Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Deep Learning-Based Lip-Reading for Vocal Impaired Patient Rehabilitation

1 Management and Production Engineering, Polytechnic University of Turin, C.so Duca degli Abruzzi 24, Torino, 10129, Italy

2 Biomedical Engineering, Polytechnic University of Turin, C.so Duca degli Abruzzi 24, Torino, 10129, Italy

* Corresponding Author: Chiara Innocente. Email:

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 143(2), 1355-1379. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.063186

Received 07 January 2025; Accepted 28 March 2025; Issue published 30 May 2025

Abstract

Lip-reading technology, based on visual speech decoding and automatic speech recognition, offers a promising solution to overcoming communication barriers, particularly for individuals with temporary or permanent speech impairments. However, most Visual Speech Recognition (VSR) research has primarily focused on the English language and general-purpose applications, limiting its practical applicability in medical and rehabilitative settings. This study introduces the first Deep Learning (DL) based lip-reading system for the Italian language designed to assist individuals with vocal cord pathologies in daily interactions, facilitating communication for patients recovering from vocal cord surgeries, whether temporarily or permanently impaired. To ensure relevance and effectiveness in real-world scenarios, a carefully curated vocabulary of twenty-five Italian words was selected, encompassing critical semantic fields such as Needs, Questions, Answers, Emergencies, Greetings, Requests, and Body Parts. These words were chosen to address both essential daily communication and urgent medical assistance requests. Our approach combines a spatiotemporal Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) with a bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM) recurrent network, and a Connectionist Temporal Classification (CTC) loss function to recognize individual words, without requiring predefined words boundaries. The experimental results demonstrate the system’s robust performance in recognizing target words, reaching an average accuracy of 96.4% in individual word recognition, suggesting that the system is particularly well-suited for offering support in constrained clinical and caregiving environments, where quick and reliable communication is critical. In conclusion, the study highlights the importance of developing language-specific, application-driven VSR solutions, particularly for non-English languages with limited linguistic resources. By bridging the gap between deep learning-based lip-reading and real-world clinical needs, this research advances assistive communication technologies, paving the way for more inclusive and medically relevant applications of VSR in rehabilitation and healthcare.Keywords

Vocal cord paralysis and related conditions, such as paresis or trauma-induced impairments, can severely affect a person’s ability to communicate effectively [1]. These impairments can result from various causes, including surgical interventions, neurological disorders, trauma, or infections, that interfere with the vocal cords’ ability to vibrate properly, making it challenging for affected individuals to produce clear speech sounds [2]. Particularly, individuals recovering from surgeries, such as thyroidectomy, cardiac surgeries, or cancer-related procedures affecting the vocal cords, often face temporary or permanent speech impairments [3]. For those patients, this medical condition can lead to difficulties in expressing urgent needs, engaging in everyday conversations, and establishing social relationships. Such communication barriers often lead to social isolation, and emotional distress, thereby negatively affecting their quality of life, particularly in environments like caregiving or clinical settings where quick and efficient interactions are required [4].

The rehabilitation process for those patients typically involves both medical and communicative therapies. Traditional methods to support these individuals often rely on gestures or written communication, which can be slow and cumbersome [5]. Lip reading, the ability to interpret spoken words through the visual observation of lip movements, has gained significant interest in this field due to its potential applications [6]. Leveraging this capability, advancements in Visual Speech Recognition (VSR) systems now enable automated interpretation of lip movements, as these tools offer alternative communication channels, providing vital assistance in situations where vocal communication is limited or absent. Specifically, VSR systems enhance accessibility for those dealing with vocal impairments, offering a scalable solution to assist them by providing reliable, real-time communication support, bridging the gap between traditional therapeutic approaches and modern technological solutions [7]. Moreover, VSR, which is inherently challenging due to the visual similarity of different phonemes (homophenes), can also be employed to develop systems that assist in noisy environments [8], improve automatic VSR [9], and provide accessibility solutions for hearing-impaired patients, particularly in emergencies [10]. Furthermore, VSR applications extend to biological authentication, where lip-reading is used as an effective authentication method because of its uniqueness from person to person [11,12].

The development of lip-reading technologies has seen a significant shift towards the use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) [13]. Machine Learning (ML) and Deep Learning (DL) techniques, in particular, have paved the way for breakthroughs in tasks traditionally reliant on human perception, such as image classification [14], gesture recognition [15], emotion analysis [16], and speech processing [17].

Historically, lip reading relied on traditional ML approaches and feature engineering to extract relevant visual features from video frames showing mouth movements [18]. These methods, however, are often limited by the complexity of human lip movements and the availability of labeled data. To overcome this issue Yeo et al. [19] developed a novel method for enhancing VSR performance by using automated labeling techniques to generate large-scale labeled datasets for languages with limited resources, such as French, Spanish, and Portuguese. By comparing models trained on automatically generated labels with those trained on human-annotated labels, the study achieves comparable VSR performance without relying on manual annotations. The integration of large-scale datasets with AI algorithms has been a driving force behind this progress, enabling systems to learn complex patterns and make predictions with remarkable accuracy [20]. In the realm of speech and visual recognition, AI has enhanced the performance of applications like automated transcription and lip-reading systems [21], by extracting significant features from lip movements and categorizing them into textual content.

Modern lip-reading and VSR systems now extensively rely on DL. Methodologies derived from object detection have been progressively adopted in the lip-reading domain, particularly for accurately localizing and extracting the mouth region as the primary Region of Interest (ROI). Efficient and precise ROI extraction is crucial in VSR, as irrelevant facial regions or background noise can introduce variability that negatively affects recognition accuracy.

Architectures such as YOLOv3-Tiny [22], originally designed for real-time object detection tasks involving multiple object categories in complex scenes, have been successfully repurposed to detect and track lip movements frame by frame. This allows the system to dynamically adapt to variations in head pose, scale, and position, ensuring that the most informative features are consistently captured during speech articulation. The transfer of object detection strategies to VSR tasks is particularly advantageous due to the inherent requirements of real-time processing and low-latency inference in practical applications, such as assistive communication devices or mobile healthcare solutions. Beyond localization, object detection techniques also contribute to temporal consistency across video frames by stabilizing the ROI and enhancing the continuity of feature extraction, which is essential for capturing the nuanced dynamics of lip movements over time.

The frequent use of DL architectures, such as Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), often in hybrid configurations to increase feature extraction and classification accuracy, is recurrent in the literature as these models work especially well in multimodal fusion, which combines visual and audio information to improve recognition, especially in difficult acoustic settings. A notable example of this is the LipNet [23], which uses a combination of 3D convolutions followed by bidirectional Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) layers to achieve end-to-end sentence-level lip reading, significantly improving over previous methods that focused on word-level or phoneme-level recognition. Among researchers that used this approach, Prashanth et al. [24] also decoded spoken text from video sequences of lip movements using 3D CNNs and bidirectional LSTMs, achieving a character error rate of 1.54% and a word error rate of 7.96%. Similarly, Jeon et al. [25] introduced a cloud-based open speech architecture that incorporates lip-reading for noise-robust automatic speech recognition. Their end-to-end lip-reading model integrated several CNN architectures, including 3D CNNs and multilayer 3D CNNs, to enhance the recognition accuracy of open cloud-based Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) like Google, Microsoft, and Amazon, thus highlighting the potential for improving cloud-based speech recognition systems in environments with varying levels of noise. Matsui et al. [26] also use a LipNet-based lip-reading system for speech enhancement in laryngectomees, using Variational Autoencoders (VAE) and CNNs to recognize a small vocabulary of words. This approach, though limited in vocabulary, demonstrates the viability of DL models in highly specialized applications, such as providing speech enhancement for individuals who have lost their ability to speak due to surgery.

Recent advancements in the field of VSR have increasingly focused on improving the extraction of spatiotemporal features through the integration of lightweight architectures and novel optimization techniques. For instance, Wang et al. [27] introduced Mini-3DCvT, a compact model combining 3D convolutions with visual transformers to efficiently capture local and global features from continuous video frames while reducing computational complexity through weight sharing and knowledge distillation strategies. Similarly, Ryumin et al. [28] proposed an audio-visual speech and gesture recognition framework using mobile device sensors, introducing fine-tuning strategies for multi-modal fusion at feature and model levels to enhance speech recognition in noisy environments, highlighting the growing synergy between lip-reading and gesture recognition in human-computer interaction contexts. Further innovations in speaker adaptation have been presented by Kim et al. [29], who developed prompt-tuning techniques for adapting pre-trained VSR models to unseen speakers with minimal data, using learnable prompts applied across CNN and Transformer layers, thereby improving generalization while preserving model parameters.

The integration of both auditory and visual modalities to enhance recognition performance in noisy environments has been a major focus in the audiovisual speech recognition (AVSR) literature, and several papers explore this approach using multimodal fusion techniques to improve robustness and accuracy in adverse conditions [30]. A Multi-Head Visual-Audio Memory model is presented by Kim et al. [31] in order to overcome the problems associated with homophones. By using audio-visual datasets to supplement visual information, the system improves lip-reading accuracy by enhancing its recognition of ambiguous lip movements and homophone differentiation. He et al. [32] proposed a GAN-based multimodal AVSR architecture, combining two-stream networks for audio and visual data. This architecture improves both energy efficiency and classification accuracy, making it suitable for Internet of Things applications, for example in augmented reality environments, demonstrating how lip-reading and visual cues can be combined to improve speech recognition in immersive settings. Li et al. [33] also emphasized the integration of DL for VSR in the metaverse, a virtual, interconnected digital space where users can interact, work, play, and socialize in real-time, often through immersive technologies like virtual and augmented reality. In order to recognize speech from lip movements, the authors employ Densely Connected Temporal Convolutional Networks (DC-TCN), ShuffleNet, and 3D CNNs to record both visual and temporal features. Their research, which was based on the GRID and Wild datasets, produced remarkable results, with accuracy rates of 98.8% and 99.5%, respectively. This demonstrates how deep learning can facilitate immersive, real-time communication in virtual settings. Differently, Gao et al. [34] explore acoustic-based silent speech interfaces, with their EchoWhisper system using the micro-Doppler effect to capture mouth and tongue movements. By processing beamformed echoes through dual microphones on a smartphone, EchoWhisper enables speech recognition without requiring vocalization, achieving a word error rate of 8.33%.

In recent years, research on automatic lip reading has made significant progress with the development of benchmark datasets that provide standardized references for training and model evaluation. Among the most widely used, Lip Reading in the Wild (LRW) is one of the first large-scale datasets for lip reading based on isolated words. Presented by Chung et al. [35], LRW includes over 500,000 video samples extracted from television broadcasts, covering 500 English words spoken by different speakers under uncontrolled conditions. In addition to LRW, later datasets, such as LRS2 [36] and LRS3 [37] have expanded the scope of research to include full sentences and continuous speech, enabling the development of more sophisticated models. LRS2, for example, includes about 140,000 sentences from television content and is an intermediate step between isolated word recognition and full sentence recognition, while LRS3, on the other hand, is an even larger dataset containing 150,000 video segments from Technology, Entertainment, Design (TED) Talks, allowing the problem of lip recognition to be addressed in more realistic and variable contexts. Different model architectures have been proposed and tested on these databases, further improving lip reading performance. For example, the SyncVSR model [38] introduced an end-to-end learning framework that uses quantized audio for crossmodal supervision at the frame level, synchronizing visual representation with acoustic data. Wand et al. [39] suggested a deep model technique in which they directly extracted features from the ROI pixels using fully connected layers and modeled the sequence temporal dynamics using the architecture of LSTM. Other approaches use a different architecture, combining DResNet-18 with a bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory network (BiLSTM) with integration of Vosk and MediaPipe to emphasize preprocessing and data augmentation techniques to improve model robustness [40] or a 3D convolutional network with ResNet-18 in the initial stage and a temporal model in the subsequent stage, using the mouth region of interest as input [41]. Recent advancements also include the work of Ogri et al. [42], who proposed a novel lip-reading classification approach based on DL, integrating optimized quaternion Meixner moments through the Grey Wolf Optimization (GWO) algorithm, achieving improved feature extraction and classification accuracy for VSR tasks. This method demonstrates the potential of optimization algorithms in enhancing feature representations for lip-reading, complementing traditional DL architectures. Additionally, techniques such as data augmentation, self-distillation, and word boundary indicators are applied to enhance recognition accuracy. Another significant approach is DC-TCN, which integrates dense connections into temporal convolutional networks to capture more robust temporal features, improving recognition accuracy on datasets such as LRW and LRW-1000 [43]. In addition, techniques such as visual attention and the use of phonetic subunits have been explored to address the inherent ambiguities of lip-reading. For example, the use of attention mechanisms to aggregate visual representations of speech and the adoption of phonetic sub-units allowed better modeling of task ambiguities, improving performance on benchmarks such as LRS2 and LRS3 [44].

Several studies have also contributed non-English datasets and methodologies to expand lip-reading capabilities beyond the English language, addressing a significant gap in the field by exploring linguistic diversity and developing systems adaptable to various cultural and linguistic contexts. For example, a mobile device-based lip-reading system to identify Japanese vowel sequences created especially for laryngectomees is proposed by Nakahara et al. [22], showing how flexible lip-reading models like YOLOv3-Tiny can be to meet the needs of different users even with small datasets. In order to train with little data, the system incorporates Variational Autoencoders (VAE), achieving a recognition accuracy of 65% for word recognition, with room for improvement through user-specific customization. Instead, Arakane et al. [45] concentrate on Japanese sentence-level lip-reading and introduce a Conformer-based model, challenging the dominance of English-based datasets and highlighting the importance of adapting lip-reading systems to different languages and sentence structures. A similar procedure has also been followed by Pourmousa et al. [46] to overcome the absence of Turkish lip-reading datasets. Their model’s respectable recognition accuracy for adjectives, nouns, and verbs, despite its small size, highlights, again, the importance of creating non-English datasets to enhance lip-reading abilities for a variety of languages. In a different way, Yu et al. [47] emphasize the importance of using AVSR to preserve endangered languages like Tujia. Their work demonstrates the value of audio-visual integration in enhancing language recognition, which is crucial for both cultural preservation and the development of robust speech recognition systems in underrepresented languages.

Despite the advances, several challenges remain. As documented in recent literature, the performances of automatic lip-reading systems show significant variation depending on the datasets used and the architectures of the implemented models [48]. Across various databases such as AVLetters, CUAVE, GRID, OuluVS2, LRW, and BBC-LRS2, reported accuracies range from relatively modest values to very high results, indicative of substantial progress achieved by Deep Neural Networks (DNNs). The results indicate that DNN-based architectures have significantly improved lip-reading performance compared to traditional methods, with accuracy gains that can exceed 20% compared to more conventional systems [21]. One significant issue is the inherent ambiguity in lip movements for different phonemes, which can impact accuracy [49]. Additionally, while many models show promise in controlled environments, their performance can degrade in more varied real-world settings, such as in clinical or caregiving contexts [50]. Effective communication is crucial in healthcare settings, particularly for patients recovering from surgical interventions affecting speech, who often encounter significant challenges in expressing basic needs, discomfort, or urgent medical concerns. The inability to communicate efficiently can result in heightened frustration, delayed medical responses, and a negative impact on overall well-being, underscoring the urgent need for alternative assistive communication technologies. Addressing these limitations is essential to developing usable and responsive VSR systems tailored to real-world medical needs. Another crucial challenge is the language dependency of visual speech recognition systems. The diversity of languages and accents poses a significant hurdle for these technologies. Different languages have unique phonetic structures and lip movements, making it difficult to create a universal lip-reading system. Moreover, even within the same language, variations in accents and dialects can impact the accuracy of recognition. This challenge necessitates the development of language-specific models and diverse training datasets to improve system generalizability and performance across different linguistic contexts.

Most recent studies remain focused on large-scale, language-specific datasets (primarily in English) and often rely on high-performance computing resources, limiting their applicability in real-time, resource-constrained environments such as clinical settings. Additionally, while multimodal fusion has enhanced recognition in noisy contexts, limited attention has been given to supporting patients with speech impairments in emergency scenarios, particularly in underrepresented languages like Italian. In contrast to prior work, our study addresses these gaps by introducing a custom Italian-language dataset tailored for medical communication, employing a lightweight model architecture optimized for deployment on low-cost hardware. Furthermore, we prioritize the system’s robustness in real-world healthcare environments, where articulation variability and device constraints present unique challenges not fully explored in existing literature.

This study aims to address these challenges by bridging the gap between DL-based VSR and its practical application in clinical rehabilitation, focusing on the recognition of a set of common Italian words essential for basic communication, explicitly designed for individuals recovering vocal abilities after surgical interventions, whether the vocal impairment is temporary or permanent. Unlike general-purpose VSR systems, which often prioritize sentence-level recognition, this study focuses on the recognition of individual words. This choice enhances efficiency, accessibility, and real-time usability, acknowledging the significant communication barriers patients face during recovery. The need to accelerate interaction and reduce cognitive load–especially for individuals already experiencing emotional or physical distress–is a key motivation behind this approach. The carefully curated vocabulary consists of twenty-five Italian terms drawn from semantic fields such as Needs, Questions, Answers, Emergencies, Greetings, Requests, and Body Parts. These terms were selected as high-frequency, contextually relevant words, to address immediate and essential communication needs, enabling recovering patients to quickly convey critical information or requests in caregiving and clinical settings. This capability is crucial in medical emergencies where a patient may need to quickly communicate acute pain (e.g., “pain”), call for assistance (e.g., “help”), or specify affected body parts (e.g., “head”, “chest”) to healthcare providers. Additionally, the ability to ask for information (e.g., “how”, “why”) or respond to medical staff with simple answers (e.g., “yes”, “no”, “bad”, “good”) is essential for effective cooperation and timely care. This focus not only accelerates the communication process, and ensures that patients can quickly convey essential information, facilitating timely and effective caregiving in urgent medical scenarios but also empowers users by providing them with a practical tool tailored to their specific circumstances, enhancing patient autonomy, and fostering a more responsive interaction between patients and healthcare providers. By leveraging state-of-the-art DL techniques, including spatiotemporal convolutional networks and bidirectional recurrent neural networks, the study explores the potential of lip-reading systems to improve patient outcomes. The main objective was to develop and evaluate a functional system specifically designed for medical emergency communication scenarios, supporting individuals during the recovery process by offering an accessible and efficient solution for overcoming temporary communication barriers in urgent and critical situations. To the best of our knowledge, only a few applications explicitly target the usage of lip-reading technologies in post-surgical recovery contexts, emphasizing individual word recognition to facilitate rapid communication in real-world caregiving and clinical environments. Moreover, this is the first study specifically targeting the Italian language, emphasizing the unique challenges and opportunities in adapting lip-reading technologies for non-English languages, particularly those with fewer resources and linguistic tools available. This research highlights the importance of tailoring VSR systems to specific real-world contexts, bridging the gap between experimental advancements and practical applications. In addition to setting a standard for creating accessible and efficient VSR solutions for underserved languages, this study advances the development of VSR technologies by addressing the specific needs of people with vocal impairments and highlighting the potential of VSR to enhance communication, support recovery, and improve the overall quality of life for those affected.

The next sections of this article are organized as follows. In Section 2, the dataset creation and processing are described, along with the proposed lip reading model architectures, the training procedures, and the metrics used to assess performances. Section 3 presents the obtained results and the proposed model’s performance and provides a detailed analysis of the findings, discussing the implications and the limitations of our study and potential areas for future research. Finally, Section 4 draws conclusions, highlighting our contributions and proposing directions for future research.

In this study, a DL-based automatic lip-reading system tailored to recognize Italian words is proposed. The selected words are essential for basic communication and urgent assistance targeting individuals with temporary or permanent vocal cord impairments while recovering from surgery. This section describes the methodologies employed to perform the proposed task, outlining the dataset construction and the DL model’s architecture, along with the experimental setup and evaluation protocols employed to validate our approach. Specifically, we provide the rationale for vocabulary selection, a detailed description of the data collection protocol and the defined controlled conditions, an overview of pre-processing steps, the design and training of the deep learning model, and the metrics and evaluation procedures used to assess the performance of the model.

2.1 Dataset Construction and Preparation

The following subsections describe the data acquisition protocol, the frame processing, and the employed data augmentation techniques, respectively.

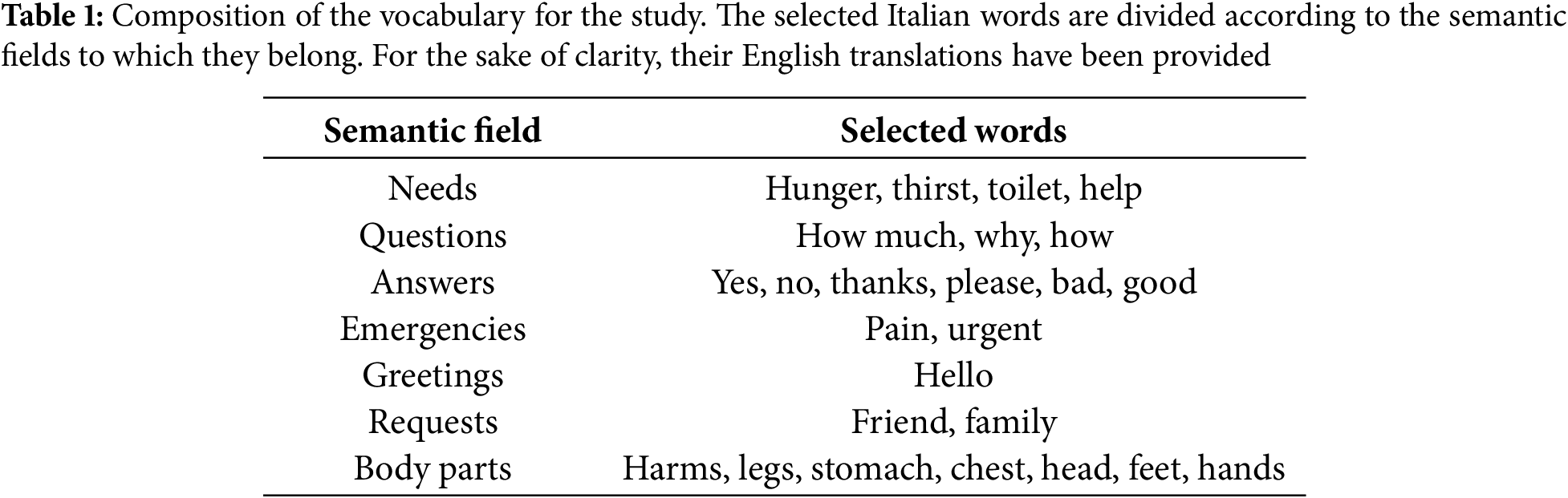

The first step in this study involved constructing a database specifically tailored for Italian language VSR. A vocabulary of twenty-five Italian terms was carefully selected, focusing on words essential for everyday communication and urgent assistance. These terms were drawn from seven semantic fields: Needs, Questions, Answers, Emergencies, Greetings, Requests, and Body Parts. This curated approach was designed to prioritize high-frequency, contextually relevant words that are critical for facilitating communication, particularly for individuals recovering from vocal cord impairments, either temporarily or permanently. Table 1 shows the composition of the vocabulary, outlining the selected words and the semantic fields they belong to.

The database aimed to capture diverse variations in lip movements and ensure its applicability in real-world caregiving and clinical settings. To do so, five subjects (three males and two females) were recorded using a system specifically developed for the automatic acquisition of RGB and depth videos.

The recordings were conducted with the Intel RealSense SR305 RGB-D camera, a device that employs structured light techniques for depth calculation via spatial multiplexing, ensuring precise depth measurement [51]. To ensure precise temporal and spatial alignment, the system features built-in synchronization between RGB and depth streams, which is critical for maintaining data consistency during subsequent preprocessing. The Intel RealSense pipeline was configured to capture RGB and depth video streams simultaneously at a resolution of 640

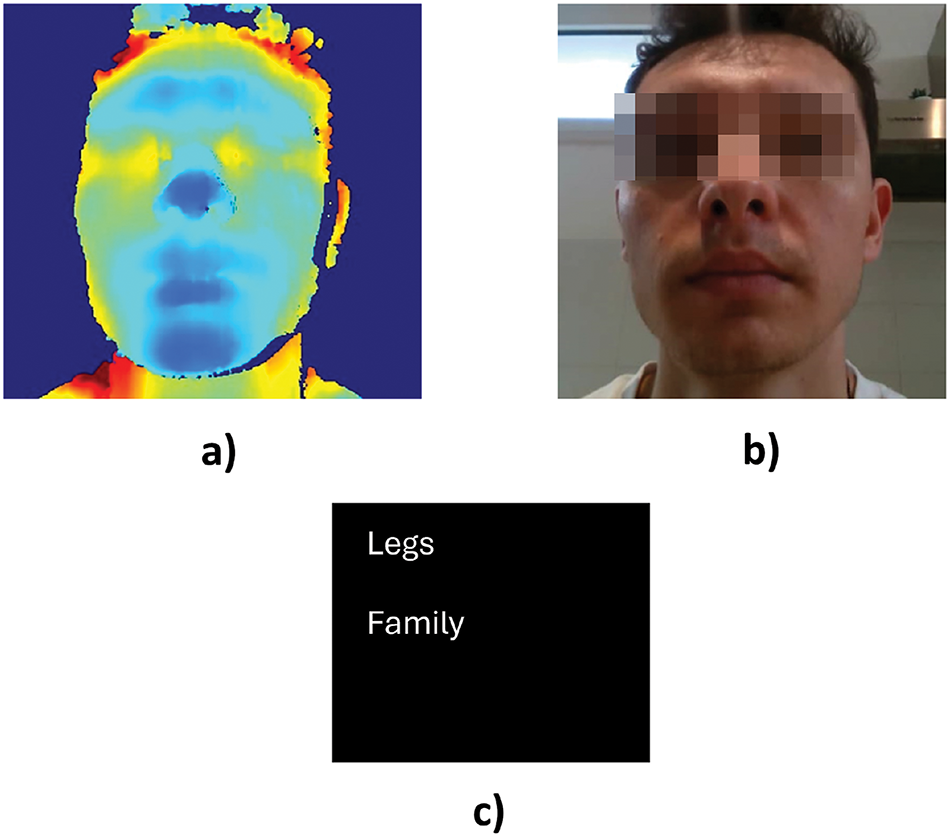

For each video acquisition, an interface displays the real-time depth maps processed and aligned with the corresponding RGB frames, alongside two randomly selected words from the chosen vocabulary (Fig. 1). We have anonymized the image in question as far as possible considering that the image itself is representative of the data being acquired and processed. Nonetheless, we confirm that we conducted the study according to GDPR rules and that informed consents are available from all participants.

Figure 1: Data acquisition example, respectively showing a) depth video frame, b) corresponding RGB video frame, and c) the two randomly selected words from the vocabulary (translated from Italian)

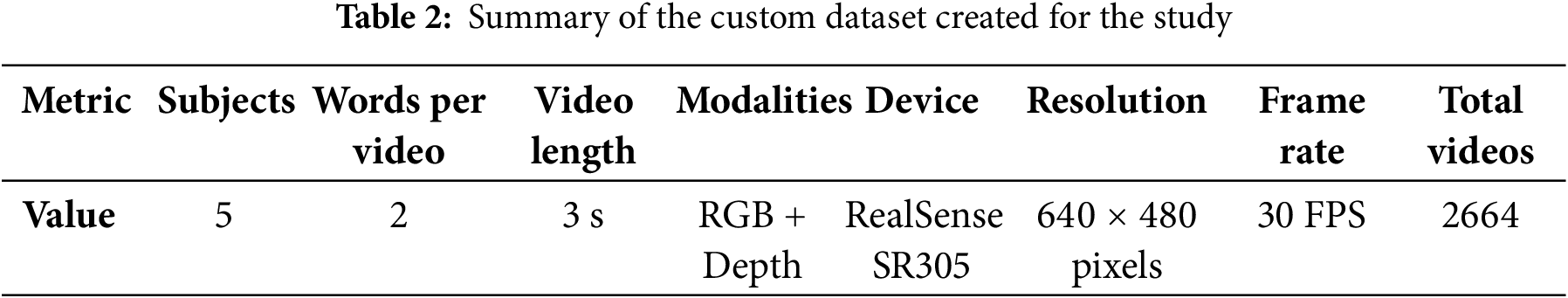

Simultaneously, if the recording process was active, synchronized RGB and depth frames were saved into their respective video files, along with annotation files in the “.align” format to ensure proper labeling and association with the captured data. Each recording session was limited to a duration of 3 s per video. This duration was selected as an optimal balance between minimizing memory overhead during neural network training and providing sufficient time for the subjects to articulate the two randomly chosen words that appeared on the user interface. Throughout the data collection process, a total of 2664 videos were recorded, providing a robust dataset for subsequent analysis and model training. A summary of the custom dataset created for this study is reported in Table 2.

2.1.2 Frame Processing for Mouth Recognition

The acquired videos from the dataset were preprocessed to isolate the Region of Interest (ROI) corresponding to the subject’s mouth, significantly reducing the data volume processed by the model. This optimization not only improves computational efficiency by limiting unnecessary computations but also enhances recognition accuracy by eliminating irrelevant background features that could introduce noise.

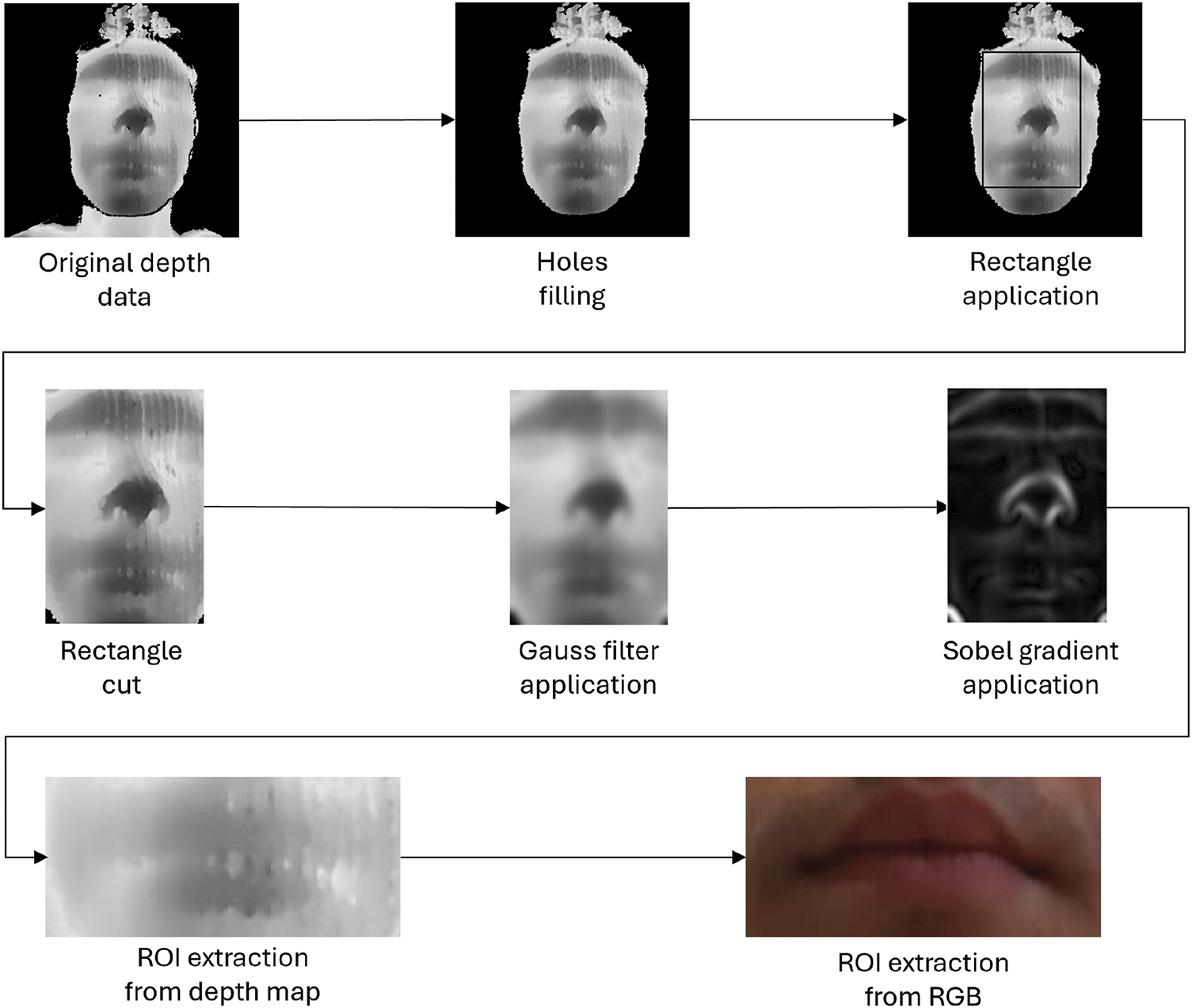

The processing pipeline, illustrated in Fig. 2, outlines the systematic approach undertaken to refine the depth data.

Figure 2: Frame processing pipeline to extract a ROI containing the mouth from the whole image

The initial steps in the processing pipeline were designed to isolate the facial area while effectively removing extraneous elements, such as shoulders or inaccuracies in the depth map. These operations focused on enhancing the relevance of the depth data while retaining the largest connected region in the depth map corresponding to the subject’s face. First, a thresholding operation was applied to the depth pixel intensities to suppress the background and partially or fully eliminate shoulder regions inadvertently captured by the camera. Subsequently, a secondary filtering operation was implemented to remove pixel islands containing irrelevant information. This size-based criterion ensured that any residual shoulder sections not eliminated in the first step were completely removed while still preserving the largest connected region in the depth map, which always corresponded to the subject’s face in the chosen acquisition setup. Interpolation using the OpenCV inpaint function fills any missing data in the depth map, producing a continuous representation of the subject’s facial features.

After isolating the face region, additional steps were taken to extract the mouth region accurately, which is essential for the visual speech recognition task. To achieve this, the cropped depth map, now containing only the facial area, underwent further refinement to localize the ROI corresponding to the mouth. First, the largest inscribable rectangle on this depth map is identified, and the vertices of this rectangle provide the coordinates used to crop only the central portion of the face. The process focuses the analysis on a region rich in meaningful gradients, avoiding disruptions caused by background discontinuities. The use of a Gaussian filter smooths out noise and abrupt variations in the depth map, creating a more consistent representation of facial structures. Following this, the Sobel gradient was applied to enhance discontinuities and detect key facial features such as the forehead, eyes, nose, and lips.

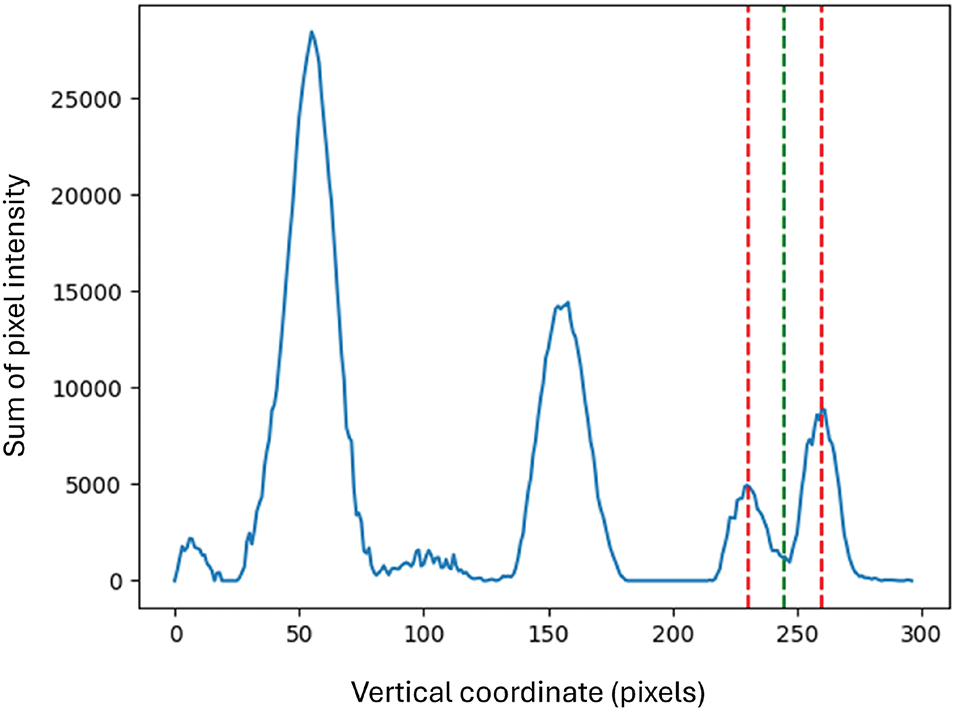

Then, the cropped depth map was analyzed to identify and exclude non-relevant portions of the face by leveraging the geometric and spatial properties of facial features. First, a horizontal summation of the intensity values within the processed depth map was computed, resulting in a profile of discontinuities across the vertical axis. From this profile, peaks exceeding 60% of the mean prominence, which correspond to areas of significant depth variation, such as the contours of the lips, were identified. The final two peaks in the profile were determined to represent the upper and lower lip positions. The midpoint between these peaks was calculated to provide the vertical coordinate for the center of the mouth. For the horizontal coordinate, the midpoint of the previously identified inscribable rectangle enclosing the face was used. This approach, depicted in Fig. 3, ensured accurate localization of the mouth region, setting the stage for subsequent visual speech recognition tasks.

Figure 3: Discontinuities profile calculated across the vertical axis on the cropped depth map. The last two peaks represent the upper and lower lips’ positions (red line), while the center of the mouth is the midpoint between these two peaks (green line)

Since the video recordings show dynamic speech patterns, the vertical coordinates of the mouth change from frame to frame. To capture these variations more smoothly and accurately, a fifth-order Butterworth low-pass filter with a cutoff frequency of

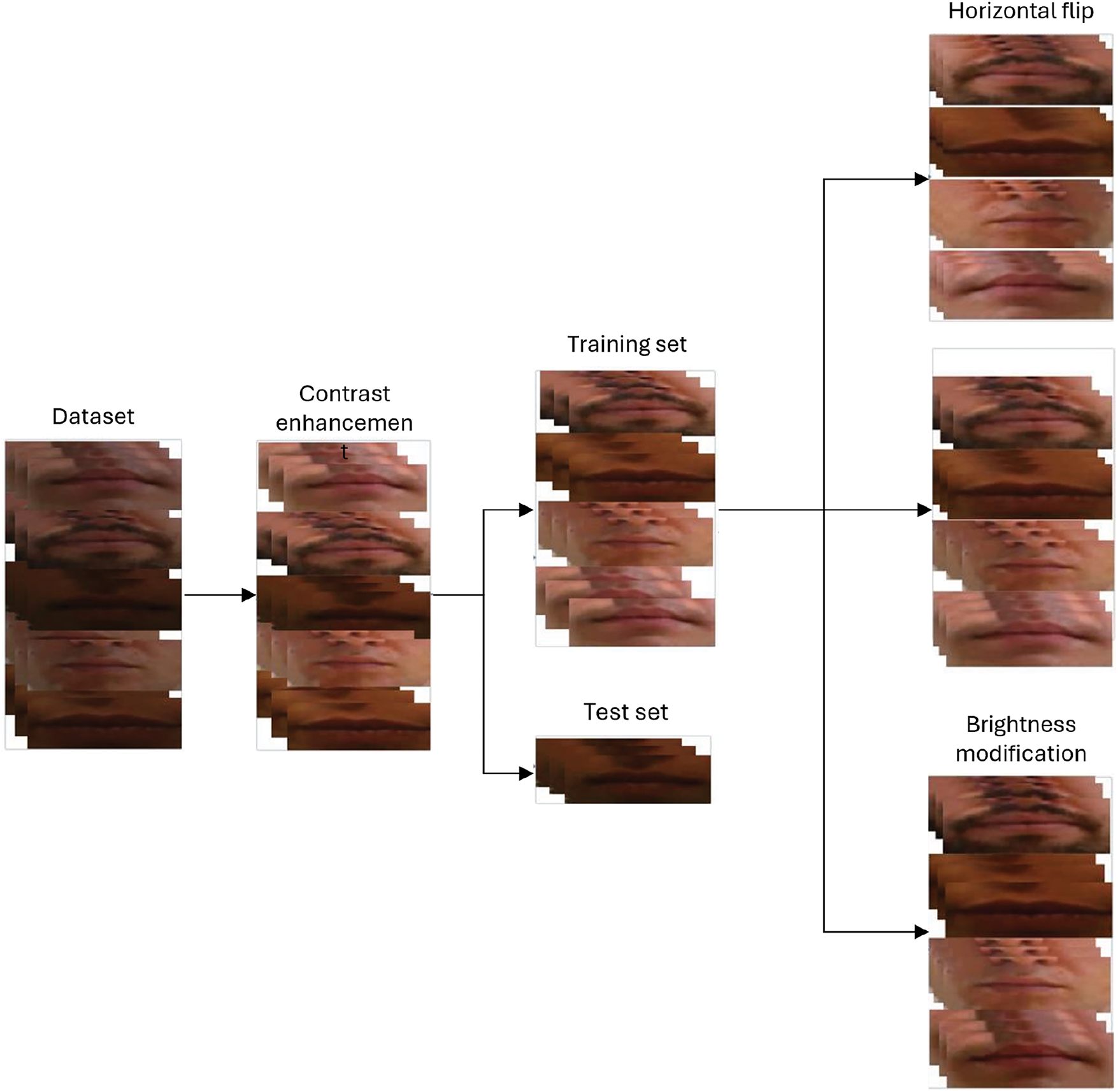

In order to enhance the quality and variability of the acquired recordings necessary for training, a pipeline (Fig. 4) was designed to process input videos using data augmentation techniques.

Figure 4: Data augmentation steps followed for database construction

This approach aligns with common practices in computer vision, where data augmentation is crucial for improving model generalization, as demonstrated in different studies [52–54]. The first step of the pipeline is contrast enhancement, where the contrast of the video frames is increased by a factor of 2.5. This contrast boost is essential for improving the visibility of the mouth, making it easier for the model to focus on the relevant features for lip reading. The frames with enhanced contrast are then saved in a dedicated directory and included in the dataset for further use. Following the contrast enhancement, horizontal flipping is applied to the videos to help the model become more robust by exposing it to variations that reflect real-world conditions. In addition, a portion of the videos is randomly selected to undergo brightness adjustment. This simulates varying lighting conditions, further enhancing the model’s ability to handle different real-world environments.

The resulting augmented dataset consists of 6394 videos, including 2664 enhanced contrast videos, 2664 horizontally flipped videos, and 1066 videos with casual brightness modifications.

2.2 Automatic Visual Speech Recognition

The following subsections describe the employed architecture and the metrics adopted for the evaluation.

2.2.1 Deep Neural Network Architecture

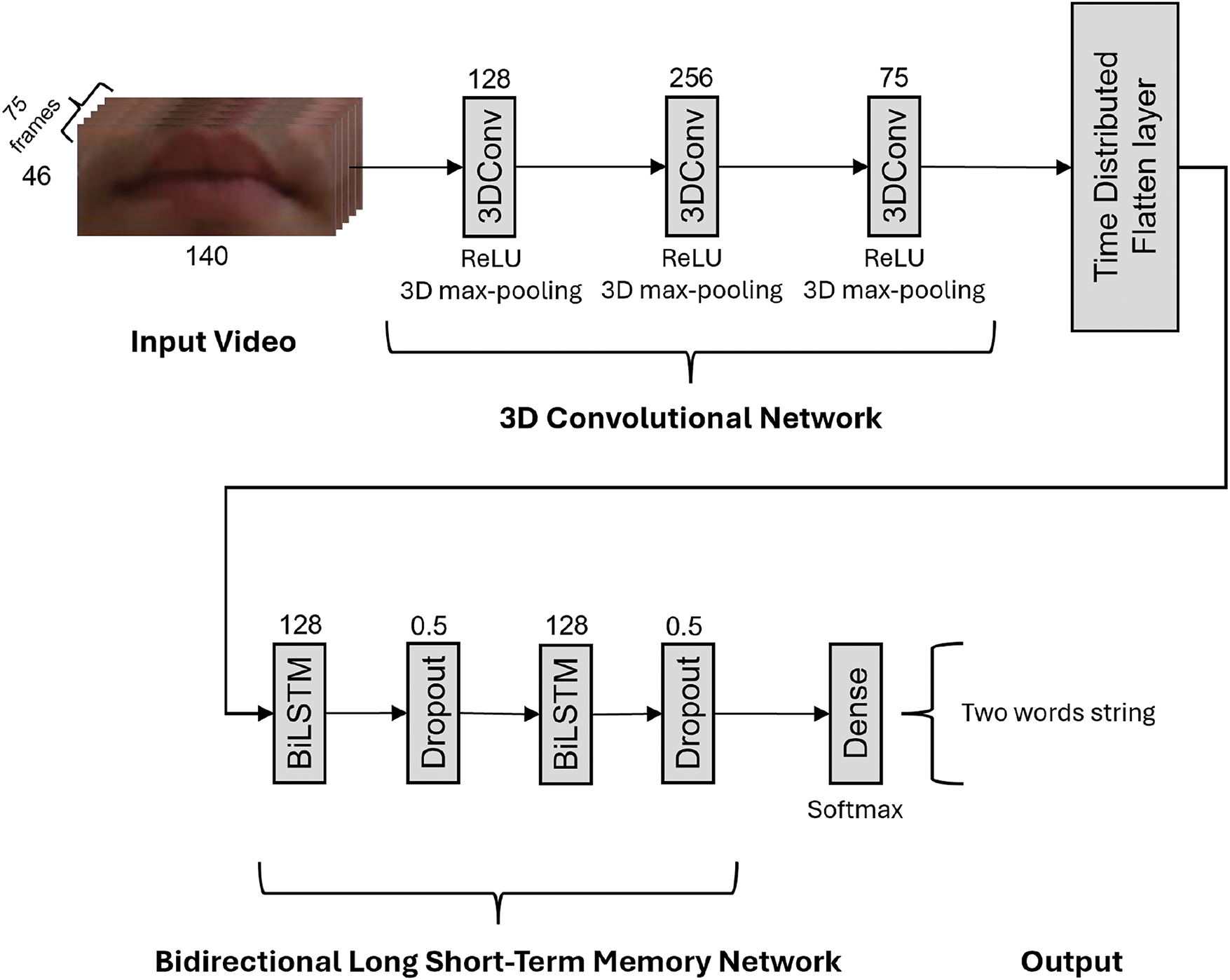

The proposed lip-reading model leverages a hybrid architecture combining 3D convolutional networks (Conv3D) and bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory networks (BiLSTM), as it provides an optimal balance between accuracy and computational efficiency. The model architecture, as shown in Fig. 5 has a series of 3D convolutional layers to extract temporal and spatial features from the input videos passed into the model as a batch of 2.

Figure 5: Overview of the model architecture which combines a Conv3D and a BiLSTM

The input data size, corresponding to the ROI containing the mouth, is

2.2.2 Training and Metrics Evaluation

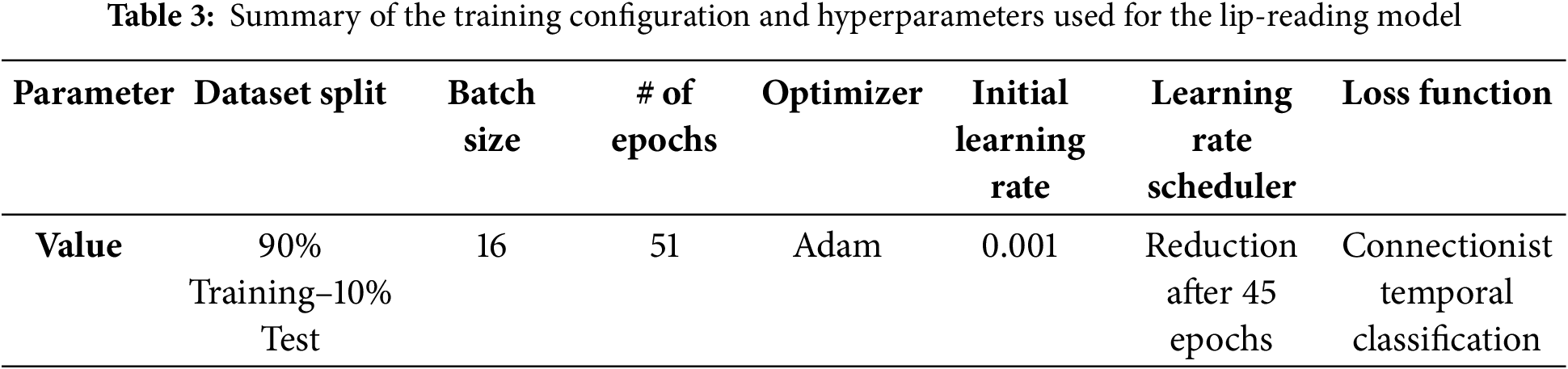

Following the preprocessing procedures detailed in Sections 2.1.2 and 2.1.3, the training of the lip reading model was carried out on the obtained dataset consisting of RGB-D videos with their corresponding transcriptions, randomly split into training and test sets, respectively 90% and 10% of the total videos. The training set was further split, allocating 90% of the training data for actual training and 10% for validation purposes.

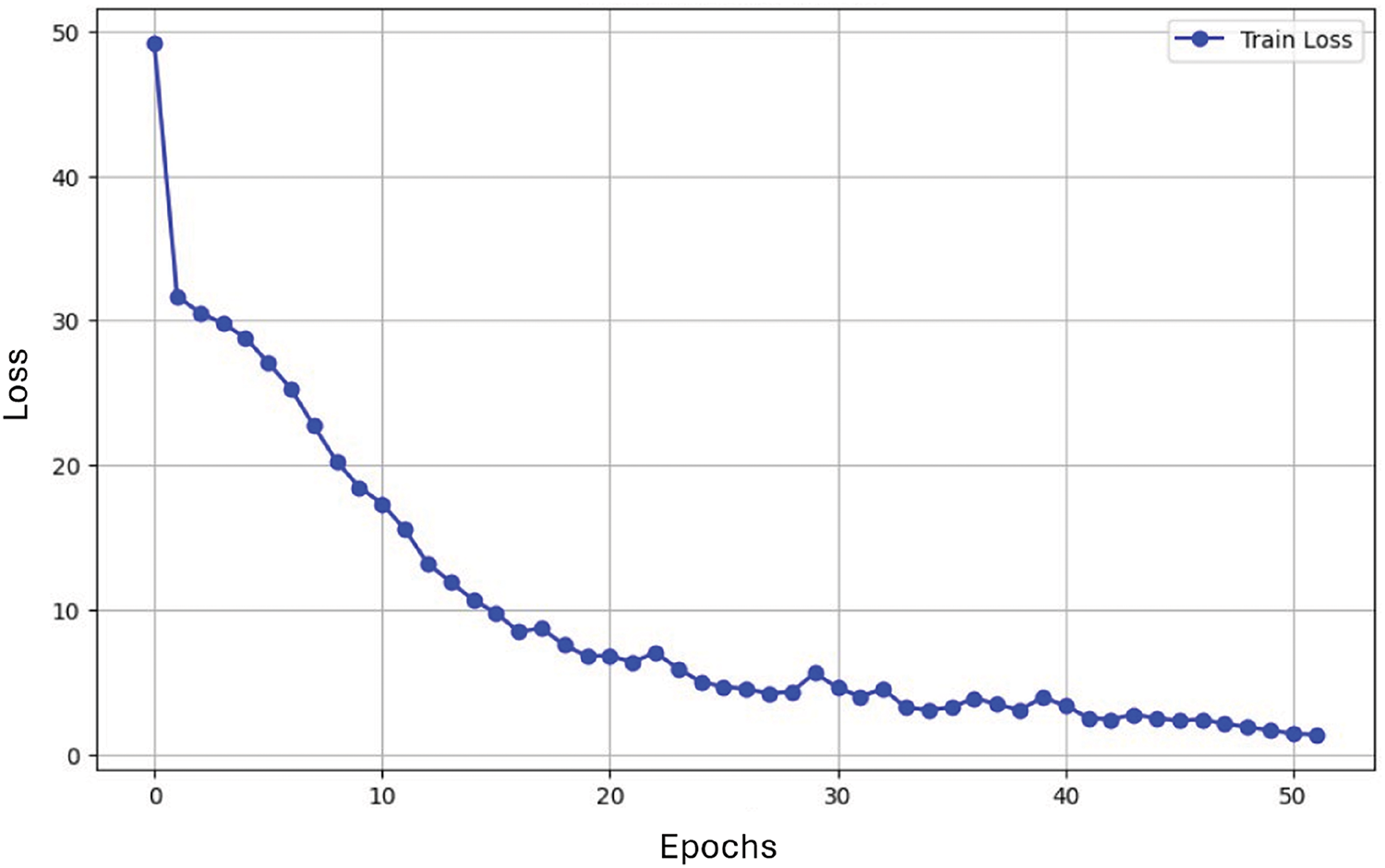

The model ran for a total of 51 epochs using a batch size of 16, with each epoch contributing to refining the temporal and spatial feature extraction capabilities of the network. The training was executed locally on a system equipped with a NVIDIA GTX 1660 Super GPU, featuring 6 GB of VRAM. This setup provided the necessary computational power to handle the high-dimensional data involved in processing video frames, with each frame containing detailed spatial and temporal information. For the training procedure, the model was optimized using the Adam optimizer, which is widely known for its efficiency in handling sparse gradients and ensuring stable convergence during training [55]. The initial learning rate of 0.001 was adjusted dynamically using a scheduler, which reduced the learning rate after 45 epochs to further fine-tune the model and prevent overfitting. This setup allowed the model to progressively learn from the dataset, improving its accuracy and generalizability in lip-reading tasks. The model also employs the Connectionist Temporal Classification (CTC) loss function for handling variable-length input sequences, such as videos of different durations, where there is no predefined alignment between input video frames and output text transcriptions. Fig. 6 shows the trend of the loss function throughout the entire training process.

Figure 6: Loss function trend during training

Table 3 summarizes the training configurations and hyperparameters used to train and validate the model.

To evaluate the effectiveness of the neural network in recognizing spoken words from the acquired videos, accuracy was chosen as the primary evaluation metric. Per-class accuracy was calculated by determining the ratio of correct predictions to the total number of predictions made for each class (i.e., individual words). These metrics allow for evaluating the identification of each specific word in the target set, providing insight into the performance of the network on individual vocabulary items.

For each word in the target set, the number of correct recognitions was compared to the total occurrences of that word in the videos, reflecting the model’s ability to accurately recognize each word under real-world conditions. The overall accuracy of the neural network was then summarized by calculating the average accuracy across all target words in the dataset to give a comprehensive measure of the model’s performance in word-recognition tasks.

Following inference, a verification technique was implemented to assess the words predicted by the neural network, aiming to correct erroneous predictions that do not correspond to meaningful words. To this aim, the Levenshtein distance metric was employed, quantifying the minimum number of operations–insertions, deletions, or substitutions–required to transform one string into another, thus refining predictions without introducing semantic biases. The rationale behind choosing Levenshtein distance lies in its suitability for character-level error correction. Since the model predicts words as sequences of individual characters, recognition errors typically manifest as minor discrepancies within a word rather than as complete misclassifications of one word for another semantically distant word. The correction process involved comparing each predicted word against the twenty-five words in the predefined vocabulary. The algorithm computed the Levenshtein distance between the predicted output and each word in the dataset. If the predicted word was not present in the vocabulary, the word with the smallest distance was selected as the most probable replacement. In cases where multiple words had the same minimum distance, the algorithm prioritized correction based on network confidence, selecting the word associated with the lowest prediction accuracy to optimize overall system performance. This approach is particularly effective in mitigating recognition errors, especially when words are phonetically similar or affected by noise and visual distortions. Furthermore, an accuracy metric was introduced to evaluate the system’s ability to recognize sequences of two consecutive words. The Levenshtein distance was used to compare the predicted sequence with the ground-truth sequence, and the computed distance was normalized by the total length of the string. The resulting value was then subtracted from 1, yielding the final sequence accuracy score. This score was expressed as a percentage by multiplying the result by 100, providing a quantitative assessment of the model’s performance in word sequence recognition.

The following section reports the results obtained regarding the neural network model’s ability to recognize single words and strings from the provided videos and discusses the potential and limitations of the study in the current research landscape.

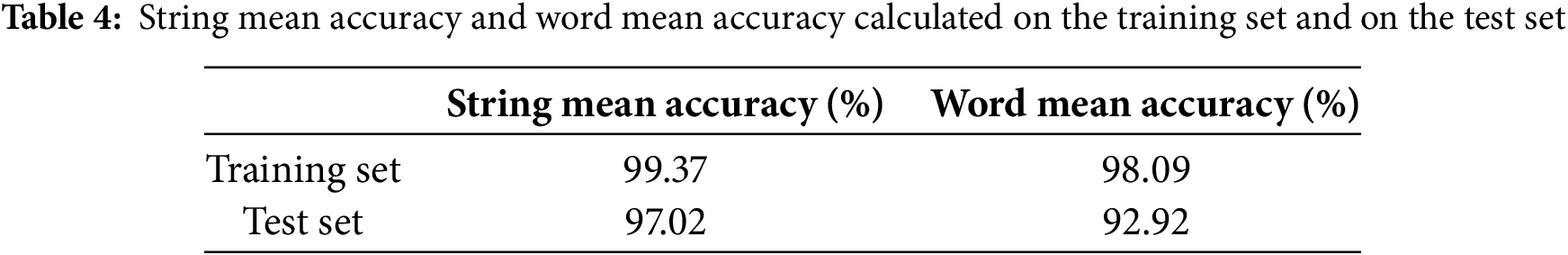

Table 4 presents the string mean accuracy, which evaluates the correct recognition of the two-word sequences, and the word mean accuracy, which assesses the precision of individual word recognition, calculated across all the videos in both the training and test sets.

Accuracy was chosen as the primary performance metric as it effectively reflects the percentage of correctly predicted words in the data set. Unlike traditional classification tasks, our model operates at the character level, generating sequences of individual letters for each input video. These sequences are subsequently processed to reconstruct the corresponding word. Due to this character-based sequence prediction approach, traditional classification metrics such as precision, recall, and F1-score, which typically rely on discrete class assignments and confusion matrices, are less suitable. In our case, misclassifications occur at the letter level rather than at the word level, meaning the system does not directly confuse one complete word with another but may instead produce minor errors in individual letter predictions. Considering these characteristics, accuracy provides a meaningful and interpretable measure of the system’s effectiveness in correctly reconstructing entire words, which is particularly relevant for the clinical emergency context targeted by this study.

The model shows strong performances on both the training and test sets, with only a slight decrease in accuracy when moving from the training to the test data. The decrease in accuracy between the training and test sets, both in string and mean accuracy, is typical in AI tasks and reflects the challenges of generalizing to unseen data, especially in dynamic and complex tasks like lip-reading, where factors like lighting variations, mouth shape, and articulation might affect performance in real-world scenarios. Notably, the higher String Mean Accuracy compared to Word Mean Accuracy in both sets suggests that while the model may introduce minor errors at the word level, it still maintains a high ability to correctly classify word sequences.

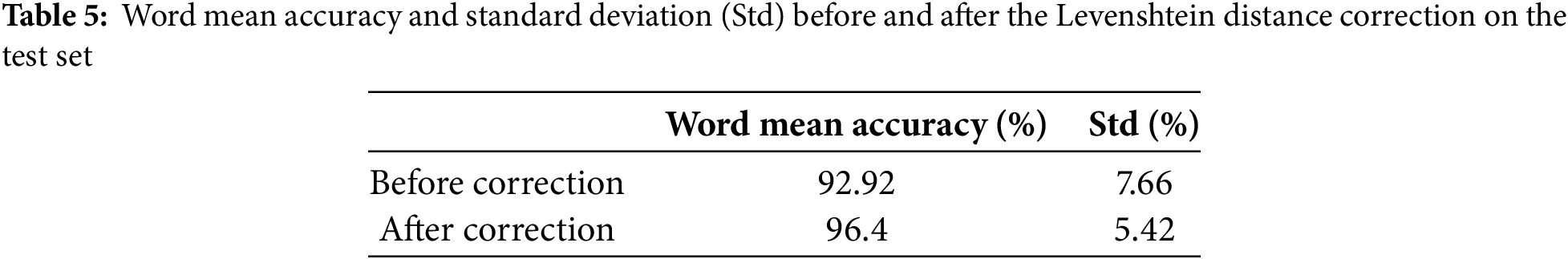

Table 5 shows the average accuracy values and the corresponding standard deviations (std) calculated by considering all the target words present in the videos of the test set, both before and after the application of the Levenshtein distance correction.

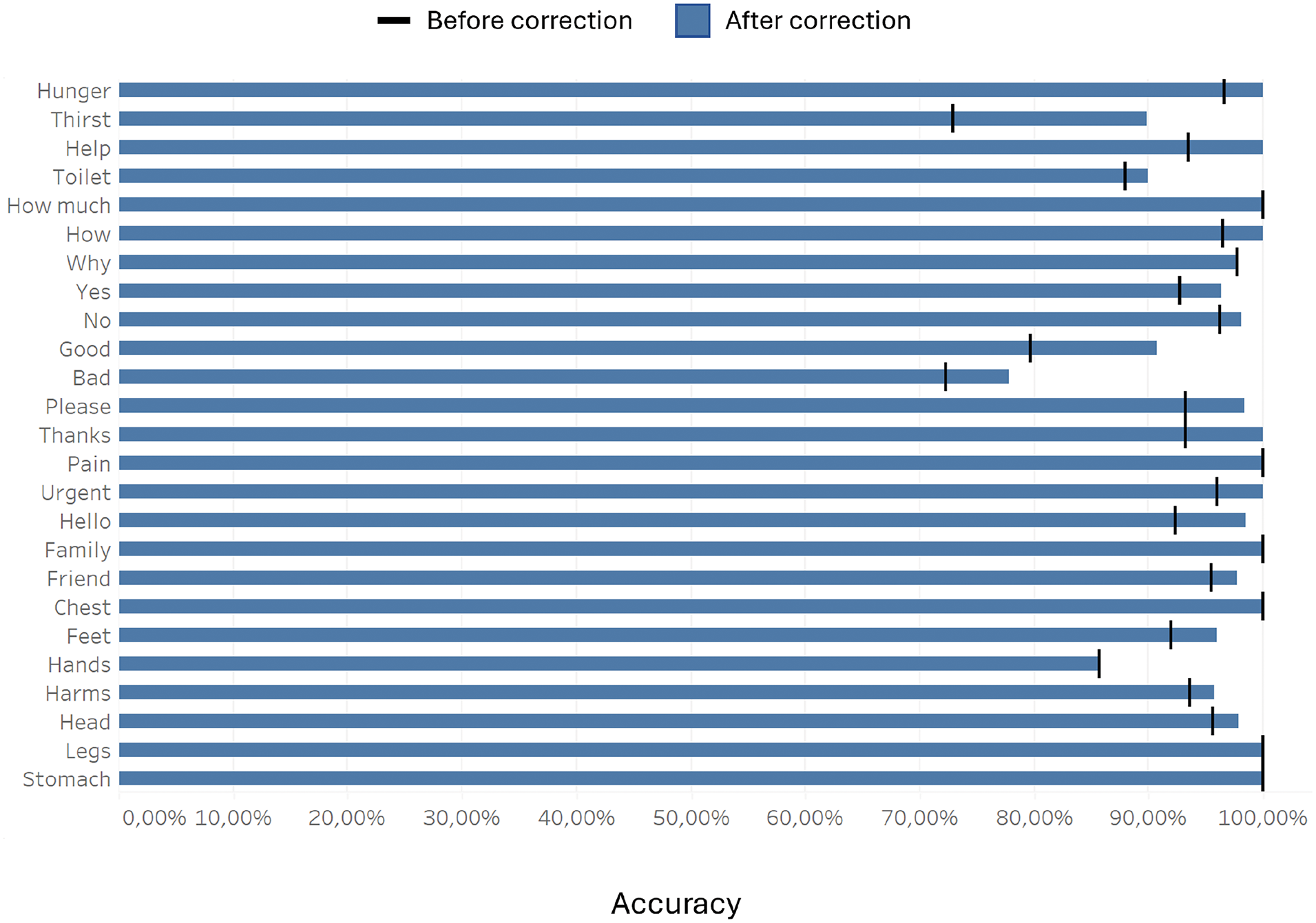

The mean accuracy metrics before and after the application of the Levenshtein distance correction on the test set highlight the effectiveness of the developed method in enhancing recognition performance: after word correction using the Levenshtein distance to refine predictions, the average accuracy increased from 92.92% to 96.4%, while reducing the standard deviation from 7.66% to 5.42%. Moreover, Fig. 7 provides an indication of the mean accuracy values for each individual word before and after the application of the Levenshtein distance correction on the test set.

Figure 7: Individual accuracy of each word before and after the application of the Levenshtein distance correction

Specifically, Fig. 7 provides a comparison between the baseline of accuracy values (before the application of the Levenshtein distance correction), showing the accuracy of the neural network in recognizing each word without any correction and the improvement in accuracy after applying the implemented correction technique, where predicted words were adjusted based on their proximity to the correct words in the selected vocabulary, calculated using the Levenshtein distance. This comparison further justifies the implementation of this correction technique for the purpose of our study.

The results obtained from this study demonstrate promising performance in lip-reading for recognizing common words that are essential for basic communication. Moreover, to the best of our knowledge, this is the only study that involves an Italian term vocabulary for lip-reading purposes, addressing a critical gap in VSR research, which has predominantly focused on English-based datasets.

The use of Conv3D and BiLSTM architectures plays a crucial role in the model’s effectiveness: Conv3D networks are well-established for their ability to capture both spatial and temporal features from video data, which is essential for tasks like lip-reading, where the movement of the lips over time is integral to understanding the words being spoken, while BiLSTM networks are particularly effective for sequence modeling tasks because they capture dependencies in both forward and backward directions, allowing the model to understand the context in a temporal sequence. This bidirectional approach has been shown to significantly improve performance in lip-reading tasks [24], as the combination of these architectures allows the model to better capture the dynamics of lip movements, leading to enhanced word recognition accuracy.

A key advantage of the proposed method is that it does not require explicit word boundaries or manual segmentation, which is a common challenge in traditional lip-reading approaches. Unlike conventional systems that rely on predefined time markers to segment words within a continuous speech sequence [27,29,31,32], our model is designed to predict words as character sequences using a CTC loss function. This approach eliminates the need for frame-level alignment, allowing the network to dynamically learn the relationship between lip movements and the corresponding text output. Compared to existing works that employ complex segmentation pipelines or require large-scale datasets for supervised frame-level annotation [28,36,38], our approach reduces preprocessing overhead and simplifies the training process. The absence of word segmentation constraints makes the system more flexible and robust, particularly in real-world medical communication scenarios, where patients may produce non-standardized, irregular, or interrupted speech patterns due to their condition. Additionally, the Levenshtein-based post-processing correction mechanism further enhances prediction reliability by refining outputs at the character level rather than depending on strict word boundaries. This is particularly beneficial in low-resource environments, where speech-impaired individuals may communicate with variable articulation speeds or pauses, making rigid segmentation impractical. However, while this design increases generalizability, it may also lead to challenges in recognizing words with highly similar viseme patterns, especially in cases of limited training data, as minor differences in articulation can be difficult to capture without explicit temporal cues.

The employment of a low-cost 3D camera setup provides significant advantages over traditional 2D cameras, particularly in capturing detailed three-dimensional facial features. The ability to detect the depth and angles of lip movements allows the model to gain a more accurate understanding of lip dynamics, which is critical for tasks like lip-reading. Moreover, the application of an efficient ROI selection procedure allows the model to operate efficiently even with consumer-grade graphics hardware. By selecting a specific ROI within the video frames, the network can focus on the most relevant part of the image, reducing the computational load associated with processing the entire frame, not only boosting computational efficiency but also enhancing the model’s ability to make accurate predictions in real-time, even under resource constraints. This approach not only improves performance but also opens up the potential for real-world applications in low-resource environments, where cost-effective solutions are essential. Beyond improving local performance, this approach also facilitates scalability through cloud-based computing, leveraging GPU-accelerated servers to process lip-reading inputs remotely. This would make it possible to transfer computationally demanding tasks from edge devices to remote servers, guaranteeing real-time performance even on low-power hardware like mobile devices or embedded systems. It would also maximize inference efficiency by striking a balance between local processing and cloud support to guarantee low latency while consuming the least amount of bandwidth. Cloud-based deployment could also facilitate centralized model updates, enabling continuous improvements without requiring direct modifications to end-user devices. By reducing hardware and computational requirements, this approach can provide a practical and scalable solution, especially in resource-constrained situations, such as mobile or emergency settings where traditional high-performance computing resources may not be available. Indeed, this study has demonstrated exceptionally high performance in recognizing the target words, showing significant potential for lip-reading technologies in real-world applications, especially in contexts where quick and accurate word recognition is critical, such as in emergency settings.

Comparing the obtained results with other studies focusing on a similar approach, the proposed approach achieves superior performance. In this sense, Prashanth et al. [24], employing similar network architectures, reported a word accuracy of 92.04% on the GRID audiovisual sentence corpus, which is commonly utilized in English language lip-reading projects. While their architecture shares similarities with ours (such as the combination of CNN and LSTM modules), several distinctions must be highlighted. While their results validate the strength of spatiotemporal feature extraction and recurrent processing, the proposed approach achieves a higher accuracy of 96.4%, demonstrating its robustness in handling isolated word recognition. The improved performance can be attributed to task-specific optimizations, such as the integration of a depth-based input stream, which enriches visual feature representation, particularly for subtle articulatory movements, and applies a carefully designed ROI selection focused on the mouth area, reducing background noise and irrelevant facial movements. Moreover, our Levenshtein distance-based post-processing refines the output by correcting minor character-level errors, ensuring more accurate word reconstruction. These task-specific optimizations contribute to our higher accuracy of 96.4%, despite operating in a real-world, clinically oriented dataset rather than a controlled laboratory corpus. In contrast, Matsui et al. [26], in their work using a mobile device-based speech enhancement system tailored for laryngectomees rehabilitation, achieved a word recognition rate of 65% on a vocabulary of twenty Japanese words on the first candidate for prediction, reaching 100% only considering up to the third candidate, while Nakahara et al. [22] obtained 63% recognition accuracy with a single subject and a vocabulary size of twenty words. While their approach highlights the potential of mobile-friendly lip-reading solutions, the significantly lower accuracy in first-choice predictions suggests limitations in handling word differentiation without additional context or ranking mechanisms. By comparison, our model consistently achieves high accuracy on the first predicted word without the need for multiple candidate evaluations, which is critical for real-time communication in medical and emergency settings where delays or ambiguities can compromise patient interaction. These comparisons underline the robustness and effectiveness of the proposed methodology, particularly in scenarios involving limited vocabulary sizes, such as assistive communication for speech-impaired individuals, demonstrating that language-specific adaptations, depth-enhanced processing, and post-recognition refinement techniques contribute to achieving superior performance compared to prior works.

However, challenges remain, particularly related to the inherent ambiguity in lip movements, which can lead to confusion between visually similar words, especially in cases where the words share visual or phonetic features, making them difficult to distinguish in a purely visual task [31]. Furthermore, the generalization of the model to diverse real-world environments introduces additional difficulties, such as variations in lighting, camera angles, and background noise, all of which can distort visual input and affect the model’s ability to identify words accurately.

In terms of word accuracy, most words achieved recognition rates above 95%, with most words achieving very high recognition rates. However, certain words, like “bad” and “hands” (in Italian “male” and “mani”) showed lower accuracies of 78% and 86%, respectively, showing a discrepancy with respect to the other selected words that can be attributed to multiple factors. Firstly, both words involve lip movements that are less distinctive and more easily confusable with other words in the dataset due to similar viseme patterns (for example, the bilabial consonant /m/ in “male” and “mani” appears in other words as well, reducing discriminability). Visual ambiguity is a major challenge, as mentioned earlier, where similar phonetic or lip movement patterns between words can hinder recognition. Additionally, pronunciation differences across individuals can introduce variability in how words appear visually, further complicating recognition. Slight variations in speed or style of articulation among different speakers may alter the way lip movements are perceived, adding an additional level of difficulty for lip-reading patterns, so they may have introduced inconsistencies during training, particularly for words of shorter duration or with faster transitions between phonemes.

Several strategies can be considered to improve the model’s performance and address these challenges. Increasing the diversity of the training dataset is essential for improving the generalizability and robustness of the model in real-world scenarios. This can be achieved by incorporating a broader range of subjects with varying facial structures, ethnicities, ages, and speaking styles. In real-world applications, users may interact with the system under uncontrolled settings, where factors like shadows, occlusions, varying speech speeds, and facial accessories (such as masks, glasses, and facial hair) could impact recognition accuracy. By training the model on a more diverse set of conditions, it will be better equipped to handle these variations, leading to improved performance across different environments. Additionally, expanding the dataset to include varied recording conditions, such as different lighting setups, camera angles, distances, and background environments, will help mitigate the risk of the model overfitting to a specific set of conditions. Additionally, exploring more advanced model architectures, such as adding more convolutional layers or optimizing training parameters, could enhance the model’s ability to detect subtle variations in lip movement, which are crucial for distinguishing between similar words.

To better understand the contribution of each component of the model and optimize its design, future work will include systematic ablation studies. These studies will involve selectively disabling or modifying specific elements of the model architecture and training pipeline–such as data augmentation techniques, the number of convolutional layers, dropout regularization, and feature extraction blocks–to assess their individual impact on overall performance. By analyzing how the removal or alteration of these components affects recognition accuracy, we aim to identify the most critical factors that contribute to the system’s robustness and precision, providing valuable insights into optimizing the balance between model complexity and computational efficiency, thus ensuring that the system remains both effective and lightweight for deployment in real-time clinical scenarios.

The current system has been proposed employing a restricted vocabulary size, hence will require more varied linguistic contexts for further validation. Future work will focus on expanding the dataset to include a broader range of linguistic elements, incorporating more complex and diversified vocabulary beyond the current set of essential words, which will further support the system’s application in diverse conversational contexts. While the current system is primarily optimized for medical emergency scenarios, where rapid and accurate recognition of a predefined vocabulary is essential, this expansion will contribute to enhancing the system’s generalizability, handling a wider spectrum of communication needs and supporting real-world interactions beyond the medical setting, such as natural daily conversations, dialectal variations, and out-of-vocabulary situations. In particular, increasing the vocabulary size introduces greater variability in lip movements, as more complex and diverse words often involve a wider range of phonemes and articulation patterns. This will not only improve the flexibility and applicability of the model but also contribute to the development of more adaptive and scalable lip-reading solutions.

Another important aspect to consider in future developments is the cross-dataset evaluation of the proposed model. Cross-dataset evaluation involves training and testing the model on different datasets to assess its ability to generalize across various recording conditions, linguistic contexts, and speaker populations. While the current study is based on a custom dataset specifically designed to address the needs of Italian-speaking individuals in medical emergency contexts, conducting a cross-dataset evaluation of our system, once comparable resources become available, will be essential to validate its robustness and adaptability. This type of evaluation will allow us to investigate how well the model can transfer knowledge from controlled experimental settings to real-world scenarios, as well as identify potential biases or limitations linked to dataset-specific features. Furthermore, cross-dataset experiments will support the refinement of the system by exposing it to a wider range of visual and linguistic variations, ultimately contributing to a more reliable and scalable solution for diverse healthcare and communication applications.

Moreover, to ensure the system’s practical viability in clinical applications, future validation will focus on real-world testing with patients and healthcare professionals in hospital and rehabilitation center environments. This will involve user-centered evaluations, where both patients and clinicians provide feedback on aspects such as ease of use, comfort, and integration into existing therapeutic workflows. Additionally, real-world validation will help identify potential challenges in deployment, including variability in patient demographics, lighting conditions, and interaction styles, which could impact system performance. By conducting iterative testing in clinical settings, we aim to refine the system to enhance accuracy, robustness, and adaptability to different medical scenarios, ensuring its effectiveness beyond controlled laboratory conditions. With this in mind, we aim to further optimize the system for real-world applications and expand our experimental analysis by examining the impact of various factors on system performance. Specifically, we will investigate how vocabulary complexity, environmental conditions, and real-world variability affect the system’s accuracy and robustness. This analysis will provide valuable insights into the system’s adaptability and guide future improvements for deployment in clinical and everyday scenarios. Multimodal approaches could be leveraged to broaden the system’s applicability and enhance its robustness in real-world scenarios. For example, combining visual data with audio inputs, when available, or contextual understanding, could be a promising avenue for improving word recognition accuracy, as the complementary nature of audio and visual information can help reduce reliance on potentially ambiguous visual cues alone, which has been suggested as a key enhancement for lip-reading systems. This multimodal fusion can help reduce the system’s dependence on purely visual features, which is especially beneficial for distinguishing between visually similar words that might be challenging to differentiate based on lip movements alone. Additionally, using facial expressions, speaker identity, or situational awareness could further refine predictions, making the system more adaptive and intuitive in real communication settings.

Lip-reading is an essential tool for facilitating communication, particularly for individuals with vocal or hearing impairments and in environments where auditory cues are unreliable, such as noisy or emergency settings. Despite significant advancements in the field, accurate word recognition remains a challenging task, primarily due to visual ambiguities in lip movements and variations in pronunciation across individuals.

This study introduces a DL-based automatic lip-reading system specifically designed to aid individuals with vocal cord pathologies in their daily interactions, addressing the challenges of post-surgical vocal rehabilitation by focusing on the recognition of a targeted set of commonly used Italian words essential for basic communication and urgent assistance. Recognizing the significant communication barriers that patients face during recovery, this method creates an alternative communication tool that prioritizes simplicity, efficiency, and accessibility by concentrating on word-level recognition rather than processing entire sentences.

The combination of advanced neural architectures, such as Conv3D and BiLSTM, alongside effective preprocessing and correction techniques, demonstrates the system’s capacity to achieve high word recognition accuracy, underscoring its potential for real-world applications. Additionally, it highlights the potential for leveraging advanced DL architectures in healthcare-focused applications, particularly for enhancing patient autonomy and accessibility. Furthermore, to the best of our knowledge, this research represents the first application of automatic lip-reading systems specifically tailored to the Italian language. While the majority of state-of-the-art models and datasets have been developed for English, this study highlights the challenges inherent in adapting lip-reading technologies to less-resourced languages, where phonetic-visual variability, coarticulation effects, and dataset scarcity pose significant obstacles. Given that lip articulation patterns vary across languages, in the absence of large-scale, high-quality datasets, models trained on English corpora often struggle to generalize effectively to other languages, leading to reduced recognition accuracy. Although this study focuses on the Italian language, the proposed approach is inherently generalizable to other languages and underscores the necessity of expanding technological advancements beyond English-speaking contexts. By pioneering Italian-language lip-reading, this research not only contributes to the advancement of VSR applications but also lays the foundation for more globally inclusive and culturally relevant solutions in speech recognition and assistive communication technologies.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Matteo Boemio, Gianmarco Lorenzetti, Ilaria Pulito, Diego Romagnoli, Valeria Saponaro; methodology, Matteo Boemio, Gianmarco Lorenzetti, Ilaria Pulito, Diego Romagnoli, Valeria Saponaro; software, Matteo Boemio, Gianmarco Lorenzetti, Ilaria Pulito, Diego Romagnoli, Valeria Saponaro; validation, Chiara Innocente, Matteo Boemio, Gianmarco Lorenzetti, Ilaria Pulito, Diego Romagnoli, Valeria Saponaro; formal analysis, Matteo Boemio, Gianmarco Lorenzetti, Ilaria Pulito, Diego Romagnoli, Valeria Saponaro; investigation, Matteo Boemio, Gianmarco Lorenzetti, Ilaria Pulito, Diego Romagnoli, Valeria Saponaro; resources, Enrico Vezzetti; data curation, Chiara Innocente, Giorgia Marullo, Luca Ulrich; writing—original draft preparation, Matteo Boemio, Gianmarco Lorenzetti, Ilaria Pulito, Diego Romagnoli, Valeria Saponaro; writing—review and editing, Chiara Innocente, Giorgia Marullo, Luca Ulrich, Enrico Vezzetti; visualization, Chiara Innocente, Matteo Boemio, Gianmarco Lorenzetti, Ilaria Pulito, Diego Romagnoli, Valeria Saponaro; supervision, Chiara Innocente, Giorgia Marullo, Luca Ulrich, Enrico Vezzetti; project administration, Enrico Vezzetti; funding acquisition, Enrico Vezzetti. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available on request from the authors.

Ethics Approval: We have anonymized the image in question as far as possible considering that the image itself is representative of the data being acquired and processed. Nonetheless, we confirm that we conducted the study according to GDPR rules and that informed consents are available from all participants.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Stachler RJ, Francis DO, Schwartz SR, Damask CC, Digoy GP, Krouse HJ, et al. Clinical practice guideline: hoarseness (Dysphonia) (Update). Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;158(S1):S1–42. doi:10.1177/0194599817751030. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Rosen CA, Lee AS, Osborne J, Zullo T, Murry T. Development and validation of the voice handicap index-10. The Laryngoscope. 2004;114(9):1549–56. doi:10.1097/00005537-200409000-00009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Lee H, Chang HW, Ji JY, Lee JH, Park KH, Jeong WJ, et al. Early injection laryngoplasty for acute unilateral vocal fold paralysis after thoracic aortic surgery. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2024;51(6):984–9. doi:10.1016/j.anl.2024.09.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Fernandes-Taylor S, Damico-Smith C, Arroyo N, Wichmann M, Zhao J, Feurer ID, et al. Multicenter development and validation of the vocal cord paralysis experience (CoPEa patient-reported outcome measure for unilateral vocal fold paralysis-specific disability. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022;148(8):756–63. doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2022.1545. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Pangaonkar S, Gunjan R. Estimation techniques of vocal fold disorder: a survey. Int J Med Eng Inform. 2023;15(3):245–56. doi:10.1504/IJMEI.2023.130730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Goldschen AJ, Garcia ON, Petajan ED. Rationale for phoneme-viseme mapping and feature selection in visual speech recognition. In: Speechreading by humans and machines: models, systems, and applications. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 1996. p. 505–15. [Google Scholar]

7. Bayoudh K, Knani R, Hamdaoui F, Mtibaa A. A survey on deep multimodal learning for computer vision: advances, trends, applications, and datasets. Vis Comput. 2022;38(8):2939–70. doi:10.1007/s00371-021-02166-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Li D, Gao Y, Zhu C, Wang Q, Wang R. Improving speech recognition performance in noisy environments by enhancing lip reading accuracy. Sensors. 2023;23(4):2053. doi:10.3390/s23042053. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Fenghour S, Chen D, Guo K, Li B, Xiao P. Deep learning-based automated lip-reading: a survey. IEEE Access. 2021;9:121184–205. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3107946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Mirzaei M, Ghorshi S, Mortazavi M. Audio-visual speech recognition techniques in augmented reality environments. Vis Comput. 2014;30(3):245–57. doi:10.1007/s00371-013-0841-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Lu L, Yu J, Chen Y, Liu H, Zhu Y, Kong L, et al. Lip reading-based user authentication through acoustic sensing on smartphones. IEEE/ACM Transact Netw. 2019;27(1):447–60. doi:10.1109/TNET.2019.2891733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Mathulaprangsan S, Wang CY, Kusum AZ, Tai TC, Wang JC. A survey of visual lip reading and lip-password verification. In: 2015 International Conference on Orange Technologies (ICOT); Hong Kong, China; 2015. p. 22–5. [Google Scholar]

13. Hao M, Mamut M, Yadikar N, Aysa A, Ubul K. A survey of research on lipreading technology. IEEE Access. 2020;8:204518–44. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3036865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Checcucci E, Piazzolla P, Marullo G, Innocente C, Salerno F, Ulrich L, et al. Development of bleeding artificial intelligence detector (BLAIR) system for robotic radical prostatectomy. J Clin Med. 2023;12(23):7355. doi:10.3390/jcm12237355. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Ulrich L, Carmassi G, Garelli P, Lo Presti G, Ramondetti G, Marullo G, et al. SIGNIFY: leveraging machine learning and gesture recognition for sign language teaching through a serious game. Future Internet. 2024;16(12):447. doi:10.3390/fi16120447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Ulrich L, Nonis F, Vezzetti E, Moos S, Caruso G, Shi Y, et al. Can ADAS distract driver’s attention? An RGB-D camera and deep learning-based analysis. Appl Sci. 2021;11(24):11587. doi:10.3390/app112411587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Mehrish A, Majumder N, Bharadwaj R, Mihalcea R, Poria S. A review of deep learning techniques for speech processing. Inf Fusion. 2023;99(19):101869. doi:10.1016/j.inffus.2023.101869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Pu G, Wang H. Review on research progress of machine lip reading. Vis Comput. 2023;39(7):3041–57. doi:10.1007/s00371-022-02511-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Yeo JH, Kim M, Watanabe S, Ro YM. Visual speech recognition for languages with limited labeled data using automatic labels from whisper. In: ICASSP 2024—2024 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); Seoul, Republic of Korea; 2024. p. 10471–5. [Google Scholar]

20. Juyal A, Joshi RC, Jain V, Chaturvedi S. Analysis of lip-reading using deep learning techniques: a review. In: 2023 International Conference on the Confluence of Advancements in Robotics, Vision and Interdisciplinary Technology Management (IC-RVITM); Bangalore, India; 2023. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

21. Fernandez-Lopez A, Sukno F. Survey on automatic lip-reading in the era of deep learning. Image Vision Comput. 2018;78(9):53–72. doi:10.1016/j.imavis.2018.07.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Nakahara T, Fukuyama K, Hamada M, Matsui K, Nakatoh Y, Kato YO, et al. Mobile device-based speech enhancement system using lip-reading. In: Dong Y, Herrera-Viedma E, Matsui K, Omatsu S, González Briones A, Rodríguez González S, editors. Distributed Computing and Artificial Intelligence, 17th International Conference. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2021. p. 159–67. [Google Scholar]

23. Assael YM, Shillingford B, Whiteson S, de Freitas N. LipNet: sentence-level lipreading. arXiv:1611.01599. 2016. [Google Scholar]

24. Prashanth BS, Manoj Kumar MV, Puneetha BH, Lohith R, Darshan Gowda V, Chandan V, et al. Lip reading with 3D convolutional and bidirectional LSTM networks on the GRID corpus. In: 2024 Second International Conference on Networks, Multimedia and Information Technology (NMITCON); Bengaluru, India; 2024. p. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

25. Jeon S, Kim MS. End-to-end lip-reading open cloud-based speech architecture. Sensors. 2022;22(8):2938. doi:10.3390/s22082938. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Matsui K, Fukuyama K, Nakatoh Y, Kato YO. Speech enhancement system using lip-reading. In: 2020 IEEE 2nd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Engineering and Technology (IICAIET); Kinabalu, Malaysia; 2020. p. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

27. Wang H, Cui B, Yuan Q, Pu G, Liu X, Zhu J. Mini-3DCvT: a lightweight lip-reading method based on 3D convolution visual transformer. Vis Comput. 2025;41(3):1957–69. doi:10.1007/s00371-024-03515-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Ryumin D, Ivanko D, Ryumina E. Audio-visual speech and gesture recognition by sensors of mobile devices. Sensors. 2023;23(4):2284. doi:10.3390/s23042284. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Kim M, Kim HI, Ro YM. Prompt tuning of deep neural networks for speaker-adaptive visual speech recognition. IEEE Transact Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2025;47(2):1042–55. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2024.3484658. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Addarrazi I, Satori H, Satori K. A follow-up survey of audiovisual speech integration strategies. In: Bhateja V, Satapathy SC, Satori H, editors. Embedded systems and artificial intelligence. Singapore: Springer Singapore; 2020. p. 635–43. [Google Scholar]

31. Kim M, Yeo JH, Ro YM. Distinguishing homophenes using multi-head visual-audio memory for lip reading. arXiv:2204.01725. 2022. [Google Scholar]

32. He Y, Seng KP, Ang LM. Generative adversarial networks (GANs) for audio-visual speech recognition in artificial intelligence IoT. Information. 2023;14(10):575. doi:10.3390/info14100575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Li Y, Hashim AS, Lin Y, Nohuddin PNE, Venkatachalam K, Ahmadian A. AI-based visual speech recognition towards realistic avatars and lip-reading applications in the metaverse. Appl Soft Comput. 2024;164(1):111906. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2024.111906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Gao Y, Jin Y, Li J, Choi S, Jin Z. EchoWhisper: exploring an acoustic-based silent speech interface for smartphone users. Proc ACM Interact Mob Wearable Ubiquitous Technol. 2020;4:1–27. doi:10.1145/3411830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Chung JS, Zisserman A. Lip reading in the wild. In: Lai SH, Lepetit V, Nishino K, Sato Y, editors. Computer Vision–ACCV 2016. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2017. p. 87–103. [Google Scholar]

36. Afouras T, Chung JS, Senior A, Vinyals O, Zisserman A. Deep audio-visual speech recognition. IEEE Transact Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2022;44(12):8717–27. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2018.2889052. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Afouras T, Chung JS, Zisserman A. LRS3-TED: a large-scale dataset for visual speech recognition. arXiv:1809.00496. 2018. [Google Scholar]

38. Ahn YJ, Park J, Park S, Choi J, Kim KE. SyncVSR: data-efficient visual speech recognition with end-to-end crossmodal audio token synchronization. arXiv:2406.12233. 2024. [Google Scholar]

39. Wand M, Koutník J, Schmidhuber J. Lipreading with long short-term memory. In: 2016 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); Shanghai, China; 2016. p. 6115–9. [Google Scholar]

40. Ivanko D, Ryumin D, Kashevnik A, Axyonov A, Karnov A. Visual speech recognition in a driver assistance system. In: 2022 30th European Signal Processing Conference (EUSIPCO); Belgrade, Serbia; 2022. p. 1131–5. [Google Scholar]

41. Ma P, Wang Y, Petridis S, Shen J, Pantic M. Training strategies for improved lip-reading. In: ICASSP 2022–2022 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); Singapore: ICASSP; 2022. p. 8472–6. doi:10.1109/ICASSP43922.2022.9746706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Ogri OE, EL-Mekkaoui J, Benslimane M, Hjouji A. Automatic lip-reading classification using deep learning approaches and optimized quaternion meixner moments by GWO algorithm. Knowl Based Syst. 2024;304:112430. doi:10.1016/j.knosys.2024.112430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Ma P, Wang Y, Shen J, Petridis S, Pantic M. Lip-reading with densely connected temporal convolutional networks. In: 2021 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV); Waikoloa, HI, USA; 2021. p. 2856–65. doi:10.1109/WACV48630.2021.00290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. R. PK, Afouras T, Zisserman A. Sub-word level lip reading with visual attention. In: 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); New Orleans, LA, USA; 2021. p. 5152–62. [Google Scholar]

45. Arakane T, Saitoh T, Chiba R, Morise M, Oda Y. Conformer-based lip-reading for japanese sentence. In: Yan WQ, Nguyen M, Stommel M, editors. Image and vision computing. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature; 2023. p. 474–85. [Google Scholar]

46. Pourmousa H, Özen Ü. Lip reading using deep learning in Turkish language. IAES Int J Artifl Intell. 2024;4(13):3250–61. doi:10.11591/ijai.v13.i3.pp3250-3261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Yu C, Yu J, Qian Z, Tan Y. Endangered Tujia language speech recognition research based on audio-visual fusion. In: Proceedings of the 2022 5th Artificial Intelligence and Cloud Computing Conference, AICCC ’22; Osaka, Japan; 2023. p. 190–5. [Google Scholar]

48. Chiu C, Sainath TN, Wu Y, Prabhavalkar R, Nguyen P, Chen Z, et al. State-of-the-art speech recognition with sequence-to-sequence models. arXiv:1712.01769. 2017. [Google Scholar]

49. Chung JS, Senior AW, Vinyals O, Zisserman A. Lip reading sentences in the wild. arXiv:1611.05358. 2016. [Google Scholar]