Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Spermatocelectomy with and without epididymectomy: retrospective experience at a single institution in patients not interested in fertility preservation

Department of Urology, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT 06510, USA

* Corresponding Author: Stanton C. Honig. Email:

Canadian Journal of Urology 2025, 32(5), 521-527. https://doi.org/10.32604/cju.2025.064559

Received 19 February 2025; Accepted 29 May 2025; Issue published 30 October 2025

Abstract

Introduction: Spermatocelectomy is a surgical procedure performed for symptomatic spermatoceles. Published data is limited with respect to recurrence rates, complication rates, and patient satisfaction. The core concept of spermatocelectomy is to identify the communication between epididymis and spermatocele, which can be difficult and may result in spermatocele recurrence. We postulate that a combined spermatocelectomy with epididymectomy will yield a lower rate of recurrence. Methods: A retrospective chart review of patients with symptomatic spermatoceles undergoing spermatocelectomy with or without epididymectomy at our institution was performed. Patients were excluded from epididymectomy if they were interested in fertility preservation. Patient demographics, operative characteristics, and rates of recurrence and re-intervention were collected. Results: From 2013 to 2023, 70 patients underwent spermatocelectomy from a total of 14 surgeons, 35 (50%) of which underwent concurrent epididymectomy. A total of 10 (14.3%) patients experienced a recurrence and 5 (7.1%) patients required re-intervention with aspiration or re-excision over a median follow-up of 3.5 months. Patients who underwent spermatocelectomy alone were significantly more likely to experience recurrence (p = 0.006). Conclusion: Current data is lacking regarding recurrence rates after spermatocelectomy. Spermatocelectomy with epididymectomy resulted in a lower recurrence rate than spermatocelectomy alone. Removing the source of the communication between spermatocele and epididymis may result in a lower recurrence rate. A prospective, randomized trial is recommended to confirm these findings.Keywords

A spermatocele is a benign extratesticular, sperm-containing cystic structure attached to the epididymis. Originating from dilation of an efferent duct exiting the rete testis to the epididymis, it is thought to be caused by obstruction of the efferent duct.1 Patients typically present with a palpable cystic structure within the epididymis. While some spermatoceles may be asymptomatic, others may cause discomfort due to size. Research has found that men typically present with symptoms in the form of discomfort and sensation of mass when the spermatocele grows to the size of a normal testicle.2 Operative intervention in the form of spermatocelectomy is indicated in cases of symptomatic spermatoceles. During spermatocelectomy, the surgeon typically meticulously dissects the spermatocele off of the epididymis, isolates its stalk, and ligates and excises the spermatocele. Alternatively, aspiration or sclerotherapy may be offered. While these options are minimally invasive, they are typically not curative and have a very high rate of recurrence.3,4 Therefore, spermatocelectomy remains the standard approach.1

Recurrence of spermatocele even after surgical repair may occur. Identifying the plane between the spermatocele and epididymis can be challenging and inability to do so may result in spermatocele recurrence or risk epididymal injury. Published data on spermatocele recurrence is limited, but has been reported at between 5%–10%. In one study, after an mean follow up of 36 months, there was a 6% recurrence rate (n = 7/95).5 Some surgeons opt to use the operating microscope to better identify the spermatocele stalk, however this can increase operative time is not available to all surgeons.6–8 Furthermore, others may opt to remove the epididymis en bloc with the spermatocele at time of spermatocelectomy for patients not interested in preserving fertility.1

We aimed to compare spermatocele recurrence rates between spermatocelectomy with and without epididymectomy at our institution. We hypothesized that removing the epididymis at time of spermatocelectomy would be associated with lower recurrence rates, as it removes the source of the spermatocele.

We performed a retrospective chart review of patients over the age of 18 diagnosed with symptomatic spermatocele treated surgically with either spermatocelectomy or spermatocelectomy with epididymectomy at our institution from 2013 to 2023. We used Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) to collect and manage data.9,10 Relevant data collected included demographic information, ultrasound volume, prior treatments (i.e., aspiration, spermatocelectomy), procedure information (i.e., surgeon, year, type of procedure, operative time), recurrence, reoperation, other complications, and length of follow up. Patients were required to have at least one documented postoperative follow up appointment. Patients desiring future fertility were excluded from epididymectomy at time of spermatocelectomy. The primary outcome was spermatocele recurrence. Recurrence was defined as return of symptomatic spermatocele on the same side based on review of office notes. Secondary outcomes included reintervention/reoperation and other surgical complications. This study was approved by the Yale University Institutional Review Board (IRB) #2000036287. Informed consent exemption was obtained from the IRB given the retrospective nature of this study.

Epididymectomy operative technique

The surgical technique for the epididymectomy procedure was as follows: the epididymis was taken down from the head to below the area of the spermatocele (at least to the tail of the epididymis to as far as the convoluted vas deferens). The base of the rete testis was cauterized. Epididymal vessels were identified and tied off using 4-0 chromic sutures. The testis artery was spared in all cases. For cases in which the epididymal tail was left in situ, it was tied off with a 2-0 chromic suture. No sclerotherapy was utilized.

Descriptive statistics were performed for all patient and operative characteristics and were reported as median with interquartile ranges. The Chi-squared test was used for nonparametric categorical variables and Mann-Whitney U test was used for nonparametric continuous variables. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression was performed for risk of recurrence. Factors included in the initial model included: patient age, operative type, surgery type, prior procedure, size, and operative time. All factors that achieved p values < 0.2 on univariate analysis were carried forward into the multivariable model. p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analysis was performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software, version 29 (Armonk, NY, USA).

From 2013 to 2023, 70 patients underwent spermatocelectomy from a total of 14 surgeons, 35 (50%) of which underwent concurrent epididymectomy which was performed by a single surgeon. Spermatoceles were symptomatic for all patients. Table 1 shows patient and operative characteristics. 32 (45.7%) of patients had a pre-operative scrotal ultrasound, with a median spermatocele volume of 86.9 cm3. 26 (37.1%) patients received prior spermatocele treatment, either with aspiration (n = 24, 34.3%) or prior spermatocelectomy (n = 2, 2.9%). Six (8.6%) patients had history of vasectomy and 18 (25.7%) patients had history of inguinal hernia repair, with 16 of those repairs being ipsilateral to the side of the spermatocele. Cases were performed in the operating room under general anesthesia or local anesthesia with sedation. None were performed microsurgically. Two (2.9%) were bilateral spermatocele repairs. Concomitant surgeries included: ipsilateral varicocele repair (n = 1, 1.4%), ipsilateral hydrocele repair (n = 4, 5.7%), contralateral vasectomy (n = 2, 2.9%), robotic assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy (n = 1, 1.4%), circumcision (n = 1, 1.4%), and ipsilateral inguinal hernia repair (n = 1, 1.4%). In all cases of spermatocelectomy, pathology confirmed histopathological features consistent with spermatocele and no epididymal tissue was identified. In all cases of concurrent epididymectomy, pathology confirmed presence of the epididymis. All patients had at least one postoperative follow up appointment typically at four weeks post-procedure.

Over a median follow up of 3.5 months, 10 (14.3%) patients experienced a symptomatic recurrence of scrotal fluid collection and five (7.1%) patients underwent re-intervention with either aspiration (n = 4, 5.7%) or spermatocelectomy with epididymectomy (n = 1, 1.4%).

Table 2 shows a comparison of patients undergoing spermatocelectomy alone or spermatocelectomy with concurrent epididymectomy. There were no significant differences in age, ultrasound volume, operative time, or length of follow up between the two groups. Significantly more patients in the epididymectomy group (n = 20, 57.1%) had undergone prior spermatocele treatment compared to those in the spermatocelectomy group (n = 6, 17.1%) (p < 0.001). Those who underwent concurrent epididymectomy (n = 1, 2.9%) were significantly less likely to experience spermatocele recurrence compared to those who underwent spermatocelectomy alone (n = 9, 25.7%) (p = 0.006). In the spermatocelectomy group, three patients underwent re-aspiration and one patient underwent re-aspiration then spermatocelectomy with concurrent epididymectomy. In the epididymectomy group, one patient underwent re-aspiration of a fluid collection.

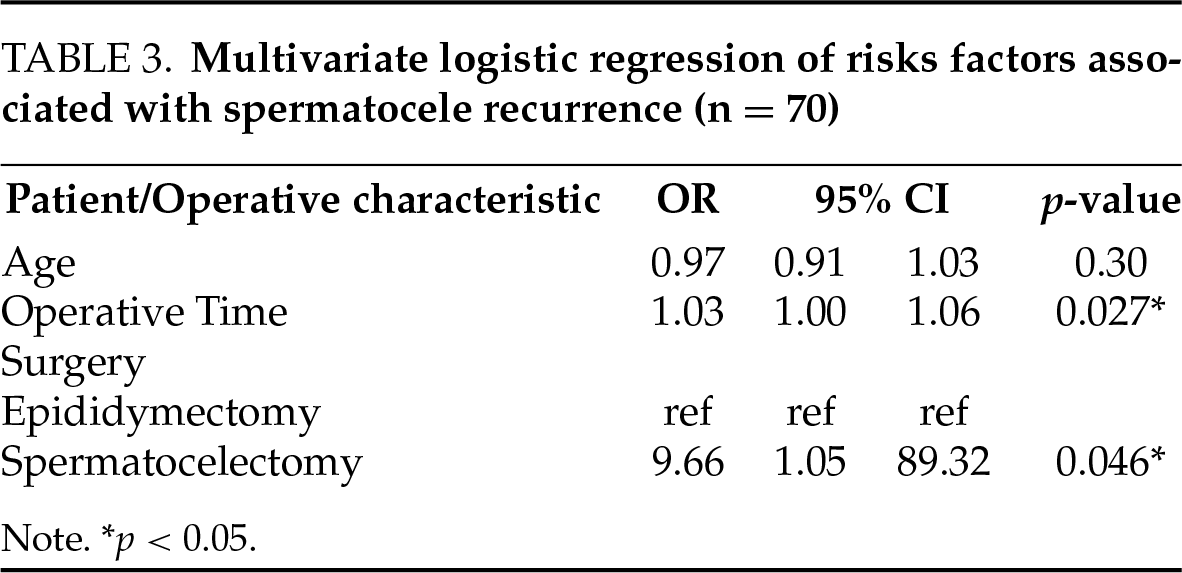

A multivariate logistic regression was performed to examine risk factors for spermatocele recurrence. Results are shown in Table 3. Spermatocelectomy alone (OR 9.6, 95% CI 1.0–89.3, p < 0.05) and longer operative time (OR 1.0, 95% CI 1.0–1.1, p < 0.05) were associated with spermatocele recurrence.

In terms of other complications, one patient in the spermatocelectomy with epididymectomy group had a post-operative abscess requiring incision and drainage. There were no post-operative hematomas in either group. There were no cases of testicular loss.

This retrospective, single center review showed a decreased risk of spermatocele recurrence after spermatocelectomy with concurrent epididymectomy compared to spermatocelectomy alone, with no difference in operative time. These findings suggest that epididymectomy can be considered in men with symptomatic spermatoceles and may lead to lower risk of recurrence.

While there is limited literature regarding spermatocele recurrence after spermatocelectomy, prior data suggests a recurrence rate between 5%–10%.5 There have been no further data published on this for over 18 years. In our analysis, 14.3% of patients experienced a recurrence. Nine of the 10 recurrences were in patients who underwent spermatocelectomy alone, suggesting that removal of the epididymis may reduce the risk of recurrence. Spermatocelectomy requires the surgeon to meticulously dissect the spermatocele off the epididymis until a single stalk is identified and ligated. We postulate that recurrence occurs when this stalk is not adequately dissected and residual spermatocele tissue is left behind. Recurrence may also occur due to weakening of the epididymal tubules adjacent to the prior spermatocele site. We did have one recurrence in the epididymectomy group. This was described as a fluid collection, which may have been a hematocele rather than a true spermatocele recurrence.

In our cohort, about 40% of patients underwent aspiration prior to surgery. In our practice, we offer aspiration for both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes. First, the character of the fluid can help determine whether the fluid is hydrocele or spermatocele in the case that an ultrasound is not available or is not definitive. Second, the patient can be offered temporary relief and can understand how he may feel after a surgical repair. Despite the possible benefits of aspiration, patients must be counseled that the recurrence rate is almost 100%.3

Both spermatocelectomy and epididymectomy are associated with postoperative complications. Data suggests an overall complication rate of about 20% in spermatocelectomy, with the typical complications being hematoma, infection, chronic pain, and recurrence of pathology.5,11–13 One important consideration when performing epididymectomy is preservation of the testicular artery. When dissecting the epididymis off the testicle, the common origin of the testicular and epididymal arteries is encountered, and only the epididymal artery is ligated. Inadvertent damage to the testicular artery has the potential to compromise the testicle. In our cohort, one patient in the epididymectomy group had a postoperative abscess requiring incision and drainage. There were no cases of testicular loss.

Epididymectomy should only be considered in men not desiring future fertility. Removal of the epididymis inherently creates obstruction to the flow of sperm. While in unilateral epididymectomy contralateral sperm transportation should be unaffected, bilateral epididymectomy can create permanent sterility akin to a vasectomy. Therefore, patients undergoing epididymectomy must be counseled on the implications of surgery on future fertility. Some physicians even delay any surgical repair of a spermatocele until patients no longer desire fertility given the risk of epididymal injury due to inadvertent resection, dissection, or use of electrocautery. One study found 17% of patients undergoing spermatocelectomy had inadvertent epididymal tissue in the pathology specimens.14 Studies have found risk of epididymal injury to be from 17% to greater than 50% of patients undergoing spermatocelectomy alone.14 Epididymal injury may lead to epididymal obstruction and compromised fertility. Due to this risk, some surgeons use the operating microscope in order to decrease the risk of epididymal injury.6,7,15 Therefore, even when performing spermatocelectomy alone, patients should be counseled regarding the risk of epididymal injury and compromised fertility. This was not a consideration in this study as all patients were not interested in fertlity.

Epididymectomy is most commonly performed for chronic scrotal pain typically with epididymal tenderness. 72%–93% of men with chronic epididymal pain have resolution or improvement in pain after epididymectomy.12,16,17 Several studies have found that patients with post-vasectomy pain in particular responded well to epididymectomy.16,18,19 In patients with spermatoceles, it can be difficult to assess whether the spermatocele itself is causing symptoms or the patient has concomitant epididymal tenderness. Our results on recurrence in combination with data on scrotal pain suggest that patients with epididymal tenderness may benefit most from epididymectomy at time of spermatocelectomy, especially when not desiring future fertility.

The present study has several limitations. First, this study had a small sample size and data was collected retrospectively at a single institution and was not randomized, limiting our ability to generalize the results of our analysis. Our two groups were therefore not able to be balanced, and significantly more patients in the epididymectomy group had undergone prior spermatocele aspiration compared to those in the spermatocelectomy group. Given its retrospective nature, length of follow up varied significantly from one month to more than 90 months in some patients, with a median of 3.5 months, which limits our ability to draw long term conclusions based on our data. We also relied on review of office and operative notes to determine spermatocele recurrence and reoperation. It is certainly possible that not all recurrences were captured if patients followed up elsewhere. Additionally, a single surgeon with a high volume spermatocele practice performed all of the epididymectomies in our sample, introducing operator bias. The potential for variability in surgical technique may have impacted recurrence rates. In the future, larger, prospective randomized studies with longer follow up periods are needed to support our findings. We also were not able to evaluate the role of simple vs. multiloculated spermatoceles since not all patients had preoperative ultrasounds, which may also be a confounding variable. Notwithstanding these limitations, our study adds to the limited literature on optimal surgical treatment of spermatoceles.

Based on our analysis, patients undergoing spermatocelectomy with concurrent epididymectomy are less likely to experience spermatocele recurrence with no increase in operative time when compared to spermatocelectomy alone. Removing the source of the spermatocele may result in lower recurrence. Epididymectomy should be considered at time of spermatocelectomy for patients not desiring future fertility, and more research is needed to validate these findings.

Spermatocelectomy is used to surgically remove symptomatic spermatoceles. It can be challenging to identify the communication between the spermatocele and epididymis, and current data is limited regarding recurrence rates after spermatocelectomy. In this retrospective single center study, spermatocelectomy with concurrent epididymectomy resulted in a lower recurrence rate than spermatocelectomy alone. Removing the source of the communication between spermatocele and epididymis may result in a lower recurrence rate. Ideally, larger, randomized studies are necessary to confirm these findings.

Acknowledgement

None.

Funding Statement

The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Stanton C. Honig, Ellen M. Cahill; data collection: Ellen M. Cahill; analysis and interpretation of results: Ankur U. Choksi, Ellen M. Cahill, Sharath S. Reddy, Stanton C. Honig; draft manuscript preparation: Ellen M. Cahill, Sharath S. Reddy, Katherine Rotker, Stanton C. Honig, Ankur U. Choksi, Dylan C. H. Heckscher. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author (Stanton C. Honig) upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval

This study was approved by the Yale University Institutional Review Board (IRB) #2000036287.

Informed Consent

Informed consent exemption was obtained from the IRB given the retrospective nature of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Rubenstein RA, Dogra VS, Seftel AD, Resnick MI. Benign intrascrotal lesions. J Urol 2004;171(5):1765–1772. doi:10.1097/01.ju.0000123083.98845.88. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Walsh TJ, Seeger KT, Turek PJ. Spermatoceles in adults: when does size matter? Arch Androl 2007;53(6):345–348. doi:10.1080/01485010701730690. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Beiko DT, Morales A. Percutaneous aspiration and sclerotherapy for treatment of spermatoceles. J Urol 2001;166(1):137–139. doi:10.1097/00005392-200107000-00032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Brockman S, Roadman D, Bajic P, Levine LA. Aspiration and sclerotherapy: a minimally invasive treatment for hydroceles and spermatoceles. Urology 2022;164:273–277. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2021.12.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Swartz MA, Morgan TM, Krieger JN. Complications of scrotal surgery for benign conditions. Urology 2007;69(4):616–619. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2007.01.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Kauffman EC, Kim HH, Tanrikut C, Goldstein M. Microsurgical spermatocelectomy: technique and outcomes of a novel surgical approach. J Urol 2011;185(1):238–242. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2010.09.017. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Hou Y, Zhang Y, Li G, Wang W, Li H. Microsurgical epididymal cystectomy does not impact upon sperm count, motility or morphology and is a safe and effective treatment for epididymal cystic lesions (ECLs) in young men with fertility requirements. Urology 2018;122:97–103. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2018.08.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Altay MS, Uslu Ö, Bedir F, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Microscopic single-tubule technique for spermatocelectomy in cases of spermatocele: a rarely used surgical method and ıts outcomes. Int Urol Nephrol 2025;57(9):2861–2866. doi:10.1007/s11255-025-04464-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42(2):377–381. doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL et al. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software partners. J Biomed Inform 2019 May 9;95:103208. doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Kiddoo DA, Wollin TA, Mador DR. A population based assessment of complications following outpatient hydrocelectomy and spermatocelectomy. J Urol 2004;171(2 Pt 1):746–748. doi:10.1097/01.ju.0000103636.61790.43. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Hicks N, Gupta S. Complications and risk factors in elective benign scrotal surgery. Scand J Urol 2016;50(6):468–471. doi:10.1080/21681805.2016.1204622. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Keller AK, Howard MM, Jensen JB. Complications after scrotal surgery—still a major issue? Scand J Urol 2021;55(5):404–407. doi:10.1080/21681805.2021.1884131. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Zahalsky MP, Berman AJ, Nagler HM. Evaluating the risk of epididymal injury during hydrocelectomy and spermatocelectomy. J Urol 2004;171(Pt 1):2291–2292. doi:10.1097/01.ju.0000125479.52487.b4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Zhao L, Yu Z, Zhang Z. Microscopic cyst resection for the treatment of patients diagnosed with epididymal cyst. J Vis Exp 2023;(193). doi:10.3791/64083. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Hori S, Sengupta A, Shukla CJ, Ingall E, McLoughlin J. Long-term outcome of epididymectomy for the management of chronic epididymal pain. J Urol 2009;182(4):1407–1412. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2009.06.020. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Siu W, Ohl DA, Schuster TG. Long-term follow-up after epididymectomy for chronic epididymal pain. Urology 2007;70(2):333–335. discussion 5–6. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2007.03.080. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Lee JY, Lee TY, Park HY et al. Efficacy of epididymectomy in treatment of chronic epididymal pain: a comparison of patients with and without a history of vasectomy. Urology 2011;77(1):177–182. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2010.05.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Cole RM, Andino JJ, Daignault-Newton S, Quallich SA, Hadj-Moussa M. Epididymectomy is an effective treatment for chronic epididymal pain. Urol Pract 2024;11(2):409–415. doi:10.1097/upj.0000000000000515. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools