Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Evaluation and research progress on rodent models of late-onset hypogonadism: a comprehensive review

1 TCM Regulating Metabolic Diseases Key Laboratory of Sichuan Province, Hospital of Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Chengdu, 610075, China

2 Department of Dermatovenereology, Chengdu Second People’s Hospital, Chengdu, 610011, China

3 School of Medical and Life Sciences, Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Chengdu, 611137, China

* Corresponding Authors: Degui Chang. Email: ; Liang Dong. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work.

Canadian Journal of Urology 2025, 32(5), 385-400. https://doi.org/10.32604/cju.2025.068136

Received 21 May 2025; Accepted 20 August 2025; Issue published 30 October 2025

Abstract

Late-onset hypogonadism (LOH), characterized by the intersection of aging and androgen deficiency, impacts the health of approximately 2%−39% of middle-aged and elderly men, underscoring the need for comprehensive research. Animal models, serving as analogs of human diseases, are indispensable for investigating disease mechanisms and facilitating drug development. However, the diverse array of animal models utilized for LOH research has led to a lack of standardized modeling approaches and evaluation systems, potentially impeding progress in understanding the pathogenesis and therapeutic development. In this paper, we summarize and compile the characteristics, methods, and evaluation systems of rodent models for LOH research reported in the literature, and analyze the advantages and disadvantages of each model, to facilitate the optimal choice and development of rodent models for LOH research.Keywords

Androgen levels, including testosterone (T), decline progressively with age in men, and older men often experience physical, mental, and sexual symptoms associated with aging and low testosterone levels, known as late-onset hypogonadism (LOH),1 which affects 2% to 39% of middle-aged and elderly men’s health.2 Patients with LOH typically present with a cluster of symptoms including hypogonadism, depression, anxiety, decreased physical function, and memory decline.1,3 Additionally, men affected by LOH exhibit elevated risks of metabolic and cardiovascular diseases,4,5 alongside increased cardiovascular mortality and all-cause mortality rates.6 As the primary pharmacological intervention for LOH, testosterone replacement therapy (TRT) has demonstrated efficacy in improving sexual function, quality of life,7–10 and metabolic parameters11 through multiple meta-analyses. Emerging evidence also suggests that its risks for prostate conditions—including benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and prostate cancer (PCa)—may be less significant than previously assumed. TRT’s therapeutic benefits may surpass recurrence risks even in post-PCa treatment scenarios,10,12 as the principal androgen regulating prostate development,13 testosterone’s effects necessitate careful evaluation. Current TRT safety data predominantly derive from short- to medium-term studies. Acute testosterone administration has been associated with transient elevations in prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels, prostate volume, and blood pressure.11 Current investigations predominantly assess direct cardiovascular endpoints, with limited attention to TRT’s secondary metabolic impacts. Consequently, the carcinogenic and cardiovascular risks associated with prolonged TRT regimens remain inconclusive. Caution should be exercised when administering TRT to patients with LOH.

Over the past few decades, as the scientific community’s understanding of the pathogenesis and characteristics of LOH has gradually advanced, the name of this disease has undergone a series of changes. However, numerous studies continue to use alternative terms, including functional hypogonadism (adopted by the 2020 European guidelines to supersede ‘late-onset hypogonadism’),14 male climacteric,15 age-related male menopause,16 organic hypogonadism,17 andropause,18 and partial androgen deficiency of aging men (PADAM).19 This inconsistency in nomenclature complicates research efforts and comparative analysis across studies. Rodent models for the study of LOH are also diversified, and different models have their strengths and weaknesses for different research purposes, which adds complexity and challenge to the selection of animal models for LOH. In addition, the selection of animal models also affects the accuracy of drug testing and mechanism studies, and it is necessary to reevaluate the existing LOH models and to develop new animal models to promote the progress of LOH research. This study mainly aims to summarize the characteristics of rodent models of LOH, the evaluation methods, and analyze their strengths and weaknesses, and put forward ideas of improvement in future research, to provide a reference for the selection and development of models for the subsequent study of LOH.

Essential Elements of an Ideal LOH Animal Model

Simulating the etiology and pathogenesis of LOH

Etiologically, LOH can be classified into primary, secondary, and mixed types.20 The pathogenesis involves bidirectional interactions between metabolic inflammation and gonadal aging.21 This encompasses multi-level alterations: aging-induced testicular functional decline, microenvironmental imbalance, progressive hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis deterioration, cumulative damage from systemic metabolic disorders, and synergistic amplification via chronic inflammation and oxidative stress.22–24

Testicular dysfunction represents the core mechanism in LOH pathogenesis.23,25 Aging induces seminiferous tubule basement membrane thickening, luminal atrophy, and significant reduction of key functional cells (e.g., Leydig and Sertoli cells).26,27 Additionally, aging impairs Sertoli cell degradative capacity, compromises lysosomal acidification, and promotes lipid accumulation, collectively disrupting testicular microenvironment homeostasis.28,29 The HPG axis—a core regulatory system for reproductive and metabolic balance—progressively declines with aging.30–32 The condition manifests in three ways: (1) diminished pulsatile GnRH secretion from the hypothalamus, exhibiting altered frequency and regularity;33–36 (2) reduced pituitary responsiveness to GnRH, resulting in modified gonadotropin secretion patterns;34,37 and (3) progressive gonadal secretory dysfunction.34 Furthermore, aging elevates risks of metabolic disorders (e.g., diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia).38,39 These directly exacerbate hypogonadism by impairing testicular cell function and disrupting HPG axis regulation, causing hormonal disorders.40–42

Chronic inflammation and oxidative stress are key recent advances in understanding LOH pathogenesis.42 Inflammation—a defensive response to infection or injury—becomes chronically activated during aging via: persistent low-grade immune activation, sustained pro-inflammatory cytokine release, and pro-inflammatory secretory phenotype development, causing systemic cellular damage.43,44 Oxidative stress refers to pathological accumulation of reactive oxygen (ROS) and nitrogen species (RNS) that disrupt redox homeostasis, inducing multi-organ pathophysiological alterations. These processes are interconnected: ROS activates inflammatory pathways (e.g., NF-κB), driving inflammatory cell infiltration and mediator release. Conversely, chronic inflammation stimulates excessive ROS generation. This self-reinforcing cycle synergistically damages neuroendocrine structures in the testes and HPG axis.43

These factors reciprocally interact, intertwine, and mutually exacerbate, collectively impairing Leydig cell function and testosterone biosynthesis, ultimately causing LOH.45 Consequently, an ideal LOH animal model should recapitulate key aspects of this etiopathogenesis. Among the four primary pathogenic mechanisms of LOH—testicular dysfunction, HPG axis disruption, systemic metabolic disease involvement, and chronic inflammation with oxidative stress. Animal models should prioritize simulating testicular dysfunction and HPG axis disruption. Although systemic metabolic diseases and chronic inflammation/oxidative stress also significantly contribute to LOH pathogenesis, they primarily mediate the condition through testicular impairment and HPG axis disruption.

Simulating the sex hormone changes in LOH

During the pathogenesis of LOH, alterations in various hormone levels constitute both a component of its pathological mechanism and a primary clinical manifestation post-onset.21 Consequently, animal models should comprehensively simulate LOH-associated sex hormone fluctuations—including total testosterone (TT), free testosterone (FT), luteinizing hormone (LH), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), and sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) levels—aligned with research objectives. In most LOH animal models, TT and FT levels serve as key indicators for validating successful modeling. Typically, serum TT levels below 8 nmol/L (231 ng/dL) and serum FT levels below 8.5 pg/mL support LOH diagnosis.20 Furthermore, secondary hypogonadism exhibits decreased LH and FSH due to HPG axis dysfunction, whereas primary hypogonadism demonstrates elevated LH and FSH resulting solely from testicular impairment.30,46 This distinction facilitates differentiation between primary and secondary LOH models, enabling mechanistic studies of heterogeneous pathogenesis.

Although concepts like testosterone annual decrease velocity47 and testosterone secretion index (TSI, calculated as TT/LH ratio)48 remain underutilized in LOH diagnosis due to insufficient large-scale multicenter validation; their potential utility in animal model assessment warrants consideration. These parameters may offer valuable insights given the roles of aging and testicular secretory function in LOH progression.

Simulating the symptomatology and behavioral manifestations of LOH

Patients with LOH experience a range of sexual and non-sexual symptoms and signs. A diagnosis of LOH cannot be established solely based on decreased hormone levels or impaired testicular function, necessitating animal models that replicate relevant clinical manifestations to align with current guidelines.3,49 Sexual symptoms—including decreased libido, reduced spontaneous erections, and erectile dysfunction—can be evaluated in animal models through Sexual Index (a comprehensive sexual behavior assessment index, including sniffing, mounting, intromission, etc.), mating frequency, mounting frequency, post-ejaculation intervals, and opposite-sex social interaction behaviors.29,50,51 Non-sexual symptoms manifest as reduced energy, diminished physical/functional activity, decreased vitality, and impaired attention.52,53 These are primarily assessed via behavioral indicators in mice, such as open field tests, running wheel experiments, and grip strength measurements. Although depression is not a core clinical feature of LOH, some models incorporate depression-related metrics54—including forced swim, tail suspension, and open field tests—into their evaluations. Histological and physiological changes are directly measurable through parameters like testicular volume and weight, hair density and coverage, and areas of alopecia.

Simulating the testicular tissue morphology changes of LOH

Testicular aging and functional impairment play a crucial role in the pathogenesis of LOH. Aged human testes typically exhibit a series of distinctive pathological alterations,55,56 including thickening of connective tissue and tunica albuginea with reduced parenchymal volume;57 decreased numbers of Leydig cells,58–60 which display cytoplasmic or intranuclear Reinke’s crystals and para-crystalline inclusions, abundant vacuoles and lipid droplets, reduced organelle content, underdeveloped endoplasmic reticulum, and mitochondria exhibiting swelling with cristae disappearance;61–63 increased arteriosclerotic lesions in testicular arteries with luminal narrowing,64,65 degeneration of peritubular capillary networks and reduced blood supply;66 thickening of the seminiferous tubule basement membranes,26,67 narrowing of tubule diameter, tubular sclerosis, germ cell loss, and impaired spermatogenesis;26 reduced Sertoli cell numbers with cytoplasmic vacuolization,27,68,69 rare tight junctions between Sertoli cells and a compromised blood-testis barrier.56,67 Downregulation of StAR and cytochrome P450scc (CYP11A1) protein expression in testicular tissue leads to diminished testosterone synthesis.63 In model animals, these alterations typically encompass changes in testicular weight and volume, structural modifications of seminiferous tubules (including variations in diameter, epithelial height, and structural integrity), and phenotypic transformations in testicular cells such as Sertoli and Leydig cells, manifested through organelle morphology and cellular characteristics. The application of certain aberrantly expressed proteins, such as CYP11A1, remains primarily confined to cytological assays and is less frequently utilized in animal models.

Validity and Reliability Assessment Methods for Animal Models

A robust animal model must demonstrate adequate validity and reliability, as employing appropriate models can significantly advance research progress.70 The primary goal of establishing animal models is to observe the progression of specific mechanisms and corresponding metabolic alterations within these models, thereby inferring their mechanistic roles in humans. Consequently, model validity hinges on the etiological and/or symptomatic similarities between the animal model and human diseases.71 A model is considered valid if it mimics humans in etiology, pathophysiology, clinical symptoms, and responsiveness to therapeutic interventions.71 Validity is usually evaluated through three dimensions: face validity, predictive validity, and construct validity.

Face validity involves phenotypic or morphological similarities; in LOH models, these often include hormonal profiles, tissue alterations, and behavioral symptoms. Predictive validity assesses whether the model accurately reflects human responses, particularly in evaluating the correlation between intervention effects in the model and clinical outcomes in humans. This metric is often obtained from clinical trial data, such as that from drug development research using LOH animal models. Construct validity determines whether the model is based on sound theoretical bases, like etiological parallels, for instance, whether the modelled LOH stems from aging and androgen insufficiency.

Common Rodent Models of LOH and their Advantages/Disadvantages

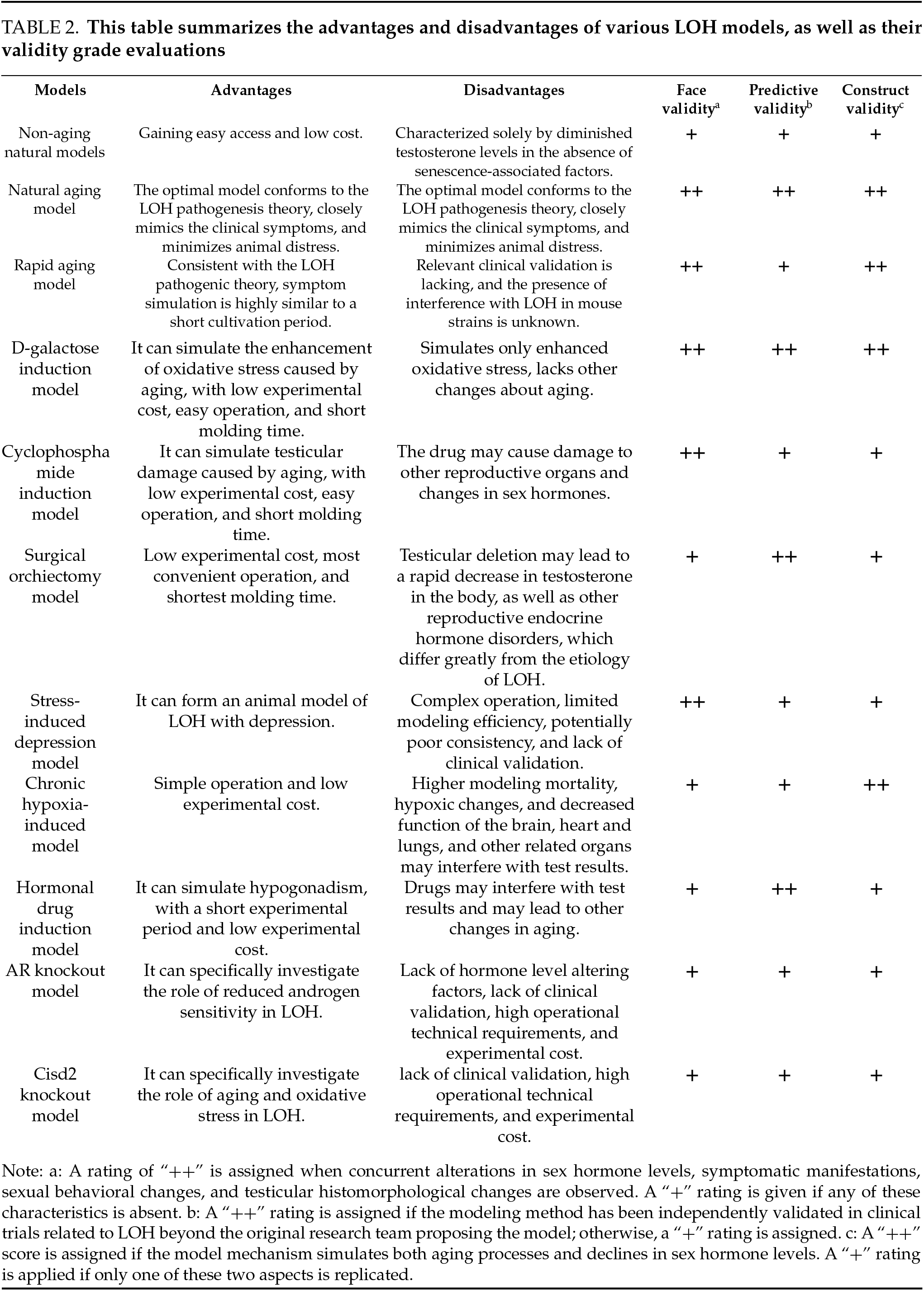

Current LOH research primarily employs rat and mouse models. These models can be categorized as follows based on their induction methods: natural models and artificial induction models (Table 1).

The natural model defined in this paper refers to animals that haven’t undergone any modeling-related interventions during the modeling process and are obtained in a natural growth state. Since aging is a direct and inevitable factor in LOH, ideal model animals should exhibit the aging characteristics of LOH. Wistar and Sprague-Dawley rats are the most commonly used experimental rats globally. The 18-month age of these rats corresponds to approximately 45 years in humans,98,99 which aligns with the initial onset age of human LOH. And significant aging biomarkers emerge at 24 months.100 Thus, naturally aged LOH rat and mouse models should be at least 18 months old to accurately reflect aging effects in LOH. Accordingly, this paper defines natural aged models as those aged 18 months or older and non-naturally aged models as those younger. Additionally, certain artificially bred mouse strains have shorter lifespans and can achieve accelerated aging under natural conditions. Therefore, these are discussed as a separate category.

Non-aging natural LOH models typically utilize young mice with declining androgen levels. Current primary models include 18-week-old, 22-week-old, and 6–7-month-old Sprague-Dawley rats for exploring potential drug interventions against LOH.72–74 Among these, CRS-10—a drug capable of increasing TT and FT in men over 45—was shown to improve testosterone levels and physical activity in 18-week-old Sprague-Dawley rats.72 In the development of Dendropanax morbiferus leaf extract (DME), administration in 6–7-month-old rats led to enhanced physical activity and elevated levels of testosterone, GnRH, follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), and LH, with results largely consistent with DME’s in vitro effects on TM3 cells.73

In summary, these non-aging LOH rat models share the advantages of easy accessibility and low cost. The 18-week-old model successfully answered predefined scientific questions regarding CRS-10’s efficacy in improving LOH-related sex hormones and symptoms, showing clinical validation and robust predictive validity. In contrast, the 6–7-month-old and 22-week-old models failed to provide clinical validation for drug candidates, thus exhibiting limited predictive validity. Neither the 18-week-old nor the 6–7-month-old models underwent formal validation, potentially missing the low serum testosterone characteristic of LOH and showing inadequate aging progression, thereby weakening face and construct validity. Despite some models exhibiting low testosterone traits, excluding the impact of aging on LOH results in their inability to fully mimic the combined effects of aging and hypoandrogenism, thereby limiting face validity.

Natural aging models typically exhibit both aging characteristics and declining serum testosterone levels, making them a common choice for LOH animal models. Currently established natural aging LOH models include 18-month-old Sprague-Dawley rats, 20–24-month-old C57BL/6 mice, and 18–30-month-old Brown Norway rats.

Niu et al. reported that serum testosterone levels in 18-month-old Sprague-Dawley rats were significantly lower than in 6-month-old rats, with more pronounced reductions observed in 24-month-old rats.75 With increasing age, these rats showed thinning of testicular seminiferous epithelium, narrowing of tubules, sparse spermatogenic cells, reduced and irregularly shaped Leydig cells, interstitial fibrosis, and significantly decreased androgen receptor levels,75 resembling aging humans. Another research team found that 18-month-old Sprague-Dawley rats had significantly lower testosterone levels than 4-month-old and 2-month-old young controls.101 Additionally, these older rats exhibited reduced mRNA expression of StAR, P450scc, and HSD3B1 in testicular tissue, indicating impaired testosterone synthesis function,76 thus qualifying as an LOH model.

Male Sprague-Dawley rats aged 18 months or older comprehensively demonstrate the pathological state of low testosterone levels during natural aging, closely resembling LOH pathogenesis.76 In recent years, an increasing number of studies have directly used male Sprague-Dawley rats aged 18 months or older as natural aging LOH models,101–103 showing excellent face validity and construct validity. TRT,103 Bushenfang,76 Xiongcan Yishen Prescription,104,105 and Jiarong tablets101,106 demonstrated anti-LOH effects in both natural aging LOH rat models and clinical studies, indicating good predictive validity of these models.

Naturally aged 20–24-month-old C57BL/6 mice are frequently used as animal models for LOH.78,107 At 24 months, these mice are equivalent to 80-year-old humans.78 Aged mice show significantly increased senescent Leydig cells, elevated senescence-associated secretory phenotype markers (such as interleukin-1β, interleukin-6, and TGF-β) in testicular tissue, increased expression of senescence-related proteins p53, p21, and p16, and reduced testosterone synthase function.78 This strain of naturally aged mice exhibits both aging and testicular dysfunction characteristics, demonstrating good face and construct validity. Furthermore, drug development and mechanistic studies based on this model, including FOXO4-DRI,78 the Chinese herbal medicine saikokaryukotsuboreito (SKRBT),92 and velvet antler polypeptides,108 have shown promising clinical trial results, indicating excellent predictive validity.

Aged Brown Norway rats are considered the optimal rat model for male reproductive aging.79,109 With advancing age, these rats develop testicular atrophy, impaired spermatogenesis, and declining testosterone production in Leydig cells, accompanied by significantly reduced serum testosterone levels.79,109,110 Even with elevated gonadotropins (LH and FSH), Brown Norway rats fail to maintain normal testosterone levels, indicating primary hypogonadism. With advancing age, castrated Brown Norway rats exhibited a progressive decline in LH and FSH levels, whereas the sham-operated group showed no age-related increase in LH levels. This indicates the presence of secondary hypogonadism in aging Brown Norway rats. Although Brown Norway rats exhibited a significant increase in gonadotropin levels following orchiectomy, these levels still demonstrated a progressive decline with advancing age. This observation led to the hypothesis that this strain of aging rats may experience secondary hypothalamic/pituitary failure. Thus, aged Brown Norway rats exhibit primary testicular failure and secondary hypogonadism features. Additionally, their survival curve resembles the human “rectangular” pattern; they are inbred rats with greater genetic homogeneity compared to Sprague-Dawley and Wistar rats; they have long disease-free survival periods without excessive obesity; and they have low risks of pituitary and testicular tumors, minimizing impact on the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis.111 Regarding age, 23-month-old male Brown Norway rats are equivalent to 65-year-old human males, considered the optimal time for studying male aging.79 Therefore, aged Brown Norway rats demonstrate excellent face and construct validity in modeling LOH and offer advantages in studying LOH pathogenesis. Being natural models, they cause minimal suffering to animals. The drawbacks include long acquisition periods, high costs, and a lack of predictive validity verification.

When constructing natural aging LOH models, some studies use 2-month-old, 4-month-old, or 6-month-old young rats as controls for model validation. Among these, 2-month-old rats may lack sufficient maturity, while 6-month-old rats (equivalent to human 18-year-olds) can simulate both sexual and physical maturity. Therefore, 6-month-old rats are recommended as young controls.

Natural aging LOH mouse and rat models can replicate a series of age-related physiological states, such as sarcopenia and osteoporosis, making them ideal for LOH research. Ethically, using naturally aged animals to construct LOH models avoids the need for castration, drug induction, or environmental interventions, minimizing animal suffering. However, these models have disadvantages, including long acquisition times, limited availability, and high costs,54,103 which may restrict their use. Additionally, Yan’s study112 on natural aging, LOH rat models found that 19-month-old Sprague-Dawley rats showed no reduction in serum TT or FT but exhibited relative LH elevation and significantly reduced TSI, consistent with compensated LOH characteristics. These compensated LOH model rats showed compensatory increases in StAR, 3β-HSD, and AR protein expression in testicular tissue. These findings suggest that both rats and humans can develop compensated LOH without reduced TT or FT. Since most current natural aging LOH models assess success based solely on sex hormone levels without further LOH subtyping, future studies should explore natural aging LOH model subtypes based on hormonal profiles.

The SAMP8 mouse is currently widely used as a rapid-aging mouse model for aging-related disease research, with an average life expectancy of 17.2 months, 4 months shorter than its strain control SAMR1 mice.113 Studies have demonstrated that plasma testosterone levels in SAMP8 mice exhibit a significant age-dependent decline, whereas this phenomenon is not pronounced in control SAMR1 mice.80,81 Compared to 4-month-old SAMP8 mice, plasma testosterone levels decreased by 44% and 71% in 8-month-old and 12-month-old SAMP8 mice, respectively.80 10-month-old SAMP8 mice exhibit reduced hypothalamic GnRH release, leading to significantly decreased LH and T secretion, manifesting a series of secondary hypogonadism characteristics.114 Another study confirmed that aged SAMP8 mice show elevated serum LH, increased ROS and inflammatory levels in testicular tissue, reduced activity of testicular steroidogenic enzymes, and decreased T production,81 resembling typical features of primary LOH. These results indicate that SAMP8 mice aged over 8 months demonstrate certain face validity in modeling LOH, while those at 10 and 12 months exhibit better construct validity. Moreover, testosterone therapy can ameliorate learning and memory impairments in 12-month-old SAMP8 mice,80 suggesting good predictive validity. This model offers the advantage of shorter acquisition time compared to traditional natural aging models and could serve as an alternative for studying age-related LOH. However, current research on LOH using accelerated senescence mice remains relatively limited, and it is still uncertain whether this strain may exert additional effects on LOH.

D-galactose plays a significant role in the aging process. When D-galactose exceeds a certain threshold, it converts into aldose and H2O2, generating ROS and O2−, leading to reduced antioxidant enzyme activity, increased oxidative stress, and an imbalance in redox homeostasis similar to that observed in natural aging.82,84 Currently, the D-galactose-induced aging model has been used to study senescence in the brain, kidneys, liver, and blood cells.115 Administering D-galactose to mice and rats for 6–8 weeks can successfully establish a reproductive aging model.82,84

Continuous subcutaneous injection of D-galactose (60 mg/kg) for six weeks in 5-month-old young Sprague-Dawley rats effectively mimics testicular tissue aging.82 In this model, testicular tissues exhibit increased protein oxidation biomarkers, including advanced oxidation protein products (AOPP) and protein carbonyl (PCO), as well as elevated lipid peroxidation markers such as lipid hydroperoxides (LHP) and malondialdehyde (MDA), along with reduced copper-zinc superoxide dismutase (Cu, Zn-Superoxide dismutase [SOD]) activity. Moreover, the redox imbalance in the D-galactose-induced aging model closely resembles that observed in naturally aged 24-month-old rats.82

Intraperitoneal injection of D-galactose (300 mg/(kg day) or 500 mg/(kg day)) for two months in 3-month-old male Sprague-Dawley rats successfully establishes a subacute aging model with androgen deficiency.83 Compared to normal controls, the model rats exhibit dry and yellowish fur, hair loss, reduced activity, decreased serum TT levels, lower SOD content, and elevated MDA levels.83 This model aligns with the characteristics of LOH, including aging-related testosterone deficiency and enhanced oxidative stress. Another study demonstrated that oral administration of D-galactose (500 mg/(kg day)) for six weeks induces reproductive system aging in male mice, manifesting as testicular atrophy, oligospermia, elevated serum LH and FSH levels, but no significant change in testosterone levels,84 consistent with the compensatory hypogonadism observed in LOH.

The D-galactose-induced aging model effectively establishes LOH with strong face and construct validity. This method also offers advantages such as high survival rates, low experimental costs, and ease of use,82 addressing the limitations of natural aging models, including limited animal availability, prolonged rearing periods, and high expenses.

Cyclophosphamide induction model

Cyclophosphamide is an orally active alkylating agent with significant reproductive toxicity. It primarily damages testicular tissues in males through oxidative damage, leading to low testosterone levels.116

The PADAM (Partial Androgen Deficiency in Aging Males) rat model is established through intraperitoneal administration of 20 mg/(kg day) cyclophosphamide for 5–7 consecutive days in either 15-month-old or 2-month-old Sprague-Dawley rats.87,88 PADAM rats treated with cyclophosphamide display significant decreases in serum and free testosterone levels,87 along with increased LH and FSH levels.88 Cyclophosphamide also leads to morphological and quantitative decreases in Leydig cells, structural damage to seminiferous tubules and interstitial tissues, and testicular atrophy.86–88 Electron microscopy shows deformed and ruptured Leydig cells, along with reduced mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum in model rats.88 Protein and mRNA expression of StAR, P450scc, and 3β-HSD in testicular tissues are also diminished.87,88,117,118 The 15-month-old PADAM model exhibits the aging-related symptoms associated with LOH, such as lethargy, slow response, reduced activity, dry fur, weight loss, and osteoporosis.85,86 This model demonstrates significant testicular damage, impaired testosterone synthesis, and low serum androgen levels, exhibiting good face and construct validity. In simulating age-related LOH, the 15-month-old cyclophosphamide-induced rat model is superior to the 2-month-old model. The cyclophosphamide-induced LOH model has been widely used in the development and testing of various LOH treatments, such as compound SH379, active components of traditional Chinese medicine, herbal decoctions, and acupuncture.86,87,117,118 Animal model results align well with previous clinical findings, indicating strong predictive validity. However, since the modeling mechanism relies on cyclophosphamide’s reproductive toxicity to damage testicular tissue, it may also affect other reproductive organs and alter sex hormone levels, resulting in lower construct validity than natural aging or D-galactose-induced models.

Some studies use orchiectomy to establish animal models of LOH with testicular deficiency. The animals are derived from 16-month-old Wistar rats,89,90,119 3-month-old Sprague-Dawley rats,91 or 5-week-old ddY male mice.92 In orchidectomized LOH model animals, androgen production by the testes is completely blocked, leading to a sharp decline in serum testosterone levels.101 This replicates androgen deficiency-related manifestations such as reduced muscle mass, weight loss, seminal vesicle atrophy, and osteoporosis.89,92 Although testosterone levels drop sharply, they do not reach zero, suggesting compensatory androgen secretion from the adrenal glands.92 Furthermore, orchiectomy eliminates testicular T interference with the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis,89 making it useful for studying the effects of testosterone deficiency and TRT on HPA axis endocrine function.89

Orchiectomy is a simple and rapid procedure that successfully replicates androgen deficiency and related symptoms of LOH, demonstrating both face validity and construct validity. TRT proves effective in this model, indicating strong surface validity. Additionally, orchiectomy enables investigation into the presence of hypothalamic-pituitary dysfunction in hypogonadal rats, aiding in the identification of secondary hypogonadism.109

However, in theory, there should be minimal causal dissimilarity between the model and the target being modeled to avoid compromising the model’s validity.120,121

Although the castration-induced LOH model exhibits signs of androgen deficiency, removing the gonads during LOH modeling significantly reduces the model’s validity for the following reasons: (1) Most androgens are produced by the testes, with only a small amount derived from the adrenal glands. The core mechanism of LOH is attributed to age-related declines in Leydig cell numbers and their testosterone-secreting function. Therefore, when studying LOH—particularly primary LOH—preserving the testes of model animals is essential. (2) Male andropause develops gradually. Surgical gonadectomy leads to a sudden decline in sex hormones, making it unsuitable for simulating the chronic onset of male LOH. (3) The gonads contain various cell types, including Sertoli cells and spermatogenic cells, which produce multiple hormones and factors essential for maintaining systemic health. Gonad removal disrupts reproductive endocrine balance and severs the HPG axis feedback mechanism, fundamentally differing from the partial testicular function retained in men with LOH.

Hypoxia can lead to structural and functional damage in rat testes, including a reduction in Sertoli cell count and increased apoptosis. Additionally, related studies have shown that hypoxia reduces serum testosterone levels in patients, with more severe hypoxia correlating with a more pronounced decline in serum T levels. Therefore, Min93 proposed hypoxia as a risk factor for LOH. Based on this hypothesis, they established an LOH model using 10-month-old Sprague-Dawley rats subjected to chronic intermittent hypoxia. The “Attendor Animal Gas Control System” was employed with parameters set at a 12-min cycle: 7% O2 (hypoxia) for 7 min followed by normoxia (21% O2) for 5 min. Rats were exposed to this regimen for 4 h daily over 30 consecutive days. On day 30, the model group exhibited significantly lower serum TT and FT levels compared to the control group, along with markedly reduced forced swim test durations, decreased Leydig cell counts and increased apoptosis.

The strength of this model lies in its ability to replicate aging characteristics and hypoandrogenism in LOH, demonstrating good face validity and construct validity. However, the mortality rate in animal modeling reached 32%, which is relatively high. Hypoxia may impair brain, cardiopulmonary, and other organ functions, potentially interfering with experimental outcomes. Currently, validation of this model has been primarily limited to the original research team and efficacy assessments of certain traditional Chinese herbal formulations. There remains a lack of drug development or clinical research based on this model, and its predictive validity requires further verification.

Based on the negative feedback regulation of the HPG axis, sustained suppression of pituitary or testicular function can be achieved through the administration of hormonal drugs, resulting in decreased testosterone secretion. Currently, two main modeling methods are employed, including leuprolide and the combination of dihydrotestosterone and estradiol valerate.

2-month Sprague-Dawley rats were injected with a single subcutaneous dose of 0.5 mg/kg leuprolide, which can lead to androgen deprivation, simulating testosterone deficiency in LOH, and is suitable for drug screening tests.94 Compared to the normal control group, the seminiferous epithelium of the model rats became thinner, the number of 3β-HSD-positive Leydig cells decreased, and serum testosterone was significantly reduced.94 The advantage of this model lies in achieving androgen deprivation without reducing androgen levels to the low levels observed after orchiectomy; the histological changes in the testis tissue and the decreased testosterone synthesis function in the model rats to some extent mimic hypogonadism.94 However, the mechanism of this model involves a suppression of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis function by leuprolide, causing low levels of LH and T secretion, which is a secondary hypogonadism induced by drugs, not age-related. Therefore, this model has limited surface validity and construct validity in simulating LOH disorders. Although this model has been successfully applied to test the anti-LOH effects of the Korean herbal formula Ojayeonjonghwan (KH-204), there is still a need to consider the stability of the model and whether leuprolide could interfere with the screening tests of candidate drugs.

A subcutaneous injection of 9 mg/kg dihydrotestosterone and 0.9 mg/kg estradiol valerate (10:1) in 1-month Wistar rats, administered every other day for 28 days, can produce experimental postmenopausal syndrome rats with biochemical castration.95 The mechanism involves the administration of exogenous estradiol valerate, which achieves sustained suppression of pituitary function through negative feedback, leading to testicular dysfunction and decreased testosterone secretion.95 The concomitant use of dihydrotestosterone and estradiol valerate maintains appropriate levels of serum T and dihydrotestosterone to maintain physiological processes in rats.95 Telfairia Occidentalis Seed-incorporated Diet can improve the testosterone secretion capacity in the model rats and inhibit the reduction in testis weight,104 indicating that the experimental LOH model induced by estradiol valerate has potential for drug screening tests. The advantage of this rat model is its short experimental cycle and relatively low cost. However, like the previous model, this one also involves the use of drugs to interfere with pituitary function, presenting drug-induced secondary hypogonadism, unrelated to aging, with weak surface and construct validity. Furthermore, in the development of TRT-type LOH drugs, exogenous estradiol valerate may interfere with the treatment efficacy, affecting the model’s predictive validity.

Gene knockout models, which involve the specific knockout of a particular gene, allow for the study of the role of specific mechanisms in the pathogenesis of LOH. Due to the high technical requirements and significant cost associated with this method, as compared to natural aging or other intervention modeling methods, only two types are currently in use: the knockout of genes related to androgen receptors (AR) and the knockout of the CDGSH Iron Sulphur Domain 2 (Cisd2) gene, which is associated with redox processes.

The utilization of androgens in target tissues relies on the normal function of androgen receptors. With increased age, there is a decrease in tissue androgen receptors or a reduction in their sensitivity to androgens. A model of androgen insensitivity syndrome can be constructed by knocking out the androgen receptor gene. Currently, ARKO mouse models are primarily generated using the Cre-loxP conditional knockout strategy and categorized into multiple types based on targeted cell types, including Global Androgen Receptor Knockout Mice (Global ARKO mice), Sertoli Cell-selective ARKO Mice (SCARKO), and Leydig Cell-selective ARKO Mice (LCARKO). Compared to wild-type mice, all ARKO models exhibit reduced testicular volume, impaired or arrested spermatogenesis, and diminished reproductive capacity. Specifically, Global ARKO mice display feminized morphology, hypoactivity, obesity with lipid accumulation, decreased serum testosterone concentrations, and spermatogenesis arrested at pachytene spermatocytes;96,122,123 SCARKO mice maintain normal or slightly elevated postnatal serum testosterone levels but develop severe spermatogenic failure characterized by complete meiotic arrest at spermatogonia;124,125 LCARKO mice exhibit reduced testicular mass and seminiferous epithelium degeneration despite serum testosterone levels comparable to wild-type mice and normal spermatogenesis progression.126 This model can be used to study androgen-related and androgen resistance-related diseases and can partially mimic the phenotype of LOH, demonstrating certain surface validity. However, the reduction in androgen receptor expression or insensitivity in this model is due to abnormal androgen receptors caused by genetic deletion, which differs etiologically from the age-related androgen insensitivity in LOH, thus lowering its structural validity. Moreover, currently, there is a lack of surface validity verification for this model as an LOH model, which needs further validation in future experiments.

Cisd2 is an oxidoreductive activity protein located in the endoplasmic reticulum and is critical for maintaining the structure and function of the endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria.127 Cisd2 is closely associated with aging in mice, as its expression gradually decreases with age, and its deficiency leads to a suite of prematurely aging phenotypes.128 Overexpression of Cisd2, on the other hand, delays aging in mice.97,127 Studies have shown that at 6 months of age, the senescence “prematurely aging” model mice with structural Cisd2 gene knockout (CISD2-KO) exhibit signs of premature aging such as testicular atrophy, a decrease in the number of Leydig and Sertoli cells, reduced mRNA expression for steroidogenesis, decreased levels of circulating testosterone, and an increased luteinizing hormone/testosterone ratio, which are consistent with the model of primary testicular dysfunction in elderly men.127 The reduced levels of circulating testosterone in the CISD2-KO senescence mice are due to a decrease in the number of interstitial cells of the testis and a decrease in the steroidogenic function of these cells as a result of aging, and this model has certain surface and structural validity in simulating LOH diseases. Compared to naturally aged mice, the hormonal profiles of CISD2-KO mice may better reflect the state of the HPG axis in elderly men, providing a novel model resource for testing new therapeutic approaches aimed at reversing primary LOH.127

LOH is a convergence of aging and androgen deficiency, which is becoming increasingly prominent with the intensification of population aging trends. Among the existing LOH modeling methods, natural models more accurately reflect the pathological process of LOH and are currently the optimal animal model choice. Among them, Sprague-Dawley rats have been most extensively studied, while Brown Norway rats better align with the pathogenesis; However, aged animals are prone to additional illnesses, and the modeling process is lengthy, with a high cost of cultivation. Artificially induced models introduce additional interfering factors, resulting in lower construct and surface validity compared to natural ones. However, they generally offer advantages such as shorter modeling time, lower costs, and simpler procedures. In practical research, it is recommended to select different models based on the research objectives (Table 2). In the future, it is suggested that standardized criteria for the inclusion of androgens in various LOH animal models be established to enhance their similarity to clinical conditions. Based on the clinical classification of LOH, models should be divided into specific subtypes such as primary, secondary, compensatory, and mixed types, according to different levels of sex hormones. When using non-natural models for drug studies, it is advisable to incorporate the potential interference of the modeling method on study results to increase the reliability of experimental outcomes.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the Sichuan Provincial Science and Technology Department and the Sichuan Maternal and Child Health Association.

Funding Statement

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China Youth Science Fund Project, Grant No. 82205131; the Sichuan Provincial Science and Technology Department Youth Fund Project, Grant No. 2025ZNSFSC1798, and the Sichuan Provincial Maternal and Child Health Medical Science and Technology Innovation Project, Grant No. FXZD08.

Author Contributions

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Zheng Liu, Xuhong Yan. Funding acquisition: Liang Dong. Project administration: Jingyi Zhang. Supervision: Degui Chang, Xujun Yu, Liang Dong. Writing—original draft: Zheng Liu, Xuhong Yan, Guicheng Liu. Writing—review & editing: Jingyi Zhang, Degui Chang, Xujun Yu, Liang Dong. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials

Data availability is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Ethics Approval

No ethical issues are involved in this study, as we conducted no research on human or animal subjects, nor did we collect any personal or sensitive information.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Nieschlag E. Late-onset hypogonadism: a concept comes of age. Andrology 2020;8(6):1506–1511. doi:10.1111/andr.12719. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Zhou S-J, Zhao M-J, Yang Y-H et al. Age-related changes in serum reproductive hormone levels and prevalence of androgen deficiency in chinese community-dwelling middle-aged and aging men: two cross-sectional studies in the same population. Medicine 2020;99(1):e18605. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000018605. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Corona G, Goulis DG, Huhtaniemi I et al. European academy of andrology (EAA) guidelines on investigation, treatment and monitoring of functional hypogonadism in males: endorsing organization: european society of endocrinology. Andrology 2020;8(5):970–987. doi:10.1111/andr.12770. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Corona G, Maseroli E, Rastrelli G et al. Is late-onset hypogonadotropic hypogonadism a specific age-dependent disease, or merely an epiphenomenon caused by accumulating disease-burden? Minerva Endocrinol 2016;41:196–210. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

5. Grossmann M, Ng Tang Fui M, Cheung AS. Late-onset hypogonadism: metabolic impact. Andrology 2020;8(6):1519–1529. doi:10.1111/andr.12705. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Pye SR, Huhtaniemi IT, Finn JD et al. Late-onset hypogonadism and mortality in aging men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2014;99(4):1357–1366. doi:10.1210/jc.2013-2052. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Kim SH, Park JJ, Kim KH et al. Efficacy of testosterone replacement therapy for treating metabolic disturbances in late-onset hypogonadism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Urol Nephrol 2021;53(9):1733–1746. doi:10.1007/s11255-021-02876-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Yuan X, Xiong X, Xue J. Effect of testosterone replacement therapy on lower urinary tract symptoms: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Evidence-Based Med 2024;17(3):490–502. doi:10.1111/jebm.12628. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Xu Z, Chen X, Zhou H et al. An updated systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of testosterone replacement therapy on erectile function and prostate. Front Endocrinol 2024;15:1335146. doi:10.3389/fendo.2024.1335146. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Cruickshank M, Hudson J, Hernández R et al. The effects and safety of testosterone replacement therapy for men with hypogonadism: the TestES evidence synthesis and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess 2024;28:1–210. doi:10.3310/JRYT3981. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Wang W, Wu J, Fan Y-F et al. Testosterone replacement therapy improves metabolic indexes of the patients with hypogonadism: a meta-analysis. Zhonghua Nan Ke Xue = Natl J Androl 2022;28:926–934. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

12. Corona G, Rastrelli G, Sparano C et al. Cardiovascular safety of testosterone replacement therapy in men: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2024;23(5):565–579. doi:10.1080/14740338.2024.2337741. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Carpenter WR, Robinson WR, Godley PA. Getting over testosterone: postulating a fresh start for etiologic studies of prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2008;100(3):158–159. doi:10.1093/jnci/djm329. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. La Vignera S, Cannarella R, Garofalo V et al. Short-term impact of tirzepatide on metabolic hypogonadism and body composition in patients with obesity: a controlled pilot study. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2025;23(1):92. doi:10.1186/s12958-025-01425-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Jung S-J, Park E-O, Chae S-W et al. Effects of unripe black raspberry extract supplementation on male climacteric syndrome and voiding dysfunction: a pilot, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Nutrients 2023;15(15):3313. doi:10.3390/nu15153313. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Yamada S, Shirai M, Nagashima K, Mochizuki J, Ono K, Kageyama S. Beneficial effects of enoki mushroom extract on male menopausal symptoms in japanese subjects: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Nutrients 2025;17(7):1208. doi:10.3390/nu17071208. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Grossmann M. Indications for testosterone therapy in men. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 2024;31(6):249–256. doi:10.1097/MED.0000000000000890. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Tanji F, Kawajiri M, Nanbu H, Nishimoto D. Uneven impact of andropause symptoms on daily life domains in employed men: a cross-sectional study. J Occup Health 2025;67(1):uiaf040. doi:10.1093/joccuh/uiaf040. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Pechersky A. Features of diagnostics and treatment of partial androgen deficiency of aging men. Cent Eur J Urol 2014;67(4):397–404. doi:10.5173/ceju.2014.04.art16. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Dumbraveanu I, Arian I, Ghenciu V, Creciun M, Ceban E. Late-onset hypogonadism. Diagnostical and treatment landmarks. Public Health Econ Manag Med 2024;2024:140–146. doi:10.52556/2587-3873.2024.5(102).21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Rastrelli G, Forti G. Late-onset hypogonadism. In: Vitti P, Hegedus L, editors. Thyroid diseases. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2017; p. 1–23. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-29456-8_31-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Huhtaniemi I. Late-onset hypogonadism: current concepts and controversies of pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment. Asian J Androl 2014;16(2):192. doi:10.4103/1008-682X.122336. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Huhtaniemi IT, Wu FCW. Ageing male (part Ipathophysiology and diagnosis of functional hypogonadism. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2022;36(4):101622. doi:10.1016/j.beem.2022.101622. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Spaziani M, Carlomagno F, Tarantino C, Angelini F, Vincenzi L, Gianfrilli D. New perspectives in functional hypogonadotropic hypogonadism: beyond late onset hypogonadism. Front Endocrinol 2023;14:1184530. doi:10.3389/fendo.2023.1184530. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Basaria S. Reproductive aging in men. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2013;42(2):255–270. doi:10.1016/j.ecl.2013.02.012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Dakouane M, Bicchieray L, Bergere M, Albert M, Vialard F, Selva J. A histomorphometric and cytogenetic study of testis from men 29-102 years old. Fertil Steril 2005;83(4):923–928. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.12.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Petersen PM, Seierøe K, Pakkenberg B. The total number of leydig and sertoli cells in the testes of men across various age groups—a stereological study. J Anat 2015;226(2):175–179. doi:10.1111/joa.12261. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Zamoner A, Oliveira PF, Alves MG. Sertoli cell lysosomes and late-onset hypogonadism. Nat Aging 2024;4(5):618–620. doi:10.1038/s43587-024-00622-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Deng Z, Zhao L, Li S et al. Targeting dysregulated phago-/auto-lysosomes in sertoli cells to ameliorate late-onset hypogonadism. Nat Aging 2024;4(5):647–663. doi:10.1038/s43587-024-00614-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Gupta P,Singh RK, Suman A, Mahapatra A. Effect of endocrine disrupting chemicals on HPG axis: a reproductive endocrine homeostasis. In: Heshmati HM, editor. Hot topics in endocrinology and metabolism. Rijeka: IntechOpen; 2021. doi:10.5772/intechopen.96330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Clément F, Crépieux P, Yvinec R, Monniaux D. Mathematical modeling approaches of cellular endocrinology within the hypothalamo-pituitary-gonadal axis. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2020;518(590):110877. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2020.110877. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Millar RP, Newton CL. Analogues of hypothalamic/pituitary/gonadal hormone regulators for the management pubertal disorders. Curr Opin Endocr Metab Res 2020;14(1):169–178. doi:10.1016/j.coemr.2020.09.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Mattam U, Talari N, Thiriveedi V et al. Aging reduces kisspeptin receptor (GPR54) expression levels in the hypothalamus and extra-hypothalamic brain regions. Exp Ther Med 2021;22(3):1019. doi:10.3892/etm.2021.10451. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Anawalt BD, Matsumoto AM. Aging and androgens: physiology and clinical implications. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 2022;23(6):1123–1137. doi:10.1007/s11154-022-09765-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Wang Z, Wu W, Kim MS, Cai D. GnRH pulse frequency and irregularity play a role in male aging. Nat Aging 2021;1(10):904–918. doi:10.1038/s43587-021-00116-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Spindler M, Palombo M, Zhang H, Thiel CM. Dysfunction of the hypothalamic-pituitary adrenal axis and its influence on aging: the role of the hypothalamus. Sci Rep 2023;13(1):6866. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-33922-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Caputo M, Mele C, Ferrero A et al. Dynamic tests in pituitary endocrinology: pitfalls in interpretation during aging. Neuroendocrinology 2022;112(1):1–14. doi:10.1159/000514434. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Guo J, Huang X, Dou L et al. Aging and aging-related diseases: from molecular mechanisms to interventions and treatments. Signal Transduction Targeted Ther 2022;7(1):391. doi:10.1038/s41392-022-01251-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Deng X, Wang P, Yuan H. Epidemiology, risk factors across the spectrum of age-related metabolic diseases. J Trace Elem Med Biol 2020;61(Suppl. 1):126497. doi:10.1016/j.jtemb.2020.126497. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Singh J, Swain J, Sahoo DAK, Mangaraj S, Kanwar J. LBODP054 hypogonadism in diabetes mellitus: insulin resistance, the connecting link? J Endocr Soc 2022;6(Supplement_1):A273–A274. doi:10.1210/jendso/bvac150.564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Miller C, Madden-Doyle L, Jayasena C, McIlroy M, Sherlock M, O’Reilly MW. Mechanisms in endocrinology: hypogonadism and metabolic health in men—novel insights into pathophysiology. Eur J Endocrinol 2024;191(6):R1–R17. doi:10.1093/ejendo/lvae128. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Carrageta DF, Pereira SC, Ferreira R, Monteiro MP, Oliveira PF, Alves MG. Signatures of metabolic diseases on spermatogenesis and testicular metabolism. Nat Rev Urol 2024;21(8):477–494. doi:10.1038/s41585-024-00866-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Kaur KK, Allahbadia GN, Singh M. An update on primary adult hypogonadism in elderly males secondary to inflammaging: a narrative review. Open Access J Gynecol 2025;10(1):1–15. doi:10.23880/oajg-16000298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Xing D, Jin Y, Jin B. A narrative review on inflammaging and late-onset hypogonadism. Front Endocrinol 2024;15:1291389. doi:10.3389/fendo.2024.1291389. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. He F, Liu J, Huang Y et al. Nutritional load in post-prandial oxidative stress and the pathogeneses of diabetes mellitus. npj Sci Food 2024;8(1):41. doi:10.1038/s41538-024-00282-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Ishikawa K, Tsujimura A, Miyoshi M et al. Endocrinological and symptomatic characteristics of patients with late-onset hypogonadism classified by functional categories based on testosterone and luteinizing hormone levels. Int J Urol 2020;27(9):767–774. doi:10.1111/iju.14296. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. La Vignera S, Condorelli RA, Calogero AE et al. Symptomatic late-onset hypogonadism but normal total testosterone: the importance of testosterone annual decrease velocity. Ann Transl Med 2020;8(5):163. doi:10.21037/atm.2019.11.48. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Li H, Gu Y, Shang X et al. Decreased testosterone secretion index and free testosterone level with multiple symptoms for late-onset hypogonadism identification: a nationwide multicenter study with 5980 aging males in China. Aging 2020;12(24):26012–26028. doi:10.18632/aging.202227. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Isidori AM, Aversa A, Calogero A et al. Adult- and late-onset male hypogonadism: the clinical practice guidelines of the italian society of andrology and sexual medicine (SIAMS) and the italian society of endocrinology (SIE). J Endocrinol Invest 2022;45(12):2385–2403. doi:10.1007/s40618-022-01859-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Ventura-Aquino E, Paredes RG. Animal models in sexual medicine: the need and importance of studying sexual motivation. Sex Med Rev 2017;5(1):5–19. doi:10.1016/j.sxmr.2016.07.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Bialy M, Bogacki-Rychlik W, Przybylski J, Zera T. The sexual motivation of male rats as a tool in animal models of human health disorders. Front Behav Neurosci 2019;13:257. doi:10.3389/fnbeh.2019.00257. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Snyder PJ. Symptoms of late-onset hypogonadism in men. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2022;51(4):755–760. doi:10.1016/j.ecl.2022.04.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Amano T. Late-onset hypogonadism: current methods of clinical diagnosis and treatment in Japan. Asian J Androl 2025;27(4):447–453. doi:10.4103/aja2024111. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Zhou X, Zhou Q, Lai YJ. Establishment and evaluation of rat model of late onset hypogonadism of liver constraint and deficiency of kidney-type. J Hunan Univ Chin Med 2016;36:30–35. (In Chinese). doi:10.3969/j.issn.1674-070X.2016.03.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Gunes S, Hekim GNT, Arslan MA, Asci R. Effects of aging on the male reproductive system. J Assist Reprod Genet 2016;33(4):441–454. doi:10.1007/s10815-016-0663-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Santiago J, Silva JV, Alves MG, Oliveira PF, Fardilha M. Testicular aging: an overview of ultrastructural, cellular, and molecular alterations. J Gerontol A 2019;74(6):860–871. doi:10.1093/gerona/gly082. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Johnson L. Evaluation of the human testis and its age-related dysfunction. Prog Clin Biol Res 1989;302:35–60; discussion 61–67. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

58. Neaves WB, Johnson L, Porter JC, Parker CR, Petty CS. Leydig cell numbers, daily sperm production, and serum gonadotropin levels in aging men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1984;59(4):756–763. doi:10.1210/jcem-59-4-756. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Neaves WB. Age-related change in numbers of other interstitial cells in testes of adult men: evidence bearing on the fate of leydig cells lost with increasing age. Biol Reprod 1985;33(1):259–269. doi:10.1095/biolreprod33.1.259. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Honoré LH. Ageing changes in the human testis: a light-microscopic study. Gerontology 1978;24(1):58–65. doi:10.1159/000212237. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Paniagua R, Nistal M, Sáez FJ, Fraile B. Ultrastructure of the aging human testis. J Electron Microsc Tech 1991;19(2):241–260. doi:10.1002/jemt.1060190209. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Paniagua R, Amat P, Nistal M, Martin A. Ultrastructure of leydig cells in human ageing testes. J Anat 1986;146:173–183. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

63. Li W, Han B, Liu T et al. Changes in morphology and steroidogenic function of aged human leydig cells. Beijing Xue Xue Bao, Yi Xue Ban 2011;43:505–508. (In Chinese). doi:10.3969/j.issn.1671-167X.2011.04.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Regadera J, Nistal M, Paniagua R. Testis, epididymis, and spermatic cord in elderly men. Correlation of angiographic and histologic studies with systemic arteriosclerosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1985;109:663–667. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

65. Sasano N, Ichijo S. Vascular patterns of the human testis with special reference to its senile changes. Tohoku J Exp Med 1969;99(3):269–280. doi:10.1620/tjem.99.269. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Takizawa T, Hatakeyama S. Age-associated changes in microvasculature of human adult testis. Acta Pathol Jpn 1978;28(4):541–554. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1827.1978.tb00894.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Jiang H, Zhu W-J, Li J, Chen Q-J, Liang W-B, Gu Y-Q. Quantitative histological analysis and ultrastructure of the aging human testis. Int Urol Nephrol 2014;46(5):879–885. doi:10.1007/s11255-013-0610-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Johnson L, Petty CS, Neaves WB. Age-related variation in seminiferous tubules in men a stereologic evaluation. J Androl 1986;7(5):316–322. doi:10.1002/j.1939-4640.1986.tb00939.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Johnson L, Zane RS, Petty CS, Neaves WB. Quantification of the human sertoli cell population: its distribution, relation to germ cell numbers, and age-related Decline. Biol Reprod 1984;31(4):785–795. doi:10.1095/biolreprod31.4.785. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Tkacs NC, Thompson HJ. From bedside to bench and back again: research issues in animal models of human disease. Biol Res Nurs 2006;8(1):78–88. doi:10.1177/1099800406289717. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Varga OE, Hansen AK, Sandøe P, Olsson IAS. Validating animal models for preclinical research: a scientific and ethical discussion. Altern Lab Anim 2010;38(3):245–248. doi:10.1177/026119291003800309. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Noh Y-H, Kim D-H, Kim JY et al. Improvement of andropause symptoms by dandelion and rooibos extract complex CRS-10 in aging male. Nutr Res Pract 2012;6(6):505. doi:10.4162/nrp.2012.6.6.505. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Jung M-A, Oh K-N, Choi EJ et al. In vitro and in vivo androgen regulation of dendropanax morbiferus leaf extract on late-onset hypogonadism. Cell Mol Biol 2018;64(10):20–27. doi:10.14715/cmb/2018.64.10.4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Lee JY, Kim S, Kwon HO et al. The effect of a combination of eucommia ulmoides and achyranthes japonica on alleviation of testosterone deficiency in aged rat models. Nutrients 2022;14(16):3341. doi:10.3390/nu14163341. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Niu XZ, Zheng JH, Geng J et al. Animal experimental study of gonadal axis function changes in patients with male climacteric syndrome and the relationship with metabolic syndrome. J Clin Pathol Res 2015;35:603–608. (In Chinese). doi:10.3978/j.issn.2095-6959.2015.04.017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

76. Jin HQ, Jiang F, Deng DM, Chen WX, Yang GZ, Zhuang TQ. Regulatory effect of Bushenfang on the serum testosterone level of naturally aging rats and its mechanism. Natl J Andro 2011;17:758–762. (In Chinese). doi:10.13263/j.cnki.nja.2011.08.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

77. Choi SW, Jeon SH, Kwon EB et al. Effect of korean herbal formula (modified Ojayeonjonghwan) on androgen receptor expression in an aging rat model of late onset hypogonadism. World J Men’s Health 2019;37(1):105. doi:10.5534/wjmh.180051. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Zhang C, Xie Y, Chen H et al. FOXO4-DRI alleviates age-related testosterone secretion insufficiency by targeting senescent leydig cells in aged mice. Aging 2020;12(2):1272–1284. doi:10.18632/aging.102682. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

79. Wang C, Hikim AS, Ferrini M et al. Male reproductive ageing: using the brown norway rat as a model for man. Novartis Found Symp 2002;242:82–95. doi:10.1002/0470846542.ch6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

80. Flood JF, Farr SA, Kaiser FE, La Regina M, Morley JE. Age-related decrease of plasma testosterone in SAMP8 mice: replacement improves age-related impairment of learning and memory. Physiol Behav 1995;57(4):669–673. doi:10.1016/0031-9384(94)00318-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Zhao Y, Liu X, Qu Y et al. The roles of p38 MAPK→COX2 and NF-κB→COX2 signal pathways in age-related testosterone reduction. Sci Rep 2019;9(1):10556. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-46794-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

82. Aydin S, Yanar K, Cebe T, Erinc Sitar M, Belce A, Çakatay U. Galactose-induced aging model in rat testicular tissue. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak 2018;28(7):501–504. doi:10.29271/jcpsp.2018.07.501. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

83. He H. The association between androgen deficiency, obesity and lipid metabolism genes in males. Master’s thesis. Shanghai, China: Fudan University, 2012. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

84. Ahangarpour A, Oroojan AA, Heidari H. Effects of exendin-4 on male reproductive parameters of D-galactose induced aging mouse model. World J Men’s Health 2014;32(3):176. doi:10.5534/wjmh.2014.32.3.176. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

85. Zhang Z-B, Yang Q-T. The testosterone mimetic properties of icariin. Asian J Androl 2006;8(5):601–605. doi:10.1111/j.1745-7262.2006.00197.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

86. Zhang PH, Zhang CT, Yue ZX et al. Effect of jinkui shenqi pill on serum testosterone and leydig cell in partly androgen deficient rats. Chin J Surg Integr Tradit West Med 2008:388–391. (In Chinese). doi:10.3969/j.issn.1007-6948.2008.04.036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

87. Bai J, Xie J, Xing Y et al. Synthesis and biological evaluation of methylpyrimidine-fused tricyclic diterpene analogs as novel oral anti-late-onset hypogonadism agents. Eur J Med Chem 2019;176:21–40. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.05.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

88. Ren Y, Yang X, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Li X. Effects and mechanisms of acupuncture and moxibustion on reproductive endocrine function in male rats with partial androgen deficiency. Acupunct Med 2016;34(2):136–143. doi:10.1136/acupmed-2014-010734. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

89. Ajdžanović V, Jarić I, Živanović J et al. Testosterone application decreases the capacity for ACTH and corticosterone secretion in a rat model of the andropause. Acta Histochem 2015;117(6):528–535. doi:10.1016/j.acthis.2015.04.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

90. Ajdzanovic VZ, Sosic-Jurjevic WJ, Filipović BR, Trifunovic SL, Milosevic VL. Daidzein effects on ACTH cells: immunohistomorphometric and hormonal study in an animal model of the andropause. Histol Histopathol 2011;26:1257–1264. doi:10.14670/HH-26.1257. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

91. Jang H, Bae WJ, Kim SJ et al. The effect of anthocyanin on the prostate in an andropause animal model: rapid prostatic cell death by apoptosis is partially prevented by anthocyanin supplementation. World J Men’s Health 2013;31(3):239. doi:10.5534/wjmh.2013.31.3.239. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

92. Michihara S, Shin N, Watanabe S, Morimoto Y, Okubo T, Norimoto H. A Kampo formula, saikokaryukotsuboreito, improves serum testosterone levels of castrated mice and its possible mechanism. Aging Male 2013;16(1):17–21. doi:10.3109/13685538.2012.755507. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

93. Min X. Study on the mechanism of Yijing Decoction regulating Leydig cell apoptosis induced by chronic hypoxia in the treatment of LOH. Doctoral dissertation. Beijing, China: China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences, 2021. (In Chinese). doi:10.27658/d.cnki.gzzyy.2020.000064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

94. Bae WJ, Zhu GQ, Choi SW et al. Antioxidant and antifibrotic effect of a herbal formulation in vitro and in the experimental andropause via Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway. Oxid Med Cell Longevity 2017;2017(1):6024839. doi:10.1155/2017/6024839. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

95. Ejike C, Ezeanyika L. A telfairia occidentalis seed-incorporated diet may be useful in inhibiting the induction of experimental andropause. Ann Med Health Sci Res 2012;2(1):41. doi:10.4103/2141-9248.96936. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

96. Yeh S, Tsai M-Y, Xu Q et al. Generation and characterization of androgen receptor knockout (ARKO) mice: an in vivo model for the study of androgen functions in selective tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2002;99(21):13498–13503. doi:10.1073/pnas.212474399. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

97. Wu C-Y, Chen Y-F, Wang C-H et al. A persistent level of Cisd2 extends healthy lifespan and delays aging in mice. Hum Mol Genet 2012;21(18):3956–3968. doi:10.1093/hmg/dds210. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

98. Sengupta P. The laboratory rat: relating its age with human’s. Int J Prev Med 2013;4:624–630. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

99. Andreollo NA, Santos EFD, Araújo MR, Lopes LR. Idade dos ratos versus idade humana: qual é a relação? ABCD Arq Bras Cir Dig 2012;25(1):49–51. doi:10.1590/S0102-67202012000100011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

100. Dutta S, Sengupta P. Men and mice: relating their ages. Life Sci 2016;152:244–248. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2015.10.025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

101. Tian YY, Li BN, Zhou HL, Zhou Q, Zhou X, Xing JP. Improving effect of Jiarong Tablets on the morphological structure and function of the testis in rats with late-onset hypogonadism. Zhonghua Nan Ke Xue 2020;26:237–241. (In Chinese). doi:10.13263/j.cnki.nja.2020.03.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

102. Jeong HC, Jeon SH, Guan Qun Z et al. Lycium Chinense mill improves hypogonadism via anti-oxidative stress and anti-apoptotic effect in old aged rat model. Aging Male 2020;23(4):287–296. doi:10.1080/13685538.2018.1498079. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

103. Abdelhamed A, Hisasue S, Shirai M et al. Testosterone replacement alters the cell size in visceral fat but not in subcutaneous fat in hypogonadal aged male rats as a late-onset hypogonadism animal model. Res Rep Urol 2015;7:35. doi:10.2147/RRU.S72253. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

104. Zhou X, Li BN, Zhou HL et al. Xiongcan Yishen Prescription up-regulates the expressions of cholesterol transport proteins, steroidogenic enzymes and SF-1 in the Leydig cells of rats with late-onset hypogonadism. Zhonghua Nan Ke Xue 2020;26:258–264. (In Chinese). doi:10.13263/j.cnki.nja.2020.03.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

105. Tang X, Li BN, Zhou HL et al. Study on the effects of xiongcan yishen recipe on the histomorphology and antioxidation of testes in rats with late onset hypogonadism. J Hunan Univ Chin Med 2020;40:951–956. (In Chinese). doi:10.3969/j.issn.1674-070X.2020.08.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

106. Wu M, Hao BJ, Liang WN, Li YZ, Geng Q, Shang XJ. Jiarong tablets combined with testosterone undecanoate capsules for late-onset hypogonadism in males: a multicentered clinical trial. Zhonghua Nan Ke Xue 2020;26:346–350. (In Chinese). doi:10.13263/j.cnki.nja.2020.04.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

107. Zang ZJ, Ji SY, Dong W, Zhang YN, Zhang EH, Bin Z. A herbal medicine, saikokaryukotsuboreito, improves serum testosterone levels and affects sexual behavior in old male mice. Aging Male 2015;18(2):106–111. doi:10.3109/13685538.2014.963042. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

108. Zang Z-J, Tang H-F, Tuo Y et al. Effects of velvet antler polypeptide on sexual behavior and testosterone synthesis in aging male mice. Asian J Androl 2016;18(4):613. doi:10.4103/1008-682X.166435. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

109. Gruenewald DA, Naai MA, Hess DL, Matsumoto AM. The brown norway rat as a model of male reproductive aging: evidence for both primary and secondary testicular failure. J Gerontol 1994;49(2):B42–B50. doi:10.1093/geronj/49.2.B42. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

110. Chen H, Guo J, Ge R, Lian Q, Papadopoulos V, Zirkin BR. Steroidogenic fate of the leydig cells that repopulate the testes of young and aged brown norway rats after elimination of the preexisting leydig cells. Exp Gerontol 2015;72:8–15. doi:10.1016/j.exger.2015.08.014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

111. Zirkin BR, Santulli R, Strandberg JD, Wright WW, Ewing LL. Testicular steroidogenesis in the aging brown norway rat. J Androl 1993;14(2):118–123. doi:10.1002/j.1939-4640.1993.tb01663.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

112. Yan XH. Study on the intervention effect of Qiangjing Pills on androgen and ROS/FOXO4-p53 signal in compensated LOH model rats and senile Leydig cells. Doctoral dissertation. Chengdu, China: Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 2022. (In Chinese). doi:10.26988/d.cnki.gcdzu.2021.000055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

113. Flood JF, Morley JE. Age-related changes in footshock avoidance acquisition and retention in senescence accelerated mouse (SAM). Neurobiol Aging 1993;14(2):153–157. doi:10.1016/0197-4580(93)90091-O. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

114. Luo J, Yang Y, Zhang T et al. Nasal delivery of nerve growth factor rescue hypogonadism by up-regulating GnRH and testosterone in aging male mice. eBioMedicine 2018;35(3):295–306. doi:10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.08.021. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

115. Liao C-H, Chen B-H, Chiang H-S et al. Optimizing a male reproductive aging mouse model by d-galactose injection. Int J Mol Sci 2016;17(1):98. doi:10.3390/ijms17010098. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

116. Ghobadi E, Moloudizargari M, Asghari MH, Abdollahi M. The mechanisms of cyclophosphamide-induced testicular toxicity and the protective agents. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol 2017;13(5):525–536. doi:10.1080/17425255.2017.1277205. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

117. Zhang PH, Yue MQ, Cai J et al. Effect of jingkui shenqi pill on serum testosterone(T) and the activity expression of 3β-HSD of rats with partial androgen deficiency. Chin J Androl 2010;24:33–35. (In Chinese). doi:10.3969/j.issn.1008-0848.2010.03.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

118. Wu TL, Zhang PH, Zhong Q et al. The effect of jinguishenqi pill on the level of serum testosterone and mRNA expression of StAR in partial androgen deficiency rats. Chin J Androl 2009;23:28–30. (In Chinese). doi:10.3969/j.issn.1008-0848.2009.02.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

119. Šošić-Jurjević B, Filipović B, Renko K et al. Testosterone and estradiol treatments differently affect pituitary-thyroid axis and liver deiodinase 1 activity in orchidectomized middle-aged rats. Exp Gerontol 2015;72:85–98. doi:10.1016/j.exger.2015.09.010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

120. Shelley C. Why test animals to treat humans? On the validity of animal models. Stud Hist Philos Sci C Stud Hist Philos Biol Biomed Sci 2010;41(3):292–299. doi:10.1016/j.shpsc.2010.07.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

121. Shapiro KJ. Animal model research: the apples and oranges quandary. Altern Lab Anim 2004;32(1_suppl):405–409. doi:10.1177/026119290403201s66. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

122. Rana K, Fam BC, Clarke MV, Pang TPS, Zajac JD, MacLean HE. Increased adiposity in DNA binding-dependent androgen receptor knockout male mice associated with decreased voluntary activity and not insulin resistance. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2011;301(5):E767–E778. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.00584.2010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

123. Yanase T, Fan W, Kyoya K et al. Androgens and metabolic syndrome: lessons from androgen receptor knock out (ARKO) mice. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2008;109(3–5):254–257. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2008.03.017. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

124. Tan KAL, De Gendt K, Atanassova N et al. The role of androgens in sertoli cell proliferation and functional maturation: studies in mice with total or sertoli cell-selective ablation of the androgen receptor. Endocrinology 2005;146(6):2674–2683. doi:10.1210/en.2004-1630. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

125. Willems A, Batlouni SR, Esnal A et al. Selective ablation of the androgen receptor in mouse sertoli cells affects sertoli cell maturation, barrier formation and cytoskeletal development. PLoS One 2010;5(11):e14168. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0014168. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

126. O’Hara L, McInnes K, Simitsidellis I et al. Autocrine androgen action is essential for leydig cell maturation and function, and protects against late-onset leydig cell apoptosis in both mice and men. FASEB J 2015;29(3):894–910. doi:10.1096/fj.14-255729. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

127. Curley M, Milne L, Smith S et al. A young testicular microenvironment protects leydig cells against age-related dysfunction in a mouse model of premature aging. FASEB J 2019;33(1):978–995. doi:10.1096/fj.201800612R. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

128. Chen Y-F, Kao C-H, Chen Y-T et al. Cisd2 deficiency drives premature aging and causes mitochondria-mediated defects in mice. Genes Dev 2009;23(10):1183–1194. doi:10.1101/gad.1779509. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools