Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Systematic Review of Machine Learning Applications in Sustainable Agriculture: Insights on Soil Health and Crop Improvement

1 Academy of Biology and Biotechnology, Southern Federal University, Rostov-On-Don, 344090, Russia

2 Department of Geography, Shaheed Bhagat Singh College, University of Delhi, New Delhi, 110017, India

3 Department of Environment Science, Graphic Era Hill University, Bharu Wala Grant, 248002, India

* Corresponding Authors: Vishnu D. Rajput. Email: ,

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Integrated Nutrient Management in Cereal Crops)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(5), 1339-1365. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.063927

Received 29 January 2025; Accepted 16 April 2025; Issue published 29 May 2025

Abstract

The digital revolution in agriculture has introduced data-driven decision-making, where artificial intelligence, especially machine learning (ML), helps analyze large and varied data sources to improve soil quality and crop growth indices. Thus, a thorough evaluation of scientific publications from 2007 to 2024 was conducted via the Scopus and Web of Science databases with the PRISMA guidelines to determine the realistic role of ML in soil health and crop improvement under the SDGs. In addition, the present review focused to identify and analyze the trends, challenges, and opportunities associated with the successful implementation of ML in agriculture. The assessment of various databases clearly revealed that ML implementation depends on crop management, while its limited potential in terms of soil health was explored. ML models, such as random forest and XGBoost, have demonstrated high accuracies of up to 99% in crop yield prediction and disease detection. Advanced ML frameworks, including the SHIDS-ADLT and EfficientNetB3, have improved soil health monitoring and plant disease classification. Irrigation management using ML has achieved over 50% water savings and irrigation efficiency by 10%–35%. These findings highlight the potential of ML to improve sustainable agricultural practices and soil health. A significant improvement discussed in this review is AutoML, which simplifies ML model implementation by automating feature selection, model selection, and hyperparameter tuning, reducing dependency on ML expertise. The integration of ML with remote sensing, Internet of Things (IoT), and big data analytics is expected to further transform the precision agriculture and real-time decision-making approaches to optimize resource utilization. Conclusively, the present review offers a quantitative perspective on the evolution of ML in agriculture, soil health management, crop yield prediction, and resource optimization.Keywords

Modern agriculture needs to address various issues, such as climate change, natural resource depletion, adjustment of dietary preferences, safety and health, and food security, due to the expansion of the population [1]. The continuous rise of the global population, which is predicted to reach approx. 9.8 billion by 2050, has forced an urgent need to reach equilibrium between the demand and supply of food [2]. The estimated demand for cereals, including both human food and animal feed, is expected to increase to almost 3 billion tonnes by 2050, compared with the current volume of approx. 2.1 billion tonnes [3,4]. As an approach to resolving these challenges and imposing pressure on the agricultural sector, there is an urgent need to maximize the efficiency of agricultural practices while simultaneously lowering the environmental burden [5].

Modern agricultural practices generate data through a range of sensors that allow for a better understanding of both the operation (machinery data) and operational environment (dynamic crop, soil, and weather conditions) to improve the decision-making process for efficient outcome [6]. The integration of machine learning (ML) algorithms in digital agriculture has revolutionized crop management and resource allocation [7,8], which is particularly valuable in the face of challenges such as climate change, population growth, and resource scarcity, as it enables farmers to make more informed decisions and adapt to changing conditions in real time.

Predictive analytics help farmers anticipate crop disease management, optimize irrigation schedules, predict market trends, and increase efficiency and productivity. The efficient use of ML minimizes the waste and reduce the reliance on harmful chemicals [9]. With the increasing availability of data and computing power, the applications of ML are expected to grow and further transform the agricultural sector [10], and becoming an increasingly essential tool for modern cultivation, offering new opportunities for innovation and sustainability [11]. However, knowledge of ML approaches in sustainable agriculture, both retrospectively and prospectively, is essential for gaining insights into current state-of-the-art practices and prospects in this field.

According to recent literature analysis for the period from 2004 to 2018, four generic types (crops, water, soil, and livestock management) were discovered [12]. Crop management accounted approx. 61% of all the articles and comprised the bulk of the articles across all the categories. It was further segmented into [12] yield prediction, crop disease prediction, weed detection, crop recognition, and crop health monitoring. While numerous aspects of ML applications in agriculture, a comprehensive overview focusing on the categorization and synthesis of this information is needed [12]. Over the years, research has delved into diverse aspects, such as (i) the application of ML algorithms for crop yield prediction [13,14] (ii) the use of remote sensing data and image analysis for precision agriculture [15,16], (iii) the development of decision support systems for pest and disease management [17,18], and (iv) the optimization of resource management practices through data-driven approaches [19,20].

Considering the significance of ML in agriculture and soil health management, the present review systematically evaluates research published over the last seventeen years, highlighting the transformative potential of ML in these domains. Despite significant advancements, including the application of models such as random forest and light gradient boosting machines for soil health assessment and systems such as the SHIDS-ADLT for nutrient deficiency analysis, compact and integrated information on the classification, and the use of ML in agriculture remains scarce. Thus, this systematic review aims to answer key questions regarding ML applications in sustainable agriculture by of scientometric and systematic review methodologies. Specifically, how ML contributes to enhance soil health monitoring and management, and what are the current trends, challenges, and the possibilities of ML-based methodologies for improving agricultural productivity? The possibilities are explored on the integration of ML with IoT, remote sensing, and big data analytics for improving adaptive farming practices. This review also identified the gaps in existing ML models and highlights promising techniques such as AutoML, spatiotemporal analysis, and deep learning frameworks. The latest technologies, including ensemble models, real-time nutrient monitoring systems, and advanced ML techniques such as EfficientNetB3 and ResNet50 for crop health and disease detection, were discussed and their potential was explored. This systematic review underscores the role of ML in optimizing soil and crop management practices, such as using spatiotemporal frameworks to map dynamic soil properties, provide fertilizer recommendations, and enhance crop yield predictions with high accuracy level (exceeding 99%).

2 Significance of Machine Learning in Agriculture and Soil Health Management: A Bibliometric and Scientometric Evaluation

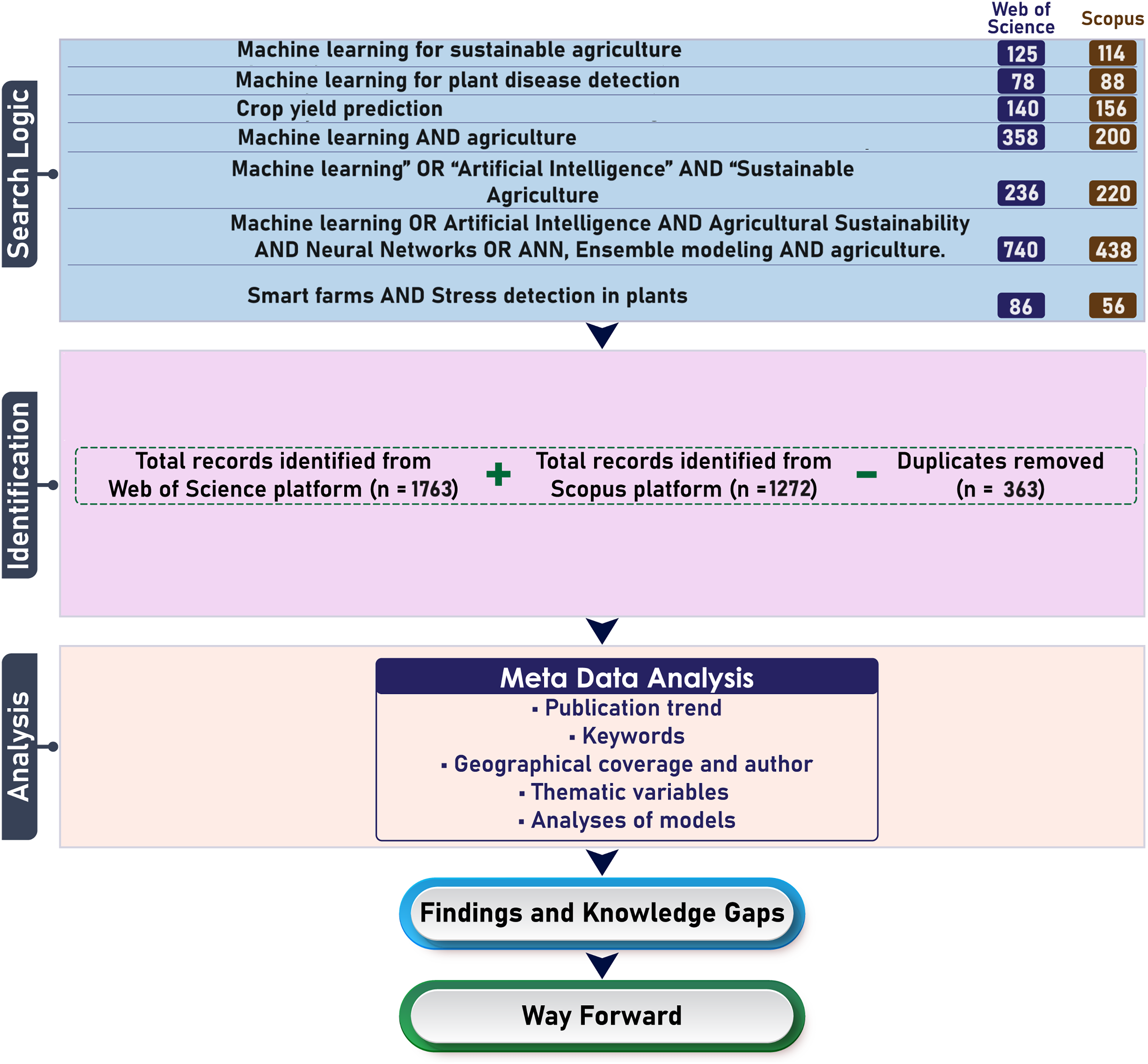

The PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis) approach was utilized to identify papers, following its four-stage process, i.e., identification, assessment, eligibility, and inclusion (Fig. 1) [21].

Figure 1: Methodological framework outlining the research process using the PRISMA method

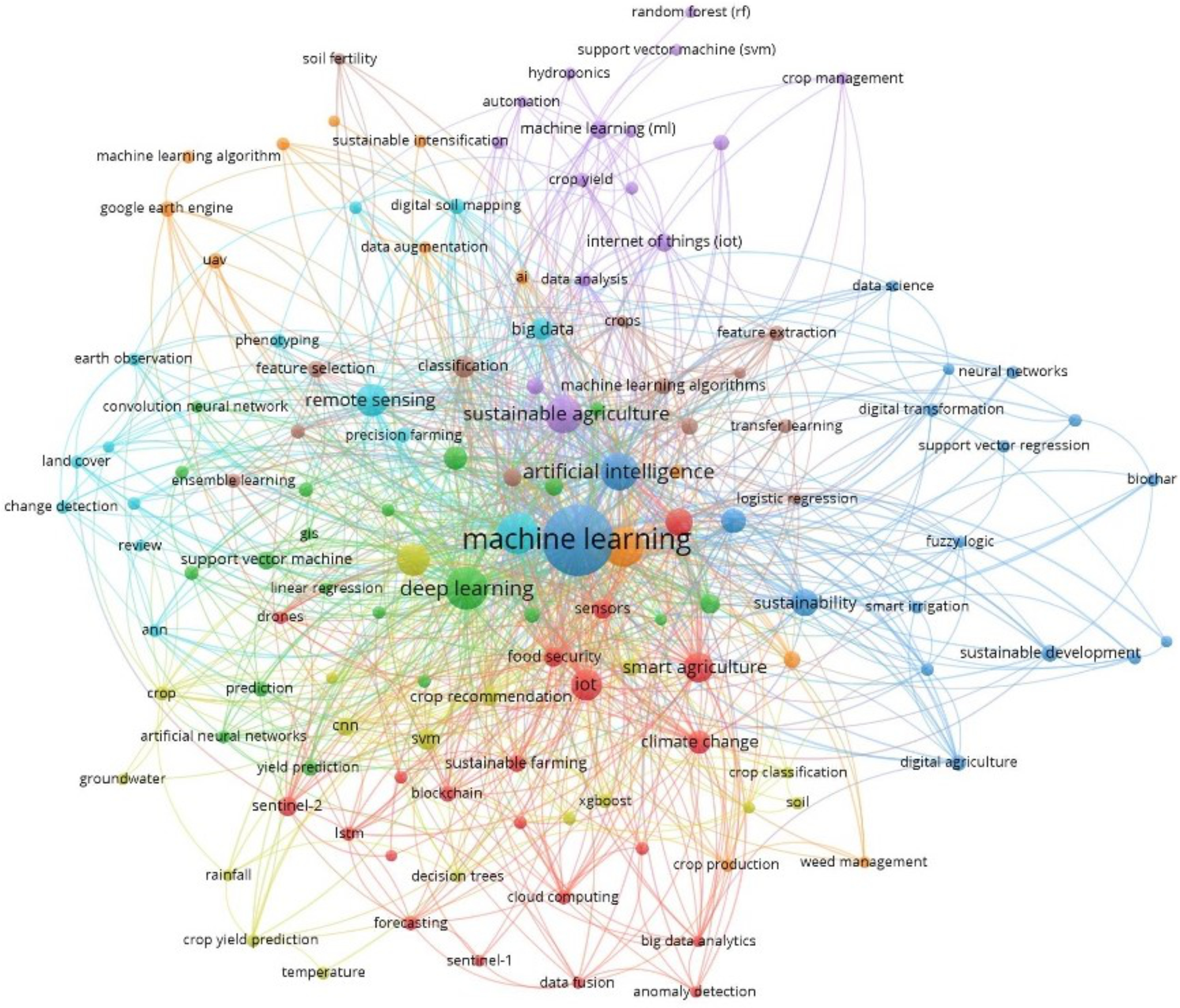

The keyword co-occurrence analysis was performed using VOSviewer (version 1.6.20), a software tool for constructing and visualizing bibliometric networks. Keywords with a minimum occurrence threshold of 10 were selected to ensure relevance, and the full counting method was applied for normalization. The clustering algorithm grouped keywords into thematic clusters based on association strength, with a resolution parameter set to 1.0. Repetitive or redundant terms (e.g., ‘ML’ and ‘Machine Learning’) were merged to avoid fragmentation. Additionally, the network visualization was optimized using the LinLog modularity algorithm, which emphasizes the strength of connections between keywords. A total of 8307 keywords were identified from the Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus databases after deleting repetitive keywords (Fig. 2). The most prevalent term is “Machine Learning”, with 965 counts, followed by “Deep Learning” (191 counts), “Learning Systems” (182 counts), “Learning Algorithms” (146 counts), and “Decision Trees” (102 counts). This analysis highlights the significant focus on applying ML methods in agricultural research. Keywords such as “Agriculture” (351 counts), “Crops” (228 counts), “Precision Agriculture” (143 counts), “Farms” (106 counts), “Crop Yield” (63 counts), and “Crop Production” (44 counts) emphasize diverse agricultural methods and crop management. On the other hand, keywords such as “Sustainable Development” (240 counts), “Sustainable Agriculture” (163 counts), “Sustainability” (69 counts), and “Sustainable Farming” (21 counts) examine the relevance of sustainable practices in agricultural research. Keywords related to “Artificial Intelligence” (156 counts), “Internet of Things” (131 counts), “Agricultural Robots” (129 counts), “Remote Sensing” (141 counts), and “Satellite Imagery” (42 counts) indicate the integration of advanced technologies in agriculture for monitoring, data collection, and decision-making. Keywords such as “climate change” (95 counts), “soil” (93 counts), “water management” (53 counts), “ecosystems” (29 counts), and “environmental monitoring” (26 counts) emphasize addressing environmental concerns and increasing conservation efforts in agriculture. Keywords such as “big data” (38 counts), “data analytics” (25 counts), “data mining” (22 counts), “feature extraction” (24 counts), and “principal component analysis” (19 counts) focus considerably on data-driven techniques and statistical analysis in agricultural research.

Figure 2: Word co-occurrence network of machine learning approaches in sustainable agriculture

While the bibliometric analysis provided a quantitative overview of ML trends in agriculture, several limitations arose during the process. Scopus and WoS databases may have excluded the regional studies published in non-indexed journals, particularly from developing nations. The rapid advancement of ML research results in a temporal gap between data collection and publication. Inconsistencies in terminology, such as conflating soil fertility (nutrient availability) with soil health (holistic ecosystem functionality), complicated the knowledge synthesis. The predominance of crop management studies (61% of analyzed publications) introduced a thematic bias, underscoring the need for future reviews to address underrepresented areas such as livestock integration, agroforestry systems, and socio-economic impacts of ML adoption.

This meta-data analysis highlights the interdisciplinary nature of research on ML for sustainable agriculture, which integrates technical innovation, environmental concerns, and data-driven decision-making to solve global issues related to food security and environmental sustainability. A total of 2718 articles were downloaded from WoS (1534) and Scopus (1184). A variety of keywords are used as selection criteria for the literature survey. It includes “machine learning for sustainable agriculture”, “machine learning”, “agriculture”, “crop disease detection”, “plant diseases”, “machine learning for plant disease detection”, “crop yield prediction”, “smart farms”, “stress detection in plants”, “machine learning” OR “artificial intelligence” AND “sustainable agriculture” OR “agricultural sustainability” AND “neural networks” OR “ANN”, “ensemble modeling” AND “agriculture”. These keywords help narrow the search results to articles that specifically address the application of ML in sustainable agriculture via Boolean operators. The use of these databases and keywords allows a more focused and efficient search process.

This targeted approach ensures that the articles retrieved are highly relevant to the subject of the current study. Several relevant articles that emphasize the significant and unique attributes of established ML models in sustainable agriculture are included in this review. There was a significant increase in the number of paper publications related to smart farming, showing exponential growth. A significant number of publications are articles (1345), showing the importance of original research. The 180 review papers focus on previous research findings were considered. Early access publications (37) signify access to works before official publication, promoting the rapid distribution of research results. Editorial materials (6) involve comments or opinion articles by journal editors, adding to intellectual conversation. Data paper (4) highlights the necessity of sharing datasets for repeatability and subsequent study. Proceeding papers (3) report outcomes from conferences or symposiums. Book chapters (1) show contributions to edited volumes, whereas letters (1) and news pieces (1) give short exchanges or updates within the academic community. Thus, the WoS datasets explore the growth of the heterogeneous characteristics of publications on ML in sustainable agriculture.

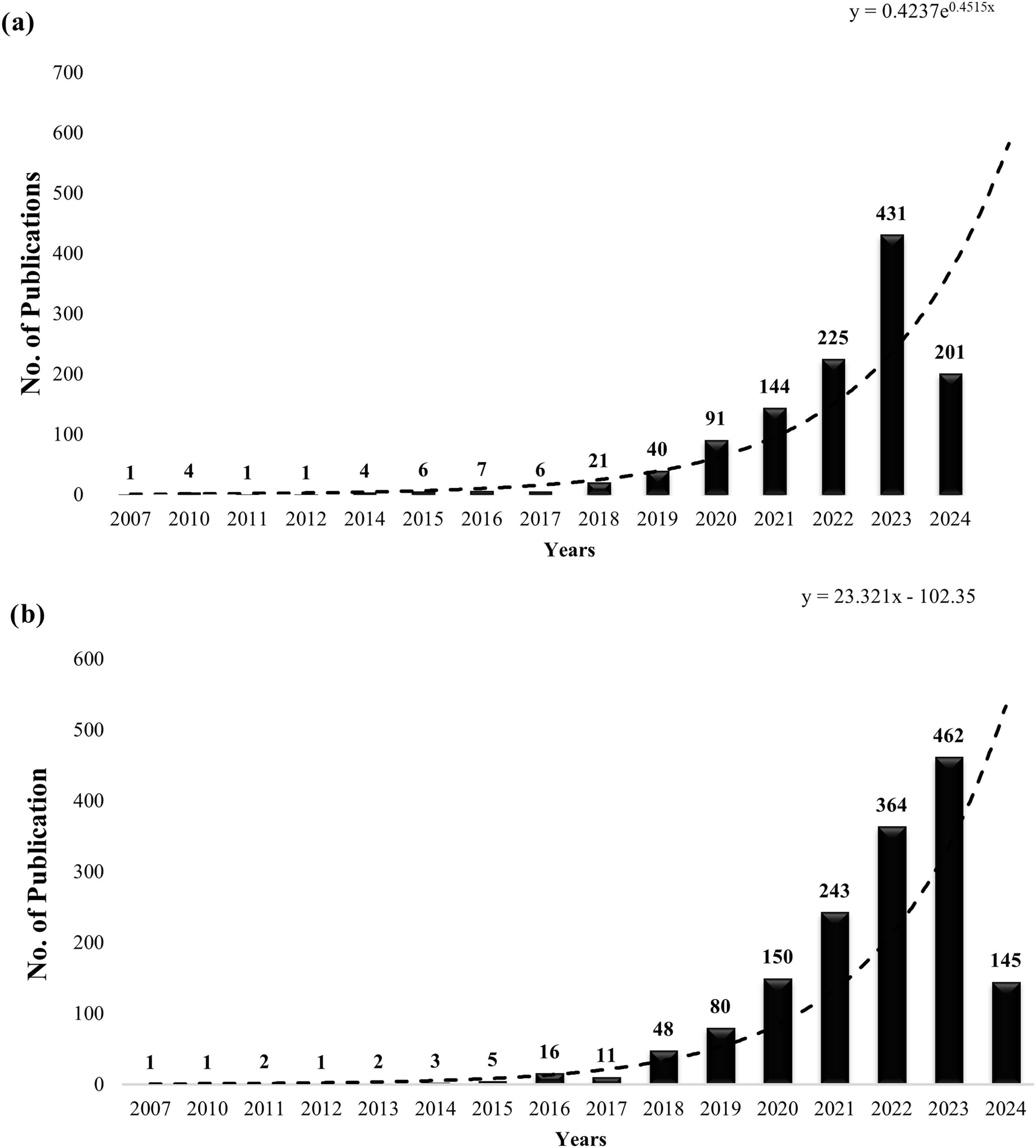

An in-depth examination of academic papers addressing the interface of ML and sustainable farming practices on the Scopus platform was conducted. During the initial phase (2007 to 2010), there was a limited number of publications, with only one publication in 2007 and a gradual increase to four publications in 2010. This shows a period of early exploration and limited involvement in the use of ML to promote agricultural sustainability. There was an evident change in the pattern of publications from 2011 to 2014 (Fig. 3). In 2011, 2012, and 2013, there was only one publication each year. However, in 2014, the number of publications increased in specific domains related to crop categorization, disease detection, and yield prediction.

Figure 3: Temporal trends of published articles in Scopus (a); Web of Science (b)

The publication trend of the WoS database on “Machine Learning for Sustainable Agriculture” shows a consistent upward trend from 2007 to 2015. The number of publications progressively increased, with an average of 1 to 5 articles annually. However, in 2016, there was an upsurge in the publishing trend. The number of publications increased from 16 in 2016 to 462 in 2023, demonstrating an exceptional development trend. The year 2018 represents a turning point with 48 articles, which then doubled in 2019 (Fig. 3) and continues to expand rapidly thereafter. The peak was achieved in 2023, with 462 publications, indicating considerable interest in ML. Even with 5 months of data for 2024, 145 publications show continual interest in the domain of ML in sustainable agriculture. This trend has led to considerable gains in research on ML for sustainable agriculture. The number of publications on ML for sustainable agriculture areas has shown a significant upward trend due to the growing interest in sustainable agriculture practices using ML.

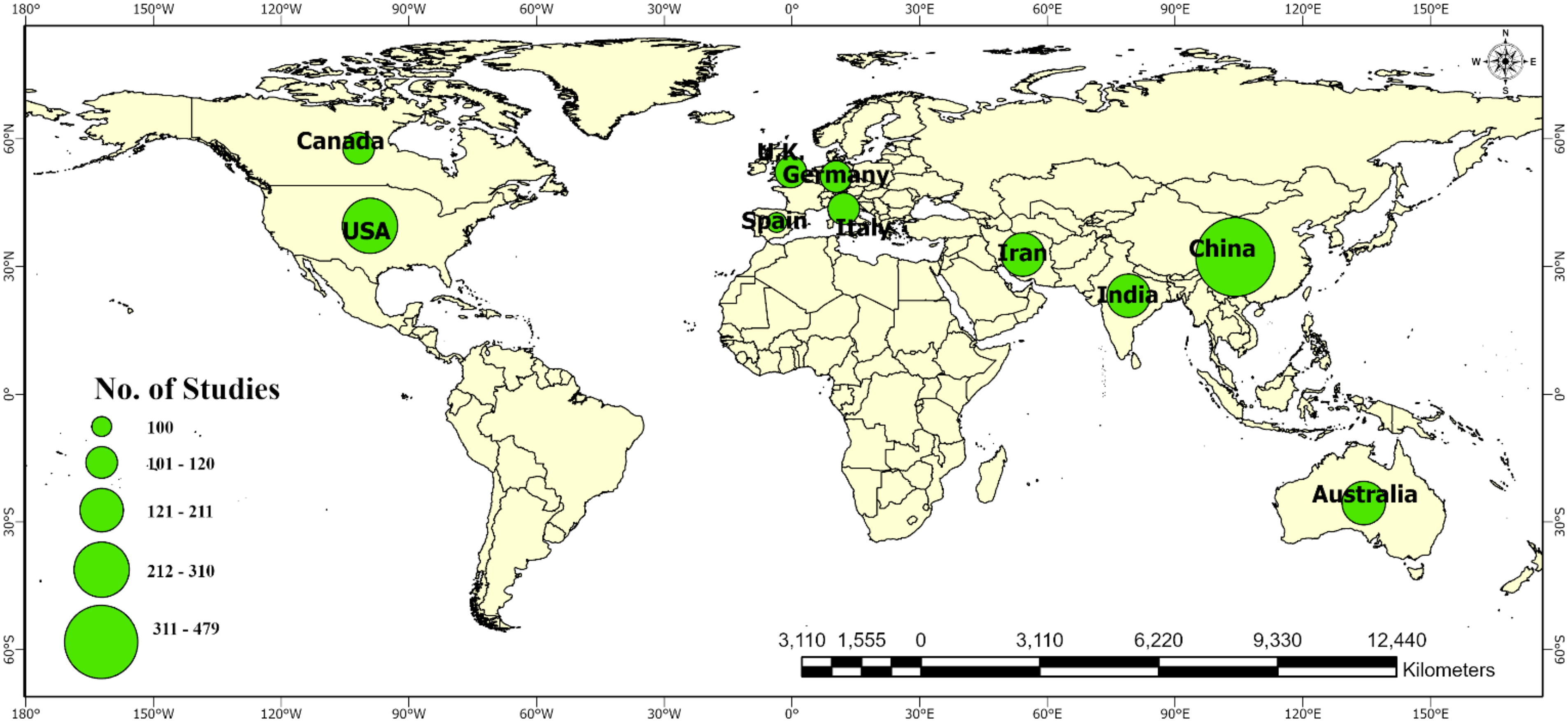

The geographical distribution of publications was examined to determine the spatial pattern of ML applications for sustainable agriculture. Among the 1534 total articles (Fig. A1), the highest number of articles were recorded in the People’s Republic of China (479 articles), followed by 310 articles from the USA, 211 articles from India, 174 articles from Iran, 155 articles from Australia, 120 articles from Germany, 118 articles from Italy, 116 articles from Canada, 111 articles from England and 100 articles from Spain. The significance of agriculture has attracted major research interest and investment to create sustainable techniques to increase productivity, efficiency, and resilience.

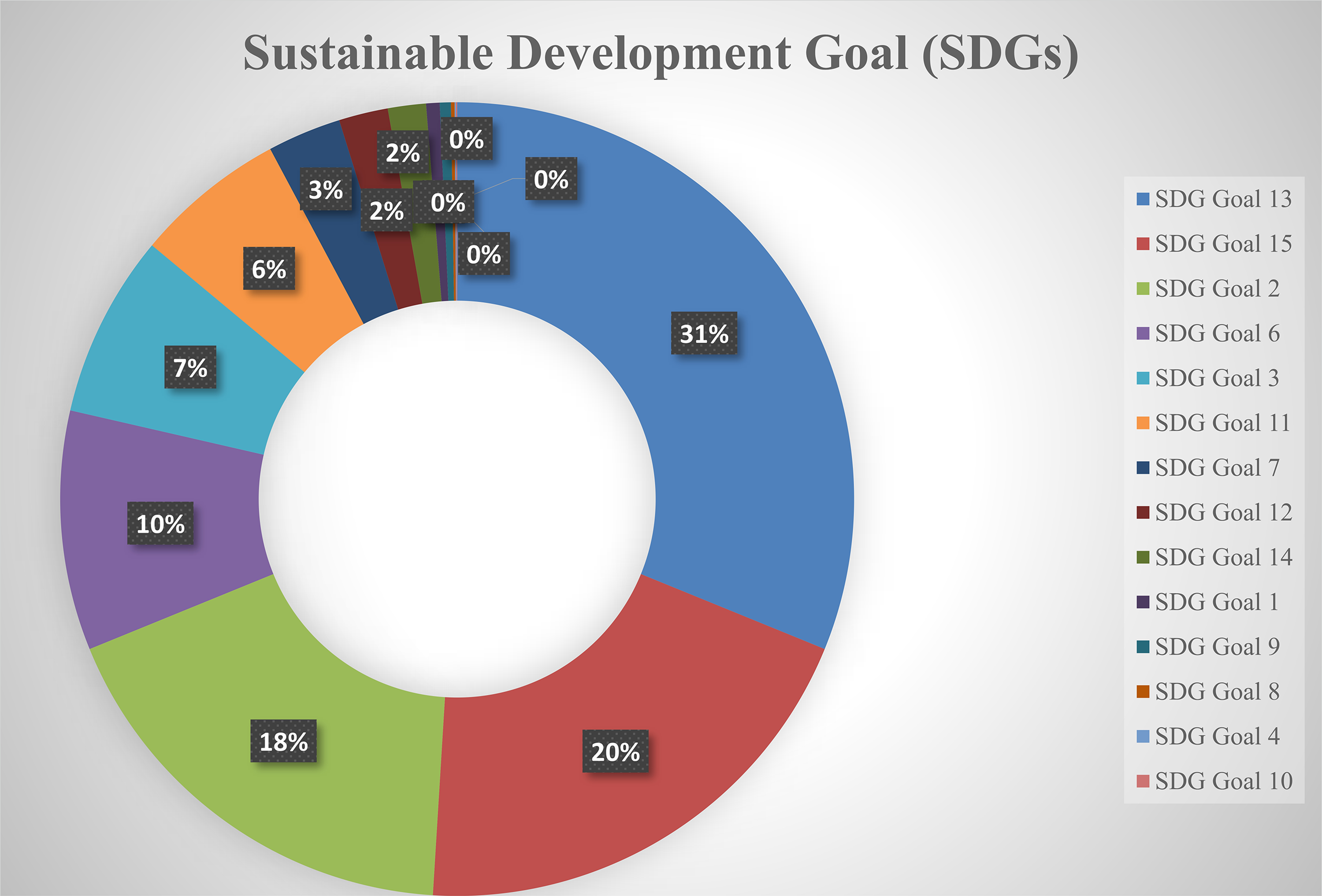

The majority of the articles pertained to the SDG 13 (climate action) goal, with significant emphasis on applying ML to address climate-related concerns in agriculture. This is followed by SDG 2 (Zero Hunger) and SDG 15 (Life on Land) goals, which explore to protect terrestrial ecosystems and biodiversity and improve food security via ML applications. Sustainable urban development (SDG 11), health outcomes (SDG 3), water management (SDG 6), and energy efficiency (SDG 7) are other SDGs that are of interest to researchers. However, several SDGs, such as SDG 1 (no poverty) and SDG 10 (reduced inequality), have fewer publications, indicate potential topics for additional investigation (Fig. 4). The analysis focuses on the various applications of ML to address sustainability challenges across different agricultural systems, highlight the interdisciplinary nature of research in this domain and the imperative of employing technology for sustainable development.

Figure 4: Distribution of research focus across various sustainable development goals in machine learning approaches to sustainable agriculture

ML applications align with specific SDG targets, demonstrate their potential to address global challenges. The “Zero Hunger” goal (SDG 2 is supported by current studies on ML-driven crop yield prediction models, such as Random Forest algorithms, which have achieved up to 99% accuracy to optimize the food production and address its security. Similarly, SDG 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation) benefits from ML-based irrigation management systems that reduce water waste by up to 50%, promoting efficient resource use. In the context of SDG 13 (Climate Action), ML models analyze soil-climate relationships, such as spatiotemporal frameworks, enable adaptive farming practices to mitigate climate impacts. These linkages underscore ML’s critical role in achieving the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, to address the challenges of food security, resource management, and environmental sustainability.

3 Insights into Machine Learning in Agriculture and Soil Health

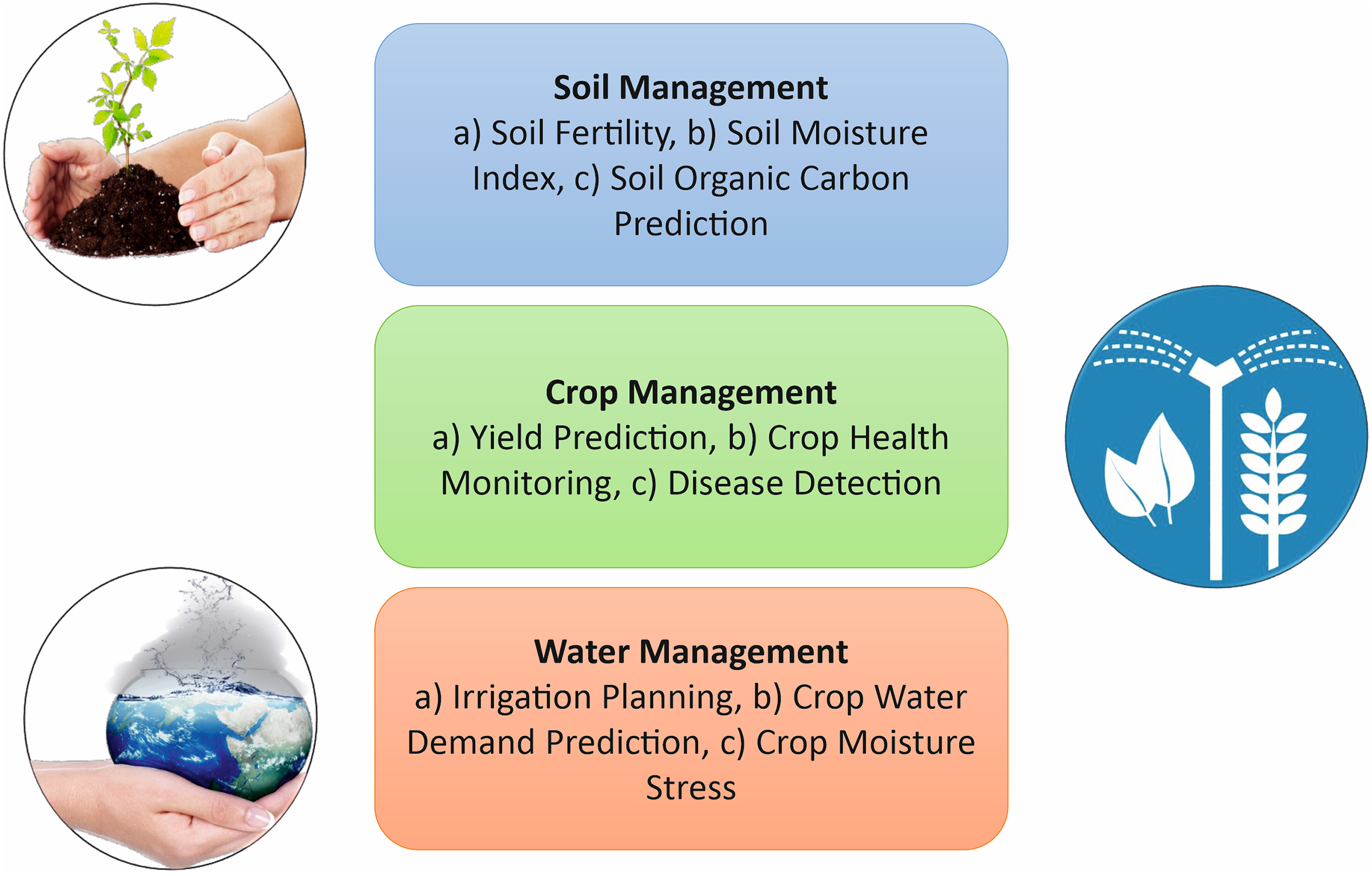

The applications of ML in agriculture are broadly categorized into soil management, crop management, water management (Fig. 5). Among these methods, soil health monitoring plays a pivotal role in sustainable agriculture, as it significantly contributes to sustainable farming practices, optimal crop productivity, and environmental conservation [7]. ML-driven insights directly enhance soil health and agricultural sustainability by enabling precision management of critical soil parameters.

Figure 5: Primary categories in agriculture using machine learning techniques

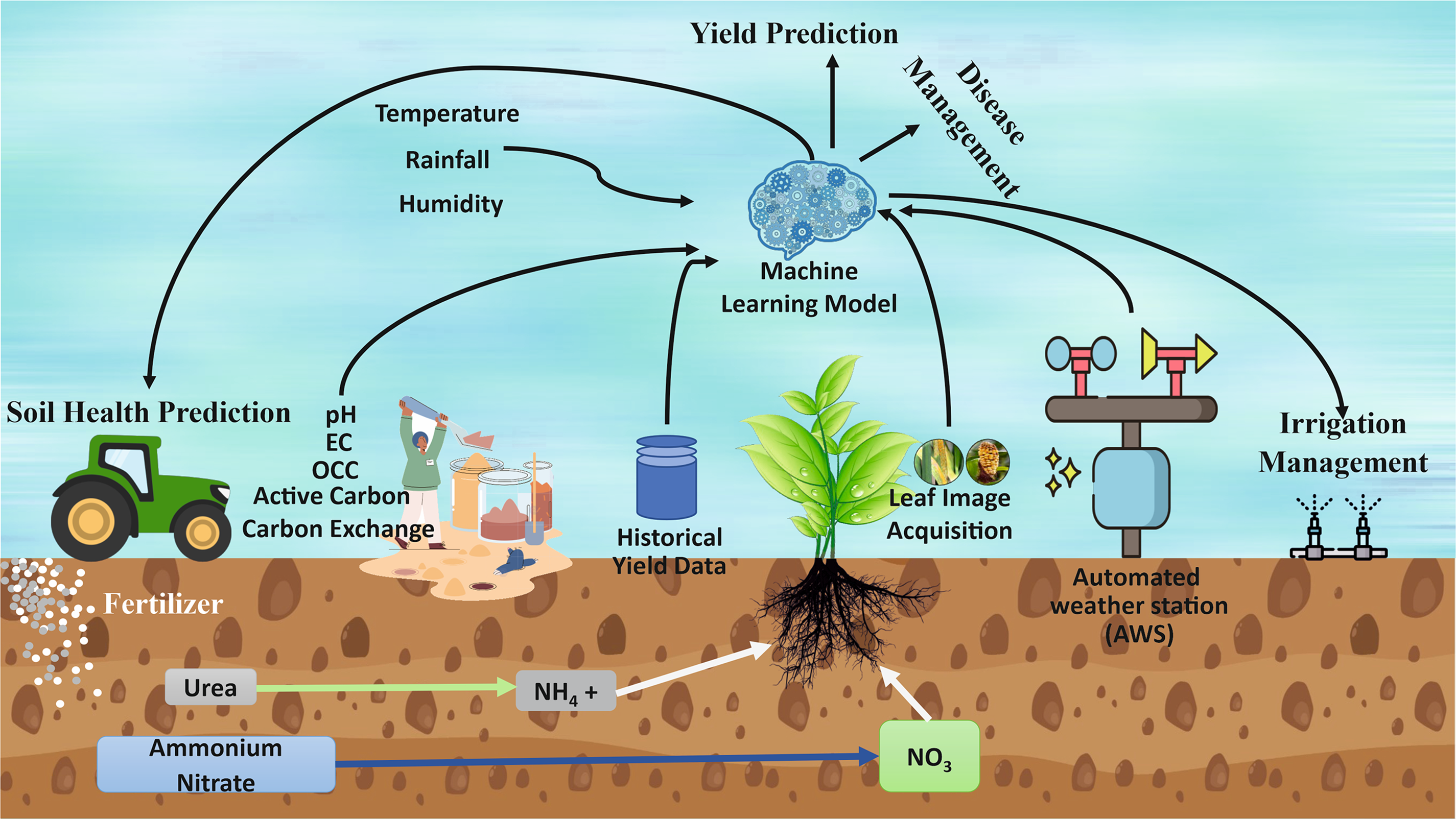

Recent advancements in ML have transformed soil health assessments by enabling exceptional precision and efficiency. These innovations allow comprehensive analysis of soil properties, such as nutrient content, moisture levels, and organic matter. Additionally, ML models can predict crop yields based on soil health parameters and optimize the utilization of resources, such as fertilizers and irrigation, to promote sustainability and minimize environmental degradation.

3.1 Machine Learning to Enhance Soil Health for Sustainable Crop Production

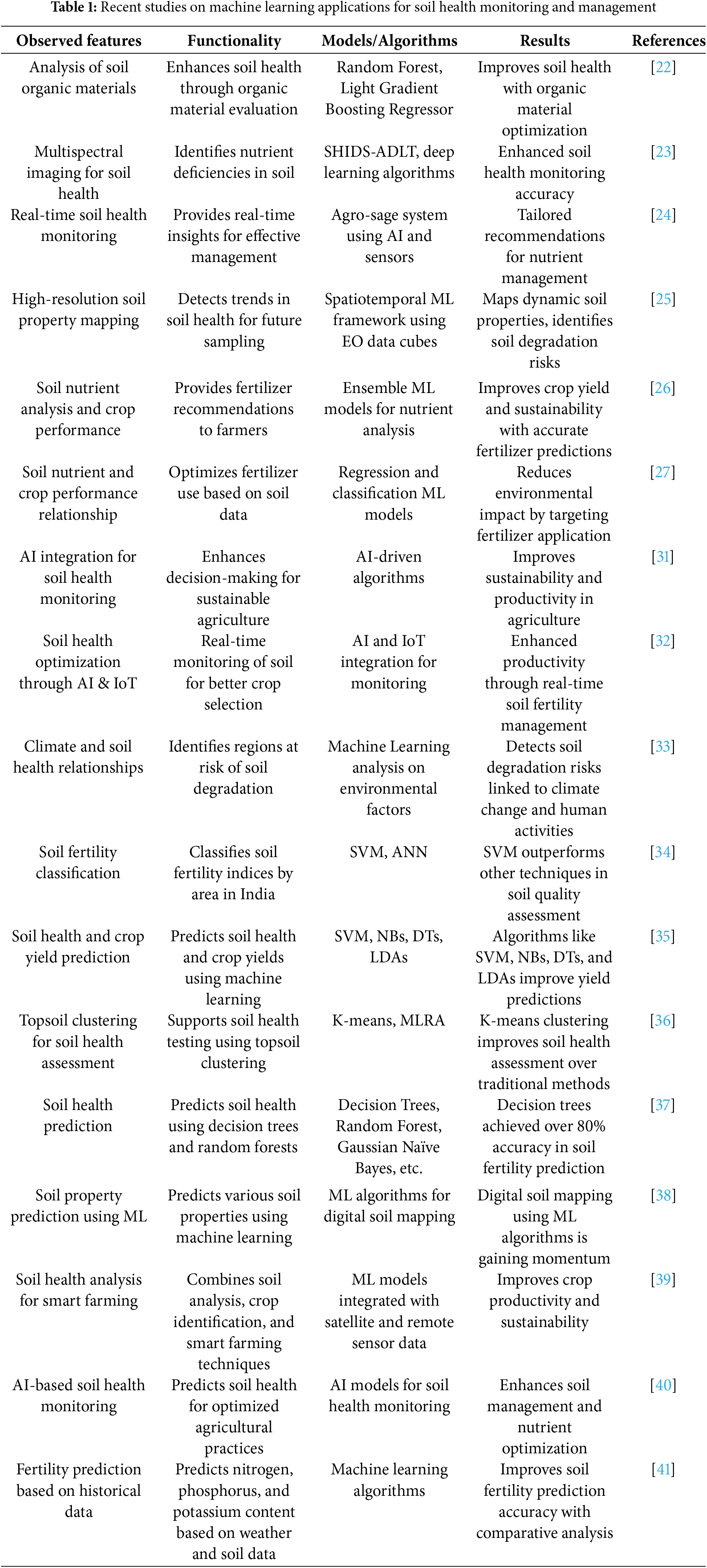

Studies using ML models, such as random forest regressors and light gradient boosting machines, on soil health indices reported a 23.8%–39.8% improvement when animal-sourced materials were used and compared with plant-sourced materials, with high coefficients of determination [22]. Similarly, the SHIDS-ADLT employs multispectral imaging combined with advanced DL techniques to provide accurate nutrient deficiency assessments and actionable recommendations for sustainable practices [23]. The integration of ML has further enhanced soil health monitoring by enabling real-time analysis of critical parameters such as soil moisture, pH, and nutrient level. For example, Agro-sage, an AI-powered system, uses sensor networks and ML models to monitor soil health, detect deficiencies, and deliver mobile-based recommendations, facilitate an effective nutrient management [24]. Spatiotemporal ML frameworks have demonstrated the success to map the dynamic of soil properties with high spatial resolution, identify trends and areas require further sampling [25]. Ensemble models such as extra trees and XGBoost have played important roles in soil health analysis, achieve accuracy levels of 93% in applications such as recovery to monitor the mining-impacted soils [26].

In Indian agriculture, an ensemble ML model significantly improved fertilizer recommendations by analyze the soil nutrient profiles, increase crop yields, and reduce environmental impacts [27]. By optimizing irrigation schedules (achieving 50% water savings) and predicting crop yields based on soil health indices, ML minimizes resource waste and aligns farming practices with sustainability. These advancements not only improved the soil fertility and crop resilience, and mitigate greenhouse gas emissions from excessive fertilizer use, supporting long-term ecological balance [28].

Despite these advancements, challenges persist including limited data on crop varieties, high computational power requirements, and difficulties in integrating advanced imaging techniques with deep learning models for agricultural applications. Additionally, environmental variability, overfitting in ML models, and biases in data preprocessing limit the effectiveness of robust soil health monitoring solutions. Addressing these challenges necessitates the development of lightweight, explainable AI models and improved data collection strategies to increase model robustness and scalability [29]. Hybrid frameworks that combine DL algorithms with domain-specific techniques such as SAM have shown promise in addressing low-quality datasets and detecting subtle changes in soil properties. IoT-enabled systems with edge computing capabilities offer scalable solutions for real-time monitoring in low-resource agricultural settings.

Future research should prioritize the development of novel architectures such as generative adversarial networks (GANs) for synthetic data augmentation and multimodal systems that integrate soil, climate, and crop data for comprehensive soil health assessments. Advanced imaging techniques, including hyperspectral and multispectral sensors combined with predictive analytics, may further support sustainable farming by enabling proactive soil management practices [30]. A summary of recent studies on ML applications in soil health monitoring is provided in Table 1.

3.2 Machine Learning in Crop Growth, Protection and Yield Management

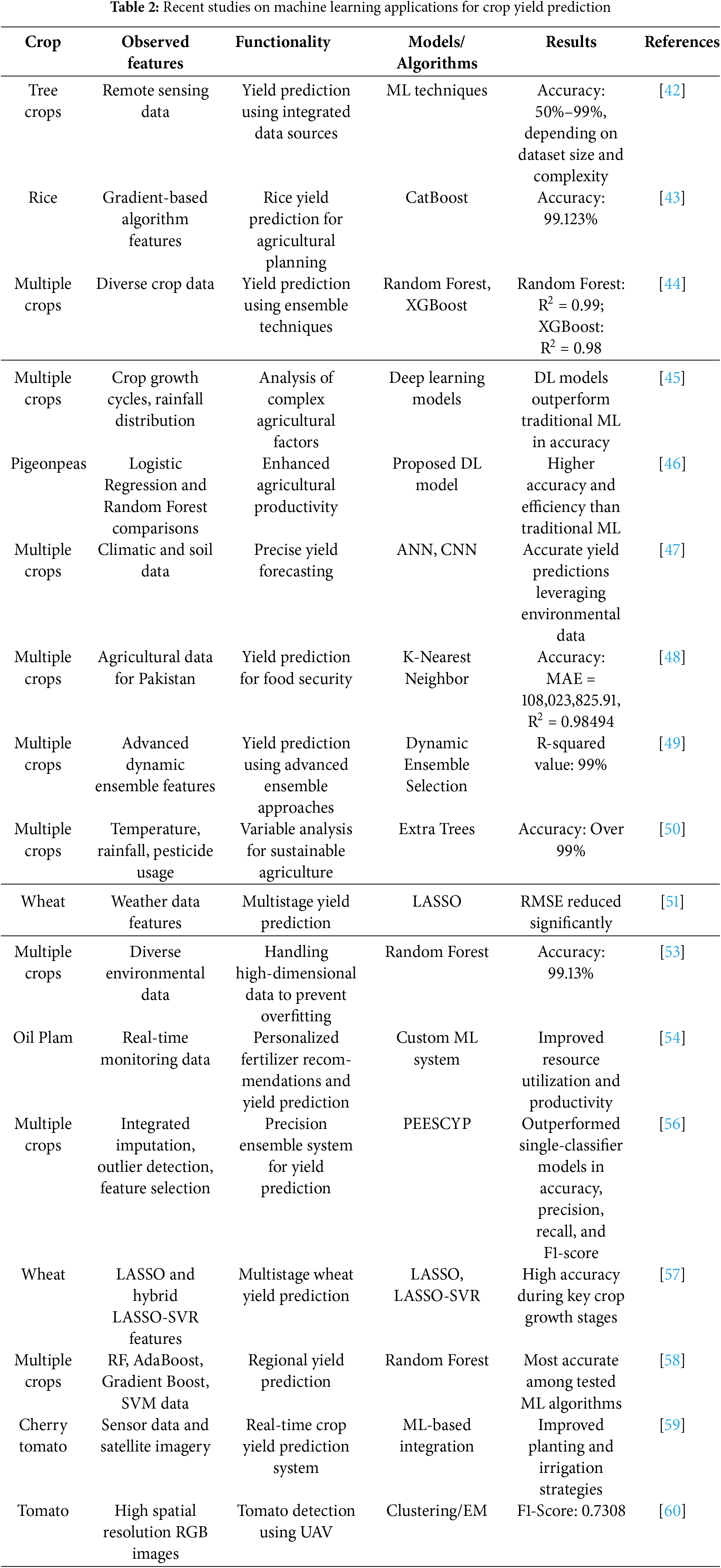

Crop yield prediction is a vital area in sustainable agriculture and plays an important role in efficient crop management, resource allocation, and sustainable agricultural practices (Fig. 6). Various studies have shown the application of ML models in enhancing predictive accuracy and efficiency, with significant contributions being made to agricultural productivity. For example, remote sensing and ML techniques have been integrated in systematic reviews for tree crop yield prediction, with accuracy levels ranging between 50% and 99%, depending on dataset size and complexity [42]. Similarly, studies have reported that gradient-based algorithms, particularly CatBoost, achieved the highest accuracy (99.123%) for rice yield prediction, showing its precision in agricultural planning [43]. The potential of ensemble models in real-world applications has been identified showing that Random Forest is the top-performing algorithm and the most accurate (R2 = 0.99) for yield prediction, whereas XGBoost is the faster alternative with slightly lower accuracy (R2 = 0.98) [44].

Figure 6: Application of machine learning in sustainable agriculture

Research has further highlighted the superiority of DL-based methods over traditional ML models in analyzing complex factors such as crop growth cycles and rainfall distributions [45]. For example, proposed DL models have been demonstrated to outperform logistic regression and random forest methods in both accuracy and efficiency, emphasizing their role in enhancing agricultural productivity [46]. Neural networks, particularly artificial neural networks (ANNs) and convolutional neural networks (CNNs), have demonstrated the ability to utilize climatic and soil data for precise yield forecasting [47]. In Pakistan, ML techniques such as K-nearest neighbor (KNN) have been applied to yield prediction and achieved high accuracy (MAE = 108,023,825.91, R2 = 0.98494 highlighting their potential for enhancing food security [48]. Other studies have employed innovative ensemble approaches, such as dynamic ensemble selection, achieving an R-squared value of 99%, advancing the efficacy of ensemble techniques in yield prediction [49]. The ability of ensemble methods such as extra trees to examine variables such as temperature, rainfall, and pesticide usage, achieving over 99% accuracy and supporting sustainable agriculture [50]. Weather-based prediction models, such as LASSO and hybrid LASSO-SVR, have been proven as effective for multistage wheat yield prediction, with excellent accuracy during critical crop growth stages [51]. Similarly, the integration of ML with historical weather data has demonstrated the ability to enhance decision-making in terms of planting, irrigation, and harvesting [52].

Emerging systems such as the precise ensemble expert system (PEESCYP) have combined imputation, outlier detection, and feature selection to improve metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, surpassing single-classifier models [53]. Another innovative approach includes personalized fertilizer recommendations coupled with crop yield prediction, which uses real-time monitoring to optimize resource utilization and productivity [54,55]. These advancements are further summarized in Table 2, which highlights key ML applications in crop yield prediction across diverse crops and conditions. Despite these advancements, several challenges have been identified, such as the lack of interpretability in some ML models, the high computational demands of DL techniques, and the limited exploration of diverse environmental data. The data availability and the need for real-world validation remain significant concerns. Addressing these gaps by developing robust algorithms, exploring novel frameworks, and improving data collection strategies could enhance the reliability and applicability of ML and DL models in sustainable agriculture. As sustainable agriculture evolves, the integration of traditional ML methods, such as decision trees and random forests, with emerging DL techniques such as CNNs, ANNs, and generative adversarial networks (GANs) offers immense potential to handle complex datasets and achieve higher predictive accuracy. Future research should continue to explore innovative solutions to optimize resource allocation, mitigate risks, and support global food security through data-driven agricultural practices.

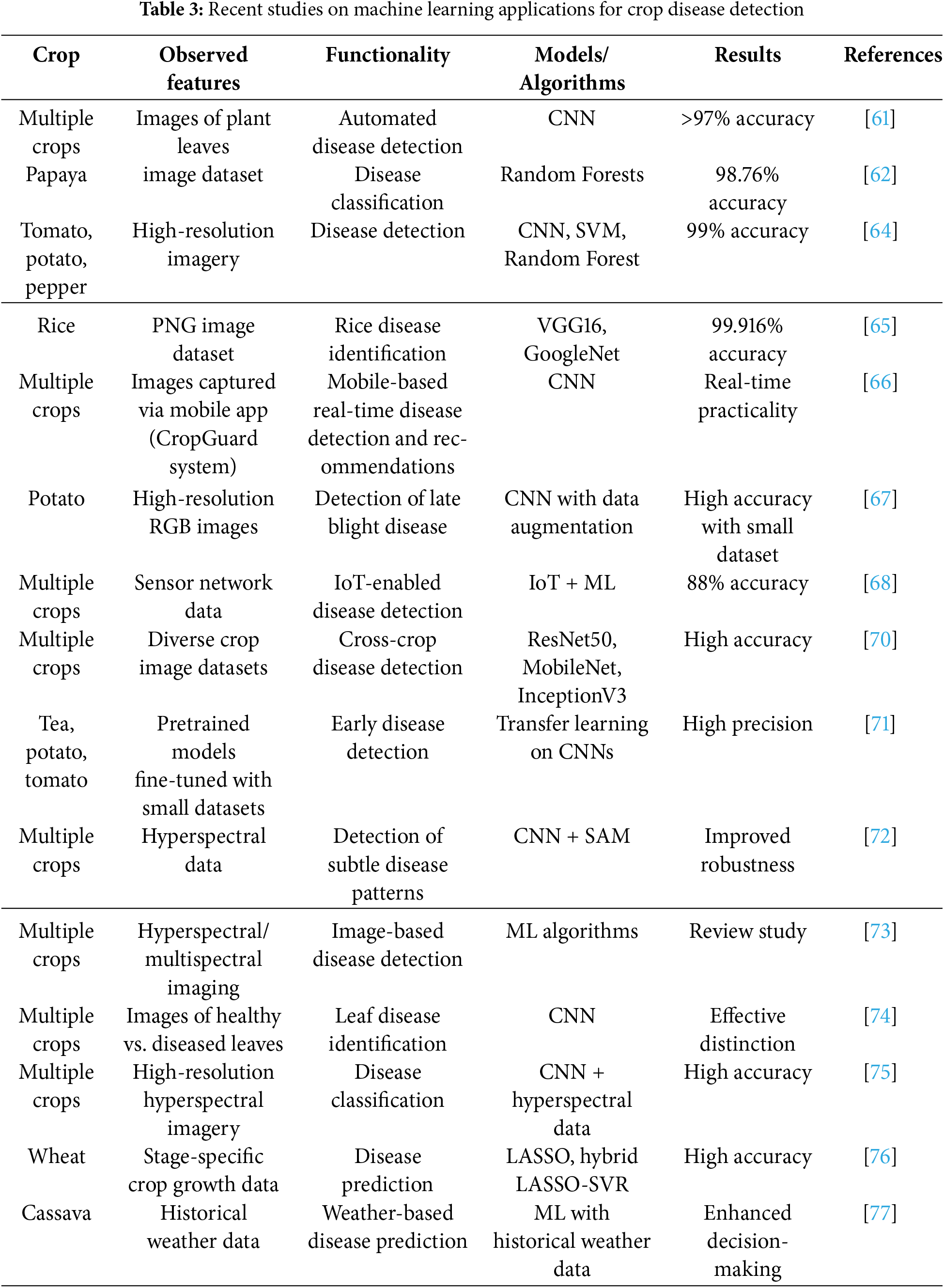

Studies employed CNNs for image-based disease detection have reported accuracy levels exceeding 97%, demonstrated the power of DL in automating the plant health assessments [61]. Specifically, the EfficientNetB3 model achieved a remarkable 98.76% accuracy on a dataset of 199,611 plant images, underscore its robustness in disease classification tasks [62]. Similarly, architectures such as ResNet50, MobileNet, and InceptionV3 have demonstrated exceptional performance across various crops and conditions, further enhance the scalability of disease detection systems for large-scale agricultural applications [63]. Hybrid models that integrate CNNs with other algorithms, such as support vector machines (SVMs) and random forests, have also proven effective to improve classification accuracy and model interpretability. For example, a CNN-based system achieved 99% accuracy to detect the diseases across the crops such as tomatoes, potatoes, and peppers via high-resolution imagery [64]. In another study, the VGG16 and GoogleNet architectures achieved up to 99.916% accuracy to identify rice diseases from PNG image datasets, emphasize the role of DL to support precision agriculture [65]. Ensemble methods such as extra trees and XGBoost have been pivotal to enhance detection accuracy and speed. Studies employed extra trees reported over 99% accuracy to analysis the factors such as temperature, humidity, and pest prevalence, making it a viable solution for real-time applications [50]. Ensemble-based systems such as CropGuard utilize CNNs within mobile apps to provide real-time disease identification and treatment recommendations, offering practical solutions for disease management [66]. Table 3 synthesizes recent breakthroughs in ML-driven crop disease detection, showcasing applications across diverse crops and imaging technologies.

Current research has focused to optimize the small data methodologies for in-field disease detection. A model detected the late blight in potato crops via high-resolution RGB images demonstrated real-world applicability and achieved high accuracy despite limited training data through innovative augmentation techniques [67]. Internet of Things (IoT)-enabled ML models gained traction, with sensor networks achieved an overall accuracy of 88% in disease detection, highlights their potential to reduce the human intervention and supporting smart agriculture [68]. These systems utilize the IoT to enhance data acquisition and enable real-time monitoring, paved the way for scalable, automated solutions in agricultural disease management. However, the widespread adoption of ML and DL in crop disease detection is hindered by challenges such as limited dataset diversity, high computational demands, and the lack of real-world validation. Environmental variability, data preprocessing, and unresolved integration issues between DL models and advanced imaging tools remain significant bottlenecks, particularly in field-based implementations.

These challenges require the development of lightweight, explainable algorithms and improved data collection strategies to ensure model generalizability. For example, hybrid frameworks that combine CNNs with techniques such as the spectral angle mapper (SAM) have shown improved robustness in detecting subtle disease patterns and addressing low-quality datasets [69]. The integration of advanced architectures such as EfficientNet and ResNet-50 with domain-specific knowledge can further increase the detection accuracy and operational efficiency. Additionally, emerging frameworks such as multimodal disease detection systems that combine image, climate, and soil data offer promising avenues for robust, scalable solutions.

Future research should explore novel hybrid architectures, generative adversarial networks (GANs) for synthetic data augmentation, and edge computing solutions for low-resource settings. Personalized disease management solutions leveraging real-time monitoring and predictive analytics hold significant potential for sustainable agriculture. The integration of ML, DL, and IoT technologies, coupled with advanced imaging techniques such as hyperspectral and multispectral sensors, could play a pivotal role to address the current limitations and supporting global food security.

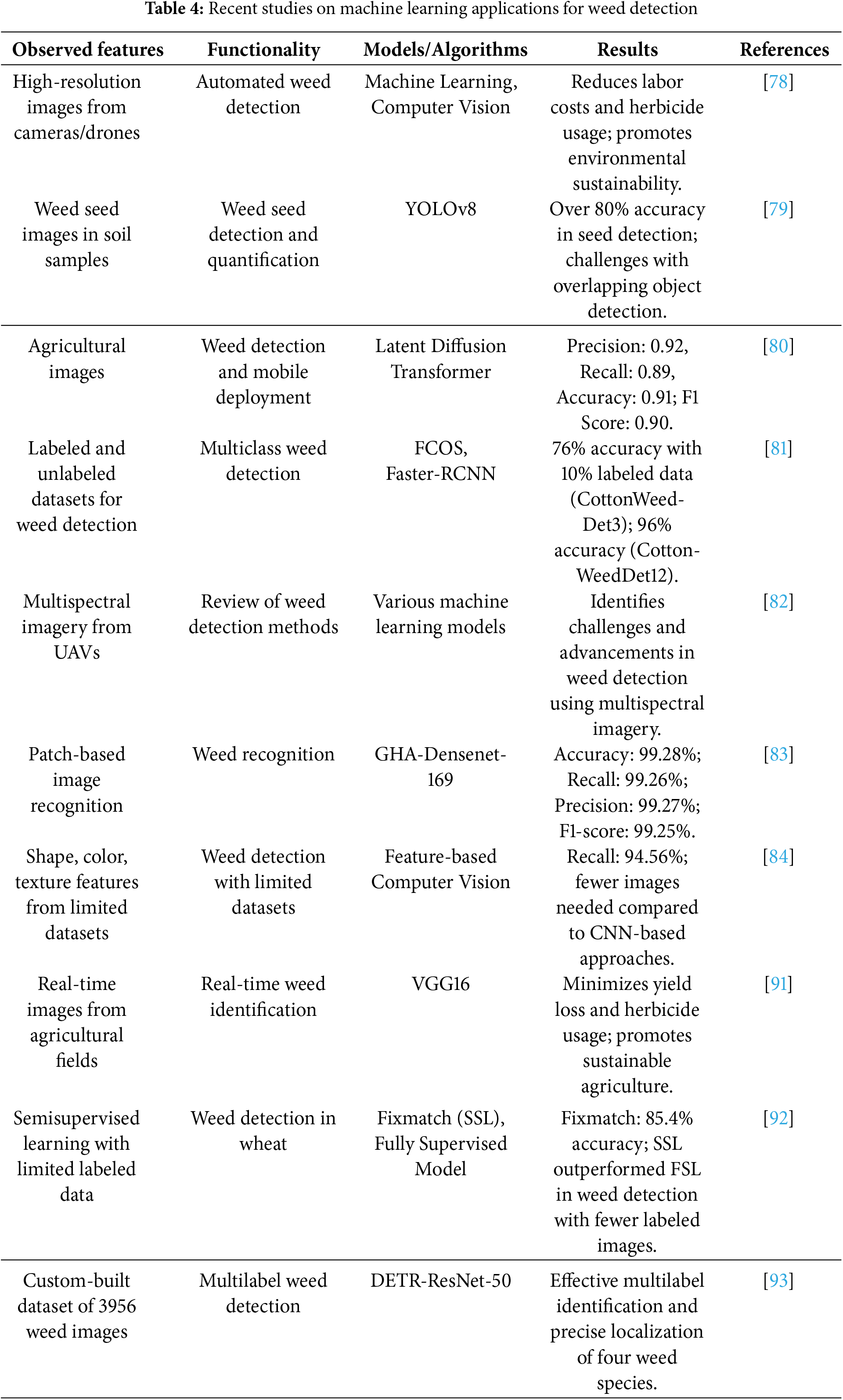

Weed detection and management play critical roles in precision agriculture, significantly influence crop yield, resource utilization, and environmental sustainability. Various studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of ML and DL models to improve weed identification accuracy and reduce reliance on traditional labor-intensive methods. An AI-based system that employs ML and computer vision techniques for automated weed detection, achieve substantial reductions in herbicide usage and promoting sustainability [78]. Similarly, YOLOv8, a DL model, was utilized for weed seed quantification, achieve over 80% accuracy, and addressed the challenges in traditional seedbank assessments [79]. Advanced architectures, such as the latent diffusion transformer, have shown remarkable performance in agricultural image analysis, obtaining 92% precision, 91% accuracy, and a 0.90 F1 score [80]. Furthermore, semisupervised learning frameworks may achieved accuracies of up to 96% with only 10% labeled data, showing the potential of generalized student-teacher approaches for reducing annotation costs while maintaining performance [81]. The integration of ML with multispectral imagery from UAVs, enabling efficient weed monitoring and detection of ecological challenges [82].

Deep learning models such as DenseNet-169 with a global hybrid attention mechanism have achieved unprecedented accuracy levels of 99.28% in weed classification [83]. Traditional feature-based methods have also showed 94.56% recall rate with limited datasets, emphasizing the utility of shape, color, and texture features in scenarios with limited data availability [84]. Recent studies on ML applications in weed management, including model architectures, datasets, and performance metrics, is provided in Table 4.

ML technologies have been extensively used to optimize irrigation management to improve agricultural efficiency. Machine learning integration in precision agriculture systems has reduced water waste by more than 50%, highlighting the effectiveness of automated water management. Similarly, multi-agent model predictive control frameworks have achieved 7%–23% water savings while increased irrigation water use efficiency by 10%–35%, demonstrated the impact of ML to enhance water conservation strategies [85]. Studies employed deep learning frameworks, such as UNet-ConvLSTM, have integrated spatial and temporal features to optimize water demand forecast, achieved high prediction accuracy (R2 > 0.92) via MODIS and GLDAS datasets [86]. Ridge regression models have also shown high precision in predict near-surface soil moisture (R2 = 0.98), address the randomness in irrigation events and assist an effective water management [87].

Clustering methods, such as K-means and K-shaped methods, enhance sensor data reliability, reduce errors by up to 5.4%, while robotic systems for sequential data collection improve sensor efficiency by reducing errors by 17.2% [88]. ML models, including CNNs, ANNs, and LSTMs, have achieved up to 94.5% accuracy in water distribution and can support sustainable agriculture [89]. Additionally, learning-based ensemble approaches, such as RF and LASSO regressors, have emerged as robust methods for irrigation optimization, using soil moisture, weather, and evapotranspiration data to achieve high predictive accuracy (R2 = 0.99) [90]. These studies underscore the transformative potential of ML in revolutionizing irrigation practices, promoting water conservation, and ensuring sustainable agricultural productivity.

Emerging technologies integrate the IoT with DL for real-time weed management. The VGG16 algorithm has achieved efficient weed identification and reduced yield losses [91]. Similarly, Fixmatch SSL demonstrated to outperform fully supervised learning in wheat weed detection, achieving 85.4% accuracy with fewer labeled images [92]. The DETR-ResNet-50 model has been utilized for multilabel weed detection, highlights its potential for precise localization and identification in real-world agricultural environments [93].

Despite significant advancements, several critical challenges minimize the extensive use of ML in agriculture. Primarily, the data quality and variety remain major concerns. Many studies utilized region-specific datasets, such as those from Indian or Chinese agricultural systems, which limit the cross-regional generalization. Biases in data collection, such as the underrepresentation of smallholder farms, further reduce model accuracy and applicability [94]. Furthermore, model interpretability is a persistent issue. Black-box models like Deep Neural Networks lack transparency, making it difficult for farmers to trust and adopt automated recommendations [95]. High-resolution imaging and real-time analytics require significant computational resources, which are often unavailable in low-resource environments [96]. There is a notable gap between laboratory-validated models and their field performance. For example, models achieved 95% accuracy in disease detection under controlled conditions often underperform in real-world scenarios due to factors like lighting variability and soil heterogeneity [97]. These challenges requires collaborative efforts to standardize datasets, adopt explainable AI (XAI) techniques, and develop lightweight models for edge computing, ensuring ML solutions are both effective and accessible [98]. Soil variability and diverse cultivation practices present significant challenges to the generalization of ML applications in agriculture. Soil properties, such as texture, structure, and nutrient composition, can vary widely across different regions and even within the same field. This heterogeneity complicates the development of ML models that can accurately predict outcomes across varied soil conditions. For example, a model trained on data from a specific soil type may not perform well when applied to areas with different soil characteristics, leading to reduced predictive accuracy [99]. Similarly, cropping systems differ globally in terms of crop types, rotation practices, and management strategies. These variations influence factors such as pest, disease incidence, and yield outcomes. An ML model developed within a particular cropping system may not be directly applicable to another system with different practices, limiting the model’s generalizability [100]. To enhance the generalization of ML applications in agriculture, it is crucial to incorporate diverse and representative datasets that encompass a wide range of soil types and cultivation practices. This approach can improve the robustness and applicability of ML models across various agricultural contexts [101].

5 Future Framework for Sustainable Agriculture

A key issue in the field is the common lack of detailed information about model algorithms, training processes, and data management. This void in the literature makes it difficult to replicate studies and slows down the use of ML models successfully in agriculture. To improve transparency and make ML in sustainable agriculture easier to replicate, future studies should follow stricter guidelines for authenticate and share models and datasets. Despite these issues, the availability of various datasets from sensors has been essential in advancing the field of ML. These datasets provide valuable insights into growth trends, crop health, and environmental implications. However, using such rich and high-dimensional data in ML models creates additional complexity, require advanced modeling and analytic tools. Auto machine learning (AutoML) has emerged as a promising solution to these issues, simplify the creation and use of ML models. The integration of IoT and smart sensors with AutoML frameworks is a forward-looking addition to adaptive farming. For example, IoT devices embedded with hyperspectral sensors can continuously monitor crop stress indicators, while AutoML systems autonomously optimize predictive models for disease outbreaks or nutrient deficiencies. This synergy reduces dependency on manual interventions and ensures real-time responsiveness to field conditions.

AutoML has the potential to increase the accessibility and applicability of advanced ML approaches to a wider range of agricultural problems by automating crucial ML tasks such as feature engineering, model selection, and hyperparameter optimization. For example, predicting crop yield via satellite data traditionally involves manually creating and adjusting models to analyze satellite images and extract useful information for prediction [102]. This technique needs great skill and can be time-consuming and prone to error. In contrast, AutoML technologies can automatically choose the right model and preprocessing steps, accelerating the development process. An AutoML system may automatically evaluate various CNN architectures, adjust preprocessing approaches for satellite imagery, and tune hyperparameters depending on the performance metrics, all without considerable operator intervention. This AutoML-driven approach simplifies the modeling process and creates new possibilities for integrating different data sources into predictive models. By decreasing the obstacles to advanced ML applications, AutoML can accelerate innovations in agricultural research, leading to more accurate, efficient, and scalable solutions for crop production, prediction, and other crucial concerns. To achieve the full potential of AutoML in agriculture, future research must focus on developing customized AutoML tools for agricultural data and issues. This involves improving data preprocessing methods, integrating domain-specific knowledge into AutoML algorithms, and enhancing model interpretability. For IoT-based farming, innovations like cloud computing and lightweight ML models will be essential to process sensor data locally on low-power devices, reducing latency and bandwidth costs in rural areas. By addressing these areas, the agricultural research community may employ AutoML to enhance the state of the art in agricultural ML and DL, ultimately leading to more sustainable and productive farming techniques worldwide.

5.1 Policy-Driven Frameworks of ML for Sustainable Agriculture

To enhance the socioeconomic effect of ML, future frameworks must align with global agricultural policies. For example, ML models predicting soil degradation risk could inform the European Union Common Agricultural Policy incentives for conservation tillage [103]. Similarly, AutoML-based irrigation systems could be incorporated in India’s National Mission for Sustainable Agriculture to improve the water-use efficiency [104]. Governments and NGOs should collaborate to develop certification programs for ML tools that meet sustainability benchmarks, ensuring that technologies like IoT-enabled nutrient sensors are accessible to smallholder farms. Such policy integration would bridge the gap between theoretical ML and on-the-ground agricultural needs [105].

AutoML is transforming ML implementation in agriculture by automating model selection, hyperparameter tuning, and feature engineering, hence reducing the need for deep technical expertise. For example, in crop yield prediction tools like AutoKeras and H2O. AI can rapidly optimize ensemble models, blending algorithms like XGBoost and CNNs for satellite data analysis. Similarly, in disease detection, platforms such as Google Cloud AutoML Vision allow farmers to train custom image classifiers with minimal coding, enhancing accessibility. However, AutoML’s ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach may neglect essential domain-specific complexity, such as soil microvariability or region-specific pest behaviors. To address this issue, hybrid solutions that combine subject expertise with the automation of AutoML are essential. Domain-driven feature engineering integrated with automated hyperparameter tuning may provide models that are both precise and spatially relevant. As AutoML tools become more accessible, their adoption can accelerate the implementation of ML solutions in agriculture, especially in resource-limited environments. Future advancements like adaptive learning models adapted for changing agricultural conditions could further enhance AutoML’s impact on precision farming.

Recent improvements in ML algorithms offer intriguing paths for attaining these goals. These advances enable monitoring of populations in general and the enhancement of crop yield while limiting disturbance to the natural environment. However, further research is necessary due to the novelty of implementing ML models in agriculture. In agriculture, the most widely utilized ML models are SVM and RF. However, the implementation of novel methodologies, including AutoML, XGBOOST, and regression models such as linear and LR, has the potential to increase model performance. The efficiency of these models in agricultural decision-making can be significantly influenced by even modest increases in accuracy and runtime. Future advancements are expected to focus on the development and enhancement of ML algorithms that can help farmers manage crops. These models can be integrated into decision-support systems, leading users through structured phases and presenting viable options. The development of these models is expected to enable more efficient agricultural management with minimal human interaction.

A systematic review of 2718 studies were conducted to examine the current state of knowledge regarding ML approaches in sustainable agriculture based on bibliometric and thematic analyses. Methodological frameworks and approach advancements within this domain were scrutinized, with a particular emphasis on recently adopted models. Although many reviewed articles employed ML models in agricultural contexts, uncertainties remain in forecasting agricultural outcomes under changing environmental conditions. However, advanced models that integrate various facets of agricultural systems for comprehensive risk assessment are limited. The review highlighted the various uses of ML in the domain of sustainable agriculture and soil health management. Strategies such as decreasing pesticide consumption, promoting organic farming, establishing optimal crop rotations, and preserving natural gaps between agricultural systems are recognized as key components to contribute to sustainable agricultural practices. Farming may function more effectively by adopting new sustainable techniques backed by ML algorithms. The integration of these technologies into agricultural systems holds enormous potential for enhancing the sustainability and productivity of farming operations in the future. This study highlights the potential for future investigations, guiding researchers, practitioners, and policymakers toward more informed decision-making and innovation in sustainable agriculture.

Acknowledgement: The research was financially supported by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation (no. FENW-2023-0008) and the Strategic Academic Leadership Program of Southern Federal University, known as “Priority 2030”.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design, data collection, interpretation of results, draft manuscript preparation: Vicky Anand and Priyadarshani Rajput; Supervision, review and editing: Vishnu D. Rajput, Tatiana Minkina, Saglara Mandzhieva, Santosh Kumar and Avnish Chauhan. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Appendix A

Figure A1: Geographical distribution of scientific publications on machine learning in agriculture and soil health

References

1. Khatri P, Kumar P, Shakya KS, Kirlas MC, Tiwari KK. Understanding the intertwined nature of rising multiple risks in modern agriculture and food system. Environ Dev Sustain. 2024;26(9):24107–50. doi:10.1007/s10668-023-03638-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Mergos G. Population and food system sustainability. In: International handbook of population policies. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2022. p. 131–55. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-02040-7_7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Nawaz MA, Chung G. Genetic improvement of cereals and grain legumes. Genes. 2020;11(11):1255. doi:10.3390/genes11111255. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Falcon WP, Naylor RL, Shankar ND. Rethinking global food demand for 2050. Popul Dev Rev. 2022;48(4):921–57. doi:10.1111/padr.12508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Adisa O, Ilugbusi BS, Adelekan OA, Asuzu OF, Ndubuisi NL. A comprehensive review of redefining agricultural economics for sustainable development: overcoming challenges and seizing opportunities in a changing world. World J Adv Res Rev. 2024;21(1):2329–41. doi:10.30574/wjarr.2024.21.1.0322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Singh A, Mehrotra R, Rajput VD, Dmitriev P, Singh AK, Kumar P, et al. Geoinformatics, artificial intelligence, sensor technology, big data. Sustain Agric Syst Technol. 2022:295–313. doi:10.1002/9781119808565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Ayoub Shaikh T, Rasool T, Rasheed Lone F. Towards leveraging the role of machine learning and artificial intelligence in precision agriculture and smart farming. Comput Electron Agric. 2022;198:107119. doi:10.1016/j.compag.2022.107119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Anand V, Rajput VD, Minkina T, Mandzhieva S, Sharma A, Kumar S, et al. Predicting weather conditions for improving crop productivity using machine learning approaches. In: Nanotechnology applications and innovations for improved soil health. Hershey, PA, USA: IGI Global; 2024. p. 143–71. doi:10.4018/979-8-3693-1471-5.ch008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Nirmala N, Arun J, Sanjay Kumar S, Dawn SS. Role of machine learning and artificial intelligence in smart waste management. In: Smart waste and wastewater management by biotechnological approaches. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore; 2025. p. 35–53. doi:10.1007/978-981-97-8673-2_3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Javaid M, Haleem A, Khan IH, Suman R. Understanding the potential applications of artificial intelligence in agriculture sector. Adv Agrochem. 2023;2(1):15–30. doi:10.1016/j.aac.2022.10.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Marwaha S, Deb CK, Haque MA, Naha S, Maji AK. Application of artificial intelligence and machine learning in agriculture. In: Translating physiological tools to augment crop breeding. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore; 2023. p. 441–57. doi:10.1007/978-981-19-7498-4_21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Liakos KG, Busato P, Moshou D, Pearson S, Bochtis D. Machine learning in agriculture: a review. Sensors. 2018;18(8):2674. doi:10.3390/s18082674. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Ed-Daoudi R, Alaoui A, Ettaki B, Zerouaoui J. Improving crop yield predictions in Morocco using machine learning algorithms. J Ecol Eng. 2023;24(6):392–400. doi:10.12911/22998993/162769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Maya Gopal PS, Bhargavi R. Performance evaluation of best feature subsets for crop yield prediction using machine learning algorithms. Appl Artif Intell. 2019;33(7):621–42. doi:10.1080/08839514.2019.1592343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Pande CB, Moharir KN. Application of hyperspectral remote sensing role in precision farming and sustainable agriculture under climate change: a review. In: Climate change impacts on natural resources, ecosystems and agricultural systems. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2023. p. 503–20. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-19059-9_21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Yang CH. Remote sensing and precision agriculture technologies for crop disease detection and management with a practical application example. Engineering. 2020;6(5):528–32. doi:10.1016/j.eng.2019.10.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Dong AY, Wang Z, Huang JJ, Song BA, Hao GF. Bioinformatic tools support decision-making in plant disease management. Trends Plant Sci. 2021;26(9):953–67. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2021.05.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Assuncao E, Diniz C, Gaspar PD, Proenca H. Decision-making support system for fruit diseases classification using Deep Learning. In: 2020 International Conference on Decision Aid Sciences and Application (DASA); 2020 Nov 8–9; Sakheer, Bahrain. p. 652–656. doi:10.1109/dasa51403.2020.9317219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Linaza MT, Posada J, Bund J, Eisert P, Quartulli M, Döllner J, et al. Data-driven artificial intelligence applications for sustainable precision agriculture. Agronomy. 2021;11(6):1227. doi:10.3390/agronomy11061227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Kim WS, Lee WS, Kim YJ. A review of the applications of the Internet of Things (IoT) for agricultural automation. J Biosyst Eng. 2020;45(4):385–400. doi:10.1007/s42853-020-00078-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339(211):b2535. doi:10.1136/bmj.b2535. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Shi C, Zhang Q, Yu B. Higher improvement in soil health by animal-sourced than plant-sourced organic materials through optimized substitution. Agric Ecosyst Environ. 2024;363:108875. doi:10.1016/j.agee.2023.108875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Dhanalakshmi B. Soil health intelligence system using multispectral imaging and advanced deep learning techniques (SHIDS-ADLT). Cana. 2024;31(6s):417–26. doi:10.52783/cana.v31.1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Reddy TV, Reddy RA, Prasanna KS, Shiva SS, Meghana S, Reddy TSS. Design and developing AI-driven agro-sage for optimal precision agriculture. In: 2024 5th International Conference on Smart Electronics and Communication (ICOSEC); 2024 Sep 18–20; Trichy, India. p. 1538–42. doi:10.1109/ICOSEC61587.2024.10722046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Hengl T, Minarik R, Parente L, Tian X. Mapping dynamic soil properties at high spatial resolution using spatio-temporal Machine Learning: towards a consistent framework for monitoring soil health across borders. EGU General Assembly. 2024. doi:10.5194/egusphere-egu24-17704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Lima HS, Oliveira GFV, Ferreira RDS, Castro AG, Silva LCF, Ferreira LS, et al. Machine learning-based soil quality assessment for enhancing environmental monitoring in iron ore mining-impacted ecosystems. J Environ Manage. 2024;356:120559. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.120559. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Thorat BD. Smart farming in the Indian context: fertilizer prediction through ensemble machine learning based soil nutrient analysis. Pmj. 2024;33(4):86–98. doi:10.52783/pmj.v33.i4.897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Getahun S, Kefale H, Gelaye Y. Application of precision agriculture technologies for sustainable crop production and environmental sustainability: a systematic review. Sci World J. 2024;2024:2126734. doi:10.1155/2024/2126734. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Liu H, Zhong C, Alnusair A, Islam SR. FAIXID: a framework for enhancing AI explainability of intrusion detection results using data cleaning techniques. J Netw Syst Manag. 2021;29(4):40. doi:10.1007/s10922-021-09606-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Adewusi AO, Asuzu OF, Olorunsogo T, Iwuanyanwu C, Adaga E, Daraojimba DO. AI in precision agriculture: a review of technologies for sustainable farming practices. World J Adv Res Rev. 2024;21(1):2276–85. doi:10.30574/wjarr.2024.21.1.0314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Awais M, Naqvi SMZA, Zhang H, Li L, Zhang W, Awwad FA, et al. AI and machine learning for soil analysis: an assessment of sustainable agricultural practices. Bioresour Bioprocess. 2023;10(1):90. doi:10.1186/s40643-023-00710-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Arısoy A, Açıkgözoğlu E. Optimizing soil fertility through machine learning: enhancing agricultural productivity and sustainability. Bilge Int J Sci Technol Res. 2024;8(2):124–33. doi:10.30516/bilgesci.1532645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Afshar MH, Hassani A, Aminzadeh M, Borrelli P, Panagos P, Robinson DA, et al. AI-driven insights into soil health and soil degradation in Europe in the face of climate and anthropogenic challenges. In: EGU General Assembly Conference Abstracts; 2024 Apr 14–19; Vienna, Austria. doi:10.5194/egusphere-egu24-9512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Kanade P. Soil analysis using machine learning. Br J Multidiscip Adv Stud. 2023;4(6):1–11. doi:10.37745/bjmas.2022.0350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Kiruthiga C, Dharmarajan K. Machine learning in soil borne diseases, soil data analysis & crop yielding: a review. In: 2023 International Conference on Intelligent and Innovative Technologies in Computing, Electrical and Electronics (IITCEE); 2023 Jan 27–28; Bengaluru, India. p. 702–6. doi:10.1109/IITCEE57236.2023.10091016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Blair HK, Gutknecht JL, Cates AM, Lewandowski AM, Jelinski NA. A data-driven topsoil classification framework to support soil health assessment in Minnesota. Agrosystems Geosci Env. 2024;7(2):e20523. doi:10.1002/agg2.20523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Swapna B, Manivannan S, Kamalahasan M. Prognostic of soil nutrients and soil fertility index using machine learning classifier techniques. Int J E Collab. 2022;18(2):1–14. doi:10.4018/IJeC. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Sweta K, Dharumarajan S, Suputhra A, Lalitha M, Vasundhara R, Kalaiselvi B, et al. Transforming soil paradigms with machine learning. In: Data science in agriculture and natural resource management. Singapore: Springer Singapore; 2021. p. 243–65. doi: 10.1007/978-981-16-5847-1_12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Pant J, Pant HK, Bhatt A, Pant D, Bhatt J. Intelligent machine learning modelling for soil analysis and pH prediction. In: 2024 7th International Conference on Circuit Power and Computing Technologies (ICCPCT); 2024 Aug 8–9; Kollam, India. p. 1195–8. doi:10.1109/ICCPCT61902.2024.10673053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Romic M, Mornar V, Reljic M, Slapnicar A, Babac MB, Romic D. Utilizing artificial intelligence (AI) to develop soil health index for salinized coastal agricultural land. J Coast Res. 2024;113(sp1):225–9. doi:10.2112/JCR-SI113-045.1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Chandra H, Pawar PM, Elakkiya R, Tamizharasan PS, Muthalagu R, Panthakkan A. Explainable AI for soil fertility prediction. IEEE Access. 2023;11:97866–78. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3311827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Trentin C, Ampatzidis Y, Lacerda C, Shiratsuchi L. Tree crop yield estimation and prediction using remote sensing and machine learning: a systematic review. Smart Agric Technol. 2024;9(1):100556. doi:10.1016/j.atech.2024.100556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Mahesh P, Soundrapandiyan R. Yield prediction for crops by gradient-based algorithms. PLoS One. 2024;19(8):e0291928. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0291928. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Hu T, Zhang X, Bohrer G, Liu Y, Zhou Y, Martin J, et al. Crop yield prediction via explainable AI and interpretable machine learning: dangers of black box models for evaluating climate change impacts on crop yield. Agric For Meteor. 2023;336(12):109458. doi:10.1016/j.agrformet.2023.109458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Wang Y, Zhang Q, Yu F, Zhang N, Zhang X, Li Y, et al. Progress in research on deep learning-based crop yield prediction. Agronomy. 2024;14(10):2264. doi:10.3390/agronomy14102264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Logeshwaran J, Srivastava D, Kumar KS, Rex MJ, Al-Rasheed A, Getahun M, et al. Improving crop production using an agro-deep learning framework in precision agriculture. BMC Bioinformatics. 2024;25(1):341. doi:10.1186/s12859-024-05970-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Joel MR, Ebenezer V, Kirubakaran SS, Edwin EB, Thanka MR, Alex EJ. Revolutionising crop yield prediction in agriculture. In: Artificial intelligence for precision agriculture. Boca Raton, FL, USA: Auerbach Publications; 2024. p. 203–20. doi: 10.1201/9781003504900-10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Anwar MH. Crop yield prediction using machine-learning. J Innov Comput Emerg Technol. 2024;4(2). doi:10.56536/jicet.v4i2.136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Li QC, Xu SW, Zhuang JY, Liu JJ, Zhou Y, Zhang ZX. Ensemble learning prediction of soybean yields in China based on meteorological data. J Integr Agric. 2023;22(6):1909–27. doi:10.1016/j.jia.2023.02.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Abbas F, Afzaal H, Farooque AA, Tang S. Crop yield prediction through proximal sensing and machine learning algorithms. Agronomy. 2020;10(7):1046. doi:10.3390/agronomy10071046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Aravind KS, Vashisth A, Krishnan P, Kundu M, Prasad S, Meena MC, et al. Development of multistage crop yield estimation model using machine learning and deep learning techniques. Int J Biometeorol. 2025;69(2):499–515. doi:10.1007/s00484-024-02829-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Hu T, Zhang X, Khanal S, Wilson R, Leng G, Toman EM, et al. Climate change impacts on crop yields: a review of empirical findings, statistical crop models, and machine learning methods. Environ Model Softw. 2024;179(12):106119. doi:10.1016/j.envsoft.2024.106119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Dhillon MS, Dahms T, Kuebert-Flock C, Rummler T, Arnault J, Steffan-Dewenter I, et al. Integrating random forest and crop modeling improves the crop yield prediction of winter wheat and oil seed rape. Front Remote Sens. 2023;3:1010978. doi:10.3389/frsen.2022.1010978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Musanase C, Vodacek A, Hanyurwimfura D, Uwitonze A, Kabandana I. Data-driven analysis and machine learning-based crop and fertilizer recommendation system for revolutionizing farming practices. Agriculture. 2023;13(11):2141. doi:10.3390/agriculture13112141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Shahab H, Naeem M, Iqbal M, Aqeel M, Ullah SS. IoT-driven smart agricultural technology for real-time soil and crop optimization. Smart Agric Technol. 2025;10(1):100847. doi:10.1016/j.atech.2025.100847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Tripathi D, Biswas SK. Design of a precise ensemble expert system for crop yield prediction using machine learning analytics. J Forecast. 2024;43(8):3161–76. doi:10.1002/for.3183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Gupta S, Vashisth A, Krishnan P, Lama A, Prasad S, Aravind KS. Multistage wheat yield prediction using hybrid machine learning techniques. J Agrometeorol. 2022;24(4):373–9. doi:10.54386/jam.v24i4.1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Elbasi E, Zaki C, Topcu AE, Abdelbaki W, Zreikat AI, Cina E, et al. Crop prediction model using machine learning algorithms. Appl Sci. 2023;13(16):9288. doi:10.3390/app13169288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Fujiuchi N, Inaba K, Shinchu OH, Okajima S, Asai Y, Nishina H, et al. Using a real-time photosynthesis and transpiration monitoring system to develop random forests models for predicting cherry Toma to yield in a commercial greenhouse. Environ Control Biol. 2024;62(2):29–39. doi:10.2525/ecb.62.29. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Ahmed I, Yadav PK. Plant disease detection using machine learning approaches. Expert Syst. 2023;40(5):e13136. doi:10.1111/exsy.13136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Tomar V, Pradeepa M, Shankar SS, Ashaq M, Vaishnav PV. Enhancing plant disease detection through image processing and deep learning techniques. In: Challenges in information, communication and computing technology. London, UK: CRC Press; 2024. p. 349–54. doi:10.1201/9781003559092-60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Ferentinos KP. Deep learning models for plant disease detection and diagnosis. Comput Electron Agric. 2018;145(6):311–8. doi:10.1016/j.compag.2018.01.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Pacal I, Kunduracioglu I, Alma MH, Deveci M, Kadry S, Nedoma J, et al. A systematic review of deep learning techniques for plant diseases. Artif Intell Rev. 2024;57(11):304. doi:10.1007/s10462-024-10944-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Shoaib M, Shah B, Ei-Sappagh S, Ali A, Ullah A, Alenezi F, et al. An advanced deep learning models-based plant disease detection: a review of recent research. Front Plant Sci. 2023;14:1158933. doi:10.3389/fpls.2023.1158933. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Sharma M, Kumar CJ, Bhattacharyya DK. Machine/deep learning techniques for disease and nutrient deficiency disorder diagnosis in rice crops: a systematic review. Biosyst Eng. 2024;244(2):77–92. doi:10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2024.05.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Khan F, Zafar N, Tahir MN, Aqib M, Waheed H, Haroon Z. A mobile-based system for maize plant leaf disease detection and classification using deep learning. Front Plant Sci. 2023;14:1079366. doi:10.3389/fpls.2023.1079366. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Lu J, Hu J, Zhao G, Mei F, Zhang C. An in-field automatic wheat disease diagnosis system. Comput Electron Agric. 2017;142(3):369–79. doi:10.1016/j.compag.2017.09.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Sukhadeo BS, Sinkar YD, Dhurgude SD, Athawale SV. Plant disease detection using machine learning techniques based on Internet of Things (IoT) sensor network. Internet Technol Lett. 2025;8(2):e546. doi:10.1002/itl2.546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Khattak A, Asghar MU, Batool U, Asghar MZ, Ullah H, Al-Rakhami M, et al. Automatic detection of Citrus fruit and leaves diseases using deep neural network model. IEEE Access. 2021;9:112942–54. [Google Scholar]

70. Pandian J, Kumar V, Geman O, Hnatiuc M, Arif M, Kanchanadevi K. Plant disease detection using deep convolutional neural network. Appl Sci. 2022;12(14):6982. doi:10.3390/app12146982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Harakannanavar SS, Rudagi JM, Puranikmath VI, Siddiqua A, Pramodhini R. Plant leaf disease detection using computer vision and machine learning algorithms. Glob Transitions Proc. 2022;3(1):305–10. doi:10.1016/j.gltp.2022.03.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Ali F, Razzaq A, Tariq W, Hameed A, Rehman A, Razzaq K, et al. Spectral intelligence: ai-driven hyperspectral imaging for agricultural and ecosystem applications. Agronomy. 2024;14(10):2260. doi:10.3390/agronomy14102260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Dolatabadian A, Neik TX, Danilevicz MF, Upadhyaya SR, Batley J, Edwards D. Image-based crop disease detection using machine learning. Plant Pathol. 2025;74(1):18–38. doi:10.1111/ppa.14006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Hassan SM, Maji AK, Jasiński M, Leonowicz Z, Jasińska E. Identification of plant-leaf diseases using CNN and transfer-learning approach. Electronics. 2021;10(12):1388. doi:10.3390/electronics10121388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

75. Rajasekar D, Moorthy V, Rajadurai P, Ravikumar S. From leaf to harvest: achieving sustainable agriculture through advanced disease prediction with DBN-EKELM. J Sci Food Agric. 2024;104(13):8306–20. doi:10.1002/jsfa.13665. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Vashisth A, Gupta S, Krishnan P, Lama A, Prasad S, Aravind KS. Weather based multistage wheat yield prediction using machine learning. Mausam. 2024;75(3):639–48. doi:10.54302/mausam.v75i3.5606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

77. Chaiyana A, Khiripet N, Ninsawat S, Siriwan W, Shanmugam MS, Virdis SGP. Mapping and predicting cassava mosaic disease outbreaks using earth observation and meteorological data-driven approaches. Remote Sens Appl Soc Environ. 2024;35(2):101231. doi:10.1016/j.rsase.2024.101231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

78. Reddy PK, Reddy RA, Reddy MA, Teja KS, Rohith K, Rahul K. Detection of weeds by using machine learning. In: Advances in engineering research/advances in engineering research (ICETE 2023). Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Atlantis Press; 2023. p. 882–92. doi:10.2991/978-94-6463-252-1_89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

79. Ahmed S, Revolinski SR, Maughan PW, Savic M, Kalin J, Burke IC. Deep learning-based detection and quantification of weed seed mixtures. Weed Sci. 2024;72(6):655–63. doi:10.1017/wsc.2024.60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

80. Cui Y, Yang Y, Xia Y, Li Y, Feng Z, Liu S, et al. An efficient weed detection method using latent diffusion transformer for enhanced agricultural image analysis and mobile deployment. Plants. 2024;13(22):3192. doi:10.3390/plants13223192. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Li J, Chen D, Yin X, Li Z. Performance evaluation of semi-supervised learning frameworks for multi-class weed detection. Front Plant Sci. 2024;15:1396568. doi:10.3389/fpls.2024.1396568. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

82. Islam N, Rashid MM, Wibowo S, Xu CY, Morshed A, Wasimi SA, et al. Early weed detection using image processing and machine learning techniques in an Australian chilli farm. Agriculture. 2021;11(5):387. doi:10.3390/agriculture11050387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

83. Nikolova PD, Evstatiev BI, Atanasov AZ, Atanasov AI. Evaluation of weed infestations in row crops using aerial RGB imaging and deep learning. Agriculture. 2025;15(4):418. doi:10.3390/agriculture15040418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

84. Moldvai L, Mesterházi PÁ, Teschner G, Nyéki A. Weed detection and classification with computer vision using a limited image dataset. Appl Sci. 2024;14(11):4839. doi:10.3390/app14114839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

85. Agyeman BT, Liu J, Shah SL. Semi-centralized multi-agent RL for irrigation scheduling. IFAC-PapersOnLine. 2024;58(14):145–50. doi:10.1016/j.ifacol.2024.08.328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

86. Ye Z, Yin S, Cao Y, Wang Y. AI-driven optimization of agricultural water management for enhanced sustainability. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):25721. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-76915-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

87. Goap A, Sharma D, Shukla AK, Rama Krishna C. An IoT based smart irrigation management system using Machine learning and open source technologies. Comput Electron Agric. 2018;155(1):41–9. doi:10.1016/j.compag.2018.09.040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

88. Tace Y, Tabaa M, Elfilali S, Leghris C, Bensag H, Renault E. Smart irrigation system based on IoT and machine learning. Energy Rep. 2022;8(1):1025–36. doi:10.1016/j.egyr.2022.07.088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

89. Jiménez AF, Ortiz BV, Bondesan L, Morata G, Damianidis D. Evaluation of two recurrent neural network methods for prediction of irrigation rate and timing. Trans ASABE. 2020;63(5):1327–48. doi:10.13031/trans.13765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

90. Abioye EA, Hensel O, Esau TJ, Elijah O, Abidin MSZ, Ayobami AS, et al. Precision irrigation management using machine learning and digital farming solutions. AgriEngineering. 2022;4(1):70–103. doi:10.3390/agriengineering4010006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

91. Razfar N, True J, Bassiouny R, Venkatesh V, Kashef R. Weed detection in soybean crops using custom lightweight deep learning models. J Agric Food Res. 2022;8(3):100308. doi:10.1016/j.jafr.2022.100308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

92. Kong X, Liu T, Chen X, Lian P, Zhai D, Li A, et al. Exploring the semi-supervised learning for weed detection in wheat. Crop Prot. 2024;184(9):106823. doi:10.1016/j.cropro.2024.106823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

93. Mohammed H, Tannouche A, Ounejjar Y. Weed detection in pea cultivation with the faster RCNN ResNet 50 convolutional neural network. Rev D’intelligence Artif. 2022;36(1):13–8. doi:10.18280/ria.360102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

94. Cravero A, Pardo S, Sepúlveda S, Muñoz L. Challenges to use machine learning in agricultural big data: a systematic literature review. Agronomy. 2022;12(3):748. doi:10.3390/agronomy12030748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

95. Mohan RNVJ, Rayanoothala PS, Sree RP. Next-gen agriculture: integrating AI and XAI for precision crop yield predictions. Front Plant Sci. 2025;15:1451607. doi:10.3389/fpls.2024.1451607. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

96. Yamamoto K, Togami T, Yamaguchi N. Super-resolution of plant disease images for the acceleration of image-based phenotyping and vigor diagnosis in agriculture. Sensors. 2017;17(11):2557. doi:10.3390/s17112557. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

97. Tian Q, Zhao G, Yan C, Yao L, Qu J, Yin L, et al. Enhancing practicality of deep learning for crop disease identification under field conditions: insights from model evaluation and crop-specific approaches. Pest Manag Sci. 2024;80(11):5864–75. doi:10.1002/ps.8317. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

98. Joshi A, Guevara D, Earles M. Standardizing and centralizing datasets for efficient training of agricultural deep learning models. Plant Phenomics. 2023;5(9):84. doi:10.34133/plantphenomics.0084. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

99. Padarian J, Minasny B, McBratney AB. Machine learning and soil sciences: a review aided by machine learning tools. Soil. 2020;6(1):35–52. doi:10.5194/soil-6-35-2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

100. Araújo SO, Peres RS, Ramalho JC, Lidon F, Barata J. Machine learning applications in agriculture: current trends, challenges, and future perspectives. Agronomy. 2023;13(12):2976. doi:10.3390/agronomy13122976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

101. Benos L, Tagarakis AC, Dolias G, Berruto R, Kateris D, Bochtis D. Machine learning in agriculture: a comprehensive updated review. Sensors. 2021;21(11):3758. doi:10.3390/s21113758. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

102. Muruganantham P, Wibowo S, Grandhi S, Samrat NH, Islam N. A systematic literature review on crop yield prediction with deep learning and remote sensing. Remote Sens. 2022;14(9):1990. doi:10.3390/rs14091990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

103. Panagos P, Ballabio C, Poesen J, Lugato E, Scarpa S, Montanarella L, et al. A soil erosion indicator for supporting agricultural, environmental and climate policies in the European union. Remote Sens. 2020;12(9):1365. doi:10.3390/rs12091365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

104. Rastogi M, Kolur SM, Burud A, Sadineni T, Sekhar M, Kumar R, et al. Advancing water conservation techniques in agriculture for sustainable resource management: a review. J Geogr Environ Earth Sci Int. 2024;28(3):41–53. doi:10.9734/jgeesi/2024/v28i3755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

105. Bayih AZ, Morales J, Assabie Y, de By RA. Utilization of internet of things and wireless sensor networks for sustainable smallholder agriculture. Sensors. 2022;22(9):3273. doi:10.3390/s22093273. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools