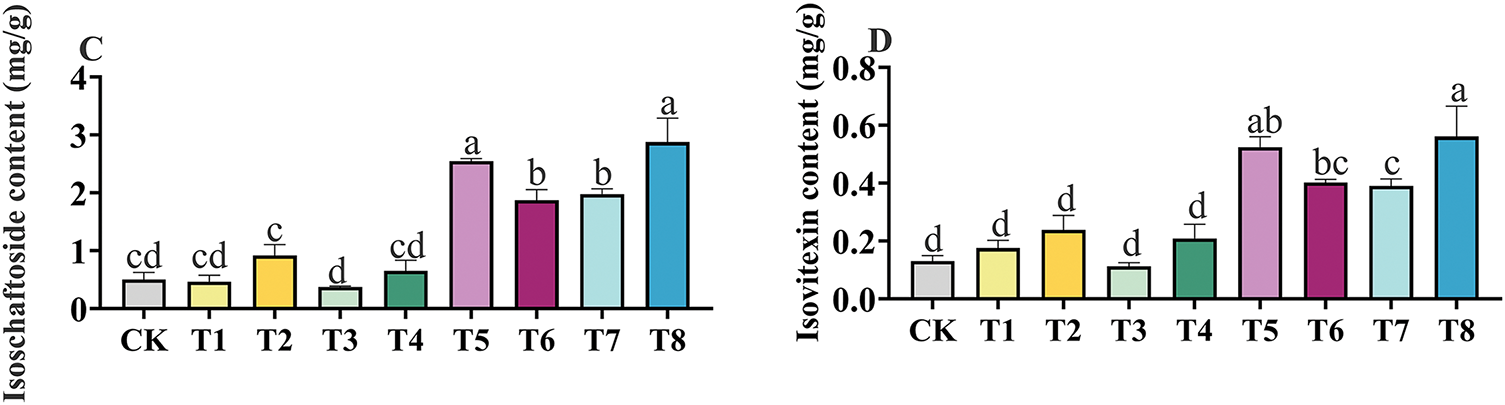

In Fig. 1, the effects of different fertilization treatments on the flavonoid content of GSO are represented by labels A to D. The trends in the contents of vicenin-1, schaftoside, isoschaftoside and isovitexin were consistent within the same fertilization treatment. The contents of active components in the compound fertilizer treatment group, organic fertilizer treatment group, and Bacillus amyloliquefaciens treatment group all exhibited an increasing trend as the fertilizer concentration increased. Among them, the application of microbial-based fertilizers (T5–T8) greatly increased the content of active ingredients in GSO. The T8 treatment was associated with the highest contents of vicenin-1, schaftoside, isoschaftoside, and isovitexin, with significant increases of 340.59% (p < 0.001), 354.76% (p < 0.001), 356.19% (p < 0.001), and 331.54% (p < 0.001), respectively, higher than those under CK conditions.

Figure 1: The effects of different fertilizer treatments on the content of Vicenin-1 (A), schaftoside (B), isoschaftoside (C) and isovitexin (D) in Grona styracifolia (GSO). Different letters indicate significant differences at 0.05 level (p < 0.05)

3.3 Effects of Different Fertilization Treatments on Soil Physicochemical Properties of GSO

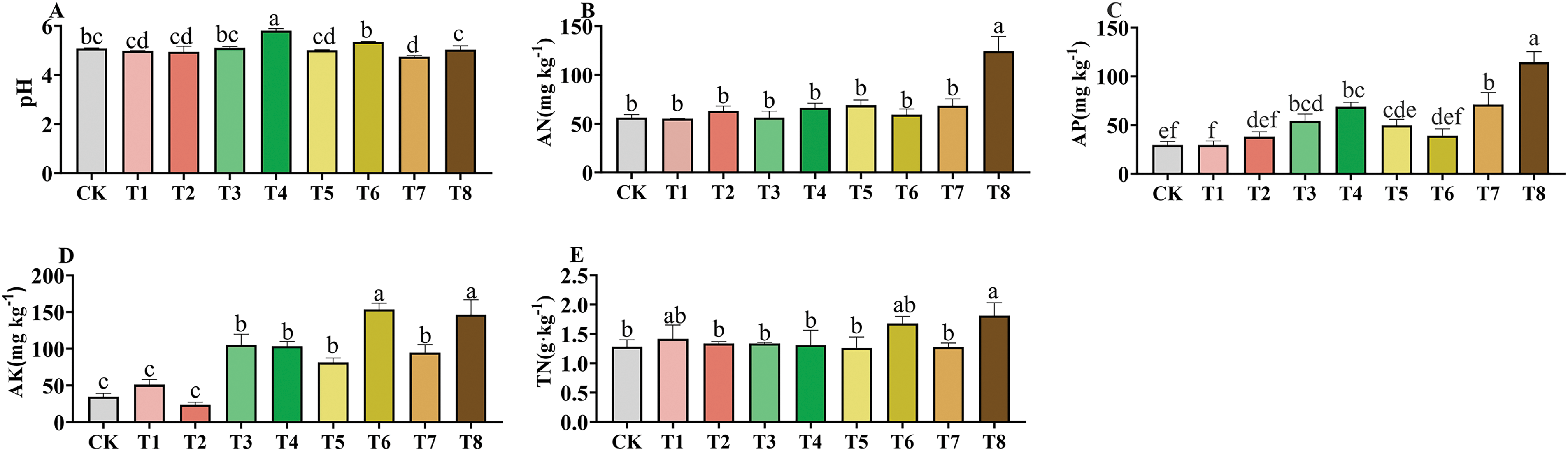

As shown in Fig. 2, soil pH increased under the T4 treatment. The T8 treatment significantly increased soil AN content and TN, which increased by 38.52% (p < 0.05) and 120.38% (p < 0.001) respectively higher than that under CK conditions. In terms of AP, the content of soil available phosphorus exhibited a descending order among the treatments: T8 > T7 > T4 > T3 > T5 > T6 > T2 > T1 > CK. The highest available phosphorus content was observed in the T8 treatment, showing a 2.87-fold increase compared to CK (p < 0.001). All fertilization treatments except T2 treatment increased the content of soil available potassium. The results of the study showed that fertilizer application greatly increased the soil quick-acting nutrient content and promoted nutrient uptake by plants.

Figure 2: Effects of different fertilizer treatments on soil pH (A), alkali-hydrolyzable nitrogen (B), available phosphorus (C), available potassium (D) and total nitrogen (E). Different letters indicate significant differences at 0.05 level (p < 0.05)

3.4 Effects of Different Fertilization Treatments on Soil Enzyme Activities of GSO

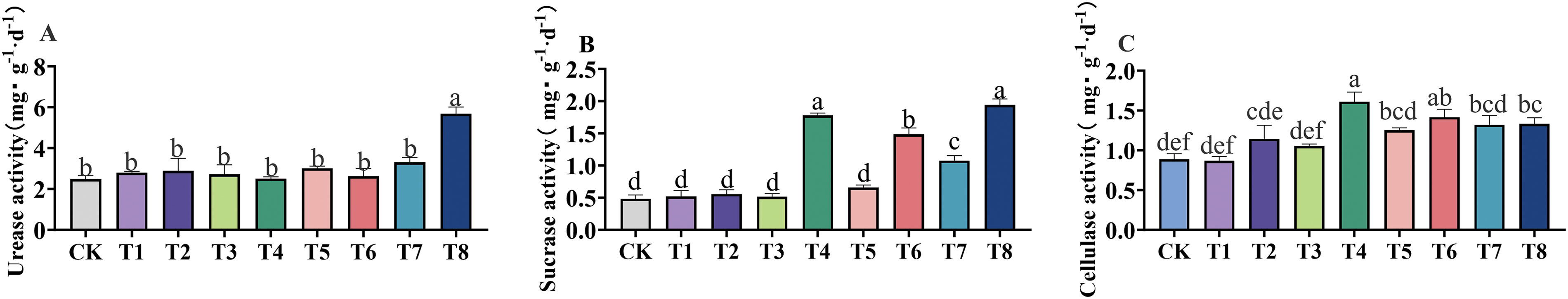

The soil enzyme activities of GSO under different fertilization treatments are presented in Fig. 3. Compared with CK conditions, soil urease activity was highest under the T8 treatment, which increased by 128.12% (p < 0.001). An increase in fertilizer concentration led to an increase in soil Invertase activity. This was supported by significantly higher soil Invertase activity under the T4, T6, and T8 treatments (p < 0.001). Cellulase activity showed T4 > T6 > T7 > T8 > T5 > T2 > T3 > CK > T1. The cellulase activity under T4 treatment was the highest, with a significant increase of 82.95% (p < 0.001) compared to CK conditions, and cellulase activity under T5, T6, T7, and T8 treatments exhibited significant increases of 42.05%, 60.23% (p < 0.001), 60.00% (p < 0.001), 50.00% (p < 0.01), and 51.14% (p < 0.01), respectively. The results indicate that the application of microbial-based fertilizers promotes the degradation of cellulose to glucose in the soil, thus providing more available carbon sources for plants.

Figure 3: Effects of different fertilizer treatments on the activities of urease (A), invertase (B) and cellulase (C) in soil. Different letters indicate significant differences at 0.05 level (p < 0.05)

3.5 Correlation Analysis of Various Indices under Different Fertilization Treatments for GSO

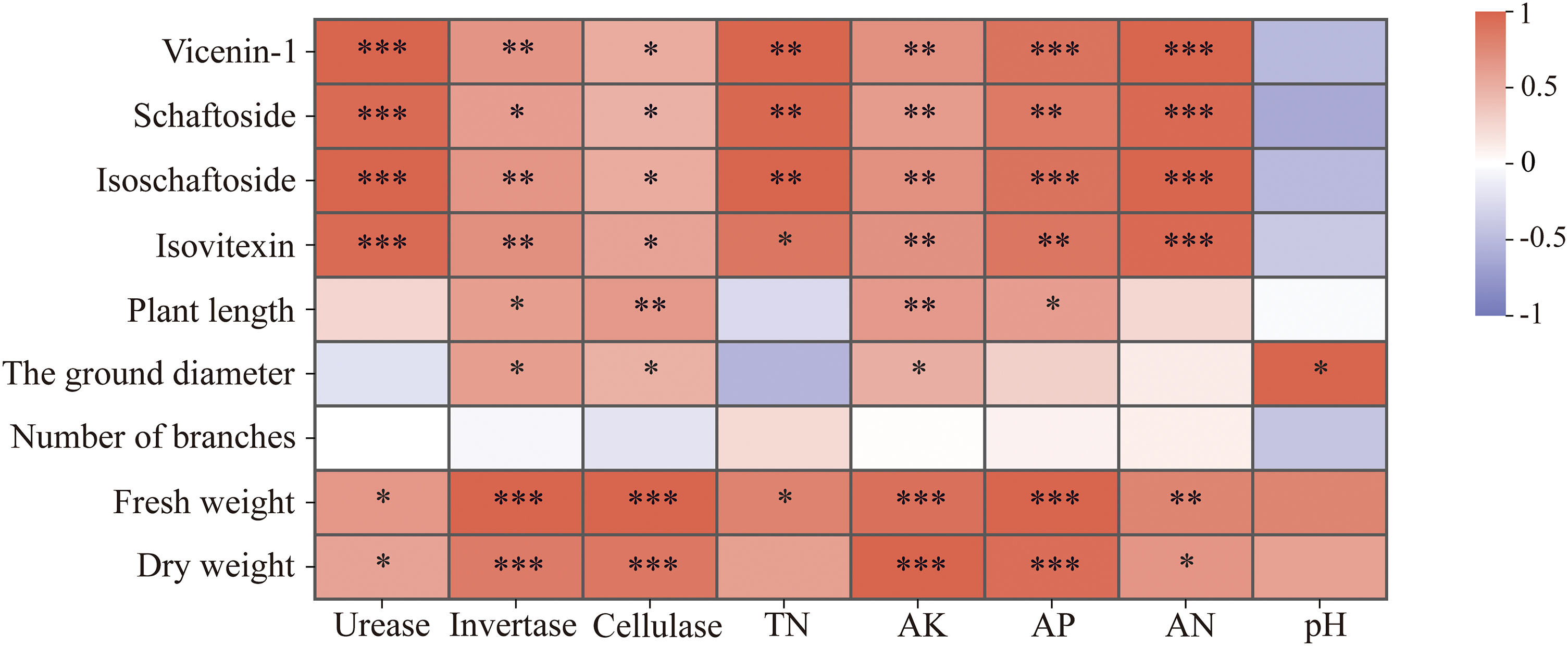

To further investigate the relationship between the phenotype and active components of GSO and soil, the agronomic traits, active components, soil physical and chemical properties and soil enzymes were analyzed by Pearson correlation analysis (Fig. 4). This analysis revealed that both the growth and the concentration of active ingredients in GSO were closely linked to soil properties. Notably, Invertase, cellulase, AK, and AN demonstrated a highly significant positive correlation with yield (p < 0.001). Furthermore, urease and AN contributed to the accumulation of active ingredients (p < 0.001). An increase in pH was also associated with an increase in the ground diameter of GSO (p < 0.05).

Figure 4: Correlation analysis between agronomic traits, active ingredients and soil enzymes and soil physicochemical properties of Grona styracifolia (GSO) under different fertilization treatments (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001)

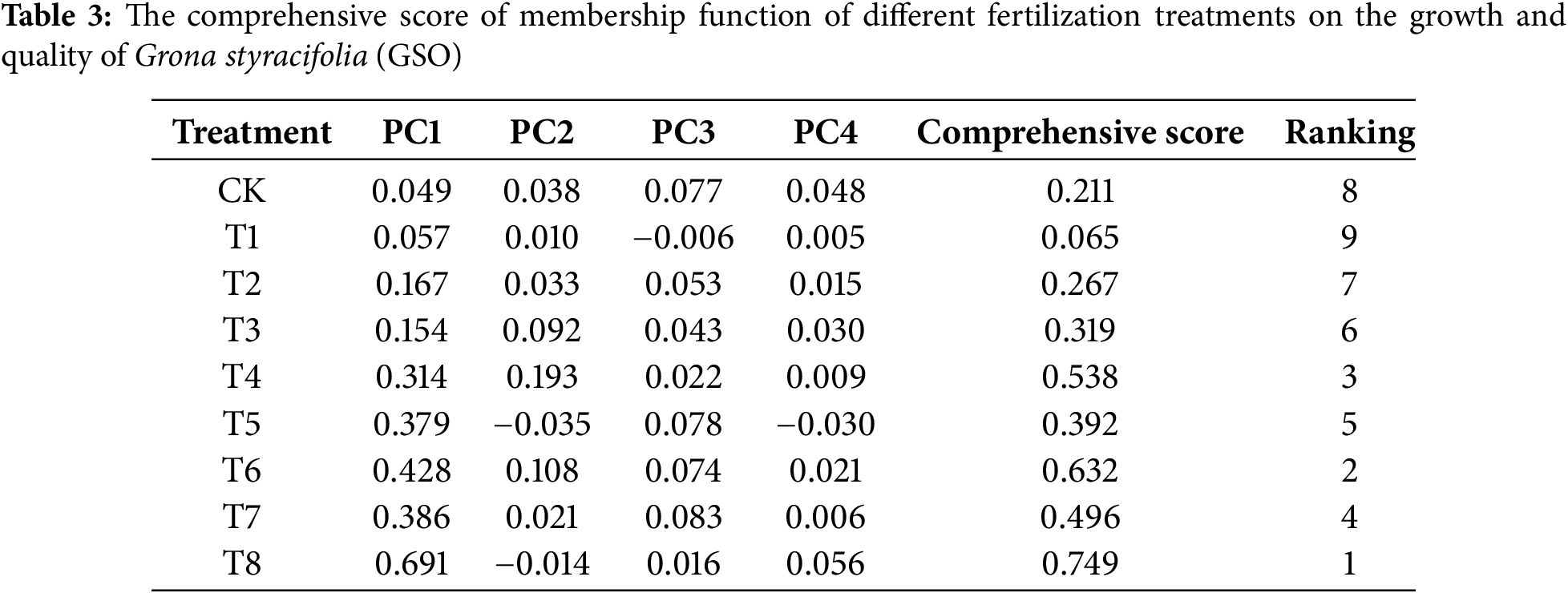

3.6 Comprehensive Evaluation of the Affiliation Function of Different Fertilization Treatments on the Growth and Quality of GSO

To effectively identify the most suitable fertilization method, we analyzed 17 indicators for agronomic traits, active ingredients, soil enzymes, and soil physical and chemical properties as affiliation functions. The comprehensive evaluation (Table 3) revealed that the scores of all fertilization treatments except T1 (compound fertilizer, 5 g/kg) were higher than that of CK conditions. The D values of all treatments were ranked as follows in descending order: T8, T6, T4, T7, T5, T3, T2, CK, T1. Notably, T8 (Bacillus amyloliquefaciens fertilizer, 5 g/kg) treatment obtained the highest score (0.749), significantly surpassing the score under CK conditions without fertilizer (0.211), indicating that it is optimal for promoting both GSO growth and soil fertility.

3.7 Effects of Different Fertilization Treatments on Microbial Communities of GSO

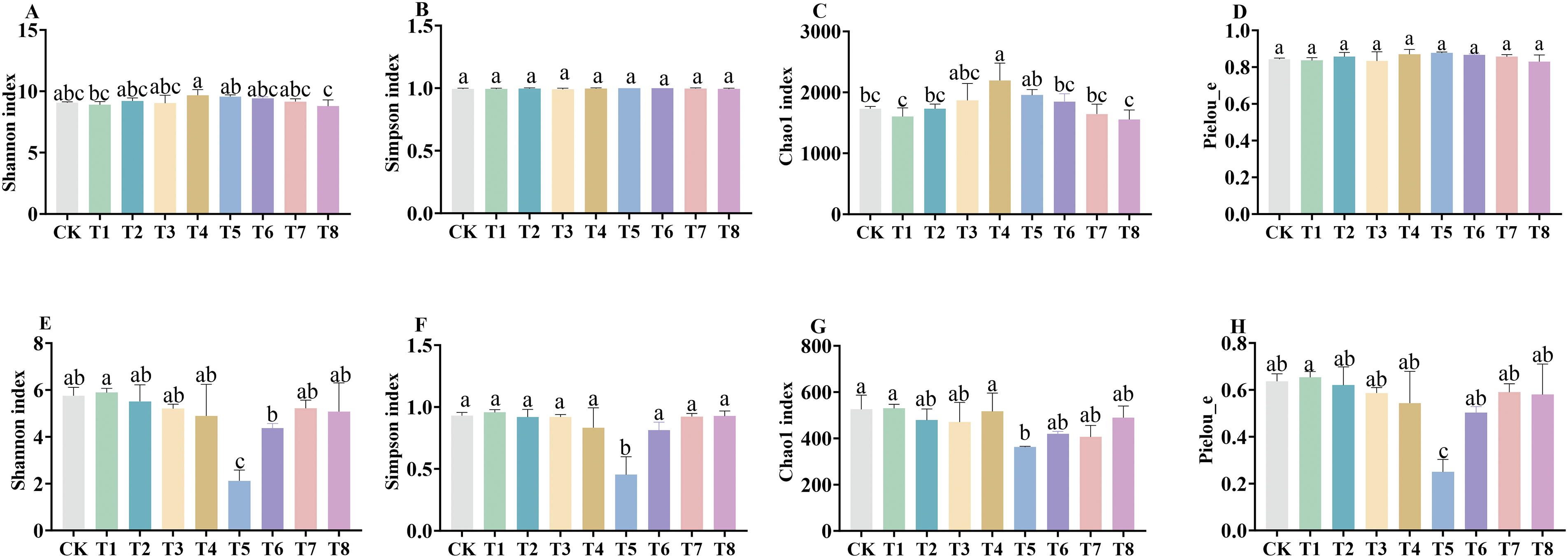

3.7.1 Alpha Diversity Analysis of Soil Microbial Communities

As shown in Fig. 5, indicating that the soil bacteria richness was significantly increased by 26.71% (p < 0.05) under the T4 treatment compared with CK conditions. There was no significant difference between either Simpson’s index or the Shannon index of soil bacteria in each fertilization treatment. Meanwhile, Simpson’s index and the Shannon index of soil fungi under T5 treatment showed a significant decreasing trend compared with CK conditions. The Pielou_e index measures species evenness, and as the fertilizer concentration increased, the Shannon index, Simpson’s index, the Chao1 value and the Pielou_e index of soil fungi under compound biofertilizer treatment showed a significant decreasing trend compared with CK conditions; the Pielou_e index consistently showed an increasing trend, and the fungal richness increased.

Figure 5: Comparison of soil bacterial and fungal diversity under different fertilization treatments. (A–D) represented Shannon index of bacterial community, Simpson index represented Shannon index, Simpson index, Chao1 value and Pielou_e index of bacterial community, respectively. (E–H) represented Shannon index, Simpson index, Chao1 value and Pielou_e index of fungal community, respectively. Different letters indicate significant differences at 0.05 level (p < 0.05)

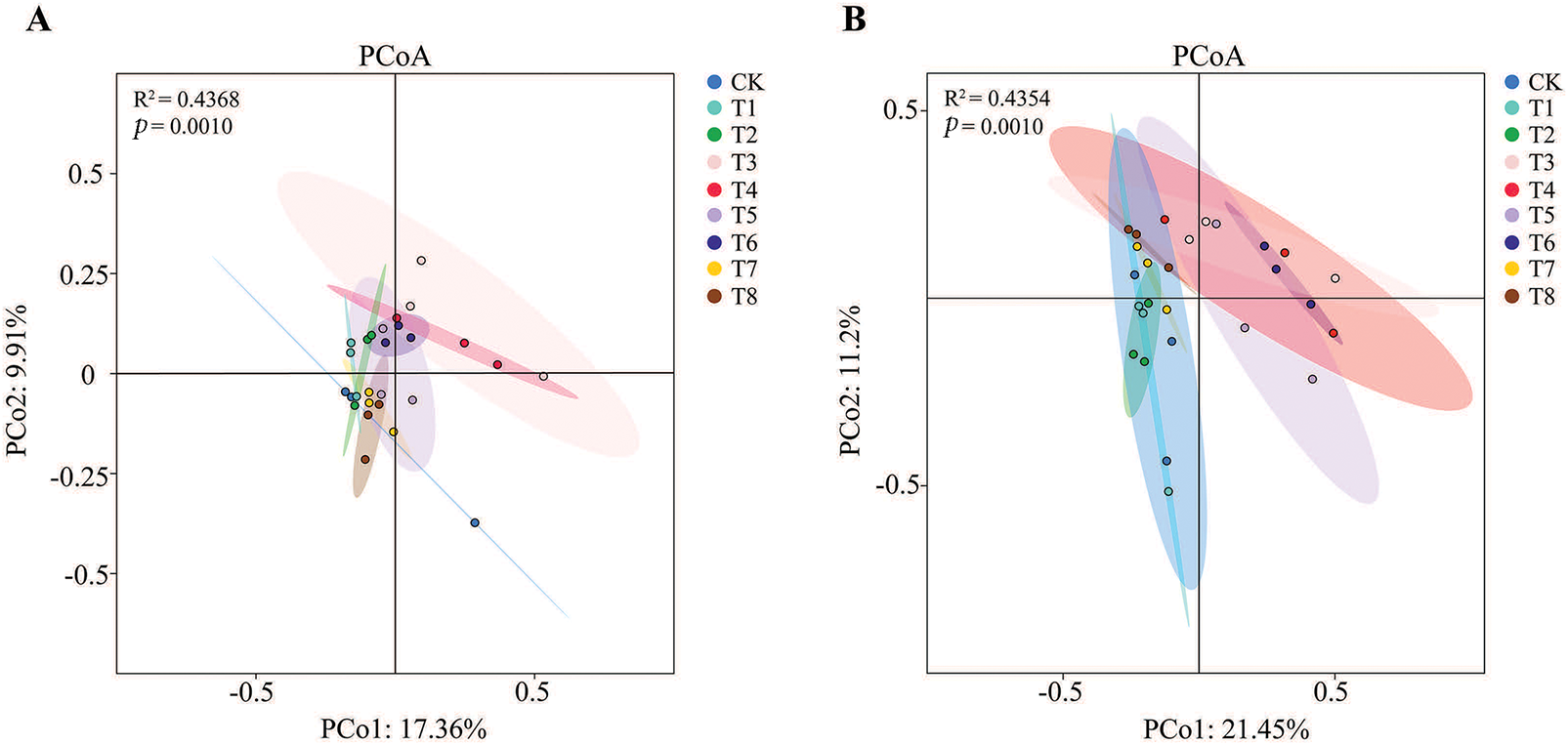

3.7.2 Beta Diversity Analysis of Soil Microbial Communities

PCoA analysis explained 27.27% and 32.81% of the total variation in bacterial and fungal communities across the nine treatments. As shown in Fig. 6A, the groups T3, T4, and T6 were distinctly separated from the CK group, indicating significant differences in the soil bacterial community structure under these three fertilizer treatments compared to the no-fertilization treatment. In Fig. 6B, the groups T6 was significantly separated from the CK group, suggesting substantial differences in the soil fungal community structure compared to the no-fertilization treatment. Furthermore, as shown in both Fig. 6A,B, the proximity or overlap of different fertilizer treatment groups indicates minor differences in the soil bacterial and fungal communities between these treatments. Notably, under the compound biofertilizer treatment, the low concentration treatment (T5) showed overlap with the CK treatment, whereas the high concentration treatment (T6) was completely separated from the CK treatment in Fig. 6A. This suggests that not only the type of fertilizer application, but also the concentration of application, impacts the soil microbial structure.

Figure 6: Analysis of β diversity of bacteria (A) and fungi (B) in rhizosphere soil of Grona styracifolia (GSO) under different fertilization treatments

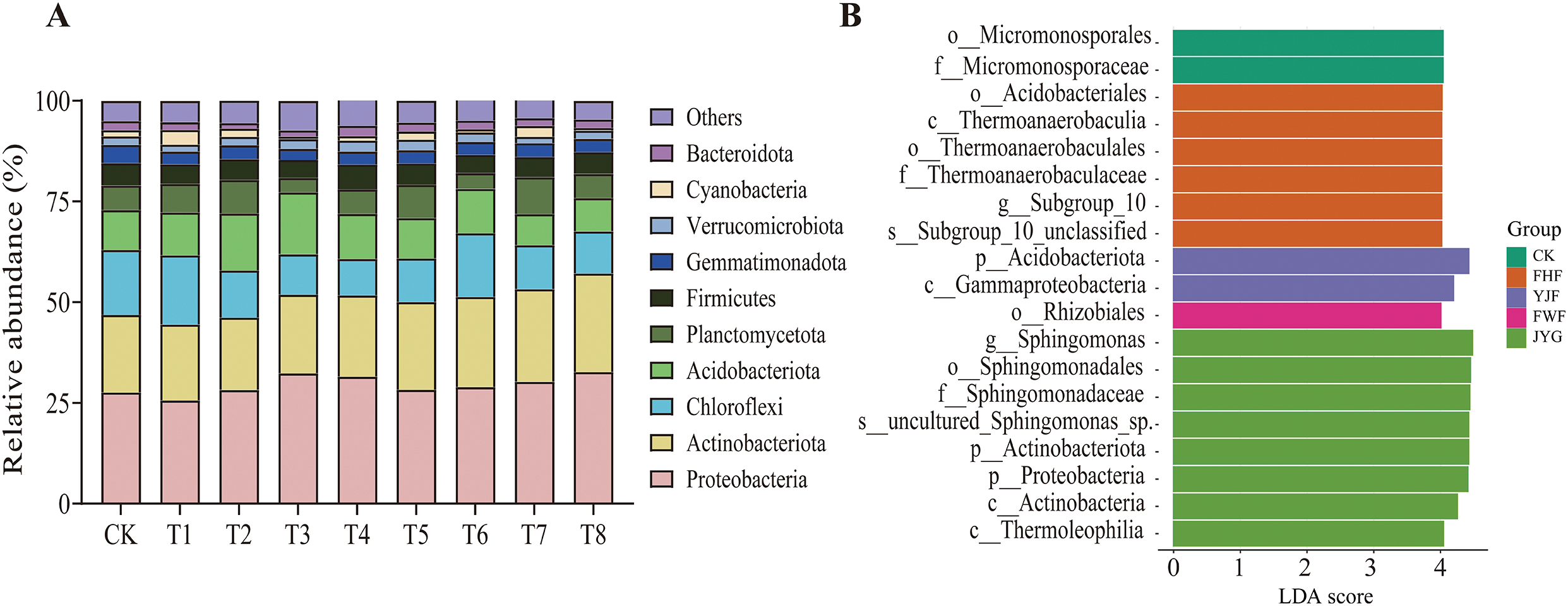

3.7.3 Bacterial Community Composition at the Phylum Level

In the analysis presented in Fig. 7, the top ten bacterial phyla in soil samples from various fertilization treatments comprised 93.43% to 95.53% of the total abundance. The T8 treatment group showed a 27.42% increase in Actinobacteria compared to the control group (CK). In the case of Acidobacteria, both the T2 and T3 treatment groups exhibited substantial increases of 43.40% and 55.10% respectively, compared to the CK group. Furthermore, the abundance of Cyanobacteria increased significantly, by 1.32-fold, under the T1 treatment compared to the CK group. LEfSe analysis revealed significant differences in soil bacterial communities among fertilization treatments (p < 0.05, LDA > 4). A total of 2, 6, 2, 1, and 8 biomarkers were identified in the CK, FHF, YJF, and FWF groups, respectively (Fig. 7B). Micromonosporales were the biomarkers at the order level in CK, while Rhizobiales were the only biomarkers in FWF. The JYG group showed the highest number of biomarkers, including 2 phyla, 2 orders, 1 family, 1 genus, and 1 species.

Figure 7: Changes in bacterial community composition. (A) is the relative abundance of bacteria at the level of Grona styracifolia (GSO) under different treatments. (B) was LEfSe bar (LDA score = 4, p < 0.05)

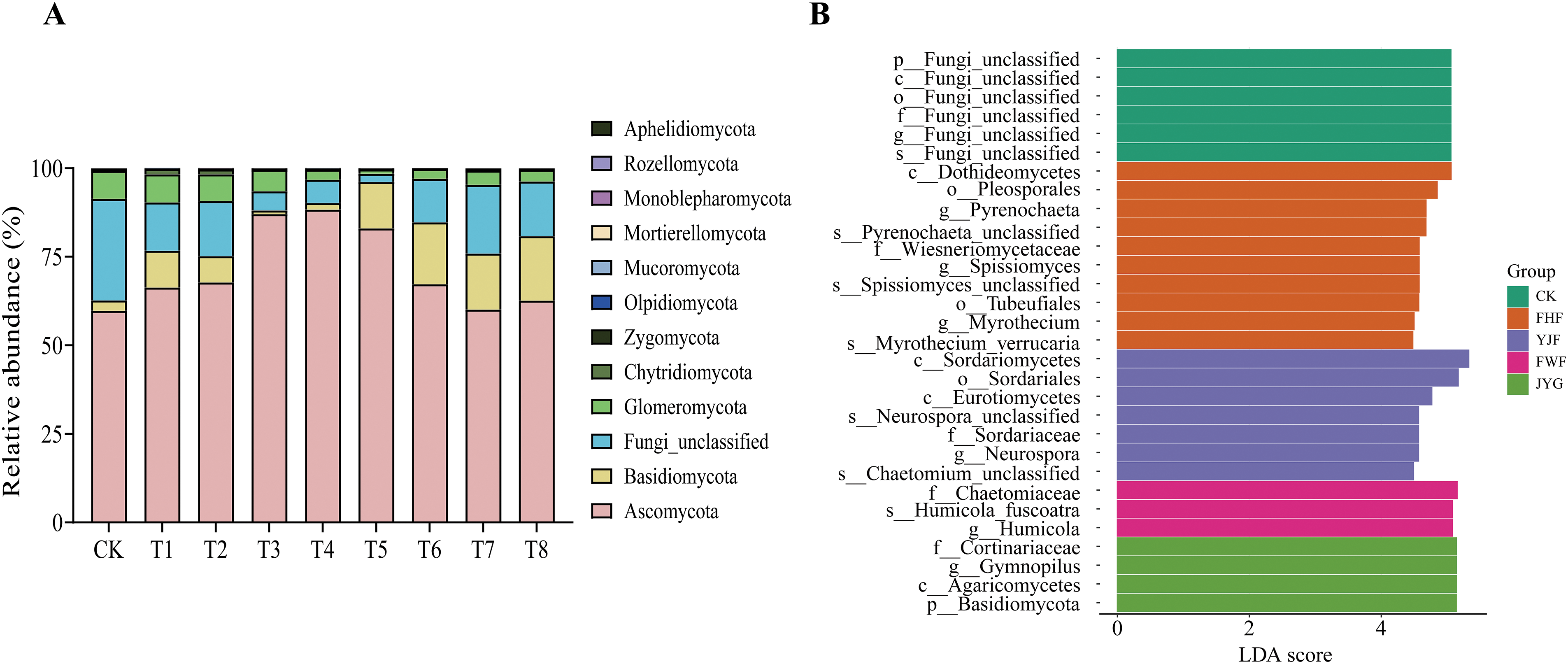

3.7.4 Fungal Community Composition at the Phylum Level

As shown in Fig. 8, a total of 12 phyla of inter-root soil microbial fungi were present across all samples. For the Ascomycota phylum, the relative abundance in T3, T4, and T5 treatments increased significantly by 73.37%, 74.91%, and 64.45%, respectively, compared to CK. Conversely, the relative abundance of unnamed fungi decreased in all treatment groups after fertilizer application. In the Zygomycota phylum, the relative abundance under T8 treatment increased significantly by 1.46-fold compared to CK. LEfSe analysis identified Fungi unclassified as the biomarker for CK. The FHF treatment had the most biomarkers, including one phylum, two classes, one family, three genera, and three species. In the YJF treatment group, the biomarkers included Sordariomycetes, Eurotiomycetes, Neurospora, and Chaetomiaceae, with Sordariomycetes having the greatest effect at the level of the order.

Figure 8: Changes in fungal community composition. (A) is the relative abundance of fungi at the level of Grona styracifolia (GSO) under different treatments. (B) was LEfSe bar (LDA score = 4, p < 0.05)

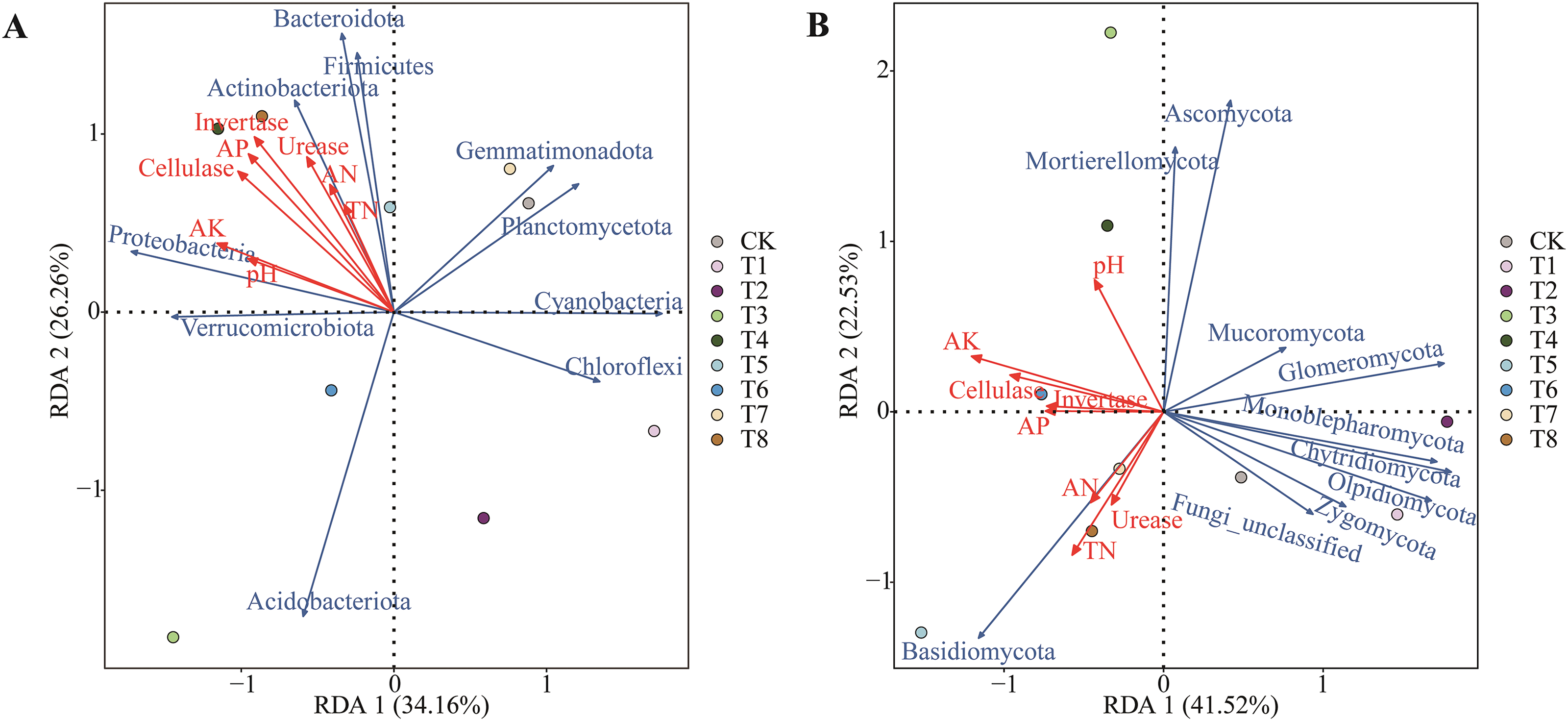

3.7.5 Redundancy Analysis of Soil Physicochemical Properties and Soil Enzymes on Microbial Communities

The results from the Redundancy Analysis (RDA), as illustrated in Fig. 9A, indicate that the first and second principal components explained 34.16% and 26.26% of the variance in bacterial communities, respectively, while in fungal communities, these components accounted for 41.52% and 22.53% of the variance (Fig. 9B). At the phylum level, Invertase activity and AP emerged as significant determinants of bacterial abundance. Positive correlations were observed for the phyla Verrucomicrobiota, Proteobacteria, Actinobacteriota, Bacteroidota, and Firmicutes concerning soil enzyme activities and various soil physicochemical properties. In contrast, other bacterial phyla exhibited negative correlations with these factors. Regarding the fungal microbial community, a synergistic interaction was noted between distinct soil physicochemical properties and soil enzyme activities. Specifically, AK emerged as a key factor influencing bacterial abundance, while Basidiomycota, Mortierellomycota, and Ascomycota exhibited positive correlations with alkaline phosphatase. Furthermore, Fungi_unclassified and Zygomycota were positively correlated with urease activity. Conversely, a negative correlation was observed between the remaining fungal phyla and both soil properties and enzyme activities. The organic fertilizer treatment displayed a significant separation from the unfertilized group, suggesting that this fertilization strategy significantly influences the structural dynamics of the soil fungal community.

Figure 9: RDA analysis of soil physical and chemical properties and soil enzyme and microbial community composition. (A, B) represented the soil physicochemical properties under different fertilization treatments and the redundancy analysis of soil enzymes on bacterial community and fungal community, respectively. In the figure, the blue arrow represents soil physical and chemical properties and soil enzymes, and the red arrow represents soil physical and chemical properties and soil enzymes

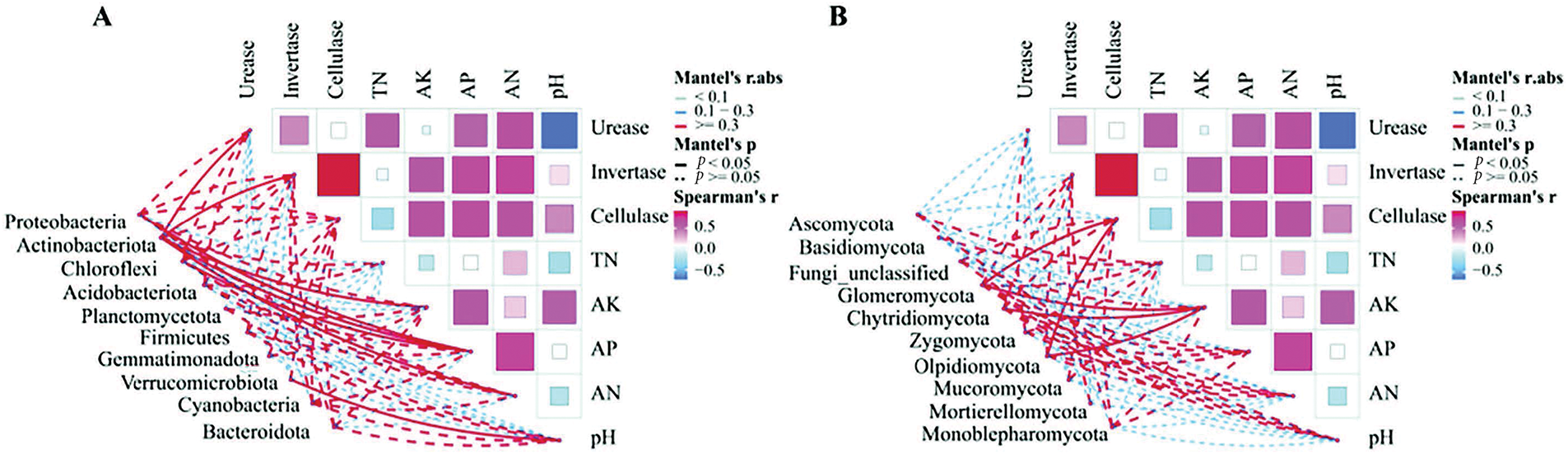

3.7.6 Correlation Analysis of Soil Physicochemical Properties and Soil Enzymes

Spearman correlation analysis of the 10 dominant bacterial phyla and 10 fungal phyla selected from soil microbial communities (Fig. 10) revealed positive correlations between urease, invertase, AK, AP, AN, and Actinobacteria abundance (p < 0.05). Additionally, pH was negatively correlated with Verrucomicrobiota abundance (p < 0.05). Proteobacteria and Actinobacteriota were positively correlated with AP (p < 0.05), while Chloroflexi was negatively correlated with AP (p < 0.05). As shown in Fig. 10B, soil properties and soil enzyme activities exhibited positive correlations with the abundances of most fungal phyla, while the correlation is not significant. Furthermore, cellulase level and AK level was negatively correlated (p < 0.05) with the abundance of the Glomeromycota and Olpidiomycota, and AK level was also negatively correlated (p < 0.05) with the abundance of the Chytridiomycota.

Figure 10: Correlation analysis of soil physical and chemical properties, soil enzymes and soil microbial community structure under different fertilization treatments. (A) 10 dominant bacterial phyla; (B) 10 fungal phyla

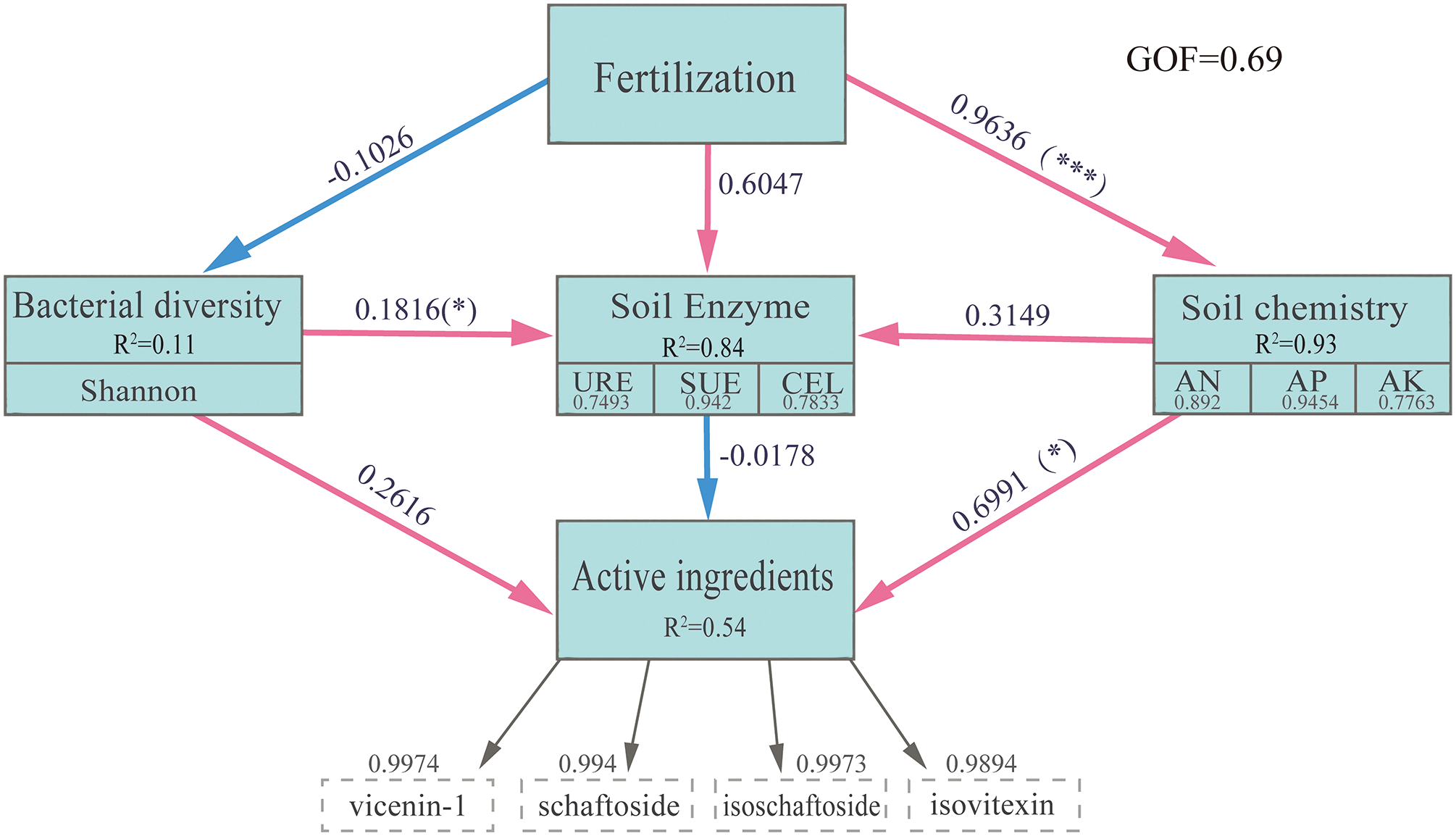

3.7.7 Effect of Fertilization Treatments, Soil Fertility and Bacterial Diversity on Active Ingredients

The findings from the PLS-PM analysis indicated that fertilization treatment positively influenced both soil chemical properties (0.9636***) and soil enzymes (0.6047), while having a negative impact on bacterial diversity (Fig. 11). Notably, bacterial diversity (0.1816*) and soil chemical properties (0.3149) contributed to enhancing soil enzyme activity and played a significant role in promoting the accumulation of active ingredients in GSO. Among these factors, soil chemical properties had a marked positive effect on the active ingredients, whereas soil enzymes exhibited a negative influence.

Figure 11: The PLS-PM model examined the impact of various fertilization treatments on soil enzyme activity, soil chemical properties, and microbial diversity, as well as their influence on the accumulation of chemical components in GSO. The red arrow denotes a positive relationship, while the blue arrow indicates a negative relationship; the values on the arrows represent the path coefficients. Path coefficients are calculated after 1000 bootstrap sessions. Gray numbers indicate the loading scores of the observed variables that created the latent variables. R2 values indicate the proportion of Explained Variance for each variable. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001. The model’s performance was assessed using the Goodness of Fit (GOF), which was found to be 0.69

4.1 Effects of Different Fertilization Treatments on Growth and Quality of GSO

Fertilizers contain various nutrients that promote the growth of plants. This study revealed that the application of different types of fertilizers led to varying degrees of promotion of plant length, fresh weight, and dry weight in GSO. Similar effects have been observed in other medicinal plants [28–31]. Soil nutrient content increased significantly after fertilizer application. Correlation analysis (Fig. 4) indicates that AK, AP, and cellulase activity had a highly significant effect on the yield of GSO (p < 0.001). Cellulase can accelerate the decomposition of cellulose and enhance the availability of carbon nutrients in the soil. Previous studies have indicated that phosphorus promotes the photosynthesis and respiration of potato plants, indirectly affecting their growth, development, and yield [32]. Additionally, potassium can enhance plant growth rates and increase yields [33,34]. Under the same fertilizer, increasing the concentration of applied fertilizer favors the yield of GSO, consistent with previous reports [35]. Flavonoid composition is a crucial indicator of GSO quality. There was a significant increase (p < 0.001) in the content of flavonoid components of GSO after application of microbial fertilizers, including compound microbial fertilizer and Bacillus amyloliquefaciens fertilizer, which indicated that microbial fertilizers promoted the accumulation of secondary metabolites of GSO. Wei et al. [36] discovered that the combined application of microalgae and Bacillus can promote the accumulation of cryptotanshinone, tanshinone IIA, total tanshinones, and salvianolic acid B. Additionally, the biomass of both the aerial and underground parts of the plants was significantly increased. In particular, the promoting effect of high-concentration Bacillus amyloliquefaciens fertilizer was particularly prominent. Schaftoside, the active ingredient in GSO as noted in the Chinese Pharmacopoeia, exhibited a significant 354.76% (p < 0.001) increase (Fig. 1). In the PLS-PM analysis (Fig. 11), soil properties significantly promoted the accumulation of active ingredients in GSO (p < 0.05). Correlation analysis (Fig. 4) revealed that AK was highly significantly correlated with all four flavonoid components (p < 0.001). The application of microbial-based fertilizers increased soil nutrient contents to varying degrees. Previous studies have demonstrated that increases in AN, AP, and AK contents facilitate the synthesis of flavonoid compounds [37]. The initial substrates for the biosynthesis and metabolism of flavonoid compounds in plants are photosynthetic products, and enhanced photosynthesis is beneficial for the accumulation of active ingredients in GSO. Numerous studies have confirmed that N, P, and K are essential nutrients for photosynthesis [38–40]. Additionally, N content is associated with phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL) activity [41]. The deamination of phenylalanine, catalyzed by PAL to produce trans-cinnamic acid, is the first and key step in the shikimate pathway for flavonoid biosynthesis. Enhanced PAL activity strengthens the deamination of phenylalanine in the shikimate pathway, thereby improving metabolic efficiency. Bacillus amyloliquefaciens possesses nitrogen-fixing capabilities and significantly enhances plant nitrogen uptake [42]. In this study, the application of high-concentration Bacillus amyloliquefaciens fertilizer significantly increased soil AN, AP, and AK contents (p < 0.001), which subsequently improved the quality of GSO.

4.2 Effects of Different Fertilization Treatments on the Microbial Structure of the Soil

The rhizosphere soil microbial community responds to fertilization and plays a significant role in nutrient cycling and soil organic matter decomposition [43,44]. In this study, we evaluated the effects of eight fertilization treatments on the microbial community structure. The results show that Actinobacteria and Proteobacteria were the most abundant bacterial phyla in all fertilization treatments, both of which are commonly found in soil bacterial communities [45]. LEfSe analysis reveals that Acidobacteria were significantly enriched in the compound fertilizer treatment group, and their relative abundance increased with higher fertilization concentrations. Long-term application of chemical fertilizers may lead to soil acidification. Acidobacteria thrive in acidic environments because they are acidophilic [46]. In the RDA analysis, Acidobacteria showed negative correlations with soil nutrients and enzyme activities, which was further supported by Mantel test. As oligotrophic microorganisms, Acidobacteria typically adapt to low nutrient levels in soil [47]. It has been reported that Acidobacteria can effectively promote lignin decomposition in soil, and some species are even capable of photosynthesis, playing important roles in carbon and iron cycling [48]. Gammaproteobacteria, belonging to the γ-Proteobacteria class, were identified as a biomarker in the organic fertilizer treatment group. These microorganisms are generally adapted to carbon-rich environments. Therefore, this biomarker may reflect the increased carbon content in the rhizosphere soil under organic fertilizer treatment. In the determination of soil enzyme (Fig. 3), the activities of Invertase and cellulase significantly increased with higher fertilization concentrations in the organic fertilizer treatment (p < 0.001). The increase in available carbon substrates in the soil likely promoted the activities of these enzymes, confirming the earlier hypothesis. Actinobacteria can accelerate soil nutrient cycling and organic matter decomposition, while also producing various antibiotics to suppress pathogens [49]. The application of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens fertilizer significantly increased the relative abundance of Actinobacteria (p < 0.05). Sphingomonas was identified as a biomarker in the Bacillus amyloliquefaciens fertilizer treatment group. Studies have shown that Sphingomonas can fix nitrogen, solubilize phosphorus, and promote the production of indole-3-acetic acid (IAA). Therefore, the application of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens fertilizer can effectively enhance the growth of GSO, thereby improving yield. Our study indicates that Ascomycota is the most dominant phylum in the fungal community, consistent with previous studies [50]. The phylum Ascomycota encompasses the majority of saprophytic fungi, which are capable of effectively degrading organic matter in the soil and promoting the cycling and utilization of nutrients [51]. The introduction of organic fertilizer significantly boosted the prevalence of Ascomycota, aligning with previous research results [52]. This increase may be owing to the application of organic fertilizer added to the soil organic matter content, which prompted the flourishing of Ascomycota. Sordariomycetes can inhibit the growth of weeds and shrubs and are widely used in weed control studies [53]. LEfSe analysis revealed that Sordariomycetes is a biomarker for the organic fertilizer treatment group, and its enrichment may limit the growth of weeds that compete with Glechoma longituba for nutrients. Basidiomycota was identified as a biomarker for the Bacillus amyloliquefaciens fertilizer treatment group. Basidiomycota functions similarly to Ascomycota in decomposing organic matter. However, Basidiomycota is typically responsible for lignin decomposition. It is widely distributed in soil and can form symbiotic mycorrhizae with crops, thereby enhancing plant growth [54,55]. Additionally, Basidiomycota also participates in the decomposition of recalcitrant carbon and increases the content of soil organic carbon [56]. The increased activities of Invertase and cellulase under Bacillus amyloliquefaciens treatment confirm this point. Basidiomycota were negatively correlated with Ascomycetes in RDA analysis, and it was previously hypothesized that there might be a competitive relationship between these two phyla [57]. Our study found that Mortierellomycota was enriched in the microbial fertilizer treatment group and is considered a biomarker for healthy rhizosphere soil [58]. Microbial fertilizers enhance crop stress resistance by inducing the production of substances related to defense responses, such as antioxidant enzymes, chitinases, plant antibiotics, and phenolic compounds, thereby inhibiting the production of harmful bacteria [59].

The results of our study showed that different fertilization regimes had distinct effects on the growth and soil microbial structure of GSO. This study reveals that microbial-based fertilizers are an ideal fertilization strategy. The application of microbial-based fertilizers enhances soil fertility and provides a healthy soil environment for plant growth. Specifically, the application of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens at 15 g/kg had the most prominent effect, increasing soil nutrient content, improving soil ecological functions, and enhancing the abundance of potentially beneficial soil bacteria and fungi. These changes collectively contributed to the improved quality of GSO. Our findings provide preliminary insights into the combined effects of different fertilization regimes on the growth of GSO and soil properties, including enzyme activities, nutrients, and microorganisms. Future research should focus on verifying these findings through field experiments and further investigating the interactions between exogenous beneficial microorganisms and indigenous microbial communities in microbial fertilizers. Additionally, it is essential to explore whether these microorganisms can survive stably in natural environments.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by Traditional Chinese Medicine Bureau of Guangdong Province Project (20215007), Traditional Chinese Medicine Bureau Of Guangdong Province Project (20232088), Agricultural and Rural Department of Guangdong Province Project (156012), Guangdong Rural Science and Technology Commissioner Project (KTP20210111).

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Xiaomin Tang and Xiaoli Huang; methodology, Bingbing Zhang and Minghao Li; software, Bingbing Zhang and Siqi Zheng; validation, Guorong Lai and Bingbing Zhang; formal analysis, Bingbing Zhang and Minghao Li; investigation, Bingbing Zhang and Guorong Lai; resources, Quan Yang and Xiaomin Tang; data curation, Quan Yang and Xiaomin Tang; writing—original draft preparation, Bingbing Zhang; writing—review and editing, Xiaomin Tang; supervision, Xiaomin Tang; project administration, Xiaomin Tang and Quan Yang; funding acquisition, Xiaomin Tang and Quan Yang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Balkrishna A, Semwal A, Sharma N, Arya V. Phytochemical and pharmacological profile of Desmodium styracifolium (Osbeck) merr: updated review. Curr Tradit Med. 2023;9(5):90–108. doi:10.2174/2215083809666221209085439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Commission NP. Pharmacopoeia of the People’s Republic of China. Beijing: China Medical Science Press; 2020. [Google Scholar]

3. Wang J, Rhodes G, Huang Q, Shen Q. Plant growth stages and fertilization regimes drive soil fungal community compositions in a wheat-rice rotation system. Biol Fertil Soils. 2018;54(6):731–42. doi:10.1007/s00374-018-1295-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Deng S, Shi K, Ma J, Zhang L, Ma L, Jia Z. Effects of fertilization ratios and frequencies on the growth and nutrient uptake of Magnolia wufengensis (Magnoliaceae). Forests. 2019;10(1):65. doi:10.3390/f10010065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Alami MM, Liu SB, Gong DL, Guo SH, Shaohua S, Mei ZA, et al. Effects of excessive and deficient nitrogen fertilizers on triptolide, celastrol, and metabolite profile content in Tripterygium wilfordii Hook F. Ind Crops Prod. 2023;206:117577. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2023.117577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Shen N, Cui YL, Xu WH, Zhao XH, Yang LC. Impact of phosphorus and potassium fertilizers on growth and anthraquinone content in Rheum tanguticum Maxim. ex Balf. Ind Crops Prod. 2017;107:312–9. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2017.05.044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Lu T, Yang Q, Tang X, Cheng X, Zhang C, Pan H. Effects of combined application of nitrogen, phosphorous and potassium on the yield and quality of Desmodium styracifolium. Chinese J Experim Traditi Med Form. 2014;34(3):426–30. [Google Scholar]

8. Ameeta Sharma AS, Ronak Chetani RC. A review on the effect of organic and chemical fertilizers on plants. Int J Res Appl Sci Eng Technol. 2017;5(2):677–80. doi:10.22214/ijraset.2017.2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Hossain ME, Shahrukh S, Hossain SA. Chemical fertilizers and pesticides: impacts on soil degradation, groundwater, and human health in Bangladesh. In: Singh VP, Yadav S, Yadav KK, Yadav RN, editors. Environmental degradation: challenges and strategies for mitigation. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2022. p. 63–92. [Google Scholar]

10. Yousefzadeh S, Sanavy S, Govahi M, Oskooie OSK. Effect of organic and chemical fertilizer on soil characteristics and essential oil yield in dragonhead. J Plant Nutr. 2015;38(12):1862–76. doi:10.1080/01904167.2015.1061548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Kuziemska B, Wysokinski A, Klej P. Effect of different zinc doses and organic fertilization on soil’s enzymatic activity. J Elementol. 2020;25(3):1089–99. doi:10.5601/jelem.2020.25.1.1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Tabaxi I, Kakabouki I, Zisi C, Folina A, Karydogianni S, Kalivas A, et al. Effect of organic fertilization on soil characteristics yield and quality of Virginia tobacco in Mediterranean area. Emir J Food Agric. 2020;32(8):610–6. doi:10.9755/ejfa.2020.v32.i8.2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Parra-Cota FI, Peña-Cabriales JJ, de los Santos-Villalobos S, Martínez-Gallardo NA, Délano-Frier JP. Burkholderia ambifaria and B.caribensis promote growth and increase yield in Grain Amaranth (Amaranthus cruentus and A-hypochondriacus) by improving plant nitrogen uptake. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e88094. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0088094. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Araujo R, Dunlap C, Franco CMM. Analogous wheat root rhizosphere microbial successions in field and greenhouse trials in the presence of biocontrol agents Paenibacillus peoriae SP9 and Streptomyces fulvissimus FU14. Molecular Plant Pathol. 2020;21(5):622–35. doi:10.1111/mpp.12918. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Mazid M, Khan TA. Future of bio-fertilizers in Indian agriculture: an overview. Int J Agric Food Res. 2015;3(3):10–23. doi:10.24102/ijafr.v3i3.132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Dong LL, Xu J, Zhang LJ, Cheng RY, Wei GF, Su H, et al. Rhizospheric microbial communities are driven by Panax ginseng at different growth stages and biocontrol bacteria alleviates replanting mortality. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2018;8(2):272–82. doi:10.1016/j.apsb.2017.12.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Shen ZZ, Zhong ST, Wang YG, Wang BB, Mei XL, Li R, et al. Induced soil microbial suppression of banana fusarium wilt disease using compost and biofertilizers to improve yield and quality. Eur J Soil Biol. 2013;57:1–8. doi:10.1016/j.ejsobi.2013.03.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Thiele-Bruhn S, Bloem J, de Vries FT, Kalbitz K, Wagg C. Linking soil biodiversity and agricultural soil management. Curr Opin Environ Sustain. 2012;4(5):523–8. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2012.06.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Beckers B, De Beeck MO, Weyens N, Boerjan W, Vangronsveld J. Structural variability and niche differentiation in the rhizosphere and endosphere bacterial microbiome of field-grown poplar trees. Microbiome. 2017;5(1):1–17. doi:10.1186/s40168-017-0241-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Lin YX, Ye GP, Kuzyakov Y, Liu DY, Fan JB, Ding WX. Long-term manure application increases soil organic matter and aggregation, and alters microbial community structure and keystone taxa. Soil Biol Biochem. 2019;134:187–96. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2019.03.030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Zhang Q, Liang GQ, Zhou W, Sun JW, Wang XB, He P. Fatty-acid profiles and enzyme activities in soil particle-size fractions under long-term fertilization. Soil Sci Soc Am J. 2016;80(1):97–111. doi:10.2136/sssaj2015.07.0255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Ding LJ, Su JQ, Sun GX, Wu JS, Wei WX. Increased microbial functional diversity under long-term organic and integrated fertilization in a paddy soil. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2018;102(4):1969–82. doi:10.1007/s00253-017-8704-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Zhalnina K, Louie KB, Hao Z, Mansoori N, da Rocha UN, Shi SJ, et al. Dynamic root exudate chemistry and microbial substrate preferences drive patterns in rhizosphere microbial community assembly. Nat Microbiol. 2018;3(4):470–80. doi:10.1038/s41564-018-0129-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Cui J, Holden NM. The relationship between soil microbial activity and microbial biomass, soil structure and grassland management. Soil Tillage Res. 2015;146:32–8. doi:10.1016/j.still.2014.07.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Zhang MC, Chen H, Li M. Effect of a compound microbial fertilizer on growth, quality, and soil properties of Andrographis paniculata. Chin J Exp Tradit Med Formulae. 2023;29(4):153–60. [Google Scholar]

26. Bao S. Soil agrochemical analysis. Beijing: China Agriculture Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

27. Guan S. Soil enzyme and study method. Beijing: China Agriculture Press; 1986. p. 59–63. [Google Scholar]

28. Yang WL, Gong T, Wang JW, Li GJ, Liu YY, Zhen J, et al. Effects of compound microbial fertilizer on soil characteristics and yield of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). J Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 2020;20(4):2740–8. doi:10.1007/s42729-020-00340-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Chen YH, Guo QS, Liu L, Liao L, Zhu ZB. Influence of fertilization and drought stress on the growth and production of secondary metabolites in Prunella vulgaris L. J Med Plants Res. 2011;5(9):1749–55. [Google Scholar]

30. Hou SS, Zhang RF, Zhang C, Wang L, Wang H, Wang XX. Role of vermicompost and biochar in soil quality improvement by promoting Bupleurum falcatum L. nutrient absorption. Soil Use Manag. 2023;39(4):1600–17. doi:10.1111/sum.12955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Liu L, Xu YS, Cao HL, Fan Y, Du K, Bu X, et al. Effects of Trichoderma harzianum biofertilizer on growth, yield, and quality of Bupleurum chinense. Plant Direct. 2022;6(11):e461. doi:10.1002/pld3.461. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Wishart J, George TS, Brown LK, Ramsay G, Bradshaw JE, White PJ, et al. Measuring variation in potato roots in both field and glasshouse: the search for useful yield predictors and a simple screen for root traits. Plant Soil. 2013;368(1–2):231–49. doi:10.1007/s11104-012-1483-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Füllgrabe H, Claassen N, Hilmer R, Koch HJ, Dittert K, Kreszies T. Potassium deficiency reduces sugar yield in sugar beet through decreased growth of young plants. J Plant Nutr Soil Sci. 2022;185(5):545–53. doi:10.1002/jpln.202200064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Liu J, Hu TT, Feng PY, Wang L, Yang SH. Tomato yield and water use efficiency change with various soil moisture and potassium levels during different growth stages. PLoS One. 2019;14(3):e0213643. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0213643. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Sete PB, Comin JJ, Ciotta MN, Salume JA, Thewes F, Brackmann A, et al. Nitrogen fertilization affects yield and fruit quality in pear. Sci Hortic. 2019;258:108782. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2019.108782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Wei X, Bai X, Cao P, Wang G, Han J, Zhang Z. Bacillus and microalgae biofertilizers improved quality and biomass of Salvia miltiorrhiza by altering microbial communities. Chin Herb Med. 2023;15(1):45–56. doi:10.1016/j.chmed.2022.01.008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Tang SQ, Wei KX, Huang H, Li XH, Min YX, Tai JY, et al. Effect of soil factors on flavonoid metabolites in Striga asiatica using LC-MS based on untargeted metabolomics. Chem Biol Technol Agric. 2024;11(1):89. doi:10.1186/s40538-024-00614-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Wang XG, Zhao XH, Jiang CJ, Li CH, Cong S, Wu D, et al. Effects of potassium deficiency on photosynthesis and photoprotection mechanisms in soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merr.). J Integr Agric. 2015;14(5):856–63. doi:10.1016/S2095-3119(14)60848-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Zhong C, Jian SF, Huang J, Jin QY, Cao XC. Trade-off of within-leaf nitrogen allocation between photosynthetic nitrogen-use efficiency and water deficit stress acclimation in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant Physiol Biochem. 2019;135:41–50. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2018.11.021. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Kang J, Chu YY, Ma G, Zhang YF, Zhang XY, Wang M, et al. Physiological mechanisms underlying reduced photosynthesis in wheat leaves grown in the field under conditions of nitrogen and water deficiency. Crop J. 2023;11(2):638–50. doi:10.1016/j.cj.2022.06.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Li ZH, Gemma H, Iwahori S. Stimulation of ‘Fuji’ apple skin color by ethephon and phosphorus-calcium mixed compounds in relation to flavonoid synthesis. Sci Hortic. 2002;94(1–2):193–9. doi:10.1016/S0304-4238(01)00363-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Li B, Zhang L, Wei LC, Yang YJ, Wang ZX, Qiao B, et al. Effect of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens QST713 on inter-root substrate environment of cucumber under low-calcium stress. Agronomy. 2024;14(3):542. doi:10.3390/agronomy14030542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Nie YX, Wang MC, Zhang W, Ni Z, Hashidoko Y, Shen WJ. Ammonium nitrogen content is a dominant predictor of bacterial community composition in an acidic forest soil with exogenous nitrogen enrichment. Sci Total Environ. 2018;624:407–15. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.12.142. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Guo ZH, Lv L, Liu D, He XM, Wang WT, Feng YZ, et al. A global meta-analysis of animal manure application and soil microbial ecology based on random control treatments. PLoS One. 2022;17(1):e0262139. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0262139. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Shen CC, Liang WJ, Shi Y, Lin XG, Zhang HY, Wu X, et al. Contrasting elevational diversity patterns between eukaryotic soil microbes and plants. Ecology. 2014;95(11):3190–202. doi:10.1890/14-0310.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Jones RT, Robeson MS, Lauber CL, Hamady M, Knight R, Fierer N. A comprehensive survey of soil acidobacterial diversity using pyrosequencing and clone library analyses. ISME J. 2009;3(4):442–53. doi:10.1038/ismej.2008.127. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Fierer N, Lauber CL, Ramirez KS, Zaneveld J, Bradford MA, Knight R. Comparative metagenomic, phylogenetic and physiological analyses of soil microbial communities across nitrogen gradients. ISME J. 2012;6(5):1007–17. doi:10.1038/ismej.2011.159. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Goncalves OS, Fernandes AS, Tupy SM, Ferreira TG, Almeida LN, Creevey CJ, et al. Insights into plant interactions and the biogeochemical role of the globally widespread Acidobacteriota phylum. Soil Biol Biochem. 2024;192:109369. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2024.109369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Shang LR, Wan LQ, Zhou XX, Li S, Li XL. Effects of organic fertilizer on soil nutrient status, enzyme activity, and bacterial community diversity in Leymus chinensis steppe in Inner Mongolia, China. Plos One. 2020;15(10):e0240559. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0240559. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Viaud M, Pasquier A, Brygoo Y. Diversity of soil fungi studied by PCR-RFLP of ITS. Mycol Res. 2000;104(9):1027–32. doi:10.1017/S0953756200002835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Li T, Cui LZ, Song XF, Cui XY, Wei YL, Tang L, et al. Wood decay fungi: an analysis of worldwide research. J Soils Sediments. 2022;22(6):1688–702. doi:10.1007/s11368-022-03225-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Meng LL, Sun T, Li MY, Saleem M, Zhang QM, Wang CX. Soil-applied biochar increases microbial diversity and wheat plant performance under herbicide fomesafen stress. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2019;171:75–83. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2018.12.065. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Gouli VV, Marcelino JA, Gouli SY. Microbial pesticides: biological resources, production and application. Cambridge, MA, USA: Academic Press; 2020. [Google Scholar]

54. Manici LM, Caputo F, De Sabata D, Fornasier F. The enzyme patterns of Ascomycota and Basidiomycota fungi reveal their different functions in soil. Appl Soil Ecol. 2024;196(11):105323. doi:10.1016/j.apsoil.2024.105323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Rimington WR, Duckett JG, Field KJ, Bidartondo M, Pressel S. The distribution and evolution of fungal symbioses in ancient lineages of land plants. Mycorrhiza. 2020;30(1):23–49. doi:10.1007/s00572-020-00938-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Ye GP, Lin YX, Luo JF, Di HJ, Lindsey S, Liu DY, et al. Responses of soil fungal diversity and community composition to long-term fertilization: field experiment in an acidic Ultisol and literature synthesis. Appl Soil Ecol. 2020;145:103305. doi:10.1016/j.apsoil.2019.06.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. De Boer W, Folman LB, Summerbell RC, Boddy L. Living in a fungal world: impact of fungi on soil bacterial niche development. Fems Microbiol Rev. 2005;29(4):795–811. doi:10.1016/j.femsre.2004.11.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Bian XB, Xiao SY, Zhao Y, Xu YH, Yang H, Zhang LX. Comparative analysis of rhizosphere soil physiochemical characteristics and microbial communities between rusty and healthy ginseng root. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):15756. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-71024-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Khoshru B, Mitra D, Khoshmanzar E, Myo EM, Uniyal N, Mahakur B, et al. Current scenario and future prospects of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria: an economic valuable resource for the agriculture revival under stressful conditions. J Plant Nutr. 2020;43(20):3062–92. doi:10.1080/01904167.2020.1799004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools