Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Prevalence and Molecular Diagnosis of Viruses Infecting Fig Trees in Saudi Arabia

1 Plant Protection Department, College of Food and Agriculture Sciences, King Saud University, Riyadh, 145111, Saudi Arabia

2 Department of Plant Pathology, Faculty of Agriculture and Environment, The Islamia University of Bahawalpur, Bahawalpur, 63100, Pakistan

3 Chair of Date Palm Research, Center for Chemical Ecology and Functional Genomics, College of Food and Agriculture Sciences, King Saud University, Riyadh, 11451, Saudi Arabia

* Corresponding Author: Mohammed A. Al-Saleh. Email:

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(3), 897-910. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.063093

Received 05 January 2025; Accepted 26 February 2025; Issue published 31 March 2025

Abstract

The common fig (Ficus carica L.), Moraceae family, is a commonly grown fruit tree in the Mediterranean region. Fig mosaic disease (FMD) poses a substantial threat to Saudi Arabia’s fig-producing economy. A survey was conducted during the two seasons of 2021 and 2022 on fig trees, displaying various fig mosaic disease symptoms. A total of 200 fig leaves and fruit samples were collected from various governorates in several Regions of Saudi Arabia including Riyadh, Tabuk, Hail, Qassim, Al-Jouf, Makkah, Jazan, Al-Madinah, Asir, and Northern Borders. These samples were tested by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) with specific pairs of primers to assess the existence of Fig mosaic virus (FMV), Fig leaf mottle-associated virus 1 (FLMaV-1), Fig leaf mottle-associated virus 2 (FLMaV-2), Fig mild mottle-associated virus (FMMaV) and Fig fleck-associated virus (FFkaV). The results indicate that four viruses were found in mixed infections and tested positive. FMV was detected with a high infection rate of 46% followed by FLMaV-2 with an infection rate of 20%, FMMaV with an infection rate of 16%, and FLMaV-1 with an infection rate of 7%, respectively, while FFkaV was negative in all tested samples. Sequencing and phylogenetic analysis results showed that the FMV isolates shared 90.3% similarity with other FMV isolates, particularly those from Bosnia and Herzegovina (KU198368). While FLMaV-1 showed 92.5% similarity with the reference isolate FLMaV-1 (KX397035), the isolates of FLMaV-2 exhibited 94.7% similarity with reference FLMaV-2 isolate (FN687742), and the isolate of FMMaV showed 94% similarity with reference FMMaV isolate (MG242131) based on sequence comparison. According to the RT-PCR results, FMV was effectively identified in all five fig varieties (Al Faiz Yellow, Asali, Brown Turkey, Iraqi, and Kaab Al-Ghazal). Contrarily, none of these varieties had FLMaV-1, FLMaV-2, or FMMaV. This study investigates the occurrence and economic impact of the viruses that infect fig trees in Saudi Arabia. This suggests that FMV is the primary virus infecting these fig varieties and there is no co-infection with the other tested viruses. These findings underscore the urgent need for implementing region-specific management strategies, such as breeding resistant cultivars, enforcing phytosanitary measures to limit virus spread, and prioritizing vector control to mitigate the economic impact of FMD on Saudi Arabia’s fig industry.Keywords

The common fig (Ficus carica L.) is a member of the Moraceae family and the most-grown fruit tree throughout the Mediterranean [1]. Fig fruits can be consumed either dried or fresh and have a slight laxative effect [2]. Among the recorded fig crop diseases, the most common is fig mosaic disease (FMD), which is destructive and persists as a major obstacle to the productivity of figs and the exchange of germplasm. It was first described in California in the early 1930s [3].

Mosaic-affected trees exhibit various symptoms, primarily on the leaves, including discolorations resembling mosaic, diverse chlorotic blotching and mottling patterns, vein clearing, vein banding, necrotic or chlorotic ring spots, and linear patterns. Apical rosetting and diminished vitality can be seen on the leaves of several plants [4]. FMD is spread experimentally through the graft to figs as well as other species within the Moraceae family, mainly within the Ficus genera (16 species), Morus indica, and Cudrania tricuspidata, the only two tentative hosts recognized to exist from distinct genera.

The eriophyid mite Aceria ficus naturally transmits FMD-causing viruses, although no seed transmission has been reported [5]. The cause of the disease has long been unknown, despite the presence of filiform and isometrical virus particles in ultra-thin sections of symptomatic fig leaf tissues [6]. Fig mosaic virus (FMV) has recently been identified as a part of the Emaravirus genus, family Fimoviridae, as the disease’s causative agent of FMD in 2009, and it was a milestone in the etiology of FMD [7].

The initial molecular evidence for spontaneous fig tree viral infection originates from binary Closteroviridae associates, FLMaV-1 and FLMaV-2, that have been observed in fig plants and demonstrate FMD symptoms in Algeria and Italy [8]. Later, the virus counts infecting figs increased expeditiously, and novel viruses were identified, such as Fig cryptic virus (FCV), FFkaV, FMMaV, and Fig latent virus 1 (FLV-1) [9]. In diseased fig plants, full or partial nucleotide sequences for certain viruses most likely belong to the Caulimoviridae (Badnavirus-like) and Partitiviridae (Luteovirus-like) families, have been discovered [10].

In recent years, producers across Saudi Arabia have complained about slow fig tree development, poor-quality fruit, and low yields. In fig tree orchards, a broad variety of foliar symptoms that resembled FMD symptoms were observed. Among them, there are different patterns of mottling, mosaic, vein banding, and clearing chlorosis as well as yellowing, blotching, and chlorotic ringspot, puckering and leaf curling, blistering, and deformation of leaves have been observed. The goal of this research was to identify and characterize the viruses infecting fig trees, focusing on FMV, FMMaV, FLMaV-1, and FLMaV-2 which were the most probable causes of symptoms similar to FMD examined in Saudi Arabia’s fig-growing regions.

2.1 Field Observations and Sample Collection

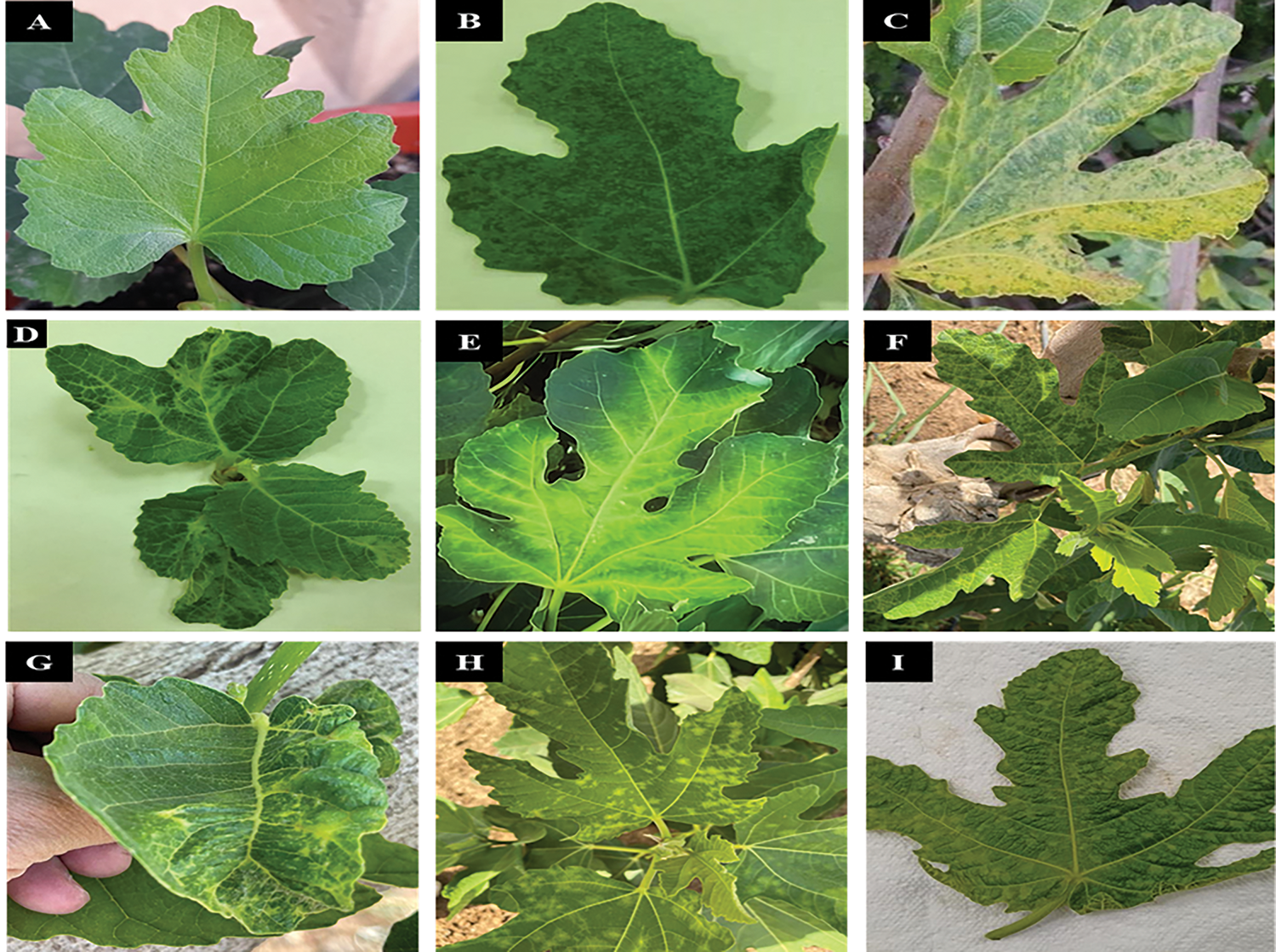

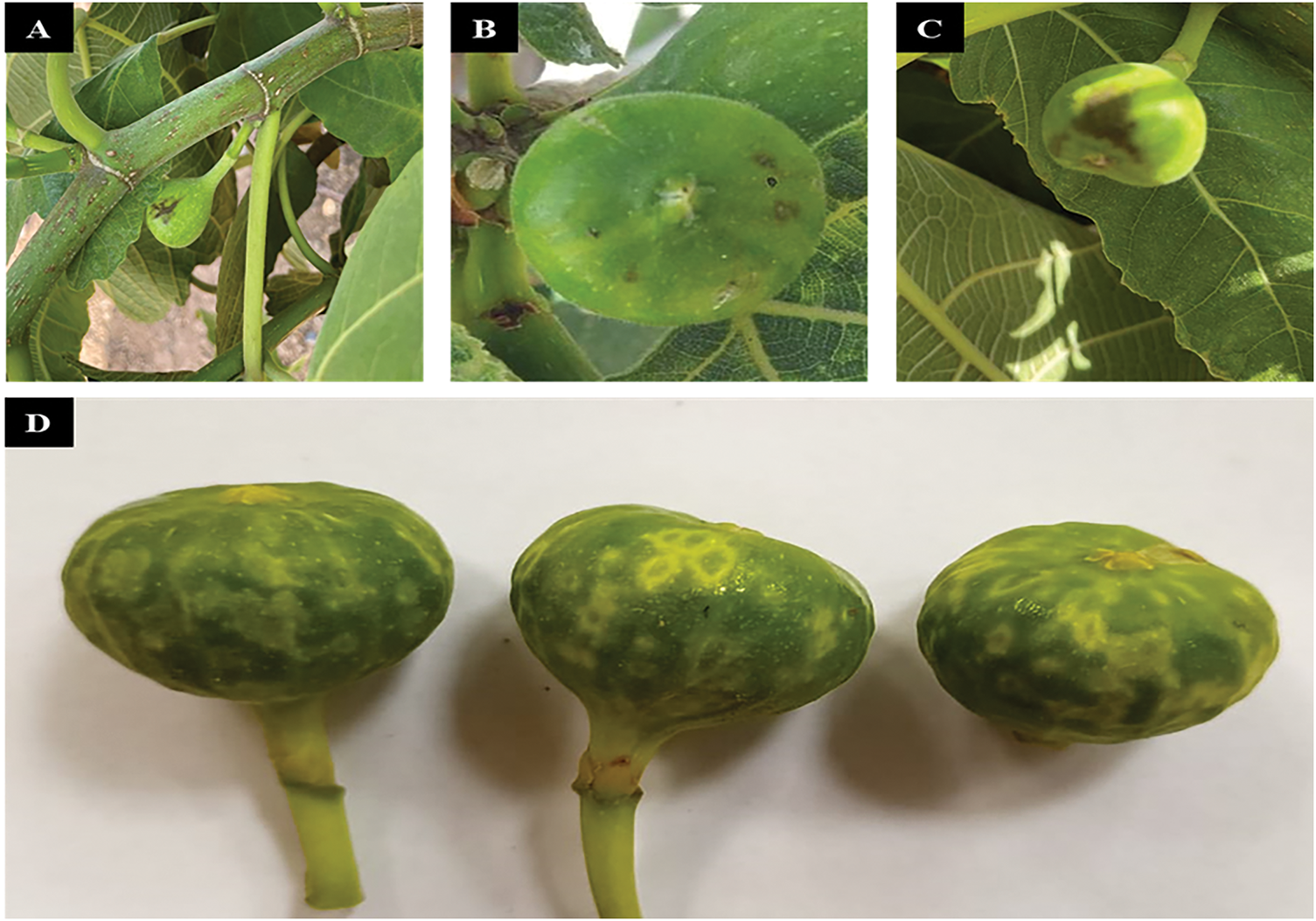

A field survey was carried out on fig trees during the seasons of 2021 and 2022, emphasizing both asymptomatic (Healthy) and symptomatic. A total of 200 samples exhibiting mosaic, mottling, yellowing, chlorotic ringspot, vein clearing, puckering, leaf deformation, and chlorotic blistering; yellow ring spots and necrosis of fruits (Figs. 1 and 2) were collected from different Regions of Saudi Arabia including Riyadh, Tabuk, Hail, Qassim, Al-Jouf, Makkah, Jazan, Al-Madinah, Asir, and Northern Borders.

Figure 1: Several types of symptoms were noticed on fig leaves: healthy (A); mosaic (B); yellowing (C); leaf deformation (D); vein clearing (E); mottling (F); puckering (G); chlorotic spots (H); and chlorotic blistering (I)

Figure 2: Naturally, virus-like symptoms—including yellow ring spots and necrosis—were noticed on the fruit (A–D)

2.2 Total RNA Isolation, RT-PCR, and Thermal Cycling

Total RNA was extracted from asymptomatic and symptomatic fig plant tissues such as leaf veins (100 mg), by using a Gene JET Plant RNA Purification Mini Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific Baltics UAB, Vilnius, Lithuania) as per the manufacturer’s protocol and kept at −20°C until usage.

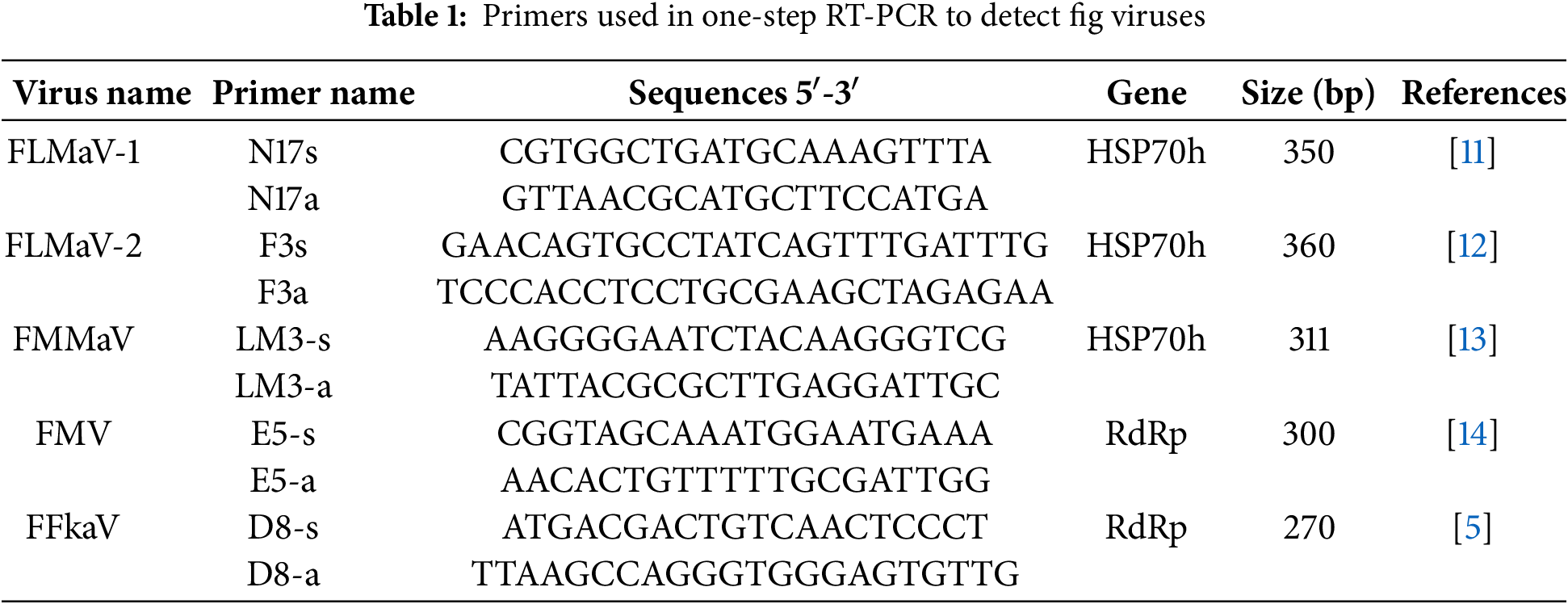

Specific primers of each virus (Table 1) were used to detect FMV, FLMaV-1, FLMaV-2, FMMaV, and FFkaV using SuperScriptTM IV One-Step RT-PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific Baltics UAB, Vilnius, Lithuania). Briefly, a 25 μL reaction mixture comprising 5 μL RNA and 20 μL reagents was used for amplification. The one-step RT-PCR reaction was performed at 60°C for 10 min, 98°C for 2 min, and followed by 40 cycles at 94°C for 30 s, 55°C–58°C for 30 s, 72°C for 1 min. Then, the final extension step was done at 72°C for 10 min. The amplified RT-PCR products were analyzed in agarose gel (1%) in 1X TBE buffer at 100 V for 30–45 min, stained with acridine orange (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Vilnius, Lithuania), and the bands were visualized under UV illustration using a DNA gel Documentation System (Syngene GeneGenius Bio Imaging System, Cambridge, UK). The size of the RT-PCR amplified products was measured using a DNA ladder (100 bp) GeneRuler (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

2.3 Partial Nucleotide Sequencing

For two-directional sequencing, the RT-PCR results of eleven chosen positive fig samples with FMV, FLMaV-1, FLMaV-2, and FMMaV have been submitted to the Macrogen (Macrogen Inc., Seoul, South Korea). The obtained sequence results were analyzed using the BLAST program (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.blast). The ClustalW was used for sequence alignment, and the phylogenetic tree was constructed on MEGA-X (http://www.megasoftware.net/mega.php (accessed on 1 January 2025)), using the maximum likelihood method with 1000 bootstrap replications. The Saudi isolates’ nucleotide identity and comparison with other isolates that were deposited in the GenBank database were done using DNASTAR Lasergene (https://www.dnastar.com/software/lasergene/ (accessed on 1 January 2025)).

2.4 Biological Indexing of Fig Mosaic Virus

Virus indexing was conducted on five fig varieties: Al Faiz Yellow, Asali, Brown Turkey, Iraqi, and Kaab Al-Ghazal. Initially, RT-PCR was performed to inspect the fig varieties for the presence of FMV, FLMaV-1, FLMaV-2, FMMaV, and FFkaV to select the negative rootstock. Moreover, infected scions with FMV were grafted onto healthy rootstocks using the tongue grafting method. The two pieces were wrapped together using transparent tape (sometimes called tree tape). The grafting process transmitted the virus, and the stock displayed symptoms that the virus was present in the scion.

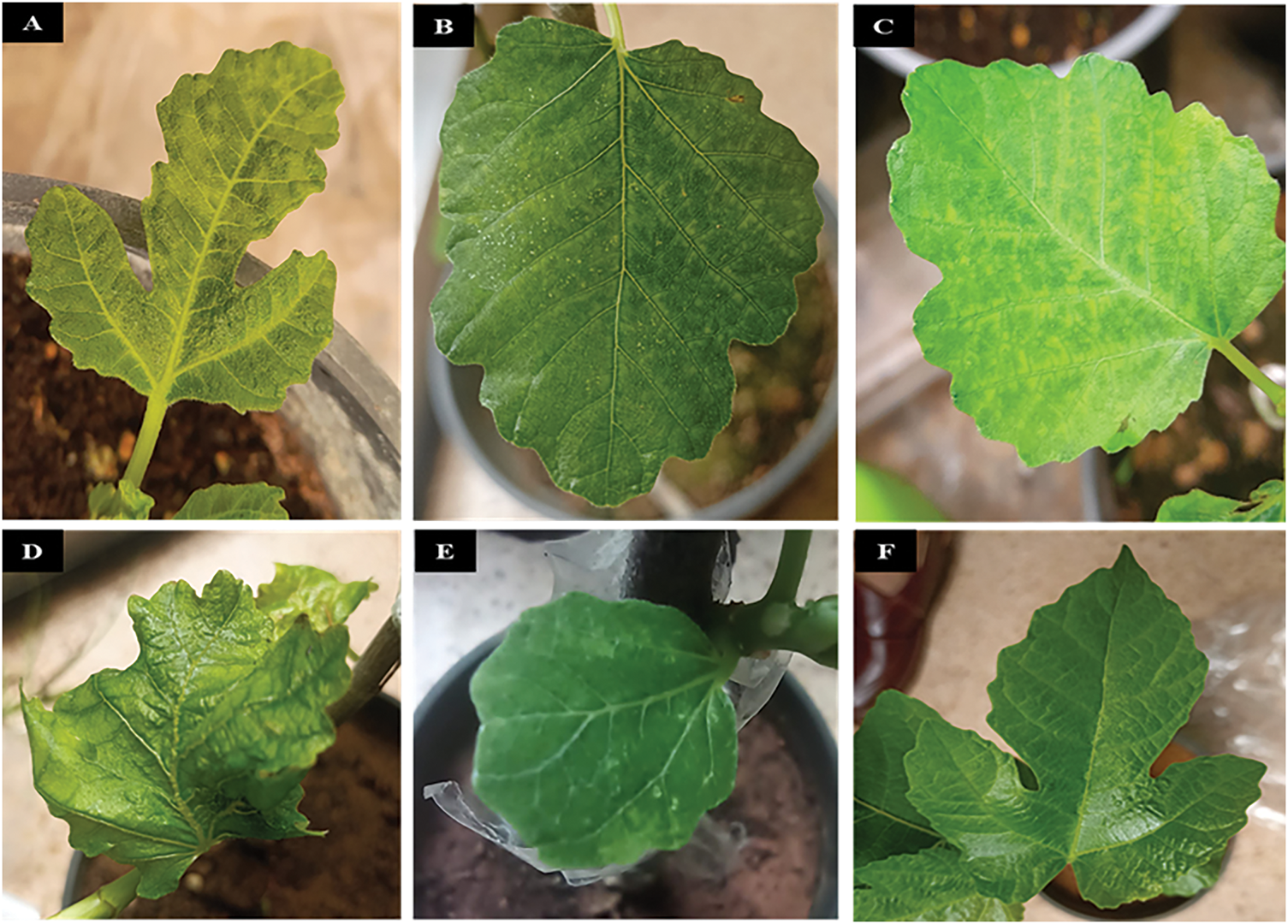

Two hundred symptomatic and asymptomatic fig samples were collected from different Regions of Saudi Arabia. Almost two-thirds of the fig trees examined visually showed one or more virus-like symptoms such as mosaic, yellowing, leaf deformation, vein clearing, mottling, puckering, and chlorotic spots (Fig. 1). Meanwhile, the symptoms on fruits were observed as chlorosis, local lesions, mosaic, and ring spots, the newly developed fruits were found to have yellow ring spots that varied in size. The necrotic spots and fruit drops were also noticed (Fig. 2).

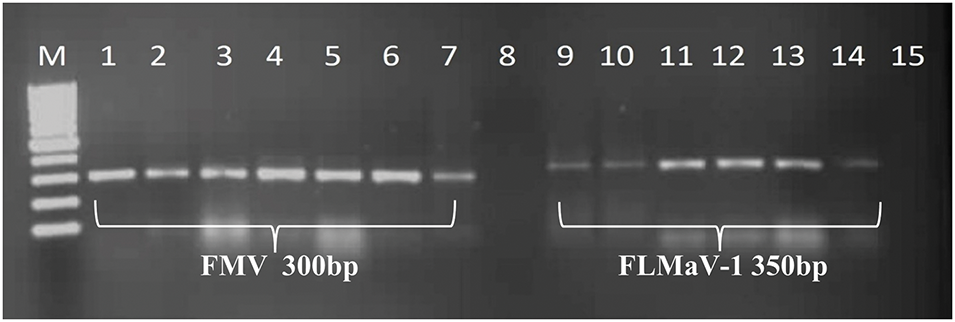

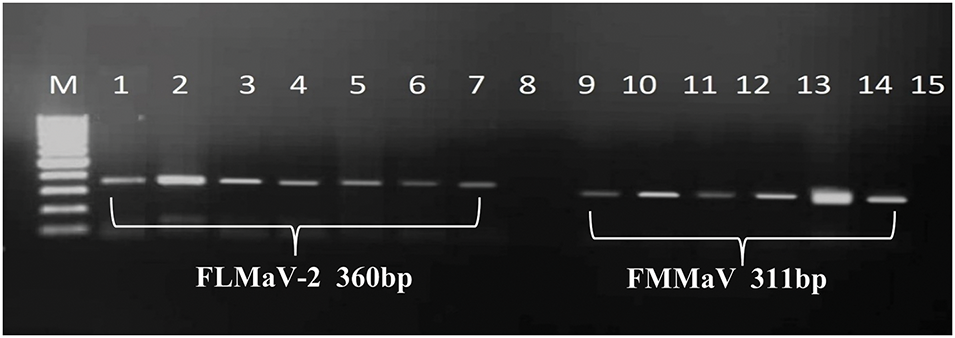

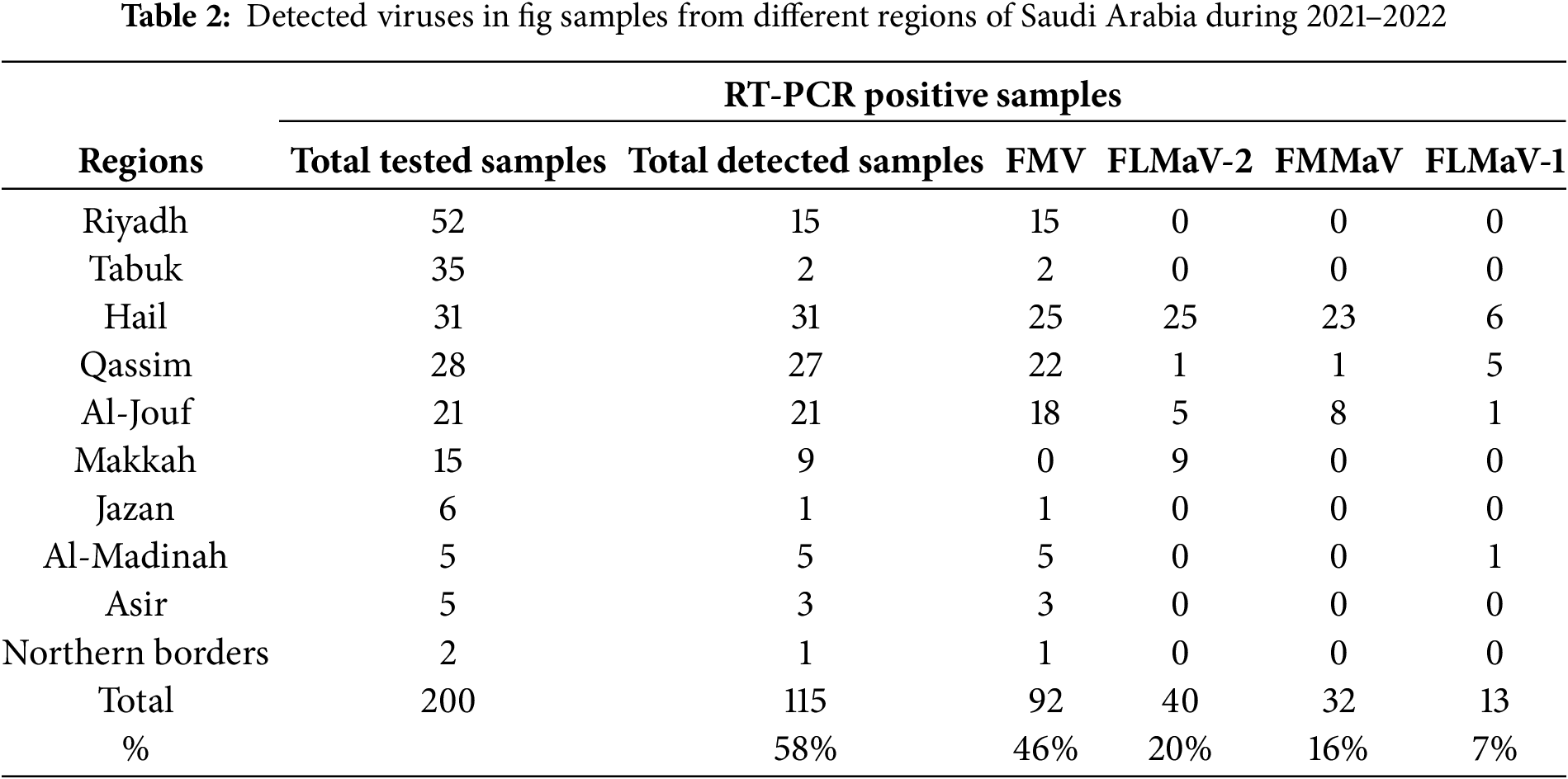

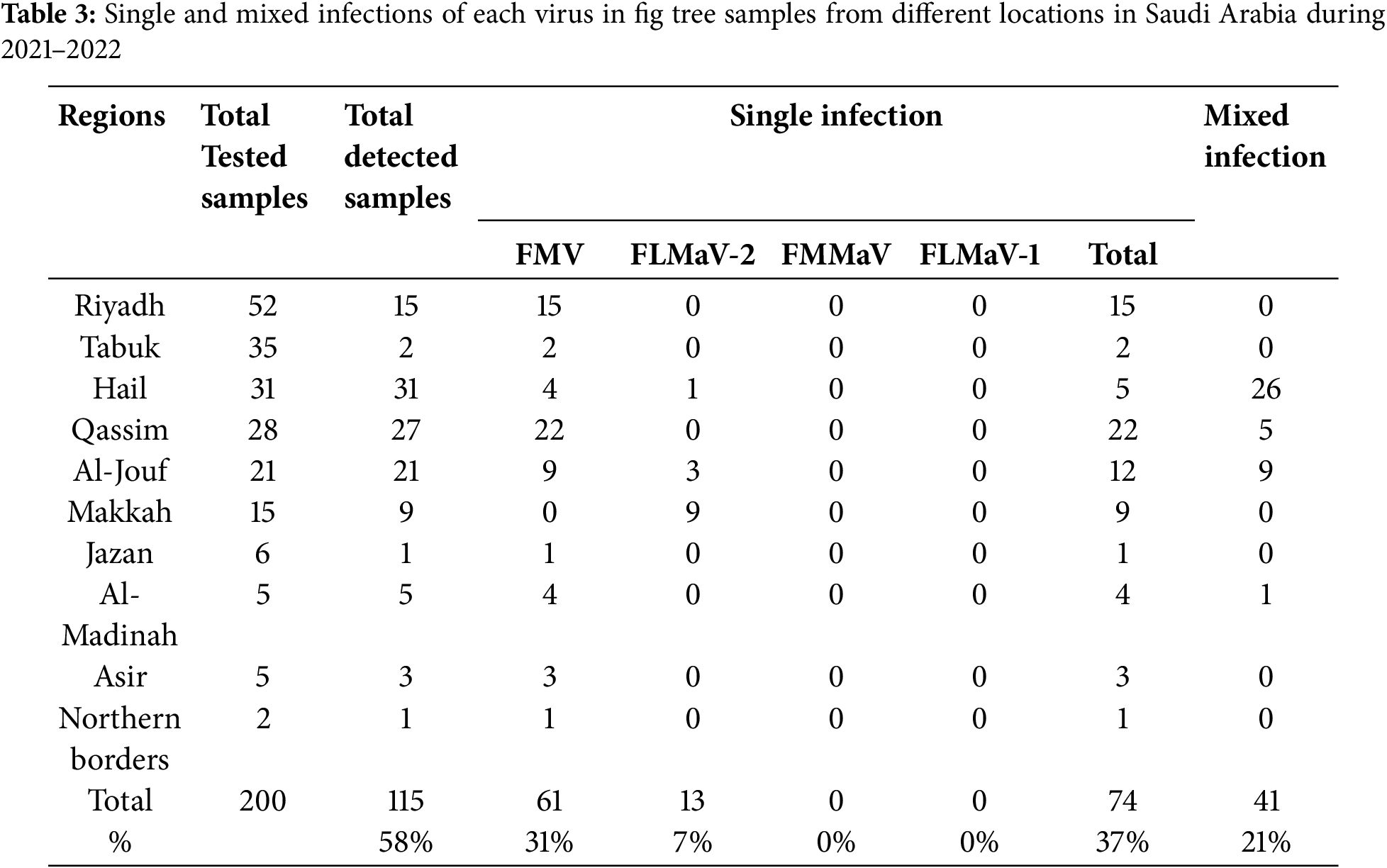

The RT-PCR results showed that four out of the five fig viruses tested positive, namely FMV, FLMaV-1, FLMaV-2, and FMMaV. While no positive results were obtained with FFkaV. For each detected virus the DNA amplicons with typical sizes of 300 bp, 311 bp, 350 bp, and 360 bp were obtained from RT-PCR assays of the tested samples for FMV, FMMaV, FLMaV-1, and FLMaV-2, respectively (Figs. 3 and 4). Additionally, 115 out of 200 fig samples (58%) were positive for the four viruses and the percentage was as follows: FMV was the most prevalent virus infecting 46% (92/200) followed by FLMaV-2 infecting 20% (40/200), FMMaV infecting 16% (32/200), and FLMaV-1 infecting 7% (13/200). Meanwhile, the overall infection was recorded (58%), with the highest rate of (100%) in Al-Jouf, Al-Madinah, Hail, and Asir Regions, followed by Qassim (96%), Makkah (60%), Northern Borders (50%), Riyadh (29%), Jazan (17%) and Tabuk (6%). Samples collected from Hail and Al-Jouf Regions exhibited a high degree of mixed infections, 84%, and 43%, respectively. The following were the mixed viral infections percentage: 59% (24/41) had FLMaV-2 + FMMaV, 15% (6/41) comprised FMV + FLMaV-1, 5% (2/41) contained FMV + FLMaV-1 + FLMaV-2, and all four viruses were found in 22% (9/41). However, 74 fig samples out of 200 (37%) showed a single infection (Tables 2 and 3).

Figure 3: A 1% agarose gel depicted positive samples from the tested viruses. Lane M represents the 100 bp DNA Ladder (GeneRuler, Thermo Scientific, USA). Lanes 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 are positive for FMV and show their bands at 300 bp, compared to the ladder. Likewise, lanes 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, and 14 are positive for FLMaV-1 and show their bands at 350 bp, compared to the ladder. However, lanes 8 and 15 are negative controls for their respective viruses

Figure 4: A 1% agarose gel depicted positive samples from the tested viruses. Lane M represents the 100 bp DNA Ladder (GeneRuler, Thermo Scientific, USA). Lanes 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 are positive for FLMaV-2 and show their bands at 360 bp, compared to the ladder. Likewise, lanes 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, and 14 are positive for FMMaV and show their bands at 311 bp, compared to the ladder. However, lanes 8 and 15 are negative controls for their respective viruses

3.3 Biological Indexing of FMV

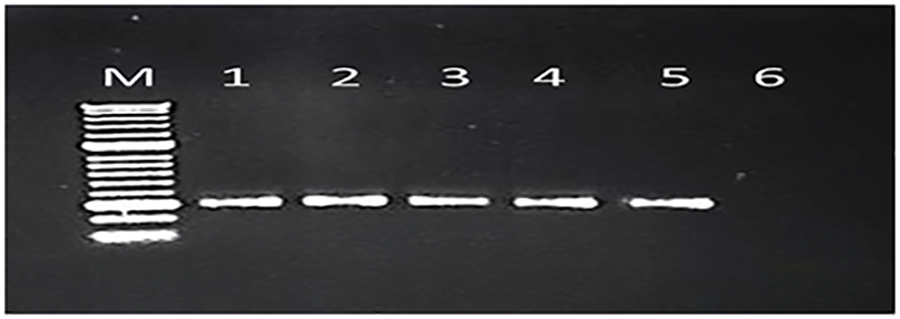

The findings revealed that fig varieties (Al Faiz Yellow, Asali, Brown Turkey, Iraqi, and Kaab Al-Ghazal) had a single infection of FMV. However, FLMaV-1, FLMaV-2, FMMaV, and FFkaV were negative. Additionally, the tongue grafting method’s effectiveness in detecting FMV was confirmed by the successful virus transmission in all grafting trials. The grafted plants were monitored daily, and after eight weeks of grafting, the grafted plants began to exhibit symptoms consistent with mosaic disease, as observed in fig plants. These symptoms include leaf mosaic, yellowing, puckering, and deformation (Fig. 5). Each variety had two control plants used in comparison with the grafted plants. The RT-PCR reactions of the grafted plants were carried out using specific pairs of primers for FMV, FLMaV-1, FLMaV-2, FMMaV, and FFkaV and the obtained results indicate that FMV was successfully detected in all five fig varieties (Al Faiz Yellow, Asali, Brown Turkey, Iraqi, and Kaab Al-Ghazal) with the exact expected size of 300 bp when compared with 100 bp DNA Ladder (GeneRuler, USA) (Fig. 6).

Figure 5: Symptom development after grafting, such as mosaic, leaf mosaic, yellowing, puckering, and deformation were observed in five different fig varieties. (A) Iraqi, (B) Brown Turkey, (C) Al Faiz Yellow, (D) Asali, and (E) Kaab Al-Ghazal are infected; however, (F) is healthy

Figure 6: The grafted plants were re-confirmed after symptom expression by RT-PCR. A 1% agarose gel shows the amplification of bands at 300 bp, exactly matching the size of primers. M stands for the 100 bp Hyperladder. Lanes: 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 are positive for FMV (Iraqi, Brown Turkey, Al Faiz Yellow, Asali, and Kaab Al-Ghazal, respectively). However, lane 6 is a negative control

3.4 Partial Nucleotide Sequencing and Phylogenetic Tree Analysis

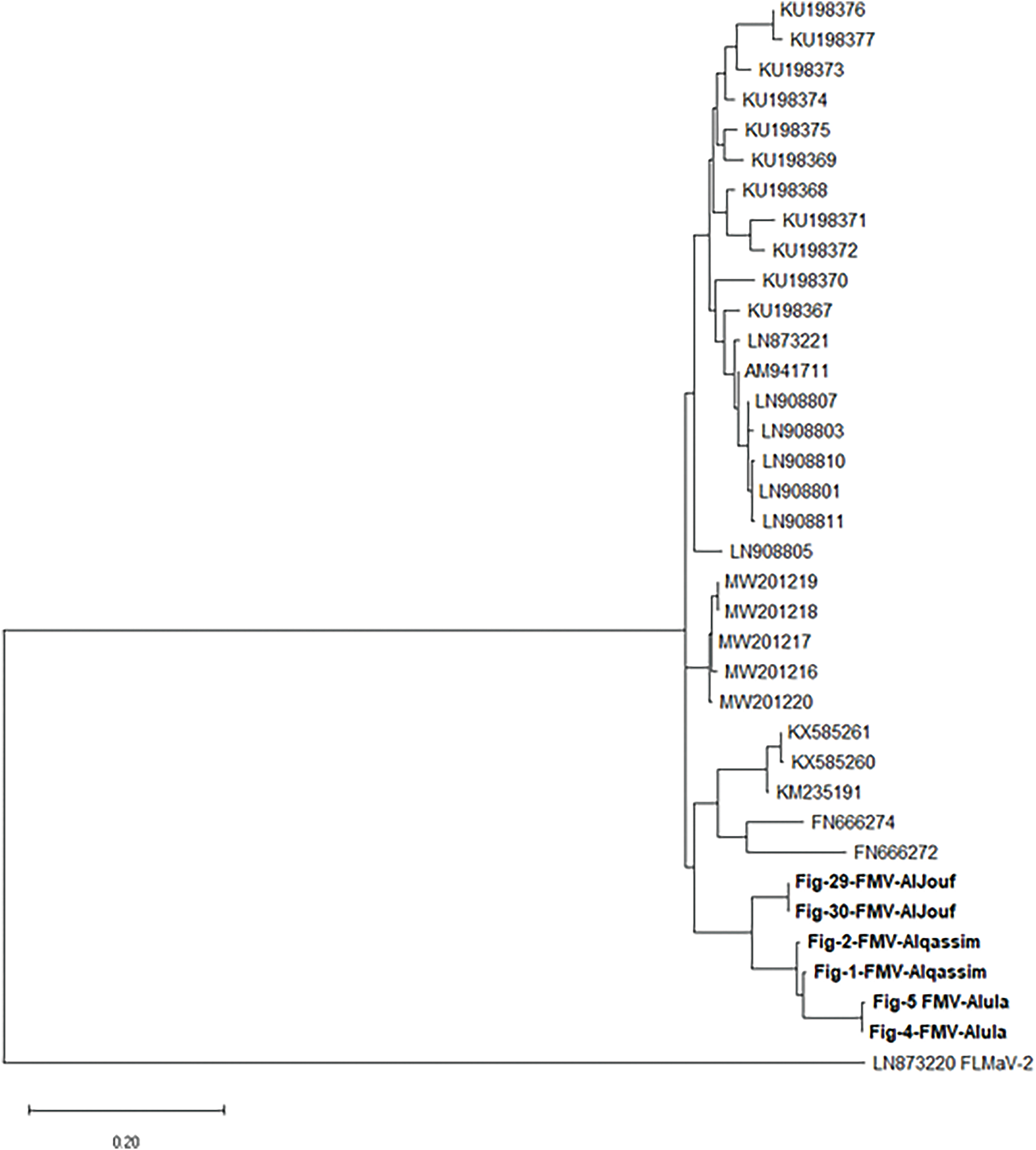

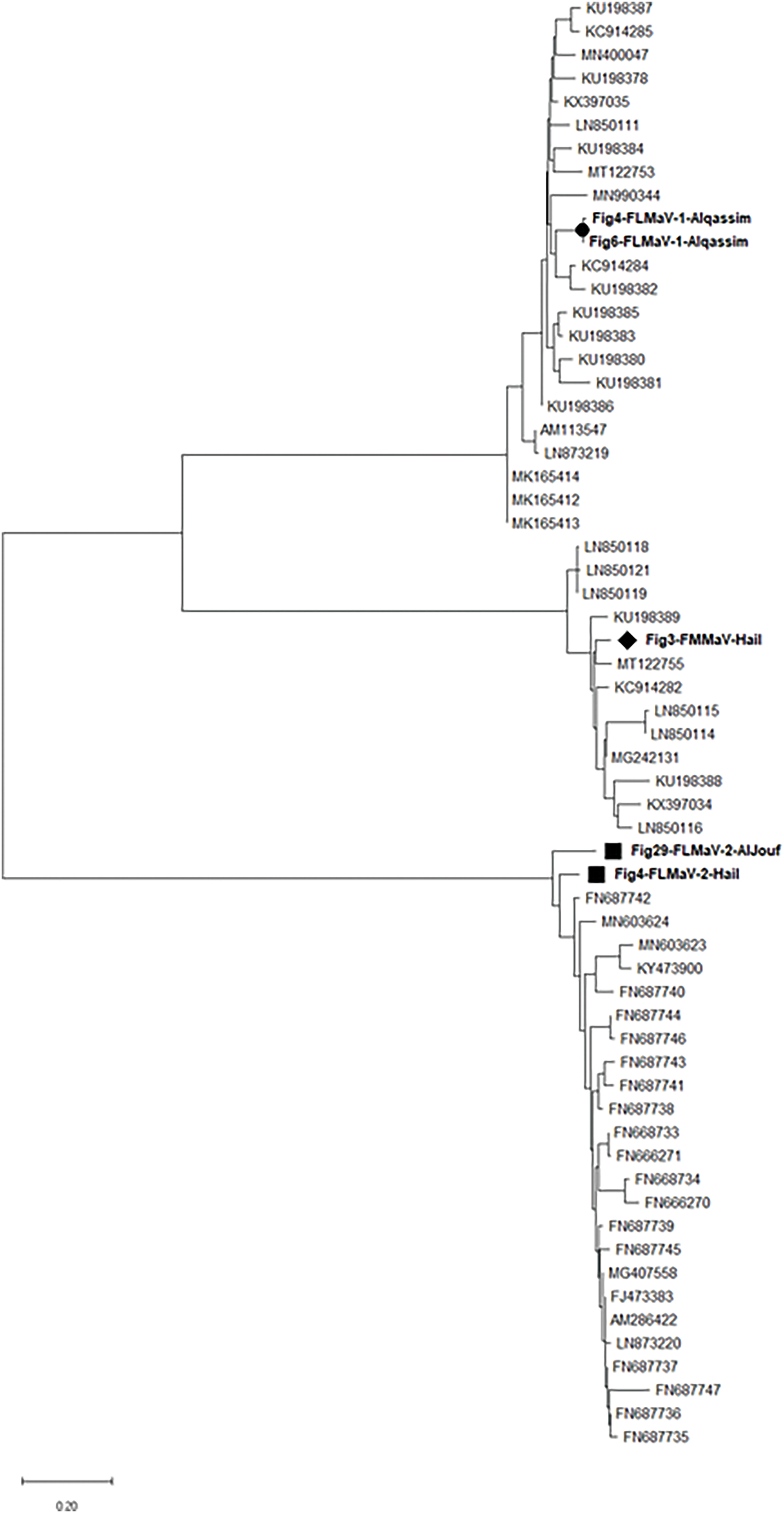

The partial nucleotide sequences for the 11 isolates obtained from different Regions and Governorates in Saudi Arabia were analyzed using the BLAST program in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database, and they showed similarity with their respective viruses around the world which have already been posted in NCBI GenBank database. The sequences were submitted to the GenBank database with accession numbers ON184193, ON184194, ON184195, ON184196, ON184197, ON184198 for FMV, ON184199, ON184200 for FLMaV-1, ON184201, ON184202 for FLMaV-2, and ON184203 for FMMaV, respectively. Phylogenetic analysis showed that FMV Saudi Arabian isolates formed a distinct cluster with previously identified FMV isolates (Fig. 7). Specifically, Saudi isolates exhibited 90.3% nucleotide identity with FMV strains from Bosnia and Herzegovina, with similarity ranging from 83.3% to 90.3% compared to other published FMV isolates. The FLMaV-1, FLMaV-2, and FMMaV isolates are also grouped in separate clusters, sharing 85% to 94.7% similarity with their global counterparts (Fig. 8). The phylogenetic tree was constructed using the maximum likelihood method with 1000 bootstrap replicates, enhancing the strength of the genetic analysis. MEGA-X was chosen for phylogenetic tree construction due to its advanced computational efficiency and accuracy in evolutionary analysis. ClustalW was used for sequence alignment as it ensures high-quality multiple sequence alignment, crucial for precise phylogenetic interpretations.

Figure 7: The phylogenetic tree of the FMV isolates from Saudi Arabia shows nucleotide similarity with the other corresponding isolates from various countries

Figure 8: The phylogenetic tree of the FLMaV-1, FLMaV-2, and FMMaV isolates from Saudi Arabia shows nucleotide similarity with other corresponding isolates from various countries

FMD is a complex viral disease affecting fig trees, caused by multiple viruses, including Fig mosaic virus (FMV), Fig leaf mottle-associated virus 1 (FLMaV-1), FLMaV-2, and Fig mild mottle-associated virus (FMMaV). These viruses induce symptoms such as leaf mosaic, mottling, and yield loss, severely impacting fig production and germplasm exchange. FMD is globally distributed, with reports spanning Mediterranean countries (e.g., Italy, Tunisia), the Middle East (e.g., Lebanon, Saudi Arabia), Europe (e.g., Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro), and regions like Mexico and South Africa. Its spread is facilitated by vectors (e.g., eriophyid mites) and infected plant material [15,16].

FMD prevalence varies seasonally and is influenced by environmental factors (e.g., temperature, humidity), tree health, and regional cultivation practices [17]. For instance, Saudi Arabia’s detection rates differed across regions (e.g., four viruses in the Qassim, Al-Jouf, and Hail, two viruses in the Al-Ula, one virus in Riyadh, Makkah, Tabuk, Jazan, Asir, and Northern Borders Regions were identified), likely reflecting local climatic and agricultural conditions. RT-PCR proved effective for detection, identifying mixed infections (21%) and single infections (37%), with FMV dominating (46%). This uneven detection of tested viruses across different regions of Saudi Arabia can be due to the variations in vector populations, particularly the eriophyid mite Aceria ficus [18], likely influenced the widespread presence of FMV, while the lower detection of FLMaV-1, FLMaV-2, and FMMaV may reflect limited vector activity or specific ecological niches. Host-virus compatibility also played a role, as different fig varieties may vary in susceptibility, with FMV exhibiting broad adaptability. Mixed infections could further suppress less aggressive viruses. Sampling bias, including a focus on symptomatic trees and differences in RT-PCR sensitivity, may have influenced detection rates. Additionally, conventional agricultural practices and regional phytosanitary measures, such as disease management and pesticide use, might have impacted viral diversity, with stricter controls potentially reducing the prevalence of certain viruses. These variations highlight the necessity for region-specific monitoring aligned with seasonal and ecological dynamics.

The study is a “significant milestone” as the first comprehensive survey of fig viruses in Saudi Arabia, revealing a high infection rate (58% of 200 samples) and identifying FMV, FLMaV-1, FLMaV-2, and FMMaV in previously unreported regions. The structured detection rates (e.g., “37% single infections, 21% mixed infections”) highlight the complexity of FMD epidemiology in the country, providing critical baseline data for future research and management.

Previous studies detected FMD-associated viruses in fig leaves, with FLMaV-1 and FLMaV-2 prevalence ranging from 20%–60% and 29%–65%, respectively, in Asian and Mediterranean countries [19–21]. This study corroborates these trends but reports lower FLMaV-1/FLMaV-2 rates in Saudi Arabia (7% and 20%, respectively). Conversely, FMV’s high prevalence (46%) aligns with its known association with eriophyid mite vectors, consistent with earlier findings on its role in FMD symptom severity [22,23].

Partial sequencing revealed Saudi isolates of FLMaV-1, FLMaV-2, and FMMaV cluster with global strains but exhibit nucleotide identity variations (e.g., FMV-Saudi isolate exhibited 90.3%, 89.9%, 89.2%, 88.9%, and 88.2% similarities with Bosnia and Herzegovina, Russia, Turkey, Tunisia, and Montenegro isolates, respectively, while FLMaV-1 Saudi isolates shared 92.5%, 91%, 89.5%, 89.5%, and 86.5% similarities with Montenegro, Spain, Italy, Tunisia, and Turkey isolates, respectively. Whereas FLMaV-2 Saudi isolates shared 94.7%, 91.7%, 88.7%, 88%, 87.2%, and 84.2 similarities with Lebanon, Palestine, Algeria, Syria, Albania, and Turkey isolates, respectively. Additionally, the FMMaV Saudi isolates shared 94%, 93.2%, 91.7%, 89.5%, and 86.5% similarities with Iran, Greece, Tunisia, Montenegro, and Bosnia and Herzegovina isolates, respectively). These results align with the findings of those who claimed that the isolates of FMV, FLMaV-1, FLMaV-2, and FMMaV from Montenegro shared 95%–84% similarity with other Mediterranean isolates of the same viruses that were published in the GenBank database [24]. These genetic differences suggest localized viral evolution, possibly influencing vector interactions or symptom severity. Such variations highlight the need for region-specific diagnostic tools (e.g., updated primers) and management strategies, including vector control and certified pathogen-free planting material.

Although out of the 200 tested fig samples, 85 showed negative results. However, it is important to note that despite the negative results, these samples still exhibited symptoms; it could be due to nutritional deficiencies, environmental conditions, or maybe the presence of other FMD-associated viruses in addition to the five viruses that have been tested. To resolve this, extensive virus screening (e.g., high-throughput sequencing) is recommended to uncover all potential contributors to FMD.

FMV was the most prevalent virus (46%), detected in all five tested fig varieties, while FLMaV-1, FLMaV-2, and FMMaV showed lower rates (7%, 20%, and 16%, respectively). FFkaV was absent. FMV’s dominance likely reflects efficient transmission by eriophyid mites and the use of infected propagation materials. This emphasizes FMV’s key role in FMD outbreaks and the urgency of targeted vector control and sanitation programs to curb its spread.

The study provides important insights into the epidemiology of fig mosaic disease FMD in Saudi Arabia, emphasizing the widespread prevalence of the FMV in various geographic regions and fig varieties. FMV was detected in 46% of the samples, highlighting its role as the primary pathogen responsible for economic losses associated with FMD. This finding aligns with global trends, where FMV is recognized as the most economically significant virus affecting figs. It is often linked to eriophyid mite vectors (Aceria ficus), facilitating rapid transmission in Mediterranean and Middle Eastern regions [9,13,25].

The high infection rate in Saudi Arabia suggests favorable conditions for the proliferation of these vectors, such as warm climates and inadequate control practices, which are known to worsen the spread of the virus [26].

The geographic distribution of FMV across all surveyed regions-including Riyadh, Tabuk, and Jazan-indicates the presence of widespread inoculum sources, which the movement of infected plant materials may exacerbate. Similar patterns of long-distance virus dispersal through trade have been observed in Bosnia and Herzegovina [27], where FMV isolates, phylogenetically related to those found in Saudi Arabia, were linked to international fig exchanges [28]. This underscores the need for strict phytosanitary measures to prevent the inadvertent introduction of pathogens, as the International Plant Protection Convention [29] recommended.

Notably, FLMaV-1, FLMaV-2, and FMMaV exhibited lower prevalence rates (7%–20%), with no co-infections identified in the five tested varieties. This contrasts with findings in Italy and Turkey, where mixed infections are prevalent, suggesting possible regional differences in host susceptibility or vector preferences [30]. The absence of FFkaV in collected samples may reflect specific ecological requirements or limited vector compatibility, as the transmission dynamics of FFkaV remain poorly understood.

The present study investigates the occurrence and economic impact of the viruses that infect Saudi Arabian fig orchids. Further investigation into other fig-infecting viruses and the development of a program to produce virus-free seedlings, native varieties of fig can be utilized as healthy parental plants for propagation and circulation to growers are needed to fully assess this culture’s sanitary state.

Acknowledgement: The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research, King Saud University, for funding through the Vice Deanship of Scientific Research Chairs, the chair of date palm research.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Conceived the project, sample collection and designed the studies: Muhammad Zaman, Mahmoud A. Amer, Mohammed A. Al-Saleh and Ibrahim M Al-Shahwan. Analysis of data and drafting of the manuscript: Muhammad Zaman, Mahmoud A. Amer, Muhammad Amir, Muhammad Taimoor Shakeel and Zaheer Khalid. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Some data is presented within the article, while additional information is available upon request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Mazzeo A, Magarelli A, Ferrara G. The fig (Ficus carica L.varietal evolution from Asia to Puglia region, southeastern Italy. CABI Agric Biosci. 2024;5(1):57. doi:10.1186/s43170-024-00262-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Hussain SZ, Naseer B, Qadri T, Fatima T, Bhat TA. Fig (Ficus Carica) morphology, taxonomy, composition and health benefits. In: Fruits grown in highland regions of the himalayas: nutritional and health benefits. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2021. p. 77–90. [Google Scholar]

3. Toima NI, El-Banna OM, Sayed AM, Youssef SA, Shalaby AA. Incidence, molecular detection, and partial nucleotide sequencing of some viruses causing fig mosaic disease (FMD) on fig plants in Egypt. Int J Microbiol. 2022;2022(2):2093655–9. doi:10.1155/2022/2093655. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Pedrelli A, Panattoni A, Nali C, Cotrozzi L. Occurrence of fig mosaic disease in Tuscany, central Italy: characterization of new fig mosaic virus isolates, and elucidation of physiochemical responses of infected common fig cv. Dottato. Sci Hortic. 2023;322(7–8):112440. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2023.112440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Preising S, Borges DF, de Queiroz Ambrósio MM, da Silva WL. A fig deal: a global look at fig mosaic disease and its putative associates. Plant Dis. 2021;105(4):727–38. doi:10.1094/PDIS-06-20-1352-FE. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Ramon J, Segarra J, Medina V, Achón MA, López M, Juárez M, et al. New approach in the identification of the causal agent of fig mosaic disease. In: XIX International Symposium on Virus and Virus-Like Diseases of Temperate Fruit Crops-Fruit Tree Diseases 657; 2003 Jul 21–25; Valencia, Spain. p. 559–66. [Google Scholar]

7. Latinović J, Radišek S, Bajčeta M, Jakše J, Latinović N. Viruses associated with fig mosaic disease in different fig varieties in Montenegro. Plant Pathol J. 2019;35(1):32–40. doi:10.5423/PPJ.OA.04.2018.0058. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Jamous RM, Zaitoun SYA, Mallah OB, Shtaya M, Elbeaino T, Ali-Shtayeh MS. Detection and phylogenetic analysis of viruses linked with fig mosaic disease in seventeen fig cultivars in Palestine. Plant Pathol J. 2020;36(3):267–79. doi:10.5423/PPJ.OA.01.2020.0001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Al-Kaeath N, Elair M, Mahfoudhi N. Prevalence and distribution of viruses associated with fig mosaic disease in Iraq. Tunis J Plant Prot. 2024;19(1):1–12. doi:10.4314/tjpp.v19i1.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Aldhebiani AY, Elbeshehy EKF, Baeshen AA, Elbeaino T. Inhibitory activity of different medicinal extracts from Thuja leaves, ginger roots, Harmal seeds and turmeric rhizomes against Fig leaf mottle-associated virus 1 (FLMaV-1) infecting figs in Mecca region. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2017;24(4):936–44. doi:10.1016/j.sjbs.2015.11.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Afechtal M. Sanitary selection of four virus-tested fig (Ficus carica L.) cultivars in Morocco. Mor J Agri Sci. 2020;1(2):101–3. [Google Scholar]

12. Alsaheli Z, Abdallah A, Incerti O, Shalaby A, Youssef S, Digiaro M, et al. Development of singleplex and multiplex real-time (Taqman®) RT-PCR assays for the detection of viruses associated with fig mosaic disease. J Virol Methods. 2021;293(2):114145. doi:10.1016/j.jviromet.2021.114145. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Borroto Fernandez EG, Elbeaino T, Fürnsinn F, Keutgen A, Keutgen N, Laimer M. First report of virus detection in Ficus carica in Austria. Phytopathol Mediterr. 2022;2024:9–14. doi:10.36253/phyto-14952. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Ishikawa K, Maejima K, Nagashima S, Sawamura N, Takinami Y, Komatsu K, et al. First report of fig mosaic virus infecting common fig (Ficus carica) in Japan. J Gen Plant Pathol. 2012;78(2):136–9. doi:10.1007/s10327-012-0359-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Castellano MA, Gattoni G, Minafra A, Conti M, Martelli GP. Fig mosaic in mexico and south Africa. J Plant Pathol. 2007;89(3):441–4. [Google Scholar]

16. Alkowni R, Chiumenti M, Minafra A, Martelli G. A survey for fig-infecting viruses in Palestine. J Plant Pathol. 2015;97:383–6. doi:10.4454/JPP.V97I2.034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Bayoudh C, Elair M, Labidi R, Majdoub A, Mahfoudhi N, Mars M. Efficacy of tissue culture in virus elimination from caprifig and female fig varieties (Ficus carica L.). Plant Pathol J. 2017;33(3):288–95. doi:10.5423/PPJ.OA.10.2016.0205. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Rehanek M, Karlin DG, Bandte M, Al Kubrusli R, Nourinejhad Zarghani S, Candresse T, et al. The complex world of emaraviruses—challenges, insights, and prospects. Forests. 2022;13(11):1868. doi:10.3390/f13111868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Mijit M, He Z, Hong J, Lu MG, Li SF, Zhang ZX. Analysis of fig tree virus type and distribution in China. J Integr Agric. 2017;16(6):1417–21. doi:10.1016/S2095-3119(16)61551-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Elbeaino T, Digiaro M, Alabdullah A, De Stradis A, Minafra A, Mielke N, et al. A multipartite single-stranded negative-sense RNA virus is the putative agent of fig mosaic disease. J Gen Virol. 2009;90(Pt 5):1281–8. doi:10.1099/vir.0.008649-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Elbeshehy EKF, Elbeaino T. Viruses infecting figs in Egypt. Phytopathol Mediterr. 2011;50(2):327–32. doi:10.14601/Phytopathol_Mediterr-8741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Bester R, van Niekerk C, Maree HJ. Analyses of fig (Ficus carica L.) leaves for virome profiling of mosaic diseased trees from the Western Cape Province (South Africa). J Plant Pathol. 2023;105(3):1115–21. doi:10.1007/s42161-023-01405-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Aldhebiani A, Elbeshehy E, Baeshen AA, Elbeaino T. Four viruses infecting figs in western Saudi Arabia. Phytopathol Mediterr. 2007;54:497–503. doi:10.14601/PHYTOPATHOL_MEDITERR-16318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Delić D, Perović T, Hrnčić S, Lolić B, Ðurić G, Elbeaino T. Detection and phylogenetic analyses of fig-infecting viruses in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Montenegro. Phytopathol Mediterr. 2017;56(3):470–8. doi:10.14601/Phytopathol_Mediterr-20842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Caglayan K, Elci E, Serce CU, Kaya K, Gazel M, Medina V. Detection of fig mosaic virus in viruliferous eriophyid mite Aceria ficus. J Plant Pathol. 2012;94:629–34. doi:10.4454/JPP.FA.2012.064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Elbeaino T, AbouKubaa R, Ismaeil F, Mando J, Digiaro M. Viruses and hop stunt viroid of fig trees in Syria. J Plant Pathol. 2012;94:687–91. [Google Scholar]

27. Delić D, Elbeaino T, Lolić B, Đurić G. Fig viruses in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Acta Hortic. 2021;1308(1308):319–24. doi:10.17660/ActaHortic.2021.1308.45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Elbeaino T, Nahdi S, Digiaro M, Alabdullah A, Martelli G. Detection of Fig leaf mottle-associated virus 1 and Fig leaf mottle associated virus 2 in the Mediterranean region and study on sequence variation of the hsp70 gene. J Plant Pathol. 2009;91:425–31. [Google Scholar]

29. IPPC. Phytosanitary measures for managing plant virus spread. Rome, Italy: FAO; 2020. [Google Scholar]

30. Elçi E, Serçe Ç.U, Çağlayan K. Phylogenetic analysis of partial sequences from Fig mosaic virus isolates in Turkey. Phytoparasitica. 2013;41(3):263–70. doi:10.1007/s12600-013-0286-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools