Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Modern diagnostics: ultrasound elastography and magnetic resonance imaging in initial evaluation of testicular cancer

1 Department of Radiology, Medicalpark Hospital, Ankara, 06680, Turkey

2 Medicine School Radiology Department, Yüksek İhtisas University, Ankara, 06530, Turkey

* Corresponding Author: Şeref Barbaros Arik. Email:

Canadian Journal of Urology 2025, 32(6), 569-578. https://doi.org/10.32604/cju.2025.068094

Received 21 May 2025; Accepted 18 August 2025; Issue published 30 December 2025

Abstract

Objectives: Differentiating benign from malignant testicular lesions is essential to avoid unnecessary surgery and ensure timely intervention. While conventional ultrasound remains the first-line imaging method, elastography and MRI provide additional functional and structural information. This study assesses the diagnostic utility of testicular elastography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in differentiating benign and malignant testicular lesions. Methods: Patients with sonographically detected testicular masses were retrospectively evaluated using elastography, scrotal MRI, and tumor markers. Quantitative and qualitative imaging findings, lesion size, and laboratory values were recorded. Statistical analyses included Fisher’s exact test, logistic regression, Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis, and machine learning classification using the eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) model. Results: Our analysis demonstrated that quantitative elastography significantly predicts malignancy (p = 0.042), with high diagnostic power (Area under the Curve [AUC] = 0.91). Additionally, Doppler ultrasound vascularity showed a statistically significant positive correlation with malignancy risk (p = 0.0033), highlighting its value in diagnosis. In contrast, qualitative elastography and MRI contrast enhancement lacked statistical significance. MRI diffusion restriction provided valuable insight into malignancy risk, though the latter did not reach statistical significance. An XGBoost model incorporating imaging and laboratory parameters showed high precision in detecting malignancies (85.7%). Conclusion: Findings underscore the importance of Doppler ultrasound as the primary diagnostic tool, with elastography and diffusion MRI aiding in cases of diagnostic ambiguity. The combined use of all imaging modalities and laboratory markers enhances diagnostic accuracy in evaluating testicular masses.Keywords

Testicular cancer is the most common non-hematogenous malignancy in men aged 15 to 49. According to the U.S. data, the lifetime risk of developing testicular cancer in men is estimated to be 1 in 268, while the risk of dying from testicular cancer is 1 in 5000.1,2 The most common subtype of testicular cancer is seminoma. The significance of testicular cancer lies in its treatability, especially for young men.2,3

In daily practice, the typical complaint of testicular cancer is a painless and palpable hardness.1,3,4 One-third of patients may initially receive a misdiagnosis of epididymitis, orchitis, or hydrocele. At the time of diagnosis, one in five patients may be diagnosed with metastatic disease.1

The laboratory markers used in the diagnosis of testicular cancer are alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG), and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). If the histopathological analysis reveals pure seminoma in the patient’s cancer, an increase in alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels is not anticipated. The presence of elevated AFP levels suggests the existence of a non-seminomatous germ cell tumor (NSGCT). In seminomas, elevated levels of serum β-hCG and LDH may be observed; however, an increase in β-hCG is primarily seen in NSGCTs. An elevation in LDH typically indicates the presence of advanced disease. Tumor markers are particularly useful in monitoring metastatic disease and in the early detection of relapse.1,3

The preferred initial imaging modality for the evaluation of testicular diseases is ultrasound (US). Even non-palpable nodules during a physical examination can be easily detected through US examination.5,6 In cases where diagnosis is challenging, advanced ultrasound examinations (elastography and contrast-enhanced ultrasound) and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can provide valuable additional information.7,8

Elastography examination is an advanced ultrasound imaging technique that determines tissue stiffness using ultrasound. The principle of elastography examination is based on calculating the amount of displacement in tissue resulting from the pressure effect generated by sound waves. With the effect of sound waves, hard tissues displace less, while soft tissues displace more.5,9 By measuring this displacement, we can make assessments about the stiffness of the tissue. Malignant lesions frequently alter the stiffness of the tissue. For this reason, elastography is utilized as an advanced ultrasound examination to differentiate between benign and malignant lesions.10,11 Since contrast-enhanced ultrasound examination is not available in Turkey, it is not utilized as an advanced ultrasound evaluation for testicular cancer in our clinic.

Although testicular MRI is not commonly used in routine practice, it is an imaging modality reported to have high sensitivity and specificity in testicular evaluation and can differentiate between seminomas and non-seminomatous testicular cancers in some cases. Testicular MRI can provide reliable and detailed information in cases where there is uncertainty.1,3

In this paper, we aimed to present the testicular imaging algorithm utilized in evaluating patients who presented to our clinic, the advanced imaging techniques we employed in challenging diagnostic situations (elastography ultrasound and testicular MRI), and the pathological correlation of these advanced imaging methods. Although testicular cancer diagnosis has been extensively studied, the integration of elastography and MRI in a real-world clinical pathway is still evolving. This study contributes to the literature by demonstrating how these advanced imaging techniques can complement each other when conventional methods are inconclusive, particularly in small lesions.

In this study, a retrospective analysis was conducted on 1258 scrotal Doppler ultrasound examinations performed in radiology clinic of Medicalpark Hospital between 2022 and 2024. The images of the patients who underwent ultrasound examination in our clinic were obtained from the picture archiving and communication system (PACS). The pathology reports of patients with detected masses, laboratory values, ultrasound reports, and, if available, scrotal MRI reports were obtained from the hospital information system.

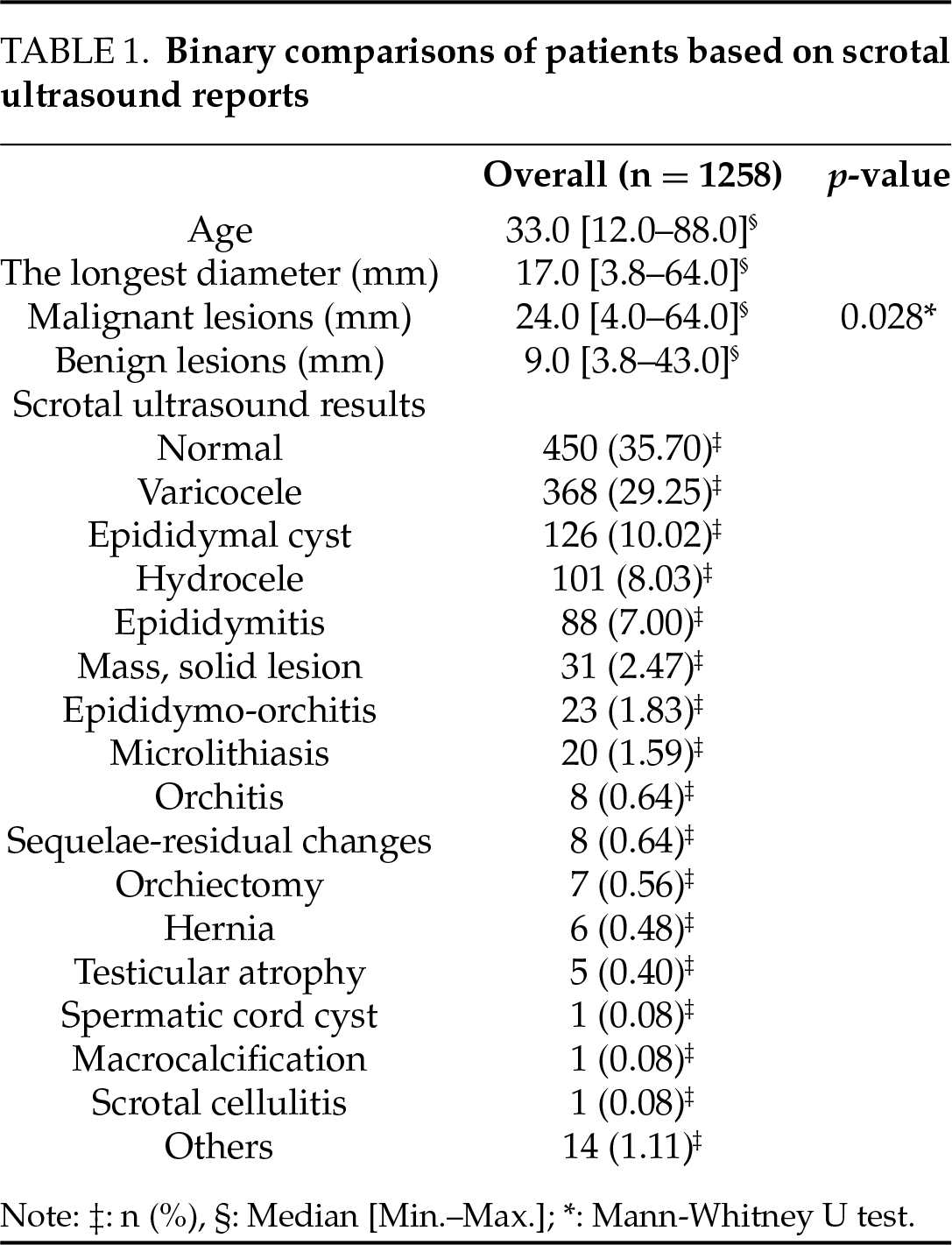

The mean age of the patients was 34.9 years (median: 33 years). A mass was detected in 31 of these patients. Upon reviewing the retrospective ultrasound reports of patients with detected masses, it was noted that 14 patients underwent “quantitative elastography” examination, while 24 patients underwent “qualitative elastography” examination. It was observed that 20 of the patients with detected masses underwent “scrotal magnetic resonance imaging” examination. Of the patients with detected masses, 22 patients had pathological reports indicating malignancy (17 seminomas, 5 mixed germ cell tumors) (Table 1).

All procedures in the study were performed on human participants in accordance with national research committee standards and ethical guidelines for the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and later amendments. The Yüksek İhtisas University, Turkey, Çankaya Non-invasive Investigation Ethics Committee approved this study (date: 04 May 2024, number: 2024-03-01). Diagnosis methods were performed according to the approved guidelines. All patients gave written informed consent. A pathologist performed histopathological evaluation according to international guidelines.

Scrotal color Doppler ultrasound imaging is performed as the first-line modality in patients who apply to our clinic with complaints of scrotal pain and palpable stiffness. For cases with diagnostic uncertainty, both ultrasound and MRI were performed on the same patient to allow for direct modality comparison. Although MRI and ultrasound findings were analyzed for the same group of patients, representative images from the same patient could not always be presented due to limitations in archival retrieval.

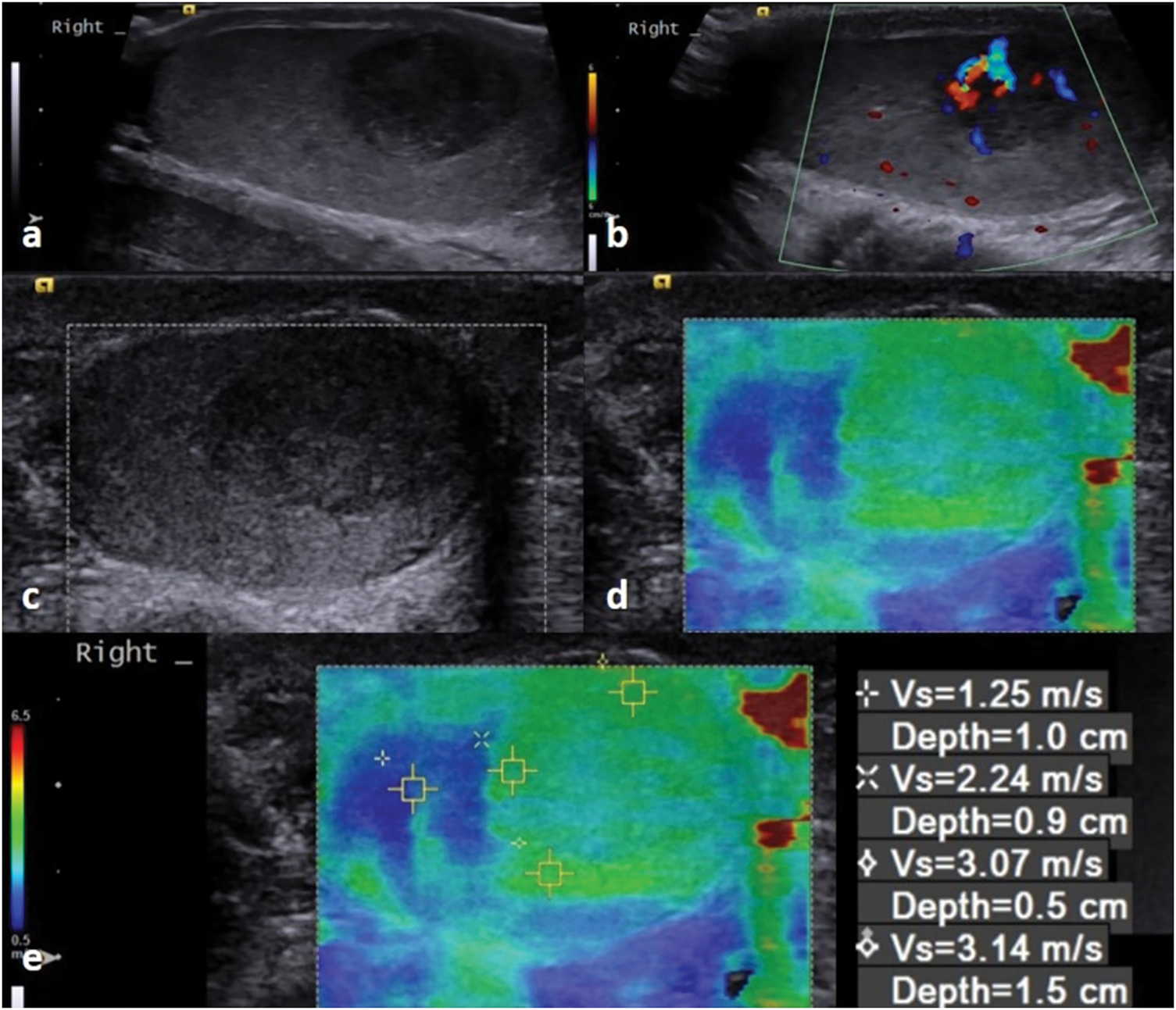

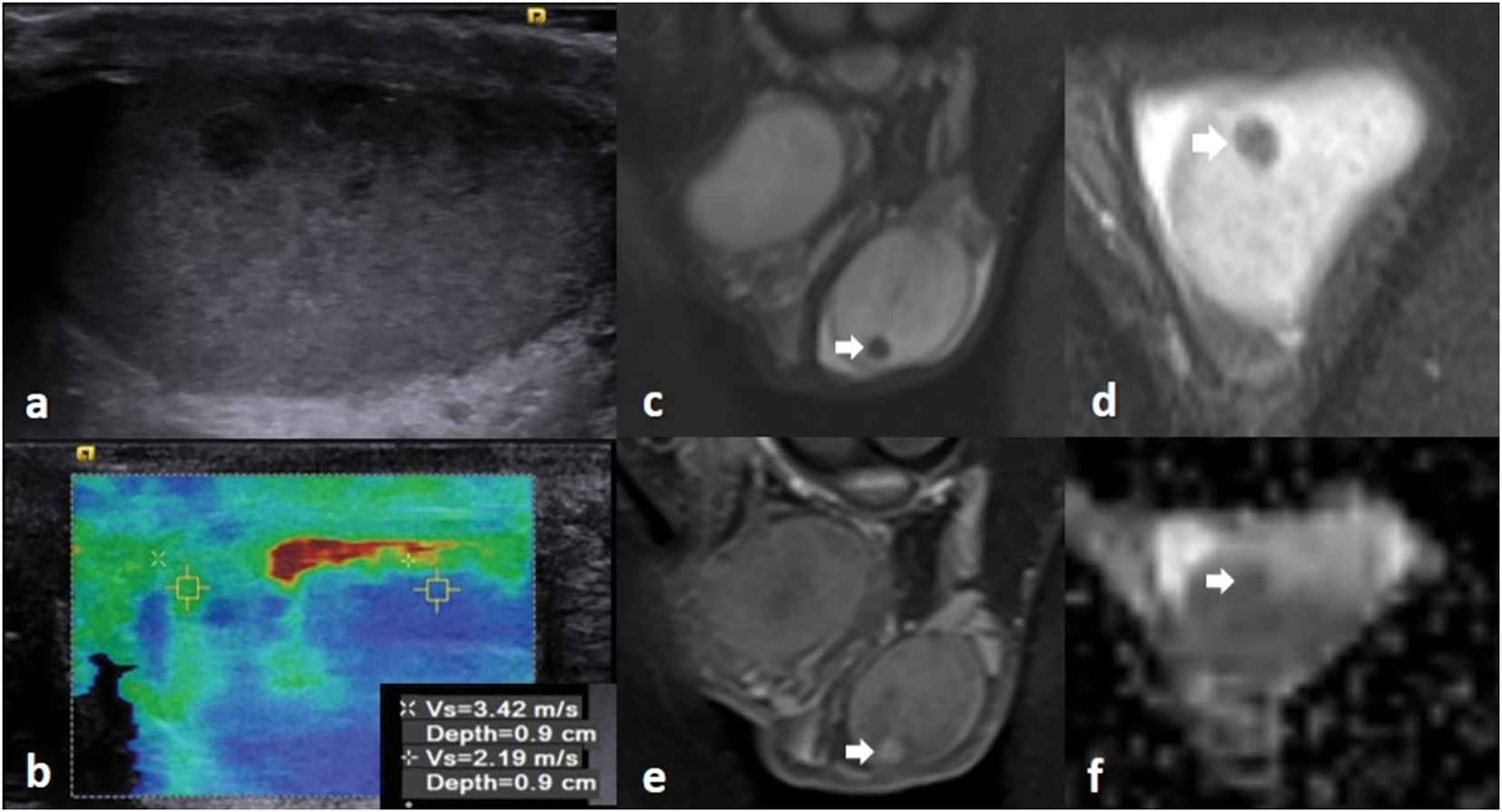

During the testicular ultrasound, the patients lie in the supine position. Patients are instructed to position the penis superiorly, and draping is used for privacy. Patients are primarily evaluated by gray scale (B-mode) examination. The echogenicity of the lesion relative to the testicular tissue, edge characteristics, presence of calcifications and cystic areas, and dimensions are described in detail in the report. The longest dimensions are specified in all three axes (TR × AP × CC). Blood supply is evaluated with color Doppler ultrasound. Elastography examination is performed in cases with difficulty in diagnosis, and stiffness rates are calculated compared to normal testicular tissue (Figure 1). Testicular MRI imaging is recommended for patients who still cannot reach a result (Figure 2).

FIGURE 1. Ultrasound images of a 28-year-old patient with a pathology report indicating seminoma. (a) There is a 10 mm hypoechoic solid lesion that can be seen in the B-mode image. (b) In the Doppler image, there is a presence of vascularity. (c,d) A qualitative elastography image shows a hard lesion compared to the testicular parenchyma. (e) In the quantitative elastography images, the results of measurements taken from various depths of the lesion can be seen

FIGURE 2. MRI images of a 34-year-old patient. (a) There is a 5 mm hypoechoic nonvascular solid lesion in B mode ultrasonography, which was observed to be harder than the normal testicular parenchyma in (b) ultrasound elastography images (pathology report: seminoma). (c,d) The lesion (white arrow) appears hypointense on T2-weighted images. The lesion (white arrow) enhanced on (e) postcontrast fat-suppressed T1 image, and it appears hypointense on (f) the ADC map, restricting diffusion

In our radiology clinic, we perform testicular ultrasound, Doppler, and shear wave elastography examinations using the Siemens S3000 system (Siemens Healthineers, Siemensstrasse 1, 91301 Forchheim, Germany) equipped with 18L6 HD linear and 9L4 linear transducers. All ultrasound and elastography procedures were performed using the same device and by a single radiologist with over 10 years of experience in scrotal imaging. This approach was adopted to ensure technical consistency and to minimize interobserver variability in both qualitative and quantitative elastography evaluations. The imaging of patients recommended for testicular MRI is performed using the 1.5T Siemens Symphony A Tim device (Siemens Healthineers, Siemensstrasse 1, 91301 Forchheim, Germany).

In summarizing the data obtained from the study, descriptive statistics were provided in table format for numerical variables based on their distribution, presenting values as mean or median, along with minimum and maximum values. Categorical variables were summarized as numbers and percentages. The normality of numerical variables was assessed using appropriate tests based on sample size and the characteristics of the data.

In the comparisons of two independent groups, since the numerical variables did not exhibit a normal distribution, the Mann-Whitney U test was applied to investigate the difference between quantitative elastography measurements and testicular cancer. For qualitative data in elastography imaging regarding hard-soft differentiation, Doppler ultrasound imaging for blood flow presence-absence, and scrotal MR imaging for contrast enhancement presence-absence, as well as diffusion-weighted imaging for diffusion restriction presence-absence, Fisher’s Exact Test was applied. Additionally, due to the small number of patients undergoing MRI, a logistic regression model was developed to predict the likelihood of testicular cancer using parameters such as MRI contrast enhancement and diffusion restriction as independent variables. p-values were reported to evaluate whether the analysis results were statistically significant.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was used to evaluate the capacity of numerical parameters to predict malignancy status. The analysis includes the area under the curve (AUC), sensitivity, specificity, and optimal cut-off values to measure the ability of each parameter (quantitative elastography measurements, AFP levels, β-hCG levels, LDH levels, and lesion size) to differentiate malignancy. AUC, sensitivity, specificity, and cut-off point were calculated and presented. p-values were reported to evaluate whether the analysis results were statistically significant.

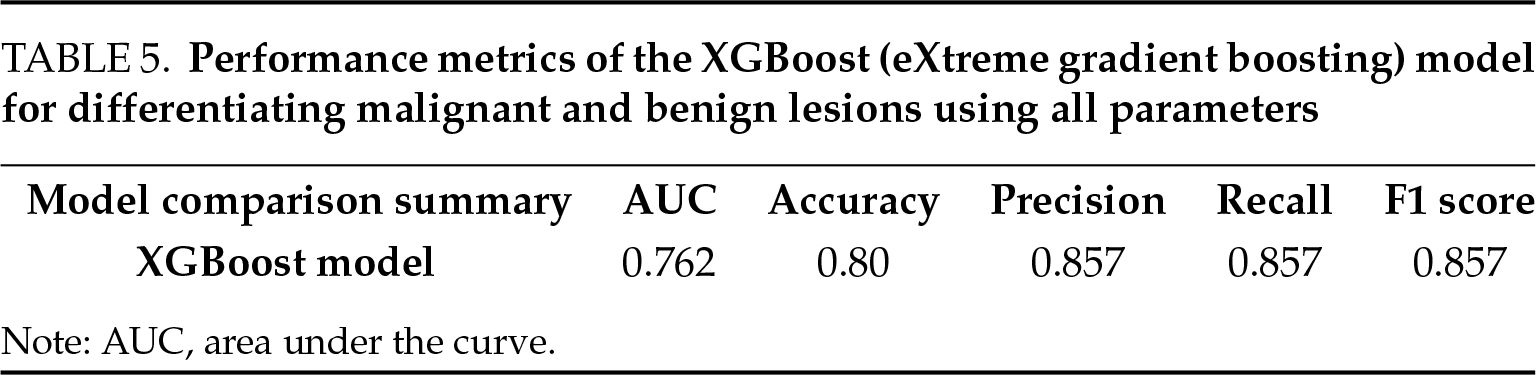

Finally, we aimed to develop a model that best differentiates between malignant and benign conditions in patients using all available data and to evaluate the performance of this model. A logistic regression test was applied to evaluate all variables collectively and to make a comparison. In the analysis, perfect separation was detected in the data. Ridge regression test was applied to overcome this. The performance of the model was calculated as low due to imbalances in the data set. Finally, malignant-benign discrimination performance was successfully analyzed with the XGBoost (eXtreme Gradient Boosting) model.

Statistical analyses were performed via AI-assisted statistical analysis tools. A p-value of <0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. Artificial intelligence (AI) tools were used in this study solely to facilitate the application of statistical tests to datasets organized in Microsoft Excel. These tools functioned in a supportive capacity, similar to conventional software such as SPSS or Python, by executing standard statistical analyses upon user request. AI was not involved in the study design, data interpretation, or decision-making processes. All the statistical methods applied adhere to established scientific guidelines and remain fully reproducible when traditional statistical software is used.

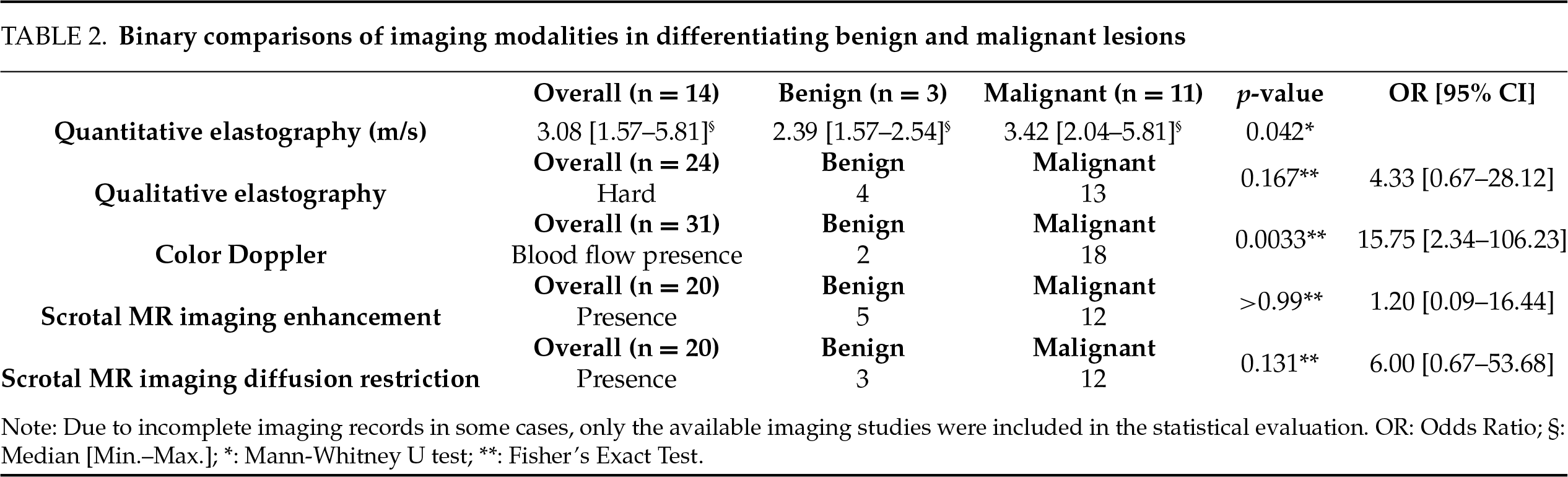

In comparative analyses, it was found that there was a statistically significant relationship between the quantitative elastography measurements of patients with detected masses in ultrasound examinations and testicular cancer (p = 0.042). When examining the relationship between qualitative elastography data (hard/soft) and testicular cancer, we observed that there was no statistically significant relationship (p > 0.05). These results indicate that when elastography measurements are conducted quantitatively, they are significant in predicting the risk of testicular cancer (Table 2). When examining other qualitative data, we observed a statistically significant positive correlation between vascularity in Doppler ultrasound imaging and testicular cancer (p = 0.0033). Blood supply on Doppler ultrasound imaging should be considered as an important factor in predicting the risk of malignancy. In scrotal MRI, there is no statistically significant relationship between contrast enhancement and testicular cancer (p > 0.05). When examining diffusion restriction in scrotal MRI, an Odds Ratio of six indicated a potential association between malignancy and benign conditions, suggesting that patients with diffusion restriction had a higher risk of malignancy. However, this relationship was not statistically significant (p > 0.05). Although some odds ratios demonstrated statistical significance, the wide confidence intervals—particularly in Doppler US and diffusion-weighted MRI—reflect the limitations of a small sample size and may reduce the precision of risk estimation (Table 2).

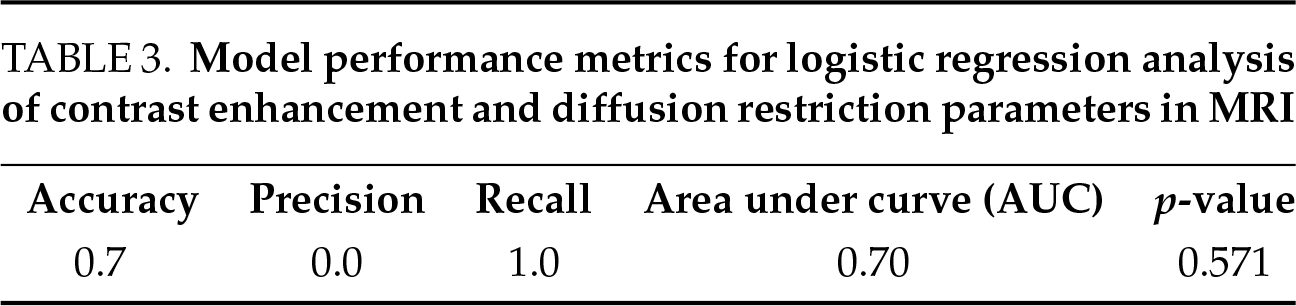

The logistic regression model created to evaluate the relationship between diffusion restriction and contrast enhancement in scrotal MRI for detecting malignancy was found to be statistically insignificant (p > 0.05). In addition, due to the small sample size, the model did not give sufficient results and failed in the optimization phase. Nevertheless, upon reviewing the results, it is evident that diffusion restriction in scrotal MRI has a stronger effect in distinguishing between malignancy and benignity, while contrast enhancement exhibits a weaker effect. The model indicates that scrotal MRI is highly effective in detecting malignant cases but is less effective in distinguishing benign cases (Table 3).

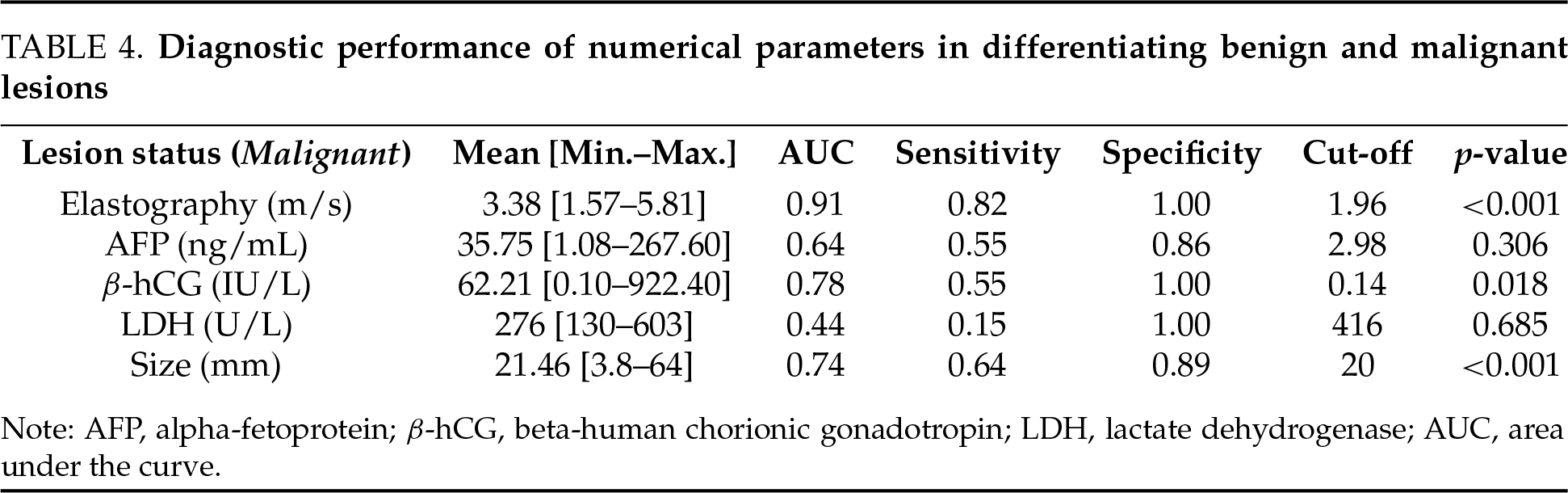

In quantitative elastography measurements, ROC analysis results were calculated as AUC 0.91 (p < 0.001), sensitivity as 0.82, specificity as 1.00, and cut-off value as 1.96 m/s. These findings support that quantitative elastography measurements possess a strong discriminative power in distinguishing between malignant and benign conditions (Table 4).

According to the results of the ROC analysis for laboratory parameters, the AUC for AFP was 0.64 (p = 0.306), with a sensitivity of 55%, specificity of 86%, and a cut-off value of 2.98 ng/mL. For the β-hCG value, the AUC was 0.78 (p = 0.018), with a sensitivity of 55%, specificity of 100%, and a cut-off value of 0.14 IU/L. For LDH value, AUC was 0.44 (p = 0.685), sensitivity was 15%, specificity was 100% and the cut-off value was 416 U/L. No statistical significance was found in values other than β-hCG (Table 4). Considering the performance metrics, it is seen that β-hCG has the highest specificity and positive predictive value (PPV) values in the diagnosis of testicular cancer. However, due to low sensitivity, some cancer patients with low β-hCG values are at risk of being overlooked. LDH has limited use value with low sensitivity. The high PPV of AFP indicates that the majority of patients with elevated AFP levels have cancer. However, due to its low negative predictive value (NPV), AFP may perform poorly in classifying patients without cancer. These results show that β-hCG performs best in distinguishing testicular cancer, AFP performs reasonably, but LDH is not very effective.

According to the results of the ROC analysis for the longest diameter of the lesion, the AUC was 0.74 (p < 0.001), the sensitivity was 0.64, the specificity was 0.89, and the cut-off value was 20 mm. We can state that there is a statistically significant relationship between lesion size (longest axis) and the likelihood of malignancy. We observe that the mean and median sizes of lesions in malignant cases are significantly larger than in benign cases. In other words, as the size increases, the likelihood of malignancy also appears to rise (Table 4).

In the multivariate analysis, we applied the XGBoost model to evaluate the effects of quantitative elastography, MRI findings, lesion size, and laboratory parameters on classifying lesions as malignant or benign (Table 5). In the evaluation using Precision and Recall metrics, the model demonstrated strong performance in detecting malignancy. 0.857 precision and 0.857 recall rates show that the model can accurately classify, especially malignant cases. The ROC curve showed that the model had a good decomposition capacity overall (AUC = 0.762). The Complexity Matrix results show that the performance of the model to distinguish benign cases is relatively lower, but it provides high accuracy in malignant cases. In the model, the imaging methods of scrotal Doppler ultrasound and lesion size emerged as the most significant variables in detecting malignancy. Elastography and MRI play an important role in the decision mechanism of the model. Laboratory parameters helped distinguish malignancy with higher accuracy. The combination of all imaging examinations, size, and laboratory parameters showed a strong performance in malignancy detection as expected.

In the assessment of testicular masses, our research shows that higher vascularity observed on Doppler ultrasound correlates significantly with testicular cancer. It seems more reasonable to use advanced imaging tests as problem solvers in situations where there is difficulty in characterization rather than using them in routine testicular imaging. Our study results also support the use of elastography as a first-line tool in cases where Doppler ultrasound easily detects the lesion but fails to characterize it effectively. Shear wave elastography, which can demonstrate tissue differences both quantitatively and qualitatively, contributes to the success in identifying malignancy potential and characterizing lesions with different features from the testicular parenchyma.12,13

Hematoma, ischemic changes, abscess, and fibrotic changes due to some infections may cause difficulties in diagnosis. In these cases, elastography can be useful in differential diagnosis when used together with conventional gray scale (b-mode) and Doppler US.14,15

Even with the assistance of elastography, there may be lesions for which a definitive differential diagnosis cannot be reached. In such cases, despite their limitations, tumor markers can be utilized for additional support. Low sensitivity rates and false-positive rates of traditional tumor markers are emphasized in similar studies.16,17 Although tumor markers such as β-hCG and AFP demonstrated some value in predicting malignancy, their diagnostic performance was inferior compared to imaging modalities, particularly elastography and Doppler ultrasound. These findings align with prior studies suggesting that biological markers should be considered complementary rather than primary tools in initial imaging-based differentiation (particularly elevated β-hCG and AFP levels).18,19

In cases where a clear distinction cannot be made, it should always be kept in mind that magnetic resonance imaging remains an option.20,21 In particular, it is emphasized in the literature that multiparametric scrotal MRI can help narrow diagnoses and determine more precise treatment strategies.22,23 In our study, rather than dynamic contrast-enhanced images, pre-contrast and post-contrast MRI images were available. Dynamic contrast-enhanced (DCE) sequences were not routinely acquired due to retrospective limitations. In our study, consistent with the information emphasized in the literature, diffusion-weighted MRI, categorized under functional MRI imaging, is particularly valuable compared to contrast-enhanced and conventional imaging.24,25 Our diffusion-weighted imaging findings align with studies suggesting that functional MRI techniques (such as diffusion tensor imaging, MR spectroscopy, diffusion imaging, and ADC histogram analysis) could open new horizons in the differentiation of testicular tumors and the determination of testis-sparing surgery.26–28 We agree that a multiparametric MRI protocol including DCE, ADC histogram analysis, and MR spectroscopy would significantly enhance lesion characterization.

The importance of imaging in the diagnosis of testicular cancer is well recognized.29,30 The machine learning-based XGBoost model, although exploratory due to the small dataset, highlighted Doppler vascularity and lesion size as dominant predictors of malignancy. Interestingly, while MRI findings contributed less prominently, the model still gained from the inclusion of diffusion restriction as a supportive feature. These results suggest that multimodal input significantly boosts predictive accuracy, warranting future validation with a larger dataset. We have demonstrated in our study how successful the combined use of all imaging methods and tumor markers is in the management of patients, even in cases where b-mode and color Doppler ultrasound leave uncertainty. The combination of all imaging methods can be utilized to classify patients into those who require biopsy or surgery and those who can be safely monitored.31–33

There are some limitations in our study. Firstly, the study had some natural limitations stemming from its retrospective design. Secondly, in our patient group, no hard-solid benign pathologies were found in the testicular parenchyma, and these patients could not be followed up in elastography imaging. Thirdly, one limitation of our study is the lack of interobserver variability assessment. Since a single radiologist performed all elastography examinations, interobserver agreement could not be evaluated. In future prospective studies, standardized protocols with quantitative elastography and predefined region of interest (ROI) placement should be adopted, and interobserver reliability metrics such as intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) should be reported. Finally the small number of patients with malignancy can be considered a limitation. Despite the relatively small sample size, our findings provide insight into how these modalities function in real clinical settings and encourage further prospective studies with larger cohorts. Larger studies with more patients could provide stronger statistical data to support our findings. Larger series are needed.

Elastography is a useful imaging modality for the differential diagnosis of testicular lesions, particularly through quantitative measurements. Especially in small lesions where Doppler fails to provide valuable information, the additional data offered by elastography further enhances its diagnostic value. In cases of uncertainty, MRI—particularly diffusion-weighted imaging—should always be considered an option for determining malignancy. However, our study results demonstrate that conventional MRI has limited ability to distinguish benign from malignant testicular masses.

When Doppler ultrasound, ultrasound elastography, diffusion MRI, and tumor markers are used together, a more effective diagnostic algorithm emerges. Based on our findings, the initial evaluation of testicular lesions should include gray-scale ultrasound for size measurement, Doppler ultrasound for vascularity assessment, elastography for stiffness evaluation, and diffusion-weighted MRI in indeterminate cases. In scenarios where differentiation remains inconclusive and the patient declines follow-up, the final step may involve surgical biopsy or orchiectomy.

Acknowledgement

Not applicable.

Funding Statement

Any funding did not support this study.

Author Contributions

Şeref Barbaros Arik and İnanç Güvenç designed the study; all authors conducted the study; Şeref Barbaros Arik collected and analyzed the data. Şeref Barbaros Arik participated in drafting the manuscript, and all authors contributed to critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors participated fully in the work, took public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or completeness of any part of the work were appropriately investigated and resolved. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study were available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval

This study was approved by The Yüksek İhtisas University, Turkey, Çankaya Non-invasive Investigation Ethics Committee (date: 04 May 2024, number: 2024-03-01) and was performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All eligible participants signed an informed consent form.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Kreydin EI, Barrisford GW, Feldman AS, Preston MA. Testicular cancer: what the radiologist needs to know. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2013;200(6):1215–1225. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

2. Heidenreich A, Paffenholz P, Pfister D. Regionalization of testis cancer care-is it necessary? Urol Clin North Am 2024;51(3):421–427. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

3. Marko J, Wolfman DJ, Aubin AL, Sesterhenn IA. Testicular seminoma and its mimics: from the radiologic pathology archives. Radiographics 2017;37(4):1085–1098. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

4. Fuller K. Diagnosis of testicular cancer. J Nurse Pract 2014;10(6):437–438. [Google Scholar]

5. Appelbaum L, Gaitini D, Dogra VS. Scrotal ultrasound in adults. Semin Ultrasound CT MR 2013;34(3):257–273. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

6. Expert Panel on Urological Imaging, Lyshchik A, Nikolaidis P et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® newly diagnosed palpable scrotal abnormality. J Am Coll Radiol 2022;19(5S):S114–S120. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2022.02.018. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Yu X, Zhao Q, Guo L. Diagnostic performance of contrast-enhanced ultrasound in testicular space-occupying lesions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad Radiol 2024;31(11):4509–4518. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

8. Wakileh GA, Ruf C, Heidenreich A et al. Contemporary options and future perspectives: three examples highlighting the challenges in testicular cancer imaging. World J Urol 2022;40(2):307–315. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

9. Pedersen MR, Sloth Osther PJ, Nissen HD, Vedsted P, Moller H, Rafaelsen SR. Elastography and diffusion-weighted MRI in patients with testicular microlithiasis, normal testicular tissue, and testicular cancer: an observational study. Acta Radiol 2019;60(4):535–541. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

10. Roy C, de Marini P, Labani A, Leyendecker P, Ohana M. Shear-wave elastography of the testicle: potential role of the stiffness value in various common testicular diseases. Clin Radiol 2020;75(7):560.e9–560.e17. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

11. Pedersen MR, Moller H, Osther PJS, Vedsted P, Holst R, Rafaelsen SR. Comparison of tissue stiffness using shear wave elastography in men with normal testicular tissue, testicular microlithiasis and testicular cancer. Ultrasound Int Open 2017;3(4):E150–E155. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

12. Goddi A, Sacchi A, Magistretti G, Almolla J, Salvadore M. Real-time tissue elastography for testicular lesion assessment. Eur Radiol 2012;22(4):721–730. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

13. Spiesecke P, Schmidt J, Peters R, Fischer T, Hamm B, Lerchbaumer MH. Assessment of quantitative microflow Vascular Index in testicular cancer. Eur J Radiol 2024;176(7):111513. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

14. Schroder C, Lock G, Schmidt C, Loning T, Dieckmann KP. Real-time elastography and contrast-enhanced ultrasonography in the evaluation of testicular masses: a comparative prospective study. Ultrasound Med Biol 2016;42(8):1807–1815. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

15. Aigner F, De Zordo T, Pallwein-Prettner L et al. Real-time sonoelastography for the evaluation of testicular lesions. Radiology 2012;263(2):584–589. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

16. Leão R, Ahmad AE, Hamilton RJ. Testicular cancer biomarkers: a role for precision medicine in testicular cancer. Clin Genitourin Cancer 2019;17(1):e176–e183. [Google Scholar]

17. Stevenson SM, Lowrance WT. Epidemiology and diagnosis of testis cancer. Urol Clin North Am 2015;42(3):269–275. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

18. Sykes J, Kaldany A, Jang TL. Current and evolving biomarkers in the diagnosis and management of testicular germ cell tumors. J Clin Med 2024;13(23):7448. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

19. Morini MA, Athanazio DA, Gallas LF et al. Biomarkers of prostate bladder and testicular cancers: current use in anatomic pathology and future directions. Surg Exp Pathol 2024;7(1):15. [Google Scholar]

20. Correas JM, Drakonakis E, Isidori AM et al. Update on ultrasound elastography: miscellanea. Prostate, testicle, musculo-skeletal. Eur J Radiol 2013;82(11):1904–1912. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

21. Benabdallah W, Loghmari A, Othmane MB, Ouahchi I, Hmida W, Jaidane M. Left paratesticular fibrous pseudotumor on the single testis and contribution of imaging in therapeutic management, a case report. Int J Surg Case Rep 2023;105(2):108077. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

22. Tsili AC, Sofikitis N, Stiliara E, Argyropoulou MI. MRI of testicular malignancies. Abdom Radiol 2019;44(3):1070–1082. [Google Scholar]

23. Tsili AC, Giannakis D, Sylakos A, Ntorkou A, Sofikitis N, Argyropoulou MI. MR imaging of scrotum. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am 2014;22(2):217–238, vi. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

24. Saidian A, Bagrodia A. Imaging techniques to differentiate benign testicular masses from germ cell tumors. Curr Urol Rep 2023;24(9):451–454. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

25. Tsili AC, Ntorkou A, Astrakas L et al. Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging in the characterization of testicular germ cell neoplasms: effect of ROI methods on apparent diffusion coefficient values and interobserver variability. Eur J Radiol 2017;89(Suppl. 6):1–6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

26. Tsili AC, Sofikitis N, Pappa O, Bougia CK, Argyropoulou MI. An overview of the role of multiparametric MRI in the investigation of testicular tumors. Cancers 2022;14(16):3912. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

27. Patel HD, Ramos M, Gupta M et al. Magnetic resonance imaging to differentiate the histology of testicular masses: a systematic review of studies with pathologic confirmation. Urology 2020;135:4–10. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

28. Zhang P, Min X, Feng Z et al. Value of intra-perinodular textural transition features from MRI in distinguishing between benign and malignant testicular lesions. Cancer Manag Res 2021;13:839–847. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

29. Expert Panel on Urological I, Schieda N, Oto A, Allen BC et al. ACR appropriateness criteria(R) Staging and surveillance of testicular cancer. J Am Coll Radiol 2022;19(5S):S194–S207. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

30. Pandit K, Puri D, Yuen K, Yodkhunnatham N, Meagher M, Bagrodia A. Optimal imaging techniques across the spectrum of testicular cancer. Urol Oncol 2025;43(3):150–155. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

31. Coursey Moreno C, Small WC, Camacho JC et al. Testicular tumors: what radiologists need to know—differential diagnosis, staging, and management. RadioGraphics 2015;35(2):400–415. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

32. Lewicki A, Freeman S, Jędrzejczyk M et al. Incidental findings and how to manage them: testis—a WFUMB position paper. Ultrasound Med Biol 2021;47(10):2787–2802. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

33. Feng Y, Feng Z, Wang L et al. Comparison and analysis of multiple machine learning models for discriminating benign and malignant testicular lesions based on magnetic resonance imaging radiomics. Front Med 2023;10:1279622. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools