Open Access

Open Access

HOW I DO IT

Stenting severely obstructed ureters: a useful method for a common challenge

Department of Urology, Hillel Yaffe Medical Center, Hadera, 3810000, Israel

* Corresponding Author: Yoav Avidor. Email:

# The authors contributed equally to the manuscript

Canadian Journal of Urology 2025, 32(6), 651-657. https://doi.org/10.32604/cju.2025.064383

Received 13 February 2025; Accepted 06 August 2025; Issue published 30 December 2025

Abstract

In this paper we describe a surgical technique for achieving safe ureteral stent placement in cases of severe obstruction. Although retrograde endoscopic stenting is often the preferred method for ureteral drainage, the existing literature offers limited insight into innovative surgical methods made possible by recent technological advancements. In this report, we present a method that employs a ureteral dilator as an anchor to facilitate precise and effective stent insertion. The technique involves positioning a ureteral dilator in close contact with the tip of the obstructing stone. In this position, the dilator not only functions to dilate the ureter but also serves as a stable anchor point, facilitating the passage of the ureteral stent. We successfully employed this method in 23 patients in whom initial attempts at safe stent placement were unsuccessful due to severe obstruction. In all cases, ureteral drainage was achieved, thus avoiding percutaneous nephrostomy.Our findings suggest that the tensile strength of the ureteral dilator provides reliable anchorage, supporting the advancement of the stent. This technique may offer a safe and effective alternative for ureteral stenting in cases of severe obstruction, potentially reducing the need for percutaneous nephrostomy.

Keywords

Drainage of an obstructed ureter by endoscopic ureteral catheterization is a common urologic procedure. Indications for acute, or early intervention with ureteral drainage are renal failure, fever with signs of urinary tract infection, obstruction of a single kidney, and intractable pain.1

Despite its clinical benefits and widespread use, ureteral stenting is still subject to failure and its insertion is associated with complications. Globally, an estimated 1.5 million stents are inserted each year, with failure rates reported as high as 80% in certain cases. In response, in recent years there has been a large body of research focusing on development of innovative stent technology predominately through the development of materials and architectural features that may prevent stent associated complications.2

Endourologists have developed useful and ingenious tricks to achieve safe ureteral drainage in cases that were not possible with prior generations of equipment, yet literature on the topic remains limited. It is important to share best practices and ensure that these types of informal methods are captured in the literature and passed along to new entrants to the field. In this report, we describe a method to achieve safe ureteral catheterization in cases of severe obstruction that are not amenable to the routine approach described in the literature.

In order to enlighten on the method used in our paper we illustrate it with the use of figures explaining each step throughout the technique process.

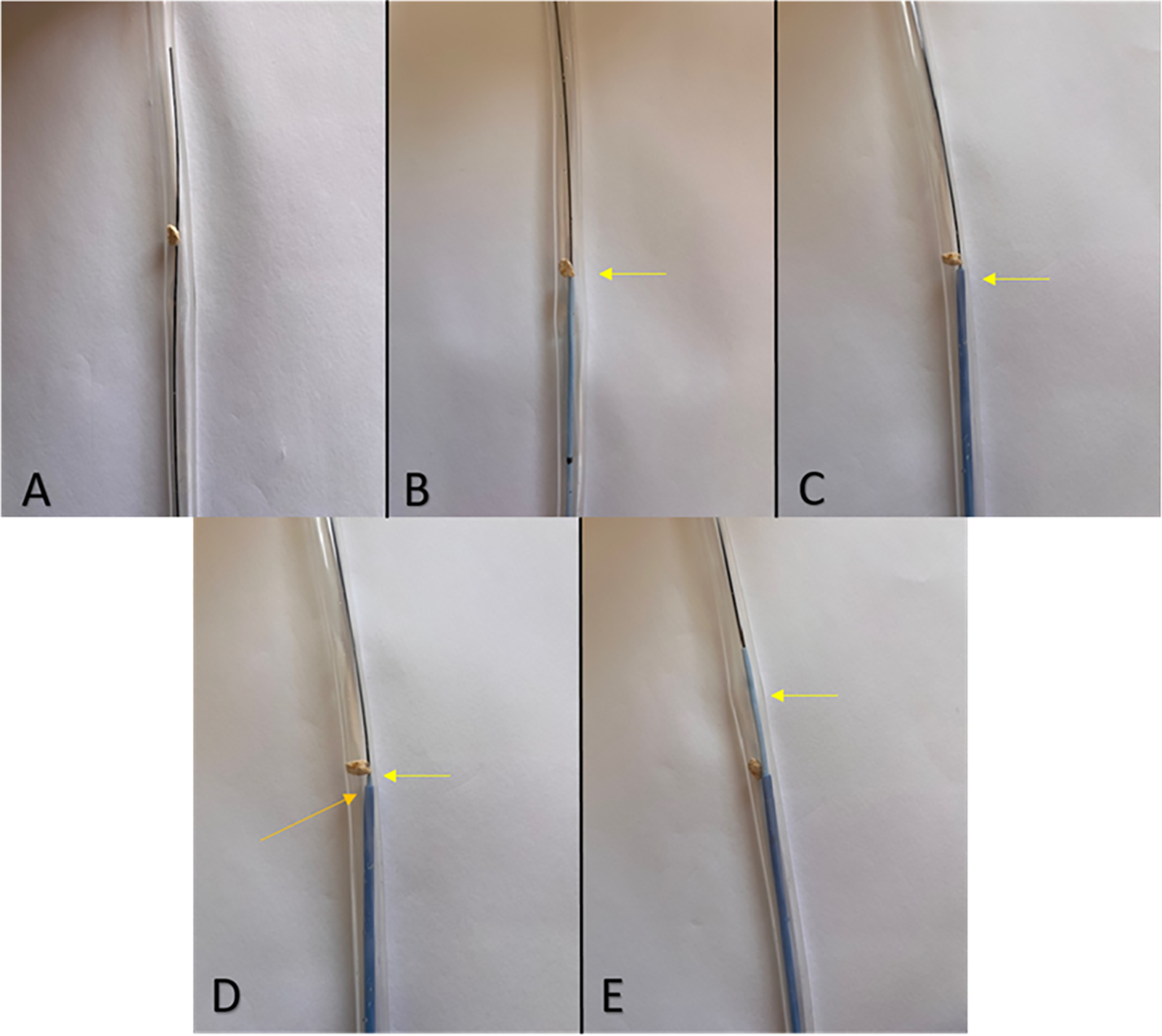

Figure 1 presents a rendering of the technique. At the outset, a rigid cystoscope or semi-rigid ureteroscope is used to insert a 0.035-inch hydrophilic guidewire (Terumo Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) into the ureter, which is advanced up to the renal pelvis under fluoroscopy as shown in Figure 1A. Routinely, the next action is to pass a ureteral stent following the guidewire beyond the obstruction. However, in a scenario where a stent cannot be safely advanced up the guidewire and beyond the stone, we remain with a guidewire in place, but no stent, as shown in Figure 1B.

FIGURE 1. 2 step-by-step illustration of the ureteral stent insertion procedure. (A) A guidewire is passed beyond a ureteral stone and up the ureter. (B) A double-J stent (see yellow arrow) cannot be passed up the guidewire beyond the obstructing stone. (C) A ureteral dilator sheath (see yellow arrow) is positioned in close proximity to the tip of the stone. (D) A double-J stent (see yellow arrow) is passed through the ureteral dilator (orange arrow). Note how the dilator is positioned very close to the stone in order to provide a hard anchorage point and facilitate upward motion of the stent. (E) The stent (see yellow arrow) is now successfully pushed up the ureter and beyond the obstructing stone

In such cases, we would normally coordinate emergent percutaneous nephrostomy at the Radiology suite. However, in our technique, we remove the stent and pass an 8F/10F ureteral dilator (2.7 mm/3.4 mm) (Boston Scientific Corporation, Marlborough, MA, USA) on the guidewire under fluoroscopy guidance up to the distal part of the stone, as can be seen in Figure 1C. The internal element of the dilator, often called “introducer”, is then extracted, and a double-J stent (Cook Incorporated, Bloomington, IN, USA) is passed through the ureteral dilator sheath lumen and pushed upward in a normal fashion as seen in Figure 1D,E. When pushing up the stent, it is important not to use extra force, we should only rely on the improved anchorage point to facilitate stent passage. Importantly, the semi-rigid dilator sheath is positioned under fluoroscopy guidance just under the obstruction, in more intimate contact with the stone as compared to that afforded by placing the cystoscope very close to the ureteral orifice. In this position, the dilator serves an additional purpose as it provides a fixed anchorage and angulation point that supports the double-J stent tip as it exits the sheath orifice and navigates the obstructed segment of the ureter.

Of note, this method is only possible to perform in cases where the stone lies below the iliac vessels, particularly in men. For upper ureteral stones, the 10 Fr segment is not long enough to reach the obstruction. In such cases, we position the dilator in the general area of the ureteral intersection with the Iliac vessels.

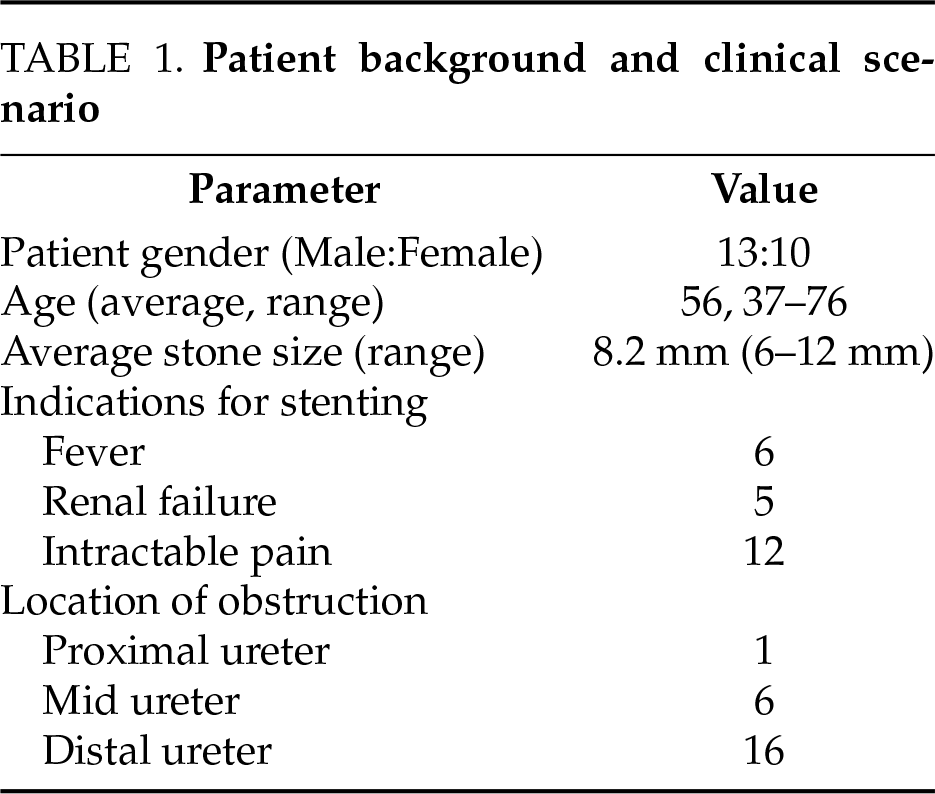

In this report, we present our findings from the treatment of 23 patients with indications for ureteral obstruction relief secondary to urolithiasis. Demographic data, indications for ureteral drainage, as well as the size and location of the stones, are summarized in Table 1. In all cases, ureteral stenting and drainage were successfully and safely performed using a ureteral dilator, as described above. Notably, in all 23 cases included in this report, prior attempts to advance a guidewire beyond the obstruction or to place a double-J stent over the guidewire using conventional techniques were either unsuccessful or considered too risky. The use of our described method resulted in successful ureteral stent placement in every case.

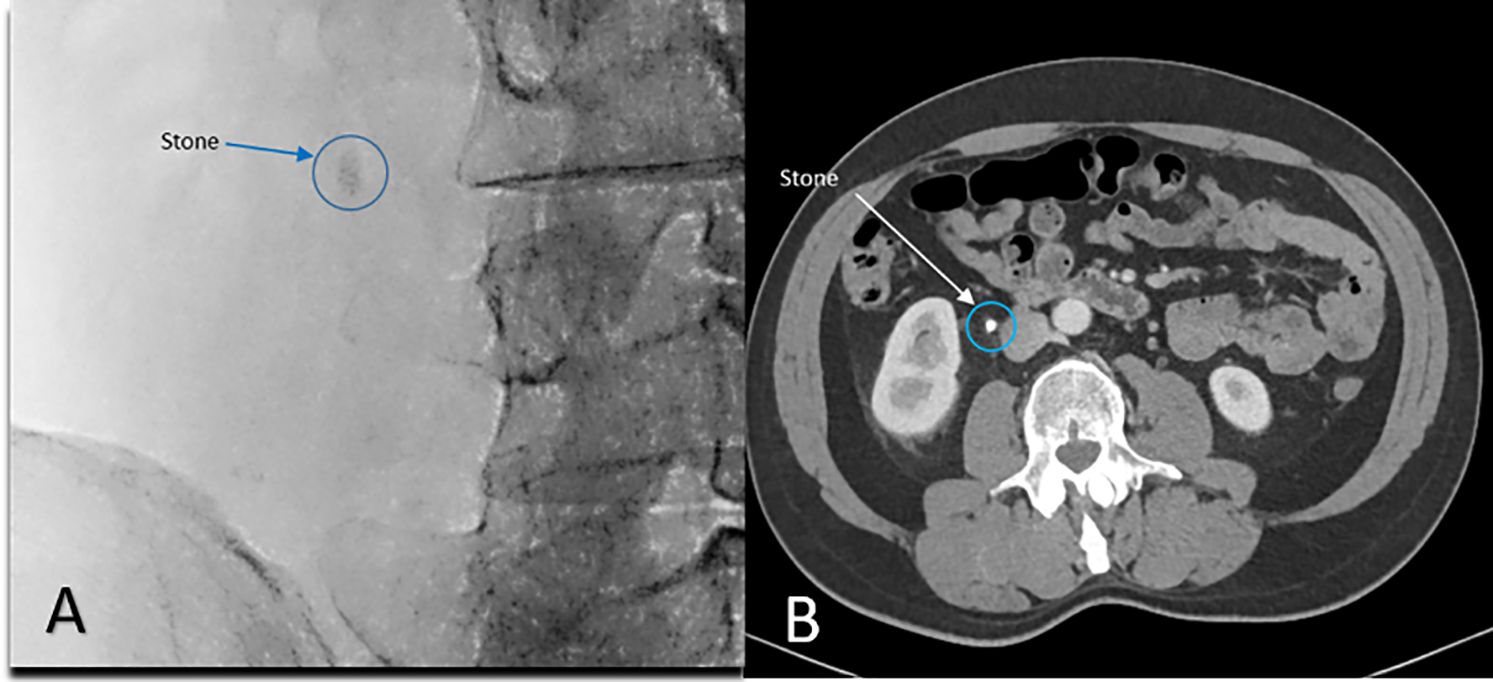

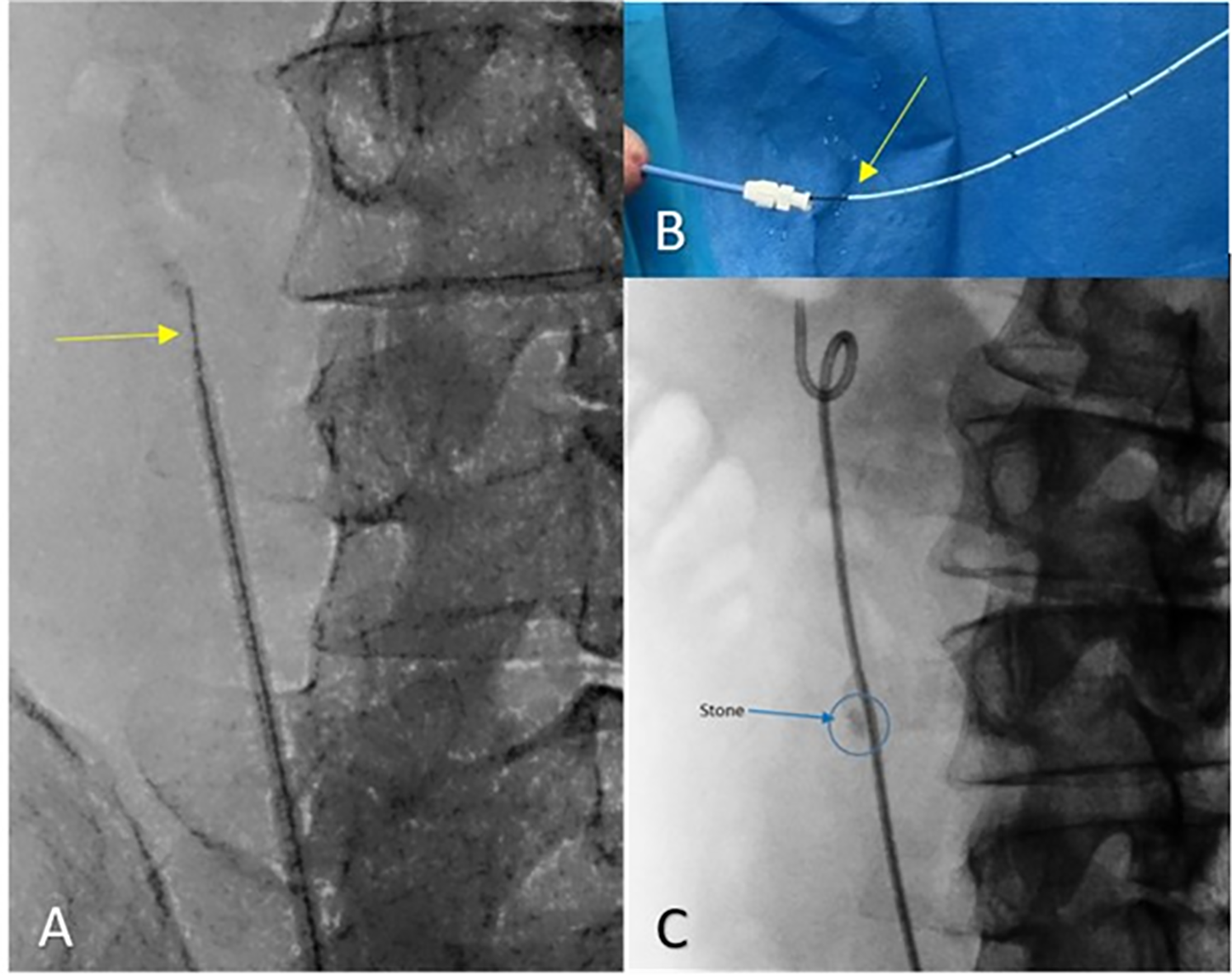

We have included a sample demonstrative case of a 7 mm right ureteral stone, as can be seen in Figure 2. The stone was not amenable to the standard retrograde stenting approach, since after passing a guidewire alongside the stone, the degree of ureteral occlusion prevented the safe passage of a double-J stent. A ureteral dilator was positioned close to the stone tip as described above and shown in Figure 3A,B, followed by passage of a double-J stent through the ureteral dilator sheath as seen in Figure 3C.

FIGURE 2. Mid-distal ureteral stone measuring 7 mm. (A) Intraoperative fluoroscopy; (B) Pre-operative CT scanning

FIGURE 3. Sequential stages of double-j stent placement over a guidewire using an 8/10 Dilator (A) The ureteral 8/10 dilator is advanced on the guidewire (yellow arrow) and positioned close to the stone. (B) Double-J stent (yellow arrow) advanced through the dilator sheath. (C) Double-J stent in place

Brief discussion of the results

Endoscopic retrograde catheterization remains the preferred method of choice for ureteral drainage among most surgeons, primarily because of its minimally invasive profile. In the classic approach, under cystoscopy, the ureteral orifice in the obstructed side is visualized, and under fluoroscopy guidance, a guidewire is advanced to the renal pelvis, followed by double-J stent insertion.

Since the introduction of ureteral stents several decades ago, the field has undergone significant innovation, with ongoing advancements in both design and materials aimed at enhancing their clinical performance.

These factors include the ease and safety of stent deployment, resistance to compression, prevention of occlusion and fracture, and minimizing the risks of encrustation and biofilm formation all while ensuring a cost-effective solution per unit.2–4

Highly useful ancillary tools such as the ureteral coaxial dilator, ureteral access sheath, smaller diameter double-J stents such as the 4.8F Percuflex Plus (Boston Scientific Corporation, Marlborough, MA, USA) and extra stiff guidewires such as the Amplatz Extra Stiff guidewire (Cook Incorporated, Bloomington, IN, USA) facilitate stent placement and enabling smooth and safe stenting.5–6 Innovations in this field have significantly expanded the role of retrograde ureteral stenting over time, as reflected in current specialty guidelines.1,7–8 Nonetheless, some stone-related obstructions prove resistant to treatment, often arising in clinical scenarios that mandate urgent kidney drainage. In cases where retrograde ureteral stenting is unsuccessful, or when continued efforts to navigate the obstructed ureter are perceived to elevate the risk for ureteral injury, emergent endoscopic lithotripsy followed by ureteral stenting may provide an appropriate solution, yet this approach may not be desired, for example, due to potential complications resulting from an infected stone, or certainly if purulent urine is encountered during the endoscopic intervention.1 In such cases, failure to retrogradely stent the ureter requires emergent percutaneous nephrostomy, exposing the patient to an additional procedure, morbidity, and cost.9–10

At this point, a common predicament known to many surgeons is whether another endoscopic maneuver is possible and justified in order to achieve effective ureteral drainage and mitigate the need for percutaneous nephrostomy as a second procedure.

Urologic surgeons regularly employ the growing armamentarium of tools in creative ways to achieve ureteral drainage, yet the literature on these methods is quite limited. For example, we previously reported on a delayed catheterization technique.11 In this technique, when a double-J stent cannot be passed beyond the site of the stone, a guidewire is left in place for 24–48 h connected to the tip of a Foley catheter. A second attempt to pass a double-J stent is successful in most patients, likely thanks to gradual stretching of the ureter by the indwelling guidewire as well as relief of intraluminal edema. However, while useful in some cases, this technique cannot provide immediate drainage when warranted, for example, when the patient is septic. In this report, we describe a method in which a ureteral dilator is advanced retrogradely up to the obstruction and used as an anchor and scaffold for double-J insertion.

The mechanics of ureteral stenting vary considerably from case to case and are governed by patient-related and stent-related factors. Patient-related factors include location in the ureter, patient age, and the degree of stone friability and impaction. Stent-related parameters are also key, including the stent’s material and coating, which impact the coefficient of friction and influence how easily a stent is inserted.12–13 A third key factor is the distance between the tip of the endoscope to the stone. Our ability to control and propel the catheter up the ureter is greater when there is a close, fixed point of anchorage.

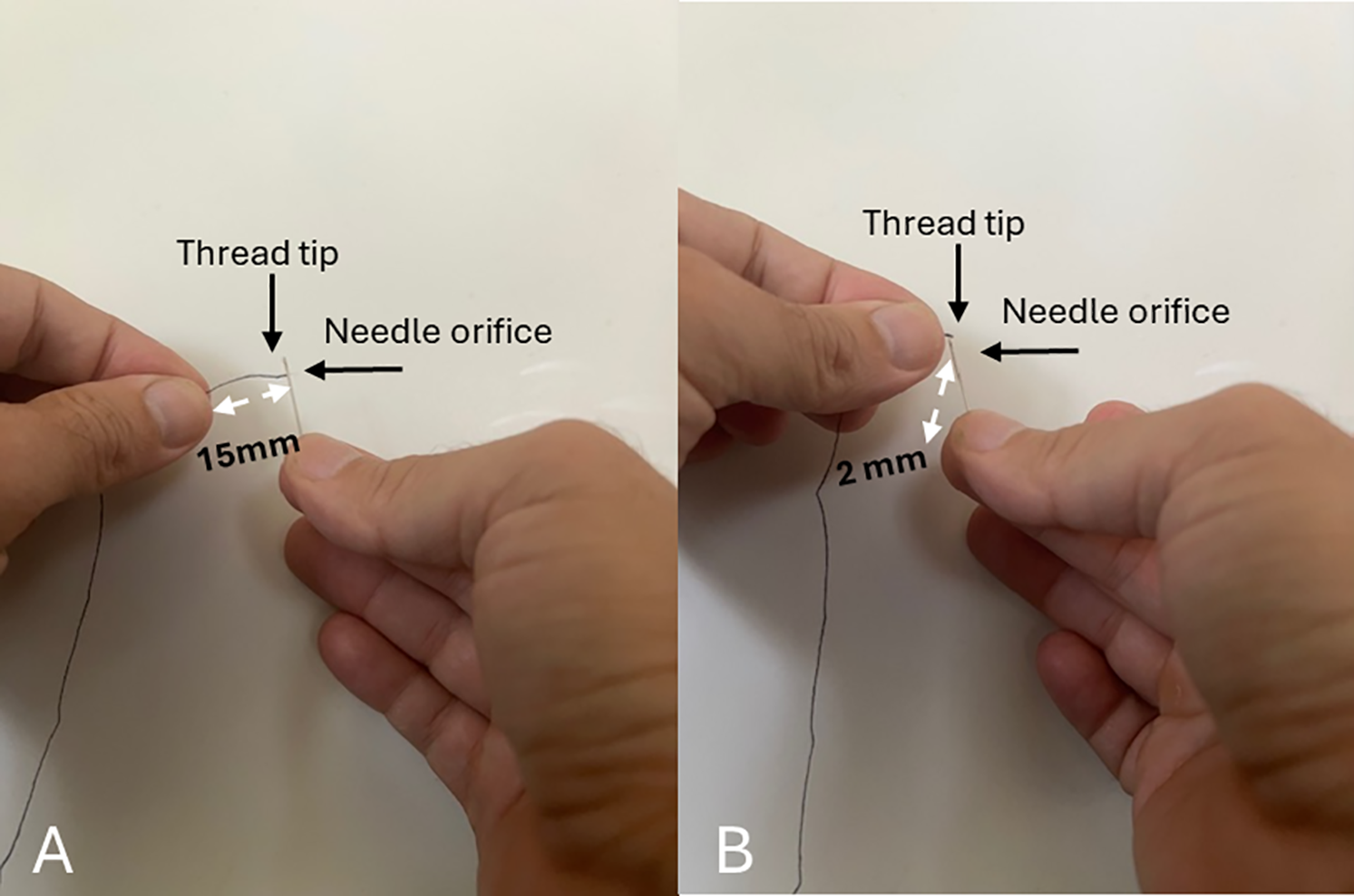

To illustrate, imagine threading a needle while holding the thread far away from its distal end, in a more proximal position, as seen in Figure 4A. As you try to navigate the thread through the needle orifice, it tends to buckle and shoot off to the side, missing the orifice. Your chances of successfully threading the needle improve significantly by advancing your fingertips to the distal end of the thread, thus aligning it directly with the needle orifice as shown in Figure 4B. The closer the fixed point of anchoring to the distal tip, the more likely we are to maintain alignment of the thread with the desired direction of the needle orifice.

FIGURE 4. Example illustration: Aligning thread with needle. (A) Holding the thread far from the tip. In this approach, it is challenging to thread the needle orifice. (B) Holding the thread closer to the tip provided a fixed point of anchorage and better alignment with the direction of the needle orifice

Double-J catheters are designed to be highly flexible to prevent trauma to the urothelium, which makes them less effective in bypassing significant obstructions where the degree of material tensile strength matters. In cases of severe obstruction, the tip of the double-J stent undergoes a similar fate to the thread in the above example. Naturally, as in the needle and thread example, the closer the tip of the double-J stent to the nearest point of anchoring, the higher the likelihood of successfully navigating past the obstruction. Ureteral dilator sheaths can be safely advanced up the ureter and provide a fixed anchor point by touching the stone or reaching very close to it. By positioning the ureteral dilator sheath next to the stone, we minimize the distance between the obstruction and the point of anchoring of the double-J stent, modify the anchoring force to our advantage, and are thus able in many cases to safely advance the stent beyond the stone. A limitation of this method is that it is less applicable in cases involving upper ureteral stones, due to the length of the 10 Fr segment. For safety reasons, the 8/10 dilator is advanced only up to the point where the ureter crosses the iliac vessels. As such, the anchor point effect is weaker for upper ureteral stones, which can be located several centimeters away from the sheath in an area where the ureter tends to be more mobile, to make matters a little more challenging. In these cases, the surgeon may consider exchanging the first wire for a stiff guidewire.

A different challenge to stent insertion for obstructing ureteral stones is difficulty advancing a guidewire beyond the stone. The 8/10 dilator should confer similar benefits to guide-wire navigation and in our experience, this technique may also be useful in these cases. Yet, the present study did not focus on this patient population.

Although our technique doesn’t guarantee success in achieving ureteral drainage in 100% of cases, and some patients with severe obstruction or impacted stones may still require percutaneous nephrostomy, it remains a simple, straightforward approach that is easy to learn and perform particularly in the presence of bleeding or edema at the site of obstruction.

At the relatively low additional cost of a ureteral dilator, and with a short time requirement, the technique usually expedites immediate drainage and mitigates the cost and possible complications associated with percutaneous nephrostomy. Residents training in endourology in our department have been eager to adopt and quick to master this technique as a means to overcome challenging situations.

Our findings indicate that utilizing a ureteral dilator, as outlined in the technique above, enabled safe stent placement in cases of severe ureteral obstruction. This method may offer a practical alternative to percutaneous drainage as in most cases the remaining options involve either transitioning to percutaneous access or to attempt ureteral stenting in the face of significant occlusion and risk of ureteral injury.

Familiarity with this technique enhances the urologist’s confidence in performing retrograde ureteral stenting and drainage. Moreover, we believe that documenting such practical endourological techniques in the literature can help establish best practices and empower training.

Acknowledgement

Not applicable.

Funding Statement

The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Yoav Avidor and Ghalib Lidawi; methodology, Yoav Avidor, Ghalib Lidawi and Ronen Rub; software, Yoav Avidor; validation, Yoav Avidor, Ghalib Lidawi and Ronen Rub; formal analysis, Yoav Avidor, Ghalib Lidawi, Muhammad Majdoub, Mohsin Asali and Ronen Rub; investigation, Yoav Avidor, Ghalib Lidawi, Muhammad Majdoub, Mohsin Asali and Ronen Rub; resources, Yoav Avidor, Ghalib Lidawi and Ronen Rub; data curation, Yoav Avidor, Ghalib Lidawi and Ronen Rub; writing—original draft preparation, Yoav Avidor and Ghalib Lidawi; writing—review and editing, Yoav Avidor, Ghalib Lidawi, Muhammad Majdoub, Mohsin Asali and Ronen Rub; visualization, Yoav Avidor and Ghalib Lidawi; supervision, Yoav Avidor, Ghalib Lidawi and Ronen Rub; project administration, Yoav Avidor; funding acquisition, not applicable. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethical Approval

The study protocol was approved by the Hillel Yaffe Medical Center Ethics Committee, which also waived the requirement for informed consent due to the retrospective nature of the study and anonymized data analysis. Ethical approval reference code 4-0127-H.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Assimos D, Krambeck A, Miller NL et al. Surgical management of stones: American urological association/endourological society guideline, PART I. J Urol 2016;196(4):1153–1160. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2016.05.090. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. De Grazia A, Somani BK, Soria F, Carugo D, Mosayyebi A. Latest advancements in ureteral stent technology. Transl Androl Urol 2019;8(Suppl 4):S436–S441. doi:10.21037/tau.2019.08.16. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Sali GM, Joshi HB. Ureteric stents: overview of current clinical applications and economic implications. Int J Urol 2020;27(1):7–15. doi:10.1111/iju.14119. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Mosayyebi A, Manes C, Carugo D, Somani BK. Advances in ureteral stent design and materials. Curr Urol Rep 2018;19(5):35. doi:10.1007/s11934-018-0779-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Eiley DM, McDougall EM, Smith AD. Techniques for stenting the normal and obstructed ureter. J Endourol 1997;11(6):419–429. doi:10.1089/end.1997.11.419. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Wu NZ, Auge BK, Preminger GM. Simplified ureteral stent placement with the assistance of a ureteral access sheath. J Urol 2001;166:206–208. doi:10.1097/00005392-200107000-00051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Turk C, Petrik A, Sarica K et al. EAU guidelines on interventional treatment for urolithiasis. Eur Urol 2016;69(3):475–482. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2015.07.041. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Akram M, Jahrreiss V, Skolarikos A et al. Urological guidelines for kidney stones: overview and comprehensive update. J Clin Med 2024;13(4):1114. doi:10.3390/jcm13041114. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Skolarikos A, Alivizatos G, Papatsoris A, Constantinides K, Zerbas A, Deliveliotis C. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous nephrostomy performed by urologists: 10-year experience. Urology 2006;68(3):495–499. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2006.03.072. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Weltings A, Schout BMA, Roshani H, Kamphuis GM, Pelger RCM. Lessons from literature: nephrostomy versus Double J ureteral catheterization in patients with obstructive urolithiasis—which method is superior? J Endourol 2019;33(10):777–786. doi:10.1089/end.2019.0309. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Avidor Y, Ben-Chaim J, Greenstein A, Rub R. Glide wires for delayed catheterization of severely obstructed ureters. Eur Urol 2000;37(1):56–57. doi:10.1159/000020100. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Bernasconi V, Tozzi M, Pietropaolo A et al. Comprehensive overview of ureteral stents based on clinical aspects, material and design. Cent European J Urol 2023;76(1):49–56. doi:10.5173/ceju.2023.218. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. O’Meara S, Cunnane EM, Croghan SM et al. Mechanical characteristics of the ureter and clinical implications. Nat Rev Urol 2024;21(4):197–213. doi:10.1038/s41585-023-00831-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools