Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Associations between ureteral stent indwelling time, patient characteristics, and stent pain from an international prospective registry

1 Department of Urology, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC V5Z 1M9, Canada

2 Division of Biostatistics, Boston Scientific Corporation, Marlborough, MA 01752, USA

3 Department of Urology, NorthShore University Health System, Glenview, IL 60201, USA

4 Department of Urology, Nagoya City University Hospital, Nagoya-shi, Aichi-ken, 467-8601, Japan

5 Department of Urology, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL 60208, USA

6 Department of Urology, Indiana University Medical Center, IN 46202, USA

7 Department of Urology, New York Presbyterian Hospital, New York, NY 10032, USA

8 Department of Urology, Centre Hospital Prive St Gregoire Vivalto, Saint-Gregoire, 35760, France

9 Department of Urology, University of Kansas Hospital, Kansas City, KS 66160, USA

10 Department of Urology, Penn State Milton S Hershey Medical Center, Hershey, PA 17033, USA

11 Department of Urology, Mayo Clinic Phoenix, Boulevard Phoenix, AZ 85054, USA

* Corresponding Author: Connor M. Forbes. Email:

Canadian Journal of Urology 2025, 32(4), 335-344. https://doi.org/10.32604/cju.2025.063577

Received 18 January 2025; Accepted 30 April 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

Objectives: Previous studies have shown conflicting results concerning the optimal duration of ureteral stenting after endourologic treatment of stone disease, its effect on patient comfort, and the necessity for emergent, unscheduled care. This study assessed the impact of stent duration, sex, and other patient-associated factors on reported pain scores using a large, international prospective registry. Methods: A prospective observational patient registry on ureteral stents from 10 institutions in 4 countries (United States, Canada, France, and Japan) from 2020–2023 was assessed. The primary outcome was Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) pain intensity scores administered on the day of stent removal, before stent removal. Patients were grouped by indwelling time (short, medium, and long), and pain scores were compared. The impact of sex, height vs. stent length, and presence or absence of tether were assessed. Results: 359 patients were enrolled in the database, with outcomes analyzed for 268 patients with a unilateral stent placed after an endourologic procedure for stones. No significant difference was detected in pain scores between the indwelling time groups (p = 0.41). Height for a given stent length was not significantly associated with pain scores. There was no difference in pain scores with or without tether. Men reported lower pain scores than women (p = 0.018). Conclusions: This study did not detect an overall difference in pain scores reported at stent removal within or between stent duration groups. Men reported less pain than women in this study, suggesting that patient factors may be more important than indwelling time when optimizing pain management.Keywords

The optimal duration of stent duration after ureteroscopy for stones is not known, as evidenced by the lack of consensus among practicing endourologists.1 The decision for stent duration is case-dependent, and balances potential benefits such as ureteral healing and postoperative decompression, with potential risks such as patient comfort, infection risk, and need for emergent or unscheduled care.2,3 Most patients experience discomfort both at the time of stent removal and thereafter, likely related to ureteral spasm.4 Given the significant impact of ureteral stents on patient quality of life and emergency care, further clarifying the optimal timing for stent removal would be helpful in improving patient care.

Existing studies using retrospective data for stent duration are inconsistent and focus on the initial week of stenting. Often-cited studies found an increase in emergency department visits for patients with a shorter compared to a longer ureteral stent indwelling time,3 and fewer emergency department visits when stents are removed after a longer indwelling time.5 Longer stent indwelling time has also been associated with decreased symptoms after removal.6 However, in contrast, a small randomized controlled trial found that patients who had a stent in for less than a week after ureteroscopy reported better ureteral stent symptoms and better pain scores than patients who had their stents for a 1-week indwelling time and without a difference in complication rate.7 Furthermore, an excellent prospective study shows that stent symptoms peak at 3 days post-operative, using one of the same measures as the present study (Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Pain Intensity and Pain Interference), but is limited to patients in the United States.8

Since ureteral stents are commonly placed after endourologic procedures for stones with variable indwelling times, a global understanding of whether shorter indwelling time minimizes patient discomfort and complications is needed. In the present study, we leveraged an international, post-market database required for safety monitoring, which includes PROMIS pain intensity and interference scores. The purpose of this study was to assess pain scores for patients in relation to duration of stent placement, as well as sex, demographics, medications, and other risk factors from an international, multi-site, prospective study to increase the power of published literature on stent symptoms, including international patients.

A prospectively populated observational cohort study of endourologic procedures for stones using Boston Scientific ureteral stents was established in a registry designed to support device registration in the European Union (clinicaltrials.gov NCT04197583). This was an international registry including 10 centres in 4 countries (United States, Canada, France, and Japan). The registry had prospective data input from February 2020 to February 2023, with Institutional Review Board/Independent Ethics Committee approval at each site. Trained research personnel filled out standardized data collection sheets as part of the prospective registry. For the patient-reported outcomes, trained research personnel provided the patients with standardized questions as part of the prospective registry. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects when they were enrolled, available in supplementary files.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

This registry included patients who underwent placement of any Boston Scientific ureteral stents during endourologic procedures for stone disease. Only those patients who underwent unilateral, single stent placement at the time of endourologic procedure for stone disease were included in the current analysis. Procedures included ureteroscopy with laser lithotripsy or basket extraction, or stent placement alone for stone disease. Patients who had bilateral stent placement, tandem stent placement, or stent placement for other reasons, such as malignant ureteral obstruction or stricture, were excluded from this study. The decision for stent placement and duration of the stent was made by each treating surgeon as part of the usual standard of care. All stents were double-loop stents. The method of removal (dangle string or cystoscopy) was left to the discretion of the surgeon.

Data collection and measurement

Baseline patient demographics, including age, sex, height, and weight, were collected, along with the endourologic procedure type, stent indwelling duration, presence/absence of a tether, and complications associated with stent placement and removal. The validated PROMIS Pain Intensity and Pain Interference scores, reflecting the pain experienced over the past week, were collected at three time points: before the urologic procedure that required stent placement (just before the procedure), on the day of stent removal (just before removal), and 3–12 weeks following stent removal. The forms were administered in the clinic or via telephone. The instruments used were the PROMIS Adult Short Form v1.0—Pain Intensity 3a and the PROMIS Adult Short Form v1.0—Pain Interference 6b. The Pain Intensity form 3a includes the following three questions: “In the past 7 days…, how intense was your pain at its worst?”, “How intense was your average pain?”, and “What is your level of pain right now?”. The Pain Interference form 6b asks patients to rate how much pain interfered with their life in the following six ways: their “enjoyment of life”, “ability to concentrate”, “day-to-day activities”, “enjoyment of recreational activities”, “ability to perform tasks away from home”, and “frequency of avoiding socializing with others” in the past 7 days. The raw scores are converted to a “T-score”, which is standardized to the US general population, with a mean of 50 and a standard deviation (SD) of 10, where a higher score represents a greater level of pain.

The duration of stent indwelling time was assessed to pain scores as a continuous variable, as well as by categorizing the stent indwelling time into three groups: short (0–7 days), medium (8–15 days), and long (≥16 days), based on expert consensus. This approach takes into account that the PROMIS questionnaire asks about pain over the preceding 7 days. The primary outcome was the PROMIS pain intensity score in the week before stent removal. A PROMIS intensity score change of 2 to 6 points can be considered clinically significant.9 Additional outcomes included differences in pain interference scores and pain score variations within groups. Demographic factors, medications prescribed at baseline (including alpha-blockers, antibiotics, and pain relievers), and the presence or absence of a tether were assessed for their association with pain scores. To evaluate the relationship between pain intensity and stent length vs. patient height, patients were stratified by stent length, and the associations of height with pain score were analyzed.

Univariate and multivariable analysis was performed to evaluate relationships between stent indwelling time, demographic factors, and pain scores. Multivariable analysis was performed for the stent duration group in addition to variables with p < 0.05 on univariate analysis, and a p-value < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. Besides, sensitivity analyses were performed, adding an adjustment for country/geographic region, and medication to the model. All statistical analyses were performed with the use of the Statistical Analysis System (SAS v9.4).

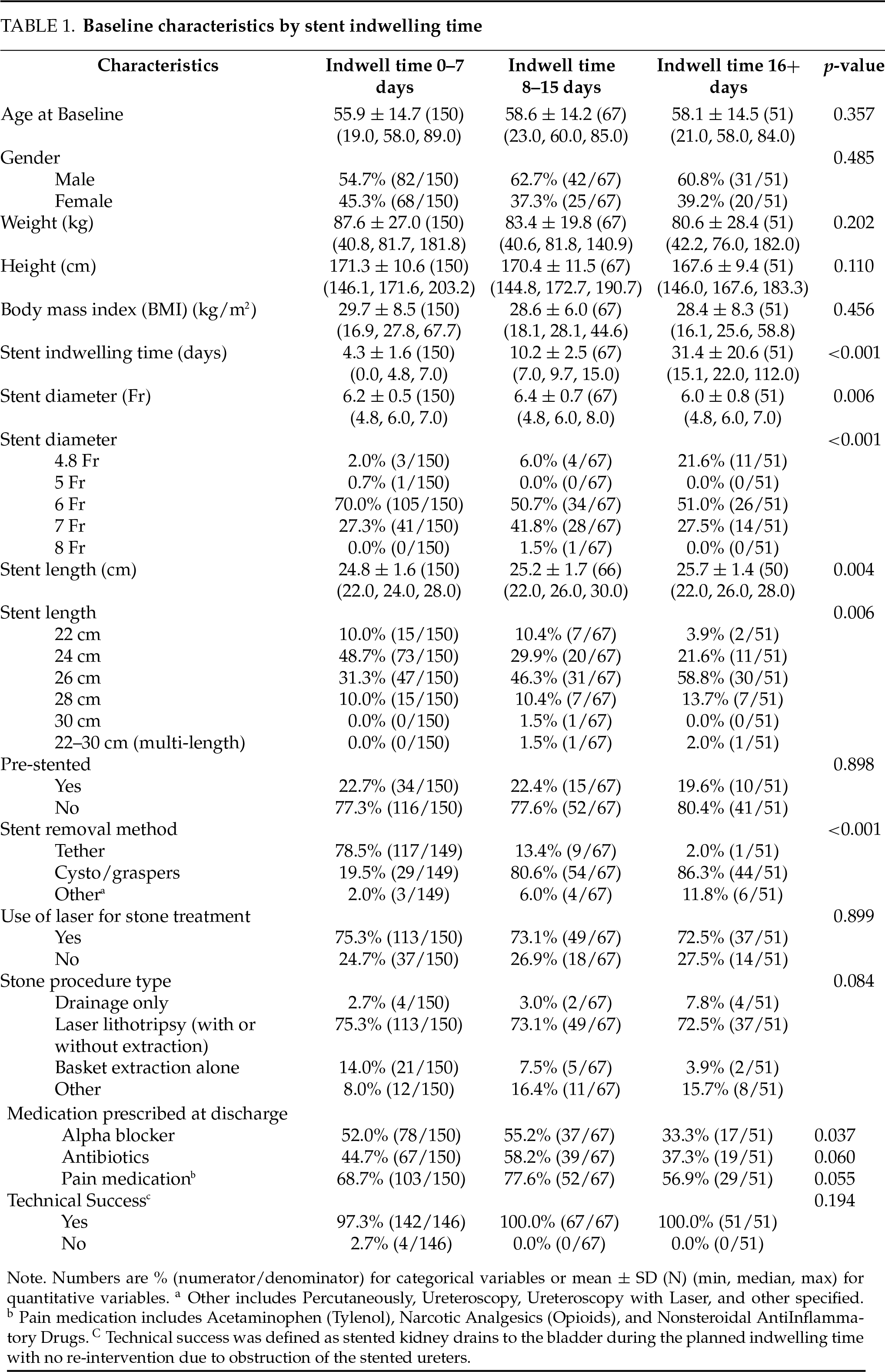

Between February 2020 and February 2023, there were 359 patients enrolled in the registry. Of these, 271 had a single, unilateral stent placed after an endourologic procedure for the treatment of stone disease, and 268 patients had the date of stent removal available and were therefore included in the primary analysis. These included patients from the USA (n = 188), Canada (n = 39), France (n = 25), and Japan (n = 19). As shown in Table 1, there were 150 patients in the short (0–7 days) stent group, 67 patients in the medium (8–15 days) stent group, and 51 patients in the long (16+ days) stent group. Patient demographics, including age, sex, height, and body mass index (BMI), can be seen in Table 1. Most patients had a stent placed at the time of laser lithotripsy or basket extraction of the stone, with a minority having only stent placement without treatment of the stone. Most (78.5%) of patients in the short indwelling time group had their stents removed via a retrieval line (tether), while most (>80%) of the patients in the longer indwelling groups did not have a tether and underwent cystoscopy for removal. Stents ranged from 22–30 cm or multi-length in length, and 4.8–8 Fr in diameter (Table 1). 59 patients were pre-stented, with no difference in pain scores at stent removal between the pre-stented and non-presented groups (p = 0.93).

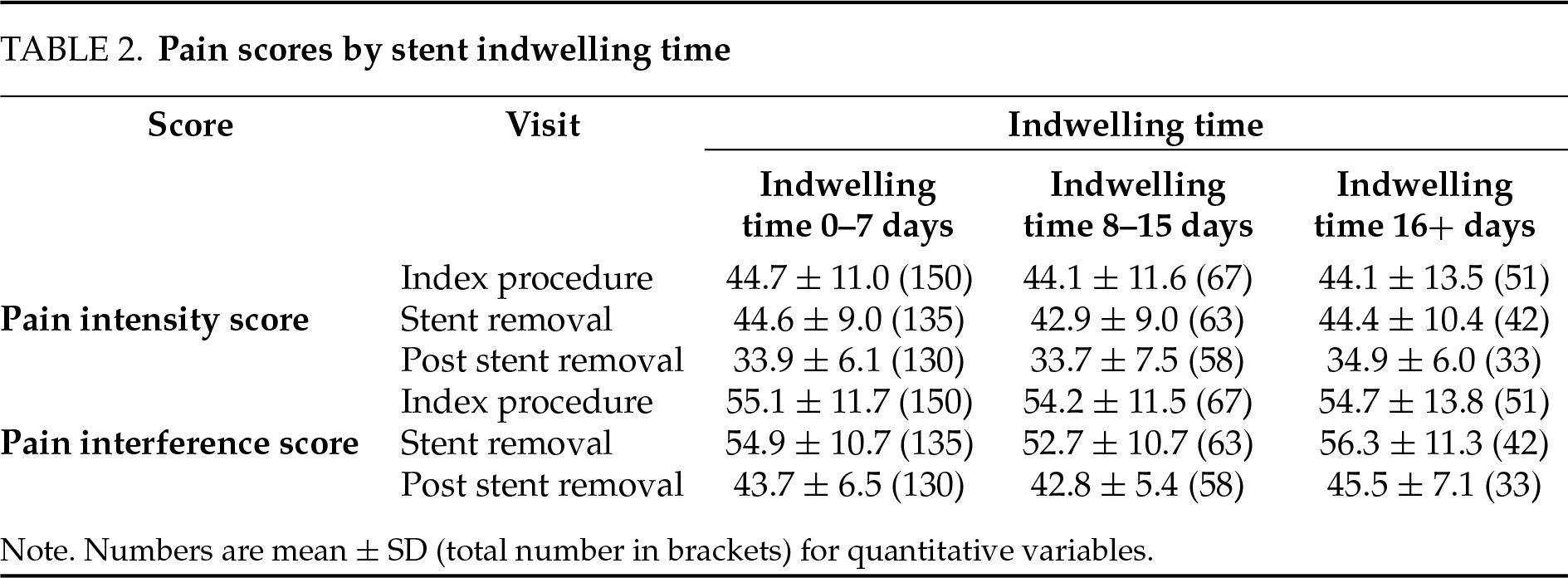

Pain scores at baseline prior to the index procedure, in the week prior to the stent removal and at the post-stent removal visits were similar between the three stent indwelling time groups (0–7, 8–15, 16+ days), as were pain interference scores (Table 2).

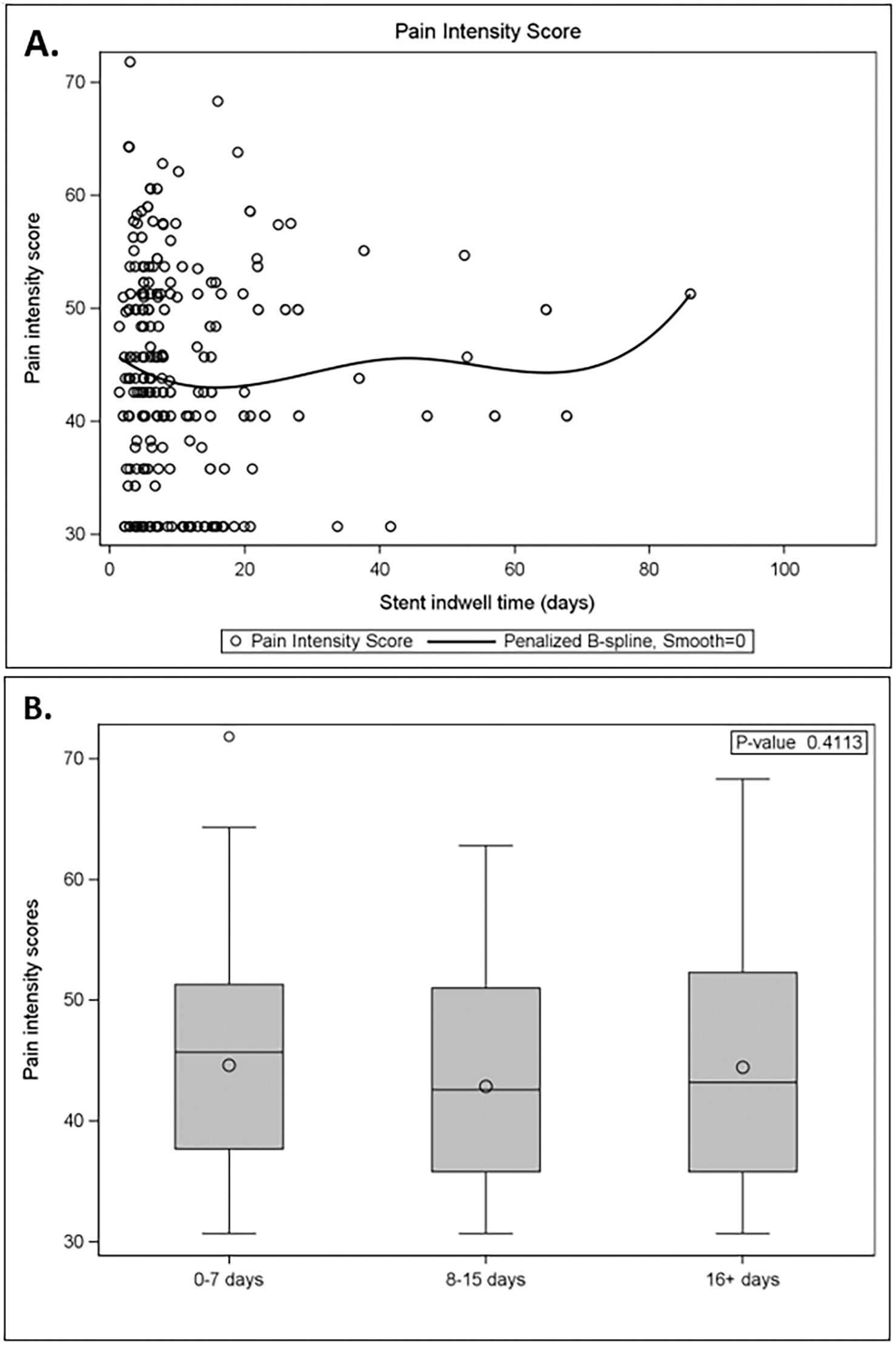

PROMIS pain intensity scores administered on the day of stent removal (prior to removal) did not show a relationship with stent indwelling time (Figure 1A). There were no statistically significant differences in pain scores between patients grouped by indwelling time (Figure 1B, p = 0.41). Within these indwelling time groups, no statistically significant difference in pain scores was observed for indwelling times or stent removal (p-value range 0.25–0.50).

Figure 1: Patient pain intensity scores by stent indwelling time. (A) Pain intensity scores in the week prior to stent removal by stent indwell time (days). (B) Pain scores were not statistically significant between groups (0–7 days: n = 150; 8–15 days: n = 67; 16+ days: n = 51)

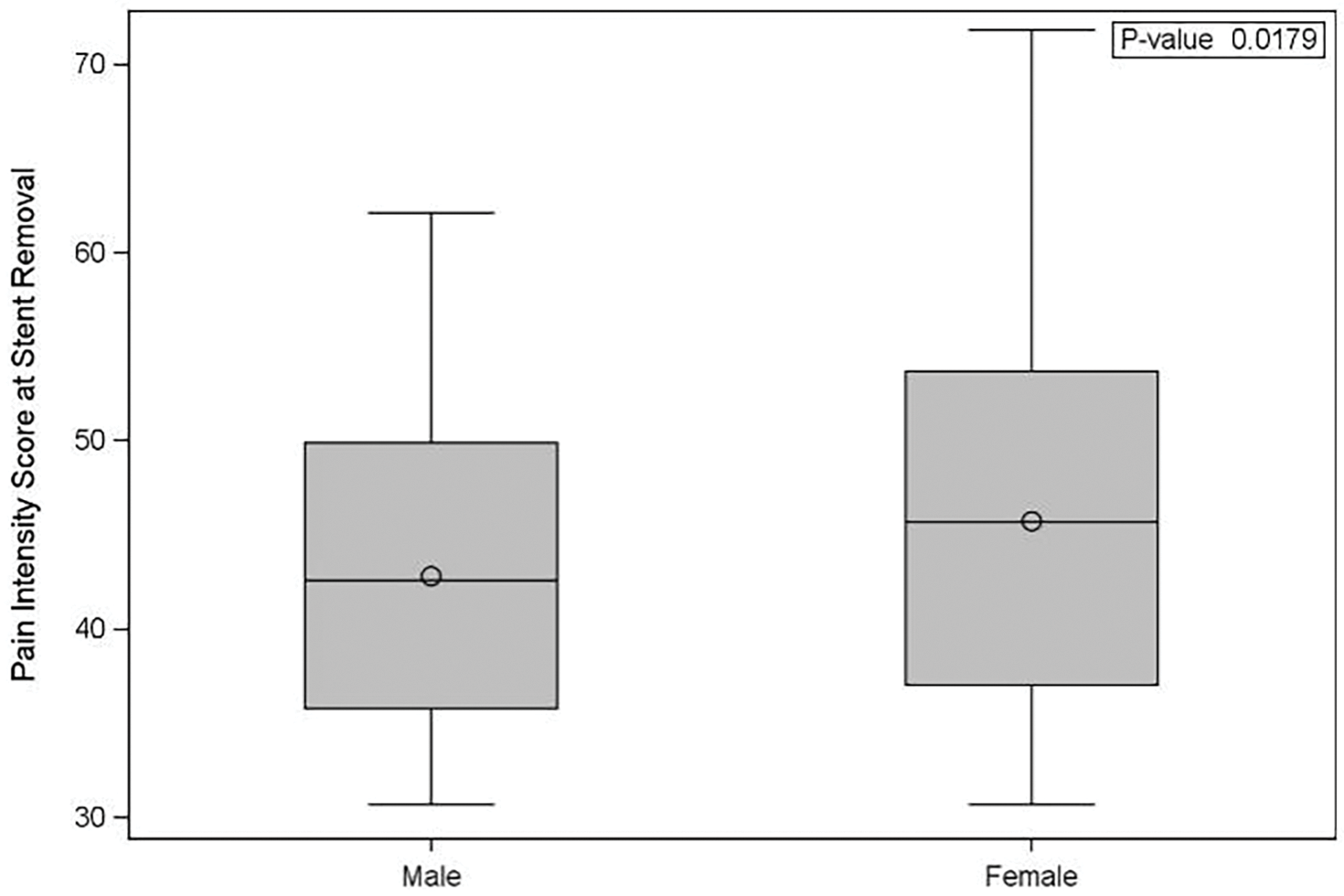

Demographic factors were assessed by univariate analyses for association with pain scores. Men reported lower pain scores than women, on average 42.8 vs. 45.7 (Figure 2, p = 0.018). For a given stent length, differences in height, including extremes of height, were not found to be associated with differences in pain scores for each stent length (22 cm: p = 0.14; 24 cm: p = 0.80; 26 cm: p = 0.75; 28 cm: p = 0.73). Medications prescribed at baseline were not significantly associated with pain intensity (p-value range 0.094–0.88), including alpha blockers (with the lowest p-value), as well as acetaminophen, antibiotics, anticholinergics, narcotic analgesics, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, phenazopyridine, other, or none.

Figure 2: Patient pain intensity scores by sex. Pain intensity scores in the week prior to stent removal. Men reported significantly lower pain intensity compared to women (p = 0.018)

Finally, the presence or absence of tether on the stent was evaluated for association with pain scores. The score was administered before stent removal. There was no statistically significant association identified in the presence or absence of tether and pain scores (p = 0.65).

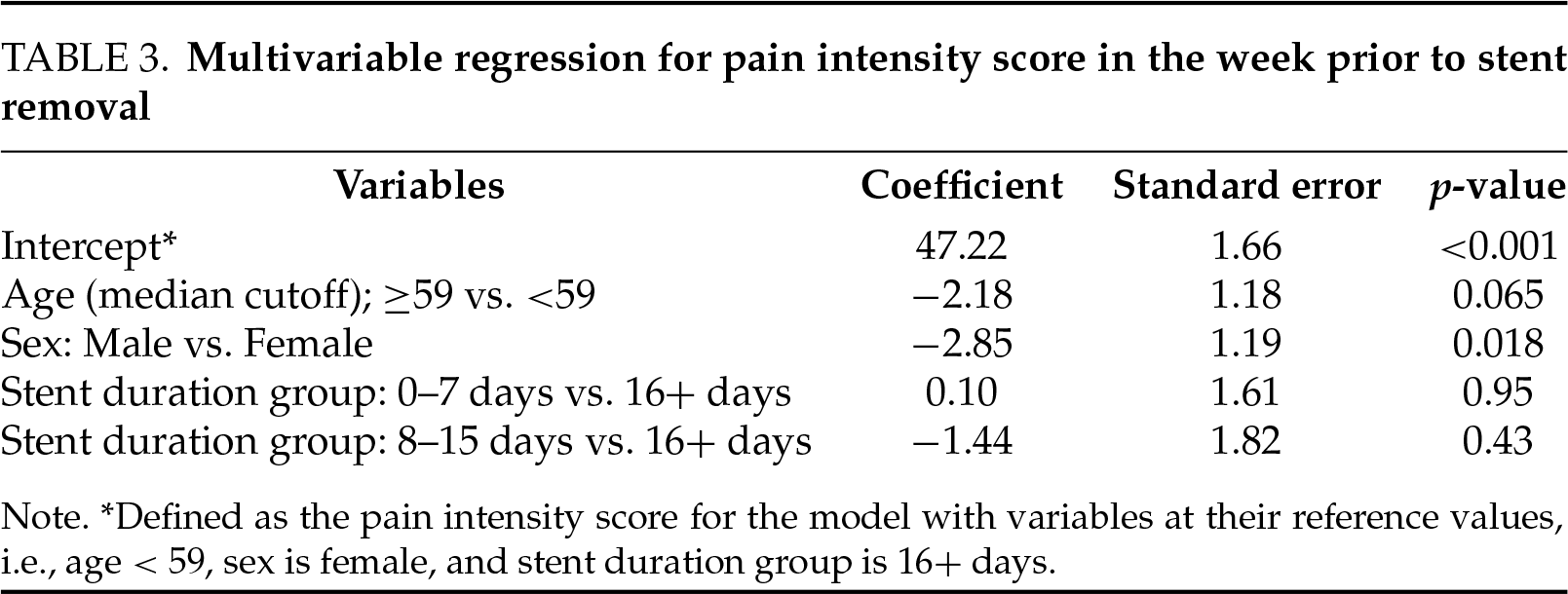

A multivariable regression analysis was performed and can be seen in Table 3. This showed that stent duration was not associated with pain intensity scores after adjustment for age and sex. Only male sex remained significantly predictive of reduced pain intensity scores (PROMIS pain score −2.84 (±1.2) compared to females, p = 0.018). The association with lower pain intensity in males was robust to sensitivity analysis, adding adjustment for country/geographic region to the model (PROMIS pain score −2.55 compared to females, p = 0.037).

In this study, patients reported similar degrees of pain based on scores on questionnaires administered at the time of stent removal (before removal), regardless of indwelling time, patient height/stent length, or presence or absence of tether. Men experienced less pain than women in the days before stent removal.

In our study, we assessed PROMIS pain scores for patients with short, medium, or long stent indwelling times (0–7, 8–15, 16+ days). Interestingly, the pain scores were not significantly associated with stent indwelling time. This indicates that in the present study, the intensity of stent pain does not differ on a day-by-day basis for short, medium, or long stent indwell times. However, patients with a longer total stent duration would be expected to experience a larger accumulated number of days of discomfort or a larger “area under the curve” of total stent-associated pain. Furthermore, our study found there was no difference within the short stent group of 0 to 7 days of indwelling time for pain on the day of stent removal. Together, these findings show clinicians what to expect when choosing to leave a stent in for a longer period: an extra duration of stent-associated discomfort, however, without increasing or decreasing intensity. This information can be used as part of decision-making for stent duration, favoring a shorter possible duration of stenting, when possible, with the caveat that the existing body of literature suggests that very short stent indwell times can increase pain after removal.

Duration of stenting and post-procedural symptoms

Patient symptoms with ureteral stenting are a major cause of morbidity and reduced quality of life. Pathophysiologic changes over the course of several days contribute to these symptoms.10 After 48 h of stenting, the ureter becomes dilated and shows upregulation of molecular pathways that are associated with obstruction, kidney injury, and fibrosis.11 Spasm of the ureter is also observed secondary to ureteral stent placement.11 In addition to advances in stent materials technology,12,13 a sometimes modifiable factor is the duration of stent placement. Because of the complex timing of pathologic changes in the ureter, the obvious decision to remove the stent earlier may be counterproductive if it occurs at a time point when the ureter is highly spasmodic. These spasms can result in obstruction post-stent removal, resulting in increased pain, hydronephrosis on imaging, and in some cases a necessary return to the operating room for reinsertion of the stent. The present study aims to understand temporal patterns of pain associated with stent indwelling time to better identify the optimal timing of stent removal.

Previous studies have been conflicting in terms of patient experience for different stent durations. In one study, unanticipated care requirements were greater for patients with a shorter stent duration.3 In that study, patients who were randomized to a 3-day stent indwelling time after ureteroscopy had a much higher rate of post-procedural events in the 3 days after stent removal compared to patients randomized to a 7-day stent indwelling time (23% vs. 3%, p = 0.026), defined as telephone call, clinic or Emergency Department visit.3 Similarly, patients with a stent duration of 7 days or less were found in a separate study to have more pain after stent removal than patients with a longer than 7-day indwelling time.2 A large database study found an increased occurrence of Emergency Department visits for patients who had their stents removed on or before day 4 compared to a longer indwelling time.5 This may be explained by ureteral spasm and dysregulation of ureteral peristalsis that occurs acutely but then resolves after a certain amount of time. Furthermore, ureteral inflammation was found to increase over and peak at 72 h post-stent placement, while gradually decreasing and leveling out on day 7 at levels that were still higher than on day 0. This provides a potential explanation for pain felt if the stents were pulled before that resolution of inflammation as outlined in the above studies.14 However, leaving stents in for longer periods increases the total amount of time that patients experience the symptoms of an indwelling stent. Previous mechanistic research suggests that ureteral stents provoke an initial period of increased peristalsis, followed by decreased peristalsis.15,16 One possible explanation for the previous findings of adverse events with shorter stent indwelling time is that stent removal at the time of increased peristalsis results in increased post-removal stent events, such that waiting longer will be better tolerated by patients. For patients with extremely long stent durations for ureteral obstruction from non-stone causes, ureteral stent symptoms and quality of life are known to improve after 9 months.17

While long stent indwelling time can raise concerns for encrustation and infection, our study does not suggest that they will experience greater pain at the time of stent removal. While statistical significance is important for outcome metrics, what constitutes a clinically meaningful difference informs whether outcomes will affect practice. While no uniform threshold exists for all situations, PROMIS intensity score changes between 2 and 6 can be considered clinically significant.9

Demographic factors affecting symptoms on date of stent removal

In the present study, men reported overall lower PROMIS pain scores than women. This contrasts with some previous research, in which the male sex and younger age were associated with increased stent-associated symptoms.18,19 However, similar to ours, in other studies, women were found to have greater pain with stents or after stent removal.2,20 Our study supported this finding, with lower pain scores reported by men before stent removal, after adjusting for age and stent duration group (p = 0.028). Sensitivity analysis including country did not affect the relationship between sex and pain scores.

Much previous research has focused on optimal stent length and its impact on pain-associated symptoms. The crossing of the distal stent coil past the midline is thought to be a key contributor to worsened stent-associated symptoms.21 As this midline loop crossing is a factor of stent length, previous studies have assessed for associations between stent length, height (as a surrogate marker of ureteral length), and stent-associated symptoms. Longer stent lengths are associated with increased stent symptoms, and patient height cut-offs have been suggested for these stents.22 Authors have advocated for direct measurement of the ureteral length before stent placement23 since height is not always a predictor of ureteral length.

In our study, we assessed patient pain scores for each given ureteral stent length in association with patient height since ureteral lengths were not routinely measured. We hypothesized for this secondary outcome that patients who were shorter than average for a given stent length would have increased pain symptoms at the time of removal due to a presumed oversizing of the stents and the potential for the distal end to cross the bladder midline. However, we did not detect such a difference. Possible explanations for this include appropriate stent length selection, or it may be that stent length is less important as a factor. Alternative suggestions include the possibility that the type of materials of each stent implanted may be comfortable, even if there is excess material in the bladder. A previous study has also found that multi-length compared to standard length stents do not affect pain scores, suggesting that material in the bladder does not affect pain.24 Regardless, our finding that patient height is not associated with pain scores for a given stent length is important, given that patient height is the most common factor that urologists use for selecting a stent length.25

Impact of method of stent removal on reported pain symptoms

Another factor that can impact stent-related symptoms is the presence or absence of a tether. The presence of a tether can be bothersome and may predispose to stent dislodgement. However, the absence of a tether necessitates cystoscopic removal. Patients experience some differences while stents are indwelling with and without a tether, including being more likely to stop sexual intercourse if a tether is in situ.26 Some authors have additional concerns about infection risk, additional symptoms, or dislodgement with the stents on a tether. There is as much as a 10% dislodgement rate when ureteral stents are left on a tether, compared to a reported 0% in the cystoscopic removal group.26 While the stent dislodgment rate with strings is low, women are more likely to accidentally dislodge their stent.27 The risk of infection with a tether remains controversial and unproven.28 However, patients have previously reported an increase in pain at the time of stent removal with the cystoscopic extraction method compared to the tether extraction method.29 Furthermore, the increased cost of cystoscopic removal is a consideration.30 These issues must be balanced with the potential for increased discomfort from the presence of a tether. In our study, however, no difference in pain scores was reported before stent removal with or without a tether. This indicates that the presence of the tether itself does not impact pain scores through urethral irritation, compared to no tether. This suggests that potential benefits in the group of patients with a tether do not have a drawback in terms of discomfort.

Limitations of this study include the observational nature of the data influenced by provider preferences, and the lack of capture of unanticipated care requirements after stent removal, including patient visits, telephone calls, messages, and emergency department visits. The PROMIS symptom scores include some questions recalling pain over the preceding 7 days which limit discrimination between short periods. Urinary symptoms from ureteral stents are notoriously problematic as well as difficult to quantify; using a validated tool such as the Ureteral Stent Symptom Questionnaire (USSQ) would have been ideal, but this registry was not originally designed to look only at ureteral stent symptoms, so the shorter PROMIS questions were utilized. This study was limited to Boston Scientific ureteral stents and may not be generalizable to other stent brands. Patient cultural factors, presence of chronic pain, or mental health conditions that were not assessed in detail could have influenced patient sensitivity and reporting of pain. The results may not be generalizable to a group of physicians with less experience in these procedures. There is a low but possible risk of bias as this was a registry done to support the European Union registration of stents and was not randomized. Furthermore, although symptoms were assessed on the day of stent removal, this may not capture the total disruption from stent symptoms that last longer for patients with a longer stent duration. We did not capture the indication for longer stent duration, which could be a confounder between groups as we might expect some of those patients with a longer stent indwelling time to have had a more complex initial procedure. There may have also been geographical differences in patterns of practice, or pathologic changes associated with long-term stenting could affect ongoing symptoms.

In this prospective, observational study, patients experienced similar degrees of pain regardless of short (0–7 days), medium (8–15 days), or long (16+ days), stent indwelling time after endourologic stone surgery. Overall, in this real-world, observational study, patients with long stent indwelling time may experience more days of discomfort, but this does not affect the pain intensity. Men experienced significantly less pain than women. No difference was observed for pain levels based on patient height/stent length or presence or absence of tether. Overall, these results may help physicians balance indwelling time with patient quality of life and suggest that sex may be a consideration when optimizing pain management.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank the research participants. They would also like to acknowledge Webb Kang for performing the statistical analysis, Angeline S. Andrew for assistance with manuscript preparation, and Debra Jovanovich and Reshma Rao for running the registry data collection effort.

Funding Statement

The registry was supported by Boston Scientific Corporation. The content of this publication is under the sole responsibility of its author/publisher and does not represent the views or opinions of Boston Scientific Corporation.

Author Contributions

Research conception and design: Connor M. Forbes, Ben H. Chew; Data acquisition: Alexander P. Glaser, Kazumi Taguchi, Amy E. Krambeck, Marcelino E. Rivera, Ojas Shah, Edouard Tariel, Channa Amarasekera, Shuzo Hamamoto, Dirk Lange, Wilson R. Molina, John J. Knoedler, Mitchell R. Humphreys, Karen L. Stern; Statistical analysis: Yuanyuan Ji. Drafting and approval of the manuscript: Connor M. Forbes, Ben H. Chew, K.F. Victor Wong, Runhan Ren. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials

Data is available on request from the authors. The data that support the findings of this study are avilable from the corresponding author, CMF, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from in the European Union (clinicaltrials.gov NCT04197583). This was an international registry including 10 centres in 4 countries (United States, Canada, France, and Japan). The registry had prospective data input from February 2020 to February 2023, with Institutional Review Board/Independent Ethics Committee approval at each site. Written informed consent was obtained for anonymized patient information to be published in this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Herout R, Halawani A, Wong VKF et al. Innovations in endourologic stone surgery: contemporary practice patterns from a global survey. J Endourol 2023;37(7):753–760. doi:10.1089/end.2023.0077. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Rezaee ME, Vollstedt AJ, Yamany T et al. Stent duration and increased pain in the hours after ureteral stent removal. Can J Urol 2021;28(1):10516–10521. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

3. Paul CJ, Brooks NA, Ghareeb GM, Tracy CR. Pilot study to determine optimal stent duration following ureteroscopy: three versus seven days. Curr Urol 2018;11(2):97–102. doi:10.1159/000447201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Dombeck C, Scales CD, McKenna K et al. Patients’ experiences with the removal of a ureteral stent: insights from in-depth interviews with participants in the USDRN STENTS qualitative cohort study. Urology 2023;178(1):26–36. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2023.04.018. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Ghani KR, Olumolade OO, Daignault-Newton S et al. What is the optimal stenting duration after ureteroscopy and stone intervention? impact of dwell time on postoperative emergency department visits. J Urol 2023;210(3):472–480. doi:10.1097/JU.0000000000003555. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Theckumparampil N, Elsamra SE, Carons A et al. Symptoms after removal of ureteral stents. J Endouro 2015;29(2):246–252. doi:10.1089/end.2014.0432. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Heidenberg DJ, Nauheim J, Grant C, Mi L, Van Der Walt C, Mufarrij P. Timing of ureteral stent removal after ureteroscopy on stent-related symptoms: a validated questionnaire comparison of 3 and 7 days stent duration. J Endourol 2024;38(1):82–87. doi:10.1089/end.2023.0189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Harper JD, Desai AC, Maalouf NM et al. Risk factors for increased stent-associated symptoms following ureteroscopy for urinary stones: results from STENTS. J Urol 2023;209(5):971–980. doi:10.1097/JU.0000000000003183. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Terwee CB, Peipert JD, Chapman R et al. Minimal important change (MICa conceptual clarification and systematic review of MIC estimates of PROMIS measures. Qual Life Res 2021;30(10):2729–2754. doi:10.1007/s11136-021-02925-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Joshi HB, Newns N, Stainthorpe A, MacDonagh RP, Keeley FXJr, Timoney AG. Ureteral stent symptom questionnaire: development and validation of a multidimensional quality of life measure. J Urol 2003;169(3):1060–1064. doi:10.1097/01.ju.0000049198.53424.1d. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Scotland KB, Almutairi K, Park E et al. Indwelling stents cause obstruction and induce ureteral injury and fibrosis in a porcine model. BJU Int 2023;131(3):367–375. doi:10.1111/bju.15912. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Lundeen CJ, Forbes CM, Wong VKF, Lange D, Chew BH. Ureteral stents: the good the bad and the ugly. Curr Opin Urol 2020;30(2):166–170. doi:10.1097/MOU.0000000000000701. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Forbes C, Scotland KB, Lange D, Chew BH. Innovations in ureteral stent technology. Urol Clin North Am 2019;46(2):245–255. doi:10.1016/j.ucl.2018.12.013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Janssen C, Buttyan R, Seow CY et al. A role for the hedgehog effector gli1 in mediating stent-induced ureteral smooth muscle dysfunction and aperistalsis. Urology 2017;104(Pt 3):242.e1–242.e8. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2017.01.029. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Kinn AC, Lykkeskov-Andersen H. Impact on ureteral peristalsis in a stented ureter. An experimental study in the pig. Urol Res 2002;30(4):213–218. doi:10.1007/s00240-002-0258-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Venkatesh R, Landman J, Minor SD et al. Impact of a double-pigtail stent on ureteral peristalsis in the porcine model: initial studies using a novel implantable magnetic sensor. J Endourol 2005;19(2):170–176. doi:10.1089/end.2005.19.170. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Lim JS, Sul CK, Song KH et al. Changes in urinary symptoms and tolerance due to long-term ureteral double-J stenting. Int Neurourol J 2010;14(2):93–99. doi:10.5213/inj.2010.14.2.93. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Irani J, Siquier J, Pirès C, Lefebvre O, Doré B, Aubert J. Symptom characteristics and the development of tolerance with time in patients with indwelling double-pigtail ureteric stents. BJU Int 1999;84(3):276–279. doi:10.1046/j.1464-410x.1999.00154.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Giannarini G, Keeley FXJr, Valent F et al. Predictors of morbidity in patients with indwelling ureteric stents: results of a prospective study using the validated Ureteric Stent Symptoms Questionnaire. BJU Int 2011;107(4):648–654. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09482.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Lai HHH, Yang H, Tasian GE et al. Contribution of hypersensitivity to postureteroscopy ureteral stent pain: findings from study to enhance understanding of stent-associated symptoms. Urology 2024;184:32–39. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2023.10.039. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Betschart P, Zumstein V, Piller A, Schmid HP, Abt D. Prevention and treatment of symptoms associated with indwelling ureteral stents: a systematic review. Int J Urol 2017;24(4):250–259. doi:10.1111/iju.13311. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Ho CH, Chen SC, Chung SD et al. Determining the appropriate length of a double-pigtail ureteral stent by both stent configurations and related symptoms. J Endourol 2008;22(7):1427–1431. doi:10.1089/end.2008.0037. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Kawahara T, Ito H, Terao H et al. Choosing an appropriate length of loop type ureteral stent using direct ureteral length measurement. Urol Int 2012;88(1):48–53. doi:10.1159/000332431. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Calvert RC, Wong KY, Chitale SV et al. Multi-length or 24 cm ureteric stent? A multicentre randomised comparison of stent-related symptoms using a validated questionnaire. BJU Int 2013;111(7):1099–1104. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11388.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Kwong J, Honey RJD, Lee JY, Ordon M. Determination of optimal stent length: a survey of urologic surgeons. Cent European J Urol 2023;76(1):57–63. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

26. Oliver R, Wells H, Traxer O et al. Ureteric stents on extraction strings: a systematic review of literature. Urolithiasis 2018;46(2):129–136. doi:10.1007/s00240-016-0898-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Althaus AB, Li K, Pattison E, Eisner B, Pais V, Steinberg P. Rate of dislodgment of ureteral stents when using an extraction string after endoscopic urological surgery. J Urol 2015;193(6):2011–2014. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2014.12.087. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Fröhlich M, Fehr J, Sulser T, Eberli D, Mortezavi A. Extraction strings for ureteric stents: is there an increased risk for urinary tract infections? Surg Infect 2017;18(8):936–940. doi:10.1089/sur.2017.165. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Kim DJ, Son JH, Jang SH, Lee JW, Cho DS, Lim CH. Rethinking of ureteral stent removal using an extraction string; what patients feel and what is patients’ preference?: a randomized controlled study. BMC Urol 2015;15(1):121. doi:10.1186/s12894-015-0114-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Juliebø-Jones P, Pietropaolo A, Haugland JN, Mykoniatis I, Somani BK. Current status of ureteric stents on extraction strings and other non-cystoscopic removal methods in the paediatric setting: a systematic review on behalf of the european association of urology (EAU) young academic urology (YAU) urolithiasis group. Urology 2022;160:10–16. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2021.11.022. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools