Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Intelligent Concrete Defect Identification Using an Attention-Enhanced VGG16-U-Net

School of Civil Engineering, Architecture and Environment, Hubei University of Technology, Wuhan, 430068, China

* Corresponding Author: Caiping Huang. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Sensing Data Based Structural Health Monitoring in Engineering)

Structural Durability & Health Monitoring 2025, 19(5), 1287-1304. https://doi.org/10.32604/sdhm.2025.065930

Received 25 March 2025; Accepted 19 May 2025; Issue published 05 September 2025

Abstract

Semantic segmentation of concrete bridge defect images frequently encounters challenges due to insufficient precision and the limited computational capabilities of mobile devices, thereby considerably affecting the reliability of bridge defect monitoring and health assessment. To tackle these issues, a concrete defects dataset (including spalling, crack, and exposed steel rebar) was curated and multiple semantic segmentation models were developed. In these models, a deep convolutional network or a lightweight convolutional network were employed as the backbone feature extraction networks, with different loss functions configured and various attention mechanism modules introduced for conducting multi-angle comparative research. The comparison of results indicates that utilizing VGG16 as the backbone network of U-Net for semantic segmentation of multi-class concrete defects images resulted in the highest recognition accuracy, achieving a Mean Intersection over Union (MIoU) of 80.37% and a Mean Pixel Accuracy (MPA) of 90.03%. The optimal combination of loss functions was found to be Focal loss and Dice loss. The lightweight convolutional network MobileNetV2-DeeplabV3 slightly reduced recognition accuracy but significantly decreased the number of parameters, resulting in a faster detection speed of 71.87 frames/s, making it suitable for real-time defect detection. After integrating the SE (Squeeze-and-Excitation), CBAM (Convolutional Block Attention Module), and Coordinate Attention (CA) modules, both VGG16-U-Net and MobileNetV2-DeeplabV3 achieved improved recognition accuracy. Among them, the CA module (Coordinate Attention) effectively guides the model to accurately identify subtle concrete defects. The improved VGG16-U-Net can identify previously the new untrained concrete defect images in the concrete structural health monitoring (SHM) system, and the recognition accuracy can meet the demand for intelligent defect image recognition for structural health monitoring of concrete structures.Keywords

Computer vision involves using computers to simulate human visual functions, extract information from image, process it, and apply it in the areas of detection, measurement, and control. The three primary tasks in computer vision encompass image classification, object detection, and semantic segmentation. Image classification involves the process of categorizing an image into predefined classes. Object detection entails identifying the objects of interest in an image, determining their positions and categories. Semantic segmentation involves classifying each pixel in an image and distinguishing different categories with different colors. Accurate semantic segmentation can determine the target contour information, which can not only reduce manual monitoring and judgment, but also greatly help to predict the behavior of the target. The precise semantic segmentation enables the extraction of target contour information, leading to a reduction in manual monitoring and judgment, as well as significantly aiding in the prediction of target behavior. The technique of semantic segmentation has been extensively utilized across numerous domains, including medical image processing, autonomous vehicle navigation, agricultural crop identification and boundary refinement, remote sensing image analysis, among others.

The maintenance of transportation infrastructure, including roads, bridges, and tunnels, is crucial for ensuring public safety. Relevant departments conduct regular inspections to identify potential defects or hazards [1,2]. However, the process of analyzing a large number of images captured during these inspections requires a significant amount of time and workforce [3,4]. With the advancement of artificial intelligence, semantic segmentation is utilized by researchers for the purpose of segmenting images of roads [5–7], bridges [8–10], and tunnel defects [11–13]. This not only enables the specific localization of the defect but also accurately delineates its contours, serving as the foundation for quantitative assessment of the defect. Currently, the classical semantic segmentation networks, including full convolutional network (FCN), SegNet, U-Net, PSPNet and DeepLab, are all based on convolutional neural network (CNN). Cha et al. [14] innovatively used the CNN network for detecting concrete cracks without calculating the defect features, and the proposed method demonstrated a high identification accuracy. Li et al. [15] proposed a fully convolutional network for detecting various types of concrete defects, including cracks, spalling, and holes, achieving excellent segmentation performance. Lee et al. [16] employed the SegNet network to segment tunnel crack images and predict the width of cracks.

With the continuous advancement of computer technology, the aforementioned semantic segmentation model has undergone improvements and optimizations from various perspectives. Chio and Cha [17] proposed the SDDNet to achieve real-time crack segmentation and effectively negate various complex backgrounds and crack-like features. Ju et al. [18] proposed an improved U-Net to achieve more precise segmentation of road crack images. Song et al. [19] introduced a lightweight PSPNet model for real-time detection of tunnel lining cracks, taking into consideration the limited computing speed of mobile terminal devices. To further enhance the precision of semantic segmentation, attention mechanism has been integrated into convolutional neural networks in relevant studies [20–23]. In order to address the issue of discontinuous segmentation of tiny cracks in concrete dams, Zhu et al. [24] proposed to improve the Deeplab V3+ algorithm by using an adaptive attention mechanism, and experimental results demonstrate that this mechanism enhances the accuracy of crack recognition. Zhou et al. [25] enhanced the DeeplabV3+ network by incorporating an attentional mechanism module for identifying tunnel leakage damage, achieving more precise edge segmentation and improved anti-interference capability.

Although the aforementioned enhanced and optimized semantic segmentation model is utilized for defects image segmentation, thereby improving the model’s recognition accuracy, most studies have primarily focused on concrete crack image segmentation with limited research on other specific defects. Furthermore, there has been a lack of comparative studies addressing the degree of improvement in recognition accuracy among different semantic segmentation models after the introduction of attention mechanism. The high complexity and multi-scale characteristics of concrete defects, due to their different sizes and shapes, necessitate a semantic segmentation model with higher performance. The issue with images containing cracks and exposed steel rebar lies in the fact that the proportion of pixels representing the cracks or exposed steel rebar is too small compared to the background. In these intricate contexts, it is necessary to further validate the influence of semantic segmentation model architecture, backbone network, and various parameters on model recognition accuracy.

In order to address the aforementioned issues, this study gathered images of concrete bridges showing spalling, crack, and exposed steel rebar defects and constructed multiple datasets for concrete bridge defects. Different backbone networks were selected for three semantic segmentation models—U-Net, DeepLabv3+, and PSPNet with attention mechanisms added to improve the original models. A combined loss function was employed to address the imbalance in images containing cracks and exposed steel rebar, as the proportion of pixels representing these features is significantly smaller compared to the background. The multi-class concrete defects dataset underwent transfer learning with pre-training weights. Based on these comparative analyses, the optimal semantic segmentation model for recognizing multi-class concrete damage will be obtained. The proposed semantic segmentation model is applied to the actual image detection of bridge defects.

This paper is organized as follows: Section 2 describes the detailed information of the proposed semantic segmentation model, Section 3 discusses the dataset, model parameters, and model performance evaluation metrics, Section 4 discusses the test results and conducts a comparative analysis, Section 5 describes the application of the proposed model in the actual image detection of bridge defects, and the Conclusion summarizes the studies and results.

In the process of information processing, humans tend to concentrate on specific pieces of information while disregarding other visible information, which is known as attention mechanisms. In computer vision, the attention mechanism allows the computer to prioritize critical information for the current task from a large pool of data. This mechanism enables the system to assign high weights to important information and low weights to irrelevant information, with the flexibility to adjust and select different crucial details in various situations. Currently, prominent attention mechanisms applied in computer vision include SE (Squeeze-and-Excitation) [26], CBAM (Convolutional Block Attention Module) [27], and CA module (Coordinate Attention) [28].

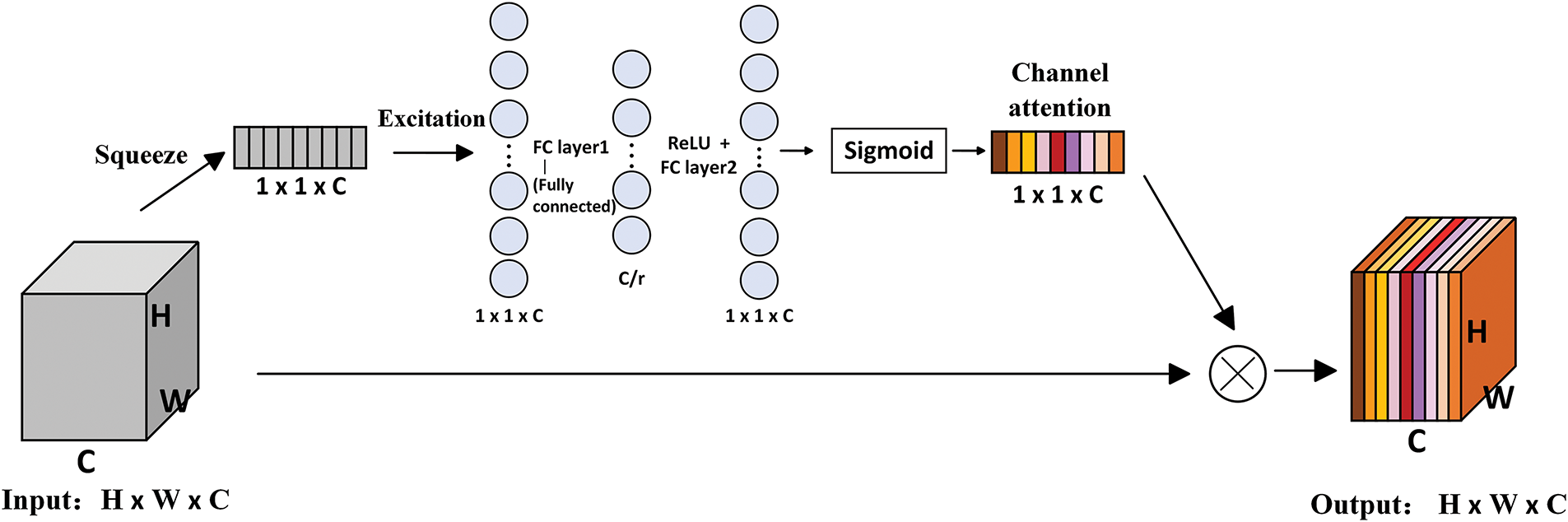

The architecture of the SE attention module is illustrated in Fig. 1. For a feature layer with dimensions W × H × C, it undergoes compression into a 1 × 1 × C feature vector through global average pooling. Subsequently, the Sigmoid function is utilized to calculate the probability distribution of this vector in order to obtain the channel weights. Finally, each channel’s weight value is multiplied by the corresponding two-dimensional matrix within the original feature map to yield a feature map with channel attention.

Figure 1: The structure diagram of the SE attention module

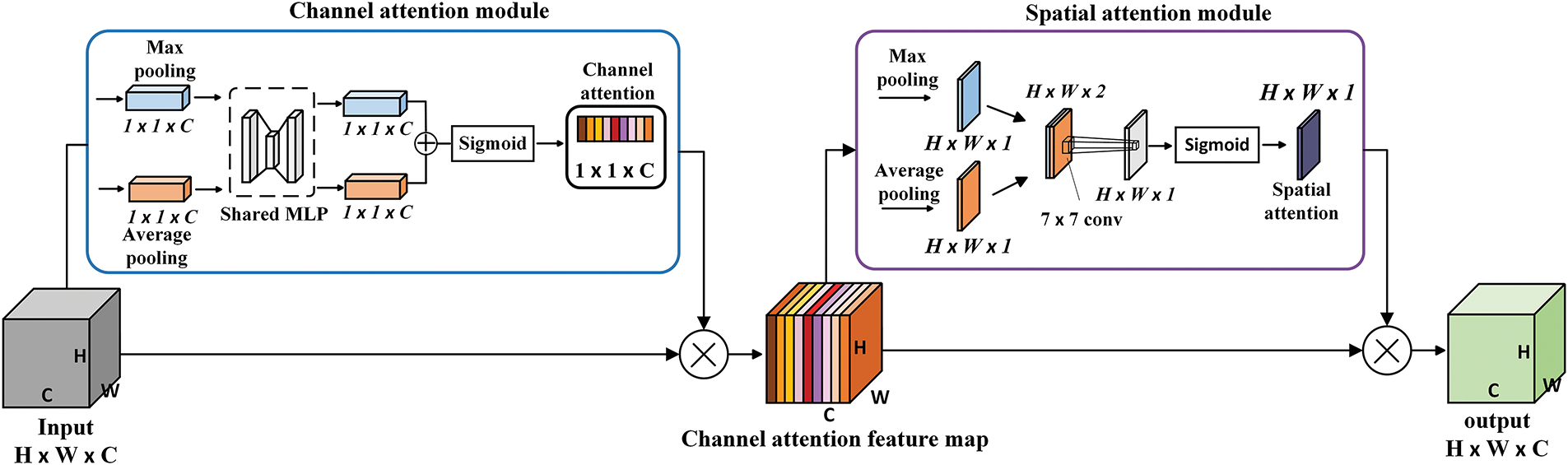

The structure of the CBAM attention module is illustrated in Fig. 2, comprising two submodules: channel attention and spatial attention. In the channel attention submodule, the input feature layer with size W × H × C undergoes max-pooling and average pooling to yield two 1 × 1 × C feature layers. By sharing the perceptron module, parameter count is reduced and computational efficiency is improved. The resulting channel weight value is then multiplied with the original feature map to generate the channel-attentive feature map. Moving on to the spatial attention submodule, the channel-attentive feature map (with size W × H × C) undergoes max-pooling and averaging along its channel dimension to produce two W × H × 1 feature layers. These are subsequently concatenated and subjected to a 7 × 7 convolution operation, yielding a final W × H × 1 feature layer. A Sigmoid function is applied to calculate the probability distribution for obtaining spatial weights from this layer. Finally, these spatial weights are multiplied with the channel-attentive feature map matrix to obtain a spatially attentive feature map.

Figure 2: The structure diagram of the CBAM attention module

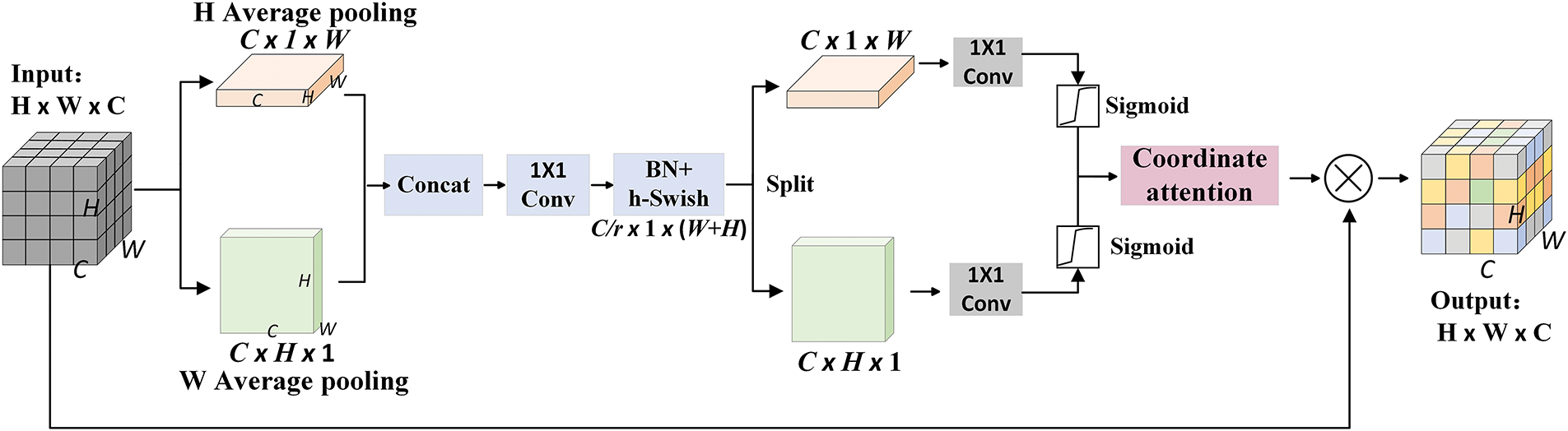

The architecture of the CA attention module is illustrated in Fig. 3. The CA module integrates positional information into channel information. For a feature layer of size W × H × C, average pooling is first applied along the horizontal (X) and vertical (Y) directions to generate two feature layers of sizes 1 × H × C and W × 1 × C. These are then concatenated and passed through a 1 × 1 convolution kernel to reduce the number of channels to the original C/r (where r is the reduction ratio). Subsequently, they are inputted to a batch normalization layer (BN) for improved model stability and convergence speed. Following this, an h-Swish activation function is applied, and the output feature layer after dimensionality reduction is split along its original spatial dimensions (height and width). The separated feature layers are transformed back to the same number of channels as the input feature layer using two separate 1 × 1 convolution kernels. The probability distributions of these two feature layers are calculated using a Sigmoid function to acquire attention weights in both horizontal and vertical directions. These weights are then multiplied by the original feature map matrix to obtain a coordinate attention-enhanced feature map.

Figure 3: The structure diagram of the CA attention module

During the neural network training process, the loss function is utilized to compute the discrepancy between the predicted and actual values [29]. Based on this calculated discrepancy, the model iteratively optimizes its training parameters to reduce the gap between predicted and true values.

The varying sizes of concrete defects and the significant imbalance between the number of pixels in positive samples (target) and negative samples (background) in defect images (crack and exposed steel rebar) may lead to biased predictions when using the commonly used cross-entropy loss function, resulting in model performance degradation. To address this issue of pixel imbalance in such images, this paper establishes three semantic segmentation models respectively with Focal loss, Dice loss, and a combination of Focal and Dice loss functions for comparative experiments.

The Focal loss function introduces weight coefficients α and γ to the cross entropy loss function in order to adjust the weights of complex and easy classified samples. This reduces the impact of easy classified samples on overall losses, allowing the model to focus more on complex classified samples. The Dice loss function addresses pixel ratio imbalances by disregarding a large number of background pixels when calculating the ratio of the intersection and union. When combined with Focal loss, Dice loss is guided to learn in the correct gradient descent manner. The formulas for Focal and Dice losses are as follows:

where: N represents the total number of pixel points, xi denotes the labeled value of the i-th pixel point, pi indicates the predicted value of the i-th pixel point, α and γ are adjustment coefficients with specific values (α = 0.25 and γ = 2), and ε is the smoothing coefficient designed to prevent division by zero, initially set to 0.001 in this article.

2.3 The Approach of Experimental Comparison

In this paper, a series of experiments were carried out to determine the most suitable network model for semantic segmentation of multi-class concrete defects images:

(1) In this paper, VGG16 and Resnet50 were used as the backbone network of U-Net, and Resnet50 was used as the backbone network of PSPNet and DeeplabV3+, respectively. Compare the semantic segmentation results of VGG16-U-Net, Resnet50-U-Net, PSPNet, and DeeplabV3+ for concrete defects. In order to investigate the loss function applicable to multiple types of defects, three different loss functions (Dice loss, Focal loss, and Dice loss + Focal loss combination) were set up for each of the above four models for the comparison experiments.

(2) The paper selected VGG16 and Resnet50 as the backbone networks for U-Net, and selected Resnet50 as the backbone network for PSPNet and DeeplabV3+, respectively. The semantic segmentation results of VGG16-U-Net, Resnet50-U-Net, PSPNet, and DeeplabV3+ are compared for concrete defects. To investigate the applicable loss function for multiple types of defects, three different loss functions (Dice loss, Focal loss, and Dice loss + Focal loss combination) were set up for each of the above four models in the comparison experiments.

(3) The computing power of mobile devices is limited for real-time detection of bridge defects. In order to reduce the number of convolutional kernels required for feature extraction and improve computing speed, this paper selects three lightweight networks, Segfomer, MobileNetV2-PSPNet, and MobileNetV2-DeeplabV3+, for semantic segmentation of concrete defects. The most suitable lightweight network for the semantic segmentation of concrete defect will be determined.

(4) In order to explore the optimization ability of attention mechanism on model performance, the model with a relatively good segmentation effect was selected from the above seven models, and the attention mechanism SE module, CBAM module and CA module were introduced. Through comparative analysis, the most suitable attention mechanism module for semantic segmentation of concrete multi-defect images will be identified.

3 Experimental Configuration and Evaluation Index

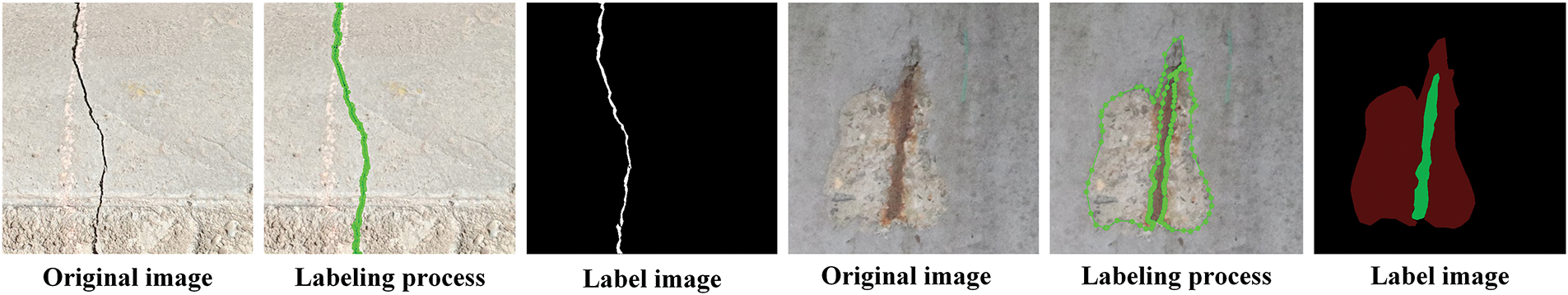

In this paper, a total of 850 concrete defects images (with 512 × 512 pixels) were captured from 17 concrete bridges in the field without the use of a fixed photography light source, resulting in dataset images that closely represent real-world engineering conditions. The Labelme software was utilized to annotate the concrete defect images. During the annotation process, the polygon labeling tool was used to outline and label the concrete defect image at maximum magnification, generating a JSON file containing information on exposed steel rebar, crack, spalling contour positions, and label names. Different colors were assigned to labeled areas for each type of defect category. The original concrete image and the image annotation process are illustrated in Fig. 4.

Figure 4: Example diagram for labeling concrete defects

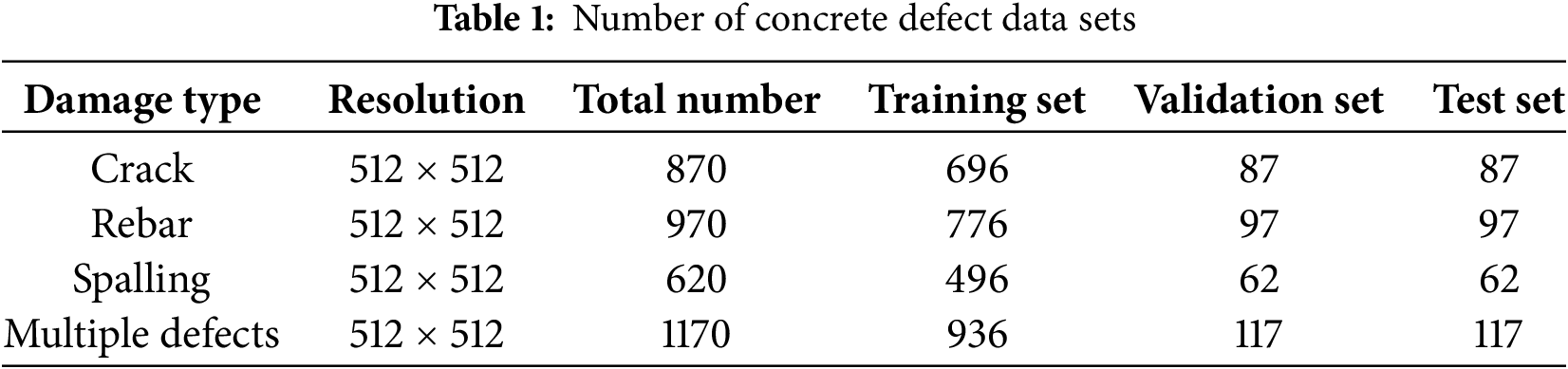

The quantity and quality of the dataset have a significant impact on the robustness and generalization ability of the trained model. Therefore, a data enhancement method was employed to expand the dataset without altering the essence of the image categories. This involved techniques such as panning, flipping, adjusting brightness, and randomly superimposing noise on the original concrete defect images. As a result, 3630 concrete defect images (with 512 × 512 pixels) were obtained. Within the expanded dataset, 80% of the images were randomly allocated to the training set, 10% were designated as the validation set, and the remaining 10% constituted the test set, as detailed in Table 1.

3.2 Experimental Setting and Configuration

The semantic segmentation model in this paper is implemented using Python3.8 as the programming language, utilizing Pytorch1.13 as the deep learning framework, CUDA version 11.7, and the computer is equipped with 32 GB of RAM and an NVIDIA GTX 4070 GPU.

The training period (epoch) of the model is set to 100, the Adam algorithm is used as the optimizer, the momentum is set to 0.9, and the cos function is used as the learning rate reduction method. In order to avoid the randomness of experimental results, the order of data loading is fixed by setting random seeds, so that the same results can be obtained each time of independent training.

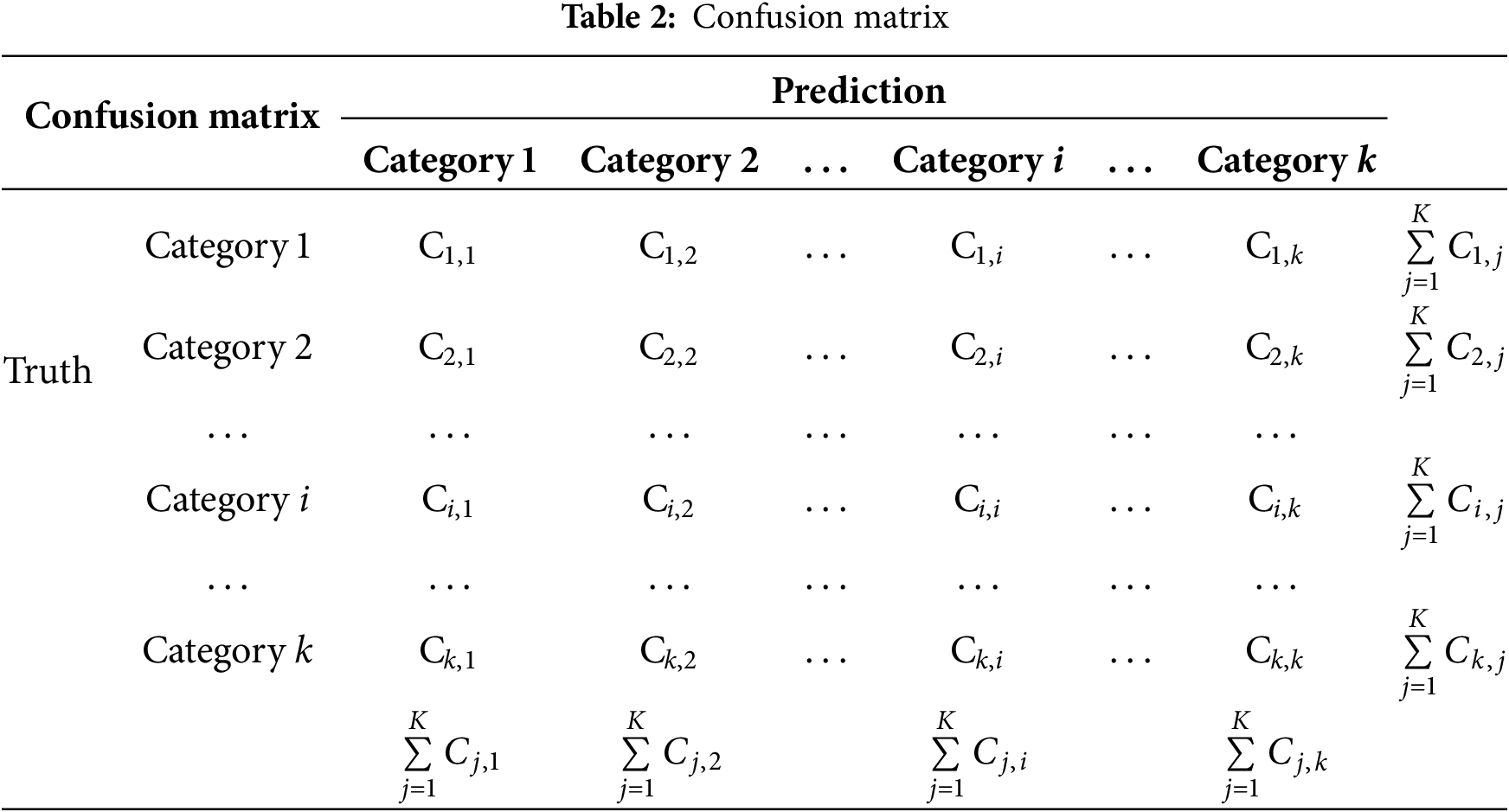

The commonly used evaluation metrics for semantic segmentation models include Class Pixel Accuracy (CPA), Mean Pixel Accuracy (MPA), Intersection over Union (IoU), and Mean Intersection over Union (MIoU). The definition of these indices is associated with the confusion matrix, as illustrated in Table 1. The values in the columns of the confusion matrix represent the predicted number of pixels for category i, while those in the rows represent the actual number of pixels for category i. The diagonal line Ci represents the accurately predicted number of pixels for category i.

CPA is the ratio of the number of pixels correctly predicted as category i to the total number of pixels predicted as category i (the sum of category i columns in Table 2). The following equation is used for the calculation:

MPA is the average of the sum of the CPA values across K categories. The following equation is used for the calculation:

The meaning of IoU is that the ratio of the intersection and union between the prediction and reality of a certain category. For category i, the intersection of prediction and reality is the number of pixels correctly predicted belonging to category i, the union of prediction and reality is the sum of the number of pixels predicted belonging to category i (summation of class i columns in Table 1) and the number of pixels really belonging to class i (summation of class i rows in Table 2) minus the number of pixels correctly predicted belonging to class i. The following equation is used for the calculation:

MIoU is the average of the sum of the IoU values across K categories. The following equation is used for the calculation:

Model parameters [30], floating-point Operations (FLOPs), and Frames Per Second (FPS) are selected to evaluate the real-time performance of the model, where FPS is calculated as follows:

where: T is the time required for detection, and M is the number of images detected.

4 Experimental Results and Comparative Analysis

4.1 The Semantic Segmentation Results of U-Net, PSPNet, and DeeplabV3+

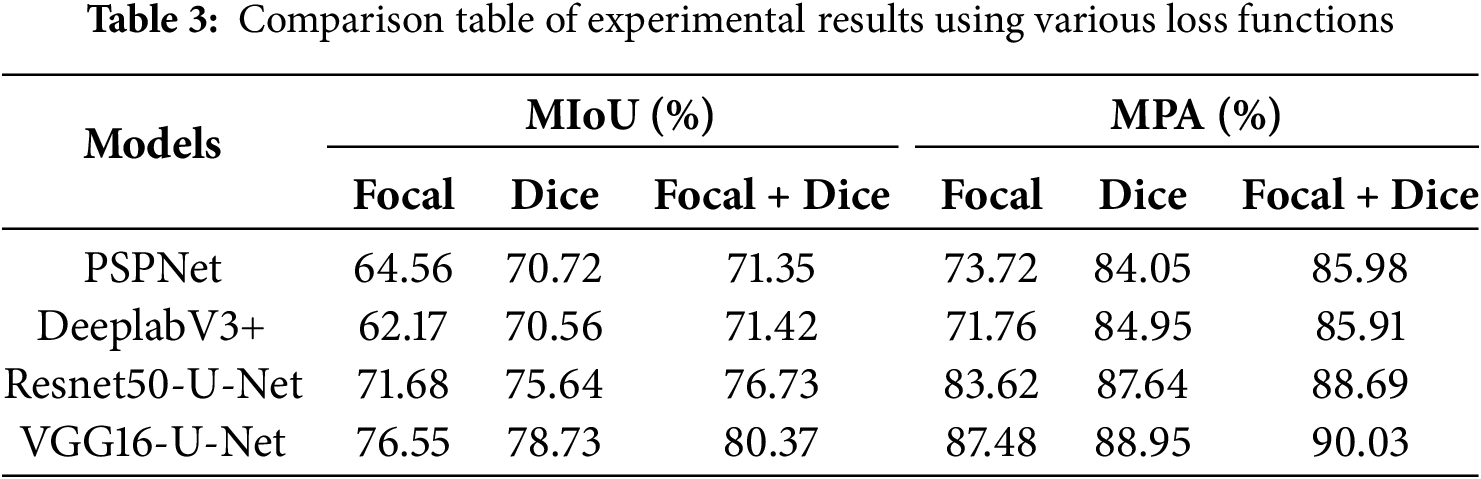

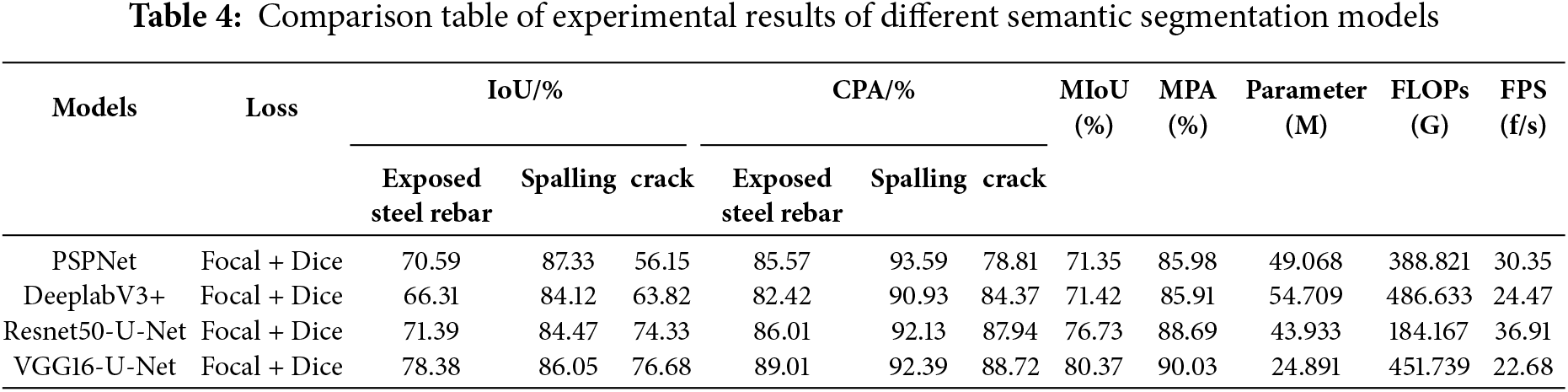

Using the same dataset, three different loss functions (Dice loss, Focal loss, and Dice loss + Focal loss combination) are applied to each of the four models: VGG16-U-Net, Resnet50-U-Net, PSPNet, and DeeplabV3+. The semantic segmentation results for concrete defects images from the four models are presented in Tables 3 and 4 under consistent experimental conditions and configurations. The evaluation metrics in the tables represent experimental results obtained after incorporating pre-weights.

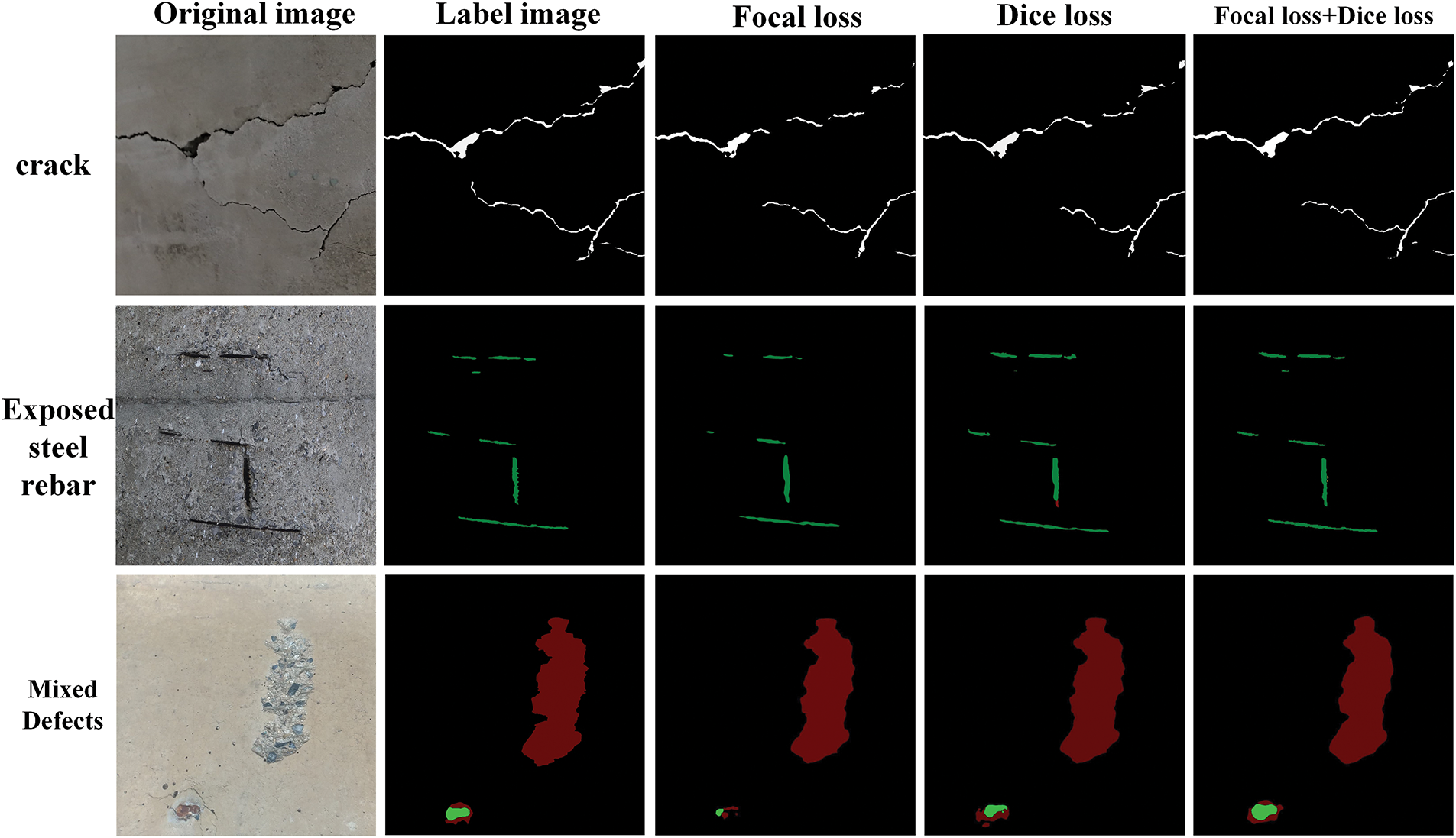

Table 3 demonstrates that the utilization of the Focal loss function results in the lowest accuracy for defects image recognition across all four models. This can be attributed to the fact that the Focal loss function relies on the weight parameter derived from the cross-entropy loss function, which only partially addresses the imbalance in pixel occupancy ratio. In contrast, the Dice loss function effectively mitigates this imbalance by disregarding background pixels, leading to a significant improvement in recognition accuracy for defects images across all four models. Combining the Dice loss function with Focal loss function can effectively guide the model to learn in the correct gradient direction. The combination of Dice and Focal loss functions yields the highest recognition accuracy for defect images among these models.

Fig. 5 illustrates the segmentation maps of the concrete defects using three different loss functions for the VGG16-U-Net. In the crack segmentation map, the combined Dice + Focal function accurately delineated complex crack edges compared to using a single loss function, with minimal error when compared to the labeled images. In the exposed steel rebar and spalling segmentation map, the use of combined loss function resulted in finer rebar and spalling segmentation, thereby improving accuracy in identifying small-size concrete defects. This demonstrates that employing a combined loss function in multi-defect scenarios effectively addresses the issue of imbalance between target and background pixel ratios, guiding the model to focus more on target areas and ultimately enhancing defect segmentation accuracy.

Figure 5: Semantic segmentation diagram of VGG16-U-Net under different loss functions

According to Table 4, VGG16-U-Net demonstrates the highest accuracy, achieving an MIoU of 80.37%, outperforming PSPNet, DeepLabv3+, Resnet50-U-Net by 9.02%, 8.95%, and 3.64%, respectively; and its MPA is 90.03%, surpassing PSPNet and DeepLabv3+, Resnet50-U-Net by 4.05%, 4.12%, and 1.34%.

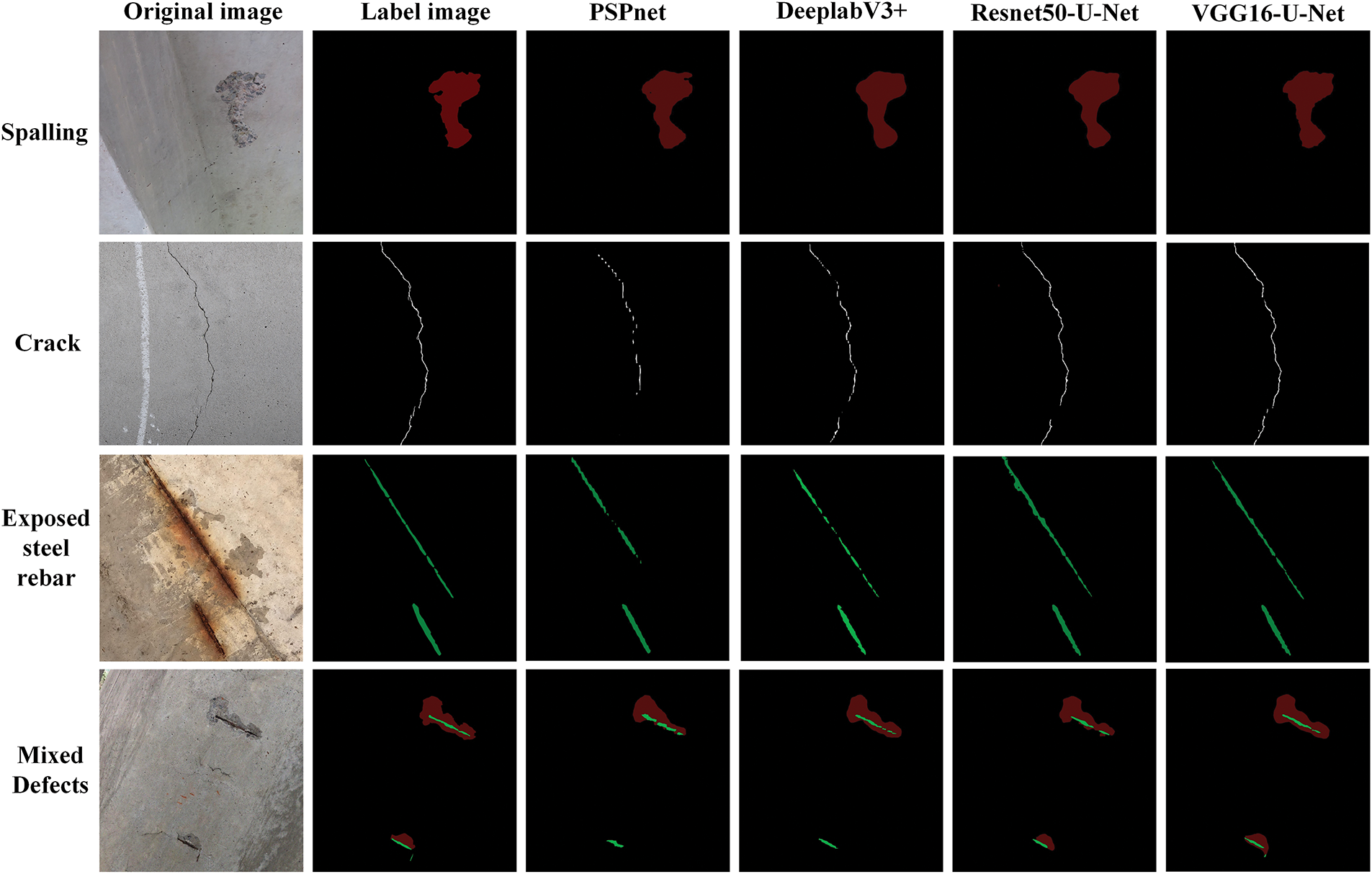

By comparing the semantic segmentation images output from each model, the accuracy of concrete defect segmentation can be visually assessed. Fig. 6 presents a comparison of segmentation results obtained from VGG16-U-Net, Resnet50-U-Net, PSPNet, and DeeplabV3+. It is evident that all four models show higher accuracy in detecting spalling defects with minimal error compared to the labeled image. In terms of tiny cracks, VGG16-U-Net produces the closest result to the labeled image, while PSPNet shows more areas of missed detection, indicating its inferior feature extraction capability for cracks. As for exposed concrete reinforcement, both PSPNet and DeeplabV3+ demonstrate some missed detections, whereas VGG16-U-Net achieves the most accurate segmentation.

Figure 6: Comparison of semantic segmentation results of four models

In the detection of mixed defects, DeepLabv3+ and PSPNet exhibited some omissions in identifying concrete spalling, while Resnet50-U-Net failed to accurately segment some exposed steel rebar. VGG16-U-Net demonstrated no apparent missing or false detections and was able to identify small steel rebar, indicating its superior suitability for semantic segmentation of multi-class concrete defects.

The table presents the parameter count, floating-point operations (GFLOPs), and detection speed (FPS) for the aforementioned four models. The number of parameters and floating-point operations for all models is substantial. Notably, DeepLabv3+ exhibits the relatively highest floating-point operation at 486.633 G with an image detection speed of 24.47 f/s, while Resnet50-U-Net has the relatively lowest floating-point operation at 184.167 G with an image detection speed of 36.91 f/s. When running computations on mobile devices, the processing speed will be further reduced.

4.2 Comparison of Results from Lightweight Network Semantic Segmentation

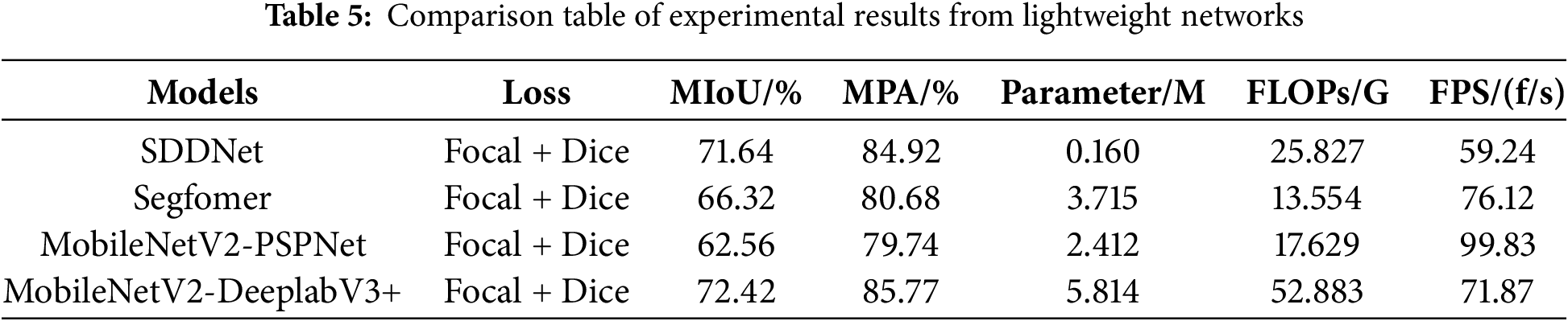

The limited computing power of mobile devices resulted in a decrease in real-time bridge defects detection speed, owing to the high number of parameters in the model mentioned above. In order to improve computing speed by reducing the required number of convolutional kernels for feature extraction, four lightweight networks (SDDNet, Segfomer, MobileNetV2-PSPNet, and MobileNetV2-DeeplabV3+) were selected for comparative experiments under identical experimental conditions and dataset. The detailed comparison findings can be found in Table 5.

Comparing Tables 4 and 5, MobileNetV2-PSPNet has only 7.8% of the parameters of PSPNet, while MobileNetV2-DeeplabV3+ has just 4.9% of the parameters of DeeplabV3+, resulting in a significant reduction in the number of parameters of the models. The four lightweight segmentation models achieve image inference speeds of 59.24%, 76.12, 99.83, and 71.87 frames/s, with MobileNetV2-PSPNet being 3.3 times faster than PSPNet and MobileNetV2-DeeplabV3+ being 2.9 times faster than DeeplabV3+. This demonstrates that the lightweight backbone network significantly improves concrete defects image detection speed. Among them, MobileNetV2-PSPNet exhibits the fastest inference speed but sacrifices some detection accuracy with a MIoU of 62.56% and MPA of 79.74%, whereas MobileNetV2-DeeplabV3+ delivers the best overall performance with a MIoU of 72.42% and MPA of 85.77%.

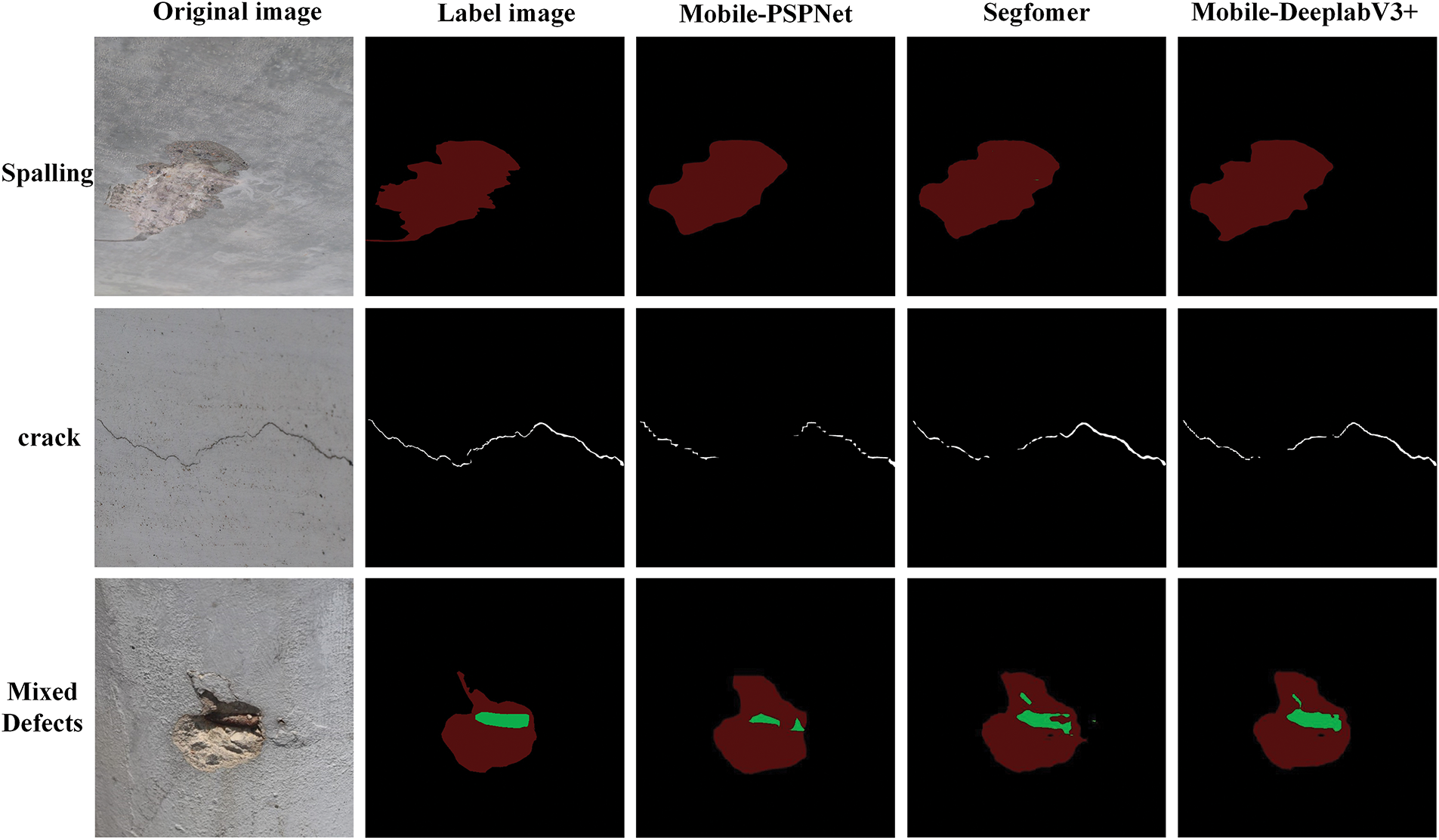

The results presented in Fig. 7 demonstrate the segmentation and comparison outcomes of the three lightweight models (Segfomer, MobileNetV2-PSPNet, and MobileNetV2-DeeplabV3+). It is evident from Fig. 7 that the three lightweight networks exhibit more precise segmentation of spalling defects, with MobileNetV2-DeeplabV3+ displaying contours closest to the label images. For crack defects, the three lightweight networks exhibit varying degrees of detection missing. In terms of mixed defects, the MobileNetV2-DeeplabV3+ model demonstrates a more comprehensive segmentation of exposed steel rebar defect images. These findings indicate that, compared to the other two models, MobileNetV2-DeeplabV3+ is better suited for the real-time detection of multi-class concrete defects. Although slightly lower in MPA compared to VGG16-U-Net, Resnet50-U-Net, PSPNet, and DeeplabV3+, these three lightweight networks significantly reduce parameter count and improve detection speed.

Figure 7: Comparison diagram of semantic segmentation in lightweight networks

4.3 Improved Recognition Results through the Integration of Attention Mechanism Modules

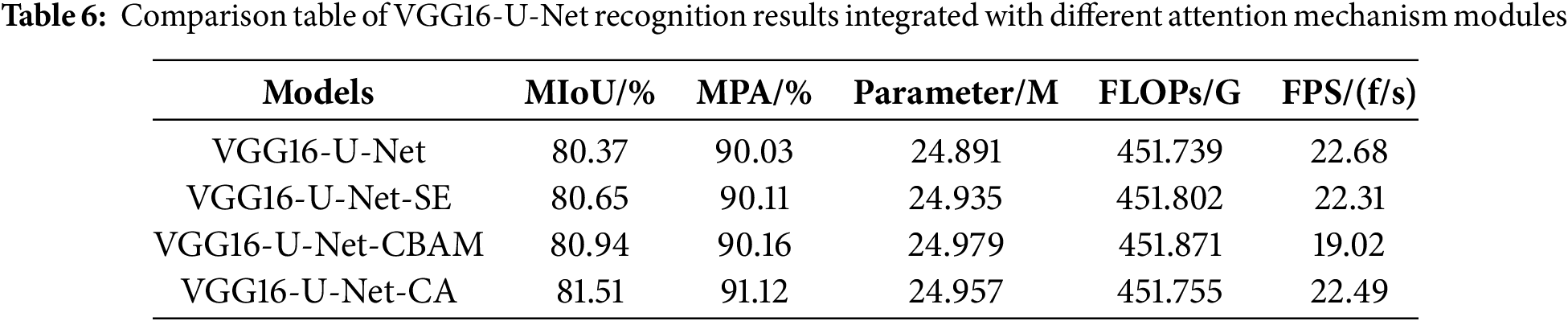

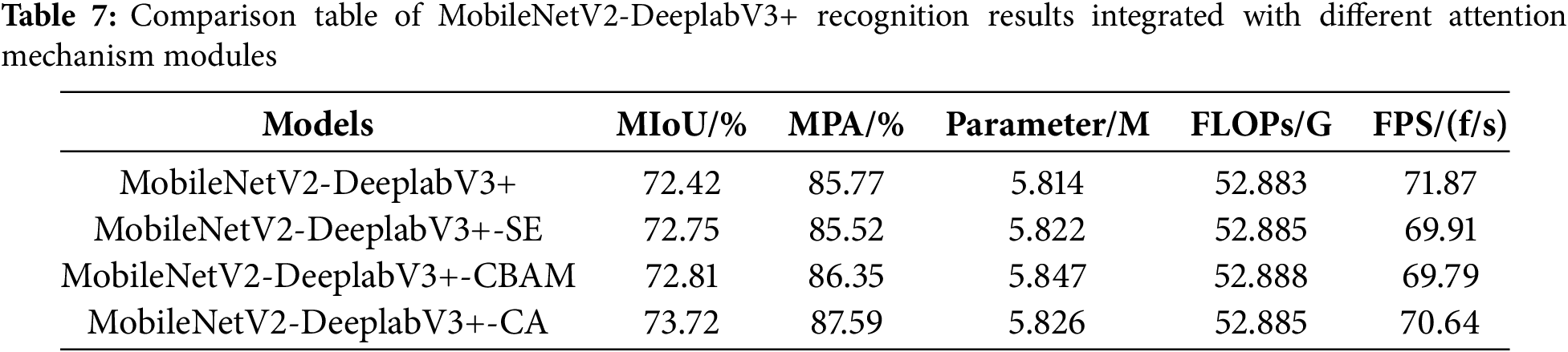

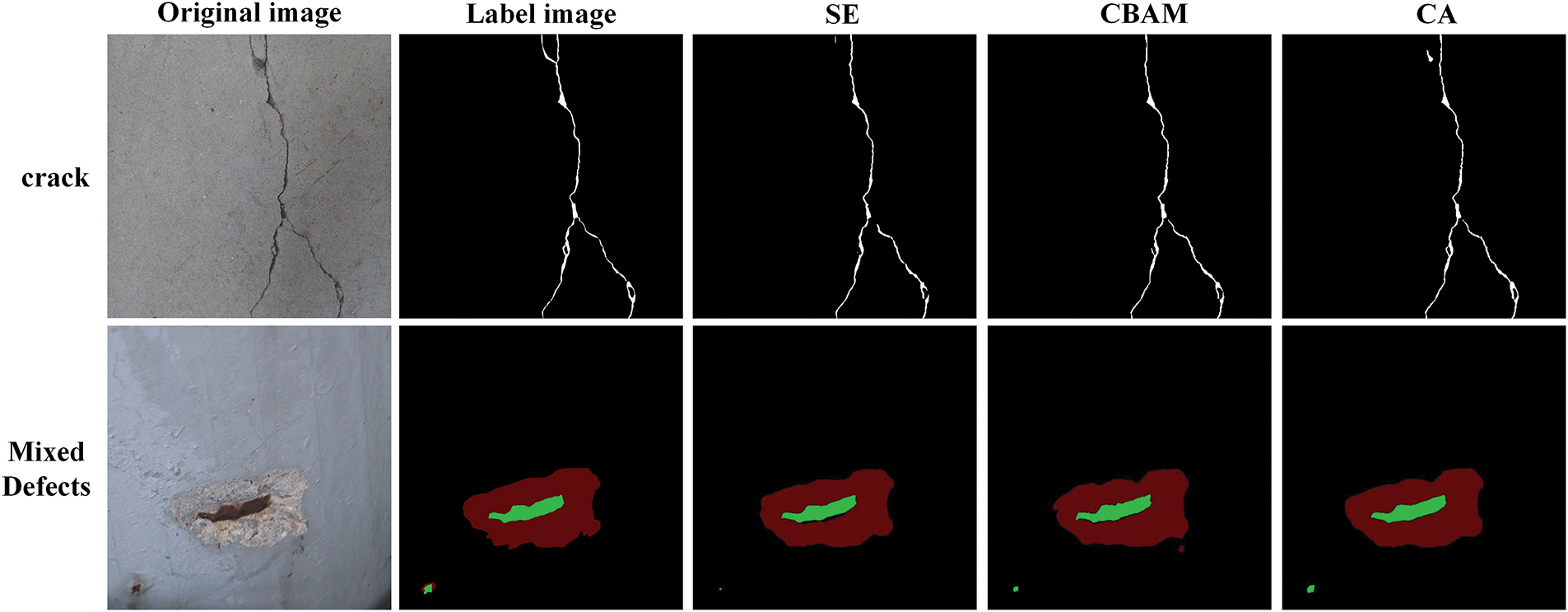

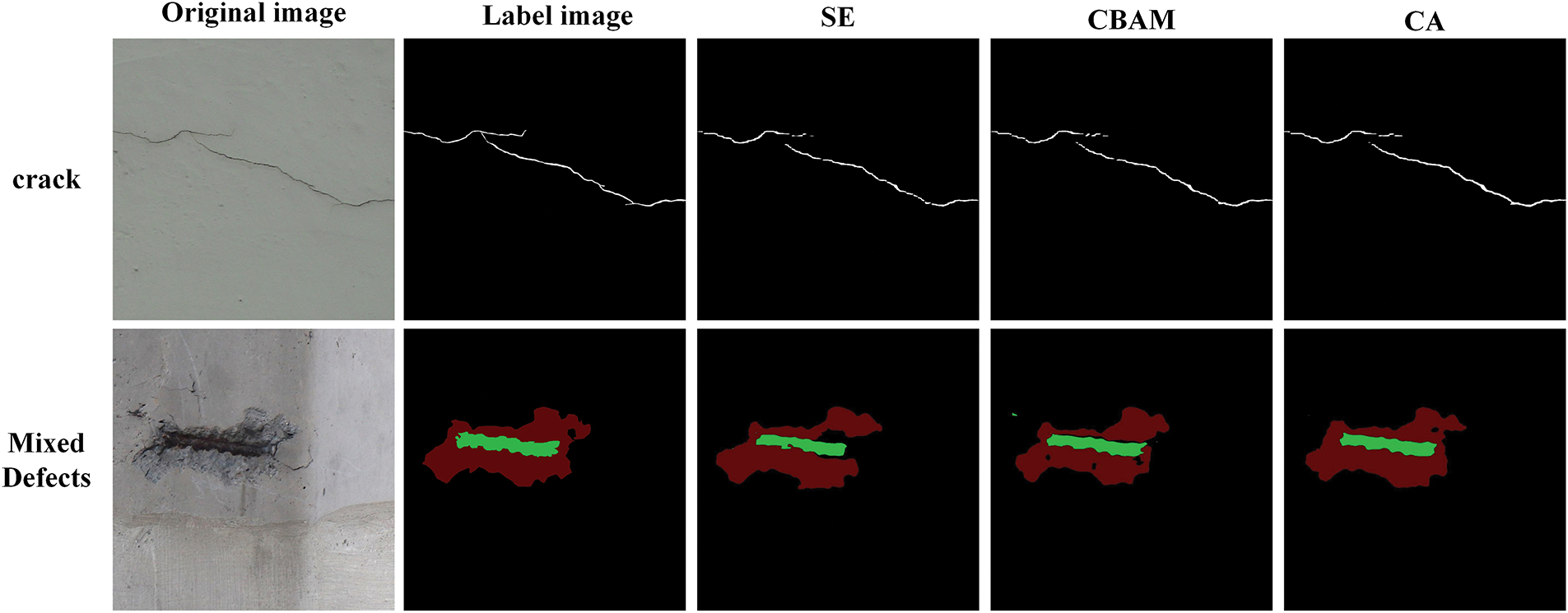

To investigate the optimization capability of attention mechanisms on model performance, VGG16-U-Net, known for its superior segmentation effect, and MobileNetV2-DeeplabV3+, recognized for its outstanding real-time segmentation performance, were selected from the aforementioned seven models. Three different attention mechanism modules (SE, CBAM, and CA) were introduced for comparative analysis, and the test results are presented in Tables 6 and 7.

After the incorporation of three distinct attention mechanisms into VGG16-U-Net, Table 5 demonstrates an enhancement in the network’s recognition accuracy. Among these mechanisms, the introduction of the CA module yields the highest recognition accuracy, resulting in a 1.14% improvement in MIoU and a 1.09% improvement in MPA compared to when no attention module is introduced. The CA module not only captures inter-channel information but also considers direction-related positional information, enabling the network model to conduct feature extraction over a larger area, thereby aiding in better target localization and identification. Despite a slight increase in computational parameters and floating-point operations, as well as a minor reduction in detection speed, with the introduction of attention mechanism modules compared to without them.

Incorporating the CA attention module into the VGG16-U-Net model leads to a more comprehensive recognition of crack details compared to the SE and CBAM attention modules, as demonstrated by the segmentation results in Fig. 8 for crack defects. In addition, in the segmentation results for mixed defects, the CA attention module effectively guides the model to recognize more exposed steel rebar defects while reducing the misdetection of spalling defects. These findings indicate that incorporating the CA attention module into VGG16-U-Net yields optimal improvements in model performance.

Figure 8: Semantic segmentation comparison diagram of VGG16-U-Net recognition results integrated with different attention mechanism modules

Table 7 demonstrates that the introduction of three different attention mechanisms in MobileNetV2-DeeplabV3+ leads to an improvement in network recognition accuracy. The highest recognition accuracy is achieved when the CA module is introduced, resulting in a 1.29% increase in MIoU and a 1.82% increase in MPA compared to the absence of an attention module.

After introducing the CA attention module, the MobileNetV2-DeeplabV3+ model demonstrates the least segmentation error for crack defects compared to SE and CBAM attention modules in Fig. 9. In mixed defects detection, it also shows the most complete recognition of spalling defect, indicating its improved ability to extract features of multiple types of defects and enhance recognition accuracy for subtle defects.

Figure 9: Semantic segmentation comparison diagram of MobileNetV2-DeeplabV3+ recognition results integrated with different attention mechanism modules

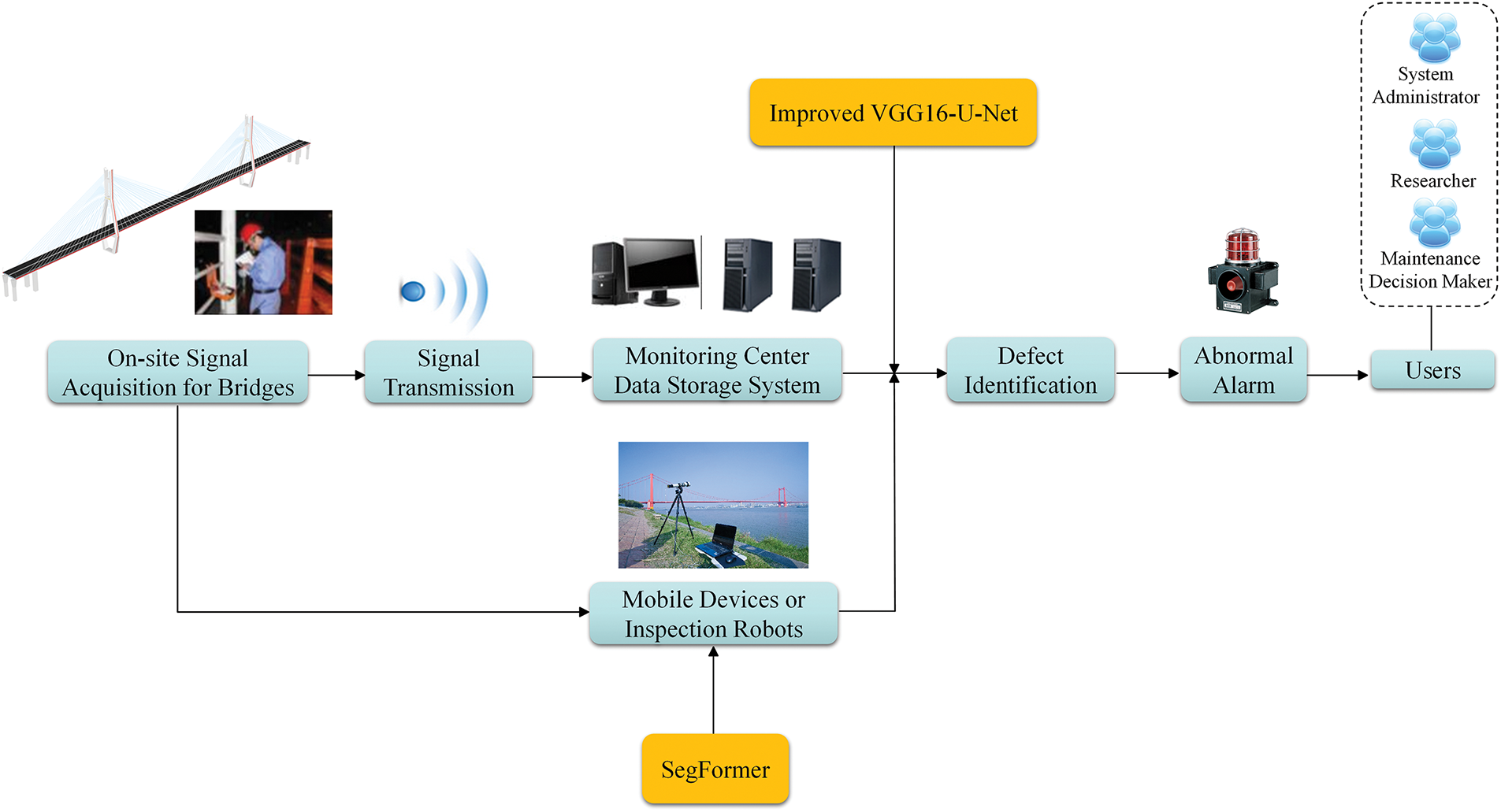

To verify whether the proposed semantic segmentation model can effectively detect defects in bridge health monitoring, a set of defect images captured by the bridge health monitoring system was selected, and semantic segmentation results were generated using the proposed model. The workflow of the concrete bridge health monitoring system is presented in Fig. 10.

Figure 10: Flowchart of the concrete bridge health monitoring system

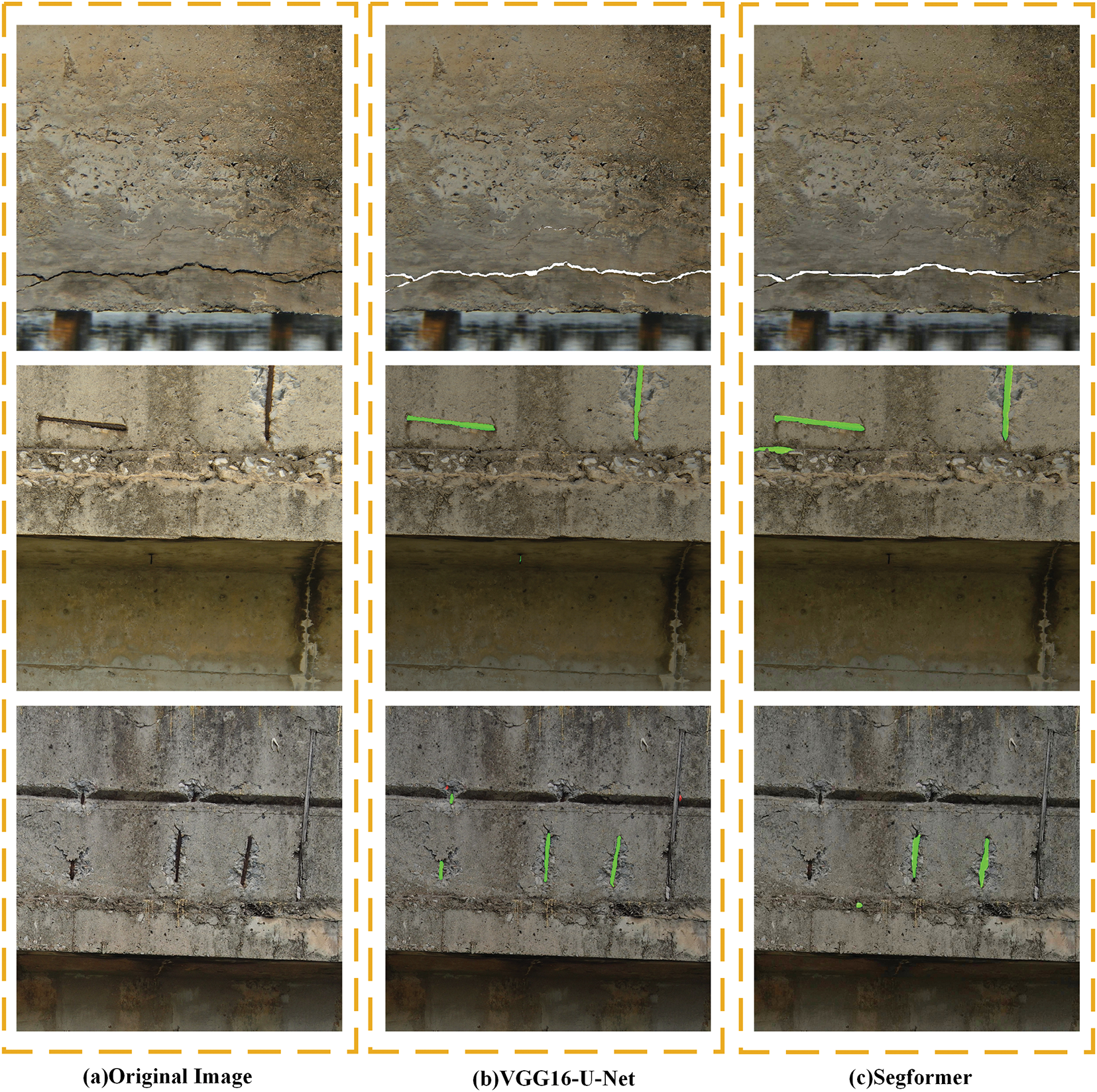

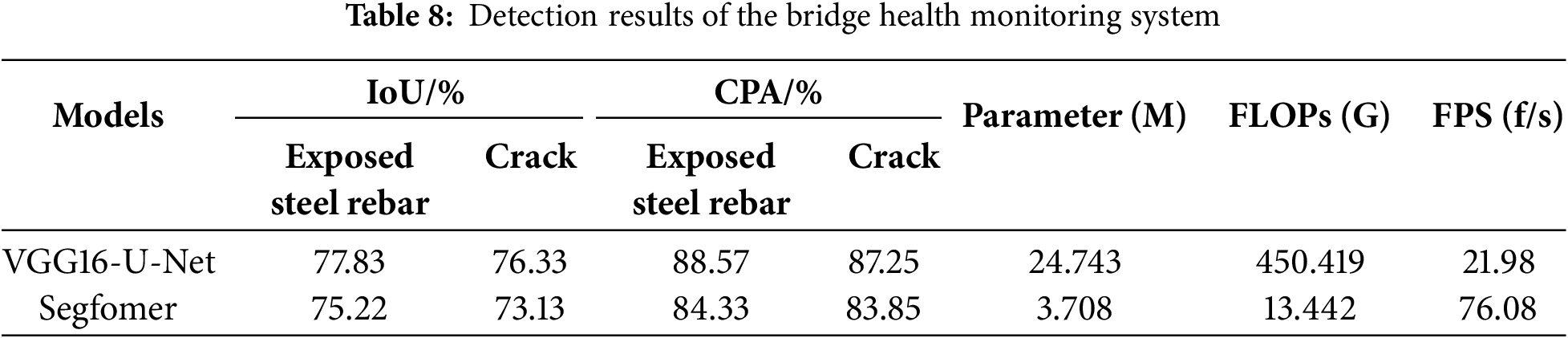

Fig. 11 illustrates the semantic segmentation visualization of defect images extracted from the bridge health monitoring system. Specifically, Fig. 11a displays the original image, whereas Fig. 11b,c presents the visualization results of defect identification achieved by VGG16-U-Net and Segformer. The results demonstrate that both models yield segmentation outcomes closely aligned with actual defects, exhibiting minimal false positives and missed detections. This confirms the high accuracy of the proposed VGG16-U-Net model and the lightweight SegFormer model in identifying various types of concrete defects captured by the bridge health monitoring system. As indicated in Table 8, the VGG16-U-Net model achieves slightly higher segmentation accuracy compared to SegFormer. However, SegFormer significantly reduces the number of parameters and achieves a faster detection speed, making it more suitable for real-time defect detection in field applications. In the segmentation task, for small targets such as small cracks, the SegFormer model can keep the segmentation boundary details intact. For large targets such as exposed ribs and large area spalling, the model can realize the integrity of the segmentation boundary and maintain the stability of classification judgment. The results indicate that the VGG16-U-Net model and the SegFormer model can meet the requirements of intelligent defect image recognition for concrete structural health monitoring.

Figure 11: Defect image semantic segmentation visualization: (a) Original Image, (b) VGG16-U-Net, (c) Segformer

In this paper, the multiple semantic segmentation models were developed for the purpose of segmenting concrete multi-class defect images. The comprehensive comparative studies were conducted from various perspectives, including the selection of different backbone networks, the implementation of diverse loss functions, and the incorporation of an attention mechanism module. The primary conclusions are as follows:

(1) Among the semantic segmentation results of VGG16-U-Net, Resnet50-U-Net, PSPNet, and DeeplabV3+ for concrete defects, VGG16-U-Net demonstrates the highest recognition accuracy with an MIoU of 80.37% and an MPA of 90.03% in the test set. Upon comparing the semantic segmentation images output from each model, it is evident that VGG16-U-Net’s segmentation maps for spalling, fine cracks, and exposed steel rebar are notably more accurate with minimal error when compared to labeled images. This indicates that the combination of the VGG16 backbone and U-Net’s decoder excels at capturing feature information at different scales and retaining detailed features, making it better suited for multi-category concrete defect images semantic segmentation than the other three models.

(2) Compared to using Focal and Dice loss functions alone, the above four network models demonstrate the highest segmentation accuracy for defect images when utilizing the combined Focal and Dice loss functions. They can more accurately segment the edges of complex cracks, as well as exposed steel rebars and spallings. This indicates that employing a combined loss function in multi-defect scenarios effectively addresses the issue of imbalance between target and background pixel occupancy ratios, guides the model to focus more on the target region, and significantly improves segmentation accuracy for defect images.

(3) Among the semantic segmentation results of three lightweight networks (Segformer, MobileNetV2-PSPNet, and MobileNetV2-DeeplabV3+) on concrete defects, MobileNetV2-DeeplabV3+ demonstrates superior overall performance with an MIoU of 72.42% and MPA of 85.77%. Although its MIoU and MPA are lower compared to VGG16-U-Net, the significant reduction in model parameters (23.3% of VGG16-U-Net) allows for a faster image detection speed of 71.87 frames/s (3.16 times of VGG16-U-Net) meeting the requirements for real-time detection of concrete defects.

(4) With the incorporation of SE, CBAM, and CA attention modules into VGG16-U-Net and MobileNetV2-DeeplabV3+, the recognition accuracy of the networks has been enhanced. Among these, the integration of the CA module has resulted in the highest recognition accuracy for the networks. This suggests that incorporating the CA attention module can effectively guide the model in extracting features related to various types of defects, thereby improving the model’s ability to recognize subtle defects. It provides experimental support for the structural health monitoring (SHM) of critical infrastructure such as bridges and highways.

Acknowledgement: The authors sincerely thank the College of Civil Engineering, Architecture and Environment of Hubei University of Technology for its support and help. The authors sincerely thank the National Natural Science Foundation of China for its funding.

Funding Statement: The work described in this paper was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (51708188).

Author Contributions: Conceptualization and design, writing—review & editing, supervision: Caiping Huang; experimental execution, data analysis, writing—original draft: Hui Li; resources, data collection, writing—review: Zihang Yu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Wang HP, Wu YB, Zhang C, Xiang P. Monitoring data motivated health condition assessment of cement concrete pavements in field based on FBG sensing technology. Struct Health Monit. 2024;7(5):14759217241268821. doi:10.1177/14759217241268821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Huang C, Zhai KK, Xie X, Tan J. Deep residual network training for reinforced concrete defects intelligent classifier. Eur J Environ Civ Eng. 2022;26(15):7540–52. doi:10.1080/19648189.2021.2003250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Ji A, Xue X, Wang Y, Luo X, Xue W. An integrated approach to automatic pixel-level crack detection and quantification of asphalt pavement. Autom Constr. 2020;114(2):103176. doi:10.1016/j.autcon.2020.103176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Ren Y, Huang J, Hong Z, Lu W, Yin J, Zou L, et al. Image-based concrete crack detection in tunnels using deep fully convolutional networks. Constr Build Mater. 2020;234:117367. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.117367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Liu J, Yang X, Lau S, Wang X, Luo S, Lee VC, et al. Automated pavement crack detection and segmentation based on two-step convolutional neural network. Comput Aided Civ Infrastruct Eng. 2020;35(11):1291–305. doi:10.1111/mice.12622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Zhong J, Zhu J, Ju H, Ma T, Zhang W. Multi-scale feature fusion network for pixel-level pavement distress detection. Autom Constr. 2022;141(3):104436. doi:10.1016/j.autcon.2022.104436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Du Y, Zhong S, Fang H, Wang N, Liu C, Wu D, et al. Modeling automatic pavement crack object detection and pixel-level segmentation. Autom Constr. 2023;150(6):104840. doi:10.1016/j.autcon.2023.104840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Teng S, Chen X, Chen G, Cheng L. Structural damage detection based on transfer learning strategy using digital twins of bridges. Mech Syst Signal Process. 2023;191:110160. doi:10.1016/j.ymssp.2023.110160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Xu Y, Fan Y, Li H. Lightweight semantic segmentation of complex structural damage recognition for actual bridges. Struct Health Monit. 2023;22(5):3250–69. doi:10.1177/14759217221147015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Zhang J, Qian S, Tan C. Automated bridge surface crack detection and segmentation using computer vision-based deep learning model. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2022;115:105225. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2022.105225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Zhou Z, Zhang J, Gong C. Hybrid semantic segmentation for tunnel lining cracks based on swin transformer and convolutional neural network. Comput Aided Civ Infrastruct Eng. 2023;38(17):2491–510. doi:10.1111/mice.13003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Huang HW, Li QT, Zhang DM. Deep learning based image recognition for crack and leakage defects of metro shield tunnel. Tunn Undergr Space Technol. 2018;77(9):166–76. doi:10.1016/j.tust.2018.04.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Xu H, Wang M, Liu C, Li F, Xie C. Automatic detection of tunnel lining crack based on mobile image acquisition system and deep learning ensemble model. Tunn Undergr Space Technol. 2024;154(3):106124. doi:10.1016/j.tust.2024.106124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Cha YJ, Choi W, Büyüköztürk O. Deep learning-based crack damage detection using convolutional neural networks. Computer Aided Civil Eng. 2017;32(5):361–78. doi:10.1111/mice.12263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Li S, Zhao X, Zhou G. Automatic pixel-level multiple damage detection of concrete structure using fully convolutional network. Comput Aided Civ Infrastruct Eng. 2019;34(7):616–34. doi:10.1111/mice.12433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Lee JS, Hwang SH, Choi IY, Choi Y. Estimation of crack width based on shape-sensitive kernels and semantic segmentation. Struct Control Health Monit. 2020;27(4):2504. doi:10.1002/stc.2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Choi W, Cha YJ. SDDNet: real-time crack segmentation. IEEE Trans Ind Electron. 2020;67(9):8016–25. doi:10.1109/tie.2019.2945265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Ju H, Li W, Tighe S, Xu Z, Zhai J. CrackU-Net: a novel deep convolutional neural network for pixelwise pavement crack detection. Struct Control Health Monit. 2020;27(8):e2551. doi:10.1002/stc.2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Song Y, Zhao NY, Yan C, Tan HH, Deng J. The Mobile-PSPNet method for real-time segmentation of tunnel lining cracks. J Railw Sci Eng. 2022;19(12):3746–57. (In Chinese). doi:10.19713/j.cnki.43-1423/u.t20220024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Chu H, Wang W, Deng L. Tiny-crack-net: a multiscale feature fusion network with attention mechanisms for segmentation of tiny cracks. Comput Aided Civ Infrastruct Eng. 2022;37(14):1914–31. doi:10.1111/mice.12881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Liu Y, Bai X, Wang J, Li G, Li J, Lv Z. Image semantic segmentation approach based on DeepLabV3 plus network with an attention mechanism. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2024;127(12):107260. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2023.107260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Deng W, Mou Y, Kashiwa T, Escalera S, Nagai K, Nakayama K, et al. Vision based pixel-level bridge structural damage detection using a link ASPP network. Autom Constr. 2020;110(6):102973. doi:10.1016/j.autcon.2019.102973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Karaaslan E, Bagci U, Catbas FN. Attention-guided analysis of infrastructure damage with semi-supervised deep learning. Autom Constr. 2021;125:103634. doi:10.1016/j.autcon.2021.103634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Zhu Y, Tang H. Automatic damage detection and diagnosis for hydraulic structures using drones and artificial intelligence techniques. Remote Sens. 2023;15(3):615. doi:10.3390/rs15030615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Zhou Z, Zhang JJ, Gong CJ, Ding HH. Automatic identification of tunnel leakage based on deep semantic segmentation. Chin J Rock Mech Eng. 2022;41(10):2082–93. (In Chinese). doi:10.13722/j.cnki.jrme.2022.0016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Hu J, Shen L, Sun G. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. In: 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2018 Jun 18–23; Salt Lake City, UT, USA. p. 7132–41. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2018.00745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Woo S, Park J, Lee JY, Kweon IS. CBAM: convolutional block attention module. In: Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV); 2018 Sep 8; Munich, Germany. p. 3–19. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-01234-2_1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Hou Q, Zhou D, Feng J. Coordinate attention for efficient mobile network design. In: 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2021 Jun 20–25; Nashville, TN, USA. p. 13708–17. doi:10.1109/cvpr46437.2021.01350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Huang CP, Tian WY, Li Q. Research on quantitative identification methods for concrete bridge defects based on U-Net and mathematical morphology. Bridge Constr. 2025;55(1):64–71. (In Chinese). doi:10.20051/j.issn.1003-4722.2025.01.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Zhang C, Lai SX, Wang HP. Structural modal parameter recognition and related damage identification methods under environmental excitations: a review. Struct Durab Health Monit. 2025;19(1):25–54. doi:10.32604/sdhm.2024.053662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools