Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Unbuckling: an answer to address cuff-related challenges in urethral instrumentation with an artificial urinary sphincter

Department of Urology, Duke University School of Medicine, 40 Duke Medicine Cir, Durham, NC 27710, USA

* Corresponding Author: Hasan Jhaveri. Email:

Canadian Journal of Urology 2025, 32(6), 597-603. https://doi.org/10.32604/cju.2025.068095

Received 21 May 2025; Accepted 04 August 2025; Issue published 30 December 2025

Abstract

Objectives: There is limited in vivo data on the maximum safe instrument size that can be passed through an artificial urinary sphincter (AUS) cuff. While 21 French instruments are generally safe with the commonly used 4.5 cm cuff, larger instruments or smaller cuffs may require unbuckling to avoid urethral erosion. This study aimed to identify if artificial urinary sphincter cuff ‘unbuckling’ affects device longevity and risk of erosion. Methods: A retrospective study of patients at a quaternary health system who underwent unbuckling was conducted. Using the Epic Clarity database and Duke Enterprise Data Unified Content Explorer (DEDUCE), we identified patients with artificial urinary sphincter (AUS) who were unbuckled during endoscopic procedures. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze patient demographics, device age at unbuckling, complications, and history of erosion, removal, or replacement. Results: Eight patients were identified with a prior history of AUS unbuckling. The average age was 68 years. 75% of patients had a history of pelvic radiation. The average number of unbuckling procedures per patient was 1.62. The median device age at first unbuckling was 2.60 years. Average time to reactivation was 22.25 days, and 6 of 8 patients had their device reactivated. Two patients developed erosions requiring device removal. Neither erosion occurred within 90 days of unbuckling. The mean age of devices at the time of removal was 6.85 years. Conclusions: AUS cuff unbuckling may serve as an alternative strategy when large-caliber urethral instrumentation is required. Studies with larger patient cohorts are required to further investigate the efficacy and ideal utilization of unbuckling.Keywords

The artificial urinary sphincter (AUS) is a mainstay treatment option for male patients with bothersome stress urinary incontinence (SUI). Between 1–10% of patients undergoing radical prostatectomy subsequently receive an AUS implant.1 In prostate cancer survivors with SUI, more than 90% of patients report satisfaction and an improved quality of life with their device.2,3 Though beneficial, prosthetic implantation is not without risk and complications. Patients receiving prosthetic implants often have comorbidities (e.g., history of radiation therapy and smoking) that predispose them to unique, long-term complications such as secondary malignancies (e.g., bladder cancer) and radiation cystitis.4,5 Surveillance and management of these consequences involve repetitive urethral instrumentation, which has been identified as an independent risk factor for cuff erosion and infection.6 Deactivation of the AUS device has been described as safe for when patients require intermittent catheterization, short term (<48 h) indwelling catheterization, or flexible cystoscopy (<17 Fr).7,8 Currently, there are no guidelines or formal recommendations from the device manufacturer on mitigating the risk of instrumentation with an AUS in place. An expert opinion in the Journal of Urology was recently published in November 2024, outlining best practice for rigid cystoscopy >21 Fr and higher risk catheterization (>48 h or >18 Fr).8 In these two clinical scenarios, the authors recommended a technique of device unbuckling (also known as uncoupling) through a small perineal incision over the device cuff at the time of the transurethral intervention.8 Hence, this study aimed to better understand the efficacy of device unbuckling on AUS device longevity and risk of erosion.

This was an analysis of a prospectively maintained AUS database at Duke University Health System comprising patients who have undergone AUS placement (Institutional Review Board Exemption of Duke University, IRB: Pro00117136). The Epic Clarity database was used to conduct a query of all patients who underwent AUS placement between 2003 and 2024. Patients were identified based on CPT (Current Procedural Terminology) codes associated with AUS procedures (53449, 53446, 53447). This cohort was then cross-referenced with those who had undergone endoscopic procedures (52000, 52001, 52224, 52234, 52235, 52240). This approach yielded a cohort of patients who had both an AUS and subsequent endoscopic intervention. These records were then manually reviewed by the research team to confirm eligibility. Patients were excluded if chart review revealed that device removal and replacement, rather than unbuckling, were performed at the time of the encounter. Additionally, patients were excluded if the query incorrectly identified patients who underwent endoscopic procedures prior to their AUS placement, rather than after.

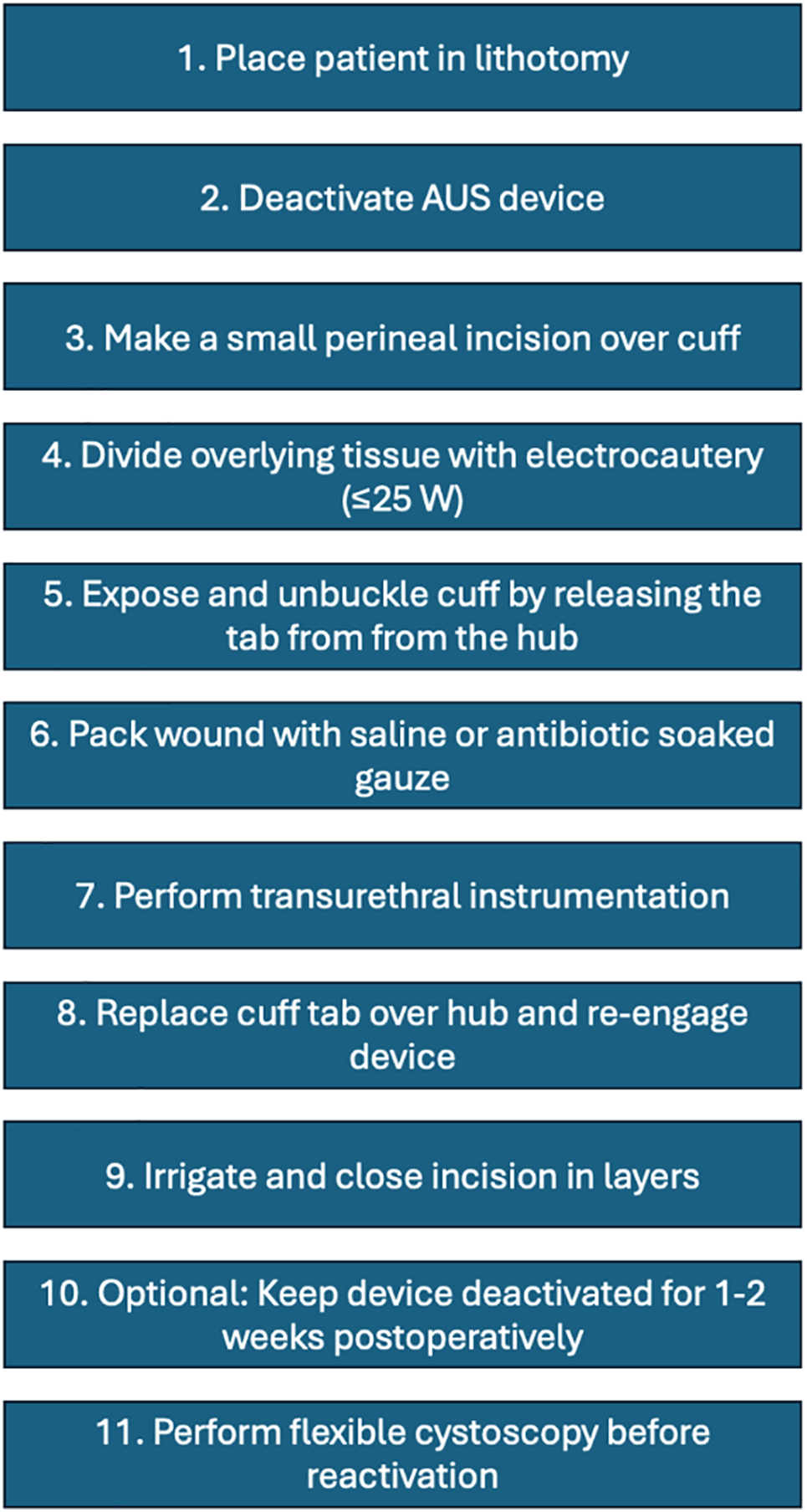

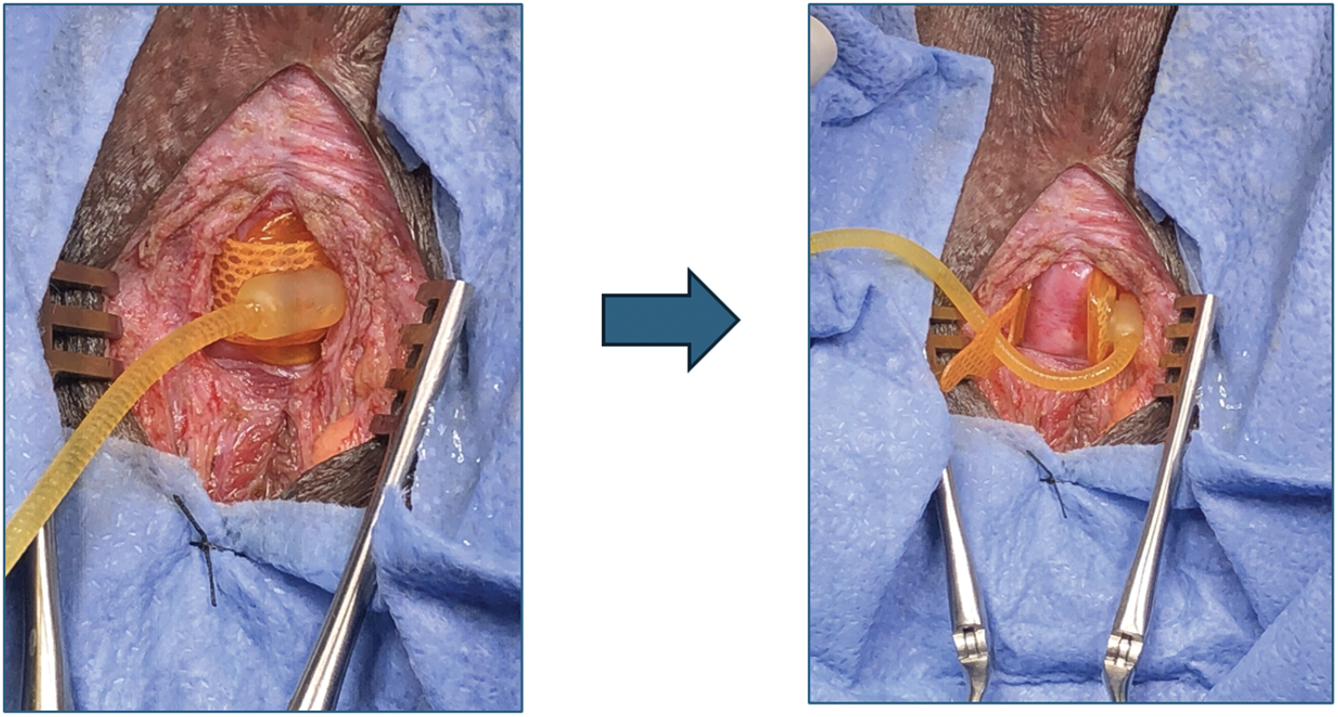

Patients with prior AUS placement who underwent unbuckling of the device during endoscopic instrumentation were included in the analysis. The procedure steps of device unbuckling are summarized in Figure 1. Step 5 is demonstrated in Figure 2. In steps 10 and 11, AUS reactivation timing was determined at the discretion of the operating surgeon based on intraoperative findings and patient-specific factors. Immediate reactivation was generally considered appropriate in patients without urethral fragility or those who underwent an atraumatic procedure without the need for prolonged catheterization. For other cases, particularly those involving pelvic radiation or radiation cystitis, reactivation was delayed by 3–6 weeks to allow for a recovery period. There were no cases of device malfunction or urethral compromise prior to reactivation.

FIGURE 1. Procedure steps for unbuckling an artificial urinary sphincter (AUS)

FIGURE 2. Expose and unbuckle the artificial urinary sphincter cuff by releasing the tab from the hub

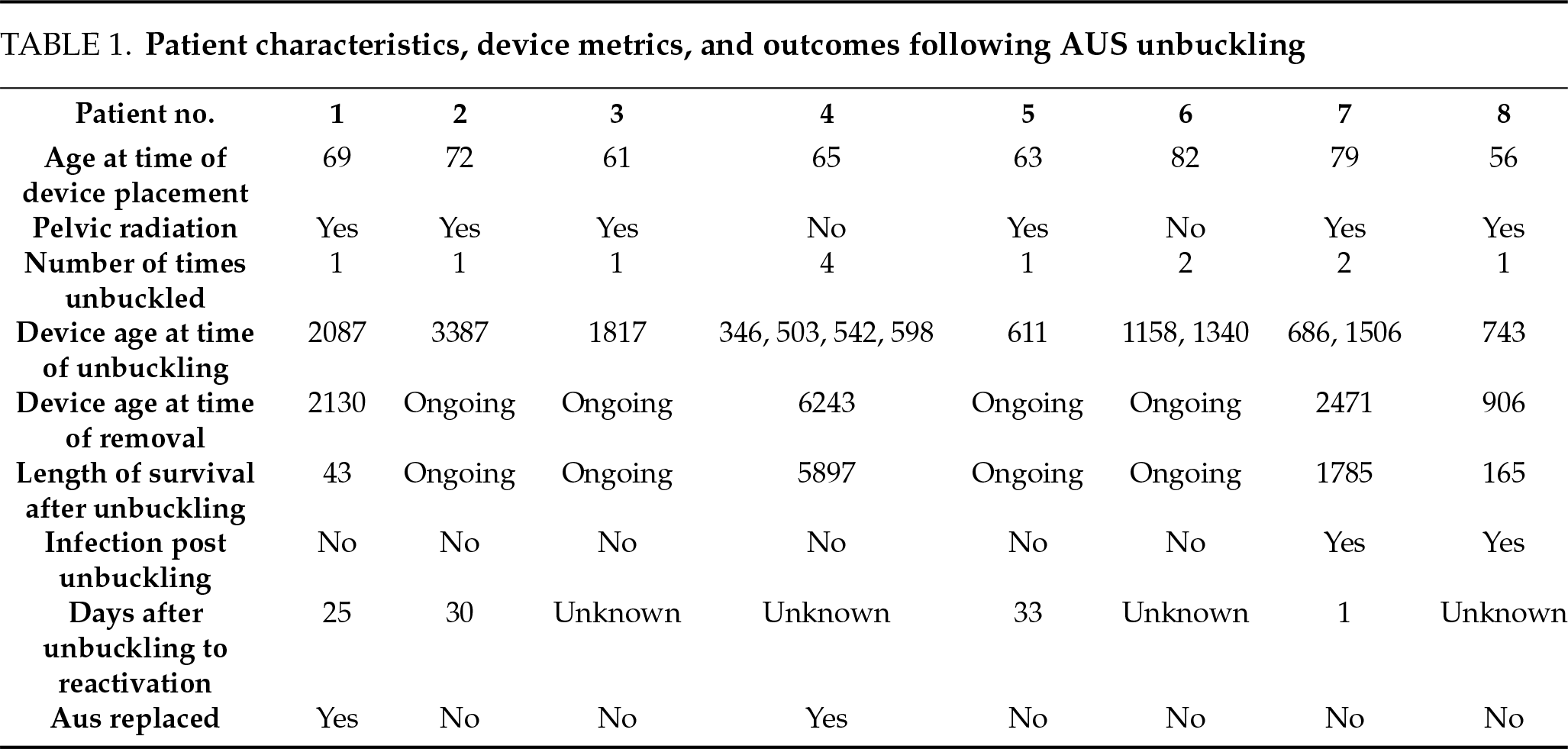

Patient demographic information, history of prior radiation, age of device at the time of unbuckling, and outcomes including erosion, removal, or replacement of the device were collected (Table 1). Complications were graded using the Clavien-Dindo scale. Device infection was defined as documented clinical evidence of device-related complications (i.e., erythema overlying device components, localized swelling or fluctuance, persistent localized pain, fever, wound dehiscence, new or worsening lower urinary tract symptoms) in the setting of a positive urine culture. Data was analyzed using descriptive statistics using Microsoft Excel (Redmond, WA, USA).

A total of 12 patients were examined, 8 of whom met the inclusion criteria. The mean age at AUS placement was 68.27 years (interquartile range [IQR]: 11.25 years). 6 of the 8 patients had a history of prior pelvic radiation.

The median number of unbuckling procedures per patient was 1 (IQR 1.0). The maximum number of unbuckling procedures in a patient was 4. Indications for unbuckling included: gross hematuria secondary to radiation cystitis (n = 3, 38%), transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT) (n = 2, 25%), bladder neck incision for treatment of contracture (n = 2, 25%), diagnostic cystoscopy with random bladder biopsies (n = 1, 13%), and UroLume stent encrustation requiring laser lithotripsy (n = 1, 13%).

The median device age at the time of the first unbuckling procedure was 2.60 years (950.5 days; IQR of 3.30 years, 1217.25 days). Following unbuckling, 6 of 8 patients underwent successful device reactivation, with a mean time to reactivation of 22.25 days.

Two patients had device-related complications requiring surgery for device removal due to erosion. One patient’s erosion occurred 4.89 years after first unbuckling (2.64 years after the second unbuckling) with a device age of 6.77 years at the time of removal. The other patient’s erosion occurred 0.45 years after unbuckling with a device age of 2.48 years. No infections occurred within 90 days of the unbuckling procedure. Two patients required AUS replacement due to incomplete coaptation, though no erosion was observed at the time of replacement. Among the removed devices, the mean age at the time of removal was 6.85 years (2501 days), with one device remaining in situ for 11.3 years after unbuckling.

In selected cases requiring large-caliber urethral instrumentation, AUS cuff unbuckling has shown promise as a safe and effective option in our limited experience. Cuff unbuckling has been suggested as a strategy for the management of artificial urinary sphincters in patients undergoing endoscopic instrumentation, particularly with instruments of large diameter.8

The two most challenging complications to manage with AUS devices are infection and urethral erosion. Published data on AUS outcomes show infection rates ranging from 0.46–7% and cuff erosion rates between 3.8–18%.9,10 In our cohort, two patients underwent device removal secondary to erosion. One patient’s erosion occurred 4.89 years after the unbuckling procedure, making the unbuckling event less likely the etiology of erosion. In a retrospective review by Findlay et al. aimed at evaluating the pathophysiology of erosion after AUS implantation of 1943 patients, the median time to erosion following placement was 1.6 years.10 Risk factors for erosion include coronary artery disease, hypertension, history of pelvic radiation, prior urethroplasty, and history of traumatic catheter placements.10 Therefore, we believe erosion is less likely secondary to technical errors during implantation or manipulation (such as unbuckling), and more likely secondary to factors that predispose a patient to having an unhealthy urethra. This is further supported by Findlay et al.’s review, as the authors found that, of the patients that underwent salvage AUS placement, 40% were explanted for subsequent erosion.10 In our study, the only other erosion occurred 0.45 years after unbuckling. However, this patient had significant risk factors for erosion, such as prior history of pelvic radiation, hypertension, and coronary artery disease secondary to cocaine abuse.

In our series, the two patients who developed urinary tract infections (UTIs) did so at least 90 days after unbuckling, suggesting that the unbuckling procedure itself is not related to the risk of developing an infection. The American Urological Association (AUA) best practice statement on urologic procedures and antibiotic prophylaxis suggests that urine culture should be tested to guide antibiotic stewardship.11 Based on these recommendations, most urologists attempt to sterilize urine preoperatively prior to AUS placement. In contrast, a study of 713 prosthetic urology cases showed no difference in infection rates after prosthetic surgery with or without preoperative urine cultures.12 Although the necessity of preoperative urine cultures and antibiotic treatment is a topic of contention amongst prosthetic urologists, the AUA guidelines recommend obtaining a preoperative urine culture prior to any cystoscopy procedure. Therefore, if a patient is undergoing AUS unbuckling to facilitate an endoscopic procedure, a culture is typically obtained.

With any subsequent endoscopic instrumentation, the risk of urethral erosion increases. Well-established risk factors for urethral erosion include prior radiation, multiple reconstructive procedures of the urethra, prior device infection, urethral instrumentation, or patients with a relatively small cuff size.13 In our cohort, 75% of patients had a prior history of radiation, which inherently places them at a higher risk of infection. The ‘immediate infection rate’ is essentially zero in our cohort, and the ‘delayed infection rate’, as defined as greater than 90 days, is favorable.

This study highlights the use of AUS cuff unbuckling as a management strategy for patients requiring urethral instrumentation with an AUS in situ. It has been shown that the functionality of the AUS decreases with time, and failure rates are nearly 25% at 5 years, 50% at 10 years, with a median duration of 7.5 years post-implantation.14,15 Among the removed devices in this study, the mean age at the time of removal was 6.85 years (2501 days), with one device remaining in situ for 11.3 years after unbuckling. These outcomes suggest a similar device longevity for AUS devices after unbuckling.

Heiner et al. examined the outcomes of 14 patients on bladder cancer surveillance who had AUS.5 At a median follow-up of 7.2 years, there was a total of 8 primary and one secondary device failure.5 One patient experienced an iatrogenic erosion related to urethral manipulation. The authors suggest that bladder cancer surveillance and treatment with an AUS confer minimal risk.5 However, all surveillance was conducted using a 17F flexible cystoscopy. In events where larger caliber instrumentation is indicated (e.g., cystoscopy for clot evacuation, transurethral resection of bladder tumors), unbuckling may prove protective of urethral integrity.

It is important to note that not all urologists are high-volume implanters. In 2005, an analysis on state and regional variation of AUS sales demonstrated that 34% of all national sales of AUS units were represented by the sales of 5 states.1 Furthermore, one AUS unit was purchased for every three urologists.1 This trend suggests that, more and more, this has become a procedure performed at tertiary referral centers and less in the community. While many urologists may not adopt this approach and proceed with any size resectoscope through a deactivated cuff, our series brings attention to this intervention as an option. Adopting this approach could lead to more referrals to centers of excellence where it is widely accepted, potentially increasing expert-level care and reducing unnecessary morbidity from cuff erosion. Non-high-volume implanters may prefer to refer these patients rather than attempt unbuckling themselves, given the technical nuances and the potential risks of improper handling.

Lastly, it is important to highlight that the potential added benefit from this approach is not solely gained from decreasing intraoperative trauma to the AUS cuff. The aftercare of certain procedures (e.g., large-bore catheter, continuous bladder irrigation) is probably safer in an unbuckled cuff.

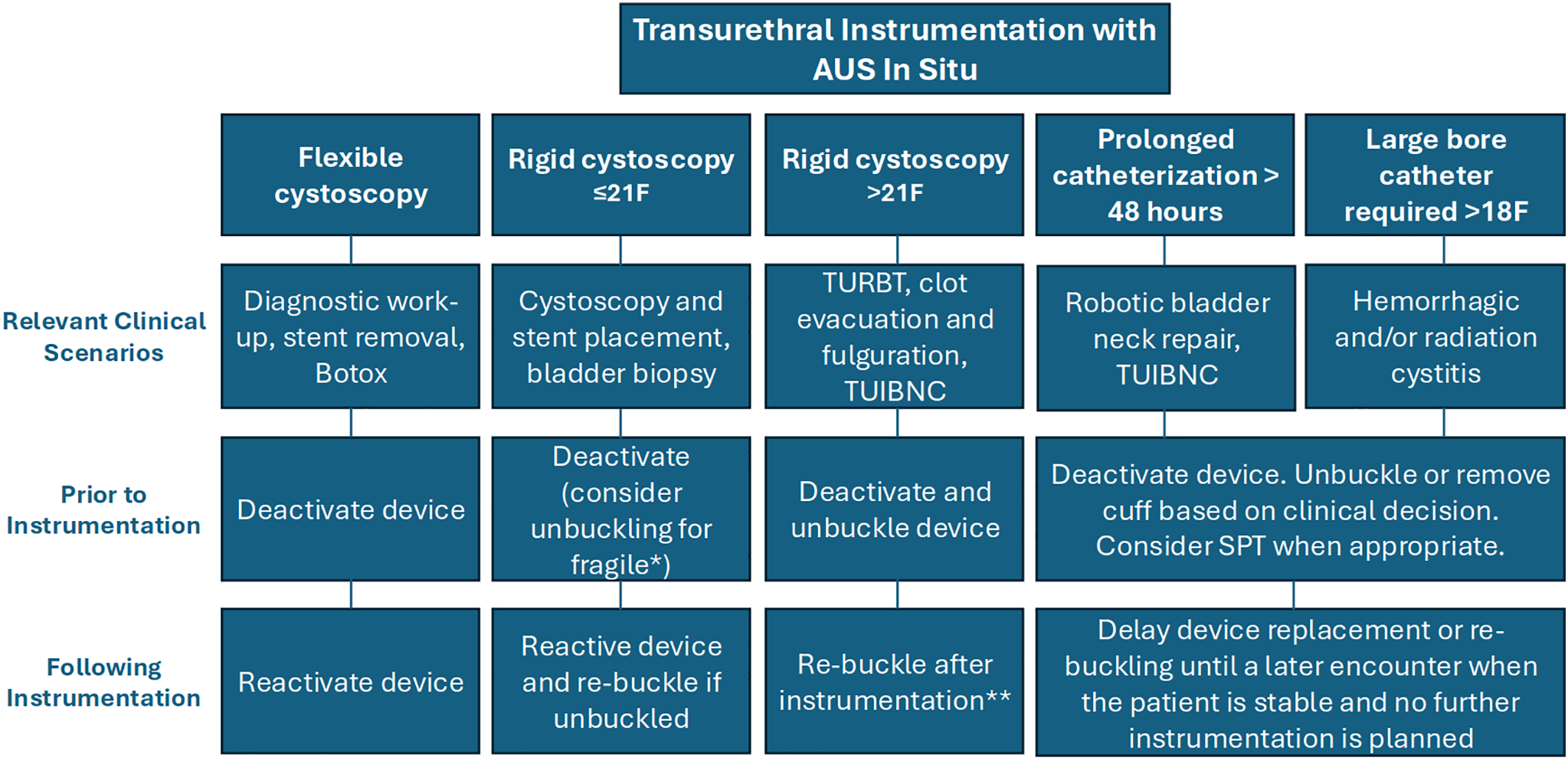

The present study is the first of its kind to describe the outcomes of cuff unbuckling among AUS patients undergoing endoscopic procedures. This series suggests that AUS cuff unbuckling could be a strategy to manage transurethral instrumentation for properly selected AUS patients. Based on our findings, we propose a decision-making flowchart tailored to unique clinical scenarios that can help guide management (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3. A flow chart for unique clinical scenarios in transurethral instrumentation with artificial urinary sphincter (AUS) in situ. Note: *Evidence of compromised urethral integrity due to prior erosion, radiation, androgen deprivation, vascular disease, or a complex surgical history. **Consider delaying re-buckling if further instrumentation is planned. Consider short-term deactivation to allow urethral rest during the recovery period (1–2 weeks)

Our study is not without limitations. Firstly, this is a limited retrospective series of 8 patients. This study included patients managed by high-volume implanters at a quaternary care center, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Our claims-based search function relies on accurate coding and documentation. However, the absence of a dedicated International Classification of Diseases (ICD) procedural code for AUS unbuckling likely limited our search yield, and it is probable that some unbuckling procedures were not captured. Ultimately, multi-institutional prospective studies with larger patient cohorts should be conducted to further demonstrate the efficacy and safety of this surgical technique.

The results from our series suggest that AUS cuff unbuckling may be a reasonable option in select patients where urethral instrumentation poses a significant risk. While limited by sample size, our experience demonstrates the feasibility and safety of this technique as an alternative approach, particularly when compared against the devastating potential for urethral erosion, device loss, and immediate return of profound stress urinary incontinence.

Acknowledgement

Not applicable.

Funding Statement

The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Study conception and design: Hasan Jhaveri, Brent Nose, Jordan Foreman, Aaron C. Lentz; Data collection: Hasan Jhaveri, Brent Nose; Analysis and interpretation of results: Hasan Jhaveri, Mariella Martinez-Rivera, Aaron C. Lentz; Draft manuscript preparation: Hasan Jhaveri, Mariella Martinez-Rivera, Jordan Foreman, Aaron C. Lentz. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Hasan Jhaveri, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval

The ethical review of this study was exempted by the Institutional Review Board of Duke University. IRB: #Pro00117136. Category 4: Secondary research for which consent is not required.

Informed Consent

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

Aaron C. Lentz, MD, FACS: Speaker, consultant, and preceptor for Coloplast Corporation and Boston Scientific Corporation. Guest editor for Translational Andrology and Urology series on “Genitourinary Prosthesis Infection”.

References

1. Reynolds WS, Patel R, Msezane L, Lucioni A, Rapp DE, Bales GT. Current use of artificial urinary sphincters in the United States. J Urol 2007;178(2):578–583. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2007.03.146. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Dani H, Meeks W, Weiss C, Fang R, Cohen AJ. Patterns of surgical management of male stress urinary incontinence: data from the AUA quality registry. Urol Pract 2023;10(1):67–72. doi:10.1097/UPJ.0000000000000359. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Van der Aa F, Drake MJ, Kasyan GR, Petrolekas A, Cornu JN. The artificial urinary sphincter after a quarter of a century: a critical systematic review of its use in male non-neurogenic incontinence. Eur Urol 2013;63(4):681–689. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2012.11.034. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Rivera ME, Linder BJ, Ziegelmann MJ, Viers BR, Rangel LJ, Elliott DS. The impact of prior radiation therapy on artificial urinary sphincter device survival. J Urol 2016;195(4):1033–1037. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2015.10.119. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Heiner SM, Viers BR, Rivera ME, Linder BJ, Elliott DS. What is the fate of artificial urinary sphincters among men undergoing repetitive bladder cancer treatment? Investig Clin Urol 2018;59(1):44–48. doi:10.4111/icu.2018.59.1.44. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Seideman CA, Zhao LC, Hudak SJ, Mierzwiak J, Adibi M, Morey AF. Is prolonged catheterization a risk factor for artificial urinary sphincter cuff erosion? Urology 2013;82(4):943–946. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2013.06.044. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Mulholland TL, Diokno AC. The artificial urinary sphincter and urinary catheterization: what every physician should know and do to avoid serious complications. Int Urol Nephrol 2004;36(2):197–201. doi:10.1023/b:urol.0000034660.54482.d1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Ivan SJ, Cohn JA, Loh-Doyle JC, Lentz AC, Simhan J. Cuff conundrums: best practice recommendations for urethral instrumentation with an artificial urinary sphincter in place. J Urol 2025;213(3):271–273. doi:10.1097/ju.0000000000004312. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Montague DK. Artificial urinary sphincter: long-term results and patient satisfaction. Adv Urol 2012;2012(3):835290. doi:10.1155/2012/835290. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Findlay BL, Fadel A, Pence ST, Britton CJ, Linder BJ, Elliott DS. Natural history of artificial urinary sphincter erosion: long-term lower urinary tract outcomes and incontinence management. Urology 2024;193:204–210. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2024.06.054. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Mangioni D, Rocchini L, Bandera A, Montanari E. Re: best practice statement on urologic procedures and antimicrobial prophylaxis. J Urol 2020;203(6):1214–1215. doi:10.1097/JU.0000000000000789. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Kavoussi NL, Viers BR, Pagilara TJ et al. Are urine cultures necessary prior to urologic prosthetic surgery? Sex Med Rev 2018;6(1):157–161. doi:10.1016/j.sxmr.2017.03.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Heah NH, Tan RBW. Management of urethral atrophy after implantation of artificial urinary sphincter: what are the weaknesses? Asian J Androl 2020;22(1):60–63. doi:10.4103/aja.aja_110_19. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Viers BR, Linder BJ, Rivera ME, Rangel LJ, Ziegelmann MJ, Elliott DS. Long-term quality of life and functional outcomes among primary and secondary artificial urinary sphincter implantations in men with stress urinary incontinence. J Urol 2016;196(3):838–843. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2016.03.076. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Krughoff K, Peterson AC. Clinical and urodynamic determinants of earlier time to failure for the artificial urinary sphincter. Urology 2023;176:200–205. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2023.03.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools