Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Calibration and Reliability Analysis of Eccentric Compressive Concrete Column with High Strength Rebars

1 China Communications Construction Co., Ltd., Beijing, 100088, China

2 China Communications Construction Corporation Rail Transit Branch, Beijing, 102200, China

3 China Communications (Tianjin) Rail Transit Investment and Construction Co., Ltd., Tianjin, 300222, China

4 School of Civil Engineering, Fujian University of Technology, Fuzhou, 350118, China

* Corresponding Author: Xiang Liu. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Sustainable and Durable Construction Materials)

Structural Durability & Health Monitoring 2025, 19(5), 1203-1220. https://doi.org/10.32604/sdhm.2025.063813

Received 24 January 2025; Accepted 23 April 2025; Issue published 05 September 2025

Abstract

The utilization of high-strength steel bars (HSSB) within concrete structures demonstrates significant advantages in material conservation and mechanical performance enhancement. Nevertheless, existing design codes exhibit limitations in addressing the distinct statistical characteristics of HSSB, particularly regarding strength design parameters. For instance, GB50010-2010 fails to specify design strength values for reinforcement exceeding 600 MPa, creating technical barriers for advancing HSSB implementation. This study systematically investigates the reliability of eccentric compression concrete columns reinforced with 600 MPa-grade HSSB through high-order moment method analysis. Material partial factors were calibrated against target reliability indices prescribed by GB50068-2018, incorporating critical variables including live-to-dead load ratios, design methodologies, and service conditions. The findings show that the value of k significantly affects the calibration of material partial factors, impacting the reliability of bearing capacity. Considering various k values and target reliability indices, it is recommended that the material partial factor be set at 1.15, implying that the design strength for 600 MPa high-strength steel bars should be considered as 522 MPa. For safety levels I and II, load adjustment factors of 1.1 and 0.9, respectively, may be applied.Keywords

Recent advancements in steel manufacturing technology have enabled construction steel to achieve greater strength and ductility, resulting in high-performance materials that also contribute to material conservation in construction. Steel bars with a yield strength over 500 MPa are typically classified as high-strength steel bars (HSSB). The adoption of HSSBs could influence the mechanical properties of concrete member. Under the same reinforcement ratio, the use of HSSBs will cause a decrease in ductility, but it can reduce the reinforcement ratio to achieve the same ductility and reduce the use of materials. The price of HRB400 grade steel bars is about 5500 yuan/ton, and the price of HRB635 is about 7000 yuan/ton. The cost of HRB635 is about 27% higher than HRB400 grade, but its strength has increased by about 59%. By rational design, construction costs can be reduced.

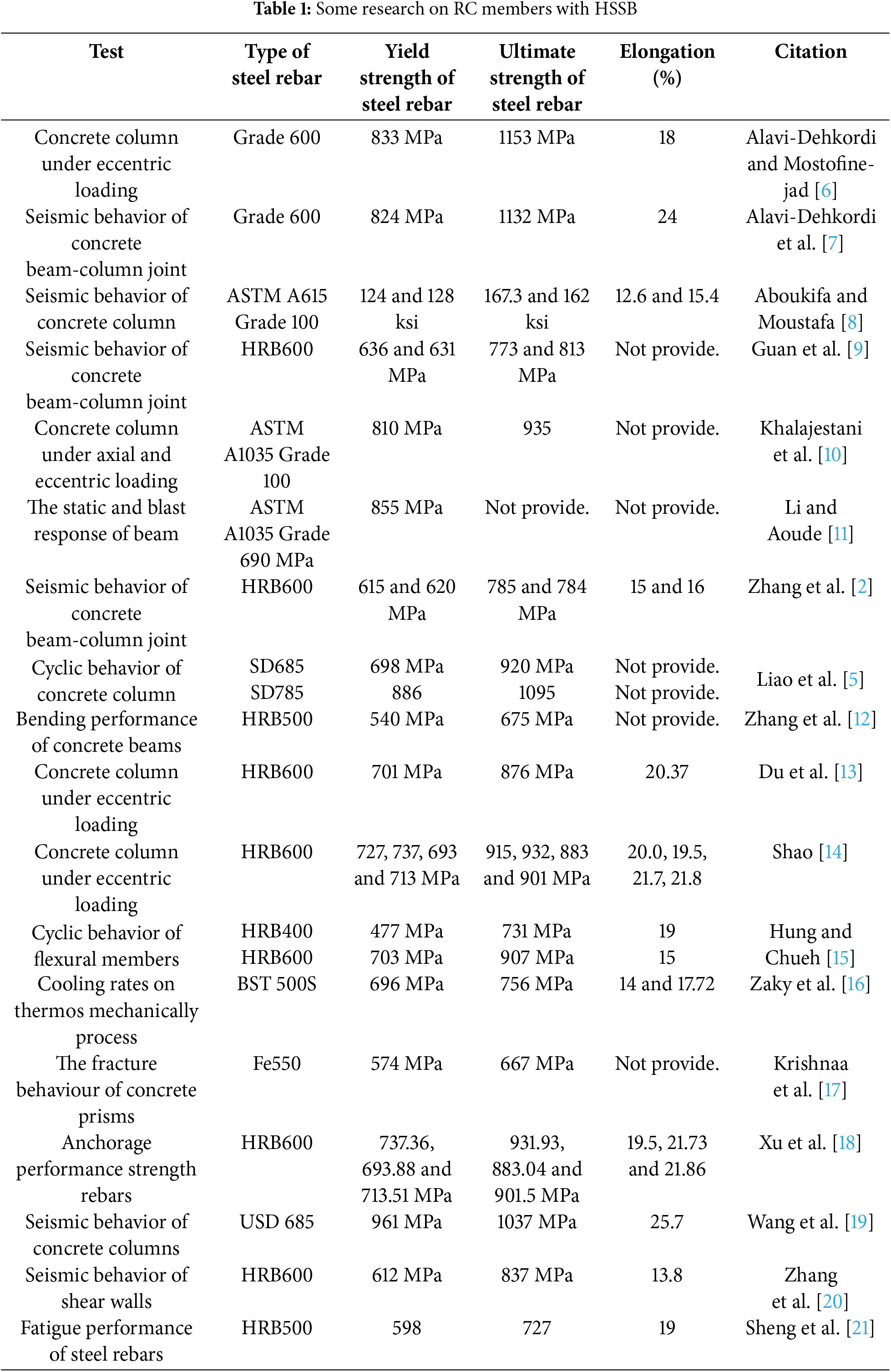

The durability and deformation mode of HSSBs are similar to those of ordinary steel bars [1]. Consequently, researchers have explored the mechanical behavior of concrete elements containing HSSBs. For example, Zhang et al. [2] conducted a study on the seismic performance of concrete beam—column joints that were strengthened. Luo and Li [3] examined the nonlinear behavior of concrete continuous beams with HSSBs, including their ductility and stiffness; Li et al. [4] performed eccentric loading tests on 12 circular tubed reinforced concrete columns, analyzing the effects of parameters such as the diameter to thickness ratio and load eccentricity on damage modes, load carrying capacity and ductility; Liao et al. [5] conducted an experimental study on the cyclic behavior of concrete columns with various transverse reinforcement configurations. Three designs of concrete columns with HSSBs, which included traditional closed-loop hoops, butt-welded loop hoops, and single closed-loop hoops with tie rods, were compared. Further studies on concrete members with HSSBs are listed in Table 1. These research results all indicated that HSSBs have higher yield strength and ultimate strength, and their ductility is also better than ordinary steel bars.

When it comes to the widespread application of new construction materials in building and bridge structures, appropriate technical specifications or guidelines are essential. Regrettably, the current standards for HSSBs are lacking; they either do not exist or rely on existing guidelines, such as guideline GB50010-2010 [22], which does not specify a strength design value for steel bars with strengths above 600 MPa.

The construction process of structures inherently involves variability in material characteristics and component dimensions. Similarly, the live and dead loads that a structure bears during its operation are subject to randomness, affecting the reliability of structural safety. Consequently, modern design methods for buildings and highway bridges adopt the limit state design approach, anchored in reliability as the fundamental principle.

In reliability analysis, the simplest method entails the utilization of Monte Carlo simulation (MCS) to perform reliability assessments. Nevertheless, this method requires a considerably large quantity of samples, resulting in low analysis efficiency. Consequently, numerous researchers have explored various methods to improve reliability analysis efficiency. For example, Chen and Yang [23], as well as Li et al. [24,25], introduced a direct probability integration approach grounded in probability conservation for calculating structural reliability, and this method is characterized by its convenience, efficiency, and accuracy. Tong et al. [26] developed a fourth-order L-moments, and this method is easy to used and has applications in engineering reliability evaluation. Zhang et al. [27,28] developed an efficient outcrossing (GLO) method based on Gauss-Legendre quadrature. The main innovations of this method are twofold: first, it evaluates the cumulative failure probability using weighted sums of outcross rates over a limited number of moments- three to five- thus avoiding the time-consuming numerical integrations that require discretization over a large number of moments. Second, it offers an efficient algorithm to calculate the outcross rate, building on the recently developed system reliability method that draws from the well-established first order reliability method (FORM). Wang et al. [29] introduced a stochastic model that integrates the physical and mechanical models, accounting for the degradation effects of crack development and corrosion progression to estimate the failure probability of reinforced concrete structures over time. Tran et al. [30] developed an effective reliability analysis program and suggested a structural resistance factor for designing a steel-concrete composite frame system consisting of steel tube concrete columns and composite beams.

Nowadays, the limit state function method is the most commonly used design method in building and bridge construction [31,32]. To assess the reliability of structural design, the partial safety factor format (PSFF) and resistance reduction factor format (RRFF) are predominantly utilized. For instance, Zhang et al. [33] analyzed the flexural strength reliability of steel-fiber reinforced plastics beams and proposed material partial factors for FRP bars in such beams. Similarly, Zhang et al. [12] investigated the flexural performance of a concrete beam incorporating HSSBs and, based on reliability theory, the bearing capacity reduction factor for the beam was proposed.

Concrete columns have traditionally been designed as principal components, with eccentric compression being one of the main force modes for columns. Columns require higher reliability compared to beams, slabs, and other components. Therefore, the reliability of the reinforced concrete (RC) column with HSSB under eccentric compression was analyzed to propose the material partial factor for HSSB, offering a theoretical foundation for for the promotion of HSSB.

2 Resistance Model for Ultimate Force of HSSBCC under Eccentric Compression

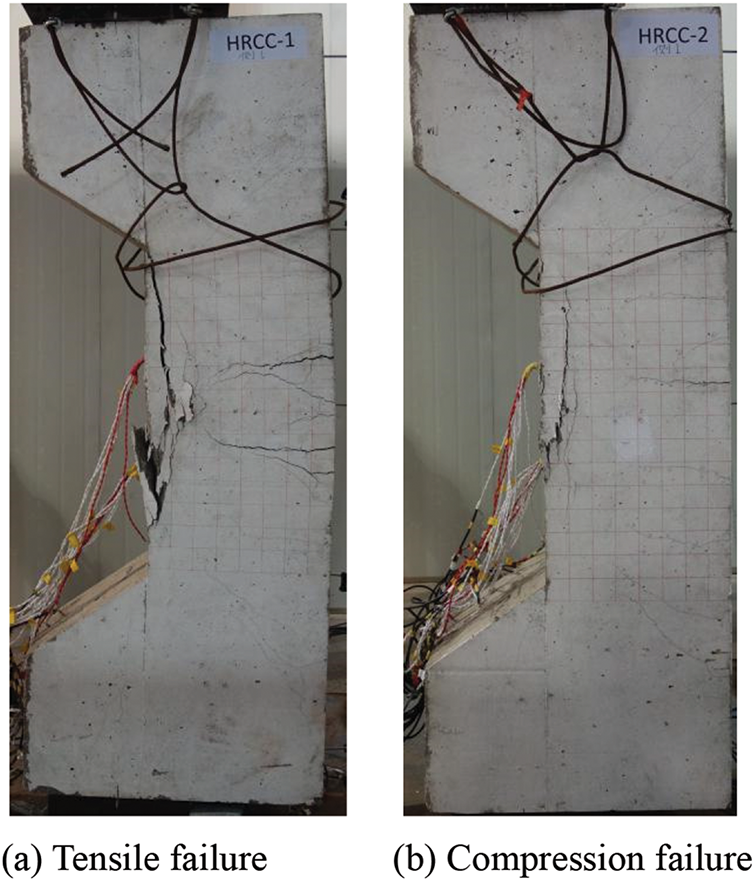

Currently, the bearing capacity design of reinforced concrete columns is mainly applies the limit state method, and guidelines provide specific provisions for the eccentric bearing capacity design of RC columns. The failure mode of a RC column under eccentric loading with HSSB is similar to that of with ordinary steel rebars, as shown in Fig. 1, therefore the calculation method recommended in GB50010-2010 [22] is employed.

Figure 1: Typical failure modes of RC column with HSSB under eccentric compression

When the length of the member is relatively long, and the second-order effect is significant due to a larger axial compression ratio in the eccentric compression member, it is essential to consider the P-δ effect in the section design. The design value for the bending moment of the eccentric compression concrete column, considering the P-δ effect, can be expressed as follows [22]:

where Cm is the eccentricity adjustment coefficient.

There are two failure mode of large eccentric compression failure or small eccentric compression failure, depending on the design scheme and loading conditions. The calculation formula for large eccentric compression failure is as follows:

where α1 represents the coefficient, fc denotes the standard value of concrete strength, b stands for the width of the section. Additionally,

with

where e0 is the initial eccentricity.

The calculation formula of small eccentric compression failure is as follows:

where σs is the stress of the tensile steel bar, which can be determined by the strain εs of the tensile steel bar from the assumption of the plane section, and then determined by

3 Estimation of the Statistical Parameters of the Resistance Models

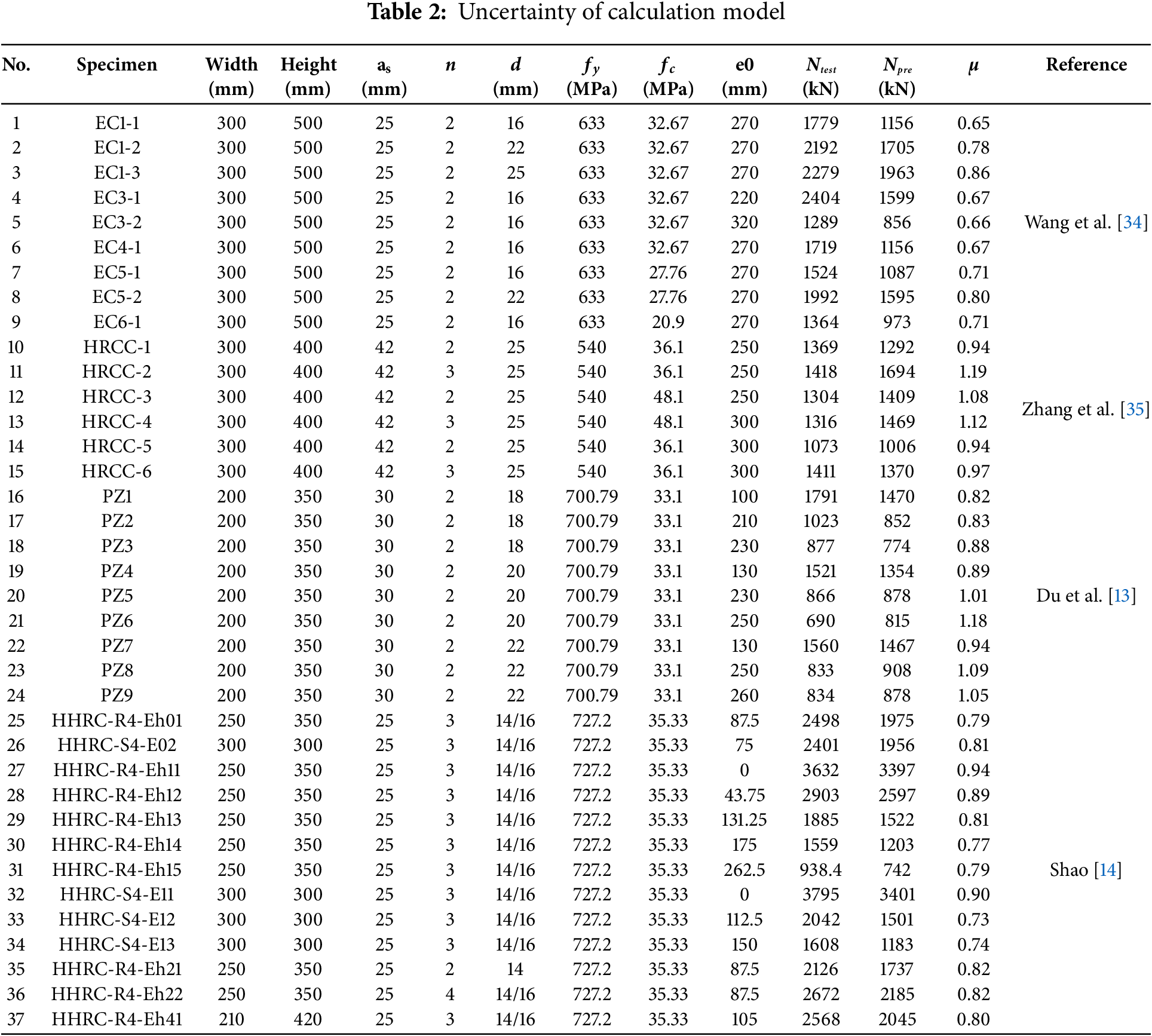

Structural engineering, being a blend of empirical and theoretical approaches, relies on certain fundamental assumptions for calculating the eccentric compressive capacity of RC columns. Coefficients derived from experimental data introduce uncertainties into the calculation mode, making the calculation error a stochastic variable. To ascertain the statistical characteristics of uncertainty and model error in the calculation mode for the eccentric compressive capacity of RCCs with HSSB, 37 datasets were analyzed, as presented in Table 2. The model error μ can be expressed as [33]:

where Ntest and Npre denote the test value and theoretical value of concrete column under eccentric compression.

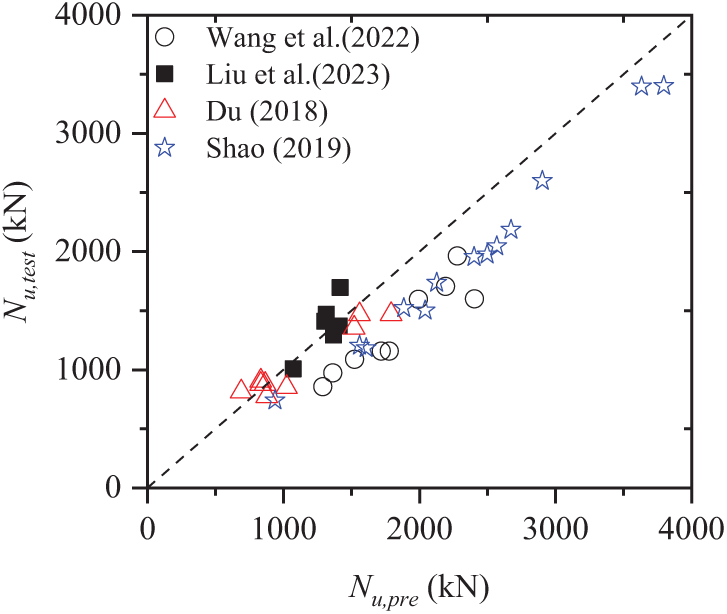

The comparison between the experimental results and the theoretical estimations is illustrated in Fig. 2. Most of the results obtained by the bearing capacity calculation formulas (predicted values) are larger than the real values (test values). Among the 37 samples, only 7 samples had predicted values that were lower than the measured values. This indicates that the prediction model shows a trend of producing unsafe estimates.

Figure 2: Comparison between predicted model calculation results and experimental results [4,14,18,34]

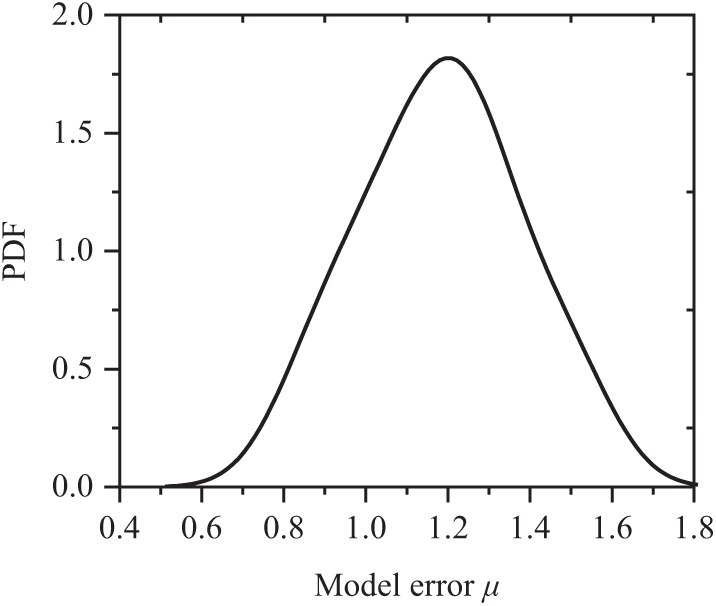

Fig. 3 displays the probability density function (PDF) of the model error μ, which follows a distribution with a mean value of 1.18, a standard deviation of 0.19, and a coefficient of variation of 0.16. Compared to bending components, the model for the compressive capacity of RC concrete shows more variability when using HSSB [12].

Figure 3: PDF of model error

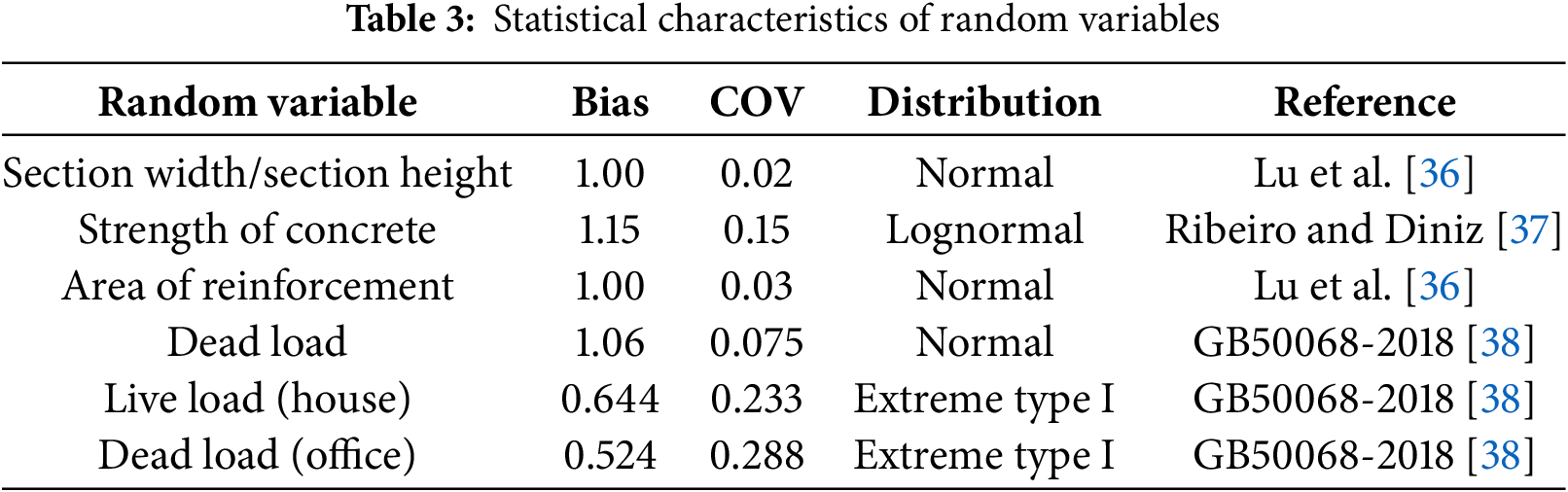

In the limit state design approach for reinforced concrete elements, the randomness primarily arises from two aspects: structural parameters and load variables. In the estimation of the eccentric compressive bearing capacity of RC columns, variables such as cross-sectional size, concrete strength, reinforcement strength, reinforcement area, eccentricity, and slenderness ratio have most influence on the bearing capacity. Thus, cross-sectional size, concrete strength, reinforcement strength, and reinforcement area are treated as random variables. For load parameters, including dead and live loads, both are also regarded as random variables. Based on the compiled data in Table 2, the yield strength bias of HSSB is 1.17, with a coefficient of variation of 0.096. The statistical details for each random variable are provided in Table 3.

4.1 Statistical Moment Calculation

Suppose p(x) denotes the probability density function of a continuous random variable Y = G(X). As defined in [39], its mean value M1 and k-th central moments Mk are expressed as follows:

As the random variable Y includes multiple variables, the statistical moments of G(X) cannot be acquired directly. In such instances, dimensionality reduction is performed as described in Rahman and Xu [40]. When a function contains n random variables, it can be resolved into s-dimensional random variable functions Gs(X), as shown below:

where s < n, and

When s = 2, the multivariate function problem is transformed into a problem of combining multiple univariate functions, and then Eq. (14) transform to the following formula:

with

This indicates that except the i-th variable, all other variables maintain their corresponding values at the reference point.

Through the substituting Eq. (15) into Eqs. (12) and (13), the statistical moment of the dimensionality reduced random variable Y can be obtained as follows:

When the random variables in G(X) follow a normal distribution,

where r represents the number of integration point; xGH,l and wGH,l denote the integration point and the weight of Gaussian-Hermite, respectively, with detailed values available in references.

For s = 2, the multivariate function problem reduces to combining univariate functions, and then Eq. (14) transform to the following formula [39]:

where Mz denotes the z-th central moment; α3 and α4 respectively stand for the skewness coefficient and the kurtosis coefficien; g(uc) denotes the response value under the condition that all random parameters take values corresponding to the reference point; g(Xk, uc) denotes response value when k-th parameter is considered as random variable while the others are set to their reference values; g(Xl, Xm, uc) denotes response value when l-th and m-th parameters are considered as random variable while the others are corresponding to the reference point.

4.2 Calculation of Reliability Index

The failure probability Pf can be expressed as a function of the fourth order moment reliability index β4M function based on the center moment of the first four moments of the limit state function, and it can be written as [39]:

where Φ(·) represents the cumulative distribution function for the standard normal distribution, and the detail calculation formula of β4M can be found in Zhao and Lu [39], and this method can also be termed high order moment method (HOMM).

Before analyzing the reliability of the structure, a limit state function is neccessary to be established, and its fundamental expression is presented below:

where R is resistance, and it can satisfy Eqs. (1)–(10); γG and γQ represents the partial factor of dead load and live load, respectively; SGk and SQk respectively represents the standard values of dead load and live load, and they can be given as follows:

where Sd is the standard value of load, and k denotes the ratio of live load to dead load.

5 Analysis of Reliability and Partial Factor

According to Eqs. (1) to (7), the prediction value of the bearing capacity of eccentrically compressed RC columns with HSSBs can be determined, and the moment values of limit state function can be calculated by Eqs. (14) to (22) and Eqs. (24) and (25). Then the reliability index and failure probability can be obtained by Eq. (23).

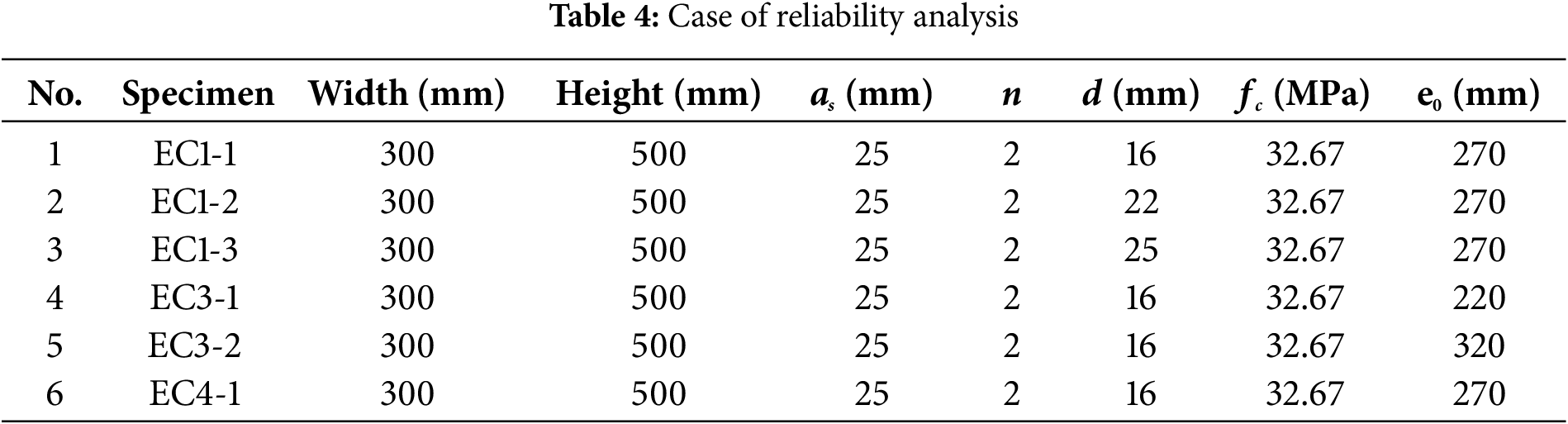

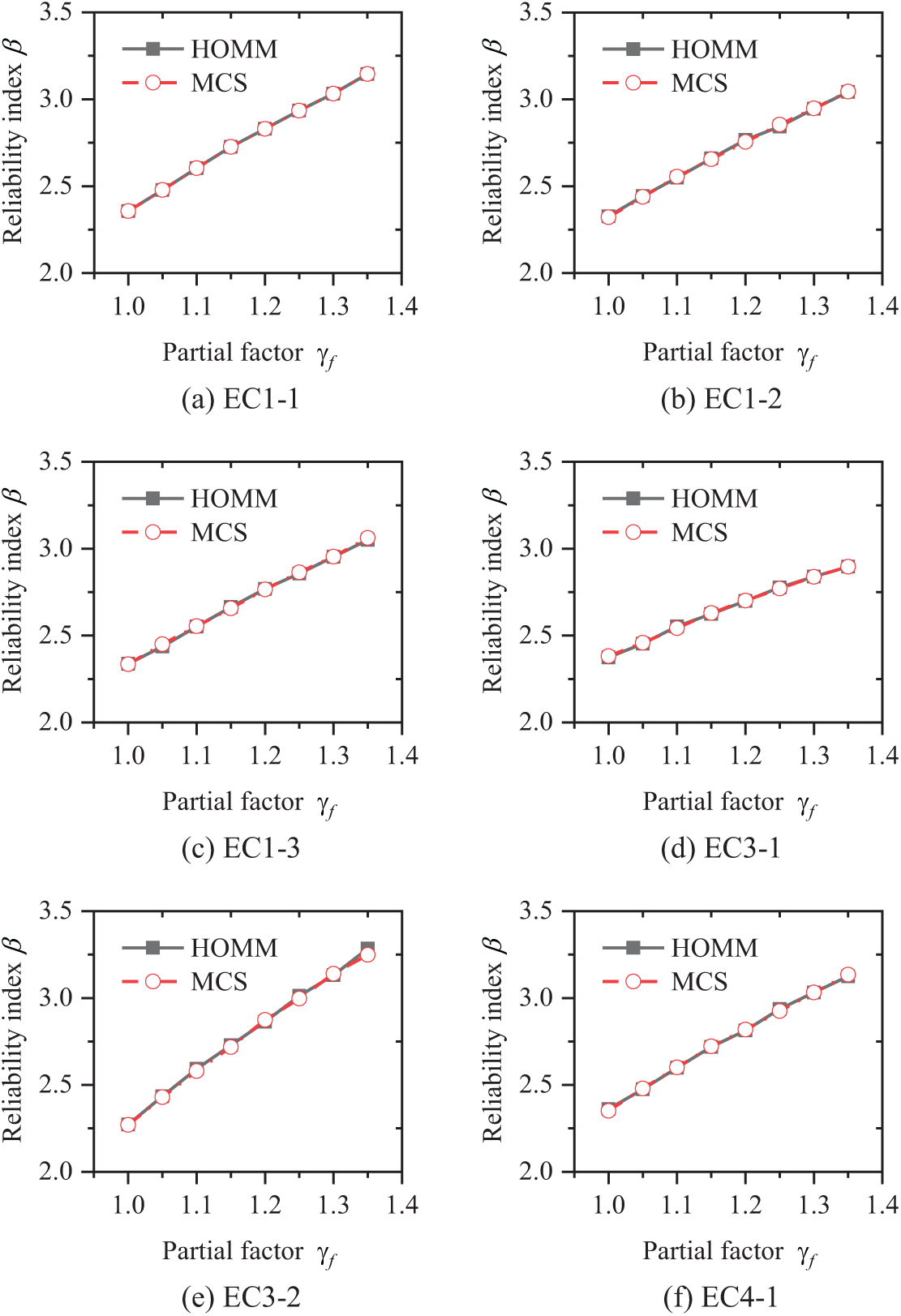

The precision of the methods used for reliability calculations plays a significant role in the dependability of reliability analysis. Considering six cross-sections as examples, presented in Table 4, the reliability of RC cross-sections under eccentric loads was calculated using the HOMM, and these results are compared with those obtained from the Monte Carlo simulation (MCS) method. While MCS is a straightforward and precise method for reliability calculations, it necessitates a significant sample size for accurate outcomes. Moreover, this section will explore the material partial factors for HSSB, the value of k, and how varying load conditions (house load or office) affect the reliability indexes.

The reliability indices computed by HOMM and MCS are displayed in Fig. 4. It is evident that the reliability indices from HOMM are in agreement with those from MCS, affirming the method’s accuracy. Furthermore, it is observed that for different design sections, the reliability index exhibits a linear increase with the rise in material partial factors, and this is because the increase in partial factor leads to a greater actual bearing capacity, which is consistent with the results in the literatures [41,42].

Figure 4: Calculation result from HOMM and MCS

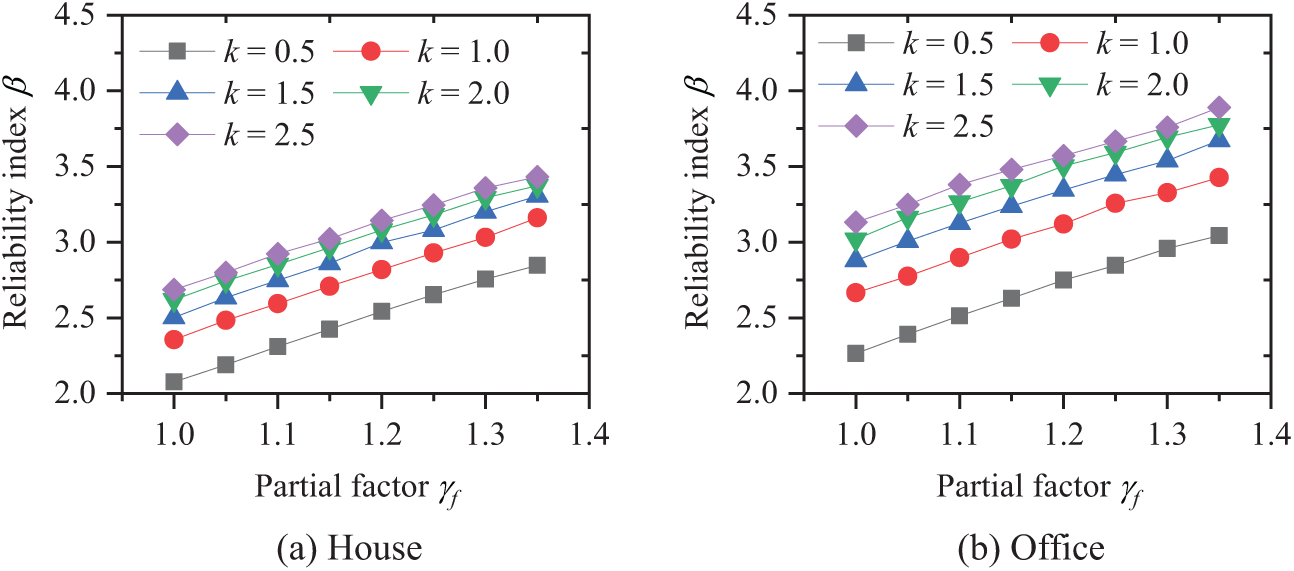

Fig. 5 illustrates the reliability indices for varying k values and material partial factors, considering both house load and office loads. In different scenarios, the reliability index similarly shows a linear upward trend with the increase in material partial factors. Additionally, the reliability index increases with higher k values, indicating that the distribution ratio of lateral to live load in the design significantly influences reliability.

Figure 5: Reliability indexes under various k values

5.2 Calibration of Material Partial Factor

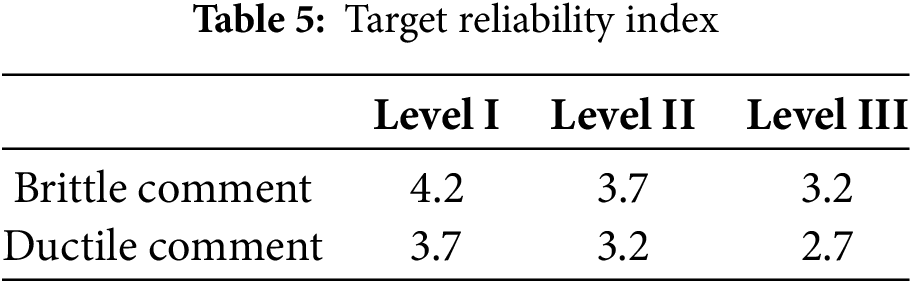

Structural safety and economy are often seen as conflicting factors in design. A high reliability index may lead to an excessive structural surplus, indicating a compromise in economic efficiency. Conversely, a low reliability index may risk structural safety. Design guidelines often differentiate target reliability indices based on the importance level of the results, as specified in GB5068-2018 [38], which is detailed in Table 5.

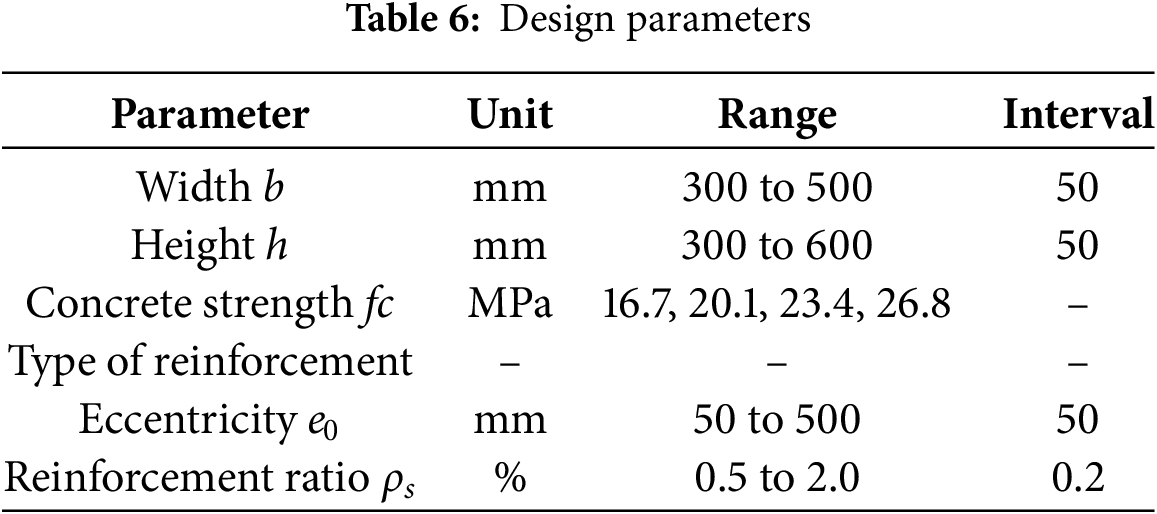

To determine the optimal material partial factors, multiple eccentrically loaded RC rectangular sections were designed, with parameters listed in Table 6. These parameters encompass five section widths, seven section heights, four concrete strength classes, ten eccentricities, and eight reinforcement ratios, yielding a total of 5 × 7 × 4 × 10 × 8 = 11,200 cases. For each set of parameters under identical conditions, a reliability index is calculated, resulting in 11,200 reliability indices. To calibrate the material partial factors, the following index can be utilized [33]:

where βi and βT represents the calculated reliability index and the target reliability index, respectively, and the value of βT can be found in Table 5; n represents the number of calculated cases. As the calibration value decreases, the reliability index associated with the material partial factor progressively converges toward the target reliability index, and its value is more reasonable.

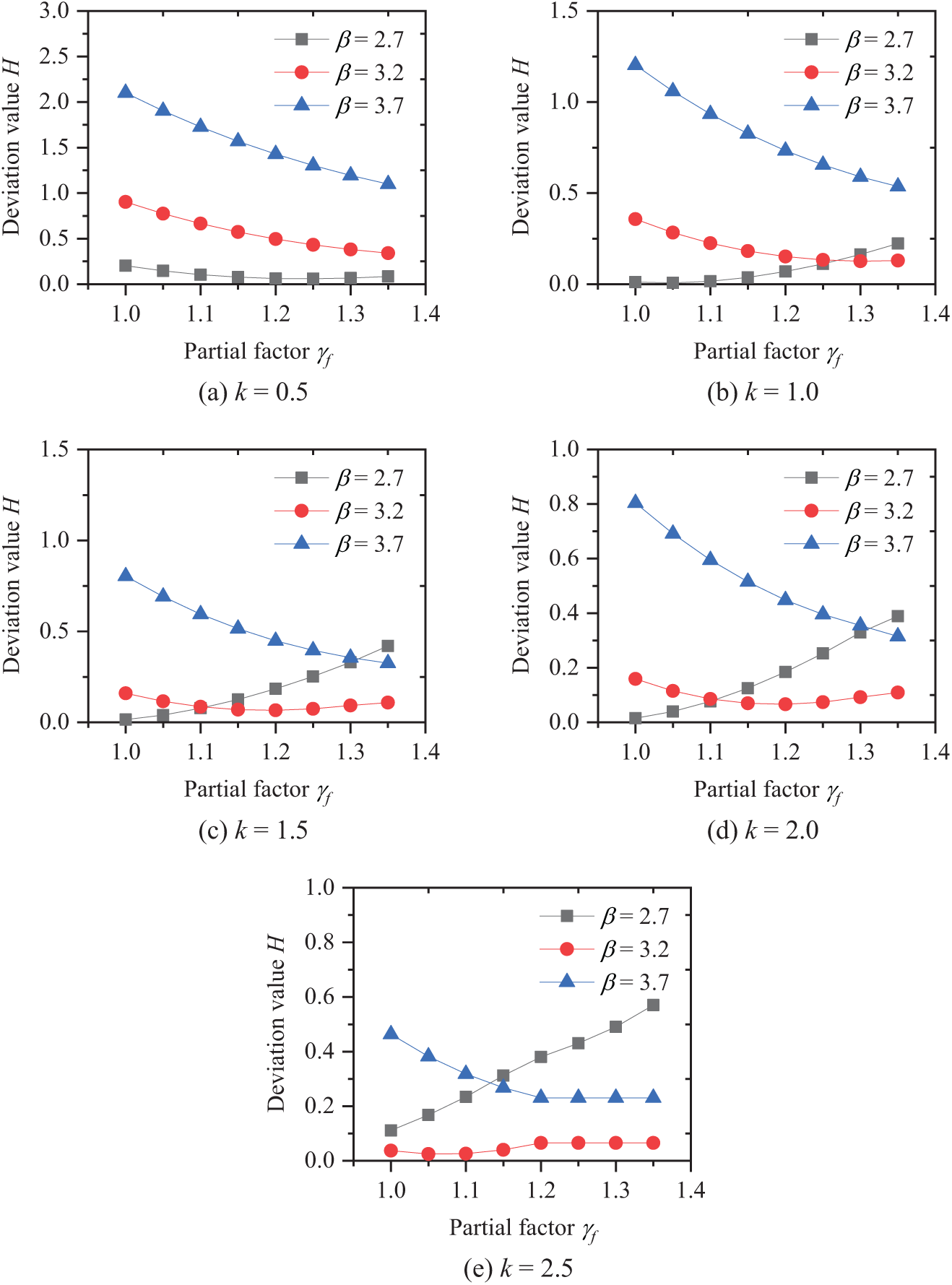

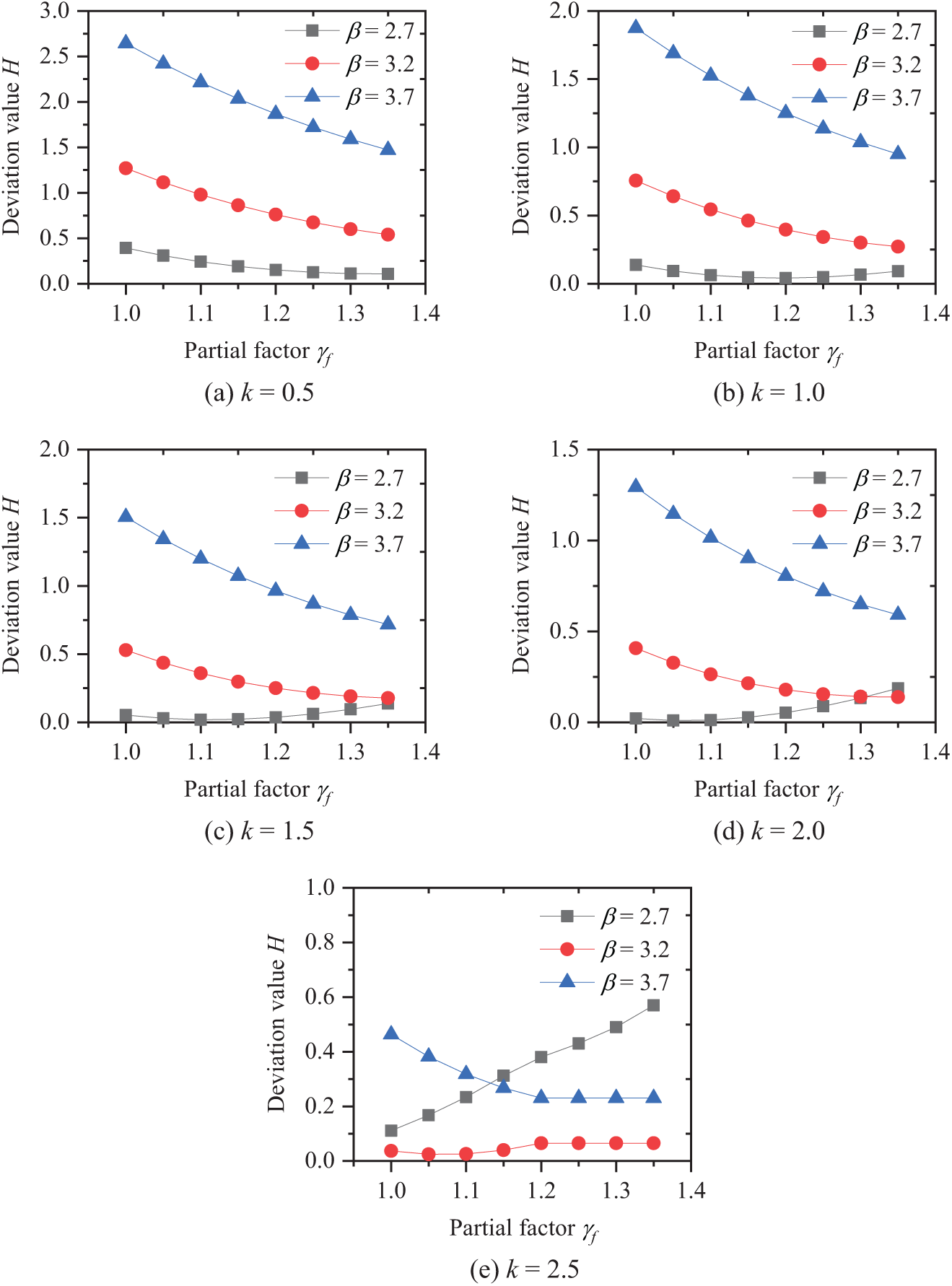

Separate assessments for house and office loading conditions were conducted to ascertain the optimal material partial factor, with these factors ranging from 1.0 to 1.35 at increments of 0.05. The considered k values were 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0, and 2.5. The calibration results are presented in Figs. 6 and 7.

Figure 6: Calibration for partial factor of office condition

Figure 7: Calibration for partial factor of house condition

According to Fig. 6, the value of k significantly influences the calibration of reliability indices. At k = 0.5, the calibration values for target reliabilities of 3.2 and 3.7 decrease with increasing material partial factors, while for a target reliability of 2.7, the calibration values initially decrease and then increase, with the lowest value occurring at approximately 1.15. At k = 1.0, the calibration values for target reliabilities of 3.2 and 3.7 decrease with increasing material partial factors, whereas for a target reliability of 2.7, they increase with increasing material partial factors. At k = 1.5, the calibration value for a target reliability of 3.2 initially declines and then rises with a rise in the material partial factor, reaching its minimum at around 1.18. For a target reliability of 2.7, the calibration value increases, while for a target reliability of 3.7, it decreases with increasing material partial factor. At k = 2.0 and 2.5, the calibration values of the reliability indices are similar to those observed at k = 1.5.

Fig. 7 shows the situation for house loading. Similarly, the value of k has a significant impact on the calibration of reliability indices. At k = 0.5, the calibration values of different target reliabilities increase with the material partial factor. At k = 1.0, the calibration values for target reliabilities of 3.2 and 3.7 decrease with increasing material partial factors, while those for a target reliability of 2.7 initially decrease and then increase, with the lowest value occurring at approximately 1.15. At k = 1.5, the calibration value for a target reliability of 3.2 shows a similar pattern of initial decrease and subsequent increase, with the lowest value at around 1.18. For a target reliability of 2.7, the calibration value increases, while for a target reliability of 3.7, it decreases with increasing material partial factors. At k = 2.0 and 2.5, the calibration values follow the pattern observed at k = 1.5.

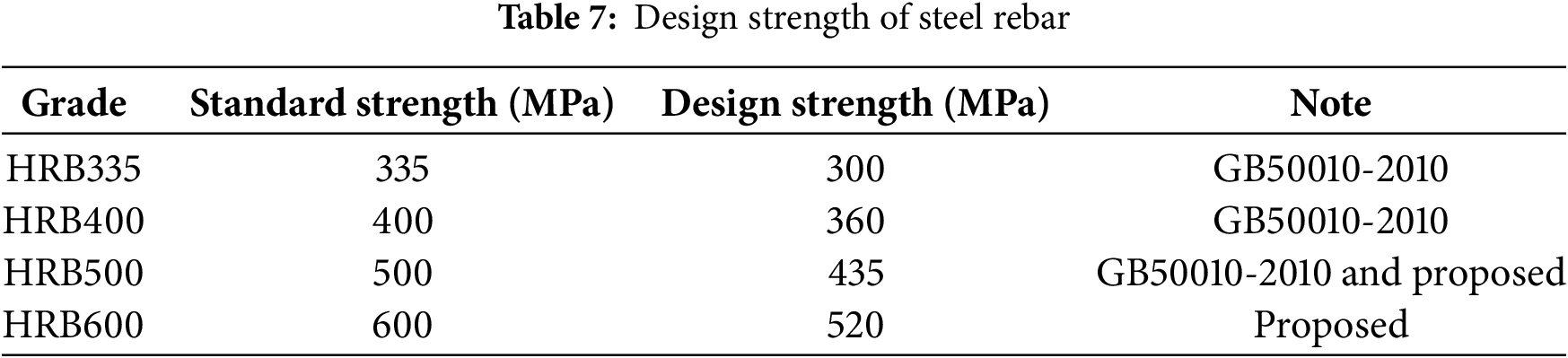

Based on the calculations, it is recommended to set the material partial factor at 1.15 for a target reliability index of 3.2. For cases with reliability indices of 2.7 and 3.7, it is advisable to refer to the specifications and apply load effect amplification factors of 0.9 and 1.1, respectively. According to the material partial factor, the strength design value of corresponding high-strength reinforcement can be obtained as shown in Table 7.

(1) HOMM has high accuracy and computational efficiency in calculating reliability indexes, and it is easy to use, and it can be widely applied in reliability analysis of other types of concrete structures.

(2) The material partial factor of HRB335 and HRB400 in the code GB50010-2010 is about 1.11, and their strength design values are 300 and 360 MPa, respectively; Regarding axial compressive strength, the compressive strength design value for HRB500 and HRBF500 reinforcement is 400 MPa, with a partial factor of 1.25. Conversely, other cases have a design strength of 435 MPa and a partial factor of 1.15. These results are in line with those presented in this paper, though the 1.25 partial factor is viewed as quite conservative. For reinforcement with standard tensile strength of 600 MPa, the recommended strength design value is 520 MPa, as shown in Table 7.

(3) It is important to mention that the proposed partial factors for HSSB were derived from the bearing capacity of eccentrically compressed RC columns. Additional investigations are required to verify whether member under other states are also applicable.

(4) The coefficient of variation of high-performance steel bars is inconsistent with that of ordinary steel bars, resulting in inconsistent partial factor. This research provides some reference for the calibration strategy of partial factor for other high-performance materials.

To enhance the application of HSSB concrete, this study addressed the uncertainty in the approach used to determine the load-bearing capacity of RC columns with HSSB under eccentric compression. The uncertainties of other parameters were also collected. A limit state function was formulated, taking into account various ratios of dead load to live load. The HOMM was employed to evaluate the reliability of the bearing capacity of reinforced concrete columns under eccentric compression, and its accuracy was validated. Extensive case studies were conducted to determine the calibration values for material partial factors under different dead-to-live load ratios and usage conditions, leading to the identification of optimal factors. The main conclusions are as follows:

(1) For RC columns with HSSB under eccentric compression, the calculation method’s uncertainty is represented by a normal distribution, with parameters including a mean of 1.18, a standard deviation of 0.19, and a coefficient of variation of 0.16.

(2) The HOMM has proven to be both efficient and accurate in calculating the reliability of the bearing capacity for eccentrically compressed RC columns with HSSB when compared to MCS.

(3) The reliability of the bearing capacity of reinforced concrete columns is greatly affected by the ratio of dead load to live load. As this ratio rises, the reliability index typically becomes higher. Additionally, an increase in the material partial factor leads to a linear increase in the reliability index.

(4) Based on the computational results, it is advised that the material partial factor be set according to a target reliability index of 3.2, which is recommended to be 1.15. For cases with reliability indices of 2.7 and 3.7, it is appropriate to consult the specifications and apply load effect amplification factors of 0.9 and 1.1, respectively.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The work described in this paper is supported by grants from the Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province (Grant No. 2022J05184).

Author Contributions: Baojun Qin: Performed the review, wrote the manuscript. Hong Jiang: Detailed check of the text and references, editorial contribution. Wei Zhang: Detailed check of the text and references, editorial contribution. Xiang Liu: Planned and organized the paper, performed the review, wrote the manuscript, performed editorial tasks, organized the tasks, served as a corresponding author. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Available upon request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Xiao Z, Wei H, Wu T, Ren W, Li X. Flexural behavior and serviceability of steel fiber-reinforced lightweight aggregate concrete beams reinforced with high-strength steel bars. Constr Build Mater. 2024;437(8):136977. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.136977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Zhang X, Rong X, Shi X, Zhang J. Experimental evaluation on the seismic performance of high-strength reinforcement beam-column joints with different parameters. Structures. 2023;51(6):1591–608. doi:10.1016/j.istruc.2023.03.100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Luo D, Li B. Moment redistribution capacity of continuous RC beams with High-Strength steel reinforcement. Structures. 2023;51(5):13–24. doi:10.1016/j.istruc.2023.03.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Li X, Liu J, Wang X, Chen YF. Behavior of eccentrically-loaded tubed reinforced concrete short columns with high-strength concrete and reinforcement. Constr Build Mater. 2023;378(4):131148. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.131148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Liao WC, Perceka W, Wang M. Experimental study of cyclic behavior of high-strength reinforced concrete columns with different transverse reinforcement detailing configurations. Eng Struct. 2017;153(1):290–301. doi:10.1016/j.engstruct.2017.10.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Alavi-Dehkordi S, Mostofinejad D. Behavior of concrete columns reinforced with high-strength steel rebars under eccentric loading. Mater Struct. 2018;51(6):145. doi:10.1617/s11527-018-1271-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Alavi-Dehkordi S, Mostofinejad D, Alaee P. Effects of high-strength reinforcing bars and concrete on seismic behavior of RC beam-column joints. Eng Struct. 2019;183(1):702–19. doi:10.1016/j.engstruct.2019.01.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Aboukifa M, Moustafa MA. Experimental seismic behavior of ultra-high performance concrete columns with high strength steel reinforcement. Eng Struct. 2021;232(2):111885. doi:10.1016/j.engstruct.2021.111885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Guan D, Guo Z, Jiang C, Yang S, Yang H. Experimental evaluation of precast concrete beam-column connections with high-strength steel rebars. KSCE J Civ Eng. 2019;23(1):238–50. doi:10.1007/s12205-018-1807-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Khalajestani MK, Parvez A, Foster SJ, Valipour H, McGregor G. Concentrically and eccentrically loaded high-strength concrete columns with high-strength reinforcement: an experimental study. Eng Struct. 2021;248(2):113251. doi:10.1016/j.engstruct.2021.113251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Li Y, Aoude H. Influence of steel fibers on the static and blast response of beams built with high-strength concrete and high-strength reinforcement. Eng Struct. 2020;221:111031. doi:10.1016/j.engstruct.2020.111031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Zhang F, Feng F, Liu X. Reliability analysis of concrete beam with high-strength steel reinforcement. Materials. 2022;15(24):8999. doi:10.3390/ma15248999. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Du H. Experimental study on mechanical performance of HRB600 RC eccentrically loaded columns [master’s thesis]. Tianjin, China: Hebei University of Technology; 2018. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

14. Shao X. Research on experiment behavior and calculation method of RC columns embedded with 600MPa high strength steel bars under axial and eccentric compression [master’s thesis]. Hefei, China: Hefei University of Technology; 2019. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

15. Hung CC, Chueh CY. Cyclic behavior of UHPFRC flexural members reinforced with high-strength steel rebar. Eng Struct. 2016;122(6):108–20. doi:10.1016/j.engstruct.2016.05.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Zaky AI, El-Morsy A, El-Bitar T. Effect of different cooling rates on thermomechanically processed high-strength rebar steel. J Mater Process Technol. 2009;209(3):1565–9. doi:10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2008.04.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Krishnaa S, Veerendar C, Suriya Prakash S, Kawasaki Y. Evaluation of the fracture behaviour of concrete prisms reinforced with regular and high-strength steel rebars using acoustic emission technique. Constr Build Mater. 2023;402(5):132983. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.132983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Xu Q, Wang J, Ding Z, Xia J, Rasa AR, Shen Q. Experimental investigation and analysis on anchorage performance of 635 MPa hot-rolled ribbed high strength rebars. Structures. 2021;30(5):574–84. doi:10.1016/j.istruc.2020.12.081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Wang JH, Sun YP, Takeuchi T, Koyama T. Seismic behavior of circular fly ash concrete columns reinforced with low-bond high-strength steel rebar. Structures. 2020;27(1):1335–57. doi:10.1016/j.istruc.2020.07.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Zhang J, Liu J, Li X, Cao W. Seismic behavior of steel fiber-reinforced high-strength concrete mid-rise shear walls with high-strength steel rebar. J Build Eng. 2021;42(2):102462. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2021.102462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Sheng XW, Zheng WQ, Yang Y. Tensile and high-cycle fatigue performance of HRB500 high-strength steel rebars joined by flash butt welding. Constr Build Mater. 2020;241(6):118037. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.118037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Code for design of concrete structures. GB50010-2010. Beijing, China: China Architecture & Building Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

23. Chen G, Yang D. A unified analysis framework of static and dynamic structural reliabilities based on direct probability integral method. Mech Syst Signal Process. 2021;158:107783. doi:10.1016/j.ymssp.2021.107783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Li L, Chen G, Fang M, Yang D. Reliability analysis of structures with multimodal distributions based on direct probability integral method. Reliab Eng Syst Saf. 2021;215(1):107885. doi:10.1016/j.ress.2021.107885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Li X, Chen G, Cui H, Yang D. Direct probability integral method for static and dynamic reliability analysis of structures with complicated performance functions. Comput Meth Appl Mech Eng. 2021;374:113583. doi:10.1016/j.cma.2020.113583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Tong MN, Zhao YG, Lu ZH. Normal transformation for correlated random variables based on L-moments and its application in reliability engineering. Reliab Eng Syst Saf. 2021;207(6):107334. doi:10.1016/j.ress.2020.107334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Zhang XY, Lu ZH, Zhao YG, Li CQ. The GLO method: an efficient algorithm for time-dependent reliability analysis based on outcrossing rate. Struct Saf. 2022;97(12):102204. doi:10.1016/j.strusafe.2022.102204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Zhang XY, Lu ZH, Zhao YG, Li CQ. Conditional time-dependent limit state function model considering damages and its application in reliability evaluation of CRTS II track slab. Appl Math Model. 2022;101(1):654–72. doi:10.1016/j.apm.2021.09.018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Wang T, Li C, Zheng JJ, Hackl J, Luan Y, Ishida T, et al. Consideration of coupling of crack development and corrosion in assessing the reliability of reinforced concrete beams subjected to bending. Reliab Eng Syst Saf. 2023;233:109095. doi:10.1016/j.ress.2023.109095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Tran H, Thai HT, Uy B, Hicks SJ, Kang WH. System reliability-based design of steel-concrete composite frames with CFST columns and composite beams. J Constr Steel Res. 2022;194:107298. doi:10.1016/j.jcsr.2022.107298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Gauron O, Saidou A, Busson A, Siqueira GH, Paultre P. Experimental determination of the lateral stability and shear failure limit states of bridge rubber bearings. Eng Struct. 2018;174(13):39–48. doi:10.1016/j.engstruct.2018.07.039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Kalfas KN, Ghorbani Amirabad N, Forcellini D. The role of shear modulus on the mechanical behavior of elastomeric bearings when subjected to combined axial and shear loads. Eng Struct. 2021;248(6):113248. doi:10.1016/j.engstruct.2021.113248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Zhang W, Liu X, Huang Y, Tong MN. Reliability-based analysis of the flexural strength of concrete beams reinforced with hybrid BFRP and steel rebars. Arch Civ Mech Eng. 2022;22(4):171. doi:10.1007/s43452-022-00493-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Wang Y-H, Tian Q-L, Lan G-Q. Experimental research on the mechanical properties of concrete column reinforced with 630 MPa high-strength steel under large eccentric loading. J Jilin Univ (Eng Technol Edit). 2022;52(11):2626–35. doi:10.13229/j.cnki.jdxbgxb20210321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Zhang F, Liu X, Ge FW, Cui C. Investigation on the ductility capacity of concrete columns with high strength steel reinforcement under eccentric loading. Materials. 2023;16(12):4389. doi:10.3390/ma16124389. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Lu R, Luo Y, Conte JP. Reliability evaluation of reinforced concrete beams. Struct Saf. 1994;14(4):277–98. doi:10.1016/0167-4730(94)90016-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Ribeiro SEC, Diniz SMC. Reliability-based design recommendations for FRP-reinforced concrete beams. Eng Struct. 2013;52:273–83. doi:10.1016/j.engstruct.2013.02.026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. GB 50068-2018. Unified standard for reliability design of building structures. Beijing, China: China Standard Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

39. Zhao Y-G, Lu Z-H. Structural reliability: approaches from perspectives of statistical moments. Hoboken, NJ, USA: Wiley-Blackwell; 2021. [Google Scholar]

40. Rahman S, Xu H. A univariate dimension-reduction method for multi-dimensional integration in stochastic mechanics. Probab Eng Mech. 2004;19(4):393–408. doi:10.1016/j.probengmech.2004.04.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Huang X, Zhou Y, Li W, Hu B, Zhang J. Reliability-based design of FRP shear strengthened reinforced concrete Beams: guidelines assessment and calibration. Compos Struct. 2023;323(4):117421. doi:10.1016/j.compstruct.2023.117421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Tarawneh A, Alajarmeh O, Alawadi R, Amirah H, Alramadeen R. Database evaluation and reliability calibration for flexural strength of hybrid FRP/steel-RC Beams. Compos Struct. 2024;329(6):117758. doi:10.1016/j.compstruct.2023.117758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools