Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Review of the Mechanical Performance Prediction of Concrete Based on Artificial Neural Networks

1 School of Civil Engineering, NingboTech University, Ningbo, 315100, China

2 School of Civil Engineering, Chongqing Jiaotong University, Chongqing, 400074, China

3 School of Mechanical and Automotive Engineering, Anhui Water Conservancy Technical College, Hefei, 231603, China

4 Zhejiang Provincial Erjian Construction Group Ltd., Ningbo, 315202, China

* Corresponding Author: Xiaopeng Yu. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Sustainable Concrete Technologies: SCMs, Circular Economy, and AI Integration)

Structural Durability & Health Monitoring 2025, 19(6), 1507-1527. https://doi.org/10.32604/sdhm.2025.069021

Received 12 June 2025; Accepted 15 August 2025; Issue published 17 November 2025

Abstract

The performance of concrete can be affected by many factors, including the material composition, environmental conditions, and construction methods, and it is challenging to predict the performance evolution accurately. The rise of artificial intelligence provides a way to meet the above challenges. This article elaborates on research overview of artificial neural network (ANN) and its prediction for concrete strength, deformation, and durability. The focus is on the comparative analysis of the prediction accuracy for different types of neural networks. Numerous studies have shown that the prediction accuracy of ANN can meet the standards of the practical engineering applications. To further improve the applicability of ANN in concrete, the model can consider the combination of multiple algorithms and the expansion of data samples. The review can provide new research ideas for development of concrete performance prediction.Keywords

Concrete widely used in construction fields can affect the engineering quality. The core of the concrete quality evaluation system is to test the strength, durability and deformation of concrete. The traditional testing methods mainly follow standard procedures to prepare common specimens, and after curing under common or natural conditions to the corresponding age, relevant indicators are tested. This consumes too much energy, time, human resources, and material resources, and the work efficiency is not high, resulting in no guarantee of the final performance indicators. In recent years, machine learning (ML) has been widely applied to predict concrete performance to solve this problem. Kumar et al. [1] reviewed the application of artificial intelligence (AI) in high-performance concrete and ultrahigh-performance concrete to predict the mechanical performance. Genetic programming (GP) was applied for prediction the compressive strength of concrete confined by the fiber-reinforced polymer (FRP), and R2 value showed that GP prediction is more accurate than existing models [2]. Singh et al. [3] predicted concrete strength using random forest (RF). Standalone RF, RF improved by the flying foxes optimization (RFFO), and RF improved by the improved grey wolf optimizer (RFIG) were used for the compressive strength prediction of recycled aggregate concrete, and research indicated that RFFO is superior to other models [4]. Rao et al. [5] used support vector machine (SVM) and RF to predict the compressive strength of fly ash geopolymer concrete, and the results showed that the accuracy of both models is acceptable. For concrete reinforced by the polyethylene terephthalate (PET) fiber, Parhi and Patro [6] used RF, gradient boosting machine (GBM) and decision tree (DT) for the prediction of compressive strength, and research indicated that RF improved by dolphin echolocation optimization (DEO) is superior to other models. This paper reviews the application of artificial neural network (ANN) to the performance prediction of concrete.

ANN, with its nonlinear solid mapping ability and adaptive learning characteristics, is suitable for the application in concrete, providing strong support for research on the performance prediction of concrete. The diversity, fault tolerance, and memory connectivity of ANN enable them to better self-learning and self-improvement when facing multiple input and output variables to complete complex causal relationships between variables. Gupta et al. [7] used ANN to quickly predict the mechanical performance of rubber concrete, filling the gaps in this field. Chopra et al. [8] used a genetic algorithm (GA) to optimize ANN to predict concrete strength. Torre et al. [9] used ANN for the compressive strength prediction of high-performance concrete. For self-compacting recycled coarse aggregate concrete, Jagadesh et al. [10] used ANN to predict compressive strength. Compared with the experimental results, ANN is valid. Moodi et al. [11] used ANN, RF, SVM, relevance vector machine (RVM), long short-term memory (LSTM), and Gaussian process regression (GPR), optimized by marine predators algorithm (MPA), for the compressive strength of concrete with copper slag aggregates. Research indicated that RVM-MPA has the highest prediction accuracy. For the uniaxial compressive strength prediction of concrete, Hamed et al. [12] proposed a stacked model integrating RF, ANN, and extreme gradient boosting (EGB) with linear regression. Therefore, the application of ANN to concrete has long been widely valued by scholars and engineers, and the research industry on it has reached a new climax globally, promoting the rapid development of the civil engineering industry.

Traditionally, the empirical or semi-empirical physical models have been widely used in the field of concrete performance prediction. To save testing resources, improve work efficiency, and facilitate quality control, ANN should be widely applied in the field of concrete performance prediction. To facilitate the scholars’ application of ANN in the field of concrete performance prediction, this paper reviews the feasibility, research status, key points, and development trends of ANN for predicting the concrete strength, deformation, and durability. The key points mainly include the model selection based on application scenarios, obstacles in practical engineering applications, selection of input data, data preprocessing, and error evaluation. The development trends include the development of datasets with diversity and a large number of samples, the use of hybrid models, and the development of systems facilitating model interpretation.

2 Overview of the Development and the Application of the Artificial Neural Networks

ANN is a model that processes information and makes predictions. This model type can organize data, anticipate values, and assist decision-making. Compared with the traditional numerical analysis programs (such as regression analysis), the trained neural networks can obtain more reliable results, significantly reducing the computational workload [13].

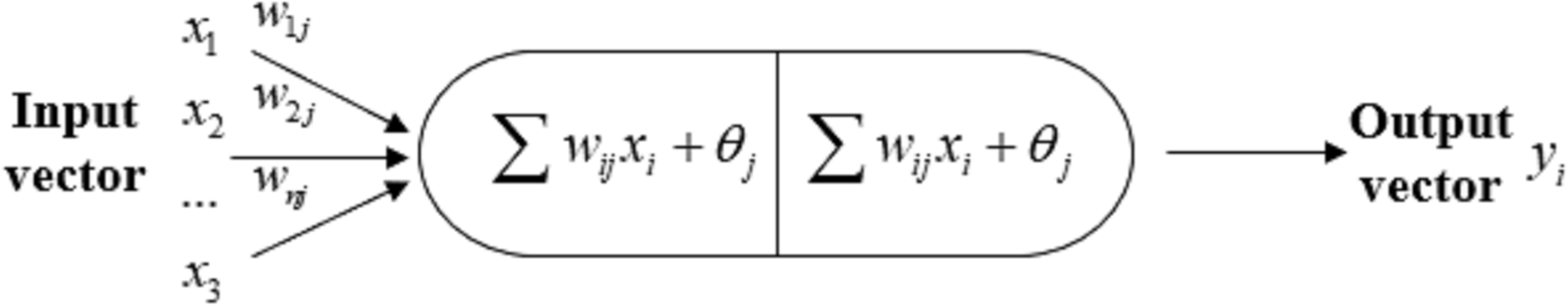

The working mode of ANN is from the human brain. As shown in Fig. 1, the artificial neurons are a fundamental component of the neural networks and a mathematical model attempting to simulate the behavior of biological neurons [14–16]. It inherits specific biology and unique characteristics, such as large-scale parallel processing, robust fault tolerance, and self-learning function.

Figure 1: Artificial neuron model (Reprinted with permission from Reference [16], Copyright 2015, Nature)

The development of the neural networks has a long history. In the 1940s, during the period of the neural network enlightenment, M-P model was developed by McCulloch and Pitts, having a simple structure but a significant significance during this period, to initiate ANN research [17]. In 1949, Hebb [18] published “The Organization of Behavior”, laying the foundation for ANN with learning capabilities and having a significant breakthrough in the neural network technology and methods.

In 1982, Hopfield [19,20] developed a discrete ANN, which provided theoretical guidance for constructing and learning ANN and significantly promoted the development of ANN. In 1985, Powell presented radial basis function (RBF) [21]. In 1986, a group of scientists led by Rumelhart proposed a multi-layer feedforward neural network, which solved the learning problem of the multi-layer feedforward neural networks and proved that the multi-layer neural networks have strong learning ability [22]. Then the multi-layer feedforward neural network was further investigated [23,24]. In 1988, Broomhead and Lowe first incorporated the local response characteristics of the biological neurons into the neural networks and proposed RBF neural networks [25]. And it had also been researched by other scientists [26,27].

Since its development, in 2006, the concept of deep learning (DL) was proposed by Hinton [28]. DL essentially involves constructing the models with multiple hidden layers, training through large-scale data to obtain more representative feature information. DL breaks the limitations of traditional ANN on the layer number, allowing designers to choose the number of network layers according to their needs [28–30]. According to references [28–30], the advantages of DL are discussed. Before of DL, the hidden layer had no more than three layers. Compared with traditional ANN, DL avoids gradient vanishing, and the effective machine learning can perform. DL does not require manual design of features, reducing human intervention and saving time. ANN is difficult to adapt to big data, while DL can improve the model performance with big data. Compared with ANN, DL can be applied to multi-modal scenarios.

Due to its advantages, neural networks have been applied in various fields, such as stock prediction, weather forecasting, disease diagnosis, spectral analysis, biological experiment optimization, the machine maintenance period optimization, process control, quality control, etc. In civil engineering, ANN has been applied to process the problems in construction [31,32]. Adeli [33,34] used ANN for the structural control for the first time and conducted the structural control and the identification simulations for the large-span spatial structures and advanced space technology research experiments using back propagation (BP) and RBF. Zhang et al. [35] reviewed these studies. Therefore, ANNs have been applied in various fields. This article reviews the different applications of ANN in concrete.

3 Strength Prediction of the Concrete Based on the Artificial Neural Networks

3.1 Prediction of the Compressive Strength

3.1.1 BP Artificial Neural Network

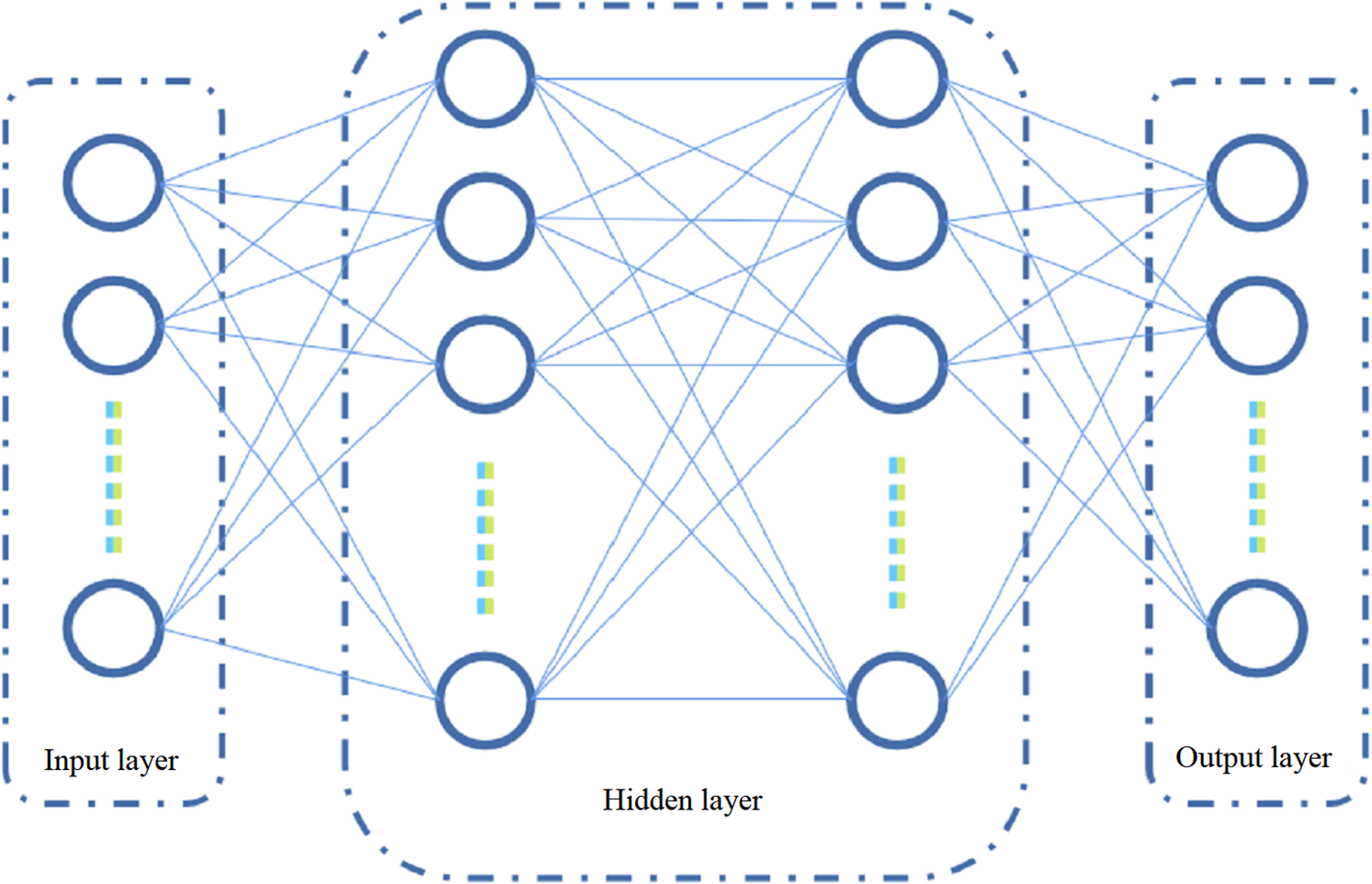

In concrete strength prediction, a feedforward neural network called BP is often used, which belongs to a supervised classification algorithm. It integrates prior knowledge into network learning, maximizes its utilization, has good adaptability, and can achieve considerable accuracy in situations with small categories. Its main components include an input layer, a hidden layer, and an output layer, as shown in Fig. 2. The selection of BP weights and thresholds is repeatedly adjusted and trained through a backpropagation algorithm.

Figure 2: Topological structure of BP neural network

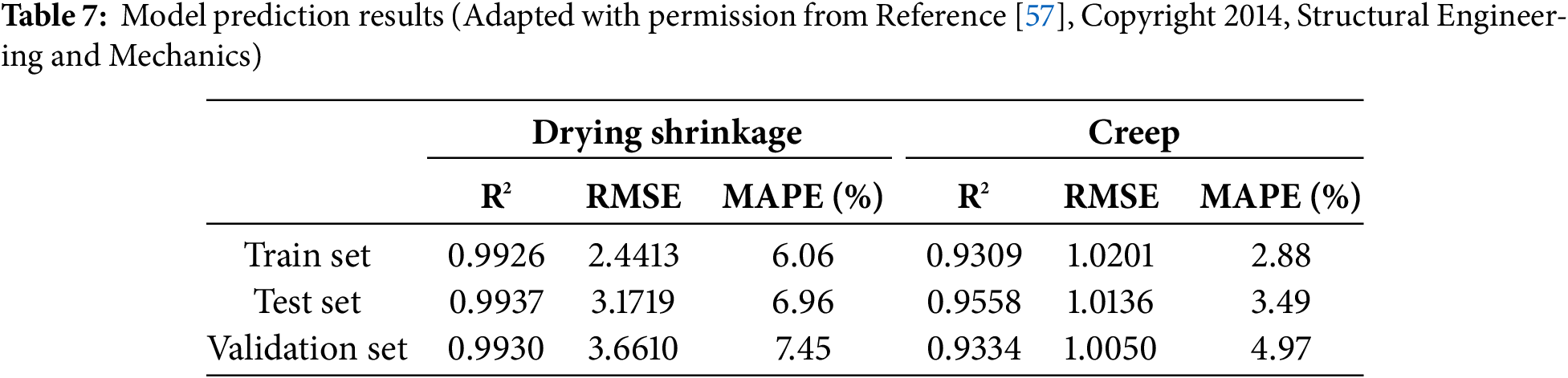

In civil engineering, concrete compressive strength is considered as the main factor in concrete design and analysis [36]. In Table 1, a detailed review applying BP for concrete strength prediction is described, and the used methods and their application performance are discussed.

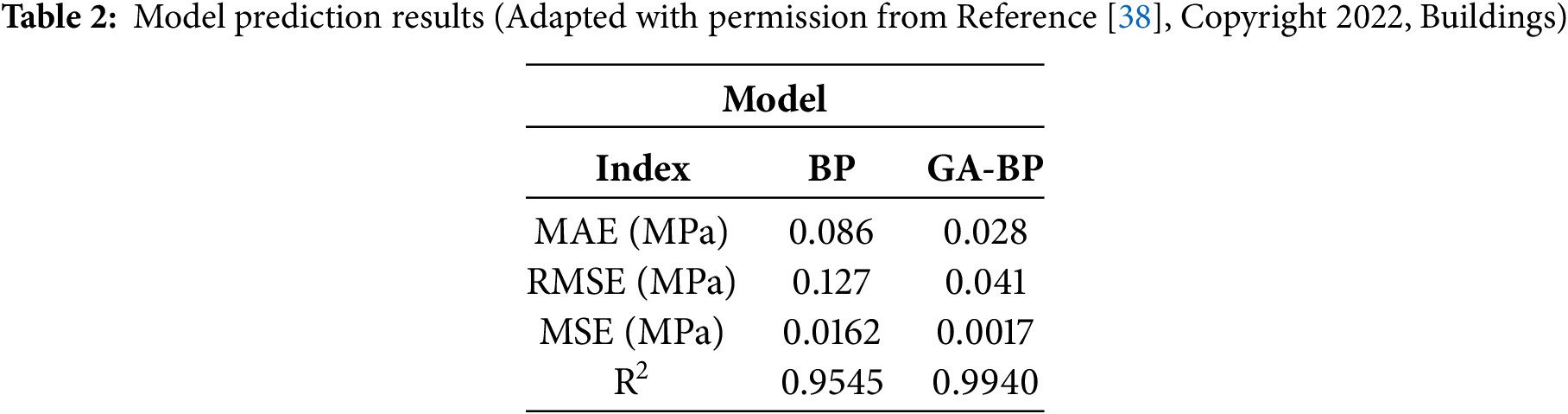

According to Kashyzadeh et al.’s paper [38], although BP is mature in theory, the prediction accuracy of the combined model is better than that of a single model, as shown in Table 2. The combination of algorithms can optimize the problem of BP falling into local minimum to a certain extent, improve its generalization ability, and make it more accurate, smaller error range, and better accuracy when predicting the concrete strength. There is yet to be a fundamental solution to the problem of BP falling into a local minimum. More complete and high-quality data are needed to expand the database, apply more factors related to concrete compressive strength, and improve the model’s generalization ability to establish a more accurate prediction model.

3.1.2 RBF Artificial Neural Network

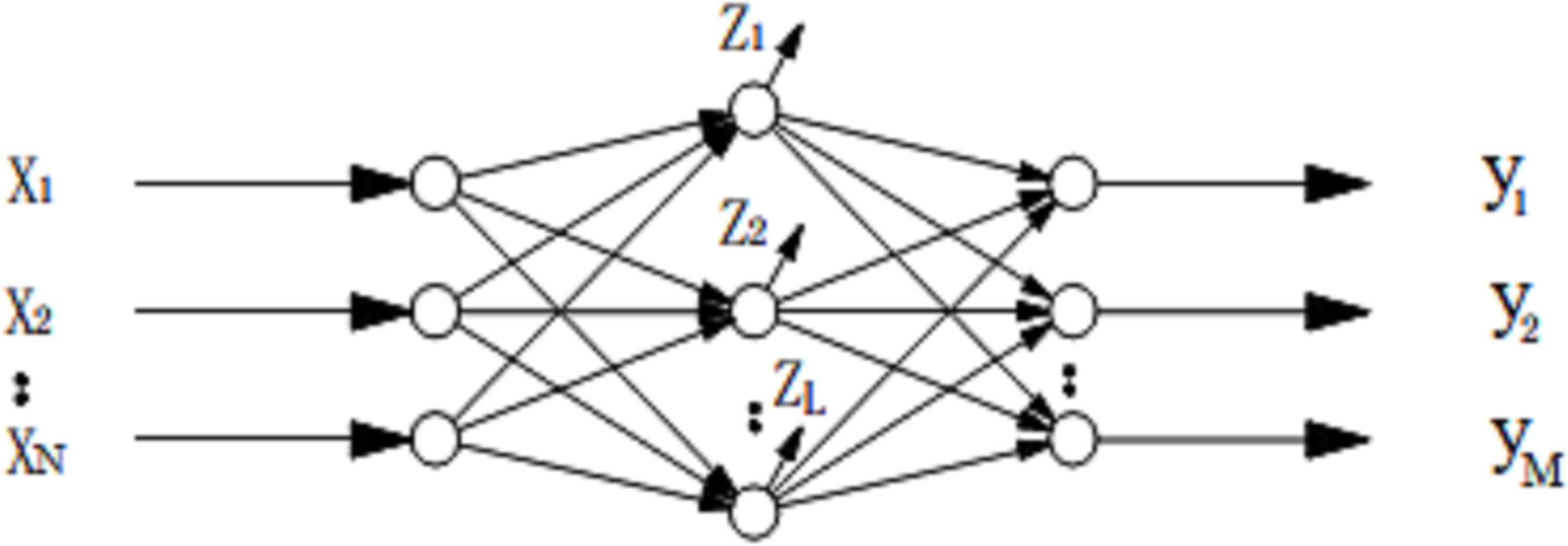

RBF ANN extends or preprocesses input vectors to a high-dimensional space. It is composed of three layers, and its structure is very similar to a multi-layer perceptron. The input layer nodes pass the input signal to the hidden layer, which consists of radial functions like Gaussian kernels, while the output layer nodes are usually simple linear functions. The topology of RBF ANN is shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Topological structure of RBF neural network (Reprinted with permission from Reference [45], Copyright 2005, Computer Engineering)

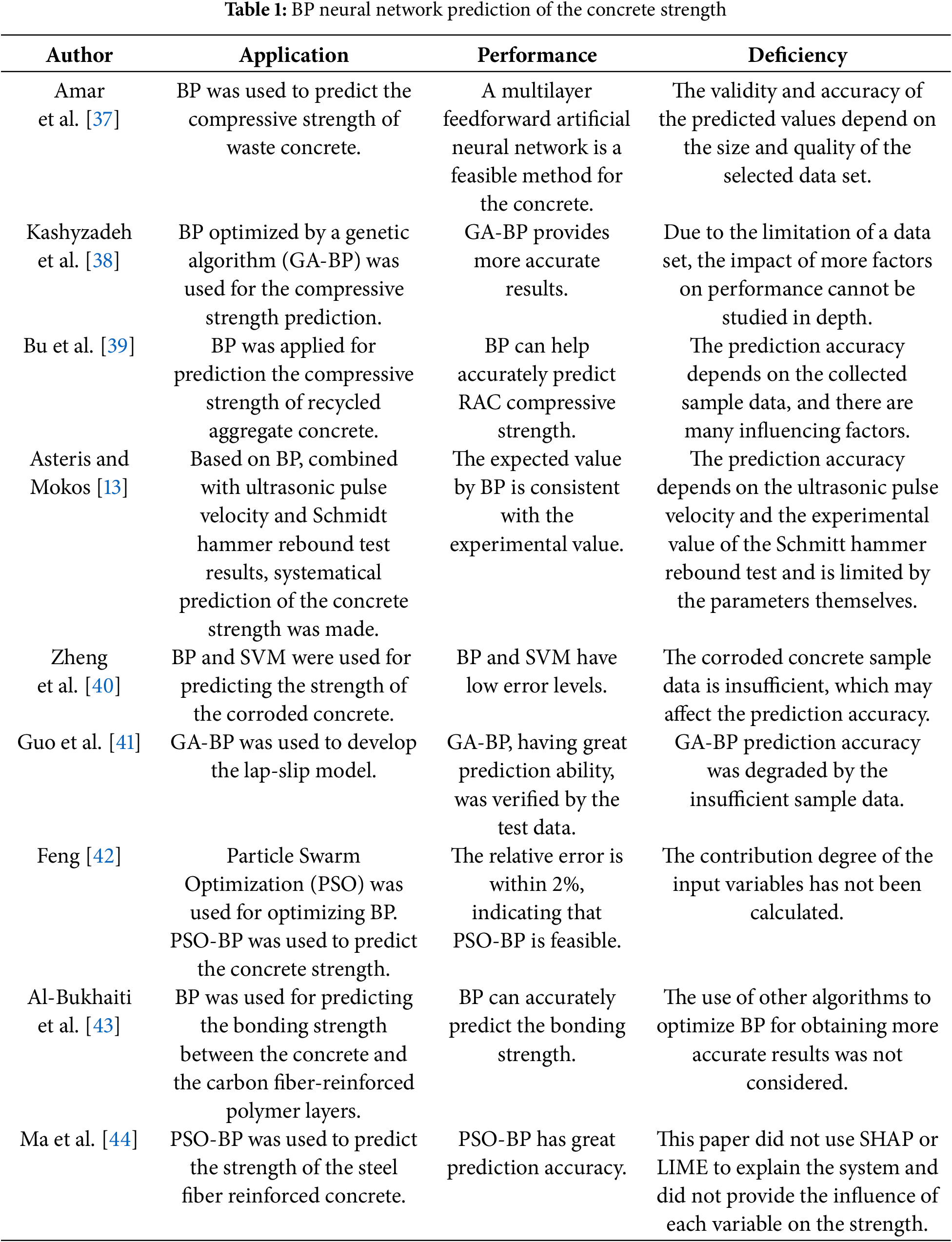

Both RBF and BP neural networks are feed-forward neural networks which are often compared and analyzed in concrete strength prediction. Wu [46] established RBF to predict the 28-day compressive strength of concrete and proposed that RBF is superior to the previous BP in the paper. Three hidden-layer neurons were used in both models. The root mean square error pairs (RMSE) are given in Table 3.

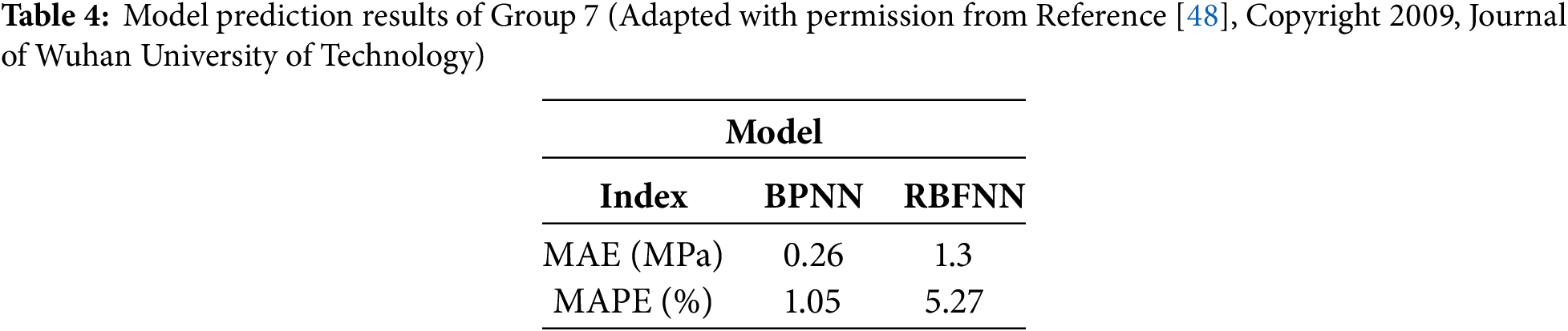

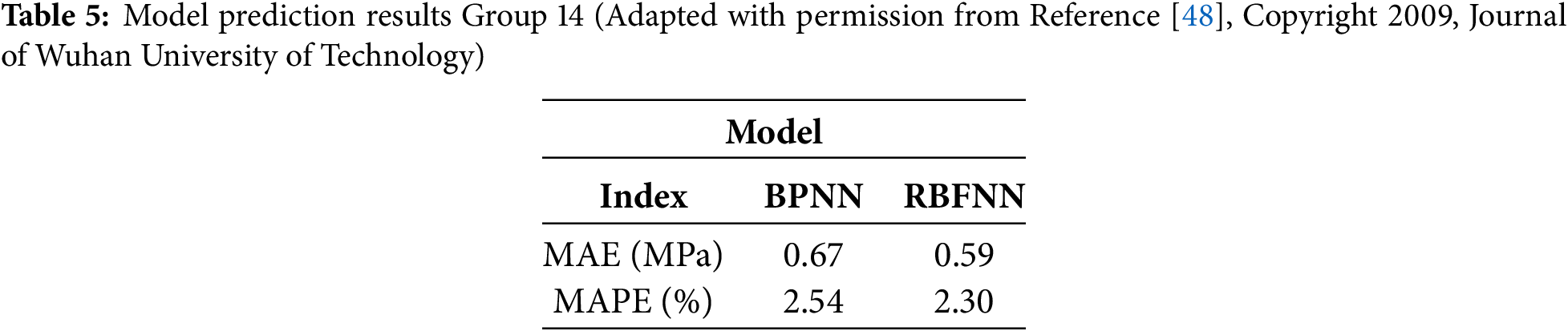

In the paper, Li and Peng [48] proposed using BP and RBF neural networks to simulate the relationship between concrete compressive strength and factors such as mixer type. Due to the limited data, the predicted and measured results are similar, but the performance difference between the two can also be seen. The anticipated results are shown in Tables 4 and 5.

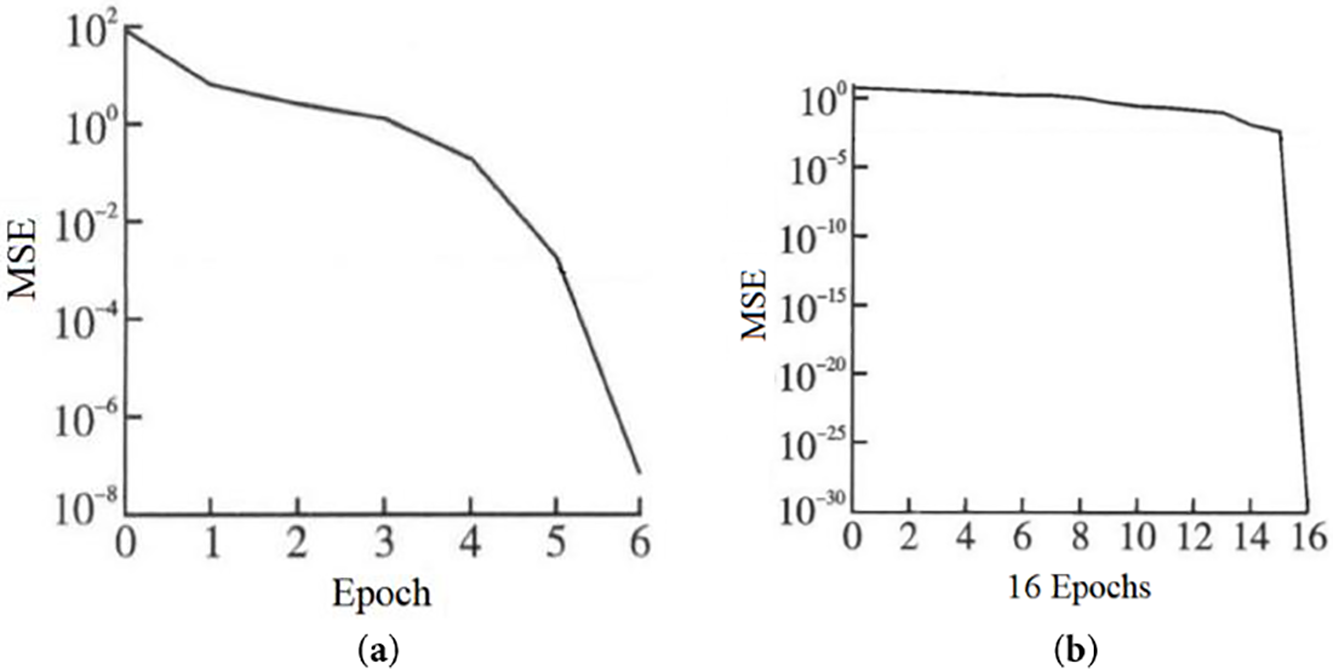

In this paper, both BP and RBF neural networks are three-layer networks, and the errors in their network training process are shown in Fig. 4. The training accuracy of both is relatively high. RBF converges faster and can avoid falling into local minima to some extent. However, as a neural network with a relatively perfect theory, BP may fall into local minima. It can be combined with different algorithms to make up for its shortcomings. Both can be used to predict the compressive strength of concrete, but they also face the problem of relying on the number of samples. If they are used in practical engineering problems in the future, what needs to be solved urgently is how to improve the accuracy and generalization performance by adding samples for learning.

Figure 4: Error curve: (a) BP neural network training process error; (b) RBF neural network training process error (Reprinted with permission from Reference [48], Copyright 2009, Journal of Wuhan University of Technology)

To sum up, BP and RBF can predict concrete strength when meeting the standards. BP, easily falling into the local optima, can be optimized to a certain extent and its performance can be improved through the combination of algorithms. Because its structure differs from BP, RBF can approximate the required function with arbitrary accuracy. As the most typical and widely used model, BP is still one of the best choices for predicting concrete strength because of its complete theoretical basis and more and more combination with various algorithms.

4 Deformation Prediction of the Concrete Based on the Artificial Neural Networks

With the increase of modern buildings and volume, concrete cracks also increase. Cracking caused by shrinkage deformation gradually becomes one of the main reasons affecting the concrete durability. Due to the glue’s hydration and heat release, many pores will be produced. Due to the existence of these pores, the water in concrete has a channel for the loss of water, and the loss of adsorptive water in its internal holes and gel holes can produce irreversible shrinkage.

The factors affecting the drying shrinkage of concrete include water-cement ratio, hydration degree, cement composition, cement dosage, mineral admixture, admixture, aggregate variety and dosage, specimen size, ambient temperature, humidity, etc. Therefore, ANN can automatically acquire the laws of drying shrinkage through self-learning to form the required model to predict its deformation. The established network can train the information in different states one by one to obtain the balanced convergence weight and threshold, reflecting the mapping relationship between input and output, and better solving the problem of multiple factors affecting drying shrinkage.

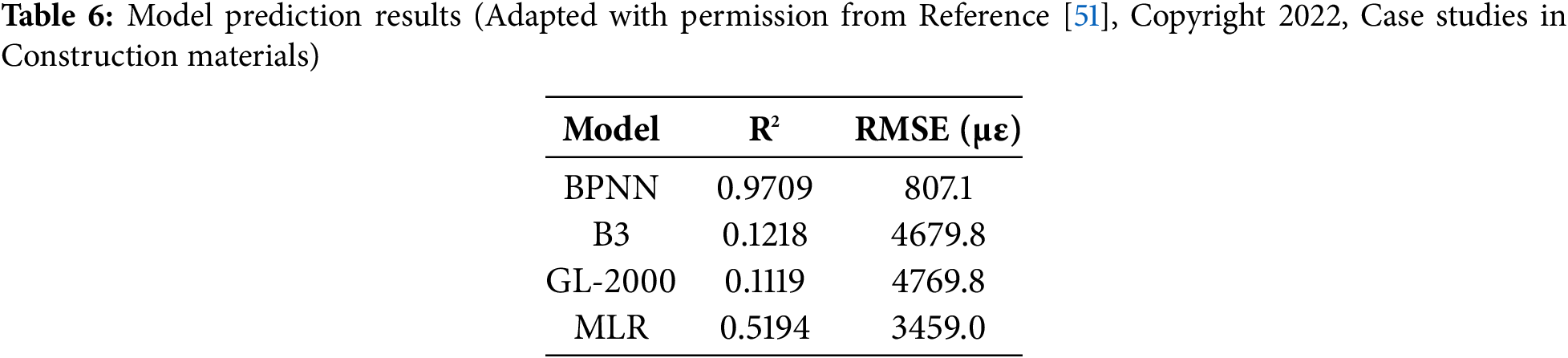

Liu [49] established a BP neural network model with seven major factors, including age, environmental humidity, temperature, fly ash content, mineral powder content, expander, and fiber content, as input variables and concrete shrinkage strain as output variables, aiming at the cracking problem of ultra-long concrete wellhead channel, and successfully trained the test data. BP can effectively predict concrete shrinkage strain and can meet the practical engineering requirements. Garoosiha et al. [50] established a shrinkage rate prediction model using the existing database and ANN. The results showed that this technology can predict the shrinkage strain well and is widely applicable to all kinds of concrete. Kong and Kurumisawa [51] used BP for prediction the drying shrinkage of alkali-activated materials and the results were compared with three commonly used drying shrinkage models. As shown in Table 6, although the R2 value of BP is higher than other models, its RMSE value is much lower than other models, indicating that ANN has better performance.

4.2 Creep Performance Prediction

Nowadays, different theories are used for factual creep analysis. Bažant et al. [52] believed that tangible creep results from shear slip between pores relative to walls, while Vandamme [53] proposed that creep is due to local micro-relaxation of concrete. Due to the different concrete environments, such as temperature, humidity, load, water-binder ratio, and cement type, it is necessary to establish a model that can accurately predict the creep to control the damage to the structure.

Taha et al. [54] used an ANN for predicting the creep of masonry structures to distinguish it from the traditional mathematical creep model. Zhu and Wang [55] used a convolutional neural network (CNN) to build concrete shrinkage and creep models, providing a reliable method for rapid prediction in practical engineering applications and long-term structural deformation simulation analysis. Al-Rihimy et al. [56] established an ANN model using SPSS to estimate the creep of self-compacting concrete mixtures produced by different types of Portland cement. The predicted results were compared with those recommended by ACI Committee 209, indicating that ANN is highly reliable.

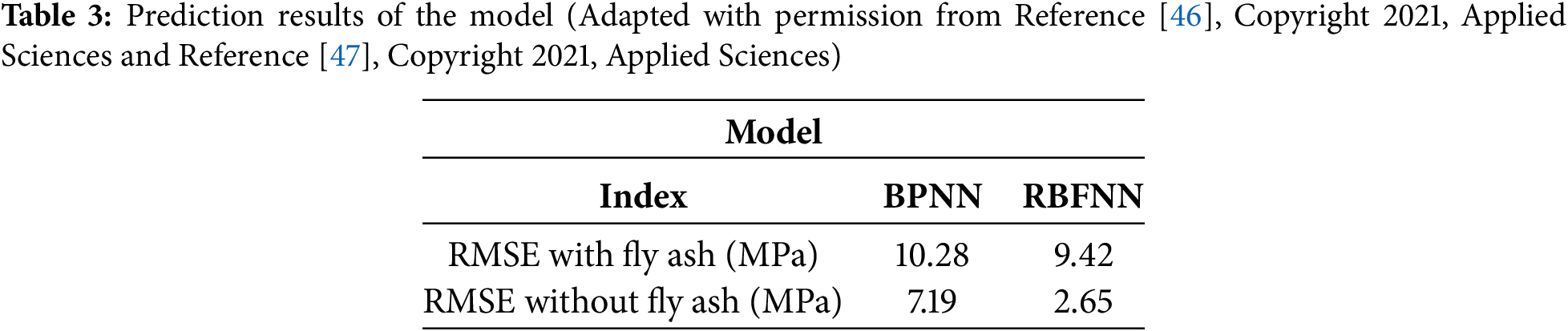

Gedam et al. [57] established an ANN model for predicting high-performance concrete’s dry shrinkage and creep using experimental data from other literature. The performance evaluation of the model is given in Table 7. The error indexes indicate that the model has high precision in forecasting and has a particular guiding value for practical engineering.

Research on concrete deformation using ANN could be better. Filling the research gap and optimizing concrete mix design have become the most crucial problems. Traditional shrinkage and creep prediction models and theoretical studies have substantially limited the sustainable development of this field. ANN is used for optimizing the conventional method so that it is more suitable to reveal the inherent law of the concrete shrinkage and creep and predict the concrete shrinkage and creep more accurately.

5 Durability Prediction of the Concrete Based on the Artificial Neural Networks

5.1 Prediction of Frost Resistance

The freeze-thaw damage of concrete is one of the leading causes of the aging disease of concrete structures in China. Because the northeast of China is located at a high latitude, freeze-thaw damage to hydraulic concrete is severe. Therefore, more attention has been paid to the research on the freeze-thaw damage mechanism and the prediction of the freeze-thaw resistance of concrete in these areas. As a multi-factor problem, the nonlinear mapping ability of ANN and its adaptive learning feature can be used to predict concrete’s frost resistance and durability.

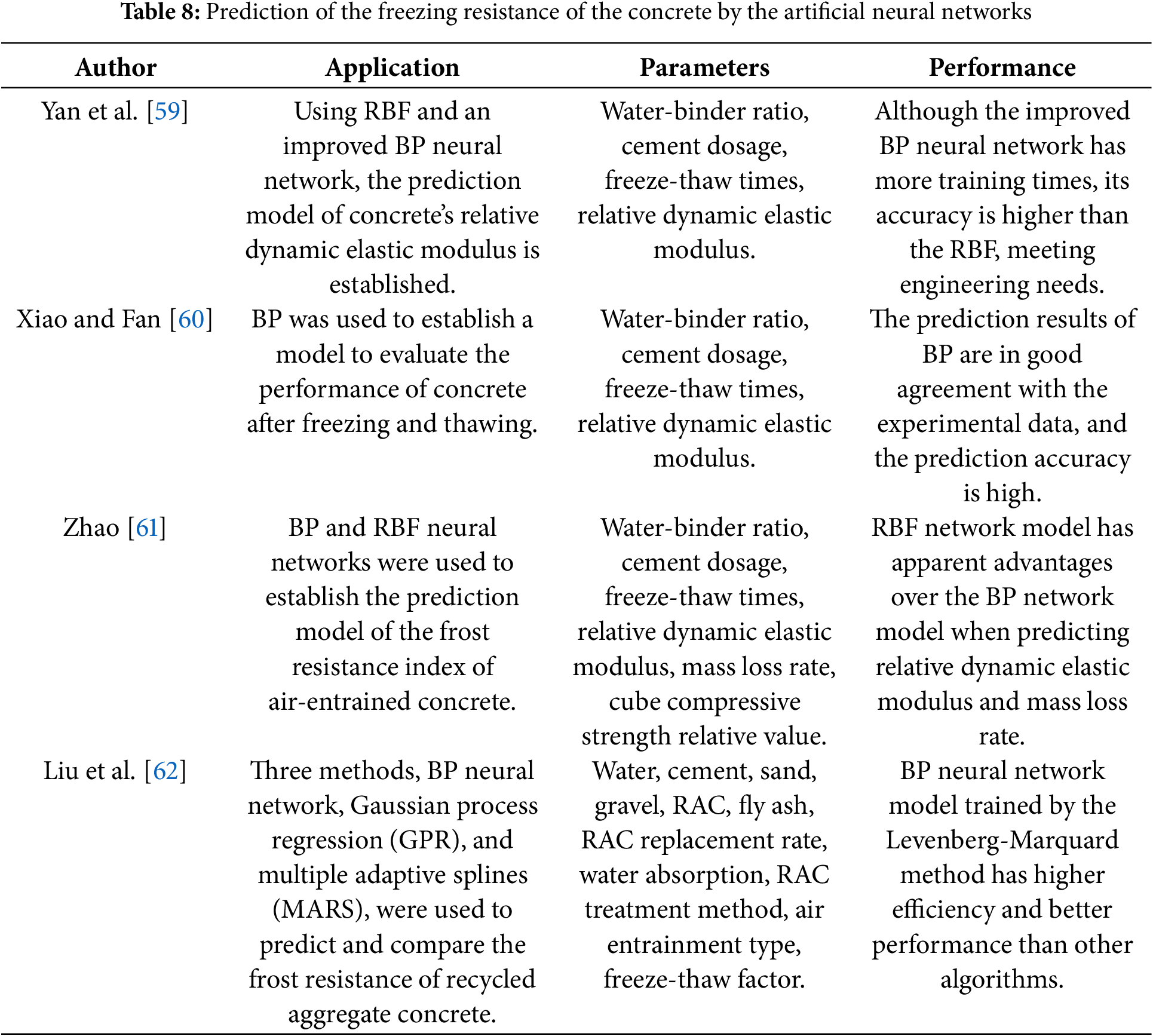

Zhao and Zhang [58] selected BP and RBF to establish a model for predicting the frost resistance of concrete under a freeze-thaw environment. The comparative analysis of the prediction results showed that ANN has strong practicability and can meet the requirements for predicting frost resistance. Meanwhile, the results obtained by the two neural networks were compared. BP prediction accuracy is better than that of RBF. Yan et al. [59] also used BP and RBF to predict the antifreeze performance of the concrete. The comparative analysis of the prediction results showed that both models can be used to predict the antifreeze performance of concrete. From the perspective of error, BP is better than RBF. However, from the perspective of learning, RBF has fewer training times and faster speed.

ANN is applied to establish the prediction model. The used methods and their performances are discussed in Table 8.

Using ANN to predict the frost resistance of concrete also depends on the number of samples. Increasing the number of pieces can improve neural network’s learning ability to a certain extent. As shown in the above table, BP is slightly better than RBF and other algorithms in predicting the frost resistance of concrete. From a modeling perspective, there is little difference in the training time between the two types of networks. For a small number of input samples, RBF is fast in training but occupies a large amount of computer memory. In terms of parameter selection, RBF is relatively simple. However, BP prediction accuracy is high. Nevertheless, the prediction error is discrete, while the prediction error curve of RBF is smooth, but the generalization ability is not strong. Therefore, if the network structure does not change, the measured data can be continuously improved to form a prediction and evaluation system, further enhance the neural network’s prediction accuracy and generalization ability, and provide effective help for practical projects.

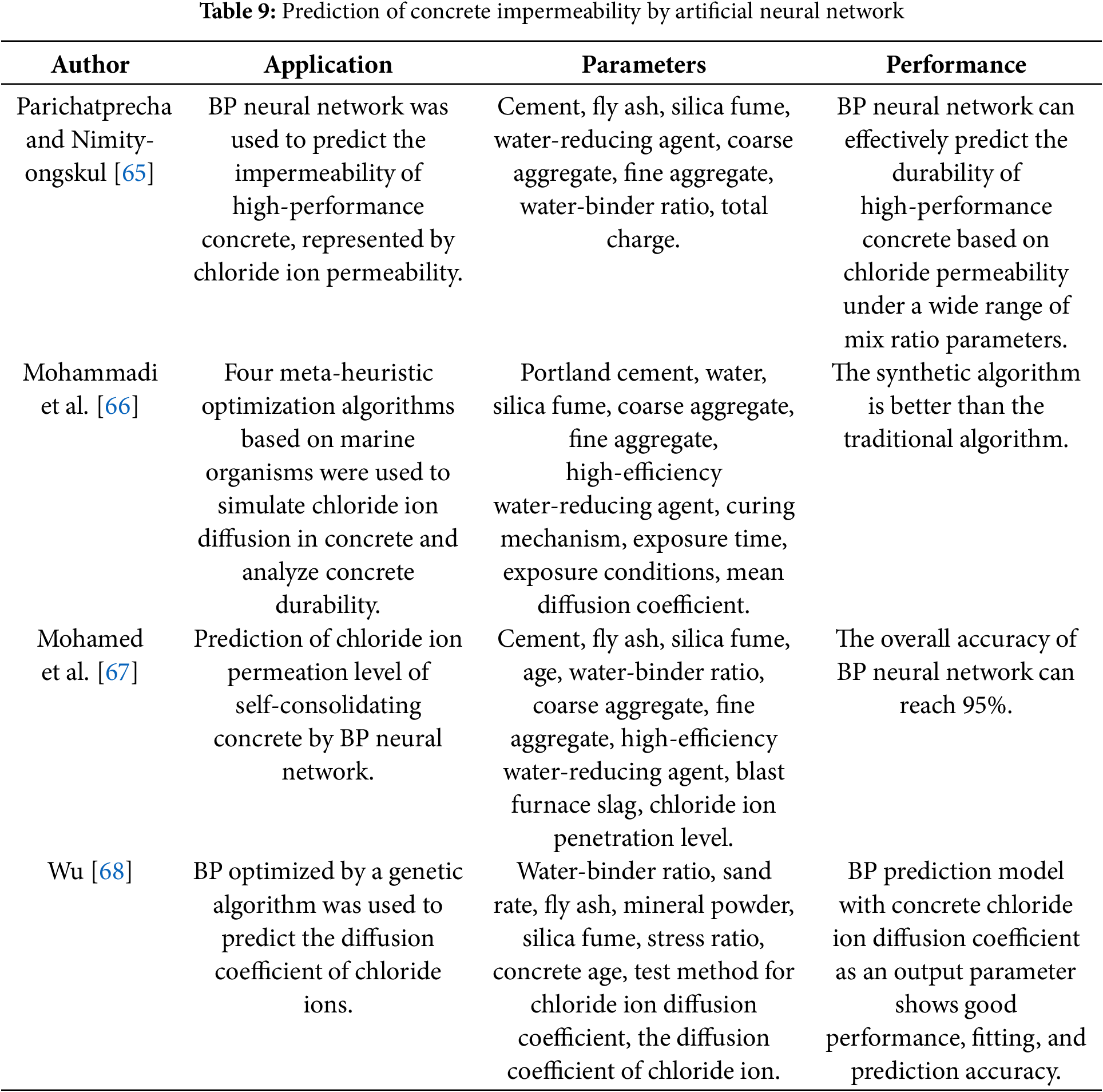

5.2 Prediction of Impermeability

Chloride-ion penetration is one of the main reasons that affect the durability of concrete in coastal areas of China. It destroys the internal structure of concrete and shortens its working life. There are some differences in the evaluation indexes of the impermeability of concrete at home and abroad. The chloride-ion diffusion coefficient of concrete is used to evaluate the performance of the impermeability of concrete. Due to the numerous factors affecting the chloride-ion diffusion coefficient in concrete, such as water-binder ratio, porosity, mineral admixture amount, ambient temperature, humidity, and curing age, and the long experimental period and complex process, the final results do not meet the expected standards.

With the rapid development of ANN, using neural networks can avoid discussing and analyzing the factors affecting the chloride-ion diffusion coefficient of concrete and directly establish a model to predict the impervious performance of concrete. Yao et al. [63] adopted the adaptive wavelet neural network to study the nonlinear mapping relationship between the chloride-ion diffusion coefficient of concrete and mix-design parameters. They established an intelligent model to evaluate substantial anti-seepage performance. The highly reliable model can be used to design and assess concrete permeability. Liu et al. [64] used BP and RBF to establish models for predicting chloride-ion concentration distribution in concrete. A comparison of the two shows that RBF has better prediction accuracy and stability. Table 9 describes in detail the application of ANN for predicting impermeability.

Combining ANN and various optimization algorithms can significantly improve its generalization performance and operation speed. For example, Li et al. [69] used a fuzzy comprehensive evaluation method together with ANN to predict the compatibility between cement and admixtures. Zhao [70] conducted an in-depth analysis of GA and ANN, established a strength prediction model, and proposed a new mix ratio design method. Based on current research, a concrete chloride-ion diffusion coefficient test database has been established to facilitate the self-updating of future prediction models and provide a basis for the mix design and durability testing of concrete [71]. By studying concrete permeability, a posteriori distribution of neural network connection weights and thresholds is obtained according to the prior distribution of input factors to establish a life prediction model of concrete structure based on reliability [68].

In summary, the ANN used to study concrete durability is reviewed. When ANN is used for predicting antifreeze performance, BP is usually used, and its performance is slightly better than that of RBF. When ANN is used for predicting imperturbability, generalization performance and calculation speed can be significantly improved by optimizing the model with different algorithms. Based on existing research, a chloride-ion diffusion coefficient database has been established to facilitate the self-updating of the prediction model.

Here we provide three open-source datasets for concrete data: the University of California, Irvine (UCI) ML repository, Kaggle, and Harvard Dataverse. From the three sources, a large amount of concrete data can be obtained, providing the convenience for researchers. For example, Yeh [72] created the concrete compressive strength dataset having 1030 instances. Roqayyeh [73] created the concrete strength dataset on Kaggle. The UCI concrete dataset, from the laboratory configuration of a university in Taiwan, has low regional representativeness. The Harvard dataverse, collected from field sites in a specific U.S. state, also has low regional representativeness. The Kaggle concrete dataset, collected from various locations around the world or prepared in laboratories, features diverse and representative samples.

6.2 Selection of Input Parameters

To avoid the redundancy or omission of key factors, scientific selection methods are discussed here. In order to reduce the computing cost and minimize the highly correlated input variables, the principal component analysis (PCA) is employed to process the input variables. PCA is that the optimized input vector, based on the variance contribution rate of the input vector in the principal component directions, is determined, and then the optimized input vector is projected onto the principal component directions [74]. This projected vector serves as the input vector of the ANN.

In 1993, Soboĺ [75] proposed the Sobol analysis method, which is widely applied in engineering. The Sobol analysis method (i.e., Sobol global sensitivity analysis) determines the important input variables by analyzing the influence of each input variable on the output variable. The first-order sensitivity index is the ratio of the variance of the output variable generated by each input variable to the total variance of the output variable, while the total effect index is the sum of the variance of the output variable generated by each input variable and the variance of the output variable caused by the interaction between the variables, and is also the ratio to the total variance of the output variable. By comparing the two indices, the appropriate input variables can be selected. Because the Sobol analysis method is global-oriented, it requires a large amount of computing resources. The Sobol analysis method can determine the interaction between input variables, but it is not applicable when the number of input variables exceeds 50.

For the prediction of the concrete performance, the input variables can be selected in this sequence: first, conduct preliminary screening based on professional knowledge; then, perform PCA and Sobol analysis; finally, cross-validate the results of both analyses to determine the appropriate input variables.

Data preprocessing usually involves handling missing values, outlier detection, data standardization and normalization, data splitting, and data cross-validation.

For the concrete mixture sample dataset, if the proportion of missing data for a certain physical quantity of a mixture ratio exceeds 5%, the mixture ratio sample with the missing data will be directly deleted. If the proportion of missing data for a certain physical quantity of a mixture ratio is less than 5%, the missing data can be supplemented using the multiple imputation by chained equations (MICE) technique. MICE combines the existing data and uses mathematical models to obtain multiple estimated values for the missing data, and then takes the average of these estimated values to supplement the missing values [76].

The outlier detection is used to handle the outliers to ensure the reliability of the research. Common methods for outlier detection include the box-plot method, K-NN method, and the 3σ rule etc. [77]. The box-plot method detects the outliers by a threshold. The K-NN method identifies samples that deviate too much from the others as outliers. For normally distributed samples, the 3σ rule can be used to identify outliers. Outliers can be directly deleted or corrected.

Different variables have different units and ranges, which may affect the results. Therefore, it is necessary to standardize and normalize the sample data. The commonly used Z-score method converts the sample data into data with a mean of zero and a variance of one, which is the process of data standardization [78]. Transforming the sample data into a smaller range, such as [0, 1] or [−1, 1], is the process of data normalization [78].

The data are divided into a test set, a training set, and a validation set. Then, the data is repeatedly re-divided for cross-validation to obtain a reasonable test set, training set, and validation set.

Data preprocessing should be carried out in the following order: first, handle the missing values of the data; then, perform the outlier detection; next, conduct data standardization and normalization; finally, divide the data and perform data cross-validation. The data undergoing the above preprocessing can be used for ANN to yield reasonable prediction results.

Because BP easily falls into local optima, it is often optimized by other algorithms. Here, we discuss the suitability, computational costs, or practical trade-offs in engineering applications for the combination algorithms.

Kashyzadeh et al. [38] developed a GA-BP model to predict the concrete strength, and the results were verified by the experimental results, indicating that GA-BP is feasible for engineering applications. Su et al. [79] used GA-BP to predict the elastic modulus of the concrete. By GA-BP, the MAE of the training set and the test set are 1.057 and 1.1257, respectively. And the results of BP are 1.2038 and 1.3562, respectively. GA-BP is superior to BP. Li and Peng [48] used the Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm to optimize BP, and Levenberg-Marquardt-BP was applied to predict the 28 d compressive strength of concrete. The predicted results were not significantly different from the measured results (relative errors all exceeded 6%), indicating that Levenberg-Marquardt-BP is feasible for engineering applications. And Levenberg-Marquardt-BP had a fast convergence speed and a very high training accuracy. Liu et al. [62] used Levenberg-Marquardt-BP to predict the frost resistance of recycled aggregate concrete. They found that Levenberg-Marquardt-BP has higher efficiency and better performance than other algorithms. Fan et al. [80] used BP optimized by the logistic-chaos-improved sparrow search algorithm (LCSSA) for the prediction of 7 d compressive strength of concrete. They found that LCSSA-BP has higher accuracy and lower error than other models. Zhou et al. [81] used ANN to obtain the prediction model of 28 d compressive strength of concrete. Then the prediction model was made as a constraint condition, and GA was used for mix-proportion optimization. The cost of the optimized concrete decreased from $1000 to $838.8.

Numerous studies have revealed that the combination algorithms have great suitability in engineering applications. And the combination algorithms have faster convergence speed and higher accuracy, indicating that computational costs have been saved. BP, a global approximation model, needs to correct the ownership values and thresholds, having a slower learning speed than RBF and limiting the application of combination algorithms in some real-time demanding scenarios (such as real-time control).

The error metrics are used for evaluating the accuracy of ANN. Mean-absolute error (MAE) is the average of the absolute differences between the measured values and the predicted values of each sample. Root-mean-square error (RMSE) is the square root of the average of the squared differences between the measured values and the predicted values of each sample, used to evaluate the proximity of the measured values and the predicted values. Compared with MAE, RMSE is more sensitive to large errors. Mean-squared error (MSE) is the average of the squared differences between the measured values and the predicted values of each sample. R² is used to evaluate the proximity of the predicted values and the measured values. It is calculated by dividing the sum of the squared differences between the measured values and the predicted values by the sum of the squared differences between the measured values and their average, and then subtracting this value from 1 to obtain the R2 value. The range of R2 is 0 to 1, and the larger the value, the closer the predicted values are to the measured values. Nash-Sutcliffe efficiency (NSE) is also used to evaluate the proximity of the predicted values and the measured values, similar to R2. Compared with R2, NSE is more sensitive to the penalty of residuals. Mean-absolute-percentage error (MAPE) is the average relative error of each sample, used to represent the prediction accuracy. When processing the sample data, these indicators should be used comprehensively.

To explain ANN, Lundberg and Lee [82] proposed Shapley additive explanations (SHAP) framework. In a review paper, Abioye et al. [83] proposed SHAP analysis for ML models, and the relationship between the input features and the predictions of compressive strength could be understood. Nikoopayan et al. [84] researched the application of SHAP analysis to explain the feature interactions for the prediction of concrete compressive strength. Ribeiro et al. [85] developed local interpretable model-agnostic explanations (LIME) to explain the prediction results of any classifier by learning an interpretable model locally around the prediction. Kulasooriya et al. [86] applied SHAP and LIME to explain ML models for the strength prediction of the concrete. The whole model, the feature dependencies, and the instances had been explained in detail by SHAP. However, LIME only made instance explanations. They found that the explanation ways have some differences for different ML models. They thought that it is essential to further research the explanation models. SHAP is used for the global interpretation and its results are more accurate. LIME is used for the local explanations and has a fast running speed.

6.7 Practical Engineering Challenges

For real-time data acquisition, the sensor-redundancy mechanism can be applied [87]. To avoid the risk of single-point failure in data collection, multiple sets of sensors are used to repeatedly measure the same physical quantity. At the same time, the measured data can be mutually verified, and erroneous data can be eliminated. Considering the computational resource demands, the edge computing technology should be utilized [87]. In order to enhance decision-making efficiency, the collected data should be sent to the server in an attachment for calculation, rather than to the central server. Gouveia et al. [87] utilized the sensor redundancy mechanism and the edge computing technology for constructing a real-time data acquisition and computation system.

ANN has high computing speed and accuracy, and the disadvantages are the need for a large amount of sample data and poor interpretability during the operation [88]. The advantages of the physical model (PM) are that physical laws are easy to explain, the computational load is low, and data can be inferred based on physical laws. The disadvantages are that empirical coefficients in the formulas need to be calibrated through a large number of experiments. The advantages of the finite element method (FEM) are that it can complete complex nonlinear analysis, the calculation results are visualized, and the physical meaning is easy to explain [88]. The disadvantages are that it has high requirements for the computer performance due to the large computational load, and the accurate loading, the constraint setting, and the meshing are required [88]. Based on the advantages and disadvantages of ANN, PM, and FEM, different methods are adopted in different application scenarios. For scenarios requiring rapid assessment or quality control, ANN is used. For scenarios requiring regulatory verification or determination of long-term performance, PM is used. For complex nonlinear analysis scenarios, FEM is used. It is recommended to combine these three methods to fully leverage their respective advantages. Depending on the specific scenario, one method can be the main approach, with the others serving as supplementary. Wu et al. [89] combined FEM and ANN for the concrete research, and this method was verified by the experimental results.

6.9 Development of More Interpretable Algorithms

To develop an interpretable system for the prediction of the strength, deformation, and durability of concrete, the following steps can be carried out. First, construct the dataset. The sensor redundancy mechanism can be used for acquiring the real-time data, including the concrete mix ratio, the time-series signals, the images, the voxels, etc., [87]. The time-series signals include the ultrasound pulse waveforms, the temperature curves, the humidity curves, etc. A concrete multi-mode (CM) dataset having 40,000 samples can be constructed. Second, construct a hybrid model architecture. CNN is used to process images, voxels, waveforms, etc. The hybrid model architecture is named CNN-BP-SHAP. The information, such as pores, cracks, and waveform peaks, is automatically extracted. BP is utilized for the prediction of the strength, deformation, and durability of the concrete. SHAP, used for the global interpretation, is applied to interpret the hybrid model, achieving more accurate results than LIME [86]. The edge computing technology can be used to save computational resources [87]. Third, establish a field verification system. The predicted results are compared with the experimental results to continuously optimize the prediction system.

The technology of using ANN to predict concrete performance has become increasingly mature. Through the introduction and analysis of the types of ANN models, this paper provides reasonable and effective methods for beginners in selecting appropriate ANN models. Here, this article presents several future research directions.

1. For the prediction of the strength, deformation, and durability of the concrete, ANN requires a large amount of data to obtain accurate results. Currently, there is still a lack of suitable data sets, so developing data sets with diversity and a large number of samples is a key research direction in the future.

2. This paper reviews the combination model, combining different models and utilizing each other’s advantages, which provides a direction for future research.

3. To apply ANN for the performance prediction of the concrete, the most obvious problems are to explain the reasoning process and basis, and to communicate with users. Although SHAP and LIME have been used for the concrete in some studies, the research on ANN interpretability is still quite insufficient. To construct a hybrid model architecture of interpretability research is a problem.

This paper mainly discusses the research status of ANN in concrete. The review shows that ANN is beneficial for predicting concrete strength, deformation, and durability. The excellent self-learning function, the associative memory function, and the ability to quickly find optimal solutions are suitable for predicting problems involving multiple influencing factors in concrete. The effective utilization in this field can save the test resources, improve the work efficiency, and have a particular guiding value for the quality control of concrete engineering.

1. As a rapidly emerging practical tool, ANN can replace the empirical or semi-empirical performance research models currently used in concrete.

2. The research on the strength of the concrete based on ANN has been gradually completed, but the research on the deformation and the durability is still in the exploratory stage.

3. When establishing an ANN model, the input parameters should be reasonable, and the sample coverage of the selected dataset should be wide.

4. There has been a gradual increase in the use of the hybrid model, having higher accuracy and better performance than a single model.

5. Constructing a hybrid model architecture for the model interpretation (e.g., CNN-BP-SHAP) is an important research.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the Ningbo Construction Research Project (Nos. 2024-23, 2024-20), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52478281), and the Ningbo Public Welfare Science and Technology Project (No. 2024S077).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, funding acquisition, methodology, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing: Yidong Xu; writing—original draft: Weijie Zhuge; writing—original draft: Jialei Wang; writing—review & editing: Xiaopeng Yu; writing—review & editing: Kan Wu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Kumar R, Rai B, Samui P. Prediction of mechanical properties of high-performance concrete and ultrahigh-performance concrete using soft computing techniques: a critical review. Struct Concr. 2024;26(2):1309–37. doi:10.1002/suco.202400188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Moodi Y. Providing models of the compressive strength of square and rectangular (S/R) concrete confined using genetic programming. J Numer Methods Civil Eng. 2025;9(3):16–27. doi:10.61186/NMCE.2312.1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Singh P, Prasad B, Kumar V, Murthy YR. Compressive and tensile strengths of linz-donawitz slag aggregate concrete and their random forest prediction. Indian Concr J. 2024;98(10):3. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-4123366/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Wang Q. Estimation of compressive strength of recycled aggregate concrete using advanced meta-heuristic algorithms and random forest analysis. Multiscale Multidiscip Model Exp Design. 2024;7:3551–66. doi:10.1007/s41939-024-00413-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Rao JV, Kumar KH, Satish N. Compressive strength prediction of fly ash geopolymer concrete using support vector and random forest regression. J Phys Conf Series. 2024;2779:012048. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/2779/1/012048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Parhi SK, Patro SK. Compressive strength prediction of PET fiber-reinforced concrete using Dolphin echolocation optimized decision tree-based machine learning algorithms. Asian J Civil Eng. 2024;25:977–96. doi:10.1007/s42107-023-00826-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Gupta T, Patel KA, Siddique S, Sharma RK, Chaudhary S. Prediction of mechanical properties of rubberised concrete exposed to elevated temperature using ANN. Measurement. 2019;147:106870. doi:10.1016/j.measurement.2019.106870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Chopra P, Sharma RK, Kumar M. Prediction of compressive strength of concrete using artificial neural network and genetic programming. Adv Mater Sci Eng. 2016;2016:7648467. doi:10.1155/2016/7648467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Torre A, Garcia F, Moromi I, Espinoza P, Acuña L. Prediction of compression strength of high performance concrete using artificial neural networks. J Phys Conf Series. 2015;582(1):012010. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/582/1/012010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Jagadesh P, Khan AH, Shanmuga PB, Asheeka A, Zoubir Z, Magbool HM, et al. Artificial neural network, machine learning modelling of compressive strength of recycled coarse aggregate based self-compacting concrete. PLoS One. 2025;20(4):e0322947. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0322947. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Moodi Y, Hamzehkolaei NS, Afshoon I. Machine learning models for predicting compressive strength of eco-friendly concrete with copper slag aggregates. Mater Today Commun. 2025;46:112572. doi:10.1016/j.mtcomm.2025.112572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Hamed AK, Elshaarawy MK, Alsaadawi MM. Stacked-based machine learning to predict the uniaxial compressive strength of concrete materials. Comput Struct. 2025;308:107644. doi:10.1016/j.compstruc.2025.107644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Asteris PG, Mokos VG. Concrete compressive strength using artificial neural networks. Neural Comput Appl. 2020;32(15):11807–826. doi:10.1007/s00521-019-04663-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Hinton GE, Osindero S, Teh Y. A fast-learning algorithm for deep belief nets. Neural Comput. 2006;18(7):1527–54. doi:10.1162/neco.2006.18.7.1527. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Schmidhuber J. Deep learning in neural networks: an overview. Neural Netw. 2015;61:85–117. doi:10.1016/j.neunet.2014.09.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Lecun Y, Bengio Y, Hinton G. Deep learning. Nature. 2015;521(7553):436–44. doi:10.1038/nature14539. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Zhang L, Zhang B. A geometrical representation of McCulloch-Pitts neural model and its applications. IEEE Trans Neural Netw. 1999;10(4):925–9. doi:10.1109/72.774263. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Hebb DO. The organization of behavior: a neuropsychological theory. New York, NY, USA:John Wiley and Sons, Inc.; 1949. [Google Scholar]

19. Ramsauer H, Schäfl B, Lehner J, Seidl P, Widrich M, Adler T, et al. Hopfield networks is all you need. arXiv:2008.02217. 2021. [Google Scholar]

20. Hopfield JJ. Neural networks and physical systems with emergent collective computational abilities. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982;79(8):2554–8. doi:10.1073/pnas.79.8.2554. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Powell MJD. Radial basis functions for multivariable interpolation: a review. In: Algorithms for approximation: IMA conference on algorithms for the approximation of functions and data. Shrivenham, UK: Edinburgh Campus Library; 1985. [Google Scholar]

22. Rumelhart DE, Hinton GE, Williams RJ. Learning representations by back-propagating errors. Nature. 1986;323:533–6. doi:10.1038/323533a0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Oh S. Error back-propagation algorithm for classification of imbalanced data. Neurocomputing. 2011;74(6):1058–61. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2010.11.024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Sarkar D. Methods to speed up error back-propagation learning algorithm. ACM Comput Surv. 1995;27(4):519–44. doi:10.1145/234782.234785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Broomhead DS, Lowe D. Radial basis functions, multi-variable functional interpolation and adaptive networks. Worcestershire, UK:Royal Signals and Radar Establishment; 1988 [cited 2025 Aug 14]. Available from: https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/tr/pdf/ADA196234.pdf. [Google Scholar]

26. Fritzke B. Fast learning with incremental RBF networks. Neural Process Lett. 1994;1:2–5. doi:10.1007/h02132392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Jiang Q, Zhu L, Shu C, Sekar V. An efficient multilayer RBF neural network and its application to regression problems. Neural Comput Appl. 2022;34(6):4133–50. doi:10.1007/s00521-021-06373-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Alzubaidi L, Zhang J, Humaidi AJ, Al-Dujaili A, Duan Y, Al-Shamma O, et al. Review of deep learning: concepts, CNN architectures, and applications. J Big Data. 2021;8:53. doi:10.1186/s40537-021-00444-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Talaei Khoei T, Ould Slimane H, Kaabouch N. Deep learning: systematic review, models, challenges, and research directions. Neural Comput Appl. 2023;35:23103–24. doi:10.1007/s00521-023-08957-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Deng L, Yu D. Deep learning: methods and applications. Found Trends® Signal Process. 2014;7(3–4):197–387. doi:10.1561/2000000039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Abiodun OI, Jantan A, Omolara AE, Dada KV, Mohamed NA, Arshad H. State-of-the-art in artificial neural network applications: a survey. Heliyon. 2018;4(11):e00938. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2018.e00938. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Dai X, Liu J, Zhang X. A review of studies applying machine learning models to predict occupancy and window-opening behaviors in intelligent buildings. Energy Build. 2020;223:110159. doi:10.1016/j.enbuild.2020.110159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Adeli H. Neural networks in civil engineering: 1989–2000. Comput-Aided Civil Infrast Eng. 2001;16(2):126–42. doi:10.1111/0885-9507.00219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Sirca GF Jr, Adeli H. System identification in structural engineering. Sci Iran. 2012;19(6):1355–64. doi:10.1016/j.scient.2012.09.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Zhang P, Yin ZY, Jin YF. State-of-the-art review of machine learning applications in constitutive modeling of soils. Arch Comput Methods Eng. 2021;28(5):3661–86. doi:10.1007/s11831-020-09524-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Akbar A, Liew KM, Farooq F, Khushnood RA. Exploring mechanical performance of hybrid MWCNT and GNMP reinforced cementitious composites. Constr Build Mater. 2020;267:120721. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.120721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Amar M, Benzerzour M, Zentar R, Abriak N-E. Prediction of the compressive strength of waste-based concretes using artificial neural network. Materials. 2022;20(15):7045. doi:10.3390/ma15207045. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Kashyzadeh KR, Amiri N, Ghorbani S, Souri K. Prediction of concrete compressive strength using a back-propagation neural network optimized by a genetic algorithm and response surface analysis considering the appearance of aggregates and curing conditions. Buildings. 2022;12(4):438. doi:10.3390/buildings12040438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Bu L, Du G, Hou Q. Prediction of recycled aggregate concrete compressive strength based on artificial neural network. Materials. 2021;14(14):3921. doi:10.3390/ma14143921. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Zheng NH, Zhang WP, Zhou Y, Liu Y. Confinement strength prediction of corroded rectangular concrete columns using BP neural networks and support vector regression. Structures. 2024;127:107021. doi:10.1016/j.istruc.2024.107021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Guo J, Wu Q, Sun L, Sheng H. Lap-slip model of rebar-to-concrete in RC/ECC/UHPC based on GA-BP neural network. Case Stud Constr Mater. 2024;20:e03287. doi:10.1016/j.cscm.2024.e03287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Feng C. Optimized proportioning model and efficacy analysis of high performance concrete in bridge construction. Appl Math Nonlinear Sci. 2024;9(1):1–15. doi:10.2478/amns-2024-2538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Al-Bukhaiti K, Liu Y, Zhao S, Han D. Based on BP neural network: prediction of interface bond strength between CFRP layers and reinforced concrete. Pract Period Struct Design Constr. 2024;29(2):04023067. doi:10.1061/PPSCFX.SCENG-1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Ma P, Zhou F, Liu L, Li F, Kang H, Gao H, et al. Study on the constitutive relationship and mechanical properties fitting of SFRC based on optimized BP neural network. J Phys Conf Series. 2024;2891(6):062002. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/2891/6/062002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Zhao S, Liu Y. Performance prediction of commercial concrete based on RBF neural network. Comput Eng. 2005;31(18):36–7, 40. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

46. Wu N. Predicting the compressive strength of concrete using an RBF-ANN model. Appl Sci. 2021;11(14):6382. doi:10.3390/app11146382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Lin CJ, Wu N. An ANN model for predicting the compressive strength of concrete. Appl Sci. 2021;11(9):3798. doi:10.3390/app11093798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Li H, Peng T. Prediction of concrete compression strength based on BP and RBF neural network theories. J Wuhan Univ Technol. 2009;31(8):33–6. (In Chinese). doi:10.3963/j.issn.1671-4431.2009.08.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Liu W. Research on control and optimization of concrete shrinkage deformation based on artificial neural network. Tianjin, China: Tianjin University; 2010. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

50. Garoosiha H, Ahmadi J, Bayat H. The assessment of Levenberg-Marquardt and Bayesian framework training algorithm for prediction of concrete shrinkage by the artificial neural network. Cogent Eng. 2019;6:1609179. doi:10.1080/23311916.2019.1609179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Kong Y, Kurumisawa K. Prediction of the drying shrinkage of alkali-activated materials using artificial neural networks. Case Stud Constr Mater. 2022;17(5):e01166. doi:10.1016/j.cscm.2022.e01166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Bažant ZP, Hauggaard AB, Baweja S, Ulm FJ. Microprestress-solidification theory for concrete creep. I: aging and drying effects. J Eng Mech. 1997;123(11):1188–94. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9399(1997)123:11(1188). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Vandamme M. Two models based on local microscopic relaxations to explain long-term primary creep of concrete. Proc R Soc A. 2018;474(2220):20180477. doi:10.1098/rspa.2018.0477. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Taha MR, Noureldin A, El-Sheimy N, Shrive NG. Artificial neural networks for predicting creep with an example application to structural masonry. Can J Civ Eng. 2003;30(3):523–32. doi:10.1139/l03-003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Zhu J, Wang Y. Convolutional neural networks for predicting creep and shrinkage of concrete. Constr Build Mater. 2021;306:124868. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.124868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Al-Rihimy A, Al-Shathr B, Al-Attar T. Prediction of creep strain for self-compacting concrete by artificial neural networks. Kufa J Eng. 2019;10(2):90–100. doi:10.30572/2018/kje/100207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Gedam BA, Bhandari NM, Upadhyay A. An apt material model for drying shrinkage and specific creep of HPC using artificial neural network. Struct Eng Mech. 2014;52(1):97–113. doi:10.12989/sem.2014.52.1.097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Zhao N, Zhang A. The prediction of frost-resisting durability of concrete based on artificial neutral network. In: Proceedings of International Conference on Engineering and Business Management (EBM2011); 2011 Mar 22–24; Wuhan, China. [Google Scholar]

59. Yan C, Zhang A, Hu H, Hu C. Prediction of RBF and improved BP neural network on concrete frost resistance. Cement Eng. 2016;5:19–22. (In Chinese). doi:10.13697/j.cnki.32-1449/tu.2016.05.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Xiao Q, Fan J. Based on artificial neural network prediction concrete frost resistance. Concrete. 2013;(1):30–2. (In Chinese). doi:10.3969/j.issn.1002-3550.2013.01.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Zhao N. The prediction of frost resistance of concrete based on artificial neural networks. Baotou, China:Inner Mongolia University of Science and Technology; 2010. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

62. Liu K, Zou C, Zhang X, Yan J. Innovative prediction models for the frost durability of recycled aggregate concrete using soft computing methods. J Build Eng. 2021;34:101822. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2020.101822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Yao L, Tang Z, Liu R. Self-adaptive wavelet neural network for predicting impermeability of concrete. Concrete. 2011;(5):15–7. (In Chinese). doi:10.3969/j.issn.1002-3550.2011.05.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Liu Q, Iqbal MF, Yang J, Lu X, Zhang P, Rauf M. Prediction of chloride diffusivity in concrete using artificial neural network: modelling and performance evaluation. Constr Build Mater. 2021;268:121082. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.121082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Parichatprecha R, Nimityongskul P. Analysis of durability of high performance concrete using artificial neural networks. Constr Build Mater. 2009;23(2):910–7. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2008.04.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Mohammadi GE, Kashani A, Kim T, Arashpour M. Concrete chloride diffusion modeling using marine creatures-based metaheuristic artificial intelligence. J Clean Prod. 2022;374:134021. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.134021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Mohamed O, Kewalramani M, Ati M, Hawat WA. Application of ANN for prediction of chloride penetration resistance and concrete compressive strength. Materialia. 2021;17:101123. doi:10.1016/j.mtla.2021.101123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Wu H. Study on chloride ion corrosion resistance and service life prediction of concrete based on neural network. Guangzhou, China: South China University of Technology; 2019. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

69. Li Y, Zhao Z, Ke Y. Application of fuzzy judging on compatibility of common portland cement and set retarding and water reducing ad mixtures. Concrete. 2007;(1):40–1. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

70. Zhao S. Application of genetic neural network in strength prediction and mix ratio design of fly ash concrete. Baoding, China: Agricultural University of Hebei; 2002. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

71. Zuo J. Prediction of chloride ion diffusion coefficient of fly ash concrete based on artificial neural network. Hengyang, China: University of South China; 2012. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

72. Yeh I. Concrete compressive strength/UCI machine learning repository; 1998. [cited 2025 Aug 14]. Available from: https://archive.ics.uci.edu/dataset/165/concrete+compressive+strength. [Google Scholar]

73. Roqayyeh. Concrete strength dataset. [cited 2025 Aug 14]. Available from: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/roqayyeh/concrete-strength-dataset. [Google Scholar]

74. Greenacre M, Groenen PJF, Hastie T, d’Enza AI, Markos A, Tuzhilina E. Principal component analysis. Nat Rev Methods Primers. 2022;2(1):100. doi:10.1038/s43586-022-00184-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

75. Soboĺ IM. Sensitivity estimates for nonlinear mathematical models. Math Model Comput Exp. 1993;4(1):407–14. [Google Scholar]

76. Allison PD. Multiple imputation for missing data: a cautionary tale. [cited 2025 Aug 14]. Available from: https://www.sas.upenn.edu/~allison/MultInt99.pdf. [Google Scholar]

77. Karthikeyan HO. Improving concrete quality. [cited 2025 Aug 14]. Available from: https://civiconcepts.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Improving-Concrete-Quality-By-Karthikeyan-H.-Obla.pdf. [Google Scholar]

78. Kalinina I, Gozhyj A, Bidyuk P, Gozhyi V, Korobchynskyi M, Nadraga V. A systematic approach to data normalization and standardization in machine learning problems. In: Babichev S, Lytvynenko V, editors. 2024 International Scientific Conference “Intelligent Systems of Decision-Making and Problems of Computational Intelligence”; 2024. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2025. p. 206–19. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-88483-2_11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

79. Su Z, Sui Y, Huang W. Prediction of elastic modulus of lightweight aggregate concrete based on GA-BP Neural Network. Civil Eng. 2025;14(5):962–9. (In Chinese). doi:10.12677/hjce.2025.145104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

80. Fan M, Yang P, Li W, Ren W, Ma C. Early compressive strength prediction and extreme value optimization for high performance concrete. Bull Chin Ceram Soc. 2024;43(12):4339–49. (In Chinese). doi:10.16552/j.cnki.issn1001-1625.2024.12.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

81. Zhou S, Jia Y, Li K, Li Z, Wu X, Peng H, et al. Mix proportion optimization of ultrahigh performance concrete based on machine learning. J Tongji Univ. 2024;52(7):1018–23. (In Chinese). doi:10.11908/j.issn.0253-374x.23419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

82. Lundberg SM, Lee S-I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. Adv Neural Inform Process Syst. 2017;30:4768–77. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1705.07874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

83. Abioye SO, Babatunde YO, Abikoye OA, Shaibu AN, Bankole BJ. Optimized machine learning algorithms with SHAP analysis for predicting compressive strength in high-performance concrete. AI Civil Eng. 2025;4:16. doi:10.1007/s43503-025-00061-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

84. Nikoopayan Tak MS, Feng Y, Mahgoub M. Advanced machine learning techniques for predicting concrete compressive strength. Infrastructures. 2025;10(2):26. doi:10.3390/infrastructures10020026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

85. Ribeiro MT, Singh S, Guestrin C. Why should I trust you: explaining the predictions of any classifier. In: The 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining; 2016 Aug 13–17; San Francisco, CA, USA. p. 1135–44. doi:10.1145/2939672.2939778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

86. Kulasooriya WKVJB, Ranasinghe RSS, Perera US, Thisovithan P, Ekanayake IU, Meddage DPP. Modeling strength characteristics of basalt fiber reinforced concrete using multiple explainable machine learning with a graphical user interface. Sci Rep. 2023;13:13138. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-40513-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

87. Gouveia G, Alves J, Sousa P, Araújo R, Mendes J. Edge computing-based modular control system for industrial environments. Processes. 2024;12(6):1165. doi:10.3390/pr12061165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

88. Quarto M, D’Urso G, Giardini C, Maccarini G, Carminati M. A comparison between finite element model (FEM) simulation and an integrated artificial neural network (ANN)-particle swarm optimization (PSO) approach to forecast performances of micro electro discharge machining (Micro-EDM) drilling. Micromachines. 2021;12:667. doi:10.3390/mi12060667. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

89. Wu Y, Chen J, Zhu P, Zhi P. Finite element analysis of perforated prestressed concrete frame enhanced by artificial neural networks. Buildings. 2024;14(10):3215. doi:10.3390/buildings14103215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools