Open Access

Open Access

MINI REVIEW

Patient reported outcome measures: their evolution and expansion in urology

Department of Urology, University of California San Francisco, 400 Parnassus Ave, San Francisco, CA 94143, USA

* Corresponding Author: Ankith P. Maremanda. Email:

Canadian Journal of Urology 2025, 32(6), 545-550. https://doi.org/10.32604/cju.2025.064433

Received 16 February 2025; Accepted 25 June 2025; Issue published 30 December 2025

Abstract

We describe the history of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) in medicine, with a focus on the development and use of the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) in urologic practice. PROMs emerged in the 1970s with tools like the Sickness Impact Profile, designed to capture patients’ perspectives on how disease affects daily life. In the 1990s, PROMs entered urology with the creation of the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) and the IIEF, developed in 1992 and 1997, respectively. As organizations such as the National Institutes of Health began prioritizing PROMs for evaluating sexual function, the IIEF gained recognition as a valid and reliable measure of erectile dysfunction severity. The introduction of the abbreviated IIEF-5 further expanded its use in both research and clinical practice. For this review, we searched PubMed for literature on the history, development, and application of PROMs and the IIEF, and conducted an oral interview with Dr. Raymond C. Rosen, the IIEF’s primary author. In conclusion, PROMs have long served as essential tools for capturing patients’ experiences, and the IIEF has significantly advanced sexual medicine by offering a highly valid and reliable instrument for assessing erectile dysfunction.Keywords

Patient-reported outcome Measures (PROMs) are commonly used to collect information directly from patients about their quality of life. They are generally administered as a questionnaire, either in physical or virtual formats, making them a valuable and convenient tool. Their objective nature is designed to capture patients’ perspectives on the diseases and conditions they face without the influence of a medical professional. PROMs can be disease-specific or generalized to all patients. Their development is rooted in the field of psychometrics, which is concerned with designing and improving measurement tools to accurately assess latent variables.1 PROMs typically undergo thorough psychometric testing to confirm their validity and reliability before seeing use in research and clinical environments. These evaluations assess various measurement properties, such as content validity, construct validity, criterion validity, internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and responsiveness.2 By rigorously testing these properties, researchers ensure that PROMs accurately measure patient-reported outcomes and can detect changes over time. Furthermore, PROMs can also differentiate between patients with different disease states, uplifting their value in interventional studies.3

Due to their ease-of-use, as well as their ability to provide medical professionals with more candid insights on the health of their patients, PROMs have seen a massive uptick in utilization across various domains, from drug development studies and clinical trials to everyday practice. The integration of PROMs in clinical practice and research have been shown to enhance physician-patient relationships, improve communication, and influence decision-making.4,5

While PROMs have been employed in many medical specialties, the field of urology was a relatively early adopter of PROMs. As early as the 1990s urology incorporated PROMs to better assess patient experiences related to urinary and sexual wellness.

With the ubiquitous use of PROMs in healthcare, their increased utilization reflects a broader trend toward patient-centered research and delivery of care. Understanding how PROMs were developed throughout history provides insights into how these tools contributed to the evolution of patient-centered care and can guide the development of more effective patient-centered assessment tools in the future. This paper serves as a historical review into the emergence and growth of PROMs, particularly in the field of urology. Furthermore, this paper also details the development of the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF), a pivotal PROM that has significantly impacted the assessment and treatment of erectile dysfunction (ED).

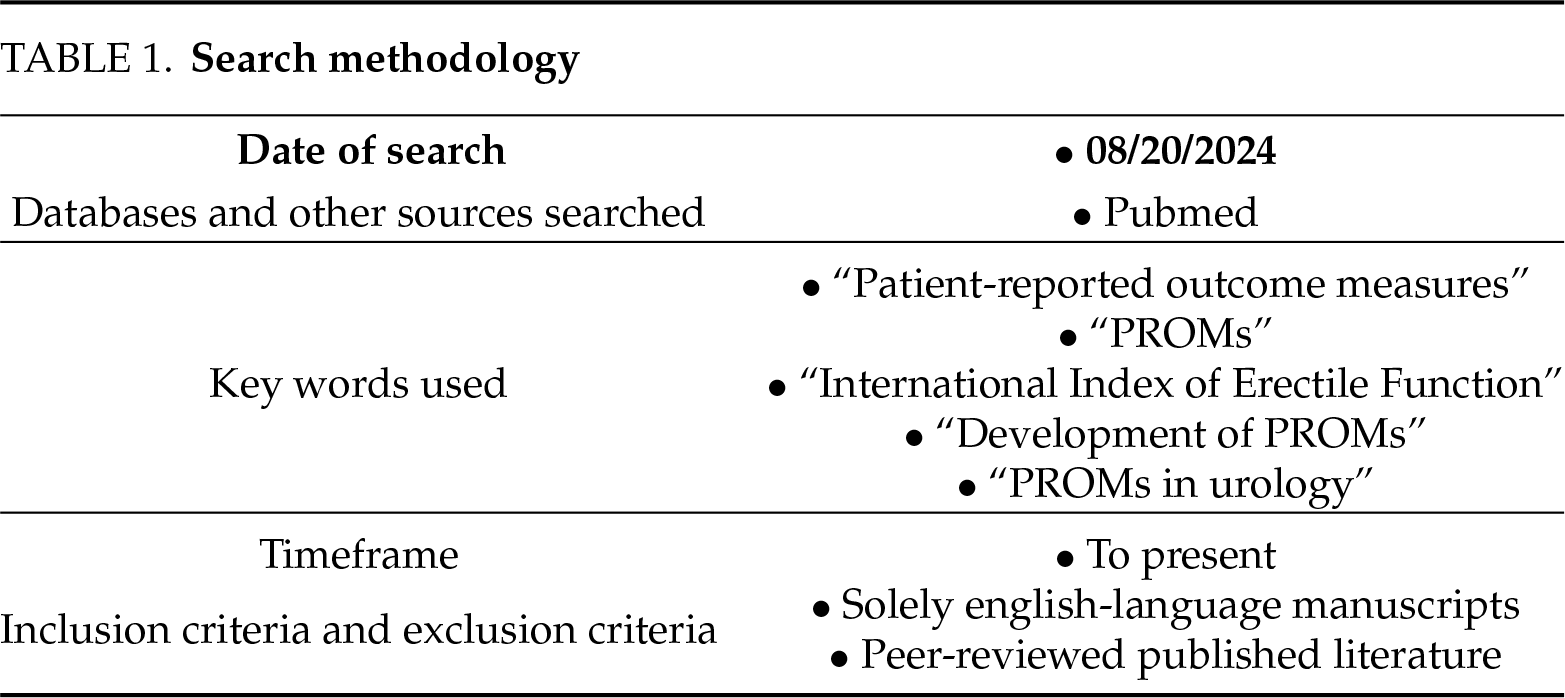

This paper leveraged PubMed database searches for relevant articles to determine the history of PROMs, as well as their use and development in the field of urology. As a historical review that aims to focus on the development and use of PROMs in medicine, particularly urology, this paper aims to focus on important literature that served as foundations for the use of PROMs in practice and research, rather than a comprehensive systematic synthesis. Our search methodology is detailed in Table 1. We only included articles in English. 514 total articles were identified based on keywords, and with author consensus based on discussion around key milestones, developments, and applications of PROMs in medicine, 26 articles were chosen. We also contacted and conducted an oral interview with Dr. Raymond Rosen, 1st author of the seminal paper that proposed the International Index of Erectile Function, on August 9th, 2024, for his personal insights into the history of PROMs in medicine and sexual health, including specific details on the creation process of the IIEF.

Some of the first PROMs were developed during the 1970s and represented a gradual shift in interest toward health-related quality of life. The Sickness Impact Profile (SIP) and the Nottingham Health Profile (NHP) represent two of the earliest high-profile PROMs.6,7 The SIP, conceived in 1976, comprehensively covers the impact of a patient’s illness on their daily life through 136 items that span 12 categories divided by two dimensions: Physical and Psychosocial. Each item in the SIP is scored as either a “yes” or “no”. This allowed for domain-specific scores and an overall score, expressed in a percent, with higher overall scores corresponding to a more significant impact of a patient’s disease on their daily functioning.6 The NHP similarly sought to examine health-related quality of life in an accessible manner through physical, emotional, and social measures, answered in a binary yes-no format, to offer insights into a patient’s daily functioning.7

The well-known Short Form-36 (SF-36) Survey is one of the most widely used PROMs to assess quality of life in diverse patient populations. The development of the SF-36 first began during the RAND Health Insurance Experiment, one of the most significant health policy studies that sought to understand the effects of different health insurance policies on healthcare costs, utilization, and outcomes.8 However, the formal SF-36 was not fully validated until the NIH-funded General Health Survey of the Medical Outcomes Study conducted by the RAND Corporation in 1988, where it was designed to be used across many diseases and populations.8 The SF-36 was officially published in 1992.9 Over time, the SF-36 has seen pervasive utilization in both clinical and research settings, owing to its ease of use, the relatively brief number of questions, and simple scoring method.

In parallel, researchers sought to develop measures designed to address specific diseases. The Health Assessment Questionnaire, developed by Fries et al., at Stanford University in 1978, was among the first to spearhead this initiative, measuring the daily functioning ability of patients with rheumatoid arthritis.10 Many fields soon followed with an expansion of condition-specific PROMs.

PROMs in Urology, Sexual Medicine, and the International Index of Erectile Function

PROMs began to impact the field of urology in the early 1990s. The International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS), also known as the American Urological Symptom Index, assesses lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) associated with benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH).11 Repeated measures of the IPSS provided a way for clinicians to measure the impact that treatments for BPH, such as alpha-blockers or transurethral resection, had on a patient’s quality of life. The IPSS is a standard metric and often the primary endpoint for clinical trials evaluating BPH treatments. The IPSS has been translated and validated across 40 languages, providing widespread applicability across different global contexts.12

Before PROMs, the field of sexual medicine incorporated physiological assessments of erectile function, such as penile strain gauges, to measure changes in penile rigidity and circumference.13 However, such devices were complicated and considered by patients to interfere with normal sexual function thus impairing accuracy. Implementation of these physiologic measures was impractical. Alternative measures were needed that would accurately capture the patient’s erectile function. PROMs offered a less obtrusive alternative and, over time, wholly replaced physical measurements of sexual health. They provided ecological validity and gave clinicians reliable data surrounding a patient’s sexual health.

In 1993, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Consensus Development Conference created a standard definition of ED. It strongly recommended the creation of more reliable methods for assessing ED symptoms and treatment outcomes.14 Around the same time, Pfizer was performing clinical trials surrounding the use of sildenafil for ED treatment. In this environment, the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF), developed by Rosen et al. in collaboration with Pfizer in 1997, was a pivotal milestone for the use of PROMs in urology.15

The objective of the IIEF, as described by Rosen et al., was “to develop a brief, reliable, self-administered measure of erectile function that is cross-culturally valid and psychometrically sound, with the sensitivity and specificity for detecting treatment-related changes in patients with erectile dysfunction”.15 Indeed, to this day, the IIEF continues to be seen as the benchmark measurement tool in research studies and clinical trials regarding ED treatments due to its high validity and reliability. To date, the IIEF has been linguistically validated in over 30 languages, making it widely applicable for ED assessments across diverse populations.16 Modifying the IIEF into the IIEF-5, or the Sexual Health Inventory for Men, shortened from fifteen to five items in 1999, further enhanced its use in clinical practice.17

To enhance its applicability in clinical trials and patient management settings, the IIEF criteria needed to be able to distinguish minimally important clinical differences (MCID). MCIDs in this context are critical for helping physicians and investigators assess whether changes in IIEF score result in tangible improvements or declines in a patient’s erectile function. Seminal papers by Yang et al. and Rosen et al. defined and validated threshold changes in IIEF scores that represent clinically meaningful improvements or declines in erectile function using both anchor-based methods which rely on external references, such as patient- or clinician-reported outcomes, to determine a threshold for meaningful change, and distribution-based methods, which use statistical parameters, such as effect sizes, standard errors of measurement, and variability estimates, to define minimum clinically significant changes.18,19 This is particularly important to note, as the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and other regulatory agencies emphasize the derivation of these metrics to aid in the design and interpretation of clinical trials.

The construct validity of the IIEF has been consistently proven through various studies. Among the more noteworthy validation efforts is Flynn et al.’s research, which not only developed sexual function and satisfaction measures under the NIH’s Patient-Reported Outcomes Measure System Information System (PROMIS) initiative but also demonstrated a strong correlation between the IIEF and these PROMIS measures for erectile function.20 This important cross-validation provides compelling evidence that the IIEF accurately captures the underlying construct of sexual function, reinforcing its utility in diverse clinical contexts, including oncological settings.

When asked about the evolution of the measure and what was planned for or anticipated at the time of its first use in the 1990s, Dr. Raymond C. Rosen said the following about the adoption in urology and widespread use of the IIEF:

“I was surprised at the speed of adoption of the IIEF—and especially its abbreviated form, the SHIM (5-item version)—into sexual medicine and urological practices broadly. Many urology offices in the early 2000s began routinely to incorporate the IIEF in their standard patient information assessments. The scale saved time during the clinical interview, provided documentation, ensured that the essential ED information was collected, and opened the way to further enquiry and goal-oriented communication between the physician and patient.”

As he further stated: “Many traditional PROMs, from depression assessment measures to quality-of-life assessments, evolve towards briefer versions of the original scale. Not surprisingly, therefore, I was approached by the Viagra team at Pfizer in 1998, the year Viagra was approved in the U.S., to assist them in developing a short version of the scale. I expressed skepticism at the time, especially about the accuracy or sensitivity of a very brief scale. Boy, was I wrong!”

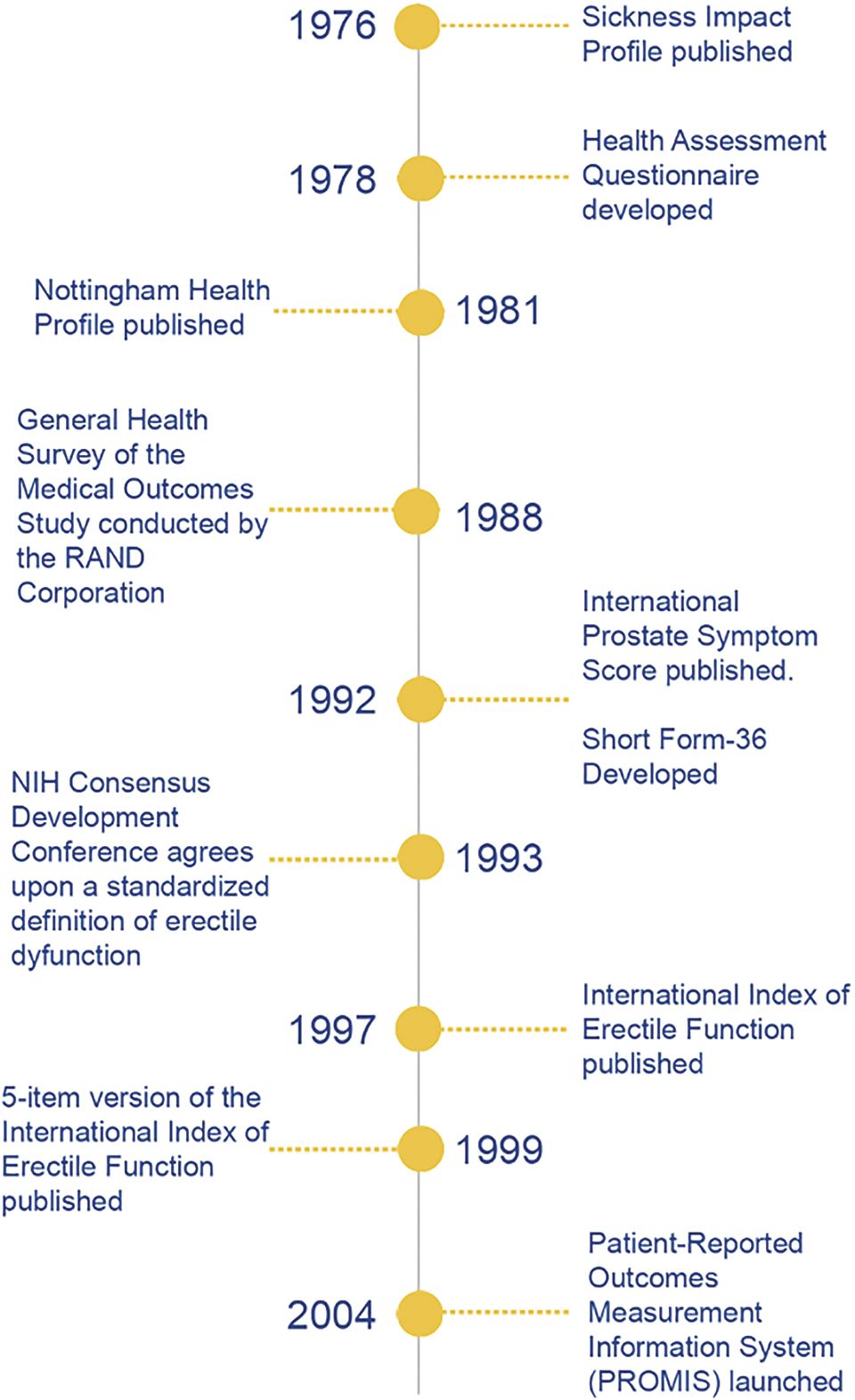

Dr Rosen elaborated on this outcome: “Over time, the IIEF-5 became a valuable clinical research tool (the data are easy to analyze and report). The scale was useful for clinical assessment particularly, and to open communication about sexual and urological health issues, often sensitive topics for patients and practitioners, as well as offering clinicians a convenient metric to document the presence and severity of ED.” Figure 1 depicts key events in the history of PROMs and their integration into urology.

FIGURE 1. Timeline of key events in the development of patient-reported outcome measures

While the IIEF has proven its utility over time, it does have important limitations. Dr. Rosen listed some of these:

“The IIEF was developed in conjunction with the earliest clinical trials of sildenafil, in the mid-1990s, and the scale was designed and engineered specifically to show the efficacy of the drug in randomized clinical trials conducted in naturalistic or ‘at-home’ settings. The measure and zeitgeist of the regulatory bodies at that time, could with the benefit of hindsight, be criticized as “heteronormative”, in the sense that gay or sexually inactive men were excluded from the trials, as were men not in a stable partner relationship. With regulatory approval, the company (Pfizer) designed their phase 2 and phase 3 sildenafil efficacy trials accordingly.”

Over time, further iterations of the original IIEF scale and scoring algorithms have been proposed, as noted by Dr. Rosen. Other researchers have sought to make modifications to the original IIEF scale to render it more universally applicable, including for men who use intracavernosal injections, or those who do not engage in sexual intercourse for various reasons.21 Vickers et al. recommend modifications—such as addressing non-intercourse sexual activity—to improve the scale’s accuracy and clinical relevance in diverse patient groups.21 These scale modifications, if adopted, would aim to make ED assessment more equitable and applicable to all men, regardless of gender or sexual orientation, active treatment status, and whether they are partnered or sexually active. Further validation, however, is needed before adoption recommendations can be made regarding modified forms of the original scale.

Outside of the IIEF, more recently, PROMs are continuing to be developed in the field of urology, which surrounds a multitude of different conditions and outcomes. Joshi et al. detailed the development of a PROM to better quantitatively assess the quality of life in patients who are receiving treatments for urinary calculi.22 PROMs that address ureteral stricture surgery outcomes and domains of interest in hypospadias care have also been developed in recent years.23,24 Importantly, in prostate cancer, considerable work has been done to develop standardized outcome measures for research and clinical practice. Both the International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement (ICHOM) Standard Set for Prostate Cancer and the PIONEER Core Outcome Set serve to recommend validated PROMs to provide better insight into how prostate cancer and its treatments can affect patients’ quality of life.25,26

It is evident that both the IIEF and its shorter IIEF-5 counterpart have played essential roles in advancing the field of sexual medicine, establishing themselves as the gold standard for assessing ED in both clinical and research settings. The adoption of the IIEF into electronic health records has further increased its usability and accessibility. For the development of innovative treatments to combat ED, the IIEF continues to serve as an essential aspect of clinical research in urology. Additionally, the IPSS continues to see widespread use as a critical PROM, with the American Urological Association (AUA) recommending the use of the tool as one of the first evaluative steps for patients presenting with LUTS that can be attributed to BPH.27 Together, these two PROMs are among the most widely utilized in the field of urology.

Ultimately, the future is encouraging for the use of PROMs, both in urology and the broader field of medicine. PROMs do continue to face limitations, as earlier discussed, such as limited scope, implementation challenges, and cultural barriers. However, with the development of key initiatives like PROMIS by the NIH to further provide reliable data regarding how patient-reported outcomes affect the quality of life among various chronic illnesses, there is ample opportunity for PROMs to further benefit the spheres of clinical care and research.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Dr. Raymond C. Rosen for providing advice throughout the research and writing process. We would like to thank the reviewers of this paper for providing helpful feedback.

Funding Statement

The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Ankith P. Maremanda: Conceptualization, Investigation, Visualization, Writing—Original Draft; Anna Faris: Writing—Review and Editing, Supervision; Benjamin N. Breyer: Conceptualization, Writing—Review and Editing, Supervision. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials

Not applicable.

Ethics Approval

This study was granted an IRB exemption (Study # 25-44376), not human subjects research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Churruca K, Pomare C, Ellis LA et al. Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMsa review of generic and condition-specific measures and a discussion of trends and issues. Health Expect 2021 Aug;24(4):1015–1024. doi:10.1111/hex.13254. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. McKenna SP, Heaney A, Wilburn J, Stenner AJ. Measurement of patient-reported outcomes. 1: the search for the Holy Grail. J Med Econ 2019 Jun;22(6):516–522. doi:10.1080/13696998.2018.1560303. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Thompson D, Bensley JG, Tempo J et al. Long-term health-related quality of life in patients on active surveillance for prostate cancer: a systematic review. Eur Urol Oncol 2023 Feb;6(1):4–15. doi:10.1016/j.euo.2022.09.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Detmar SB, Muller MJ, Schornagel JH, Wever LD, Aaronson NK. Health-related quality-of-life assessments and patient-physician communication: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2002 Dec 18;288(23):3027–3034. doi:10.1001/jama.288.23.3027. Erratum in: JAMA. 2003 Feb 26;289(8):987. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Basch E, Deal AM, Dueck AC et al. Overall survival results of a trial assessing patient-reported outcomes for symptom monitoring during routine cancer treatment. JAMA 2017 Jul 11;318(2):197–198. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.7156. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Bergner M, Bobbitt RA, Carter WB, Gilson BS. The sickness impact profile: development and final revision of a health status measure. Med Care 1981 Aug;19(8):787–805. doi:10.1097/00005650-198108000-00001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Hunt SM, McEwen J, McKenna SP. Measuring health status: a new tool for clinicians and epidemiologists. J R Coll Gen Pract 1985 Apr;35(273):185–188. [Google Scholar]

8. Tarlov AR, Ware JE, Greenfield S, Nelson EC, Perrin E, Zubkoff M. The medical outcomes study: an application of methods for monitoring the results of medical care. JAMA 1989;262(7):925–930. doi:10.1001/jama.262.7.925. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Ware JEJr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 1992 Jun;30(6):473–483. doi:10.1097/00005650-199206000-00002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Fries JF, Spitz P, Kraines RG, Holman HR. Measurement of patient outcome in arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1980 Feb;23(2):137–145. doi:10.1002/art.1780230202. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Barry MJ, Fowler FJJr, O’Leary MP et al. The American urological association symptom index for benign prostatic hyperplasia. The measurement committee of the American urological association. J Urol 1992 Nov;148(5):1549–1557. doi:10.1016/s0022-5347(17)36966-5. discussion 1564. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. de la Rosette JJ, Alivizatos G, Madersbacher S et al. EAU guidelines on benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). Eur Urol 2001 Sep;40(3):256–263. doi:10.1159/000049784. discussion 264. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Barlow DH, Becker R, Leitenberg H, Agras WS. A mechanical strain gauge for recording penile circumference change. J Appl Behav Anal 1970;3(1):73–76. doi:10.1901/jaba.1970.3-73. Spring. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. NIH Consensus Conference. Impotence. NIH consensus development panel on impotence. JAMA 1993 Jul 7;270(1):83–90. [Google Scholar]

15. Rosen RC, Riley A, Wagner G, Osterloh IH, Kirkpatrick J, Mishra A. The International Index of Erectile Function (IIEFa multidimensional scale for assessment of erectile dysfunction. Urology 1997 Jun;49(6):822–830. doi:10.1016/s0090-4295(97)00238-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Rosen RC, Cappelleri JC, Gendrano N. The International Index of Erectile Function (IIEFa state-of-the-science review. Int J Impot Res 2002 Aug;14(4):226–244. doi:10.1038/sj.ijir.3900857. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Rosen RC, Cappelleri JC, Smith MD, Lipsky J, Peña BM. Development and evaluation of an abridged, 5-item version of the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5) as a diagnostic tool for erectile dysfunction. Int J Impot Res 1999 Dec;11(6):319–326. doi:10.1038/sj.ijir.3900472. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Yang M, Ni X, Sontag A, Litman HJ, Rosen RC. Nonresponders, partial responders, and complete responders to PDE5 inhibitors therapy according to IIEF criteria: validation of an anchor-based treatment responder classification. J Sex Med 2013 Dec;10(12):3029–3037. doi:10.1111/jsm.12335. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Rosen RC, Allen KR, Ni X, Araujo AB. Minimal clinically important differences in the erectile function domain of the International Index of Erectile Function scale. Eur Urol 2011;60(5):1010–1016. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2011.07.053. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Flynn KE, Lin L, Cyranowski JM et al. Development of the NIH PROMIS® Sexual Function and satisfaction measures in patients with cancer. J Sex Med 2013 Feb;Suppl 1(1):43–52. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02995.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Vickers AJ, Tin AL, Singh K, Dunn RL, Mulhall J. Updating the International Index of Erectile Function: evaluation of a large clinical data set. J Sex Med 2020 Jan;17(1):126–132. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2019.10.020. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Joshi HB, Johnson H, Pietropaolo A et al. Urinary stones and intervention quality of life (USIQoLdevelopment and validation of a new core universal patient-reported outcome measure for urinary calculi. Eur Urol Focus 2022 Jan;8(1):283–290. doi:10.1016/j.euf.2020.12.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Boehm D, Nolla K, Naser-Tavakolian A et al. Development of a patient-reported outcome measure for patients with ureteral stricture disease. Urology 2025 Feb;196:272–278. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2024.10.054. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Brown C, Larson K, Cockrum B et al. Development of a prototype of a patient-reported outcomes measure for hypospadias care, the patient assessment tool for hypospadias (PATH). J Pediatr Urol 2024 Dec;20(6):1072–1081. doi:10.1016/j.jpurol.2024.07.028. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Morgans AK, van Bommel AC, Stowell C et al. Advanced prostate cancer working group of the international consortium for health outcomes measurement. Development of a standardized set of patient-centered outcomes for advanced prostate cancer: an international effort for a unified approach. Eur Urol 2015;68(5):891–898. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2015.06.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Beyer K, Moris L, Lardas M et al. Updating and integrating core outcome sets for localised, locally advanced, metastatic, and nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: an update from the PIONEER consortium. Eur Urol 2022 May;81(5):503–514. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2022.01.042. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Sandhu JS, Bixler BR, Dahm P et al. Management of lower urinary tract symptoms attributed to benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPHAUA Guideline amendment 2023. J Urol 2023. doi:10.1097/JU.0000000000003698. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools