Open Access

Open Access

CASE REPORT

Pseudoaneurysm after prostate biopsy: case report

Department of Urology, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, PA 15219, USA

* Corresponding Author: William Daly. Email:

Canadian Journal of Urology 2025, 32(6), 669-672. https://doi.org/10.32604/cju.2025.063778

Received 23 January 2025; Accepted 02 September 2025; Issue published 30 December 2025

Abstract

Background: Minor bleeding after prostate biopsy is a relatively common complication, but clinically significant hemorrhage happens rarely. Management of prostatic artery pseudoaneurysm has not been described in the literature. Case Description: In this case, an 84-year-old man presented after prostate biopsy with rectal bleeding and required a massive transfusion. Ultimately, he was found to have a prostatic artery pseudoaneurysm, which to our knowledge is heretofore undescribed after prostate biopsy. Bleeding ultimately stopped spontaneously as the patient deferred angioembolization. He had not recurrent bleeding on follow up but is still deciding on treatment course for newly diagnosed prostate cancer. Conclusions: Bleeding from prostatic artery pseudoaneurysm is a rare complication of prostate biopsy and can be managed with aggressive resuscitation and IR embolization if needed.Keywords

Transrectal ultrasound-guided (TRUS) prostate biopsy is an important component in the diagnosis of prostate cancer. There are several well-described complications of TRUS biopsy. These notably include sepsis, dysuria, hematuria, hematospermia, and hematochezia. While minor bleeding complications are common, significant rectal bleeding, which necessitates intervention, is rare. Pseudoaneurysm results from focal and contained arterial injury, where blood accumulates between the tunica media and tunica adventitia of the artery or in the perivascular soft tissue. They are a known complication of partial nephrectomy, percutaaneous nephrolithotomy and even ureteroscopy, but are not commonly associated with the management of prostate cancer.1,2

Here we present a case of transfusion-dependent rectal bleeding secondary to prostatic artery pseudoaneurysm after TRUS biopsy. To our knowledge, this is the first report of post-TRUS biopsy pseudoaneurysm. HIPAA release was obtained from the patient.

An 84-year-old man with a history of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation on aspirin and apixaban presented to the UPMC East emergency department in July of 2022 with gross hematuria and new-onset urinary retention. Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) had been elevated to 27 ng/mL in 2016, six years prior to admission, but the patient had declined evaluation at that time. Digital rectal exam revealed a firm prostate bilaterally, and PSA was found to be 73.3 ng/mL. Outpatient TRUS biopsy was planned as there was concern for symptomatic prostate cancer.

Aspirin and apixaban were held five days prior to the procedure, and he underwent an uncomplicated 12-core systematic biopsy. As instructed, he restarted his anticoagulation 3 days following the procedure. That evening, he noted a small amount of blood mixed in with his stool. Early the next morning, he had an episode of large volume, bright red hematochezia, and presented to a local emergency department for further evaluation.

Initially, the patient was hemodynamically stable with a low normal hemoglobin of 12.0 g/dL. However, in the trauma bay, he had several more episodes of large-volume hematochezia and became pale, tachycardic, hypotensive, and minimally responsive. He was emergently transfused 4 units of packed red blood cells, platelets, and fresh frozen plasma. His condition improved, and there were no further episodes of hematochezia.

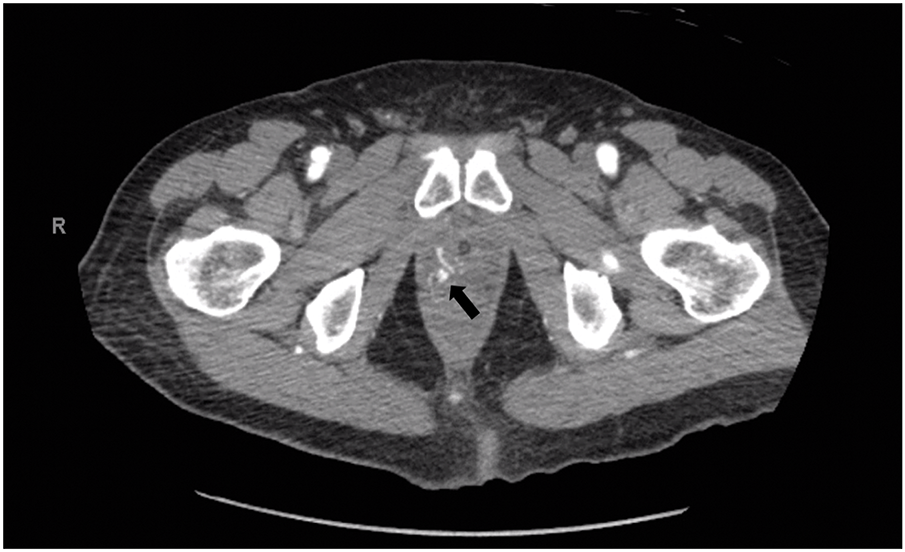

Computed tomography (CT) angiogram of the abdomen and pelvis showed a 4.2 × 7.4 mm pseudoaneurysm of the prostatic artery (Figure 1). He was transferred to UPMC Presbyterian for consideration of pseudoaneurysm embolization. He, however, ultimately declined, citing a “bad feeling” about going forward with the procedure. He had no further bleeding episodes and was discharged home in stable condition. His biopsy results demonstrated that all cores were positive for prostate adenocarcinoma, maximum grade Gleason 4 + 3 = 7, and >50% core involvement. Extraprostatic extension and perineural invasion were noted. He was referred to the medical oncology team at UPMC Shadyside to discuss treatment options.

FIGURE 1. Computed tomography (CT) angiogram demonstrating right prostatic artery pseudoaneurysm. The arrow indicates the site of the pseudoaneurysm

Bleeding complications are well described after TRUS biopsy, although the incidence varies substantially across studies. In the case of rectal bleeding specifically, large cohort studies have reported rates between 1.3 and 45%.3 In a study of 1147 patients who underwent TRUS biopsy, Rosario et al. found 36.8% of men had some degree of hematochezia, with 2.5% rating it as a moderate or major problem.4 Berger et al. evaluated 4303 men and reported an overall rate of 2.3% with a 0.6% incidence of bleeding requiring intervention.5 The European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) found that only 1.3% of men experience rectal bleeding.6

Although pseudoaneurysm after TRUS biopsy has not previously been described, one case study did report on an arteriovenous fistula (AVF) from the right prostatic artery that developed three days after biopsy. Endoscopic clipping failed, and the patient underwent embolization of the fistula.7 Pseudoaneurysm in the hypogastric distribution has been more frequently described after pelvic surgery. There are, for instance, reports of pseudoaneurysms after robotic-assisted radical prostatectomy, which required angioembolization.8 Finally, pseudoaneurysm of the pelvic vasculature has been reported after pelvic trauma. In this case, a man developed a pseudoaneurysm of the internal pudendal artery as well as AVF after a blunt pelvic injury sustained during a motor vehicle accident.9

In the case presented here, the patient ultimately deferred intervention. As with the cases above, a series of treatment options ranging from tamponade of the bleeding to embolization may have been available. At the time of considering further procedures or stabilizing measures, endoscopic clipping, though theoretically available, would likely have been limited by difficulty identifying and accessing the pseudoaneurysm. Ultimately, embolization with IR was the only reasonable option available, which, as with elective prostate artery embolization and the cases described, likely would have been completed with microparticle embolization.10 In terms of prevention, we may have considered an alternative approach. Several studies have shown a relationship between the number of biopsies taken and the risk of bleeding, and so taking fewer samples may have been appropriate here.11 Transperineal biopsy is becoming more popular and provides benefit in terms of infectious outcomes, although based on the available data, there does not appear to be a significant advantage in terms of bleeding risk.12

Data on cessation of anticoagulation prior to prostate biopsy and timing of re-initiation are varied and depend on the agent in question.3 Several studies have demonstrated that warfarin may be safe to continue through prostate biopsy, while others have shown that even continuing low-dose aspirin may increase the risk of, or prolong, minor bleeding.11,13 Limited data exist regarding the safety of direct oral anticoagulants and other antiplatelet agents. The EAU and AUA make no formal recommendations regarding anticoagulation cessation, although in a 2016 white paper, the AUA does reference the common practice of holding these medications 5–7 days prior to biopsy.14,15 Ultimately, providers and patients must weigh the risks of bleeding against those of stopping anticoagulation. Certainly, in this case, the timing of restarting anticoagulation would suggest it was likely a significant contributing factor to the patient’s bleeding, and a longer anticoagulation holiday could have been considered.

We present here a case of prostatic artery pseudoaneurysm following TRUS prostate biopsy. Significant bleeding after biopsy is a rare event, and bleeding secondary to vascular malformation is even more so. To our knowledge, this case report represents the first description of prostatic artery pseudoaneurysm after prostate biopsy. Modern paradigms for management of post-biopsy bleeding are now more likely to include the possibility of embolization, which may lead to further identification of pseudoaneurysm or other vascular abnormality.

Acknowledgement

Not applicable.

Funding Statement

The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions

The authors confirm contribution to the case report as follows: Conceptualization, William Daly, Daniel Pelzman, P. Dafe Ogagan, Stephen V. Jackman; chart review, William Daly; manuscript drafting, William Daly; manuscript editing and re-writing, William Daly, Daniel Pelzman, P. Dafe Ogagan, Stephen V. Jackman. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Author, [William Daly], upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval

This case report was determined to not meet the definition of human subjects research and thus not require IRB approval by the human research protection office at the University of Pittsburgh. Written HIPAA authorization was obtained from the patient for publication of their medical information.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest regarding the present study.

References

1. Yin C, Chen F, Jiang J, Xu J, Shi B. Renal pseudoaneurysm after holmium laser lithotripsy with flexible ureteroscopy: an unusual case report and literature review. J Int Med Res 2023;51(3):03000605231162784. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

2. Hoshina H, Sugihara T, Fujisaki A et al. Effectiveness of soft coagulation in robot-assisted partial nephrectomy in preventing pseudoaneurysms and its influence on renal function based on propensity score-matched analysis. Transl Androl Urol 2024;13(7):1085–1092. doi:10.21037/tau-24-84. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Borghesi M, Ahmed H, Nam R et al. Complications after systematic, random, and image-guided prostate biopsy. Eur Urol 2017;71(3):353–365. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2016.08.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Rosario DJ, Lane JA, Metcalfe C et al. Short term outcomes of prostate biopsy in men tested for cancer by prostate specific antigen: prospective evaluation within ProtecT study. BMJ 2012;344:d7894. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

5. Berger AP, Gozzi C, Steiner H et al. Complication rate of transrectal ultrasound guided prostate biopsy: a comparison among 3 protocols with 6, 10 and 15 cores. J Urol 2004;171(4):1478–1481; discussion 1480–1481. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

6. Raaijmakers R, Kirkels WJ, Roobol MJ, Wildhagen MF, Schrder FH. Complication rates and risk factors of 5802 transrectal ultrasound-guided sextant biopsies of the prostate within a population-based screening program. Urology 2002;60(5):826–830. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

7. De Beule T, Carels K, Tejpar S, Van Cleynenbreugel B, Oyen R, Maleux G. Prostatic biopsy-related rectal bleeding refractory to medical and endoscopic therapy definitively managed by catheter-directed embolotherapy: a case report. J Med Case Rep 2015;9(1):242. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

8. Gonzalez-Araiza G, Haddad L, Patel S, Karageorgiou J. Percutaneous embolization of a postsurgical prostatic artery pseudoaneurysm and arteriovenous fistula. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2019;30(2):269–271. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

9. Galosi AB, Capretti C, Leone L, Tiroli M, Cantoro D, Polito M. Pseudoaneurysm with arteriovenous fistula of the prostate after pelvic trauma: ultrasound imaging. Arch Ital Urol Androl 2016;88(4):317–319. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

10. Carnevale FC, de Assis AM, Moreira AM. Prostatic artery embolization: equipment, procedure steps, and overcoming technical challenges. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol 2020;23(3):100691. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

11. Loeb S, Vellekoop A, Ahmed HU et al. Systematic review of complications of prostate biopsy. Eur Urol 2013;64(6):876–892. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

12. Hu JC, Assel M, Allaf ME et al. Transperineal vs. transrectal prostate biopsy—the PREVENT randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol 2024;10(11):1590. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

13. Chen D, Liu G, Xie Y, Chen C, Luo Z, Liu Y. Safety of transrectal ultrasound-guided prostate biopsy in patients receiving aspirin. Medicine 2021;100(34):e26985. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

14. Chowdhury R, Abbas A, Idriz S, Hoy A, Rutherford EE, Smart JM. Should warfarin or aspirin be stopped prior to prostate biopsy? An analysis of bleeding complications related to increasing sample number regimes. Clin Radiol 2012;67(12):e64–70. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

15. Liss M, Ehdale B, Loeb S et al. AUA white paper on the prevention and treatment of the more common complications related to prostate biopsy updated. J Urol. 2017 Aug;198(2):329–334. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2017.01.103. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools