Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Simple prostatectomy followed by radiation therapy for prostate cancer: a novel treatment pathway for men with marked prostatomegaly and prostate cancer: a series of cases

1 Department of Urology, Duke University Hospital, Durham, NC 27710, USA

2 Department of Urology, University of Texas Southwestern, Dallas, TX 75390, USA

3 School of Medicine, Duke University, Durham, NC 27710, USA

4 School of Medicine, University of Texas Southwestern, Dallas, TX 75390, USA

5 Department of Radiation Oncology, University of Texas Southwestern, Dallas, TX 75390, USA

* Corresponding Author: Tara Morgan. Email:

Canadian Journal of Urology 2025, 32(4), 309-315. https://doi.org/10.32604/cju.2025.063408

Received 14 January 2025; Accepted 09 June 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

Background: Radical prostatectomy has long been the treatment of choice for men with clinically significant prostate cancer (PCa) in those with concurrent significant lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS). For men who meet this description with marked prostatomegaly, we present a multi-institutional proof of concept study describing an alternative pathway of robotic simple prostatectomy (RASP) followed by external beam radiation therapy (EBRT) for the treatment of clinically significant prostate cancer. Methods: A retrospective study was performed of 17 patients with PCa who underwent RASP followed by EBRT at two institutions from 2015–2023. Demographic, peri-operative, and post-radiation treatment functional outcomes are reported. Results: No postoperative or post-EBRT complications were reported for any of the 17 patients who underwent RASP followed by EBRT during a median follow-up time of 12 months. The median time from RASP to EBRT was 9 months. Median prostate size was 135 g (IQR 110–165). 13 (76.5%) patients received a pre-EBRT rectal spacer. Median IPSS score preoperatively improved at 90 days post-RASP (13.5 vs. 2.5; IQR 10.8–15.2), and this benefit was sustained post-EBRT with a median IPSS at 3 vs. 12 months (4 vs. 0; IQR 0–5). There was no statistically significant difference between postoperative IPSS and post-EBRT IPSS at 3 (p = 0.677) or 12 (p = 0.627) months. In all 14 patients with localized disease and PSA data, none had recurrence during the study period. Conclusions: A subset of patients with clinically significant prostate cancer have marked prostatomegaly and LUTS. We report an alternative treatment approach for patients unwilling to undergo radical prostatectomy. We found robotic simple prostatectomy followed by definitive radiation to be feasible and safe.Keywords

The presence of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) in men diagnosed with clinically significant PCa can influence the choice of treatment. In the case of significant obstructive LUTS, physicians and patients may choose to pursue radical prostatectomy (RP) over external beam radiation therapy (EBRT), given the risk of urinary retention and worsening of LUTS associated with EBRT.1 However, RP also can present technical challenges in those with marked prostatomegaly. Recent studies have shown that RP in men with >100 gm glands carries a higher risk of surgical complications and adverse events,2,3 including worse stress urinary incontinence (SUI) and erectile dysfunction (ED) 4–6.

Significant prostatomegaly and LUTS in combination with clinically significant PCa thus presents a challenging treatment dilemma. Efforts to improve obstructive uropathy prior to EBRT have included various outlet procedures.7 For patients with significant prostatomegaly (>80 cc), American Urological Association (AUA) guidelines recommend laser enucleation or simple prostatectomy 8 but do not provide guidance in the setting of simultaneous prostate cancer. As compared to RP, robot-assisted simple prostatectomy (RASP) carries a much lower risk of SUI and ED due to the differences in the anatomic approach.9,10

Thus, we examined whether an intentional pathway of RASP followed by EBRT for patients with clinically significant prostate cancer in the setting of significant prostatomegaly and obstructive LUTS would be safe and yield favorable post-treatment functional outcomes and quality of life.

A retrospective study was performed of 17 patients who underwent RASP with clinically significant prostate cancer at two institutions between the years of 2015–2023. Twelve of the seventeen patients had biopsy-proven prostate cancer at the time of RASP. The study design was approved by the Institutional Review Board at each institution (Duke IRB# Pro00113563; UTSW IRB# STU-2021-0987).

International Prostate Symptom Scores (IPSS) were obtained, as was erectile function (by the international index of erectile function-5 (IIEF-5)), post-void residual (PVR) as measured by suprapubic ultrasonography, and urine flow rate by uroflowmetry. Patients were excluded if they had prior definitive treatment for prostate cancer or were placed on an active surveillance protocol for their prostate cancer after a shared decision-making conversation. A subset of patients were placed on a course of neoadjuvant androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) prior to undergoing RASP at the discretion of their urologic and medical oncologists based on their risk. Prostate volume was measured by computed tomography (CT), transrectal ultrasound (TRUS), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). A history of acute urinary retention or need for indwelling or intermittent catheter was noted, as were any prior bladder outlet procedures. Patients taking a 5-alpha reductase inhibitor (5-ARI) had their prostate-specific antigen (PSA) value corrected in data analysis according to previously established standards.11

Indications for RASP included markedly enlarged prostate gland (>80 g) and need for catheterization, acute urinary retention, refractory gross hematuria, or refractory lower urinary symptoms. The technique for RASP was standardized in all cases and followed a series of reproducible steps, starting with a transverse incision at the bladder dome, enucleation of the adenoma using a standard technique, followed by a partial re-trigonalization of posterior bladder mucosa to improve hemostasis and facilitate catheter placement. Prostatic tissue was obtained from all procedures and sent for pathologic analysis.

Radiotherapy was delivered using megavoltage photons and standard linear accelerators with cone-beam CT imaging verification, aligning to intra-prostatic fiducials, or with MR-guided imaging verification on an MRlinac platform (Unity, Elekta, Stockholm, Sweden). Rectal spacer products were used at the treating physician’s discretion. Moderately hypofractionated radiotherapy prescriptions of 60 Gy in 20 fractions and IMRT planning were used. Infrequently, dominant intra-prostatic lesion boosts were used to 67 Gy in 20 fractions, with care to constrain organs at risk including the urethra/RASP defect to <67 Gy maximum point dose. Otherwise, constraints typically followed those of the published Prostate Fractionated Irradiation Trial (PROFIT) regimen or of the National Radiation Therapy Group (NRG) consensus planning goals for moderately hypofractionated radiation therapy when treating prostate only vs. prostate and pelvic nodes, respectively. Clinical treatment volume (CTV) typically included prostate and proximal seminal vesicles and intra-prostatic RASP defect with a 5 mm margin to planning treatment volume; elective treatment of distal seminal vesicles and pelvic nodes with similar margin was used in high-risk disease at investigator’s discretion. Planning was based on post-RASP simulation imaging. While no comparison plan was made based on pre-RASP imaging for this study, treatment volume related to residual gland size after RASP was typically much reduced.

Continuous variables were analyzed using mean and standard deviation (SD). Categorical variables were grouped using counts and percentages. Mann-Whitney U test was used to analyze non-normally distributed variables. Data analysis was performed using Prism-GraphPad, version 9.5.0 (GraphPad Software, Boston, MA, USA) with a significance level of p < 0.05.

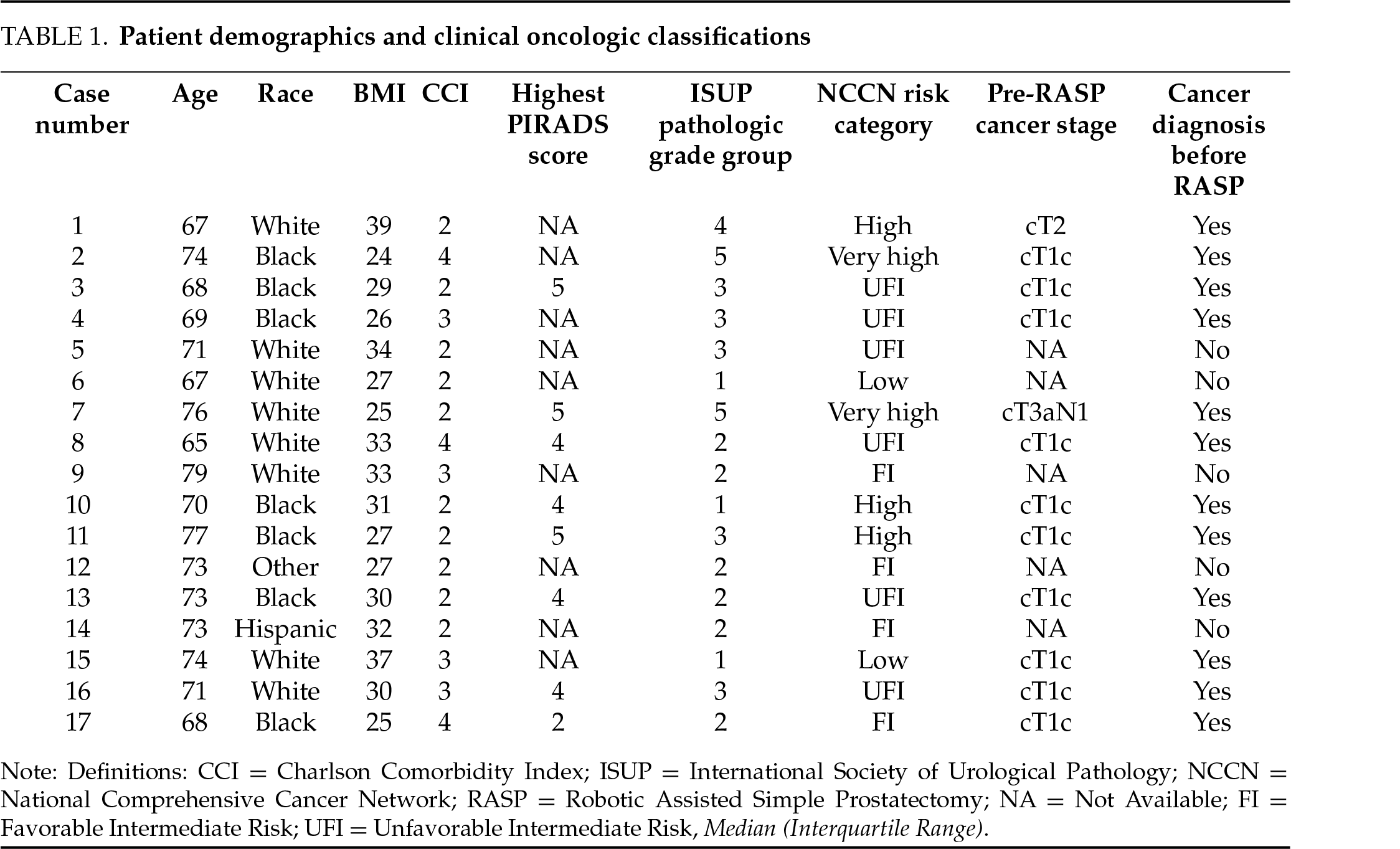

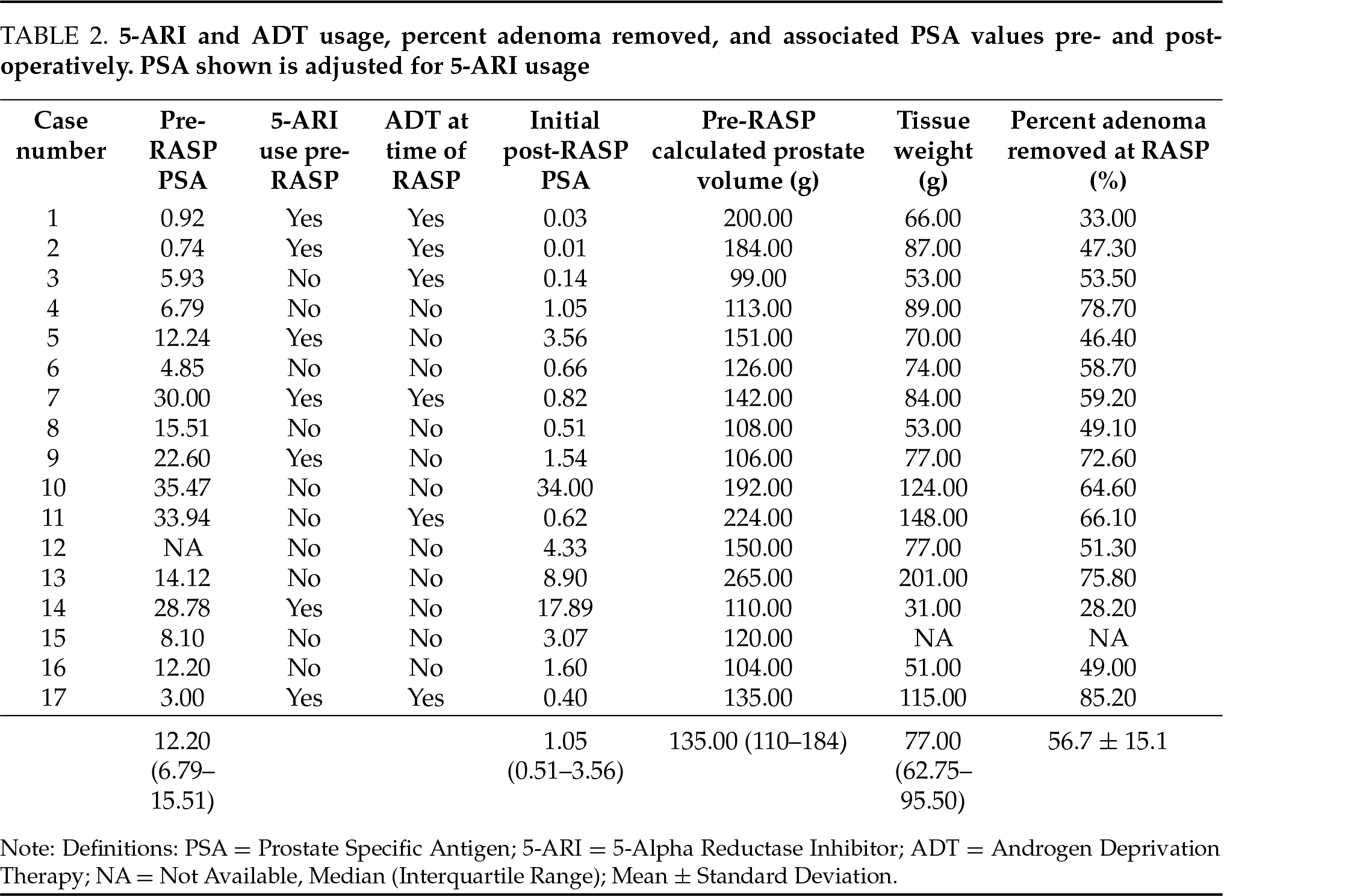

A total of 17 patients underwent simple prostatectomy during the study period. The median age for the 17 patients was 71.47 ± 3.89 years with an average body mass index of 30.0 ± 4.52. Twelve (70.6%) patients had biopsy-proven prostate cancer preoperatively: 10 (58.8%) were preoperative stage cT1c, 1 (5.9%) cT2, and 1 (5.9%) cT3aN1. The remaining 5 were diagnosed with prostate cancer found incidentally in the specimen from RASP. The median prostate size was 135 g (interquartile range (IQR) 110–165). NCCN risk classifications for all patients are included in Table 1. The median operative time was 149 min (IQR 122–193) and the average blood loss was 252 ± 288.6 cc. The mean percentage of removed adenoma was 56.7% +/−SD 15.1% (Table 2). Median LOS was 1 ± 0.41 days. There were no Clavien-Dindo grade II or greater complications. The median catheter duration following surgery was 6 days (IQR 4–7). Sixteen of seventeen patients reported no stress urinary incontinence. One patient reported minor stress urinary incontinence at his first postoperative visit, which was resolved by his 6-week post-operative visit.

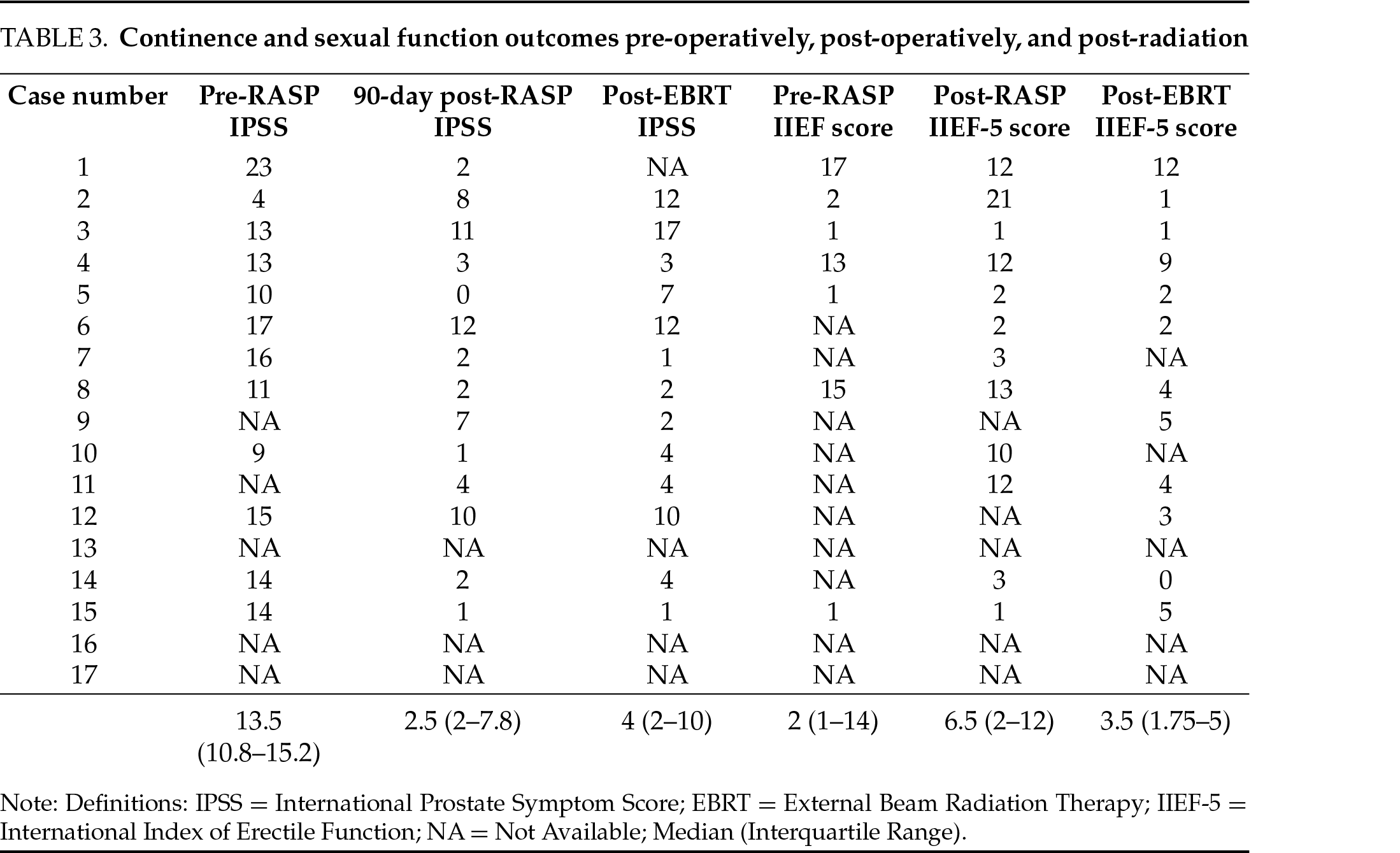

Six of the 17 patients were placed on a short course of neoadjuvant ADT based on their risk category. After a minimum of 3 months following RASP, all patients underwent definitive radiation therapy. 13 (76.5%) patients received pre-radiation rectal spacer placement, in the weeks prior to radiation initiation. No complications were observed after rectal spacer placement. The median preoperative IPSS of 13.5 (IQR 9–15) was reduced 90 days after RASP to a median of 2.5 (IQR 10.8–15.2, p = 0.019). Following radiation, the median IPSS score was 4 (IQR 2–7) at 3 months and 0 (IQR 0–5) at 12 months post-radiation. Compared to preoperative IPSS, post-radiation scores were significantly improved at 3 (p = 0.002) and 12 (p = 0.001) months (Table 3). There was no statistically significant difference between postoperative IPSS and post-EBRT IPSS at 3 (p = 0.677) or 12 (p = 0.627) months. In 14 patients with PSA data, none met the definition of biochemical recurrence during the study period.

Prostatic enlargement is nearly ubiquitous in aging males.12,13 It is estimated that prostate size increases approximately 3% annually, with 80% of males experiencing enlargement in the 9th decade of life.13,14 It is a reasonable assumption due to an increasingly aging population that it will not be uncommon to diagnose clinically significant PCa in the setting of marked prostatomegaly. It is therefore necessary to further evaluate clinical pathways that may optimize treatment in this subset of the population.

Recently published data demonstrates that radical prostatectomy in patients with significant prostatomegaly poses additional risks compared to patients without prostate enlargement.15 Jaber et al. reported on a large cohort of over 14,000 patients who underwent robotic radical prostatectomy, with patients stratified by prostate size into four cohorts, and each cohort was compared by oncologic and functional outcomes.2 Patients with larger prostates had lower rates of nerve sparing, worse rates of stress incontinence, and worse recovery of sexual function compared to smaller prostates.

Results such as these are especially of concern in men over the age of 70, who are already at heightened risk for stress urinary incontinence post operatively.16 Bolat et al. reported on a cohort of over 8200 patients who underwent radical prostatectomy comparing functional outcomes by patient age at surgery.17 1-year continence rates were higher in younger patients (93% in the <65 vs. 86% ≥75 years) and potency rates were worse in the older patients (59% in the <65 vs. 31% ≥ 75 years).

Furthermore, the risk of urinary functional decline after radiation therapy is well documented in patients with baseline LUTS,18 and thus consideration of a bladder outlet procedure prior to radiation is frequently considered. Recommended bladder outlet procedures for glands >80 g are RASP and laser enucleation,8 however, a recent large meta-analysis of endoscopic enucleation procedures reports postoperative incontinence rates ranging from 8–18%.19 Conversely, RASP has been shown to improve LUTS attributed to prostatomegaly while minimizing the risk of stress incontinence and other functional side effects.20,21 As a result, RASP may be slightly preferred in this clinical situation for patients with clinically significant prostate cancer and significant prostatomegaly considering radiation.

Improvement in functional outcomes (significant decrease in IPSS scores and corresponding improved voiding parameters) are well established following RASP and likely optimize a patient’s candidacy for radiation therapy. While these observed improvements in IPSS and quality of life are not novel, this is the first study demonstrating that these benefits are sustained even following radiation therapy up to 12 months post-treatment. We also demonstrate the safety of this novel pathway with no Clavien II or greater adverse events following either treatment. Lastly, early in the experience, no patients with PSA data experienced a biochemical recurrence after combination therapy of RASP followed by EBRT.

The median follow-up time of 12 months for our study was too short to report meaningful oncologic outcomes for prostate cancer. Future studies including longer follow-up would be beneficial to understand the oncologic merit of the pathway proposed here. Similarly, side effects from radiation therapy will need to be monitored longitudinally. The inclusion of six patients that had received neoadjuvant ADT may impact our results by suppressing PSA, however the decision to administer ADT was consistent with established medical and radiation oncologist protocols and is reflective of standard practice. Conversely, patients with advanced clinical-stage cancers in our study that were not eligible to receive neoadjuvant ADT may be at additional oncologic risk from a slight delay in definitive treatment. However, radical prostatectomy series report positive surgical margin rates as high as 60% for patients with cT3 disease, with 5-year biochemical free survival rates ranging from 45–62%;22 many of these men will face radiation regardless and with an arguably worse quality of life if their bladder outlet obstruction is not optimized. It remains unclear in high-risk patients to what extent forgoing radical treatment combined with later radiation therapy +/− androgen deprivation (aka multi-modal approach) may affect biochemical recurrence, metastasis and survival rates. Beyond the AUA guideline recommendation to consider RASP for glands >80 g, the ideal prostate size to consider this pathway remains unclear 23, though the median prostate size was >130 g in this cohort.

While the pathway of RASP followed by EBRT was found to be both feasible and safe, we recognize there are several limitations to this study. First, it is limited by the retrospective design and small study numbers. The authors also recognize that there is controversy in the literature to the degree in which prostate size affects the outcome of radical surgery 15, although recent data supports this supposition. Also, the radiation regimen used was predominantly moderately hypofractionated, and it is not clear whether treatment with more ultra-hypofractionated regimens can be used after RASP based on this data. Moreover, while the reduced treatment target volume was noted as a function of a significantly reduced gland size after RASP, we did not actually have available simulation and planning data as a pre-RASP comparison.

Our study has a median age of nearly 72 years, and in this age group, most urologists agree with approaching radical prostatectomy with caution. An individualized, shared decision-making conversation inclusive of patient goals, co-morbidities, and life expectancy is necessary.24 We believe this pathway may fit into that discussion.

In the subset of patients with very large prostates and clinically significant prostate cancer, robotic simple prostatectomy followed by definitive radiation therapy is shown to be a safe and feasible treatment pathway for patients unwilling to undergo definitive radical prostatectomy. Future studies are needed to monitor longer-term effects of radiation as well as oncologic outcomes.

Acknowledgement

Not applicable.

Funding Statement

The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization: Tara Morgan, Jeffrey Gahan; methodology: Tara Morgan, Jeffrey Gahan, Neil B. Desai; validation: Tara Morgan; formal analysis: Joshua Kim, Brian Calio; investigation: Tara Morgan, Jeffrey Gahan, Daniel Segal; resources: Tara Morgan; data curation: Tara Morgan, Brian Calio; writing—original draft preparation: Brian Calio; writing—review and editing: Brian Calio, Tara Morgan; visualization: Brian Calio, Joshua Kim, Sarah Attia, Rafael Tua Caraccia, Tara Morgan; supervision: Tara Morgan, Jeffrey Gahan; project administration: Tara Morgan; funding acquisition: The authors received no specific funding for this study. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Author, TNM, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval

This study was approved by an IRB board at Duke University and University of Texas Southwestern University (Duke IRB# Pro00113563; UTSW IRB# STU-2021-0987).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Kwon WA, Lee SY, Jeong TY, Moon HS. Lower urinary tract symptoms in prostate cancer patients treated with radiation therapy: past and present. Int Neurourol J 2021;25(2):119–127. doi:10.5213/inj.2040202.101. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Jaber AR, Moschovas MC, Saikali S et al. Impact of prostate size on the functional and oncological outcomes of robot-assisted radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol Focus 2024;10(2):263–270. doi:10.1016/j.euf.2024.01.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Olsson CA, Lavery HJ, Sebrow D et al. Does size matter? The significance of prostate size on pathologic and functional outcomes in patients undergoing robotic prostatectomy. Arab J Urol 2011;9(3):159–164. doi:10.1016/j.aju.2011.10.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Meraj S, Nagler HM, Homel P, Shasha D, Wagner JR. Radical prostatectomy: size of the prostate gland and its relationship with acute perioperative complications. Can J Urol 2003;10(1):1743–1748. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

5. Boczko J, Erturk E, Golijanin D, Madeb R, Patel H, Joseph JV. Impact of prostate size in robot-assisted radical prostatectomy. J Endourol 2007;21(2):184–188. doi:10.1089/end.2006.0163. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Huang AC, Kowalczyk KJ, Hevelone ND et al. The impact of prostate size, median lobe, and prior benign prostatic hyperplasia intervention on robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy: technique and outcomes. Eur Urol 2011;59(4):595–603. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2018.06.015. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Mazur AW, Thompson IM. Efficacy and morbidity of channel TURP. Urology 1991;38(6):526–528. doi:10.1016/0090-4295(91)80170-c. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Sandhu JS, Bixler BR, Dahm P et al. Management of lower urinary tract symptoms attributed to benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPHaUA guideline amendment 2023. J Urol 2024;211(1):11–19. doi:10.1097/ju.0000000000001558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Dommer L, Birzele JA, Ahmadi K, Rampa M, Stekhoven DJ, Strebel RT. Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) before and after robotic-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy: does improvement of LUTS mitigate worsened incontinence after robotic prostatectomy? Transl Androl Urol 2019;8(4):320–328. doi:10.21037/tau.2019.06.24. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Lee Z, Lee M, Keehn AY, Asghar AM, Strauss DM, Eun DD. Intermediate-term urinary function and complication outcomes after robot-assisted simple prostatectomy. Urology 2020;141:89–94. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2020.04.055. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Andriole GL, Guess HA, Epstein JI et al. Treatment with finasteride preserves usefulness of prostate-specific antigen in the detection of prostate cancer: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. PLESS Study Group. Proscar Long-term Efficacy and Safety Study. Urology 1998;52(2):195–201; discussion 201-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

12. Gold SA, Goueli R, Mostardeiro TR et al. Optimal prostate cancer diagnostic pathways for men with prostatomegaly in the MRI era. Urology 2023;179:95–100. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2023.05.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Berry SJ, Coffey DS, Walsh PC, Ewing LL. The development of human benign prostatic hyperplasia with age. J Urol 1984;132(3):474–479. doi:10.1016/s0022-5347(17)49698-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Loeb S, Kettermann A, Carter HB, Ferrucci L, Metter EJ, Walsh PC. Prostate volume changes over time: results from the baltimore longitudinal study of aging. J Urol 2009;182(4):1458–1462. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2009.06.047. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Fahmy O, Alhakamy NA, Ahmed OAA, Khairul-Asri MG. Impact of prostate size on the outcomes of radical prostatectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancers 2021;13(23):6130. doi:10.3390/cancers13236130. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Bolat D, Gunlusoy B. The effect of age on functional outcomes after radical prostatectomy. Urol Oncol 2015;33(7):333. doi:10.1016/j.urolonc.2015.04.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Mandel P, Graefen M, Michl U, Huland H, Tilki D. The effect of age on functional outcomes after radical prostatectomy. Urol Oncol 2015;33(5):203.e11–203.e18. doi:10.1016/j.urolonc.2015.01.015. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. van Tol-Geerdink JJ, Leer JW, van Oort IM et al. Quality of life after prostate cancer treatments in patients comparable at baseline. Br J Cancer 2013;108(9):1784–1789. doi:10.1038/bjc.2013.181. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Pang KH, Ortner G, Yuan Y, Biyani CS, Tokas T. Complications and functional outcomes of endoscopic enucleation of the prostate: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised-controlled studies. Cent Eur J Urol 2022;75(4):357–386. doi:10.1007/s00345-023-04308-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Lee M, Strauss D, Lee Z, Harbin A, Eun DD. Outcomes of robotic simple prostatectomy after prior failed endoscopic treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Endourol 2023;37(5):564–567. doi:10.1089/end.2023.0020. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Shelton TM, Drake C, Vasquez R, Rivera M. Comparison of contemporary surgical outcomes between holmium laser enucleation of the prostate and robotic-assisted simple prostatectomy. Curr Urol Rep 2023;24(5):221–229. doi:10.1007/s11934-023-01146-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Xylinas E, Daché A, Rouprêt M. Is radical prostatectomy a viable therapeutic option in clinically locally advanced (cT3) prostate cancer? BJU Int 2010;106(11):1596–1600. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410x.2010.09630.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Lerner LB, McVary KT, Barry MJ et al. Management of lower urinary tract symptoms attributed to benign prostatic hyperplasia: aUA GUIDELINE PART I-initial work-up and medical management. J Urol 2021;206(4):806–817. doi:10.1097/ju.0000000000002183. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Mandel P, Chandrasekar T, Chun FK, Huland H, Tilki D. Radical prostatectomy in patients aged 75 years or older: review of the literature. Asian J Androl 2017;21(1):32–36. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools