Open Access

Open Access

CASE REPORT

Spontaneous rupture of the urinary bladder after pelvic angioembolization: high clinical suspicious for prompt diagnosis is the key

Department of Urology, Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, Pennsylvania State University, Hershey, PA 17033, USA

* Corresponding Authors: Alireza Aminsharifi. Email: ,

Canadian Journal of Urology 2025, 32(5), 515-520. https://doi.org/10.32604/cju.2025.067973

Received 17 May 2025; Accepted 20 August 2025; Issue published 30 October 2025

Abstract

Background: Spontaneous rupture of the urinary bladder (SRUB) is a rare condition characterized by bladder rupture without any trauma or previous instrumentation. Diagnosing SRUB can be challenging, leading to potential delays in treatment and significant morbidity. Case description: We present a case of a 75-year-old male with a complex medical history, including atrial fibrillation, systemic lupus erythematosus, antiphospholipid syndrome, and chronic anticoagulation, who developed sudden onset gross hematuria and abdominal pain following bilateral internal iliac artery angioembolization for a spontaneous pelvic hematoma in the setting of supratherapeutic anticoagulation. Extraperitoneal bladder perforation was confirmed by CT cystogram. Conservative management failed, and bladder exploration confirmed a friable, ischemic bladder wall defect. Bladder repair was performed with reinforcement using an absorbable fibrin sealant patch. Follow-up imaging demonstrated gradual resolution of urine extravasation, and the patient ultimately regained spontaneous voiding after catheter removal. Conclusions: This report underscores the importance of high clinical suspicion for SRUB in patients with pelvic ischemic insults, particularly after angioembolization. Although rarely reported in the literature, bladder rupture may represent a potential complication in this setting. Early imaging and surgical intervention are critical for favorable outcomes. Clinicians should consider ischemia-related SRUB in differential diagnoses to reduce diagnostic delays and optimize management strategies.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileSpontaneous rupture of the urinary bladder (SRUB) is defined as a rupture of the bladder in the absence of trauma or direct injury from instrumentation or previous bladder surgery.1 Bladder injury and trauma account for the majority of bladder ruptures, however, in about 3% of cases, in one series, there is no history of a traumatic event.2 SRUB is a relatively rare condition, with an incidence of 1 in 50,000 emergency department visits.3 Because symptoms of SRUB can be subtle, and in the case of extraperitoneal rupture are nonspecific, establishing a diagnosis can be challenging.4 The median time from SRUB to clinical presentation is 48 h, with about 76% of patients presenting with abdominal pain as the primary symptom.1 Furthermore, urine leakage after spontaneous bladder rupture may lead to abscess or other infectious complications. Reabsorption of urea and creatinine can lead to renal insufficiency and sometimes renal failure.4 Given high associated mortality between 47% and 80%, it is imperative to promptly identify SRUB with appropriate imaging (i.e., Computerized tomography (CT) or X-ray cystogram), or direct visualization.1

In this study, we present a case of spontaneous bladder rupture following bilateral internal iliac artery embolization. To the best of our knowledge, there have been no reports of bladder rupture secondary to angioembolization.5 We discuss the diagnosis and management algorithms of this rare but significant event. This case report was exempted from Institutional Review Board (IRB) review in accordance with the policies of the IRB of The Pennsylvania State University. All patient identifiers were removed, and no identifiable personal data are presented in this report.

A 75-year-old male with a history of atrial fibrillation and antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) on warfarin, systolic heart failure, coronary artery disease, and benign prostatic hyperplasia presented to the emergency department for evaluation of shortness of breath.

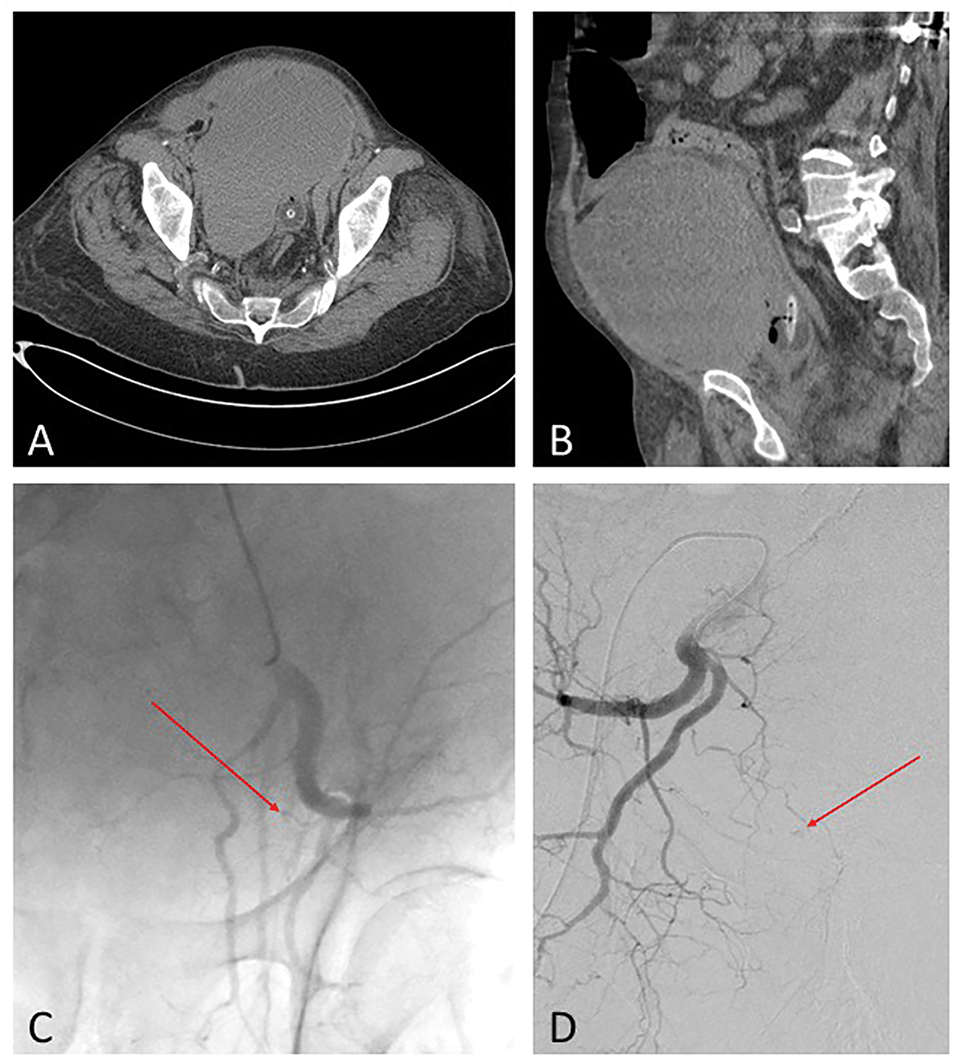

The patient was initially admitted for respiratory distress secondary to COVID-19, managed with oxygen therapy. During his hospital admission, the patient became hemodynamically unstable, and further evaluation with axial imaging studies confirmed an expanding pelvic hematoma (Figure 1A,B) with supratherapeutic international normalized ratio (INR) up to 10.6. The patient had intermittent episodes of hypotension (systolic blood pressure between 70–80 mmHg) that were responsive to fluid resuscitation. His hemoglobin levels had decreased from 11.9 g/dL on presentation to 8.4 g/dL. A CT-angiogram of the abdomen and pelvis showed active arterial extravasation associated with a spontaneously enlarging pelvic hematoma without any preceding pelvic trauma. Active extravasation from right and left internal iliac arterial branches was confirmed in angiogram (Figure 1C,D) and managed successfully by angioembolization using Gelfoam slurry.

FIGURE 1. Pelvic computerized tomography (CT) scan of the large expanding pelvic hematoma in a patient with supratherapeutic international normalized ratio (INR) up to 10.6. (A) Axial; (B) Sagittal view. Active extravasation (Arrows) from (C) left and (D) right internal iliac arterial branches was confirmed in angiogram

About 24 h after the embolization, the patient developed gross hematuria with clot passage. Cystoscopic examination of the bladder showed nonspecific areas of inflammation and hyperemia, with no active bleeding, perforation, or clot burden identified.

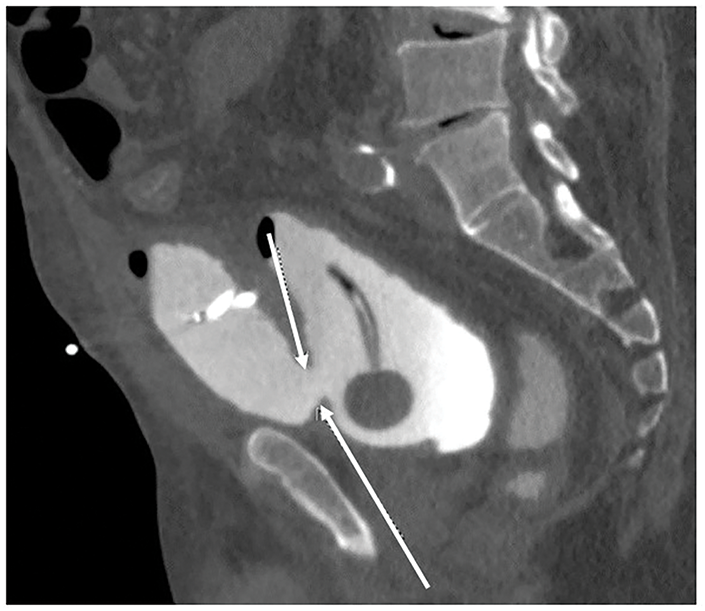

About 48 h after cystoscopy, he developed lower abdominal pain, anuria, and a slight rise in creatinine level to 1.06 mg/dL from 0.84 mg/dL. A CT cystogram was obtained, demonstrating a 2 × 2 cm extraperitoneal anterior bladder wall perforation with extravasation of contrast to the space of Retzius (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2. Extraperitoneal extravasation of contrast into the space of Retzius was demonstrated on computerized tomography (CT) cystogram after spontaneous rupture of the urinary bladder. Arrows show the defect at the anterior bladder wall

Initially, conservative management was attempted. A Foley catheter was maintained, and a percutaneous drain was placed into the space of Retzius. After two days, the patient became febrile and urine output shifted exclusively from the pelvic drain. After discussing options, he was taken to the operating room promptly for a prompt exploratory laparotomy and repair of the bladder.

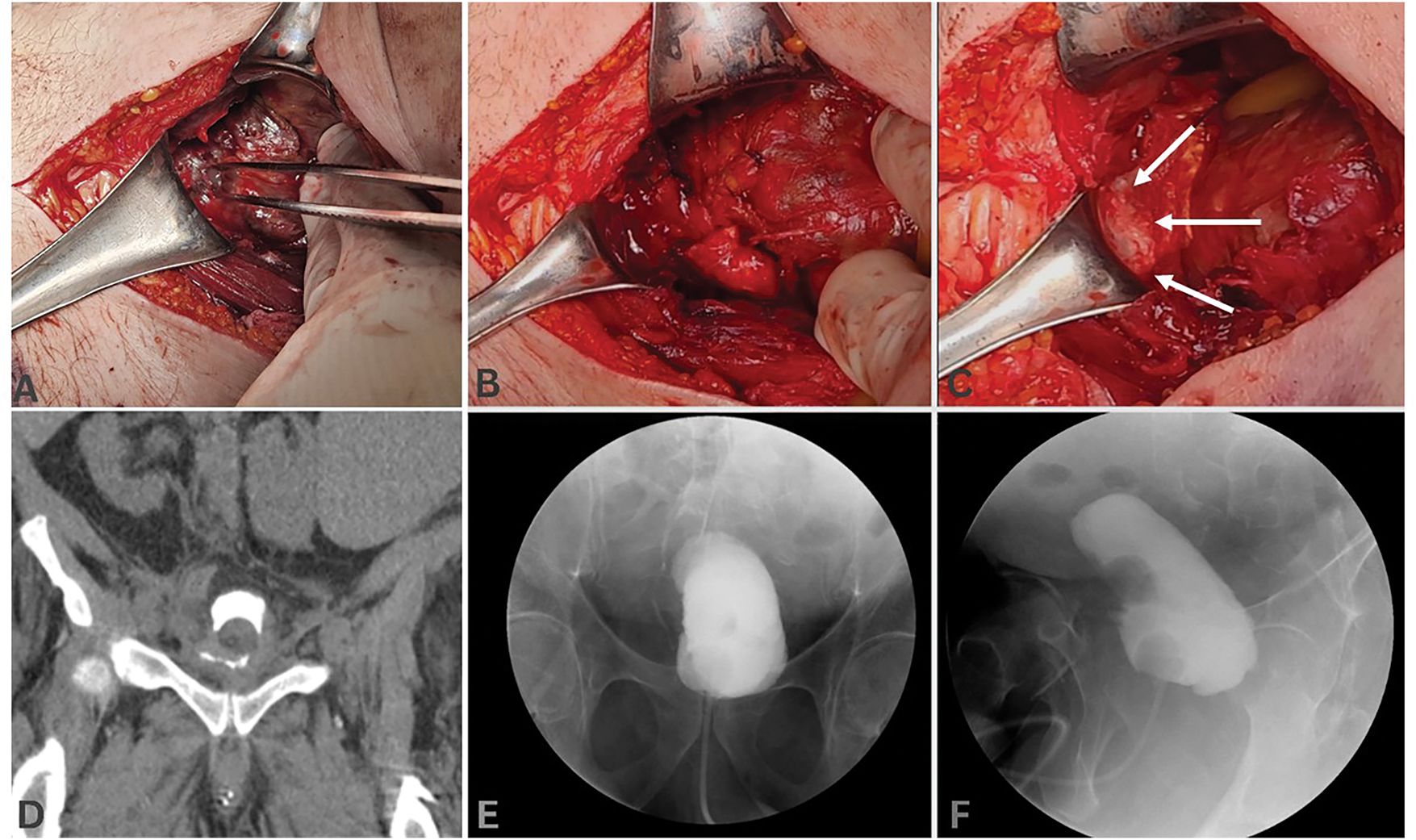

Through a low midline abdominal incision, the space of Retzius was developed. After evacuation of the old pelvic hematoma and urinoma, a 2 × 2 cm bladder defect on the anterior bladder wall was identified (Figure 3A), along with severe inflammation and severe ischemia around the site of perforation. The bladder repair was performed using 0-PDS running stitches in two layers (Figure 3B). To enhance tissue sealing, a 3 × 3 cm absorbable fibrin sealant patch (TachoSil®, Baxter, CA, USA) was applied and fixed at the site of cystorrhaphy for further reinforcement (Figure 3C). We avoided entry into the peritoneal cavity to allow further containment of any further urine leakage or recurrent hemorrhage. The bladder was drained with a Foley catheter A cystostomy tube and an external drain were placed in the pelvic cavity.

FIGURE 3. Intraoperative view of the bladder after development and exploration of the Retzius space through a low midline abdominal incision. After identification of (A) the site of bladder rupture, it was repaired in (B) two layers and was reinforced by placement of (C, arrows) a 3 × 3 cm absorbable fibrin sealant patch (TachoSil®, Baxter, CA, USA). (D) Post-operative CT-cystogram 6 weeks after the surgery showed minimal persistent urine extravasation. No urine leakage was demonstrated 8 weeks after the surgery on X-ray cystogram, (E) coronal, (F) sagittal views

Total operative time was about 140 min, and the patient tolerated the procedure well, with no ongoing blood loss from the pelvic cavity. The patient was discharged on postoperative day 6 with a Foley and cystostomy tube. A postoperative cystogram, 6 weeks after the surgery, showed improvement, but persistent urine extravasation (Figure 3D). At 8 weeks after the surgery, the integrity of the bladder was confirmed with a repeat cystogram (Figure 3E,F). Subsequently, the Foley was removed, and after clamping of the cystostomy, the patient had a spontaneous voiding pattern. Following one week of clamping, the cystostomy was finally removed. The patient was subsequently lost to follow-up, and no data on his voiding symptoms or characteristics could be obtained.

Figure 4 summarizes the timeline of clinical events, diagnostic steps, conservative and surgical management, as well as follow-up milestones.

FIGURE 4. The timeline of clinical events, diagnostic steps, conservative and surgical management, as well as follow-up milestones in a patient with spontaneous bladder rupture

For our patient, due to high clinical suspicion, the diagnosis of bladder rupture was confirmed with CT cystogram. Surgical exploration demonstrated the site of perforation with friable and ischemic bladder tissue, likely secondary to recent angioembolization. Other etiologies of perforation could include trauma, malignancy, or connective tissue disease related to SLE. Etiologies of the pelvic hematoma include arteriovenous malformation, pseudoaneurysm, or spontaneous perforation with connective tissue disorder. No definitive vascular malformations were identified on angiography, and the hemorrhage was likely exacerbated by the patient’s supratherapeutic anticoagulation.

In this patient, SRUB was likely caused by bladder wall ischemia. Bilateral internal iliac artery embolization compromised the primary arterial supply. Perhaps collateral flow was impaired due to hypotension combined with the prothrombotic state of both antiphospholipid syndrome and acute COVID infection. Previously, Ketata et al. reported that ischemia from radiation can cause the spontaneous rupture of the bladder. They presented a rare but life-threatening event of spontaneous intraperitoneal bladder rupture 17 years after radiation for prostate cancer. They admitted the difficulties in establishing the diagnosis and emphasized a prompt surgical exploration and repair.6 Pelvic organ ischemia is a rare but well-known complication of angioembolization of internal iliac vessels. Erectile dysfunction and buttock claudication, as well as rare cases of ischemic necrosis of skin, colon, and gluteal muscles, have been reported.7

Prompt treatment is critical to decrease mortality in patients with SRUB.6 This consists primarily of establishing urine drainage with or without primary closure of the perforation site, as well as adequate antibiotic therapy.2 In our patient, we performed primary repair with adjunctive use of an equine collagen patch coated with human fibrinogen and thrombin (TachoSil®; Baxter, CA, USA) to reinforce the already ischemic bladder defect. Success with this material has been reported in the urologic literature for water-tight sealing of defects in the penile corpora cavernosa in excision and grafting for Peyronie’s disease.8 The patch can provide an additional layer of tissue sealing and may contribute to bladder repair in these challenging cases. The efficacy of TachoSil® as a sealing material has also been shown in the setting of percutaneous nephrolithotomy and partial nephrectomy.9,10

As shown on serial postoperative cystograms (Figure 3D–F), the course of bladder repair in the setting of ischemia might be prolonged compared to traumatic bladder rupture. This allows maximal opportunity for healing and reduces the risk of recurrent perforation in the postoperative period. Consideration should also be made for resulting bladder dysfunction or detrusor hypocontractility after ischemic injury, which can be evaluated using uroflowmetry and post-void residual measurements. Due to the limited number of cases of SRUB and the fact that many of these patients are clinically unstable, studies designed to compare the outcomes of early surgical intervention versus conservative management, although advisable, are difficult to undertake.

This report highlights a rare occurrence of SRUB following bilateral internal iliac artery embolization, a previously unreported complication. In our case, high clinical suspicion and imaging with CT cystogram confirmed the bladder rupture. Surgical exploration revealed a bladder defect with ischemic and friable tissue, likely attributable to an ischemic process. Early diagnosis, urine drainage, and appropriate antibiotic therapy with a low threshold for surgical exploration and closure of the perforation site, in case of failed conservative management, remain the mainstay of treatment for SRUB to mitigate the associated morbidity and mortality.

Acknowledgement

None.

Funding Statement

None.

Author Contributions

Raidizon Mercedes: Study conception, study design, draft manuscript preparation; Eric Eidelman: Study conception, study design, draft manuscript preparation; Michael Mawhorter: Study conception, study design, draft manuscript preparation; Max Yudovich: Study conception, study design, draft manuscript preparation; Alireza Aminsharifi: Study conception, study design, critical revision of the draft. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials

There is no additional data available for this study. Readers can reach out to the corresponding author for requesting data related to this study.

Ethics Approval

This case report was exempted from Institutional Review Board (IRB) review in accordance with the policies of the IRB of The Pennsylvania State University.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials

The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/cju.2025.067973/s1.

References

1. Reddy D, Laher AE, Lawrentschuk N, Adam A. Spontaneous (idiopathic) rupture of the urinary bladder: a systematic review of case series and reports. BJU Int 2023 Jun;131(6):660–674. [Google Scholar]

2. Murata R, Kamiizumi Y, Tani Y et al. Spontaneous rupture of the urinary bladder due to bacterial cystitis. J Surg Case Rep 2018 Sep 29;2018(9):rjy253. [Google Scholar]

3. Su PH, Hou SK, How CK, Kao WF, Yen DHT, Huang MS. Diagnosis of spontaneous urinary bladder rupture in the ED. Am J Emerg Med 2012;30(2):379–382. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

4. Sholklapper T, Elmahdy S. Delayed diagnosis of atraumatic urinary bladder rupture. Urol Case Rep 2021;38(5):101723. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

5. Bonde A, Velmahos A, Kalva SP, Mendoza AE, Kaafarani HMA, Nederpelt CJ. Bilateral internal iliac artery embolization for pelvic trauma: effectiveness and safety. Am J Surg 2020 Aug;220(2):454–458. [Google Scholar]

6. Ketata S, Boulaire JL, Al-Ahdab N, Bargain A, Damamme A. Spontaneous intraperitoneal perforation of the bladder: a late complication of radiation therapy for prostate cancer. Clin Genitourin Cancer 2007;5(4):287–290. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

7. Tran S, Wilks M, Dawson J. Endovascular management of hemorrhage in pelvic hematoma. Surg Pract Sci 2021;6:100039. [Google Scholar]

8. Fernández-Pascual E, Manfredi C, Torremadé J et al. Multicenter prospective study of grafting with collagen fleece tachosil in patients with peyronie’s disease. J Sex Med 2020;17(11):2279–2286. [Google Scholar]

9. Bryniarski P, Rajwa P, Życzkowski M, Taborowski P, Kaletka Z, Paradysz A. A non-inferiority study to analyze the safety of totally tubeless percutaneous nephrolithotomy. Adv Clin Exp Med 2018;27(10):1411–1416. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

10. Rane A, Rimington PD, Heyns CF, van der Merwe A, Smit S, Anderson C. Evaluation of a hemostatic sponge (TachoSil) for sealing of the renal collecting system in a porcine laparoscopic partial nephrectomy survival model. J Endourol 2010;24(4):599–603. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools