Open Access

Open Access

COMMUNICATION

A prospective randomized trial comparing dusting and fragmentation techniques using Holmium:YAG laser for pediatric ureteral stones

1Division of Urology, School of Medicine, University of Aswan, Sahary City, 81528, Egypt

2 Division of Urology, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX 77555, USA

3 John Sealy School of Medicine, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX 77555, USA

* Corresponding Author: Suraj Nayan Vodnala. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Urolithiasis in Focus: Integrated Perspectives on Infection, Metabolic Dysfunction, and Contemporary Management)

Canadian Journal of Urology 2025, 32(5), 483-490. https://doi.org/10.32604/cju.2025.067228

Received 28 April 2025; Accepted 29 August 2025; Issue published 30 October 2025

Abstract

Background: As occurrence rates of pediatric ureteral stones have increased, evaluation of optimal treatment modalities has become imperative. This study’s primary goal is to compare outcomes between dusting and fragmentation techniques using Holmium:YAG (Ho:YAG) laser lithotripsy in children with ureteral stones. Methods: A prospective randomized study was conducted at Aswan University Hospitals from June 2023 to December 2024. One hundred children, under the age of 18, with single, mid- or distal, ureteral stones (5–20 mm) were randomized into two groups. Group A received laser dusting (0.2–0.6 J, 20–40 Hz), while Group B received fragmentation (0.8–1.5 J, 10–15 Hz), both using a 200-μm fiber. Stone-free rate (SFR), operative time, complications, and other outcomes were evaluated. Results: Demographics, laboratory parameters, stone size, and location were similar across groups. Group B had a significantly longer operative time but demonstrated a higher SFR (86% vs. 66%). Basket use was universal in the fragmentation Group (B) and was the only independent predictor of stone-free status (p = 0.035). Rates of complication, retreatment, and ureteral injury did not differ significantly between the two groups. Conclusions: While both techniques are safe and effective in pediatric ureteroscopic lithotripsy, fragmentation achieves a higher SFR at the cost of longer operative time and mandatory basket use. As the dusting setting offers shorter procedure times, both settings may be suitable for selected cases depending on clinical factors such as septic status.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileSeveral methods, such as ureteroscopic lithotripsy, extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL), or medical expulsive therapy, are widely available to urologists as management options for ureteral calculi.1–4 Historically, the usage of large ureteroscopes in children, made endoscopic stone management difficult for urologists.5 However, this is no longer the case with the development of small-diameter endoscopes, which are now the primary method for managing pediatric urolithiasis.6 The emergence of ureteroscopy in the pediatric population requires more investigative work that explores the optimization of many factors. Complexity increases with consideration of elements such as stone composition, size, and infection presence.

Through the direct visualization via ureteroscopy, ureteral stones may be broken up using a range of energy sources. Examples of such being the utilization of laser, electrohydraulic, ultrasound, and pneumatic techniques.1,2 Due to relatively low complications and reduced incidence of stone upward migration, the Ho:YAG laser has been used extensively as an energy source during URS in recent years.7 The laser medium in the system is a crystal composed of Yttrium Aluminum Garnet (YAG), doped with holmium ions. Diode lasers excite the holmium-doped crystal, releasing photons in pulses. This energy is transmitted through a flexible quartz optical fiber to fragment the stone.8 Pulse energy (PE) in joules and pulse frequency (PF) in hertz are multiplied to calculate the total power (watts, W) applied to the stone. The variability of PE and PF determines the lithotripsy setting that the Ho:YAG laser employs.9

The two settings often utilized in stone lithotripsy are ‘fragmentation’ and ‘dusting’. Dusting mode is defined by a low-energy (0.5 J) as well as a high-frequency laser setting (15–20 Hz). On the other hand, fragmentation mode uses a high-energy (1.5–2 J) in conjunction with a low-frequency setting (5 Hz). Both options result in the same amount of power (7.5–10 W).10

Although the dusting method requires less time to produce smaller fragments, it may be less effective for harder stones, such as cystine.11–13 Without fragments, analysis is difficult, an important step in the development of preventative plans.14 Studies suggest that the efficacy of dusting techniques can be influenced by the surgeon’s skill.9 For stones with compositions that require more force, the fragmentation technique works well. In simple cases, it allows for the extraction of entire stones, allowing for composition analysis. This ultimately works to provide potential etiologies important to prevention. The stone’s retropulsion from using high-energy settings and a longer operating time are some drawbacks.9 The energy, frequency, and pulse width parameters allow for the adjustment of power.

Although dusting mode may reduce the risk of ureteral damage, there is limited evidence to suggest that one technique is definitively superior to the other.8 Hence, the purpose of this study was to compare fragmentation and dusting settings as treatment methods for pediatric ureteral stones.

This prospective randomized trial was conducted at Aswan University Hospitals between June 2023 and December 2024. Ethical approval was obtained (IRB No. Asw.Uni. /821/7/23), and informed consent was obtained from all patients or their guardians. Individuals younger than or equal to 18 years old was how our study defined the pediatric population analyzed. In order to be included in the study, the patients had to have presented with a single ureteral stone located in the mid- or distal third of the ureter. These stones were required to be between 5–20 mm. Patients with stones larger or greater than this range were excluded from this study. Other exclusion criteria were patients with multiple ureteral stones, patients with stones in the upper third of the ureter, or patients with congenital anomalies of the urinary tract. Patient selection and randomization was modeled after a previous study which analyzed the efficacy of fragmentation in a similar pediatric population.15

All patients underwent standard preoperative evaluation; including urinalysis, urine culture, serum creatinine, blood urea nitrogen, complete blood count, and coagulation profile.16 This workup has previously been utilized in other papers analyzing fragmentation vs. dusting in the pediatric population15 Imaging used to analyze presence of stones included ultrasound and non-contrast CT. Patients were blindly randomized into either the fragmentation or the dusting group via sealed envelopes. Group A underwent dusting using low pulse energy (0.2–0.6 J) and high frequency (20–40 Hz), while Group B underwent fragmentation using higher pulse energy (0.8–1.5 J) and lower frequency (10–15 Hz).17 These respective settings for fragmentation and dusting have been used in previous trials concerning the pediatric population.15 A 200-μm laser fiber was used in all procedures. Basket retrieval was used as needed based on the surgeon’s discretion in the fragmentation group.

Techniques and endoscopic equipment

The techniques and endoscopic equipment utilized are provided below to assist with reproducibility and assessment of generalizability. The techniques and endoscopic equipment utilized were modeled after previous successful RCTs.15

• All ureteroscopic procedures were performed by the same team of surgeons. Under general or spinal anesthesia, the patient was placed in the lithotomy position.18 Routine prophylactic antibiotics were administered;19 and all procedures were recorded.

• Fluoroscopic monitoring was available for use in the operating room. All patients underwent initial cystoscopy to place a safety guidewire. After the guidewire was successfully advanced beyond the stone and into the proximal ureter or collecting system, ureteroscopy was performed with a 7.3F Storz semirigid ureteroscope (KARL STORZ, Tuttlingen, Germany). A safety wire was in place for all cases.

• A ureteroscope was introduced into the urethra. Ureterovesical junction (UVJ) dilatation was omitted in all cases.

• Ureteroscope passed the UVJ, with the assistance of a hydro-dilatation guided safety-wire. In addition, oscillated movements allowed for instrument tip rotation while keeping the ureter centered. The ureteroscope advanced through the ureter under the surgeon’s hand control. During the lithotripsy process, we used a Lumenis Pulse™ 120 Holmium YAG Laser System with MOSES™ Technology (Boston Scientific, MA, USA). Switching between the two lithotripsy settings (fragmentation and dusting) was performed by changing the laser settings: low energy (0.2–0.6 J) and high frequency (20–40 Hz) represented the dusting setting. High energy (mm–1.5 J) and reduced frequency (10–15 Hz) represented the fragmentation setting. The stones were fragmented or dusted until they could be removed with grasping instruments, or were deemed small enough to pass spontaneously. Follow-up imaging consisted of renal tract ultrasonography and plain abdominal film of the kidneys, ureters, and bladder.

• A stone-free status was conferred by the absence of any stone fragments on follow-up imaging at 4 to 6 weeks. The selected time-frame allowed for ureters to recover from any postoperative edema as a result of ureteroscopic manipulation or effects of fragmentation. This also as well as gave ample time for any fragments to clear spontaneously.20 A double-J stent was routinely placed in both groups. Fragmentation time, operating time, stone-free rate (SFR), and perioperative complications were compared.

Operative duration was defined as the initial insertion of the ureteroscope until completion of stent placement. Postoperative evaluation involved radiological assessment, either ultrasonography or non-contrast computed tomography (CT), conducted at 4 to 6 weeks post-intervention to determine if patients were stone-free. Of importance, both imaging modalities have significantly different sensitivities.21 Stone clearance was defined as the lack of stone fragments on radiography (CT scan with lack of stones < 3 mm or US with lack of visible stones/fragments). Radiology findings were required in conjunction with the resolution of pre-operative symptoms with no signs of re-occurrence in order for patients to be considered stone-free. All postoperative complications were classified in accordance with the Clavien-Dindo grading system.22 Specifically, in the dusting group, two patients experienced minor post-operative hemorrhages related to the procedure and were subsequently classified as Clavien-Dindo grade I. Likewise, the fragmentation group had one patient develop a minor postoperative hemorrhage, also graded as Clavien-Dindo grade I.

Sample size determination was conducted using G*Power statistical software (version 3.1.9.7 for Windows; Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf, Germany), targeting a statistical power of 85% and a Type I error rate (α) of 0.05, yielding a total sample of 100 patients evenly distributed between two study arms (n = 50 for each group). Data analysis was performed utilizing SPSS Statistics version 26 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).23 Continuous variables were compared using independent-sample t-tests, whereas categorical variables were assessed via the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Additionally, binary logistic regression analysis was employed to identify independent predictors of stone-free status. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered indicative of statistical significance. Previous studies have utilized G*Power statistical software for the targeted patient demographic.15

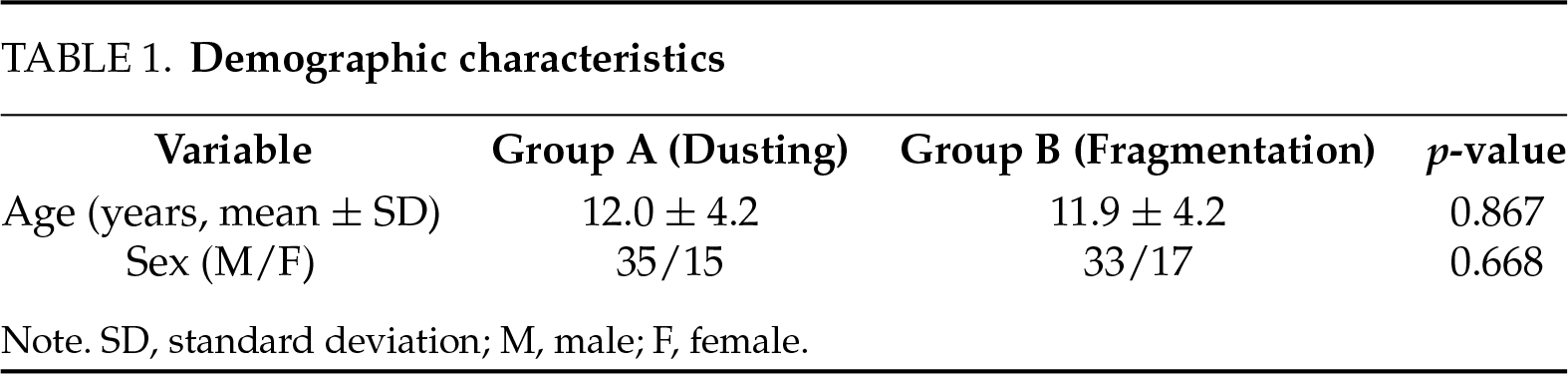

A total of 267 pediatric patients were screened during the study period, of whom 100 met the inclusion criteria and were randomized equally between the two groups. There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics/demographics between Group A (dusting) and Group B (fragmentation). The mean age of patients was 12.0 ± 4.2 years in Group A and 11.9 ± 4.2 years in Group B (p = 0.867). Gender distribution was also comparable, with no statistically significant differences noted (p = 0.668). Table 1 summarizes the demographic characteristics of both groups.

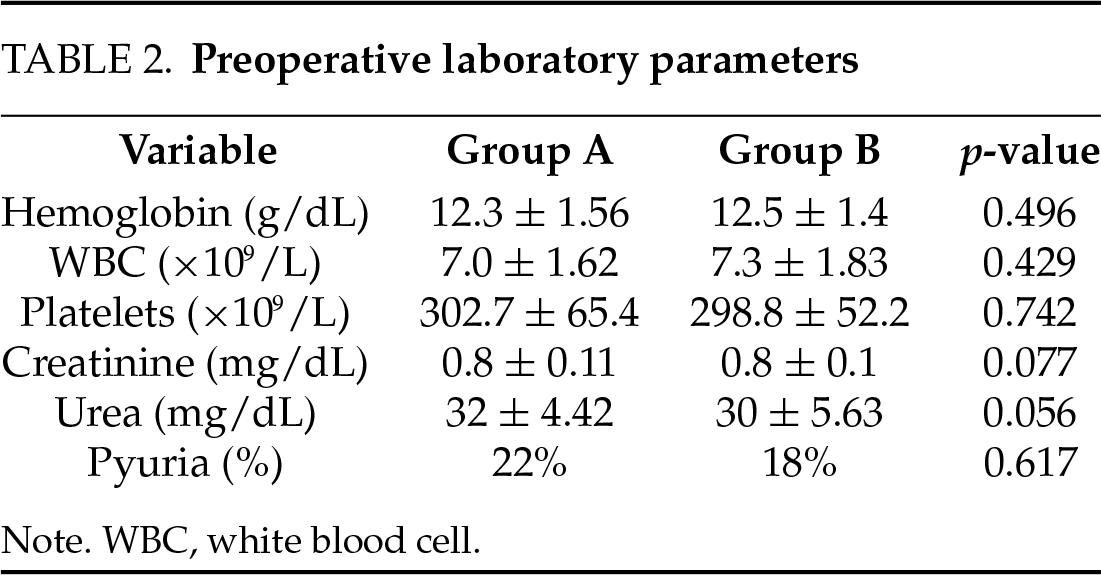

Preoperative laboratory parameters, including hemoglobin, white blood cell count, platelet count, serum creatinine, and blood urea nitrogen, showed no significant differences between the two groups. Pyuria was detected in 22% of patients in Group A and 18% in Group B. These findings are summarized in Table 2.

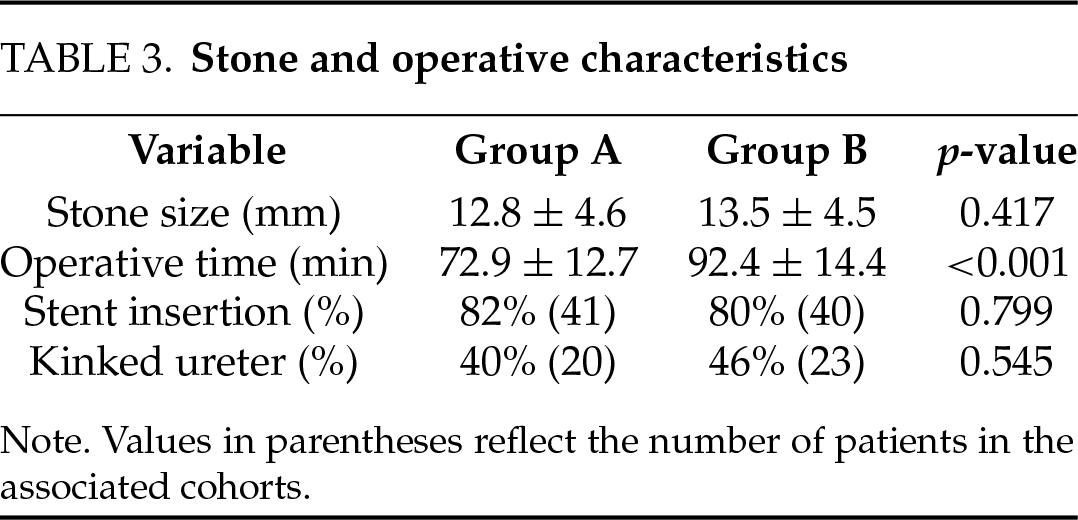

Regarding stone and operative characteristics, the average stone size was 12.8 ± 4.6 mm in Group A and 13.5 ± 4.5 mm in Group B (p = 0.417). Stone laterality and the presence of ureteral kinks were comparable across both groups. However, the mean operative time was significantly longer in Group B (92.4 ± 14.4 min) compared to Group A (72.9 ± 12.7 min, p < 0.001). Stent insertion was performed in 82% of Group A and 80% of Group B patients. Table 3 presents detailed operative data.

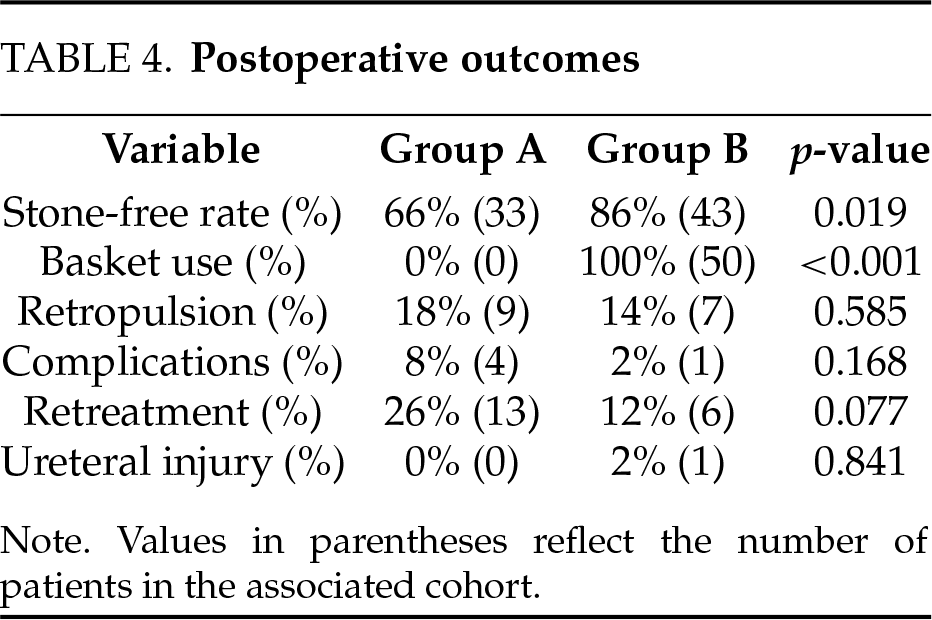

In terms of postoperative outcomes, the SFR was significantly higher in Group B (86%) than in Group A (66%), with a p-value of 0.019. Basket usage was universal in the fragmentation group and absent in the dusting group (p < 0.001). No significant differences were found in rates of retropulsion, postoperative complications, ureteral injury, or retreatment. Retreatment was defined as a second ureteroscopic lithotripsy session using the holmium:YAG laser dusting modality to address residual fragments. In the dusting group, 13 patients underwent retreatment with follow-up CT confirming a 100% SFR. These outcomes are summarized in Table 4.

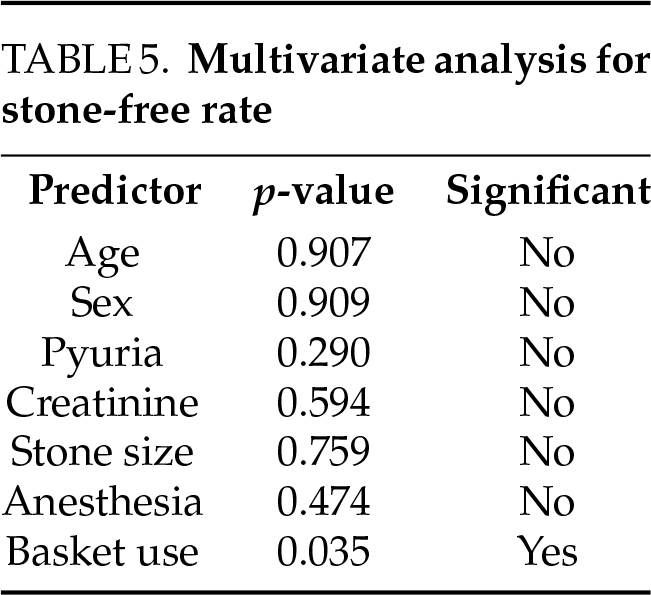

Multivariate logistic regression analysis identified basket use as the only statistically significant predictor of achieving a stone-free state (p = 0.035). Full results of this analysis are detailed in Table 5.

The Ho:YAG laser operates by converting energy from a holmium-doped crystal into pulses that are transmitted through optical fibers to disintegrate the stone.24 This study was conducted to compare dusting mode (low energy, high frequency) with fragmentation mode (high energy, low frequency) for the treatment of non-septic ureteral stones in children. In the current study, the dusting and fragmentation groups had comparable demographic profiles, with no significant differences in age or sex among the patient population, consistent with findings of Chen et al.8

The current study notes that there was no discernible difference between the two groups in terms of complicating factors such as the presence of pyuria (p = 0.617). Regarding kidney function, an important factor in the consideration of post-operative outcomes, the current study found no significant difference in creatinine or urea levels between the dusting and fragmentation groups. The considerations of kidney function are important and consistent with the study design performed in El-Nahas et al., who reported a non-significant difference in pre-operative kidney function between treatment modalities (mean creatinine level was 86.7 ± 9.1 µmol/L in the dusting group and 82.3 ± 18 µmol/L in the fragmentation group).25

The present investigation indicates that there was no significant difference between the two groups with respect to certain aspects of the operative data (anesthesia, ureteral stent insertion, etc.). However, certain measures of operative data did display statistically significant differences. For example, in contrast to group A (dusting), group B’s (fragmentation) operative time was noticeably longer. This finding contradicts Chen et al.,8 who discovered that operating time as well as efficacy did not differ statistically significantly between the two groups (all p > 0.05).

In this context, Gauhar et al.26 performed a meta-analysis of six studies, including 408 cases in the dusting group and 559 cases in the basketing group, revealing no significant difference in surgical time between the groups (MD = −5.39 min, 95% CI [−13.92–2.31], p = 0.16). Heterogeneity in the study was significant (I2.94%). Of note, the studies performed by Chen et al.8 and Gauhar et al.26 did not analyze the specific pediatric population that this current study has evaluated, further emphasizing the need for more pediatric-specific research in ureteroscopy and stone manipulation.

According to our study, and in line with the demographics analyzed, there was no discernible difference between the two groups in terms of the prevalence of kinked ureters or the number of stones in the groups under study. This aligns with the inclusion requirements present in Chen et al.,8 who found that there was no difference between the two groups regarding the ureter condition (p = 0.878). This study did not evaluate the outcomes of dusting vs. fragmentation in the setting of multiple stones, a patient demographic analyzed by Chen et al. Their dusting group had a significantly higher number of patients with multiple ureteral stones (p = 0.023).

According to our study’s outcomes, there was no discernible difference between the two groups’ retropulsion rates. This outcome does not align with the findings of Chen et al.,8 who reported that the dusting group had a significantly higher retropulsion rate compared to the fragmentation group (p = 0.022).

All patients in Group B required the use of a stone basket retrieval. Group B demonstrated a significantly higher SFR compared to Group A (p = 0.019). The utilization of basket retrieval presents a potential confounder as it can represent multicollinearity.17 When compared to the fragmentation group, the dusting group’s SFR was marginally lower (p = 0.159). The secondary intervention rate in the dusting group was marginally lower (p = 0.115) than in the fragmentation group, despite the dusting group having a higher retropulsion rate and a lower SFR. The operative time, effectiveness, insertion rate for both types of ureteral stents, ureteral injury rate, and complication rate did not differ statistically significantly between the two groups (all p > 0.05).

Reviewing our study’s analysis, there was no discernible difference in the length of hospital stays between the two groups. This supports what was found by El-Nahas et al.25 that regardless of the technique used, hospital stay time had no significant difference (p = 0.686). Based on the findings of this study, in instances where shorter operative time is imperative due to poor surgical candidacy, the utilization of the dusting technique should be considered. Selection of optimal technique should be individualized, considering not only patient-specific anatomical variables, but clinical variables as well. Examples of such factors include stone burden, composition, and associated comorbidities.

Regarding the use of univariate and multivariate regression analyses to predict SFR, the present study shows that the only significant predictor of SFR (p ≤ 0.05) was the rate at which stone baskets were used. This is in line with the findings of Chen et al. (OR = 8.095).8

Limitations and suggestions: The generalizability of the study’s findings is limited by its small sample size.27 To enhance validity and applicability, future research should replicate the study using larger, probability-based samples. Additionally, conducting similar studies in different populations and with varying differential diagnoses may provide broader insights and strengthen the evidence base.28–30 Future insights can evaluate both techniques in a wider range of clinical settings, such as multiple stones. It is important to standardize SFR detection methods. Future studies should standardize SFR determination with the best available modality to prevent unequal detection rates. The usage of stone basket retrieval in the cases of fragmentation influences multicollinearity; future studies analyzing fragmentation vs. dusting should consider strategies to standardize this potential confounder across all individuals in the study.

Both dusting and fragmentation techniques employing the Holmium:YAG laser have been demonstrated to be safe and efficacious modalities for the management of pediatric ureteral calculi. While fragmentation is associated with a superior stone-free rate, it typically necessitates prolonged operative times and the deployment of ancillary instruments, such as retrieval baskets, to extract residual fragments. The benefits of fragmentation lie in populations where recurrence of ureterolithiasis and subsequent treatment is a large concern. Conversely, the dusting approach offers the advantages of abbreviated procedural time and removes the need for additional equipment. While these advantages potentially reduces procedural complexity and associated morbidity, it is important to note that certain outcomes tied to complexity, such as average hospital stay time, were found to be non-significantly different between the two groups. However, the two techniques should be analyzed in a demographic where procedural complexity can lead to significant differences in various outcomes. Studies analyzing potential long-term sequelae, via longer follow-up, as well as large multicenter trials are imperative. Furthermore, additional comparative studies are warranted to evaluate the efficacy and safety of these techniques in complex clinical scenarios, such as cases involving multiple calculi or infection-associated stones.

Acknowledgement

A special thanks to Aswan University for conducting this randomized controlled trial (RCT). Thanks to the Aswan Faculty of Medicine Ethical Committee for recognizing the potential impact of this RCT and ensuring ethical compliance.

Funding Statement

No external funding was utilized for the completion of this RCT.

Author Contributions

The authors of this paper confirm their respective contributions as follows. Study Conception and Design: Ahmed Ahmed, Bilal Farhan, Amr Alam-Eldin, Maged Amin Helmy, Suraj Nayan Vodnala, Mohammed Mostafa Hussein, Zakieldahshoury Mohamed, Hassaan A. Gad. Data Collection: Ahmed Ahmed, Bilal Farhan, Amr Alam-Eldin, Maged Amin Helmy, Mohammed Mostafa Hussein, Zakieldahshoury Mohamed, Hassaan A. Gad. Analysis and Interpretation of Results: Ahmed Ahmed, Bilal Farhan, Amr Alam-Eldin, Maged Amin Helmy, Suraj Nayan Vodnala, Mohammed Mostafa Hussein, Zakieldahshoury Mohamed, Suraj Nayan Vodnala. Draft Manuscript Preparation: Ahmed Ahmed, Bilal Farhan, Amr Alam-Eldin, Maged Amin Helmy, Suraj Nayan Vodnala, Mohammed Mostafa Hussein, Zakieldahshoury Mohamed, Hassaan A. Gad. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials

The data that support the findings of this study, participant data, and other utilized materials are available from the corresponding author, Suraj Nayan Vodnala, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval

Approval of this RCT was granted by the Aswan Faculty of Medicine Ethical Committee. IEC Ref NO.: Asw.Uni. /821/7/23. Date of Approval—7 April 2023. Approval was granted by Dr. Mohamed Zaki Ali Ahmed (Chairman of Ethical Committee Board & Dean of Aswan Faculty of Medicine) and Dr. Moustafa Adam Ali (Vice Dean for Graduate Studies and Research Affairs). A copy of the Ethics Committee Approval can be provided by the corresponding author, Suraj Nayan Vodnala, upon reasonable request. Patient and parental consent was obtained for participation in this study. For a full copy of this report, please reach out to the corresponding author Suraj Nayan Vodnala.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials

The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/cju.2025.067228/s1.

References

1. Enikeev D, Grigoryan V, Fokin I et al. Endoscopic lithotripsy with a SuperPulsed thulium-fiber laser for ureteral stones: a single-center experience. Int J Urol 2021;28(3):261–265. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

2. Martov A, Gudkov A, Diamant V, Chepovetsky G, Lerner M. Investigation of differences between nanosecond electropulse and electrohydraulic methods of lithotripsy: a comparative in vitro study of efficacy. J Endourol 2014;28(4):437–445. doi:10.1089/end.2013.0649. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Ziaeefar P, Basiri A, Zangiabadian M et al. Medical expulsive therapy for pediatric ureteral stones: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Clin Med 2023;12(4):1410. doi:10.3390/jcm12041410. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Barreto L, Jung JH, Abdelrahim A, Ahmed M, Dawkins GPC, Kazmierski M. Medical and surgical interventions for the treatment of urinary stones in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019;10(10):CD010784. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010784.pub3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Życzkowski M, Bogacki R, Nowakowski K et al. Application of pneumatic lithotripter and holmium laser in the treatment of ureteral stones and kidney stones in children. Biomed Res Int 2017;2017(6):2505034. doi:10.1155/2017/2505034. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Elderwy AA, Gadelmoula M, Elgammal MA et al. Primary versus deferred ureteroscopy for management of calculus anuria: a prospective randomized study. Cent Eur J Urol 2018;71(4S):462. [Google Scholar]

7. Rabani SSM, Rashidi N. Laser versus pneumatic lithotripsy with semi-rigid ureteroscope; a comparative randomized study. J Lasers Med Sci 2019;10(3):185–188. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

8. Chen BH, Lin TF, Tsai CC, Chen M, Chiu AW. Comparison of fragmentation and dusting modality using Holmium YAG laser during ureteroscopy for the treatment of ureteral stone: a single-center’s experience. J Clin Med 2022;11(14):4155. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

9. Aldoukhi AH, Black KM, Ghani KR. Emerging laser techniques for the management of stones. Urol Clin North Am 2019;46(2):193–205. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

10. Doizi S. Dusting, fragmenting, popcorning, popdusting. Presented at: 37th World Congress of Endourology (WCE); 2019 Oct 29–Nov 2; Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. [Google Scholar]

11. Siener R, Herwig H, Rüdy J, Schaefer RM, Lossin P, Hesse A. Urinary stone composition in Germany: results from 45,783 stone analyses. World J Urol 2022;40(7):1813–1820. doi:10.1007/s00345-022-04060-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Ma RH, Luo XB, Li Q, Zhong HQ. The systematic classification of urinary stones combine-using FTIR and SEM-EDAX. Int J Surg 2017;41(4):150–161. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2017.03.080. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Zhang D, Li S, Zhang Z et al. Urinary stone composition analysis and clinical characterization of 1520 patients in central China. Sci Rep 2021;11(1):6467. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-85723-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Smith N, Zhong P. Stone comminution correlates with the average peak pressure incident on a stone during shock wave lithotripsy. J Biomech 2012;45(15):2520–2525. doi:10.1016/j.jbiomech.2012.07.025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Fahmy A, Youssif M, Rhashad H, Orabi S, Mokless I. Extractable fragment versus dusting during ureteroscopic laser lithotripsy in children: prospective randomized study. J Pediatr Urol 2016;12(4):254.e1–254.e4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

16. Wason SE, Monfared S, Ionson A et al. Ureteroscopy. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL, USA: StatPearls Publishing; 2025 [cited 2025 Apr 30]. Available from:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560556/. [Google Scholar]

17. Matlaga BR, Chew B, Eisner B, Humphreys M et al. Ureteroscopic laser lithotripsy: a review of dusting vs fragmentation with extraction. J Endourol 2018;32(1):1–6. doi:10.1089/end.2017.0641. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Lepine HL, Vicentini FC, Molina WR et al. Impact of either trendelenburg or reverse trendelenburg positioning for ureteroscopy lithotripsy procedures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Urol 2025;213(1):8–19. doi:10.1097/JU.0000000000004258. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Lightner DJ, Wymer K, Sanchez J, Kavoussi L. Best practice statement on urologic procedures and antimicrobial prophylaxis. J Urol 2020;203(2):351–356. doi:10.1097/JU.0000000000000509. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Kucukdurmaz F, Efe E, Sahinkanat T, Amasyalı AS, Resim S. Ureteroscopy with holmium: yag laser lithotripsy for ureteral stones in preschool children: analysis of the factors affecting the complications and success. Urology 2018;111(3 Pt 2):162–167. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2017.09.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Roberson NP, Dillman JR, Reddy PO, DeFoor WJr., Trout AT. Ultrasound versus computed tomography for the detection of ureteral calculi in the pediatric population: a clinical effectiveness study. Abdom Radiol 2019;44(5):1858–1866. doi:10.1007/s00261-019-01927-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Dogan HS, Onal B, Satar N et al. Factors affecting complication rates of ureteroscopic lithotripsy in children: results of multi-institutional retrospective analysis by pediatric stone disease study group of turkish pediatric urology society. J Urol 2011;186(3):1035–1040. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2011.04.097. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Loffing F. Raw data visualization for common factorial designs using spss: a syntax collection and tutorial. Front Psychol 2022;13:808469. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.808469. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Purpurowicz Z, Sosnowski M. Endoscopic holmium laser treatment for ureterolithiasis. Cent European J Urol 2012;65:24–27. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

25. El-Nahas AR, Almousawi S, Alqattan Y et al. Dusting versus fragmentation for renal stones during flexible ureteroscopy. Arab J Urol 2019;17(2):138–142. doi:10.1080/2090598x.2019.1601002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Gauhar V, Teoh JYC, Mulawkar PM, et al. Comparison and outcomes of dusting versus stone fragmentation and extraction in retrograde intrarenal surgery: results of a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cent European J Urol 2022;75(1):317. doi:10.1186/s12894-023-01283-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Biau DJ, Kernéis S, Porcher R. Statistics in brief: the importance of sample size in the planning and interpretation of medical research. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2008;466(9):2282–2288. doi:10.1007/s11999-008-0346-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Peters U, Sherling HR, Chin-Yee B. Hasty generalizations and generics in medical research: a systematic review. PLoS One 2024;19(7):e0306749. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0306749. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Maro JC, Toh S. Invited commentary: go big and go global-executing large-scale, multisite pharmacoepidemiologic studies using real-world data. Am J Epidemiol 2022;191(8):1368–1371. doi:10.1093/aje/kwac096. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Ellsworth SG, Van Rossum PSN, Mohan R, Lin SH, Grassberger C, Hobbs B. Declarations of independence: how embedded multicollinearity errors affect dosimetric and other complex analyses in radiation oncology. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2023;117(5):1054–1062. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2023.06.015. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools