Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

The cost and guideline adherence of direct-to-consumer telemedicine companies offering gender-affirming hormone therapy

1 Urology Institute, University Hospitals, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, Cleveland, OH 44106, USA

2 Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH 44106, USA

3 Department of Urology, Memorial Healthcare System, Hollywood, FL 33021, USA

4 Department of Urology, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, IL 60611, USA

* Corresponding Author: Nicholas Sellke. Email:

Canadian Journal of Urology 2025, 32(2), 89-94. https://doi.org/10.32604/cju.2025.065004

Received 08 August 2024; Accepted 03 March 2025; Issue published 30 April 2025

Abstract

Introduction: Direct-to-consumer (DTC) telemedicine has emerged as an option for transgender patients seeking gender affirming hormone therapy (GAHT). We aimed to characterize the healthcare services provided by DTC telemedicine companies offering GAHT and to compare their costs to a tertiary care center. Methods: We identified DTC telemedicine platforms offering GAHT via internet searches and extracted information from their websites related to evaluation, treatment, monitoring, and cost. Cost of the DTC GAHT was compared to cost for comparable services at a tertiary care center. Results: Six DTC companies were identified. All platforms utilized an informed consent model without prerequisite mental health evaluation for GAHT. Platforms did not provide comprehensive mental health services. All platforms endorsed the use of regular follow up visits throughout the treatment period although interval of laboratory assessment varied. Cost estimates were comparable for uninsured patients and higher compared to those for insured patients. Cost estimates were lowest with private and public insurance at the tertiary center. Conclusions: DTC telemedicine platforms offering GAHT appear to be in line with the recently released World Professional Association for Transgender Health standards of care regarding the laboratory evaluation and monitoring, but it is unclear whether they are compliant with other recommendations. These platforms offer competitive costs for TGD patients without insurance.Keywords

Transgender and gender diverse (TGD) individuals encounter significant disparities in medical care compared to cisgender individuals.1 Common barriers to care include physician unawareness of transgender-specific needs, prior negative experiences with the traditional healthcare system, and an inability to pay for transition-related services.2

In an effort to reduce requirements and barriers to care, the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) made notable changes in the Standards of Care, Version 8 (SOC8) released in 2022. SOC8 references telehealth as being an acceptable mode of evaluation currently being pioneered as it may enhance access to care. The requirement of mental health counseling prior to gender-affirming medical and surgical care has been removed but it is specified that providers should be able to identify and assess mental health conditions that could negatively impact outcomes prior to gender-affirming medical and surgical care. Additionally, they promote the informed consent model which involves thorough discussions with the patient to support the person in making a decision based on accurate information and expectations.3

Gender-affirming care for TGD individuals can be costly. Unfortunately, TGD people are significantly less likely to carry health insurance than cisgender men or women.4 Only 34 states cover transgender care under Medicaid insurance.5 Even for those with insurance, 25% report being denied coverage when seeking hormone treatment. Unsurprisingly, a third of TGD individuals report not seeing a doctor when needed due to inability to afford it.6

Direct-to-consumer (DTC) telemedicine is an increasingly popular form of virtual healthcare, typically self-pay in nature. Several DTC platforms specializing in gender affirming hormone therapy (GAHT) have emerged. While these online companies may increase access to healthcare tailored to the specific needs of TGD people, their associated costs have not been examined. We sought to characterize the healthcare services provided by DTC telemedicine companies offering GAHT and to compare their costs to those that may be encountered at a tertiary care center.

A systematic internet search was performed in April 2023 using the Google search engine to identify United States-based DTC telemedicine platforms offering GAHT. Sixteen different terms related to GAHT were searched (Table S1). The first page of each search was assessed for GAHT platforms. The search was limited to the first page as user traffic decreases by 95% after the first 10 results.7 Information was extracted from DTC GAHT websites including cost of membership, initial and follow up visits, laboratory tests, and medication as wells as frequency of laboratory testing and follow up visits. Whether or not insurance was accepted was also gathered. Disclosed frequencies of follow up visits and laboratory assessments were compared to those recommended by the WPATH SOC8.3

Total costs for the first year of GAHT was calculated using disclosed costs for provider visits, laboratory assessments, and medications. For platforms only providing medication prescriptions, costs were estimated using prices from GoodRx.com. Using a single tertiary center’s cost estimator tool,8 first-year costs for comparable services were estimated for a model patient with no insurance, private insurance, and Medicaid. The lab tests included in the analysis were a complete blood count and total testosterone for the testosterone therapy model and estradiol and total testosterone for the estrogen therapy model, consistent with laboratory recommendations as per the SOC8. Medication costs for these models were estimated using GoodRx.com.

The study did not require approval of our institution’s institutional review board as it utilized publicly available data and no human subjects or protected health information.

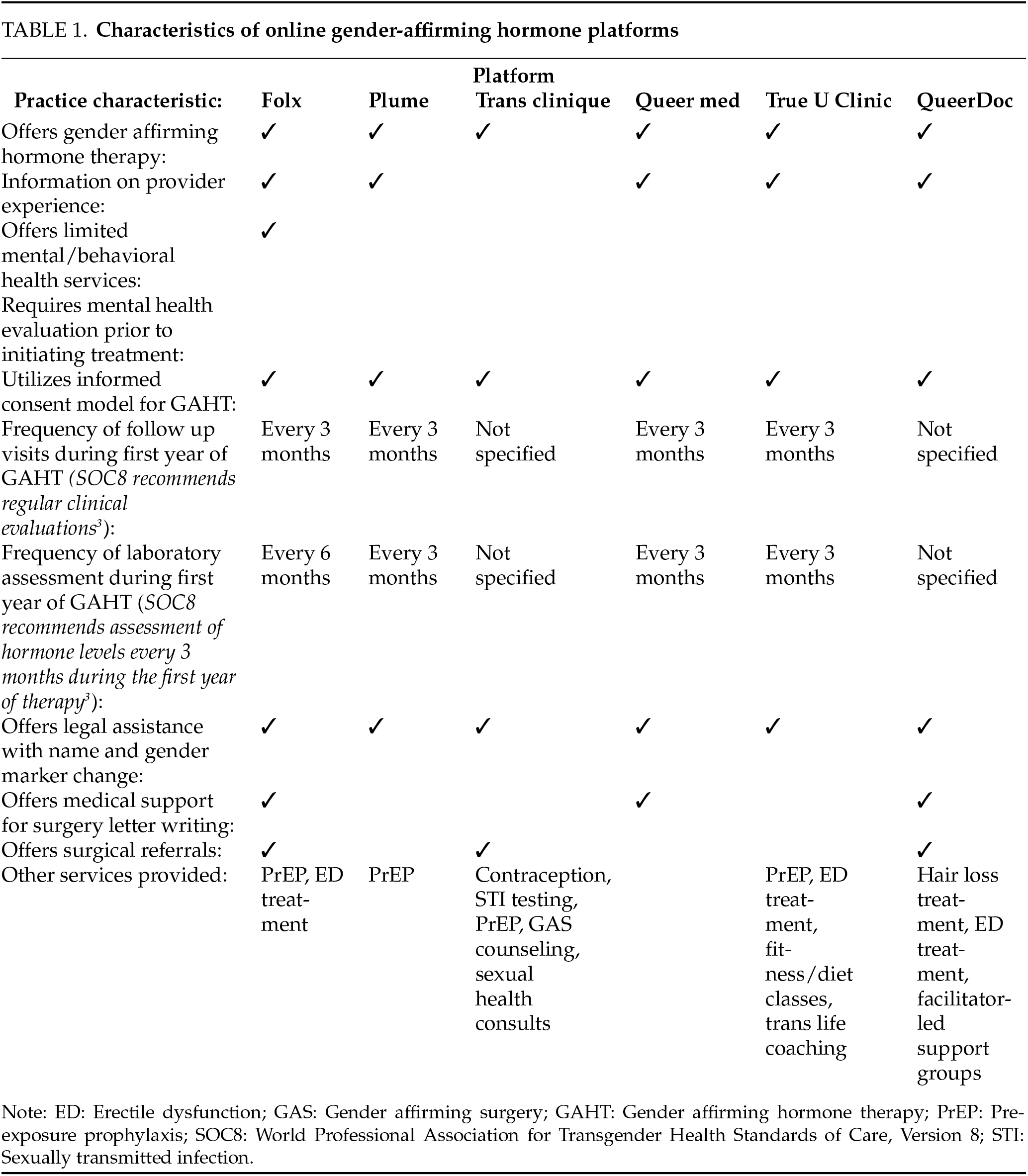

Six DTC companies offering GAHT were identified (Table 1). Two companies offered puberty blockers in addition to GAHT. Other gender services included legal assistance for name and gender marker change, medical letter writing for gender affirming surgery, and surgical referrals. Initial consultation duration was stated for three platforms and ranged from 15 to 30 min. All platforms utilized an informed consent model without prerequisite mental health evaluation for GAHT. Only Folx offered limited mental or behavioral health services including treatment of acute anxieties such as performance anxiety and one-time refills of antidepressant medications, but none offered comprehensive mental health care. All but one platform had a list of nonaffiliated mental health providers available to patients.

All platforms endorsed the use of regular follow up visits throughout the treatment period. During the first year of treatment, laboratory assessment is performed every 3 months by five platforms (83.3%) and every 6 months by one platform (16.7%). Four of the DTC companies used a monthly subscription model with fees ranging from $79.00 to $139.00 per month. The estimated first-year cost of GAHT via the DTC telemedicine platforms without insurance ranged from $948.00 to $1428.00 for oral estradiol therapy and $1162.00 to $1668.00 for intramuscular testosterone therapy. Two platforms (33.3%) accepted limited insurance plans for services. Three other platforms (50.0%) allowed for insurance billing of laboratory fees only. One platform did not accept insurance.

In comparison, these costs were estimated to be $1184.20 and $1216.40, respectively, at the tertiary center without insurance. With insurance the annual cost of testosterone therapy was estimated at $570.00 and $216.00 with private and public insurance, respectively. The yearly cost of estradiol therapy at the tertiary care hospital was $399.00 with private insurance and $2.00 with public insurance (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1. Bar graph comparing the estimated annual price of gender-affirming hormone therapy from the six companies identified as well as a tertiary care center utilizing different payment methods (DTC: direct-to-consumer)

DTC telemedicine companies offer GAHT for TGD people utilizing an informed consent model and regular virtual follow up with laboratory assessment every three to six months. Platforms appear to create an inclusive and supportive environment by offering services specifically to TGD patients, including healthcare provided by gender-diverse clinicians. Platforms typically promise to create a hormonal treatment plan tailored to the patient’s goals whether they are transmasculine, transfeminine, or nonbinary. Several legal and non-medical services are also offered to support needs specific to the TGD community.

While the virtual access and tailoring of care may help overcome several non-financial barriers to healthcare for this population such as travel and anticipated discomfort of in-office care, the associated costs are an important consideration. A recent study examining population-based insurance coverage trends found that 23.5% TGD people were uninsured, as compared to 16.1% and 12.8% of cis-men and women, respectively.4 Authors also found that 28.4% of TGD people who were considered to likely be eligible for Medicaid did not carry insurance. Importantly, DTC platforms appear to offer care at costs comparable to what may be encountered at a tertiary center without insurance, though more expensive than the costs for insured patients.

These DTC platforms in our study were in line with several notable recommendations in the new SOC8 guidelines. Specifically, telehealth has been added as an acceptable platform for patient assessment. The informed consent model is also promoted in SOC8 which was utilized by all the DTC platformed assessed which encourages informed decisions by the patients instead of relying on mental health evaluations before treatment. While some platforms followed the WPATH recommendation of lab assessments every 3 months, one platform only assess lab values every 6 months.

The present study was not able to assess compliance of DTC platforms with several other recommendation in SOC8. The WPATH recommends that the provider should hold at least a master’s degree, be experienced in GAHT, and utilize a multidisciplinary team in their approach. Most of the programs provided information on the experience of their clinicians, but no programs had surgical or speech professionals on the roster of providers. These specialties are specifically mentioned as part of the multidisciplinary team in SOC8.

While the requirement of the mental health evaluation prior to GHAT has been removed, providers should be able to identify co-existing mental health and psychological concerns separate from the patient’s gender incongruence. None of the platforms provided comprehensive mental health services or details when a referral was required raising suspicion if these recommendations are followed.

It is also not clear what target levels are being used for hormone therapy and if the patients are receiving pre-treatment counseling on the fertility preservation. Prior study on DTC testosterone treatment for cis men found providers failed to provide counseling on risks and benefits of testosterone therapy and targeted supratherapeutic levels discordant with guidelines.9 The SOC8 referred to telehealth being pioneered as a healthcare setting for transgender care as it may increase access to care. It is uncertain how the inability of the DTC platforms to assess the patient in-office and conduct a proper physical exam, in addition to the other possible shortcomings listed above, will affect patient outcomes.

There are notable limitations to this study. The current report lacks representation of a community healthcare setting, and cost estimates utilizing insurance coverage at the DTC platforms were unable to be estimated. Tertiary center cost estimates utilized a single institution with a single private insurance and Medicaid model, reducing generalizability. In addition, our observations are drawn from each company’s website, and thus we are unable to account for platforms’ real-life practices. We were unable to gather information regarding the treatment regimens prescribed by the platforms.

DTC telemedicine platforms offering GAHT appear to be at least partly in line with the 2022 WPATH SOC8 guidelines related to prescription and monitoring of GAHT however it remains to be confirmed if they are compliant with recommendations on a multidisciplinary team approach and ability to assess mental health. The platforms offer competitive costs for TGD patients without insurance. These platforms may provide an opportunity to increase access to culturally competent transition-related care for TGD people.

Acknowledgement

None.

Funding Statement

The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions

Conception: Erin Jesse, Justin M. Dubin, Nannan Thirumavalavan; Data Collection: Erin Jesse, Neha S. Basti, Janvi Ramchandra; Data Analysis: Nicholas Sellke, Erin Jesse; Drafting Manuscript: Nicholas Sellke, Erin Jesse; Editing and Revising Manuscript: Nicholas Sellke, Erin Jesse, Tomislav D. Medved, Justin M. Dubin, Nannan Thirumavalavan; Supervision: Robert E. Brannigan, Joshua A. Halpern, Nannan Thirumavalavan; Approval of Final Version: All authors. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials

Study data will be made available to interested parties upon request to the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval

The study was exempt by the University Hospital’s IRB as it used only publicly available information and no human subjects.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials

The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/cju.2025.065004/s1.

References

1. Edmiston EK, Donald CA, Sattler AR, Peebles JK, Ehrenfeld JM, Eckstrand KL. Opportunities and gaps in primary care preventative health services for transgender patients: a systematic review. Transgend Health 2016;1(1):216–230. doi:10.1089/trgh.2016.0019. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Lerner JE, Robles G. Perceived barriers and facilitators to health care utilization in the united states for transgender people: a review of recent literature. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2017;28(1):127–152. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

3. Coleman E, Radix AE, Bouman WP et al. Standards of care for the health of transgender and gender diverse people, version 8. Int J Transgend Health 2022;23(Suppl 1):S1–259. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

4. Downing J, Lawley KA, McDowell A. Prevalence of private and public health insurance among transgender and gender diverse adults. Med Care 2022;60(4):311–315. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

5. Zaliznyak M, Jung EE, Bresee C, Garcia MM. Medicaid programs provide coverage for gender-affirming hormone therapy and gender-affirming genital surgery for transgender patients?: a state-by-state review, and a study detailing the patient experience to confirm coverage of services. J Sex Med 2021;18(2):410–422. [Google Scholar]

6. James SE, Herman JL, Rankin S, Keisling M, Mottet L, Anafi M. The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. Washington, DC, USA: National Center for Transgender Equality; 2016. [Google Scholar]

7. Chitika. Chitika insights: the value of google result positioning. Westborough, MA, USA; 2013. [Internet]. [cited 2023 Oct 18]. Available from: https://research.chitika.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/chitikainsights-valueofgoogleresultspositioning.pdf. [Google Scholar]

8. University Hospitals. Estimate your cost for uh services. [Internet]. [cited 2022 Sep 27]. Available from: https://www.uhhospitals.org/patients-and-visitors/billing-insurance-and-medical-records/price-estimates#getstarted. [Google Scholar]

9. Dubin JM, Jesse E, Fantus RJ et al. Guideline-discordant care among direct-to-consumer testosterone therapy platforms. JAMA Intern Med 2022;182(12):1321–1323. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools