Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Adverse histological features are more commonly observed in hypergonadotropic prostate cancer patients

1 Andrology and Urology Department, Federal State Budget Institution, National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology named after Academician V.I. Kulakov, Moscow, 117997, Russia

2 Obstetrics, Gynecology, Reproductology and Perinatology Department, Federal State Autonomous Educational Institution of Higher Education I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation (Sechenov University), Moscow, 119991, Russia

3 Urology Department, Federal State Budgetary Educational Institution of Higher Education, Russian Biotechnological University, Moscow, 125080, Russia

* Corresponding Author: Taras Shatylko. Email:

Canadian Journal of Urology 2025, 32(6), 561-568. https://doi.org/10.32604/cju.2025.064572

Received 19 February 2025; Accepted 24 September 2025; Issue published 30 December 2025

Abstract

Background: Some patients with prostate cancer have elevated gonadotropin levels. It is unknown, however, whether this condition directly influences carcinogenesis in the prostate. It is also unknown whether any specific hormone levels are useful to predict aggressive disease. The potential role of luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) in prostate physiology is widely discussed. The study aimed to evaluate whether patients with this endocrine pattern have different outcomes following radical prostatectomy. Methods: This was a prospective cohort study of consecutive patients undergoing robot-assisted radical prostatectomy at the Andrology and Urology Department, National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology named after Academician V.I. Kulakov (Moscow) from September to December 2023. After applying exclusion criteria, 60 patients were included and stratified into a hypergonadotropic cohort (upper tertile for LH and FSH; n = 14) and a control cohort (n = 46). Primary outcome was adverse histology defined as ISUP grade ≥ 3 on final pathology. Results: 10 of 14 hypergonadotropic patients (71.4%) and 15 of 46 patients in the control cohort (32.6%) had ISUP grade ≥ 3, and this difference was statistically significant (p = 0.014). The rate of T3 disease on pathology was 42.9% and 32.6% in hypergonadotropic patients and the control cohort, respectively (p = 0.532). No significant correlation was found between PSA and gonadotropin levels. Conclusions: Patients with prostate cancer may have elevated gonadotropin levels, potentially predicting aggressive disease. If validated, these findings could influence clinical decision-making in prostate cancer based on LH and FSH levels.Keywords

Prostate cancer is the second biggest cause of cancer mortality in males after lung cancer, although it makes up only 10% of all incident cancer cases. The majority of men are either diagnosed with localized disease that is limited to the prostate (76%) or with regional disease that has progressed to involvement of regional lymph nodes (13%). Meanwhile, only 6% of men are diagnosed with distant metastases.1 It is a highly prevalent condition that is dependent on male hormonal status. Indeed, most systemic treatment modalities for metastatic prostate cancer are based on endocrine manipulation.

The therapeutic effect of androgen deprivation therapy was first demonstrated in the 1940s. This discovery proved that prostate cancer is an androgen-dependent disease.2 Over the years, hormonal therapy for this disease has progressively improved. Such treatment methods as deprivation of gonadal testosterone, blocking the production of adrenal and other extragonadal androgens, and methods that directly bind and inhibit androgen receptors have been developed.3 It is controversial, however, whether and how any conditions (e.g., hypogonadism or testosterone replacement therapy) directly influence carcinogenesis in the prostate. It is also unknown whether any specific hormone levels are useful to predict aggressive disease.

In our practice, we encountered an unexpectedly high proportion of prostate cancer patients with elevated gonadotropin levels. The potential role of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) in prostate physiology is widely discussed.4 Moreover, increased luteinizing hormone (LH) and FSH levels may be indicative of hypogonadism, extra-pituitary gonadotropin production, or idiopathic pituitary overactivity. There are numerous novel prostate cancer biomarkers, but the “old” molecules, such as gonadotropins, are somewhat overlooked.5 Hence, this study sought to evaluate whether patients with this endocrine pattern have different outcomes following radical prostatectomy.

We conducted a prospective cohort study of consecutive patients who underwent robot-assisted radical prostatectomy at the Andrology and Urology Department, National Medical Research Center for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Perinatology named after Academician V.I. Kulakov, Moscow, between September 1, 2023 and December 31, 2023. Inclusion criteria: patients with histologically confirmed prostate adenocarcinoma scheduled for robot-assisted radical prostatectomy. Exclusion criteria: neoadjuvant hormone therapy, prior 5-alpha-reductase inhibitor use, and prior testosterone replacement therapy. The study protocol was approved by the Local Ethics Committee of I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University (#01082023). All patients provided written informed consent with guarantees of confidentiality.

Participant selection and flow

Patients were screened at preoperative assessment; 60 patients meeting inclusion/exclusion criteria were invited to participate and were consecutively enrolled.

The exposure of interest was a hypergonadotropic endocrine pattern, defined as serum LH ≥ 7.15 IU/L and serum FSH ≥ 10 IU/L (upper tertiles). Fourteen patients were included in this cohort. Other patients comprised the control cohort. Primary outcome was adverse histology on final surgical specimen (ISUP grade ≥ 3). Secondary outcomes included pathological T stage (T3 vs. ≤T2).

Serum hormones (LH, FSH, total testosterone, estradiol) were evaluated using a Cobas e411 analyzer for immunochemistry testing (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland). Blood samples were collected in the morning (08:00–10:00) before surgery, processed and stored according to standard procedures. Prostate volume was assessed by transrectal ultrasound, using HS70A ultrasound scanner (Samsung Medison, Seoul, Republic of Korea). Histopathology (ISUP grade, pathological T stage) was reviewed by one pathologist blinded to hormonal status.

The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess the normality of distribution. Most variables were not normally distributed, except age and testosterone level. Data with normal distribution were presented as mean values and standard deviations (mean ± standard deviation [SD]), and other variables were presented as median values and interquartile ranges (IQRs; median [Q1–Q3]).

Age, endocrine parameters, prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels, prostate volume, stage, and International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) grade6 were compared between the two cohorts. Mann-Whitney U-test was used for non-parametric variables, the Student t-test was used for parametric variables, and Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical variables. Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated for endocrine parameters to account for possible relationships between them. p-values below 0.05 were considered to be significant.

All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS version 26 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). There were no missing values for primary outcomes.

Between September 1 and December 31, 2023, 60 were included in the analysis (hypergonadotropic n = 14; control n = 46). There were no missing values for the primary outcome (ISUP grade) and for key hormonal measurements.

Median LH and FSH levels in both cohorts combined were 5.14 IU/L (95% confidence interval (CI): 4.77–6.99; IQR: 4.1–8.34) and 8.84 IU/L (95% CI: 6.84–9.61; IQR: 5.87–12.52), respectively.

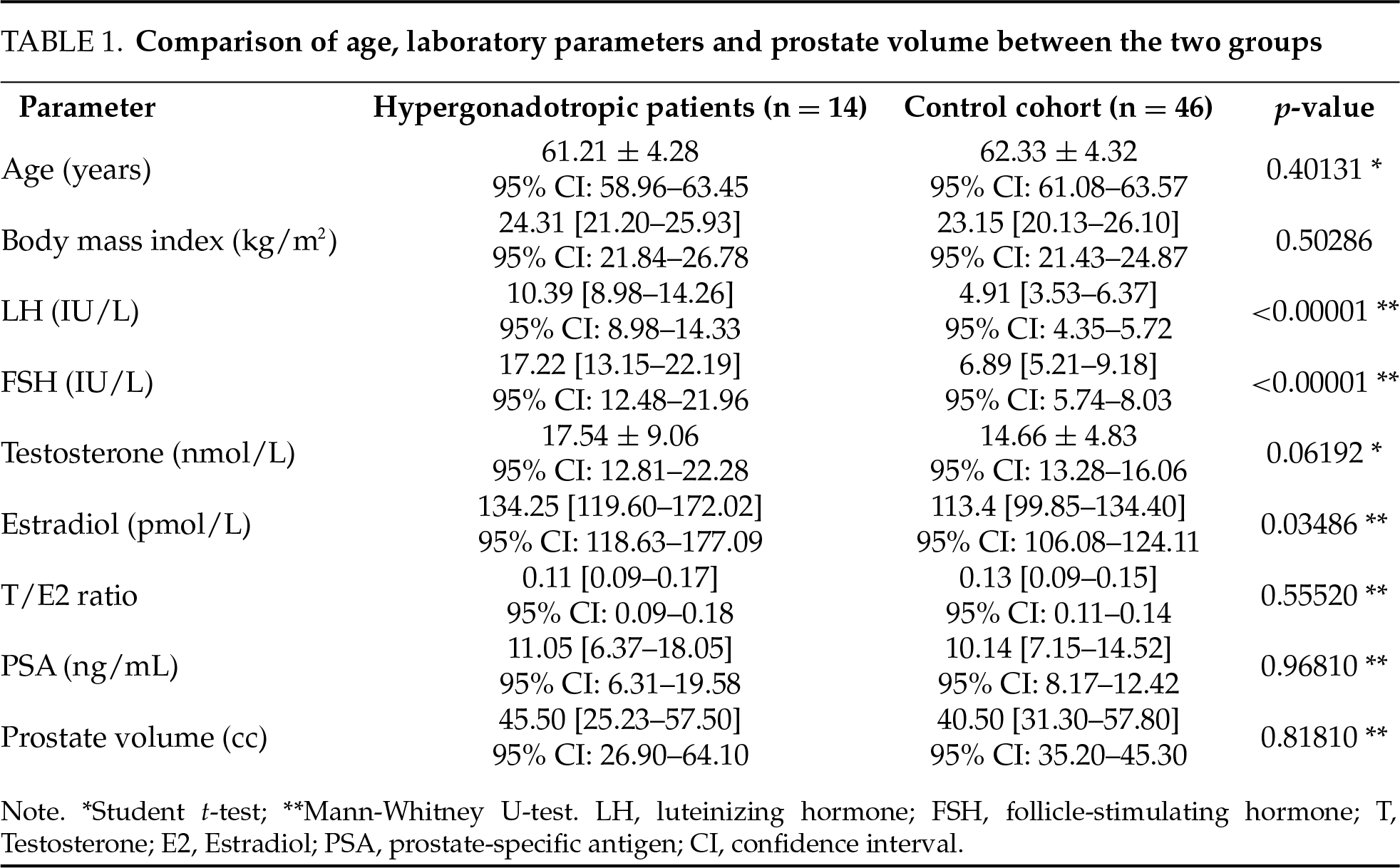

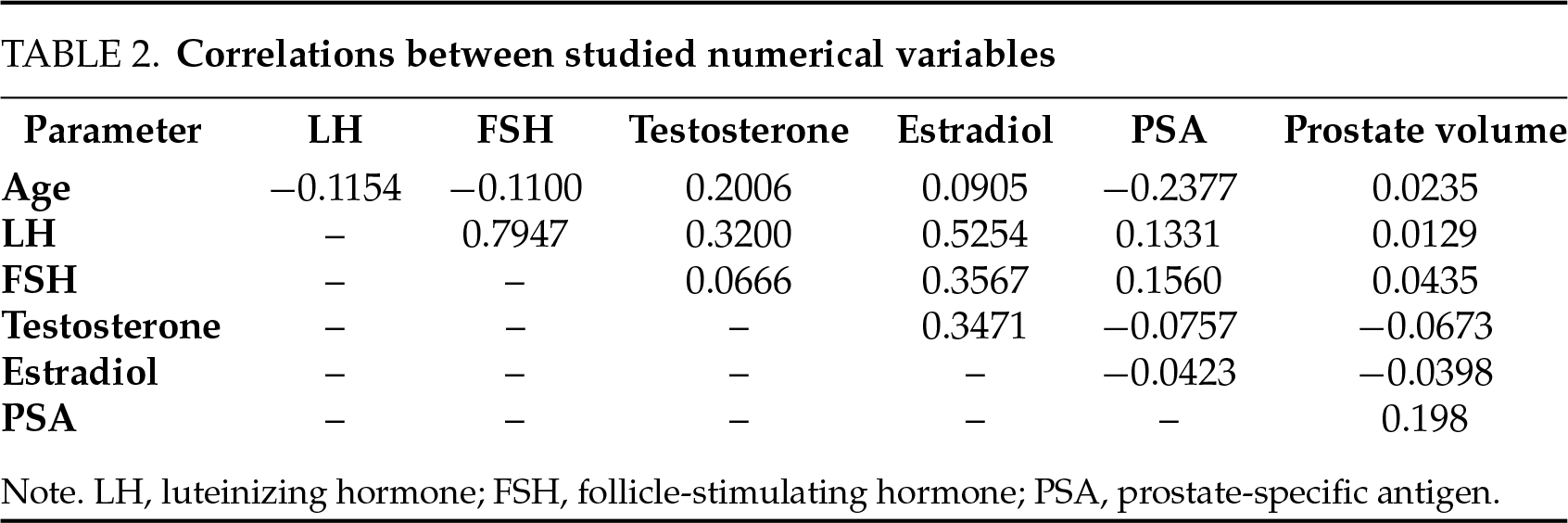

A comparison of basic parameters between the two cohorts is presented in Table 1. The only statistically significant difference, apart from LH and FSH levels, was observed for estradiol levels (p < 0.05).

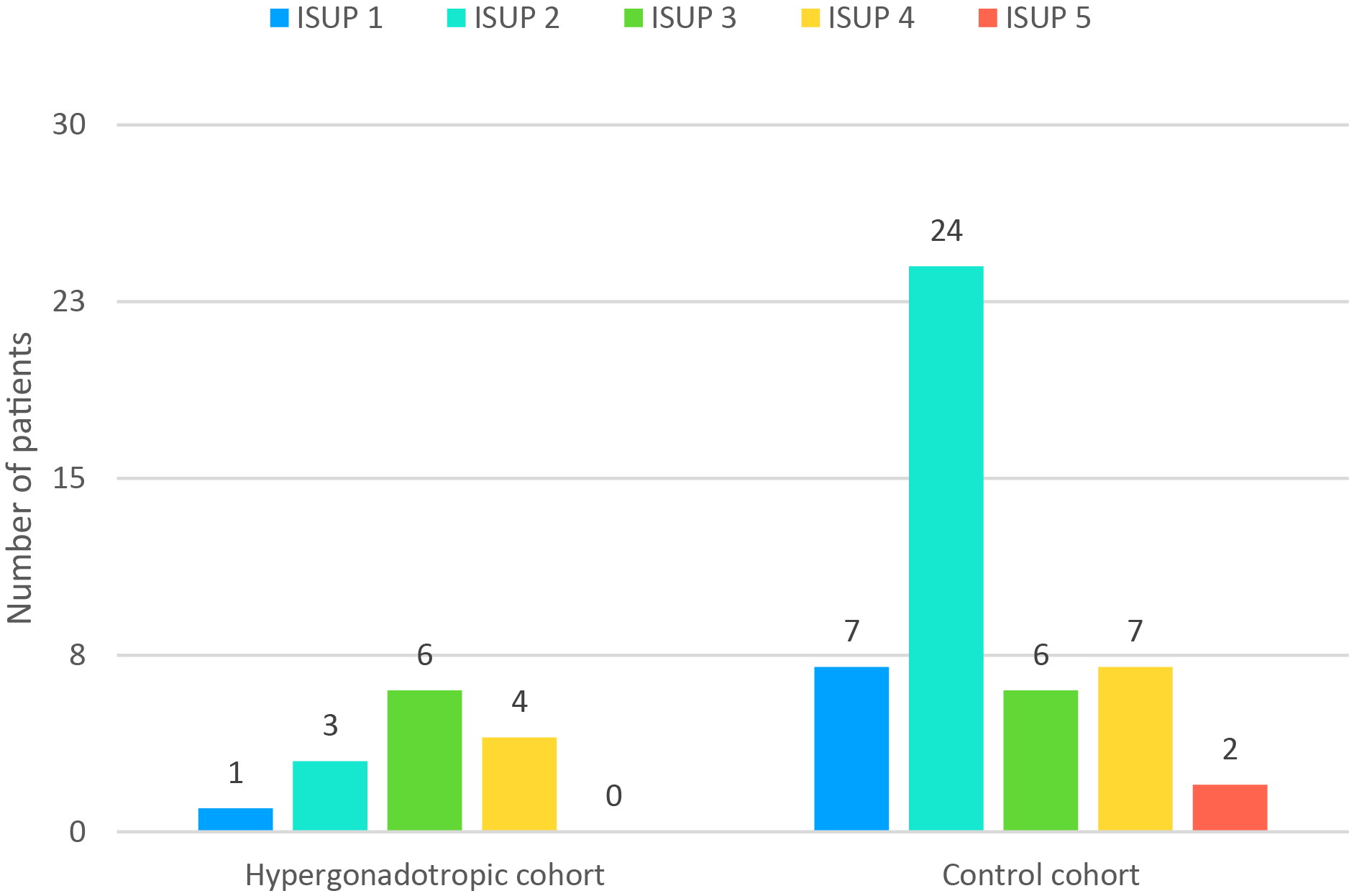

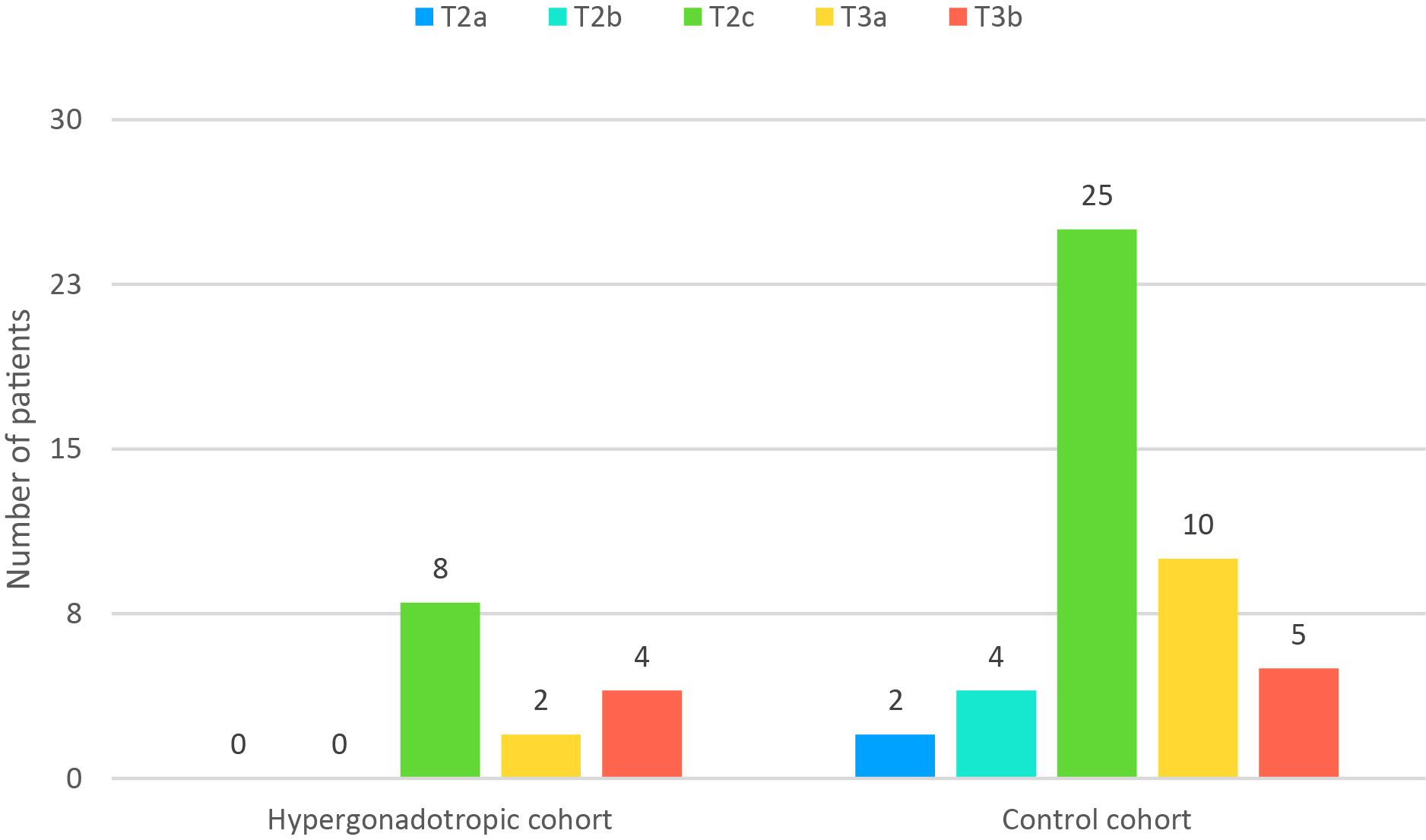

ISUP grades and T stage on final pathology were compared between the two cohorts (Figures 1 and 2, respectively).

FIGURE 1. ISUP grading in the studied cohorts. ISUP, International Society of Urological Pathology

FIGURE 2. Pathological T stage in the studied cohorts

ISUP grade ≥ 3 had 15 of 46 patients in the control cohort (32.6%) and 10 of 14 hypergonadotropic patients (71.4%). This difference was statistically significant (p = 0.014). Of hypergonadotropic patients 42.9% had T3 disease on pathology and in control group it was 32.6% (p = 0.532).

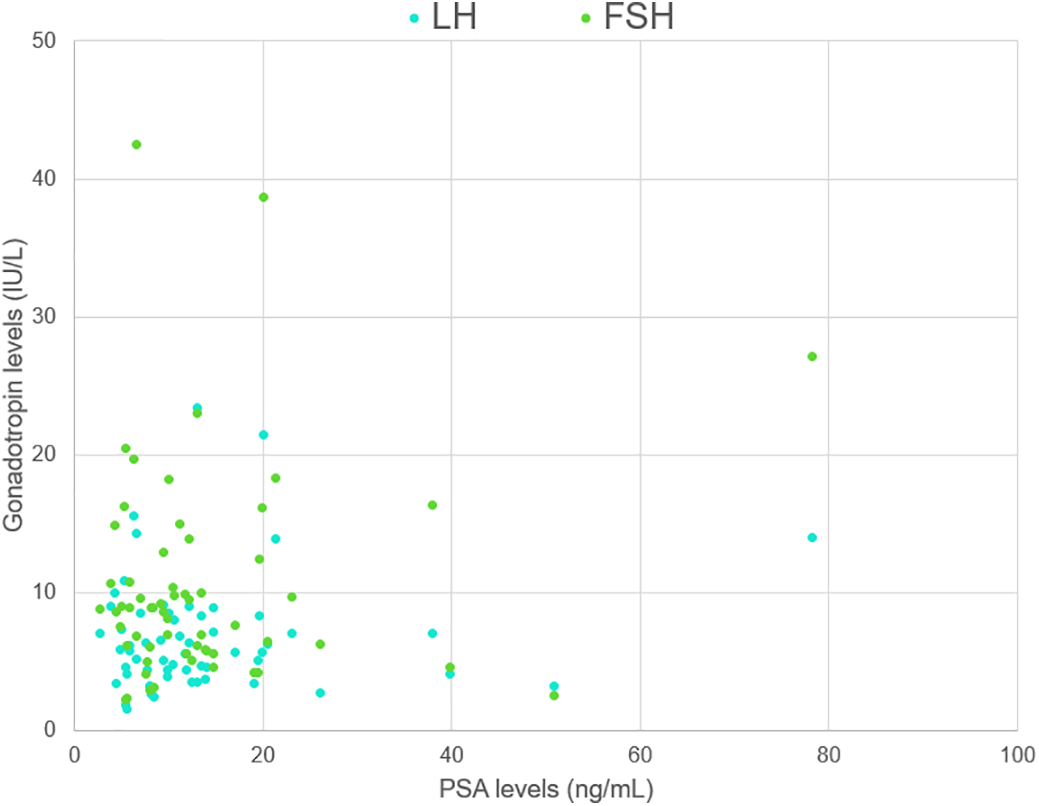

A correlation analysis was performed to evaluate possible linear relationships between the variables, which could have affected the primary results (Table 2). Expected weak-to-moderate correlation was observed between endocrine parameters (e.g., correlation between serum LH and sex steroid levels). Importantly, there was no meaningful correlation between PSA levels and hormone levels (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3. A scatter plot demonstrating the relationship between PSA and gonadotropin levels. LH, luteinizing hormone; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; PSA, prostate-specific antigen

Importantly, only 5 hypergonadotropic patients had testosterone level below 12 nmol/L, and only 2 among them had testosterone level below 8 nmol/L, which means that only a minor portion of them had true hypergonadotropic hypogonadism associated with testicular failure.

Our study demonstrated that some patients with prostate cancer have elevated gonadotropin levels. Only a minor portion of hypergonadotropic patients had low testosterone levels, which separates these cases from true hypogonadism associated with testicular failure. Rather, it could be stated that such patients probably have an overactive hypothalamic-pituitary system. It can also be hypothesized that prostate adenocarcinoma may be a source of extrinsic gonadotropin production. Although we observed a higher incidence of high-grade histology (ISUP ≥ 3) in hypergonadotropic patients, it still needs to be elucidated whether the hypergonadotropic state has any clinical significance in prostate cancer.

There is an opinion that LH and FSH are directly involved in prostate cancer development and progression, including castration-resistant disease.7 Benign and malignant prostate cells may express FSH and FSH receptors.8–10 In the study conducted on human prostate tissue and different animal models by Garde immunoprecipitation of FSH was performed on minced prostate tissue to determine FSH expression. FSH was found in all specimens except normal prostate sections. Interestingly, there was alternating FSH expression pattern in many BPH specimen, indicating different stages of cellular development. They also found decreased tumor growth and FSH levels after 2-week treatment with Prostatic Inhibin Peptide.8 A higher level of FSH/follicle-stimulating hormone receptor (FSHR) expression was demonstrated in aggressive prostate cancer.11,12 Prostate can possibly synthesize autologous FSH and with FSH-R expression that can lead to local circuit, facilitating prostate cancer growth.13

Study by Mariani et al. showed abnormal expression of FSH receptor in prostate cancer cells, whereas normal prostate tissue without signs of cancer or hyperplasia had no or small FSH-receptor mRNA in comparison. Most intense FSH-R expression among BPH specimens was shown in basal epithelial layer and apical region. In prostate cancers expression was diffuse and intense in glandular epithelial cells. In FSH-R-knockout mice there was no influence of FSH on gland organogenesis, but there might be FSH-dependent action on differentiation and secretion. Androgen independent cancer cell line expressed FSH-R gene and FSH-R protein. Contrary, androgen-dependent prostate cancer cells did not have such metabolic activity. In that study was also stated, that there was no correlation between Gleason score and increased FSH-R expression in cancerous tissue. These findings support possible yet undiscovered clinical significance of FSH expression in prostate.11

In one cohort study with 250 patients by Heracek et al. serum levels of FSH were significantly lower in patients with localized prostate cancer than in patients with advanced disease (FSH = 5.63 +/− 0.31 vs. 7.07 +/− 0.65, respectively, p < 0.05).12

An in vitro study by Dizeyi et al. also demonstrated that prostate cancer cells have FSH receptors and FSH stimulates their proliferation. In the same study C4-2, androgen independent cell line, had high basal expression of FSH-R and mRNA. After FSH treatment C4-2 cells showed significant induction of PSA and expression of NKX3.1 gene, regulating prostate development and acting like a tumor suppressor.14 Zhang et al. previously demonstrated decreased expression of prostate inhibin-like protein (PIP) in adenocarcinoma when compared to BPH and normal prostatic tissue. PIP is known to suppress the release and synthesis of FSH in pituitary and prostate itself. It is unlikely, though not impossible, that decreased levels of PIP in patients with aggressive prostate cancer lead to a hypergonadotropic state in absence of hypogonadism.15 Pinthus et al. described that in advanced prostate cancer under androgen deprivation therapy, patients with FSH ≤ 4.8 mIU/mL experience a 54% lower risk of progression to castration resistance (hazard ratio 0.46, 95% CI 0.23–0.73, p = 0.006), which supports possible involvement of FSH in cancer growth pathway16. Porcaro et al. demonstrated that FSH level could be independently predicted by PSA level in patients with prostate cancer and suggested to use FSH/PSA ratio as a tool to identify patients with high risk of progression.17 We were unable to demonstrate any kind of significant correlation between PSA and gonadotropin levels. The same group subsequently assessed FSH/PSA clusters in patients who underwent radical prostatectomy, observing statistically significant relationship with Gleason score in biopsy cores and surgical specimen. Porcaro et al. haven’t described a specific group of patients with exceptionally high gonadotropin levels, but they report that maximum levels of LH and FSH in their cohort were 48 IU/l and 54.8 IU/l, respectively.17

In 2010 elevated expression of FSH-R was reported by Radu et al. in wide spectrum of tumorous tissues such as breast, pancreas, colon, bladder, lung, liver, stomach, ovaryand testis. It was hypothesized, that such expression could also be a consequence of neo-angiogenesis in prostate cancer tissue.18 The role of gonadotropins and gonadotropin receptors has been previously described for the microenvironment of ovarian tumors and also stimulates their growth, survival and metastasis. In case of ovarian cancer FSHR is a plausible novel therapeutic agent.19 Prostate cancer microenvironment remains an area open for further research. Sofikerim et al. observed higher mean levels of serum FSH in prostate cancer patients (7.56 mIU/mL) when compared to patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia (6.06 mIU/mL, p = 0.029) though FSH does not emerge as an independent predictor when analyzed multivariately.20 A small clinical trial examined the use of abarelix, a GnRH antagonist, in prostate cancer patients who developed castration-resistant disease after orchiectomy. The treatment led to a reduction in FSH levels (below 5 mIU/L), supporting the hypothesis that FSH suppression may offer therapeutic benefits in castration-resistant prostate cancer. These findings suggest that GnRH antagonists may exert antitumor effects beyond merely lowering testosterone levels.21

In another recent study by Deiktakis et al. in degarelix and degarelix/flutamide treated mice prostate weight to body weight ratio was regained after addition of FSH treatment by 41% and 11%, respectively. Interestingly, no effect on PSA levels in chemically castrated men was observed after FSH treatment.22

In the recent study by Oduwole was shown effect of recombinant human FSH on degarelix-treated androgen-independent PC-3 and DU145 cell xenografts. FSH supplementation significantly reversed inhibitory effect of degarelix on PC-3 tumor volume (p < 0.05), although that effect was not seen in degarelix-naïve mice (p > 0.05). In the same study elevated FSH-R expression in prostate cancer tissue was confirmed.23

In contrast, Schmitt et al. find no significant FSH differences among men with and without prostate cancer or atypical small acinar proliferation groups.24

A narrative synthesis by Crawford et al. emphasizes that disruptions in the FSH system accompany changes induced by androgen deprivation therapy.25 Gonadotropin therapy is commonly used for male infertility and is thought to be relatively safe. However, one should be wary of its potential effects on the prostate, especially in patients of advanced reproductive age.

It has been suggested that in the setting of prostate cancer, FSH may play a role comparable to that of testosterone. Catarinicchia and Crawford published a case report that described a patient who underwent bilateral orchiectomy and subsequently received abiraterone therapy but demonstrated a PSA response only when degarelix was added. They also hypothesized that FSH may be important in tumor invasion.26 FSH level was also shown to be associated with extraprostatic extension of prostate cancer in a study by Ide et al.27 Surprisingly, well-known markers of aggressive disease—Gleason score and PSA level—were not found to be associated with tumor extension. Of note, mean gonadotropin levels in this cohort were relatively high: 8.22 IU/l and 13.74 IU/l for LH and FSH, respectively. Previously the same group demonstrated higher levels of gonadotropins in men with positive prostate biopsy when compared to men with negative biopsy, as well as in men with Gleason score ≥ 7 when compared to Gleason score < 7.28 Those signs indirectly hint at a possible association between aggressive prostate cancer and hypergonadotropic state, which was demonstrated in our study. Bilateral orchiectomy induces hypergonadotropic hypogonadism, unlike gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) modulators.

However, Beer et al. observed only a minor reduction in PSA level in small cohort of castrate-resistant cancer patients on GnRH antagonist therapy who previously underwent surgical castration as a primary modality of androgen deprivation.29

Hypergonadotropic prostate cancer patients may present a specific group with an increased risk of ISUP upgrading following radical prostatectomy, which could affect clinical decision-making. However, an observational study on 503 patients, who underwent radical prostatectomy by Kourbanhoussen et al. showed no statistically significant difference in terms of ISUP grade and long-term oncological outcomes for patients with serum FSH levels in the highest tertile.30

Robust evidence regarding this potential relationship is required. Moreover, a deeper understanding of prostate cancer pathology reveals that ISUP grading (Gleason grading) is not the only factor that determines its biology and behavior. Some tumors suggested to have different pathways, accelerating their growth and progression. This study supports the idea of establishment of novel treatment modalities regarding prostate cancer.31

The limitations of our study include a relatively low number of participants, its single-center nature, and the tercile-based definition of the hypergonadotropic state, which may not concur with external cohorts. Patients with high ISUP grade could undergo other treatments, such as radiotherapy or antiandrogen therapy. On the other hand, patients with low ISUP grade could enter active surveillance protocol. These factors can influence results and contribute to selection bias. We used a tercile-based definition because common reference ranges for LH and FSH stem from reproductive medicine and may not apply to prostate cancer settings. ISUP grade is just a surrogate endpoint, and aggressiveness of prostate cancer is better judged by measures of recurrence-free and cancer-specific survival, but proper assessment of these outcomes is possible only after many years of follow-up. Finally, potential measurement bias (laboratory assay variability) and selection bias (referral patterns to a tertiary center) might affect the findings.

Patients undergoing radical prostatectomy may have elevated gonadotropin levels not necessarily associated with hypogonadism. In our cohort, such patients have a tendency for higher ISUP grades on final histology. Our results suggest that further studies are required to understand the association between aggressive prostate cancer and gonadotropin levels.

Acknowledgement

None.

Funding Statement

The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Taras Shatylko, Safar Gamidov, Ramazan Mammaev, Gennadiy Sukhikh; data collection: Ruslan Safiullin, Taras Shatylko, Ramazan Mammaev, Tatiana Ivanets, Ilia Rodin; analysis and interpretation of results: Taras Shatylko, Tatiana Ivanets, Ramazan Mammaev; draft manuscript preparation: Taras Shatylko, Kanan Guluzade, Ramazan Mammaev, Ilia Rodin. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials

Data is available on request from the authors.

Ethics Approval

The study was approved by the Local Ethics Committee of I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University (#01082023) and conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki (2013).

Informed Consent

All patients provided written informed consent with guarantees of confidentiality.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. National Cancer Institute. SEER Explorer: an interactive website for SEER cancer statistics; 2022 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Sep 23]. Available from: https://seer.cancer.gov/statistics-network/explorer/application.html?site=1&data_type=1&graph_type=2&compareBy=sex&chk_sex_3=3&chk_sex_2=2&rate_type=2&race=1&age_range=1&hdn_stage=101&advopt_precision=1&advopt_show_ci=on&hdn_view=0&advopt_show_apc=on&advopt_display=2#resultsRegion0 [Google Scholar]

2. Huggins C, Hodges CV. Studies on prostatic cancer. I. The effect of castration, of estrogen and of androgen injection on serum phosphatases in metastatic carcinoma of the prostate. Cancer Res 1941;1(4):293–297. doi:10.3322/canjclin.22.4.232. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Desai K, McManus JM, Sharifi N. Hormonal therapy for prostate cancer. Endocr Rev 2021;42(3):354–373. doi:10.1210/endrev/bnab002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Spaziani M, Carlomagno F, Tenuta M et al. Extra-gonadal and non-canonical effects of FSH in males. Pharmaceuticals 2023;16(6):813. doi:10.3390/ph16060813. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Li K, Wang Q, Tang X et al. Advances in prostate cancer biomarkers and probes. Cyborg Bionic Syst 2024;5:0129. doi:10.34133/cbsystems.0129. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. van Leenders GJLH, van der Kwast TH, Grignon DJ et al. The 2019 international society of urological pathology (ISUP) consensus conference on grading of prostatic carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2020;44(8):e87–e99. doi:10.1097/PAS.0000000000001497. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Crawford ED, Schally AV. The role of FSH and LH in prostate cancer and cardiometabolic comorbidities. Can J Urol 2020;27(2):10167–10173. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

8. Garde SV, Sheth AR, Shah MG, Kulkarni SA. Prostate—an extrapituitary source of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSHoccurrence, localization, and de novo biosynthesis and its hormonal modulation in primates and rodents. Prostate 1991;18(4):271–287. doi:10.1002/pros.2990180402. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Ben-Josef E, Yang SY, Ji TH et al. Hormone-refractory prostate can-cer cells express functional follicle-stimulating hormone receptor (FSHR). J Urol 1999;161(3):970–976. doi:10.1097/00005392-199903000-00073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Sheth AR, Garde SV, Mehta MK, Shah MG. Hormonal modulation of biosynthesis of prostatic specific antigen, prostate specific acid phosphatase and prostatic inhibin peptide. Indian J Exp Biol 1992;30(3):57–161. [Google Scholar]

11. Mariani S, Salvatori L, Basciani S et al. Expression and cellular localization of follicle-stimulating hormone receptor in normal human prostate, benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostate cancer. J Urol 2006;175(6):2072–2077. doi:10.1016/s0022-5347(06)00273-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Heracek J, Urban M, Sachova J et al. The endocrine profiles in men with localized and locally advanced prostate cancer treated with radical prostatectomy. Neuro Endocrinol Lett 2007;28(1):45–52. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

13. Shah MG, Sheth AR. Similarities in the modulation of pituitary and prostatic FSH by inhibin and related peptides. Prostate 1991;18:1–8. doi:10.1002/pros.2990180102. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Dizeyi N, Trzybulska D, Al-Jebari Y, Huhtaniemi I, Giwercman YL. Cell-based evidence regarding the role of FSH in prostate cancer. Urol Oncol 2019;37(4):290. doi:10.1016/j.urolonc.2018.12.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Zhang PJ, Driscoll DL, Lee H-K, Nolan C, Velagapudi SRC. Decreased immunoexpression of prostate inhibin peptide in prostatic carcinoma: a study with monoclonal antibody. Hum Pathol 1999;30:168–172. doi:10.1016/S0046-8177(99)90271-X. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Pinthus J. Follicle stimulating hormone (FSHa potential surrogate marker for androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) oncological and systemic effects. Can Urol Assoc J. 2015;9:226. doi:10.5489/cuaj.2874. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Porcaro AB, Migliorini F, Petrozziello A et al. Investigative clinical study on prostate cancer part VI: follicle-stimulating hormone and the pituitary-testicular-prostate axis at the time of initial diagnosis and subsequent cluster selection of the patient population. Urol Int 2012;88(2):150–157. doi:10.1159/000334596. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Radu A, Pichon C, Camparo P et al. Expression of follicle-stimulating hormone receptor in tumor blood vessels. N Engl J Med 2010;363:1621–1630. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1001283. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Feng F, Liu T, Hou X et al. Targeting the FSH/FSHR axis in ovarian cancer: ad-vanced treatment using nanotechnology and immunotherapy. Front Endocrinol 2024;15:1489767. doi:10.3389/fendo.2024.1489767. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Sofikerim M, Eskicorapcı S, Oruç Ö, Özen H. Hormonal predictors of prostate cancer. Urol Int 2007;79(1):13–18. doi:10.1159/000102906. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Gartrell BA, Tsao C, Galsky MD. The follicle-stimulating hormone receptor: a novel target in genitouri-nary malignancies. Urol Oncol 2013;31(8):1403–1407. doi:10.1016/j.urolonc.2012.03.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Deiktakis EE, Ieronymaki E, Zarén P et al. Impact of add-back FSH on human and mouse prostate following gonadotropin ablation by GnRH antagonist treatment. Endocr Connect 2022;11(6):e210639. doi:10.1530/EC-21-0639. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Oduwole OO, Poliandri A, Okolo A et al. Follicle-stimulating hormone promotes growth of human prostate cancer cell line-derived tumor xenografts. FASEB J 2021;35(4):e21464. doi:10.1096/fj.202002168RR. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. da Silva Schmitt C, Rhoden EL, Almeida GL. Serum levels of hypothalamic-pituitary-testicular axis hormones in men with or without prostate cancer or atypical small acinar proliferation. Clinics 2011;66:183–187. doi:10.1590/S1807-59322011000200001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. David Crawford E, Rove KO, Rick FG et al. The role of the FSH system in the devel-opment and progression of prostate cancer. Am J Hematol Oncol 2014;10(6):5–13. [Google Scholar]

26. Catarinicchia S, Crawford ED. The role of FSH in prostate cancer: a case report. Urol Case Rep 2016;7:23–25. doi:10.1016/j.eucr.2016.03.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Ide H, Inoue M, Nakajima A et al. Serum level of follicle-stimulating hor-mone is associated with extraprostatic extension of prostate cancer. Prostate Int 2013;1:109–112. doi:10.12954/PI.13019. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Ide H, Yasuda M, Nishio K et al. Development of a nomogram for predicting high-grade prostate cancer on biopsy: the significance of serum testosterone levels. Anticancer Res 2008;28:2487–2492. doi:10.1016/s0022-5347(08)61887-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Beer TM, Garzotto M, Eilers KM, Lemmon D, Wersinger EM. Targeting FSH in androgen-independent prostate cancer: abarelix for prostate cancer progressing after orchiectomy. Urology 2004;63(2):342–347. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2003.09.045. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Kourbanhoussen K, Joncas FH, Wallis CJ et al. Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) levels prior to prostatectomy are not related to long-term oncologic or cardiovascular out-comes for men with prostate cancer. Asian J Androl 2022;24:21–25. doi:10.4103/aja.aja_58_21. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Okubo Y, Sato S, Terao H et al. Review of the developing landscape of prostate biopsy and its roles in prostate cancer diagnosis and treatment. Arch Esp Urol 2023;76(9):633–642. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools