Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Implementation of opioid-reduced protocols after penile prosthesis surgery

1 Department of Urology, West Virginia University, Morgantown, WV 26505, USA

2 Department of Urology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA 22903, USA

3 Department of Orthopedic Surgery, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA 22903, USA

4 Department of Urology, University of Alabama-Birmingham, Birmingham, AL 35294, USA

* Corresponding Author: Nicolas Martin Ortiz. Email:

Canadian Journal of Urology 2025, 32(6), 621-626. https://doi.org/10.32604/cju.2025.065217

Received 07 March 2025; Accepted 13 June 2025; Issue published 30 December 2025

Abstract

Background: Postoperative pain management after penile prosthesis (PP) has traditionally required opioid medication. Recently, urologic prosthetic surgeons have sought to establish opioid-free protocols (OFP) and/or opioid-reduced protocols (ORP) for PP postoperative pain management. We sought to investigate the adoption patterns of OFP/ORP among surgeons who perform PP surgery and identify barriers to implementation. Methods: A 13-question confidential survey was sent to members of the Sexual Medicine Society of North America (SMSNA) and the Society of Urologic Prosthetic Surgeons (SUPS) via email. The survey was administered via Qualtrics. A t-test was used to analyze survey responses. Results: The survey was fully completed by 53 respondents. Approximately 51% (27/53) of respondents performed more than 30 implants annually. OFPs were used at least some of the time by 43% (23/53) of respondents, with 9.5% (5/53) exclusively using OFPs. In comparison, 83% (44/53) of respondents used an ORP at least some of the time, and 32% (17/53) exclusively used ORP. Of the non-opioid medications/techniques used, acetaminophen was the most common (96%, 51/53), followed by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (92%, 49/53) and dorsal penile block (77%, 41/53). At the time of discharge, 75% (40/53) of respondents prescribed fewer than 10 doses of opioid medication, and 15% (8/53) did not prescribe any opioids. The majority of respondents using ORP/OFP were extremely satisfied (70%, 33/47), and none of the respondents were either somewhat or extremely dissatisfied. Conclusion: Our study demonstrates that opioid-reduced/opioid-free regimens are widely adopted among the prosthetic urologic community. These protocols limit narcotic exposure to protect patients from adverse events related to opioids.Keywords

It is estimated that more than two million people suffered from opioid use disorder in 2017, and more than 47,000 people died secondary to opioid abuse in 2018.1,2 A significant portion of these patients can attribute their initial exposure to prescription opioids,3,4 with a significant risk of going on to experiment with synthetic opioids and heroin.5 Post-operative pain management strategies have been linked to opioid abuse, with men and elderly patients at the highest risk of developing addiction.3 Regardless of the initial exposure, it is estimated that the US spends more than $50 billion on the prescription opioid epidemic each year.6

Urology as a specialty is not exempt from this problem, and there has been a call to action to change opioid prescribing practices.7–9 Besides major abdominal surgeries such as open cystectomy, nephrectomy, and retroperitoneal lymph node dissection (RPLND), penile prosthesis (PP) placement is one of the most common urologic procedures associated with post-operative opioid prescriptions.9 In addition, there is data to support that the amount of narcotics used in the hospital and the number of opioid doses prescribed at discharge are associated with persistent opioid use following PP surgery.10,11

As a response to this challenge, urologic prosthetic surgeons have developed and published several multimodality opioid-free protocols (OFP) and/or opioid-reduced protocols (ORP) that prioritize the use of local anesthesia, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), acetaminophen, and neuromodulator medications following PP placement.12,13 While the implementation of these protocols appears to be beneficial for all parties, barriers to implementation may include inadequate postoperative pain control, patient dissatisfaction, and increased administrative burden due to more patient phone calls and medication refill requests. In this study, we investigate the adoption of ORP or OFP among urologic surgeons who perform PP surgery. Additionally, we aim to identify potential barriers to the implementation of ORP/OFP.

The study protocol was approved as exempt by the Institutional Review Board on 8/9/2021. An anonymous survey was sent out to the members of the Sexual Medicine Society of North America (SMSNA) and the Society of Urologic Prosthetic Surgeons (SUPS) via email. Informed consent exemption: Questionnaire completion constitutes consent for anonymous data aggregation. In addition, the survey was shared on the social media platform X (previously known as Twitter). The survey was administered via Qualtrics (XM). There were 13 questions included in the survey. Survey questions included general demographic information, years of clinical experience, surgical approach to PP placement, location of reservoir placement, and post-operative pain management practices following PP placement. OFP was defined as having a post-operative pain regimen completely exempt from narcotics. The term ORP was intentionally left undefined to allow survey respondents to provide their interpretation. A full list of survey questions can be found in Appendix A. Responses were collected from July to November 2021. Student’s t-test was used to compare results among groups, with p-value < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

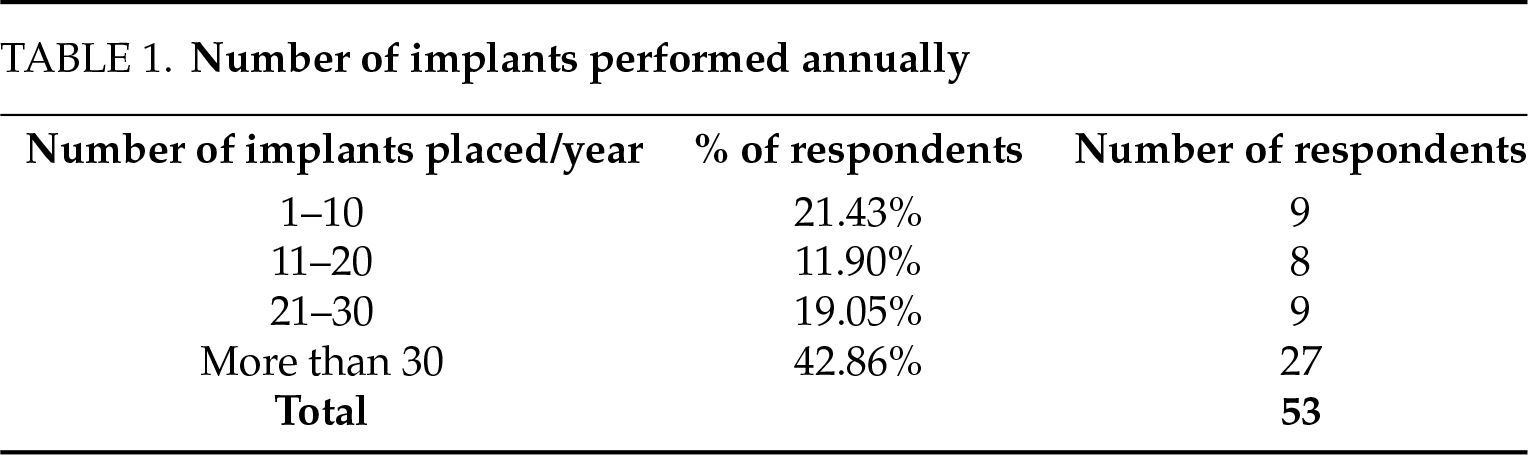

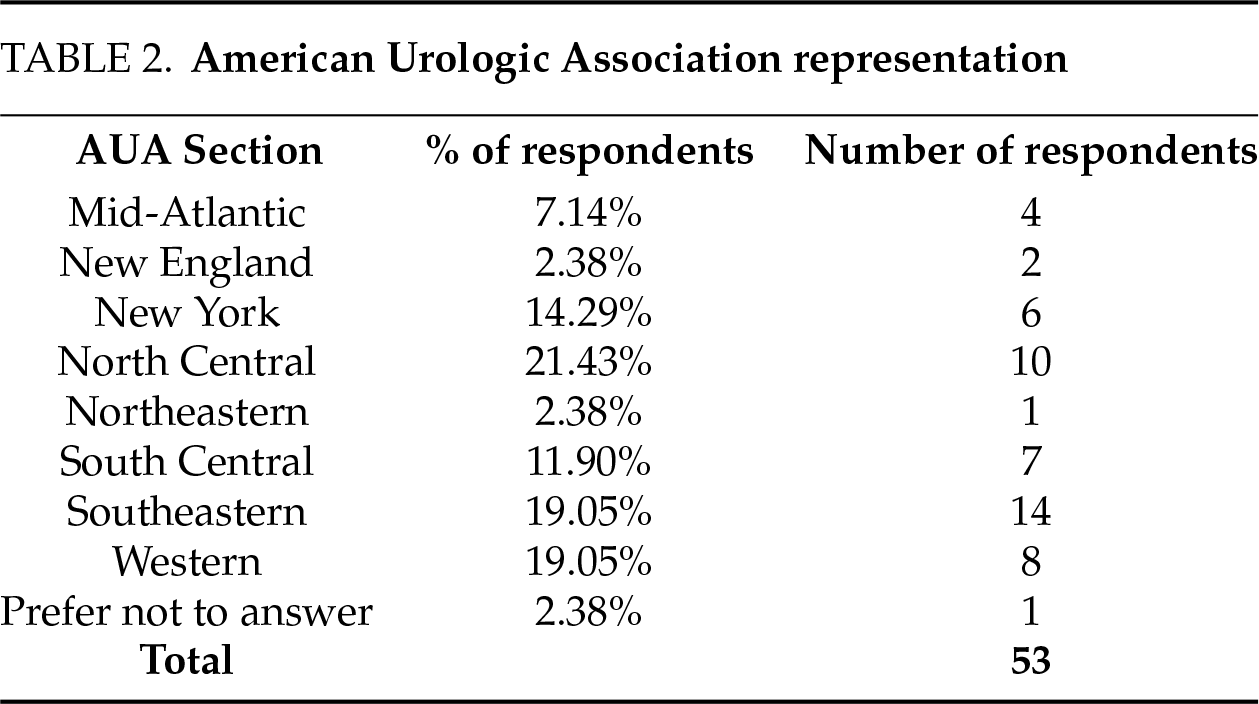

A total of 53 respondents completed the entire survey. There were respondents from all sections of the American Urological Association. No identifying data will be collected as part of this project—all responses will be anonymous. The median time in practice of respondents was 4 years (IQR 2–8.5), and 51% of them performed more than 30 PP per year (Table 1). The AUA sections with the greatest number of responses were Southeastern (26%, 14/53), followed by North Central (19%, 10/53) and Western (15%, 8/53) (Table 2).

Penoscrotal was the most common approach, with 100% of respondents using it at least sometimes and 26% (14/53) using this technique exclusively. The infrapubic approach was less commonly used, with 30% (16/53) of respondents stating they use this approach for most of their placements and only one of the respondents using it exclusively. When asked about the subcoronal approach, only 36% (19/53) of respondents stated they used this approach 1%–25% of the time, with 64% (34/53) stating they never utilized this technique.

Reservoir placement in the retropubic space (of Retzius) was most often used (62%, 33/53), followed by high submuscular space placement (24%, 13/53). Only 21% (11/53) of respondents stated that they utilized locations other than the retropubic or high submuscular space. These “ectopic” spaces included a counter incision, midline, lateral retroperitoneal space, and low submuscular space.

Most survey respondents reported using an Opioid Reduced Protocol (83%, 44/53), and 32% (17/53) reported exclusively using ORP. Opioid-free protocols were less common, with 21% (11/53) of respondents using them often and only 9.5% (5/53) using OFP exclusively. At hospital discharge, most surveyed surgeons prescribed ten doses or fewer of opioid medication (87%, 46/53).

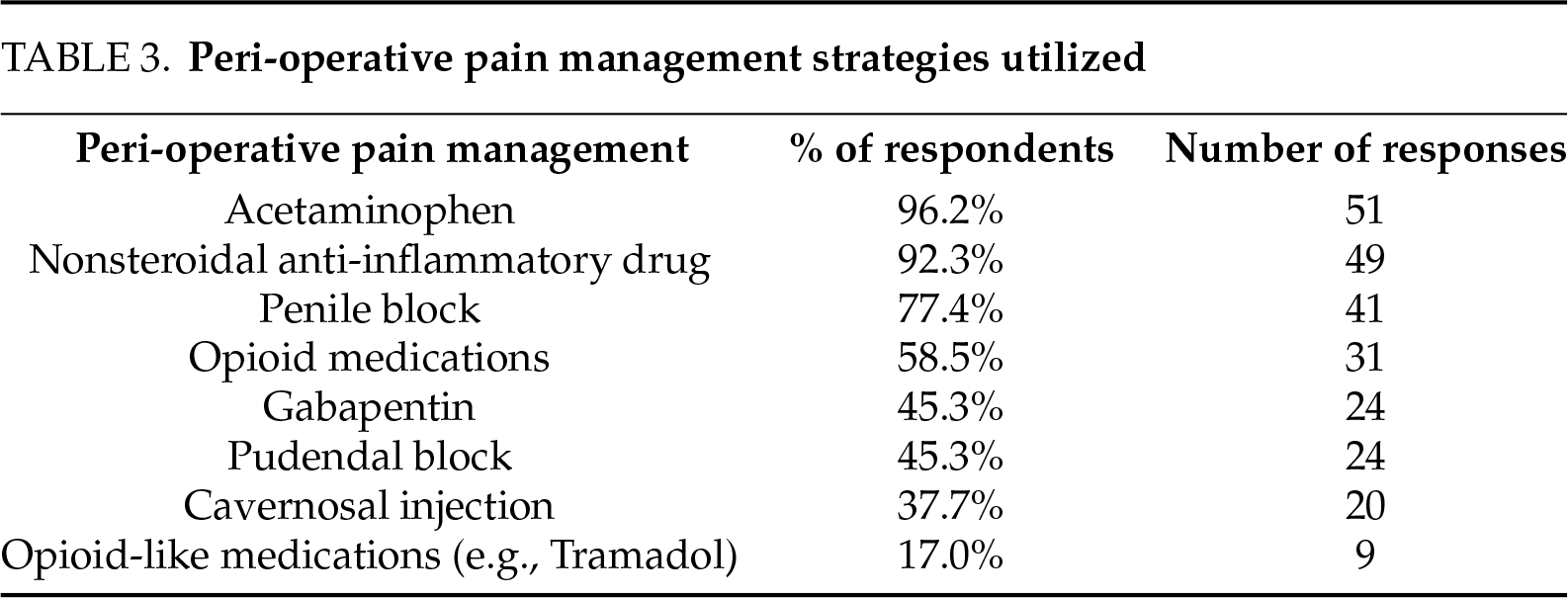

There was no association between the use of ORP/OFP and geographical location, number of years in practice, yearly case volume, surgical approach, or location of reservoir placement. Most respondents used a previously published ORP/OFP (47%, 25/53) and only 11% (6/53) of respondents consulted with their anesthesia/pain management departments. Of the non-opioid medications and techniques used, acetaminophen was the most common (96%, 51/53) followed by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) medications (92%, 49/53) and dorsal penile block (77%, 41/53) (Table 3).

Of the respondents who utilized ORP/OFP, 19% (9/47) stated that they had experienced an increase in patient calls, and 8.5% (4/47) had seen an increase in prescription refill requests. Despite the increased post-operative contact, none of the respondents reported decreased satisfaction. Most respondents utilizing ORP/OFP were extremely satisfied (70%, 33/47), while none of the respondents were either somewhat or extremely dissatisfied. There was no difference in provider satisfaction rates when comparing OFP and ORP.

Prescription opioids place patients at risk of developing addiction and may cause a significant burden on the healthcare system.3,4,6 As many urologic procedures are associated with prescription opioids,9 there has been a call to action amongst the urology community to limit the amount of opioids prescribed following surgery.8 Despite the low utilization of exclusively OFP among respondents (9.5%, 5/53), the results from our study are encouraging and show that over 90% of survey respondents have made changes to their practice to help limit the number of opioid medications prescribed following penile prosthesis surgery. This is important as there is a dose-dependent relationship between postoperative narcotic use and adverse events.14

There have been several ORPs published with encouraging results.12,13,15–17 The initial study by Tong et al. analyzed 57 patients who underwent penile prosthesis surgery and compared multi-modal analgesia (MMA) to narcotics for pain control.13 For MMA, the authors used a combination of meloxicam, acetaminophen, gabapentin, and intra-operative local anesthetic injection. When compared with the narcotics group, the MMA group required fewer narcotics upon discharge, fewer refills, and had lower pain scores. In a follow-up multi-institutional study by Lucas et al. this cohort was expanded to 203 patients with similar results that demonstrated the superiority of MMA over narcotics for postoperative pain control.15 Our study showed that half of the respondents followed one of these previously published protocols. Accordingly, most ORP/OFP protocols included NSAIDs (95.1%) and Acetaminophen (87.8%). Gabapentin, however, was not as commonly used (46.3%). The benefits of post-operative gabapentin may become more apparent as more surgeons start to routinely prescribe this in their practice. In a recent randomized controlled trial, Punjani et al. reported that the use of perioperative gabapentin resulted in decreased pain scores when compared with a placebo for patients undergoing scrotal surgery.18

In addition to NSAIDs, acetaminophen, and gabapentin, local anesthetic intra-operative blocks are an essential part of reducing opioid requirements following penile prosthesis surgery. Preemptive local analgesia has been well-studied in other specialties and has been shown to decrease opioid use in the postoperative period.19 In a randomized, placebo-controlled trial studying the efficacy and safety of dorsal penile blocks, Raynor et al. found that patients in the nerve block group had less pain in the immediate post-op period, although narcotic requirements did not decrease when compared with placebo.20 In comparison, pudendal nerve block at the time of prosthesis placement has been shown to reduce opioid use.21,22 Sayyid et al. studied 110 patients undergoing penile prosthesis placement in which 35% underwent intraoperative pudendal nerve block.22 The investigators found that intra-operative opioid requirements were decreased in the pudendal nerve block group (16.3 vs. 25.8 morphine milliequivalents, p = 0.037). A more recent study by Zhu et al. also evaluated the efficacy of pudendal nerve block at the time of penile prosthesis surgery.21 In total, 449 patients underwent penile prosthesis placement of which 83.1% (373/449) of patients underwent pudendal nerve block. While the intra-operative and PACU narcotic requirements were the same, patients from the pudendal nerve block group were less likely to call in for post-operative narcotics (10.2% vs. 19.7%, p = 0.016) and had decreased median time spent in PACU (149 min vs. 235 min, p < 0.001). Despite these results, our study showed that 80.5% of respondents use dorsal penile block but only 43.9% use pudendal nerve block. The pudendal nerve block is not a novel concept and was first used for placement of PP under local anesthesia in the 1980s–1990s.23–25 The delay in widespread adoption of pudendal block may indicate the lag time from recent publications as the larger studies investigating pudendal nerve block for penile prosthesis came out in 2023 and this study completed data collection in 2022.21,22

There is a theoretical concern that removing narcotics would cause a decrease in patient satisfaction following prosthetic surgery due to inadequate pain control. It has been shown that OFP utilizing multi-modal analgesia results in a decreased number of narcotic refills following penile prosthesis surgery.13,15 A recent study by Myrga et al. evaluated the burden on clinic staff after initiating OFP following artificial urinary sphincter (AUS) placement.26 The authors found that OFP did not increase office phone calls, emergency room visits, or unplanned office visits. For our study, OFP utilization resulted in a 22.2% (2/9) increase in calls to the clinic compared with a 7.9% increase (3/38) in clinic calls for those using ORP. Despite this increase in clinic burden, 0% of respondents reported a decrease in satisfaction. Our results support that ORP/OFP does not compromise the overall experience with penile prosthesis surgery and spares patients from the risks associated with opioid use.

Our study has several limitations. First, as this is a survey study, there is inherent recall and response bias among respondents. In addition, we were unable to calculate the response rate as the survey link was shared on X and was also mass-distributed by SMSNA and SUPS societies. While we did estimate an overall low response rate, there was representation from all geographic sections of the AUA. Second, our survey does not provide granular information on the different medication combinations used by respondents (including the type of local anesthesia used for penile/pudendal blocks) and how these impacted patient satisfaction outcomes. Specifically, our survey did not include information on the number of narcotics prescribed in ORP. Lastly, our survey did not elaborate on the various types of opioid medications used by respondents as well as the strength prescribed.

Future directions should emphasize providing educational opioid resources and training for prescribing providers. In a study by Kelley et al. 51.6% of Urology, residents receive no formal education on opioid prescribing practices during residency, and only 42.1% assess for opioid abuse before prescribing.27 However, the authors did find that urology residents who received formal opioid training prescribed less narcotics on average for common urologic procedures. While these results are encouraging, there is certainly room for improvement.

Our study demonstrates that opioid-reduced regimens are widely adopted among the prosthetic urologic community. While there is still room for improvement in the utilization of completely opioid-free protocols, it is important to highlight efforts that minimize post-operative narcotic exposure.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank the members of the Sexual Medicine Society of North America (SMSNA) and Society of Urologic Prosthetic Surgeons (SUPS) for their time and efforts dedicated to completing surveys.

Funding Statement

The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Nicolas Martin Ortiz, Adam Seth Baumgarten, Wendy Michelle Novicoff; data collection: Alexander Jordan Henry, Wendy Michelle Novicoff; analysis and interpretation of results: Nicolas Martin Ortiz, Wendy Michelle Novicoff, Adam Seth Baumgarten, Luke Patrick O’Connor, Marwan Ali, Alexander Jordan Henry; draft manuscript preparation: Luke Patrick O’Connor, Nicolas Martin Ortiz. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Nicolas Martin Ortiz, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval

The study protocol was approved as exempt by the institutional review board on 8/9/2021. This study did not involve any animal or human subjects.

Informed Consent

Questionnaire completion constitutes consent for anonymous data aggregation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Hedegaard H, Miniño AM, Warner M. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999–2018, in NCHS data brief, C. Hyattsville, MD, USA: US Department of Health and Human Services, National Center for Health Statistics; 2020. [Google Scholar]

2. Luo F, Li M, Florence C. State-level economic costs of opioid use disorder and fatal opioid overdose—United States, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021;70(15):541–546. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

3. Sun EC, Darnell BD, Baker LC, Mackey S. Incidence of and risk factors for chronic opioid use among opioid-naive patients in the postoperative period. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176(9):1286–1293. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

4. Schoenfeld AJ, Jiang W, Chaudary MA et al. Sustained prescription opioid use among previously opioid-naive patients insured through TRICARE (2006–2014). JAMA Surg 2017;152(12):1175–1176. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

5. Volkow ND, Jones EB, Einstein EB, Wargo EM. Prevention and treatment of opioid misuse and addiction: a review. JAMA Psychiatry 2019;76(2):208–216. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

6. Hansen RN, Oster G, Edelsburg J et al. Economic costs of nonmedical use of prescription opioids. Clin J Pain 2011;27(3):194–202. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

7. Bates C, Laciak R, Southwick A, Bishoff J. Overprescription of postoperative narcotics: a look at postoperative pain medication delivery, consumption and disposal in urological practice. J Urol 2011;185(2):551–555. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

8. Kiechle JE, Gonzalez CM. The opioid crisis and urology. Urology 2018;112:27–28. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

9. Ziegelmann MJ, Joseph JP, Glasgow AE et al. Wide variation in opioid prescribing after urological surgery in tertiary care centers. Mayo Clin Proc 2019;94(2):262–274. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

10. Ehlers ME, Mohan CS, Akerman JP et al. Factors impacting postoperative opioid use among patients undergoing implantation of inflatable penile prosthesis. J Sex Med 2021;18(11):1915–1920. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

11. Prebay ZJ, Foss H, Ebbott D et al. Oxycodone prescription after inflatable penile prosthesis has risks of persistent use: a TriNetX analysis. Int J Impot Res 2023;36(8):838–841. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

12. Ellis JL, Sudhakar A, Simhan J. Enhanced recovery strategies after penile implantation: a narrative review. Transl Androl Urol 2021;10(6):2648–2657. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

13. Tong CMC, Lucas J, Shah A et al. Novel multi-modal analgesia protocol significantly decreases opioid requirements in inflatable penile prosthesis patients. J Sex Med 2018;15(8):1187–1194. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

14. Chung BC, Bouz GJ, Mayfield CK et al. Dose-dependent early postoperative opioid use is associated with periprosthetic join infection and other complications in primary TJA. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2021;103(16):1531–1542. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

15. Lucas J, Gross M, Yafi F et al. A multi-institutional assessment of multimodal analgesia in penile implant recipients demonstrates dramatic reduction in pain scores and narcotic usage. J Sex Med 2020;17(3):518–525. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

16. Ellis JL, Pryor JJ, Mendez M et al. Pain management strategies in contemporary penile implant recipients. Curr Urol Rep 2021;22(3):17. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

17. Ellis JL, Higgins AM, Simhan J. Pain management strategies in penile implantation. Asian J Androl 2020;22(1):34–38. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

18. Punjani N, Marinaro JA, Kang C et al. Gabapentin for postoperative pain control and opioid reduction in scrotal surgery: a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Urol 2024;211(5):658–666. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

19. Taumberger N, Schütz A, Jeitler K et al. Preemptive local analgesia at vaginal hysterectomy: a systematic review. Int Urogyncol J 2022;33(9):2357–2366. [Google Scholar]

20. Raynor MC, Smith A, Vyas SN et al. Dorsal penile nerve block prior to inflatable penile prosthesis placement: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Sex Med 2012;9(11):2975–2979. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

21. Zhu M, Labagnara K, Loloi J et al. Pudendal nerve block decreases narcotic requirements and time spent in post-anesthesia care units in patients undergoing primary inflatable penile prosthesis implantation. Int J Impot Res 2024;37(1):55–60. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

22. Sayyid RK, Taylor NS, Owens-Walton J et al. Pudendal nerve block prior to inflatable penile prosthesis implantation: decreased intra-operative narcotic requirements. Int J Impot Res 2023;35(4):1–5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

23. Kaufman JJ. Penile prosthetic surgery under local anesthesia. J Urol 1982;128(6):1190–1191. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

24. Dos Reis JM, Glina S, Da Silva MF, Furlan V. Penile prosthesis surgery with the patient under local regional anesthesia. J Urol 1993;150(4):1179–1181. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

25. Das A, Soroush M, Maurer P, Hirsch I. Multicomponent penile prosthesis implantation under regional anesthesia. Tech Urol 1999;5(2):92–94. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

26. Myrga J, Klein R, Vasan R et al. No-opioid discharge following artificial urinary sphincter placement does not significantly increase health care system burden. Urol Pract 2024;11(2):333–338. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

27. Kelley JJ, Hill S, Deem S, Hale NE. Post-operative opioid prescribing practices and trends among urology residents in the united states. Cureus 2020;12(12):e12014. doi:10.7759/cureus.12014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools