Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Adult urologic sarcomas: a single institution experience over 25 years

1 Division of Hematology and Medical Oncology, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, NY 10021, USA

2 Department of Internal Medicine-Hematology, Oncology and Blood and Marrow Transplantation, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA 52242, USA

3 Department of Urology, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA 52242, USA

* Corresponding Author: Michael A. O’Donnell. Email:

Canadian Journal of Urology 2025, 32(6), 605-620. https://doi.org/10.32604/cju.2025.063632

Received 20 January 2025; Accepted 29 April 2025; Issue published 30 December 2025

Abstract

Background: Genitourinary (GU) sarcomas are rare soft tissue malignancies, comprising around 2% of all GU cancers. Due to their rarity, limited data exist on optimal management and long-term outcomes. This study presents a 25-year single-institution experience, evaluating clinical presentation, treatment strategies, and survival outcomes, aims to identify trends over time and potential predictors of prognosis. Methods: A retrospective review was conducted of patients aged ≥18 years diagnosed with GU sarcomas at the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics (1998–2023). Data on tumor subtype, staging, histopathology, treatment modalities, and survival outcomes were analyzed. Kaplan-Meier analysis estimated recurrence-free survival (RFS) and overall survival (OS). Results: Among 33 cases, the most common presentations in order of frequency were liposarcoma (LPS) (n = 15), leiomyosarcoma (LMS) (n = 12), rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) (n = 5), and angiosarcoma (n = 1). Paratesticular tumors (n = 23) were most frequent, followed by bladder (n = 5), prostate (n = 2), and kidney (n = 2). The median age was 51 for LMS, 60 for LPS, and 24 for RMS. LMS had higher stage (66.67%), grade (83.33%), recurrence (25.00%), and mortality (41.67%) rates compared to LPS (recurrence: 13.33%, mortality: 20.00%). At 36 months, RFS was 63% (95% CI: 39%–79%), and OS was 81% (95% CI: 57%–92%) for the entire cohort. Follow-up duration was 19.9 months for LMS and 33.8 months for LPS. Conclusion: Surgical resection remains the mainstay of treatment for GU sarcomas. Margin status, tumor grade, and size are key prognostic factors. LMS carries the highest recurrence risk, and RMS exhibits aggressive progression. Further investigation into targeted therapies is warranted to improve outcomes.Keywords

Genitourinary (GU) sarcomas are rare soft tissue malignancies originating from embryonic mesoderm, comprising around 2% of all genitourinary malignancies.1 Among the sarcomas affecting the GU tract, the majority are leiomyosarcomas (LMS), liposarcomas (LPS), rhabdomyosarcomas (RMS), and carcinosarcomas. Rare subtypes include clear cell sarcoma, fibrosarcoma, dermatofibrosarcoma, angiosarcoma, malignant fibrous histiocytoma, and undifferentiated sarcoma.1,2 Due to the rarity of GU sarcomas, few studies regarding management have been published to date. The largest series, using the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) 18 database study, was comprised of 3007 patients.2 Another notable series was reported from Memorial Sloan Kettering Centre which included a sample size of 43.1 There have also been studies reported outside the US, such as in Italy (sample size 22),3 China (sample size 188),4 Korea (sample size 18)5 and Japan (sample size 155).6 These studies mainly focused on the overall survival (OS), margins, grades, prognosis and recurrence, focusing on statistically significant factors.

Our study is a descriptive study outlining the experiences in our institution, aiming to provide a glance into unexplored aspects of adult GU sarcomas. A critical area of interest is the long-term follow-up data on different sarcoma subtypes treated with surgical resection in combination with various therapeutic modalities. Understanding the impact of these multimodal treatment strategies on OS, disease-free survival, and recurrence rates is essential for optimizing patient outcomes. The treatment landscape for sarcomas is rapidly evolving, driven by advancements in diagnostics such as next-generation sequencing (NGS) and comprehensive genomic profiling. These technologies help identify genetic alterations in TP53, RB1, and ATRX, as well as actionable mutations and fusion genes in ALK and NTRK. Additionally, tumors can be evaluated for the expression of specific markers like PD-L1, enabling the potential for more targeted and personalized therapy options. Thus, in our paper we have highlighted the immunohistochemistry staining status of different GU sarcomas and explored their potential associations with clinical outcomes.

After gathering proper approval from the University of Iowa Human Subjects Office Institutional Review Board-1 (IRB-1) under Genitourinary Retrospective Umbrella Projects Institutional Review Board (IRB) (Approval number 201404766), the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics (UIHC) Electronic Medical Records (EMR) from the years 1998–2023 were queried for GU sarcomas in patients aged 18 and above, involving the prostate, bladder, kidneys, and paratesticular region. Gynecological and retroperitoneal sarcomas were excluded from the search.

Pathologic grading and staging

All sarcomas were reviewed by specialized soft-tissue pathologists at the University of Iowa. Sarcomas were categorized into different subtypes based on the predominant tissue type, microscopic features of cellular and nuclear pleomorphism, and immunohistochemistry stains. Grading of the tumor was done based on the Fédération Nationale des Centres de Lutte Contre le Cancer (FNCLCC) grading into a low grade (G1), intermediate grade (G2), or high grade (G3). The FNCLCC system is based on 3 factors: degree of differentiation, mitotic count, and tumor necrosis, with each factor being assigned a score of 1 to 3. The sarcomas were staged in accordance with the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Tumor Node Metastasis (TNM) system for soft tissue sarcomas. Detailed tumor characteristics are provided in Table 1.

Survival probabilities were estimated and plotted using the Kaplan-Meier (K-M) method. Estimates along with 95% pointwise confidence intervals (CIs) were reported. Recurrence-free survival (RFS) was defined as the time from when the patient was disease-free to recurrence. Otherwise, patients were censored at the last disease evaluation. Patients still alive were censored at the last known point of being alive, non-cancer-related deaths were also counted as a censoring event. Using this data, descriptive tables (Tables 2 and 3) were generated, and univariate analysis of different risk factors was performed. Due to the small sample size, further subgroup analysis on RFS and OS could not be done. Neither was it possible to do a multivariate analysis of the risk factors affecting prognosis. All statistical tests were performed using SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) software.

There were 4 types of sarcomas in this patient cohort with the commonest being LPS and LMS, other subtypes include RMS and angiomyosarcoma. There were 12 reported cases of LMS, 15 cases of LPS, 5 cases of RMS (with 3 alveolar subtypes), and 1 angiosarcoma. Based on the site of origin, the most frequent location of origin/organ system involvement, was paratesticular (n = 23), bladder (n = 5), prostate (n = 2) and kidney (n = 2), prostatic urethra (n = 1). Among the LPS 7 were well differentiated and 8 were de-differentiated.

Median age for diagnosis was 51 years (range: 21–79) for LMS, 60 years (range: 36–89) for LPS, 24 years (range: 20–71) for RMS. The median tumor size for LPS was 8.7 cm (range: 3.0–17.3 cm) in the greatest dimension compared to 5 cm (range: 1.2–15.0 cm) for LMS, and 5.0 cm (range: 4.2–10.3 cm) for RMS.

LMS tended to have a higher grade on diagnosis (intermediate and high grade: n = 10, 83.33% of total vs. n = 8/15, 53.33% for LPS). Two patients with LPS developed recurrent disease after resection of a presumed lipoma.

Presentation and treatment based on tumor types

All patients underwent surgical resection with curative intent (see Table 1 for detailed surgical approaches). Surgical resections were classified as macroscopically complete (R0 and R1) or incomplete (R2), and all macroscopically complete resections were further classified according to whether the margins were positive (R1) or negative (R0). Patients were treated according to the opinion of the institutional multidisciplinary tumor board. 27 patients (81.81%) achieved R0 status after initial surgery. The remaining 6 patients (GU-09, 17, 21, 27, 32, 33; 4 of whom subsequently died) had R1 status (microscopically positive margins). Three (50.00%) of these (GU-21, 32, 33) underwent repeat surgery to achieve R0 status where histopathology yielded residual sarcoma. Following surgery, 4 patients (GU-1, 17, 25, 29) were treated with adjuvant radiotherapy and 3 were treated with adjuvant chemotherapy (GU-09, 14, 16); 2 patients received both adjuvant chemo-radiotherapy (GU-15, 33). It should be noted that 2 patients also received neoadjuvant chemotherapy for downstaging of the sarcoma prior to surgery (GU-14, 17). 4 patients presented with metastatic disease (GU-9, 13, 15, 17), and 6 had regional lymph node (GU-9, 15, 17, 27, 29, 33) involvement at the time of initial diagnosis. Among them, the most numerous were paratesticular sarcomas (n = 23) often presented as an inguinoscrotal lump that was often mistaken for hernia or hydrocele, scrotal mass, recurrent scrotal swelling, or first noticed after blunt trauma, thus requiring a 2nd look surgery for oncologic margins (n = 17, 73.91%). 2 cases were recurrent despite complete resection with negative margins, with 1 being locally recurrent (GU-18) and another progressing to disseminated intraperitoneal metastatic disease (GU-32) leading to death. For more detailed treatments and outcomes see Table 1.

Based on tumor subtypes:

GU-15 is a case of paratesticular RMS case that presented with osseous metastatic disease. The patient underwent surgical resection, adjuvant VAC chemotherapy (vincristine, actinomycin D, cyclophosphamide), radiotherapy, and autologous bone marrow transplant, resulting in remission, with no evidence of disease. GU-33 presented with alveolar RMS (negative for fusion transcripts on genetic testing) and had rapidly progressive disease despite surgery and chemotherapy. GU-16 with T1N0M0 embryonal RMS was treated with radical orchiectomy and adjuvant chemotherapy (4 cycles of VAC), with an uneventful follow-up.

There were two cases of embryonal RMS (GU-14, 17) involving the prostate. All the cases presented with lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) and dysuria in a younger patient group (<25 years), however, LMS solely presented with obstructive symptoms whereas RMS had both obstructive symptoms (GU-14, 17) and hematuria (GU-14). Both GU-01 and GU-14 were initially attempted resection via transurethral approach, but ultimately required transition to a surgical resection followed by adjuvant radiotherapy for LMS and neoadjuvant chemotherapy VDC (Vincristine, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide) and extended pelvic lymph node dissection for the RMS. The patient with RMS developed lung metastases after 2 years of treatment, and subsequently underwent pneumonectomy and chemotherapy (VDC/IE) (IE, ifosfamide and etoposide). The patient’s disease recurred 1.5 years later and was treated with further palliative chemotherapy, but the patient subsequently died.

Bladder LMS (n = 5) presented with LUTS in four cases, hematuria or incidentally on imaging (GU-03; Computed Tomography (CT): as a mass on the outer wall with normal cystoscopy) due to pelvic pain. The majority n = 3 (60.00%) were stage III and high-grade tumors. There was one low-grade T1 LMS (GU-03) which was treated with partial cystectomy, the rest were treated with radical cystectomy and pelvic lymph node dissection.

T2N0M0G3 renal LMS (GU-08) presenting with a perinephric hematoma. The patient underwent a right nephrectomy and robotic retroperitoneal lymph node dissection. However, the patient passed 1 year later due to post-operative complications of chylous ascites; the patient had no evidence of malignancy upon her death.

In 13 cases (86.67%), LPS (out of total 15 cases) was found incidentally after surgery for presumed lipoma encompassing the spermatic cord. These cases required 2nd look surgery (typically radical hemicolectomy with orchiectomy and high ligation of the spermatic cord) with the aim of achieving microscopically cancer-free margins. A residual focus of tumor was identified in n = 6 (46.15%) cases. A total of n = 4 (30.76%) of cases had proximal margins of the resected specimens positive for tumor with n = 2 (15.38%) cases being positive for tumor even after 2nd look surgery. In select high-grade or T3 cases of LPS, a robotic retroperitoneal lymph node dissection was performed (n = 3, 23.07%) to rule out metastatic nodal spread. In all cases, the lymph nodes were negative on histopathology.

There was a case of T3N1M1G3 angiosarcoma (GU-09; hilar, retroperitoneal, and para-aortic metastasis) which was treated with left radical nephrectomy, adrenalectomy and retroperitoneal lymph node dissection as cytoreductive surgery and subsequently treated with systemic chemotherapy for control of her metastatic disease. At the last follow-up, the patient was admitted to hospice care 2.5 years post-treatment and subsequently was lost to follow-up.

Immunohistochemistry and testing for different markers and chromosomal abnormalities were performed on most, but not all, GU sarcomas. The staining details are provided in Table 1. Most LPS were assessed using fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) for the presence of MDM2 and other amplifications. Among the 16 total cases, 8 were positive for MDM2, 1 was equivocal, 2 were negative and in cases, FISH was not done. Other amplifications detected included CDK4 in 4 cases. The single case of alveolar RMS tested negative for fusion transcript. Most LMS tested positive for the presence of smooth muscle actin and myosin and negative for other markers including CK5/6, CD45, CD34, and CD 117 (details in Table 1).

During the median follow-up period of 19.9 months (range: 0.1–103.1) for LMS, 3 patients developed the metastatic disease (GU-05, 06, and 10: metastasis to pleura, lungs, and liver; Table 1), compared to 2 cases of LPS recurring (GU-18: recurring locally; GU-32: recurring as disseminated peritoneal disease) over a follow-up period of 32.1 months (range: 2.9–119.8) and 1 recurrent case of RMS (GU-14: metastasis to lung) over a median follow-up period of 93.4 months (range: 25.8–172.0). Using K-M analysis, the RFS at 12, 24, and 36 months was 91% (95% CI: 70%–98%), 83% (95% CI: 60%–93%) and 63% (95% CI: 39%–79%), respectively (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1. Recurrence-free survival (RFS) at 12, 24, and 36 months

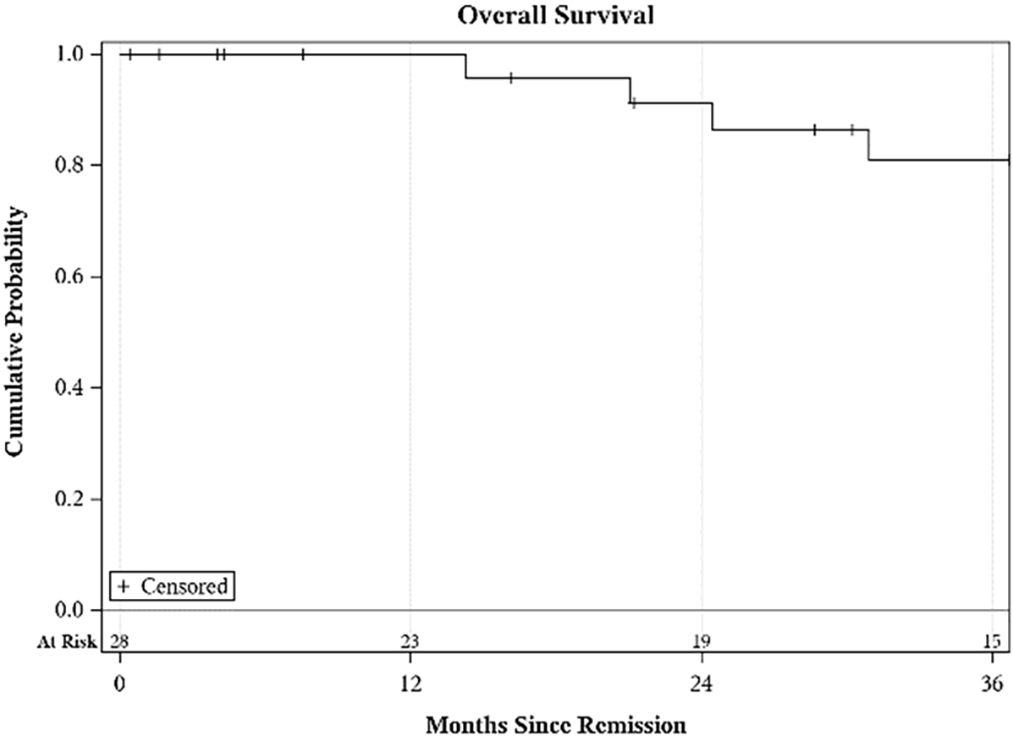

Among patients with no metastatic disease or lymph node spread at presentation, 6 patients (n = 6 out of 26, 23.07%) died. Four had prior LMS and 1 each had RMS and LPS. Among patients who went into remission, i.e., no residual disease radiologically post-treatment, 27.58% died (n = 8/29). By KM analysis, the OS at 12, 24, and 36 months was 100%, 91% (95% CI: 69%–98%), and 81% (95% CI: 57%–92%), respectively (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2. Overall survival (OS) at 12, 24, and 36 months

4 patients had metastatic disease and 3 had lymph node involvement on presentation. Disease did not go into remission, i.e., macroscopic disease is still present or distant metastasis present in 4 patients (GU-09, 13, 17, 33). Among these patients, 3 patients died and 1 was in hospice (GU-09) 2.5 years after treatment on the last follow-up.

Paratesticular soft tissue sarcomas can arise from the epididymis, and mesenchymal layers surrounding the testis and the spermatic cord.5 LPS are the most common tumors (64%) of the paratesticular region,2 often presenting as a nonreducible painless inguinal lump.7 In line with our series, other studies have also reported unplanned hernia surgery in 20.1% of cases (compared to n = 17/33, 50% cases) for spermatic cord sarcomas necessitating additional oncologic surgery.7 Local recurrence is a common occurrence for paratesticular tumors as circumferential negative resection margins are difficult to achieve, with one study reporting an actuarial local recurrence rate of 30% at 10 years and 42% at 15 years when surgery is the sole treatment modality.8 There exist two approaches to resection, simple tumorectomy vs. high inguinal resection. High inguinal resection offers better outcomes in terms of needing re-resection in the subcutaneous variant.9 Thus, it has been adopted as the standard of care. For the one local recurrence of dedifferentiated intermediate grade LPS, pembrolizumab, salvage radiotherapy, and repeat surgery were performed. Although the inked margins were positive after repeat resection, CT shows no evidence of local recurrence or metastasis at 36 months follow-up.

While the presence of MDM2 and CDK4 amplifications suggests a more aggressive clinical course due to their role in uncontrolled cell cycle progression and inhibition of tumor suppressor pathways, they also present potential pathways for targeted therapies. Currently, palbociclib a CK4/6 inhibitor shows the most promising results with a phase 2 trial demonstrating 12 weeks Progression Free Survival (PFS) of 66% in advanced dedifferentiated LPS.10 Another notable clinical trial NCT02343172 is currently assessing the efficacy of an MDM2 inhibitor siremadlin in combination with a CDK4 inhibitor ribociclib in patients with advanced dedifferentiated liposarcoma (DDLPS).11

Although RMS do tend to present in the pediatric age group, they can also present in adult patients accounting for 2%–5% of adult soft tissue tumors. Among the subtypes of RMS, the embryonal subtype is the more commonly found accounting for 60% of all RMS, with a favorable prognosis.12 This contrasts with the less common alveolar variant (accounting for 20%–30% of all RMS cases), which may harbor chromosomal translocations involving the FOXO1 gene, such as the PAX3-FOXO1 fusion (t [2;13]) or the PAX7-FOXO1 fusion (t [1;13]) which have a more aggressive clinical course and a worse prognosis.13 The presence of the PAX3/FOX01 gene fusion in alveolar RMS is associated with a worse prognosis, having a 5-year OS of 7% in fusion-positive vs. 69% in fusion negative.12,14 In a SEER database study, the 1- and 5-year OS for prostate RMS was 76.2% (51.9%–89.3%) and 33.0% (12.8%–55.0%), respectively.15 Prognostic factors for RMS include older age (>21 years) or the presence of distal metastasis at presentation. Interestingly, the site of tumor origin is not associated with disease-specific overall survival.16 Treatment of adult patients with non-metastatic RMS with prospective RMS protocols has been shown to improve 3-year, 4-year, and 5-year survival, with survival rates approaching that of pediatric RMS.17

Adjuvant radiation has been shown to be beneficial for the treatment of alveolar RMS with microscopic positive margins. For paratesticular tumors, ipsilateral retroperitoneal lymph node dissection (RPLND) is recommended, and Lymph node (LN)-positive disease should be followed up by radiotherapy to the para-aortic chain.18 For RMS of prostate/bladder, while cystoprostatectomy may achieve local control, the high rate of rectal and urinary dysfunction makes neoadjuvant radiotherapy an attractive choice in unresectable disease, which if followed by resection can result in acceptable urinary and bowel function.19

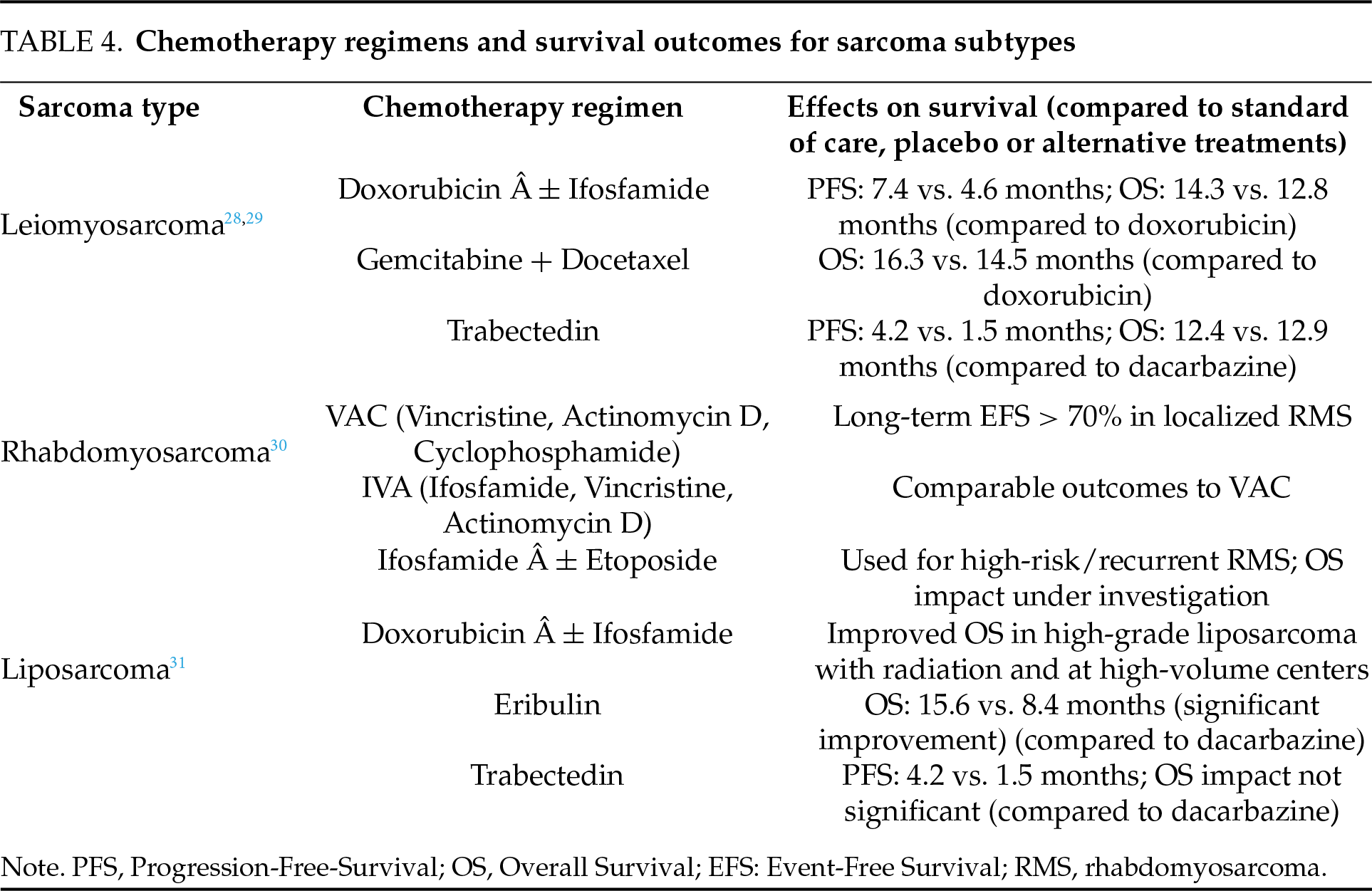

Predictors for decreased cancer-specific survival (CSS) of LMS include increased patient age (with patients >60 years having a dramatic decrease in median survival20), size (>5 cm as an independent prognostic factor for disease),21 absence of cancer-directed surgery, and the presence of distant metastasis. While standard treatment for large LMS of the bladder is radical cystectomy, smaller tumors can be managed with partial cystectomy or even transurethral resection for bladder tumor (TURBT).20 There are few case reports in the literature that mention smaller LMS (<4 cm) managed with partial cystectomy with no adverse oncologic outcomes.22 While there may be local recurrence (lower Disease Specific Survival (DSS)) when tumors are managed with TURBT, there are no long-term differences in survival compared to cystectomy.20 For advanced or metastatic LMS and LPS 1st line treatment is chemotherapy with doxorubicin alone or combination doxorubicin-ifosfamide therapy, doxorubicin is the standard first-line therapy with no other combinations yielding superior results.23,24 In patients previously treated with anthracyclines, a combination of trabectedin with doxorubicin is recommended as 2nd line therapy. LMS-04, a phase 3 randomized controlled trial (RCT), evaluated the efficacy of current 1st line doxorubicin against a combination of doxorubicin and trabectedin for metastatic LMS with the highest reported PFS (12.2 months, 95% CI: 10.1–15.6) in adult Soft Tissue Sarcoma (STS) till date.25 Immunotherapy has yielded limited and conflicting results in the treatment of metastatic LMS with an Overall Response Rate (ORR) of 0.10 (95% CI: 0.06–0.17) and LPS (ORR: 0.11, 95% CI: 0.07–0.17) in a meta-analysis, with current recommendations placing them at 2nd or 3rd line therapy in certain situations.26 Other newer therapies include pazopanib, a multi-kinase inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR), platelet-derived growth factor inhibitor (PDGFi), and Cluster of Differentiation CD 117 which has been shown to improve PFS in STS including LMS in a Phase III trial (NCT00753688)27 (see Table 4 for the role of chemotherapy regimens in LMS, LPS, and RMS).

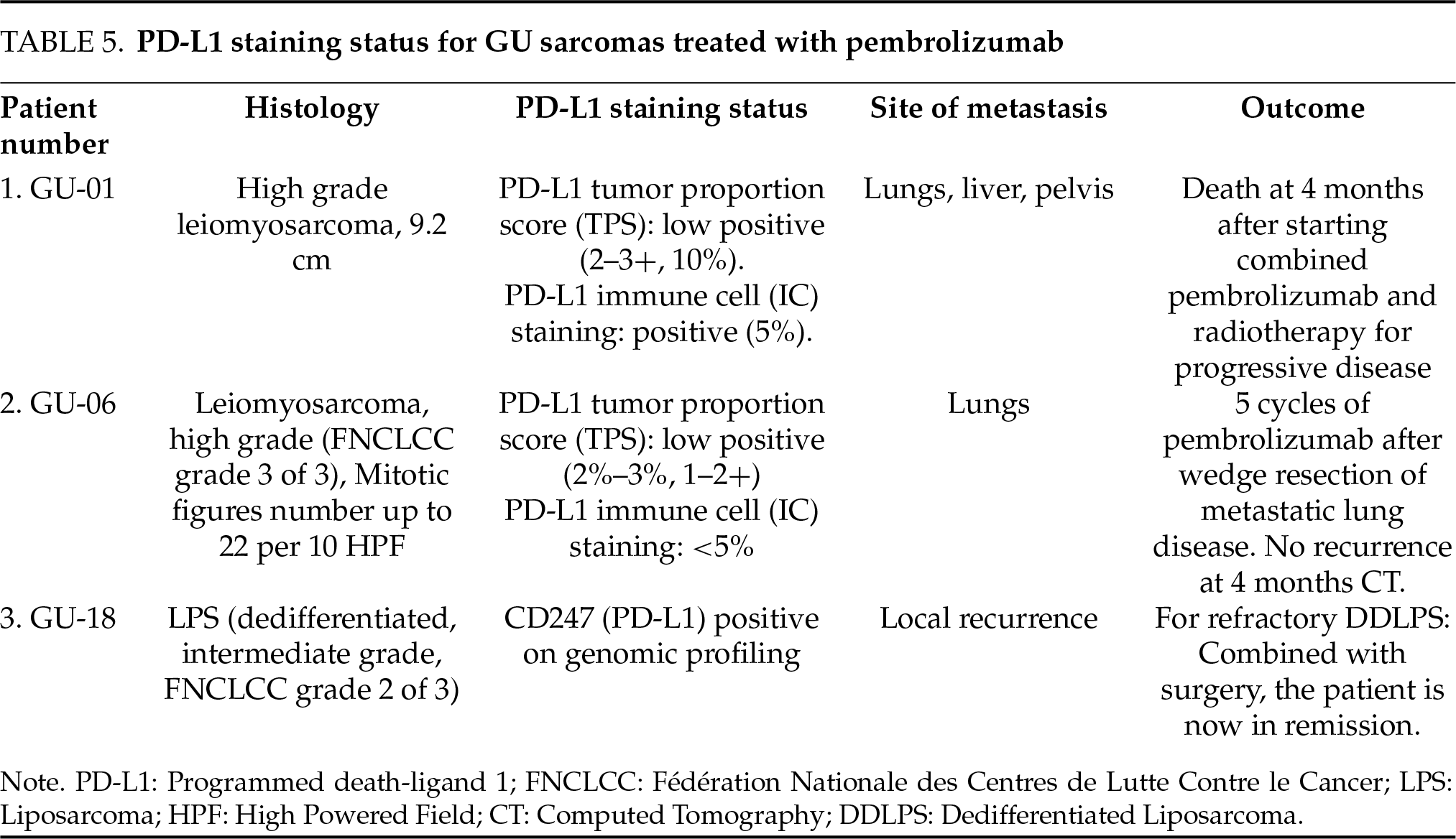

In a study conducted at MD Anderson Cancer Center by Sexton et al., comprising largely of LMS and RMS, it was concluded that multimodal therapy with pre-operative chemotherapy and radiotherapy resulted in appreciable tumor necrosis and appreciable downsizing, respectively.32 Hence, this approach may be considered for locally advanced LMS with a high chance of positive surgical margin, as positive margins are associated with a 0% 5-year survival rate.32 Two of our cases recurred within 2 years of achieving disease-free status as metastasis to the lungs (commonest site of metastasis)33 and liver, and were treated with pembrolizumab. In a retrospective analysis conducted at four Midwest Sarcoma Trials Partnership institutions, immunotherapy (pembrolizumab, nivolumab, combined pembrolizumab, nivolumab, and other combinations) resulted in a radiographic partial response in 45% of metastatic LMS cases.34 One patient developed progressive disease with hepatic metastasis and bony pelvis involvement. Tissue sampling showed extensive PD-L1 expression (Table 5), hence, pembrolizumab and adjuvant radiotherapy to the pelvis was prescribed. However, in spite of treatment with pembrolizumab, death occurred at 4 months. One of the limitations of this study is the small sample size (n = 3) of patients treated with pembrolizumab, hence it is difficult to draw conclusions from our outcomes. One patient with high-grade (FNCLCC grade 3) spindle cell variant LMS developed a solitary metastasis to the pleura after achieving disease-free status (remission), which was treated with palliative radiotherapy due to advanced age and poor performance status.

One patient with paratesticular LMS developed recurrence in the form of distal metastasis to the pleura that was treated with radiotherapy. Our patient demonstrated a mitotic count of >19/High Powered Field (HPF) with tumor necrosis (<50%). A second patient with paratesticular epithelioid LMS was found to have metastatic disease to the liver, posterior fifth rib, and lung. This patient was observed initially and subsequently treated with doxorubicin upon progression of the disease after about one year of surveillance. The patient subsequently succumbed to the sequela of brain metastasis and further progressive disease at about 40 months after diagnosis.

The kidneys are a frequent site of origin of sarcomas within the genitourinary tract, ranking just behind the paratestis.3,35 Renal sarcomas also have worse survival outcomes, possibly due to the high proportion of high-grade tumors and anatomic location, with DSS worse in the kidney compared to other GU sites.2 In the largest study to date on renal sarcomas based on the SEER database, the CSS of renal sarcomas is bleak, with a 5-year OS and CSS of 46% and 58% for nonmetastatic disease.36 These renal sarcomas have worse DSS in comparison to GU sarcomas from other sites.2 LMS are the most commonly found subgroup of sarcomas found in the kidney,36 having an OS of 28 months and a DSS time of 34 months.2 In our series, we had only one patient with renal angiosarcoma (GU-09) who had undergone cytoreductive surgical resection. There is some documented benefit to this as, cytoreductive surgery combined with chemotherapy remains a reasonable approach for metastatic disease, with surgery improving survival benefit for renal sarcomas from 10% to 40%.36 However, the outlook is only marginally improved, as in our case (angiosarcoma arising within angiomyolipoma); the disease progressed and the patient was on palliative treatment upon the last follow-up 2 years later. Primary renal angiosarcomas, in general, have a poor outlook with one-third of the cases being metastatic at presentation and 2/3rd of non-metastatic patients developing metastasis after surgical resection, with the commonest sites being lung, liver, and bones.37 Although previous studies have demonstrated a very poor prognosis (DFS: 6.0 months, PFS: 2.0 months, and OS: 5.0 months) with patients with metastatic disease having a threefold increase in the risk of death (HR = 3.27, p = 0.004), our case exhibited an exceptionally good survival rate at the most recent follow-up.37

While our study comprised an acceptable cohort, due to the relative heterogeneity and variety in the subtypes of GU sarcomas further subgroup analyses could not be performed. There is a wide variation in the survival outcome based on the initial stage, grade, and subtype of the sarcoma. Hence, the calculated OS may not be evenly applicable for all the sarcomas. As a limitation, we acknowledge that while we considered a Cox proportional hazards model, the small sample size precluded its reliable application, limiting our ability to perform a multivariate survival analysis. Our study did yield a similar 3-year RFS (66%) reported in other studies (63%) with a similar sample size5 and higher 3-year OS (81%) compared to studies with a similar sample size.3 Furthermore, each sarcoma responds differently to different treatment modalities. For instance, while surgery alone may be adequate for a well-differentiated LPS, RMS may require pretreatment chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Also, as previously noted, stage, grade, and presence of metastasis are independent predictors of mortality for GU sarcomas. Hence, OS and median survival will differ based on the cancer staging.

For the majority of the GU sarcomas, surgery remains the mainstay of treatment. Adjuvant chemo and radiotherapy have also been determined to be an important treatment modality for RMS. The prognosis of sarcomas depends on size (<5 cm vs. >5 cm), grade (well-differentiated vs. undifferentiated), margins (for local recurrence), variant of sarcomas (alveolar RMS, myxoid LPS), and presence of metastasis at presentation. Based on anatomic location, sarcomas originating in the kidneys have the worst outcomes. LMS had the highest risk of distant metastasis, RMS exhibited aggressive progression, and LPS had favorable outcomes despite frequent re-excision. Larger multicenter studies are needed to refine personalized treatment strategies and optimize long-term outcomes.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the Department of Urology and the Division of Hematology/Oncology at UI Health Care for their support and collaboration throughout this research. We especially thank Judith Pena Quevedo for her invaluable assistance in facilitating IRB approval. Their contributions were instrumental in the successful completion of this study.

Funding Statement

The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions

Abdul Baseet Arham: Conceptualization, Writing—Original Draft Preparation; John M. Rieth: Writing—Review & Editing, Supervision; Michael A. O’Donnell: Supervision, Writing—Review & Editing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials

Please reach out to the corresponding author at michael-odonnell@uiowa.edu.

Ethics Approval

University of Iowa Human Subjects Office Institutional Review Board-1 (IRB-1) under Genitourinary Retrospective Umbrella Projects (Approval number 201404766).

Informed Consent

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. As this was a retrospective review of existing records, the requirement for informed consent was waived by the Institutional Review Board (IRB). Patient confidentiality was maintained throughout the study, and all data were anonymized prior to analysis to ensure privacy and compliance with applicable data protection regulations.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Disclosure

During the preparation of this work the principal author used Quillbot paraphraser in order to improve the wording and sentence clarity. After using this tool/service, the author reviewed and edited the content as needed and takes full responsibility for the content of the publication.

References

1. Russo P, Brady MS, Conlon K et al. Adult urological sarcoma. J Urol 1992;147(4):1032–1036. doi:10.1016/s0022-5347(17)37456-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Nazemi A, Daneshmand S. Adult genitourinary sarcoma: a population-based analysis of clinical characteristics and survival. Urol Oncol 2020;38(5):334–343. doi:10.1016/j.urolonc.2019.12.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Mondaini N, Palli D, Saieva C et al. Clinical characteristics and overall survival in genitourinary sarcomas treated with curative intent: a multicenter study. Eur Urol 2005;47(4):468–473. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2004.09.013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Wang X, Tu X, Tan P et al. Adult genitourinary sarcoma: clinical characteristics and survival in a series of patients treated at a high-volume institution. Int J Urol 2017;24(6):425–431. doi:10.1111/iju.13345. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Cho SY, Moon KC, Cheong MS, Kwak C, Kim HH, Ku JH. Localized resectable genitourinary sarcoma in adult Korean patients: experiences at a single center. Yonsei Med J 2011;52(5):761–767. doi:10.3349/ymj.2011.52.5.761. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Nitta S, Kandori S, Kojo K et al. Adult genitourinary sarcoma: analysis using hospital-based cancer registry data in Japan. BMC Cancer 2024;24(1):215. doi:10.1186/s12885-024-11952-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Achard G, Charon-Barra C, Carrere S et al. Prognostic factors and outcomes of adult spermatic cord sarcoma. A study from the French Sarcoma Group. Eur J Surg Oncol 2023;49(7):1203–1208. doi:10.1016/j.ejso.2023.02.013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Ballo MT, Zagars GK, Pisters PW, Feig BW, Patel SR, von Eschenbach AC. Spermatic cord sarcoma: outcome, patterns of failure and management. J Urol 2001;166(4):1306–1310. doi:10.1097/00005392-200110000-00019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Kamitani R, Matsumoto K, Takeda T, Mizuno R, Oya M. Optimal surgical treatment for paratesticular leiomyosarcoma: retrospective analysis of 217 reported cases. BMC Cancer 2022;22(1):15. doi:10.1186/s12885-021-09122-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Martin-Broto J, Martinez-Garcia J, Moura DS et al. Phase II trial of CDK4/6 inhibitor palbociclib in advanced sarcoma based on mRNA expression of CDK4/CDKN2A. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2023;8(1):405. doi:10.1038/s41392-023-01661-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Abdul Razak AR, Bauer S, Suarez C et al. Co-Targeting of MDM2 and CDK4/6 with siremadlin and ribociclib for the treatment of patients with well-differentiated or dedifferentiated liposarcoma: results from a proof-of-concept, phase Ib study. Clin Cancer Res 2022;28(6):1087–1097. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-21-1291. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Drabbe C, Benson C, Younger E et al. Embryonal and Alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma in adults: real-life data from a tertiary sarcoma centre. Clin Oncol 2020;32(1):e27–e35. doi:10.1016/j.clon.2019.07.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Heske CM, Chi YY, Venkatramani R et al. Survival outcomes of patients with localized FOXO1 fusion-positive rhabdomyosarcoma treated on recent clinical trials: a report from the Soft Tissue Sarcoma Committee of the Children’s Oncology Group. Cancer 2021;127(6):946–956. doi:10.1002/cncr.33334. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Missiaglia E, Williamson D, Chisholm J et al. PAX3/FOXO1 fusion gene status is the key prognostic molecular marker in rhabdomyosarcoma and significantly improves current risk stratification. J Clin Oncol 2012;30(14):1670–1677. doi:10.1200/jco.2011.38.5591. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Patel SR, Hensel CP, He J et al. Epidemiology and survival outcome of adult kidney, bladder, and prostate rhabdomyosarcoma: a SEER database analysis. Rare Tumors 2020;12:2036361320977401. doi:10.1177/2036361320977401. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Kobayashi H, Okajima K, Zhang L et al. Embryonal and alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma in adolescents/young adults, adults and older adults: a population-based cohort study. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2024;54(8):903–910. doi:10.1093/jjco/hyae053. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Gerber NK, Wexler LH, Singer S et al. Adult rhabdomyosarcoma survival improved with treatment on multimodality protocols. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2013;86(1):58–63. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.12.016. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Debenham BJ, Hu KS, Harrison LB. Present status and future directions of intraoperative radiotherapy. Lancet Oncol 2013;14(11):e457–e464. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(13)70270-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Arndt C, Rodeberg D, Breitfeld PP, Raney RB, Ullrich F, Donaldson S. Does bladder preservation (as a surgical principle) lead to retaining bladder function in bladder/prostate rhabdomyosarcoma? results from intergroup rhabdomyosarcoma study IV. J Urol 2004;171(6 Pt 1):2396–2403. doi:10.1097/01.ju.0000127752.41749.a4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Rodríguez D, Preston MA, Barrisford GW, Olumi AF, Feldman AS. Clinical features of leiomyosarcoma of the urinary bladder: analysis of 183 cases. Urol Oncol: Sem Original Investigat 2014;32(7):958–965. doi:10.1016/j.urolonc.2014.01.025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Coiner BL, Cates J, Kamanda S, Giannico GA, Gordetsky JB. Leiomyosarcoma of the urinary bladder: a SEER database study and comparison to leiomyosarcomas of the uterus and extremities/trunk. Ann Diagn Pathol 2021;53:151743. doi:10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2021.151743. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Xu YF, Wang GC, Zheng JH, Peng B. Partial cystectomy: is it a reliable option for the treatment of bladder leiomyosarcoma? Can Urol Assoc J 2011;5(1):E11–E13. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

23. Pautier P, Italiano A, Piperno-Neumann S et al. Doxorubicin alone versus doxorubicin with trabectedin followed by trabectedin alone as first-line therapy for metastatic or unresectable leiomyosarcoma (LMS-04a randomised, multicentre, open-label phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2022;23(8):1044–1054. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(22)00380-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Grimer R, Judson I, Peake D, Seddon B. Guidelines for the management of soft tissue sarcomas. Sarcoma 2010;2010:506182. doi:10.1155/2010/506182. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Demetri GD, von Mehren M, Jones RL et al. Efficacy and safety of trabectedin or dacarbazine for metastatic liposarcoma or leiomyosarcoma after failure of conventional chemotherapy: results of a phase III randomized multicenter clinical trial. J Clin Oncol 2016;34(8):786–793. doi:10.1200/jco.2015.62.4734. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Saerens M, Brusselaers N, Rottey S, Decruyenaere A, Creytens D, Lapeire L. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in treatment of soft-tissue sarcoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer 2021;152:165–182. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2021.04.034. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. van der Graaf WT, Blay JY, Chawla SP et al. Pazopanib for metastatic soft-tissue sarcoma (PALETTEa randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2012;379(9829):1879–1886. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(12)60651-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Menon G, Mangla A, Yadav U. Leiomyosarcoma. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL, USA: StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Feb 28 [cited 2025 Jan 20]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK551667/. [Google Scholar]

29. Lacuna K, Bose S, Ingham M, Schwartz G. Therapeutic advances in leiomyosarcoma. Front Oncol 2023;13:1149106. doi:10.3389/fonc.2023.1149106. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Miwa S, Yamamoto N, Hayashi K, Takeuchi A, Igarashi K, Tsuchiya H. Recent advances and challenges in the treatment of rhabdomyosarcoma. Cancers 2020;12(7):1758. doi:10.3390/cancers12071758. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Graham DS, van Dams R, Jackson NJ et al. Chemotherapy and survival in patients with primary high-grade extremity and trunk soft tissue sarcoma. Cancers 2020;12(9):2389. doi:10.3390/cancers12092389. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Sexton WJ, Lance RE, Reyes AO, Pisters PW, Tu SM, Pisters LL. Adult prostate sarcoma: the M. D. Anderson Cancer Center Experience. J Urol 2001;166(2):521–525. doi:10.1097/00005392-200108000-00024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Lindberg MR, Fisher C, Thway K, Cao D, Cheville JC, Folpe AL. Leiomyosarcoma of the urinary bladder: a clinicopathological study of 34 cases. J Clin Pathol 2010;63(8):708–713. doi:10.1136/jcp.2010.077883. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Monga V, Skubitz KM, Maliske S et al. A retrospective analysis of the efficacy of immunotherapy in metastatic soft-tissue sarcomas. Cancers 2020;12(7):1873. doi:10.3390/cancers12071873. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Dotan ZA, Tal R, Golijanin D et al. Adult genitourinary sarcoma: the 25-year memorial sloan-kettering experience. J Urol 2006;176(5):2033–2039. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2006.07.021. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Moreira DM, Gershman B, Thompson RH et al. Clinicopathologic characteristics and survival for adult renal sarcoma: a population-based study. Urol Oncol 2015;33(12):505.e15–505.e20. doi:10.1016/j.urolonc.2015.07.022. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Iacovelli R, Orlando V, Palazzo A, Cortesi E. Clinical and pathological features of primary renal angiosarcoma. Can Urol Assoc J 2014;8(3–4):E223–E226. doi:10.5489/cuaj.1585. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools