Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Microbial Strategies for Enhancing Nickel Nanoparticle Detoxification in Plants to Mitigate Heavy Metal Stress

Sanya Institute of Nanjing Agriculture University, Jiangsu Collaborative Innovation Center for Modern Crop Production, Key Laboratory of Crop Physiology Ecology and Production Management, Nanjing Agricultural University, Nanjing, 211800, China

* Corresponding Author: Ganghua Li. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Metabolic Mechanisms of Plant Responses to Stress)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(5), 1367-1399. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.064632

Received 20 February 2025; Accepted 21 April 2025; Issue published 29 May 2025

Abstract

Soil naturally contains various heavy metals, however, their concentrations have reached toxic levels due to excessive agrochemical use and industrial activities. Heavy metals are persistent and non-biodegradable, causing environmental disruption and posing significant health hazards. Microbial-mediated remediation is a promising strategy to prevent heavy metal leaching and mobilization, facilitating their extraction and detoxification. Nickel (Ni), being a prevalent heavy metal pollutant, requires specific attention in remediation efforts. Plants have evolved defense mechanisms to cope with environmental stresses, including heavy metal toxicity, but such stress significantly reduces crop productivity. Beneficial microorganisms play a crucial role in enhancing plant yield and mitigating abiotic stress. The impact of heavy metal abiotic stress on plants’ growth and productivity requires thorough investigation. Bioremediation using Nickel nanoparticles (Ni NPs) offers an effective approach to mitigating environmental pollution. Microorganisms contribute to nanoparticle bioremediation by immobilizing metals or inducing the synthesis of remediating microbial enzymes. Understanding the interactions between microorganisms, contaminants, and nanoparticles (NPs) is essential for advancing bioremediation strategies. This review focuses on the role of Bacillus subtilis in the bioremediation of nickel nanoparticles to mitigate environmental pollution and associated health risks. Furthermore, sustainable approaches are necessary to minimize metal contamination in seeds. The current review discusses bacterial inoculation in enhancing heavy metal tolerance, plant signal transduction pathways, and the transition from molecular to genomic research in metal stress adaptation. Moreover, the inoculation of advantageous bacteria is crucial for preserving plants under severe mental stress. Different researchers develop a complex, vibrant relationship with plants through a series of events known as plant-microbe interactions. It increases metal stress resistance through the creation of phytohormones. In general, the defensive responses of plants to heavy metal stress, mediated by microbial inoculation require further in-depth research. Further studies should explore the detoxification mechanism of nickel through bioremediation to develop more effective and sustainable remediation strategies.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Nickel (Ni) is one of the most hazardous environmental pollutants among the 23 identified metal contaminants [1]. Although Ni is a natural component of water and soil, its concentration in unpolluted environments typically remains below 100 mg kg−1 in soil and 0.005 mg L−1 in surface water [2]. However, anthropogenic activities such as industrial emissions, mining, smelting, and excessive use of Ni-containing fertilizers and pesticides have significantly contributed to its accumulation in the environment. The United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA, 1997) reported that approximately 10 million people worldwide suffer from health complications due to heavy metal-contaminated soils [3]. Industries release untreated toxic chemicals, including fertilizers, herbicides, medicines, chlorinated phenols, insecticides, petrochemicals, different dyes, and toxic heavy metals into the environment. These pollutants can interact and even form more toxic compounds, exacerbating environmental contamination. Heavy metals are particularly persistent and non-biodegradable, posing severe ecological and human health risks [4]. Their long-term accumulation in soil and water systems has intensified in recent years, raising significant concerns about ecosystem stability and public health [5]. Consequently, effective and sustainable management strategies are essential for environmental protection.

Several physical and chemical remediation techniques, including oxidation, incineration, soil washing, aeration, and surface soil replacement, have been employed for heavy metal removal [3]. However, these methods are often costly and environmentally unsustainable due to their high energy demands and the generation of secondary pollutants [6]. In contrast, bioremediation, which utilizes plants and microorganisms to detoxify contaminants, has emerged as an eco-friendly and cost-effective alternative for remediating heavy metal-contaminated soils [3]. This approach offers selective metal removal, operates efficiently under ambient conditions, and ensures long-term sustainability. Microorganisms play a crucial role in Ni detoxification by transforming, immobilizing, or sequestering heavy metals through various biochemical mechanisms [6,7]. Microbial-assisted phytoremediation, combined with the application of nanoparticles, has gained attention as an innovative strategy to enhance the efficiency of heavy metal bioremediation. Nanoparticles can improve microbial metal tolerance, facilitate Ni immobilization, and promote plant-microbe interactions for more effective remediation. Nanoparticles can improve microbial metal tolerance, facilitate Ni immobilization, and promote plant-microbe interactions for more effective remediation.

Despite the growing interest in microbial-assisted bioremediation, there is still a knowledge gap in understanding the precise mechanisms by which microorganisms interact with Ni nanoparticles to enhance plant detoxification. This review provides a comprehensive analysis of microbial strategies for enhancing Ni nanoparticle detoxification in plants, focusing on the role of Bacillus subtilis in improving plant resilience under heavy metal stress. Special attention is given to the microbe-mediated enhancement of plant tolerance mechanisms, including phytohormone production, stress signaling pathways, and transduction networks. Furthermore, the impact of microbial inoculation on Ni uptake and detoxification in seeds is critically examined. By bridging molecular-level insights with applied remediation strategies, this review highlights the potential of microbial-assisted bioremediation as a sustainable approach to reducing Ni toxicity in agricultural ecosystems.

2 Expected Discharge of Contaminates in Agricultural Ecosystem

Agricultural soil is a valuable natural resource that must be managed sustainably to maintain productivity and environmental quality. However, increasing industrial activities and the indiscriminate use of agrochemicals have led to severe contamination of agricultural soils [8]. Approximately more than 650,000 locations across the European Union are estimated to be affected by soil pollution [9]. Both natural and anthropogenic sources contribute to heavy metal contamination in agricultural ecosystems, with mining, industrial waste, and farming activities being the primary contributors [6]. Several processes lead to heavy metal accumulation in soil, including surface runoff from mining tailings [10], excessive application of pesticides and fertilizers [11], and irrigation with contaminated water sources [12]. In addition, industrial activities, mining, extraction, transportation, and manufacturing, release heavy metal particles into the atmosphere, which eventually deposit onto soil surfaces through air deposition [13]. Notably, some studies indicated that the geological parent material of the soil itself plays a crucial role in determining soil heavy metal concentration (SHMC) [6]. Thus, more investigation is required to evaluate whether incorporating pollution sources and transport pathways as cofactors can enhance the accuracy of SHMC predictions.

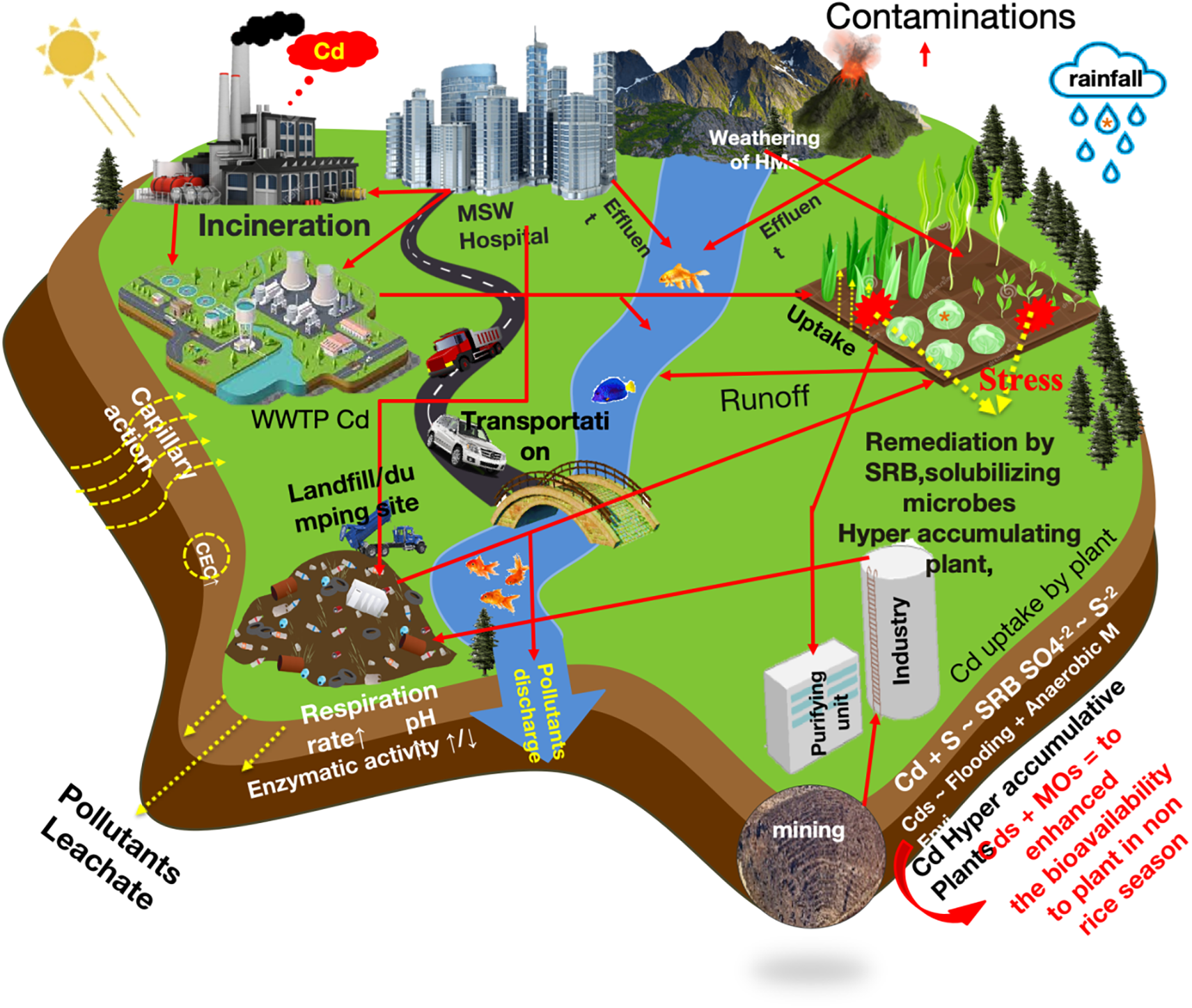

According to the United States Geological Survey (USGS), approximately one billion pounds of pesticides are applied annually in the United States alone [14]. Globally, pesticide usage exceeds four million tons per year, primarily to protect crops from pests and diseases worldwide [15]. While pesticides play a crucial role in agricultural productivity, they also pose significant environmental risks. Persistent pesticide residues disrupt soil microbial communities and alter soil biochemical processes [15]. A nationwide survey conducted by the US Geological Survey analyzed water samples from 38 streams across the United States and detected multiple pesticide pollutants, including chlorpyriphos, dieldrin, fipronil, atrazine, and glyphosate [16]. The persistence of these chemicals in soil and water bodies leads to long-term contamination, as many pesticides exhibit high environmental stability and bioaccumulate over time [17]. Organochlorine pesticides, in particular, are known for their toxicity and long-term environmental persistence, further exacerbating pollution risks [18]. Excessive and prolonged fertilizers application has become a significant concern, as fertilizers not only release nutrients into the soil but also introduce heavy metals (HMs) like lead (Pb), chromium (Cr), arsenic (As), and mercury (Hg), which naturally occur in soil but can reach toxic levels due to overuse [19]. One major issue associated with overfertilization is soil acidification, which lowers soil pH and enhances the bioavailability of heavy metals, making them more accessible for plant uptake [19]. Moreover, many commercial fertilizers contain trace levels of HMs originating from raw materials, adding to the overall HM burden in agricultural soils [20]. Excessive HMs interferes accumulation in soil disrupts key physiological and biochemical processes in plants, damages soil structure and microbial diversity, and ultimately hinders crop growth and productivity [21]. Severe cases of heavy metal toxicity lead to cellular and organelle damage, ultimately resulting in plant mortality. Animal farms and wastewater treatment plants contribute significantly to soil and water contamination by releasing a variety of toxic pollutants [22]. Although sewage sludge is often used in agriculture as a soil amendment due to its high nutrient content (e.g., nitrogen, potassium, iron, and manganese), it also contains hazardous compounds such as antibiotics, heavy metals, and toxic nanomaterials [8] (Fig. 1). The indiscriminate use of sewage sludge in agricultural systems increases the risk of soil contamination and introduces antibiotic-resistant genes into microbial communities, posing further environmental and public health concerns.

Figure 1: Expected discharge of contaminates in the agricultural ecosystem

Human health and agricultural ecosystems are closely interconnected, and the degradation of agricultural ecosystems poses a serious global threat. One of the primary pathways through which potentially toxic elements PTEs (potentially toxic elements) enter the human body is through the transfer of contaminants from soil into food crops, particularly fruits, vegetables, and grains, which are then consumed [23]. Once introduced into the soil through various industrial processes, trace elements are difficult to dilute or remove, leading to their gradual accumulation in soil ecosystems [24]. Moreover, contaminants present in polluted areas can influence the deposition of atmospheric depositions pollutants, further facilitating the transfer of trace metals from agricultural soils to crops [25]. As a result, PTEs (potentially toxic elements) can enter the human body through skin absorption, ingestion, or inhalation, subsequently accumulating in different tissues [26]. Industrial emissions, particularly metal-tainted exhaust, can contaminate plant-based such as fruits, vegetables, and cereals, thereby increasing dietary exposure to trace metals and posing health risks to nearby populations [27]. In some cases, pollution levels exceeded permissible limits, exacerbating the risks associated with heavy metal exposure [28]. Among these hazardous elements, lead (Pb) and cadmium (Cd) have particularly severe health implications [29]. Exposure to these metals has been linked to chromosomal abnormalities, impaired function of the lungs, spleen, and blood, as well as the potential carcinogenic effects [30]. The excessive accumulation of toxic substances in the human body can lead to various health issues, including cancer, digestive disorders, bone deterioration, and, in severe cases, fatal poisoning [31].

3 Effect of Nickel Toxicity on Soil Properties

The primary source of nickel pollution in soil is atmospheric deposition from industrial emission [32]. While the concentration of nickel in soils is significantly influenced by the parent rock, other factors such as pollution and soil-forming processes also impact its presence in surface soils [33]. Nickel concentrations in soil can vary widely depending on geology factors and anthropogenic input, typically ranging between 3 to 1000 parts per million [34]. Ni exists in soils in various inorganic mineral forms, where it may be complexed on inorganic cation exchange surfaces or absorbed onto organic cation surfaces [35]. Studies indicate that humic and fulvic acids are more mobile in soil solution than hydrated divalent cations, influencing nickel transport and availability [36]. The major Ni-containing minerals include pentlandite (nickel-iron sulfide), garnierite (nickel-magnesium silicate), and nickeliferous clays [37]. Nickel is most abundant in igneous rocks and found in lower concentrations in clays, limestones, sandstones, and shales [38].

Soil-forming processes can mobilize Ni during the weathering of Ni-containing soil minerals, increasing its solubility in soil fluids and facilitating its movement across the soil profile. Due to its mobility, Ni can migrate toward the root zone and be absorbed by plants, primarily in the form of Ni (H2O) 62+, posing potential risks to human health [39]. Kumar et al. [40] reported that the maximum permissible concentration of Ni in agricultural soils ranges from 20 to 60 mg kg–1, with a threshold of 75 to 150 mg kg−1 that indicates the need for remediation. While these values vary widely due to differences in soil properties and Ni speciation, they provide a reasonable guideline for assessing soil contamination [41]. The behaviour and bioavailability of Ni in biogeochemical process are influenced by several soil factors such as clay type and content, organic matter levels, pH, and redox potential. In acidic and oxidizing environments Ni mobility increases, while its interaction with organic matter and Fe-Mn hydroxides plays a crucial role in its retention and movement within the soil [42]. Its interaction with organic matter plays a crucial role in its retention and movement within the soil. While Ni strongly binds to organic matter, reducing its mobility in some cases, the presence of fulvic and humic acids, known for their high chelation capacity, can enhance Ni mobility in soils rich in organic matter [43]. Additionally, clay minerals like montmorillonite, which readily mobilize during weathering, can co-precipitate with Ni, affecting its bioavailability [44].

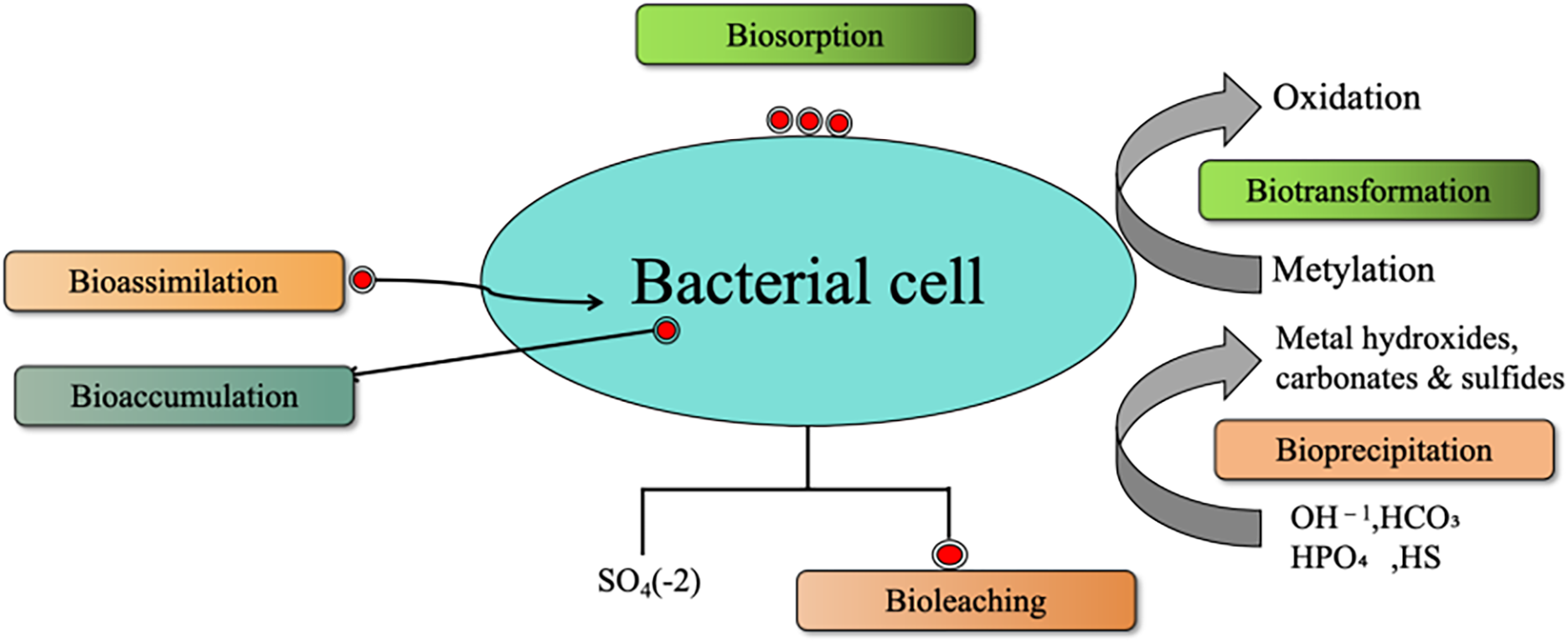

Pendias [45] reported that the amount of Ni adsorbed or complexed with Fe (hydro) oxides and minerals in soil is 100 to 170 mg Ni kg−1, while for Mn (hydro)oxides and minerals, the range is broader, from 39 to 4900 mg Ni kg−1. An extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) analysis of samples taken from an industrially polluted site in southern Italy revealed that Ni predominantly exists in a spinel-type geochemical form (trevorite; NiFe3+2O4), associated with magnetite and hematite [46]. Similarly, in a study of clayey paddy soils (Ultisols) from Taipei City, EXAFS analysis showed that Ni was incorporated into the MnO2 layer of lithiophorite, a finding consistent with the results of Manceau et al. [47]. The formation and availability of natural lithiophorite influence the incorporation of Ni into the MnO2 layer [48]. Ni adsorption on Fe-Mn hydroxides is pH-dependent due to changes in the surface charge of soil adsorbents. As soil pH decreases, Ni desorption increases, leading to a higher concentration of Ni in soil solution [41]. Bacteria can passively adsorb metals onto their cell surfaces or actively uptake and store metals via bioassimilation and bioaccumulation (Fig. 2). Additionally, microbial bioleaching, often mediated by sulfate (SO42−), facilitates the release of metal ions from minerals. Microorganisms also influence Ni toxicity and mobility through biotransformation processes, including oxidation, reduction, and methylation, which alter metal speciation. Another key mechanism is bioprecipitation, where bacteria induce the formation of metal hydroxides, carbonates, and sulfides, converting Ni into less bioavailable and less toxic forms. These microbial interactions are essential for metal detoxification and the bioremediation of contaminated soils.

Figure 2: Overview of different modes of interaction of bacteria with heavy metals in metal-contaminated soils

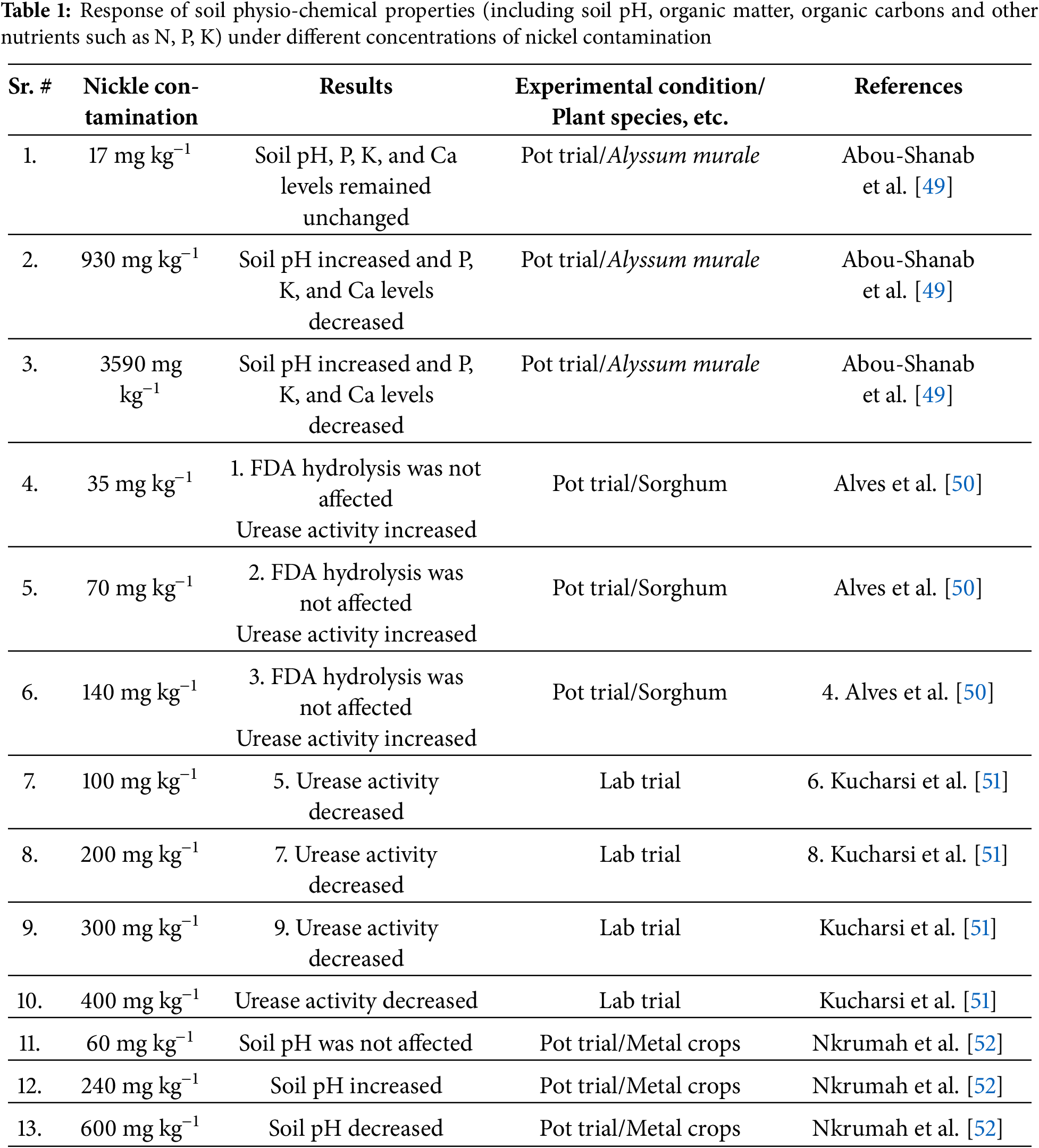

Several studies indicate that Ni contamination alters soil characteristics, particularly soil pH, enzyme activity, and nutrient availability (Table 1). At lower concentrations (e.g., 17 mg kg−1), soil pH and key nutrients such as phosphorus (P), potassium (K), and calcium (Ca) remain unchanged, as observed in a pot trial with Alyssum murale [49]. However, at higher Ni concentrations (930 and 3590 mg kg−1), soil pH increased, while P, K, and Ca levels decreased, likely due to metal-induced alterations in nutrient solubility. Enzymatic activity, particularly urease activity, is affected by Ni contamination. While Ni at 35–140 mg kg−1 did not impact FDA hydrolysis and increased urease activity in a Sorghum pot trial [50], higher Ni concentrations (100–400 mg kg−1) led to decreased urease activity in lab trials [51]. Additionally, studies on metal crops revealed that Ni contamination at moderate levels (60 mg kg−1) had no effect on soil pH, but at 240 mg kg−1, soil pH increased, whereas at 600 mg kg−1, soil pH decreased [52].

Overall Ni contamination in soil is influenced by both natural and anthropogenic factors, with its mobility and bioavailability governed by soil properties such as pH, organic matter, and mineral composition. The interaction of Ni with organic acids, clay minerals, and Fe-Mn oxides plays a crucial role in its speciation and transport within the soil profile. Additionally, microbial processes significantly impact Ni dynamics through adsorption, bioleaching, and bioprecipitation, affecting its toxicity and potential for remediation. Understanding these mechanisms is essential for assessing Ni contamination risks and developing effective soil management strategies.

4 Effect of Nickle Toxicity on Plants

4.1 Uptake and Transport of Nickel in Plants

The absorption of metals by plants is influenced by both the quantity and solubility of metals in the soil solution, as well as the specific plant species growing in those soils. According to Rooney et al. [53], the availability of Ni availability in plants is influenced by factors such as pH, organic matter content, iron and manganese oxide concentrations, and the overall absorption of Ni in the soil solution. Notably, soil pH plays a critical role in Ni absorption. At lower pH levels, Ni becomes more soluble and mobile, making toxicity symptoms more apparent in plants growing in acidic soils [54]. Additionally, Ni can form complexes with soil particles and easily exchange with crystals containing various nutrient elements in the soil solid phase. Its mobility and solubility increase as soil acidity rises [55].

Plants absorb Ni through their root systems via both active and passive processes. The form of Ni in the soil influences its uptake—ionic Ni is more readily absorbed by plant roots compared to its chelated or complex forms [56]. According to Chen et al. [57], factors such as the Ni form, soil pH, and the presence of organic matter and other ions in the soil or nutrient solution determine the bioavailability of Ni. Additionally, other cations like Cu2+ and Zn2+, utilize the same absorption mechanisms, thereby inhibiting Ni2+ uptake. Ni2+ is absorbed by plant roots through the cation transport system [58]. Ni2+ is absorbed by plant roots through the cation transport system, but its uptake and transfer from roots to shoots are inhibited by several metal ions, including Fe3+, Co2+, Ca2+, Mg2+, NH4+, K+, and Na+ [59]. Once absorbed by the roots, Ni is transported to the upper regions of plants via xylem tissues, following the transpiration stream [60]. Within the xylem, Ni2+ ions travel to the shoots in complexes formed with various several chelates [60]. High Ni mobility within the phloem has been observed, particularly during redistribution from older to younger leaves. Studies indicate that over 80% of Ni in young wheat plants is localized in vascular tissues, demonstrating its high mobility as a heavy metal [61]. Field studies show that in Alyssum serpyllifolium subsp. lusitanicum, Ni exists predominatly as a free hydrated cation (roughly 70%) or in complexes with carboxylic acids, such as citric acid (18%), in the xylem sap [43]. However, Centofanti et al. [62] found that the amount of organic ligands in xylem sap is insufficient to explain Ni chelation, indicating that the most Ni remains in its hydrated cation form. In contrast, Ni speciation in xylem and phloem differs significantly such as citrate primarily complexes Ni in the phloem of P. balgooyi [63]. Similarly, Deng et al. [64] reported that in Noccaea caerulescens, malate is the predominant organic acid, serving as the main Ni chelator for phloem. Carboxylic acids thus appear to enhance Ni transport through the phloem. Carboxylic acids thus appear to enhance Ni transport through the phloem. Deng et al. [64] also discovered that 89% of the Ni exported by N. caerulescens from old leaves is translocated upward to younger leaves, while only 11% moves downward to roots via the phloem. This suggests that the primary sinks for phloem-based Ni are young leaves and reproductive organs, with upward translocation being the predominant transport direction. Estrade et al. [65] further observed Ni isotope fractionation between leaves and flowers in A. murale, indicating Ni movement to leaves during early growth stages.

Nickel transport and binding in plants are facilitated by various ligands, including histidine, organic acids, nicotianamine, and different proteins [66]. These Ni-ligand play a crucial role in xylem-based Ni translocation. However, the high cation exchange capacity of xylem cells reduces Ni mobility, thereby restricting its movement from roots to shoots in the absence of chelation [66]. Consequently, a significant proportion of Ni (up to 50%) is retained in root system [67]. Seregin and Kozhevnikova [68] explained that Ni retention due to its sequestration at cation exchange sites within xylem parenchyma tissues. Moreover, Ni distribution varies across different plant organs, including leaves, stem, and seeds [69]. Within leaves, Ni diffusion varies cross cellular compartments. Brooks et al. [70] reported that Ni accumulates in vacuoles and cytoplasm fluid at higher, whereas lower amounts are found in ribosomes, mitochondria, and chloroplasts. In addition to its movement within vegetative tissues, Ni is transported to reproductive structures such as seed and fruit, through phloem tissues [61]. However, Ni distribution patterns vary significantly among plant species [71].

Nickel localization in seeds also differs across species. Some studies indicate that Ni is present in the seed coat [72], while others report the highest concentrations in the micropyle and epidermis, with the lowest levels in mesophyll cells of cotyledons. According to Cataldo et al. [67], Ni mobility in beans are particularly high. During vegetative growth, Ni is absorbed by the shoot and stored as a sink. However, as the plant matures, approximately 70% of the Ni stored in the shoot is remobilized to the seeds. Research also indicates that Ni is rapidly translocated from old to newly formed root sections and accumulates in developing leaves [61] highlighting its highly mobility in plant root systems. Overall, Ni uptake, transport, and distribution in plants are complex processes influenced by soil conditions, plant species, and the presence of competing ions. The mobility of Ni within the plant, facilitated by various ligands, plays a crucial role in its allocation to different tissues, including young leaves and reproductive organs. Understanding these mechanisms is essential for managing Ni toxicity in plants and optimizing its role as a micronutrient in crop production.

4.2 Impact of Nickel Toxicity on Plant Growth

Plant development is a crucial process for sustaining life on Earth. Several factors influence both the internal and external growth of plant, including the genotype of a plant species and the availability of mineral resources in soil and air [73]. While some metals are essential for plant growth and development, their affects largely relies on their concentration in the environment [74]. However, excessive levels of certain heavy metals can be toxic, leading to growth inhibition [74]. Ni, in particular, can severely affect plant growth and development when present in excessive amounts in the ecosystem [75]. Although Ni is not a major element required for plant growth, it is classified as a heavy metal due to its toxic properties [76]. The presence of Ni in the environment influences plant growth, and toxicity symptoms appear when Ni concentration exceeds 100 mg dm3 [75]. Since plant roots absorb nickel more readily than shoots, roots system are often used to assess the toxicity of several substances, including heavy metals [77]. Nickel toxicity leads to chlorosis and necrosis in plants by interfering with Fe absorption and metabolism [78]. Excessive Ni levels reduce agricultural productivity by decreasing biomass accumulation and total dry matter deposition, particularly in lower plants parts. Moreover, Ni toxicity disrupts chloroplast structure, inhibits seed germination and suppresses chlorophyll production. Studies have shown that as Ni concentration increases in plant tissues, the roots/shoot length ratio decreases [79].

Nickel stress also induces metabolic disorders, increases peroxidase activity in intracellular spaces and cell walls, and decreases the reduces cell walls flexibility by interacting with pectin. Peroxidases play a crucial role in the association and lignification of ferulic acid-containing polysaccharides. Additionally, Ni-induced toxicity inhibits cell division, suppressing cell growth [80]. Furthermore, Ni toxicity reduces lateral root formation in crops such as rice and maize, as Ni accumulates in endodermal and peri-cycle cells. Gajewska and Sklodowska [81] examined the effects of Ni nickel stress on wheat seedlings and reported that root growth was significantly reduced by 37% and 53% under 100- and 200-mM Ni stress, respectively. However, wheat seedlings treated with 10 mM Ni showed no significant reduction in root growth [82]. Similarly, when Brassica juncea was exposed to 100 mM Ni stress, root development decreased by 33% [83]. The findings highlight that Ni toxicity negatively impacts plant growth at cellular, organ, and whole-plant levels [84]. However, the precise mechanisms underlying Ni-induced effects on plant development remain unclear. Overall, increased Ni concentrations have detrimental effects on seed germination and subsequent plant.

4.3 Nickel Impact on Nutrient and Water Uptake

Ni is necessary for plant growth and development alongside macronutrients (K, Na, Ca, Mg) and micronutrients (Fe, Cu, Zn, and Mn) [85]. Ni shares similarities with Ca, Mg, Mn, Fe, Cu, and Zn, leading to competitive absorption by plants [57]. This competition inhibits the uptake and transport of these essential nutrients, resulting in nutrient deficiencies. The disruption of physiological and biochemical processes due to nutrient imbalances ultimately leads to toxicity and cell death [82]. Excess Ni can also displace calcium ions from essential binding sites in the oxygen-evolving complex and replace magnesium in chlorophyll molecules [86]. This substitution impairs electron transport in Photosystem II (PSII) significantly reducing energy availability for food production. As a result, plants experience nutrient deficiencies, leading to poor growth and development. Muhammad et al. [87] reported that Ni toxicity disturbs the nutrient balance in plants and significantly reduces manganese and copper uptake.

However, some plants, such as rice compensate for the adverse effects of Ni toxicity by increasing calcium absorption under high Ni concentrations [88]. Despite this adaptation, Ni poisoning severely reduces magnesium (Mg) and iron (Fe) uptake. Since Mg is a critical component of chlorophyll, reduced Mg availability leads to impaired seedling growth and lower final yields. This nutrient imbalance triggers secondary effects, including stunted growth, impaired physiological functions, reduced chlorophyll synthesis, decreased enzyme activity involved in transpiration and photosynthesis, and ultimately lower productivity [89]. Additionally, magnesium deficiency under Ni stress leads to chlorophyll degradation, which results in leaf chlorosis and necrosis [89].

5 Nickel Impact on Plant Photosynthesis

Nickel toxicity has a detrimental effect on the photosynthetic activity in plants, leading to chlorosis. Elevated concentrations of Ni damage mesophyll and epidermis cells [90], injure thylakoid membrane [91], reduce grain size [92], and decrease the number of photosynthetic pigments [93]. Excess Ni also lowers chlorophyll levels, which directly suppressed photosynthesis [94]. For instance, app exposure to 0.025 mM Ni stress resulted in a significant reduction in chlorophyll content, approximately 47% [95]. Baccouch et al. [96] reported a 50% and 70% decrease in chlorophyll levels when Ni concentration increased from 20 to 100 μM. Ni stress has also been shown to significantly reduce photosynthetic pigments in black gram and sunflower [97,98]. Uruç et al. [98] subjected wheat plants to 0, 25, and 50 g of Ni per litre and observed that increasing Ni concentrations led to a decline in chlorophyll content. Comparable findings were reported by Singh and Pandey [12], who concluded that elevated Ni levels drastically reduce chlorophyll content in lettuce plants. The decrease in the photosynthetic pigments consequently leads to a reduction in photosynthesis, resulting in chlorosis and ultimately impairing overall plant growth. Since photosynthates are primarily produced through photosynthesis, Ni stress not only slows down photosynthesis activity but also affects gas exchange efficiency [60]. Research by Krupa and Baszynski [99] has shown that Ni toxicity decreases the rate of transpiration and water-use efficiency in various plant species. By altering K+ fluxes across cell membranes, toxic Ni concentrations inhibit stomatal opening, thereby restricting gas exchange. Reduced stomatal conductance significantly slows down photosynthesis. However, Ni toxicity affects more than just stomatal regulation; it also disrupts multiple metabolic pathways, further suppressing photosynthetic activity [100]. Ni toxicity alters chloroplast structure, inhibits chlorophyll biosynthesis [68], disrupts the electron transport chain [101], slows down the Calvin cycle, increases in stomatal closure, and ultimately reduces photosynthesis [102].

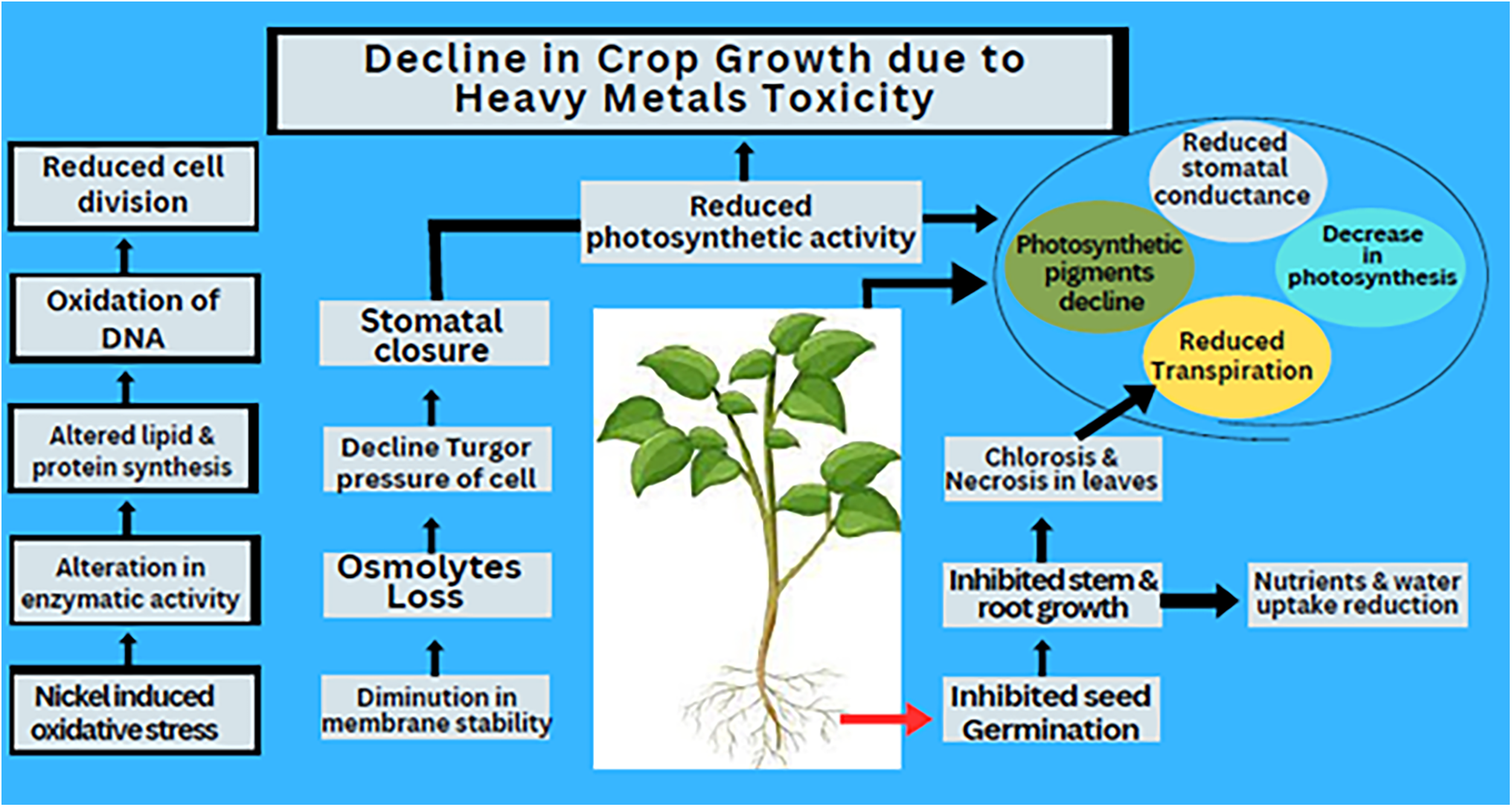

Furthermore, Molas [92] reported that Ni stress causes a significant decline in chloroplast size, thylakoid membrane integrity, and lipid composition in the chloroplast membranes of Brassica oleracea. The extent of Ni-induced physiological damage depends on the Ni concentration in the growth medium. Due to its inhibitory effects on both light-dependent and light-independent reactions, Ni toxicity lowers the overall rate of photosynthesis. Specifically, it disrupts electron transport within photosystem-II [99]. According to Veeranjaneyulu and Das [103], Ni significantly reduces plastocyanin and ferredoxin levels in the thylakoid membrane. Additionally, Ni interferes with key enzymes involved in the Calvin cycle, further slowing down the rate of photosynthetic activity [102]. As a result, the decreased activity of these enzymes leads to an accumulation of ATP and NDPH, which raises the pH of the thylakoid membranes and inhibits PS-II activity [99]. Thus, the decline in photosynthesis caused by Ni toxicity is not attributed to a single factor but rather results from multiple interacting mechanisms. These include the harmful effect of Ni on the electron transport chain, reduced enzymatic activity related to photosynthesis, and impaired chlorophyll biosynthesis (Fig. 3). These studies highlighted that Ni toxicity disrupts nutrient uptake and impairs photosynthesis, leading to nutrient deficiencies, stunted growth, chlorosis, and reduced productivity. This highlights the negative impact of excessive Ni on plant health and underscores the need for careful management of its concentrations.

Figure 3: Decline in crop growth due to Heavy metals Toxicity

6 Nickel Interference with Water Movement and Uptake in Plants

The effects of nickel toxicity on plant water relations are not yet fully understood, with some conflicting results in the literature. Heavy metals, including Ni, come into direct contact with the roots, which play crucial roles in nutrient storage, water and nutrient absorption, and providing support for the plant body. Compared to shoots and leaves, roots tend to accumulate higher concentrations of heavy metals [104]. Ni and other heavy metals can slow down the flow of water from roots to shoots leading to dehydration in the shoots [105]. Heavy metal stress affects stomatal function, including the opening and closing of stomata, water intake, and the movement of water through both the symplast and apoplast [106], which disrupts overall plant water relations. According to Bishnoi, Sheoran [107], nickel stress lowers stomatal conductance, transpiration rates, leaf water potential, and moisture contents. Pandey and Pathak [108] also found that excessive Ni disrupts plant water relations in plants, leading to stress. Additionally, heavy metals hinder seed germination, resulting in a poor crop stand.

Similar to this, Bhagawatilal et al. [109] applied the gram plant to various degrees of Nickel stress. They claimed that turgor potential and water potential were considerably decreased by growth inhibitory Ni concentrations of 10, 100, and 1000 M. Furthermore, heavy metal stress reduces water transfer between symplast and apoplast, reducing water flow through the vascular system and the delivery of water towards shoots. The loss in tracheids and vessels due to the stress exerted by heavy metal also affects the plants stems and roots hydraulic conductivity which in turn affects water transport [110]. Nickel stress also hampers transpiration because of smaller leaves, thinner laminae, and smaller intracellular spaces [111]. Pigeon pea and cabbage suffer from decreased transpiration rates and water content due to nickel toxicity [92]. Rauser and Dumbroff [112] discovered insignificant findings for relative water contents (RWC) under Ni stress throughout the growth period of the crop and revealed a substantial decrease in relative water contents at the later stage of crop growth. Due to the buildup of suitable solutes, Ni poisoning also affects alterations in plant-water relationships. As an illustration, several osmolites, such as proline [94], different amino acids, and different sugars [96] accumulate when Ni stress is present. These osmolites promote plant viability during Ni stress by significantly reducing the solute and water potential. As a result of influencing root development, transpirational rate, opening and closing of stomata, and hydraulic conductivity of root, the nickel stress disrupts the plant’s water relations.

7 Impact of Nickel on the Membrane Permeability and Oxidative Metabolism

Toxic metals initially interact with the plant cell’s plasma membrane, which is a functioning component. These harmful metals impair the structural conformation, permeability, and functional properties of different enzymes, including ATPase [113]. Under Ni stress, the permeability of the membrane can be reduced as a result of osmolyte loss and decreased turgor pressure of cells [114]. Furthermore, one of the main effects of Ni stress on plants is the leaking of important ions across the cell membrane [68]. Reactive oxygen species (ROS), for example, superoxide, hydroxyl radicals, hydrogen peroxide, and alkoxy radicals, are formed in plants when the concentration of nickel in the growth media is too high [1]. Nickel membrane deterioration, lipid peroxidation oxidative damage to membranes, proteins and lipids [115]. In pea plants exposed to different Ni concentrations (0.5 and 1.5 mM), malondialdehyde, a byproduct of lipid peroxidation, significantly increased under both levels [116], with similar results observed in wheat and maize [117]. Furthermore, Ni enhanced NADPH oxidase activity, leading to increased ROS generation of wheat roots [118].

In a study on wheat crops done by Gajewska and Skodowska [119], it was shown that 3-days experience with nickel raised the levels of ROS such as O2 as well as hydrogen per oxide (H2O2) in plant foliage up to 250%. However, to protect themselves from oxidative stress, plants have antioxidant enzyme system (i.e., superoxide dismutases, peroxidases, catalases, glutathione reductases etc.) and non-enzymatic antioxidants (i.e., ascorbic acids, glutathiones, phenols) [120]. Plants subjected to low concentrations of nickel (i.e., 0.05 mM) have increased the activity of antioxidant enzymes, which help in activating the antioxidant’s defence system and eliminates ROS. However, the excess Ni significantly lowers the antioxidant enzyme activity and the capacity of plants to scavenge ROS, leading to building ROS. When the seedlings of the Pigeon pea were treated with 0.5 mM Ni, they substantially enhanced the Peroxidase, Superoxidase, and GR activity, but dramatically reduced the CAT activities as a result of Nickel [120]. In a different experiment, Pandey & Sharma [121] noted that cabbage flowers treated with nickel at a concentration of 0.5 mM for 7 days had decreased the activities of CAT and POD. Papadopoulos, Prochaska [122] discovered comparable outcomes after treatment of Hydrocharis dubia plants with Nickel (0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4 mM) for four days. According to Freeman, Persans [123], during nickel stress, the events of many antioxidants (i.e, SOD, CAT, APX, and glutathione S-transferases) considerably enhanced as they detoxified the ROS. Moreover, Wang et al. [124] discovered a significant decrease in CAT, GPX, and SOD activity in Nickel-stressed Luffa cylindrica. Furthermore, Pigeon pea was also subjected to oxidative stress due to Nickel, which exhausted the low-molecular weight protein [116]. Depending on the kind and length of stress, different plant species exhibit different antioxidant enzyme activity. By treating the wheat with 100 mM of Nickel for 3 to 9 days, Gajewska and Skodowska [81] observed increase in CAT and SOD activity and a decrease in GSH-Px, and GOPX activities. Gajewska and Sklodowska [125] found that SOD as well as APX levels in the roots and leaves decreased when pea plants were exposed to Ni for 1 to 9 days. In addition, numerous additional researchers discovered that glutathione transferase activity in contrast to the activity of CAT, significantly increased in the roots and leaves. These systems are unable to forage the ROS that increases lipid and electrolyte leakages under high Ni stress [124].

Microbial enzyme synthesis and metal immobilization strategies can be improved for particular environmental factors and soil type to increase Ni bioremediation and mitigate its toxic effects. Key factors including pH, temperature, microbial diversity and organic matter content significantly influenced bioremediation efficiency. The adaptability can be enhanced via genetic engineering or by choosing native microbial strains from Ni-contaminated soils to boost enzyme activity and immobilization of metals. Furthermore, improving the availability of nutrients and incorporating soil amendments such as biochar or other organic applications can further promote microbial-mediated NiNP detoxification. By tailoring these approaches to specific environmental conditions, the efficacy and sustainability of bioremediation strategies can be significantly improved. Thus, understanding the mechanisms of Ni-induced oxidative stress and membrane damage, along with optimizing microbial-assisted remediation strategies, is crucial for developing sustainable approaches to mitigate heavy metal toxicity in plants and improve soil health.

8 Impact of Nickel Stress on the Synthesis of Proteins and Amino Acids

Because of a decrease in protein synthesis as well as hydrolysis, heavy metal-induced stress dramatically lowers the amount of various soluble proteins in a variety of plants [126]. According to Kevrešan et al. [127], nickel and Cadmium stress dramatically decreased the protein levels of the sugarbeet plant. On the other hand, Ewais [128] found that Cyperus deformis plants exposed to Nickel and Cadmium stress had significantly higher protein concentrations in their roots and shoots. Through a variety of methods, heavy metal stress lowers the protein content or modifies its structure. According to Gajewska et al. [119], Ni stress significantly raises the formation of ROS, which in turn causes protein degradation. Furthermore, Ni attaches to functional protein groups (i.e., SH-groups), changing the protein structure. The activities of enzymes with these changes are significantly reduced. All of this information points to the harmful effects of nickel on the structure and functional behaviour of proteins. In addition, metal stress causes various amino acids to build up in plant cells, significantly reducing the amount of protein present [129]. By building up various amino acids, metals are detoxified, resultantly the plants are shielded from their hazardous impacts [130]. Stackhousia tryonii was used in an experiment by Bhatia et al. [131] to examine the amino acids composition in xylem. They discovered that Ni-induced stress results in decreases of 22% and 48% in amino acid and glycine accumulation, respectively. However, with Ni stress, asparagine and glutamine accumulation increased. The greatest complex between histidine and glycine was also discovered by Smith and Martell [132].

According to Freeman et al. [123], glutathione and cysteine buildup are significantly correlated with Ni toxicity. Additionally, they noted an increase in amino acid synthesis, and enhanced tolerance of plants to Ni-induced stress via an increase in GSH-dependent antioxidant activity. Histidine and cysteine are synthesized in greater quantities in canola plants as a result of Ni toxicity. Increased translocation of Ni from root to shoot increased amino acids and enhanced the detoxification of nickel [133]. Thus, the Ni stress, particularly in hyper-accumulating plants, is the accumulation of amino acids [130]. Therefore, increased protein breakdown caused by greater Ni concentrations may result in increased amino acid buildup in plants. Collectively, Ni stress negatively impacts protein synthesis, reducing soluble protein levels and altering protein structure. While some plants show increased protein content, nickel toxicity typically leads to protein degradation. The accumulation of amino acids helps detoxify the metal and enhances plant tolerance to nickel stress.

9 Nickel Impact on Yield and Dry Matter Accumulation

Improving dry matter production is the primary need for obtaining a high yield of agricultural plants. Low concentrations of Ni are thought to be necessary, but large concentrations of Ni significantly lower crop output. The Ni exerted stress on root and shoot with a significant decline in their development [133]. Due to the buildup of high Ni concentrations, plant dry matter production was drastically decreased [134]. In a different investigation, Duman and Ozturk [135] found that the generation of dry matter increased significantly at low Ni concentrations (0–5 mg Ni/L), but that dry matter production significantly decreased at higher Ni concentrations (i.e., 6 to 25 mg Ni/L), where it became hazardous. In Brassica juncea, Ni-induced stress (100 mM) dramatically reduced the dry matter content, according to Masidur et al. [83]. At lower doses (10 and 50 mM), Ni considerably increased the biomass of the roots and shoots [96]. Ni-induced toxicity reduces crop productivity even at lower levels (i.e., 10 mg L−1). The study conducted by Singh and Nayyar [136] showed a decrease in cowpea biomass upon applying 50 mg kg−1 of Ni to the soil. Even so, four distinct gram cultivars of nickel-stressed soil showed a clear decrease in biomass production, nodule formation, root and shoot length, as well as an economic yield [137]. Furthermore, Keeling et al. [138] showed that nickel concentrations ranging from 0 to 1000 mg L−1 caused the longest spikes. Spike length, 1000 grain weight, and other yield variables, however, sharply decreased as the concentration of nickel rose over this level. Overall, while, low concentrations of nickel may have some beneficial effects on plant growth, excessive nickel concentrations severely impact dry matter accumulation and crop yield. The toxic effects of Ni are evident through reduced biomass, impaired root and shoot development, and diminished yield variables, emphasizing the importance of managing nickel levels in agricultural soils to maintain optimal plant productivity.

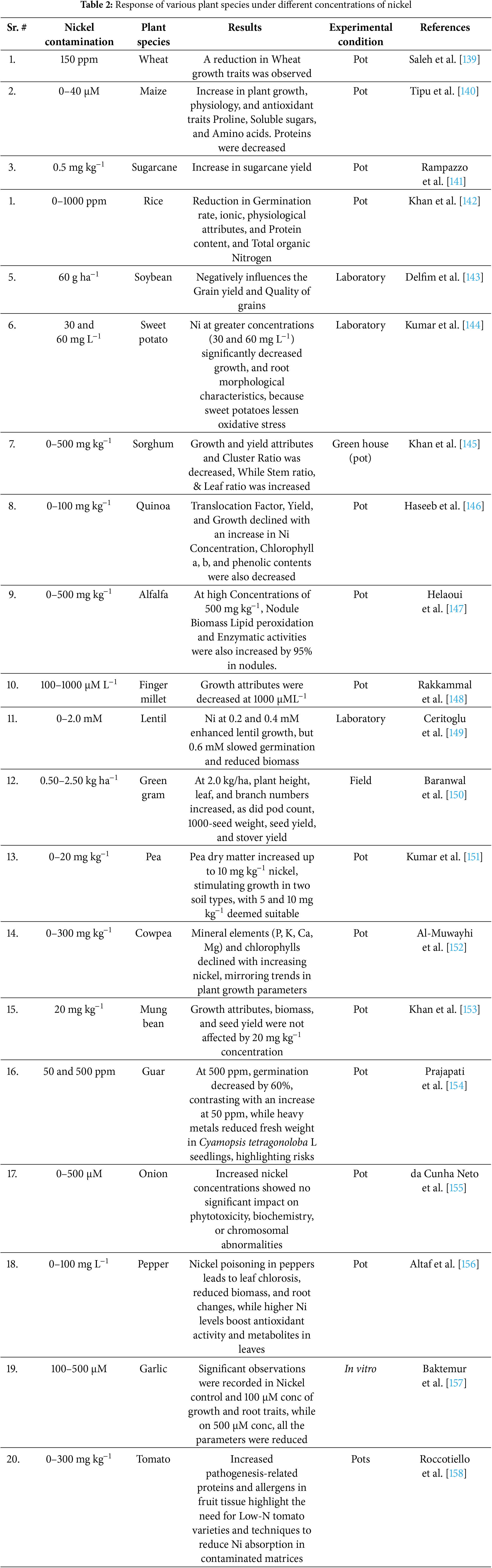

Changes in nutrient intake, plant metabolisms, water relations, photosynthesis, transpiration, and oxidative damage are the causes of the decrease in dry matter production linked to nickel [159] (Table 2). Wheat exposed to 150 ppm Ni exhibited reduced growth traits, indicating its sensitivity to Ni stress [139]. Similarly, rice grown under 0–1000 ppm Ni experienced a decline in germination rate, physiological attributes, protein content, and total organic nitrogen, demonstrating Ni’s inhibitory effects on early growth and metabolism [142]. In plants, Ni contamination at 60 g ha−1 negatively impacted grain yield and quality [143]. Likewise, sweet potatoes exposed to 30 and 60 mg L−1 Ni exhibited reduced growth and root morphological characteristics due to oxidative stress [144]. Certain plants showed a more complex response to Ni exposure. In maize, Ni concentrations between 0 and 40 μM led to an increase in plant growth, physiology, and antioxidant traits, while reducing protein content [140]. Sugarcane exhibited increased yield at 0.5 mg kg−1 Ni, suggesting a potential growth-promoting effect at lower concentrations [141]. Green gram responded positively to Ni at 2.0 kg ha−1, with increased plant height, leaf number, branch number, pod count, seed weight, and overall yield [150]. Similarly, pea growth improved at 5–10 mg kg−1 Ni, demonstrating a threshold below which Ni may act as a micronutrient rather than a toxicant [144].

However, excessive Ni exposure generally resulted in adverse effects. Sorghum grown in 0–500 mg kg−1 Ni experienced a reduction in growth and yield attributes, while the stem and leaf ratios increased, suggesting altered biomass allocation under stress [145]. Quinoa and cowpea exhibited reduced translocation factors, yield, and chlorophyll content under increasing Ni levels, confirming its detrimental impact on plant metabolism [146,152]. Ni toxicity also influenced nodulation and enzymatic activity in legumes. In alfalfa, exposure to 500 mg kg−1 Ni led to a 95% increase in enzymatic activities and lipid peroxidation in nodules, indicating oxidative stress [147]. Lentil showed increased growth at 0.2–0.4 mM Ni, but higher concentrations (0.6 mM) reduced biomass and slowed germination, reflecting a concentration-dependent response [149]. In vegetables, Ni exposure resulted in mixed effects. While onion plants showed no significant changes in phytotoxicity, biochemistry, or chromosomal abnormalities under 0–500 μM Ni [155], pepper experienced leaf chlorosis, reduced biomass, and root alterations, with higher Ni concentrations stimulating antioxidant activity and metabolite production [156]. Garlic exhibited growth improvements at 100 μM Ni, but at 500 μM, all growth parameters declined [157,158]. Similarly, tomato plants exposed to 0–300 mg kg−1 Ni demonstrated increased pathogenesis-related proteins and allergens in fruit tissues, highlighting potential food safety concerns [158]. These findings suggest that while Ni can act as a beneficial micronutrient at low concentrations in some species, excessive exposure leads to toxicity, disrupting physiological and biochemical processes (Table 2). The effects of Ni contamination vary widely depending on plant species, concentration levels, and growth conditions, emphasizing the need for careful management of Ni levels in agricultural systems.

10 Microbial Mediated Bioremediation of Heavy Metals

Microbial bioremediation is the process of breaking down, reducing, purifying, or converting environmental pollutants by means of microorganisms and their special enzyme systems. “Coalitions” of organisms that are naturally existing in polluted areas and have the potential for helpful metabolism are key components of microbial bioremediation strategies [160]. The primary technique for microbial remediation of polluted medium is immobilization and reduction of the bioavailability of contaminants. Inorganic contaminants like heavy metals cannot be broken down by microbes; nevertheless, due to their altered chemical and physical properties, they can transform into new forms [161]. For instance, in environmental bioremediation applications of inorganic pollutants, bacteria can be nourished on solid agricultural waste to supply the macro- and micronutrients required for biofilm development. According to Mahdi and Aziz [88], this further boosts the metabolic activities of the microorganisms for the solubilization and biodegradation of hydrocarbon pollutants.

In addition, there are other ways in which bacteria and metal ions might interact that are comparable to this. Depending on how metabolism is involved, these activities may be divided into two groups: active and passive absorption of metal ions [162]. The two most significant of these mechanisms are the ways in which the biomass, or microorganisms, bind to and concentrate environmental pollutants: bioaccumulation and biosorption. The processes of biosorption and bioaccumulation are different. Bioaccumulation is a delayed, two-stage metabolic process that is partially reversible in living biomass. The first method is similar to biosorption by microbial biomass and microbe byproducts and includes fast sorption, according to Gupta and Diwan [162] and Chojnacka [163]. The second, slower step includes the metabolically active transport mechanism physiologically delivering sorbate into the interior of cells. Bioaccumulation species should have an internal binding mechanism, as demonstrated by special proteins rich in thiol groups, including metallothioneins (MTs) and phytochelatins (PCs). These proteins are generated in response to toxic copper ions present in their atmosphere, which allows the compound containing those pollutants to be removed from normal metabolic processes [163]. By contrast, biosorption does not rely on metabolism and operates in a passive manner. Through a number of physiochemical mechanisms, biomass—both alive and dead—can carry out the remediation role [162]. The kind of pollutants and microorganisms involved determine how efficient microbial remediation is. The kind of pollutants and microorganisms involved determine how efficient microbial remediation is. It is interesting to note that the microbial activity in the root/rhizosphere soils may increase the effectiveness of phytoremediation techniques in polluted regions. Microbe-assisted phytoremediation enhances the remediation of inorganic contaminants by pairing plants (usually contaminant-tolerant species) with endophytic or rhizospheric bacteria [164,165].

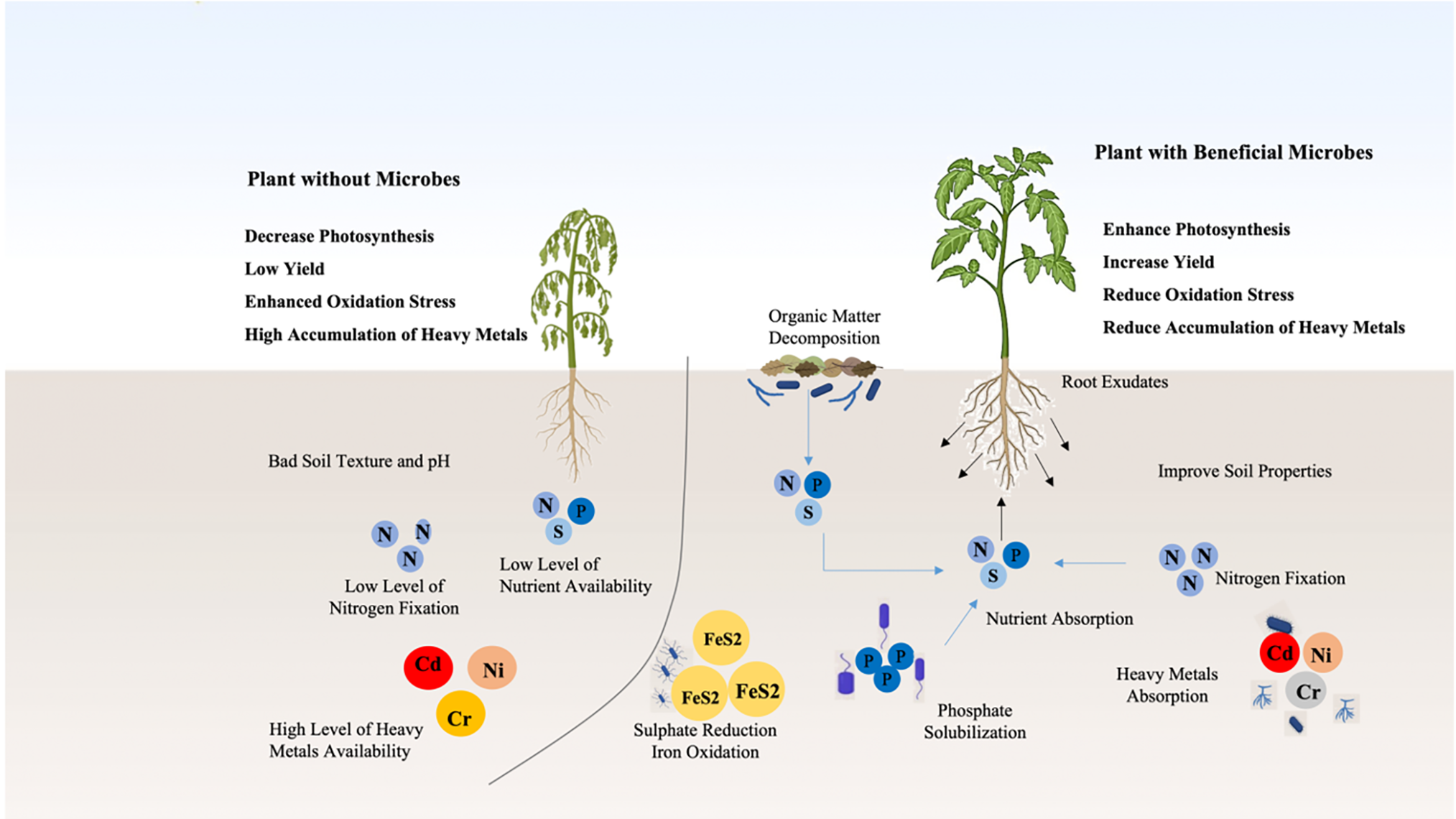

Utilising two complementary approaches, effective remediation can be accomplished: (i) direct stimulation of phytoremediation, wherein microorganisms associated with plants either increase the translocation of pollutants (also known as phytoextraction) or decrease their mobility and availability in the rhizosphere (also known as phytostabilization). and (ii) indirect augmentation of phytoremediation, wherein microorganisms increase biomass production to either stop or remove the contaminants or help plants tolerate them [164]. According to some theories as shown in Fig. 4, rhizospheric microorganisms can: (i) work with roots to increase metal absorption capacity; (ii) release compounds to increase pollutant bioavailability; (iii) encourage roots to take up extra metals and nutrients; and (iv) modify the synthetic properties of pollutants to specifically change their dissolvability [166,167]. While microbial bioremediation shows significant potential, scaling up from controlled environments like laboratories or greenhouses to field applications poses several challenges. Environmental factors such as soil type, moisture, temperature, and microbial competition can strongly influence the survival and efficacy of introduced microbial strains. Successful field applications require selecting site-specific, stress-tolerant microbial strains capable of thriving in variable environmental conditions. Additionally, optimizing application methods—such as seed coating, soil amendments, or biochar inoculation—can enhance microbial establishment and activity in field conditions. Integrating supportive practices like organic amendments may further improve microbial persistence and efficacy. Future research should focus on strategies to improve microbial stability and function under field conditions, ensuring their long-term success in heavy metal-contaminated soils. Promising microorganisms from the lab or greenhouse must be evaluated in field settings where environmental variability may produce different outcomes [167]. Microbe-assisted phytoremediation will not work if inoculants are not given correctly [164]. Numerous techniques, such as treating seeds, foliar spraying, and direct soil inoculation, can be used to introduce them to pollute agricultural soils [168]. According to de Oliveira et al., [169] forthcoming studies should focus on the additional instruments causing the decline in seed germination and seedling development caused by Ni toxicity. These studies highlight the potential of microbial-mediated bioremediation, especially when combined with phytoremediation, to address heavy metal contamination. Microorganisms can enhance plants’ ability to absorb, stabilize, or degrade pollutants in the rhizosphere. However, the success of these methods depends on proper microbial inoculation and environmental conditions. Future research should focus on optimizing these techniques and addressing challenges like the impact of heavy metals on seed germination and seedling growth.

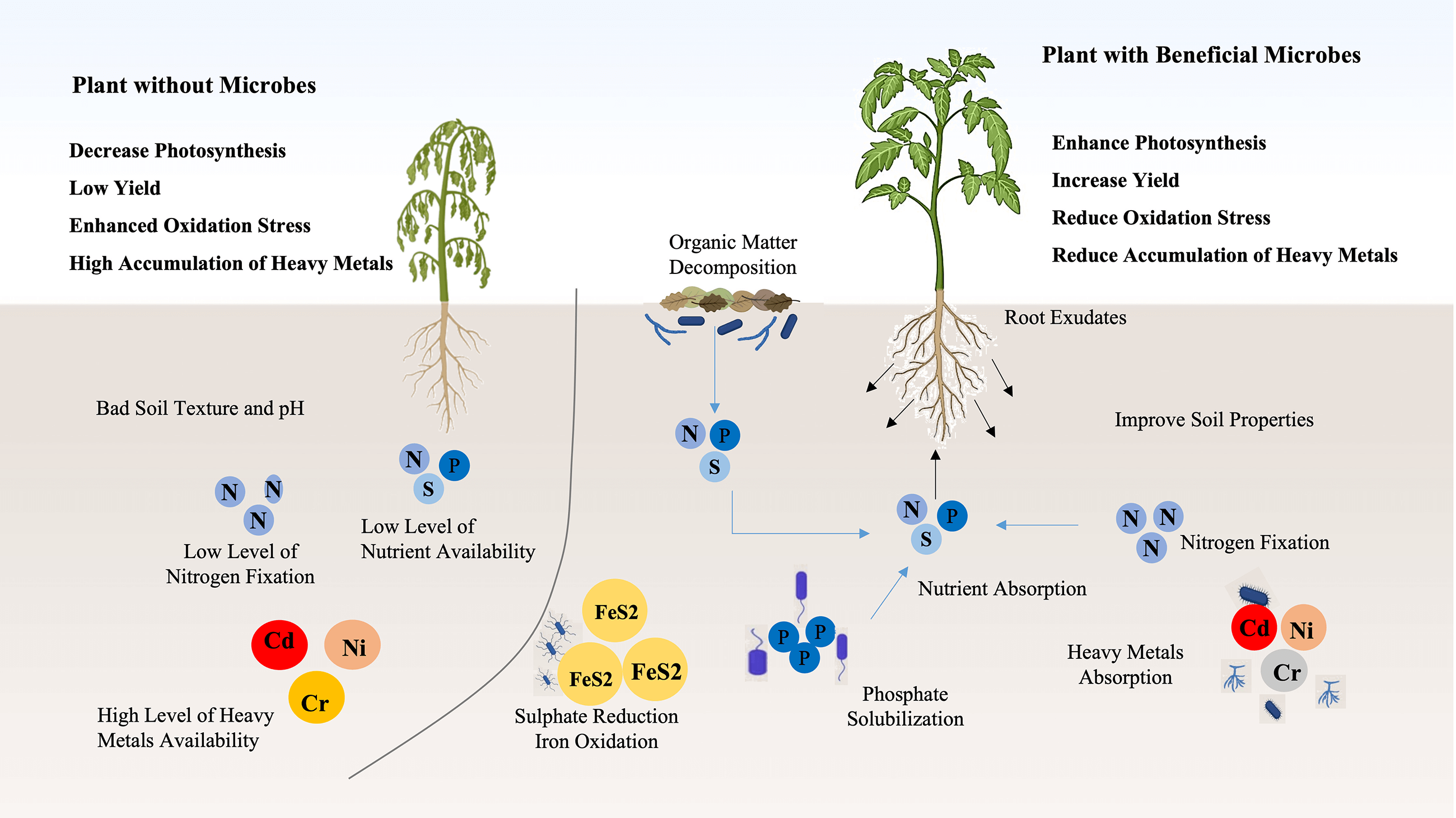

Figure 4: Mitigation effect of soil microorganisms under heavy metal toxicity

11 Overview of the Mechanisms through Which Microorganisms Detoxify Nickel

Nickel efflux is one of the key defence mechanisms that cells employ to counteract high concentrations of nickel. Interestingly, cells exhibit chemotactic responses to environmental Ni levels. Englert et al. [170] demonstrated that independent of NikA, the methyl-accepting chemotaxis protein Tar mediates the chemotactic-repellent action of nickel. Nickel-resistant strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae have long been recognized or their ability to sequester nickel in vacuolar compartments, where it coexists with elevated levels of the amino acid histidine [171]. Research has shown that strains with impaired vacuolar acidification due to defective vacuolar proton ATPase exhibit elevated Ni toxicity.

Genetic studies further reveal that histidine autotrophs are more sensitive to nickel than to other metals. Moreover, Ruotolo et al. [172] reported that yeast cells with knockout mutations in iron-importer genes display increased susceptibility to nickel. Arita et al. [173] conducted genome-wide analyses in S. cerevisiae and identified 149 genes whose deletion results in heightened in nickel sensitivity, indicating their potential role in nickel resistance. These genes are associated with diphthamide biosynthesis, siderophore-iron transporters, cation transporters, and proton-transporting ATPase.

Sulfate-reducing bacteria can produce substantial amounts of sulfide, which can mitigate metal toxicity. For example, a nickel-resistant strain of Desulfotomaculum cultivated in high nickel environments produces a dark-brown, soluble nickel-sulfide compound that effectively reduces the concentration of free nickel ions [174]. Likewise, Pseudomonas putida S4 accumulates nickel in the periplasm as a resistance mechanism, potentially facilitated by an 18 kDa protein [101]. Certain strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa also accumulate nickel within their cells, with energy-dispersive X-ray analysis confirming the presence of metallic nickel [175]. Moreover, Thiocapsa roseopersicina, when grown on hydrogen gas, exhibits the reduction of Ni (II) to elemental nickel, which is associated with enhanced nickel resistance. The efficiency of biosorption processes in removing heavy metals, including nickel, is influenced by several factors. These include the nature of the biosorbent (living or non-living), the physicochemical properties of the metal, the type of biological ligands used for metal sequestration, and various parameters, such as temperature, pH, contact time, and sorbent and sorbate concentrations. Additionally, the composition of the metal solution, including the presence of competing co-ions, plays a crucial role in biosorption efficiency. These factors must be considered when developing effective biosorption strategies for removing heavy metals from contaminated environments.

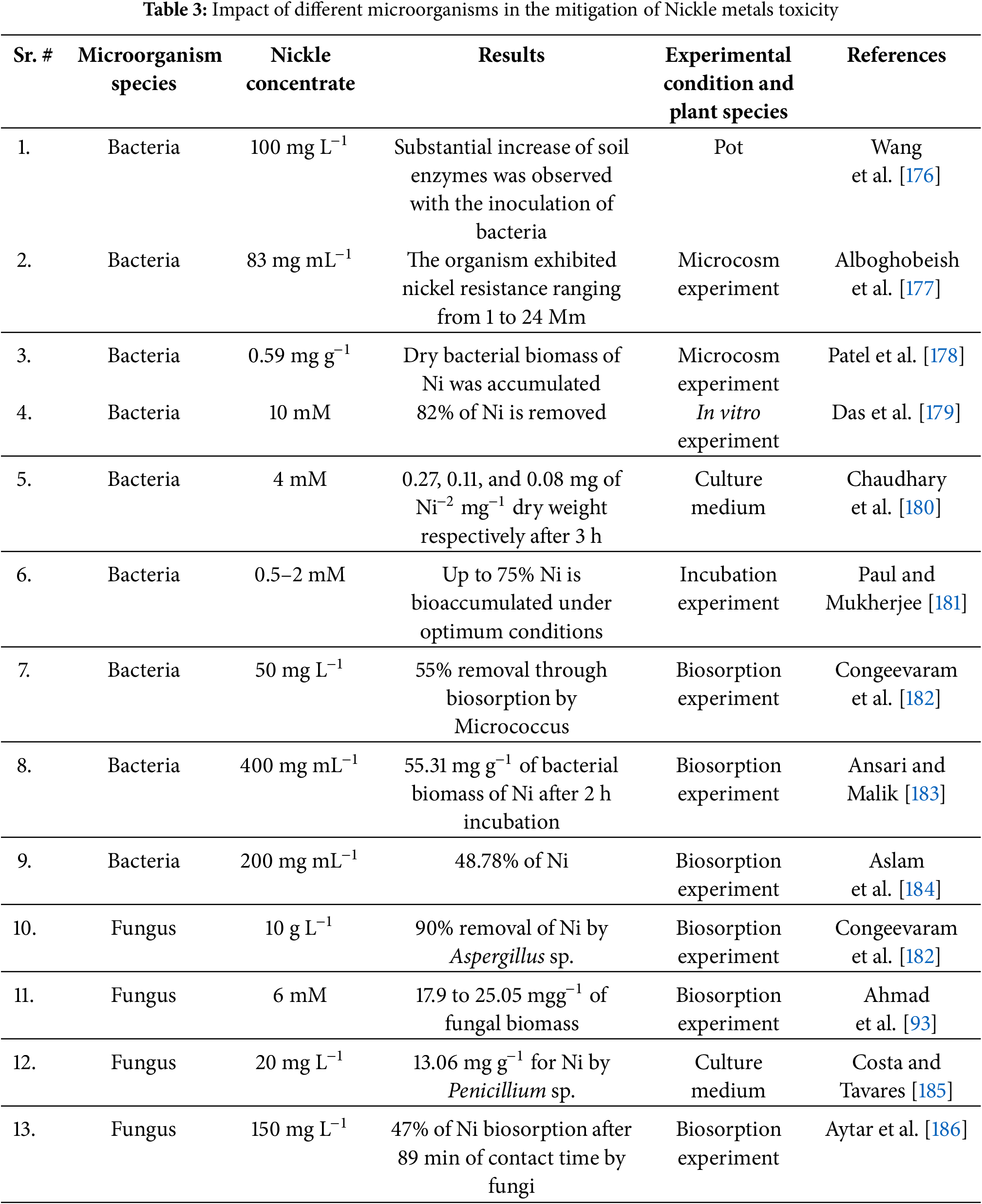

Table 3 summarizes the contributions of various bacterial and fungal species in mitigating Ni toxicity under different experimental conditions. Several bacterial species have demonstrated significant potential in Ni detoxification. Wang et al. [176] observed a substantial increase in soil enzyme activities when bacteria were inoculated into a pot experiment with Ni at 100 mg L−1, suggesting microbial enhancement of soil biochemical functions. Similarily, Alboghobeish et al. [177] reported bacterial Ni resistance ranging from 1 to 24 mM in a microcosm experiment, indicating their adaptability to high Ni concentrations. The bioaccumulation potential of bacterial biomass was further demonstrated by Patel et al. [178], who recorded Ni accumulation of 0.59 mg g−1 in a microcosm experiment, highlighting the capacity of bacteria to sequester Ni within their biomass. In vitro and culture-based studies further confirm bacterial efficiency in Ni removal. Das et al. [179] reported that 82% of Ni at 10 mM concentration was removed in an in vitro experiment, showcasing the strong Ni-binding capacity of bacterial cells. Chaudhary et al. [180] demonstrated bacterial Ni uptake of 0.27, 0.11, and 0.08 mg per mg dry weight within 3 h in a culture medium, suggesting a rapid metal assimilation process. Furthermore, Paul and Mukherjee [181] observed that bacteria could bioaccumulate up to 75% of Ni under optimized conditions in an incubation experiment, reinforcing the potential of bacterial systems for bioremediation. Biosorption studies have also provided compelling evidence of bacterial involvement in Ni detoxification. Congeevaram et al. [182] demonstrated that Micrococcus removed 55% of Ni at 50 mg L−1 in a biosorption experiment, while Ansari and Malik [183] reported Ni biosorption of 55.31 mg g−1 of bacterial biomass within 2 h at 400 mg mL−1, confirming the efficiency of bacterial-mediated metal uptake. Similarly, Aslam et al. [184] found that bacterial species removed 48.78% of Ni at 200 mg mL−1, further validating their role in heavy metal sequestration. Fungal species also exhibit remarkable Ni biosorption capabilities. Congeevaram et al. [182] found that Aspergillus sp. removed 90% of Ni at 10 g L−1 in a biosorption experiment, highlighting the efficiency of fungal cell walls in metal binding. Ahmad et al. [93] reported Ni biosorption ranging from 17.9 to 25.05 mg g−1 of fungal biomass at 6 mM, while Costa et al. [185] demonstrated Ni removal of 13.06 mg g−1 using Penicillium sp. in a culture medium at 20 mg L−1, suggesting a species-specific variation in metal uptake efficiency. Aytar et al. [186] further showed that fungal species could achieve 47% Ni biosorption after 89 min of contact time at 150 mg L−1, emphasizing the rapid metal-binding ability of fungi. Overall, bacterial and fungal species effectively detoxify Ni through biosorption and bioaccumulation, highlighting their potential for bioremediation. Future research should optimize microbial inoculation and explore underlying mechanisms to enhance their practical application.

12 Challenges and Limitations Associated with Bioremediation

The primary limitation of bioremediation is its restricted applicability to certain substances, particularly non-biodegradable nature. Even when a material is biodegradable, its decomposition amay generate more harmful byproducts. Additionally, site-specific factors can hinder the effectiveness of microbial strain, as a strain functional in one location may not perform well in another. Priya et al. [187] reported that the complexity of bioremediation depends on factors such the presence of the right amount of nutrients, pollutants type, and metabolic process. Moreover, the use of heavy machinery and pumps can cause noise and disturbances, raising environmental and ethical concerns. In some cases, the introduction of specific bacterial strains may disrupt local microbial communities, leading to ecological imbalances. Improper disposal of heavy metals contaminated waste into soil and aquatic ecosystems poses significant risks, including toxicity to aquatic life, biomagnification, and long-term health hazards for humans and animals. Thus, remediation through physical, chemical, or biological methods is essential.

However, while chemical and physical approaches have been widely used, they have notable drawbacks. Chemical remediation requires specialized equipment and expertise, whereas physical remediation is often costly. Bioremediation (bioremediation), though a promising alternative, has its own challenges. It is typically slower than other remediation methods, may not effectively degrade all organic and inorganic pollutants, and might fail to completely remove toxins from contaminated sites [188]. In-situ bioremediation requires highly permeable soils, making it difficult to quantify pollutant concentrations [189]. Additionally, microbial metabolism can sometimes transform pollutants into more toxic compounds. For instance, it can convert polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons into less biodegradable compounds and trichloroethylene into vinyl chloride. When these substances come into contact with groundwater, they can then mobilize [13]. It can be difficult to control unstable organic mixtures in ex-situ bioremediation since some components (including heavy metals, radionuclides, and chlorinated compounds) are not biodegradable. Despite these limitations, bioremediation remains a viable and environmentally friendly approach, requiring further research to optimize microbial efficiency and address site-specific challenges.

13 Factors That May Hinder the Efficiency of Bioremediation for Nickel Pollution

The properties of the microorganisms, such as their kind, population density, competition amongst them, capacity to produce biosurfactants, and ability to metabolize pollutants are the factors for microbial bioremediation [190]. Relevant pollutant features include chemical structure, toxicity, concentration in the site, and bioavailability [191]. The kind of soil at the site, temperature, water availability, nutrients, salinity, pH, and oxygen are among the environmental factors that have a big influence on bioremediation [190]. An additional layer of complexity to the procedure are the ethical concerns surrounding the use of particular bacterial strains and their potential effects on the local microflora.

14 Conclusions and Future Perspectives

The mechanisms underlying nickel (Ni) tolerance in plants remain largely unclear, necessitating future research to elucidate the physiological, biochemical, and molecular strategies that plants employ to cope with Ni stress. Nickel contamination poses a significant environmental threat, affecting plant health, human well-being, and animal ecosystems. Addressing these challenges requires comprehensive studies to develop effective mitigation strategies. Prior research has demonstrated that Ni toxicity induces reactive oxygen species (ROS) formation, disrupts enzymatic functions, and alters antioxidant defense systems. Additionally, Ni interferes with essential mineral uptake and translocation, highlighting the need for further molecular investigations. This review underscores the critical importance of tackling environmental contamination, particularly heavy metal pollution, and highlights the potential of microbe-mediated bioremediation as a sustainable remediation strategy. Beneficial microorganisms play a crucial role in regulating biochemical processes, facilitating heavy metal detoxification, and improving soil health. Despite advancements in microbial applications for soil remediation, there remains substantial scope for refining these approaches to enhance their efficacy and field applicability.

Future research should focus on optimizing microbial inoculation strategies, improving microbial persistence under field conditions, and integrating bioremediation with phytoremediation for more effective metal detoxification. Furthermore, understanding the molecular and genetic regulation of phytohormone synthesis in plants under metal stress is essential for improving stress resilience. Investigating key genes involved in auxin (IAA), salicylic acid (SA), abscisic acid (ABA), and cytokinin (CK) biosynthesis, along with their regulatory networks, could provide insights into plant-microbe interactions during metal detoxification. Transcriptomic and metabolomic approaches can help identify specific signaling pathways activated by beneficial microbes, such as Bacillus subtilis, under Ni stress. These findings could pave the way for targeted genetic or microbial interventions to enhance plant stress tolerance. To maximize the potential of bioremediation, sustained scientific research is needed to develop field-ready solutions that ensure the long-term effectiveness of microbial-based remediation techniques. A collaborative effort involving scientists, policymakers, and industry stakeholders is essential to drive the widespread adoption of innovative bioremediation strategies. Through continuous research and technological advancements, we can mitigate the detrimental effects of heavy metal pollution and safeguard environmental sustainability for future generations.

Acknowledgement: The authors are grateful to the Sanya Institute of Nanjing Agriculture University/Jiangsu Collaborative Innovation Center for Modern Crop Production/Key Laboratory of Crop Physiology Ecology and Production Management, Nanjing Agricultural University, Nanjing, 211800, China.

Funding Statement: The research was supported by the project of Sanya Yazhou Bay Science and Technology City, Grant No. SKJC-2023-02-004; Education Department of Hainan Province, Grant No. Hnky2024ZD-27; Key R&D Project of Hainan Province (Science and Technology Commissioner): 405314040001.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Hua Zhang, Ganghua Li; Writing—original draft, Hua Zhang; Writing—review & editing, Ganghua Li; Software, Formal analysis: Hua Zhang, Ganghua Li. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Azeem I, Wang Q, Adeel M, Shakoor N, Zain M, Khan AA, et al. Assessing the combined impacts of microplastics and nickel oxide nanomaterials on soybean growth and nitrogen fixation potential. J Hazard Mater. 2024;480(6223):136062. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2024.136062. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Han J, Zhang R, Tang J, Chen J, Zheng C, Zhao D, et al. Occurrence and exposure assessment of nickel in Zhejiang Province. China Toxics. 2024;12(3):169. doi:10.3390/toxics12030169. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Arora D, Arora A, Panghal V, Singh A, Bala R, Kumari S, et al. Unleashing the feasibility of nanotechnology in phytoremediation of heavy metal-contaminated soil: a critical review towards sustainable approach. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2024;235(1):57. doi:10.1007/s11270-023-06874-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Dasgupta D, Barman S, Sarkar J, Mridha D, Labrousse P, Roychowdhury T, et al. Mycoremediation of different wastewater toxicants and its prospects in developing value-added products: a review. J Water Process Eng. 2024;58(2):104747. doi:10.1016/j.jwpe.2023.104747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Angon PB, Islam MS, Kc S, Das A, Anjum N, Poudel A, et al. Sources, effects and present perspectives of heavy metals contamination: soil, plants and human food chain. Heliyon. 2024;10(7):e28357. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e28357. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Hou D, O’Connor D, Igalavithana AD, Alessi DS, Luo J, Tsang DCW, et al. Metal contamination and bioremediation of agricultural soils for food safety and sustainability. Nat Rev Earth Environ. 2020;1(7):366–81. doi:10.1038/s43017-020-0061-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Hu X, Yu C, Shi J, He B, Wang X, Ma Z. Biomineralization mechanism and remediation of Cu, Pb and Zn by indigenous ureolytic bacteria B. intermedia TSBOI. J Clean Prod. 2024;436:140508. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.140508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Koumaki E, Noutsopoulos C, Mamais D, Fragkiskatos G, Andreadakis A. Fate of emerging contaminants in high-rate activated sludge systems. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(2):400. doi:10.3390/ijerph18020400. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Vieira DCS, Yunta F, Baragaño D, Evrard O, Reiff T, Silva V, et al. Soil pollution in the European union—an outlook. Environ Sci Policy. 2024;161(1):103876. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2024.103876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Candeias C, Melo R, Ávila PF, Ferreira da Silva E, Salgueiro AR, Teixeira JP. Heavy metal pollution in mine-soil–plant system in S. Francisco de Assis-Panasqueira mine (Portugal). Appl Geochem. 2014;44(5):12–26. doi:10.1016/j.apgeochem.2013.07.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Su Y, Zhu M, Zhang H, Chen H, Wang J, Zhao C, et al. Application of bacterial agent YH for remediation of Pyrene-heavy metal co-pollution system: efficiency, mechanism, and microbial response. J Environ Manage. 2024;351:119841. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.119841. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Singh K, Pandey SN. Effect of nickel-stresses on uptake, pigments and antioxidative responses of water lettuce, Pistia stratiotes L. J Environ Biol. 2011;32(3):391–4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

13. Jain S, Arnepalli DN. Biominerlisation as a remediation technique: a critical review. In: Geotechnical characterisation and geoenvironmental engineering. Singapore: Springer; 2018. p. 155–62. doi:10.1007/978-981-13-0899-4_19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Iwanowicz DD, Baldwin AK, Barber LB, Blazer VS, Corsi SR, Duris JW, et al. Integrated science for the study of microplastics in the environment—a strategic science vision for the US Geological Survey. Reston, VA, USA; 2024. [Google Scholar]

15. Zhang W. Global pesticide use: profile, trend, cost/benefit and more. Proc Int Acad Ecol Environ Sci. 2018;8(1):1–27. [Google Scholar]

16. Bradley PM, Journey CA, Romanok KM, Barber LB, Buxton HT, Foreman WT, et al. Expanded target-chemical analysis reveals extensive mixed-organic-contaminant exposure in U.S. streams. Environ Sci Technol. 2017;51(9):4792–802. doi:10.1021/acs.est.7b00012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Pan H, Lei H, He X, Xi B, Xu Q. Spatial distribution of organochlorine and organophosphorus pesticides in soil-groundwater systems and their associated risks in the middle reaches of the Yangtze River Basin. Environ Geochem Health. 2019;41(4):1833–45. doi:10.1007/s10653-017-9970-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Sparling DW. Organochlorine pesticides. In: Ecotoxicology essentials. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2016. p. 69–107. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-801947-4.00004-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Upadhyay V, Kumari A, Kumar S. From soil to health hazards: heavy metals contamination in northern India and health risk assessment. Chemosphere. 2024;354(4):141697. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2024.141697. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Navnage N, Mallick A, Das A, Pramanik B, Debnath S. Soil reclamation and crop production in arsenic contaminated area using biochar and mycorrhiza. In: Arsenic toxicity remediation. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature Switzerland; 2024. p. 261–80. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-52614-5_13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Jorjanİ S, Pehlİvan Karakaş F. Physiological and biochemical responses to heavy metals stress in plants. Int J Second Metab. 2024;11(1):169–90. doi:10.21448/ijsm.1323494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Ebele AJ, Abou-Elwafa Abdallah M, Harrad S. Pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs) in the freshwater aquatic environment. Emerg Contam. 2017;3(1):1–16. doi:10.1016/j.emcon.2016.12.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Odujebe FO. In-vitro bioaccessibility studies and human risk assessment of potentially toxic elements in contaminated soils and vegetables. Lagos, Nigeria: University of Lagos; 2017. [Google Scholar]

24. Banaee M, Zeidi A, Mikušková N, Faggio C. Assessing metal toxicity on crustaceans in aquatic ecosystems: a comprehensive review. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2024;202(12):5743–61. doi:10.1007/s12011-024-04122-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Liu P, Wu Q, Hu W, Tian K, Huang B, Zhao Y. Effects of atmospheric deposition on heavy metals accumulation in agricultural soils: evidence from field monitoring and Pb isotope analysis. Environ Pollut. 2023;330:121740. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2023.121740. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Hosseini NS, Sobhanardakani S, Cheraghi M, Lorestani B, Merrikhpour H. Heavy metal concentrations in roadside plants (Achillea wilhelmsii and Cardaria draba) and soils along some highways in Hamedan, west of Iran. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2020;27(12):13301–14. doi:10.1007/s11356-020-07874-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Qvarforth A, Lundgren M, Rodushkin I, Engström E, Paulukat C, Hough RL, et al. Future food contaminants: an assessment of the plant uptake of Technology-critical elements versus traditional metal contaminants. Environ Int. 2022;169(5):107504. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2022.107504. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Ahmad W, Alharthy RD, Zubair M, Ahmed M, Hameed A, Rafique S. Toxic and heavy metals contamination assessment in soil and water to evaluate human health risk. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):17006. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-94616-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Raj D, Maiti SK. Sources, bioaccumulation, health risks and remediation of potentially toxic metal(loid)s (As, Cd, Cr, Pb and Hgan epitomised review. Environ Monit Assess. 2020;192(2):108. doi:10.1007/s10661-019-8060-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Priyadarshanee M, Mahto U, Das S. Mechanism of toxicity and adverse health effects of environmental pollutants. In: Microbial biodegradation and bioremediation. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2022. p. 33–53. doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-85455-9.00024-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Budi HS, Catalan Opulencia MJ, Afra A, Abdelbasset WK, Abdullaev D, Majdi A, et al. Source, toxicity and carcinogenic health risk assessment of heavy metals. Rev Environ Health. 2024;39(1):77–90. doi:10.1515/reveh-2022-0096. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Patra A, Khatun N, Mandal T, Rahaman SM, Saha B. Occurrence and speciation of Ni in the environment and the health risk to living organisms. In: Lithium and nickel contamination in plants and the environment. Singapore: World Scientific; 2024. p. 231–62. doi:10.1142/9789811283123_0010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Sager M, Wiche O. Rare earth elements (REEorigins, dispersion, and environmental implications—a comprehensive review. Environments. 2024;11(2):24. doi:10.3390/environments11020024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Begum W, Rai S, Banerjee S, Bhattacharjee S, Mondal MH, Bhattarai A, et al. A comprehensive review on the sources, essentiality and toxicological profile of nickel. RSC Adv. 2022;12(15):9139–53. doi:10.1039/D2RA00378C. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Azeem I, Adeel M, Shakoor N, Zain M, Bibi H, Azeem K, et al. Co-exposure to tire wear particles and nickel inhibits mung bean yield by reducing nutrient uptake. Environ Sci Process Impacts. 2024;26(5):832–42. doi:10.1039/D4EM00070F. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Feng G, Zhou B, Yuan R, Luo S, Gai N, Chen H. Influence of soil composition and environmental factors on the adsorption of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances: a review. Sci Total Environ. 2024;925(12):171785. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.171785. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Abdollahi H, Hosseini Nasab M, Yadollahi A. Bioleaching of lateritic nickel ores. In: Biotechnological innovations in the mineral-metal industry. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2024. p. 41–66. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-43625-3_3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]