Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Hybrid Approach for Heavily Occluded Face Detection Using Histogram of Oriented Gradients and Deep Learning Models

1 Department of Computer Systems Engineering, Arab American University, Jenin, P.O. Box 240, Palestine

2 Department of Computer Systems Engineering, Faculty of Engineering and Technology, Palestine Technical University—Kadoorie, Tulkarm, P.O. Box 305, Palestine

3 Department of Computer Science, Birzeit University, Birzeit, P.O. Box 14, Palestine

4 NexoPrima Sdn Bhd, UKM-MTDC, Bangi, 43650, Selangor, Malaysia

5 Information Systems and Business Analytics Department, A’Sharqiyah University (ASU), Ibra, 400, Oman

6 Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, College of Engineering, A’Sharqiyah University (ASU), Ibra, 400, Oman

* Corresponding Author: Thaer Thaher. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Machine Learning and Deep Learning-Based Pattern Recognition)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 144(2), 2359-2394. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.065388

Received 11 March 2025; Accepted 10 July 2025; Issue published 31 August 2025

Abstract

Face detection is a critical component in modern security, surveillance, and human-computer interaction systems, with widespread applications in smartphones, biometric access control, and public monitoring. However, detecting faces with high levels of occlusion, such as those covered by masks, veils, or scarves, remains a significant challenge, as traditional models often fail to generalize under such conditions. This paper presents a hybrid approach that combines traditional handcrafted feature extraction technique called Histogram of Oriented Gradients (HOG) and Canny edge detection with modern deep learning models. The goal is to improve face detection accuracy under occlusions. The proposed method leverages the structural strengths of HOG and edge-based object proposals while exploiting the feature extraction capabilities of Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs). The effectiveness of the proposed model is assessed using a custom dataset containing 10,000 heavily occluded face images and a subset of the Common Objects in Context (COCO) dataset for non-face samples. The COCO dataset was selected for its variety and realism in background contexts. Experimental evaluations demonstrate significant performance improvements compared to baseline CNN models. Results indicate that DenseNet121 combined with HOG outperforms other counterparts in classification metrics with an F1-score of 87.96% and precision of 88.02%. Enhanced performance is achieved through reduced false positives and improved localization accuracy with the integration of object proposals based on Canny and contour detection. While the proposed method increases inference time from 33.52 to 97.80 ms, it achieves a notable improvement in precision from 80.85% to 88.02% when comparing the baseline DenseNet121 model to its hybrid counterpart. Limitations of the method include higher computational cost and the need for careful tuning of parameters across the edge detection, handcrafted features, and CNN components. These findings highlight the potential of combining handcrafted and learned features for occluded face detection tasks.Keywords

Recent improvements in computing hardware (e.g., Graphics Processing Units (GPUs)) and sensor technologies (e.g., depth cameras and Infrared (IR) sensors) have enabled more efficient implementation of vision-based tasks, including face detection [1,2]. Many research efforts and commercial systems now integrate face detection to support real-time human-computer interaction (HCI) through applications such as facial authentication, gaze tracking, and affective computing [3,4]. These systems use cameras to observe and microphones to listen, allowing machines to interpret visual and auditory inputs and respond in task-relevant ways. Face detection is a crucial technology for achieving natural human-computer interaction (HCI). It is specifically a basic task in computer vision that is commonly used in surveillance, identity verification, and other applications. Essentially, face detection involves figuring out if there are any faces in an image and distinguishing them from non-face objects such as landscapes or buildings. If faces are found, it also identifies where they are located and how big they are in the image [5,6]. Face detection is a crucial component of many facial analysis systems and serves as the initial step for various applications, including face alignment, landmark detection, modeling, recognition, verification, head pose tracking, expression analysis, and age or gender estimation. These tasks are significant in improving the ability of computers to comprehend the behavior, emotions, and intentions of humans [7–9].

Face detection has made significant progress, but there are still some issues to be solved [10]. Other factors such as the scale, illumination condition, pose, facial expression, and image quality also pose some challenges to the detection process. Among these factors, occlusions are particularly difficult because they can obscure the critical facial components [11]. In this case, some other objects, parts of the human body, or accessories, such as masks and sunglasses, cover a part of the face [12]. Conventional approaches are based on the recognition of these features, but if they are occluded, then the system will fail, which may result in the failure of detection or a high false positives rate [13]. This is a major issue in real-time applications like surveillance and security where accuracy is critical.

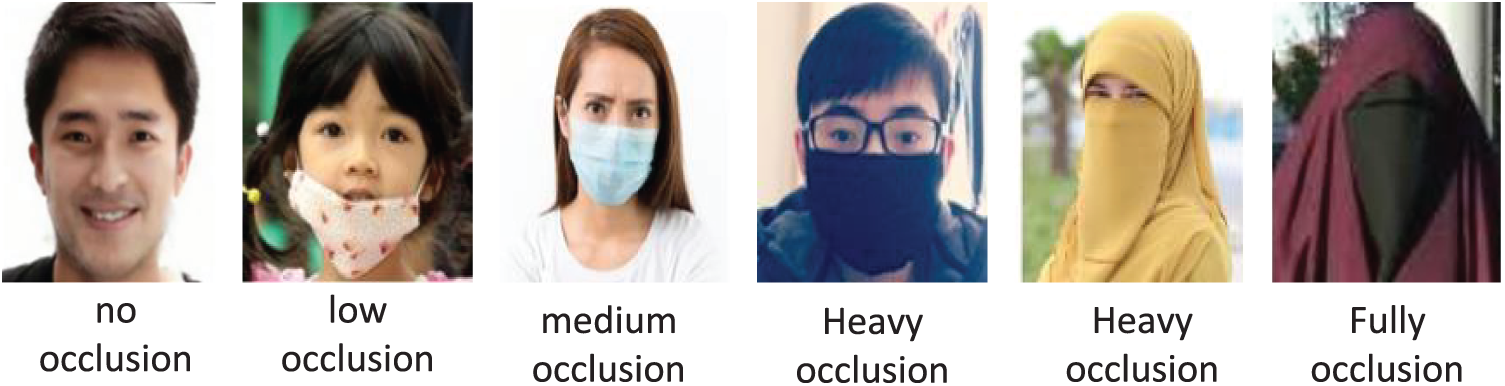

Furthermore, the variability in terms of size and location of the occlusions increases the level of difficulty. The size, shape, and texture of the occlusions can be quite diverse and they can occur at different positions [7,12]. Such variability is usually responsible for the heuristic failures or biases in the traditional face detection models which work under the assumption of fixed topology of the faces. As shown in Fig. 1, occlusions can range from partial to severe, depending on the extent of facial coverage. Researchers typically categorize occlusions into non-occluded, partially occluded, and severely occluded types based on the percentage of facial coverage [10,14].

Figure 1: Samples of different occlusion levels. The images are sourced from publicly available benchmark datasets [12,15]

Real-world applications often involve scenarios where faces are not fully visible. For instance, in surveillance systems, individuals may wear accessories or coverings that obscure facial features, leading to misdetections or missed detections [16,17]. Recent events, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, have further highlighted the need for effective face detection systems capable of handling occlusions caused by masks [18]. Furthermore, in some Muslim countries, many women choose to wear the niqab, a traditional face-covering worn for religious reasons. The niqab, also known as the burqa or khimar, covers most or all of the face, making facial features difficult to detect [19]. Fig. 1 illustrates examples of Muslim women wearing the niqab, where their faces are largely hidden. Since the niqab fully or partially obscures the face, it creates a significant challenge for face detection systems, similar to other forms of occlusion. Many existing models perform well on fully visible faces but struggle when parts of the face are hidden, necessitating more robust solutions.

These challenges highlight the unique difficulties of detecting occluded faces compared to regular face detection. Accordingly, the motivation behind this research is to develop more advanced face detection systems capable of handling the diverse and unpredictable conditions found in real-world scenarios, with a particular focus on heavily occluded faces caused by traditional coverings such as niqabs worn by Muslim women and other veils commonly used for cultural or religious reasons.

To this end, several approaches have been proposed. At the early stage, hand-crafted features like Haar-like features and Local Binary Patterns (LBP) were used to recognize the facial characteristics. Another commonly employed method was the Histogram of Oriented Gradients (HOG), which works on the premise of edge orientations and gradient distributions to detect faces. These hand-crafted features were generally used in conjunction with machine learning methods like Support Vector Machines (SVM) or Adaptive Boosting (AdaBoost) for classification [16,20]. However, such approaches were quite efficient in the controlled environment but failed to perform effectively in varying conditions of pose, lighting, and occlusion. With the development of deep learning, and especially Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), the face detection performance has been improved [21]. At present, most CNN-based approaches are used due to their ability to learn hierarchical features from data and, therefore, they are more robust to occlusions and variations [19]. As opposed to conventional methods, CNNs have the ability to directly analyze raw image data and identify significant patterns without requiring manually constructed features. They have been considered the preferred approach for the majority of face detection applications, particularly in challenging conditions such as occlusion.

Despite current advances, there are still limitations, particularly when detecting faces with severe occlusion. State-of-the-art methods often struggle with unpredictable occlusion patterns, making hybrid approaches increasingly relevant. This paper proposes a hybrid face detection framework that integrates HOG features, which capture local edge and texture patterns, with feature maps extracted from CNNs. To enhance localization further, Canny edge detection is employed to refine object proposal bounding boxes based on contours. This design leverages the complementary strengths of handcrafted features (HOG and edge-based cues) and learned features (CNNs), aiming to boost precision and reduce false positives in scenarios involving masked or partially occluded faces. This approach is motivated by the observation that handcrafted methods are effective in highlighting facial structure under noise or occlusion, while CNNs provide robust abstraction from data through hierarchical feature learning. By combining both, the proposed model enhances feature representation and improves detection reliability across complex, real-world cases. To sum up, the main contributions of this study are as follows:

1. Comprehensive evaluation of six CNN-based models, namely, Densely Connected Convolutional Network (DenseNet121), Residual Networks (ResNet50, ResNet101, and ResNet152), and Visual Geometry Group Networks (VGG16 and VGG19), for detecting occluded faces.

2. Development of a hybrid face detection framework that combines handcrafted HOG features and contour-based object proposals using Canny edge detection with CNN-based feature extraction to improve robustness under heavy occlusion.

3. Evaluating both basic and enhanced models on a highly challenging dataset that includes heavily occluded faces covered with niqabs and veils to assess robustness and accuracy.

4. Quantitative comparison of baseline and hybrid models, showing that the proposed method significantly enhances classification performance (e.g., improving precision from 80.85% to 88.02% in DenseNet121).

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews related work on face detection under occlusions. Section 3 presents the research background, including HOG, Canny, and the CNN models used in this study. Section 4 describes the proposed hybrid models. Section 5 presents the experimental setup, results, and discussions. Section 6 identifies key challenges in occluded face detection and explores directions for future work. Section 7 concludes the paper by summarizing key findings and contributions.

Face detection in occluded situations is a major challenge in the field of computer vision. Faces can be hidden by masks, glasses, objects in the environment, or other random obstacles, making recognition more difficult. To tackle this, researchers have been working on advanced solutions, such as improving deep learning models, using surrounding context, and enhancing methods for retrieving important features. The goal is to develop better models that can detect faces correctly even when they are almost fully covered and work effectively in real-life scenarios.

Face detection under occlusion intersects with multiple research areas in artificial intelligence (AI), including facial expression recognition, explainable AI (XAI), and occlusion-robust face recognition. For example, Manresa-Yee et al. [22] emphasized the importance of interpretability in expression recognition by applying XAI techniques to explore how gender differences affect the learning process of facial expression models. Their work highlights how facial regions contribute differently to classification outcomes across expressions and genders. Similarly, Anil et al. [23] conducted a comprehensive survey on face recognition under occlusion, outlining the technical challenges and reinforcing the need for more robust detection strategies in real-world scenarios. These studies demonstrate that face detection is not an isolated task but part of a broader AI ecosystem that benefits from progress in interpretability, expression modeling, and multimodal understanding. In this paper, we contribute to this landscape by focusing on heavily occluded face detection and proposing a hybrid method that integrates handcrafted edge features with deep feature extraction. Our approach is designed to enhance detection under challenging conditions and support downstream tasks such as expression analysis and identity verification.

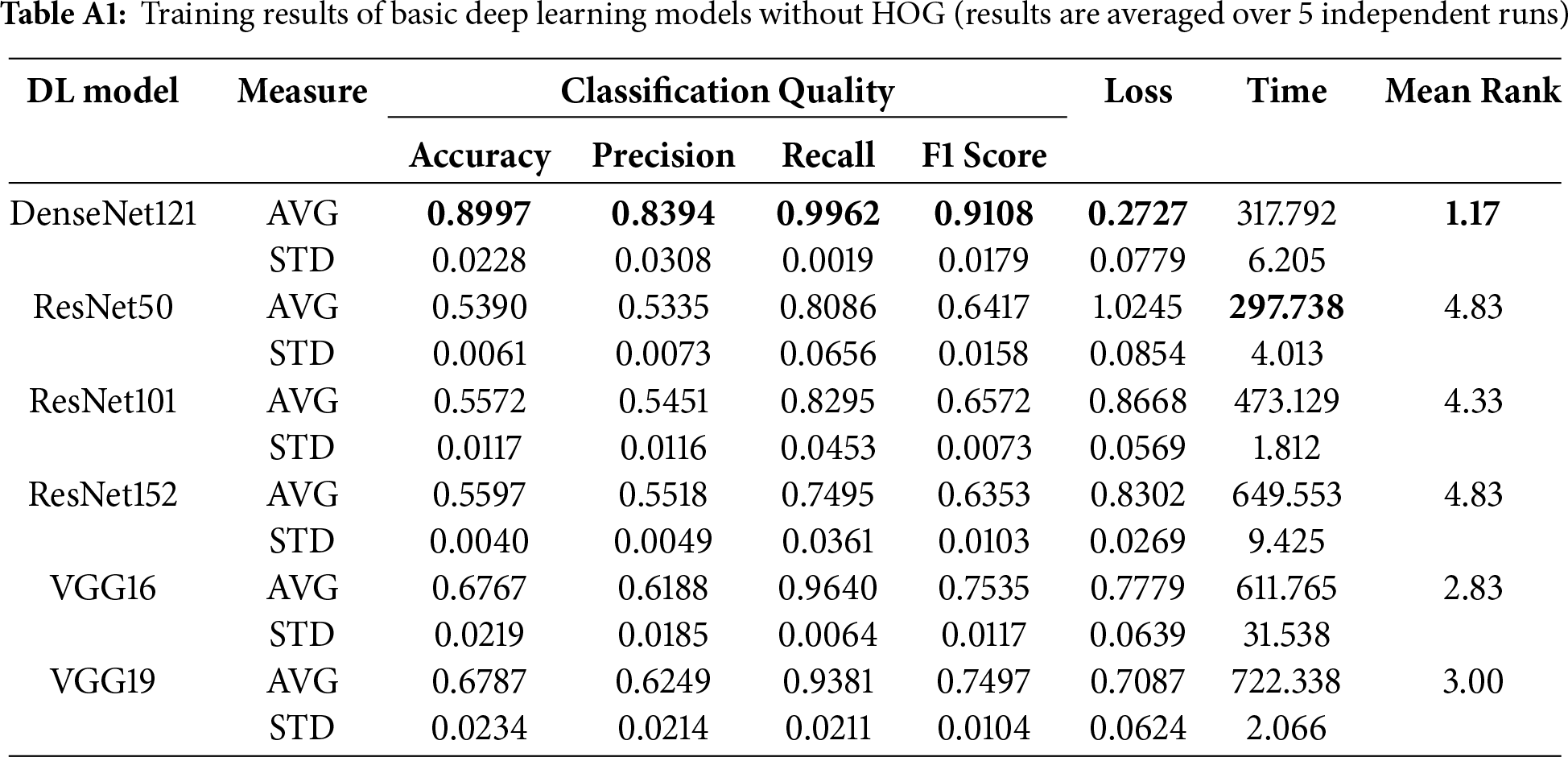

The rest of this section provides an overview of the major developments in face detection under occlusions. These methods are categorized into three main groups: (1) traditional feature-based methods, (2) learning-based approaches (including machine learning and deep learning techniques), and (3) hybrid techniques that integrate multiple strategies. By reviewing and comparing different approaches, we highlight key advancements, limitations, and ongoing challenges in this research domain.

The initial approaches of face detection used hand-crafted features like Haar-like features, Local Binary Patterns (LBP), and HOG. These feature-based techniques identify and evaluate patterns, including edges, textures, and spatial relationships, by extracting handcrafted features from face regions. While a combination of these techniques is efficient in detecting faces under ideal conditions, they struggle in the presence of occlusions because they rely on complete facial shapes. A method using an Adaboost cascade classifier with Haar-like features was proposed in [20] for occluded face detection. It utilized facial feature relationships, such as the eye-mouth distance, to locate faces even with significant occlusions. Evaluated on the Masked Faces (MAFA) dataset, which includes faces covered by masks, sunglasses, hats, and scarves, it achieved a 57.3% detection rate, outperforming Adaboost (26%) and Seetaface (46%). However, with a 4.7% false positive rate, it faced precision challenges in complex occlusions. Addressing the detection of partially occluded faces, Bade and Sivaraja [24] suggested a modified cascade-based framework based on Viola and Jones’ Haar cascade classifier. To enhance the accuracy and decrease the computational time, the authors incorporated heuristic boosting optimization and tuned the decision tree. The method was tested on a subset of the WIDER FACE dataset. The optimal tree depth (n = 3) was chosen to achieve the best F1 score without overfitting. The result demonstrated that the proposed method has 65.25% accuracy and 77.17% F1 score, which is better than Haar-frontal face-default and Haar-frontal face-alt by 23.66% and 21.7%, respectively, for partially occluded faces. However, the method showed limitations in extreme occlusions and profile faces. A geometric feature-based method was proposed by Ganguly et al. [25]. In this paper, they presented two methods for detecting occlusions in 3D face images: a Threshold-based method and a Block-based method. Both used depth information by transforming the 3D images to 2.5D range images. The threshold-based method detected the occlusions by localizing the protruding regions from the nose region. The block-based method, on the other hand, inspected the depth variation using sliding blocks (3 × 3 and 5 × 5). The proposed methods were evaluated on the Bosphorus database, and the accuracy of the methods was 91.79% and 99.71%, respectively. Nevertheless, the methods had a disadvantage in dealing with transparent occlusions such as glasses, and also with irregularly shaped objects because of the fixed block sizes.

Learning-based methods, especially deep learning, have emerged as promising approaches to detecting hidden faces. Several works have emerged in this context. Ensemble and boosting methods help improve face detection by combining multiple classifiers to boost accuracy and handle occlusions. AdaBoost is commonly used to strengthen weak classifiers. In 2015, Gul and Farooq [26] improved face detection in crowded scenes using AdaBoost with free rectangular features. They trained two separate classifiers: one for full faces and another for partially occluded ones, along with a skin color detection step to reduce false positives. To enhance the detection of occlusions in crowded surveillance scenes, Arunnehru et al. [27] proposed Segmentation-Based Fractal Texture Analysis (SFTA) with tree-based classifiers (Random Forest and J48 Decision Tree). The findings demonstrated high accuracy but struggled with extreme occlusions. Liao et al. [28] developed a faster, more robust detector using Normalized Pixel Difference (NPD) features combined with AdaBoost and deep quadratic tree learning. Their method improved detection speed and accuracy in challenging conditions. While these approaches handled occlusions better, they still relied on handcrafted features, making them less adaptable to complex real-world cases.

Support Vector Machines (SVMs) have been employed for face detection under occlusion conditions in many applications. Many studies have been conducted on SVM based methods that have used different feature extraction and preprocessing steps for improved detection. For example, studies in [29–32] employed SVM with different features to enhance the performance in the occluded regions. Although these approaches prove that SVM is suitable for dealing with occlusions, they have poor computational complexity and flexibility to the type of occlusions. This limitation shows that there is a need to explore other sophisticated approaches that can provide the right balance between accuracy and computational time.

Over the past few years, deep neural network models have been proposed to address the problems of occlusion-based face detection. These approaches are successful, especially in unconstrained environments, by using pre-trained networks such as VGG16, ResNet, You Only Look Once (YOLO), or custom architectures for occlusion. Many also incorporate improvements like attention mechanisms, multi-task learning, and context-sensitive processing to increase the accuracy and flexibility. In recent studies, the feature representation is enhanced, and attention theory is applied in the process of occluded face detection. Zhang et al. (2022) [33] designed an improved RetinaNet with an attention mechanism and got favorable performance on the MAFA dataset. Qi et al. (2024) [34] improved YOLOv5 with improved YOLOv5 with Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) and focal loss, which improved the performance on WIDER Face and AIZOO datasets. There are other researchers who have suggested the use of multi task learning strategies. In 2021, Batagelj et al. [35] presented a two-stage method for face detection and mask compliance classification. RetinaFace was proposed for detection and ResNet-152 for classification. However, this approach had some drawbacks which were mainly related to high computational complexity.

To detect partially occluded faces, Tsai et al. [36] proposed a multi-scale learning approach that combines the Single Stage Headless (SSH) face detector with VGG16. Their model had multiple detection branches and a context module to achieve high accuracy at low computational cost. To improve the detection of partial and heavily occluded faces, context-aware approaches have been investigated. Alashbi et al. [37] introduced the Niqab-Face dataset and a CNN-based model that uses contextual facial information to detect heavily occluded faces and shows that existing detectors fail in extreme occlusions. In a separate work, they proposed the Occlusion-Aware Face Detector (OFD) [19], which improves Darknet-53 with contextual information such as head pose and body features.

2.3 Hybrid Methods for Occluded Face Detection

This section covers approaches that combine multiple techniques to address the occlusion problem. In [17], head localization, Bayesian tracking, and a cascaded classifier (skin color analysis and AdaBoost-based face template matching) were integrated for Automated Teller Machine (ATM) surveillance. Mahbub et al. [38] introduced Regression-based User Image Detector (DRUID), a deep regression-based method that avoids proposal generation using a regression loss function for more efficient face detection. Balasundaram et al. [39] integrated Viola-Jones for feature extraction, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) for dimensionality reduction, and SVM for classification and used pivotal points (eyes, nose, mouth) to judge occlusions. Another study by [16] combined Haar Cascade, Local Binary Pattern Histograms (LBPH), and SVM to enhance detection in low-resolution surveillance videos. To enhance the detection in extreme conditions such as heavy occlusions, poor lighting, and low resolutions, Zhu et al. [40] proposed CMS-RCNN that employed Multi-Scale Region Proposal Networks (MS-RPN) and Contextual Multi-Scale CNN (CMS-CNN) to incorporate both facial and body contexts. It obtained superior accuracy on the WIDER Face and Face Detection Data Set and Benchmark (FDDB) datasets but was computationally expensive and failed in densely crowded scenes. Shin and Kim in [41] combined discriminative and generative techniques to improve the detection and tracking of the features with occlusions and pose changes. The model used RANSAC and multi-view detection to figure out the pose and improved the features by reducing appearance errors both locally and globally. A shape-weighting matrix was used to prevent the exclusion of relevant features. These hybrid methods prove effective by leveraging the advantages of multiple techniques; however, challenges in handling complexity, computational efficiency, and real-world adaptability are still an issue.

Although significant progress has been made in face detection, processing heavily covered faces, such as those occluded by niqabs or other traditional veils, remains a challenge, particularly due to the limitations of current approaches under extreme occlusions. To better highlight the distinctions between major categories of face detection methods and how they perform under such conditions, a summary table is provided in Table 1, which presents a comparison of representative methods, outlining their primary advantages and limitations.

One promising direction to improve robustness is the development of hybrid models that combine handcrafted features with deep learning. Classical edge detection and texture-based methods capture essential structural information, while deep models offer rich hierarchical feature representations. However, existing research in this hybrid domain remains limited, leaving room for further exploration. Therefore, this paper suggests a hybrid model that combines HOG and Canny edge detection with advanced deep learning architectures. This combination utilizes handcrafted methods to preserve edge and texture information and CNN for advanced feature learning. To check the robustness and precision of the suggested model, it is tested on a challenging dataset that has heavily occluded faces covered by niqab and veil, where the level of facial coverage is between 50% and 90% or even more. This work aims to address the observed performance gap and contribute to more reliable detection of heavily occluded faces.

In this section, an overview of techniques and tools employed in the proposed method is described. Included is an exploration of deep learning models identified in this study; an explanation of the Histogram of Oriented Gradients (HOG) method; and, an overview of the original Canny operator.

3.1 Histogram of Oriented Gradients (HOG) for Feature Extraction

Feature extraction is a key step in both image processing and machine learning. Its main goal is to simplify the data by discovering and selecting the most important features that are relevant to the task while removing unnecessary or redundant information. From the meaningful parts of the data, feature extraction reduces complexity, increases the speed of processing, and results in enhanced performance of the machine learning models for effective decision making [42]. For example, in image processing tasks, features such as edges, shapes, and textures are extracted to effectively represent image content [43]. Feature extraction plays a vital role in applications such as object detection, face recognition, and image classification, where raw pixel data can be heavy and inefficient to process directly. Instead, extracting informative features allows models to work more efficiently and accurately.

The HOG technique is one of the well-recognized feature extraction methods used to capture the structure and shape of objects in images. Introduced by Dalal and Triggs in 2005, HOG was one of the most powerful hand-crafted features in computer vision, especially for detection tasks, before data-driven methods like Alex Network (AlexNet), Residual Network (ResNet), and U-shaped Convolutional Network (U-Net) became dominant [44]. HOG is widely recognized for its strong performance and straightforward computation. It is often the preferred choice in many applications because it provides a good balance between accuracy and complexity [45].

The HOG was inspired by the Scale-Invariant Feature Transform (SIFT) method, which is commonly used for detecting key features in images. A schematic representation of the HOG process can be found in [42]. The algorithm is further explained in the following steps.

1. Preprocessing: This step aims to normalized the input image to a certain size to ensure consistency. It is then converted to grayscale to make the processing easier

2. Gradient computation: In this step, The image is divided into small sections called cells and then gradient magnitude and direction are calculated for every pixel. The direction is usually quantized to one of four angles: 0°, 45°, 90° and 135°.

3. Histogram computation: This process aims to create a histogram for every cell to store the information about the gradient directions. This helps in identifying edge patterns which are important in defining the shape and structure of objects in the image

4. Normalization: To reduce the effect of lighting and shadows, the histogram values are manipulated. In this case, each histogram is divided by the total gradient magnitude of all the histograms. This makes the features more robust to changes in lighting conditions

5. Concatenation of feature vector: Last, all the normalized histograms are concatenated to form a single feature vector. This vector is then used as an input for the classifiers to recognize objects based on the information it contains about the image.

3.2 Deep Learning Models Explored in the Study

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is applied to simulate intelligent human behavior and decision-making [46]. Deep learning is a particular component of AI that mimics the human thought process and problem-solving. Machine learning techniques perform pattern recognition and prediction in the field of AI. Nevertheless, traditional machine learning is not effectively addressing problems related to complex or unstructured data [47]. This is because deep learning has multiple layers of processing called neural networks, which simulate neurons in the human brain [48]. The above technique is very useful in the detection of patterns and relationships in the data and is thus convenient in image, audio, and text analysis.

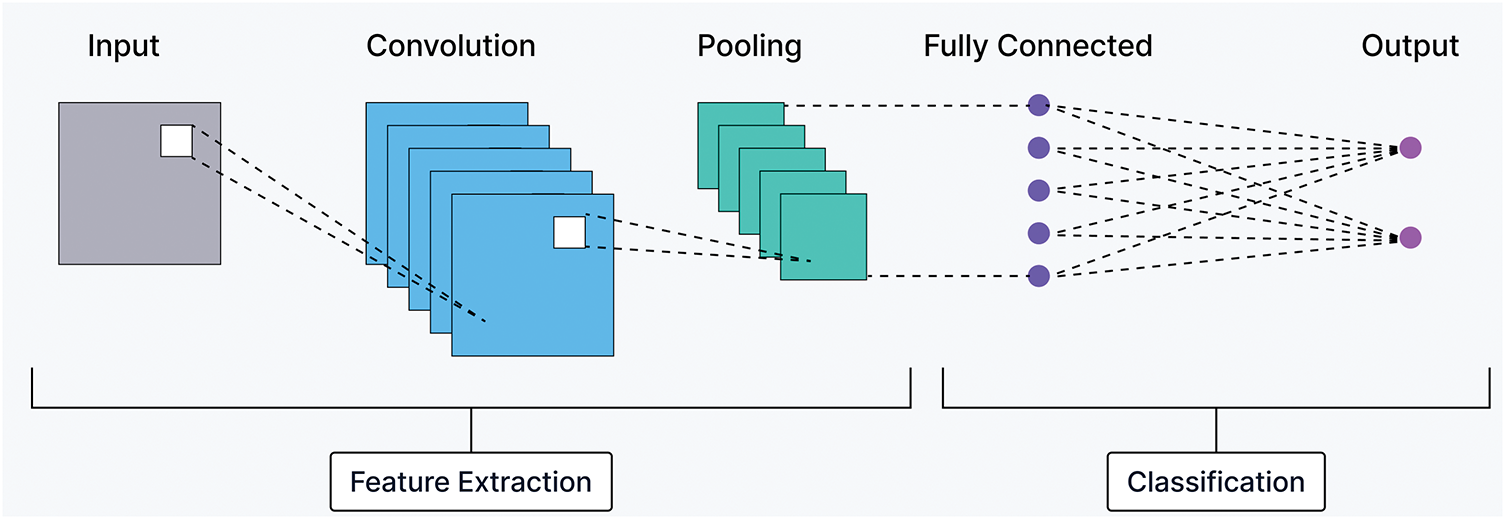

Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) is a deep learning model that was introduced by LeCun in 1989 to handle visual data [49]. CNN is essentially inspired by artificial neural networks (ANNs). It can process images by identifying patterns such as edges, shapes, and textures through layers of filters. CNNs are used successfully in various applications such as image classification, object detection, and face recognition and are the foundation of many advanced models. They work by extracting hierarchical features from images using layers specifically designed for spatial feature extraction while maintaining low computational costs. In its basic form, CNN consists of three types of layers: Convolutional (CONV) layers, Pooling (POOL) layers, and Fully connected (FC) layers. Precisely, CNN consists of numerous CONV layers preceding sub-sampling POOL layers, while the ending layers are (FC) layers. Fig. 2 depicts the architecture of the basic CNN.

Figure 2: Schematic diagram of a basic CNN architecture. The figure outlines the typical components of CNNs, including convolutional, pooling, and fully connected layers, which form the foundation of the deep learning models explored in this study

1. Convolutional Layer: This layer applies learnable filters called kernels to extract features from input images. Each filter detects specific patterns, and sliding these filters over the image generates feature maps. In contrast to traditional computer vision methods, where filters are manually designed, CNNs can automatically learn these filters by adjusting their weights through a backpropagation process, when provided with sufficient training data [50,51].

2. Pooling Layers: Added between convolutional layers, pooling reduces the size of feature maps while retaining important information. It minimizes redundancy, decreases computational costs, and controls overfitting by progressively reducing the spatial dimensions (height and width) without affecting depth. Max pooling selects the highest value in a region, while average pooling computes the average. As shown in Fig. 2, convolutional and pooling layers form the feature extraction part of a CNN model [52].

3. Fully Connected Layer: The FC layer is similar to the one used in traditional ANNs. In this layer, each neuron is linked to every neuron in the previous layer, which is why it’s called fully connected or dense. It is typically placed at the end of a CNN model. The FC layer receives input from the feature extraction part of the CNN, where the data has been flattened into a smaller, simplified form of the original input [53]. Its main job is to act as the classifier, making predictions based on the features extracted earlier.

CNNs learn spatial hierarchies of features through training algorithms and activation functions, automatically adapting to patterns in the data. Their ability to handle complex visual inputs and maintain efficiency makes them essential for tasks like face detection, especially under challenging conditions like occlusion.

3.2.2 DL Models Based on CNN Backbone

Several deep learning models have been developed based on CNN architectures as their backbone. These models leverage CNNs for feature extraction while introducing advanced structures to improve performance. Popular CNN-based models include DenseNet [54], Residual Networks (ResNet) [55], and VGG [51], which are widely used in image classification, object detection, and face recognition tasks. The following sections briefly introduce these models and highlight their key features.

• DenseNet121: It is one of the implementations of the DenseNet network with 121 layers, including convolutional, pooling, and fully connected layers. DenseNet is a CNN model designed with dense connections between layers. Unlike traditional networks, each layer in DenseNet connects to every other layer, which enables better reuse of features and a smoother flow of information [54]. This design reduces the risk of losing important data as it moves through the network. As a result, DenseNet121 achieves strong performance while using fewer parameters. Its efficient design makes it ideal for tasks that require deep feature extraction with lower computational costs [56].

• ResNet Models (ResNet50, ResNet101, ResNet152):ResNet models introduce the concept of residual learning to handle the problem of vanishing gradients in very deep networks. Instead of directly learning the output, ResNet layers learn residuals (the difference between input and output), which simplifies training and improves performance [55]. ResNet50 is a moderately deep network with 50 layers, offering a good balance between computational efficiency and performance [57]. ResNet101 increases the depth to 101 layers, allowing it to learn more complex patterns and features in the data. For tasks requiring even greater feature extraction, ResNet152 goes deeper with 152 layers, capturing more detailed patterns at the cost of higher computational requirements [58]. These variations provide flexibility to choose the right depth based on the complexity of the problem and available resources.

• VGG Models: VGG models are among the earliest CNN architectures that achieved remarkable performance in image recognition tasks. They focus on simplicity, using 3

3.3 Canny Edge Detection for Object Proposals

Image processing is the application of algorithms and mathematical models for further analysis. The main aim of image processing is to improve the quality of images, get meaningful information, and automate image-based tasks. One of the most important parts of this process is to find the edges of the image that are the sudden changes in brightness of neighboring pixels [60]. Edges are significant features as they give an idea about shape and objects’ contours and hence form an important part of object detection and recognition. These techniques are widely used in image analysis to locate these boundaries accurately [61].

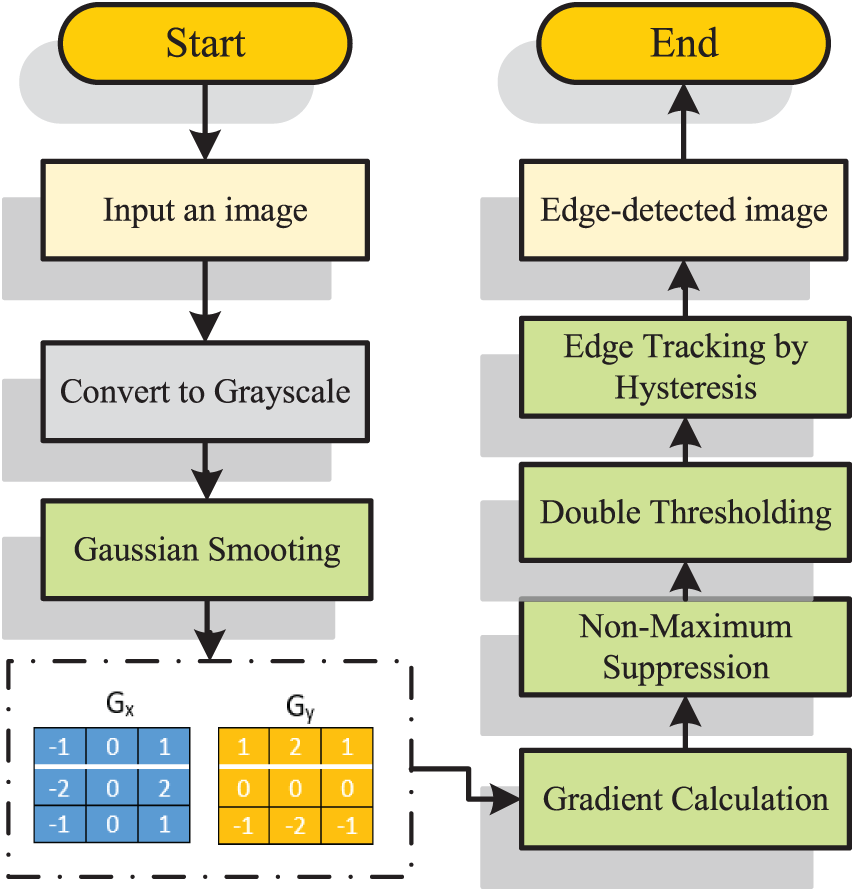

The Canny edge detection is a technique for finding edges of an image which is a very common technique in image processing. It was introduced by John Canny in 1986 and has become a standard method because of its short operation time and relatively simple calculation process [62–64]. This technology functions by searching for sudden changes in the brightness intensity of the area which often occurs at the object’s boundaries. The process of the Canny operator is illustrated in Fig. 3 which consists of the following steps:

Figure 3: Canny edge detection process. The flowchart summarizes the key steps of the Canny algorithm, from noise reduction to edge tracking. This process supports object proposal generation for better localization of occluded faces

1. Noise reduction: A Gaussian filter smooths the image to reduce noise. The first order Gaussian function is mathematically defined as:

where

2. Gradient calculation: The gradients (changes in intensity) are computed to highlight regions with sharp intensity variations, which are likely to be edges. The intensity gradient in the image is calculated using the partial derivatives of the image. This is often achieved by applying

The gradient direction

3. Non-maximum suppression: After calculating gradients, non-maximum suppression is applied to refine the detected edges. This step thins the edges by keeping only the local maxima along the gradient direction to ensure that edges are sharp and well-defined. This step is applied by comparing the gradient magnitude of each pixel with the magnitudes of its neighboring pixels along the gradient direction. For a pixel to be retained as an edge, its gradient magnitude must be greater than both neighbors along the gradient direction. Mathematically, a pixel at position

where

4. Double thresholding: In this step, potential edges are classified as strong or weak edges based on thresholds. Two thresholds,

• Pixels with intensity values above

• Pixels with intensity values between

• Pixels with intensity values below

5. Edge tracking by hysteresis: The final step ensures continuity of edges. Weak edges connected to strong edges are preserved, while isolated weak edges are discarded. This process effectively preserves true edges while removing noise or disconnected weak edges, which ensures the final output has continuous and well-defined edges.

Eqs. (1) through (4) describe the standard steps of the Canny edge detection process, a widely used method for edge localization in computer vision. In our model, these steps help generate accurate object proposals by identifying strong edge regions, which are likely to contain occluded faces. Gradient magnitude and direction (Eqs. (2) and (3)) support precise edge refinement through non-maximum suppression (Eq. (4)), leading to compact and relevant candidate regions for further analysis by the hybrid model.

3.3.1 Using Canny for Object Proposals

Although Canny edge detection is primarily designed to detect edges, it can be adapted to generate object proposals by grouping edges into closed contours or regions. After detecting edges, contour-finding algorithms (e.g., Suzuki and Abe [65]) can extract connected components or regions that may correspond to objects. In the context of occluded face detection, Canny edge detection can serve as a preprocessing step to identify potential regions where faces might exist. These regions, also called candidate proposals, can then be further analyzed using more advanced feature extraction techniques, such as HOG and deep learning models.

4 Proposed Methodology for Occluded Face Detection

In this part, the methodology suggested to design the occluded face detection model is explained. First, in Section 4.1, the datasets that are employed for training and testing are defined. Then, in Section 4.2, the main components of the hybrid pipeline proposed in this paper are introduced, and the way feature extraction, object proposal, and classification are implemented is described. It also presents the description of the algorithm and represents the workflow with the help of diagrams. Finally, in Section 4.3, the measures used to quantify the effectiveness of the proposed model are discussed.

In order to train a deep-learning CNN model for face detection, we need a large and diverse dataset. The quality of the dataset is crucial for the model’s performance and accurate annotations are needed for reliable results [19]. For this study, two datasets were chosen to support the detection of occluded faces and enhance classification accuracy.

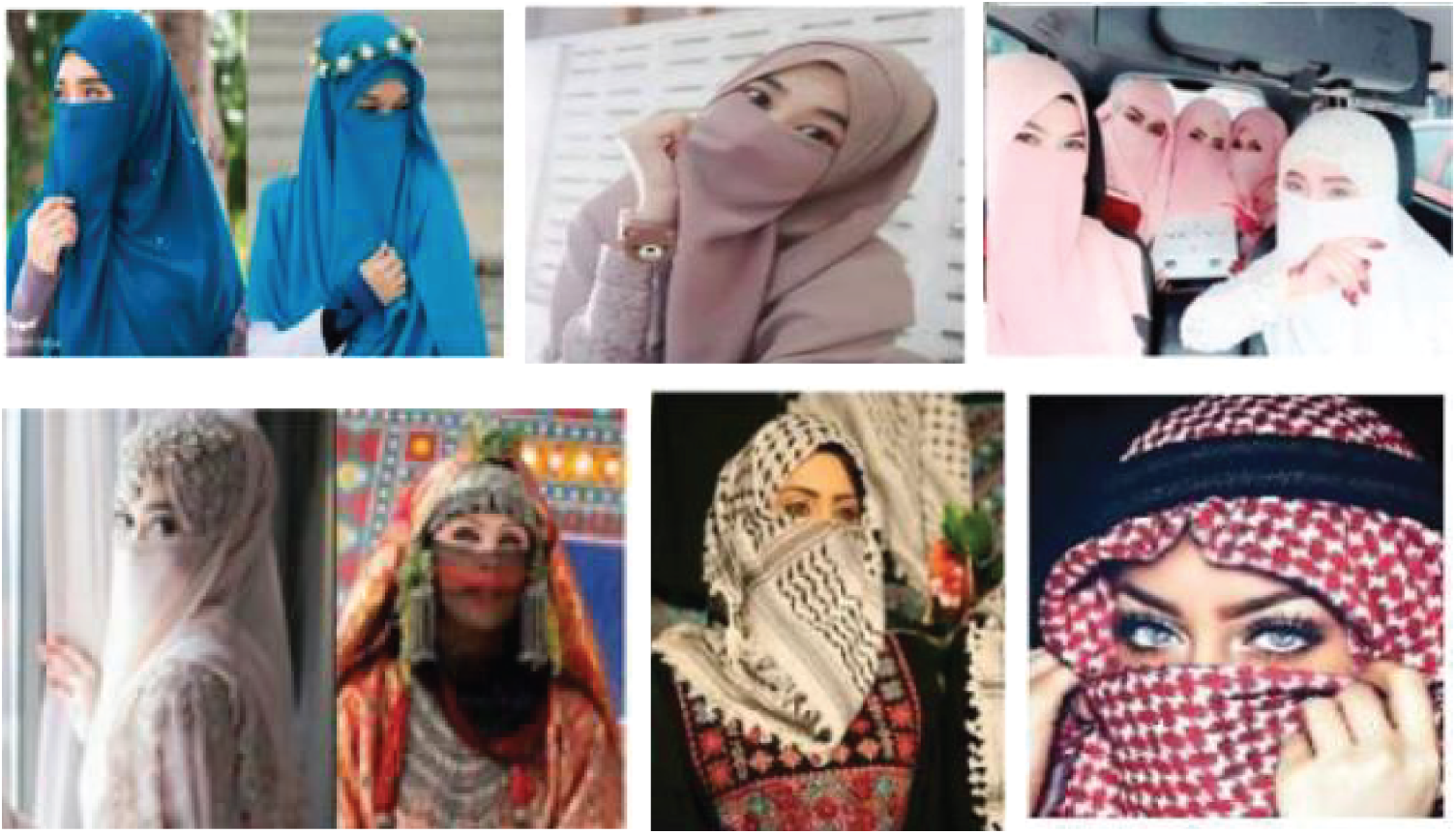

In this study, we used the Niqab dataset, which is designed specifically for detecting faces that are heavily covered, such as those wearing niqabs, veils, or masks [11,15,19]. The dataset contains 10,000 images with around 12,000 faces, where more than 50% of the faces are highly occluded, leaving only the eyes visible. A sample of 5175 images, containing 5343 faces, was employed in this study. These samples were sourced directly from the authors of the original dataset. Fig. 4 illustrates examples of extensively covered faces in different styles of niqabs and veils, demonstrating the diversity of occlusions present in the dataset. Most of the existing face detection models have given less attention to contextual information. However, factors like the head, its pose, and shoulders can be crucial for detecting heavily occluded faces due to the lack of visual information [66]. Accordingly, each image in the Niqab dataset was carefully labeled with bounding boxes using a contextual-labeling technique, which includes not only the visible parts of the face but also surrounding areas. Fig. 5 compares images labeled without contextual information (focusing only on visible face regions) and images labeled with contextual information (including surrounding regions). Contextual labeling helps the model learn additional features, improving detection accuracy, especially for occluded faces [19,40].

Figure 4: Samples of heavily covered faces from the niqab dataset. The figure shows different styles of niqabs and veils used in the dataset, highlighting the diversity and challenge of detecting highly occluded faces

Figure 5: An occluded face (a) with no contextual information and (b) with contextual information

4.1.2 COCO Dataset (Common Objects in Context)

In addition to the Niqab dataset, we included a subset of the COCO dataset [67], which contains 5072 non-face images. This number was chosen to make the training data roughly balanced between face and non-face samples. This subset was added for classification purposes to help the model distinguish between facial and non-facial regions, reducing false positives during detection [32]. According to [7], the inclusion of non-face images is particularly important for evaluating how well a face detector can ignore images without faces and for analyzing the algorithm’s tendency to produce false positives.

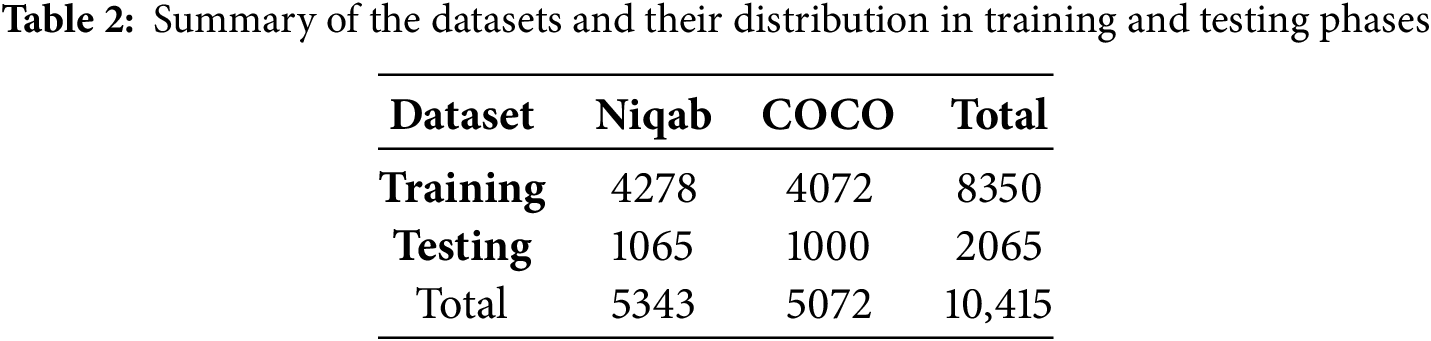

The combined dataset, consisting of a total of 10,415 images, is divided into training and testing sets, with 80% of the images used for training and validation, and 20% for testing. The primary criteria and constraints influencing dataset selection included the degree of occlusion, label quality, class balance (face vs. non-face), and real-world relevance. Table 2 provides a summary of the number of images in each dataset and their distribution across the training and testing phases.

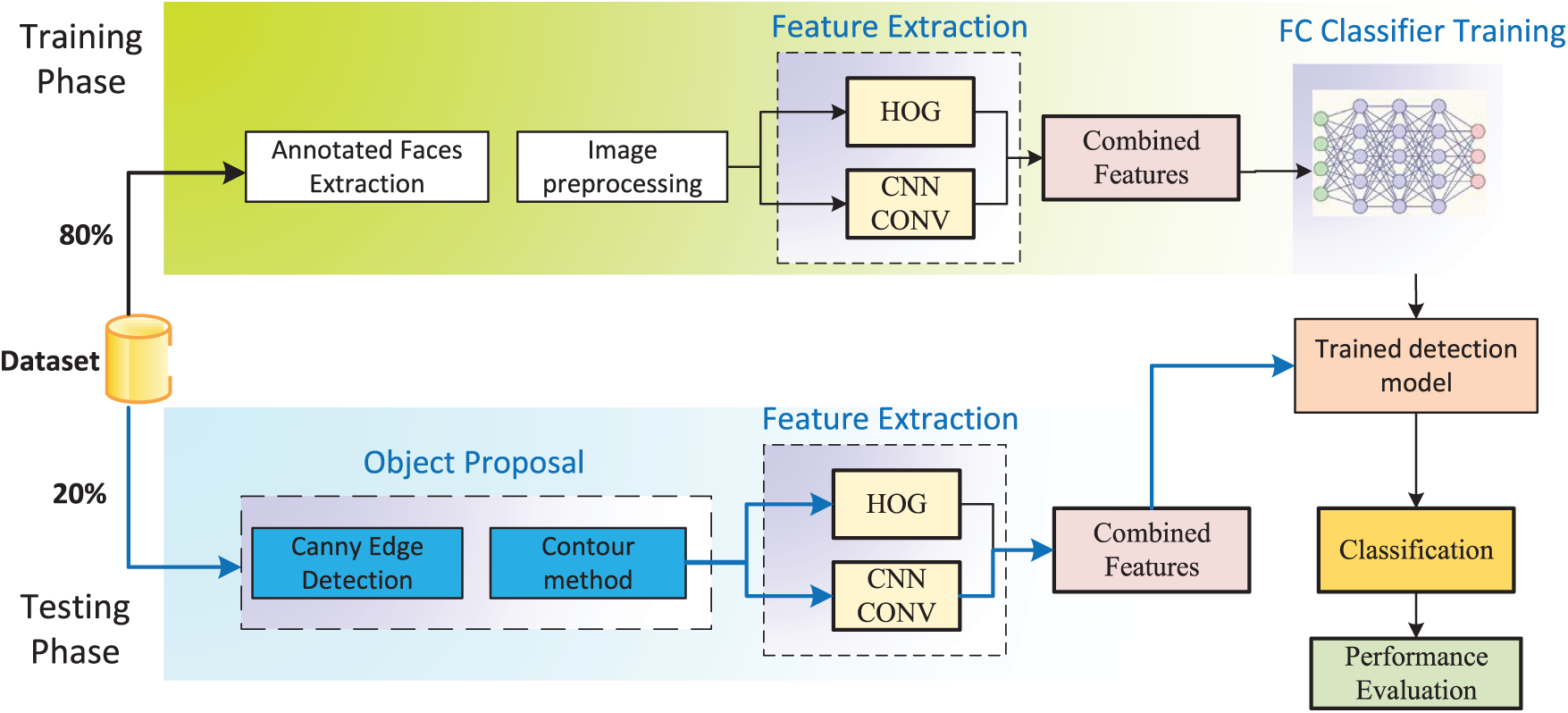

The proposed methodology for detecting occluded faces is based on a hybrid pipeline that combines deep learning models with traditional feature extraction techniques. As illustrated in Fig. 6, the pipeline is divided into two main stages: training and testing to ensure effective learning and enhanced detection of heavily occluded faces.

Figure 6: Training and testing phases of the proposed hybrid feature fusion pipeline for occluded face detection. The diagram outlines the end-to-end workflow of the model, integrating handcrafted and deep features for training and prediction stages

• Step 1: Dataset Preprocessing

The training process begins with preprocessing the input data. Images from the Niqab dataset and COCO dataset are resized to 224

• Step 2: Feature Extraction and Fusion

This step involves extracting features from each training image using both a CNN and HOG descriptor, followed by normalization and fusion. While our study investigated six advanced CNN models: DenseNet121, ResNet50, ResNet101, ResNet152, VGG16, and VGG19, the pipeline operates with only one model at a time. The process is carried out in the following substeps:

– Step 2.1: CNN Feature Extraction

Each image is fed into a selected pretrained CNN model (e.g., DenseNet121) using the appropriate preprocessing function. The output is a high-dimensional feature map from the final convolutional or pooling layer, which is then flattened into a 1D vector.

– Step 2.2: HOG Feature Extraction

The same image is converted to grayscale and processed using a HOG extractor to capture edge and texture features. This yields a handcrafted descriptor with lower dimensionality, which is also flattened into a 1D vector.

– Step 2.3: Feature Normalization

Due to scale and dimensionality differences between CNN and HOG features, each descriptor is normalized independently using Z-score normalization:

where

– Step 2.4: Feature Fusion

The normalized CNN and HOG vectors are concatenated using a simple concatenation method to form a single joint feature vector:

This unified vector combines high-level learned representations with handcrafted edge structures, enabling the classifier to leverage complementary information.

• Step 3: Classifier Training

The extracted features are then processed by the embedded classifier of the selected CNN model, which consists of fully connected (FC) layers followed by a softmax activation function. This classifier learns to distinguish between facial and non-facial regions. The inclusion of non-face images from the COCO dataset ensures that the model is trained to reject false positives effectively. The training process employs the categorical cross-entropy loss function to optimize classification performance by minimizing the error in predicting class probabilities.

• Step 1: Input Image Processing

During testing, new input images are preprocessed in the same way as the training data to ensure compatibility with the trained model.

• Step 2: Object Proposal

In the testing pipeline, the model generates region proposals to identify areas that potentially contain faces. For this purpose, we employed Canny edge detection combined with the contour method to generate object proposals. As discussed earlier in Section 3.3, Canny edge detection Canny edge detection highlights edges in the image, helping in the identification of boundaries. However, the contour method is used to group the connected edges into possible regions of interest. This approach narrows the search space by focusing only on those regions that are most likely to contain faces. Consequently, it reduces computational costs and therefore improves detection performance. Furthermore, to refine the generated proposals, we employed an Intersection over Union (IoU) with a threshold of 0.7 as the metric to determine the possible target regions. The threshold value was chosen based on experimental results and recommended values in the literature [68]. Specifically, this approach aims to exclude unnecessary or radical overlapping regions. Consequently, it helps to improve the computational efficiency of the model and the accuracy of detection by retaining only the most important proposals, thus preventing the model from paying attention to insignificant or overlapping face regions.

• Step 3: Feature Extraction and Classification

Each proposed region is processed using both the CNN and HOG-based feature extractors. As described in Step 2 of the training phase, features are independently normalized using Z-score scaling and then concatenated to form a joint representation. This combined feature vector is then passed through the CNN’s fully connected layers to classify whether the region contains a face or not. By applying the same fusion strategy used during training, the model maintains consistency in its learned feature space during inference.

4.3 Performance Evaluation Measures

This section exlains the evaluation metrics that have been used to measure the effectiveness of the suggested model. The focus was on three criteria: classification quality, calculation time, and localization quality. These evaluation metrics were selected to comprehensively evaluate the effectiveness of the model in different aspects of the detection task. Classification metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score were chosen because face detection is framed as a binary classification problem (face vs. non-face). These metrics are standard in the literature and help quantify how well the model balances false positives and false negatives [68]. In addition, computational time (training and inference) was measured to assess model practicality in real-time or near-real-time systems. Finally, qualitative localization evaluation was included to demonstrate how well the model identifies and outlines occluded faces in challenging real-world scenarios.

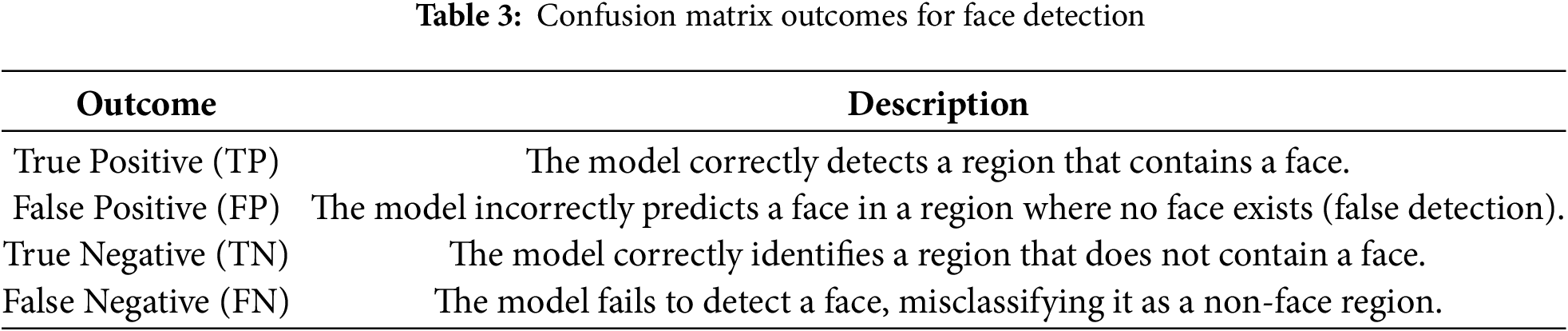

4.3.1 Classification Quality Metrics

In this study, the face detection task is considered as a binary classification problem, where 1 and 0 are used to represent positive and negative classes, respectively. When the classifier is applied, the outcomes are categorized into four groups: true positives, false positives, true negatives, and false negatives, as shown in Table 3.

Based on these results, we calculate several evaluation metrics, including precision, accuracy, recall, and F1 score [68]. These classification metrics provide information about the model’s ability to distinguish between face and non-face regions. The mathematical formula for each measure is explained as follows (Eqs. (5)–(8)):

1. a measure of the percentage of samples that are correctly classified as positive or negative.

2. Precision: measures how well the model avoids false positives by looking at the percentage of correctly identified faces (TP) from all the predicted faces (TP + FP).

3. Recall: is a metric that quantifies the model’s sensitivity in identifying faces. It is the rate of correctly identified faces (TP) among all the real faces (TP + FN).

4. F1-score: it is a measure of the overall performance that considers both precision and recall through their harmonic mean.

To determine the effectiveness of the proposed pipeline in terms of computation time, both training time and inference time are assessed. Training time is the time needed for training the model, including the feature extraction step and the classifier learning process, while inference time is the time that the model needs to process and classify images in the testing phase.

The accuracy of the localization in the proposed model was measured by the use of sample images to visually check the bounded boxes predicted by the model. These visual examples show how effective the model is in detecting and localizing occluded faces. In our evaluation, all predicted bounding boxes were compared against the contextually labeled ground truth boxes. These ground truth boxes include not only the visible facial area but also surrounding contextual regions, as discussed in Section 4.1.1. This approach aligns with the annotation strategy used in the Niqab dataset and was chosen to improve robustness in detecting heavily occluded faces [11,19]. Therefore, the reported evaluation metrics reflect detection accuracy with respect to these expanded contextual labels, rather than conventional face-only boxes.

The accuracy of the localization in the proposed model was measured using both quantitative and qualitative evaluations. We employed the IoU metric to quantitatively assess how well the predicted bounding boxes align with the ground truth annotations. In addition, sample images were also used to visually check the bounded boxes predicted by the model. These visual examples show how effective the model is in detecting and localizing occluded faces. The IoU is calculated using Eq. (9), where higher IoU values indicate better localization accuracy:

In our evaluation, all predicted bounding boxes were compared against the contextually labeled ground truth boxes. These ground truth boxes include not only the visible facial area but also surrounding contextual regions, as discussed in Section 4.1.1. This approach aligns with the annotation strategy used in the Niqab dataset and was chosen to improve robustness in detecting heavily occluded faces [11,19]. Therefore, the reported evaluation metrics reflect detection accuracy with respect to these expanded contextual labels, rather than conventional face-only boxes.

5 Experimental Results and Discussion

This section aims to describe the research design, which is implemented to validate the efficacy of the proposed model. The computing environment, parameter settings, and statistical methods that were employed in the experiments are also detailed.

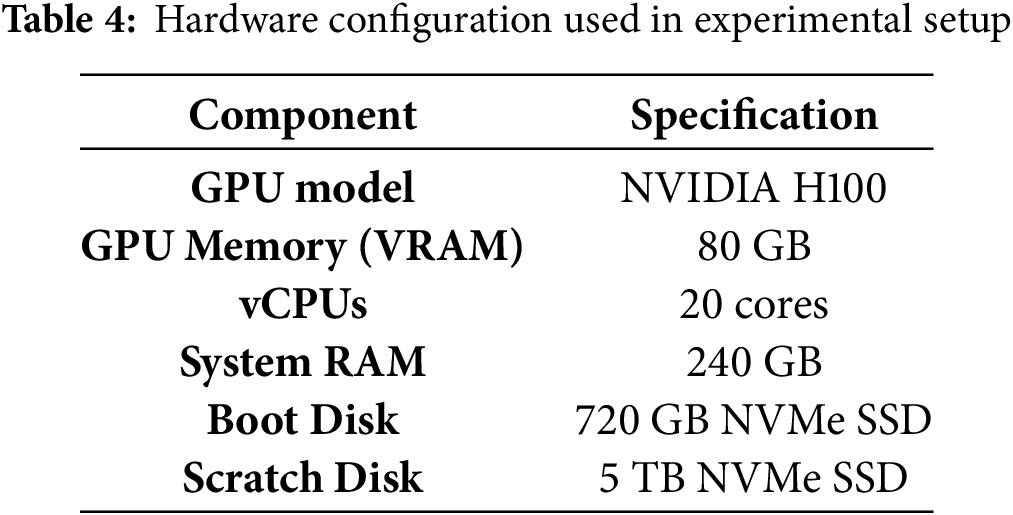

All experiments were conducted in the same computing environment to ensure reproducibility and fair performance comparison. To this end, a cloud-based GPU droplet from DigitalOcean was used. This choice provided a configurable high-performance computing infrastructure to handle the extensive computational requirements of activities such as training and testing of deep learning models combined with handcrafted feature extraction, and to allow stable measurement of inference and training time across models. The OS chosen was Linux, with the required GPU drivers installed following the recommendations outlined in the official DigitalOcean documentation [69]. The hardware configuration of this setup is summarized in Table 4. This consistency in hardware ensures the reproducibility of results and prevents variations in training time, convergence, or inference performance that could occur if different experimental setups were used.

For the programming environment, Python 3.11 with TensorFlow 2 and Keras as the primary deep learning frameworks were used for conducting the deep learning tasks. Other libraries like OpenCV and scikit-learn were also incorporated into the environment to assist in preprocessing, feature extraction, and performance evaluation functions.

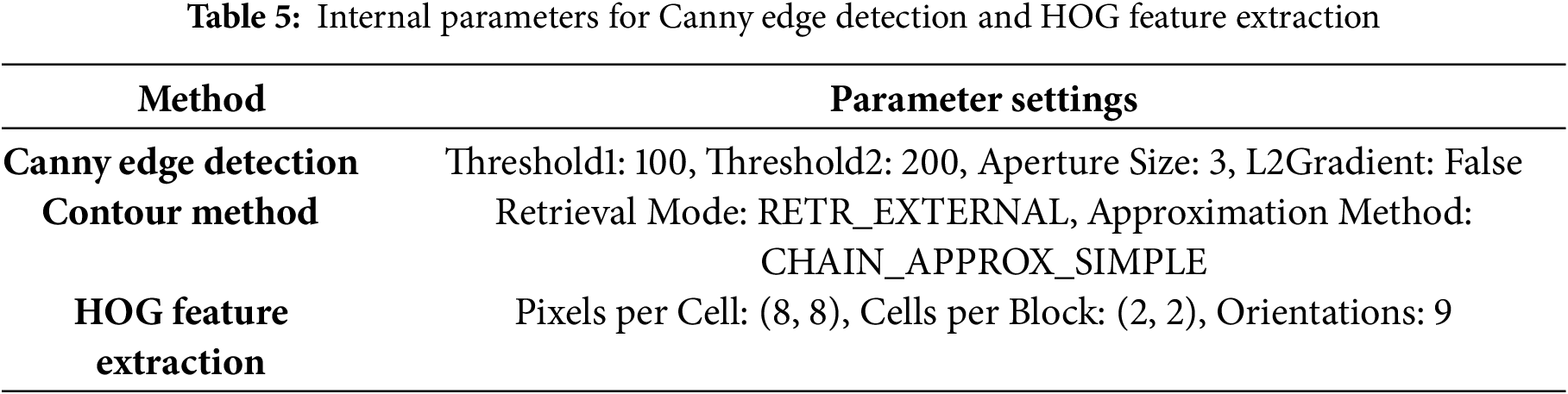

This subsection describes the parameter settings and configurations used in the experiments. All input images were resized to 224

For edge detection and object proposal, we used Canny edge detection and the contour method based on the OpenCV documentation. The HOG feature extraction method was implemented with its default settings as documented in Scikit-Image. The internal parameter settings for Canny edge detection, contour method, and HOG feature extraction are summarized in Table 5.

To ensure reliability, each experiment was repeated with five independent runs. The average and standard deviation of the performance metrics were reported in the tables. Please note that AV G denotes the average, STD denotes the standard deviation, and the most favorable findings are highlighted in boldface.

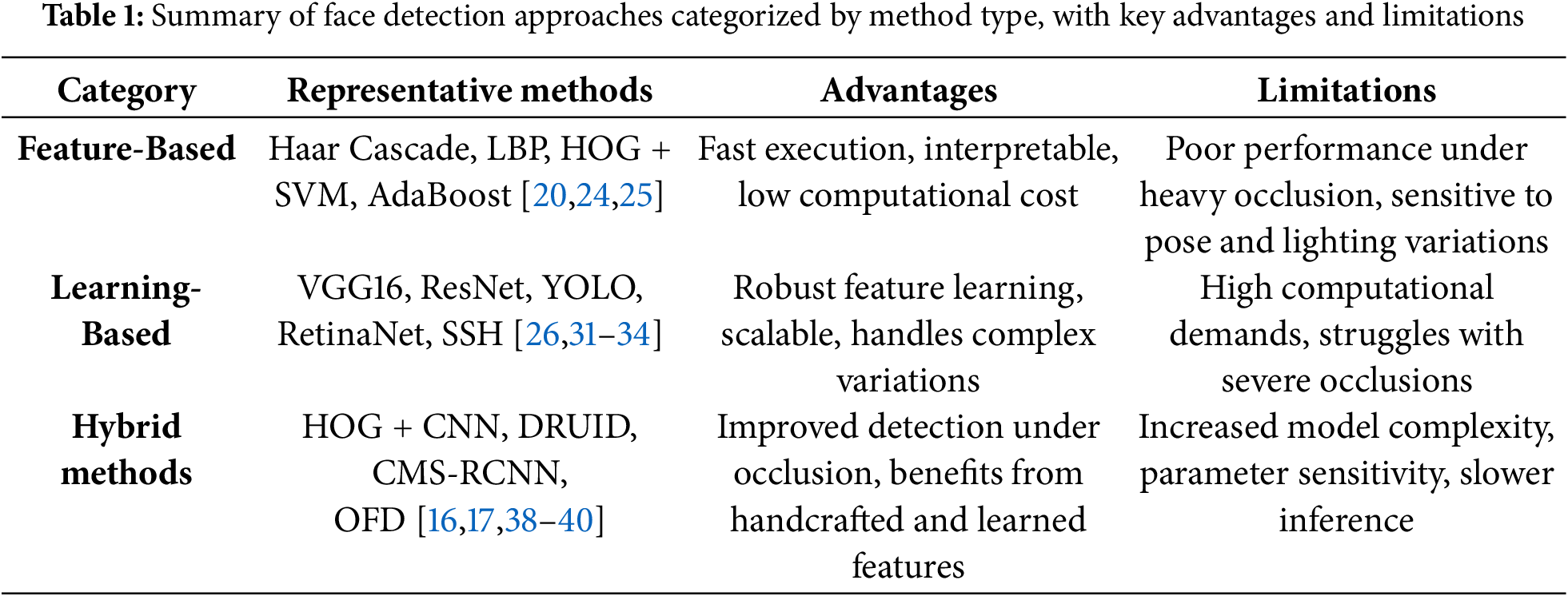

Given the stochastic behavior of the algorithms examined in this study, non-parametric statistical methods are widely recommended in computational intelligence research [70]. To assess performance differences between the tested algorithms, we employed the Mann-Whitney U test, a non-parametric alternative to the t-test, using a 5% significance level (

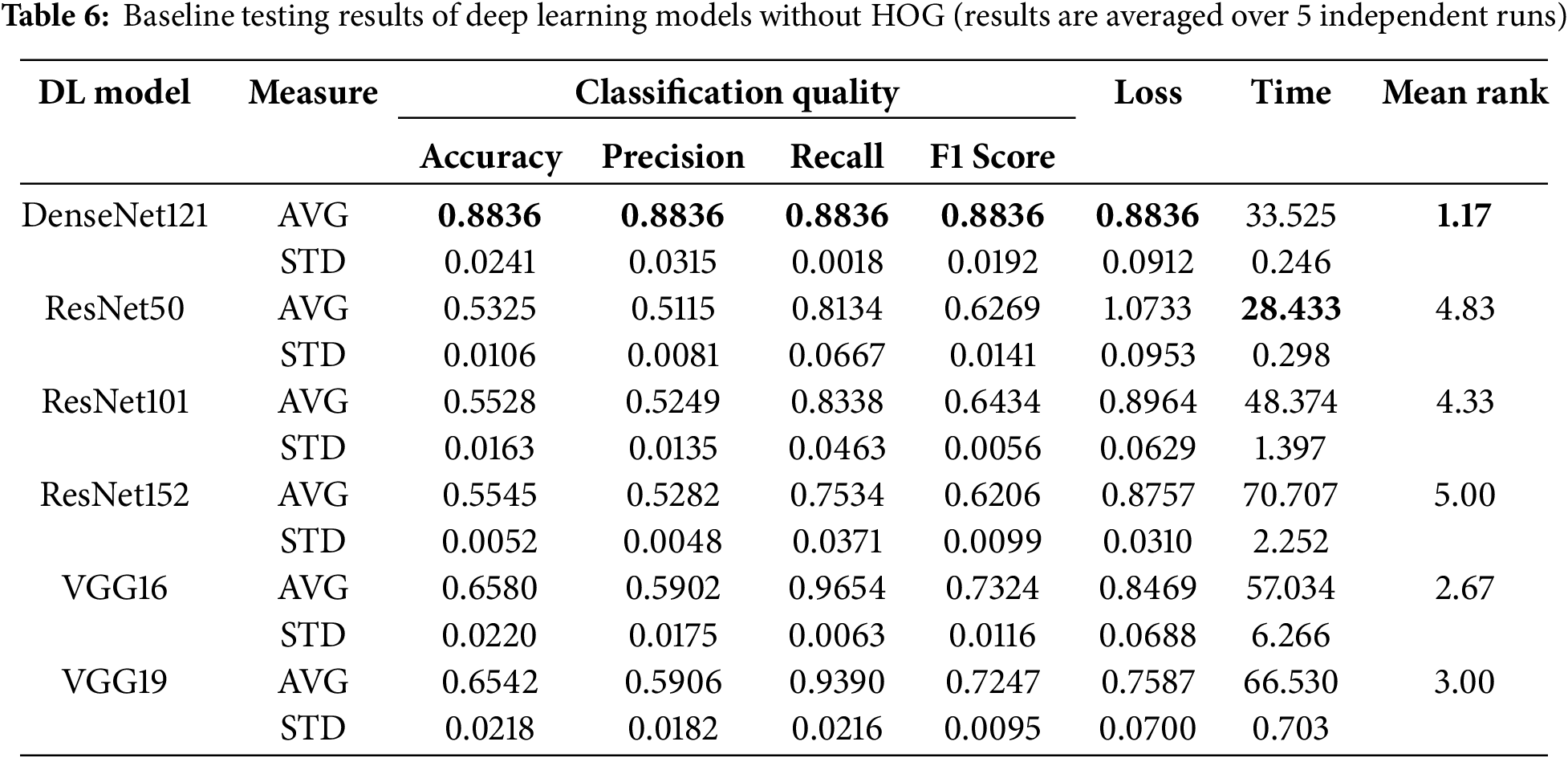

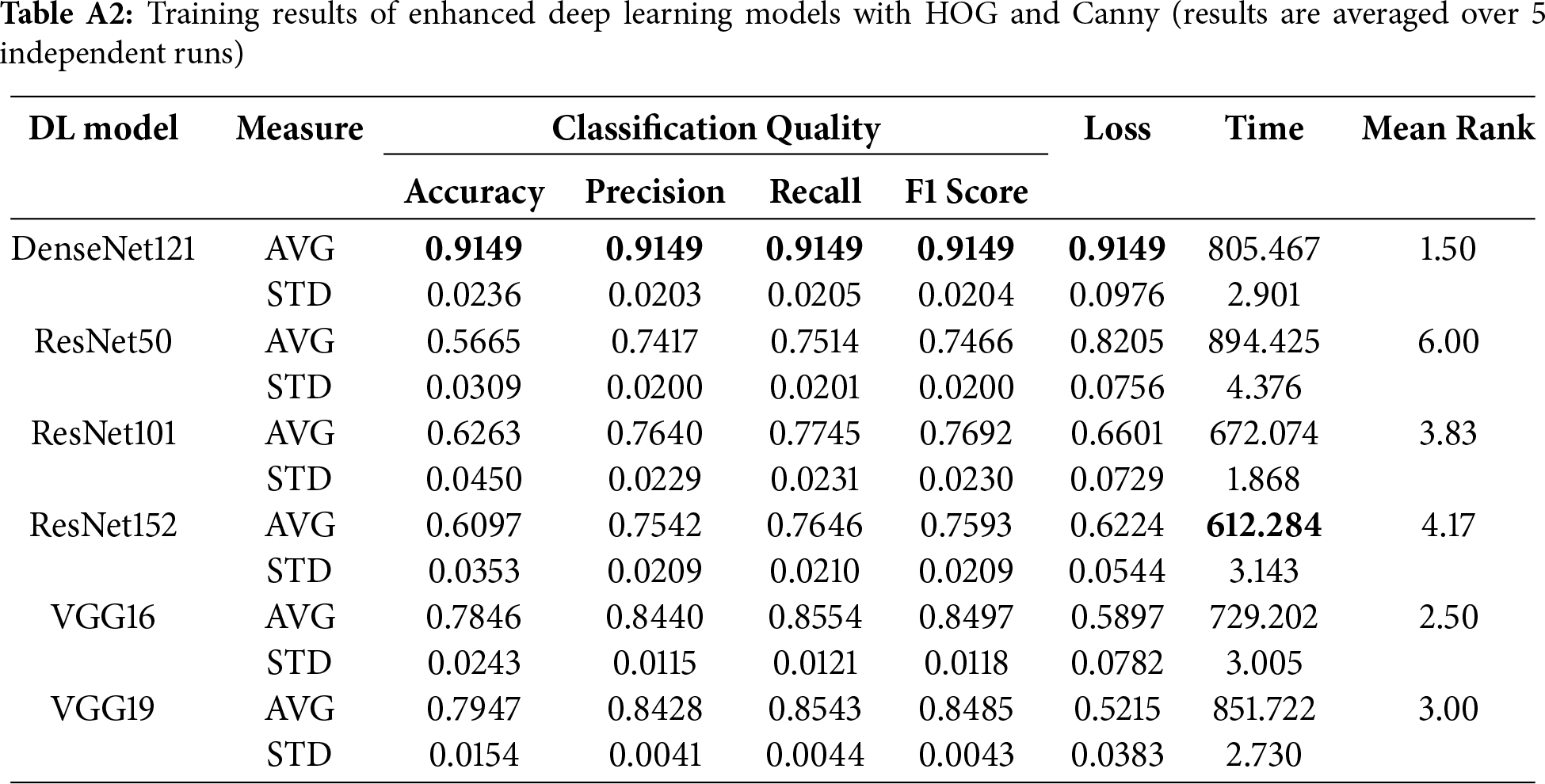

This section presents the results of experiments conducted to evaluate the performance of six deep learning models, including DenseNet121, ResNet50, ResNet101, ResNet152, VGG16, in occluded face detection. The experiments were carried out in two phases; in the first phase, the baseline models were investigated without using HOG and canny-based object proposals. Meanwhile, in the second phase, the same models were evaluated after applying HOG and object proposals to enhance feature extraction. The evaluation focused on key performance metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall, F1 score, loss, and time (training and inference). In addition, a mean rank analysis was used to compare overall performance across the models and highlight the best-performing approaches.

5.2.1 Results of Phase 1: Baseline Performance

Table 6 presents the baseline performance of six deep learning models evaluated without HOG. In terms of classification quality, DenseNet121 scored the highest accuracy (88.36%) and F1-score (89.28%). It also achieved excellent recall (99.76%) and precision (80.85%), making it the most reliable model for the detection of occluded faces. VGG16 and VGG19 followed with accuracy values of 65.80% and 65.42%, approximately 22%–23% lower than DenseNet121. ResNet models showed lower accuracy, ranging between 53.25% and 55.45%, and lower precision (51%–3 53%), indicating difficulties in identifying positive samples. For further reference, the training results including the comparison of deep learning models during the training phase are presented in Table A1 in Appendix A.1.

In terms of loss, DenseNet121 had the lowest value (0.3274), which indicates better optimization and stability. VGG16 and VGG19 displayed moderate losses of 0.8469 and 0.7587, while ResNet50 recorded the highest loss (1.0733), nearly three times higher than DenseNet121, reflecting higher errors. In terms of time, ResNet50 demonstrated the fastest inference time (28.43 s), making it suitable for time-sensitive applications. Although DenseNet121 required 33.52 s, it offered a good balance between speed and accuracy. The bar chart comparisons of classification quality, loss, and time are illustrated in Figs. 7 and 8, respectively.

Figure 7: Bar chart comparing classification quality metrics for baseline deep learning models based on results in Table 6. This visualization compares performance across models in terms of accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, providing insight into their relative effectiveness before enhancement

Figure 8: Comparison of (a) loss and (b) inference time for baseline deep learning models. The figure highlights differences in model convergence behavior and computational efficiency

In summary, DenseNet121 demonstrated the best overall performance by achieving high accuracy, low loss, and reasonable processing time. VGG models performed well but took more time. Consequently, DenseNet121 ranked first (1.17), followed by VGG16 (2.67), VGG19 (3.00), and ResNet models (4.33–5.00), respectively.

To judge whether the differences in Table 6 are statistically significant, Table A3 presents the p-values from the Mann-Whitney U test. It shows the pairwise comparison between the best-performing model (DenseNet121) and other counterparts in all evaluation measures. The symbols (+), (-), and (=) indicate whether the base model is superior, inferior, or statistically equivalent to the compared model, respectively. Notably, DenseNet121 demonstrates superior performance in all cases in terms of classification measures and loss results. In terms of inference time, DenseNet121 shows a statistically higher time compared to ResNet50.

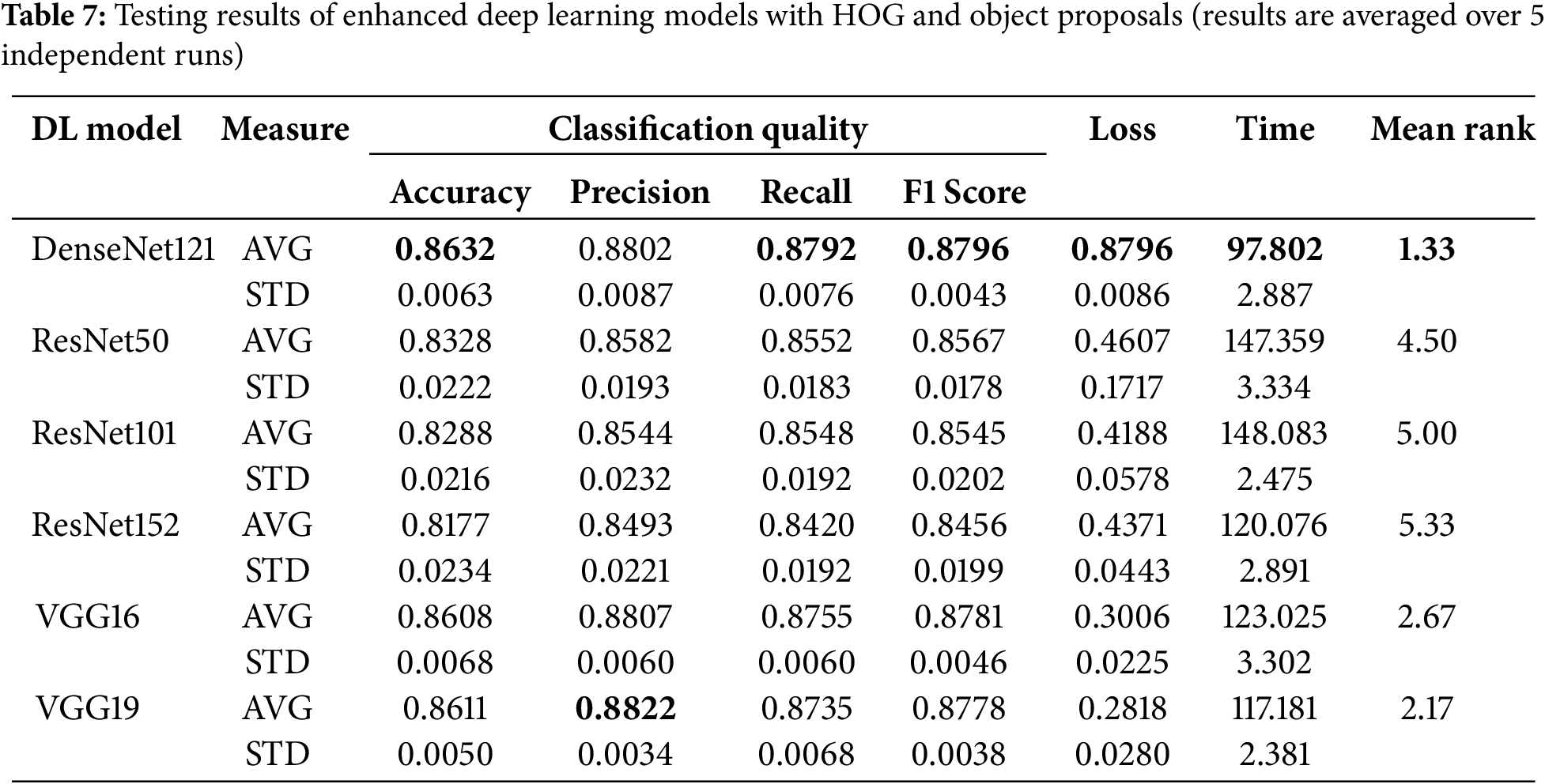

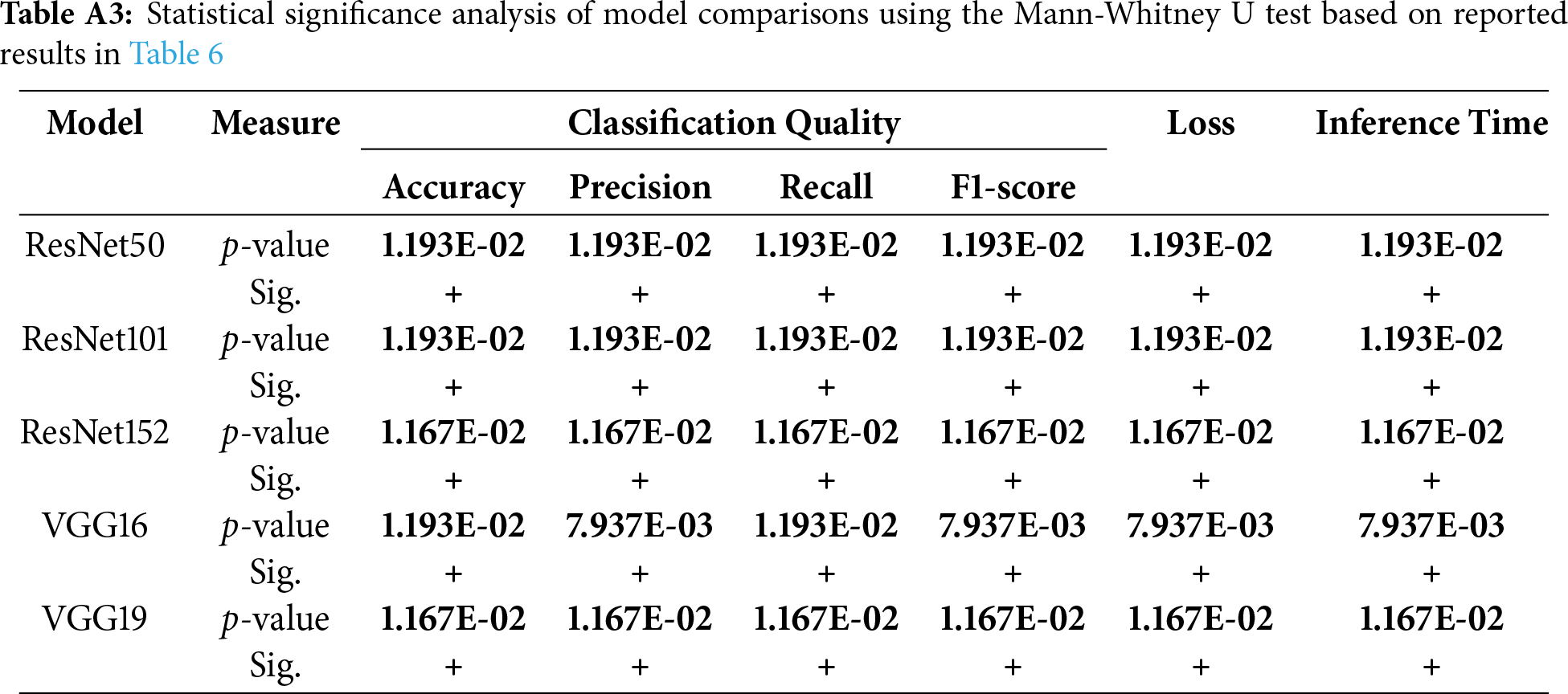

5.2.2 Results of Phase 2: Enhanced Models with HOG and Object Proposals

In the second phase, we aim to investigate how the suggested enhancement would affect the effectiveness of the basic deep learning models. Experimental results in Table 7 demostrate the performance of the enhanced models after applying HOG and object proposals. In terms of classification quality, DenseNet121 remains the top performer, achieving an accuracy of 86.32% and an F1-score of 87.96%. VGG19 follows closely with an accuracy of 86.11% and an F1-score of 87.78%.

Compared to their baseline versions (i.e., without HOG and object proposals), all enhanced models-except DenseNet121-show notable improvements in accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 scores. Although DenseNet121’s accuracy dropped slightly from 88.36% to 86.32%, its precision increased from 80.85% to 88.02%, indicating fewer false positives in the enhanced version. While the hybrid version of DenseNet121 achieved a substantial precision gain (+7.17%), it also experienced a slight decline in accuracy and F1-score. This reflects a trade-off where the model becomes more conservative, favoring fewer false positives at the potential cost of recall. Therefore, the improvements observed are metric-dependent rather than uniform, and their relevance may vary depending on the deployment context. For example, in applications such as surveillance systems or access control, minimizing false positives (i.e., incorrectly detecting a non-face region as a face) is often prioritized over recall. In contrast, applications that require exhaustive face detection, such as crowd analysis or image indexing, may favor higher recall even at the expense of occasional false positives. ResNet models also show significant improvements, with accuracy ranging from 81.77% to 83.28% and F1 scores between 84.56% and 85.67%, addressing some of the weaknesses observed in the baseline results. Specifically, VGG19 show an increase in precision of 31.6%, improving from 65.42% to 86.11%. Similarly, ResNet50 achieved a 56.4% improvement, with its accuracy increasing from 53.25% to 83.28%. The noticeable improvement, particularly in precision, can be attributed to the inclusion of edge-based object proposals and handcrafted features like HOG. These additions helped reduce false positives by directing the model to focus on more meaningful regions of the image, which is particularly helpful when faces are partially covered or the background is complex. While the CNN backbones stayed the same, the hybrid method changed the input feature space by adding low-level edge information, which made the model better at distinguishing between face and non-face regions.

It is important to note that DenseNet121 consistently outperforms deeper models like ResNet152 across all evaluation metrics. While it has 121 layers, its strong performance is not due to depth alone but to its dense connectivity, where each layer receives inputs from all previous layers. This design improves feature reuse, gradient flow, and reduces redundancy, leading to more effective learning. In our experiments, DenseNet121 achieved the highest training and testing accuracy and F1-score, and the lowest loss values (0.0836 training, 0.2805 testing). These observations suggest a better generalization. Despite being deep, it is also parameter-efficient, which helps avoid overfitting. In contrast, ResNet152 showed higher training loss and testing loss, and lower classification accuracy, as detailed in Tables 7 and A2. This suggests that, due to its complexity, a need for longer training or more data. These observations highlight that depth alone does not ensure better performance. In tasks involving moderately sized, domain-specific, or occluded datasets, such as ours, architectural efficiency is often more important than simply increasing model depth.

In terms of inference time in Table 7, DenseNet121 achieves a faster inference time (97.802 s), making it more efficient compared to their counterparts. ResNet models, however, remain the slowest, with times of 147.359 and 148.083 s, similar to their baseline results. While the hybrid models demonstrated substantial improvements in the detection accuracy scores, this came with a noticeable increase in inference time across all architectures. For instance, the inference time for ResNet50 increased from 28.43 to 147.35 s, while DenseNet121’s inference time nearly tripled from 33.52 to 97.80 s. This is primarily due to the additional overhead introduced by object proposal generation and handcrafted feature extraction. Accordingly, such increases may limit the applicability of the proposed approach in real-time or resource-constrained environments, such as edge devices or mobile platforms. Therefore, the model’s practicality is better suited for offline analysis, server-side processing, or applications where detection accuracy is prioritized over speed, such as security footage review or forensic analysis.

As per loss results, all models achieved lower loss values compared to the baseline, indicating better optimization and stability after applying HOG and object proposals. For instance, DenseNet121 performed the best where its loss decreased from 0.3274 to 0.2805, a 14.3% reduction. To further investigate the convergence behavior, Fig. 9 depicts the training loss curves of the enhanced models over 25 epochs. These curves illustrate the evolution of loss values over the epochs. It is clear that DenseNet121 with HOG achieves the fastest convergence process, which indicates better learning efficiency and convergence behavior.

Figure 9: Loss curves for enhanced models over 25 training epochs. This plot illustrates the training stability and convergence of the hybrid models, confirming their learning effectiveness on the occluded face dataset

The detailed comparison of the enhanced deep learning models during the training phase can be found in Table A2 in Appendix A.2.

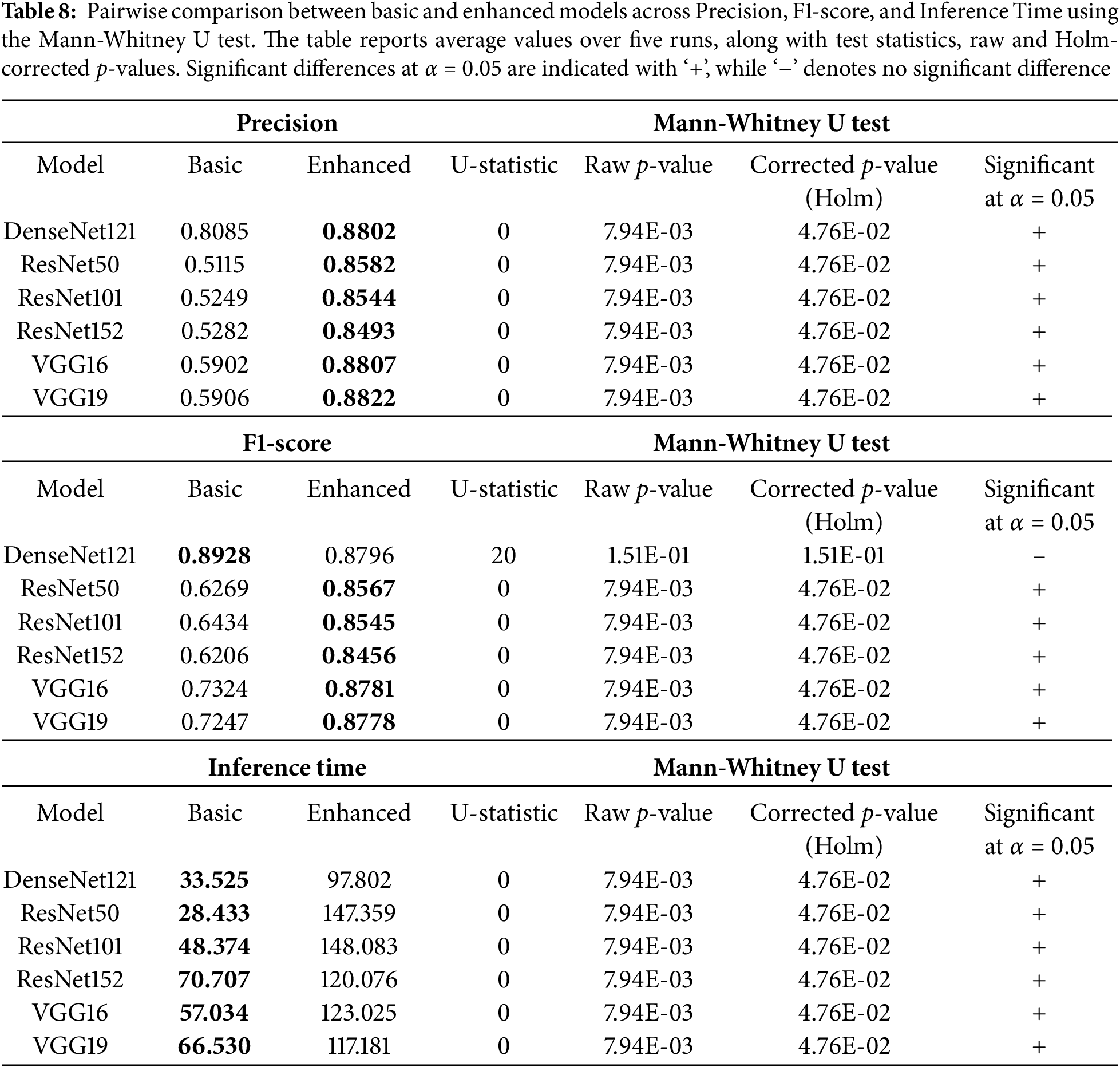

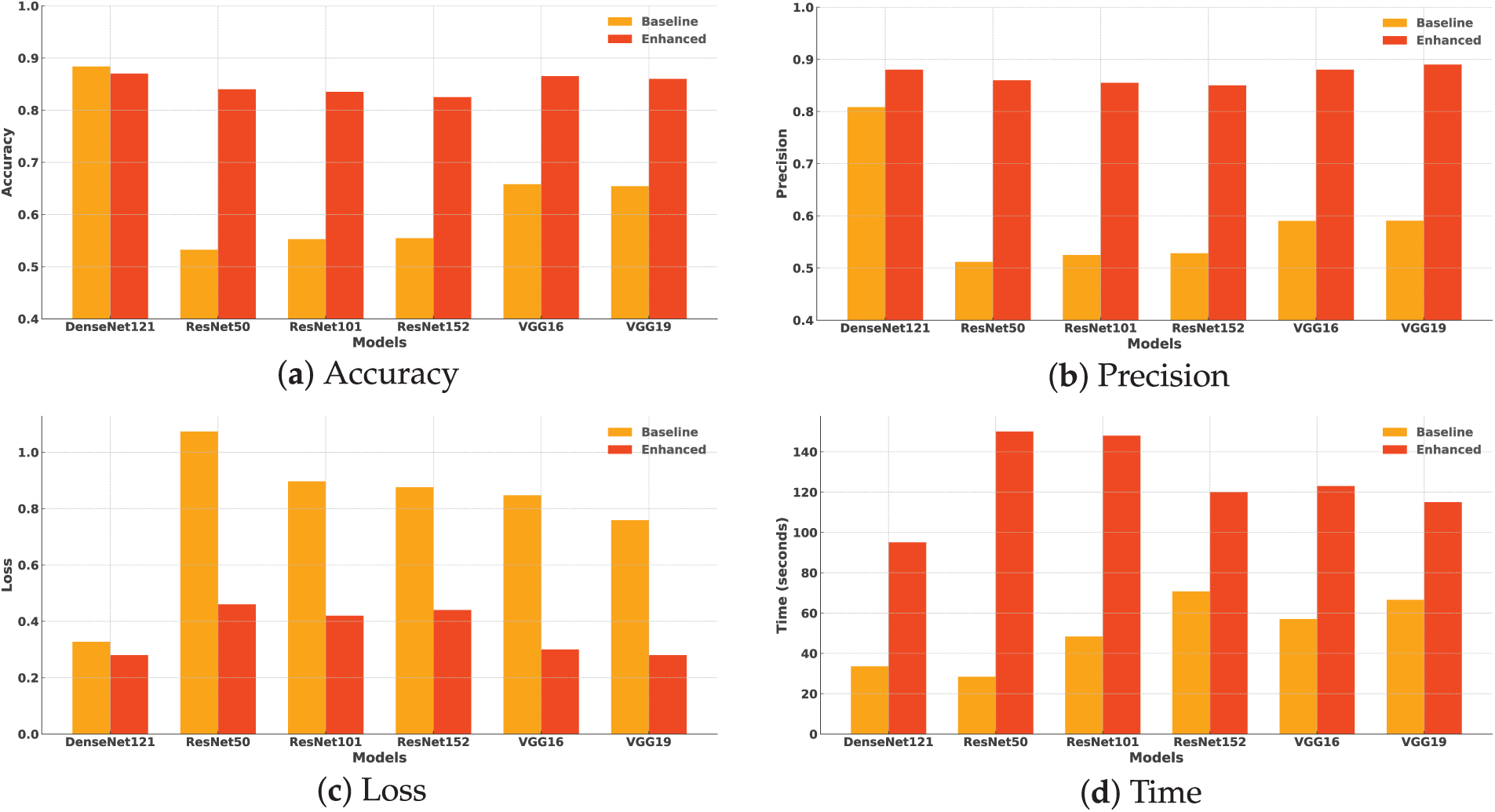

To highlight the improvement and difference in the classification accuracy and other criteria, Table 8 presents a pairwise comparison between the basic and enhanced variants of each model in terms of precision, F1_score, and inference time. These comparisons are also depicted through the charts in Fig. 10.

Figure 10: Comparison of basic and enhanced models in terms of (a) accuracy, (b) precision, (c) loss, and (d) inference time. This multi-panel figure demonstrates the improvement achieved through hybridization, based on experimental results from Tables 6 and 7

To evaluate the statistical significance of performance differences between basic and enhanced models, we conducted pairwise comparisons using the Mann-Whitney U test for each model across three evaluation metrics: precision, F1-score, and inference time. As shown in Table 8, the table reports the U test statistics, raw p-values, and the corrected p-values using the Holm-Bonferroni correction. This correction was applied to control for Type I errors resulting from multiple comparisons across several models and metrics. A significance level of

The results show that enhanced models significantly outperform their basic counterparts in most cases for precision and F1-score, with the exception of DenseNet121 in F1-score, where the difference was not statistically significant. Additionally, inference time was consistently and significantly higher for enhanced models, reflecting the added computational cost of their improved effectiveness. To further support the analysis, Fig. 11 presents boxplots of the three evaluation metrics. It illustrates the distribution across five independent runs. The boxplots visually confirm the statistical results, showing higher precision and F1-scores for enhanced models, and noticeably higher inference time compared to basic versions.

Figure 11: Boxplot comparison of model performance across five independent runs for (a) Precision, (b) F1-score, and (c) Inference Time. Each subplot compares the basic and enhanced versions of the six evaluated models. These visualizations support the statistical comparison presented in Table 8

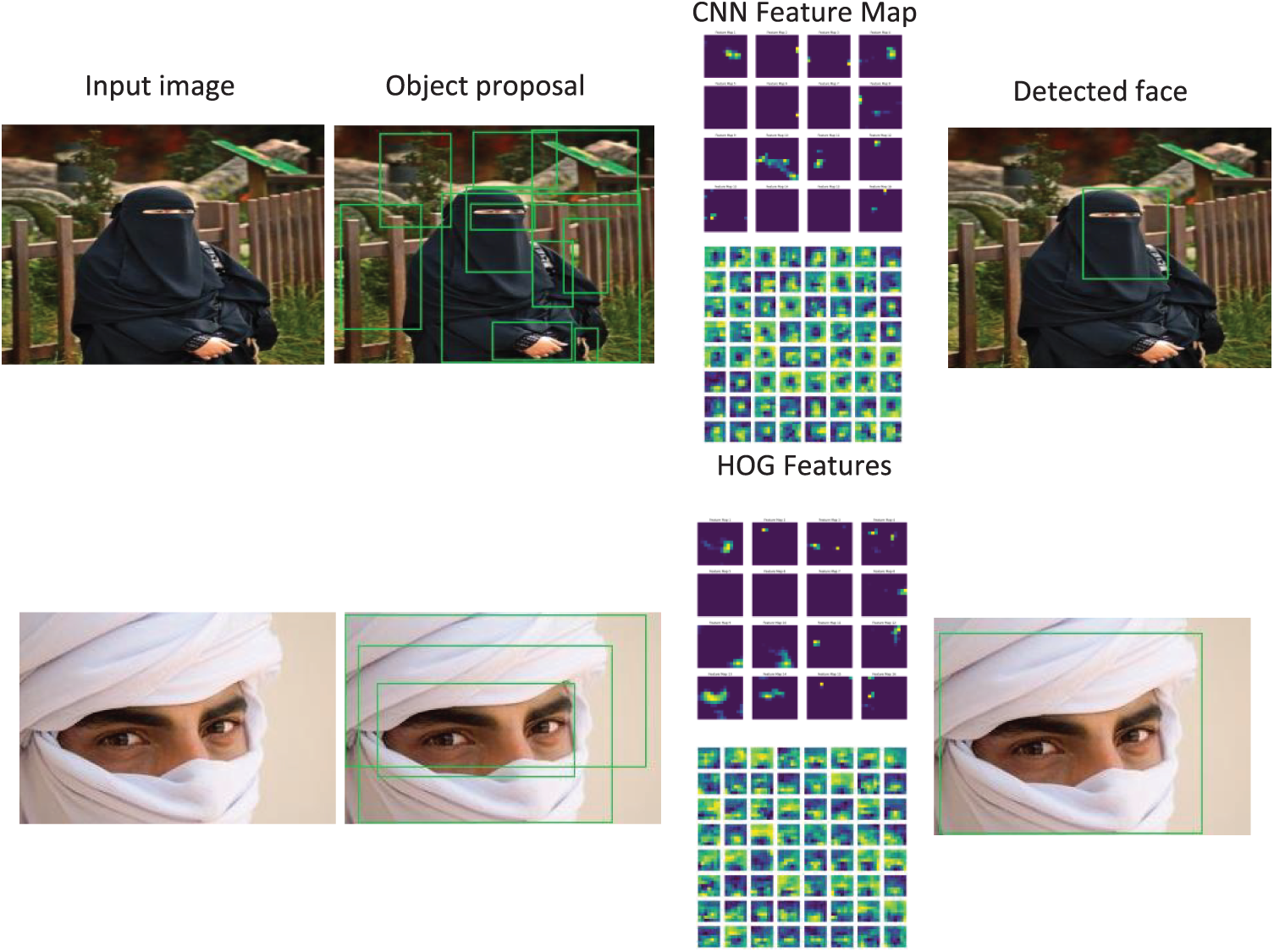

5.2.3 Visualization of Processing Stages

In addition to the quantitative evaluation presented earlier, this subsection provides a qualitative analysis to demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed enhanced model in detecting occluded faces. The visualizations illustrate the testing pipeline, starting with the input image, which represents the raw data used for detection. Next, the Canny-based object proposal highlights potential regions of interest by detecting edges using the Canny algorithm. Following this, the CNN feature maps capture spatial and structural patterns through intermediate layers of the convolutional network. The HOG-based features enhance shape and edge information for more accurate feature extraction. Finally, the output localization depicts the detected faces with bounding boxes to show the final detection result. Figs. 12 and 13 visualize these steps of the processing pipeline using a sample of test images. They illustrate how the features are extracted and processed to effectively detect heavily covered faces.

Figure 12: Examples of the different processing stages in the proposed hybrid model. The figure shows the input image, Canny-based object proposals, CNN feature maps, HOG features, and the final detected face

Figure 13: Illustration of the effectiveness of the hybrid model in detecting multiple occluded faces. The three panels show the input image (left), generated object proposals using edge and contour cues (middle), and final face detections by the hybrid model (right). This example demonstrates the model’s robustness in handling group scenarios with varied levels of facial occlusion

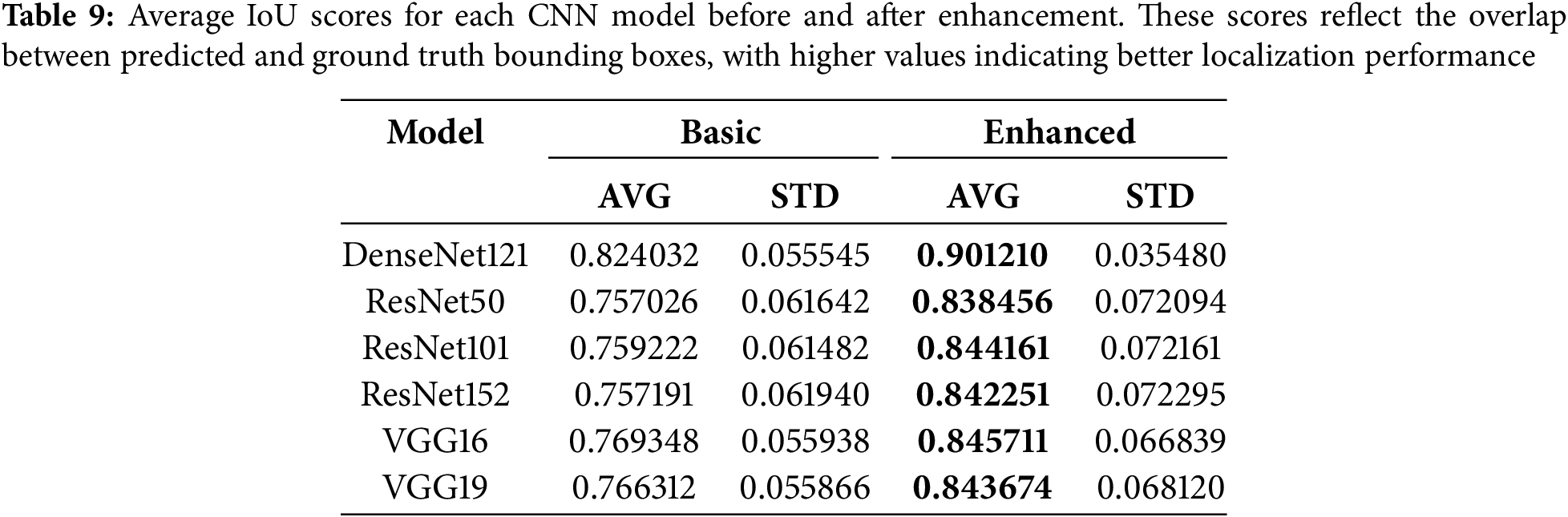

In addition to classification performance, localization accuracy was evaluated using the Intersection-over-Union (IoU) metric between predicted and ground truth bounding boxes. Table 9 reports the average IoU for each model variant across the test images. Notably, the enhanced versions consistently outperformed their baseline counterparts. DenseNet121 attaining the highest average (0.9012), compared to its baseline score of 0.8240 after integrating HOG and object proposals. These results indicate that the proposed hybrid approach improves localization precision.

In addition to the quantitative analysis and to provide a clearer and verifiable demonstration of localization performance, Fig. 14 presents visual samples from the test set after applying the enhanced DenseNet121 model, with predicted bounding boxes overlaid alongside the ground truth. The corresponding IoU scores are shown to quantify how well each prediction aligns with its labeled region.

Figure 14: Sample visualizations showing predicted bounding boxes (green) vs. ground truth (red) on occluded faces, with corresponding Intersection over Union (IoU) scores

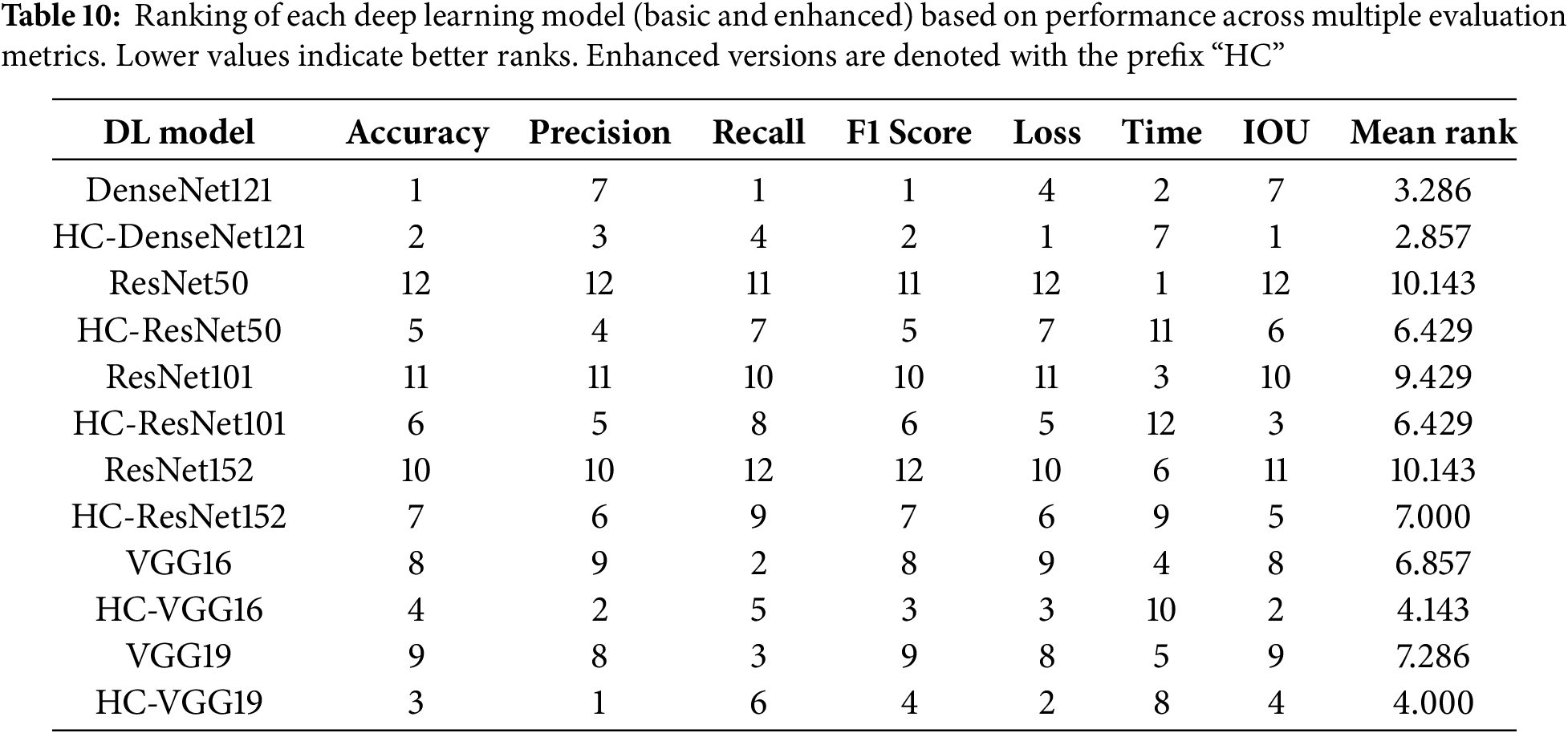

To provide a comprehensive comparison, we ranked all tested models across seven evaluation metrics: accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, loss, inference time, and IOU. Table 10 presents these ranks along with the mean rank for each model. Enhanced versions are labeled with the prefix “HC”. Overall, HC-DenseNet121 achieved the best mean rank, followed by DenseNet121 and HC-VGG19, indicating strong and consistent performance. In contrast, deeper models like ResNet152 obtained higher mean ranks, reflecting lower overall effectiveness. These results suggest that the hybrid enhancements positively impact model performance across most evaluation criteria.

6 Advantages and Limitations of the Proposed Hybrid Model

This section discusses the strengths and limitations of the proposed hybrid model, which combines HOG-based hand-crafted features with CNN modles to improve the detection of occluded faces. It highlights the benefits of the model and points out areas where further improvements may be needed.

The proposed hybrid model has several benefits: First, it enhances feature extraction. The model learns important details such as edges and patterns, by combining HOG features with CNN feature maps. This improvement is particularly useful for detecting faces, even if they are partially covered. Second, it improves precision. Experimental results demonstrate that the hybrid approach reduces false positives and enhance the precision of face detection. Third, it ensures robust performance. Overall, the integration of HOG and Canny edge-based object proposals led to consistent improvements across most CNN-based models in key metrics such as precision and localization accuracy. However, the degree and nature of improvement varied by architecture and evaluation measure, suggesting that the hybrid enhanced DenseNet is more beneficial in scenarios where minimizing false positives is prioritized.

Despite its merits, the proposed model also exhibits some limitations:

1. Computational Overhead: The combination of HOG and CNN increases the processing time, especially during inference, which may be a challenge for real-time applications.

2. Need for Parameter Tuning: The model requires careful adjustment of hyperparameters to perform well. This includes:

• Canny parameters, such as threshold values, which control edge detection sensitivity.

• HOG parameters, like the cell size and block size, which affect feature extraction quality.

• CNN parameters, such as the learning rate, batch size, and number of epochs, which influence training stability and performance.

This tuning process can also take extra time and effort especially for optimizing performance across multiple datasets.

3. Generalization Concerns: The model was tested on a single dataset with highly occluded faces, which may limit its generalization to other datasets that may have different kinds of occlusion or have different image quality, pose, and lighting. As the No Free Lunch Theorem states, there is no single model that will be the best in all scenarios, meaning that the adaptability of the proposed approach should be evaluated against additional datasets.

This study addressed the challenge of detecting heavily occluded faces by proposing a hybrid approach that integrates handcrafted features with deep learning models. The methodology combined HOG and Canny edge detection with advanced CNN models to enhance feature extraction and improve robustness under occlusions. Experimental evaluations demonstrated that the proposed hybrid approach yielded measurable improvements in classification metrics compared to baseline CNN models. Notably, DenseNet121 emerged as the top-performing model, achieving an F1-score of 87.96% and precision of 88.02%, with a 9% improvement in precision relative to the baseline. Other models, including VGG19 and ResNet50, also showed enhancements in accuracy and stability, with ResNet50 achieving a 56.4% accuracy improvement after integrating HOG and object proposals.

Despite a slight increase in computational cost, the results support the effectiveness of combining traditional feature extraction techniques with deep learning architectures in handling occlusions caused by traditional coverings such as niqabs worn by Muslim women and other veils commonly used for cultural or religious reasons.

Nonetheless, the method’s sensitivity to parameters and its increased inference time highlight areas for optimization and further research. While the proposed model is suitable for offline or server-based analysis, it is not yet practical for deployment on resource-constrained devices such as mobile or edge platforms. Future research could focus on reducing computational overhead by optimizing the feature extraction and object proposal steps, exploring lightweight CNN architectures for faster inference in real-time systems, applying model pruning, or utilizing lightweight classifiers such as extreme learning machines to improve deployment feasibility without compromising performance. Additionally, investigations into other handcrafted features, such as Local Binary Analysis (LBA), and alternative edge detection methods, including Sobel and Prewitt operators, could enhance feature representation and improve detection performance. Further studies could also improve generalization by testing the model on diverse datasets, including images with crowded scenes and varying occlusion patterns. Moreover, future work could explore advanced fusion strategies, such as attention-based fusion, weighted combinations, or learned feature selection, to better integrate handcrafted and deep features and further boost model accuracy. Incorporating transformer-based architectures for enhanced contextual learning, exploring multimodal fusion techniques, and extending the model for application-specific tasks, such as masked face recognition, could further validate its scalability and practical utility.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to acknowledge A’Sharqiyah University, Sultanate of Oman, and Palestine Technical University—Kadoorie for supporting this research.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by A’Sharqiyah University, Sultanate of Oman, under Research Project Grant Number (BFP/RGP/ICT/22/490).

Author Contributions: Conceptualization: Thaer Thaher, Majdi Mafarja, Muhammed Saffarini, Abdulaziz Alashbi, Abdul Hakim Mohamed, and Ayman A. El-Saleh. Methodology: Thaer Thaher, Majdi Mafarja, and Muhammed Saffarini. Data collection and curation: Abdulaziz Alashbi and Abdul Hakim Mohamed. Software: Thaer Thaher and Muhammed Saffarini. Investigation: Thaer Thaher and Muhammed Saffarini. Validation: Thaer Thaher, Muhammed Saffarini, Majdi Mafarja, Ayman A. El-Saleh, and Abdul Hakim Mohamed. Writing—original draft preparation: Thaer Thaher. Writing—review and editing: Thaer Thaher, Muhammed Saffarini, Majdi Mafarja, Abdul Hakim Mohamed, and Ayman A. El-Saleh. Supervision: Abdul Hakim Mohamed and Ayman A. El-Saleh. Project administration, Abdul Hakim Mohamed and Ayman A. El-Saleh. Funding acquisition: Abdul Hakim Mohamed and Ayman A. El-Saleh. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data presented in this study was provided by one of the manuscript authors, Abdulaziz Alashbi. It is available upon reasonable request from A. Alashbi (email: abdulaziez.hm@gmail.com).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Appendix A

Appendix A.1 Training Results of Basic and Enhanced Models

Appendix A.2 Mann-Whitney Test Results for Deep Learning Model Comparisons

References

1. Zhang Z, Wang L, Lee C. Recent advances in artificial intelligence sensors. Adv Sensor Res. 2023;2(8):2200072. [Google Scholar]

2. Iqbal U, Davies T, Perez P. A review of recent hardware and software advances in GPU-accelerated edge-computing single-board computers (SBCs) for computer vision. Sensors. 2024;24(15):4830. doi:10.3390/s24154830. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Zhang C, Zhang Z. A survey of recent advances in face detection; 2010. MSR-TR-2010-66. [cited 2025 Jul 9]. Available from: https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/research/publication/a-survey-of-recent-advances-in-face-detection/. [Google Scholar]

4. D’mello SK, Kory J. A review and meta-analysis of multimodal affect detection systems. ACM Comput Surv. 2015;47(3):43. doi:10.1145/2682899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Yang MH, Kriegman DJ, Ahuja N. Detecting faces in images: a survey. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2002;24(1):34–58. doi:10.1109/34.982883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Feng Y, Yu S, Peng H, Li YR, Zhang J. Detect faces efficiently: a survey and evaluations. IEEE Trans Biom Behav Identity Sci. 2022;4(1):1–18. doi:10.1109/TBIOM.2021.3120412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Nada H, Sindagi V, Zhang H, Patel V. Pushing the limits of unconstrained face detection: a challenge dataset and baseline results. In: 2018 IEEE 9th International Conference on Biometrics Theory, Applications and Systems (BTAS); 2018 Oct 22–25; Redondo Beach, CA, USA. p. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

8. Yuan Z. Face detection and recognition based on visual attention mechanism guidance model in unrestricted posture. Sci Program. 2020;2020(1):8861987. doi:10.1155/2020/8861987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Zhu X, Ramanan D. Face detection, pose estimation, and landmark localization in the wild. In: 2012 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2012 Jun 16–21; Providence, RI, USA. p. 2879–86. [Google Scholar]

10. Yang S, Luo P, Loy CC, Tang X. WIDER FACE: a face detection benchmark. In: 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2016 Jun 27–30; Las Vegas, NV, USA. p. 5525–33. [Google Scholar]