Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Redo testicular sperm aspiration (TESA) in men with severe oligoasthenoteratozoospermia (OAT) and obstructive azoospermia (OA)

1 Division of Urology, Department of Surgery, McGill University, Montreal, QC H4A 3J1, Canada

2 Department of Urology, King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Center, Jeddah, 23433, Saudi Arabia

3 Department of Medicine, McGill University, Montreal, QC H3A 0G4, Canada

4 Faculty of Medicine, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, 22252, Saudi Arabia

5 OVO Fertility Clinic, Montreal, QC H4P 2S4, Canada

* Corresponding Author: Armand Zini. Email:

Canadian Journal of Urology 2025, 32(4), 317-323. https://doi.org/10.32604/cju.2025.064517

Received 18 February 2025; Accepted 12 May 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

Background: Testicular sperm aspiration (TESA) is a minimally invasive testicular sperm retrieval technique that has been utilized in the treatment of male factor infertility. We sought to evaluate sperm retrieval outcomes of primary and redo TESA in men with severe oligoasthenoteratozoospermia (OAT) and obstructive azoospermia (OA). Methods: This is a retrospective analysis of consecutive TESAs (primary and redo) for men with severe OAT and OA performed between January 2011 and August 2022 at a high-volume infertility center. We compared TESA outcomes in men with severe OAT to those with OA and compared outcomes of men who underwent primary and redo TESA on the same testicular unit. Results: 439 TESAs (366 primary and 73 redo) in men with severe OAT (n = 133) and OA (n = 306) were included. Men with OA had significantly higher sperm retrieval rate (SRR) and motile SRR compared to men with severe OAT (99% vs. 95% and 98% vs. 83%, respectively, p < 0.05). The requirement for multiple biopsies and the total number of aspirates were significantly lower in men with OA compared to those with severe OAT (15% vs. 32% and 1.2 ± 0.5 vs. 1.4 ± 0.7, respectively, p < 0.05). In both groups, SRR, motile SRR, the requirement for multiple biopsies, and the total number of aspirates were not significantly different in primary compared to redo cases. Conclusion: Our data demonstrate that TESA retrieval rates are significantly higher in men with OA compared to those with severe OAT. The data also demonstrate that a redo TESA in these men is as effective as a primary TESA, suggesting that areas of active spermatogenesis are preserved 6 months after TESA.Keywords

After the advent of intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) in 1992, testicular biopsy has played a key role in the management of the infertile man.1 Testicular sperm aspiration (TESA) is one of many methods to retrieve testicular sperm. It is a minimally invasive treatment where testicular tissue is aspirated percutaneously. It can be done with a spermatic cord block alone or coupled with intravenous sedation.2

TESA has been utilized in men with obstructive azoospermia since 1993 and has become one of the most utilized methods, together with percutaneous epididymal sperm aspiration (PESA), for sperm retrieval in these men.3 Recently, studies have suggested that some couples with oligoasthenoteratozoospermia (OAT) and elevated sperm DNA fragmentation (SDF) may be candidates for testicular sperm retrieval.4 Couples with failed ICSI cycles or recurrent miscarriages and high SDF may benefit from testicular sperm retrieval and ICSI.4–6 Successful sperm retrieval with TESA is reportedly close to 100% in men with OA as well as in non-azoospermic men.7 However, it is unclear whether a redo TESA is associated with an equally high success rate in these men.

We speculate that the sperm retrieval rate (SRR) at redo TESA is lower than at primary TESA in men with OA and in those with OAT. As such, we planned to evaluate sperm retrieval outcomes of primary and redo TESA in men with OA. We also sought to examine sperm retrieval outcomes of primary and redo TESA in men with severe OAT and sperm high DNA fragmentation index (DFI), complete asthenozoospermia or necrozoospermia, and intermittent azoospermia or intermittent cryptozoospermia.

We performed a retrospective analysis of consecutive TESAs (primary and redo) for men with OA and severe OAT (<5 million sperm/mL, <32% progressive motility, and <4% normal forms), performed between January 2011 and August 2022 at OVO fertility clinic in Montreal, Canada. All TESAs were done for therapeutic purposes in conjunction with an ICSI cycle. All redo TESA cases involving the same testicular unit were done at least 6 months after the primary TESA based on evidence of ultrasound resolution of intra-testicular changes at 6 months post-testicular sperm retrieval.8 This study was reviewed by the Research and Development Committee at the OVO clinic and was approved as a quality control study. The principles of the Helsinki Declaration were respected. The patients provided consent for the sperm retrieval.

All patients in this study were evaluated by a fellowship-trained male infertility specialist (AZ). All men underwent a thorough clinical evaluation before the testicular sperm retrieval. Semen analysis was evaluated based on the World Health Organization criteria (WHO, 2010).9 Sperm DNA fragmentation was determined by TUNEL assay (terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate (dUTP) nick end-labeling) using flow cytometry and reported as sperm DNA fragmentation index (sperm DFI).10

Men undergoing TESA for OA had a definitive diagnosis of obstruction based on history (post-vasectomy, CBAVD), physical exam (testicular volume and consistency), and laboratory testing (e.g., semen analysis, serum FSH). The indications for TESA in men with severe OAT were high sperm DFI, complete asthenozoospermia or necrozoospermia, unexpected azoospermia or cryptozoospermia, multiple ICSI failures, severe OAT with intermittent azoospermia or intermittent cryptozoospermia.11,12 We excluded men with NOA and those with cryptozoospermia.

TESA was performed under local anesthesia as previously described.13 The larger testicle was aspirated first. We begin with a 1% xylocaine spermatic cord block (without epinephrine), injecting 10 mL of xylocaine into the cord. The scrotal skin and dartos muscle are also infiltrated with xylocaine.13–15 A 16-gauge angiocatheter (1.25-inch Cathlon IV Catheter; Smiths Medical International Ltd., Rossendale, UK) is inserted into the testis, and a 10 mL syringe containing 1–2 mL of sperm buffer is attached. Testicular tissue is retrieved by applying negative pressure to the syringe. The angiocatheter is removed, and the tissue is deposited into a sterile dish. The specimen is then teased apart and examined microscopically for spermatozoa identification. Gentle pressure is applied to the puncture site following angiocatheter needle removal. The procedure is repeated up to two additional times in the same testicular unit until five or more spermatozoa are obtained.14 If fewer than five spermatozoa are identified after unilateral TESA (following up to three aspirations), a contralateral TESA is performed. Should bilateral TESA prove unsuccessful, the ICSI cycle is terminated, the oocytes are cryopreserved, and micro-TESE-ICSI is scheduled subsequently.15,16 Couples requiring repeat sperm retrieval for another ICSI cycle after successful TESA typically undergo repeat TESA in the same unit.

Results are presented as percentages or mean +/-standard deviation. TESA characteristics and sperm retrieval outcomes were compared by Mann Whitney rank sum test or Fisher’s exact test. Mann-Whitney test was used because data points from the 2 study populations (e.g., primary and redo) do not have a normal distribution. The Fisher’s exact test was used because of the small sample size and expected low percent values. p-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Sample size estimates for comparison of OA and OAT groups (>100 patients per group) were based on the assumption of a 5–10% difference in SRR between OA and severe OAT groups (no data to guide this estimate). Sample size estimates for comparison of primary and redo TESA groups (>25 patients per group) were based on the assumption of a 33% difference in SRR between primary and redo TESA groups.17 Data analysis was done with GraphPad Prism version 7.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

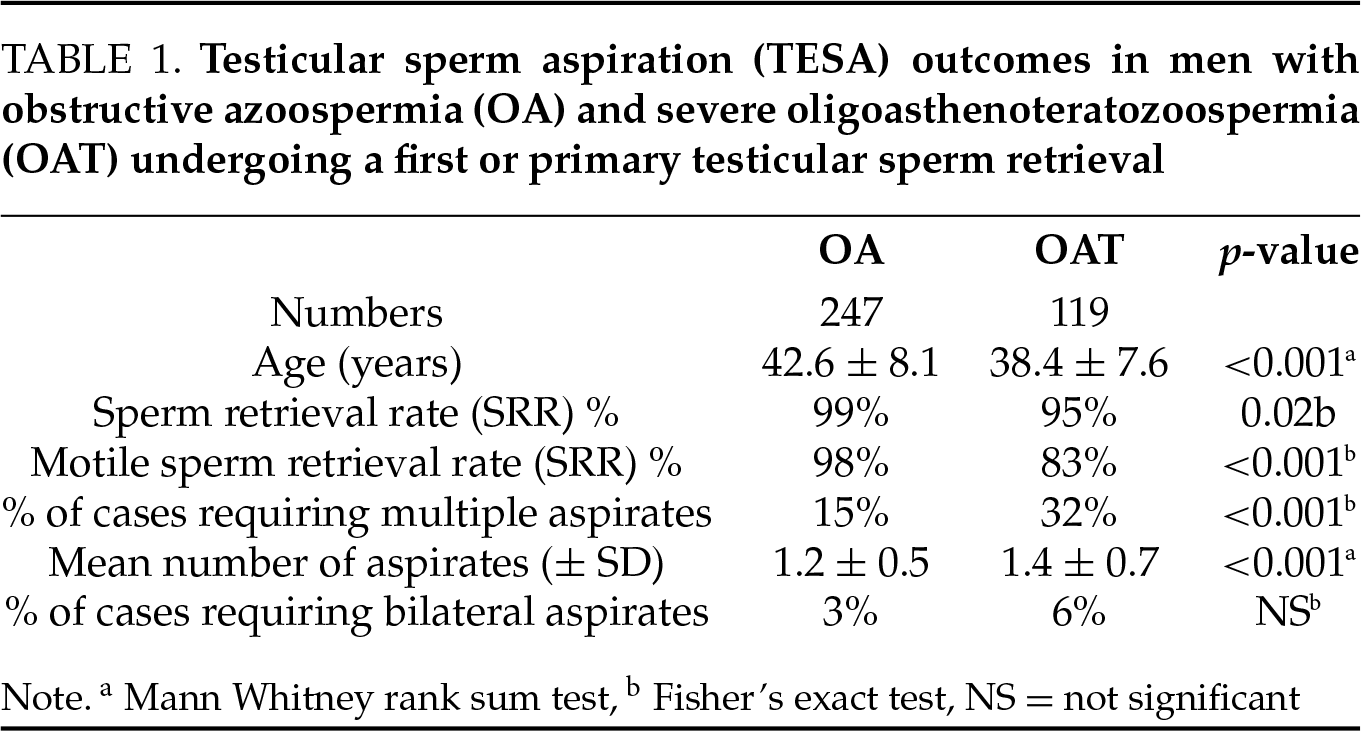

We identified 439 consecutive TESAs (primary and redo) in men with OA (n = 306) and severe OAT (n = 133) (Table 1). The etiologies of OA were post-vasectomy in 87% (265/306) of cases and CBAVD in 13% (41/306). The indications for TESA in men with OAT were elevated sperm DFI in 23% (30/133) of cases, asthenozoospermia or necrozoospermia in 10% (14/133), and other causes (unexpected azoospermia or cryptoozospermia, multiple ICSI failures, intermittent azoospermia and intermittent cryptozoospermia) in 67% (90/133).

In men undergoing a primary testicular sperm retrieval, the SRR was significantly higher in those with OA compared to those with severe OAT (99% vs. 95%, respectively, p = 0.02). Additionally, a higher proportion of retrievals with motile sperm was observed in the OA compared to the OAT group (98% vs. 83%, respectively, p < 0.001). The total number of testicular aspirates was significantly greater in men with severe OAT than in men with OA (1.4 ± 0.7 vs. 1.2 ± 0.5 aspirates per case, respectively, p < 0.001). However, the need for bilateral testicular aspiration did not differ significantly between the two cohorts.

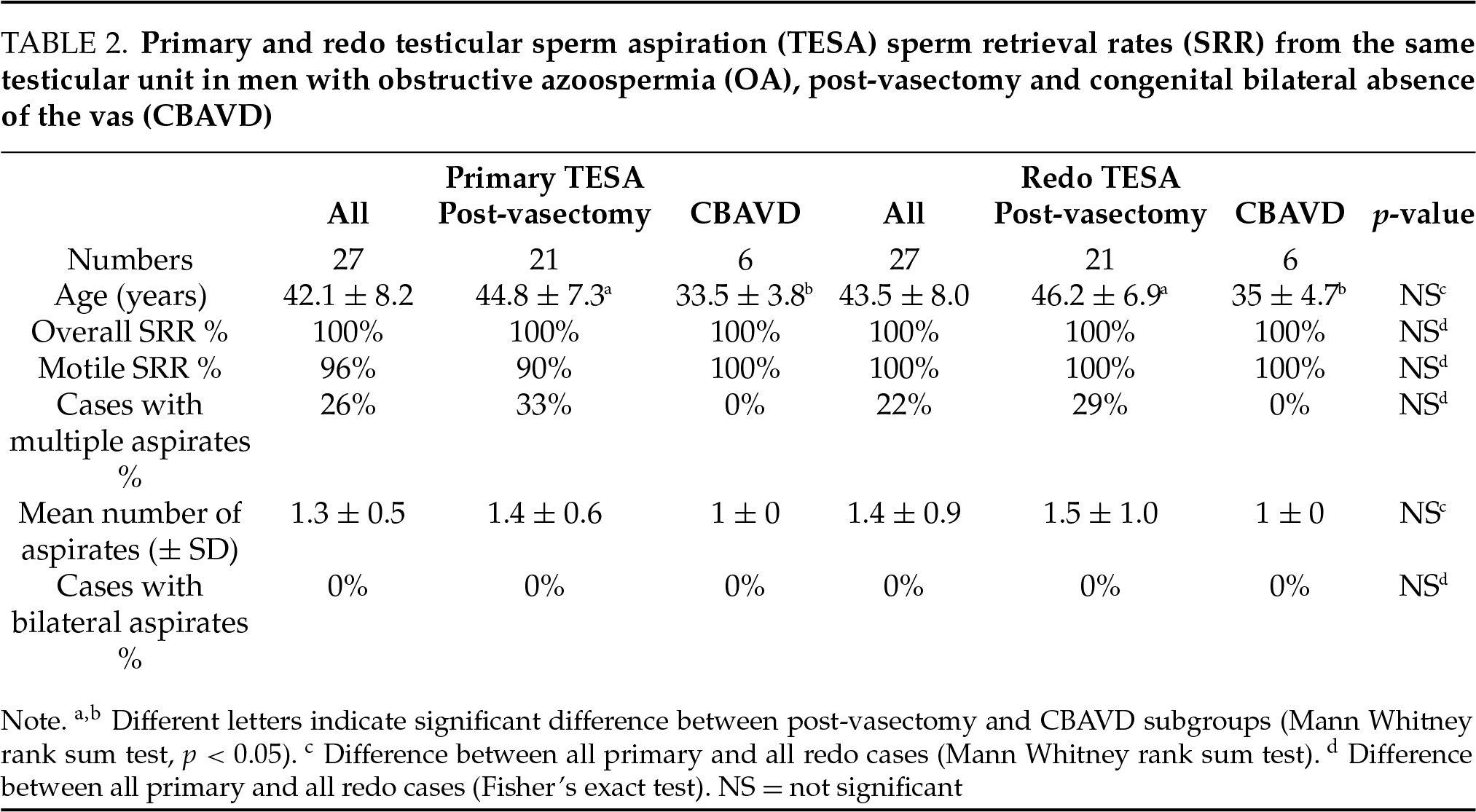

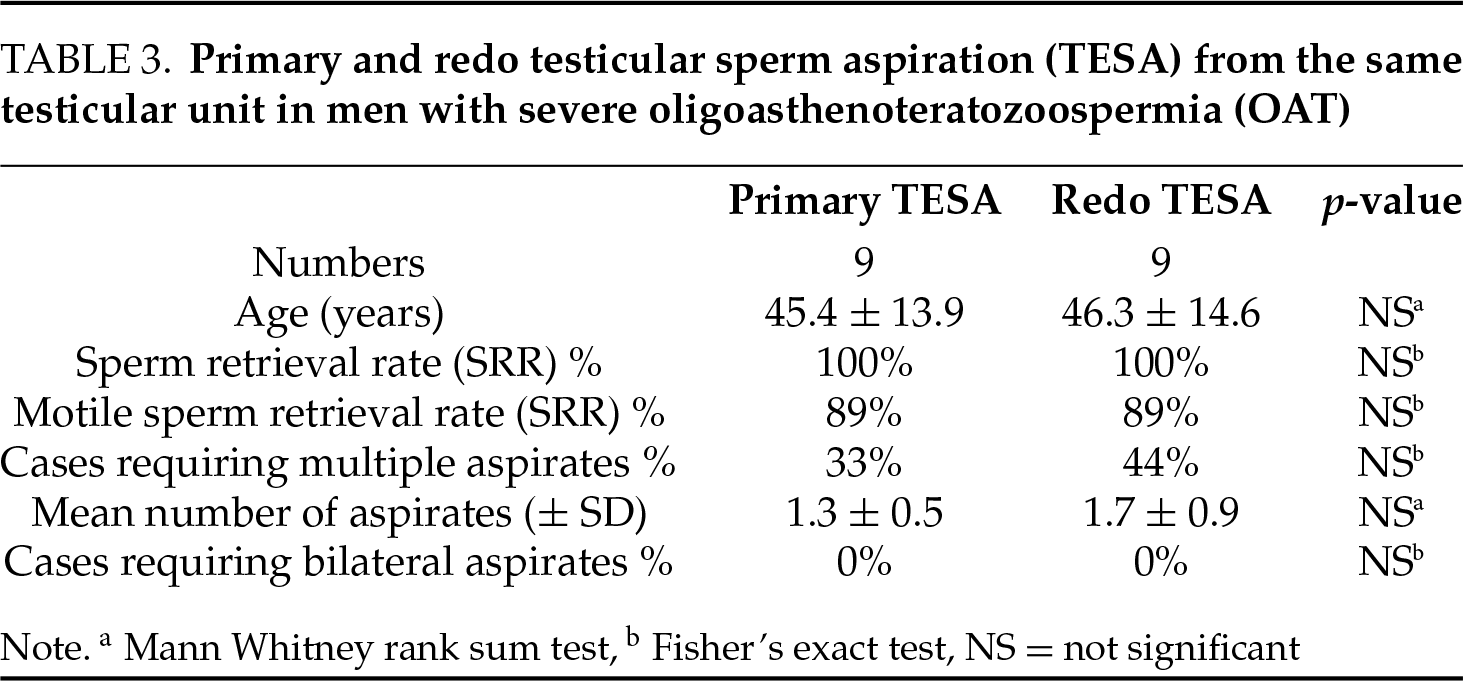

In a comparison of outcomes between primary TESA and redo TESA from the same testicular unit in men with OA, no significant differences were observed in SRR, the requirement for bilateral testicular aspiration, the proportion of cases with motile sperm in testicular aspirates, or total number of aspirates (Table 2). Similarly, in men with severe OAT, SRR, the requirement for bilateral aspiration, the proportion of cases with motile sperm in testicular aspirates, and the total number of aspirates at redo TESA were not significantly different from primary TESA from the same testicular unit (Table 3). The high sperm retrieval rates in men undergoing redo TESA suggest that areas of active spermatogenesis are preserved 6 months after TESA.

Comparison of redo TESA outcomes in men with OA and severe OAT revealed no significant differences in age, SRR, motile SRR, requirement for bilateral testicular aspiration, and total number of aspirates (data not shown). The comparable redo TESA retrieval outcomes in men with OA and severe OAT suggest a similar response to primary TESA in these groups of patients.

None of the patients suffered major complications (significant bleeding requiring admission or surgical exploration, scrotal infection). A small number of patients (both in the primary and redo groups) reported mild testicular pain beyond 48 h (data not shown).

In this retrospective comparative study, the results demonstrate that men with severe OAT have a significantly lower SRR and motile SRR compared to men with OA (95% vs. 99%, respectively). Men with severe OAT also required a significantly greater number of testicular aspirates than men with OA. The inferior outcomes in men with severe OAT relative to those with OA are not unexpected, knowing that a significant proportion of men with severe OAT have very low sperm concentration (<1 million/mL), with some experiencing intermittent cryptozoospermia or azoospermia, reflecting markedly impaired spermatogenesis.

In men with severe OAT, spermatogenesis may be severely impaired with a non-uniform pattern consisting of areas of normal or hypospermatogenesis and areas of maturation arrest.18 This is unlike men with OA from vasectomy where spermatogenesis is mostly active throughout the testis19 but with reduced germ cell populations (hypospermatogenesis) relative to normal controls.20,21 Moreover, a substantial percentage of vasectomized men have focal areas of testicular fibrosis.22 The difference in histologic pattern likely explains the lower SRR and need for a greater number of testicular aspirates, in men with severe OAT compared to men with OA. We previously published data on SRR in men with severe OAT, demonstrating an SRR of 100% when sperm concentration exceeds 1 million/mL, with a progressive decline in SRR as sperm concentration decreases.15

We evaluated redo TESA outcomes in men who previously underwent a TESA from the same testicular unit. In men with OA undergoing redo TESA, no significant differences were observed in SRR, need for bilateral testicular aspiration, percentage of cases with motile sperm in testicular aspirates, or total number of aspirates between the primary and redo TESA. Similarly, in men with severe OAT undergoing redo TESA, no significant differences were observed in SRR, motile SRR, requirement for bilateral testicular aspiration, or total number of aspirates between the primary and redo TESA. Westlander et al. (2001) performed primary and redo TESA (up to 5 aspirates per attempt) in a small series of men with OA and NOA.17 Unlike our report, they describe declining SRR at redo TESA but did not indicate the number of aspirates or need for bilateral aspirates required at primary and redo TESA. They reported a 100% (22/22) SRR in men with OA undergoing primary TESA, with SRRs of 96% (21/22) and 83% (5/6) for the first and second redo TESAs, respectively.17 In men with NOA, undergoing primary, first redo, and second redo TESA, SRR were 97%, 65%, and 79%, respectively. It is unclear why we did not observe a lower SRR at redo TESA as described by Westlander et al. (2001) but we suspect that it may be related to differences in technique, laboratory expertise, or patient population.

The favorable sperm retrieval outcomes at redo TESA (at least 6 months after primary TESA) in men with OA and severe OAT suggest that areas of active spermatogenesis are preserved 6 months after TESA. Westlander et al. (2001) conducted ultrasonographic follow-up in 35 men (61 testicular units) that underwent TESA. At 3 months post-TESA they observed intratesticular changes consistent with hematoma and/or inflammation in four cases (4/35, 11%), however, these resolved spontaneously after 6 to 9 months.23 Similarly, Raviv G et al. (2004) conducted serial ultrasonographic follow-ups in 32 men at 1.5, 3, and 6 months post-TESA. At 6 weeks post-TESA they observed intratesticular changes in 2 cases (2/32, 6%), however, these resolved spontaneously after 3 months.24 In contrast to TESA, TESE has been associated with more pronounced effects on the testicular parenchyma as described by Schlegel and Su (1997).8 In keeping with the observations from the current study, we recently reported on a group of men with OAT and observed that the post-TESA semen parameters were similar to the pre-intervention parameters.25

The study has several limitations. Firstly, there is a risk of confounding due to the retrospective nature of the study. Testicular volume can potentially affect the technical aspects of TESA (harder to perform TESA with testicular atrophy) and, the experience of the andrologist and the size of the harvested tissue sample can also influence the rapid identification of sperm. A formal histopathologic diagnosis was not obtained. This information may have strengthened our findings on sperm retrieval outcomes. Moreover, the number of patients with redo TESA in the same testicular unit is relatively small despite having collected data from a large series of TESA cases over 10 years. Nonetheless, a single surgeon performed all TESA procedures, the same laboratory was used for all cases, and the sperm retrieval outcomes reported in our study are in keeping with those from other centers. Another strength of our study resides in being, to our knowledge, the largest comparison of primary and redo TESA outcomes in men with OA and severe OAT. Large, prospective studies are required to validate the success rate of primary and redo testicular sperm retrieval and better quantify the potential effects of these procedures on testicular function and spermatogenesis.

Our data demonstrate that TESA retrieval rates are significantly higher in men with OA compared to those with severe OAT. The data also demonstrate that a redo TESA in these men is as effective as a primary TESA and suggest that areas of spermatogenesis are preserved 6 months after TESA. Additional prospective studies are needed to further establish the success rate of primary and redo testicular sperm retrieval and the impact of these techniques on spermatogenesis.

Acknowledgement

None.

Funding Statement

The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Armand Zini, Rabea Akram; data collection: Armand Zini; analysis and interpretation of results: Armand Zini, Michael Maalouf, Abdullah Alahmari, Rabea Akram, Abdulelah Elsayed; draft manuscript preparation: Abdullah Alahmari, Rabea Akram, Armand Zini. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials

Data available on request from the authors. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval

This retrospective study included human subjects. This study was reviewed by the OVO Research and Development Scientific Committee and received approval as a quality control study. Additionally, the principles of the Helsinki Declaration were followed. Consent for the procedure was obtained from patients.

Conflicts of Interest

Armand Zini: Shareholder in YAD Tech (Neutraceuticals)—not related to this study. Other authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Palermo G, Joris H, Devroey P, Van Steirteghem AC. Pregnancies after intracytoplasmic injection of single spermatozoon into an oocyte. Lancet 1992;340(8810):17–18. doi:10.1016/0140-6736(92)92425-f. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Gorgy A, Meniru GI, Naumann N, Beski S, Bates S, Craft IL. The efficacy of local anaesthesia for percutaneous epididymal sperm aspiration and testicular sperm aspiration. Hum Reprod 1998;13(3):646–650. doi:10.1093/humrep/13.3.646. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Craft I, Bennett V, Nicholson N. Fertilising ability of testicular spermatozoa. Lancet 1993;342(8875):864. doi:10.1016/0140-6736(93)92722-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Khoo CC, Cayetano-Alcaraz AA, Rashid R et al. Does testicular sperm improve intracytoplasmic sperm injection outcomes for nonazoospermic infertile men with elevated sperm DNA fragmentation? a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Urol Focus 2024;10(3):410–420. doi:10.1016/j.euf.2023.08.008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Schlegel PN, Sigman M, Collura B et al. Diagnosis and treatment of infertility in men: AUA/ASRM guideline part I. J Urol 2021;205(1):36–43. doi:10.1097/ju.0000000000001521. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Cano-Extremera M, Hervas I, Gisbert Iranzo A et al. Superior live birth rates, reducing sperm DNA fragmentation (SDFand lowering miscarriage rates by using testicular sperm versus ejaculates in intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) cycles from couples with high SDF: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biology 2025;14(2):130. doi:10.3390/biology14020130. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Esteves SC, Lee W, Benjamin DJ, Seol B, Verza SJr, Agarwal A. Reproductive potential of men with obstructive azoospermia undergoing percutaneous sperm retrieval and intracytoplasmic sperm injection according to the cause of obstruction. J Urol 2013;189(1):232–237. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2012.08.084. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Schlegel PN, Su LM. Physiological consequences of testicular sperm extraction. Hum Reprod 1997;12(8):1688–1692. doi:10.1093/humrep/12.8.1688. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. World Health Organization. WHO Laboratory Manual for the Examination and Processing of Human Semen. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2010. [Google Scholar]

10. Sharma RK, Sabanegh E, Mahfouz R, Gupta S, Thiyagarajan A, Agarwal A. TUNEL as a test for sperm DNA damage in the evaluation of male infertility. Urology 2010;76(6):1380–1386. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2010.04.036. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Loloi J, Petrella F, Kresch E, Ibrahim E, Zini A, Ramasamy R. The effect of sperm DNA fragmentation on male fertility and strategies for improvement: a narrative review. Urology 2022;168(1):3–9. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2022.05.036. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Agarwal A, Sharma RK, Gupta S et al. Sperm vitality and necrozoospermia: diagnosis, management, and results of a global survey of clinical practice. World J Mens Health 2022;40(2):228–242. doi:10.5534/wjmh.210149. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Alrabeeah K, Yafi F, Flageole C et al. Testicular sperm aspiration for nonazoospermic men: sperm retrieval and intracytoplasmic sperm injection outcomes. Urology 2014;84(6):1342–1346. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2014.08.032. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Alrabeeah K, Doucet R, Boulet E et al. Can the rapid identification of mature spermatozoa during microdissection testicular sperm extraction guide operative planning? Andrology2015;3(3):467–472. doi:10.1111/andr.12018. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Alkandari MH, Moryousef J, Phillips S, Zini A. Testicular sperm aspiration (TESA) or microdissection testicular sperm extraction (micro-tesewhich approach is better in men with cryptozoospermia and severe oligozoospermia?Urology 2021;154:164–169. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2021.04.037. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Alrabeeah K, Hakami B, Abumelha S et al. Testicular microdissection following failed sperm aspiration: a single-center experience. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2022;26(19):7176–7181. doi:10.26355/eurrev_202210_29905. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Westlander G, Rosenlund B, Söderlund B, Wood M, Bergh C. Sperm retrieval, fertilization, and pregnancy outcome in repeated testicular sperm aspiration. J Assist Reprod Genet 2001;18(3):171–177. doi:10.1023/a:1009459920286. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Anderson JB, Cooper MJ, Thomas WE, Williamson RC. Impaired spermatogenesis in testes at risk of torsion. Br J Surg 1986;73(10):847–849. doi:10.1002/bjs.1800731028. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Bagshaw HA, Masters JR, Pryor JP. Factors influencing the outcome of vasectomy reversal. Br J Urol 1980;52(1):57–60. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410x.1980.tb02920.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Raleigh D, O’Donnell L, Southwick GJ, de Kretser DM, McLachlan RI. Stereological analysis of the human testis after vasectomy indicates impairment of spermatogenic efficiency with increasing obstructive interval. Fertil Steril 2004;81(6):1595–1603. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.10.046. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Xiang Y, Luo P, Cao Y, Yang ZW. Long-term effect of vasectomy on spermatogenesis in men: a morphometric study. Asian J Androl 2013;15(3):434–436. doi:10.1038/aja.2012.154. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Jarow JP, Budin RE, Dym M, Zirkin BR, Noren S, Marshall FF. Quantitative pathologic changes in the human testis after vasectomy. A controlled study. N Engl J Med 1985;313(20):1252–1256. doi:10.1056/NEJM198511143132003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Westlander G, Ekerhovd E, Granberg S et al. Serial ultrasonography, hormonal profile and antisperm antibody response after testicular sperm aspiration. Hum Reprod 2001;16(12):2621–2627. doi:10.1093/humrep/16.12.2621. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Raviv G, Levron J, Menashe Y et al. Sonographic evidence of minimal and short-term testicular damage after testicular sperm aspiration procedures. Fertil Steril 2004;82(2):442–444. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.12.047. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Alkandari MH, Moryousef J, Zini A. Does testicular sperm retrieval adversely impact spermatogenesis over the long-term? Andrologia 2022;54(6):e14401. doi:10.1111/and.14401. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools