Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Correlation between chronic prostate inflammation and overactive bladder symptoms following transurethral resection of the prostate due to benign prostate hyperplasia

1 Department of Urology, The Sahlgrenska Academy, The Institute of Clinical Sciences, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, 41345, Sweden

2 Department of Urology, Faculty of Medicine, Health Science University, Izmir, 35530, Turkey

3 Department of Pharmacology, Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, 41390, Sweden

* Corresponding Author: Ozgu Aydogdu. Email:

Canadian Journal of Urology 2025, 32(5), 529-538. https://doi.org/10.32604/cju.2025.064564

Received 19 February 2025; Accepted 09 June 2025; Issue published 30 October 2025

Abstract

Objectives: Treatment of patients with lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) is often challenging. In men, the origin of LUTS, in particular overactive bladder (OAB) symptoms, is often due to prostate enlargement. However, patients with chronic prostate inflammation (CPI) also frequently experience OAB. Thus far, it is not known if the inflammation per se or concomitant prostate enlargement is the underlying cause of LUTS. Currently, we aim to examine if there is any correlation between CPI and the persistence of OAB symptoms in patients with benign prostate hyperplasia (BPH). Methods: Fifty-one men underwent transurethral resection of the prostate (TUR-P). Based on pathological examination, the patients were divided into two groups, i.e., those with and without prostate inflammation. All patients were examinedwith the National Institutes of Health-Chronic Prostatitis Symptom Index (NIH-CPSI), international prostate symptom score (IPSS) and overactive bladder questionnaire validated-8 (OAB-V8) both pre-and post-operatively. Further, all patients were clinically examined through urine culture, prostate-specific antigen (PSA), uroflowmetry, postvoiding residual urine volume (PVR), and ultrasound of the prostate and bladder. Results: None of the clinical examinations showed significant differences between the two groups. By questionnaire analysis, both groups showed similar significantly improved NIH-CPSI and IPSS scores after TUR-P. However, OAB symptoms were only significantly improved in patients without CPI. Conclusions: Even though TUR-P improves many of the LUT symptoms in patients with BPH, OAB symptoms with concomitant CPI are more challenging to manage. Identifying concomitant CPI in men with BPH can potentially help to guide post-operative decision-making following TUR-P.Keywords

The men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS) need better management. The prevalence of CP/CPPS is approximately 8%.1 A large percentage of affected patients have symptoms that can be traced to the bladder, usually overactive bladder (OAB). Several studies have shown that CP/CPPS leads to a greatly reduced quality of life.2 The management of patients with CP/CPPS is quite challenging.

Although CP is a clinical diagnosis, it is pathologically characterized by the chronic inflammation of the prostate. Several clinical reports have shown OAB symptoms associated with chronic prostate inflammation (CPI).1–3 Similar findings were seen in animal experimental studies.4,5 Although there are theories about how this co-morbidity arises, the exact mechanism is still unknown. An important concept to define is cross-organ sensitization. The changes that occur during chronic inflammation, including altered levels of inflammatory mediators, activation of sensory nerves, and altered levels of several signaling molecules, can all be contributing causes of cross-organ sensitization. Recent studies revealed that chronic inflammation in the prostate can negatively affect the bladder function.4,6

In men with benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), urination difficulties are typically attributed to an enlarged prostate and narrowing of the urethra.7 The narrowing of the urethra occurs because of prostate growth and leads to patients experiencing both urgency and inadequate bladder emptying. However, patients with CPI do not always suffer from simultaneous prostate enlargement. Nevertheless, they suffer from micturition problems. Thus, micturition problems can occur for reasons other than prostate enlargement or urethral narrowing.

Bladder outlet obstruction (BOO) due to BPH causes compensatory detrusor muscle hypertrophy, altered detrusor function, progressive bladder dysfunction, and bladder oversensitivity. These changes in the bladder due to BOO can lead to OAB symptoms as well as urinary urgency and urge urinary incontinence (UUI) over time.8,9 Recent research has also investigated the potential associations between OAB symptoms and conditions other than BPH/BOO including obesity, diabetes mellitus (DM), metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular diseases, neurological disorders, and physical inactivity.10,11 However, the exact impact of inflammation of the prostate is still not fully detailed.

This study has aimed to investigate if there is any correlation between prostate inflammation and the persistence of OAB symptoms following transurethral resection of the prostate (TUR-P) due to BPH. Besides blood and urine tests, all patients were preoperatively examined with the international prostate symptom score (IPSS), NIH-Chronic Prostatitis Symptom Index (NIH-CPSI), and overactive bladder questionnaire validated-8 (OAB-V8). The patients were categorized into two groups based on the pathological findings of the resected prostate tissue: those without CP (Gr1) and those with CP (Gr2). All patients completed the same questionnaires at both the 6th week and 6th month after surgery. Based on these forms and the pathological results, we could classify each patient as having or not having CPI and having or not having OAB symptoms.

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Faculty of Medicine, Health Science University, Izmir, Turkey (#2021/172). Fifty-one men who underwent TUR-P due to BPH and LUT symptoms (LUTS) were included. Based on an estimated effect size of 0.5, indicating a moderate to large difference between the groups, the power calculations revealed a power of 0.8 (α = 0.05, β = 0.2) for a sample size of 21 patients in each group. The patients were informed about the possible complications and about how data from examinations, sampling and questionnaires would be handled. Informed consent form was obtained from all patients.

Before surgery, all patients were assessed using NIH-CPSI, IPSS, and OAB-V8. In addition, preoperative evaluations included urine culture, prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing, uroflowmetry, measurement of postvoid residual urine volume (PVR), and ultrasound imaging of the prostate and bladder. Only patients with a negative urine culture were included in the study Hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) staining was performed on the resected prostate tissues and analyzed in a blinded manner to detect CPI. Based on the pathological findings, patients were classified into two groups: those without CP (Gr1) and those with CP (Gr2). Patients who had chronic urinary catheters or were undergoing intermittent catheterization before the surgery were excluded from the study, as were those diagnosed with prostate or bladder cancer. All included patients were evaluated using questionnaires at both the 6th week and 6th month following surgery.

The two groups were statistically compared based on demographic characteristics, questionnaire scores, ultrasound findings, and all other test results. Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism version 10.2.1 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). An unpaired t-test was used to compare demographic data, blood test results, uroflowmetry findings, and both preoperative and postoperative scores from the NIH-CPSI, IPSS, and OAB-V8 questionnaires between the two groups. For questionnaire data assessed at three time points—preoperatively, postoperative 6th week, and postoperative 6th month—statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc correction and two-way ANOVA for multiple comparisons. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM.

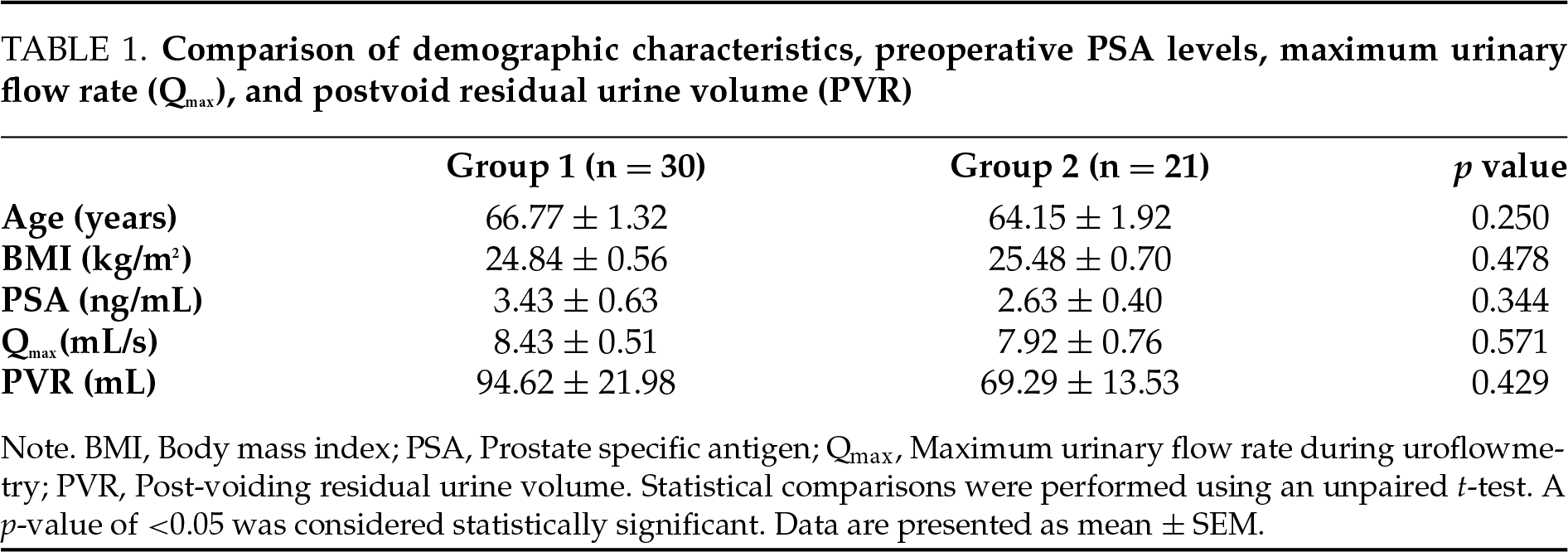

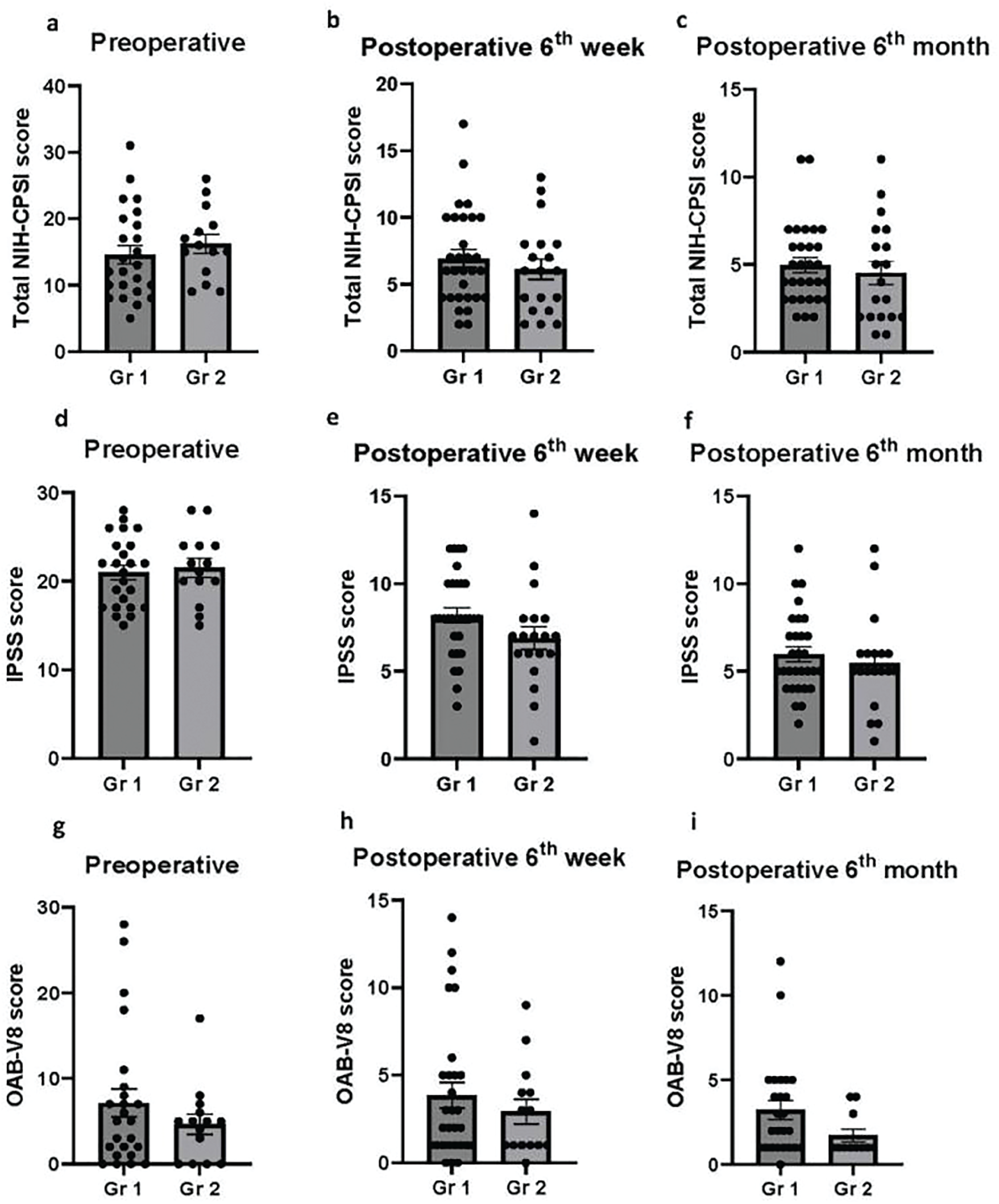

Pathological examination of the resected prostate tissue following TUR-P revealed no signs of CPI in 30 patients (Gr1), while 21 patients (Gr2) were diagnosed with CPI. There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups in demographic characteristics, preoperative PSA levels, maximum urinary flow rate (Qmax), or postvoid residual urine volume (PVR) (Table 1). Additionally, no significant differences were observed between the groups in preoperative or postoperative scores from the NIH-CPSI, IPSS, or OAB-V8 (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1. Comparison of pre- and postoperative NIH-CPSI, IPSS and OAB-V8 scores. No significant differences were observed between the two groups in either preoperative or postoperative scores for (a–c) NIH-CPSI, (d–f) IPSS, or (g–i) OAB-V8. Gr 1: Patients without chronic prostate inflammation; Gr 2: Patients with chronic prostate inflammation. NIH-CPSI: NIH Chronic Prostatitis Symptom Index; IPSS: International Prostate Symptom Score; OAB-V8: Overactive bladder questionnaire validated-8. Statistical comparisons were conducted using an unpaired t-test. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data are presented as mean ± SEM

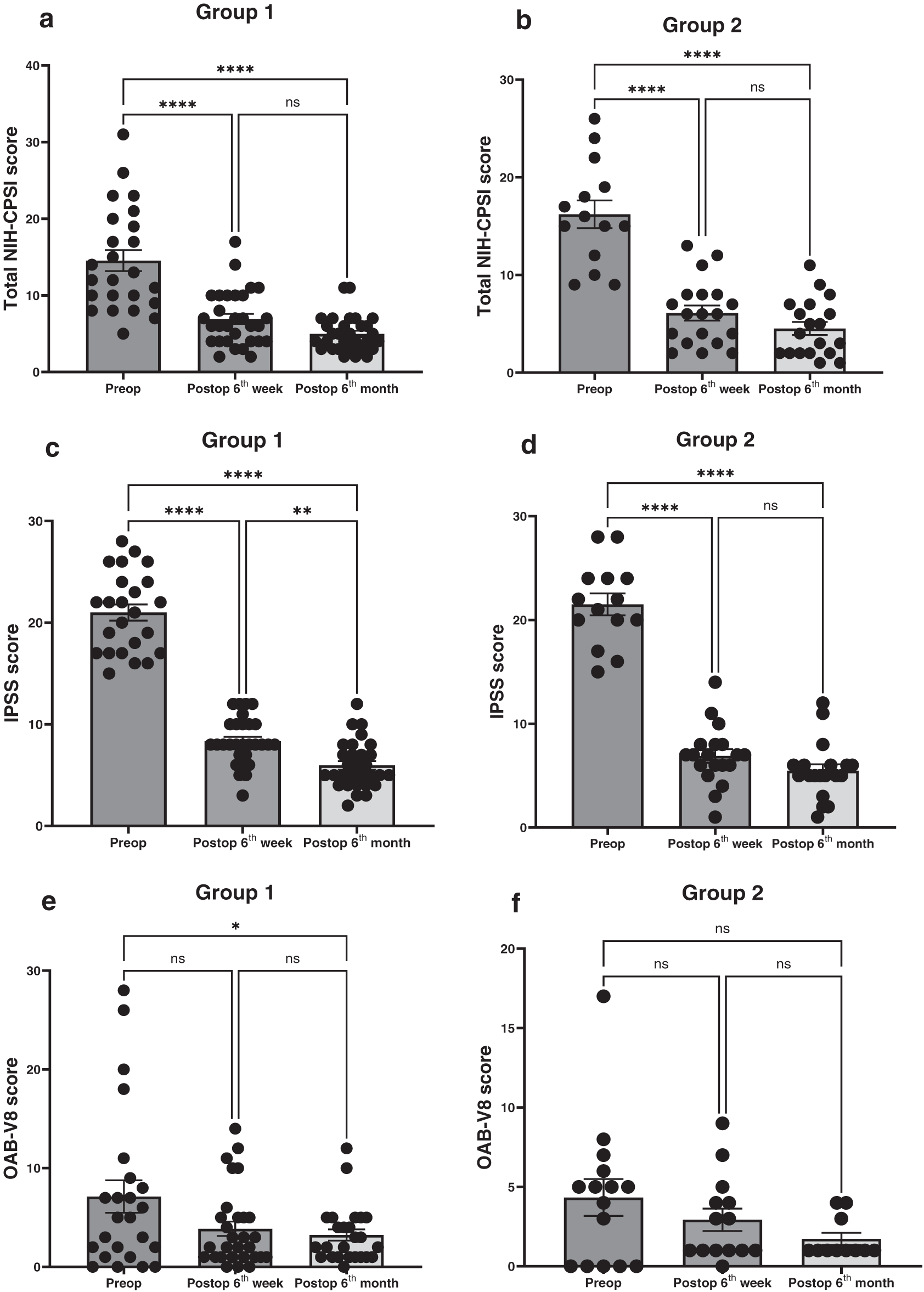

Postoperative total NIH-CPSI scores were significantly reduced at both the 6th postoperative week and the 6th month as compared to preoperative total NIH-CPSI scores in patients without CPI (Gr1). Although a gradual decrease in total NIH-CPSI scores was observed over time postoperatively, there was no significant difference between the postoperative 6th week and 6th month (preoperative total NIH-CPSI score: 14.54 ± 1.38, postoperative 6th week: 6.93 ± 0.65, postoperative 6th month: 4.97 ± 0.42; preoperative vs. postoperative 6th week, p < 0.0001; preoperative vs. postoperative 6th month, p < 0.0001; postoperative 6th week vs. postoperative 6th month, p = 0.20; Figure 2a). Similarly, total NIH-CPSI scores were significantly reduced in patients with CPI (Gr2) at both postoperative 6th week and 6th month as compared to preoperative total NIH-CPSI scores. In addition, a gradual decrease in total NIH-CPSI scores was observed over time following the TUR-P operation. However, this decrease was not statistically significant. (preoperative total NIH-CPSI score: 16.21 ± 1.42, postoperative 6th week: 6.11 ± 0.77, postoperative 6th month: 4.53 ± 0.67; preoperative vs. postoperative 6th week, p < 0.0001; preoperative vs. postoperative 6th month, p < 0.0001; postoperative 6th week vs. postoperative 6th month, p = 0.419; Figure 2b). Likewise, IPSS scores were significantly decreased postoperatively in both groups (Gr1 preoperative IPSS: 21.00 ± 0.80, postoperative 6th week: 8.35 ± 0.43, postoperative 6th month: 4.53 ± 0.67; Gr2: preoperative IPSS: 21.50 ± 1.06, postoperative 6th week: 6.90 ± 0.65, postoperative 6th month: 5.47 ± 0.62; preoperative vs. postoperative 6th week, p < 0.0001 in both groups; preoperative vs. postoperative 6th month, p < 0.0001 in both groups; Figure 2c,d). Although there was a significant difference between the postoperative 6th week and 6th month in Gr1, this difference was not statistically significant in Gr2 (Gr1: postoperative 6th week vs. postoperative 6th month, p = 0.0057; Gr2: postoperative 6th week vs. postoperative 6th month, p = 0.351; Figure 2c,d). While OAB-V8 scores were decreased both at the postoperative 6th week and 6th month, the only statistically significant difference was between the postoperative 6th month and preoperative OAB-V8 score in Gr1 (preoperative OAB-V8: 7.13 ± 1.65, postoperative 6th week: 3.86 ± 0.73, postoperative 6th month: 3.24 ± 0.57; preoperative vs. postoperative 6th week, p = 0.075; preoperative vs. postoperative 6th month, p = 0.034; postoperative 6th week vs. postoperative 6th month, p = 0.904; Figure 2e). Likewise, a gradual decrease was observed in OAB-V8 scores after TUR-P in Gr2. However, this difference was not statistically significant either at the postoperative 6th week or 6th month when compared to the preoperative OAB-V8 score (preoperative OAB-V8: 4.33 ± 1.16, postoperative 6th week: 2.93 ± 0.71, postoperative 6th month: 1.73 ± 0.38; preoperative vs. postoperative 6th week, p = 0.480; preoperative vs. postoperative 6th month, p = 0.120; postoperative 6th week vs. postoperative 6th month, p = 0.631; Figure 2f).

FIGURE 2. The difference in NIH-CPSI, IPSS and OAB-V8 scores before and after TUR-P in both groups. Gr1: Patients without chronic prostate inflammation (Figure 2a,c,e); Gr2: Patients with chronic prostate inflammation (Figure 2b,d,f). NIH-CPSI: NIH Chronic Prostatitis Symptom Index; IPSS: International Prostate Symptom Score; OAB-V8: Overactive bladder questionnaire validated-8. Statistical comparisons were performed using one-way ANOVA. Significance levels are indicated as follows: ns (not significant), *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ****p < 0.0001. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data are presented as mean ± SEM

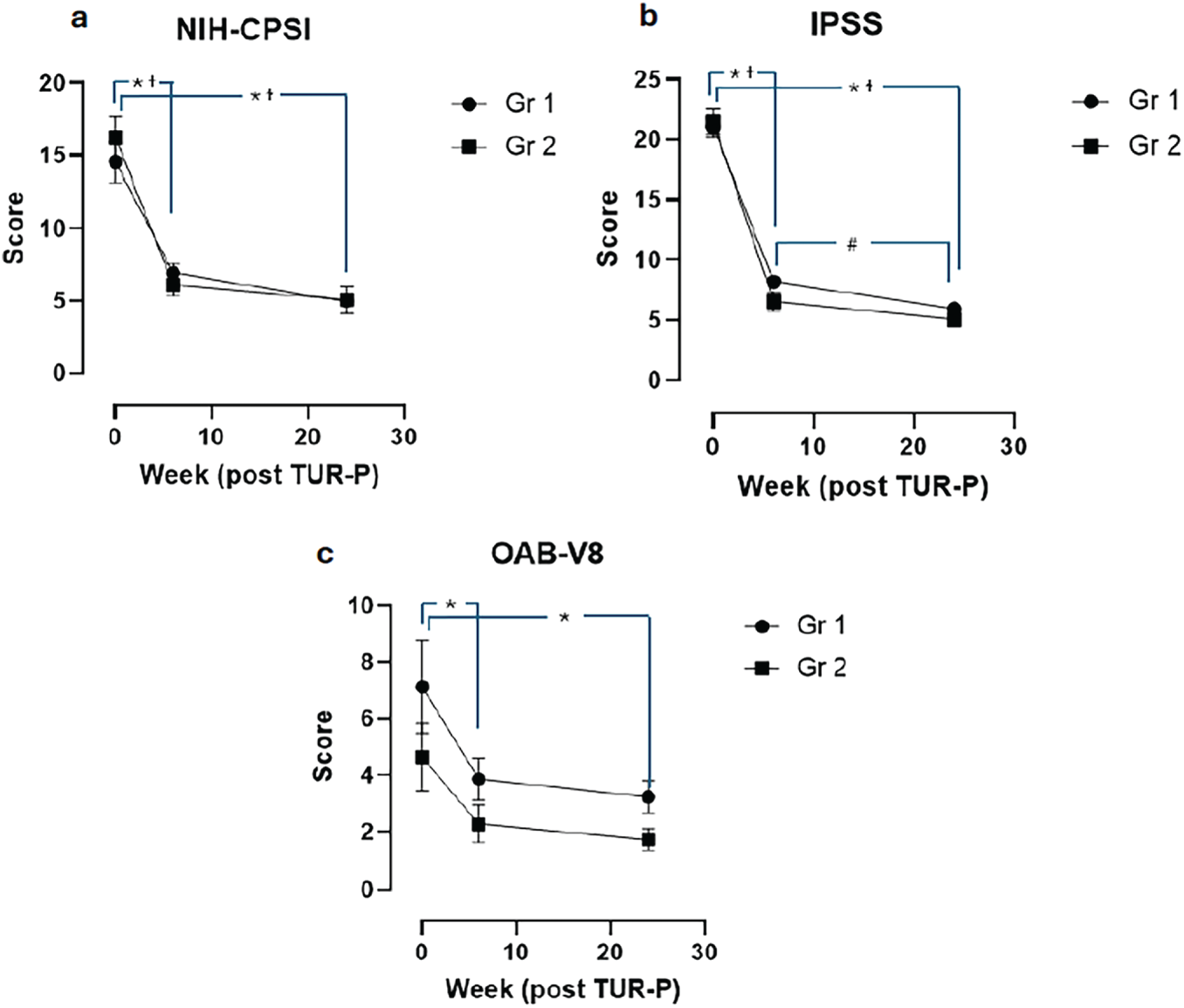

Further, we tried to consolidate the patient-reported outcome data (NIH-CPSI, IPSS, OAB-V8) into more intuitive longitudinal visualizations showing both groups and comparing them directly over time (Figure 3). Similarly, both IPSS and NIH-CPSI scores were significantly improved postoperatively in both groups. Although a significant improvement was observed in OAB-V8 scores postoperatively in Group 1, no significant change was observed in Group 2.

FIGURE 3. Comparison of total NIH-CPSI (a), IPSS (b) and OAB-V8 (c) in two groups over time. Gr 1: Patients without chronic prostate inflammation; Gr 2: Patients with chronic prostate inflammation. NIH-CPSI: NIH Chronic Prostatitis Symptom Index; IPSS: International Prostate Symptom Score; OAB-V8: Overactive bladder questionnaire validated-8. A two-way ANOVA test was used for statistical comparisons. *p < 0.05; #p < 0.05; †p < 0.05. Statistical significance was regarded as p < 0.05. The data are presented as mean ± SEM. *Gr 1; p > 0.0001; #Gr 1; 6 weeks vs. 6 months; p = 0.0133; †Gr 2; p > 0.0001

In this study, the primary objective was to investigate the potential correlation between CPI and the persistence of OAB symptoms in men who underwent TUR-P for BPH. Alongside routine clinical examinations and blood/urine tests, all patients were evaluated both preoperatively and postoperatively using the NIH-CPSI, IPSS, and OAB-V8 questionnaires. Notably, the IPSS is a well-established tool for assessing the severity of LUTS.12,13 NIH-CPSI is used for the clinical diagnosis of CP and guides clinicians to evaluate symptom severity in men with CP.14 To be noted, CP is a clinical diagnosis and mainly relies on symptoms. Histological confirmation is not a routine part of clinical investigation. However, it has previously been suggested that the NIH-CPSI is correlated with the severity of CPI in patients with BPH.15 OAB-V8 is a reliable tool to assess both the severity of symptoms related to OAB and treatment effectiveness.16,17 In the current study, since it was not possible to perform urodynamic studies in all patients with BPH, the OAB-V8 questionnaire was used to assess the possible correlation between CPI and OAB symptoms as well as the potential effects of TUR-P on bladder function. The main reason that BPH patients who underwent TUR-P were included in the present study, was to have a histological confirmation of possible CPI and to investigate if there is a correlation between histological inflammation and NIH-CPSI scores. The only way to prove the existence of inflammatory cells in the prostate is by histological examination.18

In a previous study, CPI was found in 30% of surgically derived BPH specimens.19 The inflammation was associated with age. However, in the present study, there was no difference in age between the patients with and without CPI. In another study, CPI was observed in 40% of prostate biopsy specimens, in older patients.20 It has also been demonstrated that CPI is present in over 50% of men undergoing TUR-P.13,21 The histopathological results of the present study revealed that 41% of patients had CPI, consistent with previous research indicating a high prevalence of concomitant CPI in BPH patients.12

Chronic inflammation of the prostate accompanied by OAB symptoms is frequently misdiagnosed solely as chronic prostatitis (CP). This misdiagnosis may contribute to the unsatisfactory treatment outcomes for many patients with CPI, as men with both CPI and OAB are often managed as if they have only CP.1 No correlation between CPI and OAB was observed in this study. Instead, the findings indicated that TUR-P effectively alleviated LUTS regardless of the presence of CPI. However, the data also showed that common bladder function abnormalities, most notably OAB, were not effectively treated by TUR-P alone. It should be noted that the postoperative follow-up period in this study was limited to 6 months, and the long-term effects of TUR-P on bladder function warrant further investigation in future studies.

Previous studies have indicated that elevated IPSS scores and PSA levels may be indicative of CPI in patients with BPH.13,22,23 Furthermore, the NIH-CPSI is sometimes utilized to identify patients with concomitant CPI.14 Nonetheless, our results demonstrated no statistically significant differences between the two groups in PSA levels, IPSS, or NIH-CPSI scores. The discrepancy between the current study and previous studies could be due to different inclusion criteria such as patients with older age and higher IPSS in previous studies as well as different timing of evaluation with questionnaires. In addition, some CP patients without inflammatory symptoms can still be bothered by CPI, which makes the diagnosis that mainly relies on clinical symptoms and questionnaires even more challenging.14 The findings of the current study further show how difficult it is to identify possible concomitant CPI in BPH patients and why an effective treatment alternative is yet to be found. Tentatively, a higher degree of inflammation could lead to higher PSA levels and higher scores from NIH-CPSI and IPSS. In addition, previous studies showed that the efficacy of medical treatments with 5α-reductase inhibitors and α-blockers was poorer in CP patients with higher grades of CPI than the patients with lower grades of inflammation.24 In the current study, a possible correlation between CPI and persistent OAB symptoms after TUR-P was investigated. The criteria used to classify the patients were the presence or absence of CPI in resected prostate tissues, which was blindly analyzed. However, as a potential limitation, histological grading of CPI was not performed in this study. Histopathological images and grading of inflammation in the prostate would improve the findings of the current study. Future studies investigating the potential effect of the degree of prostate inflammation on IPSS, NIH-CPSI, and PSA levels would be beneficiary. Previous studies showed quality of life (QoL) and pain sub-scores in NIH-CPSI as important indicators of CPI.25,26 However, sub-score analyses including pain or QoL were not performed in the current study, which should be examined in future studies. Although there was a significant improvement postoperatively in Gr1, preoperative OAB-V8 scores were low in both groups (<8 at baseline) and the improvement seemed to be modest postoperatively suggesting a possible floor effect. However, some patients might have a low OAB-V8 score although they experienced classic OAB symptoms. Especially in men with BPH, LUTS can overlap with OAB leading to a symptom profile that may not fit into a high OAB-V8 score. In addition, the postoperative follow-up period was only 6 months, and the possible progression of BPH in patients with CPI in the long term was not investigated in the current study. Long-term postoperative follow-up of patients could potentially show differences between the patients with and without CPI regarding IPSS and NIH-CPSI scores. It is usually not possible to perform a histological examination of all resected prostate tissues after TUR-P. This means that inflammation could be present in the prostate but missed by the pathological examination in some patients. Lastly, the resected prostate tissues were not investigated microbiologically for possible bacterial prostatitis. However, all patients were investigated preoperatively with urine culture and only the men with negative urine culture were included in the study. Although these limitations might have some influence on the interpretation of current findings, we believe that the present study has the potential to further guide clinicians in the management of patients with CPI.

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to suggest that concomitant CPI may serve as a significant predictor of poor postoperative outcomes following TUR-P, particularly in relation to bladder function. Therefore, to ensure effective management of patients with BPH, it is crucial to identify those with potential concomitant CPI. Histological examination of prostate tissue remains the only reliable method for diagnosing CPI. However, histological examination is not feasible for all BPH patients due to its invasive nature. Although the small sample size limits the generalizability of our conclusions, these findings underscore the need for more reliable, non-invasive methods to identify CPI in BPH patients who are at increased risk of suboptimal treatment outcomes. Although being an invasive method, it can be worth undertaking pressure-flow studies to examine possible changes in bladder function before deciding on TUR-P, especially in patients who are strongly suspected of having CPI. We believe that it is necessary to identify the presence of potential OAB due to concomitant CPI to improve the management of BPH patients who undergo TUR-P.

Transurethral resection of the prostate is an effective treatment for alleviating most LUTS associated with BPH, irrespective of the presence of CPI. It could be challenging to identify and manage OAB symptoms, particularly in men with BPH. Subsequent studies with a more prolonged follow-up period are required to examine changes in bladder function after TUR-P. Therefore, the identification of concomitant CPI in men with BPH may play a crucial role in guiding postoperative management and therapeutic decisions following TUR-P. To facilitate this, the development and implementation of more reliable, non-invasive diagnostic tools are required to accurately detect CPI in this patient population.

Acknowledgement

None.

Funding Statement

The current study was supported by grants from the Swedish Society for Medical Research (SSMF) and the Wilhelm and Martina Lundgren Foundation.

Author Contributions

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Ozgu Aydogdu, Onur Erdemoglu, Halil Ibrahim Bozkurt, Michael Winder; data collection: Onur Erdemoglu, Halil Ibrahim Bozkurt, Tansu Degirmenci; analysis and interpretation of results: Ozgu Aydogdu, Michael Winder; draft manuscript preparation: Ozgu Aydogdu, Michael Winder. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [Ozgu Aydogdu], upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval

The current study included human subjects. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Faculty of Medicine, Health Science University, Izmir, Turkey. The registration ID number is #2021/172. Informed consent form was obtained from all patients.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| LUTS | Lower urinary tract symptoms |

| OAB | Overactive bladder |

| CPI | Chronic prostate inflammation |

| PSA | Prostate-specific antigen |

| BPH | Benign prostate hyperplasia |

| TUR-P | Transurethral resection of the prostate |

| NIH-CPSI | National Institutes of Health-Chronic Prostatitis Symptom Index |

| IPSS | International Prostate Symptom Score |

| OAB-V8 | Overactive bladder questionnaire validated-8 |

| PVR | Postvoiding residual urine volume |

| CP/CPPS | Chronic prostatitis/Chronic pelvic pain syndrome |

| Qmax | Maximum urinary flow rate |

References

1. He W, Chen M, Zu X, Li Y, Ning K, Qi L. Chronic prostatitis presenting with dysfunctional voiding and effects of pelvic floor biofeedback treatment. BJU Int 2010;105(7):975–977. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08850.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Krieger JN, Nyberg LJr., Nickel JC. NIH consensus definition and classification of prostatitis. JAMA 1999;282(3):236–237. doi:10.1001/jama.282.3.236. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Suskind AM, Berry SH, Ewing BA, Elliott MN, Suttorp MJ, Clemens JQ. The prevalence and overlap of interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome and chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome in men: results of the RAND interstitial cystitis epidemiology male study. J Urol 2013;189(1):141–145. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2012.08.088. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Aydogdu O, Gocun PU, Aronsson P, Carlsson T, Winder M. Prostate-to-bladder cross-sensitization in a model of zymosan-induced chronic pelvic pain syndrome in rats. Prostate 2021;81(4):252–260. doi:10.1002/pros.24101. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Funahashi Y, Takahashi R, Mizoguchi S et al. Bladder overactivity and afferent hyperexcitability induced by prostate-to-bladder cross-sensitization in rats with prostatic inflammation. J Physiol 2019;597(7):2063–2078. doi:10.1113/JP277452. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Aydogdu O, Gocun PU, Aronsson P, Carlsson T, Winder M. Cross-organ sensitization between the prostate and bladder in an experimental rat model of lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced chronic pelvic pain syndrome. BMC Urol 2021;21(1):113. doi:10.1186/s12894-021-00882-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Langan RC. Men’s health: benign prostatic hyperplasia. FP Essent 2021;503:18–22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

8. Li R, Zhou Y, Xiao X, Li B. Recent advances in the diagnosis of bladder outlet obstruction in men. Bladder 2024;11(3):e21200017. doi:10.14440/bladder.2024.0022. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Verhovsky G, Baberashvili I, Rappaport YH et al. Bladder oversensitivity is associated with bladder outlet obstruction in men. J Pers Med 2022;12(10):1675. doi:10.3390/jpm12101675. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Kirby MG, Wagg A, Cardozo L et al. Overactive bladder: is there a link to the metabolic syndrome in men? Neurourol Urodyn 2010;29(8):1360–1364. doi:10.1002/nau.20892. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Wittert GA, Martin S, Sutherland P, Hall S, Kupelian V, Araujo A. Overactive bladder in men as a marker of cardiometabolic risk. Med J Aust 2012;197(7):379–380. doi:10.5694/mja11.11318. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Cao Q, Wu Y, Guan W, Zhu Y, Qi J, Xu D. Diagnosis of chronic prostatitis by noninvasive methods in elderly patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia in China. Andrologia 2021;53(6):e14055. doi:10.1111/and.14055. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Gandaglia G, Zaffuto E, Fossati N et al. The role of prostatic inflammation in the development and progression of benign and malignant diseases. Curr Opin Urol 2017;27(2):99–106. doi:10.1097/mou.0000000000000369. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Hiramatsu I, Tsujimura A, Soejima M et al. Tadalafil is sufficiently effective for severe chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Int J Urol 2020;27(1):53–57. doi:10.1111/iju.14122. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Mizuno T, Hiramatsu I, Aoki Y et al. Relation between histological prostatitis and lower urinary tract symptoms and erectile function. Prostate Int 2017;5(3):119–123. doi:10.1016/j.prnil.2017.04.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Trafford Crump R, Sehgal A, Wright I, Carlson K, Baverstock R. From prostate health to overactive bladder: developing a crosswalk for the IPSS to OAB-V8. Urology 2019;125:73–78. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2018.10.035. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Villacampa F, Ruiz MA, Errando C et al. Predicting self-perceived antimuscarinic therapy effectiveness on overactive bladder symptoms using the overactive bladder 8-question awareness tool. Int Urogynecol J 2013;24(4):573–581. doi:10.1007/s00192-012-1921-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. De Nunzio C, Salonia A, Gacci M, Ficarra V. Inflammation is a target of medical treatment for lower urinary tract symptoms associated with benign prostatic hyperplasia. World J Urol 2020;38(11):2771–2779. doi:10.1007/s00345-020-03106-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Di Silverio F, Gentile V, De Matteis A et al. Distribution of inflammation, pre-malignant lesions, incidental carcinoma in histologically confirmed benign prostatic hyperplasia: a retrospective analysis. Eur Urol 2003;43(2):164–175. doi:10.1016/s0302-2838(02)00548-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Torkko KC, Wilson RS, Smith EE, Kusek JW, van Bokhoven A, Lucia MS. Prostate biopsy markers of inflammation are associated with risk of clinical progression of benign prostatic hyperplasia: findings from the MTOPS study. J Urol 2015;194(2):454–461. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2015.03.103. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Nickel JC, Downey J, Young I, Boag S. Asymptomatic inflammation and/or infection in benign prostatic hyperplasia. BJU Int 1999;84(9):976–981. doi:10.1046/j.1464-410x.1999.00352.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Toktas G, Demiray M, Erkan E, Kocaaslan R, Yucetas U, Unluer SE. The effect of antibiotherapy on prostate-specific antigen levels and prostate biopsy results in patients with levels 2.5 to 10 ng/mL. J Endourol 2013;27(8):1061–1067. doi:10.1089/end.2013.0022. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Urkmez A, Yuksel OH, Uruc F et al. The effect of asymptomatic histological prostatitis on sexual function and lower urinary tract symptoms. Arch Esp Urol 2016;69(4):185–191. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

24. Kwon YK, Choe MS, Seo KW et al. The effect of intraprostatic chronic inflammation on benign prostatic hyperplasia treatment. Korean J Urol 2010;51(4):266–270. doi:10.4111/kju.2010.51.4.266. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Nickel JC, Downey J, Hunter D, Clark J. Prevalence of prostatitis-like symptoms in a population based study using the National Institutes of Health chronic prostatitis symptom index. J Urol 2001;165(3):842–845. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

26. Nickel JC, Roehrborn CG, O’Leary MP, Bostwick DG, Somerville MC, Rittmaster RS. Examination of the relationship between symptoms of prostatitis and histological inflammation: baseline data from the REDUCE chemoprevention trial. J Urol 2007;178(3):896–901. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2007.05.041. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools