Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Wireless Sensor Network Modeling and Analysis for Attack Detection

1 Laboratory of Internet of Things, International Science Complex “Astana”, Astana, 010000, Kazakhstan

2 Department of Information Systems, L.N. Gumilyov Eurasian National University, Astana, 010000, Kazakhstan

3 Laboratory of Computer Security Problems, St. Petersburg Federal Research Center of the Russian Academy of Sciences, St. Petersburg, 199178, Russia

4 Department of Artificial Intelligence and Big Data, Al-Farabi Kazakh National University, Almaty, 050040, Kazakhstan

* Corresponding Author: Tamara Zhukabayeva. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Emerging Technologies in Information Security )

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 144(2), 2591-2625. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.067142

Received 25 April 2025; Accepted 22 July 2025; Issue published 31 August 2025

Abstract

Wireless Sensor Networks (WSN) have gained significant attention over recent years due to their extensive applications in various domains such as environmental monitoring, healthcare systems, industrial automation, and smart cities. However, such networks are inherently vulnerable to different types of attacks because they operate in open environments with limited resources and constrained communication capabilities. The paper addresses challenges related to modeling and analysis of wireless sensor networks and their susceptibility to attacks. Its objective is to create versatile modeling tools capable of detecting attacks against network devices and identifying anomalies caused either by legitimate user errors or malicious activities. A proposed integrated approach for data collection, preprocessing, and analysis in WSN outlines a series of steps applicable throughout both the design phase and operation stage. This ensures effective detection of attacks and anomalies within WSNs. An introduced attack model specifies potential types of unauthorized network layer attacks targeting network nodes, transmitted data, and services offered by the WSN. Furthermore, a graph-based analytical framework was designed to detect attacks by evaluating real-time events from network nodes and determining if an attack is underway. Additionally, a simulation model based on sequences of imperative rules defining behaviors of both regular and compromised nodes is presented. Overall, this technique was experimentally verified using a segment of a WSN embedded in a smart city infrastructure, simulating a wormhole attack. Results demonstrate the viability and practical significance of the technique for enhancing future information security measures. Validation tests confirmed high levels of accuracy and efficiency when applied specifically to detecting wormhole attacks targeting routing protocols in WSNs. Precision and recall rates averaged above the benchmark value of 0.95, thus validating the broad applicability of the proposed models across varied scenarios.Keywords

Wireless sensor networks (WSN) are becoming increasingly prevalent in various industrial and commercial applications. Due to vulnerabilities in both software and hardware, along with hidden or undocumented features of equipment, these networks are susceptible to unauthorized interference by attackers aiming to compromise network operations, manipulate critical system and application data of network nodes, and disrupt the information services provided by the network. Such attacks often proceed gradually over time, allowing intruders to advance through the network and overcome various protective measures. Particularly affected are wireless sensor networks with distributed structures and dynamic topologies, where route selection within routing protocols depends situationaly on the geographic locations of nodes, availability, and load of existing wireless communication channels.

Attacks on wireless sensor networks, particularly sophisticated multi-stage combined ones, can have serious repercussions. Sophisticated attacks refer to complex impacts involving multiple devices, actors, and sequences of diverse actions. They may simultaneously affect numerous network components and functionalities. For instance, a combined attack might first exploit routing violations before proceeding to substitute application user data. In worst-case scenarios, such attacks can cause catastrophic failure of targeted infrastructures, impacting not just internal data and hardware elements of WSN nodes but also the physical network infrastructure and end users. To mitigate security risks effectively, these attacks need to be promptly identified within an acceptable timeframe and with manageable computational effort. The challenge in designing attack detection methods lies predominantly in the unique characteristics inherent to wireless sensor networks.

This study focuses on modeling attack impacts in wireless sensor networks to address the challenges of information security monitoring and attack detection. It provides an assessment and comparison of existing modeling approaches, including mathematical, analytical, simulation, and experimental modeling, in their application to WSNs.

In this study, the modeling methods are examined using a hardware/software prototype of a smart city WSN providing specialized digital information services for real-time air quality monitoring and pollution detection. Experiments based on collected operational data, complemented by expert analysis and machine learning techniques, confirm the applicability of the proposed apparatus for simulating wormhole attacks in WSNs. A wormhole attack was selected to evaluate the feasibility of the proposed models and techniques. This attack is chosen because it represents a network-level threat that significantly disrupts routing processes, facilitating subsequent actions by the attacker, such as eavesdropping, intercepting sensitive data, maliciously altering transmissions, and gaining control over devices for various malicious purposes. Typically, even if an intruder controls only two nodes positioned at crucial intersections of message delivery paths, such attacks become extremely challenging to detect, especially in networks lacking adequate centralization. The difficulty in detection also stems from the inability of standard protocols to identify the tunnels created by the attack as malicious. Consequently, although relatively straightforward to model, wormhole attacks exhibit universality and apply broadly across WSN architectures. The implications of such attacks vary considerably, enabling attackers to achieve diverse objectives, such as manipulating routes, inducing delays, or causing systemic failures. Thus, attackers can exert substantial influence over network functionality. Practical instances illustrate how a wormhole attack might manifest in a complex automated system responsible for managing environmental security alerts. One illustrative example involves an unethical manufacturer employing a wormhole attack to conceal critical air pollution levels by tampering with sensor data, avoiding penalties. Alternatively, an adversary might execute routing violations in WSNs to clandestinely update firmware, embedding malicious code that transforms infected devices into potential botnet nodes.

The article additionally presents an experimental evaluation, discussion, and conclusions concerning the efficacy of the proposed solutions. This study introduces a new integrated detection method for WSN attacks. Distinct from previously discussed analogues outlined in the Related Work section, the primary contributions of this work consist of interrelated scientific findings elaborated upon in later sections.

• A combined technique for data collection, preprocessing, and analysis in WSNs to enhance attack detection capabilities. The distinguishing characteristic of this technique is its distributed approach to gathering and managing heterogeneous types of raw data, including event logs, wireless traffic records, logs from external control and information security tools, as well as sensor measurements.

• An analytical attack model detailing major network-layer threats, their attributes, and pertinent attack scenarios tailored to diverse WSN applications. Drawing upon insights from WSN expertise, an analytical model is formulated, enabling the identification of network-level attacks via graph-based event processing. The hallmark of this modeling is the utilization of a graph-based structure specific to WSNs, comprising states and transitions constructed uniquely for each attack type, thereby enabling prediction of attacks and anomalies in the context of a specific application scenario.

• A simulation model of WSNs and attacks aimed at improving attack detection within these networks. Notably, this model utilizes a comprehensive WSN representation as a foundation for parameterizing the imperative rules governing the simulation. Primarily geared toward simulating attacks characterized by variable-intensity network flows (e.g., DoS attacks, floods, scans), energy depletion assaults, and signal-quality degradations, the proposed model also aids in forecasting attacks and assessing their complexity and feasibility.

The rest of the article is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews related work in the field. Section 3 highlights the main contributions. Section 4 explains the proposed technique for data collection, preprocessing, and analysis. Section 5 introduces the analytical model for WSNs and attacks, whereas Section 6 elaborates on the simulation model. Section 7 evaluates the proposed approach compared to alternative studies. Lastly, Section 8 summarizes the principal findings and suggests prospective future research directions.

In the context of WSN field, many common attack types, such as Sinkhole [1] or Sybil attacks [2], are fundamentally different from conventional network threats like UDP (User Datagram Protocol) scanning or SYN (synchronize) flood, which are typical for more common and frequent general-purpose communication systems. As a result, for widely used detection mechanisms—including those based on machine learning and neural network approaches [3], Kasim demonstrates low efficiency in detecting WSN-specific attacks [4].

John et al. [5] introduce an attack detection system for clustered wireless sensor networks using ensemble methods, exemplified by several Denial-of-Service (DoS) attack types. The system comprises two core components: a clustering component employing the Fuzzy C-Means method and an attack detection component leveraging a machine-learning ensemble enhanced by feature-selection methods, Principal Component Analysis, and algorithms like Random Forest and LogitBoost. The paper’s distinct contribution lies in integrating clustering and ensemble approaches into a unified attack-detection mechanism.

Dini and Tiloca [6] describe the purpose and features of a simulation platform designed to evaluate the impact of attacks on wireless sensor networks. Authors categorize potential attacks and recommend corresponding defenses based on their anticipated effect on the network. The platform enables specifying attacks and quantifying their consequences for network operations, offering users valuable insights for prioritizing responses. This work stands out for its adaptability in objectively assessing and choosing optimal defensive strategies.

Reference [7] proposes an innovative hybrid model based on a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) architecture to enhance attack detection efficiency in medical wireless networks. The model encompasses data preprocessing, dimensionality reduction via the Modified Huber Independent Component Analysis-Squirrel Search Algorithm (MHICA-SSA), and attack classification. Testing on the NS2.34 simulator indicates improved network throughput.

In [8], a framework for evaluating security risks and selecting appropriate defense mechanisms during wireless sensor network design is presented. Proposed is an environment for formal verification and network modeling, enabling designers to anticipate the impact of potential attacks early in the design phase. The framework incorporates formal methods for creating an abstract application model and defining overall properties, alongside network modeling to measure attack impact using energy consumption and computational load metrics.

Reference [9] introduces a Detect-Avoid-Mitigate (DAM) framework for evaluating security threats and current protection measures for Internet of Things (IoT)-based sensors. This framework facilitates classification of sensor-related security threats and assessment of available attack-detection and mitigation tools. Its innovation resides in systematically organizing methods for risk analysis and classification, empowering experts to assess the security of actual IoT applications and devise robust preventive measures.

Reference [10] discusses the creation of a mechanism for optimizing the topology and efficiency of wireless sensor networks. An agent-based model was developed to investigate the propagation dynamics of worm-type attacks, while a stabilization technique grounded in optimal control theory was implemented to enhance network resilience and extend its operational lifespan.

Abidoye and Kabaso proposed lightweight models and algorithms for detecting and mitigating Denial-of-Service (DoS) attacks in wireless sensor networks. Experimental evaluations documented in Reference [11] yielded assessments of data delivery rates, transmission latencies, success rates of attack detection, energy expenditure, and the frequency of false positives. Reference [12] advocates for a hierarchical architecture founded on chance-discovery and usage-management technologies to elevate the security profile of WSNs. This system integrates continuous decision-making and adaptive threat-detection mechanisms to efficiently identify ongoing and emerging attacks. Empirical evidence supports the architecture’s capacity to discern diverse attack types and conserve resources, affirming its practical utility and efficacy.

Moreover, there exists a notable scarcity of high-quality, publicly accessible datasets suited for training effective attack-detection systems in contemporary WSNs. This underscores the necessity for advancing attack-modeling techniques that consider both the unique characteristics of a given WSN and its application domain, as well as the priority ranking of attack types requiring detection.

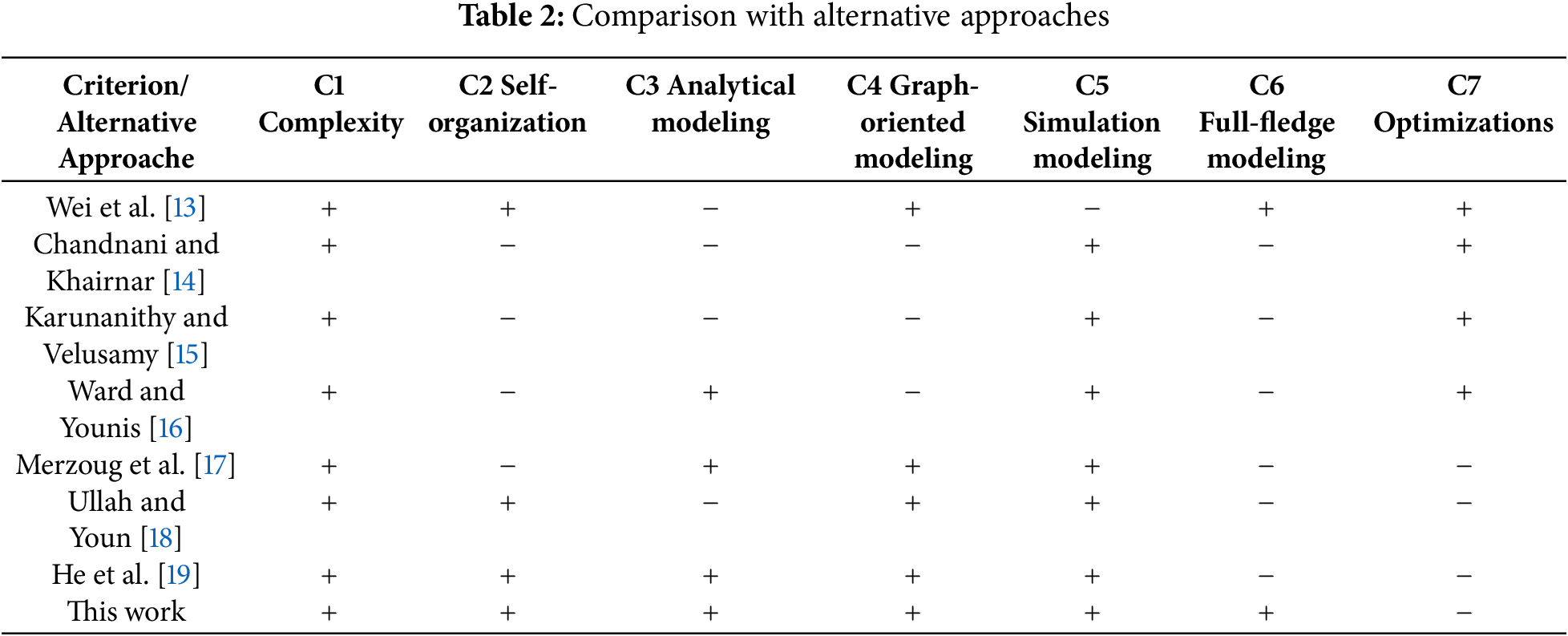

Wei et al. suggested a technique for reliable data acquisition in WSNs, emphasizing fault-tolerant data retrieval amidst potential losses or corruptions [13]. Multiple sensors contribute redundantly to ensure accurate readings. Data collection adheres to a hop-by-hop forwarding strategy, utilizing autonomous underwater vehicles as mobile relays or schedulers to minimize energy consumption among nodes. This method was evaluated within Underwater Wireless Sensor Networks addressing marine biology, oil exploration, security, cultural preservation, and similar applications.

In [14], it is argued that data processing and routing in WSNs must account for non-functional aspects such as energy consumption, channel bandwidth, and node memory usage. During data collection, aggregation, and routing, the authors aim to balance resource expenditures with security levels. A tree-like network topology is utilized for data organization, wherein leaf nodes transmit and aggregate data towards intermediary nodes, with divisions dependent on node location and trustworthiness considerations.

Karunanithy and Velusamy introduce a novel CTEEDG protocol for WSNs, promoting higher node energy efficiency and communication channel capacity [15]. Through clustering and dynamic routing adjustments, the protocol extends node longevity and reduces communication loads without sacrificing network performance. Nodes self-configure into clusters optimized for minimal intra-cluster interactions, with the Cluster Head node tasked with aggregating and relaying collected data.

Ward and Younis [16] outline a secure data collection method for WSNs that enhances anonymity by obscuring node roles, identifiers, and locations. This complicates adversarial efforts to infer network composition and structure from intercepted traces. Beyond heightened anonymity, their proposal optimizes average communication energy consumption.

Merzoug et al. advocate for spreading aggregation in WSN data collection to boost communication efficiency, including reductions in energy consumption, routing lengths, and latency [17]. This approach avoids dependence on predetermined routes, negating the need for maintaining routing tables. Scalability is further enhanced by direct one-hop connections with adjacent nodes.

Ullah and Youn employ data aggregation during collection, basing it on similarity analyses of sensor-derived data from disparate network nodes [18]. Node clustering is refined through implementation of the cosine similarity metric. This enhancement led to decreased overall energy consumption and streamlined communication processes.

He et al. address the issue of bolstering data reliability within networks characterized by dynamic topologies and the presence of potentially dishonest devices [19]. The adopted data aggregation algorithm aims to fortify security and expose deceitful neighboring nodes. Replacing conventional cryptographic methods with a consensus algorithm minimizes computational burdens on network devices, alleviating demands on node resources. Concurrently, data privacy remains adequately maintained, essential for practical implementations like intelligent conference infrastructures.

Notably, drawing from this area’s analysis, Section 7 establishes pivotal criteria integral to preparing initial data and modeling frameworks for tackling attack detection challenges in WSNs. Compared to referenced works, the proposed approach, blending data collection, preprocessing, analysis, and dual-mode modeling, excels beyond comparable alternatives.

This section thoroughly outlines the key findings achieved in this study, focusing on its purpose, distinctive traits, and other fundamental characteristics.

3.1 Technique for Data Collection, Preprocessing, and Analysis in WSN

Accurate modeling of attack impacts in WSNs necessitates the development of methods for generating appropriate input data. The proposed technique defines the processes of data collection, preprocessing, and analysis in WSNs, essential for detecting network attacks and anomalies arising during network operation.

The demand for such a technique originates from the complexity of data exchange processes in WSNs, which function in highly dynamic environments. Additionally, WSNs frequently confront significant resource limitations, directly influencing the feasibility of effective data collection. Crucial facets of data collection in WSNs encompass:

• Ensuring completeness of gathered data, guaranteeing adequate temporal granularity in sensor readings and system events.

• Maintaining data accuracy, minimizing errors and missing values in datasets.

• Enhancing data aggregation efficiency, diminishing data transmission volumes while preserving reliable anomaly detection.

Moreover, the necessity to refine data collection, preprocessing, and analysis processes stems from inadequacies in existing alternatives, failing to meet the demands imposed by the intricate modeling apparatus. Specifically, to enhance modeling quality, it becomes imperative to synthesize various approaches, capitalizing on benefits derived from full-featured physical network modeling, analytical representations of networks and attackers, as well as simulation modeling, enabling resolution of organizational and technical obstacles encountered during network scaling and attacker action replication.

An additional vital element of WSN-applied information services’ functionality lies in the legitimacy of implemented data aggregation procedures. Firstly, these procedures diminish the volume of data collected in the network—a factor typically critical under stringent resource constraints. Secondly, they augment data reliability by excluding random emissions, anomalous values, and, occasionally, data maliciously altered by potential attackers. Collectively, these factors underscore the urgency of establishing effective data collection, preprocessing, and analysis practices in WSNs—the focal point of this investigation.

Generally, data collection and accompanying technological challenges represent one of the foremost issues in contemporary wireless sensor networks. Addressing these challenges is essential for transferring data from sensors to base stations, including for the correct provision of information services to monitor data from surrounding software, hardware, and physical infrastructure [20]. Specifically, extant data collection methods in WSNs across diverse practical contexts necessitate swift reception of data during network operation. Goals include minimizing the transit duration of sensor readings and other message types to ensure completion of deliveries before any intermediate nodes required for retransmission become unavailable for any reason. This concern intensifies when concurrent multiple data collections occur across a series of nodes within a peer-to-peer network segment en route to the base station. Deliberate random delays are introduced to synchronize receipt of numerous messages and prevent collisions, thereby enhancing communication reliability [20].

Simultaneously, apart from curtailing delivery delays, efforts seek to minimize energy consumption by nodes engaged in data collection and transmission within the WSN. Effective data collection requires balancing requirements for shortening data transfer distances, limiting broadcast traffic volume, decreasing the quantity of messages dispatched to the base station, and evenly dispersing energy consumption across the majority of network nodes. Optimization of data flow is facilitated by clustering algorithms, permitting localized data aggregation ahead of forwarding to the base station.

Distinguishing itself from established approaches, the proposed technique innovatively adopts a decentralized paradigm, wherein data collection is orchestrated through predefined interaction rules between network nodes. It accommodates a hybrid strategy, harmonizing diverse data sources and supporting parallel execution of data collection and processing tasks. Novelty is evident in the synthesis of three modeling paradigms: full-featured physical prototyping of the WSN and attacks, analytical modeling, and simulation using graph-based representations. Designed for network administrators and security professionals involved in deploying and sustaining WSNs, particularly in expansive cyber-physical ecosystems like smart cities, smart factories, and intelligent transport systems, the technique prescribes sequential actions for both design/configuration phases and operational stages to foster efficient detection of attacks and anomalies.

Validation of the technique entailed testing on an experimental WSN prototype based on the ZigBee protocol [21]. Evaluations incorporated simulated wormhole attacks at the network layer, showcasing the technique’s applicability in realistic security settings.

Consequently, the technique embodies a holistic approach to WSN data processing, leveraging the intrinsic characteristics of such networks and employing a suite of complementary methods to enhance the efficiency of data collection, preprocessing, and analysis workflows.

3.2 Analytical Model of WSNs and Attacks

The article introduces an analytical attack model that identifies critical types of network-layer impacts on WSNs, characterizes them, and lists relevant attack categories specific to WSNs and their respective scenarios. Building on an analysis of WSN knowledge, an analytical WSN model has been devised, enabling attack detection through real-time event processing from network nodes and graph-based modeling techniques.

The novelty and primary strength of the proposed analytical model reside in its capacity to detect attacks on network nodes by emulating genuine system states, individually tailored for each attack type. Another distinguishing trait of this modeling approach is its modular design, permitting adaptation of the detection process to align with the needs of specific application scenarios and associated cybersecurity risks. The model accounts for essential WSN attributes, including scalability, spatially dispersed nodes, compact device sizes, restricted computing resources, and energy consumption restrictions.

A key benefit and significance of this model lie in its capability to analyze, derive insights, and generate predictions based on network data, informed by specifications, software and hardware details of a particular WSN, existing attack models, and domain-relevant ontological constructs. Furthermore, in the realm of attack detection, the proposed analytical model empowers early-stage decision-making during the WSN lifecycle, even preceding the establishment of the physical network. When designing a system, it becomes feasible to better comprehend which attack types will prove most significant for the evolving network. This foresight enables anticipation of the most troublesome attacks within the scope of the technological solutions under development.

3.3 Simulation Model of WSN and Attacks

A simulation model for representing wireless sensor networks and attacks is proposed, aimed at resolving the challenge of attack detection within such networks. The developed simulation model underwent testing using a wormhole attack scenario. This attack entails altering the configuration parameters of network nodes to impair routing processes in the WSN, diverting a considerable fraction of network traffic through a designated communication path between two compromised nodes [22]. A distinguishing feature of the proposed simulation model lies in its emphasis on detecting unauthorized actions by mimicking the functional states of the network, with each attack type modeled according to predefined system constraints.

The simulation model operates sequentially, processing events and interactions between system components solely through fixed occurrences, such as message dispatching, packet handling, and node-state alterations. The significance of this simulation model resides in its capacity to replicate complex attacks, including multistage effects, based on a fully functional hardware component paired with a simulation component. Simultaneously, it permits incorporation of supplementary software-controllable actions at the simulation level into the physical network realization, markedly easing modeling and experiments while diminishing the laboriousness of such endeavors. Furthermore, within the purview of attack detection tasks, this combined modeling approach not only enables testing of intricately modeled attacker behaviors (e.g., within the context of a wormhole attack) but also assesses the ramifications of such attacks in future iterations of multi-user self-organized networks.

4 Technique for Data Collection, Preprocessing, and Analysis

The proposed technique organizes the processes of data collection, preprocessing, and analysis, covering the stages of WSN design, configuration, and operation. It ensures timely and effective detection of relevant attack impacts on network nodes, as well as anomalies occurring during network operation. Intended for use by system engineers and administrators responsible for deploying network infrastructure, managing WSN security components, and supervising network operation, the technique applies to smart city WSNs that rely on sensor nodes to offer specialized digital information services. These services encompass real-time environmental monitoring, air quality assessment, and pollution tracking. A substantial amount of input data originates directly from sensor nodes and smart city infrastructure elements, yielding security-related events [23].

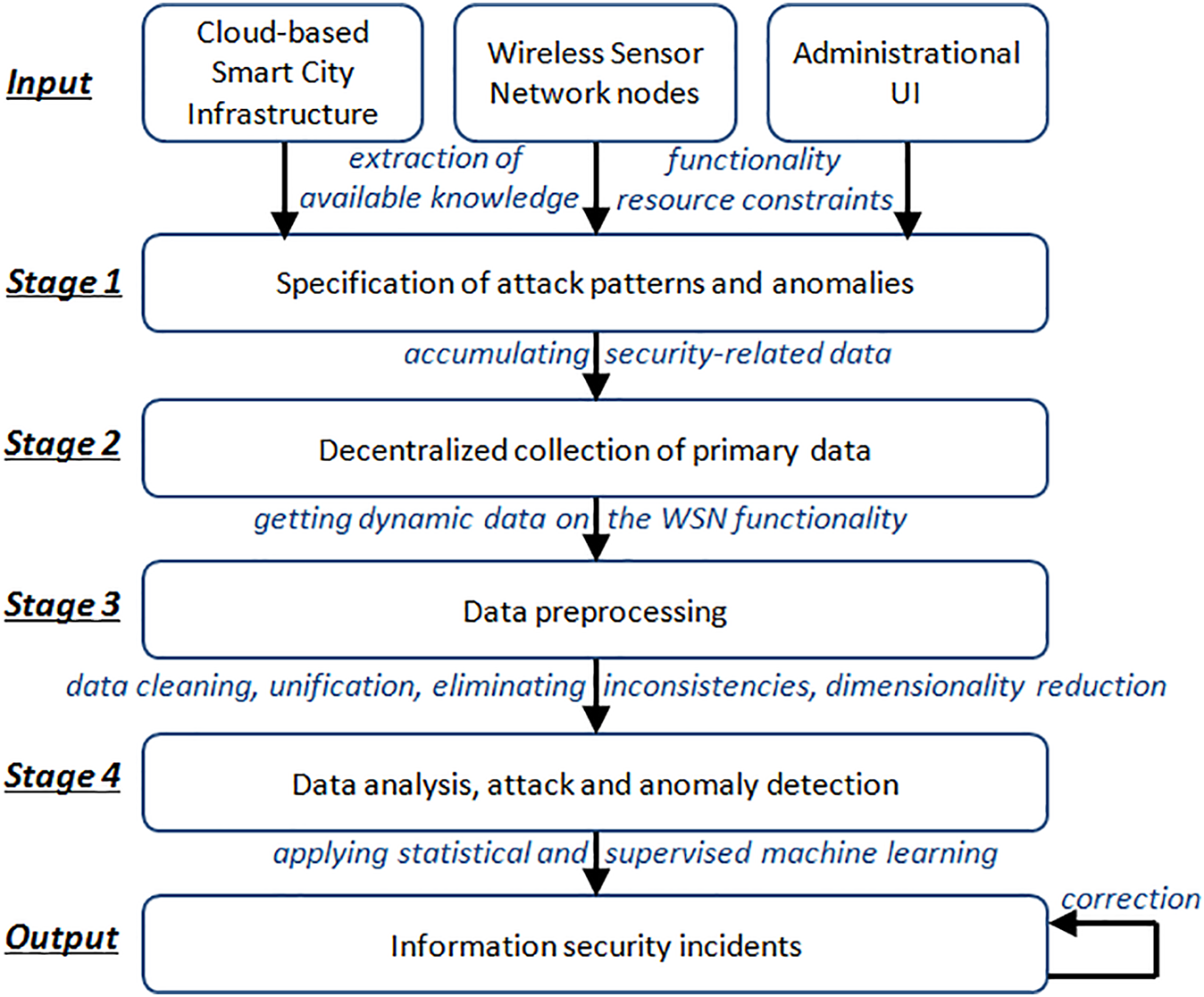

User interactions with the system, inclusive of remote data access, are enabled through internet connectivity. The technique is depicted schematically in Fig. 1 and comprises the following key stages.

Figure 1: The main stages of the technique for collecting, preprocessing and analyzing data in wireless sensor networks to solve the problems of detecting attacks and anomalies

Stage 1 (as shown in Fig. 1) involves specifying a model of relevant attacks the technique is intended to detect. Corresponding to the WSN security design phase, this stage draws inputs from a list of security requirements formulated analytically based on network hardware/software specifications, service functionality, and resource constraints. An illustrative requirement involves tracking real-time sensor data distributions and detecting outliers (abnormal sensor readings) relative to a normal distribution within three-sigma thresholds. The outcome of this stage is a set of algorithms needed for security monitoring and analysis during the operational phase of the WSN. Actions undertaken in Stage 1 incorporate system analysis and analytical modeling methodologies.

The second stage (Stage 2) emphasizes decentralized collection of primary network data. This involves acquiring information on node composition, network topology, signal quality metrics (Link Quality Indicators, LQIs) [24], and node roles (end device, router, and coordinator). System event logs are also aggregated, including records of newly established node connections, network protocol commands, and their attributes. For example, the ND (Network Discovery) AT (Attention) command in the ZigBee protocol can be used to identify neighboring nodes [25]. Logs from software executing on WSN nodes, such as those generated by the Ubuntu OS installed on a Raspberry Pi single-board computer acting as a network node, are likewise collected. Additionally, incoming and outgoing traffic at specified network nodes is logged.

It is important to note that, in general terms, Stage 2 involves sequential collection of data on network structure and composition, accumulating and updating current information in line with the self-organizing and dynamic nature of the WSN. Given the variability in spatial placement, operational modes, and wireless channel loading between nodes, the entities responsible for nodes, their attributes, and communication links undergo continual evolution. Despite this dynamism, node addresses and roles remain stable during WSN operation. The data collection process is represented as a graph-based information model initialized at the beginning of the collection period and dynamically adjusted as new primary data emerges. Inputs for Stage 2 comprise details of the current network configuration, while outputs include lists of heterogeneous logs, event information, and network traffic recorded at WSN nodes.

Raw data, encompassing system commands, sensor readings, and network events occurring at WSN nodes, together with network traffic fragments, are retained as raw logs on network nodes pending preprocessing. Different event types may be housed in separate log files. For instance, a registry logging fluctuations in communication channel quality can be established.

Typically, log segmentation follows hosts, grouping events by source nodes, recipient nodes, host groups, or event category. Each attack type may correspond to its own event log—for example, logs capturing malicious flooding attack traffic stemming from suspect network nodes. Some events, such as the registration of a new node entering the network, may duplicate across multiple log instances simultaneously. It is noteworthy that data can be amassed from each network node equipped with hardware sensors or user interfaces, as well as from nodes generating system or application data, including event-related metadata.

The third stage (Stage 3) deals with data preprocessing, refining raw data stored on network nodes to establish uniformity. Preprocessing standardizes and normalizes data formats to ensure coherence across diverse sources. This entails standardizing numeric values, unifying measurement units, and regulating decimal precision. Standardization converts data into a zero-centric numerical dataset, while normalization rescales values to fall within the interval (0, 1), maintaining relative orderings.

During Stage 3, preprocessing also decreases data dimensionality by filtering out irrelevant attributes, for instance, applying Principal Component Analysis. Dimensionality reduction can further be accomplished by eliminating redundant samples, such as repeated observations over time or duplicates sourced from multiple origins. Expert-defined data-processing rules guide such aggregation, accounting for semantic aspects of network processes, events, and collected data samples. Reducing stored-data volumes can also entail partially or entirely deleting outdated data, guided by timestamp information and data type-volume correlations.

Nevertheless, it is crucial to acknowledge that data aggregation does not necessarily decrease the size of transformed data. Time-series generation from noisy numerical sequences, separating short-term fluctuations using diverse formation schemas, can actually amplify the variability of resulting time series essential for subsequent analysis [26]. Illustrative examples include time series featuring minimum, average, maximum, and median characteristics, along with other target indicators reflecting network activity in wireless channels of WSN nodes across various operational time frames. Conversely, reducing analyzed data volume holds promise through the adoption of expert-formulated correlation rules, enabling automatic linking of individual events and consolidating meaningful information within network information security incident reports. Additionally, Stage 3 preprocessing incorporates measures to rectify potential errors and faults, such as missing sensor values, misformed or corrupted data packets, which may undergo transformations during inter-node transmission. Intentional redundancy embedded in the WSN data model assists in addressing these issues.

Input data for Stage 3 consists of raw, unprocessed primary data in the form of log samples, diverse-format events, application/system events (with or without explicit timing), and network-traffic records. These inputs are sourced from various network nodes, allowing for both local preprocessing at data-collection points and transformations at intermediate nodes, i.e., data collectors or nodes assigned to analyze data and detect attacks/anomalies. Output data from this stage is ordered and structured, optionally stored as CSV (Comma-Separated Values) files for subsequent archiving and processing.

Stage 4 signifies the data-analysis phase, encompassing the utilization of statistical methods for examining collected and preprocessed data, expert-generated rule-based methods, and artificial intelligence techniques. The latter category notably includes clustering methods, single-class classification, autoencoders, and other varieties of neural networks, whose implementations serve as software modules for anomaly detection. Supervised machine learning methods based on binary and multi-class classifiers hold promise for attack detection when sufficient labeled data is available for high-quality training and testing.

Inputs for Stage 4 consist of the complete dataset of network information gathered and processed by network devices, along with the attack-and-anomaly model established in Stage 1. Outputs encompass chronologically arranged events and information-security incidents detailing detected attacks and anomalies. Operational outputs include lists of attacks (attack(type, time, {nodes})) and anomalies (anomaly(type, time, {nodes})), specifying the attack/anomaly type, timestamp of occurrence, and a roster of WSN nodes implicated in the attack or contributing to the anomaly.

The technique’s distinguishing features, which define its novelty, include its composite nature, reflected in the amalgamation of diverse data types sourced from multiple origins—network nodes, communication-channel characteristics, aggregated statistics on node groups and application processes, etc.—coupled with the capacity for parallelizing procedural steps. Additionally, its combined character is exhibited in the capability to leverage the outcomes of attack and anomaly detection routines as supplementary initial data directly within ensuing time-cycle iterations of the technique. This iterative refinement enhances mechanisms for identifying information-security incidents by analyzing not merely current samples of incoming and processed data, but also historical primary data, their aggregated representations, and results from earlier iterations, including previously detected attacks and anomalies.

Distinctive qualities of the technique also encompass its decentralized data-collection nature, predicated on interaction rules governing network nodes and configurable collection-process parameters established during WSN-infrastructure setup.

4.2 Application of the Technique and Discussion

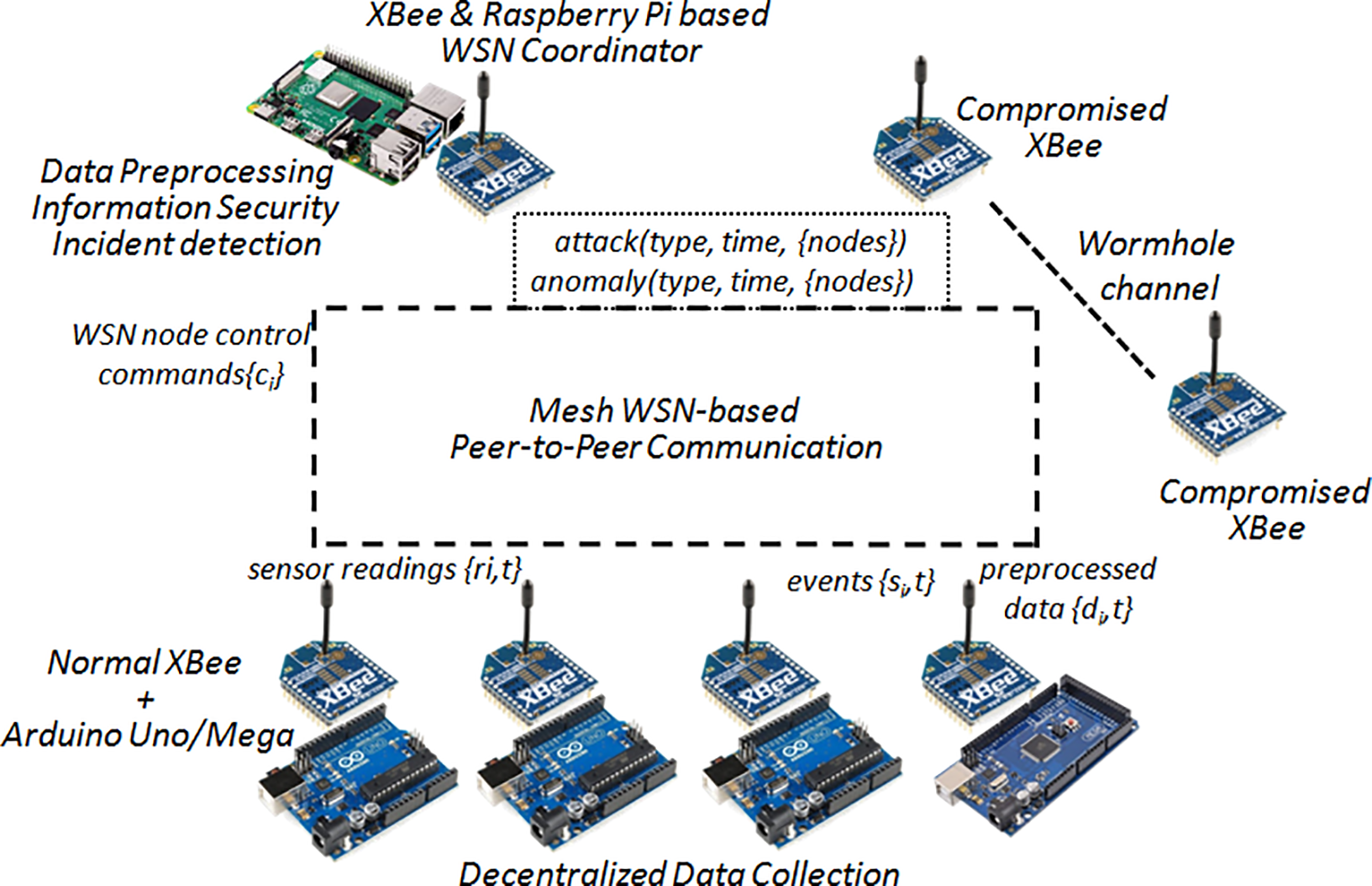

The proposed technique has been validated on a hardware/software WSN prototype constructed using XBee Series 2 wireless communication modules, Arduino Uno/Mega 2560 microcontrollers, and a Raspberry Pi 3B single-board computer running Ubuntu (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Application of data collection, preprocessing and analysis technique in wireless sensor networks to solve attack and anomaly detection problems

Network communication within the WSN is realized via the ZigBee protocol, supported by wireless XBee interfaces collaborating with microcontrollers and a single-board computer. End nodes powered by Arduino microcontrollers (depicted as blue boards in Fig. 2) are tasked with gathering primary data from WSN nodes. Collected data, acquired in a decentralized fashion, undergo preliminary preprocessing steps, including filtration within the Arduino Mega microcontroller (located bottom-right in Fig. 2). Meanwhile, the Raspberry Pi (shown as the top-left green board in Fig. 2), capable of interfacing with AI libraries like Scikit-Learn and Keras, handles the classification of preprocessed data to identify attacks and anomalies.

Within the confines of the experimental setup using this prototype, a wormhole attack is simulated. This attack exploits vulnerabilities in the routing process, enabling unauthorized selective forwarding and eavesdropping of data between network nodes. A dedicated radio channel between two attacker-compromised nodes, employed in the wormhole attack simulation, is visually indicated by the red-dashed line in Fig. 2. In addressing the challenge of detecting a wormhole attack, the following event types are gathered at each endpoint of the WSN:

– Events linked to the formation and modification of the WSN network topology.

– Events pertaining to the transmission, reception, and retransmission of service and application messages via this node.

– Environmental events encapsulating readings from hardware sensors, user interfaces, and data accessed from external module buses (where applicable).

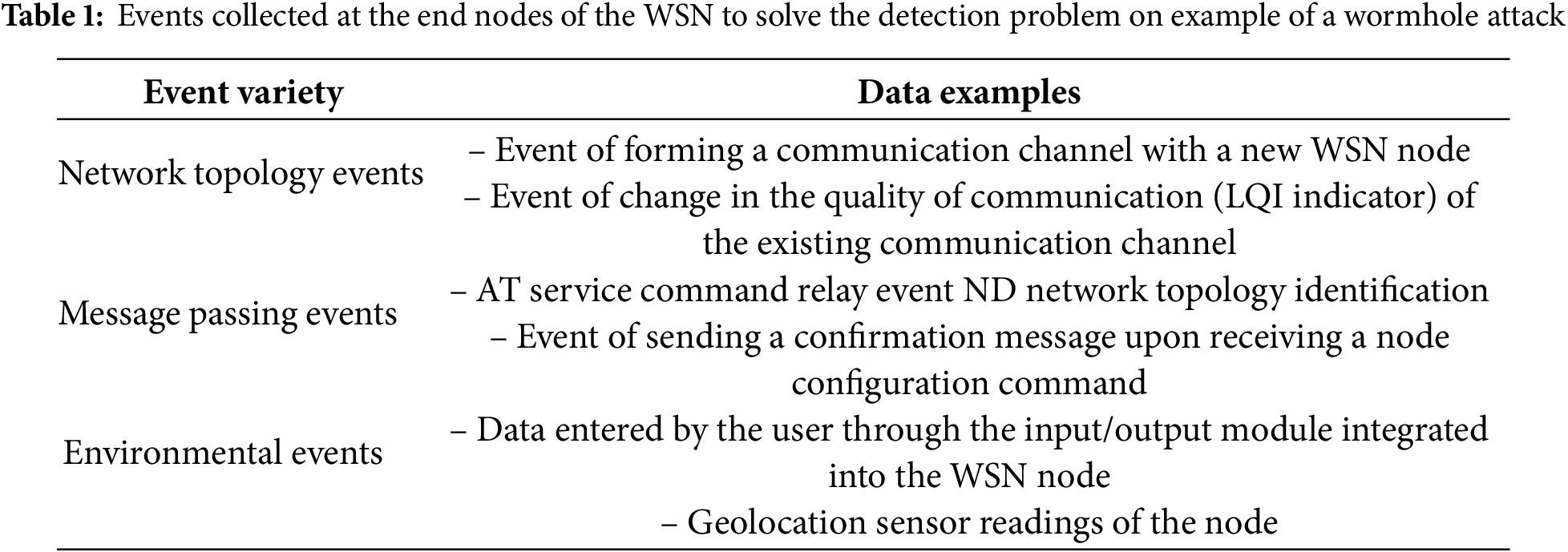

Table 1 illustrates sample events collected at WSN endpoints under the proposed technique, exemplified by the detection of a wormhole attack.

Beyond network and sensor data, system logs were accumulated on the WSN coordinator node (the Raspberry Pi), encompassing:

• Records of process initiation and termination.

• Operations involving opening, closing, and usage of network sockets.

• File-system activity.

• Modifications to OS components’ configurations.

• Interactions with peripheral devices.

• System events triggered by user actions.

Primary data, gathered in a decentralized manner across WSN nodes, undergo a preprocessing stage. Subsequently, within the Raspberry Pi controller node, feature vectors aligned with the classifier’s feature space are assembled, enabling recognition of specific attack or anomaly types. For wormhole attacks, salient features encompass statistical data on message routing pathways, nodal network-intensity values, and metrics depicting relative or absolute inter-nodal distances and communication-channel signal quality.

During the experimental validation of the technique, wormhole attacks are identified using three machine learning methods: Decision Trees (DecisionTreeClassifier [27]), Support Vector Machines (SVM, LinearSVM [28]), and the k-Nearest Neighbors method (KNeighborsClassifier [29]). Hyperparameter values are drawn from defaults and grid search-generated values. Labeling of collected and preprocessed data is conducted based on timestamps pinpointing the onset and conclusion of simulated attacks, coupled with the physical addresses of XBee wireless communication modules. Across all three ML approaches, precision and recall scores exceeded 0.95 on the test dataset, substantiating the technique’s viability and practical applicability, particularly within smart-city WSN scenarios.

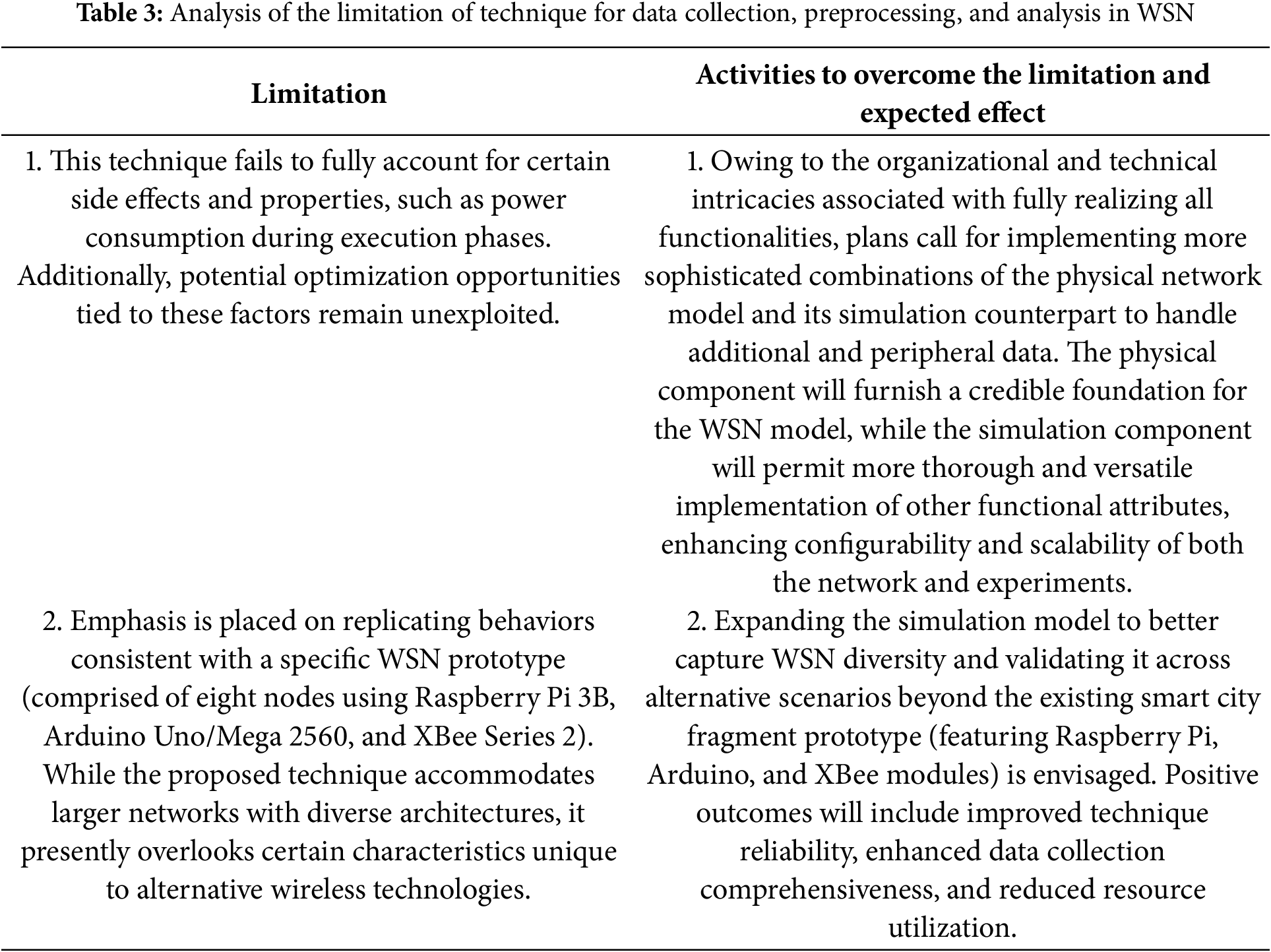

Limitations of the proposed technique include the prerequisite for performing decentralized data collection and preprocessing. Currently, the technique disregards potential technical glitches and unintended failures in WSN operation, omitting provisions for controlling and retransmitting undelivered messages. Furthermore, reliably labeling data for supervised learning poses organizational and technical challenges, particularly when dividing event logs into ‘normal’ vs. ‘mixed’ categories (logs incorporating both benign and attack-related data). Complexity escalates during concurrent simulations of multiple distinct attacks. Without proper differentiation, performance metrics for combined attacks degrade noticeably. To mitigate time-consuming manual intervention, labeling is typically automated via scripts tailored to the specific data type. Nevertheless, basic versions of labeling are confined to known attack-start and -end timelines and the addresses of impacted nodes. If two distinct, independently-launched attacks overlap temporally, overlapping log events might be mistakenly attributed to both attacks simultaneously, rendering the labels inaccurate under experimental conditions.

For instance, in air-quality-monitoring and pollution-detection systems, the simultaneous execution of two different attacks—namely, a desynchronization attack aimed at disrupting time-stamp synchronization among network sensors [30] and a DoS attack characterized by flooding with formally valid yet extraneous sensor-readout data from compromised nodes [31]—can compromise label quality. Misattribution of events from one attack to another might arise due to the increased volume of data generated by both attacks and their concurrent occurrence. Furthermore, average statistical characteristics, time-frequency properties, and packet sizes are initially scrutinized, which may obscure underlying distinctions between the attacks. Hence, the complexity of constructing high-quality labels, coupled with insufficient validation tools, can degrade data quality when simulating multiple attack types concurrently. Consequently, our current work restricts itself to modeling a single attack type.

Nonetheless, in the absence of—or when faced with suboptimal—labeling of analyzed data, it remains viable to uncover information-security breaches using anomaly-detection techniques. Methods such as clustering [32], the three-sigma rule [33], autoencoders [34], statistical-outlier recognition [35], and one-class classification [36] do not necessitate labeled data. However, anomaly detection divorces discovered events from recognized attack categories, leaving no clear explanation for why certain events were flagged as anomalous.

Advantages of the WSN architecture employed in this study include its self-organizing nature, exemplified by the mesh-network protocol. Self-organization enables dynamic routing along preferential data-transmission channels, minimizing message delays, balancing communication-channel loads, and enhancing communication reliability. Yet, network stability may be jeopardized by intrusions exploiting protocol weaknesses, such as the absence of encryption for packet-header fields. Identifying such intrusive influences during network operation, through WSN-event analysis within the proposed technique, is therefore paramount.

Adverse effects of wormhole attacks include breach of confidentiality for legitimate users’ data, potential data spoofing as part of more elaborate multi-step attacks, and collateral impacts like altered average data-delivery speeds, elevated peak data-transfer times, and aberrant data fragmentation patterns. These secondary effects themselves constitute diagnostic markers for detecting such attacks via intelligent intrusion-detection tools.

To enhance the technique’s efficiency, particularly in balancing the trade-off between the volume of collected, processed, and analyzed data from WSN nodes and the demand for hardware communication and computational resources, it is advisable to reduce both the volume of collected/processed data and the dimensionality of the feature space utilized in supervised or unsupervised machine learning for attack and anomaly detection. Specific methods of explainable machine learning can accomplish this by extracting and selecting only those attack-related information features that exert the greatest influence on determining the target variable during classification. Ranking features for each attack type under examination is achievable, with the relative importance coefficient of each feature calculable using specialized built-in functions within the Scikit-Learn library. Alternatively, a schema can be employed where a series of experiments evaluates the classifier’s performance on the feature space with successive elimination of individual features, thereby gauging the detrimental impact of absent features on the target variable.

When dealing with visualized supervised machine learning methods, such as decision trees, visualization techniques can rank features by their importance, providing expert-guided assessments. Additionally, methods like LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations), which induce intentional perturbations and insert informational noise, and SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations), grounded in game-theoretic principles for coalitional feature arrangements [37], can be deployed to elucidate feature rankings.

5 Analytical Model of WSN and Attacks

Adhering to the Open Systems Interconnection (OSI) model principles, communication within wireless sensor networks can be stratified into five primary layers: application, transport, network, data-link, and physical layers. Furthermore, WSN communication can be categorized into three cross-layer functional domains: task management, mobility management, and power management layers. These three domains span across the five OSI layers and must be accounted for in WSN security mechanisms [38].

The proposed analytical attack model is formally represented as a tuple (G, A, R, T, P), where:

– G denotes the set of attack objectives targeting WSNs, encompassing network-layer disruptions.

– A specifies the set of actions executed by an attacker to attain these objectives.

– R represents the organizational and technical resources required to launch the attack.

– T details attack characteristics and impact methodologies. Specifically, T is a formal tuple composed of sets of values corresponding to certain characteristics: the multi-step nature of the attack (sequential execution of stages); the multi-aspect nature (simultaneous impact on multiple elements); the universality (focus on a specific WSN or broader applicability); and the active/passive nature of the attack [38].

Consistent with the principles outlined in Reference [39], P defines the set of possible access types an attacker may obtain to a WSN node undergoing an attack. Within a particular attack, actual access to the targeted module might encompass one or multiple access types, including the following,

– P0 defines access via social engineering tactics. Here, the attacker seeks to deceive a legitimate user possessing direct or indirect access to a network node, compelling this user to carry out harmful actions on the node. An illustration of an attack employing this access type involves tricking a legitimate user into adjusting node settings by executing an appropriate AT command locally. For instance, an attacker might persuade a user to modify the Personal Area Network Identifier (PAN ID) to redirect a node to join another WSN or disable message-payload encryption, thereby simplifying subsequent analysis by the attacker [40]. According to the type of access denoted as P1 the attack is executed on the victim node using an external connection from the global network, specifically the Internet. This could involve an attack via a TCP/IP connection if the victim node supports it. Alternatively, the attacker might exploit any alternate protocol diverging from the standard WSN communication protocol. For instance, in a WSN operating under LoRaWAN (Long Range Wide Area Network) as its primary protocol, such an attack could be mounted through Bluetooth, Wi-Fi, or radio-channel interfaces.

– Within the WSN, P2 represents the most ‘typical’, i.e., prevalent, type of attacker access. This involves remotely influencing the victim node via standard WSN communication channels, mediated by other WSN nodes already under the attacker’s control or compromised. Typical examples include network attacks targeting routing processes in the WSN, such as wormhole and sinkhole attacks.

– With the P3 access type, the attacker achieves direct physical access to wired communication interfaces, such as USB or RS-232 ports, or exposed microcontroller contacts at the boundary of the node’s physical casing. A concrete example is an attack where a malicious node is physically connected to the victim node and exerts direct influence by issuing corresponding software commands or delivering electrical pulses. Another instance involves attaching a rogue module to the hardware interface of the victim node to falsify signals or inject noise into its wired interface.

– Access type P4 characterizes attacks on WSN nodes, where the intrusion occurs at the level of internal hardware interfaces and electronic contacts, including debugging interfaces typically inactive during routine WSN operations. An example is the unauthorized connection of a pre-modified physical sensor or XBee network module to a Raspberry Pi single-board computer, establishing a hidden communication channel for network interaction, unnoticed by the WSN operator. A distinctive feature of this access type is the necessity for more invasive physical connections within the device, potentially breaching protective seals and compromising its visual integrity.

In accordance with the classification of an intruder’s attacking capabilities [41], R specifies the possible types of organizational and technical resources necessary for carrying out actions A:

The primary types of network-layer attacks addressed in the analytical model involve active attacks, encompassing various methods aimed at disrupting routing processes within Wireless Sensor Networks. The passive attacks analyzed within the context of the model comprise eavesdropping attacks and subsequent analyses of network traffic exchanged among nodes. It should be noted that passive attacks generally serve as precursors to active attacks since they facilitate the collection of essential information needed for implementing more aggressive strategies. Besides straightforward eavesdropping, the gathering and analysis of traffic flowing across multiple nodes, both individually and collectively, exemplify passive attacks. This category also encompasses what is referred to as a “homing” attack, characterized by examining transitory traffic to infer the internal architecture of the network and assess the resources possessed by each WSN node.

Based on the outlined analytical framework, the following active attacks against network-layer WSNs are recognized [42]:

– Address spoofing attack: An assault where an adversary masquerades as a legitimate network node by utilizing a fabricated network address. Additionally, this attack allows malicious substitution of one legitimate node’s identity with another legitimate node’s credentials.

– Selective packet forwarding attack: Involves establishing criteria for choosing specific packets arriving at a particular intermediate node whose transmission will be deliberately halted by the attacker. Filtering might occur based on the sender’s address, destination address, packet size, service field values, hop count, or even statistical patterns derived from previous packet flows through the same node.

– Sinkhole attack: A scenario wherein traffic originating from a subset of WSN nodes is forcefully rerouted via a predetermined path leading to a designated “sink” node. Following this redirection, genuine routing paths are reconfigured to favor this newly established route as the quickest and preferred option for network-wide packet transmission. Consequently, the attacking node then proceeds to tamper with any packets traversing its path.

– Blackhole attack: Similar in principle to a sinkhole attack, here the objective is to attract transient traffic towards the attacking node by artificially enhancing its routing preferences relative to alternate paths within the WSN. However, instead of merely redirecting traffic, the ultimate aim is to cease all incoming data packets, thereby obstructing or completely halting communications throughout the network.

– Neglect-greed attack: A specialized variant of the blackhole attack, in which transit traffic through the attacking node is blocked to conserve the WSN communication resource for more effective transmission of its own traffic within the network. Simultaneously, the intruding node may assign higher Quality of Service (QoS) values to its own traffic [43], thus elevating its delivery priority to recipient nodes.

– Replay attack: Performed at the network layer, this attack involves intercepting legitimate nodes’ messages and subsequently rebroadcasting them once or repeatedly, aiming to impair or neutralize the receiving node’s function and degrade overall network performance.

– Sybil attack: In this attack, the offending node exerts influence over other nodes it controls by duplicating its identifier onto them, facilitating their communication with other nodes. As a consequence, routing processes in the network adjust accordingly, allowing the attacker to amplify its control over inter-node data flows within the WSN.

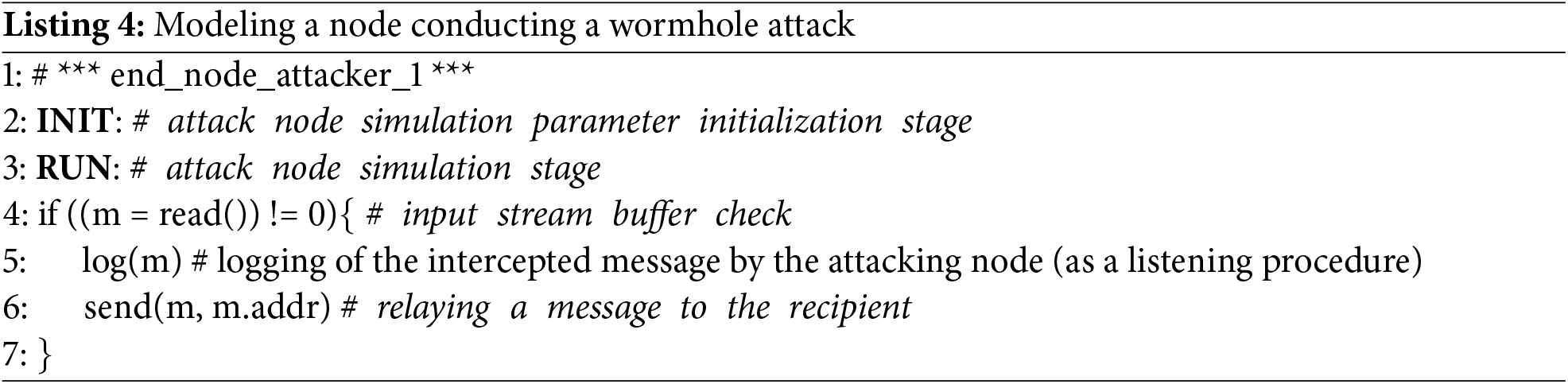

– Wormhole attack: Targeting modifications to the routing process in a WSN, this attack entails the creation of an additional communication channel between two compromised nodes, differing from standard WSN channels in interaction mode and characterized by enhanced data transfer rates. Specifically, this tunnel enables selective forwarding of packets received by one attacking node directly to another, compelling legitimate nodes to rebuild their routing paths. Generally speaking, the longer such tunnels persist, the more advantageous they appear from the perspective of conventional routing metrics, encouraging other network nodes to adopt them. Furthermore, note that this attack can adversely affect upper-layer OSI protocols, such as geolocation algorithms relying on network connectivity analysis, due to altered routing dynamics. Moreover, the strength of this attack lies in its ability to duplicate messages bit-for-bit at the channel and physical connection layers, eliminating the necessity for the attacker to analyze or alter the content of transmitted packets.

– Hello flood attack: Here, a malicious node emits numerous “hello” packets intended to verify the viability of communication links with recipient nodes. Leveraging a substantially stronger transmitter-receiver module, the attacking node can broadcast these hello packets directly to many legitimate nodes without requiring intermediaries. Meanwhile, legitimate nodes equipped with weaker communication interfaces respond to these hello packets but cannot deliver their replies back to the sender, resulting in excessive flood traffic that burdens the network.

– Acknowledgment spoofing attack: Carried out when a malicious node fraudulently acknowledges receipt of a neighbor’s packet, although said neighbor has ceased functioning for whatever reason.

– Vampire attack: Designed to exhaust the energy resources of the WSN, this attack achieves its goal by intentionally distorting the network routing process, causing elongation of data packet transmission routes, potentially forming cyclical loops. Consequently, a greater number of nodes become engaged in relaying legitimate messages, leading to accelerated depletion of their energy reserves, ultimately jeopardizing the availability of WSN nodes altogether [44].

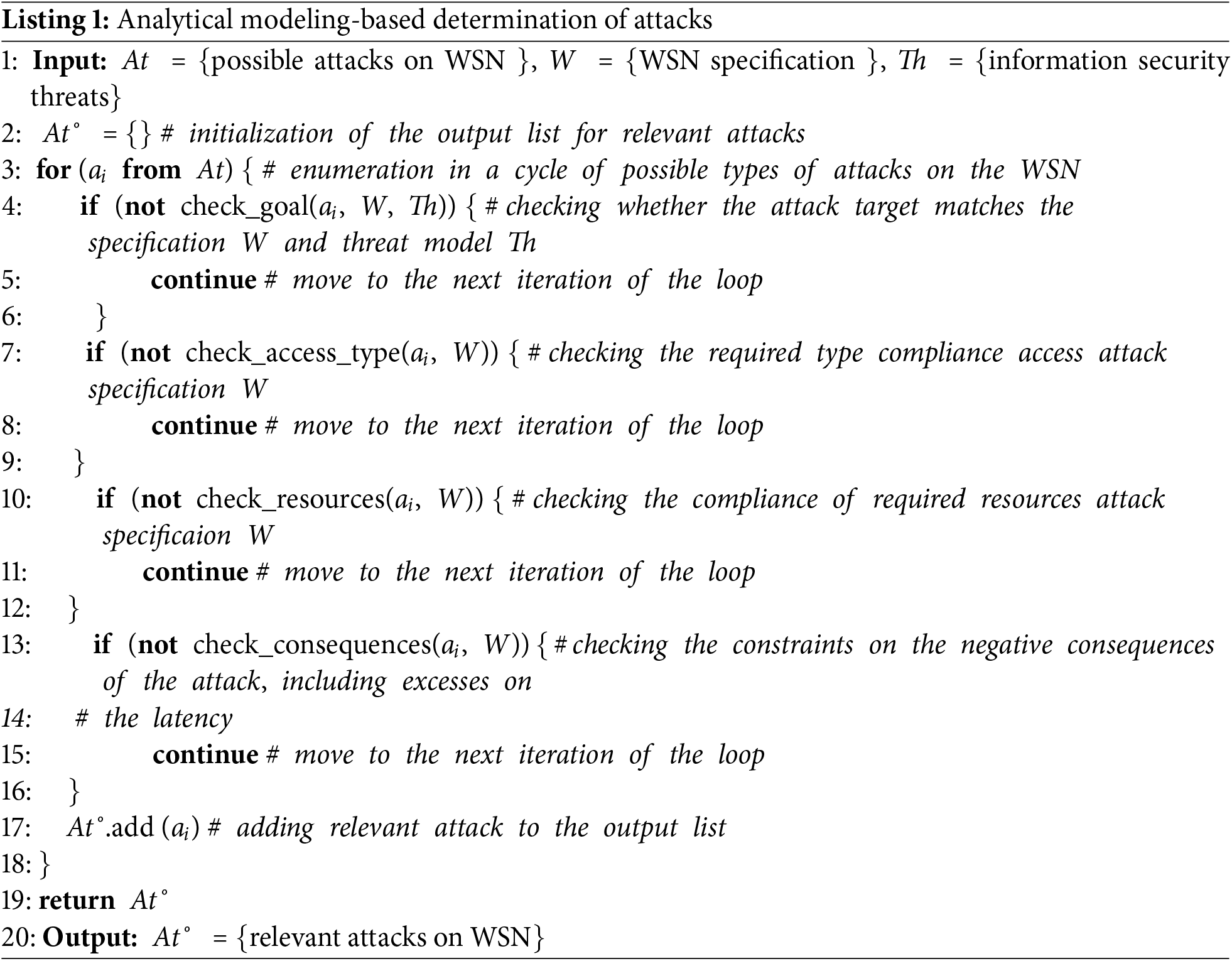

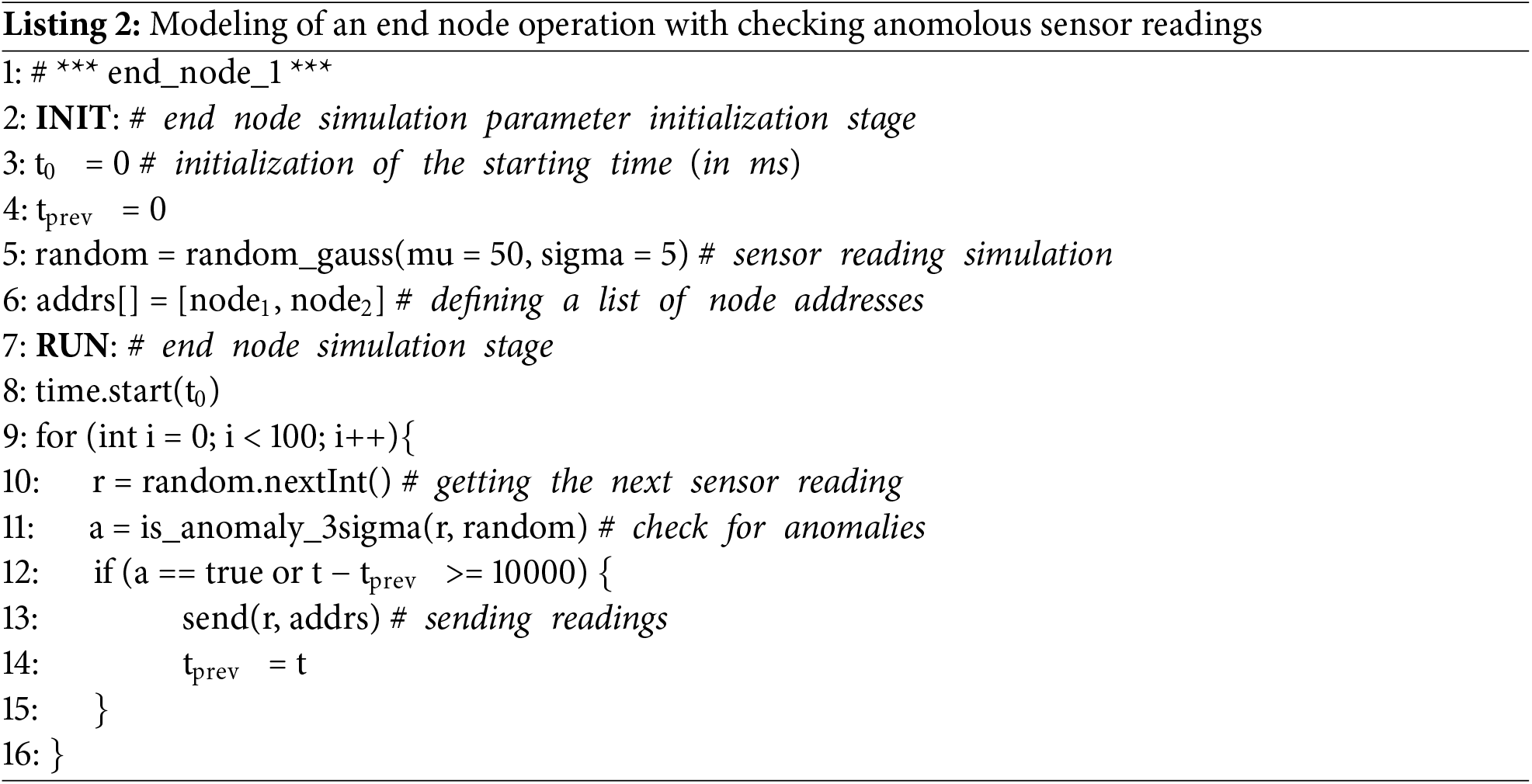

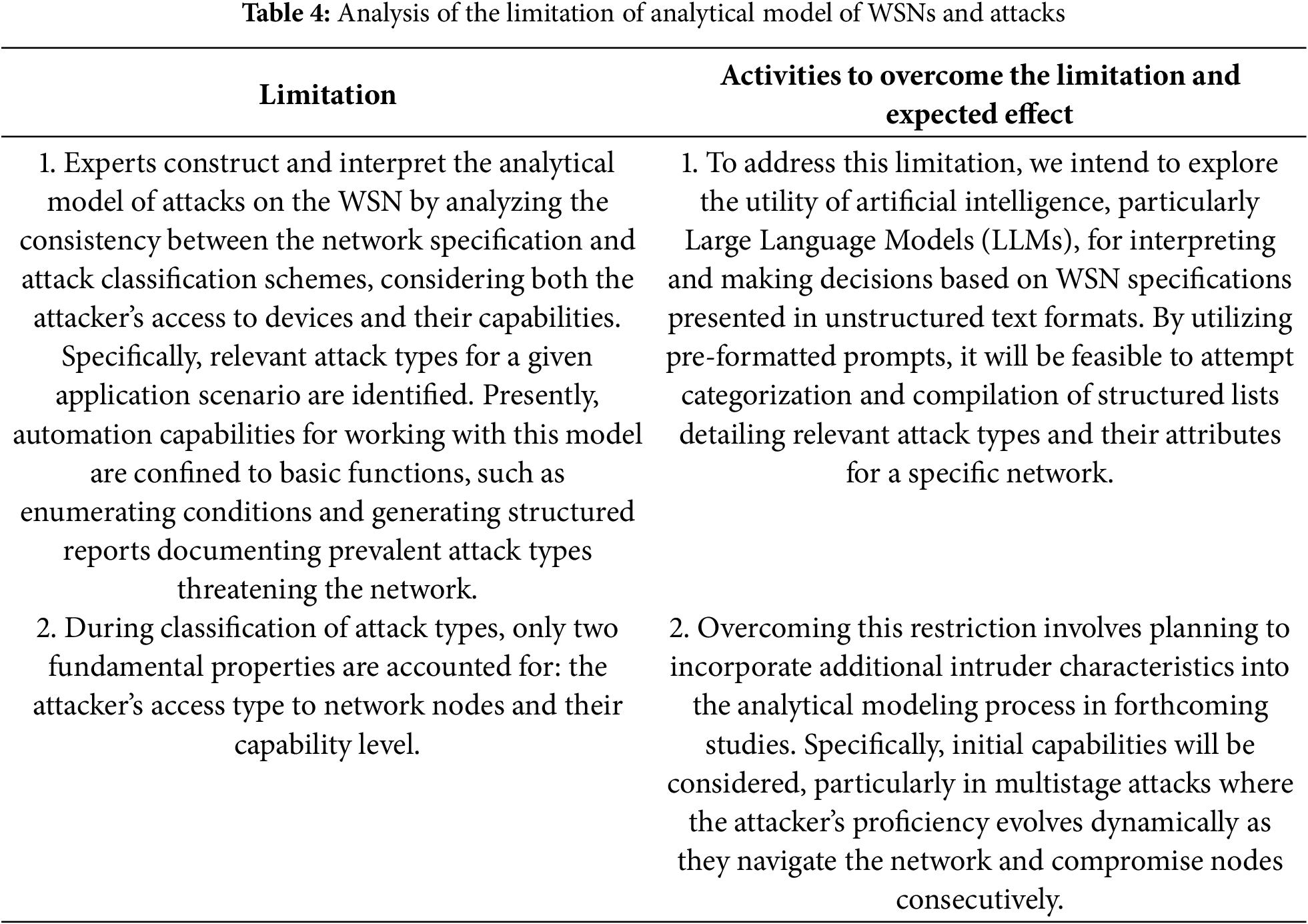

Attacks incorporated into the proposed model primarily entail disruptions of network routing processes, modification and substitution of data packets delivered to WSN nodes, and generation of malicious traffic. For this purpose, the intruder must initially gain access to WSN nodes directly under his control with either P3 or P4 access types, as well as P0, P1 or P2 access to other nodes participating in the attack process. Additionally, he needs appropriate organizational and technical resources categorized as R1, R2 or R3. The suggested analytical model is adequately comprehensive because the examined attack types are applicable to contemporary WSNs and encompass principal vulnerabilities and weak points emerging at the network level of node interactions. Analytical simulation of specific attack stages concerning functionalities, operational circumstances, and restrictions inherent to a given WSN is represented by the generalized algorithm below, detailed in pseudocode format (refer to Listing 1). In Listing 1, Line 1 outlines the input parameters of the algorithm, comprising potential attacks on the WSN, specifications of the WSN itself, and associated information security risks. These inputs are structured as textual lists. Line 2 initializes the output list for storing details regarding relevant attacks. Lines 3–18 iterate through possible attack types on the WSN, verifying the applicability of each attack to the specified network configuration and existing threats. Within the iterative process. Lines 4–6 validate whether the attack targets align with the WSN specification and the prevailing threat model. Lines 7–9 evaluate whether the attack requires matching access privileges according to the attack’s specification. Lines 10–12 assess whether the required resources conform to the attack-specific requirements. Lines 13–16 scrutinize constraints related to the adverse impacts of the attack, particularly delays exceeding acceptable thresholds. If any of the four aforementioned conditions triggers, the algorithm transitions to the next iteration of the loop. Hence, only attacks deemed relevant by none of the mentioned conditions are appended to the list At˚ (Line 17), which serves as the final output after completing the iterations (Lines 19–20).

The input to the algorithm consists of a set At, specifying potential attack types to which the analyzed WSN could be vulnerable; a network specification W, incorporating both structural and functional details of the WSN; and an information security threat model Th tailored specifically for this network. The output produced by the algorithm is a refined list At˚, containing a reduced selection of attacks capable of affecting the network, considering its operational objectives, information security threats, and operational constraints. Primary control constructs and keywords are emphasized in boldface. Textual annotations are prefixed with the ‘#’ symbol. The core component of the proposed algorithm comprises validating the compatibility of an attack with the characteristics of the WSN specification and its corresponding threat modules (invoking the check_goal function). For instance, if the attack’s goal does not qualify as critical within the threat model Th, the attack is disregarded, proceeding to the next iteration of the cycle. Subsequently, verification ensures that the access type demanded by the attack aligns with the WSN specification W (using the check_access_type function). Particularly, if the attack necessitates direct access to the targeted node, yet the specification indicates difficulty achieving such access owing to robust physical protective measures, the attack is dismissed, advancing to the subsequent iteration. Thereafter, a comparable assessment confirms alignment between the required attack resources and those presumed to be available to the attacker. Ultimately, provided the attack successfully clears all three validation tests, it is classified as pertinent and appended to the At˚ list of relevant attacks targeting the WSN. Once the cycle concludes, the compiled list of At˚ relevant attacks is returned as the outcome of the algorithm. Therefore, for a specific instantiation of a wireless sensor network aligned with a concrete practical application, it follows that employing the proposed analytical model effectively narrows down the spectrum of known attack types to a concise catalog of attacks warranting defensive measures for safeguarding the WSN.

The proposed analytical model for a wireless sensor network aims to solve issues related to identifying attacks on a WSN by adopting a graph-based methodology. It is formally represented as the tuple (S, A, P, E, T, f), where: S denotes the set of WSN states, with the element s0 characterizing the initial condition prior to launching the WSN. The set of states comprises two distinct subsets: SN, representing normal operational states, and SA, indicating states affected by attacks. A describes an analytical representation of relevant attacks on the WSN, formulated through execution of the previously discussed algorithm tailored to a specific WSN environment. P signifies the set of security metrics pertaining to the WSN. E encapsulates the ensemble of events unfolding within the system. T represents timestamps corresponding to recorded events from set E. f designates a transition function that facilitates determination of the succeeding WSN state based on the present network condition and incoming events

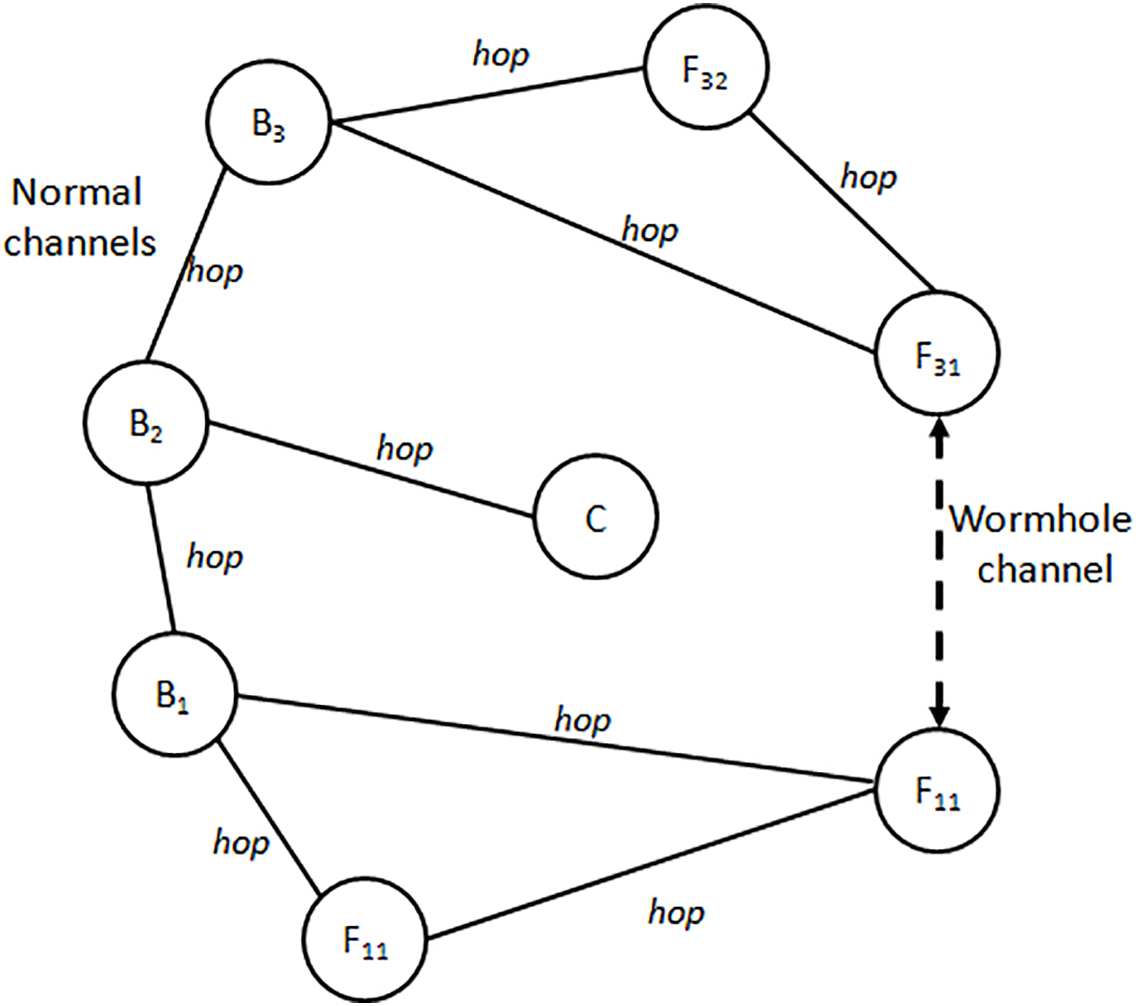

Thus, at the receiving node, as well as at each intermediate node, when transmitting a packet over the network, a check is performed on a pair of values of the form (gi, ti). Given the homogeneity of WSN nodes and connections between them, the data transmission time over the network should be approximately proportional to the actual distance between nodes as a first approximation. Note that a wormhole attack is characterized by the presence of a third-party physical channel between two compromised WSN nodes. Such channel is usually with faster data transmission, for example, over a direct wired connection or radio channel, carried out in order to disrupt network routing processes. Therefore, significant, repeated deviations over time during the transmission of subsequent data packets, primarily in the direction of a significant decrease in message delivery time, will be a sign of a wormhole attack.

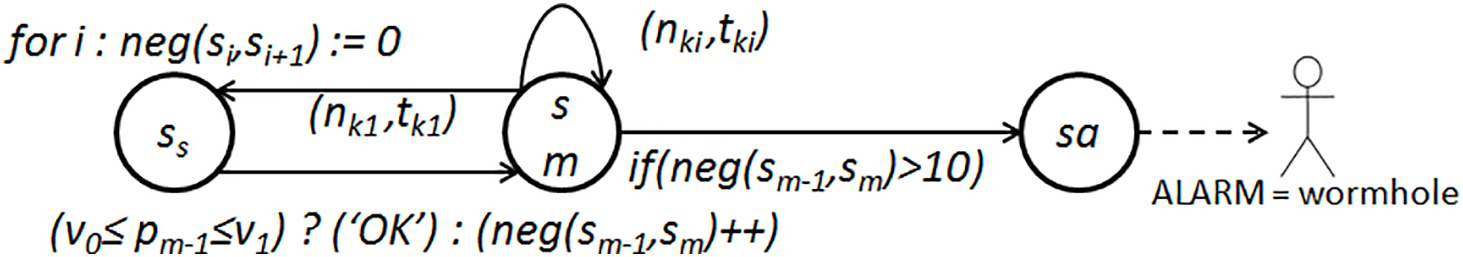

Fig. 3 illustrates a schematic representation of a wireless sensor network model dedicated to detecting wormhole attacks. In this diagram, ss represents the state of the WSN at the precise moment when message transmission initiates from any arbitrary node. Specifically, the message originates from node nk1 at time tk1. Following successful message dissemination, the network transitions into the state labeled sm. Every time control shifts to the sm state, the security metric pm−1 is computed based on the message received by node m. Subsequent relays of the message to adjacent intermediate nodes prompt a recurrence of this transition accompanied by recomputation of the security indicator. Should the pm−1 metric deviate beyond the prescribed bounds of the interval (v0, v1), the negation counter (neg) incremented by 1 for the communication channel linking nodes indexed as (m − 1) and m. Initially, the neg counters for connected neighboring nodes are initialized to zero. When the neg threshold is exceeded for a specific node pair, an alert signaling a wormhole attack is raised, pinpointing the affected communication channel, followed by immediate notification to the network administrator or any monitoring entity tasked with handling such incidents.

Figure 3: Scheme of analytical graph model of wireless sensor network for detection of wormhole attacks

It should be noted that, as depicted in Fig. 3, following each increment of the neg indicator by one unit, there occurs a reduction of its value by one after a preset duration—the so-called expiration period. This regulation prevents infinite accumulation of neg values and avoids accounting for sporadic fluctuations in message delivery times arising naturally from routine network activity. Effectively, a “time window” is instituted, within which aberrant indicator readings are temporarily logged by the detection mechanism. Only when the indicator reaches a suitably high threshold—in this illustration, equivalent to 10—is an attack detection incident reported.

In accordance with the logic of the operation of this model, as each new message is formed, it is executed in parallel in several threads. In this case, the control loop, covering the states designated in Fig. 3 by the symbols sm and ss and the transitions between them, is subject to parallelization. At the same time, the elements of the scheme common to all execution threads are, firstly, the calculation and verification of the neg indicator for exceeding the established limit, and secondly, the subsequent steps associated with the formation of a security incident. Thus, the variables responsible for storing the values of the neg indicators are shared between different threads, and operations on them require synchronization of the threads.

5.2 Application of the Model and Discussion

The developed analytical model of a wireless sensor network has been evaluated using the example of detecting wormhole attacks simulated on a WSN consisting of nodes based on XBee version 2 communication interfaces. Prior to deployment, the parameters of the analytical model, namely the values of v0, v1, the aging period, and the constraint on the neg indicator, were calibrated through testing the normal operation of the WSN. Alternatively, these settings can be established by domain experts.

It is important to highlight that, in the realized implementation addressing wormhole attacks, the proposed attack detection mechanism introduces an ancillary burden on the communication channel stemming from the requirement to transmit auxiliary data required for computation of the pi indicator. Although the magnitude of this overhead appears negligible in general cases, adjustments accounting for this factor must still be integrated when assessing hardware demands for the WSN infrastructure. According to the analytical model, extensive parallelization occurs not just for each individual message propagating across the network but also extends to diverse configurations tailored for distinct classes of attacks. This phenomenon consequently raises heightened expectations not solely on communication bandwidth but additionally on computational capacities of constituent nodes.

To adapt the developed analytical model for other types of network-level attacks, such as sinkhole and Sybil attacks, additional refinement is warranted, involving incorporation of states reflecting unique attributes of network behavior integral to the detection process.

Advantages of the proposed analytical model lie in its capability to identify network-level attacks directed toward nodes, explicitly integrating simulations of realistic system states uniquely crafted for each attack class. Additionally, the modularity of the resultant defense mechanism allows customization according to the specific application scenarios, including inherent information security risks, enabling adaptation of the detection procedure to accommodate operational constraints and limitations imposed by the underlying network topology.

However, limitations exist, notably the inability to comprehensively collect and process all data essential for reliable attack detection within the scope of simulation modeling. This shortcoming becomes especially evident in situations demanding aggregation and collective processing of substantial datasets directly on resource-constrained nodes, inclusive of historical data repositories, such as encountered in prolonged low-intensity vampire attacks.

Key distinguishing traits of the proposed WSN modeling and network-level attack paradigms incorporate considerations of scalability, spatial dispersion of nodes, compact physical dimensions, constrained computational resources, and stringent energy consumption boundaries.

6 Simulation Model of WSN and Attacks

The proposed simulation model of a wireless sensor network (WSN) aims to simulate the behavior of a WSN, its devices, and the actions of users and information security offenders under conditions closely mimicking the actual operation of physical wireless networking equipment. Through simulation modeling, it becomes feasible to streamline and minimize expenses associated with network scaling and performing multiple experiments focused on testing both primary functional and secondary non-functional attributes of the network.

To establish the rules governing the simulation, reliance on the peculiarities of the subject matter and a predefined usage scenario of the WSN is essential. To achieve this end, the domain of smart city systems was selected [12]. As a foundation, we utilize a hardware/software prototype of a WSN composed of three device types serving as its nodes:

– Central node: Serving as the main, centralized component of the WSN, augmented with cloud components for orchestrating smart city services.

– Stationary communication nodes: Base stations deployed to ensure complete coverage of urban areas, maintaining seamless connectivity among themselves through high-speed communication channels arranged in a mesh-like cellular topology.

– Mobile terminal nodes: Installed on moving infrastructure units, vehicles, residential buildings, business facilities, and others. Within smart homes, these nodes may operate independently with renewable energy sources, underscoring the significance of optimizing their energy consumption.

The central node incorporates a Raspberry Pi Model 3B single-board computer, empowered by a quad-core ARM processor, enabling it to process data streams from other network nodes efficiently. Connectivity options include Ethernet and Wi-Fi ports. Equipped with an XBee wireless communication module, the node maintains connections with other WSN nodes. Powered centrally, it connects via a stationary network link to a cloud infrastructure capable of delivering information services for WSN management.

An intermediate node, typified by an Arduino Mega 2560 microcontroller, receives power from a stationary supply and fulfills the role of base stations. Its wireless communication interface employs an XBee module featuring a high-powered transceiver, ensuring comprehensive coverage of the base station network. Due to technical constraints imposed by the utilized ZigBee protocol version, the quantity of such nodes within the network remains bounded. More precisely, within our hardware/software test setup using Digi XBee Version 2 nodes, to maintain error-free and lag-free communication, the maximum recommended number of nodes is typically capped at several dozen units.

The end mobile node of the WSN incorporates an Arduino Uno microcontroller, powered by an independent renewable energy source. Alternatively, an Arduino Nano microcontroller optimized for minimal power consumption can be utilized, offering restricted communication and computational capabilities alongside a limited array of hardware connectors. Assuming a finite number of endpoint nodes within the WSN, each retains mobility, collects sensory data embedded within it, manages actuator functions, and handles reception and transmission of service-oriented and application-related data via the XBee interface. Further, the endpoint node supports switching to a lower-energy mode when idle, awaiting reactivation upon specific trigger events, such as receiving a message or elapsing a predetermined timeout.

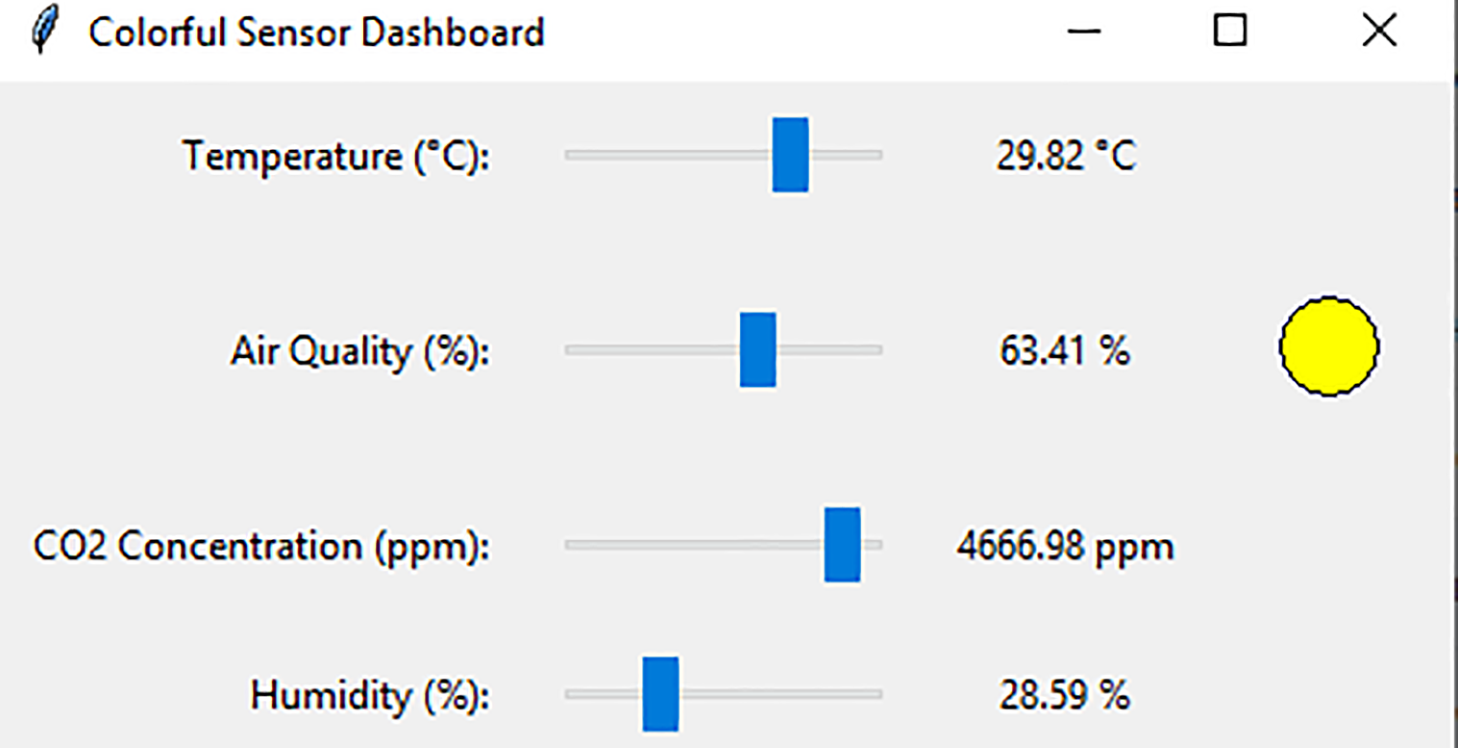

The fully constructed network model serves as a cornerstone for developing a simulation model, enabling replication of network evolution under varied initial conditions with scalability flexibility. Illustrated in Fig. 4, nodes R0, R1, and R2 integrate wireless XBee modules interfaced with self-sufficient power supplies and microchips housed in plastic enclosures. Two additional nodes positioned on the right are tasked with attack simulation and provide a display for controlling substitutions of sensor measurements during network transmission within the experiment. Alterations in sensor readings are visualized on a dashboard hosted by the coordinator node and mirrored on a laptop directly linked to it (as shown in Fig. 5). Consequently, Fig. 5 exhibits a dashboard displaying temperature, pollution levels (an aggregate measure of air quality), carbon dioxide concentrations, and humidity values collected by sensors.

Figure 4: The simulated WSN node of with the router role

Figure 5: Dashboard with modifiable sensor readings

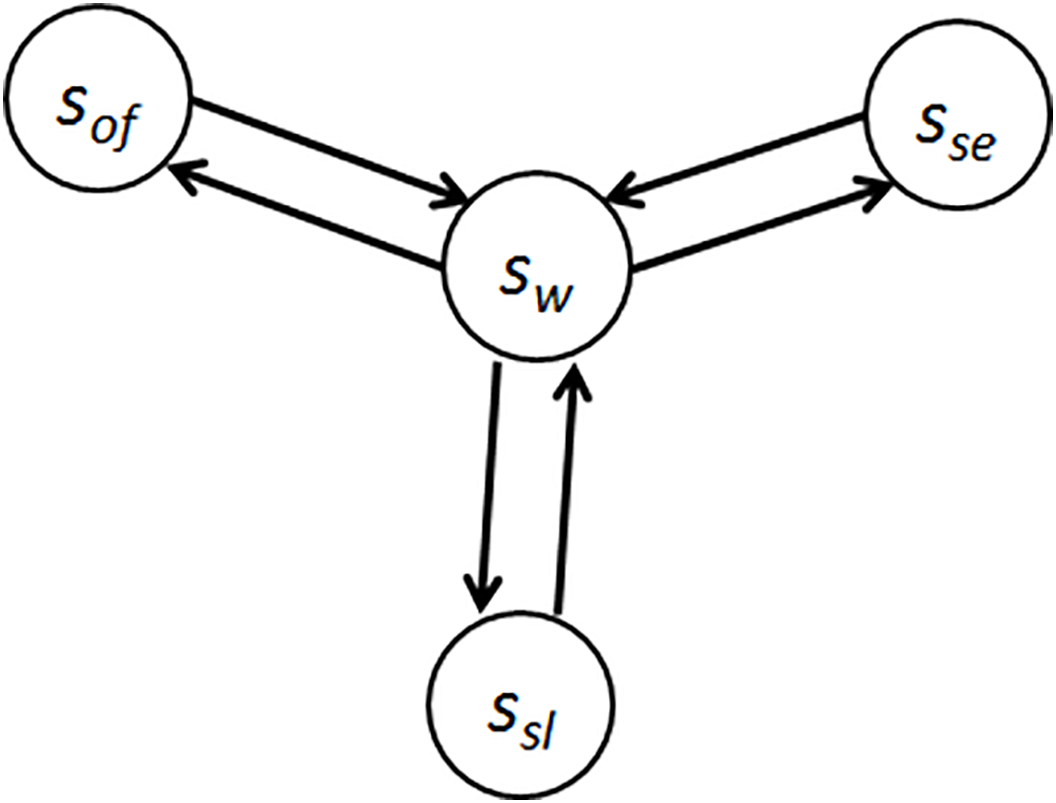

The proposed simulation model takes the form of three distinct graphs, each tailored to represent a specific type of WSN node. Vertices within each graph correspond to functional states of the node, while arcs depict allowed transitions between these states, dictating executable actions on the node. Individual states encode the current characteristics of the node’s hardware and software, ongoing processes, and managed data storage. Parameters of the simulation model are fine-tuned to reflect the operational nuances discerned within the broader WSN framework.

Illustrated in Fig. 6 is a graph illustrating a mobile endpoint node, encompassing four primary states and transitions among them. State definitions include. sof denotes the powered-down state of the node. sw represents the active operational state of the node. ssl indicates the energy-conservation (“sleep”) state, entered by the node for a pre-specified duration or until the arrival of a network message. se designates the maintenance/service state, reserved for firmware updates and parameter adjustments by authorized personnel.

Figure 6: State graph for the end node of the WSN

As illustrated in Fig. 6, transitions between states are initiated by events associated with a specific node, either adhering to predefined sequences or governed by rules dictating their occurrences during network simulation. Typical examples of such events include receiving commands instructing the node to enter sleep mode or reaching a scheduled timestamp triggering automatic transition to sleep mode, as programmed internally. Other instances encompass receipt of messages from adjacent nodes, prompting either a shift to another state or simply relaying the message onwards based on the designated recipient address, while remaining in the original active state.

Decisions by the node to respond to events, including state transitions, hinge not exclusively on static configuration parameters shaping its functionality but also on dynamic attributes evolving during runtime. These mutable properties, updated continuously throughout the process, encompass vital metrics such as residual battery life, available Random Access Memory (RAM) capacity, IDs of reachable neighbors, Link Quality Indicators (LQIs) quantifying wireless signal integrity [24]. While residing in the active state (sw), the node undertakes several primary tasks that do not induce state alterations, such as retrieving sensor data, activating or adjusting actuator behavior, receiving and distributing network messages, anticipating incoming signals, interacting with the data storage subsystem, and executing computations.

It should be noted that for each node of the WSN, within the framework of the simulation model, its instance of this type of graph is created, which is placed in the operational memory. Launching the simulation model assumes preliminary installation of the vector of initial values of the configuration parameters for all nodes of the network. The process of working out the simulation model is discrete-event and determines successive changes in time of variables—dynamic characteristics of each of the nodes. One of the options for defining the simulation modeling scenario is an explicit assignment for each node of a sequence of node events, where each one is provided with a certain time stamp. In this case, the simulation model is specified by chains of pairs (e({atti}), t), where e denotes an event of a certain type with specified values of its inherent attributes atti, t is a time moment determined by a non-negative integer value, and the pairs are ordered as the time moment t increases.

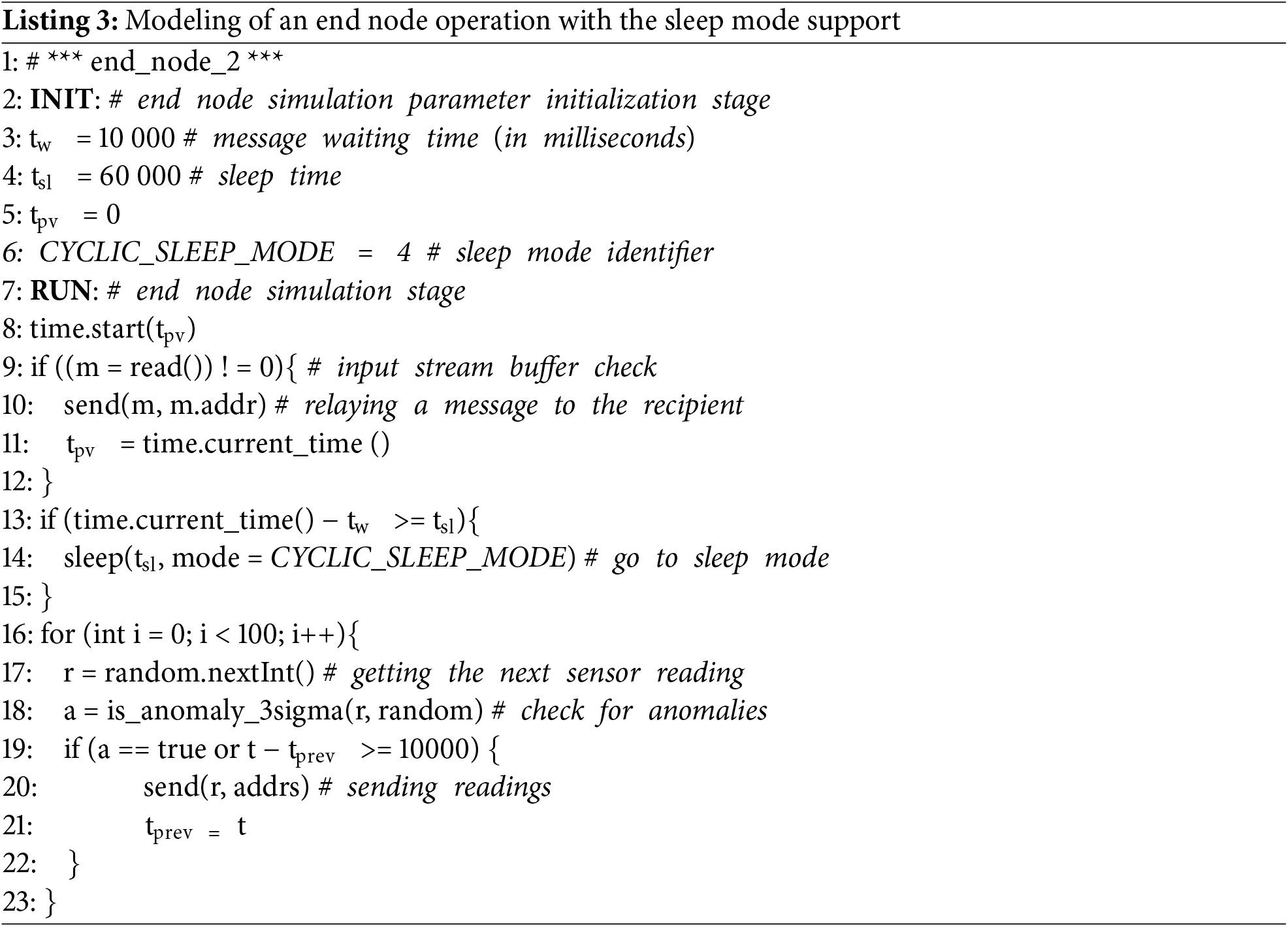

An alternative option for setting the node operation scenario is to determine the initial state of the node, from which the process of simulating its operation begins, as well as to generate node events based on rules that use probabilistically specified events for this node. For an end node, the initial state can be sof, from which a transition to the sw state is made. An example of such rules for an end node would be regular reading of the temperature sensor readings located on this node with a specified time interval, as well as reading the fact of the user pressing the node’s tact button. The temperature readings are modeled using an additional scenario describing the process of changing the temperature of the physical environment over time, while user data for the button can be modeled using a pseudo-random number generator and the button’s actuation with a predetermined probability of n% at an arbitrary point in time within a specified time interval of duration Δt.