Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Ascorbic Acid Alleviates Salt Stress on the Physiology and Growth of Guava Seedlings

1 Center of Agrifood Science and Technology, Universidade Federal de Campina Grande, Pombal, 58840 000, PB, Brazil

2 Center of Technology and Natural Resources, Universidade Federal de Campina Grande, Campina Grande, 58429 900, PB, Brazil

3 Center of Human and Agricultural Sciences, Universidade Estadual da Paraíba, Catolé do Rocha, 58884 000, PB, Brazil

* Corresponding Author: Jackson Silva Nóbrega. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Crop Plants: Physio-biochemical and Molecular Mechanisms)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(5), 1587-1600. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.063633

Received 20 January 2025; Accepted 21 April 2025; Issue published 29 May 2025

Abstract

The Northeast region is the main producer of guava in Brazil, generating employment and income. However, water availability means that producer’s resort to using water with high salinity, which harms plant development, especially during the seedling formation phase. The adoption of techniques that mitigate the deleterious effect of salinity is increasingly necessary, such as the use of elicitors such as ascorbic acid. The purpose of this study was to analyze the morphophysiology of guava seedlings under saline and ascorbic acid levels. The study was carried out by applying treatments composed of five saline levels (SL = 0.3; 1.3; 2.3; 3.3 and 4.3 dS m−1) and four levels of ascorbic acid—AA (0, 200, 400, and 600 mg L−1), in a 5 × 4 factorial arrangement, adopting a randomized block design. Gas exchange and growth of guava seedlings are limited from 0.3 dS m−1. Using 400 mg L−1 of AA reduces damage from salinity on stomatal conductance, transpiration, and net assimilation rate up to the estimated SL of 1.80 dS m−1. In contrast, AA level 412 mg L−1 increased instantaneous water use efficiency up to the salinity of 2.3 dS m−1. AA level of 600 mg L−1 attenuated salt stress effects on leaf area and height/stem diameter ratio up to SL of 2.05 dS m−1. The number of leaves and the absolute and relative growth rates were stimulated by AA under the lowest saline level.Keywords

Guava is one of the most produced fruit crops in the Brazilian Northeast region, being a fruit consumed fresh and used in industry for the production of juices, sweets, jellies, and ice cream, among others. Brazil’s production in the 2023 season was 582,832 t, with the Northeast standing out as the greatest producer, accounting for 48.94% of all production [1].

Despite the importance of guava in the regional fruit-growing scenario, its production may become limited due to water scarcity, which induces farmers to make use of low-quality and high salinity in irrigation to meet the water needs of the crop [2]. This practice is commonly observed in irrigated areas of the Brazilian Northeast [3], where the salinization process is accelerated, posing significant risks of soil degradation [4].

The high salinity of the water can compromise several biochemical and morphophysiological processes, due to the reduction of osmotic potential, restricting the plant’s ability to absorb water and nutrients, ionic effect, which causes toxicity and imbalance of nutrients, and oxidative stress, caused by the production and accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which affects the integrity of membranes and leads to protein denaturation [5–7].

Plant tolerance to salinity depends on several aspects, such as the intensity and duration of exposure, the species/cultivar, and the stage of development. The seedling formation phase is one of the most vulnerable to salt stress, with germination and initial establishment being the phases most susceptible to the harmful effects of salinity [8]. Some authors studying the effects of salinity on guava crops have obtained different responses regarding their salinity tolerance. For instance, Ferreira et al. [9] observed that, during the seedling formation phase, guava cv. Paluma has a low tolerance, with a salinity threshold of 0.3 dS m−1.

Given this scenario, there emerges the need to adopt strategies that make it possible to reduce the damage caused by salinity on guava crops, including the application of eliciting compounds, such as ascorbic acid (AA) [10]. AA is a non-enzymatic compound that has antioxidant potential, involved in several physiological processes, such as the electron transport system, the xanthophyll and ascorbate-glutathione cycle, cell division and expansion, tocopherol regeneration, and biosynthesis of phytohormones [10,11]. AA also works by eliminating the excess of accumulated ROS, through the removal of various free radicals such as O2−, HO+, and H2O2, reducing the effects of oxidative stress, besides being a cofactor of enzymes that stimulate the plant’s antioxidant defense system, promoting greater tolerance to salinity [12,13].

From this perspective, the hypothesis of this study posits that ascorbic acid (AA) can alleviate the effects of saline stress in the seedling production phase. This is attributed to the physiological regulatory function of AA in the electron transport chain, where it acts as an alternative electron donor and enzyme activator. By doing so, AA helps sustain the flow of ATP and NADPH to the Calvin cycle, ensures proper stomatal activity, and maintains internal carbon flow, while also combating hydrogen peroxide accumulation linked to signaling pathways [11]. Consequently, this mechanism may enhance the activity of the RuBisCo enzyme in carbon assimilation, promoting plant growth and supporting ionic homeostasis under saline environments [14].

Thus, the purpose of this study was to analyze the morphophysiology of guava seedlings under saline and ascorbic acid levels in seedlings of cv. Paluma.

The experiment was conducted in a greenhouse belonging to the Academic Unit of Agricultural Sciences of the Federal University of Campina Grande (UFCG), Campus of Pombal, PB, Brazil. During the development of the study, the conditions of the protected environment presented a maximum temperature of 33.4°C, a minimum of 23.8°C and a relative humidity of 70.9%.

To carry out the study, a randomized block design was adopted, in a 5 × 4 factorial arrangement, representing to five saline levels (SL = 0.3, 1.3, 2.3, 3.3 and 4.3 dS m−1) and four levels of ascorbic acid (AA = 0, 200, 400 and 600 mg L−1) with four replicates. Saline levels were established according to Ferreira et al. [9], and AA levels were defined according to Gaafar et al. [13].

Guava seedlings cv. Paluma were obtained from seeds taken from fully ripe and healthy fruits, obtained from an orchard located at the Experimental Farm “Rolando Enrique Rivas” of CCTA/UFCG. The plants were grown in 2.0 dm3 polyethylene containers, with five seeds being sown and excess plants being thinned after emergence, leaving only the most vigorous one.

The bags were filled with Psamment with sandy loam texture, from the 0–20 cm deep layer and collected in the experimental area of the Experimental Farm, CCTA/UFCG, in São Domingos, PB. The soil underwent initial analyses, and its physical and chemical attributes were identified according to Teixeira et al. [15]. Attributes of the soil used in the experiment: pH = 6.01; OM = 0.21 g kg−1; P = 0.53 mg kg−1; K+ = 0.12 cmolc kg−1; Na+ = 0.05 cmolc kg−1; Ca2+ = 3.0; Mg2+ = 2.44 cmolc kg−1; Al3+ = 0.0 cmolc kg−1; H+ = 0.69 cmolc kg−1; ECse = 0.71 dS m−1; CEC = 6.25 cmolc kg−1; SARse = 0.61 mmol L−1; ESP = 0.80%; Particle-size fraction (g kg−1): Sand = 756.50; Silt = 200.10; Clay = 43.40.

Fertilization was based on the recommendation of Novais et al. [16], corresponding to 100, 150 and 300 mg kg−1 of soil of nitrogen (N), potassium (K2O) and phosphorus (P2O5). Fertilization began at 15 days after seedling emergence, split into three portions and applied by fertigation at 15-day intervals. Micronutrients were foliar applied with 1.0 g L−1.

The saline waters were obtained by dissolving NaCl in the water supply of the municipality of Pombal in the concentrations until reaching the levels used in the study, and the SL values were measured with the aid of a bench conductivity meter. For this purpose, the Richards methodology [17] was used to prepare the waters. Irrigation with saline waters began after the plants had 2 pairs of expanded leaves, and with volume based on water balance.

AA levels were obtained by diluting it in distilled water to the required concentrations. A drop of foliar adhesive (Tweem-80®, Cachoeirinha - RS, Brazil) was added to the solution in order to facilitate the fixation of AA on the leaves. AA application began 72 h before irrigation with saline water, via foliar, using a manual sprayer. During the research, AA was applied biweekly, applying an average value of 50 mL per plant.

At 110 days after sowing (DAS), gas exchanges were measured using a portable infrared gas analyzer (Infrared Gas Analyzer, model LCpro—SD), operating with a temperature control of 25°C. Readings were taken from 6:30 a.m. to 9:30 a.m., on fully expanded and photosynthetically active leaves of the middle third, at natural air temperature, with a CO2 concentration and an artificial light source of 1.200 μmol m−2 s−1.

The levels of photosynthetic pigments were determined during the same period. Small leaf spheres of 3.14 cm2 were obtained. placed in test tubes, acclimatized to the dark. Then, 5 mL of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was added to each sample, following the protocol described by Cruz et al. [18]. The tubes were kept in complete darkness for 48 h after collection. After this period, the extracts were transferred to quartz cuvettes and analyzed using a spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, model Genesys 20), with absorbance readings at wavelengths of 665, 649, and 480 nm. These measurements allowed for the quantification of chlorophyll a (Chl a), b (Chl b), and carotenoids (CAR), as well as total chlorophyll (Chl To), calculated as the sum of Chl a and Chl b, according to the methodology proposed by Wellburn [19].

Growth was evaluated at 110 DAS, through plant height (PH), number of leaves (NL), stem diameter (SD) and leaf area (LA). The PH was obtained by measuring from the base to the top of the plant, using a tape measure, with the results expressed in cm; NL was determined by counting fully formed leaves; SD was obtained using a digital caliper; and LA was obtained by means of leaf blade measurements and calculated according to Zucoloto et al. [20].

The absolute and relative growth rates of plant height (AGRPH and RGRPH) and stem diameter (AGRSD and RGRSD) were obtained considering the times of 20 and 130 DAS (t1 and t2, respectively) according to Benincasa [21].

The data obtained in this study were evaluated for normality using the Sharpiro-Wilk test and for homogeneity of variances using the Bartlett test. They were then subjected to analysis of variance at 5% probability level by the F test and, when there was a significant effect, polynomial regression was applied using the Sisvar statistical program [22]. To establish the correlation between the variables analyzed and the factors studied, a principal components analysis (PCA) was performed using the RStudio® program.

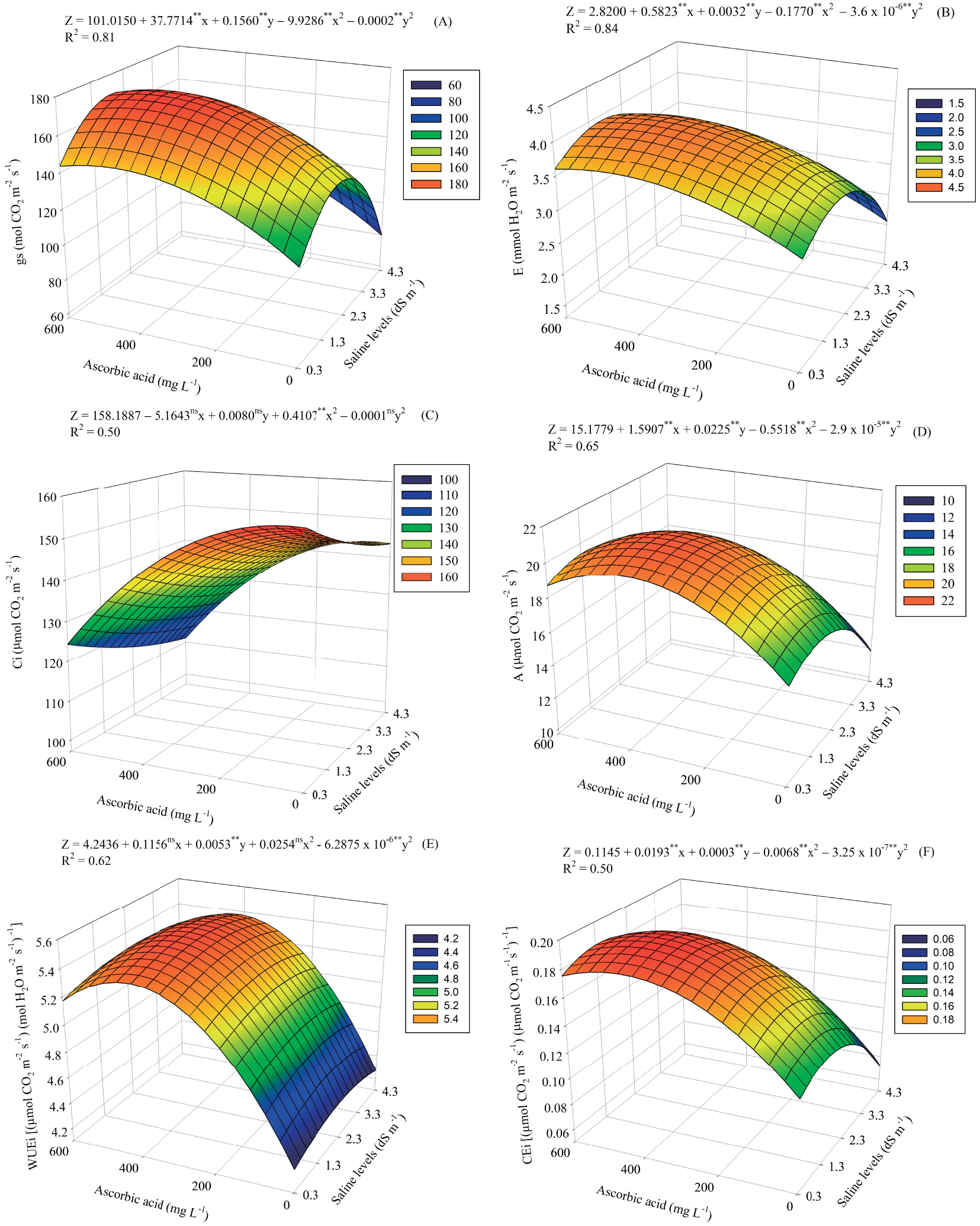

The interaction between saline and ascorbic acid levels (SL × AA) promoted a significant effect on gas exchanges of stomatal conductance (gs), transpiration (E), internal CO2 concentration (Ci), net CO2 assimilation rate (A), instantaneous water use efficiency (WUEi) and instantaneous carboxylation efficiency (CEi) of guava seedlings cv. Paluma.

Ascorbic acid attenuated the effects of salt stress on the gs of guava seedlings, the maximum estimated value being observed (172.37 mol CO2 m−2 s−1) obtained at SL of 1.8 dS m−1 and under AA level of 450 mg L−1 (Fig. 1A). The lowest value of gs (79.85 mol CO2 m−2 s−1) observed in the highest SL (4.3 dS m−1) and without application of AA.

Figure 1: Stomatal conductance—gs (A), transpiration—E (B), internal CO2 concentration—Ci (C), net CO2 assimilation rate—A (D), instantaneous water use efficiency—WUEi (E) and instantaneous carboxylation efficiency—CEi (F) of guava seedlings cultivated under saline levels (SL) and levels of ascorbic acid (AA). X and Y—Saline levels—SL and ascorbic acid levels—AA, respectively ** and *, significant (p ≤ 0.01 and p ≤ 0.05); ns—Not significant (p > 0.05) by the F test, respectively

E was higher (4.0066 mmol H2O m−2 s−1) in seedlings cultivated to salinity of 1.55 dS m−1 and under application of 450 mg L−1 of AA (Fig. 1B), followed by a decrease in E with increasing SL, and the lowest value (2.0518 mmol H2O m−2 s−1) was obtained at the saline level of 4.3 dS m−1 and without application of AA. This behavior is directly associated with the beneficial effect of AA on stomatal opening, since salt stress compromises gs, affecting plant transpiration.

Salt stress compromised the CO2 uptake by guava plants, (156.86 μmol CO2 m−2 s−1) in plants cultivated under the SL of 0.3 dS m−1 and under AA level of 37.5 mg L−1 (Fig. 1C). The increase to the SL of 4.3 dS m−1 provided decreases in Ci, with the lowest value (111.26 μmol CO2 m−2 s−1), observed in plants exposed the maximum level of AA (600 mg L−1).

The use of AA alleviated the damage caused by salinity on the A, with the highest value (20.68 μmol CO2 m−2 s−1) observed to SL of 1.55 dS m−1 and AA level of 375 mg L−1 (Fig. 1D). The lowest value of A (11.81 μmol CO2 m−2 s−1) occurred under saline level of 4.3 dS m−1 and without application of AA.

For the WUEi, foliar spraying of 412 mg L−1 of AA alleviated damage from salt stress, with the estimated maximum value (5.4768 [(μmol CO2 m−2 s−1) (mol H2O m−2 s−1)−1]) obtained under SL of 2.30 dS m−1 (Fig. 1E). The lowest value of WUEi (4.2720 [(μmol CO2 m−2 s−1) (mol H2O m−2 s−1)−1]) occurred to salinity of 4.3 dS m−1 and that did not receive AA.

The CEi was higher (0.1918 [(μmol CO2 m−2 s−1) (μmol CO2 m−2 s−1)−1]) under SL of 1.55 dS m−1 and AA level of 450 mg L−1 (Fig. 1F). The lowest value (0.0719 [(μmol CO2 m−2 s−1) (μmol CO2 m−2 s−1)−1] occurred in plants exposed to SL of 4.3 dS m−1 and without application of AA.

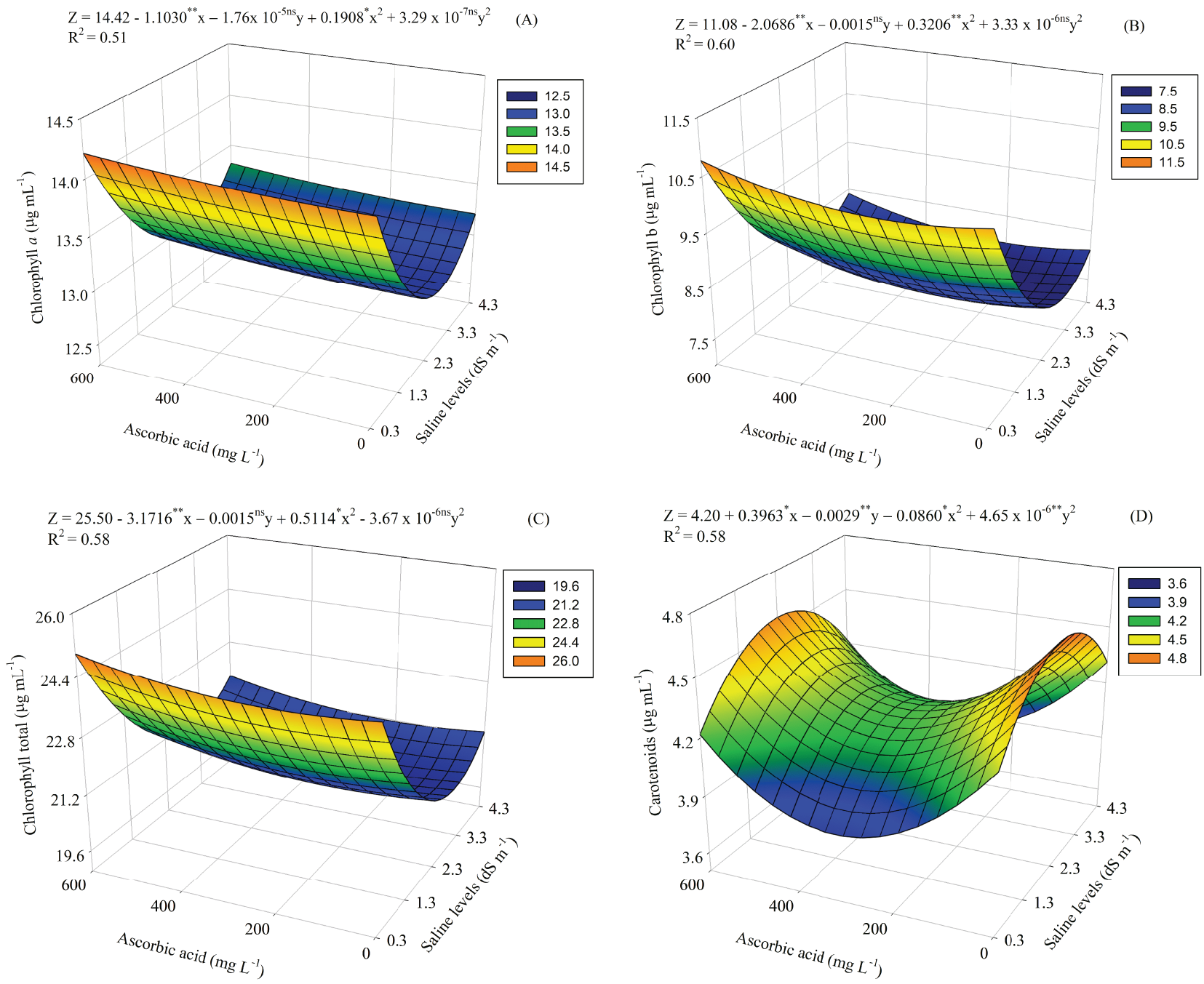

Similarly, to the gas exchange parameters, the interaction of factors (SL × AA) was observed for the levels of photosynthetic pigments in guava seedlings cv. Paluma at 110 DAS. The chlorophyll a content exhibited a negative relationship with increasing salinity (Fig. 2A), with the highest value observed in plants irrigated with an SL of 0.30 dS m−1 and treated with 600 mg L−1 AA (14.21 μg mL−1). In contrast, the lowest value occurred under SL of 2.8 dS m−1 and treated with 37.5 mg L−1 of AA (12.83 μg mL−1).

Figure 2: Chlorophyll a (A), chlorophyll b (B), chlorophyll total (C) and carotenoids (D) of guava seedlings as a function of the interaction between salinity levels (SL) and levels of ascorbic acid (AA). X and Y—Saline levels—SL and ascorbic acid levels—AA, respectively ** and *, significant (p ≤ 0.01 and p ≤ 0.05); ns—Not significant (p > 0.05) by the F test, respectively

For the chlorophyll b content (Fig. 2B), the highest value recorded was 10.77 μg mL−1 at the SL of 0.3 dS m−1 and at the level of 600 mg L−1 of AA, differing from the lowest value of 7.57 μg mL−1, observed at the SL of 3.3 dS m−1 and treated with the highest level of AA.

Foliar application of AA contributed to an increase in total chlorophyll content (Fig. 2C), with the highest value (24.99 μg mL−1) observed at a level of 600 mg L−1 and at the SL of 0.3 dS m−1. In contrast, the lowest value (20.42 μg mL−1) was recorded in plants irrigated with an SL of 3.05 dS m−1 and treated with 225 mg L−1 AA.

The lowest carotenoid content (3.84 μg mL−1) occurred in plants subjected to SL of 0.3 dS m−1 and 300 mg L−1 AA (Fig. 2D). On the other hand, the highest value (4.65 μg mL−1) was obtained in plants irrigated with a SL of 2.3 dS m−1 and without AA application.

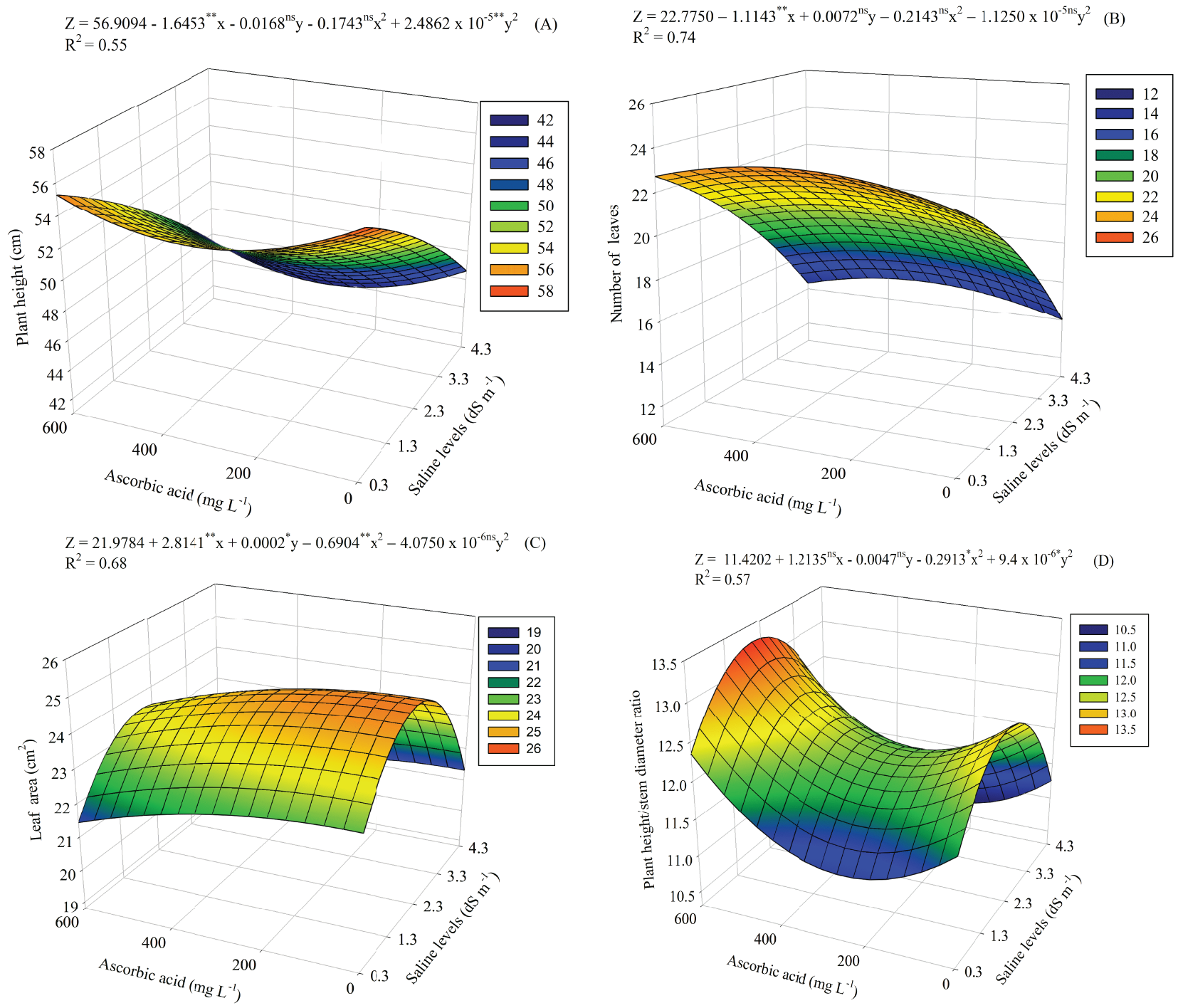

The interaction between saline levels and levels ascorbic acid (SL × AA) caused a significant effect (p ≤ 0.01) on the variables plant height (PH), number of leaves (NL), leaf area (LA) and plant height/stem diameter ratio (PH/SD). For stem diameter (SD), an individual effect of SL levels was observed at 110 DAS.

For plant height (Fig. 3A), the highest value (56.48 cm) occurred at the lowest SL (0.3 dS m−1) and without AA application. The increase in salinity inhibits height growth, with the lowest value (43.78 cm) observed at the SL of 4.3 dS m−1 and under an AA level of 337.5 mg L−1.

Figure 3: Plant height (A), number of leaves (B), leaf area (C) and plant height/stem diameter ratio (D) of guava seedlings as a function of the interaction between saline levels (SL) and levels of ascorbic acid (AA). X and Y—Saline levels—SL and ascorbic acid levels—AA, respectively ** and *, significant (p ≤ 0.01 and p ≤ 0.05); ns—Not significant (p > 0.05) by the F test, respectively

Foliar spraying of 375 mg L−1 of AA stimulated leaf production under SL of 0.3 dS m−1, with the highest value of 23.58 leaves (Fig. 3B). On the other hand, as water salinity increased, leaf production was reduced, with the lowest value (14.02 leaves) in plants cultived with SL of 4.3 dS m−1 and without of AA.

AA contributed to mitigating salt stress effects on leaf area (Fig. 3C), with the greatest increase (24.81 cm2) in plants under SL of 2.05 dS m−1 and exposed to AA level of 37.5 mg L−1. The smallest leaf area (19.98 cm2) was obtained when water salinity increased to 4.3 dS m−1 and AA level increased to the maximum level of 600 mg L−1.

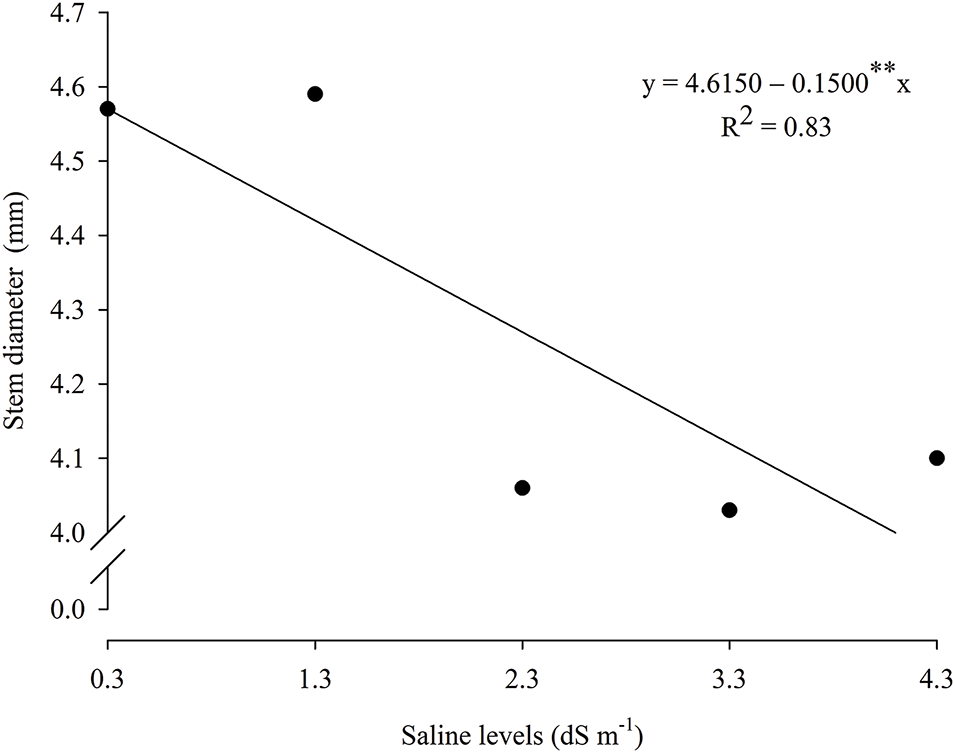

Plant height/stem diameter ratio (Fig. 3D) was higher (13.27) in plants exposed to salinity of 2.05 dS m−1 and foliar application of 600 mg L−1 of AA. In turn, the lowest value (10.68) was observed at the highest SL (4.3 dS m−1) and under AA level of 262.5 mg L−1. For the individual effect of saline levels on stem diameter (Fig. 4), the values were described by the linear regression model, with a decrease of 3.25% per unit increase of SL.

Figure 4: Stem diameter of guava seedlings cv. Paluma as a function of saline levels—SL. ** and *, significant (p ≤ 0.01 and p ≤ 0.05); ns—Not significant (p > 0.05) by the F test, respectively

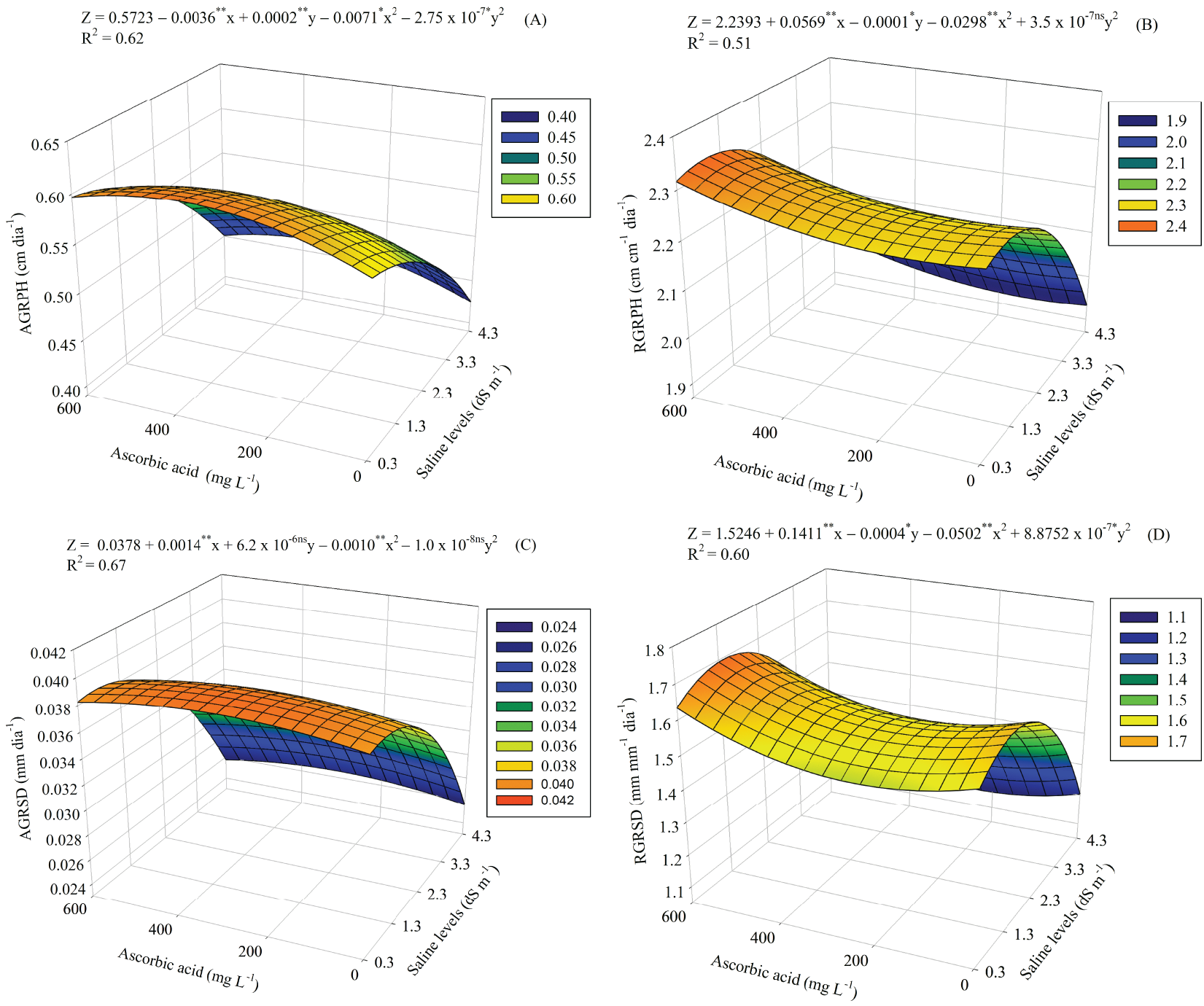

The interaction between saline levels and ascorbic acid levels (SL × AA) showed a significant effect (p ≤ 0.01), on the absolute and relative growth rates in plant height (AGRPH and RGRPH) and stem diameter (AGRSD and RGRSD) of guava seedlings cv. Paluma between 20 and 130 DAS.

For AGRPH (Fig. 5A), the largest increase (0.6102 cm day−1) occurred at SL of 0.3 dS m−1 and at the level of 375 mg L−1 of AA. While the smallest AGRPH (0.4245 cm day−1) was observed at SL of 4.3 dS m−1 and without AA.

Figure 5: Absolute and relative growth rates in plant height—AGRPH and RGRPH (A and B) and stem diameter—AGRSD and RGRSD (C and D) of guava seedlings cultivated under different saline levels (SL) and levels of ascorbic acid (AA). X and Y—Saline levels—SL and ascorbic acid levels—AA, respectively ** and *, significant (p ≤ 0.01 and p ≤ 0.05); ns—Not significant (p > 0.05) by the F test, respectively

The RGRPH (Fig. 5B) was 1.56 cm cm−1 day−1 higher in plants at SL of 0.3 dS m−1 and without AA (0.0 mg L−1). While the lowest (1.2907 cm cm−1 day−1) occurred at SL of 4.3 dS m−1 and at the level of 377.75 mg L−1 of AA, which resulted in a reduction of 17.3%.

The 375 mg L−1 AA level alleviated salinity-induced damage to AGRSD up to an estimated SL of 0.8 dS m−1, with a value of 0.0392 mm day−1 (Fig. 5C). Increasing salinity inhibited AGRSD, with the lowest value (0.0256 mm day−1) observed at a SL of 4.3 dS m−1 and without AA.

For RGRSD (Fig. 5D), the highest value (1.6946 mm mm−1 day−1) occurred at the SL of 1.3 dS m−1 and exposed to the level of 600 mg L−1 of AA. The increase in salinity resulted in a decrease in RGRSD, with the lowest value recorded being 1.1553 mm mm−1 day, reached at the SL of 4.3 dS m−1 and with the AA level at 225 mg L−1.

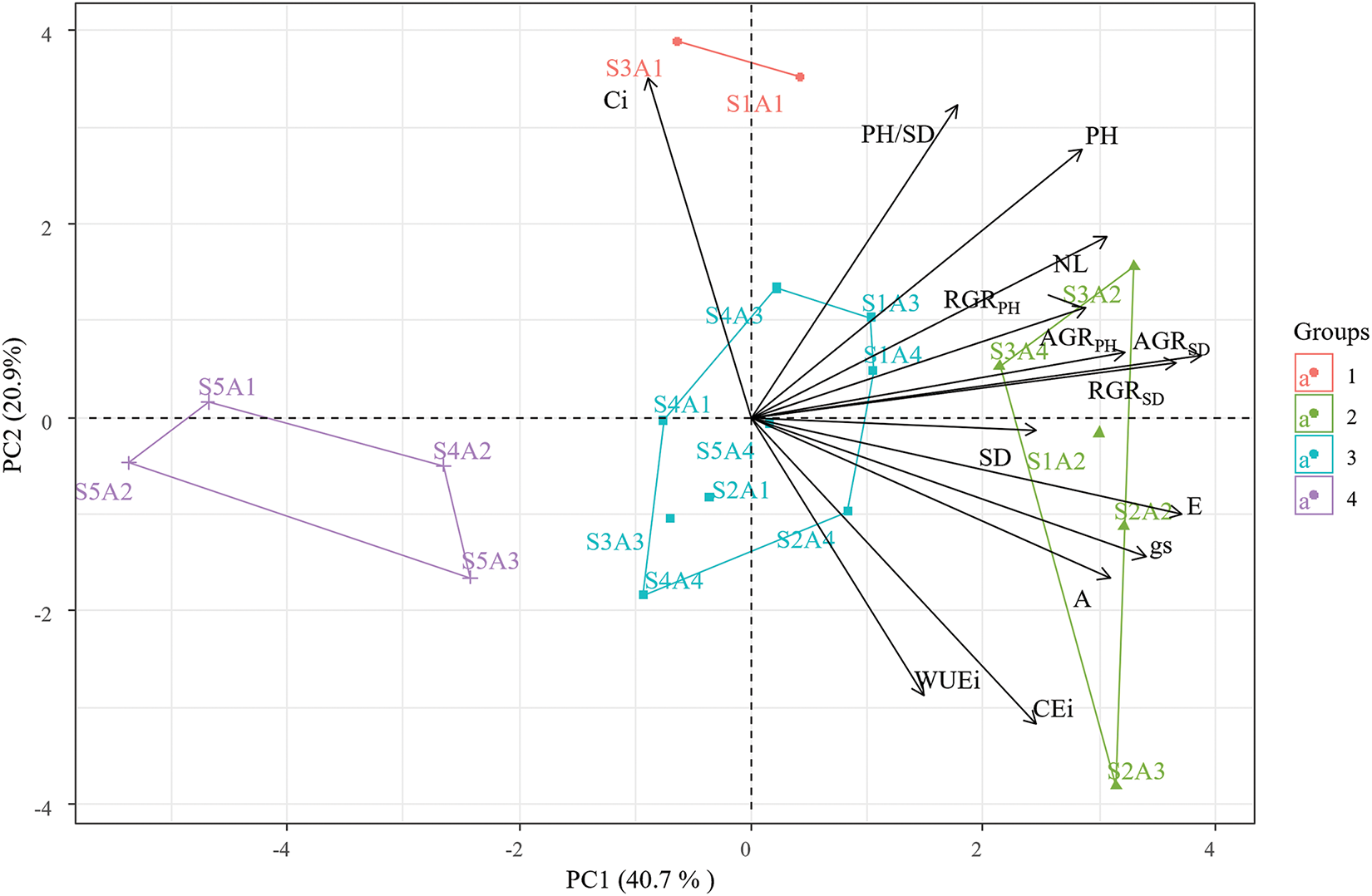

In the principal component analysis (Fig. 6), it is possible to verify that the correlation between the variables of gas exchange, photosynthetic pigments, growth and the treatments adopted indicates a totalvariability of 61% in the first two components, with PC1 accounting for 40.1% and PC2 for 20.9% of the variation in the data obtained.

Figure 6: Principal component analysis (PCA) of the correlation between gas exchange and growth variables of guava seedlings as a function of the interaction between the saline levels and levels of ascorbic acid

For PC1, a influence of groups 1, 2, 3, and 4 can be observed, particularly from group 2, which consists of S1A2, S2A2, and S3A2 (scores of 2.95, 3.37, and 3.00, respectively). These treatments showed a strong positive correlation with gas exchange and growth variables. In contrast, group 4, composed of treatments S5A1 and S5A2 (with respective scores of −3.61 and −5.63), exhibited an opposite behavior. Weakly, group 1 (S1A1, S1A3, S1A4, S2A4, S3A3, and S5A4) showed a positive correlation, while group 3 (S2A1, S3A1, S4A1, S4A2, S4A3, S4A4, and S5A3) exhibited a negative correlation with PC1 data.

Regarding PC2, a strong negative influence was observed from group 4, which includes treatments S2A3 and S3A4 (with scores of −2.03 and 3.56, respectively), on photosynthetic pigment levels. Conversely, these pigment levels were favored in treatments from group 1 (with scores of 1.64, 1.84, 1.08, 3.42, 1.30, 1.31, and 0.90, respectively).

Salinity impaired gas exchange in guava cv. Paluma, causing a decrease of more than 40% in gs and E, when plants were under SL of 4.3 dS m−1. This behavior is associated with osmotic and ionic damage caused by saline stress, which induces the closure of stomata, as a plant device to prevent water loss through transpiration [6]; as a consequence, there is a tendency for a reduction in net photosynthesis, as observed in this study.

It should be noted that in the study, application of up to 450 mg L−1 of AA increased the values of gs and E up to the estimated SL levels of 1.80 and 1.55 dS m−1, respectively, indicating the attenuating effect of AA on the deleterious effects arising from saline stress in guava seedlings. This is an indication that AA can act indirectly in the stomatal regulation of plants under stress conditions, as it activates the enzymatic activity of ascorbate peroxidase [14], which minimizes the accumulation of hydrogen peroxide, a molecule signaled by abscisic acid under stress conditions to induce guard cell closure [11]. Thus, foliar application of AA was able to keep the stomata open, even under conditions of water deficit imposed by the high salinity of the water, promoting the maintenance of transpiratory activity and the absorption and entry of carbon into the substomatal chambers [23].

The behavior observed in gs and E influenced the net CO2 assimilation rate, and the level of AA of 450 mg L−1 alleviates damage caused by salt stress up to SL of 1.55 dS m−1. This result indicates that, in addition to being associated with stomatal regulation of guava seedlings, AA promotes improvement in photosynthesis, due to its ability to act in the modulation and accumulation of compatible solutes, which act by eliminating ROS produced and accumulated as a result of salt stress, reducing the occurrence of oxidative stress and promoting improvements in ionic homeostasis and photoprotection of the plant [24].

The beneficial effect of AA in mitigating the effect of stress has been highlighted in other studies, such as Caetano et al. [25], who observed that foliar application of 0.8 mM in sour passion fruit attenuated the effect of salt stress on gas exchange up to SL of 3.8 dS m−1. El-Moukhtari et al. [24] found that foliar application of 1.0 mM AA alleviated the damage caused by salt stress on alfalfa plants. In passion fruit, de Fátima et al. [26] found up to 1.0 mM of AA was efficient to minimize the effects of water deficit, promoting improvements in gas exchange, especially in gs, transpiration and net assimilation rate. Parveen et al. [10] described similar improvements in wheat using 5.0 mM AA applied via priming, foliar application, and rooting, with all application methods resulting in increased levels of soluble sugars, proline, and glycine betaine, metabolites associated with the plant’s secondary defense mechanisms.

The stomatal limitation induced by salt stress affected WUEi, since it is a relationship between carbon assimilation and water loss, which indicates that plants maximized CO2 assimilation to the detriment of water use efficiency, controlling the opening and closing of stomata in order to prevent stress from causing damage to photosystems [27]. However, the application of AA resulted in an increase in WUEi up to 2.3 dS m−1, which indicates that AA was able to increase water absorption and use efficiency, hence influencing the net photosynthesis and transpiration of guava plants, due to the increase in leaf water potential, possibly resulting from its antioxidant activity and improvements in membrane stability [28].

The effect of water salinity was more pronounced on the Ci and CEi of guava plants, which showed reductions from SL of 0.3 dS m−1. Possibly, this behavior may be directly correlated with the activity of the enzyme ribulose−1, 5-bisphosphate carboxylase oxygenase (RuBisCO), which may have consumed the CO2 absorbed during the Calvin cycle, necessary for the beginning of the photorespiration process, resulting in the reduction of Ci, as found by Nobre et al. [29] in guava at 125 days after sowing.

It is worth noting that the decrease in chlorophyll content due to salinity is a frequently observed behavior, especially in the seedling production phase [30]. This reduction may be associated with the regulation of energy supply to the electron transport chain under stress, which, otherwise, could accelerate the production of ROS [28]. Furthermore, such losses have been associated with the activity of the enzyme chlorophyllase, which is involved in the degradation of chlorophyll a and, consequently, indirectly affects the synthesis of the chlorophyll b, as this pigment is synthesized from chlorophyll a through the activity of chlorophyll a oxygenase (CAO), which catalyzes the conversion of the methyl group of chlorophyll a into the formyl group [31]. Concurrently, the increase in carotenoid content supports the regulation of the photochemical phase of photosynthesis, as these pigments are associated with energy dissipation in the photosystems, preventing the excessive accumulation of energy and the production of ROS [32].

In the context of ascorbic acid (AA) application, it was observed that AA did not result in significant increases in chlorophyll content and, in some cases, even reduced carotenoid levels. This behavior reinforces the hypothesis that AA optimizes the photosystems, ensuring sufficient energy for the production of ATP and NADPH required for the Calvin cycle [11,33]. This effect may be attributed to the role of AA in activating alternative pathways to water photolysis, acting as an alternative electron donor and preventing ROS production [11,14]. Additionally, AA contributes to the synthesis of zeaxanthin, a pigment widely associated with protection against photoinhibition and photodestruction [12].

Saline stress also compromised the growth of guava seedlings, especially when cultivated with SL of 4.3 dS m−1. This effect caused by the higher salinity is linked to the reduction in water and nutrient absorption, caused by the reduction in the osmotic potential of the soil and ionic toxicity, which limit plant growth and development [33]. Likewise, it was found that water salinity provided decreases in growth rates in plant height and stem diameter, indicating the negative effects caused by salt stress, which compromises several morphophysiological processes, including cell division and expansion [34,35].

As demonstrated in the principal component analysis, enhancements in the photosynthetic process resulting from foliar application of AA were reflected in the growth parameters of guava seedlings. This reinforces the regulation of water flow and the control of salt uptake and accumulation by the plant, which can be attributed to the photochemical and metabolic protection promoted by AA [11]. These results support the use of concentrations ranging from 400 to 600 mg L−¹ as effective for alleviating salt stress, providing a basis for future studies, as these levels have frequently been reported as optimal for most crops [13,14].

The behavior induced by saline stress during the seedling phase can result in significant losses in plant development under field conditions, this phenomenon is often associated with the acclimation process to the environment, which requires rapid solute reallocation and modulation of hormonal activity and genetics [36]. Furthermore, the beneficial effects of ascorbic acid (AA) have shown potential to promote prolonged responses in plants, as evidenced by recent studies [14]. AA plays a role in hormonal balance, exhibiting synergy with growth regulators such as auxins and cytokinins, while antagonizing the effects of abscisic acid (ABA) [11,12]. However, further studies focusing on the development of guava plants during the post-saline stress period are needed to clarify these interactions and evaluate the efficacy of exogenous AA application at later stages. This approach may represent an economical and sustainable alternative for mitigating abiotic stresses in various species [13,27,29], and it can be combined with other elicitors to establish even more favorable responses [37,38].

Salinity impaired gas exchange and growth of guava cv. Paluma during the seedling formation phase, 110 days after sowing.

Foliar spraying with 400 mg L−1 ascorbic acid (AA) alleviated salinity-induced damage on gas exchange (gs, E and A) up to the estimated SL of 1.80 dS m−1, while AA concentration of 412 mg L−1 increased instantaneous water use efficiency up to the salinity of 2.3 dS m−1.

AA level of 600 mg L−1 reduces the detrimental effect of salinity stress up to 2.05 dS m−1 on leaf area growth and plant height/stem diameter ratio of guava plants. Leaf number and absolute and relative growth rates are stimulated by AA under low salinity conditions.

Acknowledgement: The Universidade Federal de Campina Grande for supporting the execution of this research.

Funding Statement: The research project was supported by CNPq (National Council for Scientific and TechnologicalDevelopment—Processo: 151057/2024-9), CAPES (Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel) financial code—001, and UFCG (Universidade Federal de Campina Grande).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Jackson Silva Nóbrega: conceptualization, methodology, writing—review and editing and funding acquisition; Geovani Soares de Lima: methodology, formal analysis, supervision and project administration; Jean Telvio Andrade Ferreira: software and investigation; Julio Cesar Agostinho da Silva: software and investigation; Lauriane Almeida dos Anjos Soares: formal analysis, supervision and visualization; Valéria Fernandes de Oliveira Sousa: software and formal analysis; Paulo Vinicius de Oliveira Freire: validation and investigation; Reynaldo Teodoro de Fátima: investigation, writing—original draft preparation and visualization; Flávia de Sousa Almeida: investigation and writing—original draft preparation; Hans Raj Gheyi: formal analysis and resources; Josemir Moura Maia: data curation and resources. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All of the data developed or examined during this investigation are available in this article, or they can be provided at reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. IBGE—Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Produção agrícola—lavoura (In Portuguese); 2024 Oct 29. [cited 2025 Apr 18]. Available from: https://cidades.ibge.gov.br/brasil/pesquisa/15/11954. [Google Scholar]

2. Palmate SS, Kumar S, Poulose T, Ganjegunte GK, Chaganti VN, Sheng Z. Comparing the effect of different irrigation water scenarios on arid region pecan orchard using a system dynamics approach. Agric Water Manag. 2022;265:107547. doi:10.1016/j.agwat.2022.107547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Dias NS, da Silva JF, Moreno-Pizani MA, Lima MCF, Ferreira JFS, Linhares ELR, et al. Environmental, agricultural, and socioeconomic impacts of salinization to family-based irrigated agriculture in the Brazilian semiarid region. In: Taleisnik E, Lavado RS, editors. Saline and alkaline soils in Latin America. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2020. p. 37–48. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-52592-7_2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Pessoa LGM, Freire MBGS, Green CHM, Miranda MFA, Filho JCA, Pessoa WRLS. Assessment of soil salinity status under different land-use conditions in the semiarid region of Northeastern Brazil. Ecol Indic. 2022;141:109139. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2022.109139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Wang J, Yuan J, Ren Q, Zhang B, Zhang J, Huang R, et al. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi enhanced salt tolerance of Gleditsia sinensis by modulating antioxidant activity, ion balance and P/N ratio. Plant Growth Regul. 2022;97(1):33–49. doi:10.1007/s10725-021-00792-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Peng Y, Zhu H, Wang Y, Kang J, Hu L, Li L, et al. Revisiting the role of light signaling in plant responses to salt stress. Hortic Res. 2024;12(1):uhae262. doi:10.1093/hr/uhae262. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. AbuQamar SF, El-Saadony MT, Saad AM, Desoky EM, Elrys AS, El-Mageed TAA, et al. Halotolerant plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria improve soil fertility and plant salinity tolerance for sustainable agriculture—a review. Plant Stress. 2024;12:100482. doi:10.1016/j.stress.2024.100482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Haddadi BS, Fang R, Girija A, Kattupalli D, Widdowson E, Beckmann M, et al. Metabolomics targets tissue-specific responses in alleviating the negative effects of salinity in tef (Eragrostis tef) during germination. Planta. 2023;258(3):67. doi:10.1007/s00425-023-04224-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Ferreira JTA, de Lima GS, da Silva SS, Soares LAA, de Fátima RT, Nóbrega JS, et al. Peróxido de hidrogênio na indução de tolerância de mudas de goiabeira ao estresse salino. Sem Ci Agr. 2023;44(2):739–54. doi:10.5433/1679-0359.2023v44n2p739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Parveen S, Arfan M, Wahid A. Exogenous applications of ascorbic acid improve wheat growth, physiology and yield under salinity stress via a balance in antioxidant production and ROS scavenging. New Zea J Crop Hortic Sci. 2024;2024:1–24. doi:10.1080/01140671.2024.2347534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Wu P, Li B, Liu Y, Bian Z, Xiong J, Wang Y, et al. Multiple physiological and biochemical functions of ascorbic acid in plant growth, development, and abiotic stress response. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(3):1832. doi:10.3390/ijms25031832. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Mishra S, Sharma A, Srivastava AK. Ascorbic acid: a metabolite switch for designing stress-smart crops. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2024;44(7):1350–66. doi:10.1080/07388551.2023.2286428. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Gaafar AA, Ali SI, El-Shawadfy MA, Salama ZA, Sekara A, Ulrichs C, et al. Ascorbic acid induces the increase of secondary metabolites, antioxidant activity, growth, and productivity of the common bean under water stress conditions. Plants. 2020;9(5):627. doi:10.3390/plants9050627. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Celi GEA, Gratão PL, Lanza MGDB, Reis ARD. Physiological and biochemical roles of ascorbic acid on mitigation of abiotic stresses in plants. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2023;202:107970. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2023.107970. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Teixeira PC, Donagemma GK, Fontana A, Teixeira WG. Manual de métodos de análise de solo. 3rd ed.Brasília, Brazil: Embrapa; 2017. 573 p. (In Portuguese). [Google Scholar]

16. Novais RF, Neves JCL, Barros NF. Ensaio em ambiente controlado. In: Oliveira AJ, editor. Métodos de pesquisa em fertilidade do solo. Brasília, Brazil: Embrapa-SEA; 1991. p. 189–253. (In Portuguese). [Google Scholar]

17. Richards LA. Physical condition of water in soil. In: Black CA, editor. Methods of soil analysis: part 1 physical and mineralogical properties, including statistics of measurement and sampling. Madison, WI, USA: American Society of Agronomy, Soil Science Society of America; 1965. p. 128–152. doi:10.2134/agronmonogr9.1.c8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Cruz ACF, Santos RP, Iarema L, Fernandes KRG, Kuki KN, Araújo RF, et al. Métodos comparativos na extração de pigmentos foliares de três híbridos de Bixa orellana L. Rev Bras Biociênc. 2007;5(Suppl. 2):777–9. (In Portuguese). [Google Scholar]

19. Wellburn AR. The spectral determination of chlorophylls a and b, as well as total carotenoids, using various solvents with spectrophotometers of different resolution. J Plant Physiol. 1994;144(3):307–13. doi:10.1016/S0176-1617(11)81192-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Zucoloto M, Santos JG, Bregonci IS, Almeida GD, Vicentini VB, Moraes WB, et al. Estimativa de área foliar de goiaba (Psidium guajava L.) por meio de dimensões lineares do limbo foliar. In: X Encontro Latino Americano de Iniciação Científica e VI Encontro Latino Americano de Pós-Graduação; 2006 Oct 19–20; São José dos Campos, Brazil. (In Portuguese). [Google Scholar]

21. Benincasa MMP. Análise de crescimento de plantas, noções básicas. 2nd ed.Jaboticabal, Brazil: FUNEP; 2003. 41 p. (In Portuguese). [Google Scholar]

22. Ferreira DF. Sisvar: a computer analysis system to fixed effects split plot type designs. Rev Bras Biom. 2019;37(4):529–35. doi:10.28951/rbb.v37i4.450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Azeem M, Sultana R, Mahmood A, Qasim M, Siddiqui ZS, Mumtaz S, et al. Ascorbic and salicylic acids vitalized growth, biochemical responses, antioxidant enzymes, photosynthetic efficiency, and ionic regulation to alleviate salinity stress in Sorghum bicolor. J Plant Growth Regul. 2023;42(8):5266–79. doi:10.1007/s00344-023-10907-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. El Moukhtari A, Lamsaadi N, Farissi M. Biostimulatory effects of ascorbic acid in improving plant growth, photosynthesis-related parameters and mitigating oxidative damage in alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) under salt stress condition. Biologia. 2024;79(8):2375–85. doi:10.1007/s11756-024-01704-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Caetano EJM, Silva AARD, Lima GS, Azevedo CAV, Veloso LLSA, Arruda TFL, et al. Application techniques and concentrations of ascorbic acid to reduce saline stress in passion fruit. Plants. 2024;13(19):2718. doi:10.3390/plants13192718. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. de Fatima RT, de Lima GS, Soares LAA, de Sá VKNO, Guedes MA, Ferreira JTA, et al. Effect of different timing of water deficit combined with foliar application of ascorbic acid on physiological variables of sour passion fruit. Arid Land Res Manag. 2025;39(2):237–61. doi:10.1080/15324982.2024.2387098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Xin L, Tang M, Zhang L, Huang W, Wang X, Gao Y. Effects of saline-fresh water rotation irrigation on photosynthetic characteristics and leaf ultrastructure of tomato plants in a greenhouse. Agric Water Manag. 2024;292(3):108671. doi:10.1016/j.agwat.2024.108671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Hassan A, Amjad SF, Saleem MH, Yasmin H, Imran M, Riaz M, et al. Foliar application of ascorbic acid enhances salinity stress tolerance in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) through modulation of morpho-physio-biochemical attributes, ions uptake, osmo-protectants and stress response genes expression. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2021;28(8):4276–90. doi:10.1016/j.sjbs.2021.03.045. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Nobre RG, Rodrigues-Filho RA, de Lima GS, da R Linhares EL, dos A Soares LA, Silva LA, et al. Gas exchange and photochemical efficiency of guava under saline water irrigation and nitrogen-potassium fertilization. Rev Bras Eng Agríc Ambient. 2023;27(5):429–37. doi:10.1590/1807-1929/agriambi.v27n5p429-437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. da Silva SS, de Lima GS, Ferreira JTA, Soares LADA, Gheyi HR, Nobre RG, et al. Formation of guava seedlings under salt stress and foliar application of hydrogen peroxide. Rev Bras Eng Agríc Ambient. 2024;28(2):e276236. doi:10.1590/1807-1929/agriambi.v28n2e276236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Li X, Zhang W, Niu D, Liu X. Effects of abiotic stress on chlorophyll metabolism. Plant Sci. 2024;342:112030. doi:10.1016/j.plantsci.2024.112030. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Zulfiqar S, Sharif S, Saeed M, Tahir A. Role of carotenoids in photosynthesis. In: Zia-Ul-Haq M, Dewanjee S, Riaz M, editors. Carotenoids: structure and function in the human body. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2021. p. 147–87. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-46459-2_5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Saleem N, Noreen S, Akhter MS, Alshaharni MO, Athar HUR, Alzuaibr FM, et al. Ascorbic acid-mediated enhancement of antioxidants and photosynthetic efficiency: a strategy for enhancing canola yield under salt stress. S Afr J Bot. 2024;173:196–207. doi:10.1016/j.sajb.2024.08.018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Ibrahimova U, Talai J, Hasan MM, Huseynova I, Raja V, Rastogi A, et al. Dissecting the osmotic and oxidative stress responses in salt-tolerant and salt-sensitive wheat genotypes under saline conditions. Plant Soil Environ. 2025;71(1):36–47. doi:10.17221/459/2024-PSE. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Thabet SG, Safhi FA, Börner A, Alqudah AM. Genetic insights into intergenerational stress memory and salt tolerance mediated by antioxidant responses in wheat. J Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 2025;25(1):843–57. doi:10.1007/s42729-024-02170-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Yu Z, Duan X, Luo L, Dai S, Ding Z, Xia G. How plant hormones mediate salt stress responses. Trends Plant Sci. 2020;25(11):1117–30. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2020.06.008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Basit F, Abbas S, Zhu M, Tanwir K, El-Keblawy A, Sheteiwy MS, et al. Ascorbic acid and selenium nanoparticles synergistically interplay in chromium stress mitigation in rice seedlings by regulating oxidative stress indicators and antioxidant defense mechanism. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2023;30(57):120044–62. doi:10.1007/s11356-023-30625-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. El-Beltagi HS, Mohamed HI, Sofy MR. Role of ascorbic acid, glutathione and proline applied as singly or in sequence combination in improving chickpea plant through physiological change and antioxidant defense under different levels of irrigation intervals. Molecules. 2020;25(7):1702. doi:10.3390/molecules25071702. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools