Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Temperature-Indexed Concrete Damage Plasticity Model Incorporating Bond-Slip Mechanism for Thermo-Mechanical Analysis of Reinforced Concrete Structures

1 Centre for Infrastructure Geo-Hazards and Sustainability Materials, Faculty of Engineering, Built Environment and Information Technology, SEGi University, Kota Damansara, Petaling Jaya, 47810, Selangor, Malaysia

2 Faculty of Architecture and Design, Yunnan Technology and Business University, Kunming, 650106, China

3 Graduate School of Business, SEGI University, Kota Damansara, Petaling Jaya, 47810, Selangor, Malaysia

* Corresponding Author: Wu Feng. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advanced Strategies for Structural and Non-Structural Seismic Protection and Damage Prediction in Reinforced Concrete Structures)

Structural Durability & Health Monitoring 2026, 20(1), . https://doi.org/10.32604/sdhm.2025.071664

Received 09 August 2025; Accepted 26 September 2025; Issue published 08 January 2026

Abstract

This study investigates the thermo–mechanical behavior of C40 concrete and reinforced concrete subjected to elevated temperatures up to 700°C by integrating experimental testing and advanced numerical modeling. A temperature-indexed Concrete Damage Plasticity (CDP) framework incorporating bond–slip effects was developed in Abaqus to capture both global stress–strain responses and localized damage evolution. Uniaxial compression tests on thermally exposed cylinders provided residual strength data and failure observations for model calibration and validation. Results demonstrated a distinct two-stage degradation regime: moderate stiffness and strength reduction up to ~400°C, followed by sharp deterioration beyond 500°C–600°C, with residual capacity at 700°C reduced to ~20%–25% of the ambient value. Strain–damage analyses revealed the formation of a peripheral tensile strain band, which thickened and propagated inward with increasing temperature, governing crack initiation and cover spalling. Supplemental analyses highlighted that transverse reinforcement improved ductility and damage distribution at moderate temperatures (~300°C), but bond deterioration and steel softening beyond ~600°C substantially diminished confinement effectiveness. The proposed CDP model accurately reproduced experimental stress–strain curves (R2 ≈ 0.94–0.98 up to 600°C; ≈0.90 at 700°C), with peak stress errors within 7%–10% and energy absorption captured within ~12%. These findings confirm the robustness of the temperature-indexed CDP framework for simulating fire-damaged reinforced concrete and provide practical guidelines for post-fire assessment, spalling detection, and fire-resilient design of structural members.Keywords

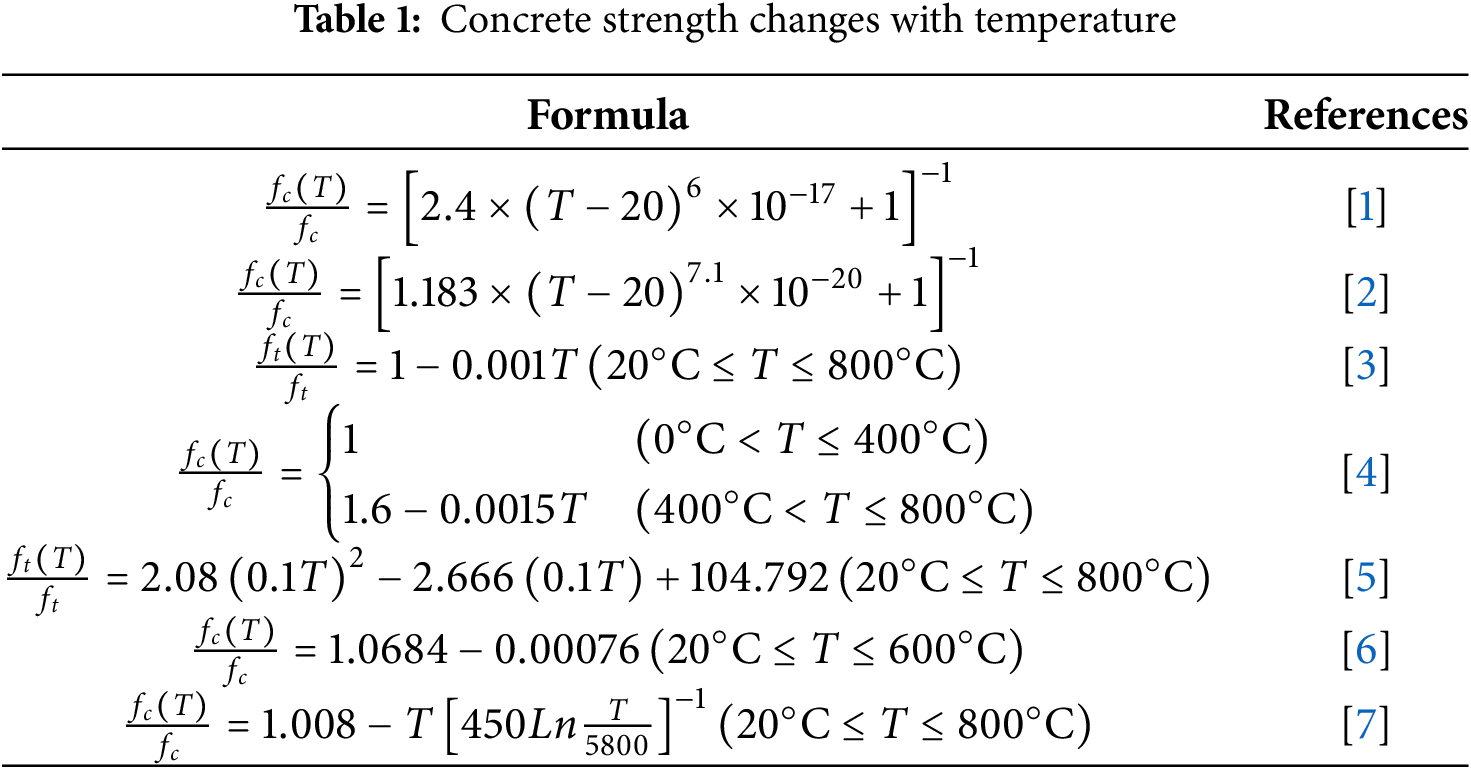

High temperature exposure causes a well-documented degradation of concrete strength, which has been quantified through various empirical formulations. Table 1 compiles representative expressions proposed by multiple researchers over the past decades. These functions describe the normalized compressive or tensile strength of concrete,

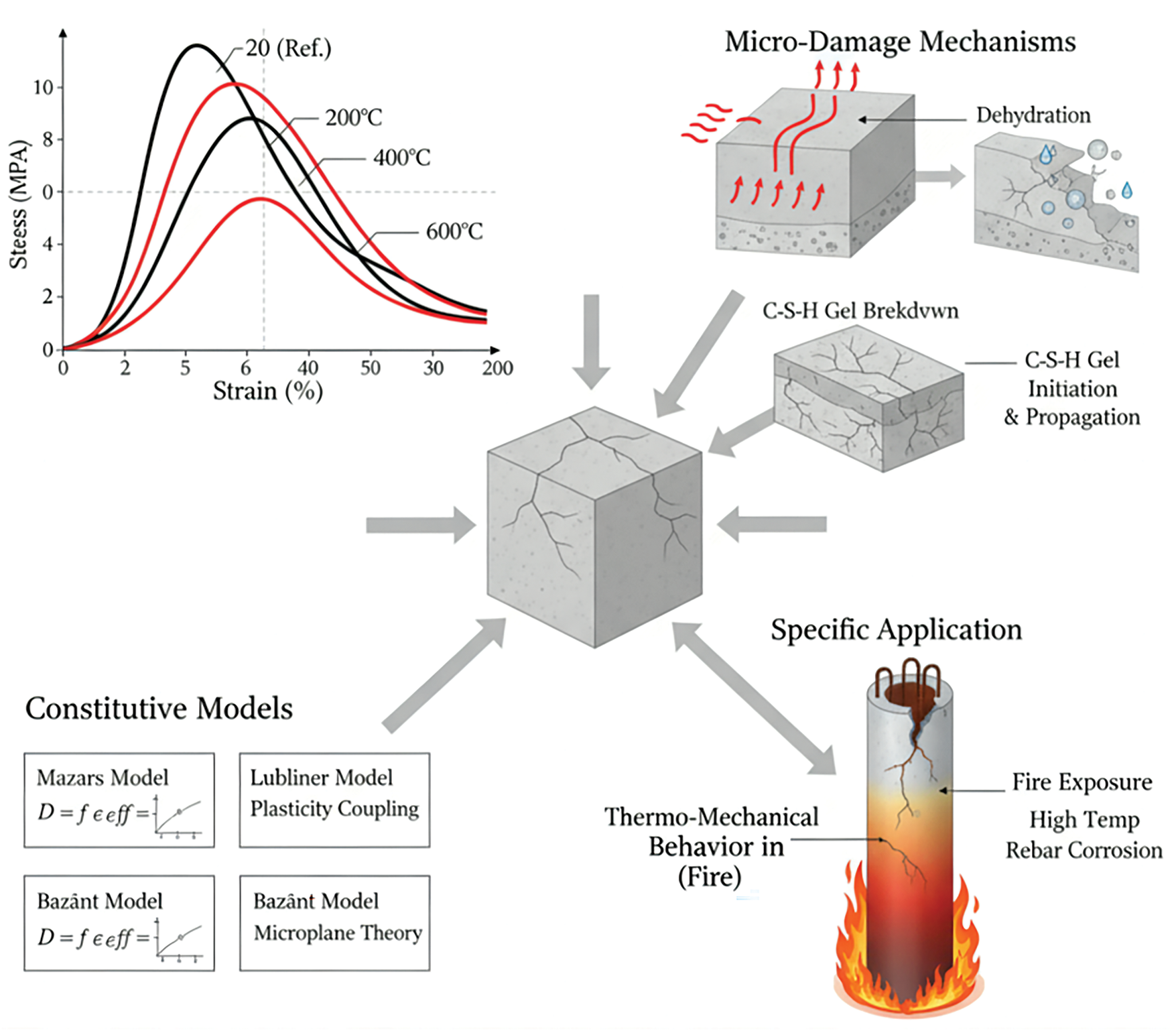

At elevated temperatures, concrete undergoes a series of progressive and interrelated degradation processes that critically impair its structural performance. Micro-damage initiates with the dehydration of free and chemically bound water, which produces internal vapor pressure and induces microcracking within the cement paste [10]. With increasing temperature, the calcium–silicate–hydrate (C–S–H) gel progressively decomposes, resulting in the loss of cohesion in the cementitious matrix [11,12]. This microstructural weakening is further compounded by the initiation and propagation of cracks at the aggregate–paste interfaces, which accelerate stiffness degradation and strength reduction. At the macroscopic level, these mechanisms translate into significant reductions in both load-bearing capacity and ductility [13]. The mechanical response can be clearly distinguished through stress–strain behavior: at ambient temperature (20°C), the material demonstrates a steep elastic slope and a well-defined peak strength; at intermediate exposures (200°C–400°C), stiffness and peak stress decrease noticeably while post-peak ductility diminishes; beyond 400°C, the stress–strain curves flatten considerably, reflecting a transition toward weaker but more ductile-like behavior, with residual strength dropping to less than half of the original capacity near 600°C [14,15], as illustrated in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Concrete degradation mechanism and application

These degradation pathways are not only of academic interest but also of critical practical relevance. In fire-exposed reinforced concrete members, bond-slip deterioration, loss of confinement efficiency, and reinforcement corrosion interact with the intrinsic thermal damage of concrete, creating complex coupled effects [16]. Traditional constitutive models such as those of Mazars, Lubliner, and Bažant capture selected aspects of plasticity–damage coupling or microplane behavior, but they are limited in representing the full spectrum of temperature-induced degradation [17–19]. The present research addresses this gap by developing a temperature-indexed Concrete Damage Plasticity (CDP) framework that explicitly integrates bond–slip mechanisms [20,21]. This approach allows the calibrated model not only to replicate the global stress–strain trajectories across the temperature range of 20°C–800°C but also to reproduce localized failure patterns, including tensile strain bands, bulging, and spalling initiation [22]. Moreover, by incorporating temperature-dependent tensile strength and energy absorption capacity, the proposed model provides a more accurate quantification of ductility evolution and failure modes [23].

In this study, the thermo-mechanical behavior of concrete is therefore understood as the combined outcome of microstructural degradation, constitutive parameter evolution, and bond-dependent confinement effects. By bridging these scales within a unified modeling framework, the research advances predictive capability for post-fire residual performance, offering direct implications for structural assessment, safety design, and inspection methodologies in reinforced concrete infrastructure.

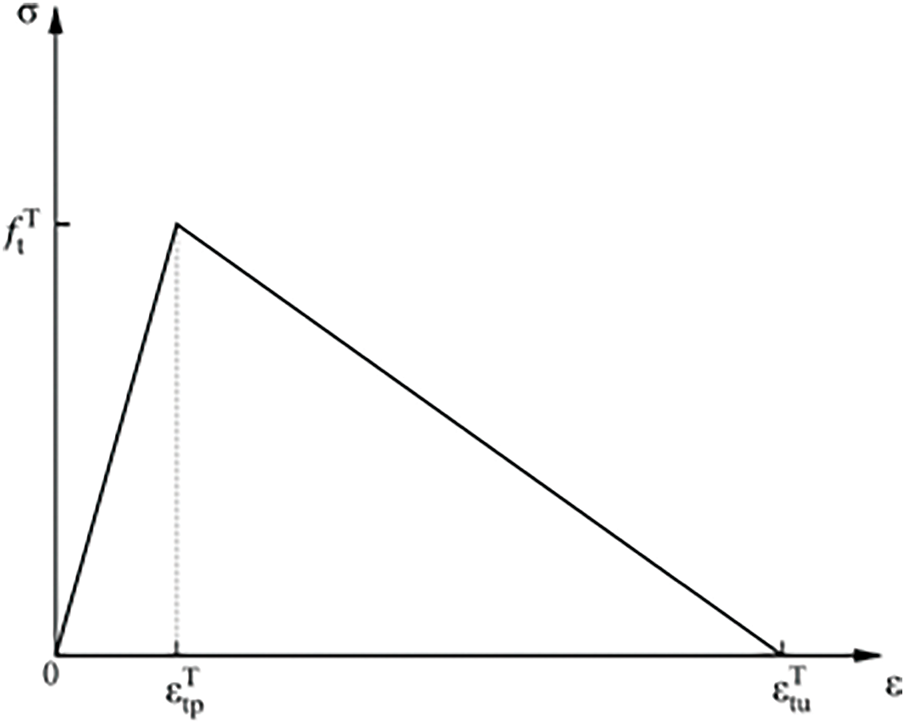

2.1 Materials and Specimen Preparation

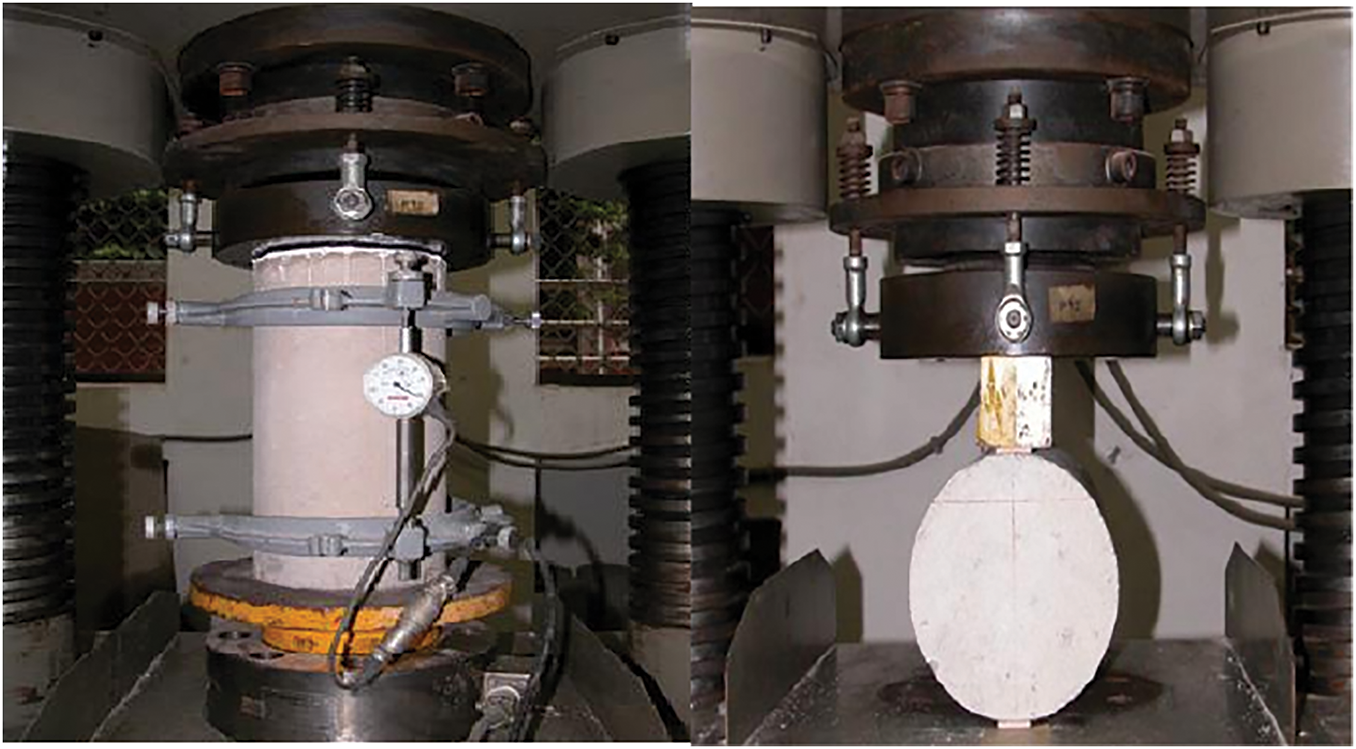

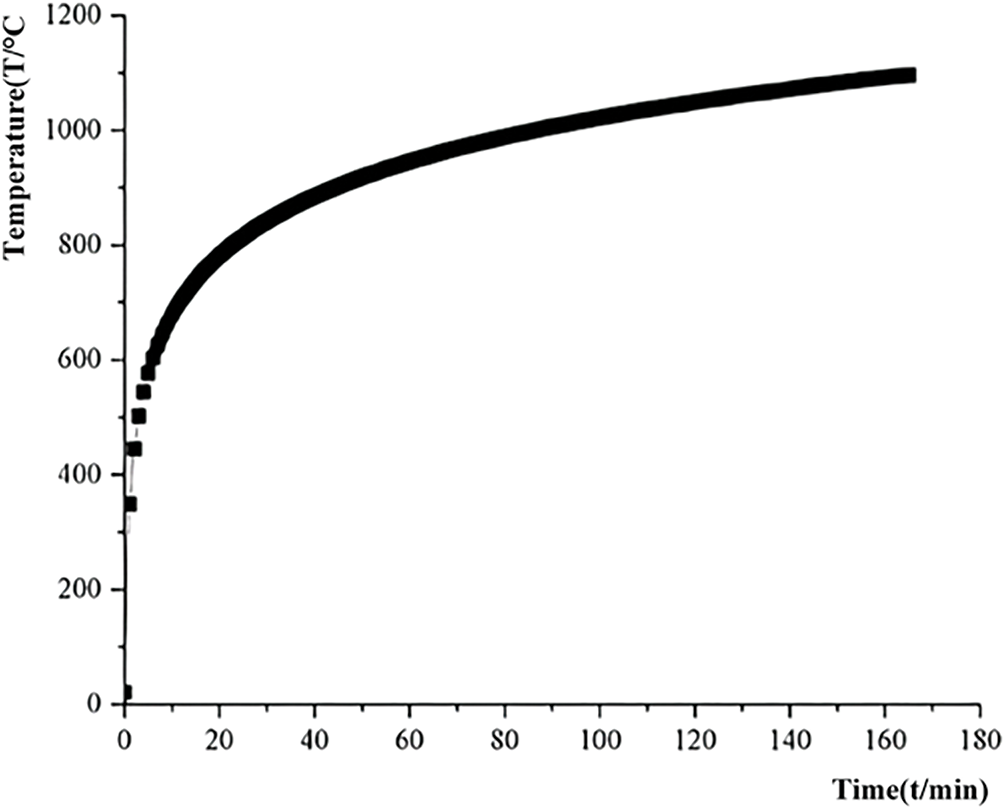

The experimental program involved uniaxial compression tests on concrete cylinders after exposure to various elevated temperatures [24]. Fig. 2 shows the test apparatus, including the furnace and compressor, and Fig. 3 shows the cracking behavior of the concrete after thermal-mechanical coupling. The specimens were standard cylinders (150 mm diameter × 300 mm height) cast from C40 concrete. A total of 12 specimens were tested, with target peak temperatures of 20°C (ambient), 100°C, 300°C, 500°C, and 700°C (each specimen experienced a peak temperature). Heating was performed at a controlled rate (starting at approximately 1°C/min, increasing to approximately 4–5°C/min at higher temperatures) to simulate a fire heating scenario. Each specimen was held at the target temperature plateau (Fig. 3) for a sufficient period of time to achieve thermal equilibrium and then allowed to cool to ambient temperature before compression testing to measure residual strength. Table 2 lists key material details: All cylinders were constructed of ordinary Portland cement concrete with a 28-day compressive strength of approximately 40 MPa. The peak temperatures and corresponding heating rates are listed for the thermal conditions (Table 2). During the compression tests, the load was applied quasi-statically, while the axial strain was measured over a 200 mm gauge length. This test method follows established procedures for evaluating the performance of concrete after fire. Overall, the tests generated stress-strain curves for concrete after exposure to discrete elevated temperatures, providing data on strength and stiffness degradation, as well as observations of cracking and failure modes for model validation.

Figure 2: Experimental setup and compression method

Figure 3: Heating protocol for concrete specimens

In fire scenarios, concrete’s compressive strength (which largely governs load-bearing capacity) is also progressively eroded by heat. This section examines how prior thermal exposure reduces the subsequent compressive strength of concrete after cooling. Concrete cylinders were heated to various peak temperatures, allowed to cool, and then tested in compression to failure to assess residual strength. Fig. 3 illustrates representative post-fire compression test specimens.

The model accounts for concrete’s high-temperature thermal properties—density, conductivity, and specific heat. The thermal parameters adopted for steel and concrete are defined as follows:

(1) The thermal conductivity of concrete

Concrete density

The thermal conductivity of concrete in this article refers to the formula:

Calculation formula for thermal expansion coefficient of concrete:

(2) The thermal parameters of steel reinforcement

The steel reinforcement density used in this study is

2.3 The Thermodynamic Parameters of Concrete

The yield surface in the CDP model is designed to capture concrete’s pressure-sensitive failure behavior, distinguishing between its tensile and compressive strength. In the effective stress space, the yield condition is typically expressed using stress invariants, combining Drucker–Prager-type pressure dependence with components that account for the impact of the maximum principal stress—key for modeling concrete’s relatively low tensile strength.

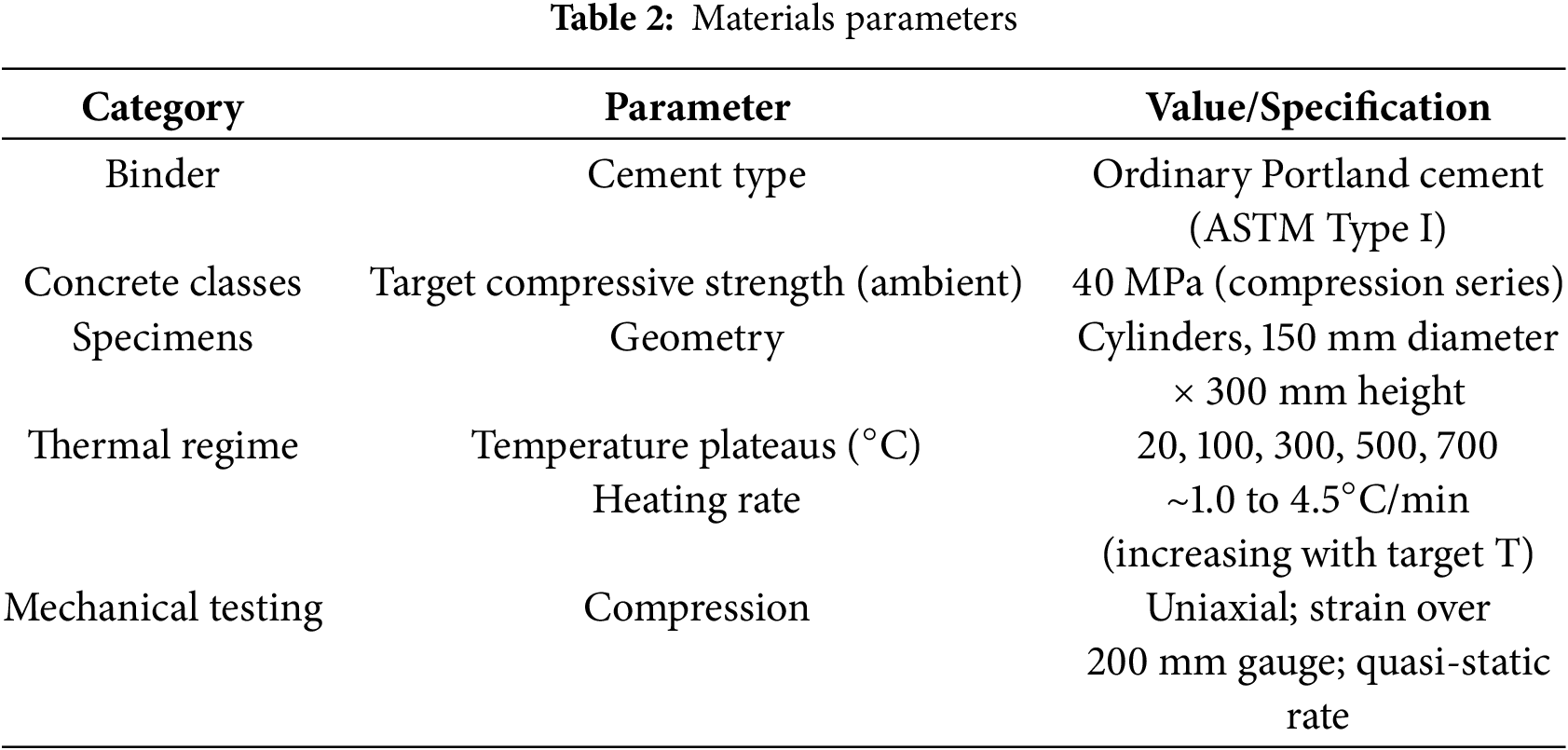

where fc(T) and fc represent the temperature-dependent and ambient compressive strengths, respectively. The proposed empirical formula describes the strength degradation using an exponential decay, aligning with the typical thermal softening observed in high-temperature concrete studies. These two formulas for material strength decay outline the variations in concrete tensile strength and steel yield strength as functions of temperature, as illustrated in Fig. 4.

Figure 4: Tensile stress-strain curve of concrete

At elevated temperatures, concrete’s elastic modulus declines; the temperature-dependent modulus is given by:

The elastic modulus of steel bars under fire is as follows:

The temperature-dependent coefficient of thermal expansion of concrete (αc) varies linearly with temperature from 20°C to 800°C.

The temperature-dependent thermal expansion coefficient of the steel bar (αs) increases with temperature up to 800°C.

The thermal boundary conditions employed in the constitutive framework are derived from the ISO 834 standard fire curve, which serves as a benchmark for simulating typical fire scenarios in structural performance evaluation. The temperature–time relationship is governed by a well-known empirical formulation that captures the characteristic rise of temperature during fire exposure exposureas shown in Fig. 5.

Figure 5: ISO 834 fire-affected curve

These equations are essential for characterizing the thermomechanical behavior of concrete, particularly in modeling the degradation of key properties such as thermal expansion, stiffness, and stress response at high temperatures. In summary, these constitutive relations provide a thermodynamically consistent framework for implementing the CDP model in ABAQUS, accurately capturing temperature-dependent stiffness reduction and irreversible plastic deformation. This forms the computational basis for the subsequent numerical simulations and theoretical analysis.

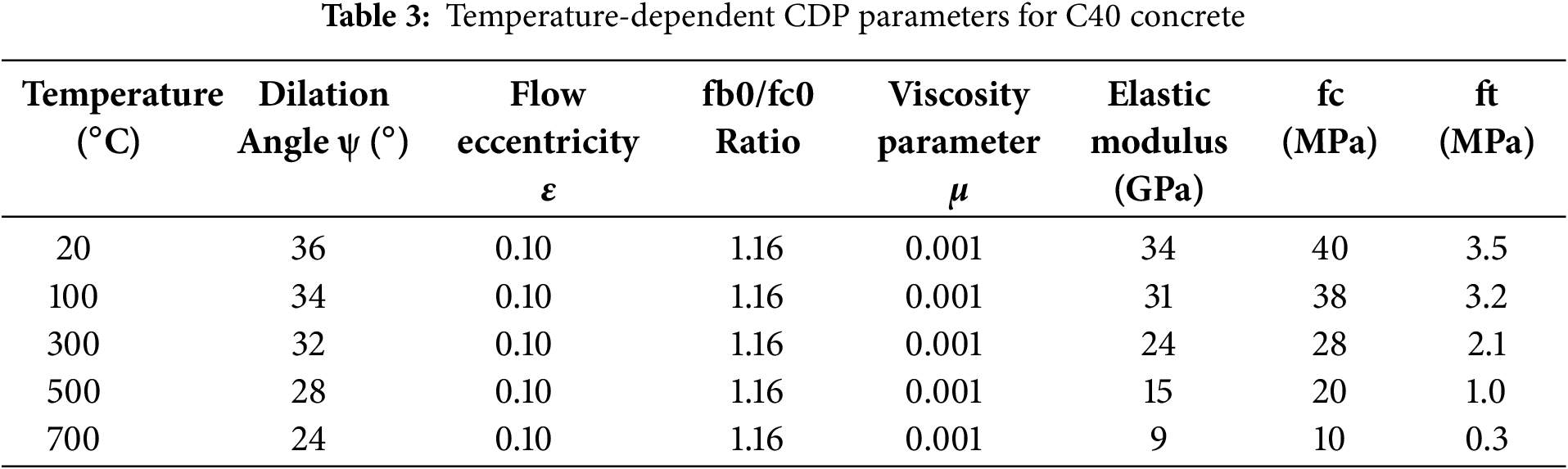

To ensure reproducibility and accurately represent the progressive degradation of material properties under elevated temperatures, the temperature-indexed Concrete Damage Plasticity (CDP) model requires careful calibration of its key constitutive parameters. These include the dilation angle, flow eccentricity, the ratio of biaxial to uniaxial compressive strength (fb0/fc0), the viscosity parameter, and temperature-dependent values of elastic modulus and strength. Following established guidelines (Lee & Fenves, 1998; Eurocode 2) and recent fire-related concrete studies, the parameters were systematically adjusted across the temperature range of 20°C–700°C. This approach guarantees numerical stability while faithfully capturing both the global stress–strain response and the evolution of localized failure. Table 3 presents the calibrated parameters adopted in this study.

3 Numerical Simulation Results and Verification

3.1 Numerical Model Development

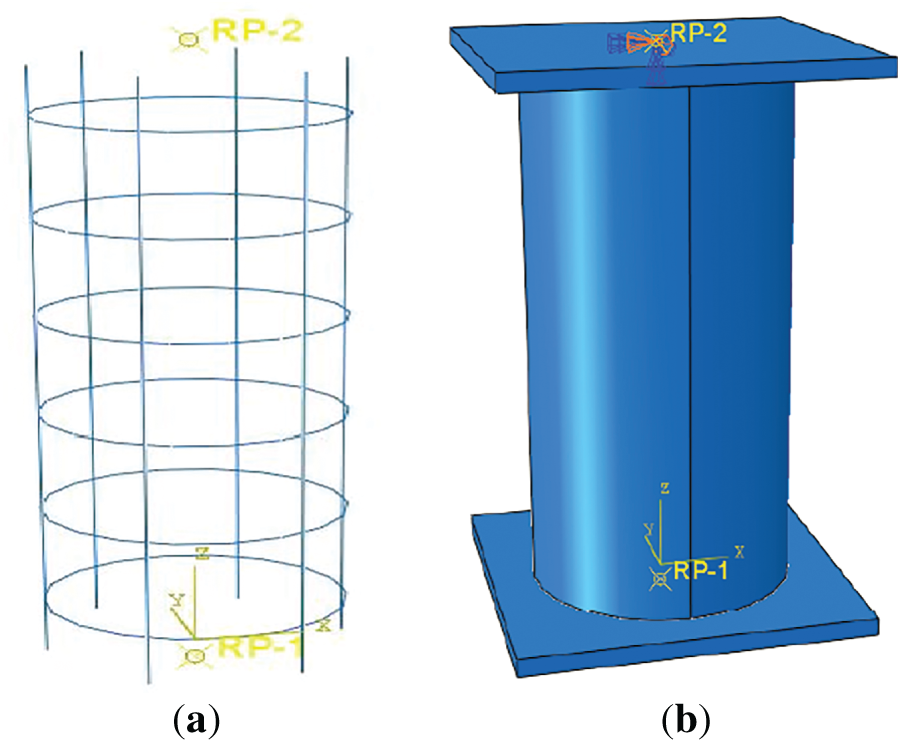

A three-dimensional finite element model of the RC cylinder was established in ABAQUS/Explicit to simulate the thermo–mechanical response. The concrete was meshed with C3D8T coupled temperature–displacement elements, while the reinforcement was modeled using HRB 400-grade steel. The longitudinal reinforcement consisted of 6 bars with a diameter of 6 mm, arranged symmetrically with a nominal concrete cover of 20 mm. The bars were modeled with T3D2 truss elements, which efficiently capture axial behavior and were embedded within the concrete mesh using the embedded region technique. Optional transverse reinforcement (stirrups) was also represented by T3D2 truss elements forming closed loops at designated spacings, included parametrically to assess confinement effects. Fig. 6 illustrates the model geometry, showing (a) the reinforcement cage and (b) the concrete cylinder.

Figure 6: Concrete and steel bars model. (a) Reinforcement components; (b) Concrete components

In the experimental specimens, only longitudinal bars were used, but the numerical framework allowed the inclusion of stirrups for comparative analysis of confinement effects [25]. A perfect bond was assumed in the base model, while bond–slip deterioration was indirectly reflected through temperature-indexed constitutive parameters in subsequent analyses [26]. The Explicit solver was selected for its robustness in handling highly nonlinear responses, progressive cracking, and convergence challenges typical of thermo–mechanical coupling and spalling simulations [27], ensuring stable computation and reliable reproduction of stress–strain and damage evolution up to 700°C.

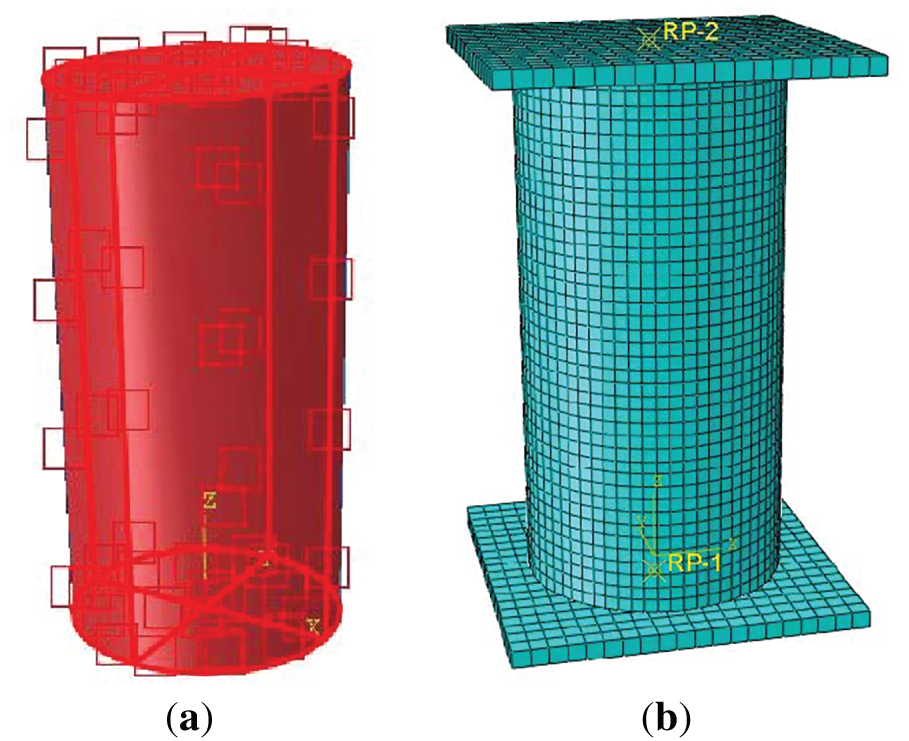

Boundary conditions and mesh discretization are shown in Fig. 7. The bottom face of the cylinder was fixed in displacement to simulate a rigid platen restraint, while a uniform displacement was applied to the top face to represent loading by a compression platen. Frictional contact was defined at the interfaces to avoid unrealistic sliding. The cylinder was discretized with 8-node coupled temperature–displacement elements (C3D8T), and a locally refined mesh was applied in the mid-height region to capture strain localization and crack propagation. The typical element size in critical zones ranged from 5–10 mm.

Figure 7: Boundary conditions and mesh discretization. (a) Boundary conditions; (b) Mesh generation

The temperature-indexed CDP model was first subjected to a mesh sensitivity analysis, which demonstrated that this refinement provided mesh-independent predictions for stress–strain response and damage distribution. Based on this verification, the validated model was used to simulate the thermo–mechanical behavior of concrete cylinders under 20°C–700°C exposure. The analysis was carried out in two sequential stages: a thermal analysis step, in which specimens were exposed to ISO 834 fire heating until the interior reached near-uniform target temperatures, followed by a structural loading step where the cooled specimens were compressed to failure. This sequentially coupled procedure ensured that the simulations closely reproduced the experimental protocol and enabled accurate calibration of the temperature-indexed CDP framework.

3.2 Analysis of Numerical Simulation Results

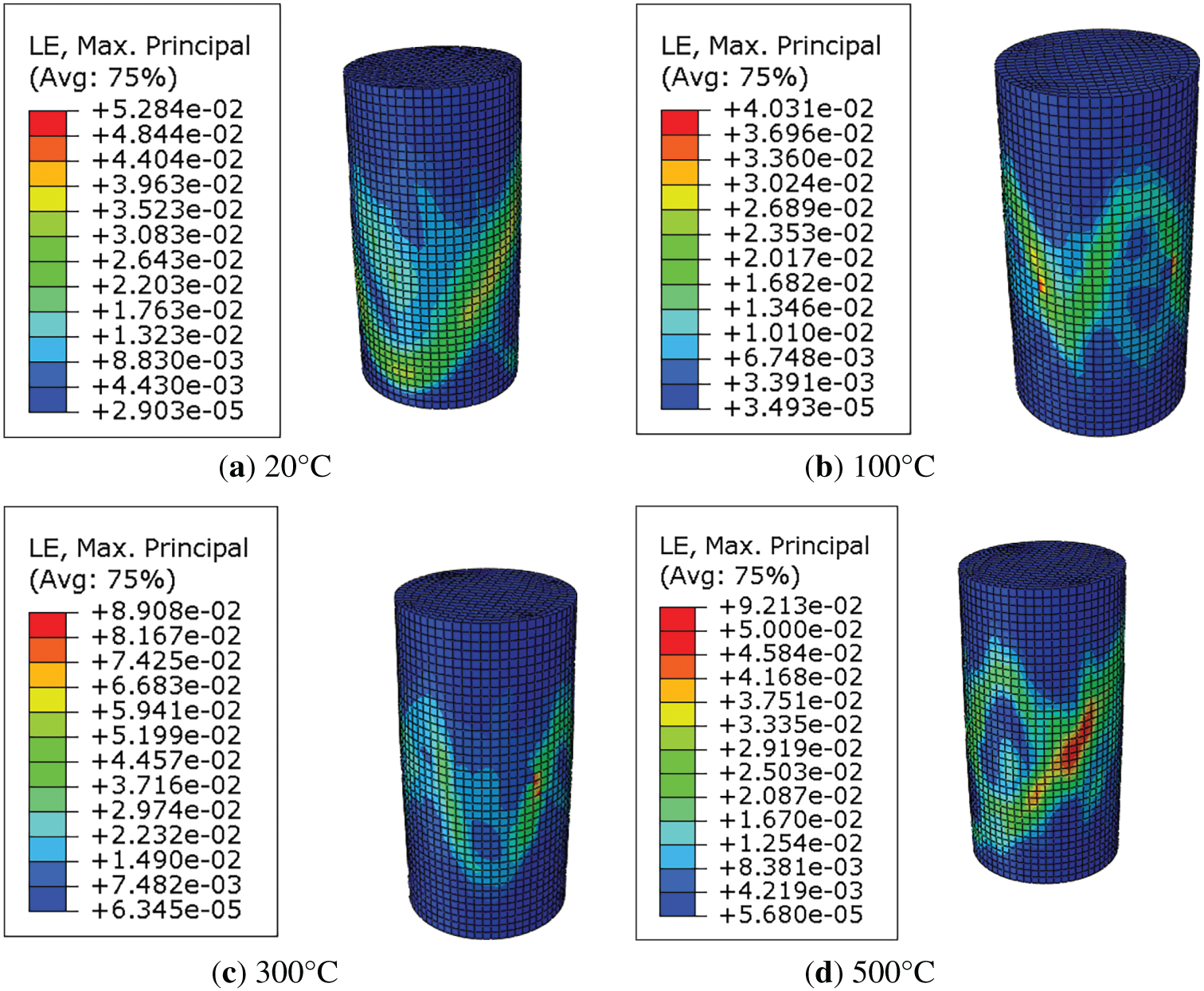

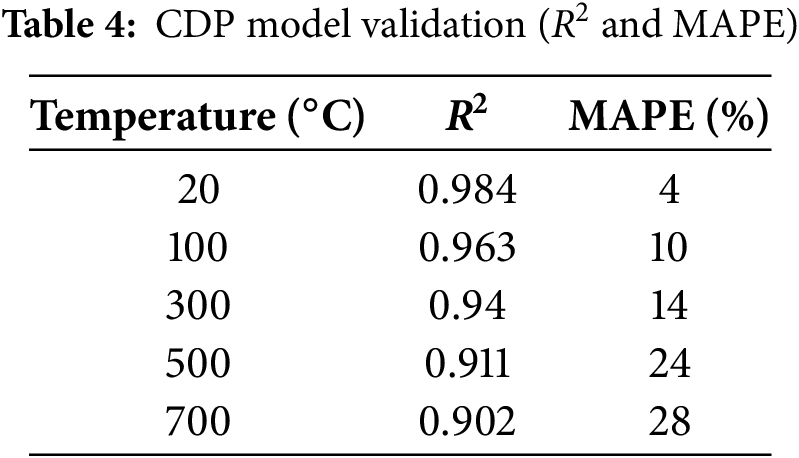

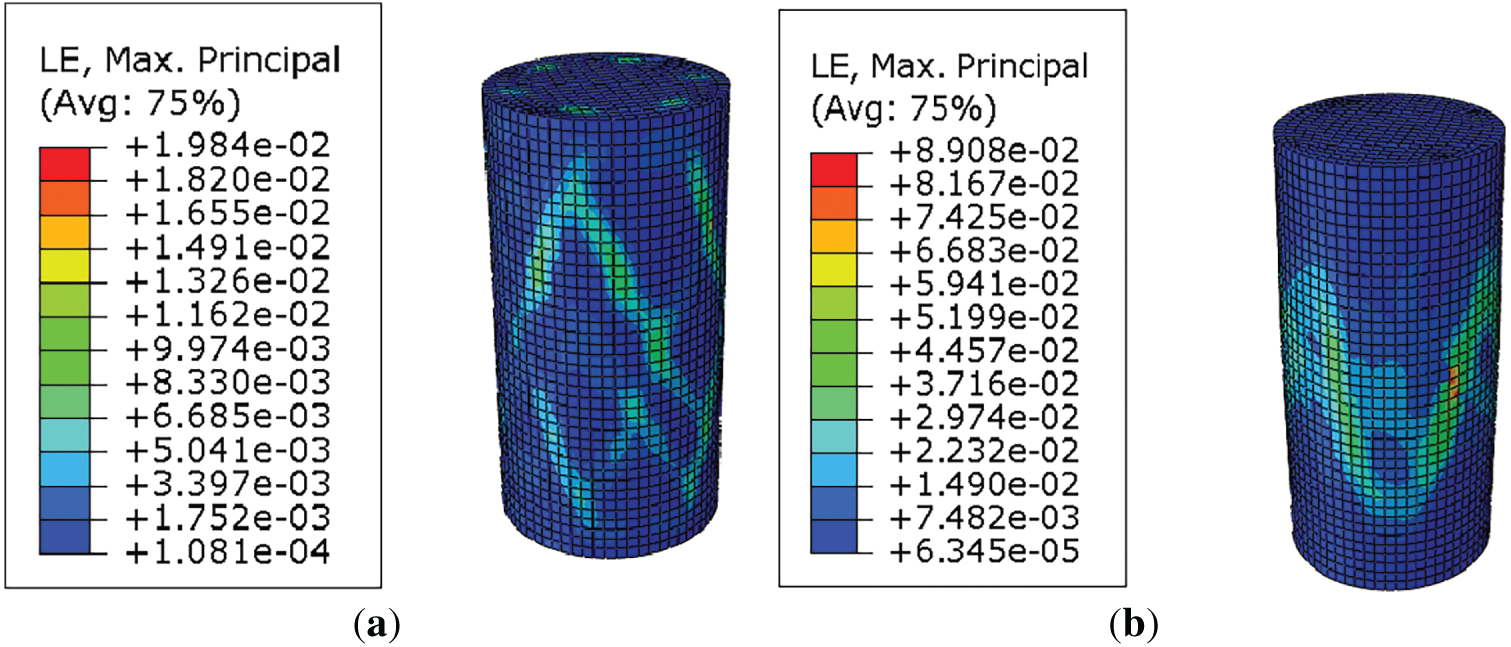

The evolution of strain and damage fields under different thermal exposures is illustrated in Fig. 8. At ambient temperature (20°C), damage was highly localized, forming a dominant vertical shear crack through the cylinder, consistent with the brittle failure mode typically observed in unheated concrete. At 100°C, damage was still concentrated but began to spread slightly, reflecting the onset of microcracking associated with moisture evaporation and initial stiffness reduction. By 300°C, damage contours showed broader distribution across the mid-height region, and crack propagation along the lateral surface became more evident, indicating progressive weakening of the cement paste and aggregate–paste interfaces [28].

Figure 8: Strain damage cloud map under 20°C~700°C

At 500°C, the numerical model predicted a pronounced bulging damage zone at the specimen’s mid-height. Cracks propagated circumferentially along the perimeter, producing a tensile annulus of damage that corresponds to experimentally observed surface cracking prior to cover spalling. This behavior highlights the strong coupling between thermal expansion, stiffness degradation, and localized tensile strain development at elevated temperatures [29]. At 700°C, the damage became widespread throughout the height and cross-section of the cylinder, signifying near-total loss of structural capacity. The simulation captured extensive cracking, distributed strain fields, and weakened confinement, which are consistent with the severely degraded post-fire specimens recorded in testing.

The predicted cloud maps were in close agreement with experimental observations: brittle splitting at ambient conditions, progressive surface cracking at moderate temperatures, and circumferential annular cracking at higher exposures. This consistency confirms that the temperature-indexed CDP framework can realistically reproduce not only global stress–strain responses but also localized damage evolution, providing valuable insights into crack initiation and spalling mechanisms under thermo–mechanical coupling.

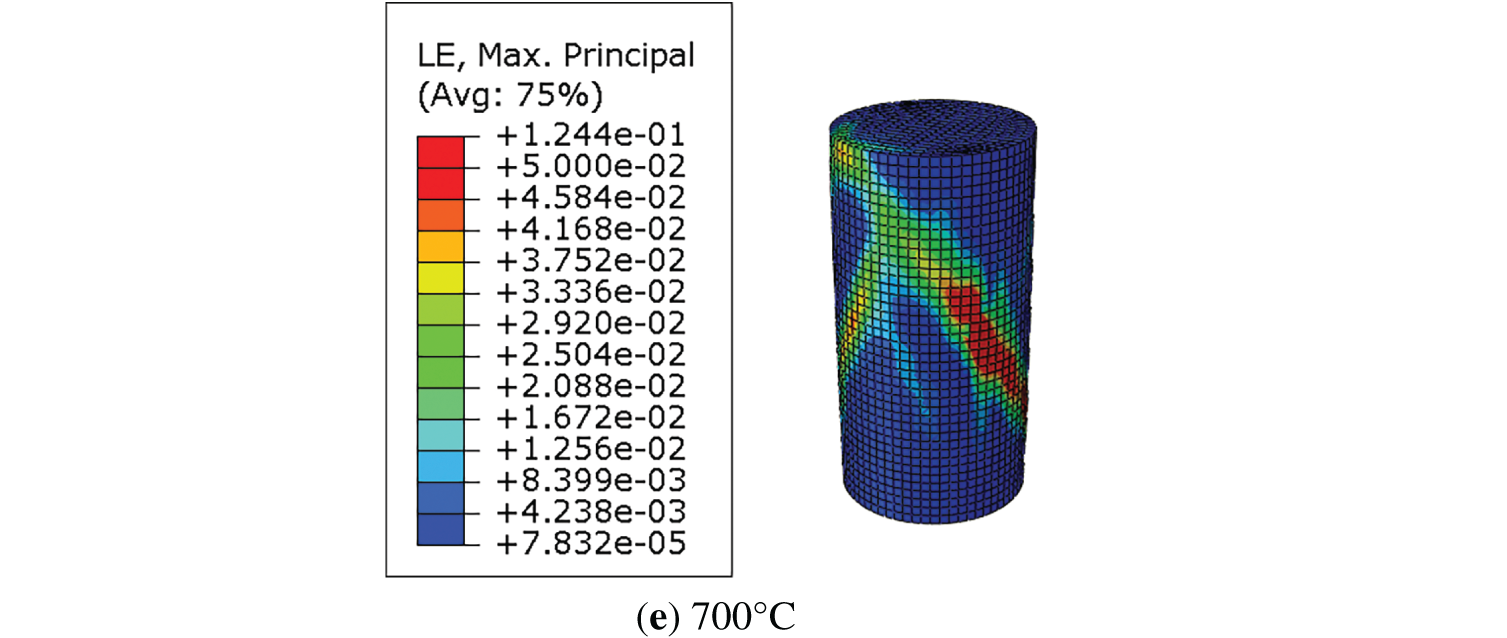

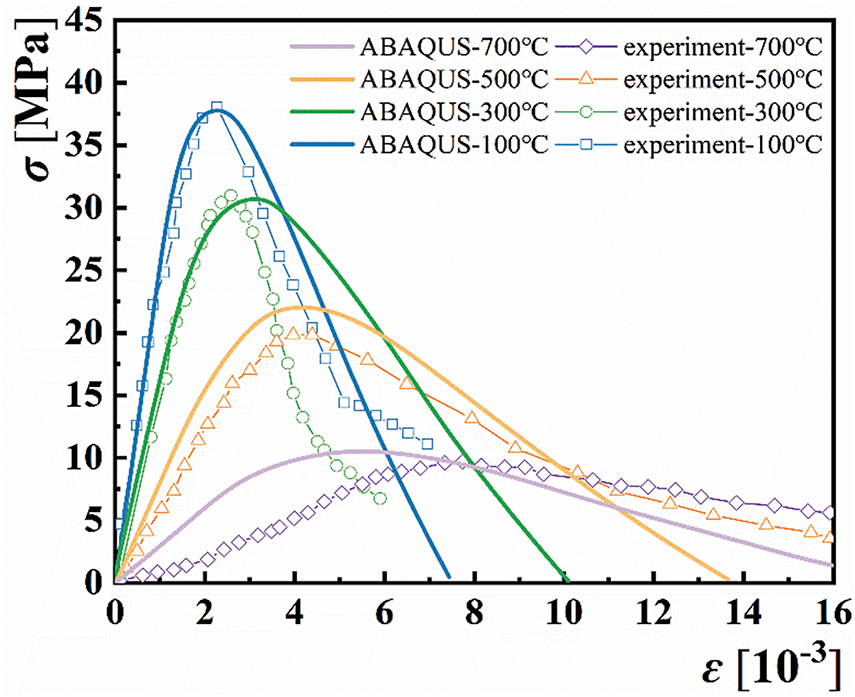

3.2.2 Validation of the Numerical Model and Stress–Strain Response

Fig. 9 presents a comparison between the simulated and experimental stress–strain curves at different temperature levels. At ambient conditions (20°C), the curve shows the characteristic behavior of normal-strength concrete, with a linear-elastic stage up to a peak stress of approximately 40 MPa, followed by an abrupt post-peak softening that reflects brittle failure. As temperature rises, both the initial stiffness and peak stress progressively decrease [30]. At 500°C, the peak compressive strength is reduced to about half of its ambient value, while the curve exhibits a more rounded peak and a gentler post-peak slope, indicative of partial ductility. At 700°C, the residual strength falls to only 15%–20% of the ambient level, accompanied by an extended plastic deformation tail at low stress [31]. The simulated curves reproduce these temperature-dependent trends with high fidelity, closely following the experimental trajectories. Minor deviations are visible in the post-peak region at the highest temperatures, but the overall agreement remains strong.

Figure 9: Simulated vs. experimental stress–strain curves

The quantitative accuracy of the model is summarized in Table 4. The coefficient of determination (R2) between simulation and experiment is 0.984 at 20°C and remains above 0.94 up to 300°C, decreasing slightly to 0.902 at 700°C. The Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) is within 4% at ambient temperature, approximately 14% at 300°C, and 28% at 700°C. These errors are acceptable considering the complexity of thermo–mechanical coupling at elevated temperatures. The model also reproduces the energy absorption capacity with high accuracy, with deviations ≤12% up to 600°C. Collectively, these results demonstrate that the temperature-indexed CDP framework not only captures the key degradation in strength and stiffness but also provides a reliable representation of ductility evolution and toughness loss under elevated thermal exposure.

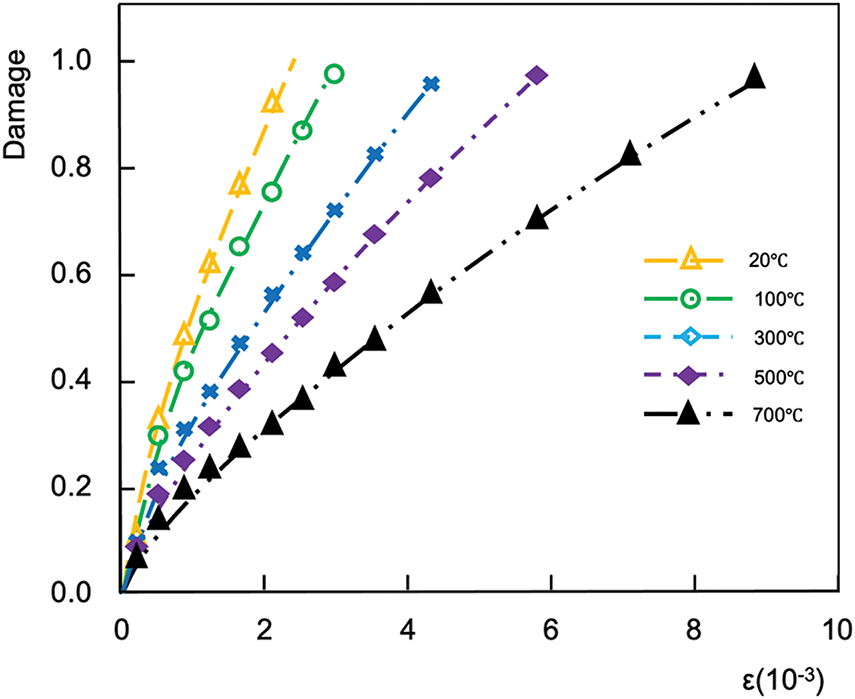

3.2.3 Strain–Damage Relationship

The strain–damage relationship provides direct insight into the progressive degradation of concrete subjected to elevated temperatures. Fig. 10 illustrates the evolution of damage as a function of strain at temperatures ranging from 20°C to 700°C. At ambient temperature (20°C), the curve rises steeply, indicating that damage develops rapidly with increasing strain due to the quasi-brittle nature of concrete. A relatively small strain increment is sufficient to initiate microcracking and drive the damage parameter close to unity.

Figure 10: Damage–strain curves of the material under different temperatures (20°C–700°C)

At 100°C, the curve follows a similar steep trajectory but shows slightly reduced stiffness in the initial stage, reflecting the onset of moisture loss and microstructural instability. At 300°C, the damage curve shifts further to the right, suggesting a delay in the damage initiation threshold. This can be attributed to the combined effects of continued dehydration and stress redistribution, which temporarily enhance apparent ductility despite strength loss.

As temperature increases to 500°C, the curve becomes more gradual, with damage developing more progressively over a larger strain range. This behavior reflects the significant deterioration of stiffness and strength, where microcracks propagate steadily rather than abruptly. Finally, at 700°C, the damage–strain curve is the flattest, demonstrating that the material experiences a prolonged damage accumulation phase before reaching complete failure. At this stage, the cementitious matrix has undergone severe decomposition, and the residual strength is less than 20%–30% of the original capacity.

Overall, these results confirm that temperature has a dual influence: at moderate levels (100°C–300°C), the damage process exhibits delayed initiation and greater ductility, while at higher levels (≥500°C), the loss of cohesion leads to progressive but inevitable degradation. The calibrated damage evolution functions from Fig. 10 are incorporated into the temperature-indexed CDP model, ensuring that both stiffness reduction and ductility changes are realistically reproduced across the full thermal exposure range.

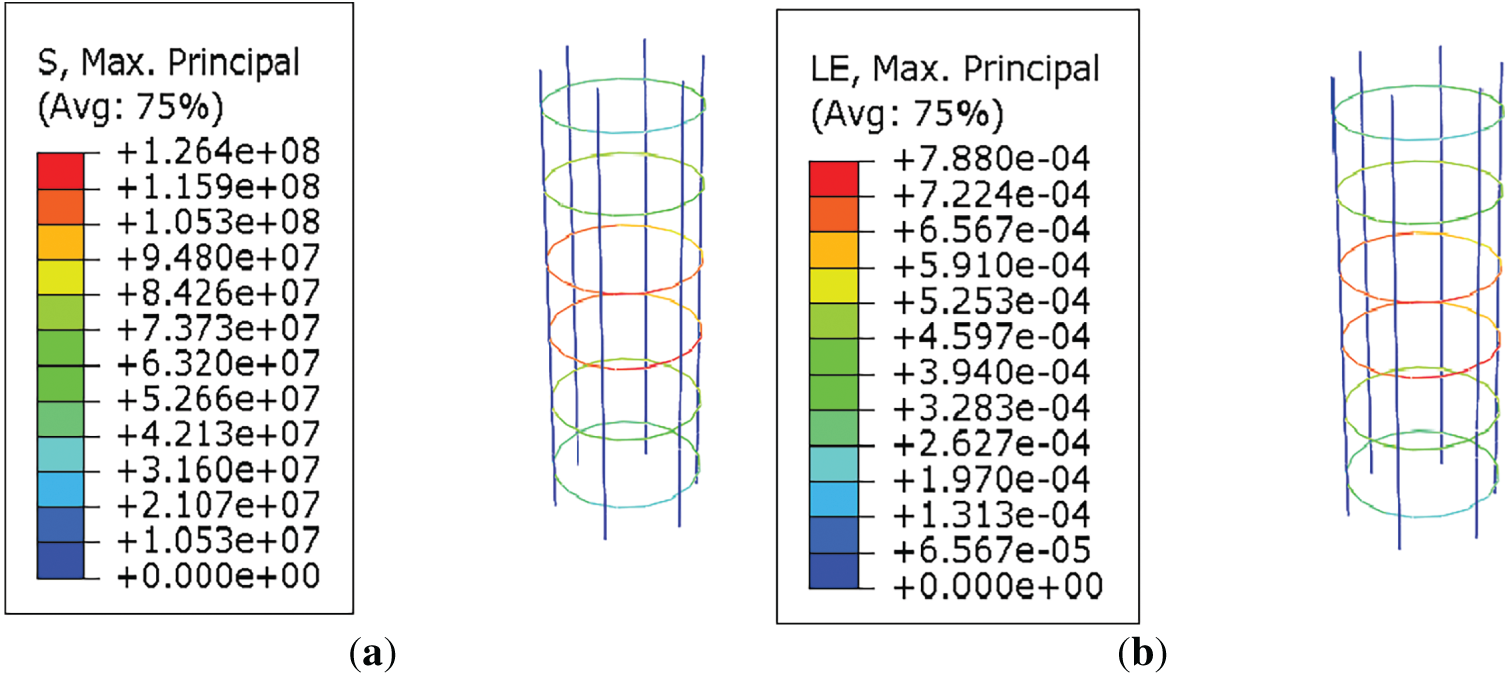

3.2.4 Bond–Slip and Confinement Effects at Elevated Temperatures

The influence of reinforcement detailing, and bond performance plays a decisive role in the thermo-mechanical response of reinforced concrete. To highlight this effect, supplemental analyses were performed to compare the behavior of unreinforced and reinforced concrete cylinders at 300°C, a transitional temperature at which concrete retains approximately 60%–70% of its ambient strength but already exhibits dehydration, stiffness reduction, and progressive microcracking.

Fig. 11 contrasts the strain and damage patterns in plain and reinforced configurations. In the unreinforced specimen, damage localizes into a dominant shear band, leading to complete splitting once cracking initiates, as no mechanism exists to transfer tensile stresses. In contrast, the reinforced specimen containing longitudinal rebars and transverse stirrups develops multiple distributed cracks with narrower widths, allowing the concrete core to remain more intact. The stirrups provide lateral confinement, delaying the growth of localized damage and leading to a more ductile post-peak response.

Figure 11: Comparison of strain damage between concrete and reinforced concrete (300°C). (a) Concrete; (b) Reinforced concrete

Fig. 12 further illustrates the reinforcement cage behavior at the same temperature. Stress contours in the longitudinal rebars (Fig. 12a) indicate that mid-height bars reach stresses near the reduced yield strength, coinciding with severe concrete damage zones. Strain distributions (Fig. 12b) reveal that stirrups near mid-height undergo large deformations, confirming their active confining role prior to bond deterioration. These observations demonstrate the critical contribution of reinforcement to enhancing ductility and toughness at moderate fire exposures.

Figure 12: Stress and strain cloud diagram of steel skeleton (300°C). (a) Stress cloud diagram; (b) Strain cloud diagram

However, the bond–slip mechanism fundamentally governs the long-term effectiveness of confinement. At elevated temperatures, the steel–concrete interface progressively weakens, reducing the anchorage capacity of rebars. While the numerical framework in this study assumes perfect bond, the simulations qualitatively capture the degradation trend: beyond ~600°C, steel strength decreases by more than 50%, and bond deterioration renders confinement largely ineffective. Under these conditions, even members with dense stirrup reinforcement may suffer cover spalling once peripheral tensile annulus cracks propagate.

Overall, these findings highlight the dual role of reinforcement under fire conditions: at moderate temperatures, bond and confinement effects enhance ductility and distribute damage; at higher exposures, bond–slip deterioration and steel softening dominate, diminishing the benefits of confinement. By integrating bond-sensitive considerations into the temperature-indexed CDP framework, the present study provides a more realistic representation of reinforced concrete behavior under thermo-mechanical coupling, offering valuable guidance for fire-resilient design and post-fire structural assessment.

4.1 Temperature–Dependent Degradation of Concrete

The results confirm that C40 concrete exhibits a two-stage degradation regime under thermal exposure. Up to ~400°C, the residual strength and stiffness remain above 60% of the ambient level, indicating that structural integrity is largely preserved. Beyond ~500°C–600°C, however, rapid deterioration occurs, compressive strength decreases to ~45% and stiffness to ~30% of the original values by 600°C, and residual capacity at 700°C falls below ~25% [32]. This two-stage behavior is consistent with empirical formulas and Eurocode 2 provisions, which also identify 500°C–600°C as a critical threshold for structural safety. The findings emphasize the importance of incorporating temperature-indexed degradation laws into constitutive models, rather than applying ambient material properties when assessing fire-damaged structures.

4.2 Strain–Damage Evolution and Crack Mechanisms

The progressive coupling between strain and damage is a defining feature of thermo–mechanical behavior in concrete. The simulations showed that even at relatively low temperatures, an annular tensile strain band forms near the surface, which propagates inward as temperature increases. This band provides a preferential path for crack development and spalling initiation [33]. Correspondingly, the damage–strain curves become flatter with heating, indicating delayed initiation but prolonged accumulation of damage. The strain capacity increases with temperature, reflecting enhanced ductility, but this occurs at the cost of strength. This dual effect—greater deformability but reduced load resistance—must be carefully considered in residual capacity evaluations.

4.3 Bond–Slip and Confinement Effects

The supplemental analyses of reinforced and unreinforced cylinders highlight the decisive role of reinforcement and bond performance. At moderate temperatures (~300°C), longitudinal rebars and stirrups effectively limited crack widths and distributed damage, resulting in improved ductility and higher post-peak toughness. However, at elevated temperatures approaching 600°C–700°C, bond deterioration between steel and concrete, combined with steel strength loss exceeding 50%, significantly reduced the confinement effect [34]. Consequently, even densely reinforced members may suffer cover spalling once peripheral tensile strain bands propagate. These observations demonstrate that bond–slip behavior is a fundamental mechanism governing high-temperature performance and must be incorporated into predictive models for realistic fire assessments.

4.4 Fidelity of the Temperature-Indexed CDP Model

The proposed CDP framework, with temperature-dependent parameters, showed excellent reproducibility of experimental stress–strain curves across the studied range of 20°C–700°C. The model achieved R² values of 0.94–0.98 up to 600°C and ~0.90 at 700°C, while peak stress errors remained within 7%–10%. Energy absorption, expressed as the area under the stress–strain curve, was captured within ~12% of experimental results up to 600°C, demonstrating that the calibrated CDP law reproduces not only strength reduction but also toughness degradation. The mesh sensitivity study confirmed that the model produced mesh-independent results for both global responses and localized damage fields. Together, these findings affirm the robustness and reproducibility of the temperature-indexed CDP framework for thermo–mechanical coupling analysis.

4.5 Implications for Structural Assessment and Design

The combined insights from mechanical degradation, strain–damage coupling, and bond–slip deterioration yield significant implications for fire safety engineering. The 500°C–600°C threshold identified in this study serves as a practical benchmark for post-fire inspections: structural members exposed to this range are likely to have lost most of their load-bearing capacity and should be carefully evaluated for residual serviceability. The presence of surface tensile cracks forming circumferential bands can be treated as an early warning of internal spalling and confinement loss [35]. In engineering applications, these indicators may be identified through visual inspection or non-destructive testing methods such as infrared thermography or acoustic monitoring. Furthermore, the validated CDP framework provides a reliable tool for simulating residual capacity under thermo–mechanical loading, offering engineers a quantitative basis for repair, strengthening, or replacement decisions.

4.6 Broader Engineering Significance

The study highlights that fire-exposed reinforced concrete behavior cannot be adequately described by strength reduction factors alone. Instead, a comprehensive model must account for progressive microstructural damage, strain-dependent ductility, and bond–slip deterioration at elevated temperatures. The proposed temperature-indexed CDP framework fulfills this need, bridging empirical degradation data with constitutive modeling and structural-level predictions. Beyond columns, the approach can be generalized to beams, slabs, and wall elements, provided that reinforcement detailing and boundary conditions are appropriately incorporated. As such, the findings not only advance scientific understanding of thermo–mechanical coupling but also deliver actionable guidance for improving fire resilience in reinforced concrete infrastructure.

This study developed a temperature-indexed Concrete Damage Plasticity (CDP) framework incorporating bond–slip effects to investigate the thermo–mechanical behavior of reinforced concrete up to 700°C. The key conclusions are as follows:

(1) Two-Stage Thermal Degradation

C40 concrete exhibited a distinct two-regime response: moderate stiffness and strength loss up to ~400°C, followed by sharp degradation beyond 500°C–600°C. At 600°C, residual load capacity fell to ~45% of its ambient value and axial stiffness was reduced by ~70%. By 700°C, residual strength dropped to ~20%–25%, confirming that 500°C–600°C represents a critical threshold for structural safety.

(2) Strain–Damage Coupling and Cracking

Thermal exposure induced an annular tensile strain band at the cover surface, which thickened and propagated inward with increasing temperature. Corresponding damage–strain curves flattened progressively, requiring larger strains to reach the same damage level. This behavior explains the observed transition from brittle failure at ambient conditions to more ductile but weakened responses at high temperatures.

(3) Thermal Gradients and Restraints

Supplemental analyses revealed that transverse reinforcement and longitudinal rebars improve ductility and delay spalling at moderate temperatures (~300°C) by distributing cracks and confining the core. However, beyond ~600°C, bond deterioration and steel softening (>50% strength loss) significantly reduce confinement efficiency, leading to cover spalling even in densely reinforced members.

(4) Validation of Temperature-Indexed CDP

The temperature-indexed CDP model reproduced experimental stress–strain responses across 20°C–700°C with high accuracy (R2 ≈ 0.94–0.98 up to 600°C; ≈0.90 at 700°C). Peak stress errors remained within 7%–10%, and energy absorption was captured within ~12%. The model successfully simulated both global load–displacement curves and localized strain/damage patterns, confirming its robustness and reproducibility.

(5) Engineering Significance

The findings underscore the importance of adopting temperature-dependent constitutive laws in post-fire assessments. The identified 500°C–600°C threshold provides a practical benchmark for evaluating residual capacity in fire-exposed RC members. The detection of perimeter tensile-strain bands can serve as an indicator of impending spalling during inspections. The validated framework thus offers engineers a reliable tool for fire-resilient design, residual capacity evaluation, and repair strategies in reinforced concrete columns, beams, and slabs subjected to thermo–mechanical coupling.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Wu Feng and Tengku Anita Raja Hussin; methodology, Wu Feng; software, Wu Feng; validation, Wu Feng, Tengku Anita Raja Hussin and Xu Yang; formal analysis, Wu Feng; investigation, Wu Feng; resources, Wu Feng; data curation, Wu Feng; writing—original draft preparation, Wu Feng; writing—review and editing, Wu Feng, Tengku Anita Raja Hussin and Xu Yang; visualization, Wu Feng; supervision, Tengku Anita Raja Hussin and Xu Yang; project administration, Wu Feng. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Author, [Wu Feng], upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Çavdar A. A study on the effects of high temperature on mechanical properties of fiber reinforced cementitious composites. Compos Part B Eng. 2012;43(5):2452–63. doi:10.1016/j.compositesb.2011.06.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Gong F, Zhang Y, Zhang Z, Zhang L, Zhang J, Li J. An overview on spalling behavior, mechanism, residual strength, and mitigation strategies of fiber-reinforced concrete at high temperatures. Front Mater. 2023;5:1258195. doi:10.3389/fmats.2023.1258195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Shahraki M, Hua N, Elhami-Khorasani N, Tessari A, Garlock M. Residual compressive strength of concrete after exposure to high temperatures: a review and probabilistic models. Fire Saf J. 2023;135:103698. doi:10.1016/j.firesaf.2022.103698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Babalola OE, Awoyera P, Le D-H, Romero LMB. A review of residual strength properties of normal and high strength concrete exposed to elevated temperatures: impact of materials modification on behaviour of concrete composite. Constr Build Mater. 2021;296:123448. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.123448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Li L, Wang H, Wu J, Jiang W. A thermomechanical coupling constitutive model of concrete including elastoplastic damage. Appl Sci. 2021;11(2):604. doi:10.3390/app11020604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Gao Z, Zhang L, Zhang Z, Zhang Y, Li J, Zhang J. Simulation of thermal expansion mismatch at high temperature in concrete. Mater Lett. 2023;333:133628. doi:10.1016/j.matlet.2022.133628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Zhang J, Chen J, Zhang R, Guo R. A numerical investigation of thermal-induced explosive spalling behavior of a concrete material using cohesive interface model. Front Phys. 2022;10:857381. doi:10.3389/fphy.2022.857381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Boucetta TA, Meftah H, Ayat A, Melais FZ, Berredjem L, Arabi N. Residual physico-mechanical properties of polypropylene fibers-reinforced recycled aggregates concrete (FRRAC) under elevated temperatures. Eur J Environ Civ Eng. 2025;29(8):1577–603. doi:10.1080/19648189.2024.2448664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Meftah H, Arabi N. Effects of elevated temperatures’ exposure on the properties of concrete incorporating recycled concrete aggregates. Constr Build Mater. 2024;411:134612. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.134612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Revilla-Cuesta V, Skaf M, Chica JA, Ortega-López V, Manso JM. Quantification and characterization of the microstructural damage of recycled aggregate self-compacting concrete under cyclic temperature changes. Mater Lett. 2023;333:133628. doi:10.1016/j.matlet.2022.133628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Revilla-Cuesta V, Hurtado-Alonso N, Manso-Morato J, Serrano-López R, Manso JM. Effects of temperature and moisture fluctuations for suitable use of raw-crushed wind-turbine blade in concrete. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2024;31:37757–76. doi:10.1007/s11356-024-33720-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Thomas C, Tamayo P, Setién J, Cimentada AI, Polanco JA. Effect of high temperature and accelerated aging in high-density concrete for radiation shielding. Constr Build Mater. 2021;272:121920. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.121920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Sainz-Aja JA, Carrascal IA, Polanco JA, Thomas C. Effect of temperature on fatigue behaviour of self-compacting recycled aggregate concrete. Cem Concr Compos. 2022;125:104309. doi:10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2021.104309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Rukavina M, Gabrijel I, Grubeša I, Mladenovič A. Residual compressive behavior of self-compacting concrete after high temperature exposure—influence of binder materials. Materials. 2022;15:6222. doi:10.3390/ma15062222. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Cheng F, Kodur V, Wang T. Stress-strain curves for high strength concrete at elevated temperatures. J Mater Civ Eng. 2004;16(1):84–90. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)0899-1561(2004)16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Wang Y, Pan Z, Zeng B, Xu Q. Cyclic creep model of concrete based on Kelvin chain under fatigue loads. Constr Build Mater. 2024;417:135255. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.135255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Lubliner J, Oliver J, Oller S, Oñate E. A plastic-damage model for concrete. Int J Solids Struct. 1989;25(3):299–326. doi:10.1016/0020-7683(89)90050-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Mazars J. A new 3D damage model for concrete under monotonic, cyclic and dynamic loadings. Mater Struct. 2015;48(12):3779–93. doi:10.1617/s11527-014-0439-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Bažant ZP, Planas J. Fracture and size effect in concrete and other quasibrittle materials. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 1998. [Google Scholar]

20. Ahmad MIR, Irawati IS, Awaludin A, Siswosukarto S. Thermomechanical analysis of cement hydration effects in multi-layered pier head concrete: finite element approach. J Eng Technol Sci. 2024;56(5):625–38. doi:10.5614/j.eng.technol.sci.2024.56.5.7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Fakeh M, Jawdhari A, Fam A. Calibration of ABAQUS concrete damage plasticity (CDP) model for UHPC material. Int Interact Symp Ultra-High Perform Concr Pap. 2023;3(1):53. doi:10.21838/uhpc.16675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Saha S, Serati M, Sahoo DR, Maluk C. Experimental and numerical analysis on the thermo-mechanical stresses triggering the onset of fire-induced concrete spalling. Fire Technol. 2025;61:3665–86. doi:10.1007/s10694-025-01749-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Hawileh RA, Quadri SS, Abdalla JA, Assad M, Thomas BS, Craig D, et al. Residual mechanical properties of recycled aggregate concrete at elevated temperatures. Fire Mater. 2024;48(1):138–51. doi:10.1002/fam.3168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Chang YF, Chen YH, Sheu MS, Yao GC. Residual stress-strain relationship for concrete after exposure to high temperatures. Cem Concr Res. 2006;36(11):1999–2005. doi:10.1016/j.cemconres.2006.05.029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Kachkouch FZ, Noberto CC, de Albuquerque Lima Babadopulos LF, Melo ARS, Machado AML, Sebaibi N, et al. Fatigue behavior of concrete: a literature review on the main relevant parameters. Constr Build Mater. 2022;338:127510. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.127510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Lee J, Fenves GL. Plastic-damage model for cyclic loading of concrete structures. J Eng Mech. 1998;124(8):892–900. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)0733–9399(1998)124:8(892). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Xu K, Zhang N, Yin ZY, Li K. Finite element-integrated neural network for inverse analysis of elastic and elastoplastic boundary value problems. Comput Methods Appl Mech Eng. 2025;436:117695. doi:10.1016/j.cma.2025.117695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Wang Z, Wang J, Wu HN, Zhang R, Zhang GY, Zhang F, et al. Investigation of the microstructure, mechanical Properties and thermal degradation kinetics of EPDM under thermo-stress conditions used for joint sealing of floating prefabricated Concrete Platform of Offshore Wind Power. Constr Build Mater. 2025;485:141897. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2025.141897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Zhang N, Xu K, Yin ZY, Li KQ. Transfer learning-enhanced finite element-integrated neural networks. Int J Mech Sci. 2025;290:110075. doi:10.1016/j.ijmecsci.2025.110075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Wang Z, Lyu HM, Zhang R. Water-swelling behavior and self-reinforcing mechanical properties of joint sealing material in underground prefabricated structure. Constr Build Mater. 2025;490:142451. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2025.142451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Ning J, Zhang L, Xu X. Virtual simulation for the dynamic response of concrete blocks under blast loading. Vis Comput. 2025;41(7):5171–87. doi:10.1007/s00371-024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Tao J, Yang X-G, Lei Y, Wang C. Capturing rate-and temperature-dependent behavior of concrete using a thermodynamically consistent viscoplastic-damage model. Constr Build Mater. 2024;422:135791. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2024.135791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Xu L, Tang C, Li H, Wu K, Zhang Y, Yang Z. Hydration characteristics assessment of a binary calcium sulfoaluminate-anhydrite cement related with environment temperature. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2022;147(4):3053–61. doi:10.1007/s10973-021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Wang Q, Yao B, Lu R. Behavior deterioration and microstructure change of polyvinyl alcohol fiber-reinforced cementitious composite (PVA-ECC) after exposure to elevated temperatures. Materials. 2020;13(23):5539. doi:10.3390/ma13235539. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Wosatko A, Genikomsou A, Pamin J, Polak MA, Winnicki A. Examination of two regularized damage-plasticity models for concrete with regard to crack closing. Eng Fract Mech. 2018;194:190–211. doi:10.1016/j.engfracmech.2018.03.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools