Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Segmentation of Building Surface Cracks by Incorporating Attention Mechanism and Dilation-Wise Residual

1 School of Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence, Hunan University of Technology, Zhuzhou, 412007, China

2 School of Computer, Hunan University of Technology and Business, Changsha, 410000, China

* Corresponding Author: Mansheng Xiao. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: AI-driven Monitoring, Condition Assessment, and Data Analytics for Enhancing Infrastructure Resilience)

Structural Durability & Health Monitoring 2025, 19(6), 1635-1656. https://doi.org/10.32604/sdhm.2025.068822

Received 06 June 2025; Accepted 11 August 2025; Issue published 17 November 2025

Abstract

During the operation, maintenance and upkeep of concrete buildings, surface cracks are often regarded as important warning signs of potential damage. Their precise segmentation plays a key role in assessing the health of a building. Traditional manual inspection is subjective, inefficient and has safety hazards. In contrast, current mainstream computer vision–based crack segmentation methods still suffer from missed detections, false detections, and segmentation discontinuities. These problems are particularly evident when dealing with small cracks, complex backgrounds, and blurred boundaries. For this reason, this paper proposes a lightweight building surface crack segmentation method, HL-YOLO, based on YOLOv11n-seg, which integrates an attention mechanism and a dilation-wise residual structure. First, we design a lightweight backbone network, RCSAA-Net, which combines ResNet50, capable of multi-scale feature extraction, with a custom Channel-Spatial Aggregation Attention (CSAA) module. This design boosts the model’s capacity to extract features of fine cracks and complex backgrounds. Among them, the CSAA module enhances the model’s attention to critical crack areas by capturing global dependencies in feature maps. Secondly, we construct an enhanced Content-aware ReAssembly of FEatures (ProCARAFE) module. It introduces a larger receptive field and dynamic kernel generation mechanism to achieve the reconstruction and accurate restoration of crack edge details. Finally, a Dilation-wise Residual (DWR) structure is introduced to reconstruct the C3k2 modules in the neck. It enhances multi-scale feature extraction and long-range contextual information fusion capabilities through multi-rate depthwise dilated convolutions. The improved model’s superiority and generalization ability have been validated through experiments on the self-built dataset. Compared to the baseline model, HL-YOLO improves mean Average Precision at 0.5 IoU by 4.1%, and increases the mean Intersection over Union (mIoU) by 4.86%, with only 3.12 million parameters. These results indicate that HL-YOLO can efficiently and accurately identify cracks on building surfaces, meeting the demand for rapid detection and providing an effective technical solution for real-time crack monitoring.Keywords

Due to various factors, concrete structures such as houses, bridges, and roads are prone to varying degrees of damage during service. Among these, surface cracks are one of the most obvious signs of deterioration, and are often regarded as important warning signals of potential damage. To effectively monitor the health of concrete structures, precise detection and quantitative analysis of crack patterns are urgently needed. This can provide critical data support for maintenance decision-making and service life prediction of infrastructure.

Traditional manual inspection relies on the inspector’s expertise and experience. However, it is constrained by physical condition and equipment, making it difficult to apply in inaccessible areas such as high bridges and narrow spaces. In recent decades, scholars have proposed numerous automated crack detection methods based on images or videos, such as object detection and crack segmentation. Although object detection can identify cracks, it cannot adequately capture their morphological features. As a result, key parameters such as length and width cannot be calculated, making it difficult to provide specific information for subsequent maintenance [1–3]. Therefore, more accurate pixel-level segmentation methods are needed. One type of approach is traditional image processing methods, which rely on the grayscale distribution, edge features, and frequency domain information of the image. Although these methods are computationally efficient, they are sensitive to variations in illumination, texture, and color. Moreover, they rely on manual feature extraction and do not consider the spatial information of the image, resulting in poor continuity of the segmentation results [4]. The other type is based on deep learning (DL). These methods automatically extract multi-scale features through end-to-end networks, and have become the mainstream of current crack segmentation research. They have achieved significant results in concrete crack segmentation tasks [5–7]. However, due to their complex structure and high parameter count, such approaches are challenging to deploy on resource-constrained edge devices. To this end, researchers have proposed a series of lightweight network architectures. These architectures reduce model complexity and computational demand while maintaining segmentation accuracy. This significantly enhances the feasibility of practical deployment. For example, references [8,9] respectively proposed lightweight semantic segmentation models for pavement cracks and underwater dam cracks, achieving certain improvements in both accuracy and deploy ability. In fact, although these models have certain advantages in terms of segmentation accuracy, their inference speed still cannot satisfy the real-time demands of engineering applications. In contrast, the YOLO series of single-stage segmentation models not only achieve good segmentation performance but also significantly improve detection speed [10,11]. Therefore, these models are particularly suitable for concrete building surface crack segmentation tasks in engineering applications that have high real-time requirements. Considering the rapid development of the YOLO series, we conducted comparative experiments on different versions and their corresponding model scales. The results show that YOLOv11n-seg performs more stably in complex backgrounds and fine crack segmentation, while effectively balancing segmentation accuracy and inference speed. It is worth noting that although YOLOv12n-seg, as a newer version, has fewer parameters and lower computational complexity than YOLOv11n-seg, its performance in key metrics such as accuracy is inferior to that of the latter.

To address the above issues, we combined the attention mechanism and the dilation-wise residual structure, proposing a lightweight building surface crack segmentation method based on YOLOv11-seg. We use ResNet50 [12] as the backbone network, exploiting its deep architecture and enhancing the model’s perception of fine cracks and complex backgrounds. On this basis, we introduce the CSAA module and design a lightweight backbone network with multi-scale feature extraction capability, named RCSAA-Net (ResNet50 with Channel-Spatial Aggregation Attention), to optimize the feature extraction process. In the feature reassembly stage, we design the ProCARAFE module. The module optimizes the channel compression process of the Content-aware ReAssembly of FEatures (CARAFE) [13] module using Efficient Channel Attention (ECA) [14]. This enables the model to adaptively retain channels with higher semantic contribution and improve crack edge restoration capabilities. In the neck network, we introduce the DWR [15] structure to reconstruct the C3k2 module, enhancing its ability to fuse long-range contextual information.

The following are this paper’s primary contributions:

(1) Design a novel lightweight backbone network, which optimizes the feature extraction process by integrating ResNet50 with channel-space aggregation attention modules.

(2) Design the ProCARAFE module, introduce channel screening mechanisms and content-aware mechanisms, and effectively restore crack edges and details.

(3) Improve the C3k2 module to enhance its ability to model long-range contextual information, thereby improving the precision of crack segmentation.

(4) Compared with mainstream models such as YOLOv12n-seg, Swin-Unet, and CrackFormer, HL-YOLO attains an optimal tradeoff between segmentation precision, model complexity, and inference speed with a parameter size of only 3.12 M. Specifically, HL-YOLO achieves

This paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews the developments in the field of crack segmentation. Section 3 introduces the overall framework of our method and its modules. Section 4 presents the dataset preparation and experimental settings. Section 5 analyzes the experimental results. Section 6 summarizes the paper.

This section reviews several typical crack segmentation algorithms, mainly including traditional image processing techniques and deep learning-based methods.

Crack segmentation methods based on image processing include thresholding [16], edge detection [17], wavelet transform [18] and so on. These approaches primarily depend on handcrafted rules and low-level visual features for crack extraction. Reference [19] employs threshold segmentation technology to segment cracks by leveraging the grayscale differences between cracks and the background. Although these methods are simple to implement, they are sensitive to parameter selection. In this context, edge detection has been widely applied in crack segmentation. For example, Yang et al. [20] introduced a hybrid model that integrates Otsu binarization, edge detection, and Swin-Transformer. The model achieves precise crack segmentation and provides an important reference for analyzing crack morphology and predicting crack propagation. However, these methods can only identify non-intersecting crack segments and perform poorly in images with low contrast or high noise. Therefore, wavelet transform has been widely adopted in crack segmentation due to its strong ability to describe local features. Shao and Du [21] focused on the identification of surface cracks and proposed a Rayleigh wave time-frequency analysis method for crack detection based on wavelet transform, which improves the accuracy of crack detection by calculating the time difference relationship. However, such methods are sensitive to noise, have limited feature representation ability, and strongly depend on parameter settings. These drawbacks make it difficult to effectively handle crack images with complex morphology or significant background interference.

With the evolution of deep learning and neural networks, crack segmentation methods based on Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have become a mainstream research direction [22–24]. For example, Yuan et al. [25] proposed a segmentation method for bridge cracks based on DeepLabv3+, which incorporates a parallel attention module and multi-scale feature integration. Zhang et al. [26] proposed a recursive adaptive network based on High-resolution Network (HRNet) for pixel-level road crack segmentation. Wang et al. [27] combined CNN and Transformer to construct a dual-path network for road crack segmentation. Yu et al. [28] built an efficient crack segmentation network called Crack Swin TransFormer (CSTF) by introducing a feature pyramid pooling module and a dual-branch decoder based on the Swin Transformer. Zhang et al. [29] introduced multi-path propagation and multi-scale feature integration. Based on this, they designed the U-Net-feature map-multipath propagation-layer fusion (U-Net-FML) model. It reduces the parameter count and enhances U-Net’s capacity to segment cracks from the background. However, due to high computational complexity and limited inference efficiency, these models are unsuitable for deployment on resource-constrained edge devices. To balance segmentation accuracy and inference efficiency, researchers have begun to explore the design and optimization of lightweight models. Therefore, the YOLO series architectures have been widely adopted. For example, Wu et al. [30] proposed an improved single-stage instance segmentation model, which was applied to crack segmentation in dams and bridges. Ye et al. [31] proposed an enhanced YOLOv7 framework for high-precision instance segmentation of pavement cracks, providing an efficient and practical approach for multi-scenario concrete crack detection. Zhang et al. [32] improved the YOLOv4 backbone network and optimized the feature fusion module, achieving fast and accurate crack detection and segmentation. Xiong et al. [33] designed the YOLOv8-AFPN-MPD-IoU model by incorporating a progressive feature pyramid network for bridge surface crack segmentation and quantification. Yang et al. [34] constructed a crack segmentation algorithm based on improved YOLOv7 and SeaFormer models, enabling automated detection of concrete bridges. Xu et al. [35] combined the large separable kernel attention with an improved feature extraction module. They also introduced network pruning and knowledge distillation to construct a concrete structure crack segmentation method based on YOLOv8-seg. Yao et al. [36] proposed MDFNet, a segmentation network that fuses multi-level defect features, based on an improved YOLOv11-seg. The network demonstrates its effectiveness in crack and dent detection for concrete structures through a collaborative detection and segmentation framework. Yang et al. [37] combined a dual-layer routing strategy and gather-and-distribute mechanism with the YOLOv8x-seg algorithm, and proposed YOLOv8-GSD, a segmentation method for subway tunnel crack detection. Although current lightweight segmentation models have advantages in inference speed and deployment efficiency, they still have shortcomings. References [30,34,35] suffer from missed detections and segmentation discontinuities when handling crack images with complex backgrounds, structural intricacies, or blurred edges. While references [31–33,36,37] have made progress in fine crack segmentation, their experiments were conducted in relatively ideal environments. They lack sufficient research on crack segmentation under complex backgrounds.

3.1 Overview of the HL-YOLO Model

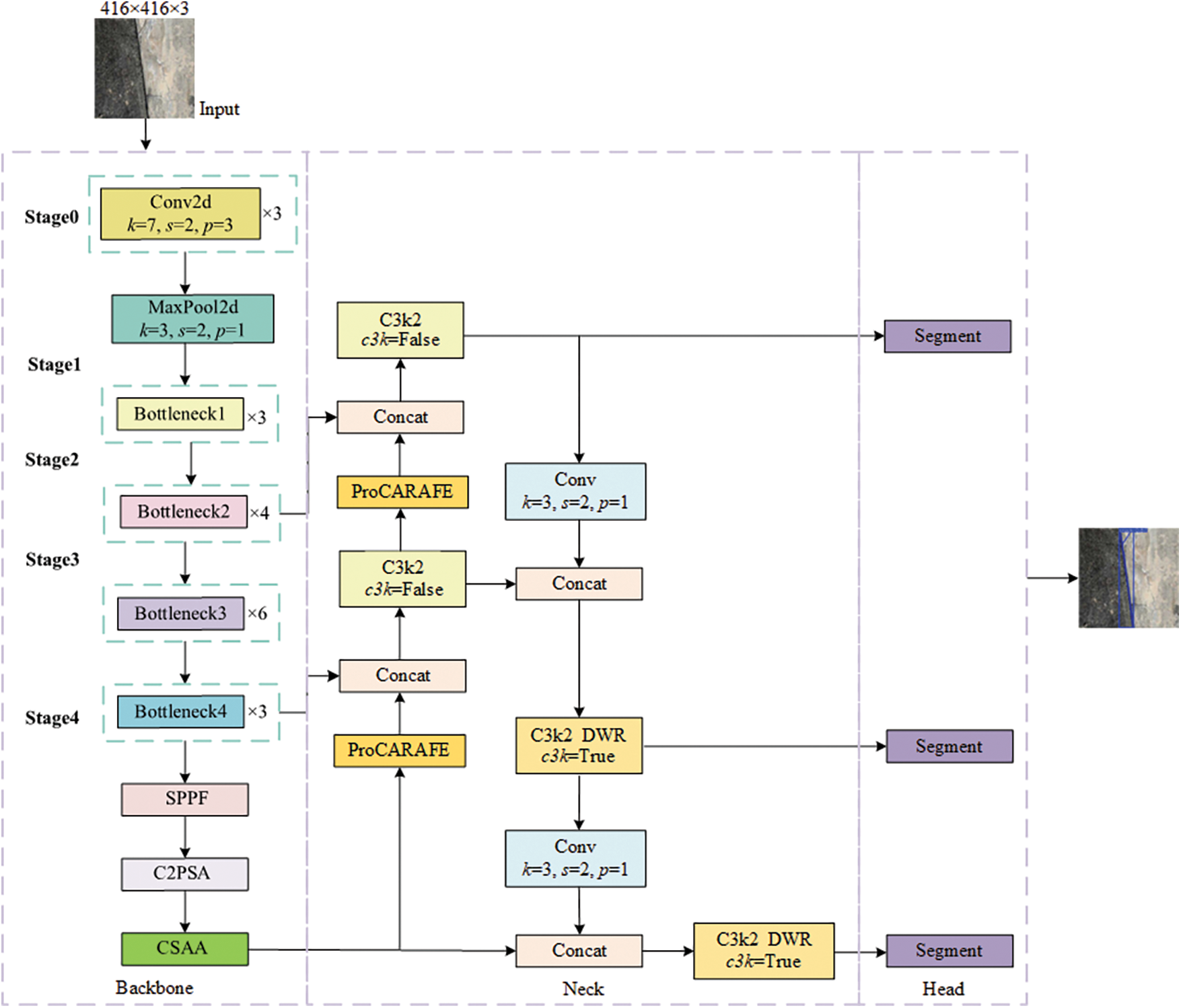

YOLOv11n-seg encounters issues of missed detections, false detections, and segmentation discontinuities when handling fine cracks on building surfaces with complex backgrounds and blurred boundaries. To address these problems, we proposes an end-to-end crack segmentation model and develops a comprehensive data processing and inference workflow. First, crack images of campus and urban building surfaces are collected and undergo preprocessing operations such as cropping and augmentation. A new training set is created by combining the Roboflow crack dataset and the preprocessed images. Next, the proposed HL-YOLO model is trained using this training set. Finally, the trained model is used to perform inference on test images to obtain pixel-level crack segmentation masks. The structure of HL-YOLO can be seen in Fig. 1 below.

Figure 1: Improved model HL-YOLO structure

3.2 YOLOv11n-Seg Model Structure

YOLOv11n-seg is a lightweight instance segmentation model released by Ultralytics in September 2024. Based on varying depths and widths, it is divided into five versions (n, s, m, l and x). Its architecture mainly comprises a backbone, a neck and a head. The backbone captures multi-scale information from the input image and generates feature maps at various resolutions. The neck integrates these features to ensure that each feature map contains rich contextual information. Ultimately, the head processes the refined feature map via non-maximum suppression and produces the optimal solution of anchor boxes and segmentation masks. YOLOv11n-seg uses an improved version of CSPDarknet53 as the backbone. Based on this, it introduces the C3k2 module and the Channel and Position Spatial Attention (C2PSA). By partially connecting feature maps across stages and utilizing the Space Pyramid Pooling Fast (SPPF) module, the improved CSPDarknet53 pools feature maps to a fixed size. The C2PSA module enhances the model’s attention on specific areas through multi-scale convolution and channel weighting. The C3k2 module is placed in multiple channels such as the neck and head to process multi-scale features. The module implements a flexible feature extraction strategy by controlling the c3k parameter. When c3k = False, a lightweight and computationally efficient C2f module is used; when c3k = True, a deeper C3 module is employed. Due to scene restrictions, c3k is usually set to False by default. For larger network versions, such as m, l and x, it is set to True, while for smaller versions like n and s, it remains False [38].

3.3 Backbone Network with Integrated Channel-Spatial Attention

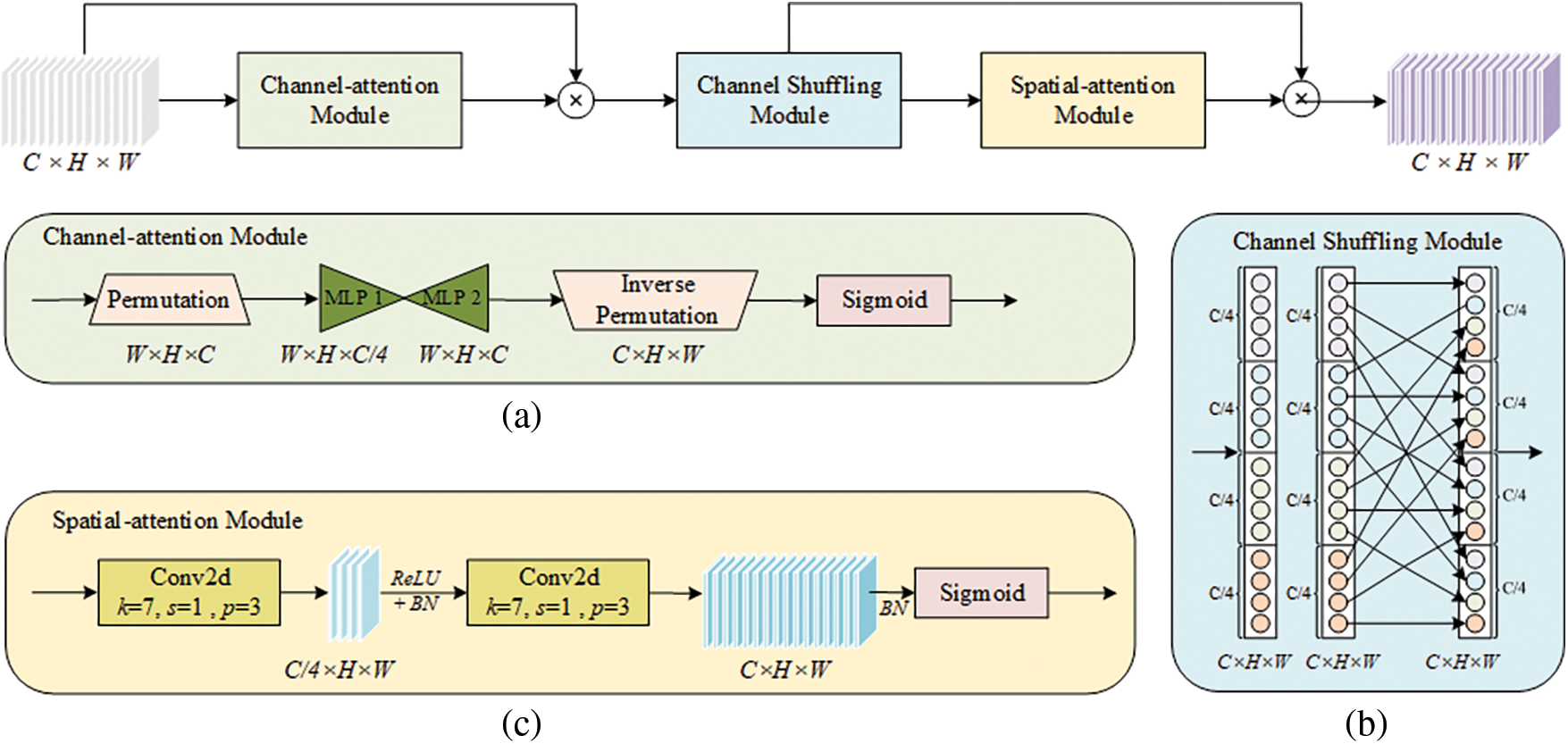

Although the backbone of YOLOv11n-seg has achieved a certain degree of feature representation diversity, deep feature extraction still faces challenges such as gradient vanishing and insufficient multi-scale feature fusion. In addition, crack backgrounds are easily affected by material textures, lighting conditions and noise, which increases the complexity of feature extraction. To address the above problems, we adopt ResNet50 as the backbone. However, when dealing with cracks in complex backgrounds, it tends to overlook the dependencies between channel and spatial information, resulting in the loss of critical crack features. To this end, the CSAA module, see Fig. 2 below, is further introduced to compensate for the lack of attention to channel and spatial information. Ultimately, ResNet50 is integrated with the CSAA module to build a new backbone network, named RCSAA-Net.

Figure 2: CSAA module structure. (a) Channel-attention module; (b) Channel Shuffling module; (c) Spatial-attention module

ResNet50 serves as the backbone and is composed of multiple residual blocks. It effectively captures multi-scale features of crack images from low-level textures to high-level semantics. To further enhance attention to the key features, the CSAA module is introduced after the C2PSA module. The module first permutes the input feature map dimensions from C × H × W to W × H × C. This converts the channel dimension to a feature dimension that can be perceived by the Multilayer Perceptron (MLP). Subsequently, the dependencies between channels are captured through two MLP layers, enabling the network to adaptively strengthen its channel response to crack features. The first layer compresses the channel dimension to one-fourth of its original size, generating a feature map of dimensions W × H × C/4 and applying the ReLU activation function for nonlinear transformation. The second layer restores the channel dimension to W × H × C, and then recovers it to C × H × W through inverse permutation. Then, the channel attention map is yielded through the Sigmoid activation function. The above process is denoted as:

where X is the original input feature map, P−1 denotes the inverse permutation operation,

Finally, the enhanced feature map is generated by element-wise multiplying the attention map with the input feature map. The above process is denoted as:

where F′ is the feature map after channel attention, and ⊙ represents element-wise multiplication.

To further mix the feature information, a channel shuffling operation is applied. The enhanced feature map is divided into 4 groups, each with a size of W × H × C/4. The order of channels within each group is randomized through a transposition operation. The feature map is then recovered to its original size of W × H × C, breaking the isolation of channel information between groups. The above process is denoted as:

where

Building upon the previous two modules, spatial attention is further incorporated to weight the spatial features. First, a 7 × 7 convolutional layer reduces the channel count to C/4, producing a feature map of size C/4 × H × W. This reduces computational complexity while focusing on the spatial features of the crack location. The feature map then undergoes Batch Normalization (BN) and is activated by a ReLU function to introduce nonlinearity. The second convolutional layer restores the channel dimension to the original shape C × H × W. It then generates a spatial attention map through the BN layer and the Sigmoid activation function. The above process is denoted as:

where

Ultimately, the final feature map is generated by element-wise multiplying the spatial attention map with the shuffled feature map. The formula is given as follows:

where

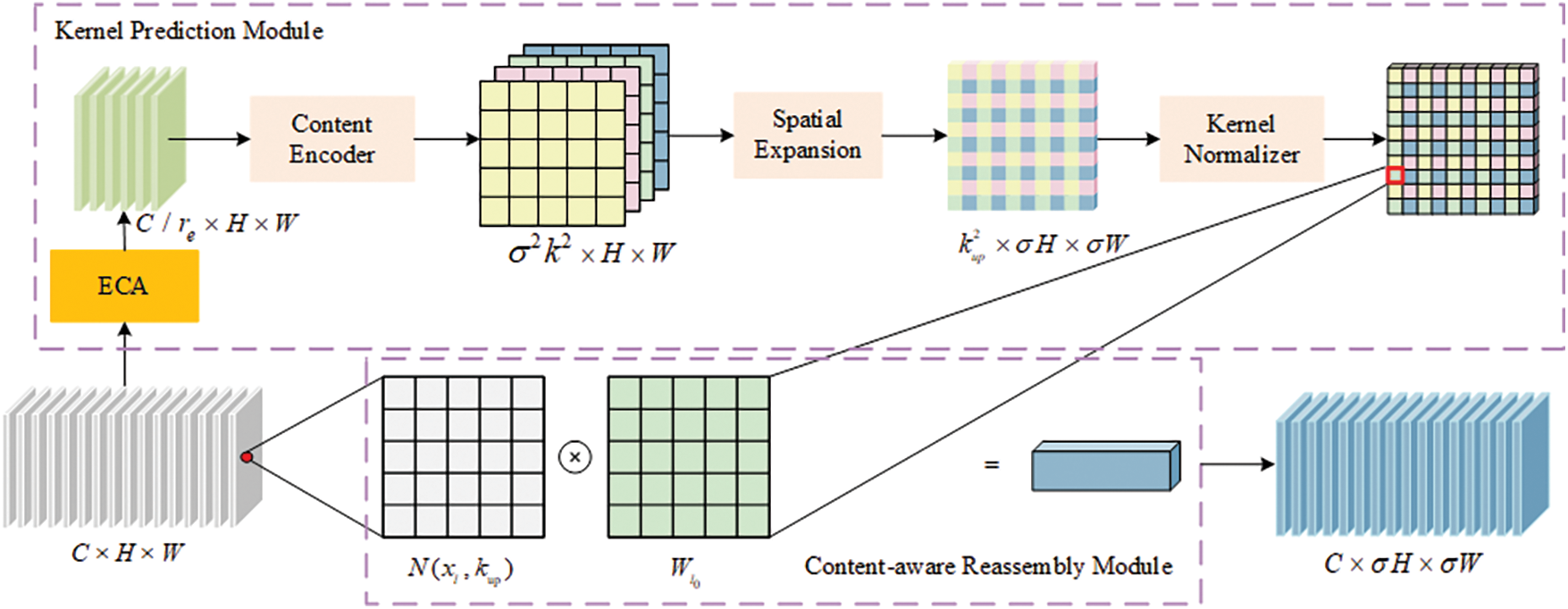

3.4 Enhanced Content-Aware Reassembly of Features Module

Given that cracks are fine, narrow, and have blurred boundaries, traditional nearest neighbor upsampling methods select the upsampling kernel rely solely on pixel location. These methods lack semantic awareness and have a limited receptive field. As a result, achieving high-resolution, semantically rich features becomes challenging, which adversely affects the restoration of crack edge features and the reconstruction of fine details. For that purpose, this paper proposes the ProCARAFE module, illustrated in Fig. 3, to replace the original upsampling module of YOLOv11n-seg.

Figure 3: ProCARAFE module structure

The ProCARAFE module focuses on an efficient upsampling process guided by semantics. It combines the ECA channel selection mechanism with the CARAFE content-aware mechanism to achieve collaborative optimization of channel selection and spatial reconstruction. Unlike the channel compressor in the CARAFE module, ECA dynamically weights the channels of the input feature map and adaptively retains channels with higher semantic contribution. This is an attention-guided soft compression strategy that can more effectively retain key semantic information compared to fixed-ratio compression methods. We assume that the input feature map is of size C × H × W, and the upsampling rate is σ. The input feature map is compressed to the Cm channels through the ECA channel selection mechanism. Subsequently, the feature is content-encoded using a kup × kup convolution layer to generate a recomposed kernel, generating a feature map with a size of

To ensure the effectiveness and efficiency of the ProCARAFE module in crack segmentation tasks, the hyperparameter settings in this paper mainly refer to the recommended values of the CARAFE module. Specifically, the kernel size kup = 5 covers a relatively large neighborhood. It helps capture rich contextual information and improves the ability to reconstruct fine details during upsampling. The kernel size for encoding, kencoder = 3, balances the expressive capability of feature encoding and computational complexity. The upsampling factor σ = 2 meets the practical requirement of doubling the feature map’s size. In the ECA module, the channel compression ratio Cm = C/re. The compression factor re = 4 is a reasonable setting determined based on experimental tuning results, balancing model performance and computational resource consumption.

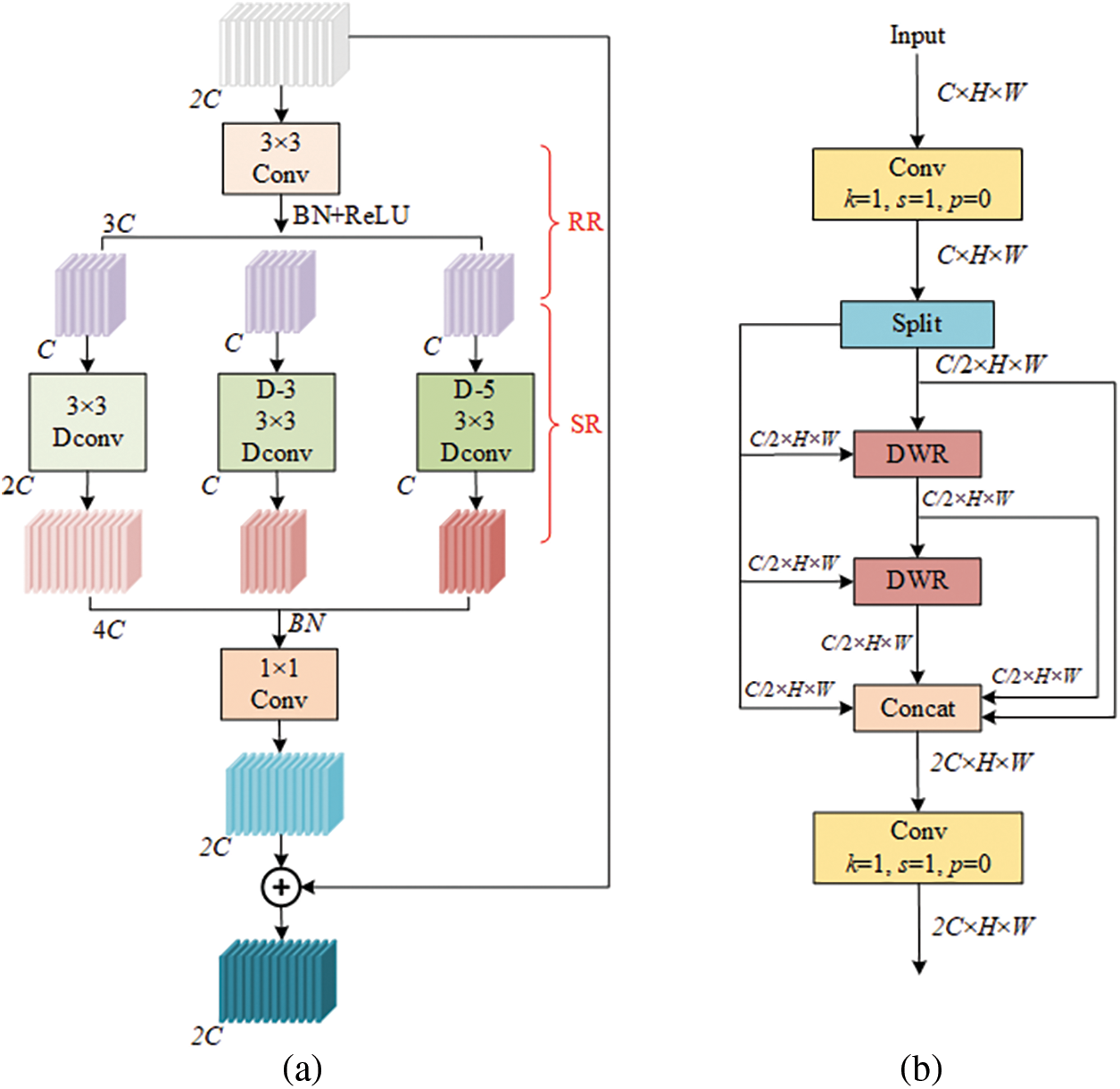

3.5 Improved Dilation-Wise Residual Module

Since this paper uses the smaller YOLOv11n-seg, the c3k parameter in the C3k2 module is set to False. The C2f module is adopted for feature extraction to retain the basic feature capture capability. Although the C2f module enriches gradient information by parallelizing multiple gradient flow branches, it is limited by the fixed receptive field. It still has shortcomings in extracting multi-scale features and fusing long-distance context information. Moreover, stacking multiple Bottleneck blocks in the C2f module leads to redundant skip connections and split operations, significantly increasing the computational complexity. To address the above issues, the C3k2 module is redesigned using the DWR module. Fig. 4a illustrates the structure of DWR. By utilizing a two-step method, the module effectively extracts multi-scale contextual information. In the first step, regional features are captured through a 3 × 3 convolution, followed by three parallel branches to expand the receptive field. Each branch applies depthwise separable dilated convolutions with different dilation rates. In the second step, features are refined based on the receptive field size to ensure semantic consistency across scales.

Figure 4: (a) DWR module structure; (b) C3k2-DWR module structure. Here, RR stands for regional residualization, and SR for semantic residualization. Conv denotes a convolutional block, while DConv refers to depthwise separable dilated convolution. The parameter n indicates the dilation rate

Fig. 4b shows the C3k2-DWR module constructed in this paper. The module is composed of a Conv layer, a DWR layer, and a separation layer, where the DWR module replaces the Bottleneck modules in the C2f module. The improved module fully integrates multiple convolution processes with different expansion rates. This enhances the network’s capacity to extract features of objects at multiple scales.

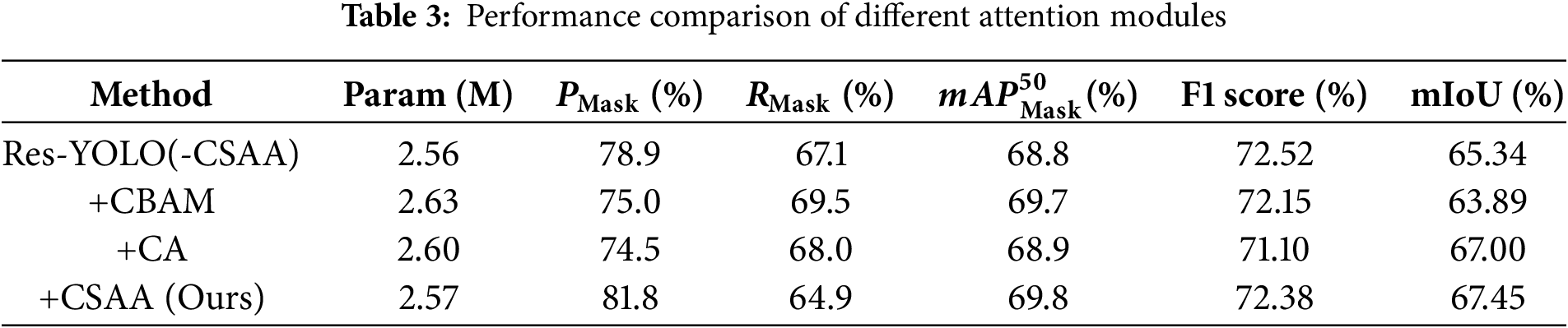

4 Datasets and Experimental Design

Previous studies were mostly based on self-built datasets with fewer than 1300 images. These datasets cover limited scenes and are not publicly available [39–41], leading to a lack of unified standards for model evaluation. To address this issue, this paper uses the publicly available Roboflow crack segmentation dataset (https://universe.roboflow.com/university-bswxt/crack-bphdr, accessed on 10 July 2025). It contains 4029 crack images of pavements, walls, and other scenes taken in different locations, environments and lighting conditions. All images are of 416 × 416 pixel resolution. It includes pixel-level manual annotations that have been reviewed and refined by industry experts, ensuring high accuracy and domain professionalism.

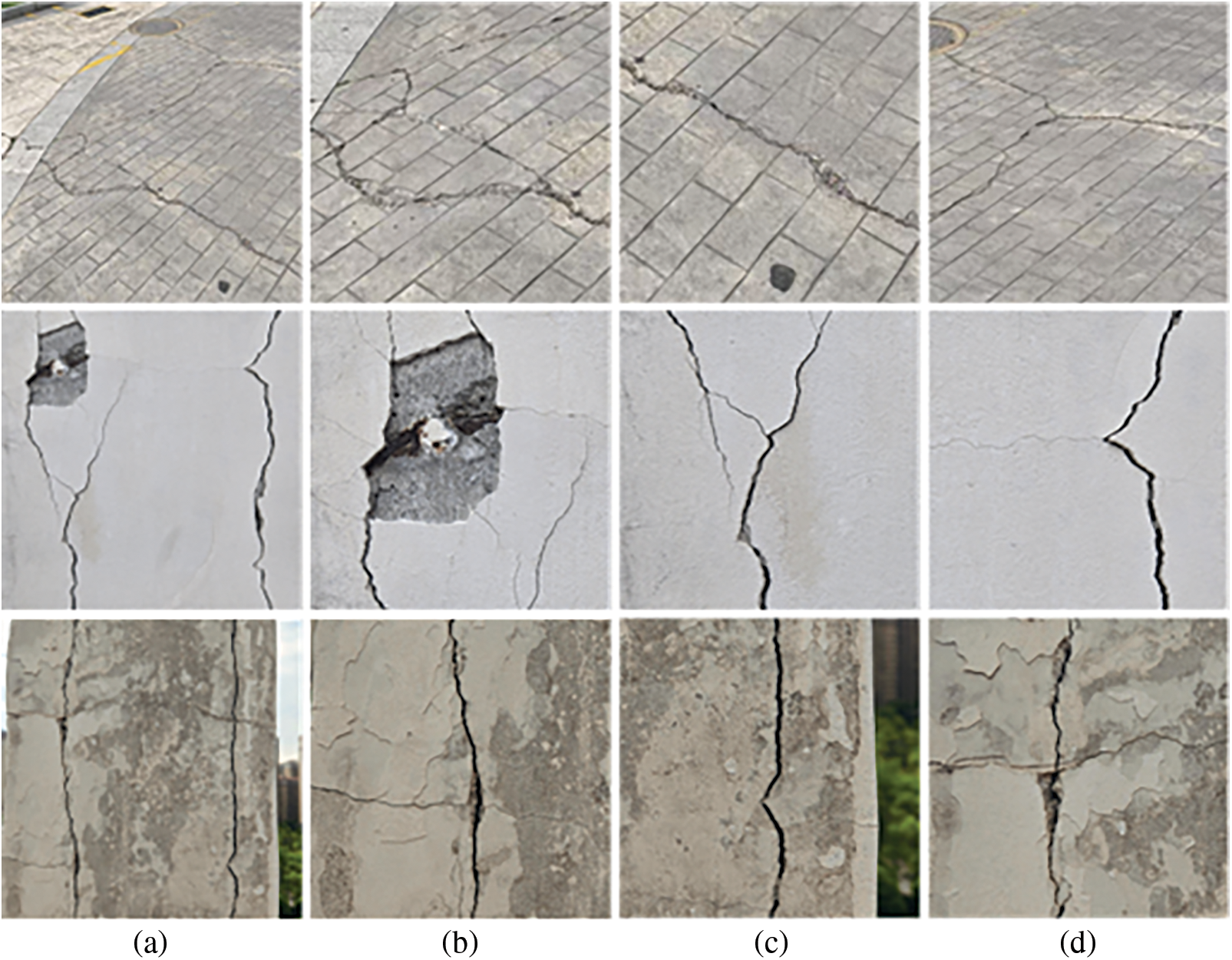

To strengthen the model’s generalization capability in real complex environments, we constructed a supplementary crack dataset. The dataset consists of 400 high-resolution original images (3000 × 4000 pixels) collected by the authors using a Samsung Galaxy S24 smartphone under natural light. These images cover typical crack distribution areas in both the campus and urban environments, including building walls and ground surfaces. To meet the network’s input requirements, we randomly cropped 3 non-overlapping 416 × 416 pixel patches from each original image, yielding a total of 1200 initial images. The cropping uses a random sampling method guided by the crack area without a fixed stride, allowing partial overlap to ensure that each cropped patch contains valid crack information. After cropping, the proportion of crack pixels in each patch was calculated, and samples with less than 1% crack pixel ratio were discarded to reduce interference from crack-free backgrounds during training. Fig. 5 shows some original images and cropped images of the self-built dataset. It was randomly split into training, validation, and test sets in an 8:1:1 ratio. The training set was expanded to 1500 images through data augmentation strategies such as brightness variation and random flipping. Crack areas are annotated using the open-source labeling tool Labelme. The validation set and test set are not augmented in any way. All images contain crack targets, and the class distribution remains consistent after augmentation, with no class imbalance issues. Additionally, since the training set of the Roboflow crack segmentation dataset already includes augmented samples, no additional data augmentation was applied in this study. Table 1 summarizes the sample sizes, augmentation methods, and data splits for both datasets. To enhance the model’s robustness, the augmented self-built training set was merged with the Roboflow training set to form a mixed train set of 5217 images. The model was tested on the Roboflow test set (112 images) and the self-built test set (120 images) to assess its performance in both standard environments and real scenarios.

Figure 5: Samples from self-built dataset. (a) Original image, (b–d) Cropped image

Although accuracy is a key metric in current instance segmentation models, the rise of lightweight architectures has made it equally important to consider model efficiency and complexity for practical deployment. Therefore, the evaluation employs multiple metrics, including Mask Precision (PMask), Mask Recall (RMask), mean average precision at IoU threshold 0.50 (

where TP, FP, and FN denote the numbers of true positives, false positives, and false negatives, respectively; C is the number of segmentation classes, and AP denotes the average precision for each segmentation class.

All experiments are conducted on an Ubuntu 18.04 system using Python 3.8 and PyTorch 2.4.1. The hardware platform comprises an Intel® Xeon® Platinum 8358P processor and an RTX 3090 GPU, with acceleration provided by the NVIDIA CUDA 11.3 toolkit. Model training employs Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) as the optimizer for 150 iterations, with an initial learning rate of 0.01, a batch size of 8, a weight decay of 0.0005, and a momentum of 0.937.

5 Experimental Results and Analysis

This section is divided into six subsections: comparative experiments on model scales, comparative experiments on different attention modules, comparative experiments on the integration of the C3K2_DWR module, ablation experiments, comparative experiments on different models, and visual analysis of crack segmentation results from different models. Our experiments evaluate performance in terms of PMask, RMask,

5.1 Comparative Experiments on Model Scales

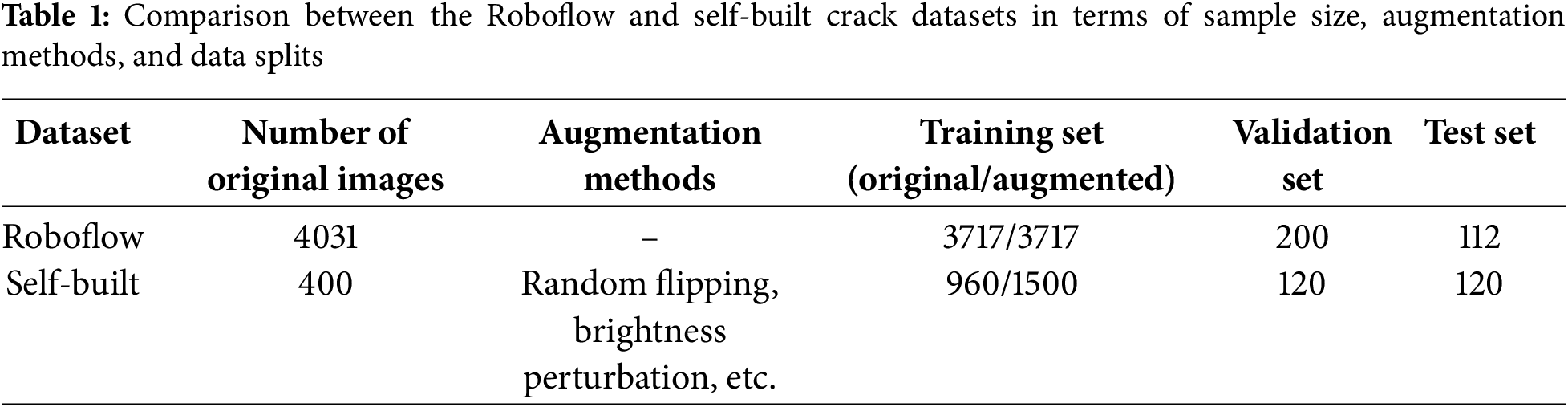

To determine the optimal model scale, we trained models on the mixed training set. We then conducted comparative experiments on YOLOv11-seg models of different scales using both the Roboflow crack segmentation test set and the self-built test set. Table 2 shows the results on the representative self-built test set. The results show that the model with scale n has the highest

5.2 Comparative Experiments on Different Attention Modules

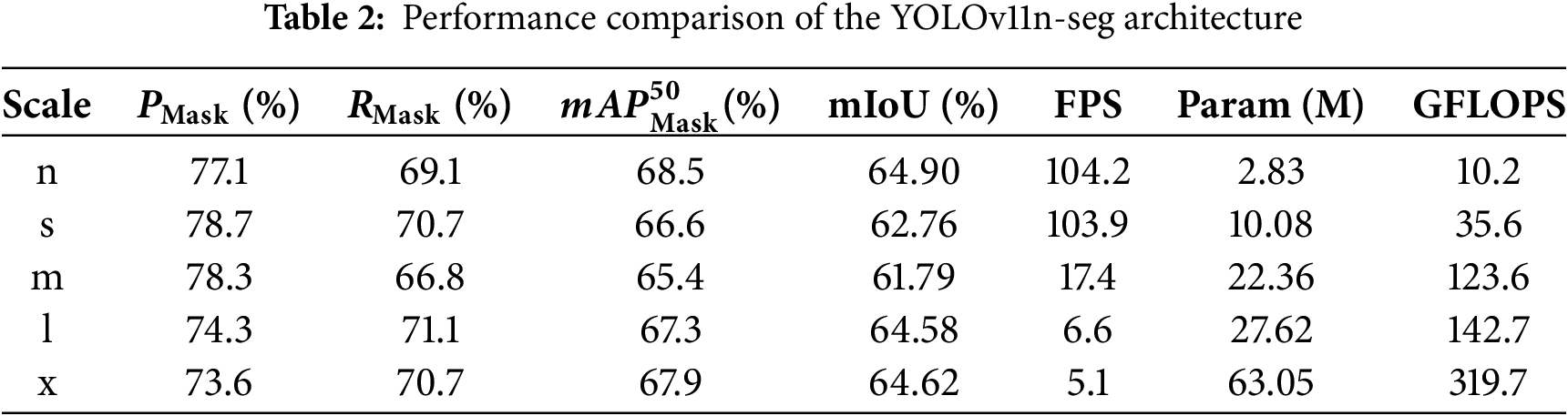

To analyze the performance differences between the CSAA module and other attention modules, we selected the YOLOv11n-seg + ResNet50 model as the baseline, denoted as Res-YOLO(-CSAA). Next, the CSAA module and other common attention modules, such as CBAM and CA, were added respectively for comparison. As shown in Table 3, Res-YOLO exhibits shortcomings in segmentation details. After introducing the Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) module, although the recall rate is higher, the number of false detections increases. The CA module performs better in terms of mIoU but has a lower PMask. This indicates an advantage in improving segmentation boundary quality, but its overall accuracy is not well balanced. By contrast, the CSAA module outperforms other attention modules in key metrics such as PMask,

5.3 Comparative Experiments on the Integration of the C3K2_DWR Module

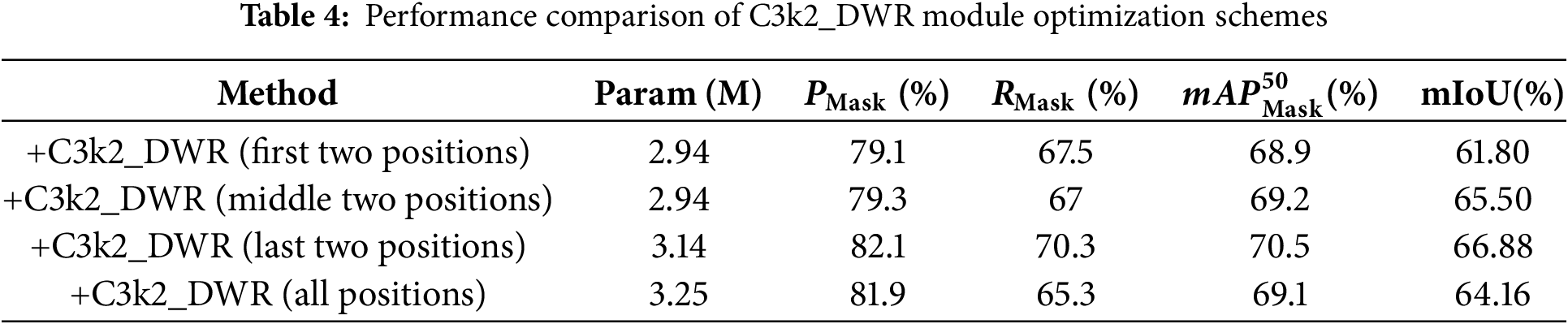

This paper proposes several optimization schemes based on C3K2_DWR modules, including replacing varying numbers of C3k2 modules at different locations in the neck, with c3k = True during replacement. After training on the mixed training set, several representative replacement schemes were selected for comparative experiments on both the Roboflow crack segmentation test set and the self-built test set. The hyperparameters and experimental conditions were kept consistent during the experiments. Table 4 shows the experimental results of the self-built test set. The scheme that replaces the C3k2_DWR modules only at the last two positions performs the best, achieving a

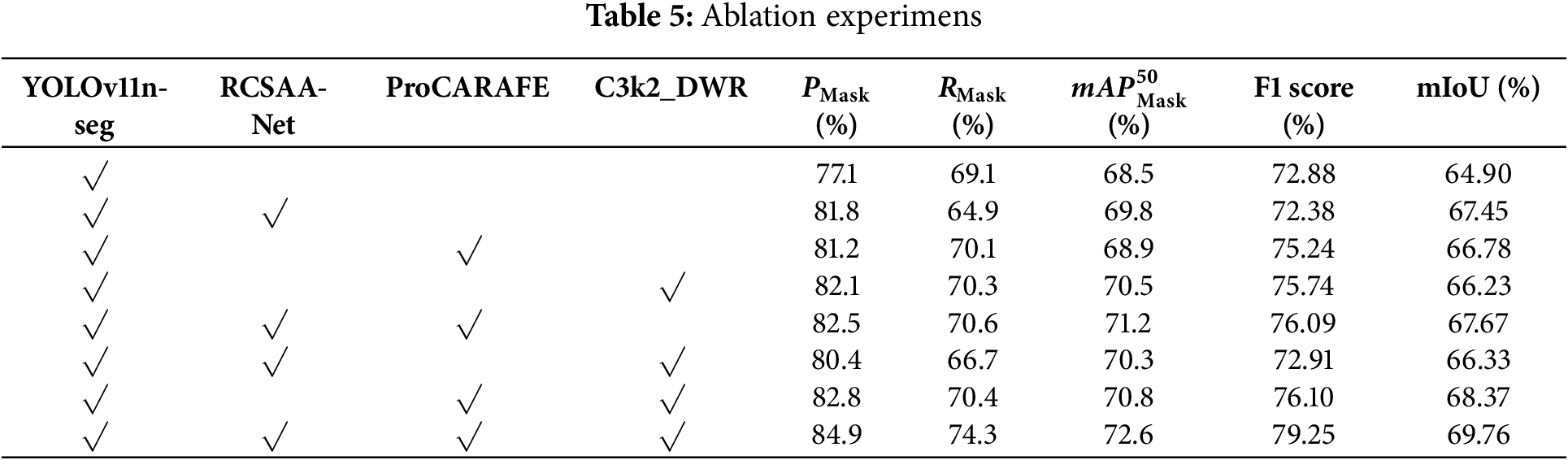

To validate the impact of the RCSAA-Net backbone, the ProCARAFE module, and the C3k2_DWR module on segmentation performance, we conduct ablation experiments. These experiments quantitatively analyze each module’s individual contribution and their combined effects. All experiments are performed under identical hyperparameter settings. As shown in Table 5, although the combination of multiple modules may lead to slight fluctuations in some metrics, the improved model (HL-YOLO) achieves the highest scores on key metrics. Specifically,

To further evaluate the combined effects, we analyzed various combinations of modules. Although integrating multiple modules improves model performance, the extent of enhancement differs greatly among different configurations. For instance, the combination of YOLOv11n-seg + RCSAA-Net + ProCARAFE performs better in terms of RMask and F1, while the combination of YOLOv11n-seg + ProCARAFE + C3k2_DWR performs better in PMask and mIoU. Specifically, the CSAA module consists of channel attention, the channel shuffle mechanism, and spatial attention to fully capture the global dependencies within the feature map, enabling the model to better focus on crack features. However, when dealing with fine cracks or cracks with blurred boundaries, its performance may degrade, making it difficult to simultaneously maintain high precision and recall. Meanwhile, the C3k2 module was replaced by the C3k2_DWR module, which enlarges the receptive field. It contributes to better coverage of crack regions. As RMask increases, the model achieves more comprehensive coverage of crack regions but also becomes more sensitive to background noise. It leads to a higher false detection rate, thereby negatively impacting PMask.

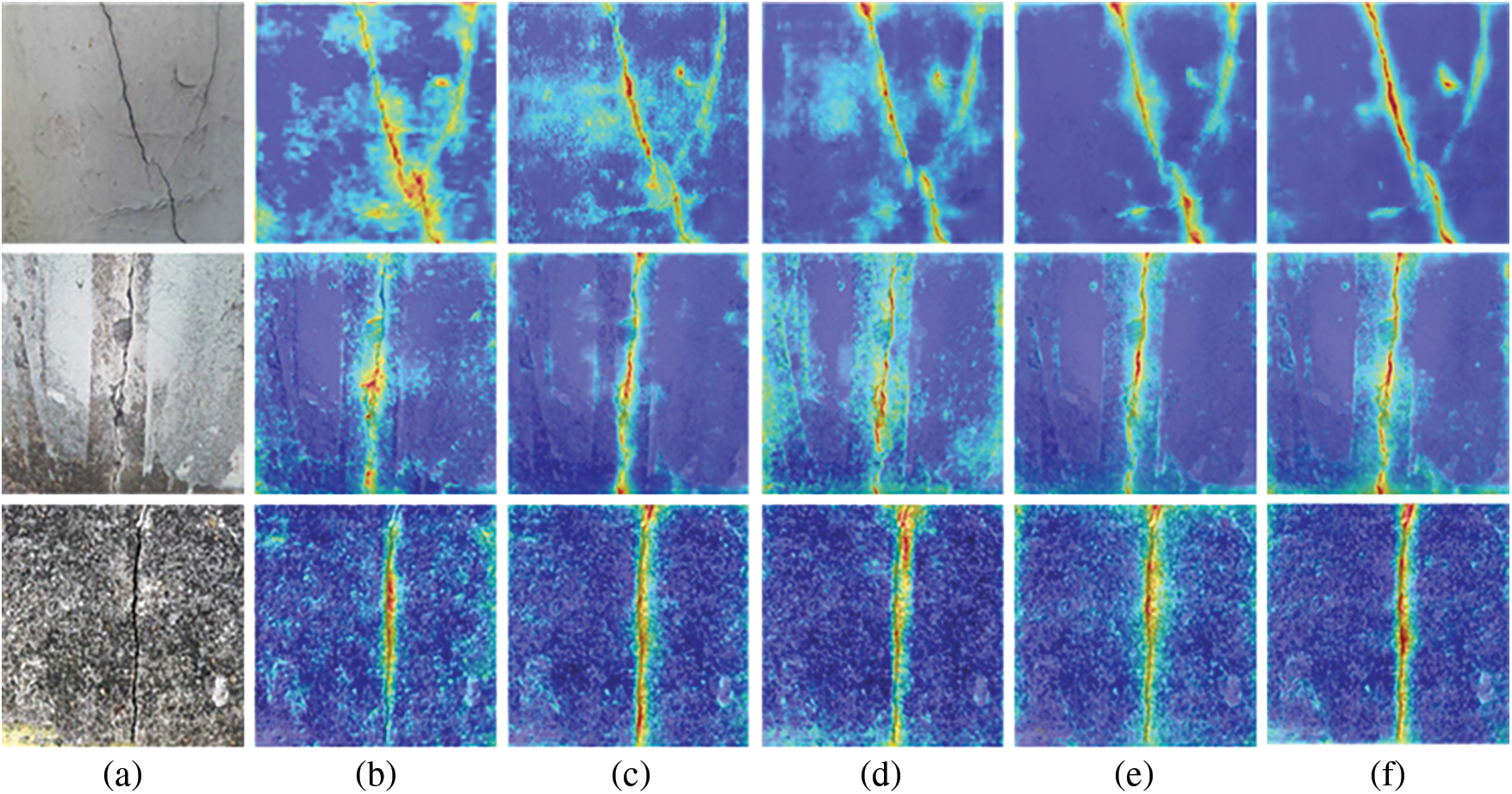

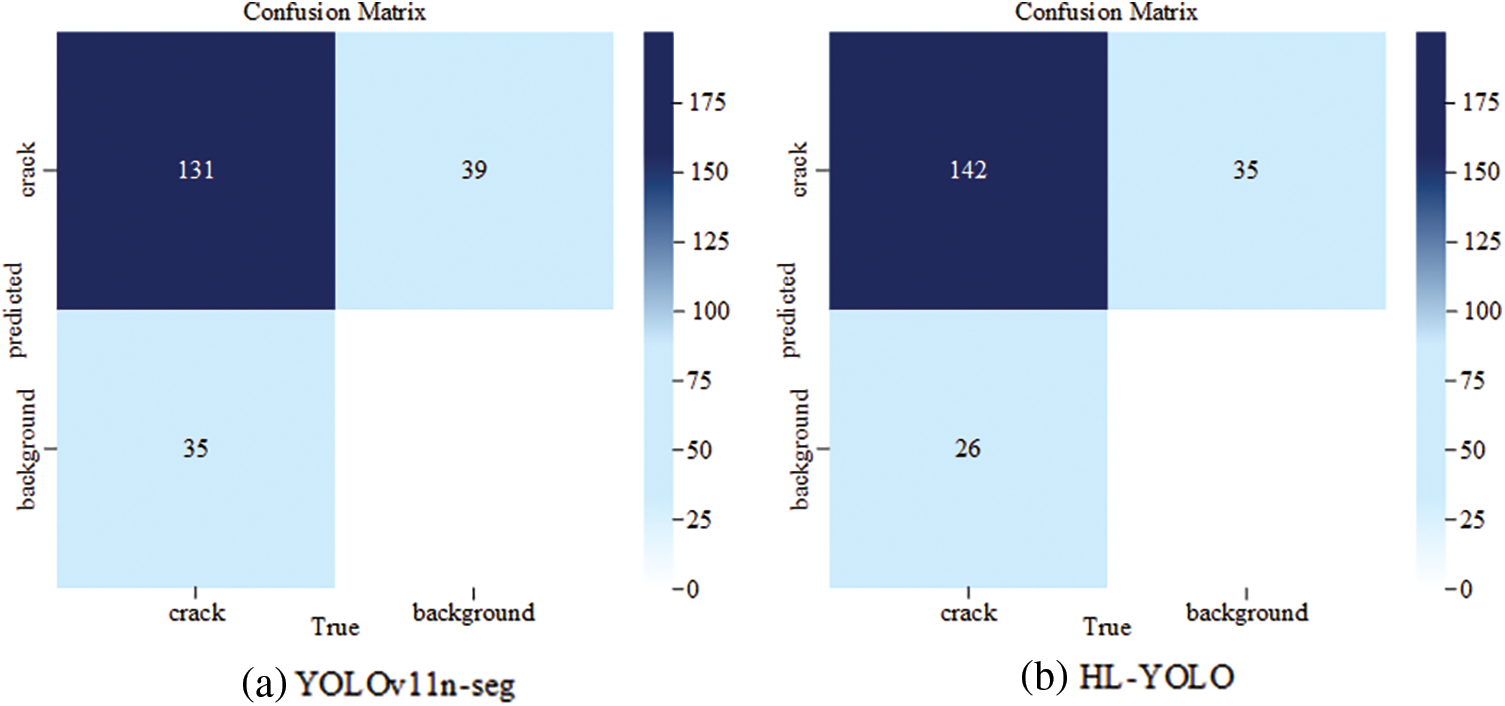

This paper selects a set of crack images featuring fine branches, complex backgrounds, and blurred boundaries, and performs feature heatmap visualization using the GradCAMPlusPlus method. In the resulting heatmaps, the red-highlighted regions indicate key feature areas that the model relies on for decision-making, with deeper colors indicating higher feature importance. Fig. 6 demonstrates that the original feature heatmaps of YOLOv11n-seg exhibit weak highlight regions and suffer from severe loss of detail information. In contrast, HL-YOLO shows more concentrated activation responses in the main crack structure, edge details, and blurred areas. Moreover, Fig. 7 presents the confusion matrices of YOLOv11n-seg and HL-YOLO based on predictions from samples in the self-built test set. The horizontal axis indicates the ground truth labels, while the vertical axis indicates the predicted labels. As shown in the figure, both models exhibit similar overall prediction trends, with occurrences of both false positives and false negatives. For example, YOLOv11n-seg pays insufficient attention to crack regions with fine and blurred boundaries, resulting in missed detections. In contrast, HL-YOLO alleviates this issue by introducing a channel-spatial aggregation attention mechanism. According to Fig. 6, the baseline model exhibits strong responses in background regions adjacent to complex crack areas, leading to false detections. In contrast, HL-YOLO effectively reduces the risk of such background interference by enhancing feature representation and contextual modeling capabilities. Compared to the baseline, the improved model yields fewer false detections and missed detections, along with a higher number of correctly identified samples.

Figure 6: Comparison of heatmap visualizations. (a) Original image; (b) YOLOv11-seg; (c) YOLOv11n-seg + RCSAA-Net; (d) YOLOv11n-seg + ProCARAFE; (e) YOLOv11n-seg + C3k2_DWR; (f) HL-YOLO

Figure 7: Confusion matrix

5.5 Comparative Experiments on Different Models

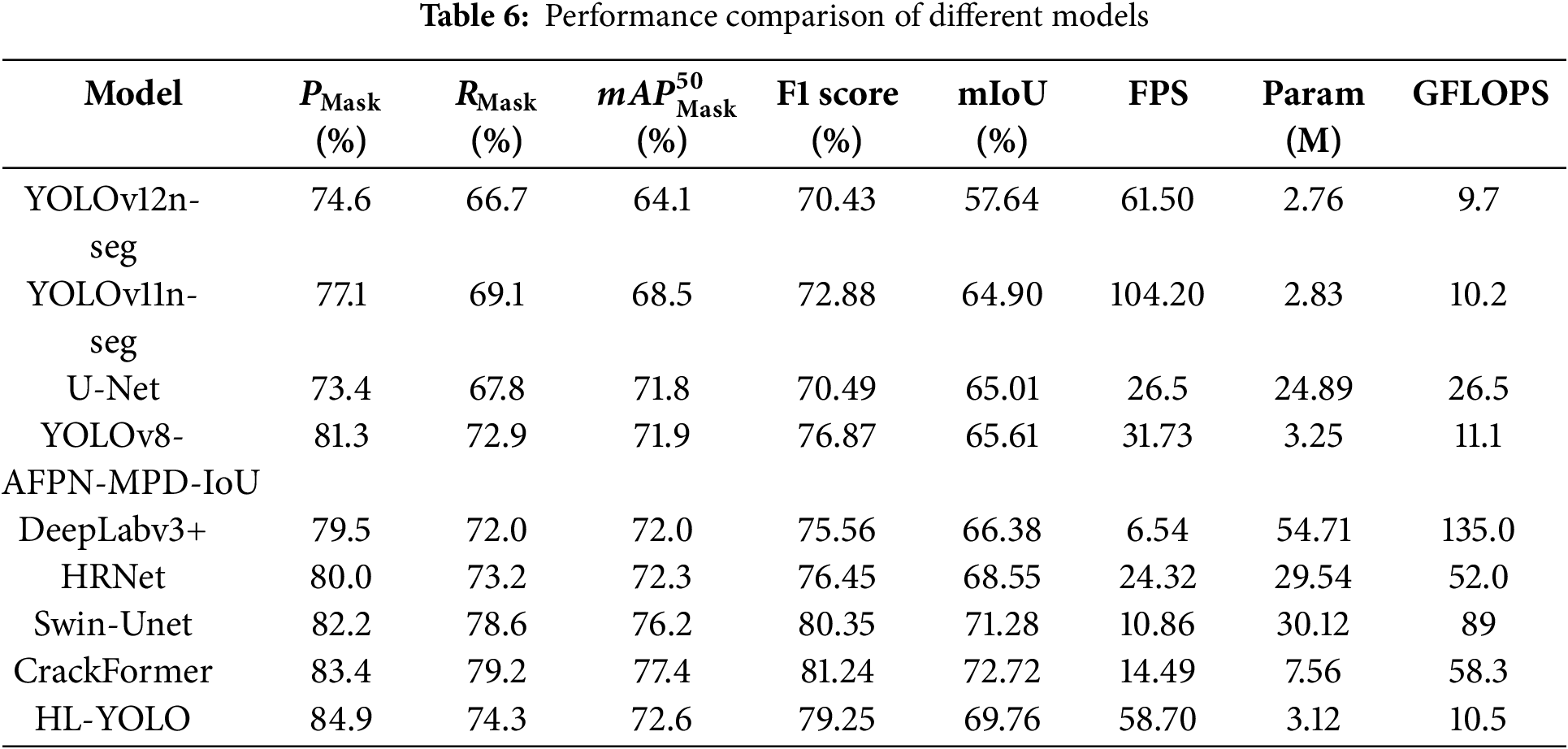

To further assess the effectiveness of HL-YOLO, we conducted a comparative analysis with advanced semantic segmentation models such as Swin-Unet [42], CrackFormer [43], HRNet, DeepLabv3+, and U-Net, as well as lightweight instance segmentation models including YOLOv12n-seg, YOLOv11n-seg, and YOLOv8-AFPN-MPD-IoU [33]. All experiments used the same dataset and experimental settings. Training hyperparameters were uniformly set unless otherwise specified in the original implementations. Table 6 illuminates the performance of HL-YOLO and comparison models on the self-built test set. The table shows that HL-YOLO outperforms the three lightweight instance segmentation models across all key metrics, particularly in

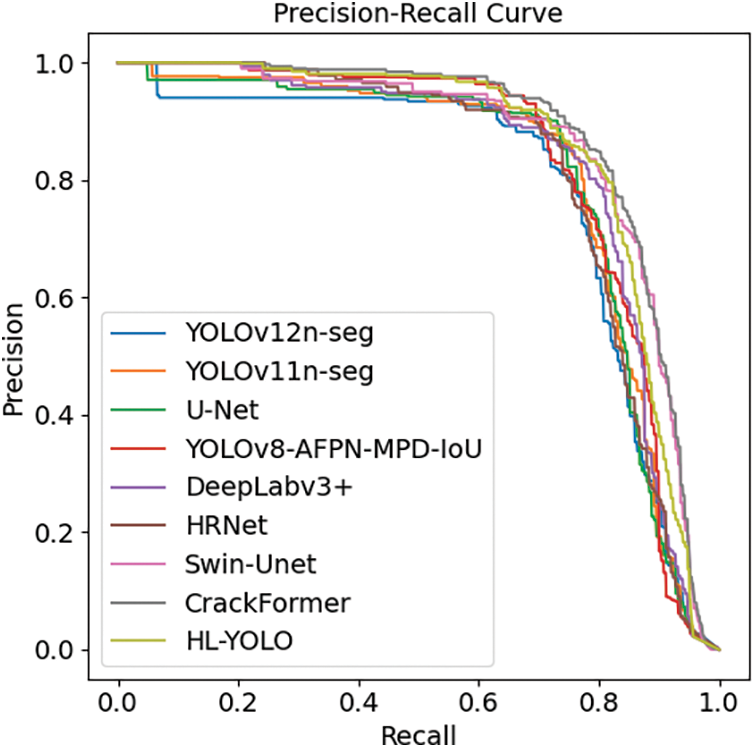

To objectively evaluate model performance, this paper plots and analyzes the precision-recall (P-R) curves of HL-YOLO and several comparison models. The area under the P-R curve serves as a reference metric for segmentation accuracy, with a larger area indicating higher accuracy. According to Fig. 8, CrackFormer’s curve lies nearest the top-right corner, indicating superior precision and recall. Swin-Unet ranks second, while HL-YOLO ranks third in terms of area under the curve (AUC), and its curve also demonstrates good stability. Considering the comparative results in Table 6 and Fig. 8, the proposed method effectively enhances the accuracy of concrete building surface crack segmentation while maintaining a balance with inference speed.

Figure 8: Precision-recall (P-R) curves

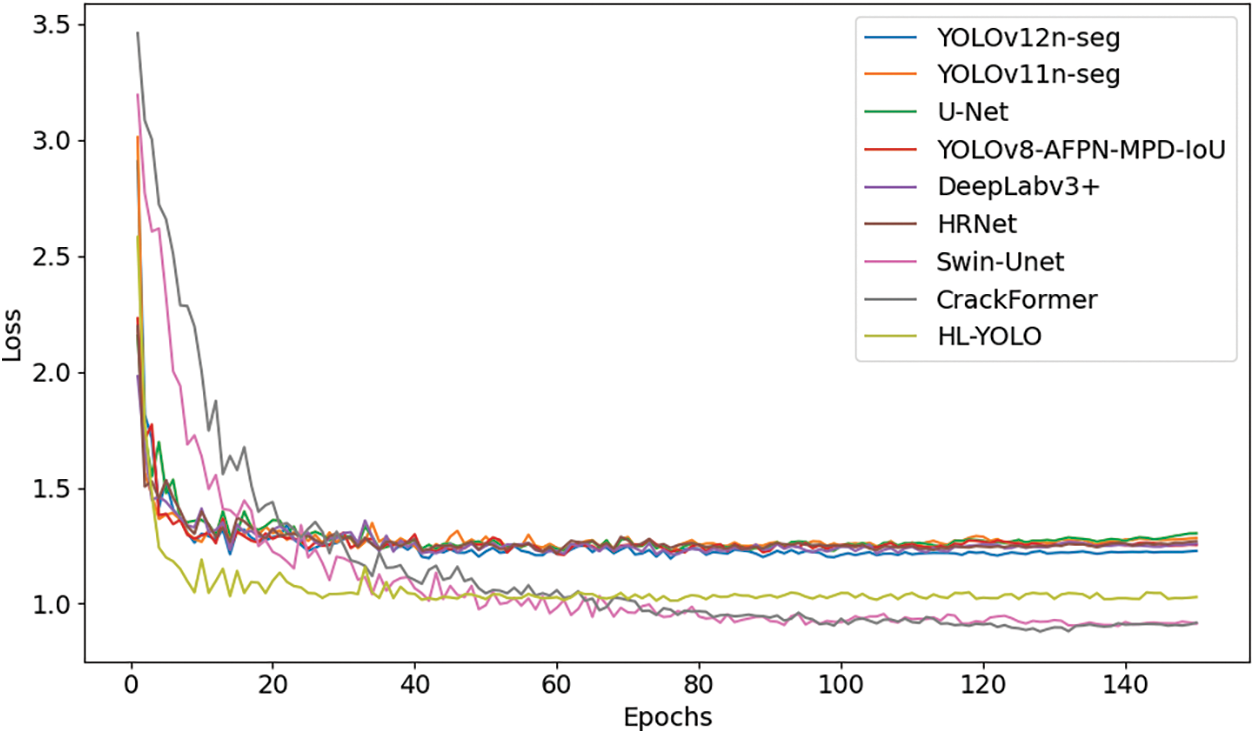

The loss values of different models during training are shown in Fig. 9. The experiments were set to run for a fixed 150 epochs, and the loss curve variations reflect the fluctuations of the models during training. Compared with the YOLO series, U-Net, and HRNet, HL-YOLO has a lower final loss, indicating that it has stronger feature fitting capabilities. Compared to Swin-Unet and CrackFormer, although HL-YOLO has a slightly higher minimum loss, it converges in fewer iterations, resulting in higher training efficiency. Overall, HL-YOLO balances segmentation accuracy and convergence efficiency, enabling its effective deployment in practical scenarios.

Figure 9: Loss curves during training process

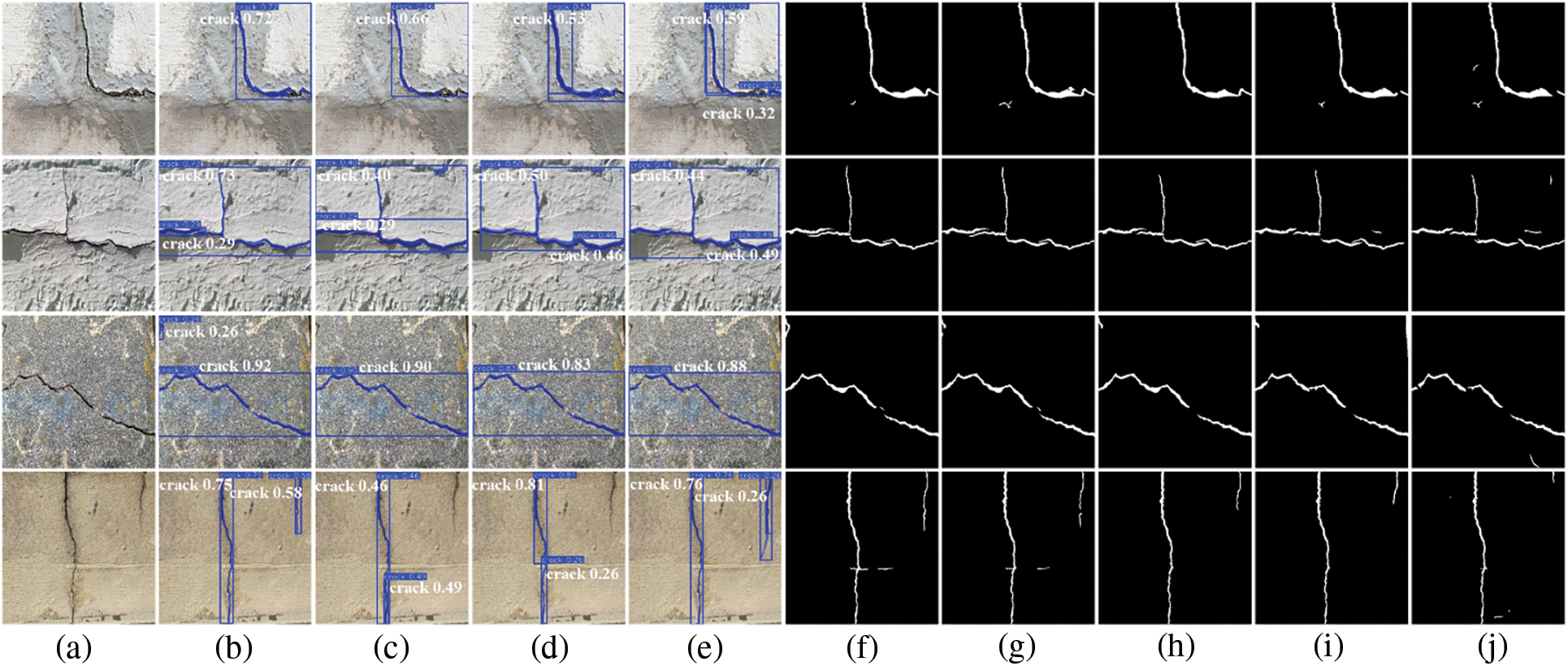

5.6 Visual Analysis of Crack Segmentation Results from Different Models

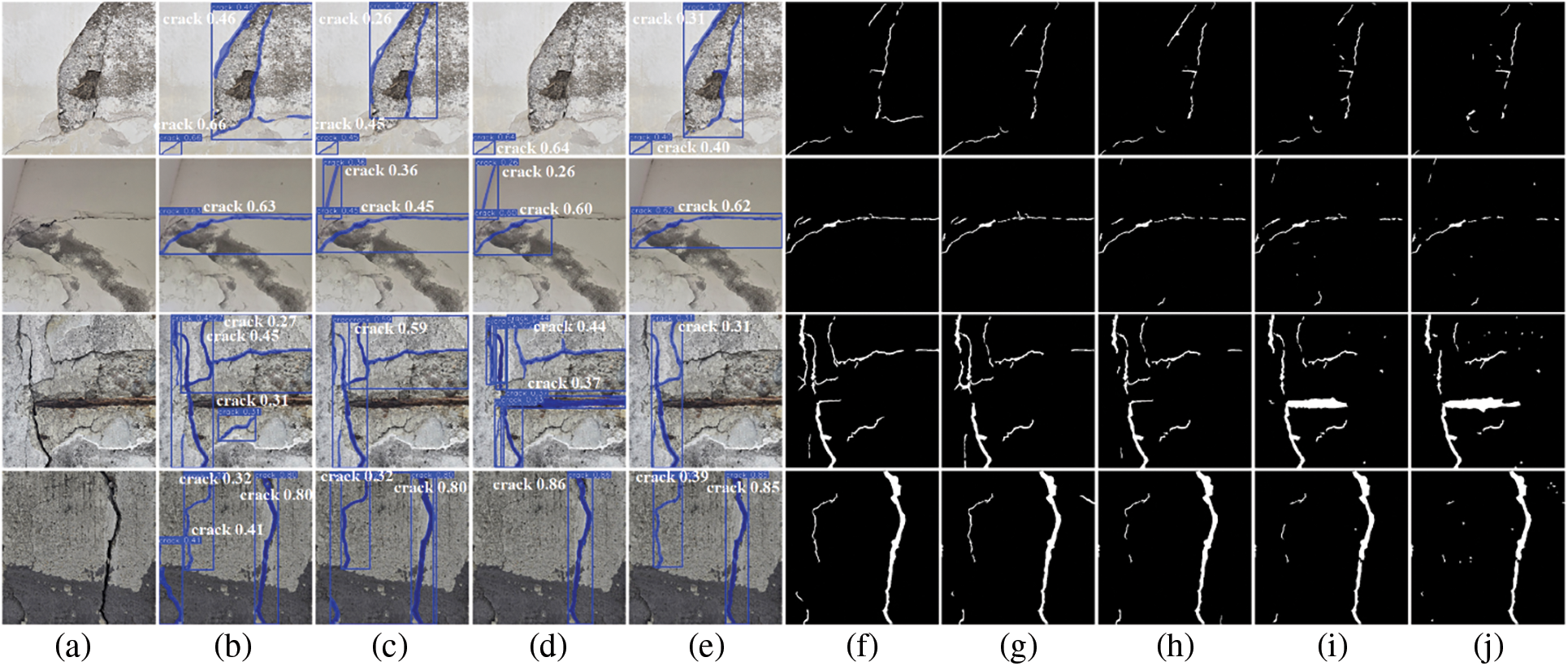

To intuitively compare the segmentation performance of different models in real-world environments, four representative crack images were selected from the self-built test set for evaluation. The results are presented in Fig. 10. The cracks in the first row are fine with blurred edges, and all models produce incomplete segmentation results. Only HL-YOLO, Swin-Unet, and CrackFormer are closest to the real crack morphology. CrackFormer achieves relatively complete detection in the fine crack areas, but suffers from blurred and sticky boundaries. YOLOv8-AFPN-MPD-IoU exhibits the most serious missed detection. The second row shows cracks located in the indoor corner. The wall putty layer falls off in a large area and mildew contamination is present. All models exhibit missed detections and segmentation discontinuities to varying degrees. Among them, YOLOv8-AFPN-MPD-IoU, YOLOv11n-seg, HRNet, Deep-Labv3+, and U-Net also have obvious false detections. The concrete in the crack area of the third row is damaged with exposed steel bars, and rust has caused noticeable discoloration. HL-YOLO, CrackFormer, and Swin-Unet successfully identify both major and small cracks. In contrast, the other models exhibit severe missed detections and segmentation discontinuities. Among them, YOLOv8-AFPN-MPD-IoU, DeepLabv3+, and U-Net have obvious misjudgments of the rusted area, while YOLOv12n-seg only detects the main body of the obvious crack. The crack image in the fourth row is clear, and all models can segment the main crack region. However, the segmentation results of HL-YOLO, CrackFormer, and Swin-Unet are clearer and more accurate, without discontinuities. Considering that the visualization results are primarily intuitive, the relevant segmentation accuracy metrics are summarized in Table 6 for a clear comparison of the overall performance of each model. Overall, our method effectively balances recognition quality and structural rationality under complex backgrounds and interference conditions. Its segmentation performance is visually comparable to that of CrackFormer and Swin-Unet, showing no significant differences. It demonstrates greater potential for edge deployment and practical engineering applications.

Figure 10: Visual comparison of different models’ segmentation results on the self-built test set. (a) Raw image, (b) HL-YOLO, (c) YOLOv8-AFPN-MPD-IoU, (d) YOLOv11n-seg, (e) YOLOv12n-seg, (f) CrackFormer, (g) Swin-Unet, (h) HRNet, (i) DeepLabv3+, (j) U-Net. The annotation text (e.g., “crack 0.86”) represents the model’s predicted category for the target and its confidence score

To evaluate the robustness of HL-YOLO, we selected a set of crack images containing interference noise, complex backgrounds, and fine branches from the Roboflow crack segmentation test set. Fig. 11 demonstrates that segmentation accuracy declines due to factors such as texture interference, material coverage and mottled surfaces. The crack in the first row is surrounded by evident repair traces and areas of material spalling. While all models can identify the primary crack structure, only HL-YOLO, CrackFormer, and Swin-Unet successfully detect the spalled regions. The remaining models exhibit missed detections in these areas, and DeepLabv3+ and U-Net even produce false detections. The crack surface in the second row exhibits mottling and uneven lighting, leading to missed detections across all models. Among them, DeepLabv3+ and U-Net are influenced by illumination variations and falsely detect shadows as cracks. The crack surface in the third row is rough, unevenly colored, and has blurred edges, causing all models to exhibit segmentation discontinuities. Moreover, YOLOv8-AFPN-MPD-IoU, YOLOv11n-seg, YOLOv12n-seg, and U-Net have missed detections at the edge of cracks. The cracks in the fourth row are narrow, with blurred edges and accompanied by diffuse stains. None of the models exhibit segmentation discontinuities. CrackFormer and Swin-Unet provide more complete and detailed segmentation at the end of the cracks, whereas YOLOv8-AFPN-MPD-IoU, YOLOv11n-seg, and U-Net only identify obvious cracks. YOLOv12n-seg has a relatively complete segmentation, but there are false detections at the end of the cracks. Overall, our method exhibits performance close to that of CrackFormer and Swin-Unet, while maintaining a small parameter count and fast inference speed, demonstrating good potential for practical applications.

Figure 11: Visual comparison of different models’ segmentation results on the Roboflow test set. (a) Raw image, (b) HL-YOLO, (c) YOLOv8-AFPN-MPD-IoU, (d) YOLOv11n-seg, (e) YOLOv12n-seg, (f) CrackFormer, (g) Swin-Unet, (h) HRNet, (i) DeepLabv3+, (j) U-Net

In this paper, we propose HL-YOLO, a model designed for crack segmentation on concrete building surfaces, based on the YOLOv11n-seg algorithm. The model adopts ResNet50 as the backbone and integrates the CSAA module after the C2PSA module. In the neck network, the original upsampling methods are replaced with the ProCARAFE modules, and the DWR module is introduced into the C2f feature extraction modules. These improvements enhance the model’s sensitivity to key crack features, particularly when handling small, blurred, and complex background cracks. Experimental results on the self-built dataset show that our method improves

Acknowledgement: The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support from the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province and the Hunan Yiduoyun Commodity Intelligence Project. We also sincerely thank the researchers whose prior work in deep learning has laid the foundation for this study.

Funding Statement: This financial support from Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (Grant No. 2024JJ8055), Hunan Yiduoyun Commodity Intelligence Project (Grant No. h2024-003).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Study conception and design: Mansheng Xiao; data collection: Yating Xu; analysis and interpretation of results: Yating Xu, Mengxing Gao, Zhenzhen Liu, Zeyu Xiao; draft manuscript preparation: Yating Xu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data and codes that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Duan S, Zhang M, Qiu S, Xiong J, Zhang H, Li C, et al. Tunnel lining crack detection model based on improved YOLOv5. Tunn Undergr Sp Technol. 2024;147(5):105713. doi:10.1016/j.tust.2024.105713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Su P, Han H, Liu M, Yang T, Liu S. MOD-YOLO: rethinking the YOLO architecture at the level of feature information and applying it to crack detection. Expert Syst Appl. 2024;237(3):121346. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2023.121346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Hu H, Li Z, He Z, Wang L, Cao S, Du W. Road surface crack detection method based on improved YOLOv5 and vehicle-mounted images. Measurement. 2024;229(6):114443. doi:10.1016/j.measurement.2024.114443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Bae H, An YK. Computer vision-based statistical crack quantification for concrete structures. Measurement. 2023;211(6):112632. doi:10.1016/j.measurement.2023.112632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Shang J, Xu J, Zhang AA, Liu Y, Wang KC, Ren D, et al. Automatic pixel-level pavement sealed crack detection using multi-fusion U-Net network. Measurement. 2023;208(3):112475. doi:10.1016/j.measurement.2023.112475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Fu H, Meng D, Li W, Wang Y. Bridge crack semantic segmentation based on improved Deeplabv3+. J Mar Sci Eng. 2021;9(6):671. doi:10.3390/jmse9060671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Li Y, Ma R, Liu H, Cheng G. Real-time high-resolution neural network with semantic guidance for crack segmentation. Autom Constr. 2023;156(12):105112. doi:10.1016/j.autcon.2023.105112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Yu H, Deng Y, Guo F. Real-time pavement surface crack detection based on lightweight semantic segmentation model. Transp Geotech. 2024;48(5):101335. doi:10.1016/j.trgeo.2024.101335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Li Y, Bao T, Huang X, Chen H, Xu B, Shu X, et al. Underwater crack pixel-wise identification and quantification for dams via lightweight semantic segmentation and transfer learning. Autom Constr. 2022;144(12):104600. doi:10.1016/j.autcon.2022.104600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Zhang Y, Liu J, Zhao Y, Xu J, Wu W. Crack detection on concrete composite slab using you only look once Version 8 based lightweight system. J Build Eng. 2025;108(10):112974. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2025.112974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Wang T, Zhang J, Chen W, Chun Q, Sun J. Pixel-level segmentation of spalling in masonry structures based on deep learning. Eng Struct. 2025;340(21):120686. doi:10.1016/j.engstruct.2025.120686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. He K, Zhang X, Ren S, Sun J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. p. 770–8. [Google Scholar]

13. Wang J, Chen K, Xu R, Liu Z, Loy CC, Lin D. Carafe: content-aware reassembly of features. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2019 Oct 27–Nov 2; Seoul, Republic of Korea. p. 3007–16. [Google Scholar]

14. Wang Q, Wu B, Zhu P, Li P, Zuo W, Hu Q. ECA-Net: efficient channel attention for deep convolutional neural networks. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2020 Jun 14–19; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 11534–42. [Google Scholar]

15. Wei H, Liu X, Xu S, Dai Z, Dai Y, Xu X. DWRSeg: rethinking efficient acquisition of multi-scale contextual information for real-time semantic segmentation. arXiv:2212.01173. 2022. [Google Scholar]

16. Yang CQ, Li S, Wang BK, Chen YJ, Hong W, Zhai F, et al. High anti-noise extraction and identification method for concrete cracks based on dynamic threshold. J Southeast Univ Nat Sci Ed. 2021;51(6):967–72. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1001-0505.2021.06.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Tan Z, Wang BX, Qin SP, Zhao WG. Crack damage detection method based on edge feature reinforcement learning. J Railw Sci Eng. 2023;20(8):3172–80. doi:10.19713/j.cnki.43-1423/u.T20221573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Ranjbar S, Nejad FM, Zakeri H. An image-based system for pavement crack evaluation using transfer learning and wavelet transform. Int J Pavement Res Technol. 2021;14(5):437–49. doi:10.1007/s42947-020-0098-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Hui L, Ibrahim A, Hindi R. Computer vision-based concrete crack identification using MobileNetV2 neural network and adaptive thresholding. Infrastructures. 2025;10(2):42. doi:10.3390/infrastructures10020042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Yang HL, Chen JJ, Pan Y. Automatic annotation and segmentation of dam concrete cracks in images based on Swin-Unet. J Hydroelectr Eng. 2024;43(12):23–33. doi:10.11660/slfdxb.20241203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Shao GZ, Du T. Detection of shallow underground fissures by time-frequency analysis of Rayleigh waves based on wavelet transform. Appl Geophys. 2020;17(2):233–42. doi:10.1007/s11770-020-0817-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Zhang Q, Chen S, Wu Y, Ji Z, Yan F, Huang S, et al. Improved U-net network asphalt pavement crack detection method. PLoS One. 2024;19(5):e0300679. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0300679. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Chen LC, Zhu Y, Papandreou G, Schroff F, Adam H. Encoder-decoder with atrous separable convolution for semantic image segmentation. In: Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV); 2018 Sep 8–14; Munich, Germany. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2018. p. 801–18. [Google Scholar]

24. Sun K, Zhao Y, Jiang B, Cheng T, Xiao B, Liu D, et al. High-resolution representations for labeling pixels and regions. arXiv:1904.04514. 2019. [Google Scholar]

25. Yuan J, Song X, Pu H, Zheng Z, Niu Z. Bridge crack segmentation method based on parallel attention mechanism and multi-scale features fusion. Comput Mater Contin. 2022;74(3):6485–503. doi:10.32604/cmc.2023.035165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Zhang Y, Fan J, Zhang M, Shi Z, Liu R, Guo B. A recurrent adaptive network: balanced learning for road crack segmentation with high-resolution images. Remote Sens. 2022;14(14):3275. doi:10.3390/rs14143275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Wang J, Zeng Z, Sharma PK, Alfarraj O, Tolba A, Zhang J, et al. Dual-path network combining CNN and transformer for pavement crack segmentation. Autom Constr. 2024;158(2):105217. doi:10.1016/j.autcon.2023.105217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Yu Z, Chen Q, Shen Y, Zhang Y. Robust pavement crack segmentation network based on transformer and dual-branch decoder. Constr Build Mater. 2024;453(44):139026. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.139026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Zhang Z, He Y, Hu D, Jin Q, Zhou M, Liu Z, et al. Algorithm for pixel-level concrete pavement crack segmentation based on an improved U-Net model. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):6553. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-91352-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Wu Y, Han Q, Jin Q, Li J, Zhang Y. LCA-YOLOv8-Seg: an improved lightweight YOLOv8-Seg for real-time pixel-level crack detection of dams and bridges. Appl Sci. 2023;13(19):10583. doi:10.3390/app131910583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Ye G, Li S, Zhou M, Mao Y, Qu J, Shi T, et al. Pavement crack instance segmentation using YOLOv7-WMF with connected feature fusion. Autom Constr. 2024;160(4):105331. doi:10.1016/j.autcon.2024.105331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Zhang J, Qian S, Tan C. Automated bridge surface crack detection and segmentation using computer vision-based deep learning model. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2022;115(9):105225. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2022.105225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Xiong C, Zayed T, Jiang X, Alfalah G, Abelkader EM. A novel model for instance segmentation and quantification of bridge surface cracks—the YOLOv8-AFPN-MPD-IoU. Sensors. 2024;24(13):4288. doi:10.3390/s24134288. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Yang G, Qi Y, Du Y, Shi X. Improved YOLOv7 and SeaFormer bridge cracks identification and measurement. J Railw Sci Eng. 2025;22(1):429–42. doi:10.19713/j.cnki.43-1423/u.T20240458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Xu J, Wang S, Han R, Wu X, Zhao D, Zeng X, et al. Crack segmentation and quantification in concrete structures using a lightweight YOLO model based on pruning and knowledge distillation. Expert Syst Appl. 2025;283(25):127834. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2025.127834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Yao Z, Li Y, Fu H, Tian J, Zhou Y, Chin CL, et al. Research on concrete crack and depression detection method based on multi-level defect fusion segmentation network. Buildings. 2025;15(10):1657. doi:10.3390/buildings15101657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Yang K, Bao Y, Li J, Fan T, Tang C. Deep learning-based YOLO for crack segmentation and measurement in metro tunnels. Autom Constr. 2024;168(12):105818. doi:10.1016/j.autcon.2024.105818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Khanam R, Hussain M. Yolov11: an overview of the key architectural enhancements. arXiv:2410.17725. 2024. [Google Scholar]

39. Tan GJ, Ou J, Ai YM, Yang RC. Bridge crack image segmentation method based on improved DeepLabv3+ model. J Jilin Univ. 2022;52(1):1–7. doi:10.13229/j.cnki.jdxbgxb.20220205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Wang WB, Wang XT, Chen X. Detection and width measurement of concrete apparent cracks based on computer vision. Earthq Eng Struct Dyn. 2024;44(3):41–51. doi:10.13197/j.eeed.2024.0304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Tao J, Tian L, Zhang DJ, Hu CX, He L. Asphalt pavement crack detection method based on local texture features. Comput Eng Des. 2022;43(2):517–24. doi:10.16208/j.issn1000-7024.2022.02.030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Chen S, Feng Z, Xiao G, Chen X, Gao C, Zhao M, et al. Pavement crack detection based on the improved Swin-Unet model. Buildings. 2024;14(5):1442. doi:10.3390/buildings14051442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Liu H, Miao X, Mertz C, Xu C, Kong H. Crackformer: transformer network for fine-grained crack detection. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision; 2021 Oct 10–17; Montreal, BC, Canada. p. 3783–92. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools