Open Access

Open Access

COMMUNICATION

Gastrointestinal resection is associated with urolithiasis severity among inflammatory bowel disease patients

1 Department of Urology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY 10029, USA

2 The Henry D. Janowitz Division of Gastroenterology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY 10029, USA

* Corresponding Author: Vinay Durbhakula. Email:

Canadian Journal of Urology 2025, 32(6), 659-668. https://doi.org/10.32604/cju.2025.067614

Received 08 May 2025; Accepted 20 August 2025; Issue published 30 December 2025

Abstract

Background: A well-established correlation exists between Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) and urolithiasis. However, the influence of surgical history on the severity of urolithiasis in IBD patients remains underexplored. This study aims to investigate the association between gastrointestinal (GI) bowel resection and urolithiasis severity in patients with IBD. Methods: This retrospective cohort study analyzed 42 patients diagnosed with both IBD and urolithiasis between 2016 and 2024. Patients were categorized based on their history of bowel resection. Primary outcomes included maximal stone burden, need for urolithiasis surgery, and stone recurrence. Secondary outcomes were stone-related clinical events, multiple urolithiasis surgeries, and having a percutaneous nephrolithotomy. Associations between bowel resections and outcomes were assessed using univariate and multivariate regression analyses. Results: The median age was 55 years (range 45–68), with 76% having Crohn’s disease and 24% ulcerative colitis. Of the cohort, 48% had a history of a bowel resection (14 small bowel, 9 ileocolic resection (ICR), 10 subtotal/total colectomy), with 31% having multiple resections. The median interval between bowel resection and urolithiasis diagnosis was 8 years (5–22). Patients with prior bowel resections had significantly higher stone burden (p < 0.001), greater need for urolithiasis surgery (p = 0.03), and increased stone recurrence rates (p = 0.006). On multivariate analysis, bowel resections independently predicted adverse urolithiasis outcomes, with small bowel resections and ICR showing stronger associations than colectomies. Conclusion: Bowel resections are linked to increased urolithiasis severity in IBD patients. These findings highlight the need for proactive preventative therapies and stricter surveillance protocols for IBD patients undergoing bowel resection.Keywords

Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) is a chronic inflammatory disorder affecting the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. This condition, encompassing Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), impacts millions of individuals worldwide and represents a significant global health challenge.1 While the primary symptoms of IBD are localized to the GI system, IBD is often associated with a range of extraintestinal manifestations, including urolithiasis.2 Urolithiasis, which affects up to 30% of IBD patients, is predominantly composed of calcium oxalate stones due to metabolic and absorptive disturbances such as hyperoxaluria, hypocitraturia, and dehydration, and therapies’ side effects.3,4 These disturbances can result in recurrent kidney stones, pain, urinary infections, and acute kidney injuries, often necessitating surgical or medical interventions.5 The prevalence of both symptomatic and asymptomatic urolithiasis is significantly higher in IBD patients compared to the general population, with an increased risk of severe complications and morbidity, such as urinary tract infections, acute kidney injury, sepsis, end-organ failure, and the likelihood of requiring surgical intervention.2,6,7 Enteric hyperoxaluria is a key risk factor for urolithiasis in IBD patients. This condition is characterized by excessive urinary oxalate excretion due to fat malabsorption and altered gut microbiota, with studies indicating increased intestinal oxalate nut in IBD patients compared to normal levels (11%–28% vs. 10%).8 Hypocitraturia and dehydration are additional mechanisms contributing to stone formation in IBD patients, arising as sequelae of chronic diarrhea, bicarbonate loss, metabolic acidosis, and malnutrition in these patients.9,10

Roughly 50% to 80% of patients with Crohn’s disease will require a luminal surgery during their lifetime, and up to one-third of patients with UC similarly may require surgery.11 Procedures such as ileocecal resection (ICR), small bowel resection (SBR), and subtotal/total colectomy alter gut anatomy, physiology, and metabolic balance, potentially intensifying stone-formation risk factors like malabsorption, diarrhea, dehydration, altered bile acid metabolism, and their metabolic alterations.12 Despite these associations, the impact of bowel resections on the severity of urolithiasis in IBD patients who are also stone formers remains poorly characterized in the literature. The aim of this study is to investigate the association between bowel resections due to IBD and the severity of urolithiasis among patients affected by both conditions.

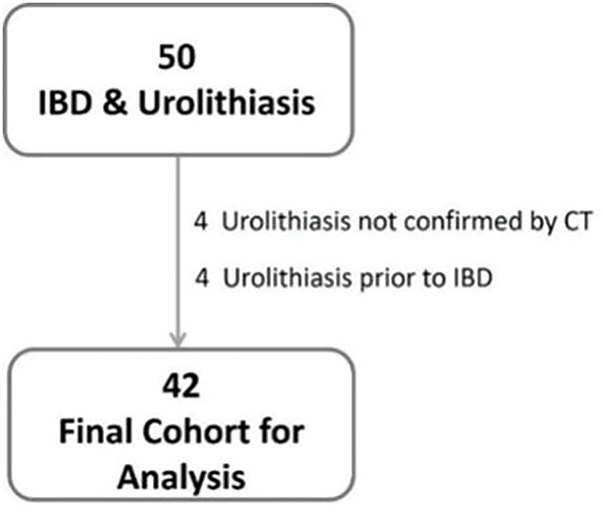

This retrospective cohort study included patients with a confirmed diagnosis of IBD, either CD or UC, who were diagnosed with urolithiasis during their IBD course at a single tertiary care center (Kidney Stone Center, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai) between 2016 and 2024. Patients were identified through a combination of electronic medical record search using relevant diagnostic and procedural codes, as well as through review of office visit records within our stone center. Eligible patients had their IBD diagnosis confirmed by a gastroenterologist and received treatment through nutritional, medical, or surgical interventions. Inclusion criteria for urolithiasis required confirmation by computed tomography (CT). Patients were excluded if their urolithiasis was identified prior to their IBD diagnosis or was not confirmed by CT. This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, with the approval number STUDY-14-00879.

Patients were divided into two groups based on their surgical history at the time of urolithiasis diagnosis: those with prior bowel resection and those without. Bowel resection was defined as the removal of any segment of the GI tract, including the small bowel or colon. Non-luminal surgeries, including perianal procedures, were excluded. Demographic, medical, and surgical data were extracted from electronic health records, including current age, sex, body mass index (BMI), IBD subtype, duration, history, and type of bowel resections, comorbid conditions, stone composition, size, location, and burden. IBD activity was assessed using the Harvey-Bradshaw Index for CD and the clinical Mayo Score for UC. Any level of activity—mild, moderate, or severe—was classified as active disease.

Urolithiasis severity outcomes

The primary outcomes were maximal stone burden, the need for any urolithiasis surgery and stone recurrence. Maximal stone burden was defined as the largest single stone diameter or the cumulative maximal diameters in cases of multiple stones, as determined by CT imaging. Urolithiasis surgeries included ureteroscopy (URS), extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL), or percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL), and surgical decisions were based on the recommended guidelines. Stone recurrence was documented only after a confirmed stone-free interval. Secondary outcomes were more specific and included stone-related clinical events (such as pain, hematuria, infection, stent placement, or emergency department visits), the need for multiple urolithiasis surgeries, and undergoing PCNL.

Statistical comparisons between groups were performed by means of the Fisher-Exact for categorical variables (n, %) and the Mann-Whitney U test for continuous ones (median, interquartile range [IQR]). Univariate and multivariate logistic regressions were performed to evaluate the association between bowel resections and urolithiasis outcomes. In the multivariate models, we adjusted for age, sex, BMI, presence of known urolithiasis risk factors (hyperthyroidism, gout, diabetes mellitus), IBD subtype, and disease activity. All analyses were 2-sided, and statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05. The analyses were done with SPSS v. 29 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

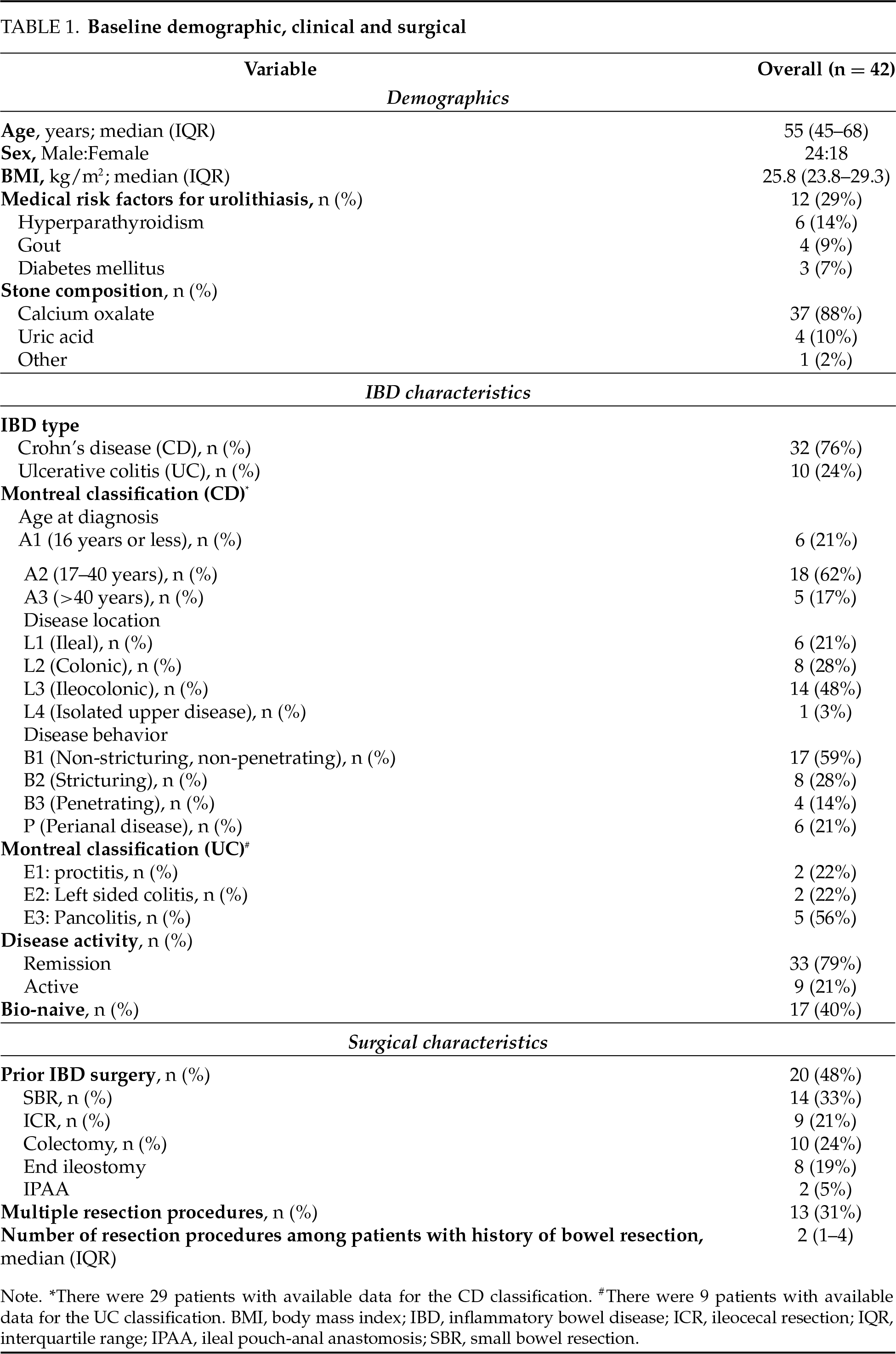

After reviewing the electronic database of our institute, 50 patients diagnosed with both IBD and urolithiasis between 2016 and 2024 were identified. Based on the exclusion criteria, 4 patients were excluded due to urolithiasis being diagnosed prior to IBD, and 4 additional patients were excluded because their diagnosis was not confirmed by CT. This left 42 patients as the final study cohort for analysis (Figure 1). Table 1 summarizes the baseline characteristics of the patients, including demographic, clinical, and surgical variables. The median age was 55 years (IQR 45–68), the median BMI was 25.8 (IQR 23.8–29.3), and 25 patients (60%) were males. Among the IBD subtypes, Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) were present in 76% and 24% of patients, respectively. Seventeen patients (40%) were naïve to biologic treatments. The majority (79%) were in remission, and only one patient (2%) was under steroid treatment at the time of urolithiasis diagnosis.

FIGURE 1. Flowchart diagram (IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; CT, computed tomography)

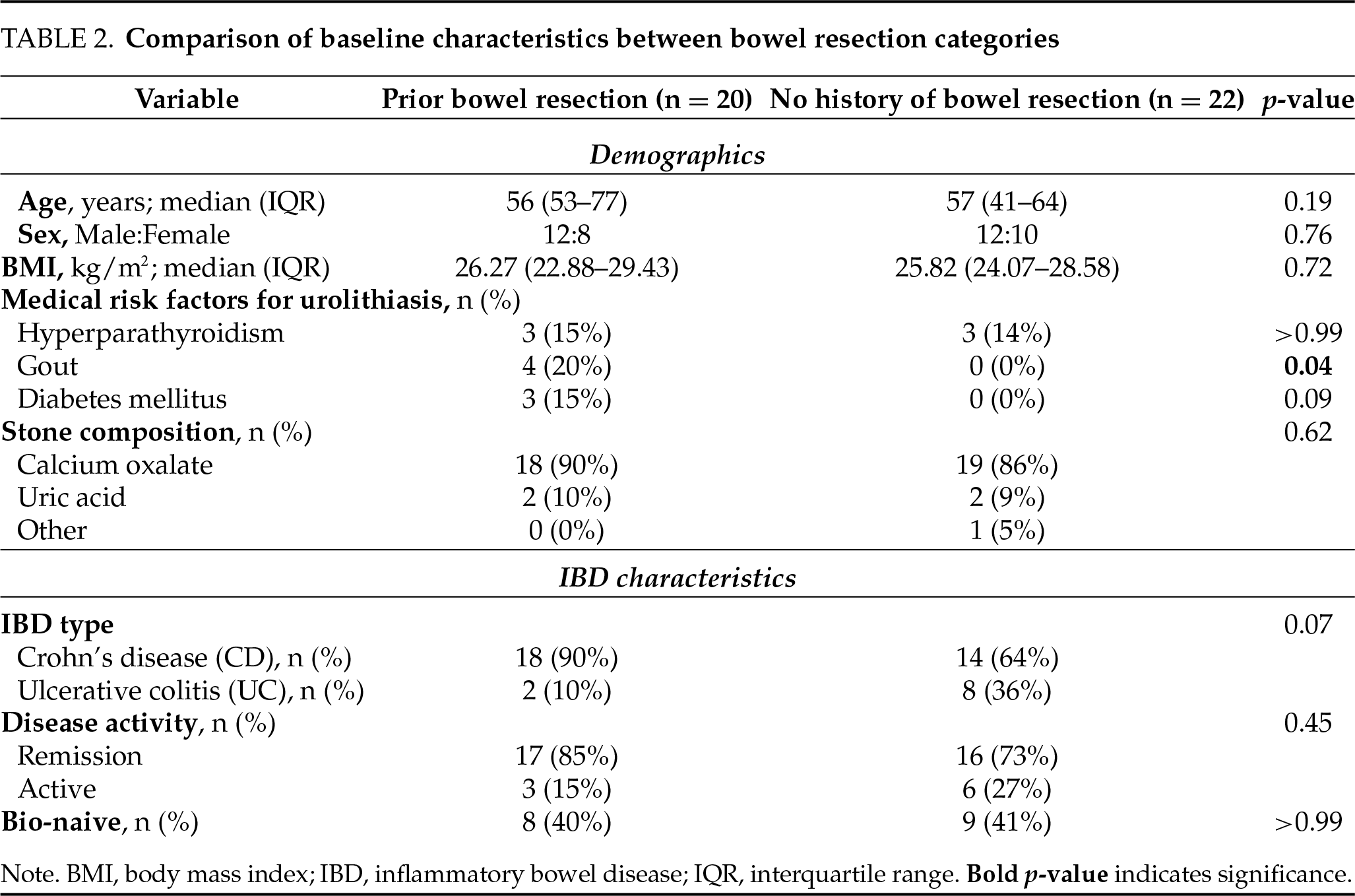

A total of 20 patients (48%) had undergone at least one prior bowel resection, including SBR (n = 14), ICR (n = 9), and colectomy (total/subtotal, n = 10). The majority of patients who had undergone colectomy (8 patients) had an end ileostomy at the time of urolithiasis diagnosis. Thirteen patients (31%) underwent multiple bowel resections during their IBD course. The interval between the most recent bowel resection and the diagnosis of urolithiasis was at least six months for all patients, with a median interval of 8 years (IQR 5–22). It supports the interpretation that stones developed post-resection. Comparison of baseline characteristics between the resection categories showed overall balanced groups, with the only significant difference being a higher prevalence of gout in patients with prior bowel resection (20% vs. 0%, p = 0.04). All other characteristics were comparable between groups (Table 2).

Urolithiases severity outcomes

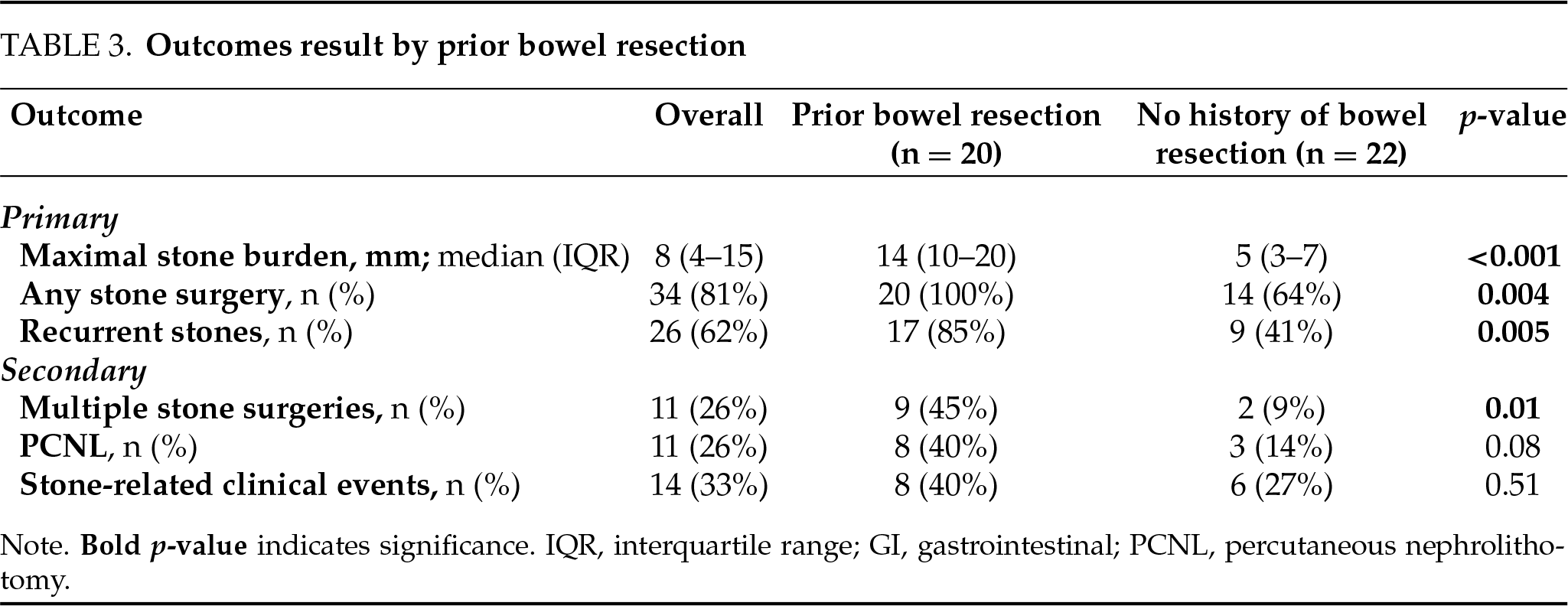

The median maximal stone burden was 8 mm (IQR 4–15), with 81% of patients (34 patients) undergoing at least one urolithiasis surgery, 26% (11 patients) requiring multiple procedures, and 26% (11 patients) undergoing PCNL. The recurrence rate of stones was 62% (26 patients), and 33% of patients (14 patients) experienced stone-related clinical events. Calcium oxalate stones were the most prevalent type among the study cohort, found in 37 patients (88%), followed by uric acid stones, which were present in 4 patients (10%).

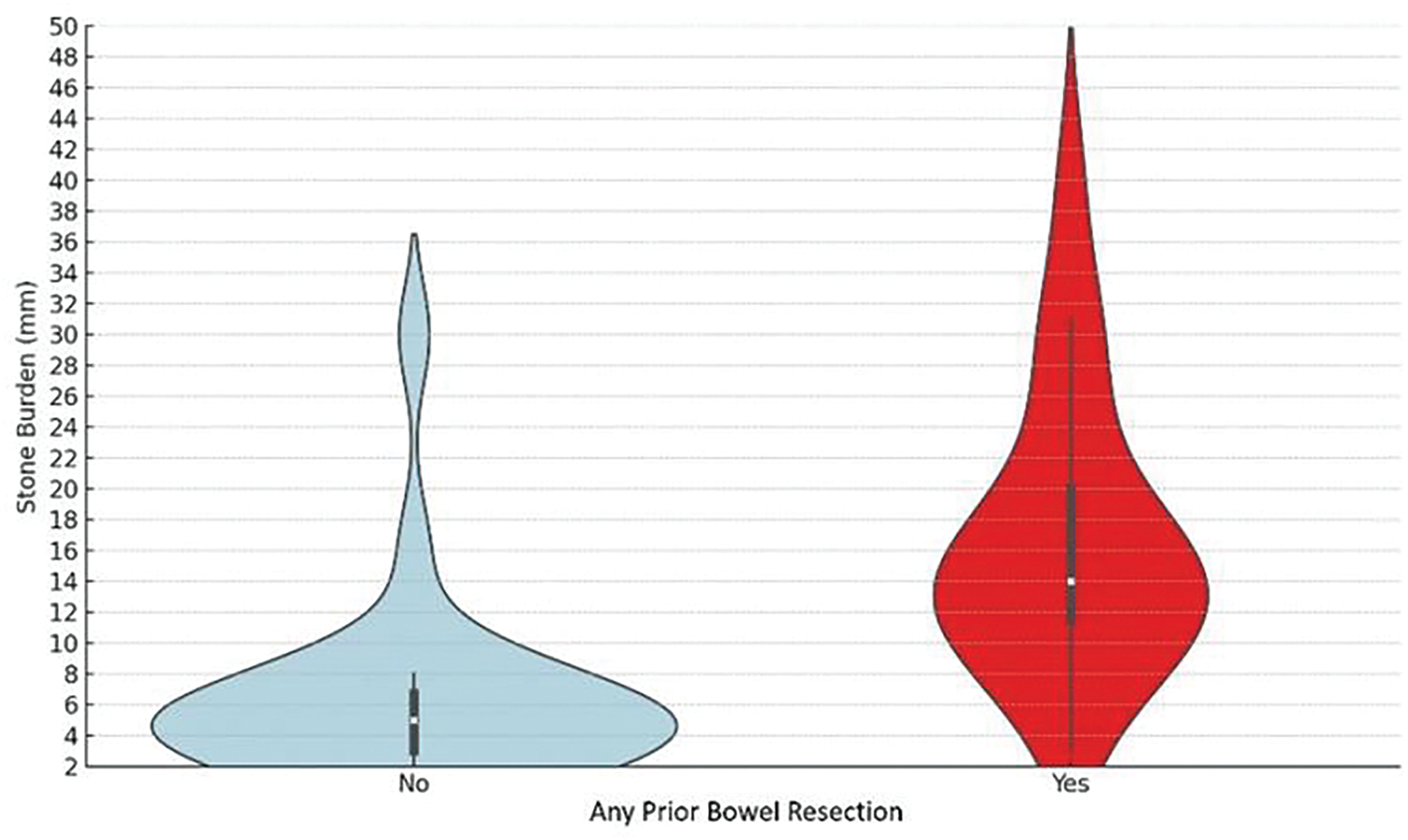

Patients with a history of prior bowel resection exhibited significantly more severe urolithiasis, characterized by a higher stone burden, a greater likelihood of requiring surgical intervention, and an increased incidence of recurrent stones compared to those without prior resection (Table 3). Specifically, the median stone size in the prior bowel resection group was 15 mm (IQR 10–20), compared to 5 mm (IQR 3–7) in the group without resection (Figure 2, p < 0.001), and stone recurrence rates were 85% in the prior bowel resection group, compared to 41% in patients without prior resection (p = 0.005). Most notably, 100% of patients with prior bowel resection required subsequent stone interventions, compared to 64% of those without a history of resection (p = 0.004). Among secondary outcomes, patients with prior bowel resection underwent multiple stone surgeries more frequently (45% vs. 9%, p = 0.01). However, there were no significant differences between the groups in the rates of PCNL or stone-related clinical events.

FIGURE 2. Violin diagrams comparing the maximal stone burden between prior bowel resection categories

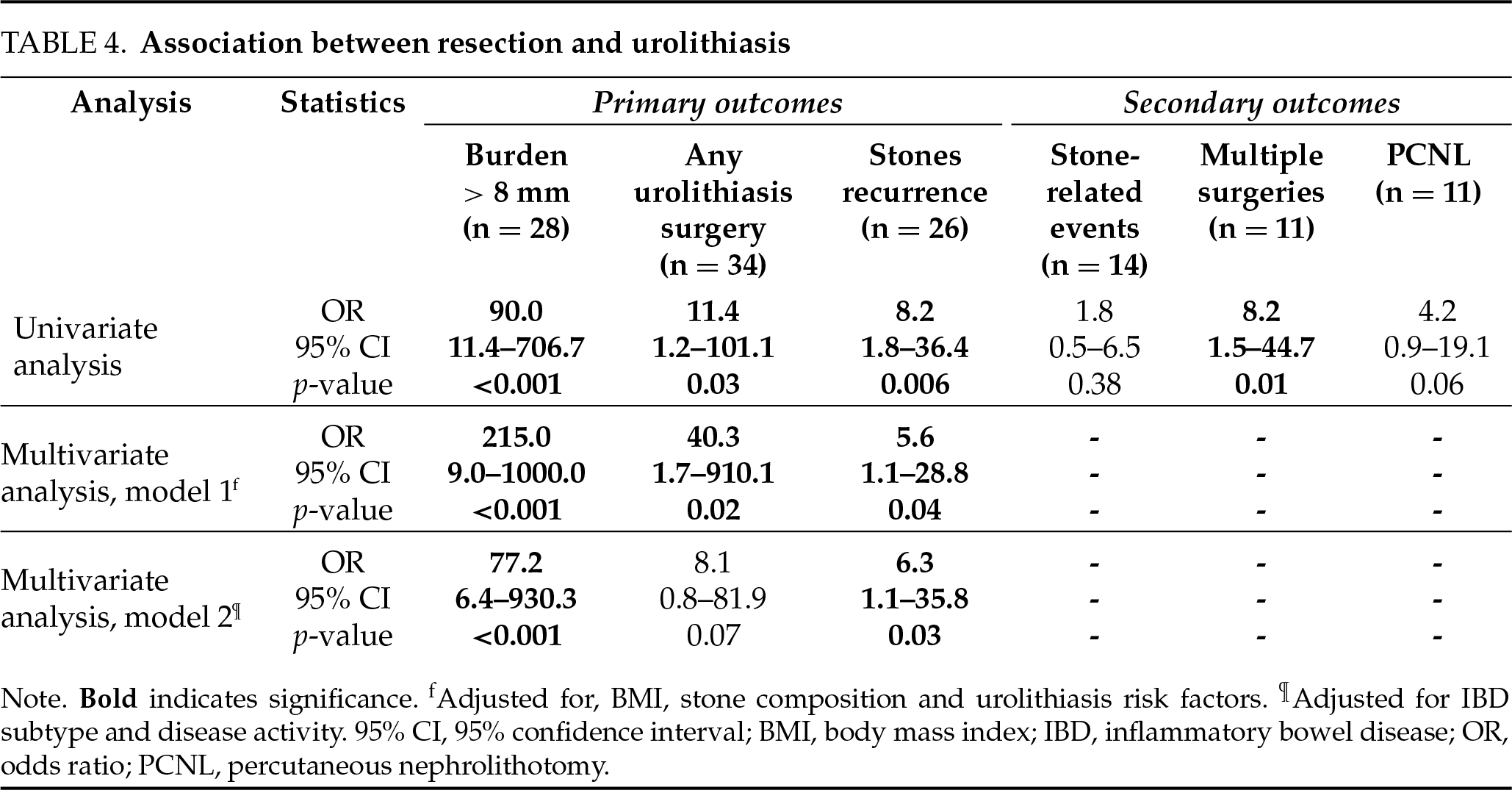

Univariate and multivariate analyses

On univariate analysis (Table 4), prior bowel resection was found to be associated with all the primary outcomes, including stone burden > 8 mm (OR = 90.0, 95% CI [11.0–706.0], p < 0.001), urolithiasis surgery (OR = 24.0, 95% CI [1.3–450.0]) and stones recurrence (OR = 8.2, 95% CI [1.8–36.4], p = 0.006). Two multivariate models were constructed to account for confounders (Table 4): Model 1 focused on demographics, while Model 2 addressed IBD characteristics. In Model 1, adjusted for BMI, stone composition and urolithiasis risk factors, the results remained consistent, identifying prior bowel resection as a strong independent predictor of stone burden > 8 mm (OR = 215.0, 95% CI [9.0–1000.0], p < 0.001), urolithiasis surgery (OR = 40.3, 95% CI [1.7–910.0], p = 0.02), and stone recurrence (OR = 5.6, 95% CI [1.1–28.8], p = 0.04). In Model 2, adjusted for IBD subtype and disease activity, prior bowel resection remained a strong independent predictor of stone burden > 8 mm (OR = 77.2, 95% CI [6.4–930.3], p < 0.001) and stone recurrence (OR = 6.3, 95% CI [1.1–35.8], p = 0.03), with a trend toward predicting urolithiasis surgery (OR = 8.1, 95% CI [0.8–81.9], p = 0.07). Multivariate analysis was not performed to secondary outcomes due to low number of events.

These associations were particularly pronounced for patients who underwent SBR or ICR, compared to those with colectomies. SBR and ICR were found both to be associated with stone burden > 8 mm (OR = 15.0, 95% CI [2.7–82.0], p = 0.002 and OR = 5.4, 95% CI [1.0–30.0], p = 0.05, respectively), while SBR was associated with having a PCNL (OR = 6.0, 95% CI [1.3–26.6], p = 0.02) and ICR with multiple stone surgeries (OR = 5.6, 95% CI [1.1–27.4], p = 0.03). Colectomy was not statistically associated with any outcomes; however, it showed a trend toward an association with undergoing PCNL (OR = 4.3, 95% CI [0.9–19.9], p = 0.06).

IBD patients, with their higher incidence of urolithiasis and history of bowel resections, represent a unique population of particular interest for studying urolithiasis outcomes. This study aims to explore the relationship between bowel resections and the severity of urolithiasis in patients with both IBD and urolithiasis. Our findings demonstrate a significant association, identifying prior bowel resections as a potential risk factor for adverse urolithiasis outcomes. IBD Patients with both prior bowel resection and urolithiasis tend to exhibit a higher stone burden (~14 mm), increased rates of urolithiasis surgeries (100%), and more frequent stone recurrences (85%). These effects appear to be particularly pronounced when small bowel or terminal ileum are involved in the resection.

Bowel resections and urolithiasis

Surgical intervention of bowel resection is a common component in the management of IBD. As many as 80% of CD patients require bowel resection within the first 20 years after diagnosis,11 primarily SBR and ICR, which are typically performed to manage complications such as intestinal obstruction, internal fistulas, abscesses, and resistance to medical therapy.13,14 Conversely, the risk of colectomy in UC patients is 10–30% within a similar timeframe.13 Common indications for intervention include toxic megacolon, refractory disease, and dysplasia/cancer.11 Our study of patients with both IBD and urolithiasis reflects these high prevalences of bowel resections (48%). Bowel resections can contribute to increased risk of calcium oxalate and uric acid stones formation by causing hyperoxaluria, hypocitraturia, and reduced urine volume.5,15,16

The mechanisms underlying urolithiasis risk in patients with prior bowel resection are influenced by the specific intestinal segment resected. SBR and ICR might exacerbate fat malabsorption and diarrhea, which increase enteric hyperoxaluria and the formation of calcium oxalate stones.4 Research shows that 54% of patients with significantly shortened small bowels (median length ≤ 13.5% of their original size), develop severe hyperoxaluria.17 Additionally, strong correlations have been observed between the length of ileal resection and both increased urinary oxalate excretion (R = 0.520, p = 0.039) and enhanced intestinal oxalate absorption (R = 0.609, p = 0.012).17 The same mechanism has been described as leading to hyperoxaluric stone formation following malabsorptive bariatric surgeries.18,19 Colectomy, on the other hand, contributes to dehydration, reduced urine output (a mean decrease of nearly 500 mL/day), and gastrointestinal/renal bicarbonate loss due to diarrhea or impaired water reabsorption. These effects promote hypocitraturia and low urine pH levels and increase the risk of uric acid stones.4,9,20 The distinct metabolic alterations associated with SBR and colectomies can lead to differing urolithiasis outcomes, including variations in the types of kidney stones formed and their clearance rates. Calcium oxalate monohydrate stones, which are more commonly associated SBR and ICR, exhibit lower clearance rates compared to other types, such as uric acid stones, often requiring more interventions.21 Furthermore, the higher recurrence rate of calcium stones—40% within 5 years and 75% within 20 years—may lead to an increased need for surgical interventions over time.22 This could explain why the rate of surgical interventions is higher among patients who undergo SBR compared to those who have colectomies.

Bowel resections may not only directly contribute to urolithiasis but also serve as a marker of more severe IBD, which inherently causes greater metabolic disturbances contributing to urolithiasis formation and severity. The necessity for bowel resection frequently indicates advanced IBD, as demonstrated by Hefti et al., who reported that severe inflammation (hazard ratio [HR] = 3.3) and steroid use (HR = 5) are strong predictors of SBR.23

Nutritional and antibiotic use considerations

IBD patients often adopt dietary patterns that increase their risk of urolithiasis by amplifying hyperoxaluria. They consume less fiber (11.9 ± 4.7 g/day vs. 15.5 ± 8.3 g/day in controls) and more lipids (68.9 ± 15.2 g/day vs. 59.4 ± 19.0 g/day).24 These patterns are more pronounced after bowel resections.25 Lower fiber intake which was found to be associated with hypocitraturia,26,27 may also disrupt gut microbiota, deplete Oxalobacter formigenes, which degrades dietary oxalate, and increase oxalate absorption and hyperoxaluria.3 In addition, high lipid intake worsens fat malabsorption, causing calcium to bind free fatty acids instead of oxalate, further promoting hyperoxaluria.3

Frequent antibiotic use, which is common among IBD patients, can also contribute to bowel dysbiosis and reduce populations of oxalate-degrading bacteria, further promoting stone formation. Antibiotic exposure was found to be associated with increase in kidney stone risk, with the strongest association seen when antibiotics were used within 3–6 months prior to stone diagnosis; this increased risk persists for up to five years after exposure.28 Additionally, more healthy individuals were found to be colonized by Oxalobacter formigenes, a key oxalate-degrading bacterium, compared to only kidney stone patients—implicating antibiotic-induced loss of this species as a risk factor. These findings underscore that antibiotic-induced microbiome disruption is a shared risk pathway for both IBD and nephrolithiasis, and that judicious antibiotic stewardship is crucial for reducing long-term complications in these populations.29

Urolithiasis severity in IBD patients

While most studies focused on urolithiasis and IBD have evaluated the incidence of urolithiasis as an outcome, our study investigated the severity of urolithiasis. We propose that the same mechanical, absorptive, and metabolic alterations that contribute to stone formation also intensify it, causing higher stone burdens, the need for more stone related surgeries and accelerated stone recurrence. We believe that adverse outcomes of urolithiasis may hold greater clinical relevance in IBD patients than mere incidence. Many small, asymptomatic renal stones are included in incidence outcomes but are typically not treated, and are instead managed through observation as recommended by guidelines.25 IBD patients with a history of bowel resection, being at increased risk for urolithiasis-related complications, may benefit from more intensive monitoring and preventive strategies. This could include dietary modifications to reduce oxalate absorption, pharmacologic interventions such as citrate supplementation, and more strict hydration protocols. Additionally, identifying high-risk patients, such as those undergoing multiple resections or with a history of SBR/ICR, may enable earlier and more targeted interventions to mitigate the risk of recurrent stones and adverse outcomes.

In addition, IBD surveillance is evolving to minimize radiation exposure, with intestinal ultrasound and magnetic resonance enterography emerging as the preferred imaging tools.30 Consequently, the use of computed tomography is expected to decline, reducing the likelihood of incidental urolithiasis being detected by non-urologic providers. This shift highlights the growing importance of identifying high-risk IBD patients who may benefit from targeted urolithiasis imaging, such as renal ultrasound or non-contrast computed tomography scans.

The primary limitations of our study stem from its retrospective design. First, IBD is a dynamic condition, with patients frequently undergoing treatment adjustments based on disease relapses. Unfortunately, we were unable to adequately capture these temporal changes in our analysis. This lack of longitudinal data limits our ability to fully elucidate the pathophysiologic mechanisms underlying our findings. Second, we did not have access to urine metabolic profiles, which could have provided valuable insights. Third, our sample size is relatively small, limiting the strength of our conclusions. However, the co-incidence of IBD and urolithiasis is relatively low in the general population. Lastly, although a difference in gout prevalence between the groups could potentially bias the results, we addressed this by performing a multivariable analysis adjusting for gout. Moreover, upon reviewing the four patients with gout, all were found to have calcium oxalate stones, suggesting that gout was not the underlying cause of their stone formation. While a multi-institutional design could have strengthened the study, this was intended as a single-center pilot to assess feasibility and generate hypotheses for future prospective, multi-site work.

This study highlights a significant association between bowel resections and increased urolithiasis severity in IBD patients. IBD patients with prior bowel resections may benefit from tailored preventive strategies, such as dietary modifications, pharmacological interventions, and optimized hydration protocols. Despite the limitations of this study, the findings emphasize the need for further research to improve the management of urolithiasis in high-risk IBD patients. Future prospective studies with larger cohorts, a more balanced representation of CD and UC patients, and comprehensive metabolic profiling are essential to validate and build upon these results.

Acknowledgement

Not applicable.

Funding Statement

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author Contributions

Conception and design: Vinay Durbhakula, Ziv Savin; Acquisition of data: Vinay Durbhakula, Ziv Savin, Einat Savin-Shalom, Eve Frangopoulos; Statistical analysis: Ziv Savin, Vinay Durbhakula, Blair Gallante; Analysis and interpretation: Vinay Durbhakula, Ziv Savin, Einat Savin-Shalom, Kavita Gupta; Drafting of the manuscript: Vinay Durbhakula; Critical revision of the manuscript: Ziv Savin, Stephanie L. Gold, William M. Atallah, Mantu Gupta; Supervision: Mantu Gupta. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials

The data supporting this study’s findings are available on request from the corresponding author. The data is not publicly available due to ethical issues and the participants’ privacy.

Ethics Approval

Ethical approval to report this study was obtained from the ethics committee of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, STUDY-14-00879, date 22 January 2025.

Conflicts of Interest

SG: Nestle Nutrition Institute Fellow 2023, supported by a Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation Career Development Award, Medical Board Member of Nutritional Therapy for IBD.

References

1. Wang R, Li Z, Liu S, Zhang D. Global, regional and national burden of inflammatory bowel disease in 204 countries and territories from 1990 to 2019: a systematic analysis based on the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. BMJ Open 2023;13(3):e065186. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2022-065186. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Kumar S, Pollok R, Goldsmith D. Renal and urological disorders associated with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2023;29(8):1306–1316. doi:10.1093/ibd/izac140. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Siener R, Ernsten C, Speller J et al. Intestinal oxalate absorption, enteric hyperoxaluria, and risk of urinary stone formation in patients with Crohn’s disease. Nutrients 2024;16(2):264. doi:10.3390/nu16020264. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Gkentzis A, Kimuli M, Cartledge J, Traxer O, Biyani CS. Urolithiasis in inflammatory bowel disease and bariatric surgery. World J Nephrol 2016;5(6):538–546. doi:10.5527/wjn.v5.i6.538. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Singh A, Khanna T, Mahendru D et al. Insights into renal and urological complications of inflammatory bowel disease. World J Nephrol 2024;13(3):96574. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

6. Trad G, Chauhan S, Brockway M, Diaz V, Gemil H. Nephrolithiasis in Crohn’s disease patients: a review of the literature. GSC Adv Res Rev 2022;11(1):31–36. [Google Scholar]

7. Varda BK, McNabb-Baltar J, Sood A et al. Urolithiasis and urinary tract infection among patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a review of US emergency department visits between 2006 and 2009. Urology 2015;85(4):764–770. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2014.12.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Hoppe B, von Unruh GE, Blank G et al. Absorptive hyperoxaluria leads to an increased risk for urolithiasis or nephrocalcinosis in cystic fibrosis. Am J Kidney Dis 2005;46(3):440–445. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.06.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Zuckerman JM, Assimos DG. Hypocitraturia: pathophysiology and medical management. Rev Urol 2009;11(3):134–144. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

10. Gamage KN, Jamnadass E, Sulaiman SK et al. The role of fluid intake in the prevention of kidney stone disease: a systematic review over the last two decades. Turk J Urol 2020;46(Supp1):S92–S103. doi:10.5152/tud.2020.20155. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Lightner AL, Pemberton JH, Dozois EJ et al. The surgical management of inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Probl Surg 2017;54(4):172–250. doi:10.1067/j.cpsurg.2017.02.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Utrilla Fornals A, Costas-Batlle C, Medlin S et al. Metabolic and nutritional issues after lower digestive tract surgery: the important role of the dietitian in a multidisciplinary setting. Nutrients 2024;16(2):246. doi:10.3390/nu16020246. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Farmer RG, Hawk WA, Turnbull RBJr. Indications for surgery in Crohn’s disease: analysis of 500 cases. Gastroenterology 1976;71(2):245–250. doi:10.1016/s0016-5085(76)80196-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Seifarth C, Kreis ME, Gröne J. Indications and specific surgical techniques in Crohn’s disease. Viszeralmedizin 2015;31(4):273–279. doi:10.1159/000438955. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Dimke H, Winther-Jensen M, Allin KH, Lund L, Jess T. Risk of urolithiasis in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a nationwide Danish cohort study 1977–2018. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021;19(12):2532–2540.e2. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2020.09.049. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Fagagnini S, Heinrich H, Rossel JB et al. Risk factors for gallstones and kidney stones in a cohort of patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. PLoS One 2017;12(10):e0185193. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0185193. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Hylander E, Jarnum S, Jensen HJ, Thale M. Enteric hyperoxaluria: dependence on small intestinal resection, colectomy, and steatorrhoea in chronic inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol 1978;13(5):577–588. doi:10.3109/00365527809181767. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Bhatti UH, Duffy AJ, Roberts KE, Shariff AH. Nephrolithiasis after bariatric surgery: a review of pathophysiologic mechanisms and procedural risk. Int J Surg 2016;36(Pt D):618–623. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.11.025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Sinha MK, Collazo-Clavell ML, Rule A et al. Hyperoxaluric nephrolithiasis is a complication of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. Kidney Int 2007;72(1):100–107. doi:10.1038/sj.ki.5002194. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Witting C, Langman CB, Assimos D et al. Pathophysiology and treatment of enteric hyperoxaluria. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2021;16(3):487–495. doi:10.2215/cjn.08000520. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Johnston MJ, Sinha M, Pietropaolo A, Somani BK. Do outcomes of ureteroscopic stone treatment vary with stone composition? A prospective analysis. Cent Euro J Urol 2022;75(4):405–408. doi:10.5173/ceju.2022.185. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Worcester EM, Coe FL. Clinical practice. Calcium kidney stones. N Engl J Med 2010;363(10):954–963. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1001011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Hefti MM, Chessin DB, Harpaz NH, Steinhagen RM, Ullman TA. Severity of inflammation as a predictor of colectomy in patients with chronic ulcerative colitis. Dis Colon Rectum 2009;52(2):193–197. doi:10.1007/DCR.0b013e31819ad456. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Principi M. Differences in dietary habits between patients with inflammatory bowel disease in clinical remission and a healthy population. Ann Gastroenterol 2018;31:469. doi:10.20524/aog.2018.0273. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. de Castro MM, Corona LP, Pascoal LB et al. Dietary patterns associated to clinical aspects in Crohn’s disease patients. Sci Rep 2020;10(1):7033. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-64024-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Maddahi N, Aghamir SMK, Moddaresi SS et al. The association of Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension-style diet with urinary risk factors of kidney stones formation in men with nephrolithiasis. Clin Nutr ESPEN 2020;39(4):173–179. doi:10.1016/j.clnesp.2020.06.021. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Hess B, Michel R, Takkinen R, Ackermann D, Jaeger P. Risk factors for low urinary citrate in calcium nephrolithiasis: low vegetable fibre intake and low urine volume to be added to the list. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1994;9(6):642–649. doi:10.1093/ndt/9.6.642. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Neuhaus TJ. Urinary oxalate excretion in urolithiasis and nephrocalcinosis. Arch Dis Child 2000;82(4):322–326. doi:10.1136/adc.82.4.322. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Scotland K, Lange D. The link between antibiotic exposure and kidney stone disease. Ann Transl Med 2018;6(18):371. doi:10.21037/atm.2018.07.23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Pruijt MJ, de Voogd FAE, Montazeri NSM et al. Diagnostic accuracy of intestinal ultrasound in the detection of intra-abdominal complications in Crohn’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Crohn’s Colitis 2024;18(6):958–972. doi:10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjad215. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools