Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Improving surgical outcome reporting in lithiasis surgery: a comparative analysis of comprehensive complication index and clavien-dindo classification

1 Second Department of Urology, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Sismanogleio Hospital, Athens, 15126, Greece

2 School of Science and Technology, Hellenic Open University, Patras, 26335, Greece

* Corresponding Author: Stamatios Katsimperis. Email:

Canadian Journal of Urology 2025, 32(4), 271-282. https://doi.org/10.32604/cju.2025.066395

Received 08 April 2025; Accepted 16 July 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

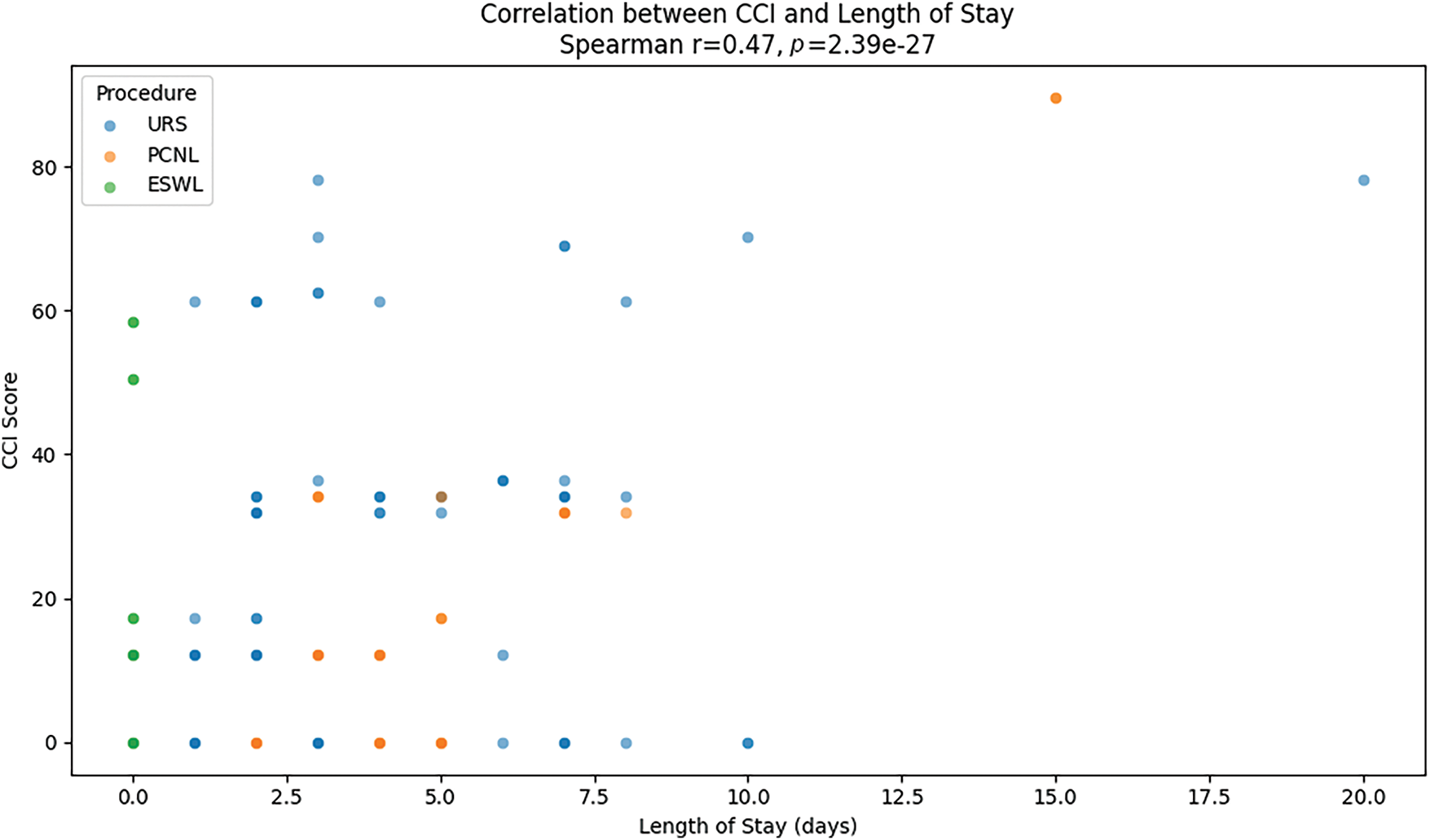

Background: Accurate complication reporting in endourology remains challenging, with the Clavien-Dindo Classification and Comprehensive Complication Index being the most commonly used systems. This study aimed to compare surgical outcomes and complication reporting in ureterolithotripsy (URL), percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL), and extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) using both systems. Methods: This prospective, single-center, non-interventional study included 473 patients undergoing URL, PCNL, or ESWL from October 2022 to October 2024. Demographic, stone-related, and procedural variables were recorded. Complications were classified using the CDC, and cumulative morbidity was assessed using CCI. Statistical analyses, including univariate and multivariate regression, were performed to identify predictors of higher CCI scores. Results: PCNL was associated with the highest complication rates, including an 11% transfusion rate. ESWL had the lowest complication burden, while URL demonstrated intermediate risk. CCI scores correlated positively with length of stay (LOS; r = 0.47), highlighting its ability to capture overall morbidity. Multivariate analysis identified stone size, operating time, and positive urine culture as significant predictors of higher CCI scores. The CCI provided a more comprehensive representation of morbidity compared to the CDC. Conclusions: CCI demonstrates superior sensitivity in evaluating postoperative morbidity compared to CDC, particularly in more invasive procedures such as PCNL. Standardized reporting frameworks incorporating CCI may enhance surgical outcome assessment in endourology.Keywords

Nephrolithiasis is a prevalent urological condition known to substantially impair patients’ quality of life.1,2 Over recent decades, its prevalence has gradually risen, affecting up to approximately 10% of the population.3,4 Treatment modalities such as Ureterolithotripsy (URL), Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy (PCNL), and Extracorporeal Shock Wave Lithotripsy (ESWL) are commonly used to manage kidney stones of various sizes and complexities.5–7 However, these procedures do carry a risk of intra- or postoperative complications, which may potentially compromise the results and exert significant financial pressures on healthcare systems.8,9 Therefore, meticulous and high-caliber documenting of procedure-related adverse events, coupled with suitable preoperative evaluation, is crucial. The Clavien-Dindo Classification (CDC) remains the most widely used framework for documenting surgical complications, owing to its simplicity and adaptability. However, since the CDC captures only the highest-grade complication per patient, alternative systems like the Comprehensive Complication Index (CCI) have been introduced to provide a more nuanced overview.10 The CDC categorizes complications into five grades, which are further divided into seven distinct levels (I, II, IIIa/IIIb, IVa/IVb, V), which represent a progression in severity. Grade I represents “any deviation from the norm,” while grade V signifies the patient’s death. The classification is based on the level of invasiveness required for the treatment of these complications. The CCI is based on the CDC but accounts for all accumulated complications and provides a continuous overall score between 0 and 100, with 100 indicating patient death.11 CCI has been validated in studies including patients undergoing PCNL and URL but not in those undergoing ESWL, which is also a commonly used form of stone treatment.12

In this prospective non-interventional study, we aimed to evaluate CCI, compared to CDC, as a tool for reporting complications in endourology procedures and ESWL, focusing on the ability of the system to assess cumulative morbidity; furthermore, we sought to determine clinical and procedural factors that may significantly influence CCI.

This is a prospective non-interventional study conducted from October 2022 to October 2024 in the University Urology Department in a tertiary hospital. The collection of data was performed in patients with kidney stones, diagnosed with plain KUB (kidney, ureter, bladder) and/or Computed Tomography (CT) scan, who underwent one of the following three procedures: URL, PCNL, and ESWL, depending on the size of the stone. PCNL was performed on stones >2 cm, while ESWL and/or URL were performed on stones ≤2 cm according to the European Association of Urology guidelines.

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Hospital (Protocol Number: 20978/19.10.22). The study was registered on clinicaltrials.gov with ID: 67127, clinical trials ID: NCT05593783.

All PCNL cases were performed in the prone position using a 26 French nephroscope. Puncture of the collecting system was performed under radiographic guidance and tract dilatation was carried out with Amplatz and balloon dilators. Lithotripsy was performed with Swiss Lithoclast (a combination of ultrasound and pneumatic lithotripsy). In the URL, three types of ureteroscopes were used, namely the semirigid 7/12 French Ureterorenoscope, the LithoVue™ Single-Use Digital Flexible Ureteroscopes and the Karl Storz Flex-X2 Ureteroscope. A 30-W Auriga XL holmium-YAG laser was used for stone disintegration. ESWL was performed using Dornier lithotripter S II.

Data collection and complication assessment

Patient demographics (age, gender, body mass index, comorbidities, anticoagulant use), stone-related data (maximum stone size, anatomic location of stone, number of stones, presence of hydronephrosis preoperatively, presence of double-J stent catheter preoperatively, positive urine culture, preoperative chemoprophylaxis) as well as operation-related data (type of anesthesia, operation time, hospitalization time) were reported. Finally, all possible complications were recorded intraoperatively, immediately postoperatively and up to 30 days following surgery. Complications were assessed using the CDC and the cumulative CCI was calculated for each patient using the freely available online tool www.assessurgery.com. Each CDC grade is assigned to a specific CCI value and a weight of complication (wC) as follows:

· CDC-I CCI score 8.66 wC1 = 300

· CDC-II CCI score 20.92 wC1 = 1750

· CDC-IIIa CCI score 26.22 wC1 = 2750

· CDC-IIIb CCI score 33.73 wC1 = 4550

· CDC-IVa CCI score 42.43 wC1 = 7200

· CDC-IVb CCI score 46.23 wC1 = 8550

· CDC-V always results in a CCI score of 100

These values are also summarized in Table 1 for reference.

The total CCI score is then calculated based on the following formula:

Patients with urinary lithiasis who were to undergo one of the following three procedures: ureterolithotripsy, percutaneous nephrolithotomy and extracorporeal shockwave nephrolithotripsy, depending on the size of the stone, were included in the study. All participants signed an informed consent form. Patients who had a recent (less than a month’s time) similar operation, as well as those who were found unable to understand the protocol and the procedures, were excluded.

A series of statistical analyses was performed to assess patient outcomes and identify significant predictors of complications. To describe continuous variables, the mean/standard deviation were used. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to investigate the distribution of the data. The absolute number and the corresponding percentage were used to describe the qualitative variables. For the comparison of continuous variables, the parametric t-test was used when the data followed a normal distribution and the Mann-Whitney U test when they did not follow a normal distribution. Chi-square and Fisher’s exact test were used to compare qualitative variables. Descriptive statistics were calculated for each group of patients (URL, PCNL, ESWL) and presented in a comprehensive baseline table. Univariate linear regression analyses were conducted to evaluate potential predictors of CCI, followed by multivariate regression analysis to identify independent predictors. The reported coefficients represent regression estimates (e), not correlation coefficients. An Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was conducted to assess the differences in CCI scores across the different procedures. Due to different complication profiles of each surgical technique and in order to assess CCI scores, we did not perform a pooled analysis of the three techniques together. To compare the overall morbidity of the cumulative CCI and the non-cumulative CDC, the paired Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test was used. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was used to test the correlation of LOS with the cumulative CCI and a scatter plot was created to illustrae the positive correlation between LOS and CCI.

This study did not include a prior sample size calculation, as its primary aim was to provide a comprehensive assessment of postoperative complications using both CCI and the CDC. Given the observational, non-randomized nature of the study, all eligible patients treated within the study period were included, ensuring a real-world representation of surgical outcomes. The focus of this study was on evaluating the applicability and effectiveness of complication grading systems rather than testing a predefined hypothesis. While no formal power analysis was performed, the sample size was considered sufficient for descriptive and comparative analysis based on previous studies of similar scope.

Patients’ baseline demographic characteristics

The baseline characteristics of the patients are presented in Table 2. Comparative analysis of baseline variables revealed statistically significant differences in age, stone size, stone location, and several comorbidities across the treatment groups (ESWL, URL, PCNL), as shown in Table 2. These variations align with the expected clinical selection criteria for each modality and were anticipated given the observational, real-world design of the study.

A total of 473 patients were enrolled in the study, of which 211 underwent URL, 209 ESWL and 53 PCNL. The baseline characteristics showed notable differences across the three treatment groups. PCNL was utilized for patients with the largest stones, which is consistent with the more invasive nature of this procedure. ESWL was predominantly used for patients with smaller stones, making it the least invasive of the three modalities. In our study, patients undergoing ESWL were, on average, older than those undergoing PCNL. This difference may reflect clinical considerations such as comorbidities and suitability for invasive procedures. By contrast, BMI was comparable between the three groups.

Frequency and severity of complications

The frequency of complications was assessed using the Clavien-Dindo classification. Tables 3–5 list all complications occurring following the procedures and their management. A total of 8, 7 and 4 different types of complications occurred in the URL, PCNL and ESWL cohorts, respectively. The most common complication for patients who underwent URL was pain (101 out of 211 patients, 47.87%), followed by urinary tract infection (UTI) (37 out of 211 patients, 17.54%). Severe complications such as sepsis were observed in 12 patients (5.69%). Similarly, in the PCNL cohort, the most common complication was pain (36 out of 53 patients, 68%), but at a higher rate compared to URL. Table 4 also shows a high transfusion rate for PCNL (11.3%), which could reflect the complexity or severity of the cases. Regarding ESWL, the complication rate was relatively low as expected, with the most common complications being pain (17 out of 209 patients, 8.13%) and mild hematuria (7 out of 209 patients, 3.34%), which were dealt with conservatively.

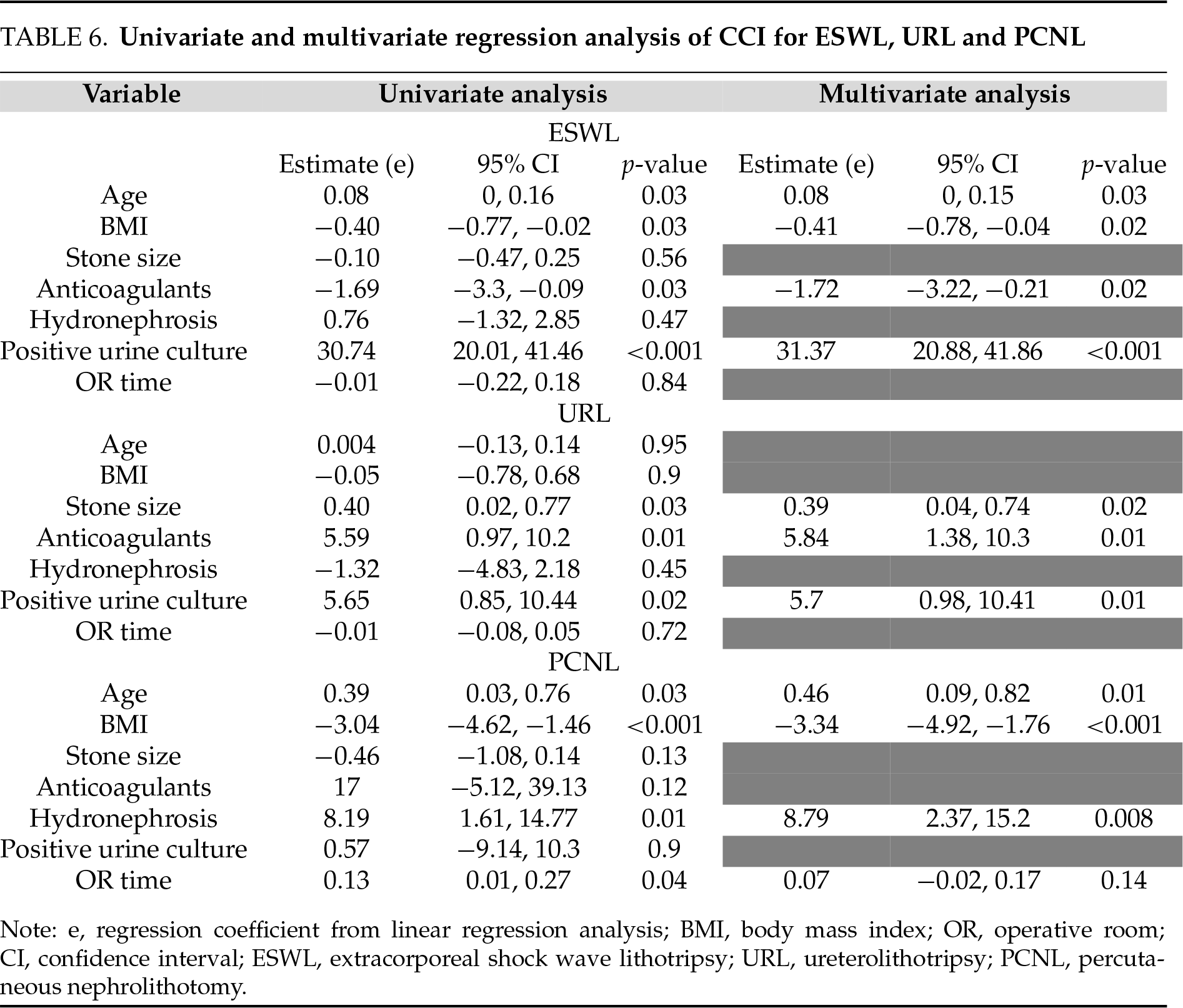

Univariate and multivariate regression analysis of CCI for ESWL, URL and PCNL

A univariate linear regression analysis was conducted to identify potential predictors of CCI (Table 6). The reported values represent regression coefficients (estimates, denoted as e) rather than correlation coefficients. Age showed a weak positive association with CCI for the ESWL group (e = 0.08) and a stronger association in the PCNL group (e = 0.39). BMI was negatively associated with CCI in the ESWL and PCNL groups (e = −0.40 and e = −3.04, respectively). Stone size showed a positive association with CCI in the URL group (e = 0.4), while OR time had a weak positive association with CCI in PCNL patients (e = 0.13). Positive urine culture was significantly associated with higher CCI in the ESWL (e = 30.74) and URL (e = 5.65) groups. OR time showed a positive association with CCI in PCNL patients (e = 0.13). A multivariate regression model was used to identify independent predictors of CCI (Table 6). BMI remained inversely associated with CCI in both the ESWL and PCNL groups, indicating that patients with higher BMI may experience fewer complications. OR time (e = 0.07) and the presence of hydronephrosis (e = 8.79) were positively associated with CCI in patients undergoing PCNL. Positive urine culture remained a significant predictor of higher CCI scores in both the ESWL (e = 31.37) and URL (e = 5.7) groups, consistent with univariate results. Stone size also remained positively associated with CCI (e = 0.39) in the URL group. The use of anticoagulants yielded contradictory results, with a positive association in the URL group (e = 5.84) and a negative association in the ESWL group (e = −1.72).

Comparison between the cumulative CCI and the non-cumulative CDC

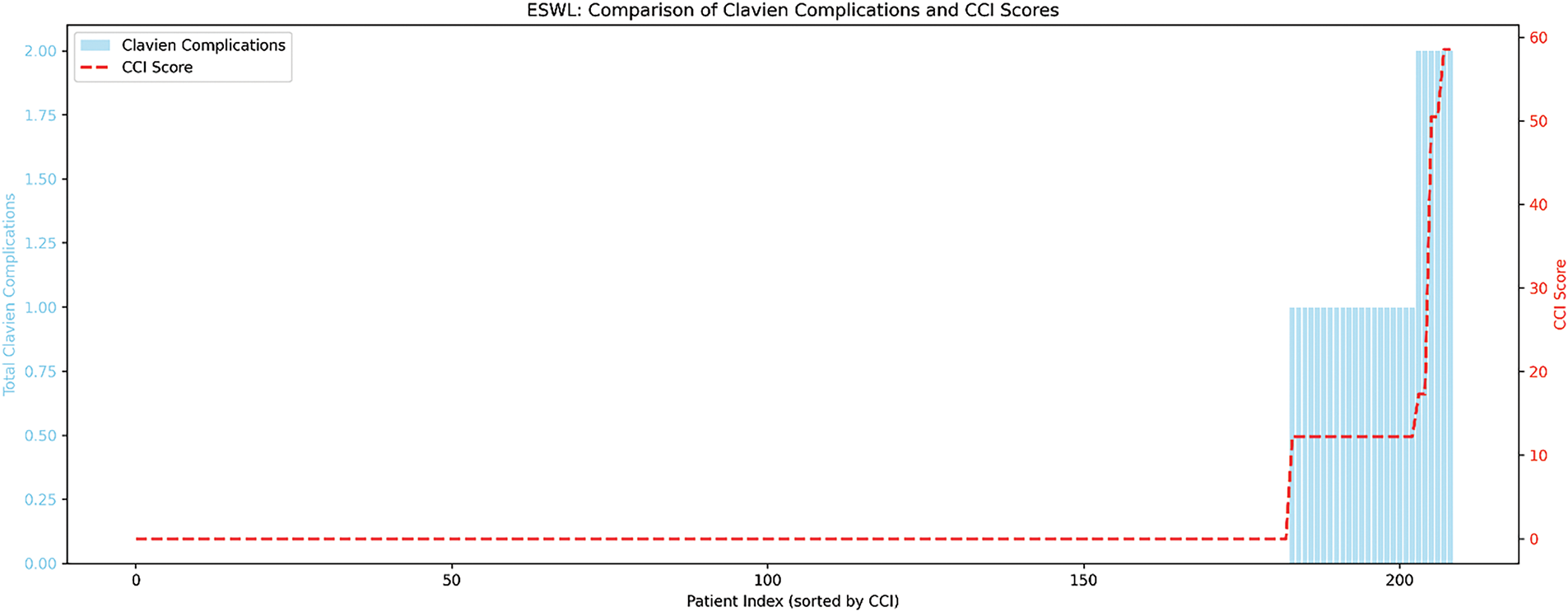

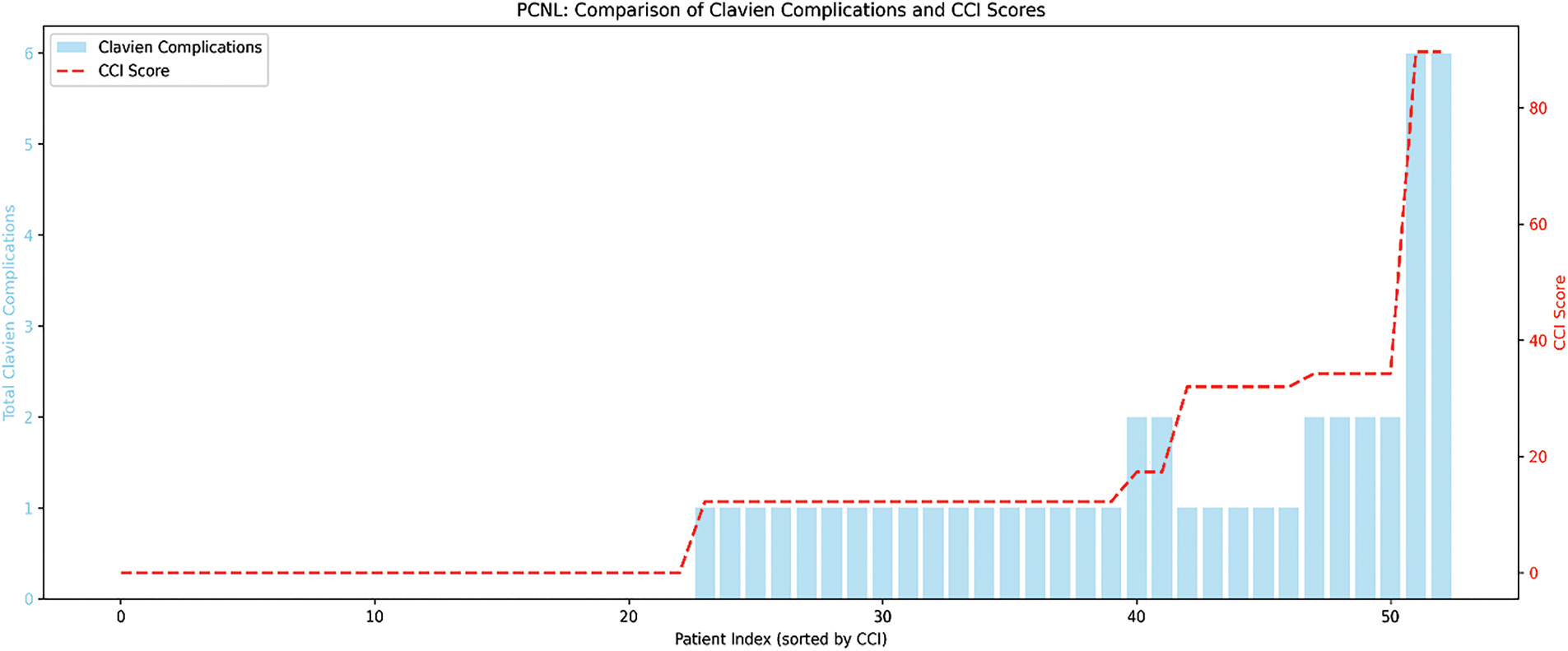

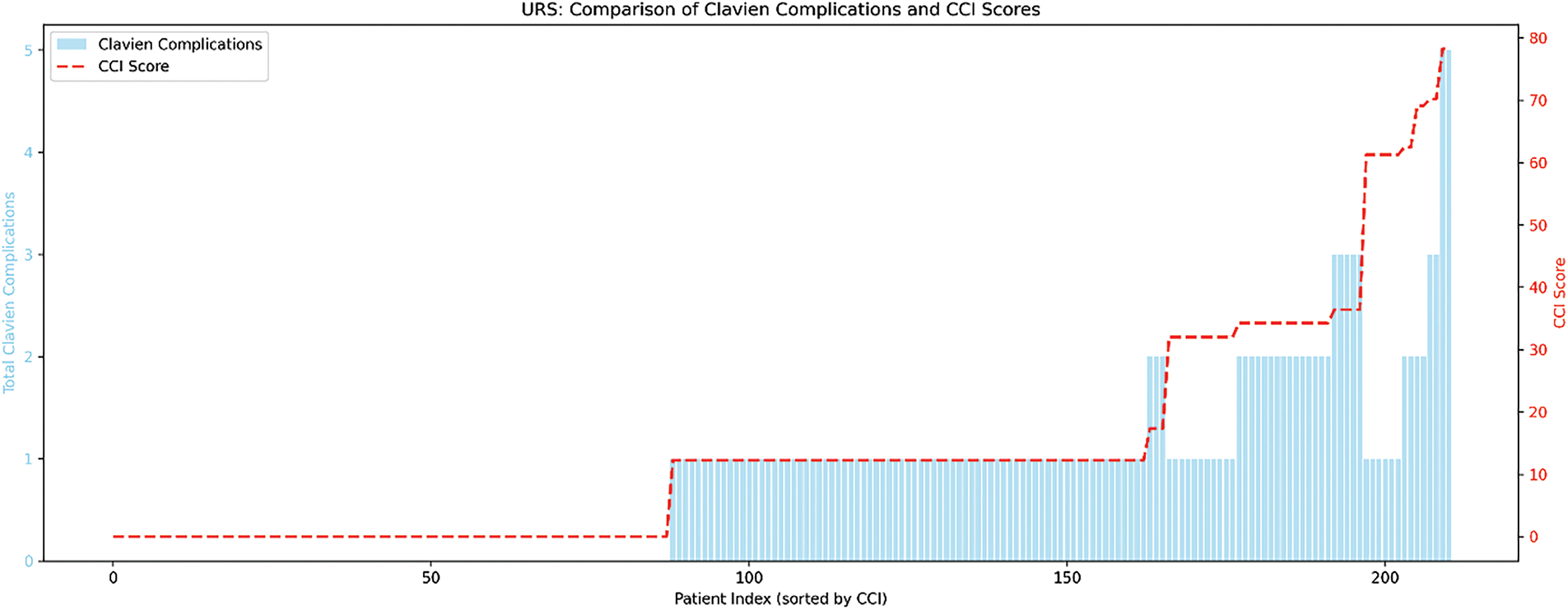

To compare the overall morbidity of cumulative CCI and non-cumulative CDC, the paired Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test was used. In Figures 1–3, comparisons of the total number of complications (using Clavien grades) with the corresponding CCI scores for each procedure are demonstrated. Mean cumulative CCI and mean non-cumulative CDC for ESWL were 1.750 and 0.153, respectively. The ESWL plot revealed that while in the majority of cases there were low complication rates (as indicated by both metrics), a marked increase in CCI scores in a subset of patients with higher grade CDC complications was noticed. In contrast, CDC values remain relatively consistent with smaller fluctuations, reflecting their non-cumulative nature. This comparison highlights the ability of the CCI to provide a more nuanced representation of overall complication severity, particularly in patients with multiple or severe complications, compared to the CDC. Similarly, in the URL and PCNL plots, the cumulative nature of the CCI is evident from its gradual increase across the cohorts, with a notable sharp rise in a subset of patients with higher complication burdens. In comparison, the CDC scores remain consistent with stepwise increments. For PCNL and URL, the comparison between the mean cumulative CCI and the mean non-cumulative CDC revealed significant differences (PCNL cumulative CCI mean: 9.526 vs. non-cumulative CDC mean: 0.868; URL cumulative CCI mean: 9.640 vs. non-cumulative CDC mean: 0.791).

Figure 1: Comparison between cumulative CCI and non-cumulative CDC for ESWL. ESWL, Extracorporeal Shock Wave Lithotripsy; CCI, Comprehensive Complication Index; CDC, Clavien Dindo Classification

Figure 2: Comparison between cumulative CCI and non-cumulative CDC for PCNL. PCNL, Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy; CCI, Comprehensive Complication Index; CDC, Clavien Dindo Classification

Figure 3: Comparison between the cumulative CCI and non-cumulative CDC for URL. URL, Ureterolithotripsy; CCI, Comprehensive Complication Index; CDC, Clavien Dindo Classification

Correlation with the length of stay (LOS)

Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was used to test the correlation of LOS with the cumulative CCI (Figure 4). This scatter plot illustrates the positive correlation between LOS and CCI. Patients with higher CCI scores generally experienced longer hospital stays, with a Spearman correlation of r = 0.47, indicating a moderate positive relationship.

Figure 4: Correlation between CCI and length of stay (LOS). The scatter plot illustrates the association between Comprehensive Complication Index (CCI) scores and hospital length of stay (LOS). Each dot represents an individual patient. Darker dots indicate overlapping or accumulation of data points at the same or very similar coordinates, reflecting multiple patients with identical or nearly identical CCI and LOS values

This study utilizes and validates the Comprehensive Complication Index (CCI) in the context of endourological treatment for urinary lithiasis, using data from a large patient cohort at a tertiary university referral center. To the best of our knowledge, it is the first study to include extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy (ESWL) as part of the analysis for kidney stone treatment.

The CCI was initially introduced in general surgery,11,13 Since then it has rapidly gained popularity in urologic oncology.14–16 Moreover it has been validated in various other urological procedures.12 Previous studies have demonstrated that the CCI can be effectively utilized in endourological treatments to enhance the reporting of postoperative complications.17 Our findings, consistent with those of Grüne et al., indicate that the CCI correlates more strongly with postoperative complications than the Clavien-Dindo Classification.12 The comparison between the cumulative CCI and the non-cumulative CDC underscores the CCI’s ability to provide a more nuanced representation of overall complication severity, particularly in patients with multiple or severe complications. This distinction is especially evident in patients undergoing PCNL compared to those treated with ESWL. Patients treated with PCNL experienced a higher incidence of complications, reflecting the invasive nature of the procedure, which was clearly captured by the CCI values.

In our study, baseline characteristics also showed notable differences across the three treatment groups. PCNL was reserved for patients with the largest stones (mean stone size of 30.1 mm). ESWL was predominantly used for patients with smaller stones, making it the least invasive of the three modalities. Complication analysis revealed that URL was associated with more frequent low-grade complications (e.g., pain and minor bleeding), which nonetheless were generally manageable and did not require significant medical intervention. ESWL had a lower frequency of Grade I complications compared to URL and lower complications compared to PCNL. A high transfusion rate (11%) was noticed in the PCNL group, potentially reflecting the complexity or severity of the cases. Several other studies have reported similar findings.18–20

Both the univariate and multivariate analyses highlighted OR time as a significant predictor of higher CCI scores in patients treated with PCNL, indicating that prolonged procedures are associated with increased risk of complications. Similar findings have been reported in the literature.21–22 Sugihara et al. demonstrated that extended operative time is a significant and independent risk factor for severe adverse events following PCNL.22 Interestingly, unlike in PCNL, operative time did not emerge as a significant predictor of complications in the URL group. This may be attributed to the relatively short and homogeneous operative times in our cohort, which could have minimized their predictive impact on postoperative morbidity.

In the ESWL and URL groups, a positive urine culture was a significant predictor of higher CCI scores, which is in line with the current literature.23–25 Furthermore, stone size was demonstrated to have a significant positive association with CCI (e = 0.39) in patients undergoing URL. Disintegration of larger stones typically requires prolonged operation time, which, in turn, has been shown to be associated with an increased risk of complications.26

Interestingly, BMI showed an inverse association with CCI in patients treated with PCNL and ESWL. This observation may be explained by the fact that increased BMI, and consequently greater skin-to-stone distance, may lead to attenuation of the transfer of the shockwaves to the kidney, thus acting as a protective factor in patients undergoing ESWL.27,28 On the other hand, this unexpected finding may also present a statistical bias rather than a clinically significant observation. The mean BMI in our cohort was relatively modest (26.0 for PCNL), with a narrow range amongst patients. Additionally, the small sample size (53 patients) may have limited the ability to detect a true underlying relationship between BMI and complication rates, thereby contributing to this paradoxical finding.

CCI was found to correlate relevantly with LOS. Patients with higher CCI scores generally experienced longer hospital stays, with a Spearman correlation of r = 0.47, indicating a moderate positive relationship. This finding aligns with the results of previous studies, which similarly reported an association between higher CCI values and extended hospital stays.29,30

This study has several limitations. Firstly, it was conducted at a single tertiary center, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to broader, multi-institutional settings. Secondly, the relatively small sample size of certain subgroups, particularly the PCNL cohort, may have reduced the statistical power to detect subtle associations or rare complications. Thirdly, the observational, non-interventional design of the study inherently limits the ability to establish causality between predictive factors and the CCI. Additionally, variability in surgeon experience and procedural techniques, which were not standardized in this study, could have influenced outcomes. Another limitation of this study is the absence of a prior sample size calculation, which may affect statistical power for detecting small effect sizes, particularly in the PCNL cohort. However, the inclusion of all eligible patients during the study period ensures a representative sample, reducing selection bias. Furthermore, the comprehensive assessment of complications using both CCI and CDC provides valuable clinical insights, regardless of sample size constraints. Future studies with larger cohorts may help refine these findings and validate the observed trends. Finally, while the study comprehensively assessed complications using both the CDC and CCI, long-term outcomes and patient-reported quality of life were not evaluated, which could provide a more holistic perspective on the clinical impact of complications.

Future research should focus on incorporating patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) into the CCI framework to enable a more holistic evaluation of surgical success. This approach will enable a combination of clinical outcomes with patient-centered metrics, such as quality of life and satisfaction. Additionally, leveraging advancements in machine learning and predictive analytics could provide valuable tools for identifying preoperative predictors of high CCI scores, facilitating personalized risk stratification and the implementation of targeted interventions.

This study highlights the value of the CCI as a robust tool for evaluating and reporting postoperative outcomes in patients undergoing treatment for urinary lithiasis with ESWL, URL, and PCNL. By providing a cumulative and nuanced assessment of complications, the CCI offers a more comprehensive reflection of postoperative morbidity than the Clavien-Dindo Classification, particularly in capturing the complexity of adverse events associated with more invasive procedures such as PCNL. Our findings underline the significant role of clinical and procedural factors, including BMI, stone size, and positive urine culture, as predictors of complication severity. While the results validate the utility of the CCI in this context, the study also emphasizes the need for standardized reporting frameworks and larger multicenter trials to further refine complication assessment and improve surgical outcome reporting in endourology.

Acknowledgement

Not applicable.

Funding Statement

The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions

Study conception and design: Stamatios Katsimperis, Iraklis Mitsogiannis; Data collection: Stamatios Katsimperis, Themistoklis Bellos; Statistical analysis: Lazaros Tzelves, Georgios Feretzakis, Panagiotis Deligiannis; Data analysis and interpretation: Stamatios Katsimperis, Lazaros Tzelves, Georgios Feretzakis; Drafting of the manuscript: Stamatios Katsimperis; Supervision: Iraklis Mitsogiannis, Andreas Skolarikos, Athanasios Papatsoris. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials

Not available.

Ethics Approval

The research received approval from the Institutional Review Board of Sismanogleio Hospital under Protocol Number: 20978/19.10.22.

Informed Consent

All patients provided written informed consent prior to participation in the study, in accordance with institutional and ethical guidelines.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. New F, Somani BK. A complete world literature review of quality of life (QOL) in patients with kidney stone disease (KSD). Curr Urol Rep 2016;17(12):88. doi:10.1007/s11934-016-0647-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Stern KL, Gao T, Antonelli JA et al. Association of patient age and gender with kidney stone related quality of life. J Urol 2019;202(2):309–313. doi:10.1097/ju.0000000000000291. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Chewcharat A, Curhan G. Trends in the prevalence of kidney stones in the United States from 2007 to 2016. Urolithiasis 2021;49(1):27–39. doi:10.1007/s00240-020-01210-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Stamatelou K, Goldfarb DS. Epidemiology of kidney stones. Healthcare 2023;11(3):424. doi:10.3390/healthcare11030424. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Doizi S, Traxer O. Flexible ureteroscopy: technique, tips and tricks. Urolithiasis 2018;46(1):47–58. doi:10.1007/s00240-017-1030-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Skolarikos A, Alivizatos G, de la Rosette JJ. Percutaneous nephrolithotomy and its legacy. Eur Urol 2005;47(1):22–28. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2004.08.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Setthawong V, Srisubat A, Potisat S, Lojanapiwat B, Pattanittum P. Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) versus percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL) or retrograde intrarenal surgery (RIRS) for kidney stones. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2023;8(8):Cd007044. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007044.pub4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Eappen S, Lane BH, Rosenberg B et al. Relationship between occurrence of surgical complications and hospital finances. Jama 2013;309(15):1599–1606. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.2773. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Geraghty RM, Cook P, Walker V, Somani BK. Evaluation of the economic burden of kidney stone disease in the UK: a retrospective cohort study with a mean follow-up of 19 years. BJU Int 2020;125(4):586–594. doi:10.1111/bju.14991. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Katsimperis S, Bellos T, Manolitsis I et al. Reporting and grading of complications in urological surgery: current trends and future perspectives. Urol Res Pract 2024;50(3):154–159. doi:10.5152/tud.2024.24050. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Slankamenac K, Graf R, Barkun J, Puhan MA, Clavien PA. The comprehensive complication index: a novel continuous scale to measure surgical morbidity. Ann Surg 2013;258(1):1–7. doi:10.1097/SLA.0b013e318296c732. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Grüne B, Kowalewksi KF, Waldbillig F et al. The Comprehensive Complication Index (CCI) for improved reporting of complications in endourological stone treatment. Urolithiasis 2021;49(3):269–279. doi:10.1007/s00240-020-01234-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Cloyd JM, Mizuno T, Kawaguchi Y et al. Comprehensive complication index validates improved outcomes over time despite increased complexity in 3707 consecutive hepatectomies. Ann Surg 2020;271(4):724–731. doi:10.1097/sla.0000000000003043. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Kowalewski KF, Müller D, Mühlbauer J et al. The comprehensive complication index (CCIproposal of a new reporting standard for complications in major urological surgery. World J Urol 2021;39(5):1631–1639. doi:10.1007/s00345-020-03356-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Vetterlein MW, Klemm J, Gild P et al. Improving estimates of perioperative morbidity after radical cystectomy using the european association of urology quality criteria for standardized reporting and introducing the comprehensive complication index. Eur Urol 2020;77(1):55–65. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2019.08.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Huang H, Zhang Z, Hao H, Wang H, Shang M, Xi Z. The comprehensive complication index is more sensitive than the Clavien-Dindo classification for grading complications in elderly patients after radical cystectomy and pelvic lymph node dissection: Implementing the European Association of Urology guideline. Front Oncol 2022;12:1002110. doi:10.3389/fonc.2022.1002110. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Waldbillig F, Nientiedt M, Kowalewski KF et al. The comprehensive complication index for advanced monitoring of complications following endoscopic surgery of the lower urinary tract. J Endourol 2021;35(4):490–496. doi:10.1089/end.2020.0825. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Tzelves L, Geraghty R, Mourmouris P et al. Shockwave lithotripsy complications according to modified clavien-dindo grading system. A systematic review and meta-regression analysis in a sample of 115 randomized controlled trials. Eur Urol Focus 2022;8(5):1452–1460. doi:10.1016/j.euf.2021.11.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Somani BK, Giusti G, Sun Y et al. Complications associated with ureterorenoscopy (URS) related to treatment of urolithiasis: the Clinical Research Office of Endourological Society URS Global study. World J Urol 2017;35(4):675–681. doi:10.1007/s00345-016-1909-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Grosso AA, Sessa F, Campi R et al. Intraoperative and postoperative surgical complications after ureteroscopy, retrograde intrarenal surgery, and percutaneous nephrolithotomy: a systematic review. Minerva Urol Nephrol 2021;73(3):309–332. doi:10.23736/s2724-6051.21.04294-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Yamaguchi A, Skolarikos A, Buchholz NP et al. Operating times and bleeding complications in percutaneous nephrolithotomy: a comparison of tract dilation methods in 5,537 patients in the clinical research office of the endourological society percutaneous nephrolithotomy global study. J Endourol 2011;25(6):933–939. doi:10.1089/end.2010.0606. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Sugihara T, Yasunaga H, Horiguchi H et al. Longer operative time is associated with higher risk of severe complications after percutaneous nephrolithotomy: analysis of 1511 cases from a Japanese nationwide database. Int J Urol 2013;20(12):1193–1198. doi:10.1111/iju.12157. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Lane J, Whitehurst L, Hameed BMZ, Tokas T, Somani BK. Correlation of operative time with outcomes of ureteroscopy and stone treatment: a systematic review of literature. Curr Urol Rep 2020;21(4):17. doi:10.1007/s11934-020-0970-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Bhanot R, Pietropaolo A, Tokas T et al. Predictors and strategies to avoid mortality following ureteroscopy for stone disease: a systematic review from European Association of Urologists Sections of Urolithiasis (EULIS) and Uro-technology (ESUT). Eur Urol Focus 2022;8(2):598–607. doi:10.1016/j.euf.2021.02.014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Dupuis H, Khene ZE, Surlemont L et al. Preoperative risk factors for complications after flexible and rigid ureteroscopy for stone disease: a French multicentric study. Prog Urol 2022;32(8–9):593–600. doi:10.1016/j.purol.2022.02.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Knipper S, Tiburtius C, Gross AJ, Netsch C. Is prolonged operation time a predictor for the occurrence of complications in ureteroscopy? Urol Int 2015;95(1):33–37. doi:10.1159/000367811. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Pareek G, Hedican SP, Lee FTJr., Nakada SY. Shock wave lithotripsy success determined by skin-to-stone distance on computed tomography. Urology 2005;66(5):941–944. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2005.05.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Delakas D, Karyotis I, Daskalopoulos G, Lianos E, Mavromanolakis E. Independent predictors of failure of shockwave lithotripsy for ureteral stones employing a second-generation lithotripter. J Endourol 2003;17(4):201–205. doi:10.1089/089277903765444302. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Danilovic A, Perrone G, Dias L et al. Is it worth using the Comprehensive Complication Index over the Clavien-Dindo classification in elderly patients who underwent percutaneous nephrolithotomy? World J Urol 2024;42(1):599. doi:10.1007/s00345-024-05318-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Haberal HB, Anlar T, Celik F et al. Exploring the competency of the comprehensive complication index over the clavien-dindo classification in standard percutaneous nephrolithotomy: a call for better complication reporting. World J Urol 2024;42(1):537. doi:10.1007/s00345-024-05236-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools