Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Automatic Recognition Algorithm of Pavement Defects Based on S3M and SDI Modules Using UAV-Collected Road Images

1 Yunnan Transportation Science Research Institute Co., Ltd., Kunming, 650200, China

2 Faculty of Transportation Engineering, Kunming University of Science and Technology, Kunming, 650500, China

* Corresponding Author: Fengxiang Guo. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: AI-Enhanced Low-Altitude Technology Applications in Structural Integrity Evaluation and Safety Management of Transportation Infrastructure Systems)

Structural Durability & Health Monitoring 2026, 20(1), . https://doi.org/10.32604/sdhm.2025.068987

Received 11 June 2025; Accepted 18 July 2025; Issue published 08 January 2026

Abstract

With the rapid development of transportation infrastructure, ensuring road safety through timely and accurate highway inspection has become increasingly critical. Traditional manual inspection methods are not only time-consuming and labor-intensive, but they also struggle to provide consistent, high-precision detection and real-time monitoring of pavement surface defects. To overcome these limitations, we propose an Automatic Recognition of Pavement Defect (ARPD) algorithm, which leverages unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV)-based aerial imagery to automate the inspection process. The ARPD framework incorporates a backbone network based on the Selective State Space Model (S3M), which is designed to capture long-range temporal dependencies. This enables effective modeling of dynamic correlations among redundant and often repetitive structures commonly found in road imagery. Furthermore, a neck structure based on Semantics and Detail Infusion (SDI) is introduced to guide cross-scale feature fusion. The SDI module enhances the integration of low-level spatial details with high-level semantic cues, thereby improving feature expressiveness and defect localization accuracy. Experimental evaluations demonstrate that the ARPD algorithm achieves a mean average precision (mAP) of 86.1% on a custom-labeled pavement defect dataset, outperforming the state-of-the-art YOLOv11 segmentation model. The algorithm also maintains strong generalization ability on public datasets. These results confirm that ARPD is well-suited for diverse real-world applications in intelligent, large-scale highway defect monitoring and maintenance planning.Keywords

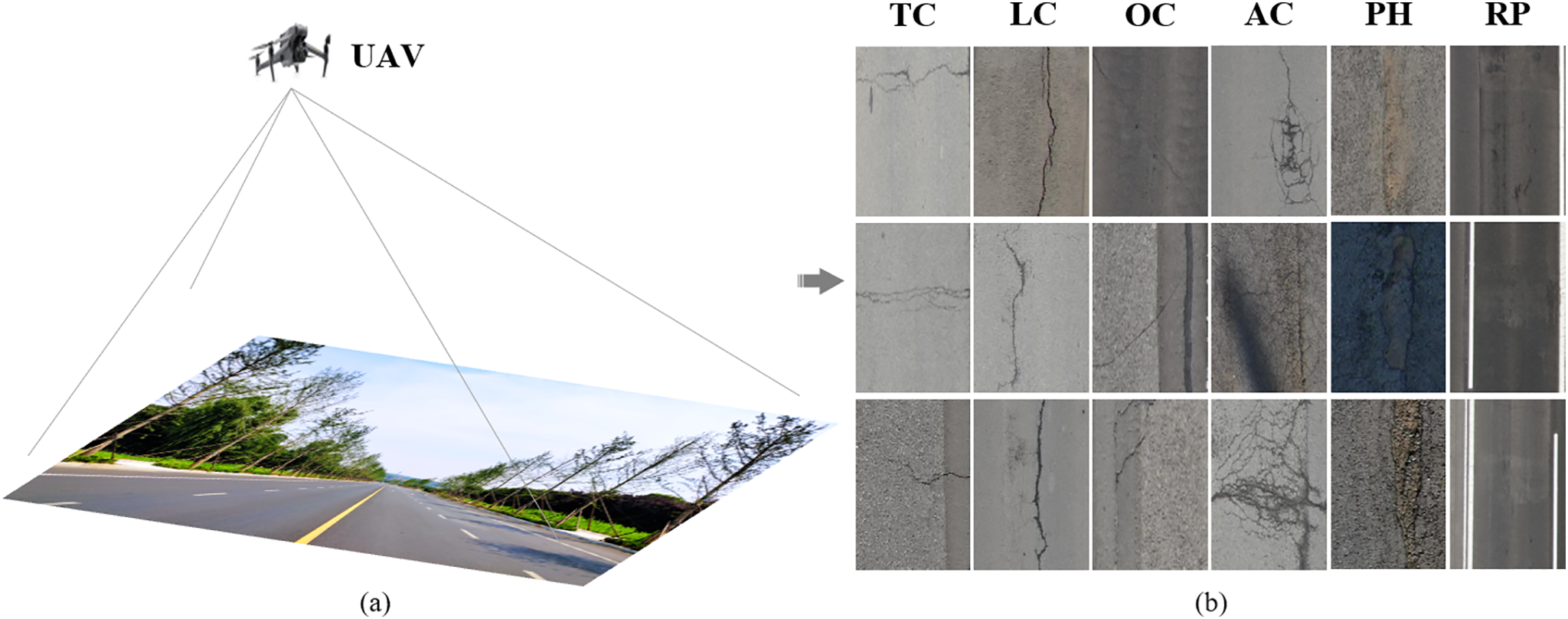

As critical components of national infrastructure, roads play a vital role in daily transportation and freight logistics. The safety, comfort, and operational efficiency have a direct impact on social stability and economic development. With the continuous growth in travel demand, pavement surfaces are increasingly subject to various forms of defects, such as longitudinal cracks (LC), transverse cracks (TC), oblique cracks (OC), alligator cracks (AC), potholes (PH), and asphalt repairs (RP), as illustrated in Fig. 1. Under repeated loading, these defects can evolve into more severe issues such as through-cracks, rutting, spalling, and structural failure, posing significant safety risks [1]. If not addressed in a timely manner, pavement deterioration may lead to serious traffic accidents and endanger public safety. Therefore, developing efficient and accurate pavement inspection methods is of great significance for enhancing transportation safety [2].

Figure 1: UAV-based pavement surface defect inspection. (a) UAV aerial view. (b) Main defects

Traditional road inspection methods still rely heavily on manual visual assessment, which is not only inefficient but also poses safety risks and introduces significant human error, falling short of the demands of modern transportation systems [3]. Although road inspection vehicles equipped with high-resolution cameras and sensors have been developed, their limited field of view results in blind spots, preventing comprehensive coverage. Moreover, the data collected by such vehicles still require manual filtering and analysis, which remains time-consuming and labor-intensive [4]. Fortunately, unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) technology offers a promising alternative for road maintenance due to its wide field of view, wide coverage, and low cost. UAVs equipped with high-resolution cameras and infrared sensors enable fast and efficient detection of pavement defects. Compared to traditional manual inspection, UAV-based approaches significantly improve detection efficiency and accuracy while reducing personnel risks, making them a research hotspot in pavement defect detection [5]. However, manually reviewing large volumes of UAV imagery remains laborious, highlighting the urgent need for an automatic defect recognition algorithm based on UAV road surface images.

Over the past decades, road inspection methods have mainly evolved through two technological stages: (1) Image Processing (IP) Techniques: Early researchers developed defect detection methods using traditional IP algorithms such as thresholding [6], wavelet transforms [7], and edge computing [8,9]. While these techniques provided quick results, they required manual parameter tuning and lacked generalization capabilities. (2) Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs): CNN-based methods leverage the deep representation capabilities of neural networks to automatically learn multi-level image features, enabling semantic understanding of image content [10–12]. Compared to IP techniques, CNNs exhibit superior performance in identifying complex pavement structures and subtle defects. These methods are typically categorized into two types: Two-stage approaches based on region proposal networks [13–15], which deliver high accuracy but suffer from low inference speed. Single-stage approaches based on direct bounding box regression [16–18], which offer faster inference at the cost of slight accuracy degradation and are widely adopted in current object detection tasks. For instance, Shan et al. [19] designed an asymmetric loss function tailored for road crack recognition and implemented it within a U-Net framework, achieving precise crack pattern extraction on UAV datasets. Similarly, Tse et al. [20] employed a mean Intersection over Union (mIoU)-based loss function within U-Net to control gradient descent, attaining state-of-the-art performance in UAV-based crack detection. However, these methods primarily focus on crack features while neglecting other critical defects such as alligator cracking or potholes. To address the multi-defect detection challenge, Feng et al. [21] utilized a Context Encoder Network (CE-Net)-based semantic segmentation model for simultaneous detection and segmentation of various pavement defects, enabling comprehensive health assessments. Dugalam and Prakash [22] proposed a UAV LiDAR and Random Forest-based algorithm that achieved promising results for subsidence and pothole detection. Nonetheless, the precision and efficiency of these models still have room for improvement in complex multi-defect pavement scenarios.

In recent years, visual methodologies based on emerging CNN paradigms such as Transformers and Mamba have been successfully applied to transportation infrastructure inspection and broader structural health monitoring tasks [23,24]. Transformer-based models (e.g., Vision Transformer [25], MobileNet [26], and U-Net [27]) leverage self-attention mechanisms to capture global context and flexibly model long-range dependencies between features. However, these models are inherently limited by their high computational complexity. Furthermore, their dependency on large-scale training datasets and resource-intensive hardware significantly impairs their real-time applicability. To overcome these limitations, the Mamba architecture, built upon the Selective State Space Model (S3M), introduces explicit state variables to adaptively model input sequences [28]. This approach not only effectively captures long-term temporal dependencies but also reduces redundant information, thereby achieving outstanding performance in continuous-time sequence modeling tasks. For example, Han et al. [29] developed MambaCrackNet, which integrates residual vision Mamba blocks for pixel-level road crack segmentation, achieving strong results on public datasets. Similarly, Zhu et al. [30] proposed MSCrackMamba, a two-stage crack detection paradigm with Vision Mamba as its backbone, reporting a 3.55% improvement in mIoU over baseline models.

Despite these promising advances, substantial challenges persist in transitioning these methods to real-world deployment scenarios. Specifically, existing studies continue to face difficulties in addressing complex environmental variations, meeting real-time processing constraints, and detecting fine-grained or small-scale defects. In the context of UAV-based road surface defect detection, current CNN- and Transformer-based methods encounter several notable challenges: (1) Extremely limited semantic information: Although UAV imagery typically offers ultra-high resolution, pavement defects occupy only a minimal portion of the pixel space, resulting in sparse semantic cues for effective feature extraction. (2) Significant variation in object scale: Pavement defects encompass a wide range of categories, each with differing physical dimensions. (3) Irregular and sparsely distributed targets: As the most prevalent defect type, cracks tend to be narrow, elongated, and irregularly distributed. From a top-down UAV perspective, their spatial arrangement lacks predictable patterns, complicating detection and modeling. These challenges highlight the need for more robust and efficient detection frameworks capable of operating under real-world constraints while maintaining high precision and generalizability.

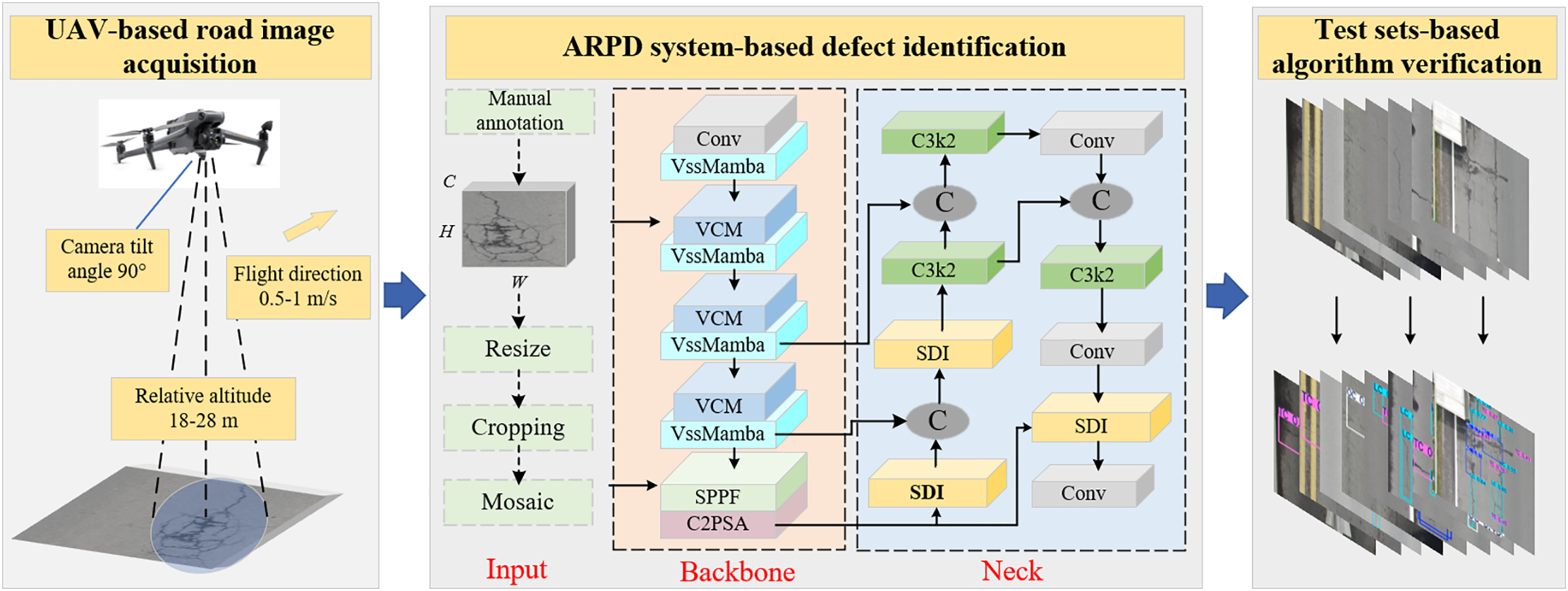

To address the aforementioned challenges and limitations, inspired by pioneering research, this study develops an Automatic Recognition of Pavement Defects (ARPD) algorithm based on UAV-acquired imagery. As illustrated in Fig. 2, the ARPD framework consists of three major stages. First, the UAV-PDD2023 dataset [1] is utilized and randomly divided into training, validation, and testing subsets. The training and validation sets include paired images and label files, while the testing set contains only images with no duplication across datasets. Second, a backbone network based on the Selective State Space Model (S3M) [28] is integrated into ARPD for fine-grained feature extraction. This is followed by a Semantic and Detail Information (SDI)-based neck module [27], which performs multi-level feature fusion using the training and validation sets. Finally, the algorithm’s generalization and real-time performance are evaluated through inference on both the new RDD2022 dataset [31] and the designated testing set.

Figure 2: The overview of ARPD algorithm

The main contributions and innovations of this study are as follows:

(1) An automatic multi-class pavement surface defect recognition model based on a Selective State Space Model (S3M) and Semantics and Detail Infusion (SDI) is developed, achieving promising results on UAV-perspective datasets.

(2) An S3M-based backbone is integrated into the model to extract fine-grained features through temporal state updates and Zero-Order Hold (ZOH), enabling efficient long-range dependency modeling among spatially discrete surface defects.

(3) Additionally, the architecture incorporates a lightweight neck module with skip connections, which applies both spatial and channel-wise attention mechanisms to effectively integrate semantic cues at multiple scales for improved defect recognition accuracy.

As shown in Fig. 2, the ARPD algorithm consists of three steps:

• UAV-Based Pavement Dataset Construction: As illustrated in Fig. 2, the UAV-PDD2023 dataset is constructed using aerial images captured by unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs). The dataset is randomly divided into training, validation, and testing subsets to ensure diversity and independence across sets.

• Pavement Defect Recognition: After undergoing preprocessing procedures (including resizing, random cropping, and Mosaic augmentation [17]), the dataset is fed into the ARPD algorithm. Specifically, the ARPD integrates a Selective State Space Model (S3M)-based backbone for adaptive long-range dependency modeling, which effectively captures edge semantic information of slender and small-scale defects such as cracks. Additionally, a Semantic and Detail Information (SDI)-enhanced neck module is employed for multi-scale feature fusion. A hybrid loss function is adopted to guide gradient propagation during training, enhancing the algorithm’s ability to detect diverse defect types.

• System Validation on Test and Public Datasets: The testing set and the public dataset RDD-2022, both containing only unlabeled images and excluded from the training process, are used to validate the ARPD algorithm. This evaluation demonstrates the algorithm’s generalization ability and robustness under real-world conditions.

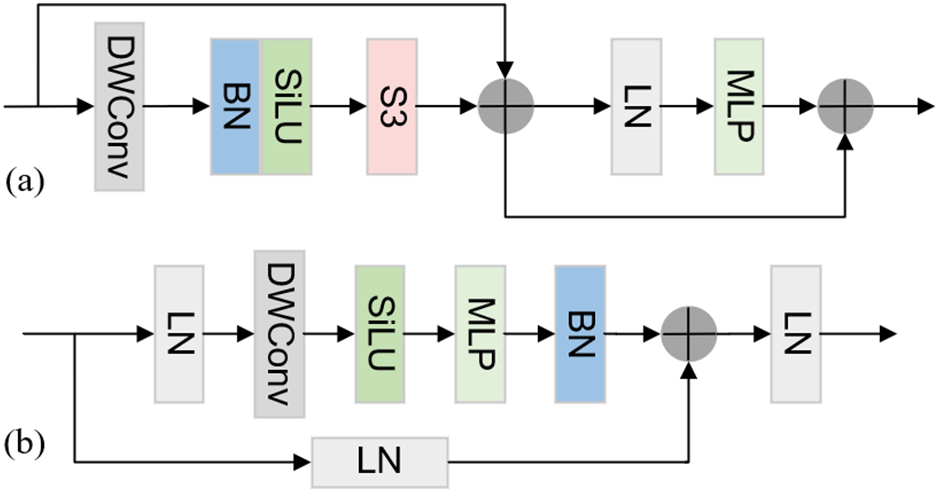

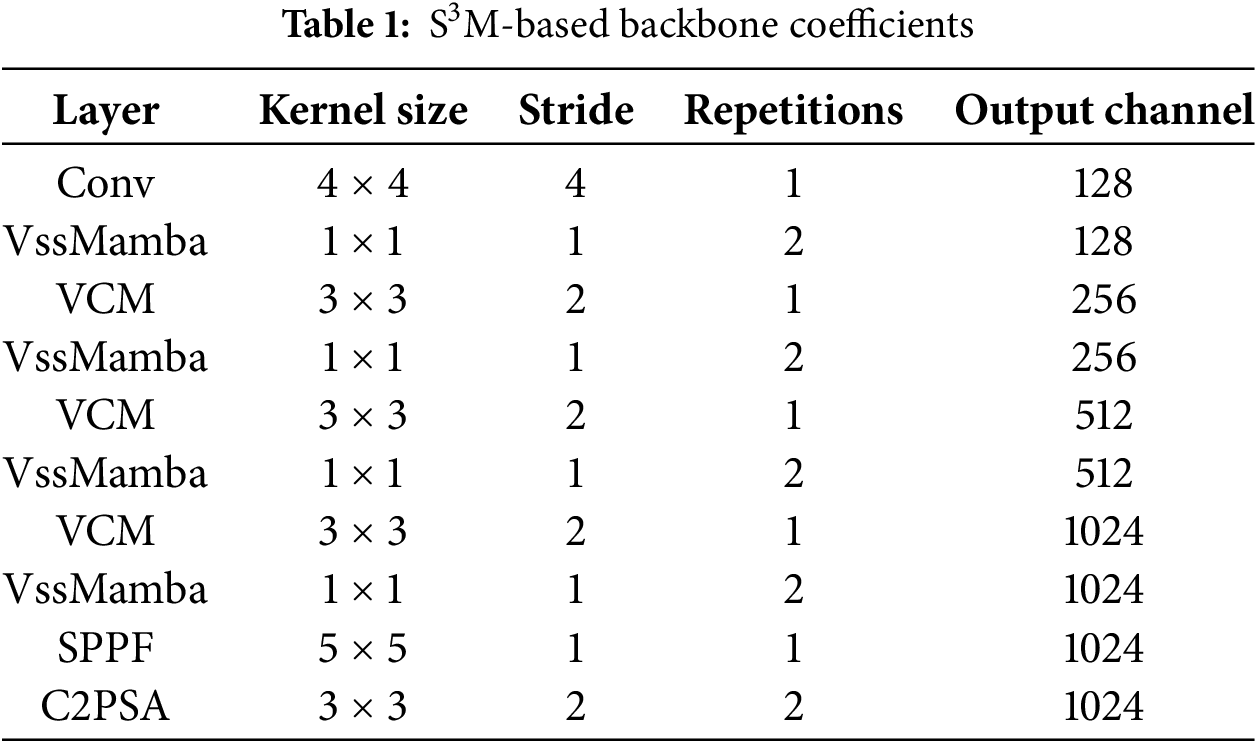

As illustrated in Fig. 3, the backbone of the ARPD algorithm integrates four key modules: VssMamba, VCM, SPPF, and C2PSA. The detailed configuration parameters of the backbone are presented in Table 1.

(1) VssMamba (Vision State Space Mamba) Module: As shown in Fig. 3, the VssMamba module incorporates Depthwise Convolution (DWConv) [32] for enhanced feature extraction at the input stage. This design enables the network to capture deeper and more expressive feature representations. To maintain efficiency and stability during training and inference, Batch Normalization (BN) and Layer Normalization (LN) are employed. The computation is governed by the following equations:

Figure 3: VssMamba module. (a) VssMamba block. (b) S3 block. Note that Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) represents multi-layer perceptron, and ‘+’ represents Concat concatenation

The S3 (Select State Space) module maps a univariate input sequence x(t) ∈ R to an output sequence y(t) via an implicit intermediate hidden state h(t) ∈ RN, as defined by the following first-order differential equation:

where

where

(2) Vision Clue Merge (VCM) Module: Although CNN and Transformer-based architectures typically utilize convolution operations for downsampling, directional feature scanning may introduce interference during multi-path extraction. To address this issue, VMamba [33] employs 1 × 1 convolutions for dimensionality reduction, while MambaYOLO [34] utilizes 4× compressed pointwise convolutions for downsampling. Inspired by these methods, the proposed VCM module adopts a 3 × 3 convolution with stride 2 for spatial downsampling and complements it with pointwise convolution to preserve informative clues during resolution reduction.

(3) Spatial Pyramid Pooling Fast (SPPF) Module: A lightweight adaptation of spatial pyramid pooling, SPPF module [17] is designed to capture multi-scale features at the end of the backbone. By applying multiple max-pooling operations (typically with a 5 × 5 kernel) at different receptive field scales, it enables hierarchical feature aggregation, which is particularly advantageous for scenarios with high object scale variance. For a given input feature map

(4) Compressed Channel-Wise Partial Self-Attention (C2PSA) Module: The C2PSA module combines channel and spatial attention mechanisms in a parallel structure to improve the representational power of convolutional blocks. Originally introduced in YOLOv11 [17] as an enhancement to YOLOv8, C2PSA selectively emphasizes informative feature channels and spatial locations through attention weighting. In this study, we incorporate C2PSA into the final stage of the ARPD backbone, aiming to further improve its performance in complex pavement imagery. Given an input feature map X, the output Xo is computed as:

where

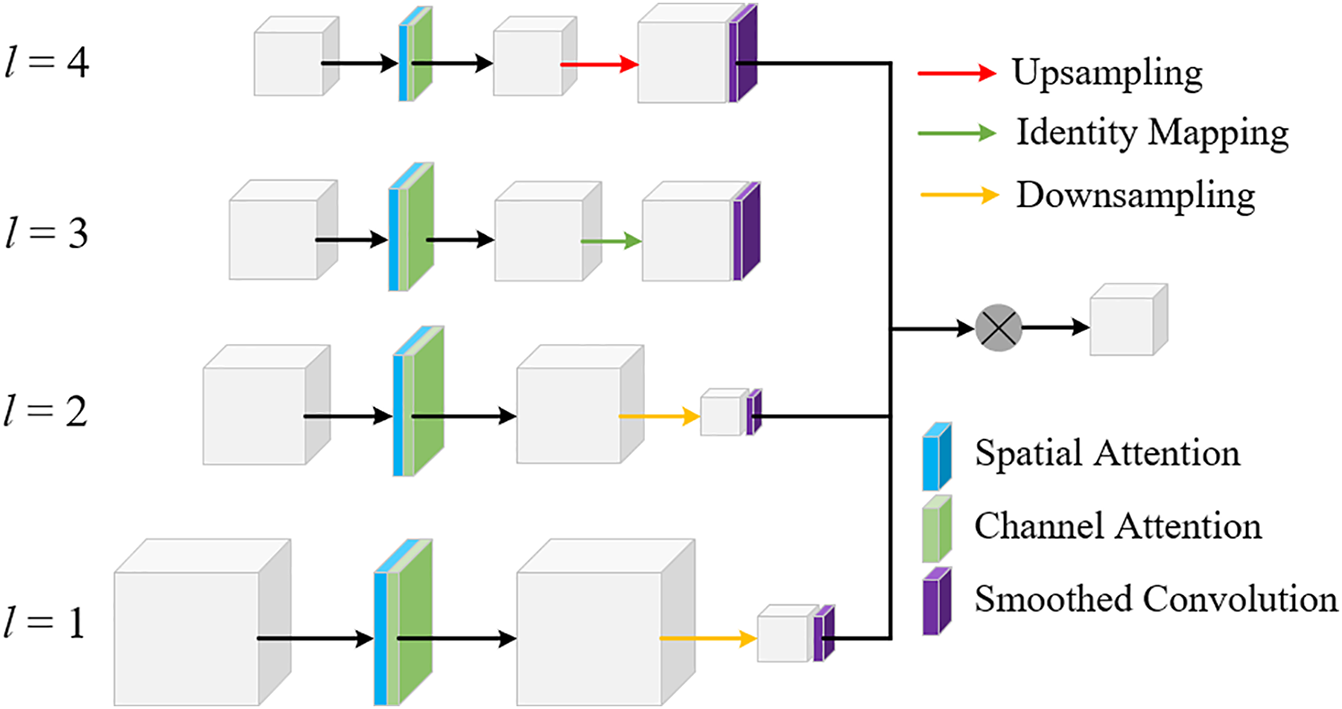

Existing neck structures predominantly rely on single-task feature pyramid networks (FPNs) to further process and enhance the features extracted by the backbone. In multi-scale object detection, classical backbone-neck-head architectures typically adopt FPN or Path Aggregation Network (PAN) for feature fusion, which have demonstrated promising results in transportation infrastructure maintenance scenarios. However, such neck designs often restrict inter-layer information transmission to intermediate layers only. To address this limitation, this study employs a lightweight skip connection-based neck structure for Semantics and Detail Infusion (SDI) [27], enabling more effective fusion of multi-scale pavement defect features. As illustrated in Fig. 4, a Transformer encoder is first applied to extract multi-level feature maps and align their output channels. For the i-th feature map, higher-level features (containing richer semantic information) and lower-level features (capturing finer details) are explicitly injected via simple Hadamard product operations, thereby enhancing both semantic and detailed representations of the i-th feature layer. The refined features are subsequently passed into a decoder for resolution reconstruction and segmentation.

Figure 4: The structure of SDI module

Given the input feature map

where

where

where

where

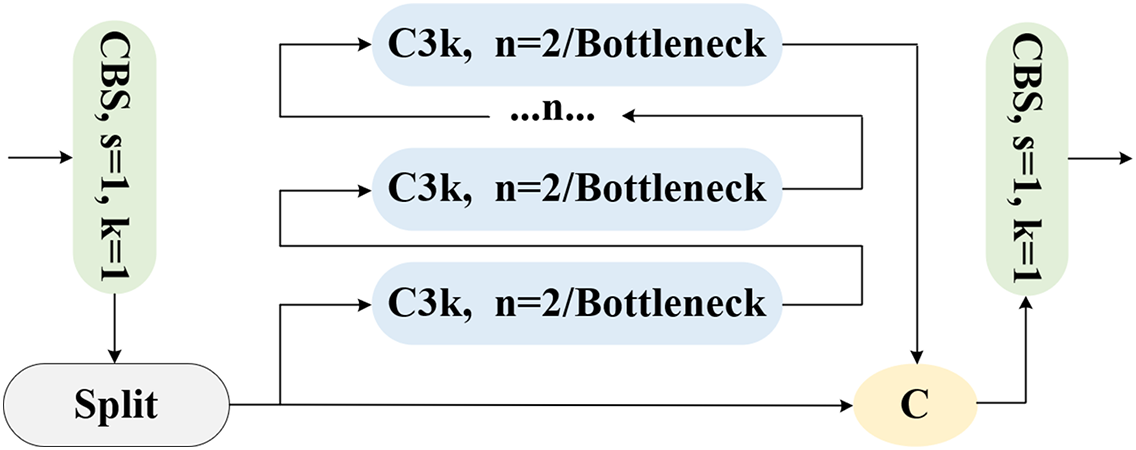

In addition, inspired by the state-of-the-art object detection advancements in YOLOv11, the C3k2 module, which integrates deformable convolutions and bottleneck enhancements, is incorporated into the neck of the ARPD algorithm to better address multi-scale pavement defect detection. As shown in Fig. 5, C3k2 employs CBS blocks with deformable convolutions of various kernel sizes (e.g., 3 × 3, 5 × 5), allowing the model to extract features across multiple scales and better capture complex spatial characteristics.

Figure 5: The C3k2 module

The APRD algorithm employs a hybrid loss function to regulate gradient updates, consisting of a classification loss

where

The classification loss typically adopts Binary Cross-Entropy (BCE), which measures the difference between the predicted class probability pi and the ground truth label yi for each predicted box [16]. The formula for classification loss is expressed as:

The regression loss is based on Complete Intersection over Union (CIoU), which evaluates the discrepancy between the predicted and ground truth bounding boxes in terms of center point coordinates, width, and height. For each predicted box, the IoU is calculated to derive the loss. The CIoU loss can be formulated as:

where ρ(

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed model, ablation studies are first conducted on the backbone and neck structure. Subsequently, the model is compared with current state-of-the-art (SOTA) object detection methods on the same dataset. Finally, visualized results on the test set are presented to further verify the model’s performance.

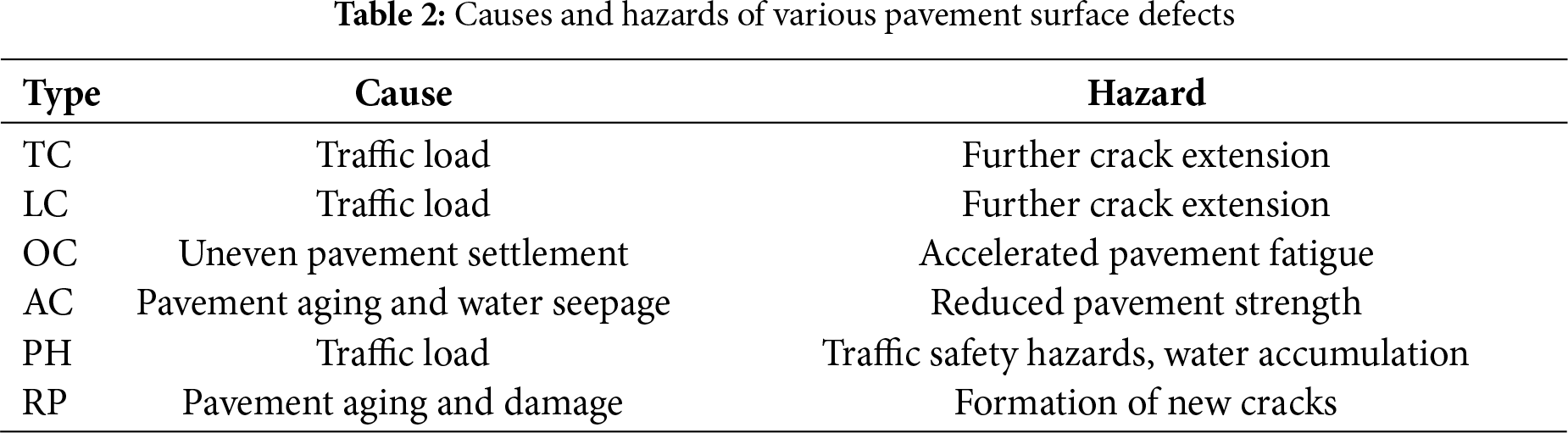

3.1 Dataset and Training Details

As described above, the experimental data are sourced from the publicly available UAV-PDD2023 dataset [1], captured by a downward-facing camera mounted on a UAV flying steadily above road surfaces. A total of 2000 images are used for model training, which are randomly split into training, validation, and test sets in a 7:2:1 ratio, ensuring no image overlap across subsets. The dataset is categorized into six defect types based on visual characteristics: longitudinal cracks (LC), transverse cracks (TC), oblique cracks (OC), alligator cracks (AC), potholes (PH), and repairs (RP). The causes and potential hazards of each type are detailed in Table 2. To further assess generalization and real-time capabilities, inference is also performed on the RDD2022 dataset [31] and the test set.

The APRD model is trained, validated, and tested on an Ubuntu 22.04 desktop equipped with an Intel Core i7-12700 CPU and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3060 GPU. Key training parameters include a learning rate of 0.01 for balancing convergence speed and stability, and a weight decay of 0.0005 to prevent overfitting. A fixed momentum value of 0.937 is used to enhance gradient descent efficiency. The model is trained for 300 epochs with a batch size of 16 to ensure stability and thorough convergence.

In the comparative experiments, precision (P), recall (R), and mean Average Precision (mAP) are used as evaluation metrics. Precision measures the proportion of correctly identified instances among all predicted positive instances, while recall evaluates the model’s ability to correctly classify relevant instances. The definitions are as follows:

where TP, FP, and FN represent true positives (positive samples correctly predicted as positive), false positives (negative samples incorrectly predicted as positive), and false negatives (positive samples incorrectly predicted as negative), respectively. The

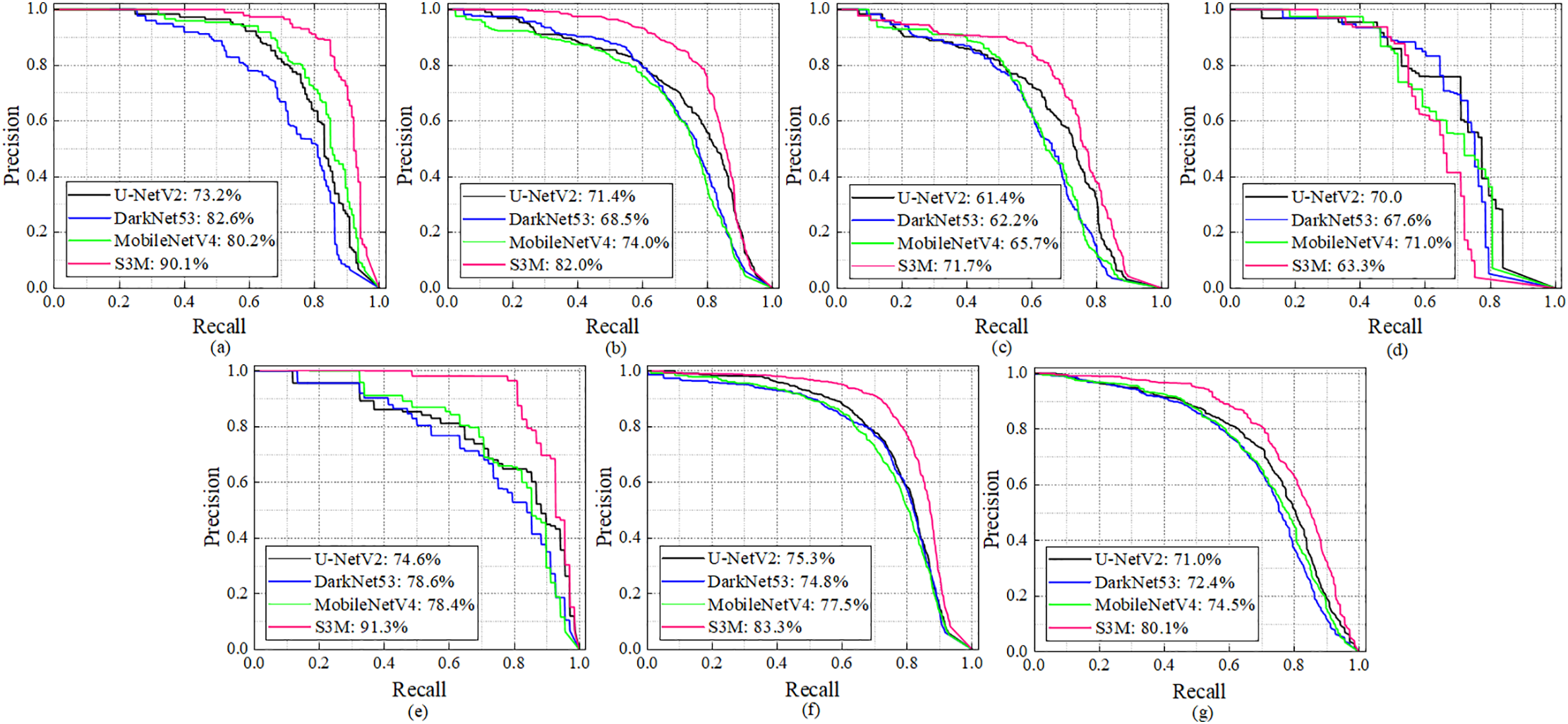

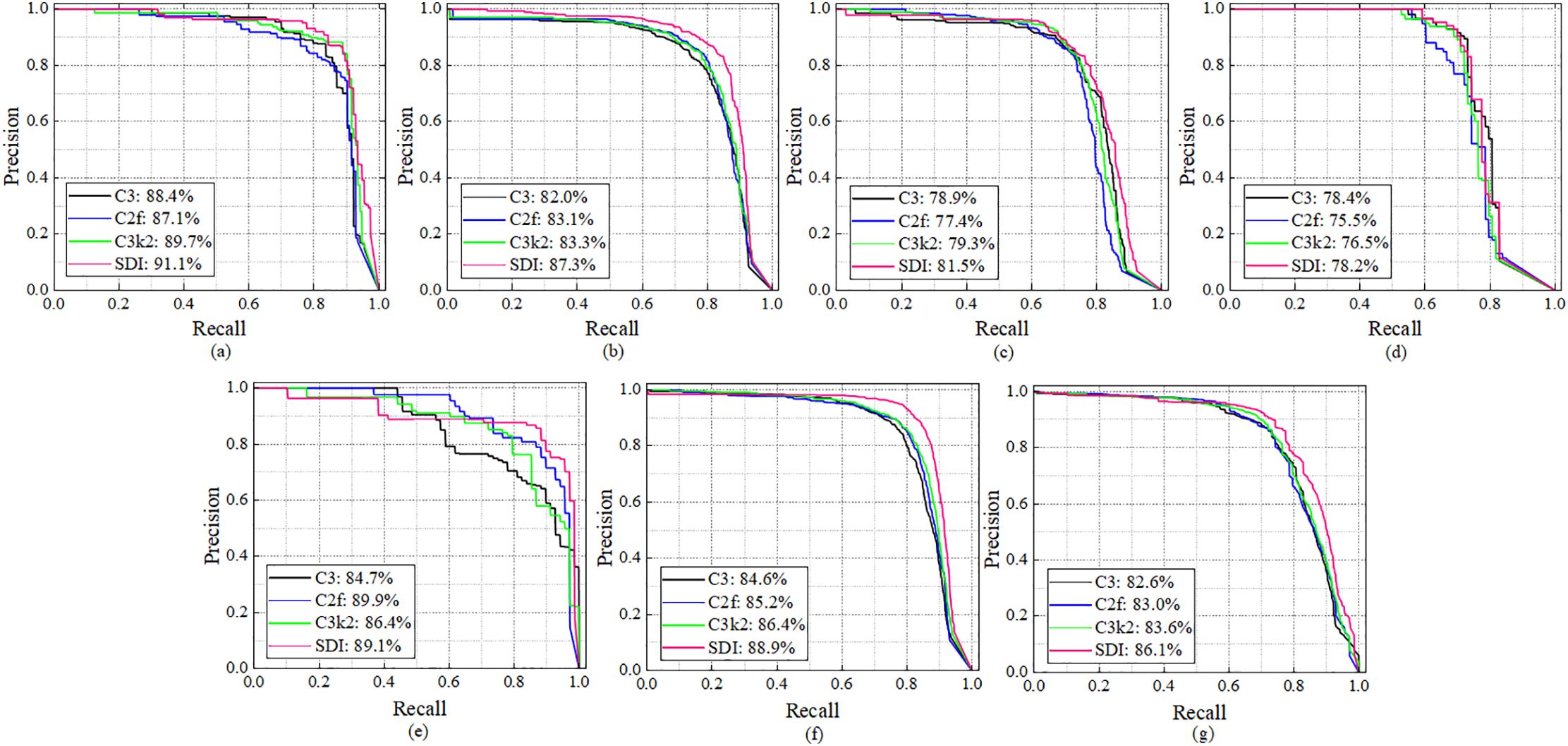

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed ARPD model’s backbone and neck configurations, precision-recall (PR) curves are used to illustrate the balance between P and R. Figs. 6 and 7 present the ablation study results for the backbone and neck modules, respectively.

Figure 6: Backbone ablation experiment of ARPD algorithm equipped with the same SDI-based neck. (a–g) respectively represent PR curves for AC, LC, OC, PH, RP, TC, and the all-classes mAP

Figure 7: Neck ablation experiment of ARPD algorithm equipped with the same S3M-based backbone. (a–g) respectively represent PR curves for AC, LC, OC, PH, RP, TC, and the all-classes mAP

Backbone Ablation Study: Using a consistent C3k2-based neck structure across all configurations, different backbones are integrated into ARPD (including MobileNetV4 [26], U-NetV2 [27], DarkNet53 [17], and the proposed S3M) for comparison. As shown by the pink curve in Fig. 6, the S3M backbone achieves the best performance in extracting pavement defects, reaching the highest mAP of 80.1%. Notably, for AC and RP classes, the S3M-based model achieves over 90% precision, demonstrating the strong adaptability of S3M to diverse road surface damage types.

Neck Ablation Study: Building on the confirmed superiority of the S3M backbone, additional experiments are conducted by integrating various neck structures into ARPD while keeping the S3M backbone fixed. The tested neck modules include C3 [16], C2f [17], C3k2 [17], and the proposed SDI. As illustrated by the pink curve in Fig. 7g, the ARPD model equipped with both the S3M backbone and SDI neck structure achieves the best overall performance, with a mAP of 86.1%. This also reflects a significant improvement compared to the best result from the backbone ablation study (80.1%), confirming the effectiveness of SDI in multi-scale feature integration for pavement defect detection.

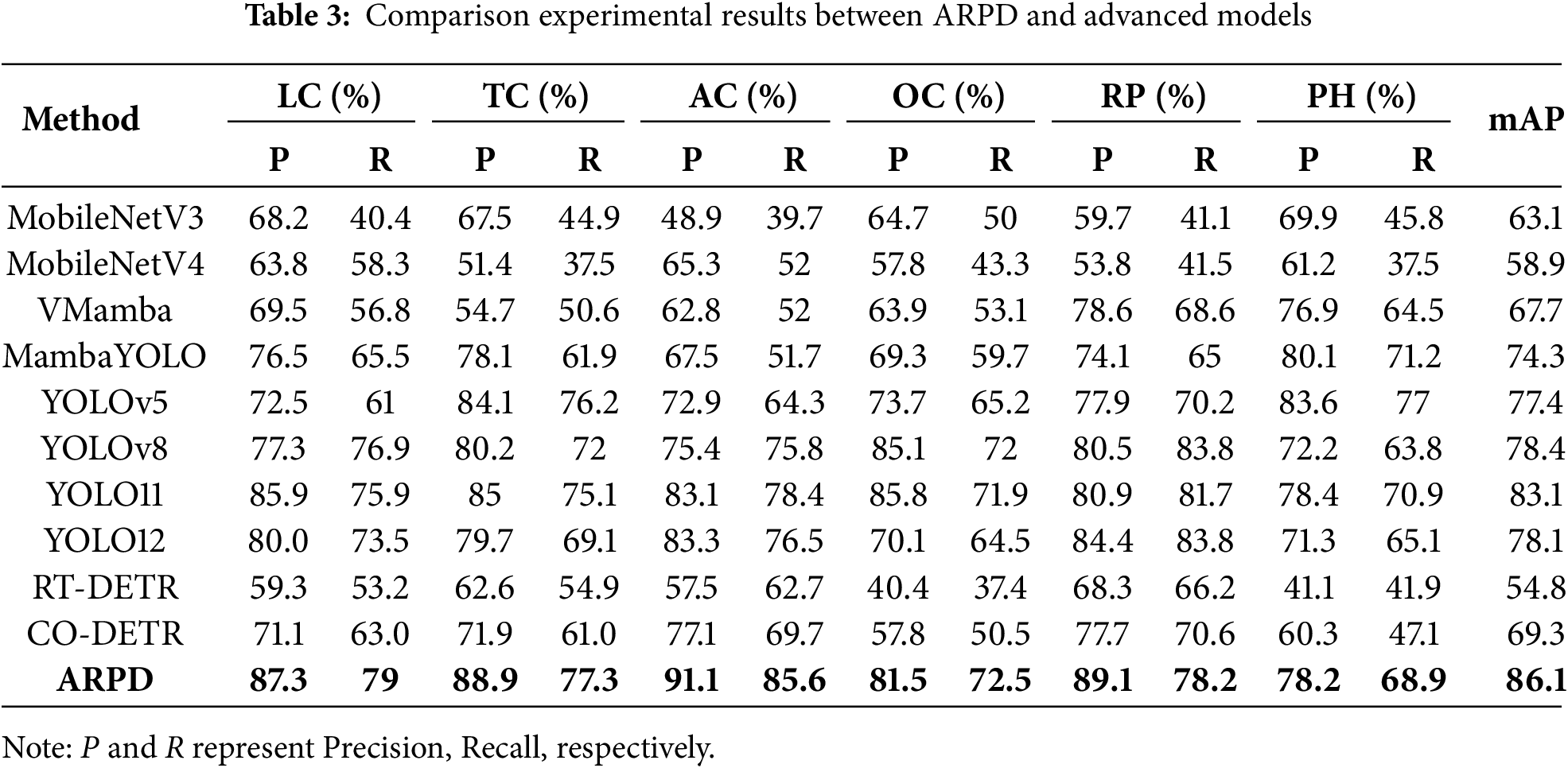

Based on the preceding ablation studies, the ARPD algorithm has demonstrated superior performance on UAV-based pavement defect datasets. To further validate its effectiveness, ARPD is compared against several state-of-the-art object detection models, including the YOLO series [16–18], MobileNet series [26,35], DETR series [36,37] and Mamba-based models [33,34], under the same dataset conditions.

As presented in Table 3, ARPD ranks first among all models with a mAP of 86.1%. The state-of-the-art detection framework YOLO11 demonstrates superior performance over YOLOv8 (83.1% vs. 78.4%), primarily due to its innovative architectural components such as C2PSA and C3k2, ranking second and third, respectively. The latest YOLO12 introduces A2C2f for enhanced attention and hierarchical training, it still struggles with sparse and multi-scale pavement defects, and is even outperformed by YOLOv8 in our experiments. Although Mamba-based architectures excel at image classification and long-range modeling, they typically require additional modules for fine-grained feature extraction. The complex characteristics of pavement defects significantly limit the effectiveness of state-space models in this context, indicating room for improvement. Moreover, while MobileNet variants are commonly adopted for lightweight deployment, they exhibit poor performance (<65%) in pavement scenarios characterized by minimal semantic information and complex visual backgrounds. The DETR series, while offering real-time end-to-end detection capabilities, continues to face significant challenges in balancing inference speed and detection accuracy.

In summary, the proposed combination of S3M and SDI achieves the best detection accuracy among all evaluated models in UAV-based pavement defect recognition, making it a reliable component of the ARPD algorithm for automatic road damage inspection.

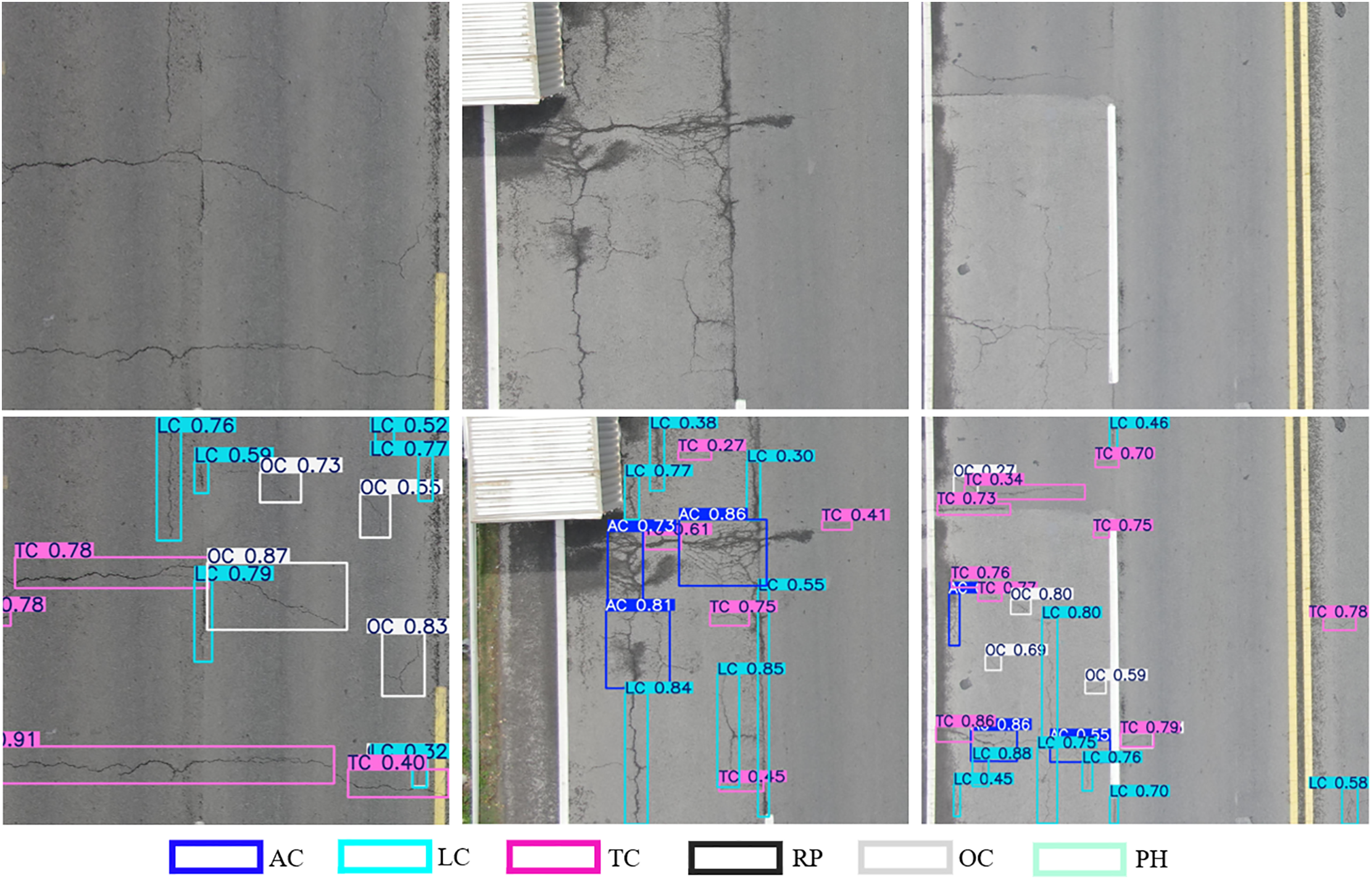

3.5 Visualization-Based Validation

Visualization results based on the test set are shown in Fig. 8, where the first and second rows represent the original UAV images and the corresponding ARPD predictions. The proposed algorithm demonstrates accurate localization of elongated pavement defects, including fragmented and irregularly distributed oblique cracks. Furthermore, even when multiple types of defects with similar visual features appear simultaneously, ARPD maintains precise detection performance. These results confirm that ARPD exhibits strong adaptability and robustness even in scenarios with minimal pixel-level defect presence.

Figure 8: Visual verification of ARPD algorithm based on test-set

Additionally, a separate visualization experiment is conducted on 200 randomly selected images from the public RDD-2022 dataset. As shown in Fig. 9, images captured from an in-vehicle perspective often led to vertical cracks (LC) being misidentified as oblique cracks (OC), as indicated by the red arrows. Despite this visual ambiguity, ARPD successfully detects all defect instances in each image, further demonstrating its generalization capability and robustness, and highlighting its suitability for real-world road inspection tasks involving diverse defect types and imaging conditions.

Figure 9: Visual verification of ARPD algorithm based on RDD-2022

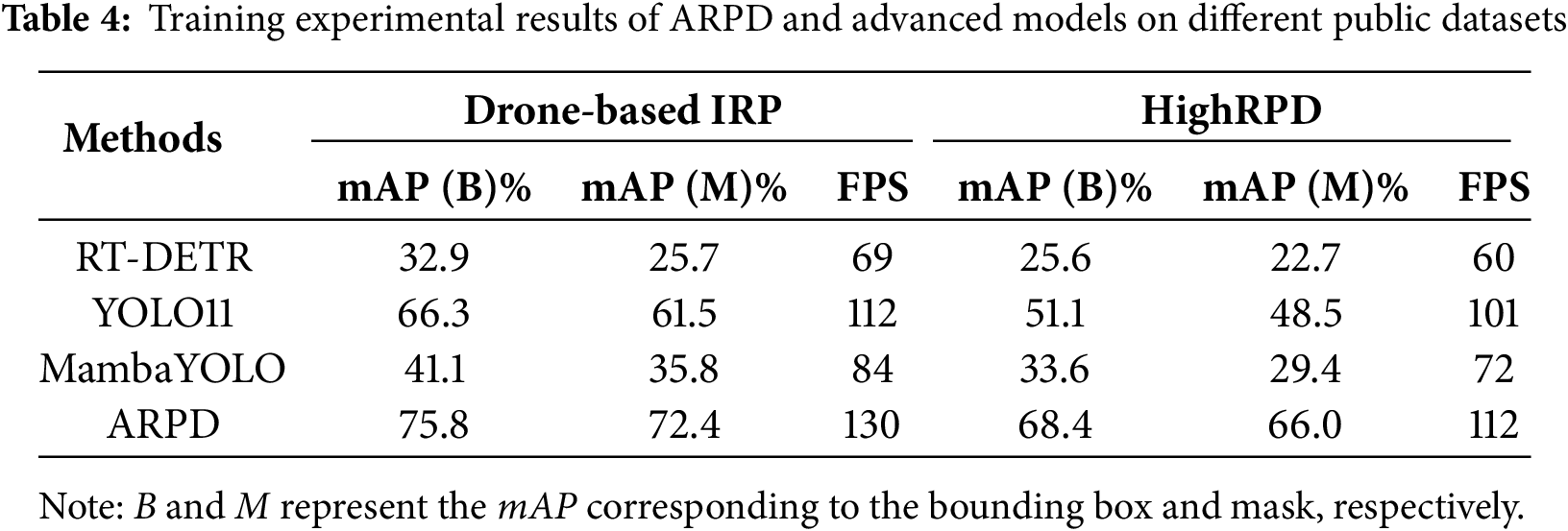

To further evaluate the reproducibility and generalization capability of the proposed algorithm, additional comparative experiments are conducted on publicly available UAV-captured pavement defect datasets, specifically Drone-based IRP [38] and HighRPD [39]. As shown in Table 4, all benchmark models are evaluated under identical configurations, and our method consistently achieved the highest accuracy. Notably, this experiment also assessed training FPS. Although RT-DETR outperformed the YOLO series in accuracy under ample computational resources, it lacks mobile-device compatibility and is surpassed by MambaYOLO in processing speed. Despite being a recent state-of-the-art detector, YOLOv11 shows performance limitations in complex pavement conditions. Overall, these results highlight the strong generalization and practical deployment potential of the proposed algorithm in real-world UAV-based pavement defect inspection.

This paper presents an Automatic Recognition of Pavement Defect (ARPD) algorithm, integrating a Selective State Space Model (S3M) and Semantic Detail Infusion (SDI), to address the challenges of recognizing multi-type road surface defects under limited semantic cues and large variations in object scale. A UAV-based dataset, UAV-PDD2023, was collected to provide full-coverage overhead images of road surfaces. The S3M-based backbone is embedded into ARPD to selectively model the most relevant temporal dependencies in long-sequence feature extraction. Considering that conventional neck modules rely heavily on pyramid structures and often fail to handle multi-scale features effectively, the SDI module is incorporated to enhance semantic and fine-detail fusion between shallow and deep features. This allows the algorithm to emphasize relevant damage features while suppressing noise, thereby improving detection accuracy.

The model’s performance is further validated using both a held-out test set and an external benchmark dataset (RDD-2022). Experimental results indicate that ARPD surpasses state-of-the-art models such as YOLOv11 in both accuracy and generalization. However, the algorithm has not yet been deployed or evaluated on embedded hardware platforms, and the real-time inference speed remains untested. Future work will focus on

(1) Building a UAV-based pavement surface defect dataset that includes both asphalt and concrete pavements;

(2) Develop a lightweight automatic road defect recognition algorithm that can be embedded with high precision, low energy consumption, and mobile-friendly features.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported in part by the Technical Service for the Development and Application of an Intelligent Visual Management Platform for Expressway Construction Progress Based on BIM Technology (grant NO. JKYZLX-2023-09), in part by the Technical Service for the Development of an Early Warning Model in the Research and Application of Key Technologies for Tunnel Operation Safety Monitoring and Early Warning Based on Digital Twin (grant NO. JK-S02-ZNGS-202412-JISHU-FA-0035), sponsored by Yunnan Transportation Science Research Institute Co., Ltd.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Hongcheng Zhao and Tong Yang; methodology, Hongcheng Zhao, Tong Yang, Yihui Hu and Fengxiang Guo; software, Hongcheng Zhao and Tong Yang; formal analysis, Hongcheng Zhao, Tong Yang and Yihui Hu; investigation, Hongcheng Zhao, Tong Yang, Yihui Hu and Fengxiang Guo; resources, Fengxiang Guo; data curation, Yihui Hu and Fengxiang Guo; writing—original draft preparation, Hongcheng Zhao and Tong Yang; writing—review and editing, Hongcheng Zhao and Tong Yang; visualization, Hongcheng Zhao; supervision, Hongcheng Zhao and Fengxiang Guo; project administration, Fengxiang Guo; funding acquisition, Hongcheng Zhao and Fengxiang Guo. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available on request from the author [Tong Yang, yangt@stu.kust.edu.cn].

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Yan H, Zhang J. UAV-PDD2023: a benchmark dataset for pavement distress detection based on UAV images. Data Brief. 2023;51(12):109692. doi:10.1016/j.dib.2023.109692. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Guo F, Qian Y, Liu J, Yu H. Pavement crack detection based on transformer network. Autom Constr. 2023;145(2):104646. doi:10.1016/j.autcon.2022.104646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Alkhedher M, Alsit A, Alhalabi M, AlKheder S, Gad A, Ghazal M. Novel pavement crack detection sensor using coordinated mobile robots. Transp Res Part C Emerg Technol. 2025;172(1386):105021. doi:10.1016/j.trc.2025.105021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Guerrieri M, Parla G, Khanmohamadi M, Neduzha L. Asphalt pavement damage detection through deep learning technique and cost-effective equipment: a case study in urban roads crossed by tramway lines. Infrastructures. 2024;9(2):34. doi:10.3390/infrastructures9020034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Askarzadeh T, Bridgelall R, Tolliver DD. Drones for road condition monitoring: applications and benefits. J Transp Eng Part B Pavements. 2025;151(1):04024055. doi:10.1061/jpeodx.pveng-1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Matarneh S, Elghaish F, Al-Ghraibah A, Abdellatef E, Edwards DJ. An automatic image processing based on Hough transform algorithm for pavement crack detection and classification. Smart Sustain Built Environ. 2025;14(1):1–22. doi:10.1108/sasbe-01-2023-0004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Tello-Cifuentes L, Marulanda J, Thomson P. Detection and classification of pavement damages using wavelet scattering transform, fractal dimension by box-counting method and machine learning algorithms. Road Mater Pavement Des. 2024;25(3):566–84. doi:10.1080/14680629.2023.2219338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Chou JS, Liu CY. Optimized lightweight edge computing platform for UAV-assisted detection of concrete deterioration beneath bridge decks. J Comput Civ Eng. 2025;39(1):04024045. doi:10.1061/jccee5.cpeng-5905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Zhang Y, Si J, Si B. Integrative approach for high-speed road surface monitoring: a convergence of robotics, edge computing, and advanced object detection. Appl Sci. 2024;14(5):1868. doi:10.3390/app14051868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Liang J, Gu X, Jiang D, Zhang Q. CNN-based network with multi-scale context feature and attention mechanism for automatic pavement crack segmentation. Autom Constr. 2024;164(4):105482. doi:10.1016/j.autcon.2024.105482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Li P, Zhou B, Wang C, Hu G, Yan Y, Guo R, et al. CNN-based pavement defects detection using grey and depth images. Autom Constr. 2024;158(2):105192. doi:10.1016/j.autcon.2023.105192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Alshawabkeh S, Dong D, Cheng Y, Li L, Wu L. A hybrid approach for pavement crack detection using mask R-CNN and vision transformer model. Comput Mater Contin. 2025;82(1):561–77. doi:10.32604/cmc.2024.057213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Ren S, He K, Girshick R, Sun J. Faster R-CNN: towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2016;39(6):1137–49. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2016.2577031. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. He K, Gkioxari G, Dollár P, Girshick R. Mask R-CNN. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2017 Oct 22–29;Venice, Italy. doi:10.1109/ICCV.2017.322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Cheng B, Misra I, Schwing AG, Kirillov A, Girdhar R. Masked-attention mask transformer for universal image segmentation. In: 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2022 Jun 18–24; New Orleans, LA, USA. doi:10.1109/CVPR52688.2022.00135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Jocher G, Chaurasia A, Stoken A, Borovec J, Kwon Y, Michael K, et al. YOLOv5 by Ultralytics (Version 7.0) [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jul 17]. Available from: 10.5281/zenodo.3908559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Jocher G, Qiu J, Chaurasia A. Ultralytics YOLO (Version 8.0.0) [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jul 17]. Available from: https://github.com/ultralytics/ultralytics. [Google Scholar]

18. Tian Y, Ye Q, Doermann D. YOLOv12: attention-centric real-time object detectors. arXiv:2502.12524. 2025. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2502.12524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Shan J, Jiang W, Huang Y, Yuan D, Liu Y. Unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV)-based pavement image stitching without occlusion, crack semantic segmentation, and quantification. IEEE Trans Intell Transp Syst. 2024;25(11):17038–53. doi:10.1109/TITS.2024.3424525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Tse KW, Pi R, Yang W, Yu X, Wen CY. Advancing UAV-based inspection system: the USSA-net segmentation approach to crack quantification. IEEE Trans Instrum Meas. 2024;73:2522914. doi:10.1109/TIM.2024.3418073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Feng S, Gao M, Jin X, Zhao T, Yang F. Fine-grained damage detection of cement concrete pavement based on UAV remote sensing image segmentation and stitching. Measurement. 2024;226(3):113844. doi:10.1016/j.measurement.2023.113844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Dugalam R, Prakash G. Development of a random forest based algorithm for road health monitoring. Expert Syst Appl. 2024;251(1):123940. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2024.123940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Li M, Yuan J, Ren Q, Luo Q, Fu J, Li Z. CNN-transformer hybrid network for concrete dam crack patrol inspection. Autom Constr. 2024;163(1):105440. doi:10.1016/j.autcon.2024.105440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Liu H, Jia C, Shi F, Cheng X, Chen S. SCSegamba: lightweight structure-aware vision mamba for crack segmentation in structures. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR2025); 2025 Jun 10–17; Nashville, TN, USA. [Google Scholar]

25. Dosovitskiy A, Beyer L, Kolesnikov A, Weissenborn D, Zhai X, Unterthiner T, et al. An image is worth 16 × 16 words: transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv:2010.11929. 2020. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2010.11929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Qin D, Leichner C, Delakis M, Fornoni M, Luo S, Yang F, et al. MobileNetV4: universal models for the mobile ecosystem. In: Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2024. 2024 Sep 29–Oct 4; Milan, Italy. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-73661-2_5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Peng Y, Sonka M, Chen DZ. U-net v2: rethinking the skip connections of U-net for medical image segmentation. arXiv:2311.17791. 2023. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2311.17791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Gu A, Dao T. Mamba: linear-time sequence modeling with selective state spaces. arXiv:2312.00752. 2023. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2312.00752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Han C, Yang H, Yang Y. Enhancing pixel-level crack segmentation with visual mamba and convolutional networks. Autom Constr. 2024;168(1):105770. doi:10.1016/j.autcon.2024.105770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Zhu Q, Fang Y, Fan L. MSCrackMamba: leveraging vision mamba for crack detection in fused multispectral imagery. arXiv:2412.06211. 2024. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2412.06211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Arya D, Maeda H, Ghosh SK, Toshniwal D, Sekimoto Y. RDD2022: a multi-national image dataset for automatic road damage detection. Geosci Data J. 2024;11(4):846–62. doi:10.1002/gdj3.260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Chollet F. Xception: deep learning with depthwise separable convolutions. In: Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2017 Jul 21–26;Honolulu, HI, USA. [Google Scholar]

33. Liu Y, Tian Y, Zhao Y, Yu H, Xie L, Wang Y, et al. Vmamba: visual state space model. In: Proceedings of the Neural Information Processing Systems 37 (NeurIPS 2024). 2024 Dec 10–15; Vancouver, BC, Canada. [Google Scholar]

34. Wang Z, Li C, Xu H, Zhu X. Mamba YOLO: SSMs-based YOLO for object detection. arXiv:2406.05835. 2024. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2406.05835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Koonce B. MobileNetV3. In: Koonce B, editor. Convolutional neural networks with swift for tensorflow: image recognition and dataset categorization. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2021. p. 125–44. doi:10.1007/978-1-4842-6168-2_11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Zhao Y, Lv W, Xu S, Wei J, Wang G, Dang Q, et al. DETRs beat YOLOs on real-time object detection. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR2024); 2024 Jun 17–21; Seattle, WA, USA. [Google Scholar]

37. Zong Z, Song G, Liu Y. DETRs with collaborative hybrid assignments training. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR2023); 2023 Jun 18–22;Vancouver, BC, Canada. [Google Scholar]

38. Nooralishahi P, Ramos G, Maldague X. Dataset for drone-based inspection of road pavement structures for cracks, Mendeley Data, V1 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jul 17]. Available from: https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/csd32bm8zx/1. [Google Scholar]

39. He J, Gong L, Xu C, Wang P, Zhang Y, Zheng O, et al. HighRPD: a high-altitude drone dataset of road pavement distress. Data Brief. 2025;59:111377. doi:10.1016/j.dib.2025.111377. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools