Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

State-of-Art on Workability and Strength of Ultra-High-Performance Fiber-Reinforced Concrete: Influence of Fiber Geometry, Material Type, and Hybridization

1 Guangxi Transportation Science and Technology Group Co., Ltd., Nanning, 530007, China

2 College of Engineering, Ocean University of China, Qingdao, 266400, China

3 Research Institute of Highway Ministry of Transport, Beijing, 100088, China

4 Guangxi Transport Vocational and Technical College, Nanning, 530015, China

* Corresponding Author: Lu Liu. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Innovative and Sustainable Materials for Reinforced Concrete Structures)

Structural Durability & Health Monitoring 2025, 19(6), 1589-1605. https://doi.org/10.32604/sdhm.2025.072955

Received 08 September 2025; Accepted 28 October 2025; Issue published 17 November 2025

Abstract

Ultra-high performance fiber-reinforced concrete (UHPFRC) has received extensive attention from scholars and engineers due to its excellent mechanical properties and durability. However, there is a mutually restrictive relationship between the workability and mechanical properties of UHPFRC. Specifically, the addition of fibers will affect the workability of fresh UHPFRC, and the workability of fresh UHPFRC will also affect the dispersion and arrangement of fibers, thus significantly influencing the mechanical properties of hardened UHPFRC. This paper first analyzes the research status of UHPFRC and the relationship between its workability and mechanical properties. Subsequently, it outlines the test methods and indicators of UHPFRC workability, including fluidity, slump, V-funnel passing time, and rheology. Then, it reviews the impacts of metal fibers, synthetic fibers, hybrid fibers, and other fibers on the workability and mechanical properties of UHPFRC, and presents a reasonable range of fiber dosage for workability and mechanical properties. Key findings include: (1) Steel fibers within 1%–2% volume optimize workability-mechanical balance, while exceeding 2.5% reduces compressive strength by 7%–30%; (2) Hybrid steel-polypropylene fibers enhance toughness by 65%; (3) Fiber orientation control via rheology-modifying admixtures improves flexural strength by up to 64%. This review establishes a fiber factor (V·L/D) for predictive mix design, advancing beyond empirical approaches in prior studies.Keywords

Ultra-high-performance fiber-reinforced concrete (UHPFRC) is an advanced cement-based material with excellent mechanical strength and durability. It usually has a dense particle skeleton (packing density of 0.825–0.855), a low water-to-binder ratio (0.15–0.20), and a high fiber content between 2% and 5% [1–4]. These features create a compact microstructure [5] that prevents the penetration of carbon dioxide, sulfates, chloride ions, and water, thus providing superior durability [6–8]. The high fiber content also improves impact resistance [6] and fatigue performance [7]. To meet sustainability goals, recent studies have focused on low-carbon UHPFRC mixtures. These include supplementary binders [8–12], recycled aggregates [13,14], and alkali-activated binders [5,13,15,16], which can reduce CO2 emissions by 20%–40% compared with conventional mixtures [8,17].

Fibers are essential for the mechanical behavior, dimensional stability, and cost of UHPFRC. Their type, shape, amount, orientation, and combination have strong effects on ductility, flexural strength, dynamic response, and energy absorption [18,19]. Because of these advantages, UHPFRC is now widely used in major infrastructure projects around the world, supported by the continuous improvement of related design codes and standards [20]. Fig. 1 shows a UHPFRC bridge deck pavement and the compaction process used in a bridge project in China.

Figure 1: (a) Schematic diagram of ultra-high performance fiber-reinforced concrete bridge deck pavement structure and (b) Compaction diagram for ultra-high performance fiber-reinforced concrete surface layer in bridge engineering

However, using a high volume of fibers creates major challenges. Too many fibers can reduce the workability of fresh UHPFRC and cause fiber clustering, air voids, and honeycombing defects [21]. The flow behavior and fiber dispersion are very sensitive to fiber properties such as type, dosage, aspect ratio, and surface condition. Studies have shown that optimizing rheological parameters—especially yield stress and plastic viscosity—can lower the amount and size of air voids and improve the strength of hardened concrete [22]. For example, researchers have found specific viscosity ranges that produce the best flexural performance for a given fiber volume [23]. Therefore, selecting the right type and amount of fibers is critical to balance fresh workability and hardened strength in UHPFRC design [24].

Although many studies have explored UHPFRC, few have systematically analyzed the relationship between workability and strength for different fiber types [25–29]. This review aims to fill that gap by introducing quantitative models such as the fiber factor (V·L/D) [30–32] to guide mixture design for new applications like 3D printing. The paper summarizes test methods for workability—such as flow spread, slump, V-funnel time, and rheological measurements—and reviews how metallic, synthetic, and hybrid fibers affect both fresh and hardened properties. Steel fibers are still the most common, but new options like basalt fibers [26] and shape memory alloy (SMA) fibers [25], as well as their hybrid combinations, deserve more attention [33–36]. Special focus is given to the balance between fiber geometry and matrix compatibility, especially in low-carbon UHPFRC systems.

To highlight the research gaps and contributions of this paper, they are presented in bullet form as follows:

(1) Research Gaps:

• A systematic analysis of the interdependence between workability and strength in UHPFRC across diverse fiber types (metallic, synthetic, hybrid) is still lacking.

• Previous studies often rely on empirical approaches, with limited use of quantitative models for predicting workability and optimizing mix design, especially for emerging applications like 3D printing.

• The effects of fiber geometry, hybridization, and orientation control on both fresh and hardened properties have not been comprehensively synthesized, particularly within low-carbon UHPFRC systems.

• There is insufficient guidance on the practical implementation of fiber orientation techniques in large-scale structural elements.

(2) Contributions of This Review:

• Introduces and validates the fiber factor (V·L/D) as a predictive tool for workability and mechanical performance, advancing beyond empirical mix design.

• Systematically reviews and synthesizes the effects of steel, synthetic, SMA, basalt, and hybrid fibers on the workability and strength of UHPFRC.

• Provides quantitative recommendations for fiber dosage, aspect ratio, and hybridization to optimize the balance between workability and mechanical properties.

• Highlights the potential of fiber orientation control and Artificial Intelligence (AI)-driven mix design for future UHPFRC development and application.

2 Test Methods and Indicators of the Properties of Fresh UHPFRC

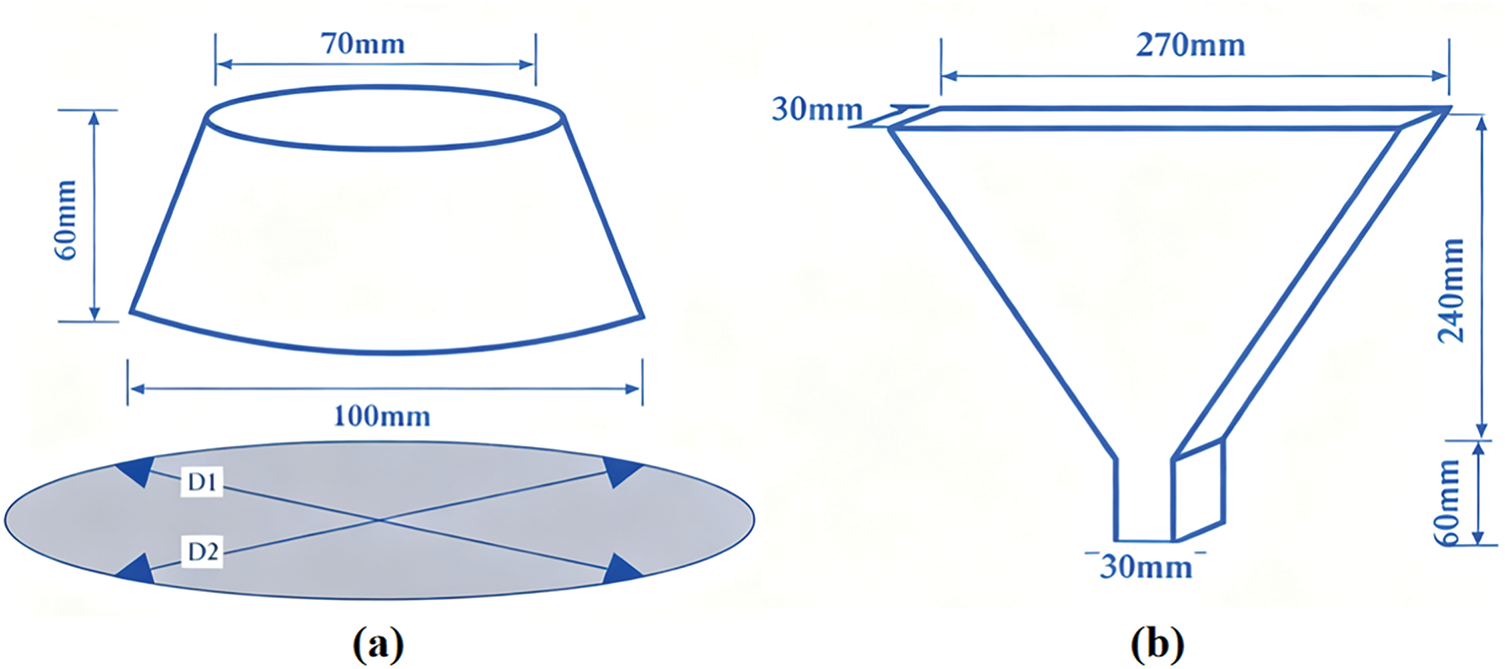

Fluidity describes the mobility of concrete, meaning its ability to flow and fill a mold. For highly fluid UHPFRC, the slump-flow test shown in Fig. 2a is commonly used [37]. The horizontal slump-flow diameter is measured according to ASTM C230. For UHPFRC with lower fluidity, the flow table test is recommended [38], where the spread diameter on the table is recorded.

Figure 2: Commonly used UHPFRC (a) flow and (b) V funnel time test device sizes

The slump test is derived from the ASTM C143 standard and mainly measures the vertical slump of concrete, that is, its ability to collapse and flow.

2.3 V-Shaped Funnel Passing Time

The V-shaped funnel passing time is derived from the EFNARC-2002 standard. It mainly measures the time required for concrete to pass through a V-shaped funnel to assess its fluidity and viscosity. This method is mainly applicable to high-fluidity UHPFRC. The commonly-used size of the V-shaped funnel for UHPFRC is shown in Fig. 2b. In some literature, the flow rate of the V-shaped funnel is also used for evaluation, that is, the average speed at which the concrete flows through the V-shaped funnel [39].

Rheology is a key method for describing the flow and deformation behavior of fresh concrete. It mainly measures plastic viscosity, yield stress, and thixotropy. These parameters usually show a clear relationship with practical workability indicators. In general, higher plastic viscosity increases the flow time in the V-funnel test, while higher yield stress reduces the flow spread diameter. For example, Meng and Khayat [40] found a linear relationship between the plastic viscosity of UHPFRC mortar and its V-funnel flow time under the same fluidity conditions. Similarly, Cao et al. [41] showed that the relationships between flow spread and yield stress, and between plastic viscosity and V-funnel flow rate, follow exponential functions.

The choice of a rheometer for UHPFRC depends on the water–binder ratio, sand gradation, and fiber size. Concentric cylinder rheometers such as the Anton Paar MCR series are suitable for cement paste and fine mortar. Coaxial systems like the ConTec or BML rheometers [40] are more appropriate for mortar and fiber-reinforced UHPFRC. To obtain accurate results, the material should be pre-sheared before testing, and a rheometer with a building materials measurement unit should be used. During testing, each shear step should last long enough to reach steady-state conditions and reduce errors caused by thixotropy. In fiber-reinforced mixtures, parameters such as test duration, shear rate, and gap size must be carefully controlled to avoid fiber movement or separation. Data from the plug flow region should be removed from the final flow curve. Reference [42] describes a standard test for tracking yield stress and plastic viscosity over time using the Anton Paar MCR 302 rheometer. The procedure includes scanning at shear rates from 50 to 200 s−1, pre-shearing at 10 s−1 for 30 s, and following ISO 1920-3:2019.

3 Influence of Fibers on the Properties of Fresh UHPFRC

Steel fibers represent the predominant metallic reinforcement in UHPFRC, valued for their exceptional strength and toughness, though they remain susceptible to corrosion in highly aggressive environments. Currently, these fibers constitute the most extensively utilized reinforcement type in concrete composites. Based on geometrical configuration, they are categorized into straight, bent, hooked-end, and other profiled forms [43]. The aspect ratio of steel fibers generally falls within 20 to 100, with standardized dimensional parameters (length: 6–30 mm, diameter: 0.12–0.5 mm) and viscosity ranges (30–70 Pa·s) established to maintain material consistency.

The geometry and size of steel fibers significantly influence the rheological behavior of fresh UHPFRC [43]. Mixtures incorporating deformed fibers, such as wavy or hooked-end types, exhibit reduced fluidity compared to those with straight fibers, primarily due to enhanced mechanical anchoring and increased internal friction at the fiber-matrix interface. Furthermore, shorter fibers impose less pronounced effects on workability than longer ones. As demonstrated by Meng and Khayat [40], at a constant 2% fiber volume, UHPFRC containing 30-mm hooked-end fibers required over twice the dosage of superplasticizer compared to mixes with 13-mm straight fibers, accompanied by more than 50% higher plastic viscosity and V-funnel flow time. Additionally, fibers with smaller diameters exert more substantial negative impacts on fluidity. For example, in comparing steel fibers with diameters of 0.12 and 0.20 mm (at volume dosages up to 3%), studies [5,44,45] consistently found that finer fibers resulted in reduced workability. Under equivalent strength conditions, the negative impact of steel fibers on workability was milder in alkali-activated ultra-high-performance fiber concrete than in Portland cement systems. Blending short and long steel fibers yielded intermediate workability characteristics.

A fiber volume of 2% is generally considered the upper limit for steel fibers in UHPFRC. Teng et al. [24] confirmed this finding, reporting that when the fiber volume exceeded 2.5%, porosity increased by 15% and compressive strength decreased by 12% (p < 0.05). At lower dosages (≤1%), steel fibers do not significantly reduce fluidity and may even improve it, with decreases usually below 5%. This effect is due to the ability of rigid fibers to rearrange particle packing and push away larger solid particles. However, as fiber content increases, the cohesion between the matrix and fibers becomes stronger, which lowers workability. A sharp loss of fluidity occurs beyond the 2% threshold. Li et al. [46] found that increasing fiber content from 0% to 1% and 2% reduced flow spread from 233 to 222 and 217 mm, corresponding to drops of 5% and 7%, respectively. Similarly, Song et al. [47] observed that a 1% fiber content reduced slump-flow diameter by less than 5%, while 2% and 2.5% contents caused reductions of 16% and nearly 30%, respectively.

Ni-Ti SMA fiber’s impact on concrete workability is complex. Smooth and straight fibers may cause agglomeration and affect workability, while fibers with specific geometries can enhance it. An appropriate volume fraction (0.5%–2.0%) can maintain or improve workability, but excessive amounts lead to reduced workability due to fiber entanglement. When combined with other materials, good interfacial adhesion can be beneficial, while poor adhesion is detrimental. Temperature also affects workability as it impacts the fiber’s properties; improper temperature can be harmful, but rational temperature control may optimize workability [27]. The incorporation of fibers had a negative impact on the fresh properties of concrete; however, the newly developed NiTi-SMA fiber reinforced concrete exhibited satisfactory workability. As fiber content rose from 0.50 vol% to 1.00 vol%, the slump flow diameter reduced from 585 to 565 mm [48].

Synthetic fibers mainly include polyvinyl alcohol fibers, polypropylene (PP) fibers, nylon fibers, polyethylene fibers, etc. Their aspect ratios usually range from 90 to 600. They are characterized by low cost, easy dispersion, and corrosion resistance [49]. However, their strength and toughness are relatively low. Due to their low melting points, these fibers are also used to prevent UHPFRC from spalling at high temperatures. In addition, the high ductility of synthetic fibers can improve the deformation ability of UHPFRC.

Different synthetic fibers have significant differences in their effects on the properties of fresh UHPFRC. But because their aspect ratios are relatively large, reaching up to about six times that of steel fibers, they have low stiffness, are prone to bending and agglomeration, and generally have a more significant deteriorating effect on fluidity than steel fibers [45]. For example, the tests by Cao et al. [45] showed that the yield stress of the polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) fiber mortar with a length of 12 mm was close to 130 Pa, while that of the 13-mm-long steel fiber mortar was only 60 Pa. The increase in PVA fiber content and aspect ratio directly elevates the yield stress and reduces the fluidity of concrete. This occurs because the added fibers create a denser internal network, significantly increasing friction and mechanical interlocking between particles. Furthermore, the hydrophilic PVA fibers absorb free water, reducing the lubricating water film thickness between solid particles. Consequently, greater energy is required to initiate flow, leading to a marked decrease in workability. Hence, steel fibers have relatively high fluidity due to their good dispersibility and low viscosity. PP fibers absorb the least amount of water due to their hydrophobicity, so they have the least impact on workability. Although polyethylene fibers are also hydrophobic, they usually have a relatively large aspect ratio, so their workability also decreases significantly. Nylon fibers have low fluidity due to their high viscosity.

For the same type of synthetic fiber, the higher the fiber content and the larger the aspect ratio, the smaller the fluidity, and the higher the yield stress and plastic viscosity. For example, the tests by Li et al. [46] showed that with the same matrix proportion, when the polyethylene fiber content increased from 0% to 0.5% and 1.0%, the spread diameter of UHPFRC decreased from 233 to 190.5 and 160.8 mm, a reduction of 18% and 31% respectively. The research by Cao et al. [45] showed that 12-mm-long polyvinyl alcohol fibers had a more significant impact on increasing the yield stress and plastic viscosity than 6-mm-long polyvinyl alcohol fibers.

Similar to steel fibers, each type of synthetic fiber has a reasonable dosage range. Within this range, the workability of UHPFRC is reasonable, and good mechanical properties can also be obtained. For example, the research by Si et al. [50] showed that the reasonable range of the product of the volume content and aspect ratio of polyvinyl alcohol fibers is 100–400. Emdadi et al. [51] pointed out that the reasonable range of the product of the volume content and aspect ratio of PP fibers is 100–300. Essentially, regardless of the type of fiber, the workability of cement-based materials is mainly determined by the solid packing state of the fibers.

Hybrid fiber UHPFRC’s fluidity lies between single-fiber systems due to competing effects of aspect ratio and fiber-matrix interaction. For example, Meng and Khayat [40] found that when the fiber dosage is 2%, the demand for water-reducing agents, plastic viscosity, and V-funnel flow time of the hybrid of 30 mm long hooked-end fibers and 13 mm straight steel fibers are between those of UHPFRC with each of the two types of steel fibers added alone. When steel fibers are mixed with synthetic fibers, the fluidity decreases more rapidly due to the generally large aspect ratio of synthetic fibers. For instance, when 0.5% polyvinyl alcohol fibers replace steel fibers, the demand for water-reducing agents and plastic viscosity of UHPFRC both increase by 25% [40]. The experiments by Li et al. [46] showed that the hybridization of polyethylene fibers and steel fibers has a similar effect.

Data from 72 studies were filtered using inclusion criteria: fiber volume (1%–5%), water-binder ratio (0.15–0.25), and adherence to ASTM/EFNARC standards. Variability was minimized by normalizing strength values to equivalent 100 mm cube specimens. Rheological parameters (e.g., plastic viscosity: 30–70 Pa·s) were standardized using ISO 1920-3:2019. Fiber dimensions (length: 6–30 mm, diameter: 0.12–0.5 mm) and test conditions (temperature: 20 ± 2°C) were explicitly reported.

4 Influence of Fibers on the Mechanical Properties of UHPFRC

Fibers serve as essential reinforcements in UHPFRC, and their characteristics—including type, aspect ratio, dosage, and surface morphology—play a decisive role in governing the material’s overall mechanical performance. The subsequent sections provide a detailed discussion on how fibers affect UHPFRC behavior in terms of compressive and flexural strength, pull-out response, and durability under aggressive environmental conditions.

4.1.1 Shape and Size of Specimens

The compressive strength of UHPFRC is commonly evaluated by loading cubic or cylindrical specimens under an increasing compressive force until structural failure occurs [30]. While conventional concrete standards provide clear specifications for specimen geometry and loading rates, these guidelines are typically adopted for UHPFRC with necessary modifications. Standard specimen geometries include cubes, cylinders, and prisms, though the reported dimensions vary considerably among studies. According to Chinese testing practices, cube specimens generally range from 40–50 mm for small samples [47] to 100–150 mm for larger ones. Some studies follow the cement mortar testing procedure in GB/T 17671, employing prism specimens of 40 mm × 40 mm × 160 mm. After flexural testing, the compressive strength is then determined on the previously loaded 40 mm × 40 mm region. In European and American standards, cylindrical specimens typically have diameters between 50 and 150 mm. Other domestic researchers adopt prism specimens, such as 100 mm × 100 mm × 300 mm, for axial compression tests of UHPFRC. In 2021, China officially issued the Standard for Test Methods of Ultra-High Performance Concrete (T/CECS 864-2021), which recommends 100 mm cube specimens for determining compressive strength. Similarly, the national standard Reactive Powder Concrete (GB/T 31387-2015) specifies that axial compressive strength should be tested using prism specimens with dimensions of 100 mm × 100 mm × 300 mm.

4.1.2 Influence of Steel Fibers on Compressive Strength

The incorporation of steel fibers exerts a pronounced influence on the compressive strength of UHPFRC. According to existing studies, introducing 0%–3% steel fibers into the matrix markedly enhances compressive resistance. As fiber dosage increases, crack propagation is progressively restrained. Uniformly dispersed fibers can absorb stress concentrations at their ends, delaying matrix degradation and impeding crack growth, thereby improving compressive capacity. For instance, with a 2% steel fiber dosage, compressive strength can rise from approximately 145 to 162 MPa [50]. Zhong et al. [52] reported that within a 2.5% fiber content range, compressive strength grows steadily with increasing fiber content, achieving up to a 20% improvement. Similarly, Ji et al. [35] observed comparable results at water-to-binder ratios between 0.20 and 0.24.

However, when fiber content exceeds 3%, nonuniform dispersion and fiber clustering may occur, producing internal defects that reduce compressive strength [40]. Meng and Khayat [40] found that UHPFRC incorporating 3% fibers exhibited peak compressive strengths of 140 MPa (7 days) and 158 MPa (28 days). Further increases to 4%–5% led to a strength decline. Zhong et al. [52] also noted that excessive fibers deteriorate mixture flowability, compromising strength enhancement; thus, optimal content should remain below 2.5%. According to Ji et al. [35], when the water-to-binder ratio drops to 0.20, the poor workability of mixtures with 2.5% fibers hinders proper consolidation, highlighting the need for balanced rheology in UHPFRC mix design.

Fiber geometry also affects performance. Hooked-end fibers typically yield higher compressive strength than straight ones due to stronger interfacial bonding achieved through mechanical anchorage and frictional interlock [44]. Bahmani and Mostofinejad [44] demonstrated that the bond strength of corrugated or hooked fibers exceeds that of straight fibers by 3–7 times. This distinction originates from differences in fiber pull-out mechanisms. While hooked fibers marginally raise compressive strength (≤5%), their primary function lies in improving tensile and flexural properties through enhanced crack-bridging behavior [37].

The fiber aspect ratio (AR) also plays a crucial role. Piao et al. [1] reported that increasing AR from 20 to 100 elevated compressive strength from 156.1 to 181.4 MPa—a 16.2% rise—attributed to better stress transfer and fiber–matrix bonding from longer fibers. Higher AR values enlarge the contact area, promoting more efficient load transfer and reducing stress concentrations, which delays failure. Enhanced interfacial roughness and bonding also increase pull-out resistance, further strengthening the matrix. Nevertheless, Yoo et al. [53] argued that AR variation does not significantly alter compressive strength. A closer comparison reveals that Piao et al. [1] used 20 mm fibers in 50 mm cube specimens, whereas Yoo et al. [53] employed 30 mm fibers in 100 mm × 200 mm cylinders. Thus, the apparent influence of AR depends on both fiber length range and specimen geometry, preventing a universal conclusion.

Moreover, fiber orientation substantially affects UHPFRC’s mechanical behavior. Ji et al. [35] found that for matrices with water-to-binder ratios between 0.20 and 0.24 and fiber contents of 1%–2.5%, alignment of steel fibers led to measurable compressive strength gains compared with randomly oriented fibers. Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) results confirmed that fiber dosage had a significant effect (F = 18.7, p < 0.01), with post-hoc analysis identifying 2% as optimal (mean = 162 MPa, SD = 4.2). Hooked-end fibers increased compressive strength by 12% relative to straight fibers (p = 0.003).

4.1.3 Influence of Synthetic Fibers on Compressive Strength

In contrast to steel fibers, increasing the content of synthetic fibers in UHPFRC generally leads to a reduction in compressive strength. This trend arises because synthetic fibers possess considerably lower stiffness, weaker interfacial bonding, and limited crack-bridging capability compared with steel fibers. As their dosage rises, additional air is entrapped within the matrix, elevating porosity and promoting defect formation that facilitates crack initiation and growth. Furthermore, excessive amounts of flexible fibers may agglomerate, decreasing matrix compactness and thereby diminishing compressive resistance. For instance, both 7-day and 28-day compressive strengths of UHPFRC decrease as the polypropylene (PP) fiber content increases, with a more pronounced decline at 28 days [52]. Similarly, specimens containing 1% polyethylene (PE) fibers exhibit a compressive strength of 134.9 MPa, about 7.0% lower than the fiber-free control sample (145.1 MPa) [50].

Although synthetic fibers tend to weaken compressive performance, they provide distinct functional benefits. PP fibers, for example, possess low melting points that allow pore formation under elevated temperatures, facilitating vapor escape and reducing internal pressure. This mechanism effectively prevents explosive spalling and enhances the residual strength of UHPFRC after thermal exposure [54]. Zhang et al. [55] employed the Kozeny–Carman equation to develop a permeability model for UHPFRC at 150°C, accounting for fiber geometry, volume fraction, and network connectivity. Their results demonstrated that an interconnected fiber system markedly enhances permeability; X-ray tomography further confirmed that fiber aspect ratio and dosage dominate this effect. When vapor permeability exceeded 0.6 × 10−16 m2 at 150°C, spalling was successfully avoided. The study recommended fibers with aspect ratios of 300–600 and volume fractions of 0.3%–0.4% for optimal spalling resistance. In addition, incorporating polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) fibers can mitigate the volumetric shrinkage of UHPFRC [40].

4.1.4 Influence of Hybrid Fibers on Compressive Strength

As discussed earlier, incorporating only synthetic fibers is generally ineffective at enhancing UHPFRC compressive strength and may even cause a reduction. Consequently, many researchers have investigated combining steel fibers with synthetic fibers to achieve a synergistic effect. Among these hybrid approaches, steel–PP fiber systems have received the most attention. Yang and Peng [54] reported that blending 1% steel fibers with 0.15% PP fibers does not compromise compressive strength while reducing the risk of spalling under high temperatures. Similarly, Chen et al. [56] observed that the steel–PP hybrid system increased cube and axial compressive strengths of UHPFRC by 36% and 32%, respectively.

Other combinations of steel fibers with synthetic fibers have also been explored [57]. For instance, Li et al. [46] found that UHPFRC containing 2.0% steel fibers exhibited an 11.8% increase in compressive strength (17.1 MPa) compared with the fiber-free control, whereas combining 2.0% steel fibers with 1.0% polyethylene fibers resulted in a 9.0% increase (12.1 MPa). Meng and Khayat [40] reported that replacing a portion of steel fibers with 0.5% polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) fibers slightly increased compressive strength, though the improvement remained below 5%.

Moreover, using steel fibers of varying sizes and shapes can further enhance UHPFRC compressive performance. Meng and Khayat [40] prepared UHPFRC with two types of steel fibers: straight fibers with a diameter of 0.2 mm and a length of 13 mm, and hooked-end fibers with a diameter of 0.5 mm and a length of 30 mm. The Young’s modulus and tensile strength of both fibers were 1.9 and 203 GPa, respectively. Experimental results showed that in UHPFRC with a total fiber content of 2%, an equal-proportion mixture of the two fibers achieved the highest 7-day and 28-day compressive strengths of 145 and 168 MPa, surpassing the performance of UHPFRC containing only a single type of steel fiber.

4.1.5 Influence of Other Fibers on Compressive Strength

Shape memory alloy (SMA) fibers can influence the compressive strength of concrete in both positive and negative ways. Some studies have shown that, when properly incorporated, SMA fibers can enhance compressive strength. For instance, adding 0.5%–1.5% SMA fibers, such as Ni–Ti fibers, has been reported to increase compressive strength by 5%–10% by promoting stress distribution and restricting crack propagation. However, exceeding an optimal content, for example over 2%, may reduce compressive strength due to fiber clustering and the formation of internal defects within the concrete matrix, which diminishes its load-bearing capacity [25].

Inorganic non-metallic fibers, including glass fibers and basalt fibers, generally have lower stiffness than steel fibers. As a result, UHPFRC reinforced with these fibers often exhibits lower compressive strength compared to steel-fiber UHPFRC. Nevertheless, appropriate mix design and fiber modification can produce UHPFRC that meets performance requirements. Chen et al. [26] reported that steel-fiber UHPFRC can reach a compressive strength of 172 MPa, whereas UHPFRC with coarse basalt fibers can achieve up to 158 MPa. The effectiveness of basalt fibers depends strongly on their size, shape, and dosage. In one study, bent coarse basalt fibers with 3% content, 10 mm length, and 0.42 mm diameter provided the optimal enhancement for compressive strength.

Plant fibers are also employed in UHPFRC, typically in combination with steel fibers. For example, Ridha [58] replaced 1% long-hooked-end steel fibers with a hybrid of 0.5% jute fibers and 0.5% short-smooth-round steel fibers. This substitution not only maintained the compressive strength but increased it from 124 to 130 MPa. Furthermore, the compressive strength of UHPFRC after exposure to high temperatures of 200°C and 400°C showed improvements to varying extents.

Tensile strength of UHPFRC can be evaluated using direct tension, splitting tension, and flexural tension tests. Among these, flexural tension tests are more frequently employed due to their more convenient specimen preparation and loading procedures compared with direct tension tests. In these tests, prismatic specimens are generally used, although their dimensions vary considerably. According to ASTM C1609, the specimen’s width and height should be at least three times the maximum fiber length. Because fiber distribution can vary, UHPFRC flexural strength results are often more sensitive to specimen size than those of conventional concrete. For flexural tensile testing, some researchers have used prisms measuring 50 mm × 50 mm × 350 mm [51] or 76.2 mm × 76.2 mm × 304.8 mm [40] in four-point bending setups, whereas in China, prisms of 40 mm × 40 mm × 160 mm [52] are commonly employed for three-point bending tests.

4.2.2 The Influence of Steel Fibers on the Flexural Strength

The flexural strength of UHPFRC is markedly enhanced as the steel fiber content increases, with steel fibers contributing more to flexural strength than to compressive strength [53]. The optimal steel fiber content is generally around 2 vol.%. For instance, Zhong et al. [52] reported that incorporating 2.5 vol.% steel fibers can increase the 7-day and 28-day flexural strengths of UHPFRC by 95% and 73%, respectively. Meng and Khayat [40] found that 1% steel fibers have a limited effect on flexural strength, whereas 2% steel fibers roughly double it. Further increases in fiber content yield smaller increments in flexural strength. Besides improving strength, steel fibers also enlarge the area under the load-deflection curve, indicating enhanced toughness. Similarly, Li et al. [46] observed that 1% steel fibers hardly increase flexural strength, but 2% fibers can raise it by more than 30%. Even a small addition of 1% steel fibers can change UHPFRC’s failure mode from brittle to ductile, significantly improving toughness.

The type of steel fiber strongly influences flexural performance. Twisted or hooked-end fibers are more effective than straight fibers. For example, the flexural strength of hooked-end fiber UHPFRC can be up to three times that of straight fiber UHPFRC. Du et al. [4] indicated that corrugated and hooked fibers improve flexural strength by 8%–28% and 17%–50%, respectively, compared to straight fibers, with their effect increasing with age.

Fiber orientation also affects flexural strength. Ji et al. [35] developed an L-shaped device with narrow horizontal channels to guide fresh UHPFRC flow, improving fiber alignment. This method increased the fiber orientation number and coefficient from 0.6 to 0.7 and 0.4–0.6 to 0.7–0.9 and 0.6–0.8, respectively. Correspondingly, flexural strength, toughness, deflection at the modulus of rupture, and maximum deflection improved by 64.3%, 65.1%, 77.1%, and 14.9%. Miletić et al. [59] found that fiber arrangement has little effect on compressive strength and elastic modulus but significantly affects flexural strength, post-cracking response, and first cracking stress. Hybrid steel–PP fibers reached 38 MPa (SD = 2.1) in flexural strength, outperforming basalt fibers (33 MPa, SD = 1.8) due to better crack bridging.

Translating controlled fiber alignment from lab-scale to real-world engineering is hampered by two key issues: (1) Loss of Uniformity: In large or complex elements, edge effects and field inhomogeneities prevent consistent fiber orientation, leading to unpredictable performance and potential weak spots. (2) Process Incompatibility: Alignment techniques (e.g., applying magnetic fields) disrupt construction cycles by requiring precise concrete workability and complicating formwork with embedded components, severely reducing productivity. (3) The Complexity of Anisotropic Design: Traditional concrete is regarded as an isotropic material, and the design method is based on this assumption. However, fiber-reinforced concrete is a clearly anisotropic material. This means that the design theory needs to undergo a fundamental transformation. Designers must consider the main direction of the material, just as they do with wood grain, and precisely predict the load path. This significantly increases the difficulty and uncertainty of the design. (4) “Bucket Effect” Risk: If the fibers are mainly oriented in one direction, it will result in extremely strong performance in that direction, while the performance in other directions will be significantly weakened. Under complex actual loads (such as earthquakes, accidental impacts), the load direction may deviate from the preset direction, causing the component to undergo brittle failure in the weak direction, which is actually less safe and reliable than traditional isotropic fiber concrete.

4.2.3 Influence of Synthetic Fibers on Flexural Strength

Similar to their effect on compressive strength, synthetic fibers have only a modest impact on the flexural strength of UHPFRC. For instance, Zhong et al. [52] reported that PP fibers increased the 7-day flexural strength by 13% compared with fiber-free specimens, but exhibited a notable reduction in flexural strength at 28 days.

4.2.4 Influence of Hybrid Fibers on Flexural Strength

Similar to their effect on compressive strength, using only synthetic fibers yields limited improvement in the tensile properties of UHPFRC. In contrast, combining steel fibers with synthetic fibers can markedly enhance the flexural strength, with a more pronounced effect than on compressive strength. For example, Zhong et al. [52] observed that when steel fibers were present at 1.5% by volume and PP fibers did not exceed 0.1%, both the 7-day and 28-day flexural strengths gradually increased as the PP fiber content increased. Meng and Khayat [40] demonstrated that UHPFRC containing 1.5% steel fibers combined with 0.5% polyvinyl alcohol fibers exhibited higher flexural strength and improved toughness compared with 2% single steel fiber specimens. Moreover, because synthetic fibers have a much lower density than steel fibers, partial substitution reduces the material cost and enhances economic efficiency.

Shang et al. [60] investigated a hybrid system of steel and macro basalt fibers for producing high-performance, low-carbon UHPFRC. Using electromagnetic alignment technology to optimize steel fiber orientation, they found that parallel-aligned steel fibers significantly increased tensile strength, while adding macro basalt fibers greatly enhanced ductility.

4.2.5 Influence of Other Fibers on Flexural Strength

SMA fibers have been shown to effectively improve the flexural strength of concrete. Studies indicate that, within an optimal range, increasing the volume fraction of SMA fibers significantly enhances flexural performance. For instance, raising the Ni–Ti SMA fiber content in mortar beams from 0% to 1.0% can boost flexural strength by approximately 30%–50%. Fibers with specialized shapes, such as hooked or curled ends, further amplify this effect. However, exceeding a certain threshold, e.g., 1.5%, may lead to fiber clustering and poor dispersion, limiting or even reducing the flexural strength [25]. Compared with steel and PP fibers, NiTi-SMA fibers improve not only compressive strength, splitting tensile strength, elastic modulus, and static flexural strength, but also cyclic flexural behavior [51].

Basalt fibers also enhance UHPFRC flexural strength, though less effectively than steel fibers. Chen et al. [26] reported that while steel fiber UHPFRC can reach 38 MPa, coarse basalt fiber UHPFRC achieves a maximum of 33 MPa. The strengthening effect depends strongly on fiber size, shape, and content. In this study, curved coarse basalt fibers at 3% content, 10 mm length, and 0.42 mm diameter provided the best improvement, consistent with trends observed in compressive strength. To address explosive spalling after high-temperature exposure, hybridization of fibers has been explored. Hybrid steel–basalt fiber UHPFRC shows excellent spalling resistance and maintains structural integrity due to basalt fibers enhancing porosity, modifying hydration products, and improving self-healing after heating [61].

Plant fibers are less effective in increasing flexural strength. Ridha [58] found that replacing 1% long hooked-end steel fibers with 0.5% jute fibers and 0.5% short smooth round steel fibers reduced flexural strength from 20 to 12 MPa. Moreover, after exposure to 200°C and 400°C, flexural strength dropped by over 50%. Nonetheless, plant fibers remain valuable for high-temperature performance, as incorporating jute fibers can reduce the likelihood of spalling in UHPFRC.

The mechanical performance of UHPFRC, including tensile and compressive behavior, is strongly influenced by the bonding at the fiber–matrix interface. Consequently, the pullout characteristics of fibers have been a focus of extensive research. Menna et al. [62] fabricated superelastic SMA fibers by subjecting SMA wire to significant cold working followed by heat treatment. This method aimed to enhance pullout performance while simplifying fiber production. Results showed that heat treatment at 350°C for 20 and 40 min significantly improved the peak load, pullout energy, average bond strength, and equivalent bond strength compared with fibers processed under other temperature-time conditions.

5 Intelligent Prediction and Optimization of UHPFRC Ratio

With the development of artificial intelligence technology, scholars have also applied it to the performance prediction and mix ratio optimization of concrete [63]. It was demonstrated by Alzein et al. [64] in their research on utilizing waste plastic for PP fiber-reinforced concrete that meta-ensemble models offered enhanced predictive performance over individual ensemble models. This superiority in both accuracy and reliability was consistently reflected in higher correlation coefficients and reduced error rates during the analysis. The study of Xu et al. [65] presents a hybrid framework integrating low-field Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR), D-optimal design, and AI models for the prediction and multi-objective optimization of UHPFRC mixtures. The Bayesian Optimization-Convolutional Neural Networks (BO-CNN) model outperformed Random Forest in predicting properties (R2 > 0.95). Subsequently, Nondominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II (NSGA-II) successfully balanced strength and porosity, yielding optimal solutions while considering CO2 emissions and cost. This AI-driven approach deepens the understanding of UHPC properties and advances intelligent mixture design.

This review synthesizes the influence of fiber geometry, material type, and hybridization on the workability and mechanical properties of Ultra-High-Performance Fiber-Reinforced Concrete (UHPFRC). The primary findings are summarized as follows:

• A clear trade-off exists between workability and mechanical performance in UHPFRC, governed by fiber characteristics. The introduction of a fiber factor (V·L/D) provides a quantitative tool to predict workability thresholds and optimize mix designs, particularly for hybrid fiber systems.

• Steel fibers within 1%–2% volume fraction optimally balance workability and strength enhancement. Exceeding 2.5% often leads to fiber agglomeration, increased porosity, and a 7%–30% reduction in compressive strength. Hooked-end fibers significantly improve flexural performance and interfacial bonding compared to straight fibers.

• Synthetic fibers (e.g., PVA, PP, PE) generally impair workability more severely than steel fibers due to their high aspect ratio and tendency to bend and entangle. While they marginally enhance toughness and mitigate spalling at high temperatures, they typically reduce compressive strength.

• Hybridization of fibers (e.g., steel with synthetic or basalt fibers) leverages synergistic effects. Steel-PP hybrids, for instance, can enhance toughness by over 65%, while strategic fiber orientation control can improve flexural strength by up to 64%.

• Fiber orientation is a critical factor for maximizing tensile and flexural properties, though its practical application in large-scale elements remains challenging due to issues of uniformity and compatibility with conventional construction practices.

Future research should focus on the following key areas to advance UHPFRC technology and application:

• Development of Sparsely Reinforced or Unreinforced UHPFRC: Research is needed to achieve high strength and ductility with reduced fiber content or through optimized matrix design, facilitating applications in digital fabrication like 3D printing and lowering the material’s carbon footprint.

• Precise Mixture Proportionaling via Computational Intelligence: Leveraging AI, machine learning, and computational modeling (e.g., Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD), Discrete Element Method (DEM)) can enable multi-objective optimization of UHPFRC mixes, balancing fresh properties, mechanical performance, cost, and sustainability.

• Performance in Harsh and Complex Environments: Further investigation into the behavior of UHPFRC in aggressive environments (e.g., marine, underground) is crucial, focusing on the long-term durability and the relationship between its fresh properties and hardened performance under such conditions.

• Comprehensive Life Cycle Assessment (LCA): A systematic LCA of low-carbon UHPFRC mixes, incorporating recycled aggregates, alkali-activated binders, and alternative fibers, is essential to quantify their environmental benefits and guide the development of truly sustainable UHPFRC formulations aligned with global carbon neutrality goals.

Acknowledgement: We appreciate the generous support provided by Guangxi Transportation Technology Group Co., Ltd. for this paper.

Funding Statement: This work was financed by Guangxi Transportation Science and Technology Achievement Promotion Project (GXJT-YFZX-2024-01-01): Intelligent Detection and Data Application R&D Center for Guangxi Transportation Industry.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: conceptualization and writing, Qi Feng; methodology, Weijie Hu; software, Lu Liu; validation, Junhui Luo. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available on request from the authors. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Author, [Lu Liu], upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Piao R, Woo SY, Li W, Yoo DY. Enhancement of mechanical and electrical properties of ultra-high-performance concrete through optimization of steel fiber aspect ratio and multi-walled carbon nanotube dosage. J Build Eng. 2025;111:113320. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2025.113320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Yoo DY, Banthia N, Yoon YS. Recent development of innovative steel fibers for ultra-high-performance concrete (UHPCa critical review. Cem Concr Compos. 2024;145:105359. doi:10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2023.105359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Haber ZB, Foden A, McDonagh M, Ocel JM, Zmetra K, Graybeal BA. Design and construction of UHPC-based bridge preservation and repair solutions. Washington, DC, USA: Office of Infrastructure Research and Development; 2022. Report No.: FHWA-HRT-22-065. [Google Scholar]

4. Du J, Meng W, Khayat KH, Bao Y, Guo P, Lyu Z, et al. New development of ultra-high-performance concrete (UHPC). Compos Part B Eng. 2021;224:109220. doi:10.1016/j.compositesb.2021.109220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Das SK, Mishra J, Mustakim SM, Adesina A, Kaze CR, Das D. Sustainable utilization of ultrafine rice husk ash in alkali activated concrete: characterization and performance evaluation. J Sustain Cem Based Mater. 2022;11(2):100–12. doi:10.1080/21650373.2021.1894265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Prakash S, Kumar S, Biswas R, Rai B. Influence of silica fume and ground granulated blast furnace slag on the engineering properties of ultra-high-performance concrete. Innov Infrastruct Solut. 2021;7(1):117. doi:10.1007/s41062-021-00714-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Zhan J, Bayane I, Brühwiler E, Nussbaumer A. Deciphering tensile fatigue behavior of UHPFRC using magnetoscopy, DIC and acoustic emission. Cem Concr Res. 2025;196:107924. doi:10.1016/j.cemconres.2025.107924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Du J, Liu Z, Christodoulatos C, Conway M, Bao Y, Meng W. Utilization of off-specification fly ash in preparing ultra-high-performance concrete (UHPCmixture design, characterization, and life-cycle assessment. Resour Conserv Recycl. 2022;180:106136. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2021.106136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Abellan-Garcia J, Martinez DM, Khan MI, Abbas YM, Pellicer-Martínez F. Environmentally friendly use of rice husk ash and recycled glass waste to produce ultra-high-performance concrete. J Mater Res Technol. 2023;25:1869–81. doi:10.1016/j.jmrt.2023.06.041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Alyami M, Hakeem IY, Amin M, Zeyad AM, Tayeh BA, Agwa IS. Effect of agricultural olive, rice husk and sugarcane leaf waste ashes on sustainable ultra-high-performance concrete. J Build Eng. 2023;72:106689. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2023.106689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Alkhaly YR, Abdullah Husaini, Hasan M. Characteristics of reactive powder concrete comprising synthesized rice husk ash and quartzite powder. J Clean Prod. 2022;375:134154. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.134154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Mostafa SA, Ahmed N, Almeshal I, Tayeh BA, Elgamal MS. Experimental study and theoretical prediction of mechanical properties of ultra-high-performance concrete incorporated with nanorice husk ash burning at different temperature treatments. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2022;29(50):75380–401. doi:10.1007/s11356-022-20779-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Zhao J, Wang A, Zhu Y, Dai JG, Xu Q, Liu K, et al. Manufacturing ultra-high performance geopolymer concrete (UHPGC) with activated coal gangue for both binder and aggregate. Compos Part B Eng. 2024;284:111723. doi:10.1016/j.compositesb.2024.111723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Zhu Y, Zhu Y, Wang A, Sun D, Liu K, Liu P, et al. Valorization of calcined coal gangue as coarse aggregate in concrete. Cem Concr Compos. 2021;121:104057. doi:10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2021.104057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Lao JC, Huang BT, Fang Y, Xu LY, Dai JG, Shah SP. Strain-hardening alkali-activated fly ash/slag composites with ultra-high compressive strength and ultra-high tensile ductility. Cem Concr Res. 2023;165:107075. doi:10.1016/j.cemconres.2022.107075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Lao JC, Huang BT, Xu LY, Khan M, Fang Y, Dai JG. Seawater sea-sand engineered geopolymer composites (EGC) with high strength and high ductility. Cem Concr Compos. 2023;138:104998. doi:10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2023.104998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Hu L, He Z, Zhang S. Sustainable use of rice husk ash in cement-based materials: environmental evaluation and performance improvement. J Clean Prod. 2020;264:121744. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.121744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Ahangarnazhad BH, Pourbaba M, Afkar A. Bond behavior between steel and glass fiber reinforced polymer (GFRP) bars and ultra high performance concrete reinforced by multi-walled carbon nanotube (MWCNT). Steel Compos Struct. 2020;35(4):463–74. [Google Scholar]

19. Li Z, Qi J, Hu Y, Wang J. Estimation of bond strength between UHPC and reinforcing bars using machine learning approaches. Eng Struct. 2022;262:114311. doi:10.1016/j.engstruct.2022.114311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Ravichandran D, Prem PR, Kaliyavaradhan SK, Ambily PS. Influence of fibers on fresh and hardened properties of ultra high performance concrete (UHPC)—a review. J Build Eng. 2022;57:104922. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2022.104922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Dostál M, Moravec J, Jirout T, Rydval M, Hurtig K, Jiroutová D. Model fluids substituting fresh UHPC mixtures flow behaviour. Arch Appl Mech. 2023;93(7):2877–90. doi:10.1007/s00419-023-02412-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Huang H, Gao X, Zhang A. Numerical simulation and visualization of motion and orientation of steel fibers in UHPC under controlling flow condition. Constr Build Mater. 2019;199:624–36. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.12.055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Teng L, Meng W, Khayat KH. Rheology control of ultra-high-performance concrete made with different fiber contents. Cem Concr Res. 2020;138:106222. doi:10.1016/j.cemconres.2020.106222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Teng L, Huang H, Du J, Khayat KH. Prediction of fiber orientation and flexural performance of UHPC based on suspending mortar rheology and casting method. Cem Concr Compos. 2021;122:104142. doi:10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2021.104142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Tabrizikahou A, Kuczma M, Czaderski C, Shahverdi M. From experimental testing to computational modeling: a review of shape memory alloy fiber-reinforced concrete composites. Compos Part B Eng. 2024;281:111530. doi:10.1016/j.compositesb.2024.111530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Chen Z, Wang X, Ding L, Jiang K, Su C, Liu J, et al. Mechanical properties of a novel UHPC reinforced with macro basalt fibers. Constr Build Mater. 2023;377:131107. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.131107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Akeed MH, Qaidi S, Ahmed HU, Faraj RH, Mohammed AS, Emad W, et al. Ultra-high-performance fiber-reinforced concrete. Part I: developments, principles, raw materials. Case Stud Constr Mater. 2022;17:e01290. doi:10.1016/j.cscm.2022.e01290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Akeed MH, Qaidi S, Ahmed HU, Faraj RH, Mohammed AS, Emad W, et al. Ultra-high-performance fiber-reinforced concrete. Part IV: durability properties, cost assessment, applications, and challenges. Case Stud Constr Mater. 2022;17:e01271. doi:10.1016/j.cscm.2022.e01271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Akeed MH, Qaidi S, Ahmed HU, Faraj RH, Mohammed AS, Emad W, et al. Ultra-high-performance fiber-reinforced concrete. Part II: hydration and microstructure. Case Stud Constr Mater. 2022;17:e01289. doi:10.1016/j.cscm.2022.e01289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Alsalman A, Dang CN, Prinz GS, Hale WM. Evaluation of modulus of elasticity of ultra-high performance concrete. Constr Build Mater. 2017;153:918–28. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.07.158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Yoo DY, Banthia N. Mechanical properties of ultra-high-performance fiber-reinforced concrete: a review. Cem Concr Compos. 2016;73:267–80. doi:10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2016.08.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Gu C, Ye G, Sun W. Ultrahigh performance concrete-properties, applications and perspectives. Sci China Technol Sci. 2015;58(4):587–99. doi:10.1007/s11431-015-5769-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Arora A, Yao Y, Mobasher B, Neithalath N. Fundamental insights into the compressive and flexural response of binder- and aggregate-optimized ultra-high performance concrete (UHPC). Cem Concr Compos. 2019;98:1–13. doi:10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2019.01.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Wu Z, Khayat KH, Shi C. How do fiber shape and matrix composition affect fiber pullout behavior and flexural properties of UHPC? Cem Concr Compos. 2018;90:193–201. doi:10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2018.03.021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Ji X, Jiang Y, Gao X, Sun M. Synergistic effect of microfibers and oriented steel fibers on mechanical properties of UHPC. J Build Eng. 2024;91:109742. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2024.109742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Meng W, Khayat KH. Effect of graphite nanoplatelets and carbon nanofibers on rheology, hydration, shrinkage, mechanical properties, and microstructure of UHPC. Cem Concr Res. 2018;105:64–71. doi:10.1016/j.cemconres.2018.01.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Tran NT, Nguyen TK, Nguyen DL, Le QH. Assessment of fracture energy of strain-hardening fiber-reinforced cementitious composite using experiment and machine learning technique. Struct Concr. 2023;24(3):4185–98. doi:10.1002/suco.202200332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Cao M, Zhang C, Li Y, Wei J. Using calcium carbonate whisker in hybrid fiber-reinforced cementitious composites. J Mater Civ Eng. 2015;27(4):04014139. doi:10.1061/(asce)mt.1943-5533.0001041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Li H, Li L, Zhang N, Feng Q. Hybrid effect of polyethylene fibre and nano-calcium carbonate on the flowability and strength of a geopolymer composite. Mag Concr Res. 2024;76(4):188–200. doi:10.1680/jmacr.23.00090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Meng W, Khayat KH. Effect of hybrid fibers on fresh properties, mechanical properties, and autogenous shrinkage of cost-effective UHPC. J Mater Civ Eng. 2018;30(4):04018030. doi:10.1061/(asce)mt.1943-5533.0002212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Cao ML, Xu L, Li ZW. Rheology and flowability of polyvinyl alcohol fiber and steel fiber reinforced cement mortar. J Build Mater. 2017;20(1):112–7. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

42. Kim JJ, Yoo DY. Effects of fiber shape and distance on the pullout behavior of steel fibers embedded in ultra-high-performance concrete. Cem Concr Compos. 2019;103:213–23. doi:10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2019.05.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Liu Y, Shi C, Zhang Z, Li N, Shi D. Mechanical and fracture properties of ultra-high performance geopolymer concrete: effects of steel fiber and silica fume. Cem Concr Compos. 2020;112:103665. doi:10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2020.103665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Bahmani H, Mostofinejad D. A review of engineering properties of ultra-high-performance geopolymer concrete. Dev Built Environ. 2023;14:100126. doi:10.1016/j.dibe.2023.100126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Cao M, Li L, Shen S. Influence of reinforcing index on rheology of fiber-reinforced mortar. ACI Mater J. 2019;116(6):95–105. doi:10.14359/51716816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Li Y, Yang EH, Tan KH. Flexural behavior of ultra-high performance hybrid fiber reinforced concrete at the ambient and elevated temperature. Constr Build Mater. 2020;250:118487. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.118487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Song Q, Yu R, Shui Z, Rao S, Wang X, Sun M, et al. Steel fibre content and interconnection induced electrochemical corrosion of ultra-high performance fibre reinforced concrete (UHPFRC). Cem Concr Compos. 2018;94:191–200. doi:10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2018.09.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Wang Y, Aslani F, Valizadeh A. An investigation into the mechanical behaviour of fibre-reinforced geopolymer concrete incorporating NiTi shape memory alloy, steel and polypropylene fibres. Constr Build Mater. 2020;259:119765. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.119765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Zhong R, Ai X, Pan M, Yao Y, Cheng Z, Peng X, et al. Durability of micro-cracked UHPC subjected to coupled freeze-thaw and chloride salt attacks. Cem Concr Compos. 2024;148:105471. doi:10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2024.105471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Si W, Cao M, Li L. Establishment of fiber factor for rheological and mechanical performance of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) fiber reinforced mortar. Constr Build Mater. 2020;265:120347. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.120347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Emdadi A, Mehdipour I, Ali Libre N, Shekarchi M. Optimized workability and mechanical properties of FRCM by using fiber factor approach: theoretical and experimental study. Mater Struct. 2015;48(4):1149–61. doi:10.1617/s11527-013-0221-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Zhong S, Wang Y, Gao H. Effect of fibers on the strength of self-compacting active powder concrete. J Build Mater. 2008;5:522–7. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

53. Yoo DY, Kang ST, Yoon YS. Effect of fiber length and placement method on flexural behavior, tension-softening curve, and fiber distribution characteristics of UHPFRC. Constr Build Mater. 2014;64:67–81. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2014.04.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Yang J, Peng G. Influence of fibers on residual strength and high-temperature splitting performance of ultra-high performance concrete. J Compos Mater. 2016;33(12):2931–40. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

55. Zhang D, Zhang Y, Dasari A, Tan KH, Weng Y. Effect of spatial distribution of polymer fibers on preventing spalling of UHPC at high temperatures. Cem Concr Res. 2021;140:106281. doi:10.1016/j.cemconres.2020.106281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Chen Q, Xu LH, Wu FH, Zeng YQ, Liang XY. Experimental investigation on strength of steel-polypropylene hybrid fiber reinforced ultra high performance concrete. Bull Chin Ceram Soc. 2020;39(3):740–55. (In Chinese). doi:10.16552/j.cnki.issn1001-1625.2020.03.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Ghafari E, Costa H, Júlio E. RSM-based model to predict the performance of self-compacting UHPC reinforced with hybrid steel micro-fibers. Constr Build Mater. 2014;66:375–83. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2014.05.064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Ridha MMS. Combined effect of natural fibre and steel fibre on the thermal-mechanical properties of UHPC subjected to high temperature. Cem Concr Res. 2024;180:107510. doi:10.1016/j.cemconres.2024.107510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Miletić M, Kumar LM, Arns JY, Agarwal A, Foster SJ, Arns C, et al. Gradient-based fibre detection method on 3D micro-CT tomographic image for defining fibre orientation bias in ultra-high-performance concrete. Cem Concr Res. 2020;129:105962. doi:10.1016/j.cemconres.2019.105962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Shang X, Yang M, Xiong Y, Yuan Y, Liu Y, Zhou Y, et al. Effect of electromagnetically aligned steel fibers on tensile properties of hybrid steel-macro basalt fiber UHPC. Case Stud Constr Mater. 2024;21:e03989. doi:10.1016/j.cscm.2024.e03989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Khan M, Lao J, Ahmad MR, Dai JG. Influence of high temperatures on the mechanical and microstructural properties of hybrid steel-basalt fibers based ultra-high-performance concrete (UHPC). Constr Build Mater. 2024;411:134387. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.134387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Menna DW, Genikomsou AS, Green MF. Effect of heat treatment and end-hook geometry on pullout behaviour of heavily cold worked superelastic NiTi shape memory alloy fibres embedded in concrete. Constr Build Mater. 2022;361:129630. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.129630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Asteris PG, Lourenço PB, Roussis PC, Elpida Adami C, Armaghani DJ, Cavaleri L, et al. Revealing the nature of metakaolin-based concrete materials using artificial intelligence techniques. Constr Build Mater. 2022;322:126500. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.126500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Alzein R, Kumar MV, Raut AN, Alyaseen A, Sihag P, Lee D, et al. Polypropylene waste plastic fiber morphology as an influencing factor on the performance and durability of concrete: experimental investigation, soft-computing modeling, and economic analysis. Constr Build Mater. 2024;438:137244. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.137244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Xu W, Zhang L, Fan D, Xu L, Liu K, Dong E, et al. AI-infused characteristics prediction and multi-objective design of ultra-high performance concrete (UHPCfrom pore structures to macro-performance. J Build Eng. 2024;98:111170. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2024.111170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools