Open Access

Open Access

SHORT COMMUNICATION

A Gel-Free Budget-Friendly Approach to GFP-Tagged Viruses Quantification in Plant Samples

Department of Biochemistry, Chemistry, Physics and Forensic Science, Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières, Trois-Rivières, Québec, G9A 5H9, Canada

* Corresponding Author: Hugo Germain. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Multi-Level Mechanisms in Plant-Pathogen Interactions)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(5), 1497-1504. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.063974

Received 31 January 2025; Accepted 03 April 2025; Issue published 29 May 2025

Abstract

Viral diseases are an important threat to crop yield, as they are responsible for losses greater than US$30 billion annually. Thus, understanding the dynamics of virus propagation within plant cells is essential for devising effective control strategies. However, viruses are complex to propagate and quantify. Existing methodologies for viral quantification tend to be expensive and time-consuming. Here, we present a rapid cost-effective approach to quantify viral propagation using an engineered virus expressing a fluorescent reporter. Using a microplate reader, we measured viral protein levels and we validated our findings through comparison by western blot analysis of viral coat protein, the most common approach to quantify viral titer. Our proposed methodology provides a practical and accessible approach to studying virus-host interactions and could contribute to enhancing our understanding of plant virology.Keywords

While many plant pathogens can be observed using a light microscope or cultured on Petri dishes, viruses can only be seen by an electron microscope [1]. In the past century, hundreds of plant viruses have been characterized, many known to be pathogens for crop plants. Viruses are classified in different families according to presence or absence of the capsid and the nature of their genetic material [2].

In recent years, viruses have also been harnessed as molecular tools to decipher mechanisms of plant immunity and plant resistance [3,4]. Plantago asiatica Mosaic Virus (PlAMV) is a prominent model for plant virologists. Belonging to the Potexvirus genus within the Alphaflexiviridae family, PlAMV is characterized by a proteinaceous capsid and a positive-sense RNA genome. Initially identified in Plantago asiatica plants in Russia [5], PlAMV has since been observed infecting edible lilies [6–9], plants of Nicotiana benthamiana and Arabidopsis thaliana [10,11]. Unlike many RNA viruses, PlAMV exhibits a slower systemic movement due its triple gene block (TGB) a hallmark of Potexviruses [12], making it a model for investigating viral and host interactions [8,13,14]. However, despite its significance in plant virology, rapid detection and quantification of PlAMV, which would facilitate studies on viral-host interactions, has not yet been achieved.

Current studies involving viral quantification rely on total viral particle count by Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA). For example, Edwards et al. (1985) developed a Protein A sandwich ELISA (PAS-ELISA), method for detecting viruses in plants. This method uses protein A in two distinct applications to create antibody-antigen-antibody layers, successfully identifying homologous virus isolates and detecting prune dwarf virus in 18%–36% of tested Prunus avium seeds [15]. In 2000, Seo et al. introduced a real-time RT-PCR method to quantify two orchid viruses, Cymbidium Mosaic Virus (CymMV) and Odontoglossum Ringspot Virus (ORSV), using four synthesized probes targeting the coat protein (CP) encoding genes. This method provided a sensitive, high-throughput, and rapid approach to plant virus detection [16–19]. Despite its high sensitivity, RT-PCR can be challenging for virus detection and quantification due to the presence of diverse variants, which can lead to mis-priming. Another common approach involves quantifying viral protein expression through western blot analysis, which is a semi-quantitative approach to viral detection and requires synthesizing viral-specific antibodies [20,21]. In recent years, the use of fluorescent proteins in plant-microbe interaction studies has significantly advanced image-based analysis of viral infection processes. For instance, Pasin et al. (2014) developed a microtiter quantification method for leaf discs using enhanced fluorescent proteins, which enabled rapid viral quantification [22]. However, such a method faces a challenge, viruses like PlAMV often produce uneven infection patterns, complicating the quantification process, as the fluorescence intensity may not accurately reflect the total viral load or distribution, leading to inconsistent results.

In this study, we present a viral quantification method utilizing a fluorescent marker to measure PlAMV levels with a microplate reader. Compared to western blot analysis, this approach offers a faster workflow, delivering results in just 30 min, compared to the 8-h process required for protein extraction, gel migration, and detection. Unlike western blotting and ELISA, this method eliminates the need for expensive and unstable antibodies, significantly reducing costs. Furthermore, compared to leaf disk-based methods, it provides more uniform and reproducible quantification, over-coming variability caused by uneven viral spread in infected tissues. Our approach demonstrates a clear dose-dependent response, offers linear quantitation, and can be adapted to study various plant viruses, making it a cost-effective and accessible alternative for virus-host interaction studies.

2.1 Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

Seeds of Nicotiana benthamiana and Arabidopsis thaliana were stratified at 4°C for 4 days to break dormancy before sowing them on a peat-based commercial potting medium (Seeds of Nicotiana benthamiana were obtained from the laboratory of Dr. Peter Moffett at the Université de Sherbrooke, while seeds of Arabidopsis thaliana were sourced from Prof. Xin Li at the University of British Columbia). Germinated seedlings were transplanted into individual pots containing Agromix soil. The plants were grown in a controlled growth chamber set to a 14-h light/10-h dark photoperiod at 23°C with 60% relative humidity, providing optimal conditions for growth and development.

Plants were watered prior to infection. 10 µL of clarified virion containing plant extract was applied to each leaf. The PlAMV vector was kindly provided by Dr. Peter Moffet, and developed by Yamaji et al. [11] as follows, A binary vector, pPlAMV-GFP, was constructed to express PlAMV fused with GFP. This vector was derived from pPlAMV-GFPΔCP, an infectious cDNA of PlAMV that encodes GFP but lacks the coat protein (CP), making it movement-deficient. To restore systemic movement, CP cDNA was fused to the foot-and-mouth disease virus (FMDV) 2A peptide sequence at its 5′ terminus and inserted between GFP and the 3′-untranslated region of pPlAMV-GFPΔCP at the SpeI restriction site. This was achieved using primers containing SpeI sites. This modification enabled the expression of a GFP-2A–CP fusion protein under the control of the CP sub-genomic promoter. The FMDV 2A sequence allows co-translational cleavage, leading to the partial processing of the GFP-2A–CP fusion and the production of functional CP in planta. This restored CP production enables the systemic spread of PlAMV-GFP in infected plants. Inoculation was performed via gentle rub inoculation using a 1 mL pipette tip after sprinkling with silicon carbide (Aldrich Chemistry, #378097, St-Louis, MO, USA) [23]. After 5-min, infected leaves were rinsed to remove excess silicon carbide particles. The plants were maintained at 23°C for 14 days and viral replication was monitored using a UV lamp. At designated time points, infected leaves were homogenized in phosphate buffer (100 mM at pH 7.0) containing 2% β-mercaptoethanol (Fisher Bioreagents, #BP176, Ottawa, ON, Canada) using a Tissue LyserII (Qiagen, Toronto, ON, Canada) at a frequency of 30 cycles/sec for 2 min. The resulting plant mixture was centrifuged at 16,600× g for 10 min at room temperature. 60 µL of the supernatant was transferred in a 96-well plate and analyzed for GFP fluorescence using a microplate analyzer (Synergy H1, Biotek, Santa Clara, CA, USA) at the excitation wavelength of 485 nm and an emission wavelength of 528 nm. GFP signal was normalized with uninfected tissue signals to account for background fluorescence. The proteins were analyzed by a western blot analysis using the standard protocol [24] using PlAMV capture antibodies (Agdia, #CAB91500/0500, Elkhart, IN, USA) at 1:200 dilution, and the bands were quantified using Image Lab (6.0.1, Bio-Rad). The statistical tests were performed using R Studio (Tidyverse, Pathwork, readxl, R.4.3.1, Posit) after.

3.1 Viral protein can be quantified by using reporter fluorescent protein

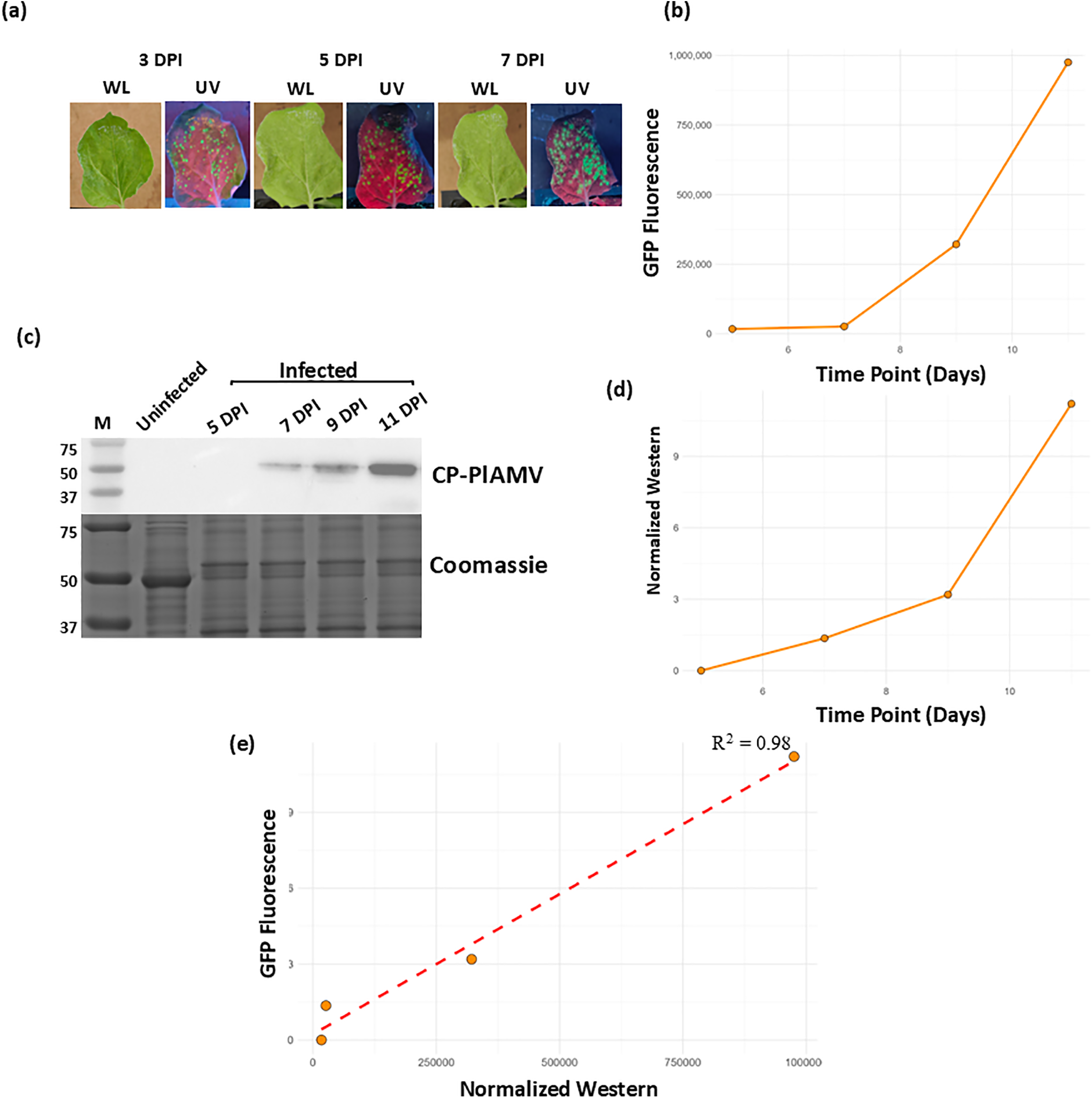

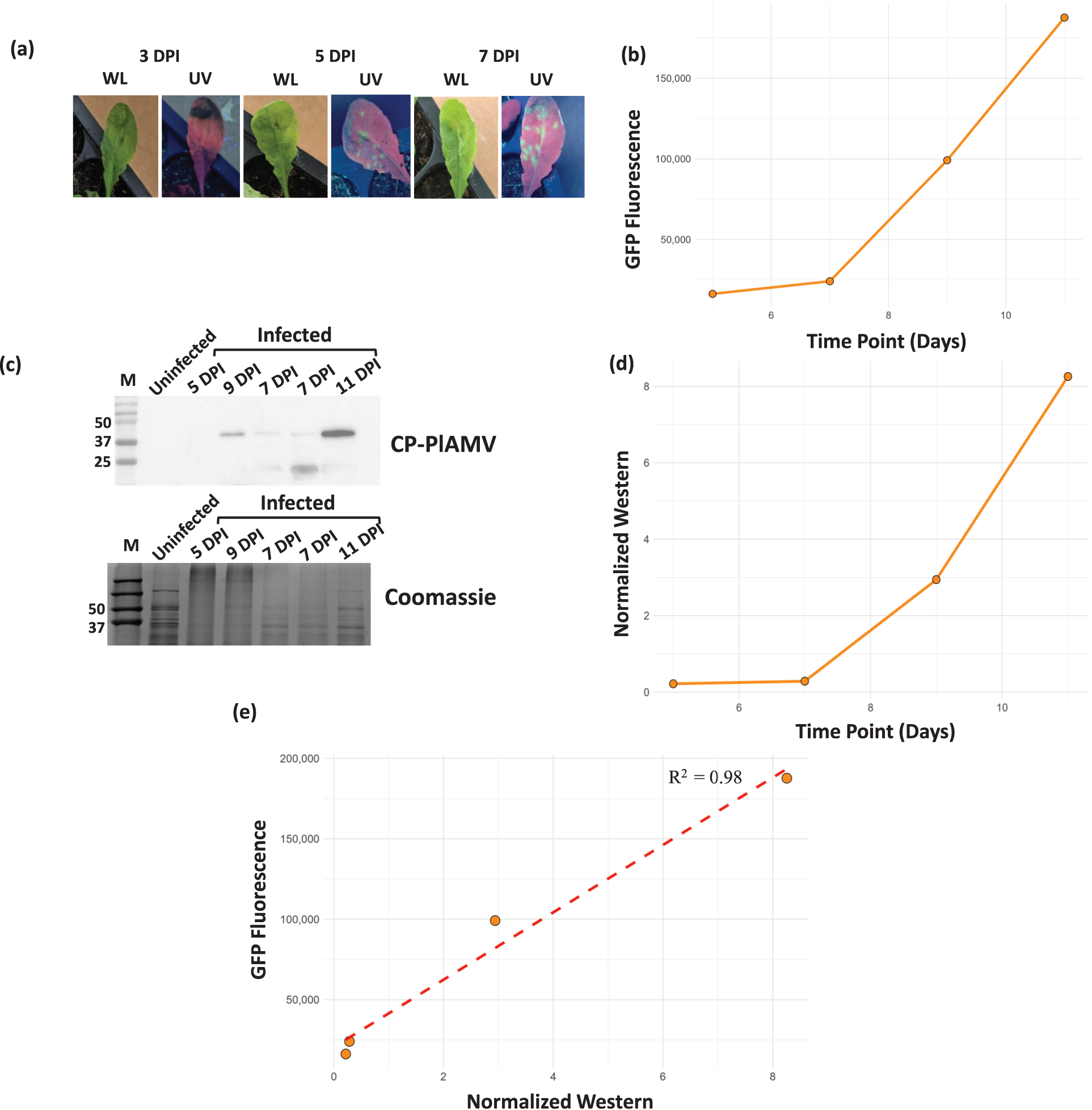

To establish our protocol, we employed two well characterized PlAMV susceptible model plants, Nicotiana benthamiana and Arabidopsis thaliana (Figs. 1 and A1) [9,10,25,26]. Viral progression was monitored throughout the experiment using a UV lamp, with Nicotiana exhibiting an initial visible fluorescence at 3 DPI (Fig. 2a) and Arabidopsis at 5 DPI (Fig. A1a). Leaf samples were collected at 5, 7, 9, and 11 DPI, and clarified leaf extracts were analyzed using microplate fluorescence assay to measure the viral reporter GFP (Fig. 2b) and by western blot using PlAMV coat protein antibodies to measure an intrinsic viral protein (Fig. 2c). A band corresponding to PlAMV coat protein was detected from day 7 and increased at day 9 and 11 (Fig. 2c,d). We also performed a Pearson’s correlation analysis to observe the trend between GFP quantitation using the microtiter plate and the western. We observed a positive correlation with an R2 value of 0.98 (Fig. 2e) and, demonstrating that the western analysis and the GFP quantification (microtiter plate) are positively correlated, we observed similar results for both plant species (Figs. 2 and A1).

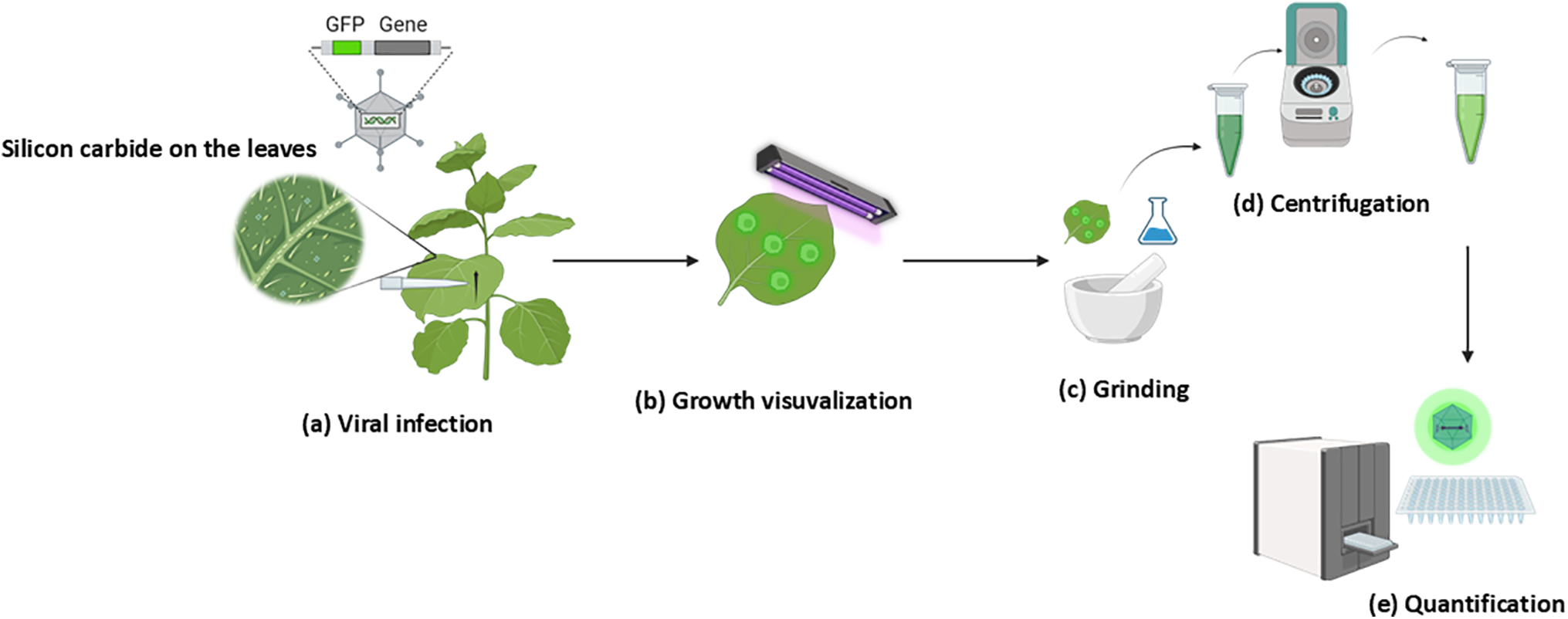

Figure 1: Workflow illustrating the quantification of virus titer using fluorescent protein. (a) Infection of plants with PlAMV_GFP virions via rub inoculation technique. (b) Monitoring of viral growth during the incubation period using UV light. (c) Extraction of viral particles from infected leaves by grinding in the buffer. (d) Separation of viral particles and plant tissue by centrifugation. (e) Quantification of virus titer by measuring GFP fluorescence using a microplate reader

Figure 2: Validating the protocol for viral analysis in N. benthamiana. (a) Images of PlAMV-infected Nicotiana leaves under white light (WL) and UV light (UV) at 3, 5, and 7 days post-infection. The green speckles in the UV panels indicate GFP fluorescence. (b) Graph indicating the observed fluorescence in the infected Nicotiana samples at 5, 7, 9, and 11 DPI. (c) Western blot was performed on the supernatant of ground plant tissue at 5, 7, 9, and 11 DPI using an anti-coat protein antibody, the Coomassie staining indicates the loading of the proteins in all samples. (d) Graph indicating the western band intensity of the infected Nicotiana samples at 5, 7, 9, and 11 DPI. (e) Scatter plot indicating the correlation between the band intensity of western blot performed against the antibodies of CP-PlAMV and the quantified GFP fluorescence of virus titer

Our study introduces a florescence-based microplate assay for rapid and quantitative measurement of viral titers in plants, circumventing labor-intensive traditional methods. Using Nicotiana benthamiana and Arabidopsis thaliana as our model systems, we harnessed a fluorescently tagged virus to fine-tune this approach. Unlike established techniques such as real-time qPCR, PCR, and leaf-discs fluorescence quantification [22,27–29], which often requires more complex preparations and longer processing times, our method leverages the sensitivity and rapid throughput of microplate readers. These not only facilitate quicker assessments but also yield reliable results that correlate well with western blot analysis, using antibodies against the PlAMV coat protein to confirm viral replication at the protein level. To validate the robustness of this method, we extended our analysis to Arabidopsis thaliana, a species with distinct genetic and physiological characteristics from N. benthamiana and also susceptible for PlAMV [1,2]. In both species, fluorescence measurements from infected samples were normalized against non-infected controls, effectively minimizing the risk of false positives due to background autofluorescence or non-specific fluorescence signals. The results demonstrated a strong correlation between fluorescence intensity and viral protein accumulation, as confirmed by Western blot analysis targeting the PlAMV coat protein. This confirms the accuracy of our method in detecting viral replication dynamics across different plant hosts. By integrating a fluorescent gene with microplate reader technology, our approach not only accelerates the research process but also enhances its affordability and accuracy, offering substantial promise for broad application in plant virology research. In conclusion, our study presents a novel approach for quantifying viral titer in plants using GFP tagged viruses, offering rapid, affordable, and reliable results compared to conventional techniques thatcould provide valuable insights into PlAMV infection dynamics. While our fluorescence-based microplate assay enables high-throughput screening of plant susceptibility across large plant populations, it provides limited resolution into virus-induced subcellular remodeling. By integrating our approach with the confocal microscopy methodology developed by Adhab and Schoelz (2019) [30], which interrogates viral defense evasion mechanisms at the cellular level (e.g., suppression of RNA silencing via pathogen effectors), we can bridge this gap by providing mechanistic insights into host-pathogen interactions and ultimately offering a more comprehensive perspective on plant-virus coevolution. This technique shows a potential for broader application in plant virology research to better understand the interactions and effects of PlAMV or other FP-tagged virus.

Acknowledgement: We are very grateful to Prof. Peter Moffet for his generous provision of PlAMV stocks.

Funding Statement: Funding from Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada award number RGPIN/4002-2020.

Author Contributions: Study conception and design: Hugo Germain, Rohith Grandhi; data collection: Rohith Grandhi, Aditi Balasubramani; analysis and interpretation of results: Rohith Grandhi; draft manuscript preparation: Rohith Grandhi. Mélodie B. Plourde assisted with manuscript editing, data interpretation, and research support. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| GFP | Green Fluorescent Protein |

| PlAMV | Plantago asiatica Mosaic Virus |

| CP | Coat Protien |

| WL | White Light |

| UV Light | Ultraviolet Light |

| FMDV | Foot and Mouth Disease Virus |

| CymMV | Cymbidium Mosaic Virus |

| ORSV | Odontoglossum Ringspot Virus |

| DPI | Days post-infection |

Appendix A

Figure A1: Validating the protocol for viral analysis in A. thaliana. (a) Images of PlAMV-infected leaves under white light (WL) and UV light (UV) at 3, 5, and 7 days post-infection. The green speckles in the UV panels indicate GFP fluorescence. (b) Graph indicating the observed florescence in the infected Arabidopis samples at 5, 7, 9, and 11 DPI. (c) Western blot was performed on the supernatant of ground plant tissue at 5, 7, 9, and 11 DPI using an anti-coat protein antibody, the Coomassie staining indicates the loading of the proteins in all samples. (d) Graph indicating the western band intensity of the infected Arabidopsis samples at 5, 7, 9, and 11 DPI. (e) Scatter plot indicating the correlation between the band intensity of western blot performed against the antibodies of CP-PlAMV and the quantified GFP fluorescence of virus titer

References

1. Jeong J-J, Ju H-J, Noh J. A review of detection methods for the plant viruses. Res Plant Dis. 2014;20(3):173–81. doi:10.5423/RPD.2014.20.3.173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Fauquet CM, Mayo MA, Maniloff J, Desselberger U, Ball LA. Virus taxonomy. In: VIIIth report of the international committee on taxonomy of viruses. Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA: Academic Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

3. Deng Z, Ma L, Zhang P, Zhu H. Small RNAs participate in plant-virus interaction and their application in plant viral defense. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(2):696. doi:10.3390/ijms23020696. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Dodds PN, Rathjen JP. Plant immunity: towards an integrated view of plant-pathogen interactions. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11(8):539–48. doi:10.1038/nrg2812. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Kostin V. Some properties of the virus affecting Plantago asiatica L. Virusnye Bolezni Rastenij Dalnego Vostoka. 1976;25:205. [Google Scholar]

6. Komatsu K, Hammond J. Plantago asiatica mosaic virus: an emerging plant virus causing necrosis in lilies and a new model RNA virus for molecular research. Mol Plant Pathol. 2022;23(10):1401. doi:10.1111/mpp.13243. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Furuya M, Tanai S, Hamim I, Yamamoto Y, Abe H, Imai K, et al. Phylogenetic and population genetic analyses of plantago asiatica mosaic virus isolates reveal intraspecific diversification. J Gen Plant Pathol. 2023;89(4):224–37. doi:10.1007/s10327-023-01129-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Komatsu K, Hashimoto M, Maejima K, Shiraishi T, Neriya Y, Miura C, et al. A necrosis-inducing elicitor domain encoded by both symptomatic and asymptomatic Plantago asiatica mosaic virus isolates, whose expression is modulated by virus replication. Mol Plant-Microbe Interactions. 2011;24(4):408–20. doi:10.1094/MPMI-12-10-0279. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Neriya Y. Search for plant factors required for virus infection. J Gen Plant Pathol. 2024;90(6):374–5. doi:10.1007/s10327-024-01190-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Nakamura D, Minato N, Furuya M, Komatsu K, Fuji S-I. Long-term passages of Plantago asiatica mosaic virus alter virulence and multiplication in Nicotiana benthamiana plants. Arch Virol. 2024;169(1):9. doi:10.1007/s00705-023-05934-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Yamaji Y, Maejima K, Komatsu K, Shiraishi T, Okano Y, Himeno M, et al. Lectin-mediated resistance impairs plant virus infection at the cellular level. Plant Cell. 2012;24(2):778–93. doi:10.1105/tpc.111.093658. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Kim YJ, Maizel A, Chen X. Traffic into silence: endomembranes and post-transcriptional RNA silencing. EMBO J. 2014;33(9):968–80. doi:10.1002/embj.201387262. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Shinji H, Sasaki N, Hamim I, Itoh Y, Taku K, Hayashi Y, et al. Dynamin-related protein 2 interacts with the membrane-associated methyltransferase domain of plantago asiatica mosaic virus replicase and promotes viral replication. Virus Res. 2023;331:199128. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

14. Weber PH, Bujarski JJ. Multiple functions of capsid proteins in (+) stranded RNA viruses during plant-virus interactions. Virus Res. 2015;196:140–9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

15. Edwards M, Cooper J. Plant virus detection using a new form of indirect ELISA. J Virol Methods. 1985;11(4):309–19. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

16. Eun AJC, Seoh M-L, Wong S-M. Simultaneous quantitation of two orchid viruses by the TaqMan® real-time RT-PCR. J Virol Methods. 2000;87(1–2):151–60. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

17. Chen L, Guo C, Yan C, Sun R, Li Y. Genetic diversity and phylogenetic characteristics of viruses in lily plants in Beijing. Front Microbiol. 2023;14:1127235. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

18. Xu L, Ming J. Development of a multiplex RT-PCR assay for simultaneous detection of Lily symptomless virus, Lily mottle virus, Cucumber mosaic virus, and Plantago asiatica mosaic virus in Lilies. Virol J. 2022;19(1):219. doi:10.1186/s12985-022-01947-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Lee H-J, Choi S, Cho I-S, Yoon J-Y, Jeong R-D. Development and application of a reverse transcription droplet digital PCR assay for detection and quantification of Plantago asiatica mosaic virus. Crop Prot. 2023;169:106255. doi:10.1016/j.cropro.2023.106255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Haider MS, Liu S, Ahmed W, Evans AA, Markham PG. Detection and relationship among begomoviruses from five different host plants, based on ELISA and Western Blot analysis. Pak J Zool. 2005;37(4):69. [Google Scholar]

21. Li R, Wisler G, Liu H-Y, Duffus J. Comparison of diagnostic techniques for detecting tomato infectious chlorosis virus. Plant Dis. 1998;82(1):84–8. doi:10.1094/PDIS.1998.82.1.84. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Pasin F, Kulasekaran S, Natale P, Simón-Mateo C, García JA. Rapid fluorescent reporter quantification by leaf disc analysis and its application in plant-virus studies. Plant Methods. 2014;10:1–12. doi:10.1186/1746-4811-10-22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Ma X, Zhou Y, Moffett P. Alterations in cellular RNA decapping dynamics affect tomato spotted wilt virus cap snatching and infection in Arabidopsis. New Phytologist. 2019;224(2):789–803. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

24. Taylor SC, Berkelman T, Yadav G, Hammond M. A defined methodology for reliable quantification of Western blot data. Mol Biotechnol. 2013;55:217–26. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

25. Brosseau C, El Oirdi M, Adurogbangba A, Ma X, Moffett P. Antiviral defense involves AGO4 in an Arabidopsis-potexvirus interaction. Mol Plant-Microbe Interactions. 2016;29(11):878–88. [Google Scholar]

26. Matsuo Y, Novianti F, Takehara M, Fukuhara T, Arie T, Komatsu K. Acibenzolar-S-methyl restricts infection of Nicotiana benthamiana by Plantago asiatica mosaic virus at two distinct stages. Mol Plant-Microbe Interactions. 2019;32(11):1475–86. [Google Scholar]

27. Kokkinos CD, Clark C. Real-time PCR assays for detection and quantification of sweetpotato viruses. Plant Dis. 2006;90(6):783–88. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

28. Ruiz-Ruiz S, Moreno P, Guerri J, Ambrós S. A real-time RT-PCR assay for detection and absolute quantitation of Citrus tristeza virus in different plant tissues. J Virol Methods. 2007;145(2):96–105. doi:10.1016/j.jviromet.2007.05.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Seal S, Coates D Foster GD, Taylor SC, editors. Detection and quantification of plant viruses by PCR. In: Foster GD, Taylor SC, editors. Plant virology protocols. Methods in molecular biologyTM. Humana Press; 1998. Vol. 81. p. 469–85. doi:10.1385/0-89603-385-6:469. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Adhab M, Schoelz JE, A novel assay based on confocal microscopy to test for pathogen silencing suppressor functions. In: Gassmann W, editor. Plant innate immunity. Methods in molecular biology. New York, NY: Humana. Vol. 1991. p. 33–42. doi:10.1007/978-1-4939-9458-8_4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools