Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Green is the new gold: a systematic review of the environmental impact of urological procedures, telehealth, and conferences

1 Department of Urology, Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, NY 10461, USA

2 Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY 10461, USA

* Corresponding Author: Kara L. Watts. Email:

Canadian Journal of Urology 2025, 32(6), 551-560. https://doi.org/10.32604/cju.2025.065988

Received 27 March 2025; Accepted 08 August 2025; Issue published 30 December 2025

Abstract

Background: The healthcare industry contributes nearly 5% of worldwide carbon emissions. In an effort to mitigate this impact, urology practices can take steps to reduce their carbon footprints. We conducted a systematic review which aimed to summarise the current literature on the environmental impact of urologic-related care. Methods: A systematic literature review evaluating the impact of urologic procedures, telehealth and conferences/interviews was conducted on PubMed and Cochrane databases using a Boolean search strategy and the following search terms: urology, planetary health, environmental impact, carbon emissions, carbon footprint, and waste. Full-text articles published in English were included and reviewed by two independent reviewers. The studies were grouped into three categories: surgical/procedural, telehealth, and conference/interview travel. Results: The initial search yielded 318 studies, of which 62 full-text manuscripts were reviewed. Of these, 22 studies met criteria for our systematic review: 13 surgical/procedural, 5 telehealth, 4 conference/interview travel. Most surgical/procedural studies compared the carbon footprint of flexible cystoscopy vs. disposable cystoscopy and found that disposable cystoscopy had a favourable environmental impact. The telehealth and conference/interview articles concluded that virtual settings significantly reduced environmental impact. Conclusions: An increasing body of literature has evaluated the impact of urologic care on planetary health and demonstrated opportunities to minimise our carbon footprint. Incorporating changes to common procedures and considering virtual formats for clinics, conferences, and interviews—even in part-confers environmental benefits. Efforts to adopt greener and more sustainable practices in urology are necessary to mitigate the threat to planetary health.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileClimate change is an increasing global threat. Many factors contribute to detrimental effects on the environment and accelerated rates of global warming. The environmental impact of various industries has fallen under scrutiny, with healthcare being no exception. It is estimated that at least 5% of worldwide greenhouse gas emissions are attributable to healthcare systems.1 Specifically, operating rooms represent a resource-intensive area that is characterised by high energy use and waste generation.2 Additional contributors to healthcare’s carbon footprint include patient and staff travel, electricity use, chemicals for sterilisation and reprocessing, waste management and the climate control of healthcare facilities.3

With the increasing concerns surrounding the environmental impact of healthcare, an emerging body of literature has emerged to examine the impact of urologic care on planetary health. Surgical care is often resource-intensive, with urologic care being no exception. As the need for urologic care grows with an ageing population, we must be conscientious of our contributions and make adjustments wherever we can. We present a comprehensive systematic review of the current literature, analysing the impact of various factors of urologic care on the environment. Namely, we reviewed literature pertaining to procedures, telehealth, conferences and interviews. Our aim is to provide a broad introduction to the topic, and the selected topics have not been represented in tandem in other systematic reviews.

A systematic review was performed to address the question: “What is the current state of evidence for the environmental impact of urologic-related care?” A literature search was performed in November 2024 on PubMed and Cochrane databases using the following initial search terms: ((“environmental impact”) OR (“planetary health”) OR (“carbon footprint”) OR (“climate change”) OR (“carbon emission”)) AND (“urology”).

A second, broader strategy was then used to ensure that the initial search was comprehensive: (“waste”) AND (“urology”).

The resulting literature from both searches was imported into the Covidence systematic review software for screening and extraction. One reviewer first screened studies by title and abstract (Shirley Ge). Afterwards, two reviewers conducted a full-text review of the remaining literature (Shirley Ge and John Hordines). Studies were included if they assessed urologic procedures, surgeries, conferences, or interviews, and carbon/environmental emissions and impact. Studies were excluded if they were not published in the English language, did not have full text available, or were not relevant to the theme of this review. Finally, the findings of the included literature were summarised. The search was conducted on November 1st, 2024, without any publication date limits. The included studies were assessed for risk of bias and overall applicability utilising the Quality Assessment with Diverse Studies (QuADS) appraisal tool.4 One reviewer from the research team assessed the studies independently by applying the 13-category tool to each manuscript and ascribing a numeric value of 0–3 on a scale for each category. The overall score for each article was assessed, and each included article had an acceptable risk of bias. No articles were excluded during this process.

This study was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA 2020 checklist (Supplementary Material S1), with the accompanying PRISMA 2020 flow diagram in Figure S1.

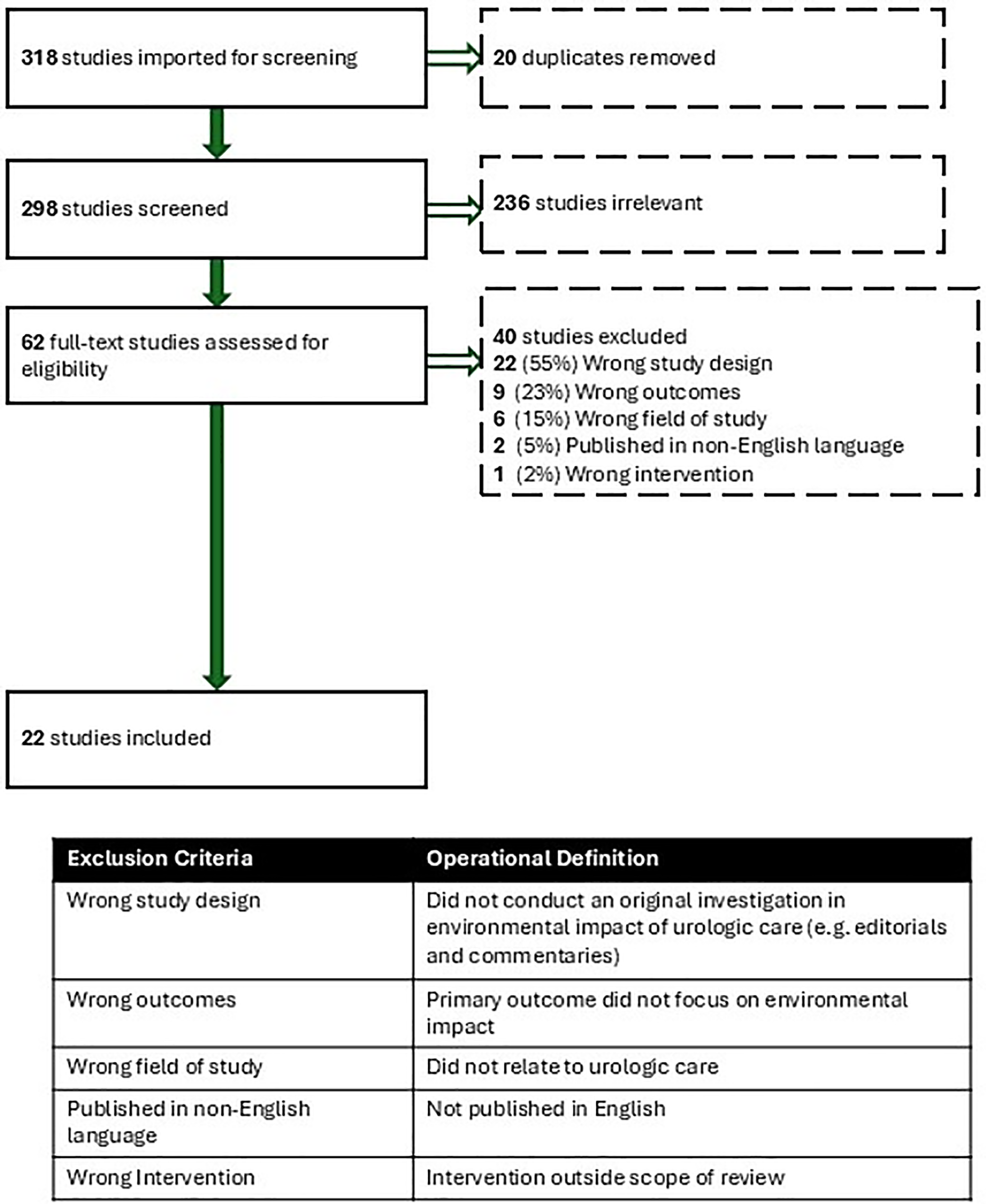

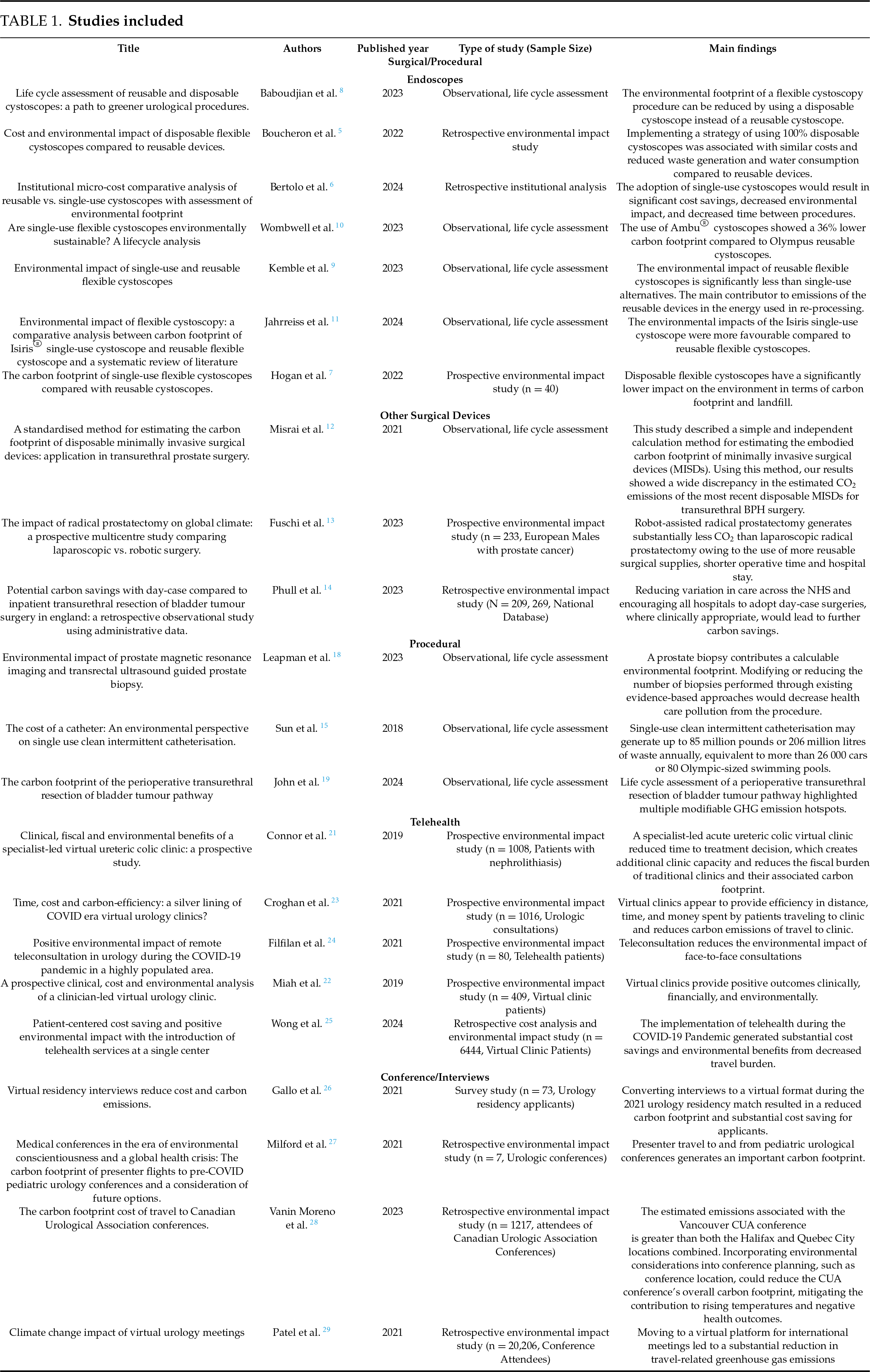

The search strategies yielded 318 publications (Figure 1). After 20 duplicates were removed, 298 studies remained for title and abstract screening. After final full-text review of 62 studies, 22 studies met eligibility criteria (Table 1).

FIGURE 1. Flowchart of this study

Studies were categorised as Surgical/Procedural (13, 59%), Telehealth (5, 23%), and Conference/Interviews (4, 18%).

All articles underwent quality assessment using the QuADS tool. Given the heterogeneity of our dataset and diversity of study types, a broad interpretation of the study question was used. All articles included were determined to have an acceptable risk of bias and were applicable to our study question.

Surgical/procedural investigations

This category was further subdivided into Endoscopes (7, 54%), Other Surgical Devices (3, 23%), and Procedural (3, 23%).

Endoscope articles consisted of two retrospective studies,5,6 one prospective study,7 and four life cycle assessments.8–11 The majority compared the carbon footprint of flexible vs. reusable cystoscopes and all but one found that disposable cystoscopy had a lower environmental impact (Table 1).5,6,8,10,11 While disposable cystoscopes generate more solid waste, the carbon footprint for reusable scopes is ultimately greater after accounting for the production, sterilisation, and reprocessing of reusable scopes.8 Boucheron et al. even concluded that converting their practice to 100% disposable scopes would decrease their waste generation and water consumption while maintaining similar costs overall.5 The only study showing a favourable impact on reusable cystoscopes was a lifecycle analysis performed by Kemble et al. The re-processing technique was cited as the primary driver of carbon emissions, while acknowledging that variation in methods between institutions can drive these differences.9

Three studies evaluated other tools or processes related to urological procedures (Table 1). Misrai et al. developed a standardised method for estimating the carbon footprint of disposable minimally invasive surgical devices (MISDs). In their method, each MISD was dismantled into its requisite components, and each piece was sorted into its respective raw material group and weighed. Researchers subsequently applied their method in estimating the carbon emissions of the seven latest MISDs for benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and found a wide range in estimated carbon emissions. Interestingly, the highest value was estimated for Rezūm, which generated carbon emissions equivalent to driving 15 km in an average petrol car. The lowest value was for a temporary implantable nitinol device (iTIND) at 76 g CO2. Thus, their study highlighted the need for increased awareness of surgical device carbon footprints and the urgency for implementing recycling programs and greener manufacturing processes.12

In the second study, Fuschi et al. compared the environmental impact of laparoscopic vs. robotic radical prostatectomy in a prospective multicenter study. Robotic surgery ultimately generated less CO2 than laparoscopy (47 kg vs. 60 kg) because robotic surgery used more reusable instruments and required shorter operative times and hospital stays. The authors concluded that further innovation should focus on improving hospital infrastructure to increase the adoption of robotic surgery over straight laparoscopic surgery.13

Lastly, the third study by Phull et al. compared the carbon footprint between same-day admission vs. inpatient transurethral resection of bladder tumour. They conducted a retrospective analysis of administrative data collected by the National Health Service (NHS) from 2013 to 2022. They found that compared to the years 2013–2014, the increase in ambulatory cases in 2021–2022 had a cumulative estimated saving of 2.9 million kg CO2 equivalents, which approximately equals the annual electrical power consumed by 2716 UK homes. Their results demonstrate the significant potential carbon savings of hospitals adopting more same-day/ambulatory surgeries.14

The three procedural-focused studies conducted life-cycle assessments on clean intermittent catheterisation (CIC), prostate biopsies, and a perioperative pathway for transurethral resection of bladder tumours (Table 1). For CIC, Sun et al. estimated the total amount of waste generated from single-use CIC in the United States at approximately 85 million pounds of waste annually, equivalent to 80 Olympic-sized swimming pools.15 Single-use CIC has not been demonstrated to reduce rates of urinary tract infections, and while they may provide some limited clinical benefit, the substantial amount of waste produced calls for a re-examination of their utility.15–17

For prostate biopsies, the only available study thus far by Leapman et al. estimated that transrectal ultrasound-guided prostate biopsy, including prostate magnetic imaging (MRI) and pathology analysis, emits 80.7 kg CO2 equivalents when both systematic and MRI-US fusion biopsies were taken. Reducing the number of unnecessary biopsies would, in turn, have a calculable environmental benefit. Specifically, avoiding 100,000 unnecessary biopsies would save 8.1 million kg CO2, equivalent to 4.1 million litres of gasoline consumed. The authors also estimated that using prostate MRI to triage biopsies and guide targeted biopsy cores could substantially reduce carbon emissions of up to 1.4 million kg CO2 per 100,000 patients by both reducing the number of biopsies done and the number of cores sent for pathologic processing.18

John et al. performed a cradle-to-grave life-cycle assessment of transurethral resection of bladder tumours at a single center in the United Kingdom. They found that median greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions per case were 131.8 kg of carbon dioxide equivalent.19 This is comparable to a car burning approximately 15 gallons of gasoline.20 The four major categories of energy use are determined, namely, surgical equipment, travel, gas and electricity, and anesthesia considerations.19 Single-use items for all processes were found to be the largest contributing factor to their carbon footprint. Limiting travel for staff and patients, reducing the use of single-use items, and avoiding inpatient admission when medically feasible were all mitigation strategies proposed by the authors.19

Telehealth and conferences/interviews

The studies evaluating the impact of Telehealth and Conference/Interviews in Urology examined the carbon footprint of virtual clinics and virtual residency interviews and urological conferences, respectively (Table 1). Within telehealth, all articles were prospective environmental impact studies, and each of them showed, unsurprisingly, that virtual clinics provide substantial environmental benefits from the reduced travel to the clinic.21–25 Some even found improved clinical outcomes and financial advantages to both patients and providers.21–23 For example, a specialist-led acute ureteric colic virtual clinic reduced time from initial presentation to treatment decision to a median of two days, consequently creating clinic capacity and minimising the carbon footprint of an in-person clinic.21 Miah et al. also reported a high patient satisfaction rate of 90.1% and predicted annual savings of £56,232 for the National Health Service with virtual clinics.22 Wong et al. found an average cost savings of $152.78 per encounter, and 153.36 metric tons of CO2 were avoided for 6444 virtual encounters.25

Similarly, four studies evaluating virtual platforms for Urologic conferences and residency interviews demonstrated, again not unsurprisingly, that virtual residency interviews and conferences reduce the carbon footprint and travel costs for participants. With regard to virtual residency interviews, the authors calculated that for each applicant, an average of 6.26 metric tons of CO2 and $2198 were saved with the all-virtual interview format during the 2021 interview cycle.26 Most applicants favored the virtual mode, with 72% reporting that they would very likely or somewhat likely recommend it for the future.26 Articles that evaluated the carbon footprint of urological conferences showed that conference travel is associated with significant carbon emissions.27–29 Like the conclusions related to virtual clinics, removing the need for travel for residency interviews results in considerable savings for applicants in addition to substantial improvements in the overall environmental impact.

There is increasing literature evaluating the impact of urologic-related care on carbon emissions and waste. These studies are challenging to conduct, particularly given the multiple domains where carbon emissions can be measured for surgical and procedural devices—namely, production, processing, and waste generation. Despite this, the growing literature and attention toward adopting sustainable practices and guidelines is paramount.30

Of the studies reviewed, the literature supports a favourable carbon footprint amongst, single-use flexible cystoscopes in comparison to reusable cystoscopes. One may presume that the waste generation of the single-use, largely plastic endoscopes generates substantially more environmental waste. However, the waste and emissions from the re-sterilisation of the reusable scopes exceed those of the single-use scope when considering energy utilisation, water consumption, and chemical cost/toxicities in several studies.5,7,8 One challenge in this space is the variability amongst institutions in their re-processing methodologies, and variability in reporting. For example, Kemble et al. were the only study that found reusable cystoscopes to produce less CO2 emissions than single-use scopes, but their institution used an endoscope-specific reprocessing system and cited a 10-fold decrease in energy requirements per processing event compared to similar studies.9 Other studies, such as that by Baboudjian et al., emphasised not only carbon emissions but also other factors such as environmental and occupational toxicity of the reagents used.8 Both studies acknowledged that the generalizability of their results is limited, given that they looked at specific scope models and individual institution re-processing methods. These are often bound by contractual obligations for the purchase of reagents and equipment, and take into account other needs within a given hospital system. Furthermore, single-use cystoscopes have no significant clinical disadvantages compared to reusable ones; thus, wider adoption of single-use cystoscopes should be considered, and/or utilisation of less toxic, greener chemicals for re-sterilisation of reusable scopes. The onus will be on both the industry to develop financially viable, greener technologies for this purpose and institutions to prioritize minimising their carbon footprint.

Telehealth and virtual conferences, and interviews can provide significant savings in both carbon emissions and financial costs to both patients and clinicians by eliminating the need for travel.22–24,26,28 The ability to provide high-quality care to individuals without the added burden of travel makes telehealth an attractive and sustainable option. However, the benefits of in-person evaluation for certain conditions merit appropriate triage and development of protocols to support efficacious and thoughtful pathways within telehealth. Similar considerations must be made for virtual residency interviews. Although many urology residency applicants preferred the virtual format in recent years during the period of the COVID-19 pandemic,26,31 programs in urology and other specialities are now returning to in-person interviews. In-person interviews offer benefits for applicants to tour training sites and potentially aid programs, and applicants in obtaining a better sense of an their fit with a program. Nonetheless, the steep individual financial burden and environmental impact of in-person interviews cannot be ignored. Further research on the scope of telehealth and the urology match process is needed to optimise the utility of a virtual format for all stakeholders.

Virtual conferences clearly demonstrate a favourable emissions profile compared to in-person conferences, although this is at the expense of limiting the benefits of in-person conferences, namely, networking and learning about new industry or products. Given the expense and tremendous emissions related to conference travel, environmental considerations should be made, such as reducing single-use items, offering a remote video streaming option, and choosing a central location for participants.27,28 In addition, consideration for hosting conferences in venues that partner with organisations with an emphasis on sustainability should be prioritised.

Potential other opportunities to minimise carbon emissions include performing robotic surgery over laparoscopic surgery, scheduling more same-day transurethral bladder tumour resections over inpatient surgeries, limiting the use of single-use items during transurethral surgery, avoiding single-use CICs, and reducing unnecessary prostate biopsies.13–15,18,19 These suggestions arise from single studies, so further research in different hospital settings would help to better understand the parameters around these recommendations.

It is notable that none of the included studies were evaluations of interventions, departmental policies, or quality improvement initiatives. Further research should not only continue evaluating the carbon footprint of urologic care, but also prospectively implement previously shown sustainable options. However, scaling up sustainable practices to reach effective carbon efficiency will require a cultural shift in the healthcare industry to fully incorporate climate-conscious principles.32 This shift would involve integrating planetary health into clinical guidelines, stakeholder buy-in, and close collaboration with leadership and administrators.30,32–34

It is worth noting that, overall, there have been few studies evaluating the impact of urologic care on planetary health. Our review only yielded 22 studies. All included studies were published in the last five years, which could be a reflection of the recent increased urgency of climate change. The paucity of studies may also indicate that more standardised methods to measure the carbon footprint of surgical devices are needed, and that manufacturer Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) data should be more transparent.12 Indeed, assessing the environmental impact of urologic procedures and devices is complex, from analysis of production, processing, and waste management, each of which contributes in its own domain. Incorporating environmental impact considerations when designing new urologic procedures and devices should also be made a common practice. This should serve as a call to action to critically evaluate our current practices and consider a focus on incorporating sustainability, waste minimisation, and partnering with industry focused on carbon neutrality.30

Our study is subject to limitations that are inherent to systematic reviews. Articles published in non-English languages were excluded, so some environmental evaluations, particularly those published in countries that are not predominantly English-speaking, may have been missed. Moreover, there was a possible risk of reviewer bias when screening and full-text reviewing the literature. Having two reviewers and pre-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria aimed to avoid individual interpretation bias.

An increasing number of articles on the impact of urologic care and planetary health demonstrate opportunities to minimise the carbon footprint of common procedures, and the environmental benefit of a virtual format for clinics, conferences, and interviews. Further research should explore the environmental impact of urologic care and aim to implement more sustainable practices and clinical guidelines. Efforts to adopt greener and more sustainable practices in urology are necessary to mitigate growing threats to planetary health.

Acknowledgement

Not applicable.

Funding Statement

The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contribution

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Shirely Ge, Kara L. Watts and John Hordines; methodology, Kara L. Watts, Shirely Ge and John Hordines; software, Shirely Ge; validation, Shirely Ge and John Hordines; formal analysis, John Hordines, Shirely Ge and Kara L. Watts; writing—original draft preparation, Shirely Ge and John Hordines; writing—review and editing, Kara L. Watts, Alex C. Small, Dima Raskolnikov, John Hordines and Shirely Ge; visualization, Shirely Ge, John Hordines and Kara L. Watts; supervision, Kara L. Watts, Alex C. Small and Dima Raskolnikov; project administration, Kara L. Watts. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Materials.

Ethics Approval

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials

The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/cju.2025.065988/s1.

References

1. Rodríguez-Jiménez L, Romero-Martín M, Spruell T, Steley Z, Gómez-Salgado J. The carbon footprint of healthcare settings: a systematic review. J Adv Nurs 2023;79(8):2830–2844. doi:10.1111/jan.15671. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. MacNeill AJ, Lillywhite R, Brown CJ. The impact of surgery on global climate: a carbon footprinting study of operating theatres in three health systems. Lancet Planet Health 2017;1(9):e381–e388. doi:10.1016/S2542-5196(17)30162-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. How can we reduce Urology’s carbon footprint? BJU Int 2022;129(1):7–8. doi:10.1111/bju.15668. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Harrison R, Jones B, Gardener P, Lawton R. Quality assessment with diverse studies (QuADSan appraisal tool for methodological and reporting quality in systematic reviews of mixed- or multi-method studies. BMC Health Serv Res 2021;21(1):144. doi:10.1186/s12913-021-06122-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Boucheron T, Lechevallier E, Gondran-Tellier B et al. Cost and environmental impact of disposable flexible cystoscopes compared to reusable devices. J Endourol 2022;36(10):1317–1321. doi:10.1089/end.2022.0201. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Bertolo R, Gilioli V, Veccia A et al. Institutional micro-cost comparative analysis of reusable vs single-use cystoscopes with assessment of environmental footprint. Urology 2024;188:70–76. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2024.03.023. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Hogan D, Rauf H, Kinnear N, Hennessey DB. The carbon footprint of single-use flexible cystoscopes compared with reusable cystoscopes. J Endourol 2022;36(11):1460–1464. doi:10.1089/end.2021.0891. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Baboudjian M, Pradere B, Martin N et al. Life cycle assessment of reusable and disposable cystoscopes: a path to greener urological procedures. Eur Urol Focus 2023;9(4):681–687. doi:10.1016/j.euf.2022.12.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Kemble JP, Winoker JS, Patel SH et al. Environmental impact of single-use and reusable flexible cystoscopes. BJU Int 2023;131(5):617–622. doi:10.1111/bju.15949. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Wombwell A, Holmes A, Grills R. Are single-use flexible cystoscopes environmentally sustainable? A lifecycle analysis. J Clin Urol 2024;17(3):224–227. doi:10.1177/20514158231180661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Jahrreiss V, Sarrot P, Davis NF, Somani B. Environmental impact of flexible cystoscopy: a comparative analysis between carbon footprint of Isiris® single-use cystoscope and reusable flexible cystoscope and a systematic review of literature. J Endourol 2024;38(4):386–394. doi:10.1089/end.2023.0274. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Misrai V, Rijo E, Cottenceau JB et al. A standardised method for estimating the carbon footprint of disposable minimally invasive surgical devices. Ann Surg Open 2021;2(3):e094. doi:10.1097/AS9.0000000000000094. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Fuschi A, Pastore AL, Al Salhi Y et al. The impact of radical prostatectomy on global climate: a prospective multicentre study comparing laparoscopic versus robotic surgery. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 2024;27(2):272–278. doi:10.1038/s41391-023-00672-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Phull M, Begum H, John JB et al. Potential carbon savings with day-case compared to inpatient transurethral resection of bladder tumour surgery in England: a retrospective observational study using administrative data. Eur Urol Open Sci 2023;52:44–50. doi:10.1016/j.euros.2023.03.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Sun AJ, Comiter CV, Elliott CS. The cost of a catheter: An environmental perspective on single use clean intermittent catheterisation. Neurourol Urodyn 2018;37(7):2204–2208. doi:10.1002/nau.23562. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Christison K, Walter M, Wyndaele JJJM et al. Intermittent catheterisation: the devil is in the details. J Neurotrauma 2018;35(7):985–989. doi:10.1089/neu.2017.5413. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Håkansson MÅ. Reuse versus single-use catheters for intermittent catheterisation: what is safe and preferred? Review of current status. Spinal Cord 2014;52(7):511–516. doi:10.1038/sc.2014.79. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Leapman MS, Thiel CL, Gordon IO et al. Environmental impact of prostate magnetic resonance imaging and transrectal ultrasound guided prostate biopsy. Eur Urol 2023;83(5):463–471. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2022.12.008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. John JB, Collins M, Eames S et al. The carbon footprint of the perioperative transurethral resection of bladder tumour pathway. BJU Int Pub Online 2024;135(1):78–87. doi:10.1111/bju.16477. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. EPA, US and of Transportation, Office and Quality, Air and Division, Climate. Greenhouse gas emissions from a typical passenger vehicle: questions and answers—fact sheet (EPA-420-F-23-014, June 2023). Ann Arbor, MI, USA: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency; 2023. [Google Scholar]

21. Connor MJ, Miah S, Edison MA et al. Clinical, fiscal and environmental benefits of a specialist-led virtual ureteric colic clinic: a prospective study. BJU Int 2019;124(6):1034–1039. doi:10.1111/bju.14847. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Miah S, Dunford C, Edison M et al. A prospective clinical, cost and environmental analysis of a clinician-led virtual urology clinic. Ann Royal College Surg England 2019;101(1):30–34. doi:10.1308/rcsann.2018.0151. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Croghan SM, Rohan P, Considine S et al. Time, cost and carbon-efficiency: a silver lining of COVID era virtual urology clinics? Ann Royal College Surg England 2021;103(8):599–603. doi:10.1308/rcsann.2021.0097. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Filfilan A, Anract J, Chartier-Kastler E et al. Positive environmental impact of remote teleconsultation in urology during the COVID-19 pandemic in a highly populated area. Progrès En Urologie 2021;31(16):1133–1138. doi:10.1016/j.purol.2021.08.036. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Wong V, Cohen J, Ingram A et al. Patient-centered cost saving and positive environmental impact with the introduction of telehealth services at a single center. Urol Pract 2024;12:44–50. doi:10.1097/UPJ.0000000000000723. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Gallo K, Becker R, Borin J, Loeb S, Patel S. Virtual residency interviews reduce cost and carbon emissions. J Urol 2021;206(6):1353–1355. doi:10.1097/JU.0000000000002197. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Milford K, Rickard M, Chua M, Tomczyk K, Gatley-Dewing A, Lorenzo AJ. Medical conferences in the era of environmental conscientiousness and a global health crisis: the carbon footprint of presenter flights to pre-COVID pediatric urology conferences and a consideration of future options. J Pediatr Surg 2021;56(8):1312–1316. doi:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2020.07.013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Vanin Moreno NM, Paco C, Touma N. The carbon footprint cost of travel to Canadian Urological Association conferences. Can Urol Assoc J 2023;17(6):E172–E175. doi:10.5489/cuaj.8132. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Patel SH, Gallo K, Becker R, Borin J, Loeb S. Climate change impact of virtual urology meetings. Eur Urol 2021;80(1):121–122. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2021.04.033. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Herrmann A, van Veen FEE, Blok BFM, Watts KL. A green prescription: integrating environmental sustainability in urology guidelines. Eur Urol Focus 2023;9(6):897–899. doi:10.1016/j.euf.2023.11.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Carpinito GP, Badia RR, Khouri RK et al. Preference signaling and virtual interviews: the new urology residency match. Urology 2023;171:35–40. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2022.09.028. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Herrmann A, Lenzer B, Müller BS et al. Integrating planetary health into clinical guidelines to sustainably transform health care. Lancet Planet Health 2022;6(3):e184–e185. doi:10.1016/S2542-5196(22)00041-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. McGain F, Naylor C. Environmental sustainability in hospitals—a systematic review and research agenda. J Health Serv Res Policy 2014;19(4):245–252. doi:10.1177/1355819614534836. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Smith A, Severn M. CADTH horizon scan CADTH horizon scan reducing the environmental impact of clinical care 2. Canadian J Health Technol 2023;3(4). [cited 2024 Oct 13]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK596637/. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools