Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Treatment patterns for genitourinary syndrome of menopause: a TriNetX analysis

Department of Urology, Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA 19107, USA

* Corresponding Author: Alana M. Murphy. Email:

Canadian Journal of Urology 2025, 32(6), 627-632. https://doi.org/10.32604/cju.2025.067575

Received 07 May 2025; Accepted 28 July 2025; Issue published 30 December 2025

Abstract

Background: Genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) is a highly prevalent, underdiagnosed condition that can significantly impair quality of life (QoL). This study evaluates real-world treatment trends for GSM to better understand current management practices and highlight ongoing gaps in care. The background is in a different font than the rest of the abstract. Methods: We queried the TriNetX database for patients with a diagnosis of postmenopausal atrophic vaginitis (ICD N95.2) and treatment information from 2004–2024. A combination of RxNorm and International Classification of Diseases-10 (ICD) codes was used to classify disease and treatment type, including topical estrogen (RxNorm 4083, 4099), Ospemifene (RxNorm 1370971), Prasterone (RxNorm 3143), and hormone replacement therapy (HRT, ICD Z79.890). Demographic information about the patients’ age and sex was collected. Results: Overall, there were 2,867,232 cases of GSM identified. 71.22% (n = 2,042,024) of the cohort did not receive any treatment. Of patients undergoing treatment, the majority underwent a single intervention (n = 740,922, 89.79%). Of single medical therapy cases, topical estrogen (n = 656,825; 88.64%) was most common, followed by HRT (n = 78,855; 10.64%), Prasterone (n = 3691; 0.50%), and lastly Ospemifene (n = 1551; 0.21%). Very few patients underwent multiple interventions (n = 31,339; 9.1%), the majority of which were prescribed topical estrogen with HRT (n = 70,392; 83.52%). Conclusions: Most women diagnosed with GSM did not receive treatment. Among those treated, topical estrogen was the predominant therapy. Newer therapies were underutilized, though it is unclear whether this is due to provider familiarity, patient preference, or access. Further research is warranted to elucidate the underlying reasons for undertreatment in this population.Keywords

Genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) has a reported prevalence of 50%–80% in postmenopausal women, yet it remains underdiagnosed and undertreated.1,2 GSM is combination of genital, sexual, and urinary symptoms arising from estrogen deficiency that poses profound consequences for a woman’s quality of life (QoL).1 The primary symptoms include vaginal dryness, burning, irritation, decreased lubrication, dyspareunia, postcoital bleeding, urinary urgency, frequency, nocturia, dysuria, incontinence, and recurrent urinary tract infections (UTIs).1 While most GSM patients may only liaison with primary care and gynecology, incontinence and recurrent UTIs commonly prompt presentation to urology clinics.3

Unlike many other concerns associated with hypoestrogenism, such as vasomotor symptoms, the genitourinary effects do not improve over time unless intervention is provided.1,2 There are treatments for GSM ranging from non-hormonal therapies like lubricants and moisturizers to the gold standard topical estrogen, to systemic therapies such as hormonal replacement therapy. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has also approved non-estrogen pharmacologics, like Prasterone, an intravaginal dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) insert, and oral Ospemifene, a selective estrogen receptor modulator, for GSM treatment. Prasterone has shown to improve sexual symptoms associated with GSM, including arousal, vaginal lubrication, and dyspareunia. It is locally metabolized in vaginal tissues to active androgens, which are then aromatized to form estrogens. Ospemifene is an oral therapy that alleviates dyspareunia by acting as an estrogen receptor agonist in the vaginal epithelium.1,2,4

In recent years, energy-based technologies, like vaginal carbon dioxide lasers and erbium:YAG (Er:YAG) lasers, have been used off-label to manage refractory cases of GSM. These devices deliver controlled thermal energy to the vaginal mucosa, aiming to induce collagen remodeling, neovascularization, and thickening of the epithelium, thereby restoring some premenopausal tissue characteristics and improving symptoms. However, the evidence on these therapies is mixed. One meta-analysis by Khamis et al. reported some subjective symptom improvement, while a systematic review by Zerzan et al. found little to no difference between CO2 laser and sham treatment in symptom severity, QoL, or vaginal health after 12 months.5,6 These modalities remain investigational, and further studies are needed to optimize care.

Patients remain highly frustrated and confused regarding the lack of access to education and treatment for their symptoms.7,8 Patients are often hesitant to discuss genitourinary conditions, and the manifestations and treatment options of GSM are poorly understood by lay people and many physicians. Given that GSM affects majority of postmenopausal women, regular screening should be conducted for all postmenopausal patients.9,10 Engagement in open discussion and shared decision-making can empower patients to better understand their own health and take action to improve QoL.

Given the sensitive nature and evolving definition of GSM, the quality of care being provided to patients appears unclear.11 Better understanding of current patterns in GSM treatment is paramount to addressing barriers and improving access for this patient population. In this study, we aimed to use the TriNetX global database to identify patterns in utilization of various treatment options for GSM.

Our study was exempt from the Institutional Review Board because it is a secondary analysis of a deidentified database.

The TriNetX database (https://live.trinetx.com) (accessed on 27 July 2025) was used to collect deidentified patient information from 2004–2024. The database comprises over 250 million de-identified patient records sourced from more than 120 healthcare organizations across 30 countries from North America, Europe, Latin America, and Asia, providing a diverse and representative sample of real-world clinical practice.12 The database enables analysis of large-scale treatment trends over time and provides population-level insights into clinical practice that are not possible with traditional literature reviews (e.g., PubMed or Scopus).

Our retrospective cohort analysis included all females (>51 years) who have been diagnosed with GSM (ICD N95.8) or menopause related genitourinary illnesses. Since GSM was formally introduced in 2014,13 it is a relatively new term and less frequently used to categorize genitourinary tract symptoms related to menopause. Therefore, we included other menopause related genitourinary track diagnoses, such as postmenopausal atrophic vaginitis (N95.2), dyspareunia (N94.1), recurrent urinary tract infections (Z87.440), urinary urgency/incontinence (R39.15, N39.41, N39.498), urinary frequency (R35.0), dysuria (R30.0), postcoital and contact bleeding (N93.0), pruritus vulvae (L29.2), and vaginal irritation (N89.8), to provide a robust all-encompassing analysis. Interventions for GSM included topical estrogen (RxNorm 4083, 4099), Ospemifene (RxNorm 1370971), Prasterone (RxNorm 3143), and hormone replacement therapy (HRT) (ICD Z79.890). Demographic information about the patient’s age and race was collected.

Descriptive statistics were used to report the number and percentage of patients receiving no intervention, a single therapy, or multiple therapies. Treatment distributions were calculated across different intervention types and combinations.

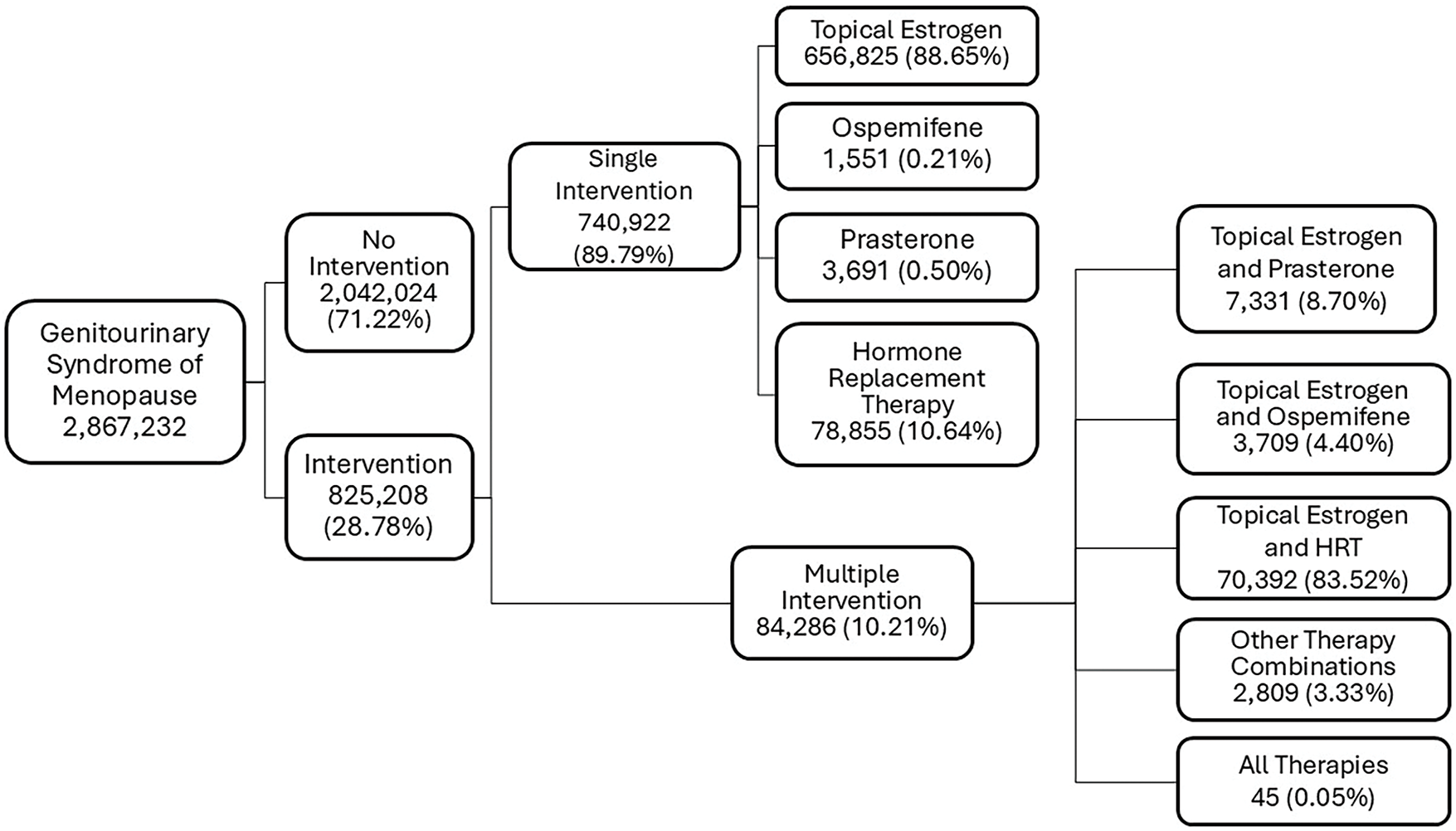

From 2004–2024, there were 2,867,232 patients diagnosed with GSM or a GSM related condition in our cohort. The mean age was 70 ± 12 years. Most of the patients (n = 2,042,024; 71.22%) did not undergo treatment despite being diagnosed with GSM or GSM related symptoms. Of the patients who underwent treatment, most were treated with a single intervention (n = 740,922, 89.79%). Topical estrogen was the most popular treatment (n = 656,825; 88.64%), followed by HRT (n = 78,855; 10.64%), Prasterone (n = 3691; 0.50%), and Ospemifene (n = 1551; 0.21%). All cohorts had similar demographics, and the mean age of patients was 70 ± 12 years, 72 ± 11 years, 65 ± 9 years, and 66 ± 7 years, respectively.

Few patients underwent multiple treatments (n = 84,286; 10.21%), among which the combination of HRT and topical estrogen was the most popular (n = 70,392; 83.52%). The mean age of patients within the group was 69 ± 10 years. Among the patients who underwent multiple interventions, 8.70% (n = 7331) used a combination of topical estrogen and Prasterone (mean age = 66 ± 9 years). A combination of all therapies, including topical estrogen, Ospemifene, Prasterone, and HRT, was the least popular intervention with only 45 patients (0.05%) undergoing the treatments (mean age = 66 ± 6 years) (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1. Treatment Pathways in Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause. Most women with GSM were untreated (n = 2,042,024; 71.22%). Among those treated, topical estrogen was most common (n = 656,825; 88.65%), followed by hormone replacement therapy (HRT) (n = 78,855; 10.64%) and combination therapy (n = 84,286; 10.21%)

The current study provides a snapshot of the current treatment distribution of GSM patients. Most patients were not treated for their symptoms (71.22%) despite being diagnosed with GSM or GSM-related conditions. Of the patients on treatment, most underwent a single medical therapy (89.79%). Very few patients had to step up their treatments to a combination of therapies (10.21%).

Interestingly, the mean age of diagnosed patients in our cohort was 70 ± 12 years, which is older than the expected onset of GSM, typically within a few years after menopause (late 50 s). Because TriNetX captures patients’ most recent age rather than the age at diagnosis, the reported mean age may overestimate the true age at symptom onset. Additionally, this likely reflects the chronic, progressive nature of GSM, where many women do not seek care until symptoms worsen. Younger postmenopausal women may be underrepresented in the database due to delayed diagnosis.

The low-estrogen state during peri- and post-menopausal periods manifest in various health problems, of which genitourinary symptoms are especially concerning as they are chronic and will worsen without treatment.14 Hence, treatment is necessary and observation alone is inadvisable. Yet, majority of women diagnosed with GSM go untreated. Untreated GSM can diminish a patient’s QoL by negatively affecting their confidence and intimacy with their partners.15

Topical estrogen is the gold standard treatment for women experiencing GSM without systemic manifestations of menopause.16 Local application of low dose estrogen has been shown to improve the vaginal microbiome and the gross vaginal mucosal appearance. It can also relieve GSM symptoms such as dysuria, stress urinary incontinence, recurrent UTIs, and urinary urgency and frequency.17 Despite its benefits, patients are often hesitant due to safety concerns about hormonally driven adverse effects. However, recent studies have found no associations between low-dose topical estrogen and increased risk of thromboembolism.18 Moreover, cases of endometrial pathologies were extremely rare.17 Additionally, vaginal estrogen has been found to be safe, with research demonstrating that it does not significantly elevate serum estrogen levels, even in postmenopausal women with a history of breast cancer.19 Considering vaginal estrogen is generally safe for most menopausal women and can significantly improve their QoL, it is imperative that physicians are proactive about discussing and educating their patients on vaginal estrogen.

Our data shows, among treated patients, HRT was most utilized after topical estrogen. HRT is usually recommended for women who are experiencing severe systemic systems, like vasomotor dysfunction, in addition to genitourinary symptoms. These women are either given estrogen alone or a combination of estrogen and a progestogen. While HRT is effective for systemic menopausal symptoms, it may not fully address all GSM symptoms, like hypoactive sexual desire.16

Prasterone and Ospemifene are treatment options for patients primarily experiencing dyspareunia and vaginal dryness associated with GSM. In randomized controlled trials, Prasterone significantly decreased the percentage of vaginal epithelial parabasal cells, increased the percentage of vaginal epithelial superficial cells, decreased vaginal pH, and improved the dyspareunia compared to a placebo after 12 weeks.20 Ospemifene is approved by the FDA for the treatment of dyspareunia, and several studies have also shown improvement in vaginal pH and dryness with daily use. These therapies may be an option for patients whose symptoms persist despite initial therapies 21,22; however, our data show these pharmacologic agents are rarely used.

Treatment for GSM may greatly improve a woman’s QoL; however, our analysis shows that most women do not undergo treatment for their symptoms. Given that there are about 29 million women over the age of 51 in the TriNetX database and the incidence of GSM in post-menopausal women is 70%, we expected around 20 million cases of GSM.23 It is likely that women are not seeking treatment for their symptoms because they may be hesitant to have these conversations, may not realize treatment options exist, or even that their symptoms are related to menopause.24 Hot flashes are a common and publicly discussed part of menopause, but very few know about recurrent UTIs, urinary incontinence, and dyspareunia. Many times, women also feel their symptoms are not significant enough to bring up with their doctors. Some women might also be embarrassed to openly discuss their symptoms with healthcare professionals due to the stigma that surrounds menopause. It is imperative that healthcare professionals proactively assess for the full spectrum of GSM symptoms rather than waiting for patients to report them. Even if not all components are present, clinicians should routinely inquire about genital, sexual, and urinary concerns. When possible, validated questionnaires such as the Vulvovaginal Symptoms Questionnaire, or the Menopause-Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire (MENQOL), should be used to facilitate comprehensive and sensitive screening.

A recent cross-sectional study of Turkish postmenopausal women found that only about half of those with symptoms had ever sought medical care.25 Similar findings were reported by the GENISSE study in Spain where there was a high prevalence of GSM with minimal efforts made to seek care.26 This mirrors our own findings, highlighting a global trend of under-recognition and under-treatment of GSM. The authors speculated this trend could be partially attributed to a lack of standardized diagnostic criteria for GSM.25 Given the syndrome’s overlap across genital, sexual, and urinary domains, there is a growing need for collaborative efforts between urologists and gynecologists to develop a unified diagnostic framework to reduce diagnostic ambiguity and improve care.

Additionally, patients have safety concerns about using estrogen containing products due to the presence of the black box warning that lists endometrial cancer, cardiovascular disease, breast cancer, and dementia as possible side effects.27 However, multiple large scale studies have shown the risks of cardiovascular disease and cancer are not elevated among postmenopausal women using vaginal estrogens.28,29 And when we discuss treating GSM, it is important to educate women on the risks and benefits of hormones so they can choose the best decision for themselves.

Our analysis is not without limitations. First, TriNetX is a large, deidentified database and the accuracy of its data depends on accurate data entry by the physician. This includes patient demographics, clinical characteristics, and ICD-10 or RxNorm codes. Due to the limitations of the database, we could not include patients who were prescribed pelvic floor exercises or over-the-counter treatments such as lubricants and moisturizers as there are no codes for these treatments. Additionally, the database does not capture medication timing at a granular level, so we could not determine whether multiple treatments were prescribed concurrently or sequentially. Lastly, it is not possible to ascertain the actual usage and duration of medical treatments. However, this project still provides a bird’s eye view of treatment patterns for GSM and is a great starting point in understanding and improving the current treatment patterns. It especially showcases how topical estrogen is a great tool for treating GSM but is being underutilized.

Despite having a profound negative impact on the QoL of post-menopausal women, very few patients with GSM seek treatment for their symptoms largely due to the stigmatization of menopause and safety concerns about hormonal treatments. Hence, effective pharmacologics with minimal side effects, like low-dose topical estrogen, are grossly underutilized. It is imperative for healthcare providers to be knowledgeable in recognizing genitourinary symptoms of menopause and adequately counseling patients on the benefits and drawbacks of its treatments.

Acknowledgement

None.

Funding Statement

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Anushka Ghosh, Alana M. Murphy; data collection: Anushka Ghosh; analysis and interpretation of results: Anushka Ghosh; draft manuscript preparation: Anushka Ghosh, Maria J. D’Amico, Yash B. Shah, Whitney R. Smith, Mihir S. Shah, Costas D. Lallas, Alana M. Murphy. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials

The data used in this study is available thought the TriNetX database. To gain access, a request can be made to TriNetX (https://live.trinetx.com) (accessed on 27 July 2025), but costs may be incurred, a data sharing agreement would be necessary, and no patient identifiable information can be obtained.

Ethics Approval

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Christmas M, Huguenin A, Iyer S. Clinical practice guidelines for managing genitourinary symptoms associated with menopause. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2024;67(1):101–114. doi:10.1097/GRF.0000000000000833. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Chang JG, Lewis MN, Wertz MC. Managing menopausal symptoms: common questions and answers. Am Fam Physician 2023;108(1):28–39. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

3. Wasserman MC, Rubin RS. Urologic view in the management of genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Climacteric 2023;26(4):329–335. doi:10.1080/13697137.2023.2202811. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Casiano Evans EA, Hobson DTG, Aschkenazi SO et al. Nonestrogen therapies for treatment of genitourinary syndrome of menopause: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol 2023;142(3):555–570. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000005288. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Khamis Y, Abdelhakim AM, Labib K et al. Vaginal CO2 laser therapy versus sham for genitourinary syndrome of menopause management: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Menopause 2021;28(11):1316–1322. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000001845. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Zerzan NL, Greer N, Ullman KE et al. Energy-based interventions for genitourinary syndrome of menopause: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials and prospective observational studies. Menopause 2025;32(2):176–183. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000002465. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Stair SL, Palmer CJ, Lee UJ. Wealth of knowledge and passion: patient perspectives on vaginal estrogen as expressed on reddit. Urology 2023;182:79–83. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2023.08.040. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Stanley EE, Pope RJ. Characteristics of female sexual health programs and providers in the United States. Sex Med 2022;10(4):100524. doi:10.1016/j.esxm.2022.100524. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Nappi RE, Tiranini L, Martini E, Bosoni D, Righi A, Cucinella L. Medical treatment of female sexual dysfunction. Urol Clin North Am 2022;49(2):299–307. doi:10.1016/j.ucl.2022.02.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Cucinella L, Martini E, Tiranini L et al. Menopause and female sexual dysfunctions. Minerva Obstet Gynecol 2022;74(3):234–248. doi:10.23736/S2724-606X.22.05001-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Doust J, Huguenin A, Hickey M. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause: does everyone have it? Clin Obstet Gynecol 2024;67(1):4–12. doi:10.1097/GRF.0000000000000834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Real-world data for the life sciences and healthcare. TriNetX. 2024 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 25]. Available from: https://trinetx.com/. [Google Scholar]

13. Portman DJ, Gass MLS. Vulvovaginal atrophy terminology consensus conference panel. genitourinary syndrome of menopause: new terminology for vulvovaginal atrophy from the international society for the study of women’s sexual health and the North American Menopause Society. J Sex Med 2014;11(12):2865–2872. doi:10.1111/jsm.12686. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Sturdee DW, Panay N. Recommendations for the management of postmenopausal vaginal atrophy. Climacteric 2010;13(6):509–522. doi:10.3109/13697137.2010.522875. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Nappi RE, Kokot-Kierepa M. Vaginal health: insights, views & attitudes (VIVA)—results from an international survey. Climacteric 2012;15(1):36–44. doi:10.3109/13697137.2011.647840. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. “The 2022 Hormone Therapy Position Statement of The North American Menopause Society” Advisory Panel. The 2022 hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause 2022;29(7):767–794. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000002028. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Rahn DD, Carberry C, Sanses TV et al. Vaginal estrogen for genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Obstet Gynecol 2014;124(6):1147–1156. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000000526. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Suckling J, Lethaby A, Kennedy R. Local oestrogen for vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;103(3):CD001500. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001500.pub2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Cold S, Cold F, Jensen MB, Cronin-Fenton D, Christiansen P, Ejlertsen B. Systemic or vaginal hormone therapy after early breast cancer: a danish observational cohort study. J Natl Cancer Inst 2022;114(10):1347–1354. doi:10.1093/jnci/djac112. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Labrie F, Archer DF, Bouchard C et al. Prasterone has parallel beneficial effects on the main symptoms of vulvovaginal atrophy: 52-week open-label study. Maturitas 2015;81(1):46–56. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2015.02.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Constantine G, Graham S, Portman DJ, Rosen RC, Kingsberg SA. Female sexual function improved with ospemifene in postmenopausal women with vulvar and vaginal atrophy: results of a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Climacteric 2015;18(2):226–232. doi:10.3109/13697137.2014.954996. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Cagnacci A, Xholli A, Venier M. Ospemifene in the management of vulvar and vaginal atrophy: focus on the assessment of patient acceptability and ease of use. Patient Prefer Adherence 2020;14:55–62. doi:10.2147/PPA.S203614. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Ojha N, Bista KD, Bajracharya S, Katuwal N. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause among postmenopausal women in a tertiary care centre: a descriptive cross-sectional study. J Nepal Med Assoc 2022;60(246):126–131. doi:10.31729/jnma.7237. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Sinha A, Ewies AAA. Non-hormonal topical treatment of vulvovaginal atrophy: an up-to-date overview. Climacteric J Int Menopause Soc 2013;16(3):305–312. doi:10.3109/13697137.2012.756466. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Selvi I, Baydilli N, Yuksel D, Akinsal EC, Basar H. Reappraisal of the definition criteria for genitourinary syndrome of menopause, and its effect on quality of life in turkish postmenopausal women. Urology 2020;144:83–91. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2020.07.025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Moral E, Delgado JL, Carmona F et al. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Prevalence and quality of life in Spanish postmenopausal women. The GENISSE study. Climacteric 2018;21(2):167–173. doi:10.1080/13697137.2017.1421921. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Kingsberg SA, Krychman ML. Resistance and barriers to local estrogen therapy in women with atrophic vaginitis. J Sex Med 2013;10(6):1567–1574. doi:10.1111/jsm.12120. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Crandall CJ, Hovey KM, Andrews CA et al. Breast cancer, endometrial cancer, and cardiovascular events in participants who used vaginal estrogen in the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. Menopause 2018;25(1):11–20. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000000956. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. McVicker L, Labeit AM, Coupland CAC et al. Vaginal estrogen therapy use and survival in females with breast cancer. JAMA Oncol 2024;10(1):103–108. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2023.4508. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools